Abstract

In vertebrates, the mRNAs encoding ribosomal proteins, as well as other proteins implicated in translation, are characterized by a 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR), including a stretch of pyrimidines at the 5′-end. The 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine (5′-TOP) sequence, which is involved in the growth-dependent translational regulation characteristic of this class of genes (so-called TOP genes), has been shown to specifically bind the La protein in vitro, suggesting that La might be implicated in translational regulation in vivo. In order to substantiate this hypothesis, we have examined the effect of La on TOP mRNA translational control in both stable and transient transfection experiments. In particular we have constructed and analyzed three stably transfected Xenopus cell lines inducible for overexpression of wild-type La or of putative dominant negative mutated forms. Moreover, La-expressing plasmids have been transiently co-transfected together with a plasmid expressing a reporter TOP mRNA in a human cell line. Our results suggest that in vivo La protein plays a positive role in the translation of TOP mRNA. They also suggest that the function of La is to counteract translational repression exerted by a negative factor, possibly cellular nucleic acid binding protein (CNBP), which has been previously shown to bind the 5′-UTR downstream from the 5′-TOP sequence.

INTRODUCTION

About 20% of the mRNA of vertebrate cells includes a characteristic 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR), which is relatively short and starts with a sequence of 6–12 pyrimidines, the 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine (5′-TOP) sequence. Genes coding for mRNAs incorporating this 5′-TOP sequence, called TOP genes, include all the vertebrate genes for ribosomal proteins so far analyzed as well as other housekeeping genes directly or indirectly involved in the production and function of the translation apparatus (reviewed in 1,2). Moreover, in all cases studied TOP mRNAs have been found to be regulated at the translational level in a specific, growth-dependent manner. In actively growing cells TOP mRNAs are mostly localized on polysomes whereas in quiescent or growth-arrested cells they are mostly sequestered in inactive mRNPs.

It has been shown in several experimental systems that the 5′-UTR of these mRNAs, including the 5′-TOP sequence, is the cis-acting element responsible for regulation (3–6). However, a complete understanding of the mechanism of TOP mRNA translational control requires identification of the trans-acting factor(s) that specifically regulates TOP mRNA translation. Possible candidates for this factor have been identified by their ability to bind in vitro to the 5′-UTR of TOP mRNAs (7,8). In Xenopus two proteins have been shown to bind to the 5′-UTR of r-protein L4: the homolog of human La autoantigen (9) and the cellular nucleic acid binding protein (CNBP) (10). In particular, La protein has been shown to bind the 5′-TOP sequence only in the presence of a specific ribonucleoprotein factor. This factor, which is also necessary for the binding of CNBP to a downstream region of the 5′-UTR, includes the autoantigen Ro60 (11).

Although suggestive, the observation of an in vitro interaction between La protein and a target TOP RNA sequence does not automatically imply that the interactions also occur in vivo and that the protein has a functional role in the translational regulation of TOP mRNAs. Thus it is important at this point to study if and how La affects the translation of TOP mRNAs in vivo.

Here we have analyzed the function of La in vivo by stable and transient transfection experiments. Stably transfected Xenopus cell lines that overexpress wild-type or deleted forms of La have been analyzed, during both proliferation and growth arrest, for translational regulation of three TOP mRNAs (r-proteins L4 and S7 and translation factor EF-1α) and three non-TOP mRNAs (calmodulin, histone H3 and ferritin) as controls. In transient transfection experiments, using human HEK293 cells, we have co-transfected plasmids expressing: (i) wild-type La mRNA; (ii) Xenopus rp-L4 mRNA (distinguishable from the endogenous human rp-L4 mRNA); (iii) a non-TOP mRNA as an internal control. The results obtained show that La has a positive effect on translation of TOP mRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of expression plasmids

An aliquot of 6 fmol of a plasmid containing a full-length cDNA encoding Xenopus laevis LaB1 (12) was PCR amplified using: oligonucleotides 1 and 4 as primers, to generate the wild-type La coding sequence; oligonucleotides 1 and 3, to generate the deleted La1–194 coding sequence; oligonucleotides 2 and 4, to generate the deleted La93–427 coding sequence. Oligo 1, 5′-ACGGGATCCGCTGGAAAATGGGGA-3′; oligo 2, 5′-TCCGGATCCTTCATTCTTCTTTGCAA-3′; oligo 3, 5′-ACGGGATCCCCTGAATTAAATGAAGAT-3′; oligo 4, 5′-TCCGGATCCCTGTACCCCAACTTCAGT-3′.

The PCR products obtained were cloned into the BamHI sites of the prokaryotic expression vector pQE-9 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), for production of the recombinant proteins, and of the eukaryotic expression vector pUβG (13,14), to generate the plasmids pUβG-Lawt, pUβG-La1–194 and pUβG-La93–427.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

The pQE-9 vector (Qiagen), in which Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 were cloned, produces recombinant proteins carrying a histidine tag at the N-terminus (11). The recombinant proteins, expressed in the Escherichia coli host strain SG13009 upon induction by 2 mM IPTG, were highly purified, via the histidine tag, by affinity chromatography on Ni–NTA resin (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein quantitation was performed with a Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Cell culture

All Xenopus cell lines were grown at 24°C in medium containing 69% Leibovitz L-15, 10% fetal bovine serum, 21% H2O, supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. Cell line B3.2(tTA)1 was grown in the presence of 300 µg/ml G418 (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) and cell lines Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427 in the presence of 300 µg/ml G418 (Sigma Chemical Co.) and 500 µg/ml hygromycin B (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Addition of tetracycline, at a concentration of 2 µg/ml (Sigma Chemical Co.), was used to repress exogenous La protein expression. Resting cells were obtained by transfer into new dishes containing serum-free medium and by incubation for a further 4 h. Growing cells were obtained by transfer into new dishes containing complete medium for 4 h. After being transferred, into both serum-free and complete medium, cells reattached to the dish within 1 h.

Construction of stably transfected cell lines

The B3.2(tTA)1 cell line had been previously generated (13) by stable transfection of Xenopus kidney B3.2 cells (14) with a tetracycline-regulated transcription transactivator (tTA) gene (15). B3.2(tTA)1 cells have been used in stable co-transfection experiments, with DNA constructs expressing wild-type or truncated La (pUβG-Lawt, pUβG-La1–194 and pUβG-La93–427; see above) under the control of the tetracycline-sensitive promoter together with plasmid pSV2hygro encoding the hygromycin resistance gene. Cells, seeded in 100 mm dishes (2 × 106 cells/dish), were transfected by the standard DNA-calcium phosphate co-precipitation method (16). Transfected cell clones were isolated after a period of 4 weeks in the presence of 500 µg/ml hygromycin B. Total RNA was extracted from uninduced cells (grown in the presence of 2 µg/ml tetracycline) or after 72 h induction (without tetracycline) and analyzed by northern blot hybridization to evaluate the levels of expression of wild-type or truncated La mRNAs in each cell clone.

Transient transfections

Human HEK293 cells were co-transfected with the following constructs: (i) pXrp-L4, a plasmid containing the entire Xenopus rp-L4 gene, including the promoter and introns, in the pEMBL8 vector; (ii) pS16CM3-GH, a plasmid containing the promoter and 5′-UTR of mouse rp-S16 carrying a C→A mutation which inactivates the 5′-TOP sequence, followed by the growth hormone coding sequence (5); (iii) pUβglob-Lawt, expressing Xenopus wild-type La (see above). Control cells were co-transfected with constructs (i) and (ii) only. Transfection was carried out for 20 h in the presence of FuGENE (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the supplier’s instructions.

Polysome/RNP distribution of mRNAs

Procedures for cell lysis, sucrose gradient sedimentation of polysomes and analysis of the polysome/mRNP distribution of mRNAs are described elsewhere (17). Cells were lysed directly on the plate with 300 µl of lysis buffer [10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton-X100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 36 U/ml RNase inhibitor (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK), 1 mM dithiothreitol] and transferred to an Eppendorf tube. After 5 min incubation on ice with occasional vortexing, the lysate was centrifuged for 8 min at 10 000 r.p.m. at 4°C. The supernatant was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –70°C to be analyzed later or immediately sedimented in a 5–70% (w/v) sucrose gradient with low absorbance background (18). Fractions, collected while monitoring the optical density at 254 nm, were isopropanol precipitated overnight at –20°C. After centrifugation, RNA was extracted from the pellets and analyzed by northern blot.

DNA, RNA and protein analysis

Proteinase K/SDS extraction of DNA, agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blot hybridization, as well as the other basic laboratory procedures, were carried out according to laboratory manuals (19,20). Integration of the exogenous DNA constructs in the genome of the stably transfected cell lines was analyzed by standard procedures. Total RNA was extracted from whole cells, cytoplasmic extracts or from sucrose gradient fraction precipitates by the proteinase K method. For RNA analysis by northern hybridization, RNA was fractionated on formaldehyde–agarose gels and transferred to Gene Screen Plus membrane (NEN, Boston, MA); northern blot hybridizations were carried out essentially according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Radioactive probes were prepared by the random priming technique using as templates the inserts of plasmids containing Xenopus cDNAs for La protein (12), Xenopus r-proteins L4 (21) and S7 (22), Xenopus EF-1α (23) calmodulin (24) and ferritin (25) and a Xenopus genomic fragment for histone H3 (26). Hybridization filters were exposed to X-ray films and quantitatively analyzed with a phosphorimager.

Protein analysis was carried out on 12% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Protein quantitation was performed with a Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad). Western blots were performed as previously described (10), using a 1/2000 dilution of a La antiserum prepared by immunization of rabbits with recombinant Xenopus La protein (11). The filters were developed with an Alkaline Phosphatase Assay Kit (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitation of band intensities was carried out with NIH Image software.

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of plasmids encoding wild-type and truncated La forms

Due to a genome duplication event (27), the La gene, as with most other genes in the X.laevis genome, exists in two slightly divergent copies, LaA and LaB (12), the latter being the one used here for transfections. Since the La hybridization probe and La antibodies do not distinguish between the two copies, the mRNA (northern) and protein (western) analyses presented in this work refer to the overall amounts produced by the two gene copies.

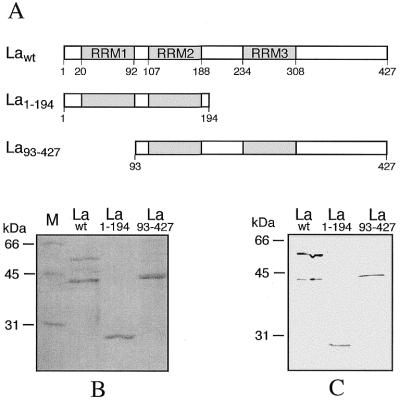

Figure 1A shows schematically the structure of Xenopus wild-type La (Lawt) with three putative RNA binding domains, RRM1, RRM2 and RRM3, in part identified by functional analysis and in part by sequence comparison with human La (11,12,28–30). The same Figure also shows the two truncated proteins, La1–194 and La93–427, that lack the RRM3 and RRM1 domains, respectively. The two deleted coding sequences, constructed as described in Materials and Methods, as well as the entire Lawt coding sequence, were cloned in the prokaryotic expression vector pQE9, for production of the recombinant proteins, and in the eukaryotic expression vector pUβG, for use in the experiments described in the following sections. All constructs were sequenced to check for correct promoters, UTRs, coding regions and translation initiation and termination codons. The recombinant La proteins were initially analyzed by PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 1B) or by western blotting using an La antiserum (Fig. 1C). It appears that the recombinant Lawt yields two bands: the expected full size band of ∼57 kDa and a band of ∼45 kDa. It is well known that in mammals the La protein is very sensitive to endogenous proteases, shorter forms arising from proteolytic cleavage at the C-terminus of the protein during purification, even in the presence of protease inhibitors (31–33). Furthermore, in Xenopus the protein has an additional putative protease susceptibility region in the C-terminus (12), accounting for the presence of the 45 kDa cleavage product (9). This cleaved form maintains the RNA binding properties of full-length La, as it still contains the portion of the molecule implicated in the interaction with the target RNA. All this has been extensively described and discussed in previous papers (9,11). Figure 1B shows that the two truncated proteins, La1–194 and La93–427, have the sizes expected on the basis of the N- and C-terminal deletions, respectively. La1–194 maintains the capacity to bind the target RNA, while La93–427 does not (9; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Xenopus La protein and deletions used in this work. (A) Schematic representation of wild-type La (Lawt) and of the two truncated proteins La1–194 and La93–427; the positions of the three putative RNA binding domains RRM1, RRM2 and RRM3 are shown. (B) Coomassie blue staining of 1 µg of purified recombinant Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 after SDS–12% PAGE. M, molecular weight markers. (C) Western blot analysis, with La antiserum, of 100 ng of purified recombinant Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 after SDS–12% PAGE.

The western blot presented in Figure 1B, and other similar ones, provides further relevant information. In fact, it appears that in comparison with the entire Lawt, the cleaved 45 kDa protein and the two deleted forms La1–194 and La93–427 are less reactive to La antiserum. Quantitation of band intensities and correction for the molar quantities of the four proteins show that the relative affinities of the antibodies for the four protein forms (Lawt 56 kDa, Lawt 45 kDa cleavage product, La93–427 and La1–194) are approximately 1, 0.2, 0.25 and 0.1. These values were used to calculate the amounts of the various La forms in the transfected cell lines (see below).

Construction and characterization of stably transfected cell lines overexpressing wild-type and truncated La

Since alterations of a basic function such as the regulation of ribosome synthesis could be lethal for cell survival we employed the tetracycline-regulated expression system (15), which allows for transfection and screening of cell lines under uninduced conditions. Starting from the parental X.laevis B3.2 kidney cell line (14), we previously constructed and characterized the B3.2(tTA)1 cell line stably transfected for production of the tetracycline-regulated transcription transactivator (tTA) (13). We have now used the B3.2(tTA)1 cell line in a second round of stable transfection with constructs containing the Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 sequences cloned in the pUβG vector (13) under control of the tetracycline-sensitive promoter. Several cell clones were obtained for each transfection and were analyzed for expression of the transfected La sequence. Clones showing the highest expression levels when induced and the lowest when uninduced were chosen for further analysis (see Materials and Methods).

Expression of La sequences in transfected cell lines

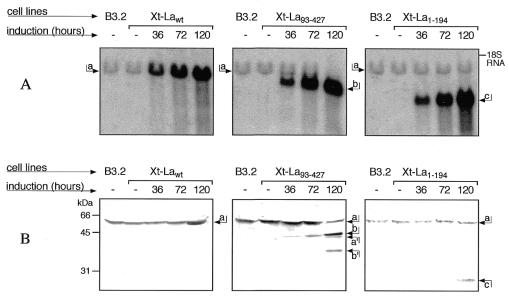

Three selected cell lines, Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427, were characterized in more detail for integration and expression of the transfected La sequences, at the DNA, RNA and protein levels. Southern analysis (data not shown) indicated that, in the three cell lines, between 20 and 40 copies of the transfected plasmids had been integrated, mostly as tandem repeats that maintain the original structure as determined by restriction analysis. Northern analysis of total RNA and western analysis of protein extracts from S100 supernatants were performed at time intervals after induction by removal of tetracycline from the medium (Fig. 2). In all three cell lines, accumulation of the mRNAs transcribed from the transfected genes is already high after 3 days induction and, during the next 2 days it increases to ∼20-fold with respect to the endogenous mRNA. The sizes of these mRNAs are the expected ones, with the Lawt construct mRNA co-migrating with the endogenous La mRNA, while in the case of the deleted genes the exogenous mRNAs migrate proportionally faster.

Figure 2.

Expression induction of Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 in the three Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427 cell lines. Aliquots of 10 µg total RNA and 100 µg cytoplasmic S100 extracts from the parental B3.2 cell line and from the three transfected cell lines, uninduced or after increasing induction time, were analyzed respectively by northern blot hybridization with a Xenopus La cDNA probe (A) and by immunoblotting with La antiserum (B). In (A) arrows a–c indicate the bands corresponding, to the mRNAs for Lawt, La93–427 and La1–194, respectively. In (B) arrows a–c indicate, respectively, the bands corresponding to the proteins Lawt, La93–427 and La1–194 and arrows a′ and b′ indicate the bands corresponding to the cleaved forms of Lawt and La93–427.

The western blot analysis shown in Figure 2B indicates that in the Xt-La93–427 and Xt-La1–194 transfected cells there is an accumulation of truncated proteins of the expected sizes. In the case of Xt-Lawt the desired increase in the amount of Lawt was also obtained, although in this case the increased amount of Lawt could not be unequivocally attributed to the transfected gene, rather than to increased activity of the endogenous genes. The amounts of exogenous proteins accumulated in the cytoplasm, with respect to endogenous La, appear to be lower than expected based on the mRNA analysis. Quantitation of the western blots shown in Figure 2B, and of other similar ones, followed by correction for differential antibody affinities (see above), indicates that: (i) Xt-Lawt cells express ∼3-fold higher levels of La with respect to parental cells; (ii) in Xt-La1–194 cells, the C-terminally truncated La1–194 is expressed at 10 times molar excess with respect to the normal protein, whose amount remains unchanged; (iii) in Xt-La93–427 cells, the N-terminally truncated La93–427 is expressed at 4- to 5-fold excess with respect to the endogenous normal protein, whose levels are correspondingly reduced. This reduction was accompanied by the appearance of the 45 kDa cleaved form, derived from the endogenous full-length La, and of a 35 kDa form compatible with cleavage of La93–427 at the same C-terminal site. These observations, reproducible in different experiments, suggest that a feedback regulation might exist which limits overexpression of La and that La1–194 has lost this regulatory property.

Effect of overexpression of wild-type and deleted La on translation of TOP and non-TOP mRNAs

To study the in vivo effect of wild-type and truncated La overexpression on growth-dependent translational regulation of TOP genes, we analyzed the polysome/mRNP distribution of TOP and control mRNAs in transfected cell lines. After induction of expression of exogenous wild-type or truncated La forms, the cells were grown in the absence (resting cells) or presence (growing cells) of 10% serum in the culture medium, as described in Materials and Methods. To analyze the polysome/mRNA distribution of mRNAs, cytoplasmic extracts were prepared and fractionated through sucrose gradients (see Materials and Methods). Ten fractions were collected from each gradient while recording the absorbance profile. The RNA extracted from the gradient fractions was then analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and northern blot hybridization with probes for control and TOP mRNAs. Quantitation of the radioactive signals in the polysomal and non-polysomal regions of the gradients were then used to evaluate the percentage of a given mRNA associated with the polysomes.

As controls we used: (i) for each cell line, the same cells grown under uninduced conditions (presence of tetracycline); (ii) for all cell lines, the parental cells not transfected with La constructs grown under the same conditions as the experimental samples (absence of tetracycline). In preliminary experiments no appreciable differences were observed in the polysome/mRNP distribution of TOP and control mRNAs among the parental B3.2 cells, the tTA-expressing B3.2(tTA.1) cells and the three transfected cell lines, Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427, grown under uninduced conditions (data not shown). Also, the presence or absence of tetracycline per se did not change the translation pattern and regulation of TOP and non-TOP mRNAs. Thus, in the following experiments the B3.2 parental cell line was used as a single control to which all three transfected cell lines grown under induced conditions could be compared.

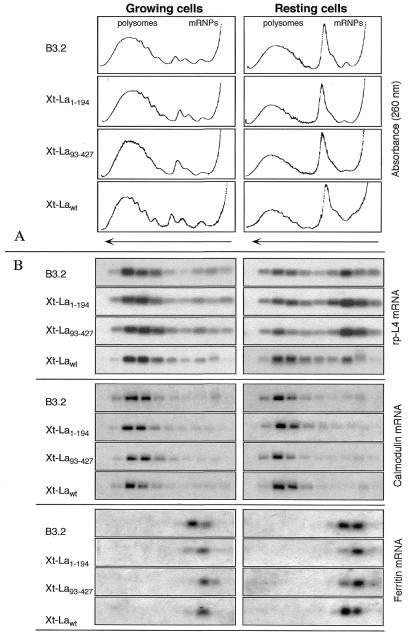

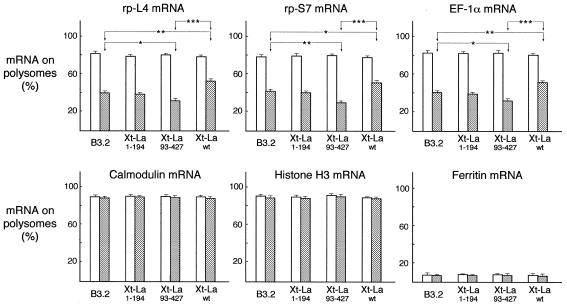

After 120 h induction, Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427 cells were plated and grown for a further 4 h in the absence (resting cells) or presence (growing cells) of 10% serum. The polysome/RNP distribution of various mRNAs was then analyzed. In parallel, control parental B3.2 cells were also grown and analyzed under the same conditions. Figure 3 shows the results obtained in a typical experiment. The absorbance profiles of the gradients show that, as already known, more ribosomes are associated with polysomes in cells grown in the presence of 10% serum compared with serum-starved cells. The polysomal (absorbance) profiles obtained for the four cell lines do not show significant differences, indicating that the transgenes do not induce gross changes in metabolism. Figure 3B shows the polysome/mRNP distribution, analyzed by northern blot hybridization of gradient fractions, of rp-L4 mRNA in the control B3.2 cells and in the Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427 cell lines. Quantification and statistical analysis of the results obtained in several independent experiments are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that control cells present the characteristic behavior of growth-dependent translational regulation, with most rp-L4 mRNA on polysomes under growth conditions, while only ∼40% of it was associated with polysomes under resting conditions. Overexpression of the truncated La1–194 did not show any significant effect on polysome association of rp-L4 mRNA, under both growing and resting conditions, whereas overexpression of the other truncated form La93–427 and of the normal Lawt had appreciable effects on resting cells. In comparison with the parental cell line, translation of rp-L4 mRNA was significantly more repressed in La93–427-expressing cells and less repressed in cells overexpressing wild-type La. This difference was highly significant in the case of a La93–427/Lawt comparison. The polysome/mRNP distribution has been similarly analyzed for two other TOP mRNAs (rp-S7 and EF-1α) and for three non-TOP mRNAs (calmodulin, histone H3 and ferritin). In the absence of iron addition to the medium, this last mRNA was expected to be translationally repressed under both conditions. As an example, two representative controls are shown in Figure 3: the constitutively translated calmodulin mRNA (Fig. 3C) and the translationally repressed ferritin mRNA (Fig. 3D). Quantification and statistical analysis of the results obtained in several independent experiments for these are shown in Figure 4. This shows that rp-S7 and EF-1α mRNAs both behave similarly to rp-L4 mRNA. In comparison with the parental cell line, translation of these mRNAs was more repressed in resting Xt-La93–427 cells, while it was less repressed in resting Xt-Lawt cells. Hybridizations with probes for the non-TOP calmodulin and histone H3 mRNAs indicate that in all four cell lines their translation remains efficient under both growing and resting conditions. In contrast, hybridization with the ferritin mRNA probe showed that translation of this mRNA remained repressed in the three transfected cell lines, as it was in the parental cells.

Figure 3.

Polysome/mRNP distribution of TOP and non-TOP mRNAs in control and in Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 overexpressing cells, under growing and resting conditions: a typical experiment. (A) Absorbance profiles of sucrose gradients of cytoplasmic extracts prepared from B3.2 cells and from Xt-Lawt, Xt-La1–194 and Xt-La93–427 cells after 120 h induction, in the growing and resting conditions. (B) Northern blot analysis of the RNAs extracted from the above sucrose gradients. Hybridizations with probes for rp-L4, calmodulin and ferritin are shown.

Figure 4.

Polysome/mRNP distribution of TOP and non-TOP mRNAs in control and in Lawt, La1–194 and La93–427 overexpressing cells, under growing and resting conditions: a quantitative analysis. Experiments like the one shown in Figure 3 were repeated seven times. Gradient fractions were analyzed by northern hybridization with probes for three TOP mRNAs (rp-L4, rp-L7 and EF-1α) and three non-TOP mRNAs (calmodulin, ferritin and histone H3) and the hybridization filters analyzed with a phosphorimager for quantitative data. The percentages of three TOP mRNAs (rp-L4, rp-S7 and EF-1α) and three non-TOP mRNAs (calmodulin, ferritin and histone H3) on polysomes, in the growing (open bars) and resting (gray bars) conditions, are given. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 7 for rp-L4, rp-L7, calmodulin and ferritin mRNAs and n = 5 for EF-1α and histone H3 mRNAs, as these two were not analyzed in the first two experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 and ***P < 0.0001 (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test).

Effect of La overexpression in transiently transfected cells

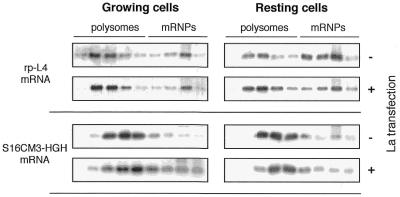

In order to confirm our findings, we utilized a transient transfection system. In this case Xenopus La was expressed by transient transfection in HEK293 human cells, exploiting the fact that translational regulation of TOP mRNAs is highly conserved in vertebrates (6). Since transfection efficiency is low, it is not possible to analyze the effect of La overexpression on endogenous cellular mRNA derived from the entire cell population. For this reason we co-transfected the following plasmids: (i) pUβG-Lawt, expressing Xenopus La; (ii) pXrp-L4, a construct expressing a typical TOP mRNA, Xenopus rp-L4 mRNA, which can be distinguished from the endogenous human L4-mRNA by hybridization with a probe spanning the divergent 3′-portion of the sequence; (iii) pS16CM3-GH, which expresses a well-characterized non-TOP mRNA whose association with polysomes is not affected by the growth conditions (5). This non-TOP control is, as a matter of fact, a TOP mRNA in which the CCUUUUC 5′-TOP sequence has been mutated to ACUUUUC, a mutation that completely abolishes translational repression. Since our rp-L4 mRNA also starts at the 5′-end with the same 5′-TOP sequence (CCUUUUC), the two mRNA TOP sequences, wild-type and mutated, can be compared after co-transfection of the two plasmids in the same cells. After 20 h transfection, cells were divided onto two plates and grown in the absence of serum for 2 h. One plate was then lysed (resting condition), while the other was incubated for a further 2 h in the presence of serum and then lysed (growing condition). Cytoplasmic extracts were controlled for exogenous La expression (data not shown) and analyzed for polysome association of mRNAs as described above. The results presented in Figure 5 show that in resting cells La overexpression had a clear positive effect on translation of exogenous rp-L4 mRNA with a wild-type 5′-TOP sequence. In fact, ∼60% of the Xenopus rp-L4 mRNA was on polysomes in La-overexpressing cells, compared with 40% in control cells. As expected, the non-TOP S16CM3-GH mRNA was mostly loaded on polysomes in all conditions.

Figure 5.

Polysome/mRNP distribution of a TOP (rp-L4) mRNA and a non-TOP (S16CM3-GH) mRNA in growing and resting cells, in the presence or absence of overexpressed La. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with plamsids pXrp-L4 and pS16CM3-GH, with or without pUβG-Lawt. After transfection, cells were incubated under growing or resting conditions (see text), then lysed and analyzed as in the experiment described in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

The La protein is an evolutionarily conserved, ubiquitous, abundant protein, mostly associated with various cellular RNAs (for references see 33). Several functions have been assigned to this protein, both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. In the nucleus, La is found associated with newly synthesized RNA polymerase (pol) III transcripts and it has been implicated in the termination and initiation of transcription by this polymerase (34–39), in tRNA processing (40,41) and in transport and nuclear retention of some pol III transcripts (42–44). La also binds to other cellular small nuclear RNAs and to some viral RNAs (45–47). The common feature characterizing all these La binding RNAs is the presence of a stretch of pyrimidines, particularly of uridines. In the cytoplasm, La has been mostly implicated in functions connected with translation. The best documented and most studied role in the cytoplasm is in the translational initiation of certain viral RNAs (48–51). Since, in general, viruses parasitize cellular functions, it is reasonable to suppose that La might also play a role in the translation of cellular mRNAs. Accordingly, it has been observed that: (i) La renders in vitro translation dependent on 5′ capping of the mRNA (52); (ii) it might play a role in translation initiation, as it interacts in vitro with the translation start site (53); (iii) in vitro it has a stabilizing effect on histone mRNAs (54); (iv) it associates with a subset of small ribosomal subunits, possibly by direct association with 18S rRNA (55); (v) it can rescue protein synthesis in the reticulocyte lysate system from inhibition by low concentrations of dsRNA (56); (vi) in vitro La interacts with the terminal pyrimidine sequence present in the 5′-UTR of rpL4 and other r-protein mRNAs, which is responsible for their growth-dependent translational regulation. This suggests that La might represent an element implicated in this regulation of TOP mRNAs (9,10). Unfortunately this, as well as all other proposed cytoplasmic La functions, are based on in vitro experiments, leaving open to question the real functional role(s) of the La cytoplasmic fraction in vivo.

To address the question of the proposed role of La in the translational regulation of TOP mRNAs, we have now constructed and analyzed cell lines that overexpress wild-type La or deleted forms that might exert a dominant negative effect. The results obtained indicate that, in serum-starved cells, overexpression of normal Lawt increases the loading of TOP mRNAs on polysomes. In contrast, expression of La93–427 results in a further repression of TOP mRNA translation. The observed differences appear rather modest but are statistically significant. Moreover, the positive effect of La on TOP mRNA translation has been confirmed by transient transfection experiments, in which we have co-transfected plasmids coding for La overexpression and for TOP and non-TOP reporter mRNAs.

Considering that translation regulation is responsible, at the most, for a 2- to 3-fold change in the percentage of TOP mRNA associated with polysomes (from 25–35 to 70–80%), the limited magnitude of the La effect observed in our experiments may be expected. In fact we should consider that: (i) La is a relatively abundant protein and this might pose a limit on the effect of exogenous La overexpression; (ii) this overall regulation might depend on different regulatory effectors which allow the cell to respond to various external stimuli, such as nutrients and specific growth and mitogenic signals, etc., and to internal signals connecting protein synthesis levels with developmental and cell differentiation requirements, energy supply from mitochondria, etc. Thus, each of these multiple effectors, of which La may be only one, is expected to have quite a limited effect per se. Interestingly, a similar situation has been described for regulation at the transcriptional level of genes of this same class. The study of r-protein gene promoters has revealed the presence of several different cis-acting sequences, interacting with different binding factors, each of which is not individually necessary for transcription and has, in any case, a slight effect (57).

The negative effect of La93–427 cannot be explained by direct competition between the two La forms for the target RNA, since La93–427 does not bind RNA. Indeed, the most reasonable explanation is the observed reduction in the amount of endogenous normal La in cells expressing the truncated La93–427. However, one cannot exclude competition between Lawt and La93–427 for interaction with some element, other than the target RNA sequence, involved in regulation, as for instance the Ro60-related factor (11). The other deleted La form, La1–194, appears not to have appreciable effects on the translation of TOP mRNAs, although it maintains the binding capacity to the 5′-TOP sequence in vitro. Interestingly, an analogous deleted La form has been shown to be able to bind the La target site in poliovirus RNA but was unable to stimulate translation in vitro (58). Moreover, in contrast to La93–427, La1–194 overexpression does not cause a reduction in the amount of endogenous Lawt. This observation, together with a possible lower affinity in vivo for the TOP sequence, might explain the inability of La1–194 to exert a dominant negative effect.

The finding that La has a positive effect on the translation of TOP mRNA in vivo is consistent with a previously proposed model based on the analysis of in vitro interactions of La and CNBP proteins with the TOP-containing 5′-UTR of rp-L4 mRNA (11). According to the model, the 5′-UTR can be found in two alternative conformations: (i) a closed structure, in which the 5′-TOP sequence is base paired in the stem of a hairpin loop stabilized by binding with a CNBP dimer, which results in translation repression; (ii) an open conformation, in which the secondary structure of the 5′-UTR is disrupted by binding of La to the 5′-TOP sequence, which results in translation activation. In fact, it was shown that La and CNBP interactions with the TOP-containing 5′-UTR, both of which are assisted by the same Ro60-related factor, are mutually exclusive. The model proposed that CNBP is a translational repressor, while La would exert its positive effect on translation by competing CNBP binding. The observation of an in vivo positive effect of La on the translation of TOP mRNAs in growth-arrested cells but not in growth-stimulated cells is in line with the hypothesis that the effect is not exerted directly, but by counteraction of the negative effect of CNBP. The opposite effects of La and CNBP may not necessarily reflect direct competition for binding to the 5′-UTR of TOP mRNAs, but may imply competition for some other element involved in regulation, the Ro60-related factor being a possible candidate. It has been proposed that La protein, and also other cytoplasmic RNA binding proteins, might have a general role in cap-dependent translation initiation (52). This does not exclude the possibility that La plays a role in specific translational regulation of TOP mRNAs, assuming that the specificity of regulation resides in CNBP binding, rather than in La binding to the 5′-UTR of TOP mRNAs.

It should be emphasized that this model for growth-dependent translational regulation of TOP mRNA is, at this stage, an unavoidable oversimplification that does not exclude the contribution of additional elements. For instance, a negative effect of the hnRNP E1 on in vitro translation of TOP mRNAs has been observed (O.Meyuhas, personal communication). Moreover, a specific effect on translation regulation of TOP mRNAs by the phosphorylated state of r-protein S6 in the small ribosomal subunit is strongly suggested by several studies on p70S6K (59–61). Thus, TOP mRNA translation regulation is connected, through the FRAP/p70S6K signal transduction pathway, to the incoming signals controlling cell growth and proliferation.

We observed that our cell lines, even after several days of expression of an excess of wild-type or deleted La, appear normal. This suggests that La may play a role in the fine tuning of regulation important in the development and viability of the organism, but is not essential for cell growth. A connection can be seen between some of the different roles assigned to La protein. Thus, the positive roles of La in TOP mRNA translational regulation and in transcription and/or processing of pol III transcripts may together constitute a mechanism for coordinating the production of the protein components and of the small RNA components (5S RNA and tRNAs) of the translation apparatus. As with the involvement of La in the translation of several viral RNAs, this might be direct exploitation of a basic cellular function by the viruses, whose peculiar internal translation initiation depends on the binding of La to a pyrimidine sequence shortly upstream of the initiation AUG codon.

The stably transfected cell lines should prove useful tools for studying in vivo the other possible roles ascribed to this protein on the basis of in vitro experiments.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Nicolas S. Foulkes for critical review of the manuscript, Marcello Giorgi and Nadia Campioni for expert technical assistance and Oded Meyuhas for providing plasmid pS16CM3-GH. This work was supported by grants from the EC (BIO4-CT95-0045), CNR (Programma Biotecnologie L. 95/95 and Biotecnology Target Project) and MURST (PRIN project).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaldi F. and Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. (1997) In Jeanteur,P. (ed.), Cytoplasmic Fate of Eukaryotic mRNA. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 1–17.

- 2.Meyuhas O., Avni,D. and Shama,S. (1996) In Hershey,J.W.B., Mathews,M.B. and Sonenberg,N. (eds), Translational Control. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 363–388.

- 3.Mariottini P. and Amaldi,F. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 816–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond M.L., Merrick,W. and Bowman,L.H. (1991) Genes Dev., 5, 1723–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy S., Avni,D., Hariharan,N., Perry,R.P. and Meyuhas,O. (1991) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 3319–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avni D., Shama,S., Loreni,F. and Meyuhas,O. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 3822–3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardinali B., Di Cristina,M. and Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. (1993) Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 2301–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaspar R.L., Kakegava,T., Cranston,H., Morris,D.R. and White,M.W. (1992) J. Biol. Chem., 267, 508–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellizzoni L., Cardinali,B., Lin-Marq,N., Mercanti,D. and Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. (1996) J. Mol. Biol., 259, 904–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellizzoni L., Lotti,F., Maras,B. and Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. (1997) J. Mol. Biol., 267, 264–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellizzoni L., Lotti,F., Rutjes,S.A. and Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. (1998) J. Mol. Biol., 281, 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherly D., Stutz,F., Lin-Marq,N. and Clarkson,S.G. (1993) J. Mol. Biol., 231, 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camacho-Vanegas O., Mannucci,L. and Amaldi,F. (1997) In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol., 34, 14–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seiler-Tuyns A., Mérillat,A.-M., Harfligger,D.N. and Wahli,W. (1988) Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 8291–8305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gossen M. and Bujard,H. (1992) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 5547–5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wigler M., Sweet,E., Sim,G.K., Wold,B., Pellicer,A., Lacy,E., Maniatis,T., Silverstein,S. and Axel,R. (1979) Cell, 17, 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyuhas O., Bibrerman,Y., Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. and Amaldi,F. (1996) In Krieg,P.A. (ed.), A Laboratory Guide to RNA: Isolation, Analysis and Synthesis. Wiley-Liss, New York, NY, pp. 65–81.

- 18.Camacho-Vanegas O., Loreni,F. and Amaldi,F. (1995) Anal. Biochem., 228, 172–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 20.Krieg P.A. (1996) A Laboratory Guide to RNA: Isolation, Analysis and Synthesis. Wiley-Liss, New York, NY.

- 21.Loreni F., Ruberti,I., Bozzoni,I., Pierandrei-Amaldi,P. and Amaldi,F. (1985) EMBO J., 4, 3483–3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariottini P., Bagni,C., Francesconi,A., Cecconi,F., Serra,M.J., Chen,Q.-M., Loreni,F., Annesi,F. and Amaldi,F. (1993) Gene, 132, 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krieg P.A., Varnum,S., Wormington,M. and Melton,D.A. (1989) Dev. Biol., 133, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien Y. and Dawid,I.B. (198) Mol. Cell. Biol., 4, 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moskaitis J.E., Pastori,R.L. and Shoenberg,D.R. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruberti I., Fragapane,P., Pierandrei-Amaldi,P., Beccari,E., Amaldi,F. and Bozzoni,I. (1982) Nucleic Acids Res., 10, 7543–7559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bisbee C.A., Baker,M.A., Wilson,A.C., Hadji-Azimi,I. and Fishberg,M. (1977) Science, 195, 785–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birney E., Kumar,S. and Krainer,A.R. (1993) Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 5803–5816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodier J.L., Fan,H. and Maraia,R.J. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5823–5832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenan D.J. (1995) PhD thesis, Duke University, Raleigh, NC.

- 31.Habets W.J., den Brok,J.H., Boerbooms,M.T., van de Putte,L.B.A. and van Venrooij,W.J. (1983) EMBO J., 2, 1625–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan E.K., Sullivan,K.F. and Tan,E.M. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 2233–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Venrooij W., Slobbe,R.L. and Pruijn,G.J.M. (1993) Mol. Biol. Rep., 18, 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefano J.E. (1984) Cell, 36, 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gottilieb E. and Steitz,J.A. (1989) EMBO J., 8, 851–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottilieb E. and Steitz,J.A. (1989) EMBO J., 8, 841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maraia R.J., Kenan,D.J. and Keene,J.D. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 2147–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maraia R.J. (1996) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 3383–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan H., Sakulich,A.L., Goodier,J.L., Zhang,X., Qin,J. and Maraia,R.J. (1997) Cell, 88, 707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoo C.J. and Wolin,S.L. (1997) Cell, 89, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin-Marq N. and Clarkson,S.G. (1998) EMBO J., 17, 2033–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boelens W.C., Palacios,I. and Mattaj,I.W. (1995) RNA, 1, 273–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simons F.H.M., Rutjes,S.A., van Venrooij,W.J. and Pruijn,G.J.M. (1996) RNA, 2, 264–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimm C., Lund,E. and Dahlberg,J.E. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lerner M.R., Andrews,N.C., Miller,G. and Steitz,J.A. (1981) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 78, 805–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francoeur A.M. and Mathews,M.B. (1982) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 6772–6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madore S.J., Wieben,E.D. and Pederson,T. (1984) J. Biol. Chem., 259, 1929–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali N. and Siddiqui,A. (1997) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 2249–2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang Y.N., Kenan,D.J., Keene,J.D., Gastignol,A. and Jeang,K.T. (1994) J. Virol., 68, 7008–7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meerovitch K., Svitkin,Y.V., Lee,H.S., Lejbkowicz,F., Kenan,D.J., Chan,E.K., Agol,V.I., Keene,J.D. and Sonenberg,N. (1993) J. Virol., 67, 3798–3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Svitkin Y.V., Pause,A. and Sonenberg,N. (1994) J. Virol., 68, 7001–7007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svitkin Y.V., Ovchinnikov,L.P., Dreyfuss,G. and Sonenberg,N. (1996) EMBO J., 15, 7147–7155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McBratney S. and Sarnow,P. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3523–3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLaren R.S., Caruccio,N. and Ross,J. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 3028–3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peek R., Pruijn,G.J. and Van Venrooij,W.J. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem., 236, 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James M.C., Jeffrey,I.W., Pruijn,G.J., Thijssen,J.P. and Clemens,M.J. (1999) Eur. J. Biochem., 266, 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sáfrány G. and Perry,R.P. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem., 230, 1066–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Craig A.W.B., Svitkin,Y.V., Lee,H.S., Belsham,G.J. and Sonenberg,N. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jefferies H.B., Reinhard,C., Kozma,S.C. and Thomas,G. (1994) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 4441–4445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terada N., Patel,H.R., Takase,K., Kohno,K., Nairn,A.C. and Gelfand,E.W. (1994) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 11477–11481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jefferies H.B., Fumagalli,S., Dennis,P.B., Reinhard,C., Pearson,R.B. and Thomas,G. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 3693–3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]