Abstract

Here, we report a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assay as a novel way to investigate the binding of unlabeled ligands to the human transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (hTRPML1), a lysosomal ion channel involved in several genetic diseases and cancer progression. This novel BRET assay can be used to determine equilibrium and kinetic binding parameters of unlabeled compounds to hTRPML1 using intact human-derived cells, thus complementing the information obtained using functional assays based on ion channel activation. We expect this new BRET assay to expedite the identification and optimization of cell-permeable ligands that interact with hTRPML1 within the physiologically relevant environment of lysosomes.

Keywords: membrane protein, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, transient receptor potential channels, calcium channel, lysosome

The human transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (hTRPML1) is a member of the transient receptor potential mucolipin (TRPML) subfamily of lipid-gated ion channels that control the flux of calcium (Ca2+), and potentially other cations, from the lumen of endosomes and lysosomes to the cytosol (1, 2). TRPML1 is ubiquitously expressed in human tissues and plays a major role in lysosomal storage, trafficking, and pH homeostasis (3, 4). Its dysfunction is associated with various pathologies, including mucolipidosis type IV (5), tumor progression (6), and increased susceptibility to Helicobacter pillory infections (7). TRPMLs are activated by phosphoinositides such as PI(3,5)P2 (8, 9) and are repressed by sphingomyelins and PI(4,5)P2 (10). To explore TRPML1 modulation as a therapeutic strategy, several groups have sought to identify synthetic small-molecule ligands for this channel, such as the agonists ML-SA1 and the antagonists ML-SI1 and ML-SI3 (5, 11).

Nevertheless, current methods to identify and optimize TRPML1 ligands favor compounds having poor cell permeability (7, 11). TRPML1 ligands identified to date bind to a pocket deeply embedded within the lysosomal membrane and are formed by the interface of three transmembrane helices (12). Thus, to reach this binding site, ligands must not only permeate the cell membrane but also traverse the cytoplasm to reach the lysosomal membrane. However, to increase assay sensitivity, TRPML1 ligands are commonly identified using a truncated version of the ion channel lacking both N- and C-terminal lysosomal-targeting motifs. This truncated TRPML1 (TRPML1ΔNC) abnormally localizes to the cell membrane, allowing Ca2+ influx to the cytosol because of channel activation to be more easily monitored (1, 13). Thus, agonists and antagonists of TRPML1ΔNC identified using these assays are often only weakly active toward the full-length lysosomal ion channel, most likely because of their poor cell permeability.

To overcome some of these drawbacks, novel whole-cell assays have been developed that use genetically engineered Ca2+ indicators, such as GCaMP (14), fused to full-length TRPML1 to monitor the influx of Ca2+ from the endosome to the cytoplasm (15). GCaMP is a modular Ca2+-sensing synthetic protein comprised of a GFP, the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin (CaM), and a peptide sequence from myosin light-chain kinase (M13). Upon activation of GCaMP-fused full-length TRPML1, the Ca2+ released from the lysosome complexes with the CaM domain of the sensor protein. This facilitates the interaction of the CaM domain with the M13 peptide in GCaMP, which leads to a shift in GFP’s protonation state, and to the emission of fluorescence at a specific wavelength (16, 17). Using GCaMP-fused full-length TRPML1, channel agonists with whole-cell activity have been successfully found (18, 19, 20).

Calcium indicators can readily report on channel activation but are less suited to assess the details of ligand binding to the receptor. For example, despite recent progress, CaM-based Ca2+ sensors have slow on- and off-rates leading to a fluorescence raise and decay with limited temporal resolution (21). Thus, methods that can assess equilibrium and kinetic parameters of ligand binding independently of channel activation can be used to better understand ligand binding and complement the information obtained from Ca2+ sensor assays. For example, channel activation–independent assays would be useful in estimating the on-target residence time of ligands, which is relevant when prioritizing ligands with similar binding constants (22, 23, 24).

In-cell, target engagement assays based on bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) have been successfully used to study binding equilibrium and kinetics of unmodified ligands to several different protein classes. In these assays, the BRET donor is often a luminescent version of the target protein fused to nanoLuc (nLuc), a small (19 kDa) engineered luciferase. A fluorescent version of a known ligand acts as a BRET acceptor. Interaction between BRET donor and acceptor in cells results in BRET, whereas unmodified ligands that can competitively disrupt the interaction between donor and acceptor reduce the BRET signal (25, 26). Thus, BRET-based target engagement assays can be used to establish both equilibrium and kinetic binding parameters of unmodified ligands (27, 28). Another advantage of BRET-based methods is that they are ratiometric and less sensitive to assay differences because of changes in the expression levels of the nLuc-fused target, for example (25, 29).

Here, we describe a novel BRET-based assay to directly detect ligand binding to lysosome-localized full-length hTRPML1 independent of channel activation. We used this assay to establish equilibrium and kinetics binding parameters for ML-SA1 (5) and compound 31 (11) (here named 8), two best-in-class literature compounds previously shown to modulate the channel. We also collected channel activation data for both ligands using a GCaMP6-based Ca2+ assay. We expect a better characterization of ligand binding to the full-length lysosomal hTRPML1 to expedite the discovery of novel small-molecule modulators to explore the cellular roles of this channel in both normal and disease biology.

Results

Design strategies for BRET acceptor and donor

BRET-based target engagement assays require the generation of a matched pair of custom-made BRET donor and acceptor. Here, the BRET donor consisted of hTRPML1 fused to nLuc (30), whereas the BRET acceptor (also referred to as a probe or tracer) was a fluorescent version of ML-SA1 (1), a known binder of TRPML1 (Fig. 1, A–C) (5).

Figure 1.

Design strategies for the hTRPML1 BRET donor and acceptor.A, schematic representation of nLuc (cyan surface, Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 5IBO) fused to the C terminus of hTRPML1 (protein—gray surface, 1—cyan spheres, PDB ID: 5WJ9). hTRPML1 N and C termini are at the cytosolic face, and the full-length protein forms homotetramers. The black straight lines represent the linker used to connect nLuc to the hTRPML1. B, chemical structures of 1 (ML-SA1) and the BRET probe, MRC087. The BODIPY moiety is highlighted in red. C, in silico docking of MRC087 (pale red sticks) to hTRPML1 based on the cryo-EM structure of hTRPML1 bound to 1 (blue sticks; PDB ID: 5WJ9). BRET, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer; hTRPML1, human transient receptor potential mucolipin 1; nLuc, nanoLuc.

To generate a BRET donor for our assay, we engineered a luminescent version of full-length hTRPML1 having the nLuc luciferase fused to the C-terminus of the ion channel via a short (nine amino acid residues) and flexible linker (hereafter denominated hTRPML1-nLuc) (Fig. 1A). In hTRPML1, both N- and C-termini are cytosolic (12, 31), thus, we expected the nLuc domain of the fusion protein to also localize to the cytosol.

To develop a BRET tracer for TRPML1, we employed compound 1 as a scaffold and EverFluor 590 SE as a fluorophore. EverFluor 590 SE is a BODIPY-based cell-penetrant fluorophore with spectral properties compatible with those of nLuc (32). Compound 1 is often used to evaluate TRPML1 function in live cells (6), organoids (7), and animals (33), and its binding mode to hTRPML1 was determined by cryo-EM (31, 34). Furthermore, there is a wealth of available data on the structure–activity relationship of 1 and its analogs (35). Using these data, we sought to turn 1 into a BRET fluorescent probe (MRC087), by attaching the fluorophore to the compound 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline core. In silico molecular docking suggested that this design strategy would not result in significant steric clashes with TRPML1 transmembrane helices that make up the ion channel–binding pocket (Fig. 1C). Our in silico docking results also indicated that attachment of the fluorophore at this position would preserve the interactions between 1 and the ion channel’s transmembrane pocket, as seen in the cryo-EM structure for the complex (34), and direct the fluorophore moiety toward the bottom of the pocket and to the cytosolic face of the ion channel (Fig. 1B).

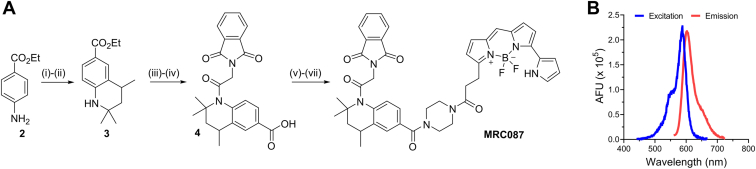

Synthesis of a fluorescent version of ML-SA1—BRET tracer MRC087

Following the design strategy delineated previously, we produced a fluorescent derivative of 1, MRC087, according to the synthetic route described in Figure 2A. The Skraup reaction of ethyl 4-aminobenzoate 2 with acetone (35), followed by palladium on carbon catalytic reduction led to the desired 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline core 3. The N-alkylation and removal of the ester-protection group in basic conditions gave the desired intermediate 4. Steglich reaction of 4 with boc-piperazine under standard conditions, followed by removal of the boc-protection group and N-alkylation of the piperazine linker, led to the target compound MRC087. Compound MRC087 was prepared in seven synthetic steps with an overall yield of 1.5%. The final compound displayed robust emission of fluorescence at the expected wavelengths for EverFluor 590 SE, with an emission maximum of ∼620 nm (Fig. 2B), which indicated MRC087 to be suitable as a BRET acceptor compatible with nLuc.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of MRC087 and its spectral properties.A, reagents and conditions: (i) acetone, p-TsOH, cyclohexane, 140 °C MW, 45 min (13%). (ii) Pd/C, H2, EtOAc, RT, 24 h (96%). (iii) Phthalylglycyl chloride, DMAP, pyridine, toluene, 140 °C MW, 1.5 h (71%). (iv) NaOH, EtOH, H2O, RT, 3 h (99%). (v) N1-Boc-piperazine, EDC, DMAP, DCM, RT, 16 h (36%). (vi) TFA, DCM, RT, 3 h (82%). (vii) EverFluor-SE, DIPEA, DMF, RT, 16 h, dark (58%). B, fluorescence spectra of MRC087 in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (excitation, blue line; emission, red line). DCM, dichloromethane; DIPEA, N,N-diisopropylethylamine; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine; DMF, N,N′-dimethylformamide; RT, room temperature.

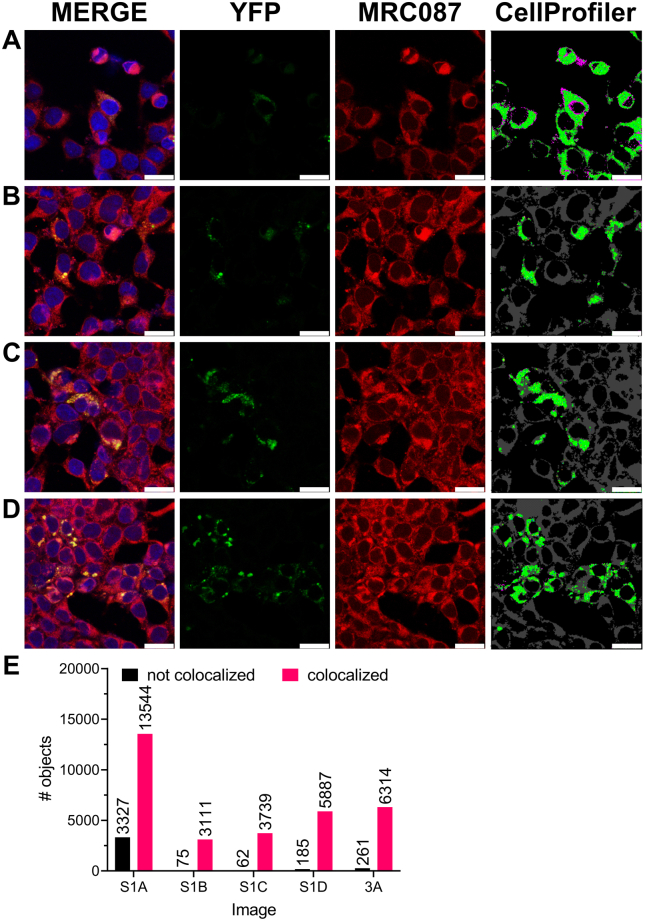

Tracer MRC087 colocalizes with hTRPML1 in cells

To ascertain that MRC087 permeated cells, we followed the tracer accumulation in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293)–derived cells ectopically expressing a fluorescent version of full-length hTRPML1 fused to YFP (Figs 3 and S1; Video S1). For that, we took advantage of MRC087 bright red fluorescence by exciting the fluorophore using the microscope laser set at an appropriate wavelength (543 nm) and visualizing cells under the microscope. The resulting fluorescence microscopy images indicated MRC087 permeated cells and accumulated mostly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A, top left panel). Our results also suggested that MRC087 was unable to accumulate in the cell nucleus, marked with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in Figure 3A (bottom left panel).

Figure 3.

Confocal imaging of MRC087 in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells.A, addition of MRC087 (1.0 μM) to HEK293T cells transiently expressing hTRPML1 fused to the YFP (hTRPML1-YFP). Magnification = 40×; white bar = 50 μm. B, further magnification (100×) of the region indicated in (A). White bar = 75 μm. C, colocalization analysis of YFP and the red emitting fluorescent probe MRC087 using CellProfiler. Data shown are mean + SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05. Images in (A and B) were acquired using a Leica TCS SP5 II camera. hTRPML1, human transient receptor potential mucolipin 1.

Next, we used the intrinsic fluorescence of YFP-fused hTRPML1 to localize the ion channel to discrete regions within the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A, bottom left panel). Merging the fluorescent signals from MRC087 and YFP-fused hTRPML1 suggested that the tracer colocalized with the ion channel (Figs. 3A, bottom right panel; Fig. 3, B and C and S1; Video S1). Importantly, this fluorescent version of hTRPML1 was previously shown to accumulate within lysosomes (36). Thus, taken together, our results indicated MRC087 permeated cells and accumulated in the same organelles where hTRPML1 localized to in human-derived cells.

Characterization of the in-cell interaction between MRC087 and nLuc-fused hTRPML1

Before performing in-cell BRET assays using tracer MRC087, we confirmed that ectopic expression of hTRPML1-nLuc in HEK293T cells resulted in robust emission of light at the expected wavelength (450 nm, Fig. 4A), confirming our BRET donor design strategy and demonstrating that the fusion protein retained the ability of nLuc to produce blue light in the presence of its substrate furimazine (Fig. 4B, blue circles).

Figure 4.

Characterization of an in-cell BRET-based target engagement assay for hTRPML1.A, luminescence spectra of human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells transiently expressing hTRPML1-nLuc (blue line). B, raw luminescence (450 nm, blue circles, left axis) and fluorescence (620 nm, red circles, right axis) signals from HEK293T cells expressing hTRPML1-nLuc at increasing concentrations of MRC087. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 3 or 4/concentration) of three independent experiments. C, total, specific, and nonspecific binding (white, red, and black circles, respectively) of MRC087 in HEK293T cells transiently expressing hTRPML1-nLuc. The reported Kd value was obtained by nonlinear fitting of experimental data points, shown as mean ± SD (n = 3 or 4/concentration) of three independent experiments. D, raw BRET signals (in milliBRET units—mBU) from HEK293T cells expressing hTRPML1-nLuc in the absence (blue circles) or the presence (red circles) of MRC087 (2.0 μM). The data (n = 20/treatment) were used to estimate the assay Z′-factor (indicated). E, association kinetics of MRC087 to the hTRPML1-nLuc in HEK293T cells. MRC087 concentrations used were 1.3 and 0.67 μM (blue and red circles, respectively). The reported kinetic parameters for MRC087 were obtained by a nonlinear fitting of experimental data points, shown as mean ± SD (n = 3 or 4/concentration) of two independent experiments. BRET, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer; hTRPML1, human transient receptor potential mucolipin 1; nLuc, nanoLuc.

Next, to ascertain energy transfer between our pair of BRET donor and acceptor, we titrated MRC087 to HEK293T cells expressing hTRPML1-nLuc. We observed a robust emission of red fluorescence (Fig. 4B, red circles), indicative of the energy transfer between our BRET acceptor and donor in cells. Similar results have been obtained for other BRET acceptor and donor pairs based on EverFluor 590 SE and nLuc, respectively (25). As it is often used in the literature, here we reported the BRET signal in milliBRET units, defined as the ratio between the emission signals obtained for the donor (450 nm) and acceptor (620 nm) channels multiplied by 1000.

More importantly, tracer titration onto cells resulted in a typical saturation binding curve (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the presence of saturating concentrations (60 μM) of a known nonfluorescent hTRPML1 ligand (compound 8, Fig. 5) (11) almost completely abolished the BRET signal (Fig. 4C, filled-in black circles). These results indicated that the BRET signal observed was due to the specific interaction between the tracer and target in cells and that this interaction followed a simple bimolecular reaction mechanism. We also estimated the Z′-factor for the assay (0.8, Fig. 4D) and found it to be above the threshold for a high-quality assay (Z′-factor ≥0.5). The Z′-factor is a statistical parameter used to evaluate assay quality and is particularly sensitive to data variability (37). Using the tracer titration data, we estimated an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.8 ± 0.3 μM (Fig. 4C) for the interaction between hTRPML1-nLuc and MRC087 in HEK293T cells.

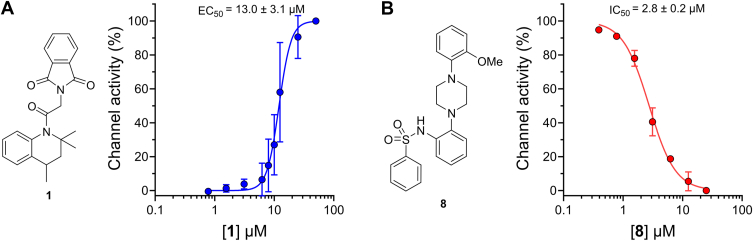

Figure 5.

Channel activation in HEK293T cells measured by a Ca2+indicator.A and B, dose–response curve of 1 (A) and 8 (B) in HEK293T cells transiently expressing GCaMP6f-hTRPML1. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 6/concentration) of three (A) or two (B) independent experiments. EC50 and IC50 values indicated were obtained by a nonlinear fitting of experimental data points. The structures of 1 and 8 are indicated. HEK293T, human embryonic kidney 293T cell.

In competitive binding assays, the on-target residence time of the tracer is also an important property (38). We thus followed the binding kinetics of MRC087 to hTRPML1-nLuc in HEK293T cells (Fig. 4E). We performed these experiments using two concentrations of the tracer (1.3 and 0.67 μM) and a saturating concentration of compound 8 (60 μM) to prevent MRC087 from rebinding to hTRPML1-nLuc. The collected data allowed us to estimate binding association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants for the tracer-target interaction in cells of 24.5 ± 1.5 × 104 M−1 min−1 and 0.2 ± 0.1 min−1, respectively. The on-and-off rates of MRC087 were consistent with those reported previously for other tracers used in BRET-based target engagement assays (38). These values were also used to calculate a dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.8 ± 0.4 μM, which was in excellent agreement with the one found previously from equilibrium binding experiments (0.8 ± 0.3 μM; Fig. 4C).

Together, our results so far indicated the BRET-based target engagement assay we developed here is both sensitive and robust, making it a useful tool to evaluate the equilibrium and kinetics binding parameters of unmodified compounds to hTRPML1 in intact cells.

Assessment of ligand binding to lysosomal TRPML1 using BRET

Having characterized the interactions between the BRET tracer and nLuc-fused target in cells, we next sought to use our BRET-based assay to investigate the binding of unmodified compounds to hTRPML1 in cells. For that, we used ML-SA1 (compound 1) and compound 8. ML-SA1 is an hTRPML1 agonist, whereas compound 8 functions as an antagonist to this ion channel (11). Both compounds were synthesized in-house (see Supporting information for further details), following the methodology reported in the literature (11, 35).

Before we used compounds 1 and 8 in our BRET-based assay, we confirmed their activities on hTRPML1 using HEK293T cells transiently expressing a version of the ion channel fused to the Ca2+ indicator, GCaMP6f (18, 19, 20). As expected, titration of 1 led to a dose-dependent increase in fluorescence indicative of channel activation (Fig. 5A). We used these data to calculate an EC50 of 13.0 ± 3.1 μM for the activation of hTRPML1 by compound 1. To calculate the antagonist potency of 8, cells were incubated for 10 min with various concentrations of the compound before the addition of agonist 1 at a saturating concentration (25 μM). The resulting data confirmed 8 as a potent antagonist of hTRPML1 activity (IC50 = 2.8 ± 0.2 μM, Fig. 5B). These results confirmed the activity of compounds 1 and 8 prepared in-house and were on par with those found in previous studies (EC50 = 9.7 for 1 and IC50 = 1.8 μM for 8) (11, 12).

To demonstrate our BRET-based target engagement assay could be used to determine binding affinities of unmodified compounds to hTRPML1 in human cells, we performed competition-binding experiments using 1 and 8. Titration of increasing amounts of 1 or 8 to HEK293T cells expressing hTRPML1-nLuc and a fixed concentration of tracer MRC087 (2.0 μM) led to a dose-dependent decrease in the observed BRET signal. These data allowed us to estimate an apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (KdA) of 19.8 ± 1.8 μM and 2.8 ± 1.2 μM for compounds 1 and 8, respectively (Fig. 6, A and B). These values were in excellent agreement with those we obtained using the Ca2+ indicator assay (13.0 ± 3.1 μM and 2.8 ± 0.2 μM, for 1 and 8, respectively).

Figure 6.

Determination of equilibrium and kinetics binding parameters of unlabeled compounds to hTRPML1-nLuc in human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells using a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)–based assay.A and B, representative curves of saturation-competitive displacement of MRC087 (2.0 μM) by compounds 1 (A) and 8 (B). Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 3 or 4/concentration) of three independent experiments. The reported KdA were obtained using Cheng–Prusoff formalism. C and D, kinetics of competitive binding of 1 (C) and 8 (D) in the presence of MRC087 (2.0 μM) to HEK293T cells expressing hTRPML1-nLuc. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 6/concentration) of a single experiment. hTRPML1, human transient receptor potential mucolipin 1; nLuc, nanoLuc.

A drawback of genetically engineered Ca2+ indicators is that they lack temporal resolution to establish a ligand’s on-and-off rates to the receptor. Thus, we used our BRET assay to assess the binding kinetic parameters for compounds 1 and 8 to hTRPML1. For that, we challenged cells with varying concentrations of these compounds in the presence of a fixed concentration of the MRC087 tracer (2.0 μM) and followed the increase in the BRET signal over time (Fig. 6, C and D). Fitting the acquired data to Motulsky–Mahan’s competitive binding model allowed us to estimate kon and koff values for both compounds (39). For compound 1, we estimated kon and koff values of 1.7 × 104 M−1 min−1 and 0.65 min−1, respectively. For compound 8, these values were 64.1 × 104 M−1 min−1 and 0.67 min−1. These results indicated that the ∼10-fold difference in binding potency between the two compounds is likely because of the faster association rate constant of 8 compared with that of 1. On the other hand, our results indicated that both compounds have similar dissociation rate constants and, consequently, residence times (τ = 1.5 min, defined as the reverse of koff). Somewhat surprisingly, binding constants calculated using the kinetic parameters obtained from these experiments (37.3 and 1.0 μM for compounds 1 and 8, respectively) were slightly (approximately twofold to threefold) different from those obtained from binding experiments under equilibrium conditions (19.8 and 2.8 μM for compounds 1 and 8, respectively). Taken together, our results demonstrated the ability of our BRET-based assay to estimate kinetic binding parameters for unlabeled ligands to hTRPML1 in live cells.

Discussion

Currently, there is a paucity of methods to investigate the binding of unlabeled ligands to intracellular membrane proteins. For Ca2+ channels, most ligand-binding assays rely on monitoring channel activity, often with fluorescent Ca2+ sensors. These methods make it challenging to determine ligand binding kinetics, such as kon and koff, and to differentiate binding events from channel activation. Using a novel, in-cell, BRET-based target engagement assay, we have determined the equilibrium and binding kinetic parameters of agonist and antagonist compounds to the human lysosomal Ca2+ channel TRPML1 in intact cells.

Understanding binding kinetics can lead to the generation of more efficient ligands and, as has been suggested, efficacious drugs (22, 23, 24, 40, 41, 42). Historically, radioligand assays on isolated membranes have been used to investigate the binding kinetics of ligands to ion channels in the cell membrane context. More recently, surface plasmon resonance–based methods have been used to characterize the binding kinetics of unmodified compounds to purified receptors embedded within lipid bilayers (43). The BRET-based method developed here is unique in its ability to readily determine on and off rates of unlabeled ligands to the human lysosomal ion channel TRPML1 in live intact cells. Although these parameters have never been estimated for hTRPML1 ligands, the kon and koff values we obtained for ML-SA1 and compound 8 using the BRET assay in intact cells were on par with those previously reported for ligands of purified G-protein–coupled receptors embedded within a lipid bilayer obtained by surface plasmon resonance or radioligand assays (44). We expect the unique capabilities of our BRET method to aid in the optimization of novel hTRPML ligands having robust pharmacological activities.

Despite the relevance of binding kinetics for ligand optimization, compound binding affinities are more often obtained under equilibrium conditions, as these are more amenable to simpler experimental setups. Using our BRET-based method in competitive binding experiments under equilibrium conditions, we estimated binding affinities for hTRPML1 ligands that were in excellent agreement (<1.5-fold difference) with those we and others obtained using Ca2+ sensors (11, 12). Intriguingly, we did find slightly larger discrepancies (twofold to threefold) when we calculated ligand binding affinities of unmodified compounds to hTRPML1 using the kinetic parameters obtained from time-course experiments. On the other hand, binding affinities for the fluorescent tracer MRC087 calculated from equilibrium and kinetic experiments were in excellent agreement with each other. Discrepancies between kinetics and equilibrium binding constants are often associated with unexpected conformational changes during binding events (42). In fact, TRPML family members are known to undergo large conformational changes during channel opening and closing (12, 34, 40, 45). Furthermore, agonist and antagonist lipids are known to allosterically regulate ligand binding to hTRPML1 (31). Thus, the differences in the values of binding affinities of unmodified compounds found from equilibrium and kinetic experiments using our BRET assay may reflect some of these phenomena.

As for other competitive binding assays based on tracer displacement, the BRET-based target engagement assay we developed here may not be appropriate to investigate ligands that do not bind to the same TRPML1 transmembrane pocket targeted by ML-SA1. These ligands may fail to displace MRC087, which would lead to false-negative results or the generation of “atypical” dose–response curves. Orthogonal assays, such as the one we employed here based on channel activation, could be used to identify and characterize these ligands. Nevertheless, it is important to note that, to date, the vast majority of rationally designed TRPML1 modulators are presumed to bind to the same TRPML1 transmembrane pocket targeted by ML-SA1 and the MRC087 tracer. Thus, we expect our BRET-based assay to be useful in establishing equilibrium and kinetic binding properties for known and novel modulators targeting TRPML1 transmembrane pocket.

Kinetics and equilibrium binding parameters for hTRPML1 determined using the BRET-based assay developed here were likely to reflect binding to the physiologically relevant and lysosome-localized form of the ion channel. Full-length hTRPML1 has N- and C-termini targeting motifs that localize the channel to late endosomes and lysosomes (36, 46). Previous studies have demonstrated that genetically engineered fluorescent versions of hTRPML1 having larger fluorescent tags, such as YFP (∼26 kDa), and calcium indicators, such as GCaMP (∼50 kDa), fused to the ion channel C-terminus retained both the function and the lysosomal localization of the wildtype protein (36, 46, 47). Our competition binding data also suggested that fusing TRPML1 to nLuc did not severely impact ligand binding to the ion channel, as similar potencies were found for reference compounds ML-SA1 and 8 using the BRET-based assay described here and two different functional assays that monitor channel activation using either Ca2+ indicators or patch clamping. Nevertheless, it is also important to note that, although our BRET-based assay can assess ligand binding to TRPML1 in cells, it may not be well suited for mechanistic studies investigating how ligand binding lead to ion channel activation. For these studies, functional assays that detect channel activation are likely more appropriate.

Finally, the properties of the BRET-based assay developed here compared favorably with those reported in the literature or available through commercial sources (38, 39). Tracer MRC087 binding affinity to hTRPML1 is in the low micromolar range, on par with the most potent ligands for this ion channel (48). Interestingly, the tracer binding affinity to hTRPML1 was 20-fold higher than the one observed for its precursor ML-SA1, likely because of the tracer having a BODIPY-based fluorophore, which, when lacking hydrophilic groups, are known to permeate cells and accumulate within intracellular membranes (49). Nevertheless, despite this increased affinity for the receptor within lysosomal membranes, the tracer could be readily displaced by competing unmodified hTRPML1 ligands. Importantly, for intracellular targets, such as TRPML1, commercial and custom-made tracers for BRET-based assays must be cell permeable to ensure that fluorescent signal is derived from on-target binding. Imaging of MRC087 tracer clearly demonstrated its ability to cross the plasma membrane and stain cytoplasmic organelles, including lysosomes labeled with TRPML1-YFP. Besides, in the BRET assay, the recorded fluorescence only comes from the nLuc excitation of the BODIPY fluorophore in close proximity to the target (<10 nm) (50, 51).

In conclusion, we reported here the development of a new assay to estimate equilibrium and kinetics binding parameters for ligands interacting with the transmembrane binding pocket of the lysosomal ion channel hTRPML1. We expect this new BRET assay to expedite the discovery and development of novel compounds to further investigate the biology of this ion channel and to explore the therapeutic potential of hTRPML1 modulators. In addition, the development of similar BRET-based assays for other transmembrane intracellular proteins may lead to a better understanding of the physical–chemical properties needed for compounds to engage these targets in their physiologically relevant cell compartments.

Experimental procedures

Cloning

Full-length hTRPML1 was cloned in frame with nLuc in plasmid pFC32K (Promega). The coding sequence for hTRPML1 was PCR amplified from Addgene plasmid #18826 (hTRPML1 fused to YFP in pcDNA3.1 plasmid) (52) using primers hTRPML1-fb003 (5′GGCTGCGATCGCCATGACAGCCCCGGCGGGTCC) and hTRPML1-rb003 (5′ATGGGTTTAAACATTCACCAGCAGCGAATGCTCCTCCG). The sequence of the resulting clone was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

In silico docking

The cryo-EM structure of hTRPML1 bound to ML-SA1 (compound 1) (Protein Data Bank ID; 5WJ9) was prepared for docking using Maestro (version 12.9.137; Schrödinger 2021-3). The ligand was modified to contain the linker and BODIPY at the desired position in the aromatic ring of the 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline core. After the construction of the 2D structure, the 3D structure was generated using Schrödinger’s LigPrep tool. The docking was performed at standard precision (SD) using default values. The final complexes were energy minimized using the “Refine Protein–Ligand Complex” tool available in the Schrödinger Prime module (restricted to protein atoms within a 5.0 Å radius of ligand atoms). The final minimized model was analyzed by visual inspection using Schrödinger’s PyMOL (version 2.5.2).

Cell cultures and transfections

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (1% penicillin and streptomycin), at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Before transfection, cells were washed with PBS at 37 °C and treated with trypsin. Cell density was adjusted using DMEM to obtain the desired number of cells per well (see later). Transfection mixture (10-fold concentrated and pre-equilibrated at room temperature for 15 min) was added to cells. About 100 μl of this mixture was dispensed into the wells of a 96-well plate. The 10-fold transfection mixture consisted of the appropriate plasmid DNA and the transfecting agent (FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent; Promega Corp; catalog no.: E2311) in Opti-MEM serum-free without phenol red (Gibco; catalog no.: 11058021) in the following ratio: 200 ng of plasmid DNA to 600 nl of FuGENE in a final volume of 10 μl.

Confocal imaging

HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum with 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were washed, trypsinized, and counted in DMEM. About 2 × 105 cells were seeded into poly-l-lysine-treated coverslips (Knittel Glass; catalog no.: 100013) and transfected with 200 ng of DNA (hTRPML1-YFP) and 0.3 μl of FuGENE HD. Cells were used 48 h post-transfection. On the day of the experiment, the medium was removed and the cells were treated with 400 μl/well of Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium, no phenol red (Gibco; catalog no.: 11058021) with MRC087 (final concentration of 1.0 μM) and incubated in the dark at 37 °C, under 5% CO2, for 30 min. Cells were then fixed with 4% v/v of paraformaldehyde/PBS for 20 min and washed with PBS. After this, slides were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen; catalog no.: P10144) into an inverted fluorescent microscope for analysis. The cells were imaged with 40× or 100× objectives plus 3.5× zoom, using a confocal fluorescent inverted microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II). The images were collected using an imaging software (LAS X v. 2.7.3.9723, Leica Microsystem GmbH, Germany).

Colocalization analysis

Colocalization of YFP/MRC087 was measured by calculating the correlation between the intensities of green and red channels on a pixel-by-pixel basis across an entire image, as described before (53, 54). CellProfiler (version 4.2.1) (www.cellprofiler.org) was used to calculate the colocalization (Manders coefficient) between the pixel intensities of five images (shown in the Supporting information).

In-cell BRET assays

BRET assays were performed as described previously (28, 29). Briefly, following transfection with the plasmid encoding hTRPML1-nLuc, HEK293T cells (2 × 105 cells/100 μl) were dispensed into a 96-well white plate (Greiner Bio-One; catalog no.: 655098) and allowed to grow for 48 h. The medium was then removed, cells were washed with PBS (prewarmed to 37 °C), and 85 μl of Opti-MEM was added to each well. For fluorescent probe dose–response curves, 5 μl of serially diluted MRC087 (at 20× final assay concentration, the highest assay concentration used was 4 μM) were added to cells. Probe dilutions were prepared in tracer dilution buffer (TDB; 32.2% PEG400, 12.5 mM Hepes [pH 7.5]) from (50 mM) stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The final volume on each well was brought to 100 μl by the addition of 10 μl of Opti-MEM containing 8 (60 μM, in 10% DMSO) or 10 μl of Opti-MEM (containing 10% DMSO). For competitive binding experiments using nonfluorescent ML-SA1, MRC087 was prepared as aforementioned, and 5 μl of MRC087 in TDB was added to 85 μl of cells for a final assay concentration of 2.0 μM. Test compounds (50 or 10 mM in DMSO) were serially diluted first in DMSO (to 20× final assay concentration) and then in Opti-MEM (to 10× final assay concentration), and 10 μl of each dilution was added per well. For all in-cell BRET assays, the final DMSO concentration was 1%. Cells were incubated for 2 h before adding a mixture containing nLuc substrate and inhibitor (Promega; catalog no.: N2162) diluted in Opti-MEM. Light emissions at 460 + 10 nm (BRET donor) and at 610 + 20 nm (BRET acceptor) were sequentially recorded (integration time = 0.5 s, gain = 3600) using a luminometer (BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar). Raw BRET values were calculated by dividing the acceptor fluorescence (620 nm) by the donor luminescence (450 nm) signals. These are reported as milli-BRET (mBRET) units (mBU), according to Equation 1:

| (1) |

BRET values were converted to blank-corrected normalized BRET (%) according to Equation 2:

| (2) |

where X = mBRET value in the presence of the test compound and the probe, Y = mBRET value in the presence of probe only, and Z = mBRET value in the absence of probe and test compound.

To determine apparent dissociation constants from saturation binding curves, BRET values in the presence of DMSO (total binding) or in the presence of saturating concentration of 8 (nonspecific) were plotted as a function of probe concentration, and values for probe equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) were determined using the hyperbolic dose–response equation (Equation 3) for binding to a single site available in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc):

| (3) |

where Bmax is maximum specific binding extrapolated to very high probe concentrations, NS is the slope of nonspecific binding, and background is the value in the absence of probe.

To determine test compound concentration that yielded a half-maximal response (EC50), normalized BRET (%) values were plotted as a function of test compound concentration, and the data were fitted to the sigmoidal dose–response equation (Equation 4) available in GraphPad Prism:

| (4) |

where x is the test compound concentration. Obtained EC50 values were converted to inhibitor binding constants (KdA) using the Cheng–Prusoff formalism, according to Equation 5 available in GraphPad Prism:

| (5) |

where [Probe] is the final concentration of BRET probe in the assay and Kd the probe equilibrium dissociation constant to the nLuc-fused target.

In-cell BRET kinetic assays

To assess kon and koff of the probe, the medium was removed, and cells were washed with Opti-MEM (prewarmed to 37 °C, and 85 μl of Opti-MEM was added to each well). Then, cells were treated with 50 μl of the mixture containing nLuc substrate and nLuc extracellular inhibitor (Promega; catalog no.: N2162) diluted in Opti-MEM. Next, 10 μl of a 10× solution of compound 8 (60 μM, in 10% DMSO) or Opti-MEM (containing 10% DMSO) were added to the test wells. The plate was gently shaken for 5 min, and then it was analyzed for baseline BRET for 1 min. After the baseline, 5 μl of serially diluted MRC087 (at 20× final assay concentration, the highest assay concentration used was 4 μM) were added to cells. Probe dilutions were prepared in TDB (32.2% PEG400, 12.5 mM Hepes [pH 7.5]) from (10 mM) stock solutions in DMSO.

Light emissions at 460 ± 10 nm (BRET donor) and at 610 ± 20 nm (BRET acceptor) were sequentially recorded (integration time = 0.5 s, gain = 3600) using a luminometer. Readings were collected at 15 s intervals. Raw BRET values were calculated by calculating the ratio between acceptor and donor signals. These were reported as mBU, according to Equation 1.

The nonspecific binding at each probe concentration at every time point was removed from the total binding to calculate the probe-specific binding. These values were plotted as a function of time, and values for probe kinetic association and dissociation constants (kon and koff) were determined using the hyperbolic dose–response equation (Equation 6) for association kinetics for two or more ligand concentrations available in GraphPad Prism:

| (6) |

where L is test compound concentration in molar, X is time in minutes, and Bmax is maximum specific binding.

To assess the residence time of compounds, the same protocol described for kinetic BRET of the probe was applied, with small changes (39). On the day of the assay, a mixture of the unlabeled compound plus MRC087 was prepared, preserving following the final concentrations: 22.2 and 66.7 μM (1); 3.3 and 10 μM (8); and 2.0 μM (MRC087). As a control of MRC087 binding, a solution without unlabeled compounds was prepared, by using only DMSO vehicle.

The cells were washed with Opti-MEM (prewarmed to 37 °C), and 85 μl of Opti-MEM was added to each well. Then, cells were treated with 50 μl of the mixture containing nLuc substrate and inhibitor (Promega; catalog no.: N2162) diluted in Opti-MEM. The plate was gently shaken for 5 min, and then it was analyzed for baseline BRET for 1 min. After the baseline, the plate reader injects 15 μl of the previously prepared solutions to the test wells. To determine the nonspecific binding, a control containing 60 μM of 8 was used.

The nonspecific binding at each probe concentration at every time point was removed from the total binding to generate the specific binding. These values were plotted as a function of time, and values for compound kon and koff were determined using the hyperbolic dose–response equation from MotulskyMahan model [7] for kinetics of competitive binding available in GraphPad Prism:

| (7) |

Where [L] and [I] = concentrations of probe and unlabeled ligand in nM, respectively, t is the time in minutes, and Bmax is the maximum specific binding, kon is denoted by k1 or k3 and the koff by k2 or k4 for probe or unlabeled ligand, respectively. For the kinetics of competitive binding, it is necessary to separately obtain k1 and k2 to calculate the binding constants of unlabeled ligands.

Calcium imaging

Calcium imaging assays were performed as described previously (19). Briefly, following transfection with the plasmid encoding GCaMP6f-hTRPML1, HEK293T cells (4 × 105 cells/100 μl) were dispensed into a poly-d-lysine-coated 96-well black plate (Corning; catalog no.: 3603) and allowed to grow for 24 h. After 24 h of transfection, the medium was removed, the cells were washed with 100 μl of PBS, and 100 μl of DMEM without phenol red (Gibco; catalog no.: 21063029) was added to each well. The cells were allowed to grow for another 24 h. On the next day, the plate was removed from the incubator and was equilibrated for 10 min at room temperature. For the agonist assay, 10 μl of the medium was removed from the cells, and then the plate was placed in the plate reader for a brief incubation (10 min) at 25 °C After this time, the experiment was initiated by reading the fluorescence every 5 s for 1 min, which comprises the baseline. Following the baseline establishment, 10 μl of a 10× solution of agonist 1 (in 2.5% DMSO) were automatically added to the wells. Readings were recorded for an additional 6 min. Automatic injections used the plate reader built-in pumps, with a speed of 300 μl/s and the “smart dispensing” feature. The fluorophore was excited at 480 ± 25 nm, and emissions were read at 549 to 562 nm using a CLARIOstar. Each well was analyzed at 5 s intervals with 20 flashes per well, for about 7 min. We applied orbital averaging with a diameter of 3 mm to acquire the fluorescent data.

For the antagonist assay, 20 μl of the medium was removed from the cells, then 10 μl of the test compound 8 (10×, in 2.5% DMSO) was added. The plate was placed in the plate reader for a brief incubation (10 min) at RT. Then, the experiment is initiated by reading the fluorescence every 5 s for 1 min, which comprises the baseline. Following the baseline establishment, the plate reader injects 10 μl of a 10× solution of the agonist 1 (in 2.5% DMSO). From this moment, the experiment follows the exact protocol described previously.

Compounds were prepared freshly from the DMSO stocks (50 or 10 mM) by dilution in Hepes-buffered solution nominally Ca2+ free (Gibco; catalog no.: 14185052). In the antagonist assay, the final concentration of agonist was 25 μM. For both experiments, only the central-most 60 wells of the plate were used, and the final concentration of DMSO was 0.5%.

The raw fluorescence was plotted against time, in an XY graph to determine the compound's activity. Using GraphPad, each well was normalized by the mean fluorescence of the baseline (first 12 reads). Then, we extracted the area under the curve for each concentration of the test compounds and normalized to the DMSO (0% activation) and 1 (100% activation). To determine the test compound concentration that yielded a half-maximal response (EC/IC50), channel activity (%) values were plotted as a function of test compound concentration, and the data were fitted to the sigmoidal dose–response equation (Equation 4) available in GraphPad.

Chemical synthesis

Ethyl 2,2,4-trimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline-6-carboxylate (3)

To a vial containing a magnetic stir bar, we added a mixture of ethyl 4-aminobenzoate (2, 1 eq), p-TsOH monohydrate (0.05 eq), and acetone (5.7 eq) in cyclohexane (0.1 ml/mmol). The vial was capped, and the reaction was started under microwave irradiation at 140 °C for 1 h. Upon completion, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (n-hexanes and EtOAc, 90:10 to 70:30) to give a white powder. The compound was immediately used in the next step without further purification. Yield: 148 mg (13%). LC–low-resolution MS (LR-MS): tR = 6.0 min. LR-MS (electrospray ionization [ESI]+) m/z calculated for C15H20NO25: 246 [M + H]+; found: 246 [M + H]+. To a stirred solution of the previously obtained compound, (1 eq) in EtOAc (10 ml/mmol) was added 10% Pd-C (0.5 eq), and it was stirred overnight at room temperature under H2 atmosphere (the flask was purged with N2 for 5 min, and then a balloon containing H2 was attached to it). The reaction was filtered through celite pad, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to furnish a mixture of 3 as a white solid. Yield: 254 mg (96%). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD, δ = ppm): δ 7.80 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.90 (dp, J = 12.6, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 1.79 (dd, J = 12.9, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 1.38 to 1.34 (m, 7H), 1.27 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H). LC–LR-MS: tR = 5.9 min. LR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C15H21NO2: 247 [M]+; found: 248 [M + H]+.

1-(2-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)acetyl)-2,2,4-trimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline-6-carboxylic acid (4)

3 (1 eq.), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (0.1 eq), pyridine (2.2 eq), phthalylglycyl chloride (1.2 eq), and toluene (3.7 ml/mmol) were charged in a tube. The tube was sealed, and the reaction was started under microwave irradiation at 140 °C for 1.5 h. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (n-hexane and EtOAc, 90:10 to 70:30) to give the mixture of the ester-protected compound as a white powder, which was immediately used in the next step of synthesis. Yield: 299 mg (71%). LC–LR-MS: tR = 6.6 min. LR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C25H26N2O5: 435 [M + H]+; found: 435 [M + H]+, 457 [M + Na]+, 473 [M + K]+. To the previously obtained compound, (1 eq) in ethanol (10 ml/mmol) was added to an aqueous solution of NaOH (5 eq) and stirred for 3 h at RT. The reaction was concentrated, and 2 ml of H2O was added. The pH was adjusted to slightly acidic (pH around 6.0) with an aqueous solution of HCl (1 M), and the solution was extracted with AcOEt (3 × 5 ml). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum to give the mixture of 4 as a white powder. Yield: 92 mg (99%). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD, δ = ppm): δ 7.95 to 7.90 (m, 3H), 7.58 (td, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (td, J = 12.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 1.97 (dd, J = 13.0, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.53 (s, 3H), and 1.40 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). LC–LR-MS: tR = 4.3 min. LR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C23H22N2O5: 406 [M]+; found: 425 [M + H + H2O]+, 447 [M + Na + H2O]+, and 462 [M + K + H2O]+.

2-(2-(6-(4-(3-(5,5-difluoro-7-(1H-pyrrol-2-yl)-5H-4l4,5l4-dipyrrolo[1,2-c:2′,1′-f][1,3,2]diazaborinin-3-yl)propanoyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-2,2,4-trimethyl-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)-2-oxoethyl)isoindoline-1,3-dione (MRC087)

In a round-bottom flask, were added 4 (1 eq.), N1-Boc-piperazine (1.1 eq), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (1.1 eq), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (1.1 eq.) in dichloromethane (DCM) (5 ml/mmol). The mixture was stirred for 16 h at room temperature. Upon completion, solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (n-hexanes and AcOEt, 50:50 to 70:30) to give the mixture of N-Boc-protected intermediate as a white powder, which was used immediately in the next step of synthesis. Yield: 45 mg (36%). LC–LR-MS: tR = 6.3 min. LR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C32H38N4O6: 575 [M + H]+; found: 519 [M − tBu]+, 575 [M + H]+, 597 [M + Na]+, 613 [M + K]+. The previously obtained compound was solubilized in DCM (2 ml), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, 1 ml) was added to it dropwise. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. Upon completion, the solvents were removed under vacuum to afford the mixture of the TFA salt of the piperazine intermediate as an off-white solid, which was used immediately in the next step of synthesis. Yield: 25 mg (82%). LC–LR-MS: tR = 4.3 min. LR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C27H30N4O4: 475 [M + H]+; found: 475 [M + H]+, 497 [M + Na]+, 513 [M + K]+. In a vial containing a stirring solution of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (14 eq) in N,N′-dimethylformamide (100 ml/mmol), was added the previously obtained compound (1 eq). The mixture was stirred for 5 min at room temperature, and then, EverFluor 590 SE (1.4 eq) was added, the vial was capped and purged with N2, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir in the dark for 16 h, at RT, under N2 atmosphere. Upon completion, the solvents were removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (DCM and MeOH, 99:01 to 98:02) to remove the unreacted EverFluor 590 SE. The column was then washed with DCM and MeOH (50:50), and the organic phase was evaporated under vacuum. The residue containing the desired compound was purified by flash chromatography (n-hexanes and AcOEt, 50:50 to 30:70) to give the mixture of MRC087 as a purple solid. Yield: 2.6 mg (58%). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ = ppm): δ 11.43 (s, 1H), 7.90 to 7.83 (m, 5H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 4.15 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 4H), 3.56 (s, 8H), 3.18 to 3.12 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 1.94 to 1.87 (m, 1H), 1.75 (s, 1H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.28 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.23 (s, 1H). LC–LR-MS: tR = 6.5 min. LR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C43H42BFN7O5: 785 [M]+; found: 766 [M − F]+, 785 [M]+. LC–high-resolution (HR)-MS tR = 4.6 min. HR-MS (ESI+) m/z calculated for C43H42BF2N7O5: 785.3309 [M]+; found: 786.3394 [M + H]+, 766.3354 [M − F]+. HR-MS (ESI−) m/z calculated for C43H42BF2N7O5: 785.3309 [M]+; found: 784.3247 [M − H]−. Purity: >95%.

Data availability

TRPML1-nLuc and other materials are available upon request to the corresponding authors. All data are contained within the article. Copies of 1H NMR spectra, HR-MS, and HPLC are available as Supporting information.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of CQMED-UNICAMP for their help and support. We thank the staff of the Life Sciences Core Facility (LaCTAD) at UNICAMP for the Genomics analysis. We thank the NMR facility at UNICAMP Chemistry Institute for its assistance. We thank Drs Matthew Robers and Samuel Hoare for the helpful discussions on the BRET experiments and binding kinetics, respectively.

Author contributions

M. R. C. and R. M. C. conceptualization; M. R. C., C. M. C. C.-P., J. E. T., and G. A. M. methodology; M. R. C. and R. M. C. formal analysis; M. R. C., C. M. C. C.-P., J. E. T., and G. A. M. investigation; M. R. C. writing–original draft; R. M. C. writing–review & editing; R. M. C. supervision; K. B. M. and R. M. C. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo; grant number: 2014/50897-0) and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico; grant number: 465651/2014-3). M. R. C. was the recipient of a FAPESP postdoctoral fellowship (grant number: 2021/04853-4). C. M. C. C-P. postdoctoral fellowship was in part funded by Promega Corporation.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Kirill Martemyanov

Footnotes

Present address for Carolina M.C. Catta-Preta: Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Contributor Information

Micael R. Cunha, Email: micaelrc@unicamp.br.

Katlin B. Massirer, Email: kmassire@unicamp.br.

Rafael M. Couñago, Email: rafael.counago@unc.edu.

Supporting information

Z-stacks reconstruction of HEK293T expressing hTRPML1-YFP in the presence of MRC087. Upper-left and right panels: DNA-stained nuclei (Hoechst 3341) and TRPML1-YFP, respectively. Lower-left and right panels: MRC087 (2.0 μM) and merge of all channels, respectively.

Supporting Figure S1.

Colocalization analysis of YFP and MRC087.A–D, colocalization analysis of YFP and MRC087 using CellProfiler. Data obtained from four different sets of images are shown. Magnification = 63×; white bar = 25 μm. Images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP5 II camera. E, the number of objects colocalized and not colocalized from (A–D) and Figure 3 is shown above the bars.

References

- 1.Yamaguchi S., Muallem S. Opening the TRPML Gates. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:209–210. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimm C., Butz E., Chen C.-C., Wahl-Schott C., Biel M. From mucolipidosis type IV to ebola: TRPML and two-pore channels at the crossroads of endo-lysosomal trafficking and disease. Cell Calcium. 2017;67:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatachalam K., Wong C.-O., Zhu M.X. The role of TRPMLs in endolysosomal trafficking and function. Cell Calcium. 2015;58:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Paola S., Scotto-Rosato A., Medina D.L. TRPML1: the Ca(2+)retaker of the lysosome. Cell Calcium. 2018;69:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C.-C., Keller M., Hess M., Schiffmann R., Urban N., Wolfgardt A., et al. A small molecule restores function to TRPML1 mutant isoforms responsible for mucolipidosis type IV. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4681. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasitinon S.Y., Eskiocak U., Martin M., Bezwada D., Khivansara V., Tasdogan A., et al. TRPML1 promotes protein homeostasis in melanoma cells by negatively regulating MAPK and Mtorc1 signaling. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2293–2305.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capurro M.I., Greenfield L.K., Prashar A., Xia S., Abdullah M., Wong H., et al. VacA generates a protective intracellular reservoir for helicobacter pylori that is eliminated by activation of the lysosomal calcium channel TRPML1. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1411–1423. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0441-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X., Li X., Xu H. Phosphoinositide isoforms determine compartment-specific ion channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:11384–11389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202194109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong X., Shen D., Wang X., Dawson T., Li X., Zhang Q., et al. PI(3,5)P2 controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca2+ release channels in the endolysosome. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:38. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W., Zhang X., Gao Q., Xu H. TRPML1: an ion channel in the lysosome. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2014;222:631–645. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54215-2_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leser C., Keller M., Gerndt S., Urban N., Chen C.-C., Schaefer M., et al. Chemical and pharmacological characterization of the TRPML calcium channel blockers ML-SI1 and ML-SI3. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;210 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmiege P., Fine M., Li X. Atomic insights into ML-SI3 mediated human TRPML1 inhibition. Structure. 2021;29:1295–1302.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergarajauregui S., Puertollano R. Two di-leucine motifs regulate trafficking of mucolipin-1 to lysosomes: trafficking of mucolipin-1 to lysosomes. Traffic. 2006;7:337–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen T.-W., Wardill T.J., Sun Y., Pulver S.R., Renninger S.L., Baohan A., et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahoo N., Gu M., Zhang X., Raval N., Yang J., Bekier M., et al. Gastric acid secretion from parietal cells is mediated by a Ca 2+ efflux channel in the tubulovesicle. Dev. Cell. 2017;41:262–273.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakai J., Ohkura M., Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca2+ probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:137–141. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett L.M., Hughes T.E., Drobizhev M. Deciphering the molecular mechanism responsible for GcaMP6m’s Ca2+-dependent change in fluorescence. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang C. WO2018005713-A1, World Intellectual Property Organization; 2018. Piperazine Derivatives as TRPML Modulators. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang C. US20200352921-A1, United States Patent; 2020. Aryl-sulfonamide and Aryl-Sulfone Derivatives as TRPML Modulators. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pevarello P., Cusano V., Sodano M., Torino D., Vitalone R., Liberati C., Piscitelli F. WO2021094974-A1, World Intellectual Property Organization.; 2021. Heterocyclic TRPML1 Agonists. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badura A., Sun X.R., Giovannucci A., Lynch L.A., Wang S.S.-H. Fast calcium sensor proteins for monitoring neural activity. Neurophotonics. 2014;1 doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.1.2.025008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosma R., Wang Z., Kooistra A.J., Bushby N., Kuhne S., van den Bor J., et al. Route to prolonged residence time at the histamine H 1 receptor: growing from desloratadine to Rupatadine. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:6630–6644. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basak S., Li Y., Tao S., Daryaee F., Merino J., Gu C., et al. Structure–kinetic relationship studies for the development of long residence time LpxC inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65:11854–11875. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obi P., Natesan S. Membrane lipids are an integral part of transmembrane allosteric sites in GPCRs: a case study of cannabinoid CB1 receptor bound to a negative allosteric modulator, ORG27569, and analogs. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65:12240–12255. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells C., Couñago R.M., Limas J.C., Almeida T.L., Cook J.G., Drewry D.H., et al. SGC-AAK1-1: a chemical probe targeting AAK1 and BMP2K. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:340–345. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agajanian M.J., Walker M.P., Axtman A.D., Ruela-de-Sousa R.R., Serafin D.S., Rabinowitz A.D., et al. WNT activates the AAK1 kinase to promote clathrin-mediated endocytosis of LRP6 and establish a negative feedback loop. Cell Rep. 2019;26:79–93.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong L.L., Vasta J.D., Monereau L., Locke G., Ribeiro H., Pattoli M.A., et al. A high-throughput BRET cellular target engagement assay links biochemical to cellular activity for bruton’s tyrosine kinase. SLAS Discov. 2020;25:176–185. doi: 10.1177/2472555219884881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger B.-T., Amaral M., Kokh D.B., Nunes-Alves A., Musil D., Heinrich T., et al. Structure-kinetic relationship reveals the mechanism of selectivity of FAK inhibitors over PYK2. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021;28:686–698.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vasta J.D., Corona C.R., Wilkinson J., Zimprich C.A., Hartnett J.R., Ingold M.R., et al. Quantitative, wide-spectrum kinase profiling in live cells for assessing the effect of cellular ATP on target engagement. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018;25:206–214.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall M.P., Unch J., Binkowski B.F., Valley M.P., Butler B.L., Wood M.G., et al. Engineered luciferase reporter from a deep sea shrimp utilizing a novel imidazopyrazinone substrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:1848–1857. doi: 10.1021/cb3002478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fine M., Schmiege P., Li X. Structural basis for PtdInsP2-mediated human TRPML1 regulation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4192. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06493-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machleidt T., Woodroofe C.C., Schwinn M.K., Méndez J., Robers M.B., Zimmerman K., et al. NanoBRET—a novel BRET platform for the analysis of protein–protein interactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:1797–1804. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong D., Hai J., Ma J., Wang C.-X., Zhang X.-D., Xiang Y.-N., et al. ML-SA1, a TRPML1 agonist, induces gastric secretion and gastrointestinal tract inflammation in vivo. STEMedicine. 2020;1:e3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmiege P., Fine M., Blobel G., Li X. Human TRPML1 channel structures in open and closed conformations. Nature. 2017;550:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature24036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plesch E., Chen C.-C., Butz E., Scotto Rosato A., Krogsaeter E.K., Yinan H., et al. Selective agonist of TRPML2 reveals direct role in chemokine release from innate immune cells. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.39720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimm C., Jörs S., Saldanha S.A., Obukhov A.G., Pan B., Oshima K., et al. Small molecule activators of TRPML3. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J.-H., Chung T.D.Y., Oldenburg K.R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. SLAS Discov. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robers M.B., Vasta J.D., Corona C.R., Ohana R.F., Hurst R., Jhala M.A., et al. Quantitative, real-time measurements of intracellular target engagement using energy transfer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1888:45–71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8891-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bosma R., Stoddart L.A., Georgi V., Bouzo-Lorenzo M., Bushby N., Inkoom L., et al. Probe dependency in the determination of ligand binding kinetics at a prototypical G protein-coupled receptor. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7906. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Copeland R.A. The drug–target residence time model: a 10-year retrospective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:87–95. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Copeland R.A., Pompliano D.L., Meek T.D. Drug–target residence time and its implications for lead optimization. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:730–739. doi: 10.1038/nrd2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan A.C., Borhani D.W., Dror R.O., Shaw D.E. Molecular determinants of drug–receptor binding kinetics. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patching S.G. Surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy for characterisation of membrane protein–ligand interactions and its potential for drug discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1838:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bocquet N., Kohler J., Hug M.N., Kusznir E.A., Rufer A.C., Dawson R.J., et al. Real-time monitoring of binding events on a thermostabilized human A2A receptor embedded in a lipid bilayer by surface plasmon resonance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:1224–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao J., Liu B., Qin F. Kinetic and energetic analysis of thermally activated TRPV1 channels. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1743–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen D., Wang X., Li X., Zhang X., Yao Z., Dibble S., et al. Lipid storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:731. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li D., Shao R., Wang N., Zhou N., Du K., Shi J., et al. Sulforaphane activates a lysosome-dependent transcriptional program to mitigate oxidative stress. Autophagy. 2021;17:872–887. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1739442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rautenberg S., Keller M., Leser C., Chen C.-C., Bracher F., Grimm C. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2022. Expanding the Toolbox: Novel Modulators of Endolysosomal Cation Channels, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowada T., Maeda H., Kikuchi K. BODIPY-based probes for the fluorescence imaging of biomolecules in living cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:4953–4972. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00030k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perroy J., Pontier S., Charest P.G., Aubry M., Bouvier M. Real-time monitoring of ubiquitination in living cells by BRET. Nat. Methods. 2004;1:203–208. doi: 10.1038/nmeth722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobayashi H., Picard L.-P., Schönegge A.-M., Bouvier M. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer–based imaging of protein–protein interactions in living cells. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:1084–1107. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venkatachalam K., Hofmann T., Montell C. Lysosomal localization of TRPML3 depends on TRPML2 and the mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:17517–17527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stirling D.R., Swain-Bowden M.J., Lucas A.M., Carpenter A.E., Cimini B.A., Goodman A. CellProfiler 4: improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22:433. doi: 10.1186/s12859-021-04344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen W., Park S., Patel C., Bai Y., Henary K., Raha A., et al. The migration of metastatic breast cancer cells is regulated by matrix stiffness via YAP signalling. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Z-stacks reconstruction of HEK293T expressing hTRPML1-YFP in the presence of MRC087. Upper-left and right panels: DNA-stained nuclei (Hoechst 3341) and TRPML1-YFP, respectively. Lower-left and right panels: MRC087 (2.0 μM) and merge of all channels, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

TRPML1-nLuc and other materials are available upon request to the corresponding authors. All data are contained within the article. Copies of 1H NMR spectra, HR-MS, and HPLC are available as Supporting information.