Abstract

The increasing incidences of fungal infections among Covid-19 infected patients is a global public concern and urgently demands novel antifungals. Biopolymers like chitosan hold unique structural properties and thus can be utilized in the synthesis of biologically important scaffolds. To address the current scenario, the author's synthesized novel chitosan-azetidine derivative by adopting one-pot multicomponent reaction approach. The influence of chemical modification on the structural characteristics was investigated by means of spectroscopic techniques viz. FT-IR and 1HNMR and elemental analysis. Additionally, the authors investigated the antifungal potential of chitosan-azetidine derivative against Aspergillus fumigatus 3007 and the results indicated higher antifungal effect with an antifungal inhibitory index of 26.19%. The SEM and confocal microscopy images also reflected a significant inhibitory effect on the morphology of fungal mycelia, thus reflecting the potential of synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivativeas a potential antifungal agent.

Keywords: Chitosan, Aspergillus fumigatus 3007, Antifungal, Azetidines

Introduction

The development in the field of antifungals had apparently been ignored and has recently gained much public attention due to the high incidences of fungal infection among Covid-19 infected patients [1,2]. This Co-infection has resulted due to various factors such as excessive use of immunosuppressants, broad-spectrum antibiotics and radiotherapy, etc. which had led to impaired functioning of human body [3]. Recently, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA reported that the fungal infection is a “serious global health threat” to the society [4]. Worldwide more than 1 billion people are infected from fungal infection out of which 1.5- 2 million people die from the infection [5]. Therefore the current critical situation urgently demands focus and work on different aspects of antifungal therapy to cope up with the growing scenario.

Polysaccharides are natural polymers present abundantly on the earth and showed unique structures, properties, and applications in the field of biomedical sciences [6]. After cellulose, Chitin is the second-largest polysaccharide that presents abundantly in nature [7] and showed structural similarities with the cellulose and thus considered as its analogue. But insoluble in common solvents, chitin can't be extracted easily and hence perceived limited attention in biomedical field [8]. However, with the advancement in the field of polysaccharides the deacetylated product of chitin (chitosan) was come out as protonated aqueous medium soluble polysaccharide and thus minimized the drawback of insolubility and enhances the utility of chitin as natural biomass. It is now being used enormously in different fields [9]. The primary amino (-NH2) group and hydroxyl (-OH) group on the chitosan structure are important chemical sites to modify into other potential derivatives and thus making it a chemically versatile biopolymer [10].

The resistance to the existing drugs and the emergence of new resistant strains of fungi render the traditional antimicrobials less effective [11]. COVID-19 brings thousands of people into hospitals every day but the viral infection is not always fatal. However, the comorbidities which develop in the due course of treatment in the form of fungal infections render the situation lethal. Emerging evidence suggests that infection with SARS-CoV-2 and possibly the drugs used to treat it makes COVID-19 patients especially vulnerable to Aspergillus. Among the secondary infections that may occur in COVID-19 patients, coronavirus-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) is emerging as a potential cause of morbidity and mortality, the dysregulated immune response in COVID-19 increase susceptibility to Aspergillus infection [12,13]. To address the current problem of Covid-19 fungal co-infection and resistance with the existing drugs, new antifungal with high selectivity and a novel mechanism are urgently in need. In view of the above, the antifungal polymers have emerged as an ideal candidate of choice to inhibit the spread of antimicrobials resistance due to their novel specific mechanism and long-term efficacy [14]. Chitosan, a natural biopolymer having inherent antimicrobial activity, and low toxicity, is a safer alternative to synthetic chemicals [15] and has been used in the current work as a polymer to synthesize novel biopolymer antifungal. The functionalization of the –NH2 group on chitosan by interesting chemistry of multicomponent reactions (MCRs) through ABB approach methodology (ABB are the type of reactions having one molecule of component A and two molecules of component B, incorporated to achieve maximum diversity in the final product) was carried out in this work to synthesize novel chitosan-azetidine derivative. It was expected that integration of the azetidine ring in the native chitosan structure would probably exhibit pronounced antifungal potential. From the literature, it was reported that the presence of N heterocyclics in a compound demonstrated enhanced antifungal potential [16].

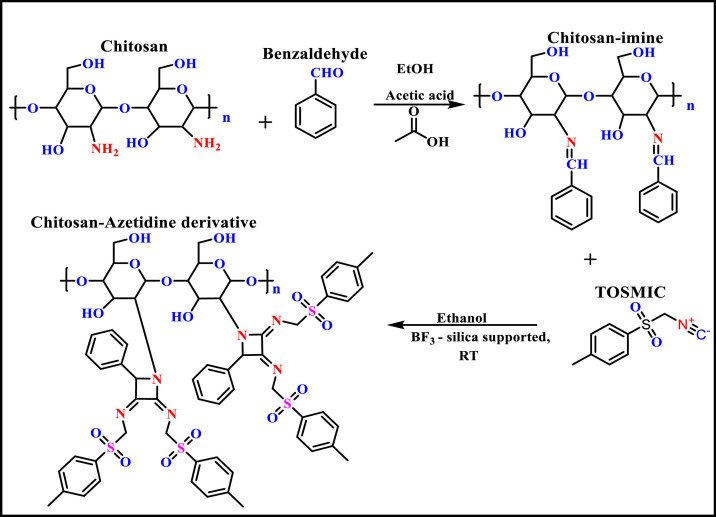

Azetidines constitute an imperative class of azaheterocyclics and exhibited a broad range of biological activities [17]. Encouraged by the unique property of azetidines as an antifungal core, reported by the literature [18] and in continuation of our research in the field of designing novel antifungals through Multicomponent reaction methodology [19,20], the authors aim to report the design and synthesis of a chitosan-azetidine derivative bearing bis- tosylmethyl group.The synthetic pathway was shown in Fig. 1 . The effect of chemical modification on structural characteristics was studied and investigated by spectroscopic techniques (FTIR and 1HNMR) and elemental analysis. Further, the authors investigated the effect of chitosan-azetidine derivative on fungal growth of Aspergillus fumigatus 3007 and compared the data with native chitosan. The antifungal potential of the synthesized compound was evaluated and the SEM & confocal images were analyzed to establish the morphological alterations in fungal mycelia.

Fig. 1.

Synthetic route of chitosan-azetidine derivative.

Experimental

Materials

Low average molecular weight chitosan from shrimp shells with a degree of deacetylation 80–85% and the viscosity of 20–300cP was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Benzaldehyde, TOSMIC (toluenesulfonylmethyl isocyanide), Silica supported-BF3; all the chemicals used in the study were purchased from commercial Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. All the media components were procured from hi-Media Laboratory Pvt. Ltd. (Mumbai, India) and Propidium Iodide was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, USA.

Methods

Synthesis of chitosan-azetidine derivative

The reaction was performed in one pot using multicomponent reaction methodology. Equimolar concentration of Chitosan (1eq) and benzaldehyde (1eq) was taken in EtOH and placed in 50 ml RBF. To this solution BF3- silica supported [100 mg/mol] was added while on stirring. To this solution TOSMIC (3eq), previously dissolved in EtOH was gradually added. The solution was then stirred for 10 h until the reaction was complete. Completion of the reaction was monitored using TLC. After the completion of the reaction 10 ml of CH2Cl2was added to the reaction mixture and the catalyst was recovered by filtration. The organic layers were dried over MgSO4. Residue was purified by column chromatography using mixtures of Hexane-EtOAc (v/v).

Characterization

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectras were recorded on a Shimadzu IR Affinity 1S spectrophotometer in the transmittance mode and in the range from 4000 to 400cm−1. About 1:100 ratio of sample with KBr (potassium bromide) was fully grinded and mixed. The mixed samples were pressed into pellets with a compressor and prepared pellets were used. All spectra were scanned against a blank KBr pellet background using transmittance mode with the accumulation of 45 scans.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

Proton Nuclear magnetic resonance (1HNMR) spectra were recorded on a Jeol-400 NMR Spectrometer at room temperature (RT) using D2O as solvent at a resonance frequency of 101 MHz.

Elemental analysis

Sample properties were also determined by elemental analysis CHNS by using Eurovector Elemental Analyzer. The results can be used to determine the degree of substitution (DS) in a sample by using Eq. (1) as reported in literature [21].

| (1) |

Where: n1, n2 are the no. of carbon of chitosan and azetidine substituted ring respectively. MC and MN are the molar mass of carbon and nitrogen, Wc/N is the mass ratio between carbon and nitrogen in the derivatives.

Antifungal activity

Microorganism and culture conditions

Aspergillus fumigatus 3007 was procured from Microbial type culture collection (MTCC), Chandigarh, India. The cultures were grown and maintained on malt extract agar (MEA) composed of (g/l): malt extract, 20.0; and agar, 20.0 at 30 °C with pH of 6.0. The fungal cultures were maintained by periodic sub-culturing on MEA at 30 °C and stored at 4 °C.

Antifungal inhibitory index

The synthesized chitosan derivative was evaluated for its antifungal activity against A.fumigatus 3007 by the plate growth rate method [19]. Chitosan and chitosan derivative were dissolved in 1% DMSO at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Each solution was then added to 20 ml of sterile malt extract agar (MEA) to give final concentrations of 0.1 mg/ml. The solutions were poured into sterile petri dishes (9 cm). Control plates were prepared without the compounds. A mycelia disk (diameter: 8 mm) was cut from the advancing margins of growing fungal cultures and seeded into the center of each plate and incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. The radial colony growth was measured daily until the fastest growing colony had reached the edge of the plate (the experiment was performed in triplicates).

The antifungal index was calculated using the following equation:

Where, ‘Db’ is colony diameter in control and ‘Da’ is colony diameter in the test plates.

Structural analysis of fungal membrane

Experimental fungal mycelia from control, chitosan and chitosan derivative plates were collected and Scanning Electron Microscopy (Carl Zeiss, EVO/18) imaging was carried out as reported earlier [22].

Additionally, mycelia from control and treated samples were collected after 96 h of incubation period and slides were prepared as reported [19]. Glass slides were observed in bright field and fluorescence modes with excitation and emission wavelengths of 535 and 617 nm respectively, using Leica TCS SP5 confocal scanning microscope.

Results and discussion

Chemical synthesis and characterization

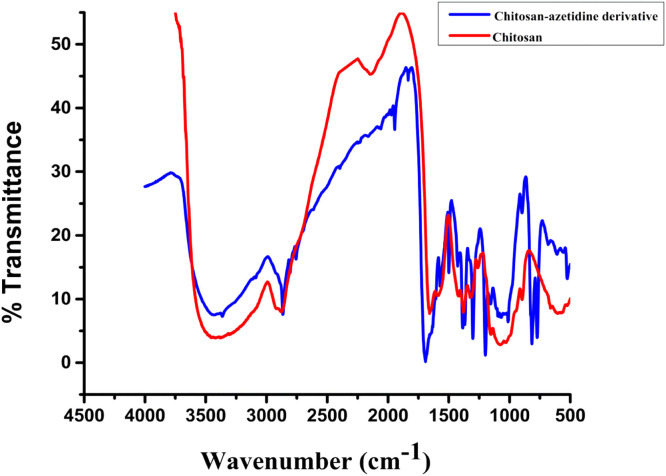

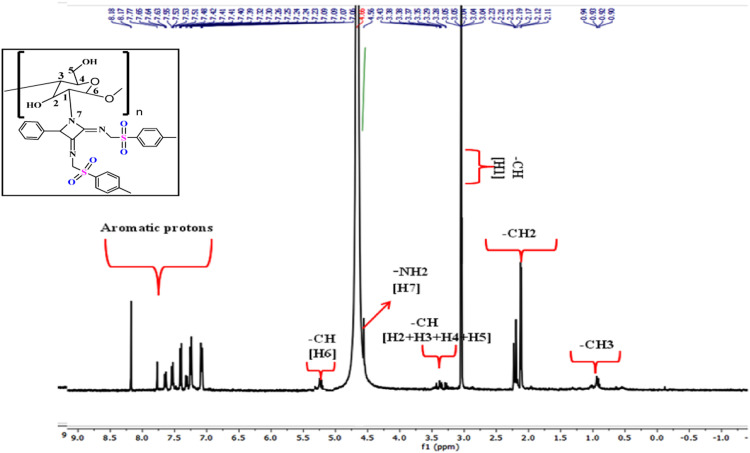

Herein, the chitosan was treated with benzaldehyde to form chitosan-imine intermediate which further reacts with TOSMIC in the presence of silica supported BF3 to form chitosan-azetidine derivative and the detailed synthetic strategy was shown in Fig. 1. The structure of the synthesized derivative was confirmed by FTIR (Fig. 2 ) and 1HNMR (Fig. 3 ). The degree of substitution and % yield was analyzed and results were reported in Table 1 .

Fig. 2.

Comparative FTIR spectra of Chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative.

Fig. 3.

1HNMR spectra of chitosan-azetidine derivative.

Table 1.

Yield and degree of substitution of chitosan-azetidine derivative.

| Compound | Yield (%) | Elemental Analysis (%) |

Degree of substitution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | N | H | C/N | |||

| Chitosan | 43.42 | 7.98 | 6.98 | 5.44 | ||

| Chitosan-azetidine derivative | 71 | 55.60 | 10.60 | 5.20 | 10.30 | 0.31 |

Spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Comparative FTIR spectra of native chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative were shown in Fig. 2. The analysis results indicated the successful modification of the chitosan specifically on the amine group. The deformation of the signal at 3542 cm−1 proved the substitution at –NH2 group. Whereas, the presence of signal at 2865 cm−1 confirmed the presence of –OH groups in chitosan-azetidine derivative [23]. Formation of the derivative was further confirmed by the absorption peaks at 1949 and 1832 cm−1 in FTIR spectrum which are attributed to the N = C-S system –CH bending of aromatic region respectively. A sharp peak at 1693 cm−1 confirmed the new C = N bond formation in derivative. The peak at 1421 cm−1 showed the –OH bending vibrations and the peak at 1367 cm−1 confirmed the S=O stretching vibrations in chitosan-azetidine derivative. The peak at 1297 cm−1 sharpens in chitosan-azetidine derivative as compared to the native chitosan confirmed the presence of more C—N bonds in the derivative, due to the formation of four member ring system of azetidine. Sharp bands at 823 and 769 cm−1 showed the –CH and -C = C bending vibrations respectively in the chitosan-azetidine derivative.

1H proton magnetic resonance (1HNMR)

Chitosan and functionalized chitosan derivative were characterized by 1HNMR. 1HNMR spectra of the functionalized chitosan were taken in D2O and are shown in Fig. 3. The spectra of the pure chitosan are similar as that of the reported literature [24]. In the NMR spectrum of chitosan-azetidine derivative, some signals of the pure chitosan were still observed. The signals from 8.10 to 7.06 correspond to the signal of aromatic protons of the derivative so formed. Signal at 5.2 was related to the proton of hydroxyl group. There is a decrease in the signal of NH2 at 4.5 in the chitosan-azetidine derivative spectra as compare to the pure chitosan [25] spectra, which indicated the substitution at NH2 protons. There are still some small signals at 4.5 are seen in the derivative spectra which may be due to unreacted amine groups. Signals from 3.43 to 3.28 are due to - CH protons of the glucosamide moiety [H2+H3+H4+H5]. The intensified peaks at 3.05 correspond to the –CH proton of [H1] glucosamide unit as well as the –CH proton of the azetidine ring so formed in the chitosan-azetidine derivative. The presence of the doublet from 2.23 to 2.11 confirms the presence of –CH2 proton of glucosamide unit and a singlet at 2.11 corresponds to the –CH2 protons of the TOSMIC moiety attached with azetidine core. A new peak at 0.93 belongs to the free alkyl group of the TOSMIC. Thus the 1HNMR hence proved the appropriate attachment of the substituted azetidine core to the Chitosan.

Elemental analysis

The results of the degree of substitution were shown in Table 1. Elemental analysis results showed the degree of substitution after modification in a compound. The content of the carbon and nitrogen were increased in the derivative as compared to the chitosan after modification, hence proved the possible substitution in the native compound. Through this analysis, the DS of chitosan-azetidine was obtained as 0.31.

Antifungal activity

Effect of chitosan derivative on fungal growth

In the present study the inhibitory effects of chitosan and chitosan derivative on radial fungal growth of A.fumigatus 3007 was examined at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml as depicted in Fig. 4 . The synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivative showed significant antifungal activity, as there was a visible reduction in the growth of fungal mycelia when compared to control (untreated-without test compound). The inhibitory effect was observed from 48 h only and antifungal inhibitory index was 26.19%. As depicted in Fig. 4. the antifungal effect of synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivative was significantly higher than chitosan. The effect of DMSO as a solvent was also examined on fungal growth at the concentration used and it was observed that DMSO did not have any inhibitory effect on the growth of fungus. The exact comparison of fungal growth inhibition by various chitosan derivatives may not be appropriate as several factors contribute towards the antifungal effect like concentration of derivative used, type of fungal strain examined, time duration of incubation, percentage of primary inoculum, solvent system of the chitosan polymer etc. However, the comparison of growth inhibition under similar assay conditions reported in literature highlight the antifungal potential of the reported chitosan derivative (Table 2 ).

Fig. 4.

The antifungal inhibitory index of chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative at 0.1 mg/ml concentration against Aspergillus fumigatus 3007.

Table 2.

Comparison of fungal growth inhibition by different chitosan complexes.

| Fungal strain | Chitosan complex (%) | Growth Inhibition (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria solani | 0.12 | 70.50 | Malerba et al., 2016 [26] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 0.12 | 73.50 | Malerba et al., 2016 [26] |

| Alternaria alternate | 0.10 | 82.20 | Saharan et al., 2013 [27] |

| Macrophominaphaseolina | 0.10 | 87.60 | Saharan et al., 2013 [27] |

| Rhizoctonisolani | 0.10 | 34.40 | Saharan et al., 2013 [27] |

| Aspergillus parasiticus | 0.20 | 50.00 | Cota-Arriola et al., 2013 [28] |

| Botrytis cinerea | 0.01 | 10.00 | Wei et al., 2021 [29] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 0.01 | 2.00 | Wei et al., 2021 [29] |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 0.01 | 26.19 | Present work |

*It is pertinent to mention that the biological activity of chitosan complex/derivative is dependent on several factors such as Mw and the type of fungus.

Effect of chitosan-azetidine derivative on fungal membrane

To further establish the effect of chitosan-azetidine derivative on fungal morphology, SEM studies were conducted. Morphological alterations after treatment with chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative were determined under SEM analysis Fig. 5 . SEM image of fungal hyphae grown in chitosan free media had a regular, cylindrical shape, homogenous and smooth exterior. However, one can observe remarkably induced morphological changes in fungal mycelia when grown in presence of chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative. Hyphae of A. fumigatus 3007 exposed to 100 μg/ml chitosan derivative became shriveled, contorted, rough and the surface was irregular with ruptures. These observations strengthen the role of chitosan-azetidine derivative as potential antifungal agent. These images directly establish the inhibitory effect of synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivative on fungal growth and morphology of fungal mycelia.

Fig. 5.

Scanning electron microscopic images of A. fumigatus 3007 control (A); after treatment with chitosan (B) and chitosan derivative (C).

Inhibition of fungal growth by chitosan-azetidine derivative was further investigated by images from confocal microscopy. It has been suggested that alterations in the expression levels of cell wall hydrolase genes in the presence of chitosan may disrupt the cell wall architecture, thereby increasing the sensitivity of fungal cells towards chitosan [30]. Additionally, Dias and co-workers [31] have also indicated interactions between chitosan and cell membrane structures, thus highlighting alterations in fungal membrane permeability leading to impairment of membrane function. Therefore, in the present study, the effect of chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative on fungal membrane integrity was examined by monitoring the influx of Propidium iodide (PI). PI is a membrane impermeable and DNA staining fluorescent probe. When PI enters into cells, it intercalates between the DNA bases and gives red fluorescence. To strengthen the understanding behind the mechanism of fungal inhibition by the synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivative, the treated fungal cells were exposed to PI. Slides were prepared for control (un-treated sample), chitosan treated and chitosan-azetidine derivative samples and observed using confocal laser scanning microscope Fig. 6. The control fungal mycelium did not show any detectable red colored hyphae, thus indicating an uncompromised and intact fungal membrane. In contrast to this, the chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative treated fungal mycelia when observed under fluorescent light depicted significant red coloration and when the bright field and fluorescent field section were merged it was completely apparent that the red fluorescence was being emitted from inside the fungal mycelia. The images suggest that the test compounds made the fungal membrane porous thus allowing the PI to enter cells resulting in the observed fluorescence. This membrane disruptive nature of the synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivative results in fungal growth inhibition. Previous studies have also reported alterations of fungal mycelium [32], [33], [34] by chitosan.

Fig. 6.

Effect of chitosan and chitosan-azetidine derivative on the cell membrane integrity of A. fumigatus 3007.

Conclusion

Substituted azetidine fused chitosan derivative was synthesized using multicomponent reaction and its structural properties was confirmed by means of different spectroscopic techniques, which is expected to be a new type of chitosan based antifungal. The degree of substitution and the introduction of highly substituted azetidine ring with complex hydrophobic aromatic substituent's in chitosan are all an important factor to enhance the antifungal potential. The results indicated that the chitosan-azetidine derivative showed antifungal effect with an antifungal inhibitory index of 26.19 %. The SEM and confocal microscopy images reflect a significant inhibitory effect of the synthesized chitosan-azetidine derivative on fungal mycelia and thus established the role of synthesized chitosan-derivative as a potential antifungal drug candidate.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors don't have any conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University (GGSIPU), New Delhi, India, for the financial support during the progress of the present work. Authors would also like to thank Mr. Naveen and Mr. Bharat for the analytical support of NMR and SEM data. The authors are also thankful to Dr. Tripti at Central Instrumentation Facility, University of Delhi South Campus for confocal images.

References

- 1.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Alhumaid S., Alshukairi A.N., Temsah M.-H., Barry M., Al Mutair A., et al. COVID-19 and mucormycosis superinfection: the perfect storm. Infection. 2021;49(5):833–853. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01670-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranjani J.M., Manuel A., Abdul Razack H.I., Mathew S.T. COVID-19-associated mucormycosis: evidence-based critical review of an emerging infection burden during the pandemic's second wave in India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009921. e0009921-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogdanic N., Mocibob L., Vidovic T., Soldo A., Begovać J. Azithromycin consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in Croatia, 2020. PLoS One. 2022;17(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263437. e0263437-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin Y., Li P., Guo Z. Cationic Chitosan Derivatives as Potential Antifungals: a Review of Structural Optimization and Applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;236 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kainz K., Bauer M.A., Madeo F., Carmona-Gutierrez D. Fungal infections in humans: the silent crisis. Microb Cell. 2020;7(6):143–145. doi: 10.15698/mic2020.06.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jing Y.-S., Ma Y.-F., Pan F.-B., Li M.-S., Zheng Y.-G., Wu L-F, et al. An Insight into Antihyperlipidemic Effects of Polysaccharides from Natural Resources. Molecules. 2022;27(6):1903. doi: 10.3390/molecules27061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khajavian M., Vatanpour V., Castro-Muñoz R., Boczkaj G. Chitin and Derivative Chitosan-based structures - Preparation Strategies aided by Deep Eutectic Solvents: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;275 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannan M., Ramu Ganesan A., Ezhilarasi P.N., Kondamareddy K., Karthick Rajan D., Sathishkumar P., et al. Green and eco-friendly approaches for the extraction of chitin and chitosan: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;287 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muxika A., Etxabide A., Uranga J., Guerrero P., de la Caba K. Chitosan as a bioactive polymer: processing, properties and applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;105(2):1358–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heras-Mozos R., Gavara R., Hernández-Muñoz P. Chitosan films as pH-responsive sustained release systems of naturally occurring antifungal volatile compounds. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;283 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali W., Elsahn A., Ting D.S.J., Dua H.S., Mohammed I. Host Defence Peptides: a Potent Alternative to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Antibiotics. 2022;11(4):475. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11040475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantini C., Veerdonk F.L., Romani L. Covid-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis: the Other Side of the Coin. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8(4):713. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon-Chung Kyung J., Sugui Janyce A. Aspergillus fumigatus—What Makes the Species a Ubiquitous Human Fungal Pathogen? PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verlee A., Mincke S., Stevens C. Recent developments in antibacterial and antifungal chitosan and its derivatives. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;164:268–283. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dananjaya S., Erandani W.K.C.U., Kim C.-H., Nikapitiya C., Lee J., De Zoysa M. Comparative study on antifungal activities of chitosan nanoparticles and chitosan silver nano composites against Fusarium oxysporum species complex. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;105:478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan S., Verma V., Kumar D., Gupta R., Gupta S., Bajaj A., et al. N-Heterocycles hybrids: synthesis, antifungal and antibiofilm evaluation. Synth Commun. 2022:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Łowicki D., Przybylski P. Tandem construction of biological relevant aliphatic 5-membered N-heterocycles. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;235 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couty F., Evano G. Azetidine-2-carboxylic acid. From Lily of the valley to key pharmaceuticals. A jubilee review. Org Prep Proced Int. 2006;38:427. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shukla P., Deswal D., Azad D.C., Narula A. Novel nucleosides as potential inhibitors of fungal lanosterol 14α-demethylase: an in vitro and in silico study. Future Med Chem. 2019;11(20):2663–2686. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2019-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shukla P., Deswal D., Pandit M., Latha N., Mahajan D., Srivast T., et al. Exploration of Novel TOSMIC Tethered Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine Compounds for the Development of Potential Antifungal Drug Candidate. Drug Dev Res. 2022;83(2):525–543. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dos Santos Z.M., Caroni A.L.P.F., Pereira M.R., da Silva D.R., Fonseca J.L.C. Determination of deacetylation degree of chitosan: a comparison between conductometric titration and CHN elemental analysis. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344(18):2591–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deswal D., Shukla P., Azad C.S., Narula A.K. Carbohydrate hitched imidazoles as agents for the disruption of fungal cell membrane. J Mycol Med. 2020;30(1) doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.100910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triana V., Ruiz-Cruz Y., Romero E., Zuluaga F., Chaur-Valencia M. New chitosan-imine derivatives: from green chemistry to removal of heavy metals from water. Revista Facultad de Ingenieria. 2018;89:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esquivel R., Juárez J., Almada M., Ibarra-Hurtado J., Valdez M. Synthesis and Characterization of New Thiolated Chitosan Nanoparticles Obtained by Ionic Gelation Method. Int J Polym Sci. 2015;7:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernabé P., Becherán L., Cabrera-Barjas G., Nesic A., Alburquenque C., Tapia C.V., et al. Chilean crab (Aegla cholchol) as a new source of chitin and chitosan with antifungal properties against Candida spp. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;149:962–975. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malerba M., Cerana R. Chitosan Effects on Plant Systems. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(7):996. doi: 10.3390/ijms17070996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saharan V., Mehrotra A., Khatik K., Rawal P., Sharma S.S., Pal A. Synthesis of chitosan based nanoparticles and their in vitro evaluation against phytopathogenic fungi. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;62:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villegas-Rascón R., López-Meneses A.K., Plascencia-Jatomea M., Cota-Arriola O., Moreno Ibarra G.M., Castillón-Campaña L., et al. Control of mycotoxigenic fungi with microcapsules of essential oils encapsulated in chitosan. Food Sci Technol. 2017;12/21:38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei L., Zhang J., Tan W., Gang W., Li Q., Dong F., et al. Antifungal activity of double Schiff bases of chitosan derivatives bearing active halogeno-benzenes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;179:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng D., Garba B., Ren Y., Yao M., Xia X., Li M., et al. Antifungal activity of chitosan against Aspergillus ochraceus and its possible mechanisms of action. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;158:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dias A.M., dos Santos Cabrera M.P., Lima A.M.F., Taboga S.R., Vilamaior P.S.L., Tiera M.J., et al. Insights on the antifungal activity of amphiphilic derivatives of diethylaminoethyl chitosan against Aspergillus flavus. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;196:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palma-Guerrero J., Huang I.C., Jansson H.-B., Salinas J., Lopez-Llorca L., Read N. Chitosan permeabilizes the plasma membrane and kills cells of Neurospora crassa in an energy dependent manner. Fungal genetics and biology. FG B. 2009;46:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olicon-Hernandez D.R., Hernandez-Lauzardo A.N., Pardo J.P., Pena A., Velazquez-del Valle M.G., Guerra-Sanchez G. Influence of chitosan and its derivatives on cell development and physiology of Ustilago maydis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;79:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger L., Stamford T., Oliveira K., Pessoa A., Lima M., Pintado M., et al. Chitosan produced from Mucorales fungi using agroindustrial by-products and its efficacy to inhibit Colletotrichum species. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;108:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]