Abstract

The nuclease activity of FEN-1 is essential for both DNA replication and repair. Intermediate DNA products formed during these processes possess a variety of structures and termini. We have previously demonstrated that the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe FEN-1 protein Rad2p requires a 5′-phosphoryl moiety to efficiently degrade a nick-containing substrate in a reconstituted alternative excision repair system. Here we report the effect of different 5′-terminal moieties of a variety of DNA substrates on Rad2p activity. We also show that Rad2p possesses a 5′→3′ single-stranded exonuclease activity, similar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad27p and phage T5 5′→3′ exonuclease (also a FEN-1 homolog). FEN-1 nucleases have been associated with the base excision repair pathway, specifically processing cleaved abasic sites. Because several enzymes cleave abasic sites through different mechanisms resulting in different 5′-termini, we investigated the ability of Rad2p to process several different types of cleaved abasic sites. With varying efficiency, Rad2p degrades the products of an abasic site cleaved by Escherichia coli endonuclease III and endonuclease IV (prototype AP endonucleases) and S.pombe Uve1p. These results provide important insights into the roles of Rad2p in DNA repair processes in S.pombe.

INTRODUCTION

An integral part of many cellular processes that affect genomic stability is the activity of DNA nucleases. Nucleases play a role in essential cellular events that include helping to ensure that the fidelity of DNA synthesis is maintained and removing potentially deleterious lesions in DNA. Disruptions of these activities could lead to events such as mutation, cell death and neoplastic transformation. In general, nucleases can be very non-specific in nature or can be classified based on their ability to recognize specific conformations in DNA.

The Rad2 super-family of nucleases, named for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD2 gene product involved in nucleotide excision repair (NER), is comprised of several sub-groups of proteins that all possess two conserved regions of homology, the N and I blocks (reviewed in 1). The overall number of amino acids and the length of the spacer region between the conserved blocks of homology differentiate the sub-classes of this family and presumably account for the variations observed in substrate specificity. The first sub-group is the XPG-like proteins that are responsible for the 3′ incision event during NER and these are the largest in size of the Rad2 family proteins. XPG deficiencies can lead to the disease xeroderma pigmentosum resulting in a predisposition to the development of skin cancers and other abnormalities (2,3). The second sub-group, which shows the widest range of substrate specificity, is the FEN-1 (flap endonuclease/five prime exonuclease) family of nucleases. Exonuclease I-like proteins comprise the third sub-group and have been implicated in recombination and excision repair events (4–8).

The FEN-1 sub-group of this family is interesting primarily due to the multiple nuclease activities it possesses. One of the first characterized activities of FEN-1 proteins was a 5′→3′ double-stranded DNA exonuclease activity essential for the completion of lagging strand DNA synthesis (9–12). The search for structure-specific endonucleases led to the identification of the murine FEN-1 protein and subsequent cloning of this gene led to the determination that this protein was homologous to the exonucleases involved in replication (13). The substrate specificities of FEN-1 proteins are variable but the nuclease activities can be classified as either a structure-specific endonuclease or 5′→3′ double-strand DNA exonuclease. The endonuclease activity of FEN-1 makes incisions near the branch point of 5′-flap-, pseudo-Y- or double flap-containing DNA substrates. The 5′→3′ exonuclease activity degrades double-stranded DNA substrates containing nicks, gaps or blunt or 5′-recessed ends (13–16). The ability to recognize and cleave such a wide variety of substrates suggests potential FEN-1 involvement in many different DNA processing events.

The earliest evidence for a connection between FEN-1 proteins and DNA repair pathways emerged from the biochemical analysis of mammalian FEN-1 (DNase IV) (17). It was shown that the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of DNase IV could degrade DNA containing UV photoproducts. A mutation abolishing the corresponding exonuclease activity in Escherichia coli, which is an inherent activity of DNA polymerase I, resulted in sensitivity to UV radiation, confirming that this type of activity was important for the repair of UV light-induced DNA damage (18). UV photoproducts, which are primarily comprised of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and 6–4 photoproducts (19,20) are often repaired by photolyase-mediated direct reversal or NER (21). FEN-1 proteins have not been shown to have an involvement in either of these DNA repair pathways, but the Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad2+ gene and its product Rad2p provide some insight into an additional repair pathway for UV photoproducts that is present in fission yeast and several other organisms.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Neurospora crassa and Bacillus subtilis possess homologs of an endonuclease Uve1p (encoded by the uve1+ gene) which is an essential component of the alternative excision repair (AER) pathway (22–24). Uve1p initiates repair by cleaving immediately 5′ to a variety of DNA lesions, including various UV photoproducts, base mispairs, abasic sites and platinum G-G diadducts (22,25,26). rad2+ was identified as a component of the AER pathway initially through epistasis analysis (27,28) and has subsequently been shown to process a substrate containing a Uve1p-cleaved UV photoproduct as well as a base mispair cleaved product (29,30). Recently, Rad2p was identified as an essential component of an in vitro reconstituted AER system. In this system, damage was excised through the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of Rad2p and not through its flap endonuclease activity (30). rad27 mutants from S.cerevisiae, which does not possess a uve1 homolog, also display a mild sensitivity to UV radiation, possibly indicating another mechanism in which FEN-1 may be involved in the repair of UV-induced lesions (31).

Yeast FEN-1 mutants display a mutator phenotype in a variety of assays that led to the speculation that they also function in an E.coli MutS-like mismatch repair pathway (32). Mutation spectra from this type of analysis, however, indicated a predominance of insertion mutations, in addition to a variety of other, less frequently occurring types of mutations, and are inconsistent with mutation spectra from other members of the MutS pathway (33,34). Although there is still the possibility that FEN-1 plays a minor role in MutS-dependent mismatch repair (in addition to a role in a MutS-independent mismatch repair pathway), it is likely that a majority of these insertion mutations arise from defects that occur during DNA replication.

In addition to UV radiation, many FEN-1 mutants are also sensitive to the alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (31,32,35) that generates DNA lesions that are often processed through the base excision repair (BER) pathway (21). Following removal of a damaged base by a DNA glycosylase, the BER pathway branches into two sub-pathways processing different repair patch sizes. The short patch branch of BER involves the replacement of a single nucleotide whereas the long patch branch of BER has a requirement for a FEN-1 protein and possesses a repair patch of ∼2–6 nt (36). It has been speculated that, at least in humans, the type of DNA glycosylase that initiates BER may dictate the subsequent repair steps (37).

In studying the role of Rad2p in AER, it was determined that the termini resulting from a Uve1p-mediated DNA strand scission event were critical for subsequent processing by Rad2p. Rad2p required a 5′-phosphoryl moiety to efficiently degrade a substrate that mimicked a Uve1p-cleaved C/A base mispair-containing substrate (30). It was of interest to determine if Rad2p also requires a 5′phosphoryl moiety to process other substrates. In light of the fact that Uve1p also initiates the repair of AP sites and that other FEN-1 proteins have been shown to process cleaved AP sites (38–41), it was also of interest to determine whether or not Rad2p could process AP sites cleaved by Uve1p or a prototypical AP endonuclease or an AP lyase. In addition to a 5′-terminal preference, our results confirm a role for Rad2p in the BER pathway and suggest that, in addition of the nature of the 5′-terminal moiety, the sequence context of the substrate can also influence Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins, enzymes and chemicals

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rad2p was overexpressed and purified as described previously (16). Briefly, recombinant protein was expressed in S.cerevisiae as an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. The rad2+ cDNA was cloned into the pYEX-4T1 CuSO4-inducible expression vector and expressed in DY150 cells. Cells were harvested, lysed and GST–Rad2p was purified by glutathione affinity chromatography. Recombinant GST was produced and purified in an identical manner to GST–Rad2p and was included in all of the assays as a control for non-specific contaminating nucleases in the GST–Rad2p preparations. T4 polynucleotide kinase and terminal transferase were purchased from Promega. Escherichia coli uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). [α-32P]ddATP was purchased from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). Escherichia coli endonucleases III and IV were gifts from Dr Yoke Wah Kow (Emory University, Atlanta, GA). All other chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available.

Oligonucleotides

The oligonucleotides used in the construction of various DNA substrates (Table 1) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and the Emory University Microchemical Facility (Atlanta, GA).

Table 1. Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| A | 5′-ATGTGGAAAATCTCTAGCAGGCTGCAGGTCGAC-3′ |

| B | 5′-CAGCAACGCAAGCTTG-3′ |

| C | 5′-GTCGACCTGCAGCCCAAGCTTGCGTTGCTG-3′ |

| D | 5′-TAGGTCAAGCGTTAGCATGCCTGCACGA-3′ |

| E | 5′-ATTAAGCAATTCGTAATGCATTACAAGTCGCA-3′ |

| F | 5′-ACTAAGCAATTCGTAATGCATTACAAGTCGCA-3′ |

| G | 5′-TGCGACTTGTAATGCATTACGAATTGCTTAATTCGTGCAGGCATGCTAACGCTTGACCTA-3′ |

| H | 5′-CAGTTGACGATAGCCAGTACCGTACACG-3′ |

| I | 5′-CCGGATCTAGCAGGTCAGAATTGAGCCTAGCT-3′ |

| J | 5′-CGGGATCTAGCAGGTCAGAATTGAGCCTAGCT-3′ |

| K | 5′-AGCTAGGCTCAATTCTGACCTGCTAGATCCGGCGTGTACGGTACTGGCTATCGTCAACTG-3′ |

| L | 5′-CATGCCTGCACGAATTAAGCAATTCGTAAT-3′ |

| M | 5′-ATTACGAATTGCTTAATTCGTGCAGGCATG-3′ |

| N | 5′-CATGCCTGCACGAUTTAAGCAATTCATAAT-3′ |

| O | 5′-ATTATGAATTGCTTAATTCGTGCAGGCATG-3′ |

U, uracil.

Substrates

Oligonucleotides were electrophoresed on a denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel, visualized by UV shadowing, eluted from the gel in TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) and ethanol precipitated. Derivatives of the flap, AT nick, GC nick, single-stranded and double-stranded DNA substrates, containing either a 5′-phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl, were generated. To generate these substrates 1 nmol of oligos A, E, F, I, J and L (Table 1) were phosphorylated by treatment with 20 U T4 polynucleotide kinase (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 50 µg/ml BSA) for 60 min at 37°C (42). Phosphorylated oligos were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Oligos A, E, F, I, J, L and N were 3′-end-labeled using terminal transferase and [α-32P]ddATP (43). Oligos A–C were annealed to generate flap structures. Oligos D, E, (F) and G were annealed to generate substrate AT Nick. H, I, (J) and K were annealed to generate substrate GC Nick. L and M were annealed for the double-stranded substrate, substrate DS-30mer. N and O were annealed to generate the uracil-containing substrate U-30mer for use in generating the abasic site-containing substrate AP-30mer (Fig. 1). End-labeled oligonucleotides were annealed to the appropriate complementary strand in TE buffer plus 50 mM MgCl2 by heating to 70°C followed by slowly cooling to room temperature. Duplex DNA substrates were purified on a 20% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel, purified as described above, resuspended in TE buffer and stored at –20°C.

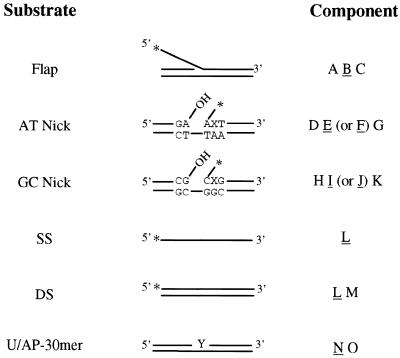

Figure 1.

Potential DNA substrates for Rad2p. All substrates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Substrates AT Nick and GC Nick were generated with oligos E and I, respectively, when the second base (X) 3′ from the site of the nick is Watson–Crick base paired. Oligos F and J are used when this position contains either a C/A mispair in AT Nick or a G/G base mispair in the GC Nick sequence context. All substrates (except for the U-30mer) were constructed with either a 5′-terminal phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl moiety on the end-labeled strand as indicated by an asterisk. Y indicates the position of the U or AP site in the U-30mer or AP-30mer. Oligonucleotides that were 3′-end-labeled in these substrates are underlined. Complete oligonucleotide sequences are presented in Table 1.

Preparation of AP substrate

3′-End-labeled duplex substrate U-30mer (20 pmol) was incubated with 6 U UDG for 30 min at 37°C in UDG buffer (30 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM NaCl) to generate the AP site-containing oligonucleotide substrate (substrate AP-30mer). The DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and with 0.1% 8-hydroxyquinoline, ethanol precipitated, resuspended in TE buffer and stored at –20°C. The presence of the AP site was confirmed by treatment with 1 M piperidine at 90°C for 20 min.

Rad2p reactions

Aliquots of 300 fmol of 3′-end-labeled substrate were incubated with ∼1 µg GST–Rad2p in a 20 µl reaction containing 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, and 7 mM MgCl2 for 90 min at 37°C. The reaction conditions were based on optimal conditions for Rad2p with respect to temperature, pH and divalent cation requirements, which were determined prior to these studies (data not shown). It should be noted that the addition of MnCl2 to the reactions inhibited all Rad2p-associated activities. Reaction mixtures were extracted with PCIA and ethanol precipitated. Labeled samples (∼10 000 c.p.m.) were loaded on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and reaction products were visualized by autoradiography and the extent of Rad2p-mediated substrate processing quantified by phosphorimager analysis (Molecular Dynamics). Maxam and Gilbert base-specific chemical cleavage reaction products for each substrate were run on the gel for DNA size markers.

Rad2p reactions with cleaved AP site substrates

Aliquots of 300 fmol of substrate AP-30mer were incubated in a 10 µl reaction containing 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, and 7 mM MgCl2 with either E.coli endonuclease III (50 ng), endonuclease IV (60 ng) or S.pombe Uve1p (200 ng) for 20 min at 37°C to produce cleaved abasic sites. Rad2p was added and the reactions were brought up to 20 µl and incubated for an additional 20 or 60 min. Reactions were extracted with PCIA, equal counts loaded on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized and quantified as described above. Maxam and Gilbert base-specific chemical cleavage reaction products for 3′-end-labeled U-30mer were run on the gel for DNA size markers.

RESULTS

Influence of DNA secondary structure of nicked substrates on the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of Rad2p

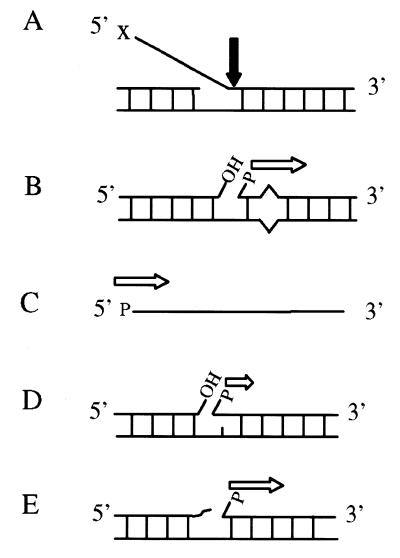

Our previous work has shown that the 5′-phosphoryl moiety resulting from a Uve1p cleavage event at the site of a base mispair is essential for efficient Rad2p-mediated 5′→3′ exonuclease activity (30). The substrate used in this study (substrate AT Nick, Fig. 1) contained a C/A base mispair 2 nt 3′ to the site of the nick, identical to the Uve1p cleavage product of a C/A mispair-containing substrate, with the appropriate 5′-phosphoryl and 3′-hydroxyl moieties (44). Rad2p degradation of substrate AT Nick is characterized by the release of primarily mononucleotides. Rad2p sequentially removes 2–6 nt from this substrate. Based on the release of mononucleotides, we designate this activity a 5′→3′ exonuclease activity (30). This is in contrast to Rad2p-mediated incision events that occur near the branch point of substrates containing single-stranded 5′-overhangs, which we designate an endonuclease activity (16). Replacement of the 5′-phosphoryl with a hydroxyl group significantly altered Rad2p-mediated 5′→3′ exonuclease degradation of this substrate. This prompted us to determine what other features of this substrate might also affect Rad2p activity. Variations of this substrate (substrate AT Nick, Fig. 1) were generated that included the original C/A base mispair or a normal T/A base pair. Each of these substrates contained either a 5′-phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl moiety at the site of the nick. As previously shown, in the presence of the C/A base mispair and a 5′-phosphoryl moiety, Rad2p degrades ∼42% of this substrate by 5′→3′ exonuclease activity, removing primarily 1–5 nt. The major reaction products are a set of duplexes containing gaps of 1–5 nt in size (exo gap), as indicated to the right of the gel (Fig. 2A, lane 3). The presence of faster migrating bands (lane 3) is indicative of processive Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity producing short, terminal digestion products (30). Replacement of the 5′-phosphoryl with a 5′-hydroxyl moiety results in a significant decrease in Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity to <6% cleavage (lanes 4–6). Replacement of the C/A mispair with a normal T/A base pair in the presence of a 5′-phosphoryl moiety at the nick site also decreases Rad2p activity in a similar manner, to ∼5% cleavage (lanes 7–9). The combination of the above two changes (T/A base pair with 5′-hydroxyl at the nick site) also produces the same result, with overall cleavage reduced to ∼3% (lanes 10–12). This indicates that the presence of both the 5′-phosphoryl group and the C/A base mispair are required for Rad2p to process the AT Nick substrate. Recombinant GST, produced and purified in exactly the same manner as Rad2p, was included in all experiments as a control for the possibility of trace contaminating nucleases. There was no evidence for contaminating exonuclease activity when equimolar amounts of GST were incubated with any of the nicked substrates, indicating that the activity observed was Rad2p-mediated (lanes 2, 5, 8 and 11).

Figure 2.

The effect of the nature of the 5′-terminal moiety of a nick and its sequence context on the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of Rad2p. Rad2p was incubated with 3′-end-labeled, nicked substrates with different DNA sequence contexts. Variations of the substrates included the nature of the 5′-terminal moiety at the site of the nick (5′-phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl group) as well as the base mispair 2 nt 3′ to the site of the nick. Incubation with recombinant GST purified in an identical manner to Rad2p was used in this and subsequent experiments to detect the presence of potential trace contaminating nucleases. The asterisk indicates the location of the 32P label. X, the position of the base mispair. (A) AT Nick. Lanes 1, 4, 7 and 10, untreated; lanes 2, 5, 8 and 11, GST alone; lanes 3, 6, 9 and 12, Rad2p. The 5′-terminal phosphoryl moiety (lanes 1–3 and lanes 7–9) was replaced with a hydroxyl moiety (lanes 4–6 and lanes 10–12). The major Rad2p-mediated reaction products (exo gap area) are indicated to the right of the gel in brackets. The faster migrating bands indicate processive Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity (30). (B) GC Nick. Reactions were carried out in a manner similar to those used for the AT Nick substrate. Lanes 1, 4, 7 and 10, untreated; lanes 2, 5, 8 and 11, GST alone; lanes 3, 6, 9 and 12, Rad2p. The presence of the base mispair (MM) and the 5′-terminal phosphoryl (P) or 5′-hydroxyl (OH) moiety are indicated above each gel. The substrate structures below each gel show the position of the base mispair and the sequence context in the immediate vicinity of the nick. To the left of each gel are the base-specific chemical cleavage products of the (A) AT and (B) GC Nick substrates (DNA size/position markers). DNA strand scission products were separated on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography as described in Materials and Methods.

A second nicked substrate was generated that differed in sequence primarily within the region of the nick and which contained predominantly G/C base pairs (substrate GC Nick, Fig. 1). This substrate was used to determine the contribution of the local sequence context and nature of the base mispair on Rad2p activity. As with the AT Nick substrate, additional substrate variations were generated that included the normal G/C base pair with both configurations containing either a 5′-phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl moiety at the site of the nick. There was no observed processing of any of the variations of the GC Nick substrate by Rad2p even in the presence of a 5′-phosphoryl group and a G/G base mispair (Fig. 2B, lanes 2, 5, 8 and 11).

In order to further test the effect of local sequence context on Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity, double-stranded substrates with blunt or AT- or GC-rich termini were generated. There was no significant difference in Rad2p-mediated degradation of these substrates, which was, in both cases, ∼12% (data not shown). These findings indicate that several factors may contribute to the overall secondary structure of the substrates and, when in combination with loosely base paired regions, produces a structure efficiently degraded by Rad2p. It is also possible that in vivo some substrates require the activity of accessory proteins (e.g. helicases) prior to Rad2p 5′ nuclease activity or may be processed by another protein in place of Rad2p. This possibility is supported by the lack of Rad2p activity on substrate GC Nick, which would be expected to have stronger base pairing in the vicinity of the nick site compared to the situation with substrate AT Nick (Fig. 1).

Rad2p possesses a 5′→3′ single-stranded DNA exonuclease activity that is dependent on the presence of a 5′-terminal phosphoryl moiety

We also wished to determine if the 5′-terminal moiety plays a role in the processing of other types of substrates by Rad2p. The recombinant version of Rad2p used in these studies has previously been shown to possess a 5′→3′ double-stranded DNA exonuclease activity, which is less efficient than the exonucleolytic degradation of the nicked substrate shown in Figure 2A (16). When Rad2p is incubated with 3′-end-labeled, double-stranded DNA containing either a 5′-phosphoryl (substrate DS 5′-P) or 5′-hydroxyl moiety (substrate DS 5′-OH), there are no significant differences in the observed 5′→3′ exonuclease activities on these substrates (Fig. 3, left, lanes 3 and 6). Rad2p cleaves ∼12% of DS 5′-OH and 17% of DS 5′-P.

Figure 3.

Rad2p processing of single- and double-stranded DNA. Aliquots of 300 fmol double-stranded (DS, left) or single-stranded (SS, right) DNA were incubated with Rad2p for 90 min at 37°C. The asterisk indicates the location of the 32P label. The major Rad2-mediated exonuclease products (exo) are indicated with brackets to the right of the gel. Substrates contained either a 5′-terminal phosphoryl (P) or hydroxyl moiety (OH) as indicated. Lanes 1 and 4, untreated; lanes 2 and 5, GST alone; lanes 3 and 6, Rad2p. Lanes are designated below the right panel to indicate a horizontal shift of the reaction products that occurred during electrophoresis.

In addition, Rad2p was also tested for activity on 3′-end-labeled, single-stranded substrates containing a 5′-phosphoryl (substrate SS 5′-P) or 5′-hydroxyl moiety (substrate SS 5′-OH). Interestingly, Rad2p degraded substrate SS 5′-P (∼19%) while showing no activity on substrate SS 5′-OH (Fig. 3, right, lanes 3 and 6), as indicated by the degradation products visualized at the top and bottom of the gel. GST control reactions showed no evidence of the presence of contaminating 5′-phosphoryl-specific exonuclease activity (right, lanes 2 and 5).

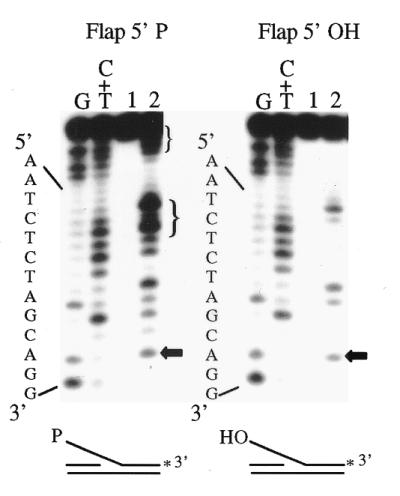

Rad2p incises flap substrates independently of a 5′-phosphoryl moiety

5′-Flap structures are thought to be produced as a result of strand displacement synthesis during DNA replication and repair or as recombination intermediates (39,45). Due to the differences in circumstances by which these structures may be formed, the 5′-terminal moiety of the flap can vary. As a 5′-phosphoryl moiety has been shown to be important for Rad2p-mediated exonuclease degradation of a nicked substrate, we wanted to determine if there was also a similar effect on flap endonuclease activity. A 3′-end-labeled flap substrate was generated that contained either a 5′-phosphoryl (substrate Flap 5′-P) or 5′-hydroxyl moiety (substrate Flap 5′-OH). Rad2p has been previously shown to cleave this 5′-flap structure one base 3′ to the site of the branch point in the duplex region of the substrate (16). Rad2p-mediated flap endonuclease cleavage (indicated by the arrow) is observed on both substrate Flap 5′-P and substrate Flap 5′-OH with the same efficiency, ∼5% (Figure 4, left versus right, lane 2). This indicates that the presence of a 5′-phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl moiety does not influence the flap endonuclease activity of Rad2p. Treatment of substrate Flap 5′-P with Rad2p also results in several other cleavage products that are not present for substrate Flap 5′-OH (Fig. 4, left, lane 2, brackets). These are most likely due to the 5′→3′ single-stranded exonuclease activity described in the previous section.

Figure 4.

Effect of a 5′-terminal phosphoryl moiety on Rad2p-mediated flap endonuclease cleavage. 3′-End labeled substrate Flap 5′-P or Flap 5′-OH (300 fmol) was incubated with no protein (lane 1) or Rad2p (lane 2) for 90 min at 37°C. The asterisk indicates the position of the 32P label. Maxam and Gilbert base-specific chemical cleavage products of the labeled DNA strand are included as size/position markers. The sequence of the labeled strand is indicated on the left. The horizontal arrows to the right of the gels indicate the cleavage products that correspond to one base 3′ to the branch point in the duplex region of the substrate (at the G-G site). Cleavage products indicated by the brackets are probably due to the 5′→3′ single-stranded DNA exonuclease activity of Rad2p described earlier.

Rad2p-mediated degradation of AP site-containing nicks generated by endonuclease III, endonuclease IV or Uve1p

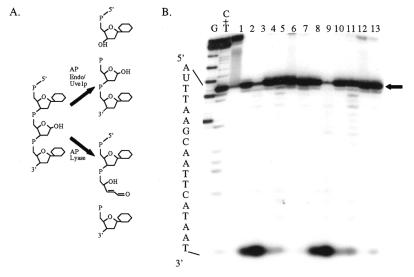

It has been shown both biochemically and genetically that Rad2p homologs are involved in BER and they have been shown to be essential components of the long patch branch of this repair pathway (31,36,46). An AP site is produced during BER following the removal of a damaged base by a DNA glycosylase. Several enzymes can cleave DNA at an AP site resulting in various 5′-terminal moieties and these may play a role in determining subsequent processing events (Fig. 5A). A hydrolytic AP endonuclease can cleave the phosphodiester backbone 5′ to the AP site leaving a 3′-hydroxyl moiety and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate residue. Subsequent to removing a damaged base, DNA glycosylases with associated AP lyase activity can also cleave the AP site 3′ to the site of the lesion via β-elimination, leaving a 5′-phosphoryl moiety and a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (47). More recently identified is the activity of Uve1p from S.pombe, which cleaves an AP site in a manner similar to an AP endonuclease (25,26) with an additional, minor cleavage product one base 5′ to the AP site. Several FEN-1 proteins have been shown to process a substrate containing an AP endonuclease-incised unreduced or chemically reduced AP site either directly as part of a nicked substrate or when incorporated into a 5′-flap substrate (38–41).

Figure 5.

Rad2p-mediated degradation of BER intermediates. (A) Cleavage of an AP site by various DNA repair enzymes. AP endonucleases cleave the phosphodiester backbone 5′ to the AP site leaving a 3′-hydroxyl moiety and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate residue. The major Uve1p cleavage site coincides with the AP endonuclease cleavage site. Enzymes with AP lyase activity cleave 3′ to the abasic site leaving a 5′-phosphoryl moiety and a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde. (B) Rad2p processing of cleaved AP sites. AP 30mer (300 fmol) was incubated with endonuclease III, endonuclease IV or Uve1p for 20 min at 37°C, followed by Rad2p for 20 (lanes 2–7) or 60 min (lanes 8–13). Lane 1, untreated; lanes 2 and 8, endonuclease III; lanes 3 and 9, endonuclease III and Rad2p; lanes 4 and 10, endonuclease IV; lanes 5 and 11, endonuclease IV and Rad2p; lanes 6 and 12, Uve1p; lanes 7 and 13, Uve1p and Rad2p. The arrow indicates the position of the cleaved AP site. Maxam and Gilbert base-specific chemical cleavage reaction products of labeled DNA strands are indicated as DNA size/position markers. The sequence of the labeled strand is indicated to the left of the gel.

Substrate AP-30mer contains a centrally located AP site, following enzymatic removal of uracil (Fig. 1), and was used in order to determine if Rad2p could process this substrate subsequent to cleavage by an AP lyase (endonuclease III), a hydrolytic AP endonuclease (endonuclease IV) or Uve1p. Incubation of 3′-end-labeled substrate AP-30mer with either endonuclease III, endonuclease IV or Uve1p resulted in a major cleavage product at the position of the AP site (Fig. 5B, lanes 2, 4 and 6). Following the addition of Rad2p, the endonuclease III-mediated cleavage product is degraded, as indicated by the presence of faster migrating DNA species (lane 3, bottom of gel). Over 40% of the cleaved AP site is degraded by Rad2p. Only a small fraction of the endonuclease IV- or Uve1p-mediated cleavage product is processed (8 and 2%, respectively) after the 20 min incubation with Rad2p (lanes 5 and 7). Following 60 min of Rad2p treatment, however, there is additional evidence of degradation present, especially in the endonuclease IV and Rad2p reactions, where Rad2p cleavage is increased to 16% (lane 11). The Rad2p-mediated degradation observed here following AP endonuclease cleavage is consistent with that observed with other FEN-1 proteins on similar substrates, which most likely corresponds to a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate nucleotide product (40,41). This indicates that Rad2p is capable of processing the products resulting from cleavage of an AP site by Uve1p, an AP endonuclease or an AP lyase.

DISCUSSION

This study further delineates the substrate specificity of the S.pombe FEN-1 protein Rad2p. Characteristically, FEN-1 proteins possess a 5′ structure-specific endonuclease activity, which also recognizes pseudo-Y and double flap structures and a 5′→3′ double-stranded exonuclease activity that processes substrates containing nicks, gaps and blunt and 5′-recessed ends. We have previously shown the importance of a 5′-phosphoryl moiety on Rad2p-mediated 5′→3′ exonuclease activity for nicked substrates (30), thus the primary interest of this study was to determine whether the nature of the 5′-terminus affected the way Rad2p processes other potential substrates.

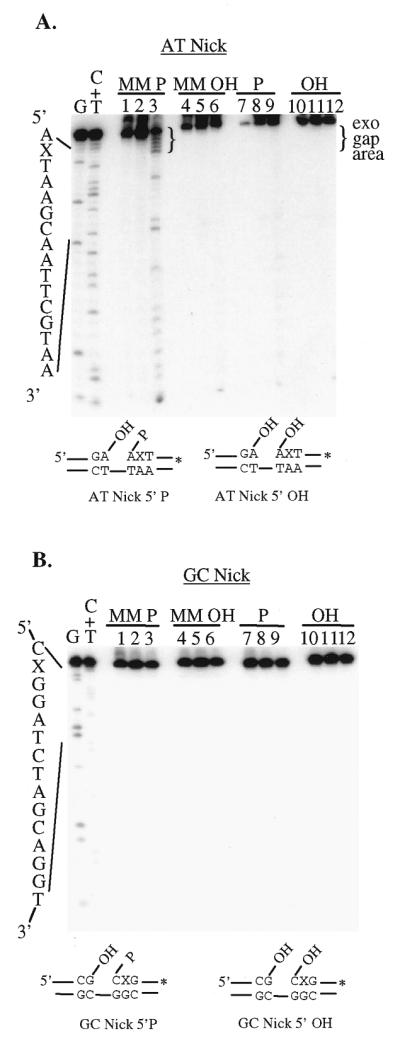

To investigate the effects of the 5′-terminal moiety on Rad2p activity, the DNA substrates used here contain either a 5′-phosphoryl or 5′-hydroxyl moiety. All of the substrates that were processed by Rad2p via either flap endonuclease or 5′→3′ exonuclease activity are displayed in Figure 6. The presence of a 5′-phosphoryl moiety was required for Rad2p processing of both the AT Nick substrate and single-stranded DNA (Figs 2 and 3). Rad2p endonuclease activity was not significantly enhanced by the presence of a 5′-terminal phosphoryl moiety, consistent with results with human FEN-1 (48). Rad2p possesses a 5′→3′ single-stranded exonuclease activity also reported for phage T5 5′→3′ exonuclease and more recently for S.cerevisiae FEN-1 (Rad27p) (49,50), which is dependent upon the presence of a 5′-terminal phosphoryl moiety (Fig. 3). This has not been commonly reported for other FEN-1 proteins. The requirement for a 5′-phosphoryl moiety was also observed for efficient Rad2p-mediated degradation of one of the nick-containing substrates used in this study (48,51). We have previously reported that the recombinant version of Rad2p is unstable (16) and therefore relatively large amounts of protein are required to observe nuclease activities. It is likely that all of the different observed activities are Rad2p-mediated, a notion supported by the absence of any observed activity when GST alone was utilized. With the exception of the AP lyase generated substrate (discussed below), all of the activities shown here for Rad2p have been previously reported for other FEN-1 proteins where a wide range of protein amounts were used (13,16,49,52,53).

Figure 6.

Substrates processed by Rad2p. Rad2p-mediated endonuclease (solid vertical arrow) or 5′→3′ exonuclease activity (horizontal open arrow) are indicated for the various substrates investigated in this study. Changing the 5′-terminal moiety (X) on flap structures (A) did not affect Rad2p-mediated endonuclease activity. Substrates containing a 5′-phosphoryl group were more efficiently degraded by Rad2p as a 5′→3′ exonuclease. Other factors such as the presence of a base mispair or varying the DNA sequence context also influenced Rad2p activity on nicked substrates (B). Single-stranded DNA containing a 5′-phosphoryl moiety (C) is a substrate for the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of Rad2p. Rad2p degrades cleaved AP sites with varying efficiencies. The presence of the 5′-deoxyribose phosphate residue (D) from hydrolytic AP endonuclease or Uve1p cleavage results in a low level of Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity while a 3′-α,β-unsaturated aldehyde (E) in the nick environment does not interfere with Rad2p processing of a 5′-phosphoryl-containing substrate by AP lyase cleavage

Because the alteration of the features of substrate AT Nick led to diminished Rad2p 5′→3′ exonuclease activity (Fig. 2), we conclude that it is the contribution of several factors intrinsic to this substrate that play an important role in Rad2p-mediated degradation. The presence of the base mispair, 5′-phosphoryl moiety and local sequence context are likely to all contribute to decreased base pairing in the vicinity of the site of the nick and may produce a transient single-stranded 5′-overhang. FEN-1 proteins have a higher affinity for binding 5′-flap or pseudo-Y structures in comparison to nick-containing structures (54) and it is possible that the activity we observed on the nicked substrate may be a result of such increased DNA binding. In vivo DNA damage may be induced within a multitude of local sequence contexts and can generate secondary structures that may influence DNA processing by nucleases. We have demonstrated that alterations of the DNA sequence context influence the efficiency of Rad2p activity (substrate GC Nick) and this may indicate that other factors may be required to modulate or replace Rad2p during DNA repair processes.

FEN-1 mutants display sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents that produce lesions repaired by the BER pathway (31,32,35). FEN-1 participates in BER following cleavage of the AP site intermediate (38,39). We show here that Rad2p can directly degrade AP sites cleaved by two different BER proteins (AP endonuclease or AP lyase) via a 5′→3′ exonuclease activity (Fig. 5). The pattern of degradation observed for Rad2p is very similar to that observed for the S.cerevisiae and Xenopus laevis FEN-1 proteins (40,41). Direct processing of AP endonuclease-mediated cleavage products by FEN-1 is relatively inefficient, although it has been shown to be enhanced by PCNA (55). Schizosaccharomyces pombe Uve1p has also been shown to cleave AP sites and produces a cleavage product similar to that of an AP endonuclease (25,26). Rad2p also degrades the Uve1p-cleaved AP site substrate with an efficiency similar to that of an AP endonuclease-cleaved AP site substrate (Fig. 5). Considering the similarities between the Uve1p and AP endonuclease cleavage products, it is likely that steps following Uve1p cleavage at an AP site are related to events that occur during N-glycosylase-initiated BER.

What is the role of FEN-1 proteins during BER in vivo? BER is commonly characterized as short patch (1 nt) or long patch (2–6 nt), with the latter being PCNA-dependent (56,57). In vitro FEN-1 proteins have been shown to be an essential component of the long patch BER pathway (36,58). There is also evidence, however, for FEN-1 involvement in PCNA-independent BER of synthetic AP sites that requires DNA synthesis and probably utilizes the flap endonuclease activity of FEN-1 (40). Early models propose that FEN-1 functions in BER as an endonuclease cleaving a flap substrate that is generated following strand displacement synthesis (59). It is likely, as shown in this study for Rad2p and for other FEN-1 proteins, that processing of a cleaved AP site may also occur by FEN-1 via its 5′→3′ exonuclease prior to DNA synthesis (40,58). It has been hypothesized that in mammalian cells, the type of DNA glycosylase that initiates BER may be a factor in determining whether repair will proceed through the short or long patch branches of BER (37). Monofunctional DNA glycosylases, such as uracil-DNA glycosylase, that require subsequent AP endonuclease cleavage may initiate both short and long patch BER. This is consistent with data that indicate that in S.cerevisiae the repair of uracil-containing substrates results in short and long repair patches (60). Alternatively, repair that is initiated by a DNA glycosylase with an associated AP lyase activity is proposed to proceed through the short patch branch of BER. We provide in vitro evidence that may link Rad2p with AP lyase-associated repair. Dianov et al. have recently demonstrated that thymine glycol is repaired in human cells via both the short patch and the FEN-1-requiring long patch BER pathways, ∼80 and ∼20% for each pathway, respectively (61). This supports our biochemical data suggesting that Rad2p may process AP lyase-cleaved AP sites in vivo. Due to the nature of the 5′-terminus following AP lyase cleavage of the AP site, it is perhaps not surprising that Rad2p efficiently degrades this structure. However, the environment of the nick contains not only a 5′-phosphoryl moiety but is flanked by an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde at the 3′-terminus. This shows the versatility of Rad2p for degrading intermediates that are generally considered to be short patch BER intermediates and which, to our knowledge, have not been previously demonstrated for any FEN-1 protein. The in vivo relevance of Rad2p processing of this cleavage product is unclear, but it demonstrates that it may be possible for such an activity to participate in this segment of BER in vivo. To date, the S.pombe BER pathway has not been extensively studied and additional genetic data may provide additional insights into the processing of these substrates in vivo.

FEN-1 proteins have been shown to process a variety of DNA substrates, therefore understanding how they function biochemically may lead to an increased understanding of the in vivo mechanisms of various cellular processes. One of the interesting observations from our work and that of other groups is the importance of the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of FEN-1 during DNA repair (40,55,58). The relative contributions of endo- versus exonuclease activity by FEN-1 may vary between species. Our results show that many factors can contribute to the extent of substrate processing by FEN-1. The differences in substrate specificity observed between FEN-1 proteins, such as those presented here for Rad2p, may be indicative of slight variations in the manner that FEN-1 proteins function in vivo. We have focused on several key characteristics of the DNA substrates that affect Rad2p activity, namely the nature of the 5′-terminus and the overall substrate structure. Decreased base pairing at DNA ends may be enhanced by the presence of base mispairs or a variety of non-base pairing lesions and could be further destabilized by a local sequence context promoting transiently single-stranded regions (resembling pseudo-Y structures). Such intermediates would be substrates for either the exonuclease or endonuclease activity of Rad2p. There is a precedent for the influence of secondary structure on FEN-1 activity, although in a capacity that differs from our results. The presence of base mispairs has been shown to influence FEN-1 flap endonuclease activity and G/C base pairs lead to pausing of the 5′→3′ exonuclease of Rth1 (52,62). These types of variables may play an important role in determining how effectively Rad2p, and possibly other FEN-1 proteins, are able to process various DNA structures in vivo.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the members of the Doetsch laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Research Grant CA73041.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lieber M.R. (1997) Bioessays, 19, 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donovan A. and Wood,R.D. (1993) Nature, 363, 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scherly D., Nouspikel,T., Corlet,J., Ucla,C., Bairoch,A. and Clarkson,S.G. (1993) Nature, 363, 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szankasi P. and Smith,G.R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem., 267, 3014–3023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tishkoff D.X., Boerger,A.L., Bertrand,P., Filosi,N., Gaida,G.M., Kane,M.F. and Kolodner,R.D. (1997) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7487–7492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tishkoff D.X., Amin,N.S., Viars,C.S., Arden,K.C. and Kolodner,R.D. (1998) Cancer Res., 58, 5027–5031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudolph C., Fleck,O. and Kohli,J. (1998) Curr. Genet., 34, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee B.I. and Wilson,D.M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 37763–37769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishimi Y., Claude,A., Bullock,P. and Hurwitz,J. (1988) J. Biol. Chem., 263, 19723–19733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulian M., Richards,S.H., Heard,C.J. and Bigsby,B.M. (1990) J. Biol. Chem., 265, 18461–18471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turchi J.J., Huang,L., Murante,R.S., Kim,Y. and Bambara,R.A. (1994) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 9803–9807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waga S., Bauer,G. and Stillman,B. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 10923–10934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrington J.J. and Lieber,M.R. (1994) EMBO J., 13, 1235–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyamichev V., Brow,M.A. and Dahlberg,J.E. (1993) Science, 260, 778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murante R.S., Huang,L., Turchi,J.J. and Bambara,R.A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 1191–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alleva J.L. and Doetsch,P.W. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 3645–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl T. (1971) Eur. J. Biochem., 18, 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konrad E.B. and Lehman,I.R. (1974) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 71, 2048–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahn R. and Patrick,M. (1976) In Wang,S. (ed.), Photochemistry and Photobiology of Nucleic Acids. Academic Press, New York, NY, pp. 97–145.

- 20.Witkin E.M. (1976) Bacteriol. Rev., 40, 869–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedberg E., Walker,G. and Siede,W. (1995) DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 22.Bowman K.K., Sidik,K., Smith,C.A., Taylor,J.S., Doetsch,P.W. and Freyer,G.A. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 3026–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yajima H., Takao,M., Yasuhira,S., Zhao,J.H., Ishii,C., Inoue,H. and Yasui,A. (1995) EMBO J., 14, 2393–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takao M., Yonemasu,R., Yamamoto,K. and Yasui,A. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1267–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avery A.M., Kaur,B., Taylor,J.S., Mello,J.A., Essigmann,J.M. and Doetsch,P.W. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2256–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanno S., Iwai,S., Takao,M. and Yasui,A. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 3096–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehmann A.R., Walicka,M., Griffiths,D.J., Murray,J.M., Watts,F.Z., McCready,S. and Carr,A.M. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 7067–7080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yonemasu R., McCready,S.J., Murray,J.M., Osman,F., Takao,M., Yamamoto,K., Lehmann,A.R. and Yasui,A. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 1553–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon J.H., Swiderski,P.M., Kaplan,B.E., Takao,M., Yasui,A., Shen,B. and Pfeifer,G.P. (1999) Biochemistry, 38, 4809–4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alleva J.L., Zuo,S., Hurwitz,J. and Doetsch,P.W. (2000) Biochemistry, 39, 2659–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reagan M.S., Pittenger,C., Siede,W. and Friedberg,E.C. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson R.E., Kovvali,G.K., Prakash,L. and Prakash,S. (1995) Science, 269, 238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tishkoff D.X., Filosi,N., Gaida,G.M. and Kolodner,R.D. (1997) Cell, 88, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freudenreich C.H., Kantrow,S.M. and Zakian,V.A. (1998) Science, 279, 853–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sommers C.H., Miller,E.J., Dujon,B., Prakash,S. and Prakash,L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 4193–4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klungland A. and Lindahl,T. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 3341–3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fortini P., Parlanti,E., Sidorkina,O.M., Laval,J. and Dogliotti,E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 15230–15236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price A. and Lindahl,T. (1991) Biochemistry, 30, 8631–8637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeMott M.S., Shen,B., Park,M.S., Bambara,R.A. and Zigman,S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem., 271, 30068–30076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim K., Biade,S. and Matsumoto,Y. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 8842–8848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X. and Wang,Z. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 956–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ausubel F.M., Brent,R., Kingston,R.E., Moore,D., Seidman,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (eds) (1997) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1. Phosphatases and Kinases. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

- 43.Tu C.P. and Cohen,S.N. (1980) Gene, 10, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaur B., Fraser,J.L., Freyer,G.A., Davey,S. and Doetsch,P.W. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 4703–4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pont-Kingdon G., Dawson,R.J. and Carroll,D. (1993) EMBO J., 12, 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray J.M., Tavassoli,M., al-Harithy,R., Sheldrick,K.S., Lehmann,A.R., Carr,A.M. and Watts,F.Z. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 4878–4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doetsch P.W. and Cunningham,R.P. (1990) Mutat. Res., 236, 173–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu X., Li,J., Li,X., Hsieh,C.L., Burgers,P.M. and Lieber,M.R. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 2036–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu J., Qian,Y., Frank,P., Wintersberger,U. and Shen,B. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8361–8371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sayers J.R. and Eckstein,F. (1990) J. Biol. Chem., 265, 18311–18317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murante R.S., Rust,L. and Bambara,R.A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 30377–30383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu F.X., Biswas,E.E. and Biswas,S.B. (1997) Biochemistry, 36, 5947–5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hosfield D.J., Frank,G., Weng,Y., Tainer,J.A. and Shen,B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 27154–27161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harrington J.J. and Lieber,M.R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 4503–4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gary R., Kim,K., Cornelius,H.L., Park,M.S. and Matsumoto,Y. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 4354–4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsumoto Y., Kim,K. and Bogenhagen,D.F. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 6187–6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frosina G., Fortini,P., Rossi,O., Carrozzino,F., Raspaglio,G., Cox,L.S., Lane,D.P., Abbondandolo,A. and Dogliotti,E. (1996) J. Biol. Chem., 271, 9573–9578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pascucci B., Stucki,M., Jonsson,Z.O., Dogliotti,E. and Hubscher,U. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33696–33702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dianov G. and Lindahl,T. (1994) Curr. Biol., 4, 1069–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z., Wu,X. and Friedberg,E.C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem., 272, 24064–24071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dianov G.L., Thybo,T., Dianova,I.I., Lipinski,L.J. and Bohr,V.A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem., 275, 11809–11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rumbaugh J.A., Henricksen,L.A., DeMott,M.S. and Bambara,R.A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 14602–14608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]