Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is a nosocomial pathogen highly resistant to environmental changes and antimicrobial treatments. Regulation of cellular motility and biofilm formation is important for its virulence, although it is poorly described at the molecular level. It has been previously reported that Acinetobacter genus specifically produces a small positively charged metabolite, polyamine 1,3-diaminopropane, that has been associated with cell motility and virulence. Here we show that A. baumannii encodes novel acetyltransferase, Dpa, that acetylates 1,3-diaminopropane, directly affecting the bacterium motility. Expression of dpa increases in bacteria that form pellicle and adhere to eukaryotic cells as compared to planktonic bacterial cells, suggesting that cell motility is linked to the pool of non-modified 1,3-diaminopropane. Indeed, deletion of dpa hinders biofilm formation and increases twitching motion confirming the impact of balancing the levels of 1,3-diaminopropane on cell motility. The crystal structure of Dpa reveals topological and functional differences from other bacterial polyamine acetyltransferases, adopting a β-swapped quaternary arrangement similar to that of eukaryotic polyamine acetyltransferases with a central size exclusion channel that sieves through the cellular polyamine pool. The structure of catalytically impaired DpaY128F in complex with the reaction product shows that binding and orientation of the polyamine substrates are conserved between different polyamine-acetyltransferases.

Subject terms: Bacteriology, X-ray crystallography, Enzymes, Biofilms

Acinetobacter baumanii has an uncharacterized surface-associated motility which is a feature of its persistence. Here, Armalytė et al identify an acetyltransferase that affects this motility and present a functional and structural characterisation of it

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant A. baumannii is a notorious hospital-acquired pathogen primarily causing ventilator-associated pneumonia and sepsis. It prevails in the environment by forming biofilms and resisting desiccation1,2. The name Acinetobacter is derived from the greek words motion (“kineto”) and rod (“bakter”) and means non-motile bacterium. Nevertheless, despite the lack of flagella, A. baumannii possesses an uncharacterized surface-associated motility, which is recognized as one of the key molecular features that promote its environmental persistence2. The short polyamine 1,3-diaminopropane (1,3-DAP) is produced almost exclusively by the Acinetobacter genus3 and has been linked to surface-associated motility and virulence4,5. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of motility by 1,3-DAP has not been investigated. One hypothesis proposed that 1,3-DAP or its derivative could function as a signaling molecule via quorum sensing2. Polyamines are versatile, small positively charged (polycationic) molecules, that participate in global cellular processes such as transcription, translation, cell proliferation or stress resistance6–8. Most importantly, in several bacterial pathogens production of polyamines has been associated with virulence7,9,10. The regulation of polyamine profiles in bacteria is largely attributed to polyamine acetyltransferases, typically annotated in bacteria as SpeG (for Spermidine acetyltransferase)11–13. Intriguingly, Acinetobacter species do not produce any of the common bacterial polyamines, such as spermidine, cadaverine or putrescine3 and do not encode the orthologues of speG acetyltransferase genes. As a result, an alternative acetyltransferase must exist to regulate the turnover of the Acinetobacter-specific polyamine 1,3-DAP and convert it to its inert form. Here we have uncovered a GNAT-family acetyltransferase conserved in A. baumannii that is responsible for the acetylation of 1,3-DAP in A. baumannii in vivo and in vitro and renamed accordingly as Dpa for diamino-propane acetyltransferase. As compared to activity of other bacterial acetyltransferases Dpa shows the highest specific activity towards 1,3-DAP. Our structural work revealed that Dpa is distinct from SpeG with a topology closer to eukaryotic polyamine acetyltransferases SSAT (Spermidine/Spermine N-acetyltransaferase) and Hpa2 (Histone acetyltransferase). Structures of catalytically impaired DpaY128F bound to its substrate polyamine trapped in pre- and post-catalytic states suggest that the mode of binding and orientation of the polyamine substrate and acetyl moiety of acetyl-CoA is shared between the different polyamine acetyltransferases.

Dpa is expressed during stationary phase and is strongly upregulated in bacteria adhering to eukaryotic epithelial cells and in bacterial pellicle formed on liquid surfaces as compared to planktonic bacteria. In agreement with previous findings that suggested the 1,3-DAP involvement in motility, we show that the chromosomal deletion of A. baumannii 1,3-DAP acetyltransferase gene dpa enhances motility and negatively affects biofilm formation on plastic. These results indicate that acetylation of 1,3-DAP is important in both, biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and in adherence to eukaryotic cells during infection.

Results

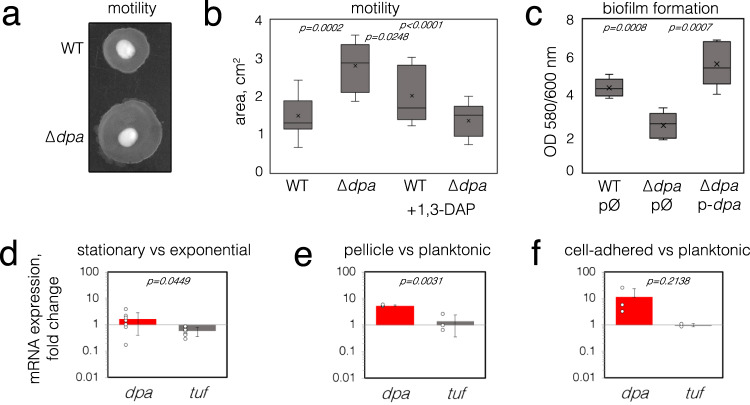

Biofilm formation and cell motility are controlled by Dpa

The short polyamine 1,3-DAP has been previously associated with cell motility in Acinetobacter4, however little is known about its regulation. In Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. the levels of polyamines are controlled by their acetylation thus converting them to an inert form11,12. We looked for acetyltransferase enzymes that could perform this function in Acinetobacter genus. However, a standard BLAST search of acetyltransferase homologous to the well-characterized E. coli, Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia pestis or Staphylococcus aureus polyamine acetyltransferases SpeG did not retrieve any candidates. We compared the sequences of putative GNAT proteins from Acinetobacter without predicted function and found distant but significant homology of one such candidate, previously annotated as CheA (renamed here as Dpa), to SpeG (16,8% identity) or eukaryotic SSAT polyamine acetyltransferase (17.2% identity)14–16. BLASTN analysis of available A. baumannii strains (515 as of December 2022) showed that the dpa gene was present in all sequenced strains and its nucleotide sequence was conserved with more than 95% identity. We next constructed a genomic knockout of dpa to assess its role in the regulation of cell motility in the context of a potential role in the control of 1,3-DAP levels4. A clinical A. baumannii isolate, belonging to international clone ICI was chosen, as it was previously shown that the isolates belonging to this international clone possess twitching motility, as opposed to the majority of isolates of international clone ICII17. Indeed, A. baumannii deleted for dpa migrated further under semi-liquid agar as compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 1a), indicating that the cellular expression of dpa represses a bacterial movement known as twitching motility. By contrast, when 1,3-DAP was added to the medium, twitching motility despite high variability was slightly increased for WT but not for dpa-deleted A. baumannii (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. The influence of dpa on cell motility and biofilm formation.

a A representative image of changes in A. baumannii dpa mutant twitching motility as seen on the TSB agar plate. b The twitching motility of A. baumannii was quantified by measuring the halo of growth around the inoculation site (n = 9) and expressed in cm2. The bacteria were grown with or without 0.1 mM of 1,3-DAP added to the media. c The biofilm formation analysis of A. baumannii dpa mutant and strains with complementing plasmids. The A. baumannii strains with empty (gfp instead of dpa) or dpa-containing plasmids were inoculated to 96-well polystyrene plates, and the expression of plasmid-encoded genes was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG. Biofilm formation was measured after 18 h of growth at 37 °C by removing the planktonic cells and staining the formed biofilms with crystal violet (n = 5). Values were normalized to the optical density of the planktonic bacteria recovered from the well. Top and bottom of the box plot whiskers show maximum and minimum values of the samples, top and bottom of the box − 75th percentile and 25th percentile respectively. Line through the box and x markers show the median and the mean of the sample respectively. d–f The changes in A. baumannii dpa expression in different conditions. The relative expression of dpa was analyzed by RT-qPCR, the differences in transcript amounts were evaluated by the comparative Ct method (ΔΔCt) using rpoB as a housekeeping gene. EF-Tu gene (tuf) was used as a control. Seven biological replicas were performed in (d) and three biological replicas were performed in (e, f). Error bars show standard deviations, two-tailed P values (unpaired t-test) are indicated above the plots. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Biofilm formation is intrinsically linked to cell motility as it requires undergoing the switch between exploration and colonization18. Indeed, deletion of dpa had an opposite effect on biofilm formation than cell motility–dpa-mutant cells formed less biofilm and the expression of the dpa gene from plasmid could compensate for this effect (Fig. 1c). Overall, these results indicate a direct link between the regulation of cell motility and biofilm formation and the activity of Dpa.

dpa is expressed during the stationary phase and pellicle-type biofilms

Given that the presence of dpa was important for the regulation of motility, we wanted to know if this gene was indeed expressed in A. baumannii under conditions that would trigger a motility-related response from the cells. We found that the expression of dpa was slightly elevated in the stationary phase (by 1.6 fold; Fig. 1d) and highly elevated in pellicle-type biofilm formed on the liquid surface (by 5.3 fold; Fig. 1e), as well as in A. baumannii that have adhered to eukaryotic cells as compared to the expression in the planktonic cells (by 11.2 fold; Fig. 1f). These findings suggest that Dpa is active in the static cells and triggers a decrease in cellular motility.

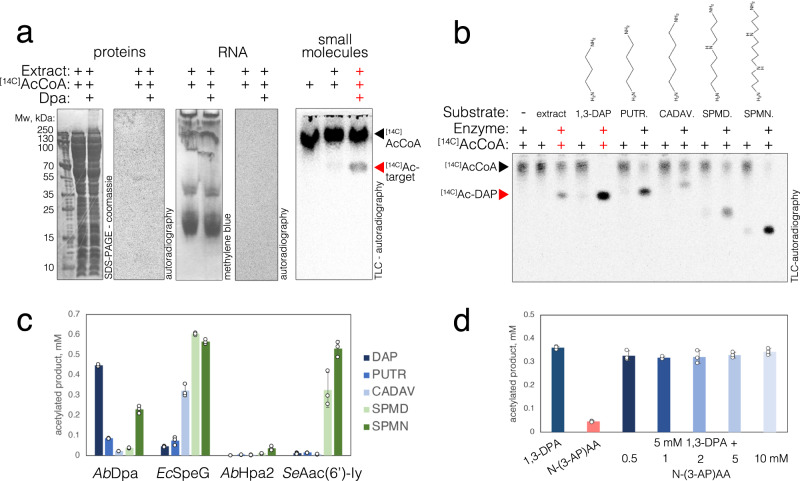

Dpa is an acetyltransferase specific to a substrate in A. baumannii

GNATs are known to target various substrates from small molecules to proteins by transferring an acetyl moiety to free amine groups19,20. To probe the activity of A. baumannii Dpa we used [14 C]acetyl-Coenzyme A as the acetyl-donor to acetylate the cellular extract of A. baumannii ∆dpa cells. Analysis of proteins and nucleic acids revealed no signal of acetylation (Fig. 2a), suggesting they are not the target of Dpa. We then separated the metabolite pool from the macromolecules in the cellular extract of A. baumannii by filtering out molecules with molecular weight above a 3 kDa and assayed the activity of Dpa on this sample in the presence of [14 C]acCoA. The reaction pattern revealed by thin layer chromatography, showed a band emerging from incubation of small molecule filtrate with [14 C]acCoA and Dpa enzyme (Fig. 2a). Importantly, this product was not formed when incubating E. coli small molecule extract with Dpa and [14 C]acCoA (Supplementary Fig. S1). This suggests that the low molecular weight target of Dpa is produced in A. baumannii but not in E. coli.

Fig. 2. Detection of Dpa enzyme substrate.

a Protein (left), RNA (center) and small molecule (right) extracts from exponential phase of A. baumannii cells cultured in liquid LB media were subjected to acetylation assays with purified Dpa enzyme and isotope labelled [14 C]acCoA. Proteins were then migrated on SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie; RNA was migrated on PAGE gel and stained with methylene blue. Small molecules were migrated on thin layer chromatography plate. Gels and TLC plates were dried, and isotope signals were revealed with autoradiography. Results were reproduced three times independently; representative gels and plates are shown. b Small molecules from A. baumannii cellular extract and commercial polyamine substrates: 1,3-diaminopropane (1,3-DAP), putrescine (PUTR.), cadaverine (CADAV.), spermidine (SPMD) and spermine (SPMN) were subjected to acetylation assays with purified Dpa enzyme and isotope labelled [14 C]acCoA for 30 min at 37 °C. Reactions were migrated on TLC plate and revealed by autoradiography. Structural formulas of polyamines are indicated on top of the gel. c Acetylation of polyamines by bacterial GNAT acetyltransferases – A. baumannii Dpa, E. coli SpeG, A. baumannii Hpa2 and S. enterica Aac(6’)-Iy. Final concentration of 5 mM of different polyamines were incubated with 0.5 mM of acCoA and 2 µM of enzymes for 30 min at 30 °C and acetylation was revealed with DTNB reagent as described in the methods section. d Acetylation of 1,3-DAP as compared to mono-acetylated 1,3-DAP (N-(3-aminopropyl)acetamide) indicated as N-(3-AP)AA. Reactions were performed as mentioned above, except that an increasing amount of N-(3-AP)AA was pre-mixed with the enzyme before the reaction (when indicated), otherwise 5 mM of substrates were used. Each reaction was performed three times over independent experiments, error bars show standard deviation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

1,3-DAP is a primary substrate of Dpa

1,3-DAP is specific to Acinetobacter genus, which lack other longer-chain bacterial polyamines, such as spermidine, cadaverine or putrescine3. Having found that the substrate of Dpa was a small molecule specific to A. baumannii, involved in the regulation of motility and biofilm, we directly used a set of polyamines as a control in the acetylation assays using Dpa and [14 C]acCoA (1,3-DAP, putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine and spermine). The analysis of the acetylation pattern of control polyamines vs. the Dpa-treated extract from A. baumannii strongly indicated that the molecule 1,3-DAP is the cellular target of the enzyme (Fig. 2b). While Dpa also acetylated other polyamines, they were not detected in the molecular extract of A. baumannii grown in liquid LB. Apart from spermine that repressed the twitching, the addition of other polyamines did not impact the twitching motility or biofilm formation capacity of WT or dpa-deficient strains (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, our in vitro data supports the possibility that Dpa could acetylate other polyamines under certain conditions, such as host polyamines encountered during the infection.

At high concentration, polyamines and histones are spontaneously acetylated nonenzymatically21,22. Adding polyamines in higher quantities strongly affects the pH of the reaction. However, buffering the polyamines had a strong effect on the enzyme activity. We observed a sharp increase in Dpa activity between pH 8 and 9 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, to avoid nonenzymatic acetylation, we measured the kinetics of 1,3-DAP conversion to [14 C]ac-1,3-DAP at a suboptimal pH 8.5 at 22 °C. The measured Vmax = 50.5 µM/min and Km = 84.9 µM revealed that the enzyme is highly active at large excess of 1,3-DAP (Supplementary Fig. S3). In unbuffered conditions, the excess of polyamine would also increase the pH and in turn the activity of Dpa would convert the 1,3-DAP to acetyl-diaminopropane faster and thereby regulate its levels. These results showed that Dpa specifically controls the pool of 1,3-DAP vs. Ac-1,3-DAP in A. baumannii. We used N–(3-aminopropyl)-acetamide (mono-acetylated 1,3-DAP), as reaction substrate to assess whether Dpa could produce both mono- and di- acetylated products. We found that N–(3-aminopropyl)-acetamide was a very poor substrate for Dpa (Fig. 2d). Further increase in concentration of the reaction product did not inhibit the enzyme’s activity (Fig. 2d). This suggested that mono-acetylated-DAP is the major product of the reaction (Fig. 2d).

Dpa has a narrow specificity

While Dap showed some activity on other polyamines, we wanted to characterize its substrate specificity range and to assess whether other acetyltransferases could also target 1,3-DAP. In agreement with previous reports, the well-described E. coli polyamine acetyltransferase SpeG acetylated the long polyamines Spermine and Spermidine, however its activity was significantly lower on short-chain polyamines, and the 1,3-DAP was the worst substrate among all tested (Fig. 2c). Previously it has been reported that A. baumannii encodes broad specificity GNAT family acetyltransferase with suggested similarity to yeast Hpa223–25. In contrast to previous reports24,25, we did not find any significant activity of A. baumannii Hpa2 on any of the polyamines tested, including 1,3-DAP, nor on any aminoglycoside antibiotics tested (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. S4). Dpa expression in E. coli also did not confer resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. In agreement with these findings, Dpa did not acetylate streptomycin, kanamycin, gentamicin, tobramycin or amikacin in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S4). The Salmonella enterica Aac(6’)-Iy enzyme was used as a control for these experiments26,27. Aac(6’)-Iy acetylated all the aminoglycosides tested, except streptomycin and its expression in E. coli conferred increased MIC to all the aminoglycosides that it could acetylate (Supplementary Fig. S4). Aac(6’)-Iy could also acetylate long polyamines spermine and spermidine, but not the short ones – cadaverine, putrescine or 1,3-DAP (Fig. 2c). The structure of Hpa2Ab predicted by AlphaFold2 suggested structural similarity to S. aureus SACOL1063 acetyltransferase28 (Supplementary Fig. S5). We therefore confirmed that the purified Hpa2Ab enzyme was active and similarly to its homologue could acetylate threonine and some other amino acids (Trp, Tyr, Ser, Arg, His) (Supplementary Fig. S5). Once again, Dpa had no activity on amino acids, in contrast to E. coli SpeG which showed some activity on the same subset of amino acids as Hpa2Ab (Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition to polyamines and amino acids, SpeG could efficiently acetylate the polyamine synthesis precursor agmatine (Supplementary Fig. S5). Altogether our findings suggested that 1,3-DAP is the main target of Dpa enzyme and that this enzyme evolved specifically to acetylate 1,3-DAP, contrasting with other GNAT enzymes subfamilies (Fig. 2c).

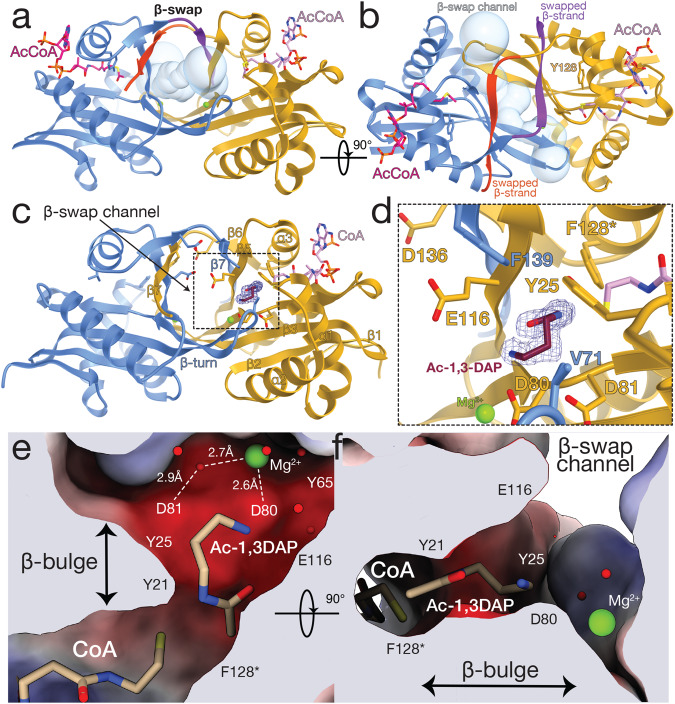

The structure of Dpa revealed a β-strand swapped dimer

Dpa shared low sequence identity with other bacterial and eukaryotic polyamine acetyltransferases with the most conserved region associated to acCoA binding (Supplementary Fig. S6). To better understand its structure-function interplay, we determined the structure of Dpa bound to acCoA (Fig. 3a, b). Dpa had an overall topology common to GNAT family acetyltransferases (Fig. 3a, b)29,30. Unlike SpeG acetyltransferases that form higher oligomers31–33, Dpa formed a dimer through a C-terminal β-strand swap (Fig. 3a, b). This dimeric state was stable in solution and was not influenced by the presence of substrates acCoA and or 1,3-DAP (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Fig. 3. Structure and substrate binding properties of Dpa enzyme.

a Dpa is a GNAT-fold acetyltransferase that forms a β-swapped dimer. b The C terminal β-strand exchange forms a channel opening to the active site residues Y128 and acetyl moiety of acCoA. c, d acetylation of 1,3-DAP substrate by Dpa enzyme. The contour of 2Fo-Fc map at 1.0σ of acetylated substrate is shown in blue mesh. e, f Mg2+ ion and network of water molecules at the active site of Dpa coordinate the acetylation of 1,3-DAP. The active site pocket is colored by charge distribution. Substrate-orienting residues are labeled, active site residue substitution Y128F is labeled with an asterisk.

This β-strand swap completed a solvent-exposed, negatively charged β-barrel-like channel that communicated the active sites of the enzyme and the acetyl-moiety of acCoA with the bulk solvent (Fig. 3a, b). The acidic nature of the channel likely facilitated the access of basic polyamines into the reaction center. Indeed, a similar acidic structure has been reported for other acetyltransferases34–37. The dimensions of the β-swap channel contiguous to the constricted reaction center likely favored the specificity of Dpa for the smaller 1,3-DAP polyamine. Likely, these channel features also played a role in the exit of the acetylated amines, with diminished basic properties, upon Dpa modification. Collectively these observations indicate that the β-swap interface is a distinctive functional structure of these type of GNAT polyamine acetyltransferase enzymes.

Dpa orients polyamines similar to eukaryotic SSAT

To gain insights into the catalytic mechanism of Dpa, we used a catalytically impaired version of the enzyme carrying Y128F mutation that allowed us to determine the structure of Dpa bound to 1,3-DAP and acCoA. The crystals of DpaY128F grown in the presence of acCoA were soaked between 30 s and 1 min with 1,3-DAP before vitrification in liquid N2. The compromised activity of DpaY128F (Supplementary Fig. S8) allowed us to observe the post-catalysis state of the reaction with Ac-1,3-DAP bound to one of the two DpaY128F of the dimer (Fig. 3c, d). The other monomer of DpaY128F was bound to 1,3-DAP that was oriented slightly differently in the active site (Supplementary Fig. S9). Binding of the polyamine pre- or post-catalysis did not introduce major structural rearrangements (Supplementary Fig. S9). Interestingly, the orientation of 1,3-DAP in the active site of Dpa observed in the crystal structure (Fig. 3c, d) was similar to that observed in mouse polyamine acetyltransferase SSAT14, suggesting that these subfamilies are functionally related.

The active center of Dpa is very acidic and involves residues Y21, Y25, Y65, Y128, D80, D81, E116 (Fig. 3d). Two densities corresponding to metal ions occupied symmetrical positions at the dimer interface and coordinate D80 and D81, damping the negative charges of the active site. These ions hold together a network of water molecules that connected and accommodated the polyamine substrate (Fig. 3e). We speculate that these ions could be Mg2+, however we could not confirm their role in the catalysis, since prolonged incubation with EDTA did not reduce the activity of the enzyme (Supplementary Fig. S8). Nevertheless, the structure indicated a “pulling” effect of each of these ions on D80-D81 that disturbs an otherwise long β-strand introducing a bulge that is transmitted to the neighboring β-strand (Fig. 3e, f). This bulge defines the enzyme’s substrate binding site and stabilizes the acetyl group of acCoA in the proper orientation (Fig. 3e, f). At the other end of the active site, 1,3-DAP is stabilized by contacts to E116 of one subunit and F139 of the other, both located at the narrow entrance of the β-swap channel, together with α1 Y25 and V71 of the β3-β4 turn. This architecture defines the pocket that accommodates the substrate and likely provides specificity to the enzyme.

In contrast to Dpa, which is a constitutive dimer (Supplementary Fig. S7), polyamines modification by SpeG seems to require conserved large oligomeric structure–polyamines bind in the interface between monomers and induce a shift of the active site loop that resounds on the overall ring-like structure and is required for catalysis36. In agreement with our findings using E. coli SpeG (Fig. 2c), it has been previously shown that V. cholerae SpeG could only acetylate long polyamines such as spermidine or spermine31. This oligomeric architecture of SpeG is directly linked to the regulation of the enzyme. It has been shown that an increase in polyamine concentration induces a structural shift that regulates the opening/closing state of the dodecameric ring required for catalysis31,36. While the structure of Dpa suggested that catalysis does not involve major structural rearrangements (Supplementary Figs. S7, S9), our kinetics data showed that substrate concentration, temperature as well as pH, are important for the activity of the enzyme (Supplementary Fig. S3).

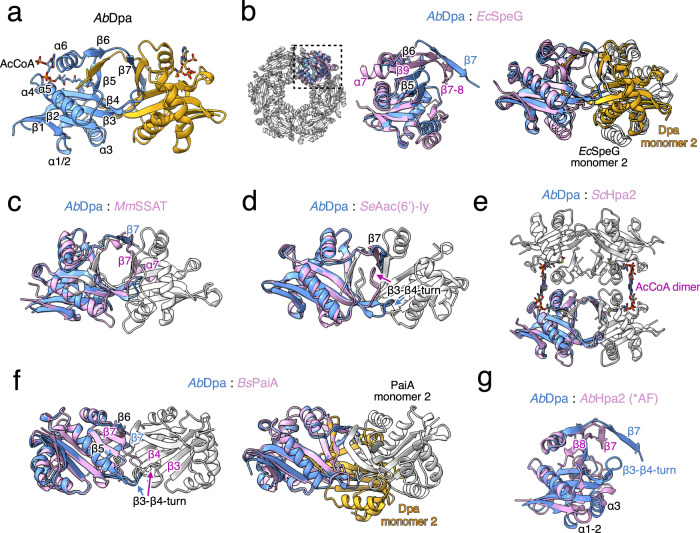

Dpa is structurally related to eukaryotic acetyltransferases Hpa2 and SSAT

Dpa is a functional dimer (Fig. 4a, b), contrasting with the large dodecameric arrangements observed in E. coli and V. cholerae SpeG and other bacterial homologues31,36,38. Strikingly, Dpa has the same quaternary arrangement of a C-terminal β-strand swapped dimer of eukaryotic SSATs from mouse and human14,34 also seen in yeast Hpa239 and S. enterica Aac(6’)-Iy27 (Fig. 4c–e). However the yeast Hpa2 further tetramerizes despite having the overall highest structural similarity with Dpa39 (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. S6).

Fig. 4. Comparison of bacterial and eukaryotic polyamine acetyltransferases.

a Secondary structure elements of Dpa; α-helices and β-strands are indicated on one monomer (shown in blue). b Structure alignments of A. baumannii Dpa and E. coli SpeG (PDB: 4R9M) monomers (left) and dimers (right). c Structure alignment of Dpa with mouse SSAT (PDB: 3BJ7), (d) S. enterica Aac(6’)-Iy (PDB: 1S5K), (e) yeast Hpa2 (PDB: 1QSO), (f) B. subtilis PaiA (PDB: 1TIQ) monomer (left) or dimer (right) and (g) AlphaFold259 model of A. baumannii Hpa2. Dpa monomers are colored in blue and yellow; other acetyltransferases are colored in pink for the monomer aligned and white for the rest. Sequence alignments and detailed alignments of each monomer with r.m.s.d. values are provided in Supplementary Fig. S6.

The SpeG dodecamers, are composed of 6 dimer units formed via a similar interface as in Dpa, but without β-strand exchange and in a slightly twisted orientation (Fig. 4b). B. subtilis spermine-spermidine acetyltransferase PaiA also dimerizes without β-strand swapping, which brings the two monomers closer and twists the dimer interaction surface even more as compared to Dpa (Fig. 4f). Finally, we have found that the A. baumannii AbHpa2 was a monomer in solution (Supplementary Fig. S7). The structural model predicted by AlphaFold2 suggests a compact C-terminal structure, similar to that observed in S. aureus SACOL1063 (Supplementary Fig. S5). Nevertheless, monomers of all these enzymes could be aligned through central β-sheet and four major ɑ-helices (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S6).

This seven-stranded β-sheet topology of GNAT enzymes is conserved in all polyamine acetyltransferases with major topology rearrangements observed at the C-terminus. In SpeGs, as well as AbHpa2 and BsPaiA after a sharp turn, the last β-strand inserts itself between the β6 and β5 (Fig. 4b, f, g, Supplementary Fig. S6). By contrast, the last β-strand of Dpa detaches from the protein intercalating between β6 and β5 of the neighboring Dpa subunit (Fig. 4a). A comparable dimer formation is seen in yeast Hpa2, mammalian SSATs, as well as S. enterica Aac(6’)-Iy (Fig. 4c–e). SSATs however have an extra C-terminal α-helix that docks together with β7 against the other subunit of the dimer (Fig. 4c).

The major topological difference of polyamine acetyltransferases is dictated by the β-turn between the β-strands β3 and β4 (Supplementary Fig. S6). This variable loop defines the distance of two monomers and forms the bottom of the substrate entry channel. In dodecameric SpeGs, as well as in dimeric BsPaiA and monomeric AbHpa2, this β3-β4 turn is twisted inwards (Fig. 4b, f, g, Supplementary Fig. S6). By contrast in Dpa and other dimeric GNATs the β3- β4 turn extends as far as the C terminal β-swap and together these extensions form a central substrate entrance hole (Fig. 4a, c–e). As compared to Dpa and eukaryotic polyamine acetyltransferases, the aminoglycoside acetyltransferase Aac(6’)-Iy possesses very large β-turn that is flipped upwards blocking the central hole, and opening access to the active site from the other side of the turn (Fig. 4d).

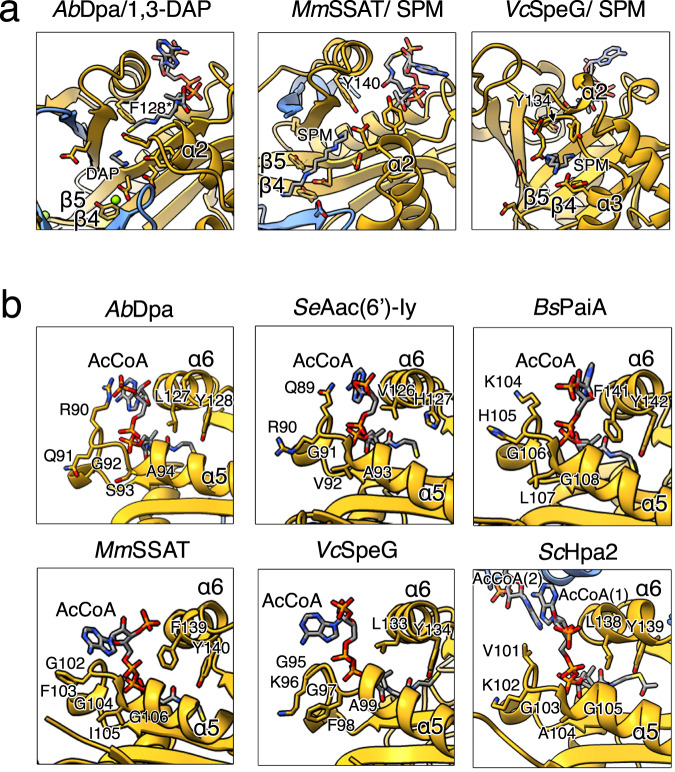

Dpa shares substrate binding properties with other polyamine acetyltransferases

The substrate-bound structures of Dpa, mouse SSAT14 and V. cholerae SpeG36 show that polyamine acetyltransferases bind their substrates through their acidic pockets. Negatively charged residues are mostly located on the β3 and β4 strands and at the inner side of α-helices α2 or α3 in the case of SpeG (Fig. 5a). Polyamines likely enter through the acidic β-swap channel of the dimeric Dpa and SSATs, while in the torus-shaped SpeGs they are suggested to travel through the central negatively charged hole of the dodecamer36.

Fig. 5. Polyamine and acCoA binding properties of different acetyltransferases.

a Zoom in on the polyamine binding sites of A. baumannii Dpa (left), mouse SSAT (center, PDB: 3BJ8) and V. cholerae SpeG (right, PDB: 4R87). Acidic residues surrounding the 1,3-diaminopropane (DAP) or spermine (SPM) and catalytic tyrosine (mutated to F128 in case of Dpa, otherwise Y140 and Y134 for MmSSAT and VcSpeG respectively) are shown. b AcCoA coordination by Dpa as compared to S. enterica Aac(6’)-Iy (PDB: 1S5K), B. subtilis PaiA (PDB: 1TIQ), mouse SSAT (PDB: 3BJ7), V. cholerae SpeG (PDB: 4R87) or yeast Hpa2 (PDB: 1QSM). Conserved P-loop residues located between ɑ-helices α4 and α5 and catalytic tyrosine or histidine residues located on the α6 helix are indicated.

At the co-factor site, located opposite to the substrate-binding site, the cysteamine moiety of CoA protrudes into the catalytic center connecting with the polyamine substrate. Overall, acCoA binding is similar in all GNATs except for the coordination of the phosphoadenosine groups (Fig. 5b). In SpeG and SSAT the base is coordinated by the highly conserved P-loop sequence located between the α4 and the α5 helices and the phosphate group contacts α-helix α6 (Fig. 5b). By contrast, in Dpa, Aac(6’)-Iy and PaiA the phosphoadenosine is docked entirely against α-helix α6 due to the divergent sequence of the P-loop, where the first residue in canonic [GxGx(A/G)] motif G is substituted by a large and charged reside. The large R90 sidechain in Dpa pushes the adenosine moiety against the α6 α-helix (Fig. 5b). Additionally, this orientation does not support the tetramerization seen in yeast Hpa2 which has V101 at the first position of the P-loop. The adenosine moiety of ScHpa2 is pushed to extend further out supporting the interaction with the acCoA of another monomer and thereby locking the two dimers together39 (Fig. 5b). All these observations show that Dpa is a functionally and structurally divergent bacterial polyamine acetyltransferase, with overall stronger similarity to eukaryotic polyamine acetyltransferases SSAT or Hpa2 than to prokaryotic SpeG or PaiA.

Discussion

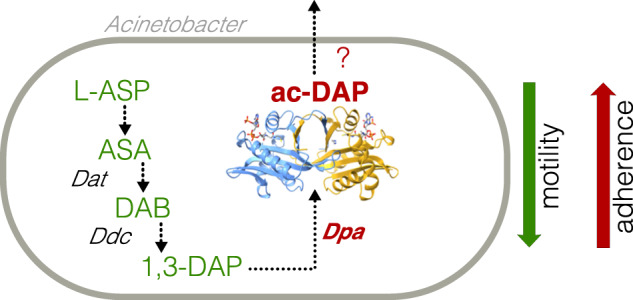

The ability to form biofilms is an important adaptation for A. baumannii survival in hospital environments as it protects the cell from extracellular stresses and prevents penetration of antibacterial chemicals, thus increasing resistance2,40. Biofilm formation is also tightly connected to cell motility as a decision between sessile and motile lifestyles18. A. baumannii possesses a unique polyamine, 1,3-DAP, synthesized from aspartate semialdehyde by the action of two enzymes - dat and ddc41,42. This polyamine has been associated with cell motility and was found to be important for the virulence of A. baumannii in the Galleria mellonella infection model4. In this study, we have found a downstream regulatory element in this pathway: the polyamine acetyltransferase Dpa that specifically acetylates 1,3-DAP in A. baumannii to control the effective levels of the metabolite (Fig. 6). We showed that A. baumannii extracts lack other polyamine acetylation signals by Dpa, suggesting that its primary substrate is 1,3-DAP. Despite the previous report that Hpa2-like enzyme could acetylate polyamines in A. baumannii25, we found that it targets amino acids (Supplementary Fig. S5), and thus Dpa is so far the only A. baumannii polyamine acetyltransferase (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 6. The proposed function of the Dpa enzyme in A. baumannii.

1,3-diamino propane (1,3-DAP) is synthesized from L-Aspartate (L-Asp) through L-aspartate 4-semialdehyde (ASA) and L-2,4-diaminobutanoate (DAB) intermediates, by a function of diaminobutyrate aminotransferase (Dat) and 2,4-diaminobutyrate decarboxylase (Ddc). Conserved and specific diaminopropane acetyltransferase (Dpa) acetylates and neutralizes 1,3-DAP which could be excreted. 1,3-DAP has been previously linked to surface-associated motility, while its acetylation by Dpa has the opposite effect limiting motility and increasing adherence.

The structure of Dpa revealed a dimeric architecture with a conserved acCoA and an acidic polyamine binding site formed at the dimer interface that shares properties with other polyamine acetyltransferases. However, these enzymes diverged in topology towards the C-terminal region, which is crucial for oligomerization and substrate specificity. In Dpa, like in SSATs, a swapped dimer is formed by the β-strand exchange, while bacterial SpeG-like enzymes adopt large torus-shaped oligomeric structures. The local structure formed between the β-swapped strands and the β3-β4 turn is likely the key player defining the specificity of Dpa and regulating the size of the substrate polyamines, which contrast with the substrate specificity of other bacterial GNAT acetyltransferases (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Figs. S4, S5). Thus, Dpa is structurally distant from the traditional bacterial polyamine acetyltransferases and closer to the well-known eukaryotic acetyltransferases SSATs and Hpa2 that acetylate polyamines14,34,39.

Polyamines have been associated with cell motility and biofilm formation in different bacteria. In V. cholerae, the import of polyamines, as well as extracellular polyamines hindered biofilm formation43. The disruption of putrescine biosynthesis also enhanced cohesiveness and performance of Shewanella oneidensis biofilms and putrescine was associated with matrix disassembly44. Putrescine was also shown to be essential for biofilm formation in Y. pestis45 but it was required for swarming motility of Proteus mirabilis46. More strikingly, in Dickeya zeae, putrescine was required for both cell motility and biofilm formation and the authors suggested its role as signaling molecule47. We have found that the expression of dpa increases in static A. baumannii cells compared to planktonic cells. Consistently, the deletion of dpa shows decreased biofilm formation and increased motility. This could indicate that lower 1,3-DAP concentrations are required to trigger the switch to biofilm formation. We hypothesize two different scenarios: either 1,3-DAP is required for cell motility and its acetylation shuts down the dedicated regulon, or the product of Dpa, acetyl-diaminopropane is an activator involved in biofilm formation.

While it has been shown that 1,3-DAP is required for cell motility and virulence4, future research will be needed to assess the functionality of acetyl-diaminopropane as a potential signaling molecule. Our work shows that acetylation of 1,3-DAP plays an important role both in biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and in adherence to eukaryotic epithelial cells. We thus anticipate that Dpa could be a suitable target for the development of novel highly specific antibacterials to combat the spread of multi-drug resistant A. baumannii.

Methods

Media and growth conditions

E. coli and A. baumannii were grown on solid and in liquid LB (Lennox L broth) medium; for twitching and pellicle formation experiments TSB (Tryptic Soy Broth, Oxoid) was used. Antibiotic concentrations were as follows−ampicillin 100 μg/ml; gentamicin 10 μg /ml. The E. coli DJ624∆ara strain was used for cloning and protein expression. A. baumannii strain used in this study was isolated from clinical surgery patient and was designated to ST231 according to Oxford MLST scheme and international clone I (ICI).

Cloning and mutagenesis

The markerless deletion of the dpa gene (GenBank ID: OQ718427) was performed as described previously48, using primers presented in Supplementary Table S2. The successful deletion was confirmed by PCR.

For complementation experiments, a plasmid containing an IPTG-inducible dpa gene was constructed. The backbone of the previously described plasmid pUC_gm_AcORI_Ptac_gfp49 was used, and the gfp gene was replaced with dpa (primers used to amplify dpa presented in Supplementary Table S2). The correct insertion of dpa into the plasmid was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Baseclear).

For protein expression dpa and hpa2 genes were PCR amplified from clinical A. baumannii isolate described previously16, speG from E. coli K-12 MG1655, and aac(6’)-Iy from S. enterica LT2 with Q5 polymerase (NEB) using primers presented in Supplementary Table S2 and cloned to pKK223.3 plasmid through EcoRI and PstI restriction sites. Amino acid sequences of all his-tagged enzymes used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S3. Mutation in the active site of Dpa was introduced by PCR amplification of the pKK223.3-hisDpa vector with primers carrying the mutation (Supplementary Table S2). Clones were verified by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz).

Motility, biofilm and pellicle formation and adhesion to eukaryotic cells tests

The phenotypic motility and pellicle formation tests of A. baumannii were performed following the protocol described earlier17, with one deviation that isopropanol was not used for collecting pellicles. Adhesion to mouse lung epithelial LL/2 (LLC1) cells (ATCC, CRL-1642) was also performed as described previously17. After infection, epithelial cells were carefully washed with DPBS three times to remove non-adherent bacteria and lysed with ddH2O by intense pipetting.

Expression quantification by RT-qPCR

A. baumannii cells were collected by centrifugation at 6500 g for 10 min at 20 °C, except for pellicles, which were removed from the 12-well plates using a sterile pipet tip and used for RNA isolation immediately. RNA was extracted using GeneJET RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), DNA removed with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and cDNA synthesized using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. qPCR was performed by CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using primers presented in Supplementary Table S2 for detection of dpa transcripts, and for detection of tuf (EF-Tu) transcripts; rpoB was used as a house-keeping gene. For qPCR reaction (25 μl), Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, 1.5 μM Syto9 (Invitrogen), and primer concentrations were selected according to the amplification efficiency (100% efficiency at selected concentrations). The changes in gene expression were calculated as ΔΔCt, using rpoB as housekeeping gene. At least three biological replicas were performed.

Protein expression and purification

pKK223.3-his-Dpa, pKK223.3-his-DpaY128F, pKK223.3-his-Hpa2Ab, pKK223.3-his-SpeGEc, pKK223.2-his-Aac(6’)Se vectors were freshly transformed into E. coli DJ624∆ara strain. Overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold, grown until OD = 0.6 and protein synthesis was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 hours at 16 °C. Cells were then collected by centrifugation at 4000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, resuspended in buffer A (50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP) and disrupted with a high-pressure homogenizer (Microfluidics). Protein extract was cleared by centrifugation at 20000 g for 30 min, filtered through a 0.45 µM filter and proteins were loaded onto HisTrapHP column (Cytiva). The column was washed with 15 CV of buffer A and proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of buffer B (50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 1 M imidazole). Fractions containing the pure protein were pooled and concentrated using Amicon spin filter concentrator (Millipore). Protein was further purified by size exclusion gel filtration chromatography on Superdex200 10/30 column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with gel filtration buffer 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.5, 250 mM NaCl. Protein size and purity were verified by SDS-PAGE.

Analytic size exclusions chromatography

Analytic SEC runs were performed using Superdex75 increase 1030 column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl) and injecting 500 μL of 20 μM of protein. When indicated, proteins were pre-incubated with 5-fold molar excess of acCoA and/or 1,3-DAP. All the proteins used for gel filtration analyses were migrated on 15% SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie.

Protein crystallization

Purified his-Dpa protein was concentrated to 10 mg/ml using a spin filter concentrator (Amicon) and screened for crystallization with commercial screens Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 (Hampton Research), JCSG-plus, PACT premier, PEGRx HT (Molecular Dimensions) in the presence of 0.1 mM acetyl-CoA. Sitting drops of 100 nl protein solution topped with 100 nl precipitant solution were equilibrated against 80 µl precipitant solution. Drops were set up using Mosquito robotic system (TTP Labtech) in Swisci 96-well 2-drop plates and incubated at 20 °C. Crystals grown in 0.2 M Sodium acetate trihydrate, 0.1 M TRIS hydrochloride pH 8.5, 30% w/v Polyethylene glycol 4,000 were of best diffraction quality. Crystals were quick soaked in mother liquor solution supplied with a final concentration of 2 M sodium bromide and 20% PEG400 for cryo-preservation and vitrified in liquid nitrogen.

The his-Dpa Y135F protein was purified in identical conditions to the wild-type. Protein crystals were set up in 0.2 M Sodium acetate trihydrate, 0.1 M TRIS hydrochloride pH 8.5, 30% w/v Polyethylene glycol 4,000, 0.1 mM acetyl-CoA. Crystals were immersed in a cryogenic solution (mother liquor with 20% PEG400) supplemented with 2 M 1,3-DAP (Sigma) for a 30–60 s before vitrification in liquid nitrogen.

X-ray data collection and processing

Diffraction data were collected on the PROXIMA-1 (PX1) and PROXIMA-2A (PX2A) beamlines at the SOLEIL synchrotron, Gif-sur-Yvette, Paris, France. Data were indexed, integrated with XDS50, scaled with XSCALE50 or AIMLESS51, quality and twinning were assessed with phenix.xtriage52 and POINTLESS51. Data from his-Dpa crystals were collected at the Br K edge for experimental phasing. Cell-content analysis was performed with MATTHEWS_COEF53. The heavy-atom substructure was found with ShelxD as implemented in the HKL2MAP suite54,55.

The initial model of Dpa was built using ShelxE and subsequently used in ArpWarp56, which generated 90% of the model. After several iterations of manual building with Coot57 and maximum likelihood refinement as implemented in Buster/TNT58, the model was extended to cover all the residues (R/Rfree of 18.2/20.7 %). The structure of his-DpaY128F in complex with 1,3-DAP was solved by molecular replacement using his-Dpa as the search model. After molecular replacement with as implemented in the the Phenix package52, the model of the complex was completed by manual building with Coot57 and maximum likelihood refinement as implemented in Buster/TNT58 (R/Rfree of 19.6/23.2 %). All the details of the data processing and refinement are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Enzymatic reactions using [14 C]Ac-CoA

For protein, RNA and small molecule extract acetylation, bacterial cells were grown to the mid-exponential phase (OD = 1). Cells were then disrupted as described above in the protein purification section. Small molecules were separated from proteins by retaining the proteins in a spin filter concentrator (Amicon) with 3 kDa cut-off. The filtrate was further concentrated using a speed vacuum concentrator. RNA was extracted with standard hot-phenol and chloroform extraction procedure, then precipitated with isopropanol and dissolved in water.

All acetylation reactions were supplied with 200 μM radiolabeled [14 C]Ac-CoA (60 mCi/mmol) and 1 μM his-Dpa when indicated. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. For kinetics experiments reactions were incubated at 22 °C in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 9 and stopped at different times by adding 50% cold TCA.

Proteins were resolved on 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel (BioRad) and nucleic acids were resolved on 10% native acrylamide (19:1) TBE (Tris-borate EDTA) gel that were stained with coomassie blue or methylene blue respectively. Acetylation reactions of small molecules and commercial polyamines (Sigma) were resolved on cellulose TLC plates in the isopropanol/HCl/water (68/18/14) mobile phase. Gels and plates were dried and exposed to multipurpose phosphor storage screen (Amersham) overnight and scanned using the Storm 860 PhosphoImager system (Molecular Dynamics). For kinetics, the ac-1,3-DAP was quantified from the band intensity measured with the ImageJ program.

Enzymatic reactions using DTNB

Reactions were assembled in 96-well clear polystyrene flat-bottom plates. 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 mM acCoA, 5 mM substrates, 2 μM of acetyltransferase enzymes in reaction volumes of 50 μL. Reactions were proceeded for 30 min at 30 °C, stopped by adding 50 μL of 6 M guanidine HCl and revealed by adding 200 μL of Ellman’s Reagent (0.2 mM DTNB (5,5-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid, Sigma), 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). After 10 min of additional incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 415 nm in Spectramax i3 microplate reader using SoftMax Pro 6.3 software (Molecular Devices). Since different substrates give various level of background, reactions without enzyme were performed for each substrate and their values were used as a blank. For Dpa enzyme kinetics, 50 μL of Ellman’s Reagent without EDTA was layered over 50 μL of reactions containing 2 μM of enzyme, its mutated derivative, or enzyme pre-treated with EDTA. Reactions contained 0.5 mM acCoA, 10 mM 1,3-DAP and 10 mM EDTA when indicated. Once assembled, kinetics reactions were immediately transferred to microplate reader and absorbance was measured every 2 minutes for 1 hour. In order to convert the DTNB signal to the quantity of reaction products, standard curves were generated by measuring the signal of dilutions of CoA in the range of 0.01 to 1 mM. All assays were performed in triplicates and their average with standard deviations were plotted.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Research Grant 2022 from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) to DJ; the Fonds National de Recherche Scientifique (FNRS-MIS F4526.23) to DJ. The FRFS-WELBIO CR-2017S-03, FNRS CDR J.0068.19 and CDR J.0066.21, FNRS-EQP UN.025.19 and UN.031.N21F; and FNRS-PDR T.0066.18 and PDR T.0090.22 to AGP); ERC (CoG DiStRes, n° 864311 to AGP) and Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance, (JPIAMR) JPI-EC-AMR-R.8004.18 to AGP; the Program Actions de Recherche Concerté 2016-2021, Fonds d’Encouragement à la Recherche of ULB (AGP); Fonds Jean Brachet and the Fondation Van Buuren (AGP); The authors acknowledge the use of beamtimes PROXIMA 1 and 2 A at the Soleil synchrotron (Gif-sur-Yvette, France). The authors thank Mykolas Bendorius, Beatričė Radavičiūtė and Paulė Želvytė for their involvement in the early steps of the project and Laurence Van Melderen for giving the possibility to develop part of the project in her lab.

Source data

Author contributions

D.J., A.G-P., J.A., E.S. designed the research. D.J., J.A., A.Č., G.Š., J.M., J.S., C.M. performed research. J.A., E.S., C.M., A.G.P., D.J. provided tools. J.A., A.G.P., D.J. analyzed the data. D.J and A.G.P. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the authors. All authors approved the final revision of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Carston Wagner, Gottfried Wilharm and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The final atomic model and coordinates of Dpa and of the Dpa in complex with the 1,3-DAP generated in this study have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession codes 8A9O and 8A9N respectively. Previously reported structures used in this study are available in the PDB under accession codes: 4R9M, 3BJ7, 1S5K, 1QSO, 1TIQ, 4R87, 1QSM, 3BJ8, 5JPH, 4JLY, 2B5G. Uncropped gels, Western-blots and data generated in this study are provided in Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abel Garcia-Pino, Email: abel.garcia.pino@ulb.be.

Dukas Jurėnas, Email: dukas.jurenas@ulb.be.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-39316-5.

References

- 1.Antunes LCS, Visca P, Towner KJ. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog. Dis. 2014;71:292–301. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding CM, Hennon SW, Feldman MF. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:91–102. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamana K, Matsuzaki S. Diaminopropane occurs ubiquitously in Acinetobacter as the major polyamine. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1992;38:191–194. doi: 10.2323/jgam.38.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skiebe E, et al. Surface-associated motility, a common trait of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii, depends on 1,3-diaminopropane. Int J. Med. Microbiol. 2012;302:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaschke U, Skiebe E, Wilharm G. Novel Genes Required for Surface-Associated Motility in Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Microbiol. 2021;78:1509–1528. doi: 10.1007/s00284-021-02407-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wortham BW, Patel CN, Oliveira MA. Polyamines in bacteria: pleiotropic effects yet specific mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med Biol. 2007;603:106–115. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72124-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah P, Swiatlo E. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:4–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Modulation of cellular function by polyamines. Int J. Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Martino ML, et al. Polyamines: emerging players in bacteria-host interactions. Int J. Med Microbiol. 2013;303:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campilongo R, et al. Molecular and functional profiling of the polyamine content in enteroinvasive E. coli: looking into the gap between commensal E. coli and harmful Shigella. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuchi J, Kashiwagi K, Yamagishi M, Ishihama A, Igarashi K. Decrease in cell viability due to the accumulation of spermidine in spermidine acetyltransferase-deficient mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18831–18835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbagallo M, et al. A new piece of the Shigella Pathogenicity puzzle: spermidine accumulation by silencing of the speG gene [corrected] PLoS One. 2011;6:e27226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang S-B, et al. speG Is Required for Intracellular Replication of Salmonella in Various Human Cells and Affects Its Polyamine Metabolism and Global Transcriptomes. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2245. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montemayor EJ, Hoffman DW. The crystal structure of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase in complex with spermine provides insights into substrate binding and catalysis. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9145–9153. doi: 10.1021/bi8009357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fogel-Petrovic M, Shappell NW, Bergeron RJ, Porter CW. Polyamine and polyamine analog regulation of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase in MALME-3M human melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:19118–19125. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46742-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurenaite M, Markuckas A, Suziedeliene E. Identification and characterization of type II toxin-antitoxin systems in the opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:3165–3172. doi: 10.1128/JB.00237-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skerniškytė J, et al. Surface-Related Features and Virulence Among Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates Belonging to International Clones I and II. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3116. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verstraeten N, et al. Living on a surface: swarming and biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burckhardt RM, Escalante-Semerena JC. Small-Molecule Acetylation by GCN5-Related N-Acetyltransferases in Bacteria. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 2020;84:e00090–19. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00090-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salah Ud-Din AIM, Tikhomirova A, Roujeinikova A. Structure and Functional Diversity of GCN5-Related N-Acetyltransferases (GNAT) Int J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:E1018. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seiler N, al-Therib MJ. Acetyl-CoA: 1,4-diaminobutane N-acetyltransferase. Occurrence in vertebrate organs and subcellular localization. Biochim Biophys. Acta. 1974;354:206–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(74)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallwitz D, Sekeris CE. The acetylation of histones of rat liver nuclei in vitro by acetyl-CoA. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 1969;350:150–154. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1969.350.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomar JS, Peddinti RK. A. baumannii histone acetyl transferase Hpa2: optimization of homology modeling, analysis of protein-protein interaction and virtual screening. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017;35:1115–1126. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2016.1172025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomar JS, Peddinti RK, Hosur RV. Aminoglycoside antibiotic resistance conferred by Hpa2 of MDR Acinetobacter baumannii: an unusual adaptation of a common histone acetyltransferase. Biochem J. 2019;476:795–808. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomar JS, Hosur RV. Polyamine acetylation and substrate-induced oligomeric states in histone acetyltransferase of multiple drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Biochimie. 2020;168:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnet S, Courvalin P, Lambert T. Activation of the cryptic aac(6’)-Iy aminoglycoside resistance gene of Salmonella by a chromosomal deletion generating a transcriptional fusion. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:6650–6655. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.21.6650-6655.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vetting MW, Magnet S, Nieves E, Roderick SL, Blanchard JS. A bacterial acetyltransferase capable of regioselective N-acetylation of antibiotics and histones. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majorek KA, et al. Insight into the 3D structure and substrate specificity of previously uncharacterized GNAT superfamily acetyltransferases from pathogenic bacteria. Biochim Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2017;1865:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyda F, Klein DC, Hickman AB. GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases: a structural overview. Annu Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:81–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vetting MW, et al. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filippova EV, et al. A novel polyamine allosteric site of SpeG from Vibrio cholerae is revealed by its dodecameric structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:1316–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsimbalyuk S, Shornikov A, Thi Bich Le V, Kuhn ML, Forwood JK. SpeG polyamine acetyltransferase enzyme from Bacillus thuringiensis forms a dodecameric structure and exhibits high catalytic efficiency. J. Struct. Biol. 2020;210:107506. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugiyama S, et al. Molecular mechanism underlying promiscuous polyamine recognition by spermidine acetyltransferase. Int J. Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;76:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bewley MC, et al. Structures of wild-type and mutant human spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase, a potential therapeutic drug target. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2006;103:2063–2068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511008103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hegde SS, Chandler J, Vetting MW, Yu M, Blanchard JS. Mechanistic and structural analysis of human spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7187–7195. doi: 10.1021/bi700256z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filippova EV, et al. Substrate-Induced Allosteric Change in the Quaternary Structure of the Spermidine N-Acetyltransferase SpeG. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:3538–3553. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dempsey DR, et al. Structural and Mechanistic Analysis of Drosophila melanogaster Agmatine N-Acetyltransferase, an Enzyme that Catalyzes the Formation of N-Acetylagmatine. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13432. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13669-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Filippova EV, Weigand S, Kiryukhina O, Wolfe AJ, Anderson WF. Analysis of crystalline and solution states of ligand-free spermidine N-acetyltransferase (SpeG) from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr D. Struct. Biol. 2019;75:545–553. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319006545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angus-Hill ML, Dutnall RN, Tafrov ST, Sternglanz R, Ramakrishnan V. Crystal structure of the histone acetyltransferase Hpa2: A tetrameric member of the Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferase superfamily. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:1311–1325. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eze EC, Chenia HY, El Zowalaty ME. Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms: effects of physicochemical factors, virulence, antibiotic resistance determinants, gene regulation, and future antimicrobial treatments. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018;11:2277–2299. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S169894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto S, Tsuzaki Y, Tougou K, Shinoda S. Purification and characterization of L-2,4-diaminobutyrate decarboxylase from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1992;138:1461–1465. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-7-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikai H, Yamamoto S. Identification and analysis of a gene encoding L-2,4-diaminobutyrate:2-ketoglutarate 4-aminotransferase involved in the 1,3-diaminopropane production pathway in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:5118–5125. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5118-5125.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGinnis MW, et al. Spermidine regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation via transport and signaling pathways. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;299:166–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding Y, Peng N, Du Y, Ji L, Cao B. Disruption of putrescine biosynthesis in Shewanella oneidensis enhances biofilm cohesiveness and performance in Cr(VI) immobilization. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:1498–1506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03461-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel CN, et al. Polyamines are essential for the formation of plague biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2355–2363. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2355-2363.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sturgill G, Rather PN. Evidence that putrescine acts as an extracellular signal required for swarming in Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:437–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Z, et al. Putrescine Is an Intraspecies and Interkingdom Cell-Cell Communication Signal Modulating the Virulence of Dickeya zeae. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1950. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skerniškytė J, et al. Blp1 protein shows virulence-associated features and elicits protective immunity to Acinetobacter baumannii infection. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:259. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1615-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krasauskas R, Skerniškytė J, Armalytė J, Sužiedėlienė E. The role of Acinetobacter baumannii response regulator BfmR in pellicle formation and competitiveness via contact-dependent inhibition system. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:241. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1621-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabsch, W. X. D. S. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr.66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pape T, Schneider TR. HKL2MAP: a graphical user interface for macromolecular phasing with SHELX programs. J. Appl Cryst. 2004;37:843–844. doi: 10.1107/S0021889804018047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheldrick GM. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:479–485. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909038360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smart OS, et al. Exploiting structure similarity in refinement: automated NCS and target-structure restraints in BUSTER. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:368–380. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911056058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The final atomic model and coordinates of Dpa and of the Dpa in complex with the 1,3-DAP generated in this study have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession codes 8A9O and 8A9N respectively. Previously reported structures used in this study are available in the PDB under accession codes: 4R9M, 3BJ7, 1S5K, 1QSO, 1TIQ, 4R87, 1QSM, 3BJ8, 5JPH, 4JLY, 2B5G. Uncropped gels, Western-blots and data generated in this study are provided in Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.