Abstract

This study was conducted during the period of August 2021 to April 2022 and divided into two parts. The first part involved the isolation and characterization of Salmonella from 200 diseased broiler chickens collected from farms in Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt, with the detection of its antimicrobial susceptibility. The second experimental part involved in ovo inoculation of probiotics and florfenicol to evaluate their effects on hatchability, embryonic viability, growth performance traits and the control of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Enteritidis infections post hatching. The point prevalence of Salmonella in the internal organs of diseased chickens was 13% (26/200), including 6 serotypes: S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Santiago, S. Colindale, S. Takoradi and S. Daula. Multidrug resistance was found in 92% (24/26) of the isolated strains with a multiantibiotic resistance index of 0.33–0.88 and 24 antibiotic resistance patterns. The in ovo inoculation of probiotic with florfenicol showed significant improvement in the growth performance parameters compared with other groups and had the ability to prevent colonization of multidrug resistant S. Enteritidis in the majority of the experimental chicks, and the remaining chicks showed very low colonization, as detected by RT‒PCR. These findings suggested the application of in ovo inoculation techniques with both probiotics and florfenicol as a promising tool to control multidrug-resistant S. Enteritidis in poultry farms.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Zoology

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is considered one of the most important foodborne pathogens1,2, producing a global economic impact on public health3. Annually, there are approximately 93 million cases of human gastroenteritis and up to 155,000 deaths due to Salmonella infections worldwide1. Poultry and poultry products are the main important sources of human Salmonella infections1,4, and most outbreaks are caused by chickens, as they are known to be carriers of Salmonella in their gut. According to European Union One Health Zoonoses Report during 2019, broiler was the source of 70.0% of all serotyped Salmonella isolates5. S. Enteritidis infecting poultry-producing fowl paratyphoid6 and associated with the occurrence of human salmonellosis during the last 20 years7. Salmonella is still a major problem facing the poultry industry, not only because of the risk arising from mortalities but also because of the economic losses and reduced efficiency that can occur as a result of bird infection8. Unfortunately, pathogens can infect chicks while they are still at the hatchery, throughout the process of hatching, sexing, receiving vaccinations, and being transported and even before they have had their first feed9. In current poultry production systems, the lack of contact between chicks and adult birds slows the colonization of the intestinal tract by beneficial microbes10. Initial microbial colonization is crucial to promote immune system growth and maturation as well as to prevent harmful bacteria from colonizing by competitive exclusion11. Particularly in newborn animals with rapid growth rates, gut health and function are crucial for supplying all essential nutrients for growth and maintenance12.

The elimination of drugs used as growth promoters in animal diets13 or in the treatment of different pathogens from the most important points must be considered to avoid the misuse of antibiotics, which facilitates the generation of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria infecting poultry farms14. The emergence of multidrug resistance in Salmonella isolates affecting the food chain has become a public health concern worldwide15. Therefore, many approaches should be implemented to control Salmonella and other intestinal bacteria infecting poultry, such as in ovo inoculation with probiotics16, which not only improves the intestinal epithelium, immune system and health condition of birds17 but also increases egg hatchability, reduces embryonic mortality and increases posthatch growth performance18. Probiotics are live cultures of microbes that have beneficial effects on host health. Its application in poultry diets improves the birds’ immune responses, performance, and feed conversion ratios19 and prevents enteric pathogens by the competitive exclusion mechanism17. The use of probiotics as feed additives improves the quality and taste of poultry products20. On the other hand, amphenicol drugs have an increased role as therapeutic agents against avian pathogens. They have bacteriostatic effects and a wide antibacterial spectrum. Most gram-positive and gram-negative organisms are susceptible21. Florfenicol belongs to the amphenicol pharmacological group and is approved in the European Union for use in cattle, sheep, pigs and chickens22.

There is little information available about the effects of injecting florfenicol injectable solution into chicken eggs. The injection of florfenicol in embryonated chicken eggs showed no toxicity and no gross abnormality in the tissues and external body of the embryos, and it can be used for the success of the eradication scheme23. Therefore, this study aims to isolate and characterize S. Enteritidis from diseased birds and for the first time investigate the synergistic influence of in ovo-inoculation of probiotic and florfenicol on embryonic viability, growth performance, and the control of multidrug-resistant S. Enteritidis in broiler chicks.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

A total of 200 diseased broiler chickens (age: 22 to 32 days) were collected randomly from 10 farms located in Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt. The collected chickens suffered from watery diarrhea, inappetence, poor growth, ruffled feathers and weakness. The birds were subjected to post-mortem examinations (PM), and samples from internal organs (liver, spleen, heart and cecum) were collected aseptically and then labelled and transported directly to the Reference Laboratory for Veterinary Quality control on Poultry production for further examinations.

This protocol was performed by following the animal ethics guidelines and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Mansoura University with code number [R/143]. Additionally, all methods are reported in accordance with International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals as issued by the Council for the International Organizations of Medical Sciences.

Salmonella isolation and identification

Salmonella was isolated according to24. Briefly, the internal organs from each bird were pooled together and considered one sample. One gram of each sample was added to 9 ml of nutrient broth (Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. After pre-enrichment, 1 ml of each broth culture was transferred to 9 ml of Selenite F broth (Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. A loop-full of culture from Selenite F broth was streaked into plates of XLD (Oxoid, UK). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h and checked for growth of typical colonies of Salmonella spp. Conventional biochemical methods including the urase test, triple sugar iron (TSI), lysine decarboxylase test, ornithin decarboxylase test, indole test, citrate utilization test and xylose, sucrose, rhamnose and arabinose fermentation tests were performed according to25. According to the Kauffman-White scheme26, the serological identification of Salmonella isolates for the detection of somatic and flagellar antigens was performed.

Antimicrobial sensitivity

Salmonella isolates were tested against 9 antibiotics commonly used in broiler farms in Egypt by the disc diffusion method27. Nine antibiotics belonging to 6 classes were selected. They included Sulfonamides such as sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (25 µg), Tetracyclines such as oxytetracycline (OT; 30 µg), doxycycline (DO; 30 µg), Aminoglycosides such as streptomycin (S; 10 µg), neomycin (N; 30 µg), penicillin ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM; 20 µg), and amoxicillin (AMX; 10 µg), Polypeptides such as colistin sulfate (CT; 25 µg) and Amphotericols such as florfenicol (FFC; 30 µg). The recorded inhibition zones were interpreted according to28.

In vivo inoculation of probiotic in SPF embryonated chicken egg and its role in the control of Salmonella posthatching

Experimental design: Specific pathogen-free (SPF) embryonated chicken eggs (n = 75) were obtained from a Ross broiler breeder flock (age = 38 weeks) that was free from Salmonella and not vaccinated. The collected eggs were individually weighed and divided into 5 groups (15 eggs for each) with similar average egg weights for each group. The eggs were then incubated under standard conditions (54% relative humidity and 37.5 °C)16.

The embryo viability was checked throughout the incubation period; all eggs were candled to discard any unfertile eggs and dead embryos. After the egg candling process on the 18th day of incubation, the eggs were transported outside the incubator, disinfected with 70% alcohol and inoculated as follows: groups (1) and (2) were control groups inoculated with phosphate buffered saline, and group (3) was inoculated with a commercial probiotic bacterial product (Wiser biotic, WISER CARE company, Egypt, batch no: 100210117). Each egg in group (3) was inoculated with 0.3 ml of sterile saline solution containing 1 gm of the probiotic product containing Bacillus subtilis 5.25 × 1011 CFU and Bacillus licheniforms 5.25 × 1011 CFU for each kg)18 in the air sac using a pipette attached to a 23-ga needle, and group (4) was injected with florfenicol product (Floricol, PHARMA SWEDE company, Egypt Batch no: L201226) (each ml contained 100 mg florfenicol). A total of 0.5 ml saline solution containing 20 mg florfenicol for each kg egg weight)29. Group (5) was inoculated with both probiotic bacterial solution and florfenicol as mentioned above. After the inoculation process finished, all holes in the inoculated eggs were immediately sealed, and the eggs were returned again to the incubator. At day 21 (hatching day), the hatchability percentage was determined, and all non-hatched eggs were examined to explore the cause of embryo death.

The post hatch effects of probiotic, florfenicol and probiotic mixture with florfenicol in ovo inoculation of S. Enteritidis infection were carried out as follows: 50 hatched chicks were selected from the previous 5 egg groups (10 chicks from each group), and the groups kept their previous numbers. The experiment was conducted in the biosafety level 2 + animal facility (BSL2 +). Chicks housed in separate rooms in metal grid cages. Water and feed were provided ad libitum during the whole experiment period. The temperature was manually controlled and gradually reduced from 32 to 33 °C in the first week to 20–21 °C at the end of the experiment. Chickens were first maintained on a 24-h light cycle, and then the light program was progressively changed to 18 h of light and 6 h of darkness. The number of air exchanges was 12 per hour and humidity was maintained between 55 and 70%. Chickens not vaccinated. These chicks were challenged orally at the 2nd day of age with a multidrug-resistant S. Enteritidis strain (selected from the isolates of this study) at 106 CFU/ml, which was adjusted by a spectrophotometer (Automatic Elisa Plate Analyser, Robonik, India)16. Group (1) remained as nonchallenged control negative, and group (2) was marked as control positive.

The health status of the challenged chicks was checked twice daily, and any clinical signs, mortalities and post-mortem (PM) lesions were recorded until the end of the experiment on the 12th day of chick age (10th day post inoculation). At the end of the experimental period, growth performance parameters; feed intake (FI), feed conversion ratio (FCR), body weight (BW) and body weight gain (BWG), were observed. At the end of the experiment, all of the remaining chicks were killed by cervical dislocation, and the ceca were collected aseptically from each chick and processed for S. Enteritidis isolation, which was confirmed by using slide agglutination tests with serotype-specific antisera24.

Real-time PCR (RT‒PCR) for quantitative detection of Salmonella in cecal contents of chicks under experiment

The colonization of S. Enteritidis (CFU per gram of ceca) was evaluated using quantitative RT‒PCR; one gram of cecal contents was homogenized, and DNA was extracted from the prepared cecal samples using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany, GmbH). Briefly, 200 µl of the processed cecal content suspension was incubated at 56 °C for 10 min with 10 µl of proteinase K and 200 µl of lysis buffer. Then, 200 µl of ethanol (100%) was added to the lysate, and the samples were washed and centrifuged according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA was eluted using 100 µl of elution buffer. The oligonucleotide primers and probes used for the Salmonella invA gene were supplied by Metabion (Germany) (Supplementary Table 1)29. DNA amplifications were performed in a final volume of 25 µl containing 3 µl of DNA template, 12.5 µl of 2 × QuantiTect Probe RT‒PCR Master Mix, 8.875 µl of PCR grade water, 0.25 µl of each primer (50 pmol conc.) and 0.125 µl of each probe (30 pmol conc.). Primary denaturation was performed for 15 min at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 15 s at 94 °C, annealing for 30 s at 49 °C and extension for 10 s at 72 °C using a Strata gene MX3005P real-time PCR machine, which had the ability to show the standard quantity with 3 decimals. Salmonella concentration within the examined samples was detected with CFU/gm. A known CFU/gm standard was serially diluted (tenfold), and then DNA was extracted from the last 5 dilutions separately and tested by RT‒PCR as mentioned above for the examined cecal content samples.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20. The One-Way ANOVA test was used to calculate the P value and determine the significant differences between experimental groups. A P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This protocol was performed by following the animal ethics guidelines and approved by Medical Research Ethics Committee of Mansoura University with code number [R/145]. Also, all methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Consent to participate not applicable.

Results

Point prevalence and serotypes of Salmonella

Out of 200 samples, Salmonella was detected in 26 (13%) samples (Table 1), including 6 different serotypes (S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Santiago, S. Colindale, S. Takoradi and S. Daula). The predominant isolates were S. Enteritidis (l0) and S. Typhimurium (8), followed by S. Santiago (3), S. Colindale (2), S. Takoradi (2) and S. Daula (1).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial resistance of isolated Salmonella serovars.

| Serovars (no.) | DO | OT | S | N | SXT | FFC | CT | AMX | SAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. Enteritidis (10) | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 8 |

| S. Typhimurium (8) | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| S. Santiago (3) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| S. Colindale (2) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| S. Takoradi (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| S. Daula (1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total (26) | 12 | 18 | 15 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 19 |

| Resistant (%) | 46.15% | 69.23% | 57.69% | 30.77% | 46.15% | 46.15% | 57.69% | 69.23% | 73.08% |

| Susceptible (%) | 53.85% | 30.77% | 42.31% | 69.23% | 53.85% | 53.85% | 42.31% | 30.77% | 26.92% |

AMX amoxicillin, CT colistin sulphate, DO doxycycline, FFC florfenicol, N neomycin, S streptomycin, SAM ampicillin/sulbactam, SXT sulfamethoxazole- trimethoprim, OT oxytetracycline.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Disc diffusion tests revealed that high resistance percentages were recorded with SAM (73.08%%), followed by AMX, OT (69.23%, for each), S and CT (57.69%, for each). Meanwhile, low resistance was recorded with DO, SXT, FFC (46.15%, for each) and N (30.77%). Most of the isolated Salmonellae showed multidrug resistance (Table 1). In addition, multidrug resistance (MDR) to three or more antimicrobial classes was detected in 24 out of 26 (92%) isolates with a high multidrug antibiotic resistance index (MARI) of 0.33–0.88 (Table 2). Salmonella serovars in this study showed 24 different MDR patterns (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistant pattern profiles of isolated Salmonella strains.

| Antibiotic pattern profiles | Antibiotics | No. of resistant isolates | Salmonella Serotypes | No. of resistance antibiotics | MARI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AMX, SAM, OT, SXT, FFC, CT, DO | 1 | S. Entritidis | 7 | 0.77 |

| 2 | AMX, SAM, N, OT, SXT, FFC, CT, DO | 1 | S. Entritidis | 8 | 0.88 |

| 3 | AMX, SAM, S, OT, FFC, CT, DO | 1 | S. Entritidis | 7 | 0.77 |

| 4 | AMX, SAM, OT, FFC, CT, DO | 1 | S. Entritidis | 6 | 0.66 |

| 5 | AMX, SAM, N, OT, SXT, FFC | 1 | S. Entritidis | 6 | 0.66 |

| 6 | AMX, SAM, N, S, OT, SXT | 1 | S. Entritidis | 6 | 0.66 |

| 7 | AMX, SAM, N, S, FFC | 1 | S. Entritidis | 5 | 0.55 |

| 8 | SAM, N, S | 1 | S. Entritidis | 3 | 0.33 |

| 9 | AMX, SAM, N, S, OT, SXT, CT | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 7 | 0.77 |

| 10 | AMX, SAM, S, OT, DO | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 5 | 0.55 |

| 11 | AMX, SAM, N, S, OT, OX, SXT | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 7 | 0.77 |

| 12 | AMX, OT, SXT, CT, DO | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 5 | 0.55 |

| 13 | AMX, SAM, OT, CT | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 4 | 0.44 |

| 14 | SAM, SXT, CT, DO | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 4 | 0.44 |

| 15 | S, OT, SXT | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 3 | 0.33 |

| 16 | S, OT, CT | 1 | S. Typhimurium | 3 | 0.33 |

| 17 | AMX, SAM, OT, FFC, CT | 1 | S. Daula | 5 | 0.55 |

| 18 | S, OT, SXT, FFC, CT, DO | 1 | S. Santigo | 6 | 0.66 |

| 19 | AMX, SAM, S, OT, FFC, CT | 1 | S. Santigo | 6 | 0.66 |

| 20 | AMX, S, CT, DO | 1 | S. Santigo | 4 | 0.44 |

| 21 | AMX, SAM, FFC, CT, DO | 1 | S. Takoradi | 5 | 0.55 |

| 22 | AMX, SAM, N, S, OT | 1 | S. Takoradi | 5 | 0.55 |

| 23 | AMX, SAM, S, FFC, SXT, CT, DO | 1 | S. Colindale | 7 | 0.77 |

| 24 | SAM, S, OT, FFC, SXT | 1 | S. Colindale | 5 | 0.55 |

AMX amoxicillin, CT colistin sulphate, DO doxycycline, FFC florfenicol, N neomycin, S streptomycin, SAM ampicillin/sulbactam, SXT sulfamethoxazole- trimethoprim, OT oxytetracycline.

The effect of in ovo inoculation of probiotic and florfenicol on egg hatchability and embryonic mortalities

On the day of hatching, the egg hatchability was estimated (number of hatched chicks/number of incubated eggs in each group), and the results (Table 3) revealed that the hatchability in groups 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 was 86.7%, 93.3%, 100%, 100% and 100%, respectively. Embryonic deaths were recorded only in the non-inoculated (control) groups (1 and 2), and the inoculated groups (3, 4 and 5) showed no embryonic mortalities. The examination of dead embryos showed that the eggshells were sticky.

Table 3.

The effect of in ovo inoculation of probiotic and florfenicol on egg hatchability and embryonic mortalities.

| Group No | Treatment of groups | Embryonic mortalities | Egg hatchability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | No treatment | 2/15 (13.3%) | 13/15 (86.7%) |

| Group 2 | 1/15 (6.7%) | 14/15 (93.3% | |

| Group 3 | Probiotic | 0/15 (0%) | 15/15 (100) |

| Group 4 | Florfenicol | 0/15 (0%) | 15/ 15 (100) |

| Group 5 | Probiotic and florfenicol | 0/15 (0%) | 15/15 (100) |

The effect of in ovo inoculation of probiotic and florfenicol on the control of S. Enteritidis infection and growth performance parameters in chicks under experiment post hatching

Post hatching, the chicks were housed separately, and the groups kept their previous numbers. Ten chicks post hatching from each group (2, 3, 4 and 5) were challenged orally at the 2nd day of age with S. Enteritidis (selected from the isolates of this study). Group 1 remained as a nonchallenged negative control. The health status of the challenged chicks was observed daily until the end of the experiment on the 12th day of age (10th dpc). Group 1 (nonchallenged) showed no clinical signs. Chicks in the positive control (group, 2) showed signs of ruffled feathers, loss of appetite, poor growth, closed eyes, diarrhea and pasted vent, which appeared at the 3rd day post inoculation. Group 4 showed signs of weakness, loss of appetite and diarrhea, which appeared on the 5th day post inoculation and lasted until the end of the experiment. Group 3 showed weakness and slight diarrhea, which started on the 6th day post inoculation. Few chicks in group (5) showed only slight diarrhea on the 7th day post inoculation, which lasted 2 days after that and then began to disappear. A total of 30% morality was recorded only in the positive control group. The PM examinations of the positive control revealed congestion of the internal organs, enteritis, enlarged liver with hemorrhages, unabsorbed yolk sac and pasted vent. Chicks in groups (3), (4) and 3 chicks in group (5) showed enteritis. No PM lesions were recorded in group (1).

Growth performance parameters (FI, BW, BWG, and FCR) were recorded at the end of the experiment on the 12th day post inoculation (Table 4). The mean values of BW and BWG in group 5 were significantly higher (p < 0.0001) than those in the other experimental groups. Meanwhile, the FI and FCR mean values were significantly lower in group 5 (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.035, respectively) than in the other groups.

Table 4.

Means of body weight, body weight gain, Feed conversion ratio and feed intake of the chicks under experiment.

| Groups No | Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (BW) (g) | Body weight gain (BWG) (g) | Feed intake (FI) (g) | Feed conversion ratio (FCR) | |

| Group 1 | 373.9 ± 0.99387 | 333.6 ± 0.991071 | 382.3 ± 0.667499 | 1.146 ± 0.005049 |

| Group 2 | 179 ± 2.542964 | 138.8571 ± 2.610419 | 204.7143 ± 3.228592 | 1.147 ± 0.25385 |

| Group 3 | 378.8 ± 0.38873 | 338.4 ± 0.426875 | 377.5 ± 0.372678 | 1.116 ± 0.000771 |

| Group 4 | 372.5 ± 0.792324 | 332.2 ± 0.81377 | 381.1 ± 0.924362 | 1.118 ± 0.033006 |

| Group 5 | 383.4 ± 0.452155 | 343.1 ± 0.433333 | 253.9 ± 0.498888 | 0.739 ± 0.0566 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.035 |

*Mean values expressed as mean ± SEM (mean ± standard error).

Quantitative detection of Salmonella in cecal contents of chicks under experiment by using RT‒PCR

Cecal samples of the chicks in all groups were subjected to S. Enteritidis detection and confirmation with serotype-specific antisera. The results showed its detection in all chicks in the positive control group (2) and in all chicks of group 4, while it was detected in 9 chicks from group 3 and 3 chicks only from group 5. Group 1 (negative control) was negative for S. Enteritidis isolation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Colonization of S. Enteritidis (CFU/ gm) in the cecal samples of the experimental chicks.

| Code of samples | Group no | Results | Cut-off cycle threshold (CT) | Concentration of S. Enteritidis (CFU/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 (Negative Control) | − | No CT | − |

| 2 | 2 (Positive control) | + | 14.25 | 2.307 × 106 |

| 3 | + | 14.41 | 2.065 × 106 | |

| 4 | + | 15.39 | 1.048 × 106 | |

| 5 | 3 (treated with probiotic only) | + | 28.04 | 1.660 × 102 |

| 6 | + | 27.50 | 2.412 × 102 | |

| 7 | + | 26.00 | 6.809 × 102 | |

| 8 | + | 28.31 | 1.378 × 102 | |

| 9 | + | 26.14 | 6.180 × 102 | |

| 10 | − | No CT | − | |

| 11 | + | 26.35 | 5.345 × 102 | |

| 12 | + | 27.44 | 2.515 × 102 | |

| 13 | + | 26.22 | 5.848 × 102 | |

| 14 | + | 29.16 | 7.652 × 101 | |

| 15 | 4 (treated with florfenicol only) | + | 22.34 | 8.562 × 103 |

| 16 | + | 17.82 | 1.952 × 105 | |

| 17 | + | 21.76 | 1.279 × 104 | |

| 18 | + | 20.69 | 2.681 × 104 | |

| 19 | + | 18.92 | 9.121 × 104 | |

| 20 | + | 20.30 | 3.511 × 104 | |

| 21 | + | 20.89 | 2.335 × 104 | |

| 22 | + | 21.52 | 1.510 × 104 | |

| 23 | + | 21.12 | 1.991 × 104 | |

| 24 | + | 21.46 | 1.956 × 104 | |

| 25 | 5 (treated with probiotics and florfenicols) | − | No CT | − |

| 26 | − | No CT | − | |

| 27 | + | 31.72 | 1.302 × 101 | |

| 28 | − | No CT | − | |

| 29 | − | No CT | − | |

| 30 | + | 31.42 | 1.603 × 101 | |

| 31 | + | 30.81 | 2.444 × 101 | |

| 32 | − | No CT | − | |

| 33 | − | No CT | − | |

| 34 | − | No CT | − |

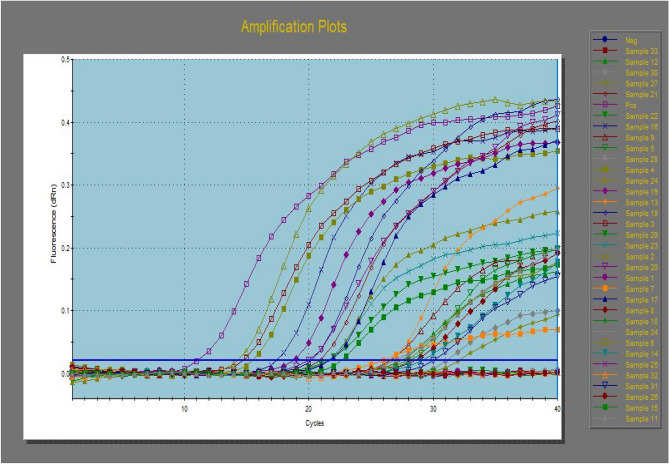

The colonization of S. Enteritidis (CFU per gram of ceca) was evaluated using quantitative RT‒PCR. The results in Table 5 and Fig. 1 revealed that all chicks in group 4 showed colonization ranging from 8.562 × 103 to 1.952 × 105 CFU/gm. In group 3, the colonization ranged from 7.652 × 101 to 6.809 × 102 CFU/gm in 9 chicks, which was lower in comparison with groups (2) and (4). Group (5) showed lower colonization in only 3 chicks, and the other chicks showed no colonization. Although egg inoculation with the probiotic in group 3 showed slight improvement in the growth performance of the experimental chicks, it could not prevent clinical signs or S. Enteritidis colonization in the cecum. Meanwhile, the experimental chicks in group 5 were inoculated with probiotic and florfenicol showed good results; the growth performance parameters (FI, BW, BWG, and FCR) were improved when compared with other groups. The in ovo inoculation of both probiotic and florfenicol prevented posthatch Salmonella colonization in the cecum of 7 out of 10 chicks, and the remaining chicks showed a very lower colonization of Salmonella. Individual inoculation with probiotics and florfenicol did not prevent clinical signs or Salmonella colonization in the cecum.

Figure 1.

The amplification plots of multidrug resistant S. Enteritidis colonization in the examined cecal samples using RT- PCR.

Discussion/Conclusion

In this study, Salmonella was isolated from diseased chickens in Dakahlia Governorate with a prevalence of 13%, and this percentage agreed to some extent with Elkenany et al.30, who isolated Salmonella from chickens at 13.5%. Previous studies included lower isolation rates than those recorded in this study1,31, Abd El-Ghany et al.32 and Ibrahim et al.33, who isolated Salmonella from chickens with percentages of 10.37%, 10.9%, 7.03% and 6.5%, respectively. However, a study conducted by Elkenany et al.34 isolated Salmonella at 32%, which represents a higher percentage than that recorded in this study. The variation in the Salmonella isolation rate between this study and other studies may be attributed to differences in geographical locations, sampling times and breeds. El-Sharkawy et al.1 found that higher infection rates may occur because of deficiencies in hygienic measures and biosecurity programs in chicken farms, which facilitate the spread of infections.

In our study, 6 serotypes of Salmonella were identified, including S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Santiago, S. Colindale, S. Takoradi and S. Daula. Another research study detected S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Infantis, S. Kentucky, S. Newport and S. Derby from broiler chickens31. Ramatla et al.35 isolated S. Typhimurium, S. Heidelberg, S. Enteritidis, S. Paratyphi B and S. Newport from chicken feces. S. Enteritidis causes paratyphoid cases in poultry and is associated with food-borne illness in human6. It was the most predominant serotype reported in this study, which agreed with7 Abd El-Ghany et al.32, Velasquez et al.36 and Elkenany et al.34. However, our results varied from Islam et al.37, who found that S. Pullorum was the most isolated serotype recovered from broiler chickens.

Concerning the disc diffusion tests performed in the present study, the results showed the presence of high resistance against SAM (73.08%), followed by AMX, OT (69.23%, for each), S and CT (57.69%, for each). Meanwhile, low resistance was recorded with DO, SXT, FFC (46.15%, for each) and N (30.77%). These findings were in near similarity with those of Hardiati et al.38, who reported that Salmonella isolated from chicken farms was resistant to OT and ampicillin (AM) with (75%), Islam et al.39, who showed resistance against AM (75%), N (50%) and DO (50%). Meanwhile, Velasquez et al.36 recorded a higher resistance of Salmonella isolates against S, and Alam et al.40 recorded resistance against AM and S of 82.85% and 77.14%, respectively. However, Wang et al.41 reported higher resistance against AM and CT with percentages of 97.6% and 51.2%, respectively. Most of the isolated Salmonella in this study showed multidrug resistance with high MDRI, which agreed with studies conducted by Elkenany et al.34, Xu et al.42 and Ibrahim et al.33.

After the establishment of Salmonella, primarily in the ceca43, it is very difficult to eliminate and reduce shedding without using specific antibiotics. Therefore, a crucial step in ensuring food safety is to reduce Salmonella colonization and environmental shedding44. Some studies have indicated that giving probiotic bacteria during the prenatal period of chickens can significantly reduce Salmonella colonization and fecal shedding10,45. Our results showed 100% egg hatchability, no gross abnormalities and an absence of embryonic deaths after in ovo inoculation of the probiotic with florfenicol. The hatchability was lowered in groups 1 and 2 (non-inoculated) with percentages of 86.7% and 93.3%, respectively. The recorded results agreed with those of Tavakkoli et al.29, who reported that the inoculation of florfenicol in eggs resulted in normal embryos with no gross abnormalities. Our results agreed to some extent with Rizk et al.18, who found that the inoculation of probiotic in ovo was associated with higher hatchability and lower embryonic mortalities. However, a research study conducted by Silva et al.46 reported that the hatchability of eggs inoculated with probiotics was 86.25%, and this finding was lower than that in our study.

Regarding the health status of the challenged chicks, clinical signs appeared on the chicks in the positive control group (2), group 3 and group 4. Few chicks in group 5 showed slight diarrhea, which disappeared rapidly after 2 days. Moralities were recorded only in the positive control group (30%) with PM lesions: internal organs congestion, enteritis, enlarged liver with hemorrhages, unabsorbed yolk sac and pasted vent. All chicks in groups 3, 4 and only 3 chicks in group 5 showed enteritis. In ovo inoculation of probiotic and florfenicol individually did not prevent the appearance of clinical signs and PM lesions. On the other hand, the majority of chicks in group 5, which were inoculated in ovo with both the probiotic and florfenicol, showed an absence of signs and PM lesions with significant improvements in growth performance parameters compared to the other groups. showed improvement. Rizk et al.18 found that eggs inoculated with probiotics showed significant improvement in growth performance.

Colonization of multidrug-resistant S. Enteritidis was counted in cecal samples of posthatched chicks using RT‒PCR, and the results showed that all chicks in groups 3 and 4 showed lower colonization than the positive control group. Group 5 showed lower colonization in only 3 chicks, and the other chicks showed no colonization. Our findings may be related to the initial probiotic colonization and presence of florfenicol, which stimulate the development and maturation of the immune system and prevent pathogenic bacteria from colonizing by competitive exclusion11. Our results agreed to some extent with De Oliveira et al.16, who reported a significant reduction in the number of S. Enteritidis-positive chicks when they were inoculated in ovo with E. faecium and continued to receive it in the diet. Meanwhile, Yamawaki et al.47 found that in ovo inoculation with Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. salivarius or L. fermentum did not prevent S. Enteritidis colonization in poultry ceca.

Salmonella was recorded from diseased broiler chickens with a prevalence of 13%. Six Salmonella serotypes were detected (S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Santiago, S. Colindale, S. Takoradi and S. Daula), and the most predominant serotype was S. Enteritidis (most of the isolates showed high MDRI). In ovo inoculation of probiotics with florfenicol not only improved egg hatchability and chick growth performance parameters but also prevented the infection of multidrug-resistant S. Enteritidis post hatching. Further studies should be applied to study the effect of both probiotics and florfenicol on Salmonella colonization in- ovo and after hatching.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the members of the poultry farms especially the farm workers (livestock contact) for helping us in sample collection.

Author contributions

N. M. N. conceived and designed the experiments. N. M. N., M. M. T., M. M. E., A. S., H. M. H., A. E. Y. and R. M. R., participate in the practical part. N. M. N., M. M. T. and M. M. E., analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. M. M. E. and N. M. N. equally contributed.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-36238-6.

References

- 1.Castro-Vargas RE, Herrera-Sánchez MP, Rodríguez-Hernández R, Rondón-Barragán IS. Antibiotic resistance in Salmonella spp. isolated from poultry: A global overview. Veterinary World. 2020;13(10):2070–2084. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.2070-2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Sharkawy H, Tahoun A, El-Gohary AA, El-Abasy M, El-Khayat F, Gillespie T, Kitade Y, Hafez HM, Neubauer H, El-Adawy H. Epidemiological, molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from chicken farms in Egypt. Gut Pathog. 2017;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s13099-017-0157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortés V, Sevilla-Navarro S, García C, Marín C, Catalá-Gregori P. Monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends in Salmonella spp. from poultry in Eastern Spain. Poultry Sci. 2022;101:101832. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roche SM, Holber S, Le Vern Y, Rossignol C, Rossignol A, Velge P, Virlogeux-Payant I. A large panel of chicken cells are invaded in vivo by Salmonella Typhimurium even when depleted of all known invasion factors. Open Biol. 2021;11:210117. doi: 10.1098/rsob.210117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The European Union One Health 2019 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Barbosaa FD, Neto OC, Batistaa DFA, de Almeidaa AM, Rubio MD, Alves LBR, Vasconcelos RD, Barrowc P, Junior AB. Contribution of flagella and motility to gut colonisation and pathogenicity of Salmonella Enteritidis in the chicken. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017;48:754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gantois I, Ducatelle R, Pasmans F, Haesebrouck F, Gast R, Humphrey TJ, Van IF. Mechanisms of egg contamination by Salmonella Enteritidis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33:718–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruvalcaba-Gómez JM, Villagrán Z, Valdez-Alarcón JJ, Martínez-Núñez M, GomezGodínez LJ, Ruesga-Gutiérrez E, Anaya-Esparza LM, ArteagaGaribay RI, Villarruel-López A. Non-antibiotics strategies to control Salmonella infection in poultry. Animals. 2022;12:102. doi: 10.3390/ani12010102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain S, Yadav H, Sinha PR. Probiotic Dahi containing Lactobacillus casei protects against Salmonella Enteritidis infection and modulates immune response in mice. J. Med. Food. 2009;12:576–583. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashemzadeh Z, Karimi MAT, Rahimi S, Razban V, Zahraei TS. Prevention of Salmonella colonization in neonatal broiler chicks by using different routes of probiotic administration in hatchery evaluated by culture and PCR techniques. J. Agric. Sci. Tech. 2010;12:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J, Idris U, Harmon B, Hofacre C, Maurer JJ, Lee MD. Diversity and succession of the intestinal bacterial community of the maturing broiler chicken. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:6816–6824. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.11.6816-6824.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foye OT, Black BL. Intestinal adaptation to diet in the young domestic and wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2006;143:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menconi A, Wolfenden AD, Shivaramaiah S, Terraes JC, Urbano T, Kuttel J, Kremer C, Hargis BM, Tellez G. Effect of lactic acid bacteria probiotic culture for the treatment of Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg in neonatal broiler chickens and turkey poults. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:561–565. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-01220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamed, E. A., Abdelaty, M. F., Sorour, H. K., Roshdy, H., AbdelRahman, M. A., Magdy, A., Ibrahim, W. A., Sayed, A., Mohamed, H., Youssef, M. I., Hassan, W. M., Badr, H. Monitoring of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bacteria Isolated from Poultry Farms from 2014 to 2018. Veterinary Medicine International, 6739220 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Das T, Rana EA, Dutta A, Bostami MB, Rahman M, Deb P, Nath C, Barua H, Biswas PK. Antimicrobial resistance profiling and burden of resistance genes in zoonotic Salmonella isolated from broiler chicken. Veterinary Med. Sci. 2022;8:237–244. doi: 10.1002/vms3.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Oliveira JE, van der Hoeven-Hangoor E, van de Linde IB, Montijn RC, van der Vossen JMBM. In ovo inoculation of chicken embryos with probiotic bacteria and its effect on post hatch Salmonella susceptibility. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:818–829. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shehata AM, Paswan VK, Attia YA, Abdel-Moneim AME, Abougabal MS, Sharaf M, Elmazoudy R, Alghafari WT, Osman MA, Farag MR, Al agawany, M. Managing Gut microbiota through in ovo nutrition influences early-life programming in broiler chickens. Animals. 2021;11:3491. doi: 10.3390/ani11123491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizk YS, Beshara MM, Al-Mwafy AA. Effect of in-ovo injection with probiotic on hatching traits and subsequent growth and physiological response of hatched Sinai chicks, Egypt. Poult. Sci. 2018;38:439–450. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shibat El-hamd DMW, Ahmed HM. Effect of Probiotic on Salmonella Enteritidis infection on broiler chickens, Egypt. J. Chem. Environ. Health. 2016;2(2):298–314. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krysiak K, Konkol D, Korczynski M. Overview of the use of probiotics in poultry production. Animals. 2021;11:1620. doi: 10.3390/ani11061620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sweetman SC, Pharm B, Pharm SF, editors. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronette G. Pharmacokinetics and Bioequivalence of Florfenicol Oral Solution Formulations (Flonicol® and Veterin® 10%) in Broiler Chickens. J. Bioequivalence Bioavailability. 2012;4(1):1–5.16406824. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavakkoli H, Derakhshanfar A, Gooshki SN. The effect of florfenicol egg-injection on embryonated chicken egg. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biom. Res. 2013;2(2):496–503. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ISO 6579-1. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuff- horizontal method for detection of enumeration and serotyping Salmonella SPP. International standard (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Barrow GI, Feltham RKA. Cowan and Steel's Manual for the Identification of Medical Bacteria. 3. Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kauffman F. Serological Diagnosis of Salmonella Species. Kauffman white scheme Minkagaord; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finegold SM, Martin ET. Diagnostic Microbiology. 6. The CV Mosby Company; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2020).

- 29.Daum LT, Barnes WJ, McAvin JC, Neidert MS, Cooper LA, Huff WB, Gaul L, Riggins WS, Morris S, Salmen A, Lohman KL. Real-time PCR detection of Salmonella in suspect foods from a gastroenteritis outbreak in Kerr County, Texas. J. Clin. Microbio. 2002;40(8):3050–3052. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3050-3052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elkenany RM, Eladl AH, El-Shafei RA. Genetic characterisation of class 1 integrons among multidrug-resistant Salmonella serotypes in broiler chicken farms. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018;14:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soliman S, Seida AA, Zou El-Fakar S, Yousse YI, El-Jakee J. Salmonella infection in Broiler flocks in Egypt. Biosci. Res. 2018;201815(3):1925–1930. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abd El-Ghany WA, El-Shafii SA, Hatem ME. A survey on Salmonella species isolated from chicken flocks in Egypt. Asian J. Animal Vet. Adv. 2012;7(6):489–501. doi: 10.3923/ajava.2012.489.501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim S, Wei HL, Lai SY, Mustapha ZCW, Zalati CWS, Aklilu E, Mohamad M, Kamaruzzaman NF. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli isolated from broilers in the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Antibiotics. 2021;10:579. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elkenany R, Elsayed MM, Zakaria AI, El-sayed SA, Rizk MA. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and virulence genotyping of Salmonella enterica serovars recovered from broiler chickens and chicken carcasses in Egypt. BMC Vet. Res. 2019;15:124. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1867-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramatla TA, Mphuthi N, Ramaili T, Taioe MO, Thekisoe OMM, Syakalima M. Molecular detection of virulence genes in Salmonella spp. isolated from chicken faeces in Mafikeng, South Africa. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2020;91:51994. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v91i0.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velasquez CG, Macklin KS, Kumar S, Bailey M, Ebner PE, Oliver HF, Martin-Gonzalez Singh M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Salmonella isolated from poultry farms in southeastern USA. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:2144–2152. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Islam MJ, Mahbub-E-Elahi ATM, Ahmed T, Hasan MK. Isolation and identification of Salmonella spp. from broiler and their antibiogram study in Sylhet, Bangladesh. J. Appl. Biol. Biotech. 2016;4(3):546–551. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardiati A, Safika S, Pasaribu FH, Wibawan IWT. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella Sp. isolated from several chicken farms in West Java Indonesia. Jurnal Kedokteran Hewan. 2022;16(1):6–11. doi: 10.21157/j.ked.hewan.v16i1.18944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Islam KN, Eshaa E, Hassan M, Chowdhury T, Zaman SU. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern and identification of multidrug resistant novel Salmonella strain in poultry chickens of hathazari region in Chattogram, Bangladesh. Adv. Microbiol. 2022;12:53–66. doi: 10.4236/aim.2022.122005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alam SB, Mahmud M, Akter R, Hasan M, Sobur A, Nazir KNH, Noreddin A, Rahman T, El Zowalaty ME, Rahman M. Molecular detection of multidrug resistant Salmonella species isolated from broiler farm in Bangladesh. Pathogens. 2020;9:201. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Wang H, Li T, Liu F, Cheng Y, Guo X, Wen G, Luo Q, Shao H, Pan Z, Zhang T. Characterization of Salmonella spp. isolated from chickens in Central China. BMC Vet. Res. 2020;16:299. doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02513-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y, Zhou X, Jiang Z, Qi Y, Ed-dra A, Yue M. Epidemiological investigation and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella isolated from Breeder Chicken Hatcheries in Henan, China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:497. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nisbet DJ, Ricke SC, Scanlan CM, Corrier DE, Holllster AG, Deloach JR. Inoculation of broiler chicks with a continuous-flow derived bacterial culture facilitates early cecal bacterial colonization and increases resistance to Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Food Prot. 1994;57:12–15. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-57.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craven SE. Salmonella Typhimurium, hydrophobic antibiotics, and the intestinal colonization of broiler chicks. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1995;4:333–340. doi: 10.1093/japr/4.4.333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hosseini-Mansoub N, Vahdatpour T, Arjomandi M, Vahdatpour S. Comparison of different methods of probiotic prescription against Salmonella infection in hatchery broiler chicken. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2011;5:1857–1860. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva IGO, Vellano IHB, Moraes AC, Lee IM, Alvarenga B, Milbradt EL, Hataka A, Okamoto AS, Andreatti FRL. Evaluation of a probiotic and a competitive exclusion product inoculated in ovo on broiler chickens challenged with Salmonella Heidelberg. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2017;19(1):019–026. doi: 10.1590/1806-9061-2016-0409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamawaki RA, Milbradt EL, Coppola MP, Rodrigues JCZ, Andreatti FRL, Padovani CR, Okamoto AS. Effect of immersion and inoculation in ovo of Lactobacillus spp. in embryonated chicken eggs in the prevention of Salmonella Enteritidis after hatch. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:1560–1563. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.