Abstract

Lymph node status is an important prognostic factor in head and neck cancer. The purpose of this study is to investigate the prognostic value of lymph node density (LND) in node-positive oral cavity cancer patients who received surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy. From January 2008 to December 2013, a total of 61 oral cavity squamous cell cancer patients who had positive lymph node and received surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy were analysed. LND was calculated for each patient. The endpoints were 5-year overall survival (OS) and 5-year disease-free survival. All patients were followed for a period of 5 years. Mean 5-year overall survival for cases with LND of ≤ 0.05 was 56.1 ± 11.6 months, whereas mean 5-year overall survival for cases with LND > 0.05 was 40.0 ± 21.6 months. Log rank is 0.04 95% CI = 53.4–65. Mean 5-year disease-free survival for cases with LND of ≤ 0.05 was 50.5 ± 15.8 months, whereas mean disease-free survival for cases with LND > 0.05 was 15.8 ± 22.9 months. Log rank 0.03 95% CI = 43.3–57.6. Nodal status, disease stage and lymph node density were found to be significant predictors of prognosis in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, only lymph node density is found to be the predictor of prognosis. LND is an important prognosis factor for 5-year OS and 5-year DFS in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma.

Keywords: Lymph node density (LND), Prognostic factor, Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Head and neck cancer in India has emerged as a major public health problem which is related to life style, has a lengthy latent period and needs dedicated infrastructure for treatment [1] In India, oral cavity cancers constitute the major bulk of head and neck cancers and have distinct risk factors, food habits and personal history (tobacco) [2]. The head and neck region constitutes several delicate, intricately organised structures vital for basic physiological needs. It can also cause various degrees of structural and functional problems and handicaps with additional brunt on the quality of life [3].

Of global head and neck cancers (excluding oesophageal cancers), 57.5% occur in Asia especially in India [4]. In India, it accounted for 30% of all cancers in male and 11–16% in females. Nearly 80,000 oral cancers are diagnosed in India every year [5].

Although oral cavity is easily accessible for examination, majority of the cancers of the oral cavity present in advanced stage of the disease. As compared to Western world where approximately 40% of lesions present in advanced stage, 60 to 80% of patients present in advanced stage in India [6].

The mainstay of treatment of head and neck cancer is surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy as indicated by the pathological stage of the disease [7–9].

To date, the data to definitely identify risk factors of local and regional recurrences are lacking [10]. Five-year overall survival (OS) for patients of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) is about 60%, varying from 10 to 82% depending on stage, age, race, comorbidity and location in the oral cavity [11]. Even after receiving adequate treatment according to the stage, there are subgroups of patients who relapse and there are subgroups in the same stage who have better prognosis. Therefore, it is important to identify reliable and new prognostic factor to prognosticate patient into high and low risk and accordingly plan out the aggressiveness of the treatment and more stringent follow up regime.

Tumour node metastasis (TNM) staging system is most commonly used for staging the patient [12]. The TNM staging system classifies lymph node status according to number, size and laterality. According to this system, the presence of lymph node (LN) metastasis signifies poor prognosis and upstages the disease. However, the nodal stage by itself has not predicted prognosis reliably [13–16]. The number of metastatic lymph node and also the number of total lymph node harvested during neck dissection depends on the surgical competence of the.

surgeon as well as on the level of histopathological scrutiny [17, 18]. As limited lymph node dissection as well as histopathological sampling may result in pathological understaging, the need to identify another prognostic factor related to the lymph node is there.

Lymph node density (LND) is the ratio of total number of positive LN to the total number of LN harvested. This ratio attempts to compensate for the potential bias of the sampling method by utilising two information components: the regional spread of disease (number of positive nodes) and the surgical treatment (total number of lymph nodes excised during surgery) [19]. The aim of this study is to evaluate the prognostic significance of lymph node density in node-positive oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma patients for assessing 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and five-year overall survival (OS).

Patient and Methods

Patients with primary oral squamous cell carcinoma who were amenable to surgical resection from 2008 to 2013 were included in the study. Patients with multiple primary lesions; patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and N3 node; and those who required adjuvant chemoradiation (i.e. with nodal extracapsular extension and positive margin of resection of primary lesion) were excluded in the study. All the patients underwent a minimum of selective neck node dissection for clinically node-negative disease and comprehensive neck dissection for clinically evident nodal disease in addition to adequate wide excision of primary tumour. Tumour staging was done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging, 7th edition. Lymph node density was calculated as the ratio of total number of positive lymph nodes to the total number of lymph node harvested. In addition, other variables like tumour size, depth of infiltration, lymphovascular involvement and perineural involvement were also recorded. All patients received adjuvant radiotherapy.

All patients were followed for a period of minimum 5 years from the date of surgery and their disease course noted. Follow-up was done every 3 monthly for the first 2 years; every 4 monthly during third year and then 6 monthly until completion of 5 years or death of patient.

Five-year overall survival was calculated from the date of surgery to 5 years or patient death. Five-year DFS was calculated from the date of surgery to the occurrence of relapse of disease. Survival curves were plotted by Kaplan–Meier method. The clinicopathologic variables were expressed in median with range. Risk factors for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analysed by log rank test. The LND was dichotomised into.

either ≤ 0.05 or > 0.05. Any differences were statistically significant when p value was < 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 was used for data computation.

A total of 61 eligible patients were found and followed for a period of 5 years to calculate 5-year overall survival and 5-year disease-free survival.

Results

Median age of patients is 48 years (range 27–72). Out of 61, 52 (85.2%) were males and the rest females. Mean duration of follow-up is 45.31 months. Other clinicopathological variants are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | No. of patients | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 52 | |

| Female | 09 | ||

| Mean age | 49.67 years (range – 27 to 70) | ||

| H/o tobacco exposure | Yes | 52 | |

| No | 09 | ||

| T classification | 1 | 08 | |

| 2 | 13 | ||

| 3 | 01 | ||

| 4 | 39 | ||

| N classification | 1 | 24 | |

| 2a | 27 | ||

| 2b | 10 | ||

| 2c | 0 | ||

| Overall TNM stage | I | 0 | |

| II | 0 | ||

| III | 12 | ||

| IV | 49 | ||

| Treatment | Surgery only | 0 | |

| Surgery + radiation | 61 | ||

| Anatomical site | Buccal mucosa | 22 | |

| Tongue | 18 | ||

| Lower alveolus | 21 |

Median number of lymph nodes harvested during neck dissection is 31 (11–95). Median lymph node density is 0.07. The pN classification was pN1 (39.3%), N2a (44.3%) and pN2b (10%), respectively. The final tumour stage distribution was stage III (19.7%) and stage IV (80.3%).

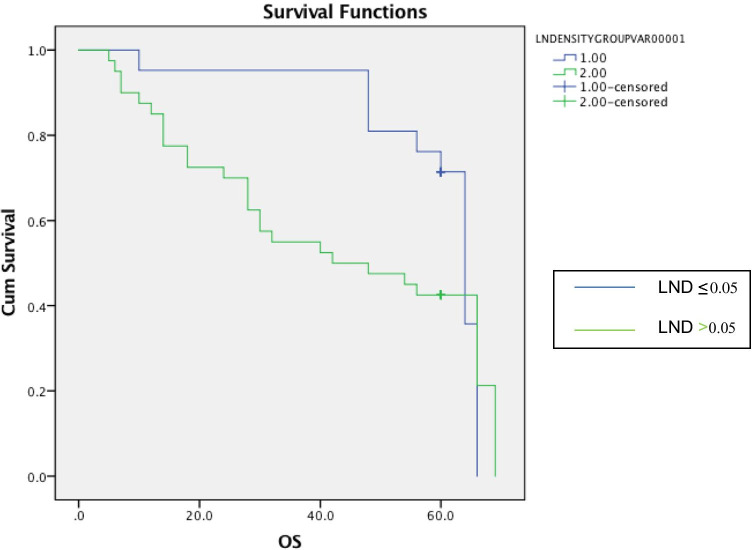

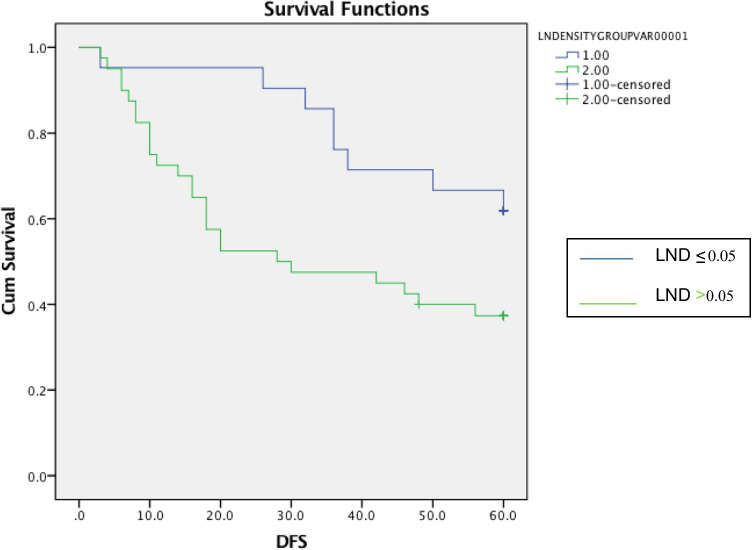

All patients were treated with surgery followed by radiation alone. At the end of 5 years of follow-up, local recurrence, regional recurrence and distant metastases occurred in 18 (29.5%), 2 (3.3%) and 7 (11.5%) patients, respectively. At the end of 5 years of follow-up, 31 patients were alive with 28 living without any disease recurrence while other 3 had recurrent disease. Thirty patients had mortality. The Kaplan–Meier curves of 5-year OS and 5-year DFS of patients with LND ≤ 0.05 and > 0.05 are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. The 5-year OS was 54% while 5-year DFS was 45.9%, respectively. Mean 5-year overall survival for cases with LND of ≤ 0.05 was 56.1 ± 11.6 months, whereas mean 5-year overall survival for cases with LND > 0.05 was 40.0 ± 21.6 months. Log rank is 0.04 95% CI = 53.4–65. Mean disease-free survival for cases with LND of ≤ 0.05 was 50.5 ± 15.8 months, whereas mean disease-free survival for cases with LND > 0.05 was 15.8 ± 22.9 months. Log rank 0.03 95% CI = 43.3–57.6.

Fig. 1.

The Kaplan–Meier curve of 5-year overall survival comparing LND ≤ 0.05 versus LND > 0.05

Fig. 2.

The Kaplan–Meier curve of 5-year DFS comparing LND ≤ 0.05 versus LND > 0.05

Discussion

The result of this study showed that lymph node density is also an important prognostic factor for 5-year OS and 5-year DFS in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. In this study, every effort has been taken to exclude all the factors which have already been known to affect the survival and disease-free interval in OCSCC. Therefore, patients with factors like positive margin of primary lesion and nodal extracapsular extension have been excluded in the study. Also this gives a homogenous study population, i.e. patients who have received only adjuvant radiation after surgical excision.

To our knowledge, few studies have analysed LND in patients with different head and neck cancer. Gil et al. [20] analysed 386 patients with oral cavity cancer who underwent primary surgery with or without adjuvant radiation and showed LND remained the only independent predictor of and local control (HR = 4.1, p = 0.005), disease-specific survival (DSS) (HR = 2.3, p = 0.02) and OS (HR = 2.0, p = 0.02). Kim et al. [21] analysed 211 patients with oral cavity cancer who underwent surgery and reported that LND was an independent predictor of DSS (HR = 3.24, 95% CI = 1.61–6.53; p = 0.001). In our study, we found LND is an independent prognostic factor for 5-year OS and 5-year DFS for OCSCC patients who received surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

The cut-off value for LND varied across various studies. Gil et al. [22] used a cut-off value of 0.06. Sayed et al. [23] reviewed data of 1408 oral cavity cancer patients and found LNR (0.088) significantly associated with survival. Hua et al. [22] analysed 81 hypopharyngeal cancer patients and found poor OS in patients with an LND ≧ 0.1 had poor OS. In our study, we used a cut-off value of 0.05 to categorise patients into LND > 0.05 group and LNR ≤ 0.05 groups. Shrime et al. [24] categorised oral SCC patients into low- (0–6%), moderate- (6–13%) and high-risk (> 13%) groups based on nodal ratio. Previous studies did not define a specific cut-off value for LND, but patients with a higher LND were shown to have poor survival.

Limitation to this study is the sample size, and hence, larger studies should be done to more authentically ascertain the prognostic value of lymph node density in OCSCC. But the advantage in this study is that the management protocol was consistent and exclusion criteria more stringent.

Conclusion

Our study ascertained the fact that lymph node density is also an important prognostic factor in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. As we know that cancer staging system is continuously evolving and in the 8th edition of the staging system, depth of invasion and extracapsular extension has been included; therefore, now the role of lymph node density should be taken into consideration to more diligently divide the patient into low-risk and high-risk group in the same stage so that follow-up and treatment protocol can be individualised.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the staff and patients at the Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and Medical Research Institute, Mumbai (Maharashtra), India, who helped collect data.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was taken from the institutional ethical and scientific committee regarding approval of the study.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the patients included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Manik Rao Kulkarni Head and neck cancer burden in India. Int J Head Neck Surg. 2013;4(1):29–35. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra A, Singh VP, Verma V (2009) Environment effects on head and neck cancer in India. J Clin Oncol 27 (suppl;abstr e17059)

- 3.Chaukar DA, Das AK, Deshpande MS, Pai PS, et al. Quality of life of head and neck cancer patient: validation of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30 and European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-HandN35 in Indian patients. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42(4):178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi P. Head and neck surgery. J Can Res Ther. 2009;5:143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Head and neck cancer in India. Available from: http://www.veedaoncology.com/PDF-Document/Head-Neck%20Cancer%20In%20India.pdf. [Last accessed on: 2011 Dec 26].

- 6.Kekatpure V, Kuriakose MA (2010) Oral cancer in India: ;learning from different populations. National newsletter and website from New York Presbyterian Hospital 14

- 7.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, Matuszewska K, Lefèbvre JL, Greiner RH, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH, Saxman SB, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper JS, Zhang Q, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Saxman SB, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RTOG 9501/Intergroup Phase III Trial: postoperative concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head & neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinn SB, Spector ME, Bellile EL, et al. Impact of perineural invasion in the pathologically N0 neck in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149:893–899. doi: 10.1177/0194599813506867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute (2006) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, National Cancer Institute Surveillance Research Program, based on November 2006 submission of SEER series 9 (1996–2003)

- 12.Patel SG, Shah JP. TNM staging of cancers of the head and neck: striving for uniformity among diversity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(4):242–258 . doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.4.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudoltz MS, Benammar A, Mohiuddin M. Does pathologic node status affect local control in patients with carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radical surgery and postoperative radiotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(3):503–508. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00394-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, Cassisi NJ, Million RR. An analysis of factors influencing the outcome of postoperative irradiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39(1):137–148. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavilan J, Prim MP, De Diego JI, Hardisson D, Pozuelo A. Postoperative radiotherapy in patients with positive nodes after functional neck dissection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109(9):844–848. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shingaki S, Takada M, Sasai K, Bibi R, Kobayashi T, Nomura T, Saito C. Impact of lymph node metastasis on the pattern of failure and survival in oral carcinomas. Am J Surg. 2003;185(3):278–284. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)01378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrama MT, Reiter D, Topham AK, Keane WM. Node counts in neck dissection: are they useful in outcomes research? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(4):433–435. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.114455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya N. The effects of more conservative neck dissections and radiotherapy on nodal yields from the neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(4):412–416. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel SG, Amit M, Yen TC, et al. International Consortium for Outcome Research (ICOR) in Head and Neck Cancer. Lymph node density in oral cavity cancer: results of the International Consortium for Outcomes Research. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2087–2095. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gil Z, Carlson DL, Boyle JO, Kraus DH, Shah JP, Shaha AR, et al. Lymph node density is a significant predictor of outcome in patients with oral cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:5700–5710. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SY, Nam SY, Choi SH, Cho KJ, Roh JL. Prognostic value of lymph node density in node-positive patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2310–2317. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua YH, Hu QY, Piao YF, Tand Q, Fu ZF. Effect of number and ratio of positive lymph nodes in hypopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2015;37:111–116. doi: 10.1002/hed.23574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayed SI, Sharma S, Rane P, Vaishampayan S, Talole S, Chaturvedi P, et al. Can metastasis lymph node ratio (LNR) predict survival in oral cavity cancer patients? J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:256–263. doi: 10.1002/jso.23387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrime MG, Bachar G, Lea J, Volling C, Ma C, Gullance PJ, et al. Nodal ratio as an independent predictor of survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Head Neck. 2009;31:1482–1488. doi: 10.1002/hed.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]