Abstract

Prior to use, newly generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) should be thoroughly validated. While excellent validation and release testing assays designed to evaluate potency, genetic integrity, and sterility exist, they do not have the ability to predict cell type-specific differentiation capacity. Selection of iPSC lines that have limited capacity to produce high-quality transplantable cells, places significant strain on valuable clinical manufacturing resources. The purpose of this study was to determine the degree and root cause of variability in retinal differentiation capacity between cGMP-derived patient iPSC lines. In turn, our goal was to develop a release testing assay that could be used to augment the widely used ScoreCard panel. IPSCs were generated from 15 patients (14-76 years old), differentiated into retinal organoids, and scored based on their retinal differentiation capacity. Despite significant differences in retinal differentiation propensity, RNA-sequencing revealed remarkable similarity between patient-derived iPSC lines prior to differentiation. At 7 days of differentiation, significant differences in gene expression could be detected. Ingenuity pathway analysis revealed perturbations in pathways associated with pluripotency and early cell fate commitment. For example, good and poor producers had noticeably different expressions of OCT4 and SOX2 effector genes. QPCR assays targeting genes identified via RNA sequencing were developed and validated in a masked fashion using iPSCs from 8 independent patients. A subset of 14 genes, which include the retinal cell fate markers RAX, LHX2, VSX2, and SIX6 (all elevated in the good producers), were found to be predictive of retinal differentiation propensity.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells, RNA-sequencing, retinal differentiation

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Significance Statement.

Development of patient-derived iPSCs and 3D retinal differentiation protocols have enabled autologous photoreceptor cell replacement. Unfortunately, line-to-line variability in differentiation capacity can hamper clinical translatability. In this study we, (1) determined the degree of variation in retinal differentiation potential between patient iPSC lines generated under cGMP, (2) used RNA sequencing to identify a genetic signature associated with retinal differentiation potential, and (3) developed a qPCR-based clinical release assay with the ability to predict differentiation potential. The power of the strategy presented is that it can be readily replicated for any tissue and/or disease.

Introduction

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) can be generated from a variety of somatic cell types by forced expression of a cocktail of transcription factors including OCT4 and SOX2.1-4 Like embryonic stem cells, hiPSCs have unlimited capacity for self-renewal and give rise to tissues of all 3 embryonic germ layers. These characteristics have fueled development of numerous differentiation protocols designed to generate tissue-specific cell types (eg,5-9), which can be utilized for diagnosis and treatment of human diseases. For instance, when combined with CRISPR-based genome editing, patient-derived iPSCs can be used to determine if, and by which mechanism, novel genetic variants cause inherited disease (eg,10-13). In addition, as patient-derived iPSCs can be produced from and transplanted back into the same individual, they are ideal for therapeutic cell replacement (eg,14-18). As promising as this technology is, its use can be limited by inconsistencies in cell line quality. For instance, despite the existence of well-established protocols for iPSC generation, validation, and differentiation, there is significant line-to-line variability with respect to lineage-specific differentiation capacity.19,20

Differentiation of hiPSCs into neural retina is a well-characterized process and several widely used protocols exist.18,21-23 These protocols typically rely on the application of exogenous factors and cell-intrinsic mechanisms to drive retinal cell fate specification. While the initial retinal differentiation studies were performed using adherent two-dimensional (2D) cell culture strategies,24,25 three-dimensional (3D) retinal organoid methods have become the gold standard.21,22 Despite the availability of well-developed assays designed to assess cell line quality (eg, ScoreCard26) and karyotyping27-30), there is currently no way to predict the ability of a given cell line to differentiate into a specific tissue type. In our experience, some iPSC lines are very capable of producing retinal organoids containing transplantable photoreceptor precursor cells while others are much less so. Unfortunately, the difference between lines that will be good and poor retinal cell producers is not evident until differentiation has been well underway. In fact, it often takes weeks and several rounds of differentiation before one can determine if a specific cell line will be useful for clinical application, this is quite problematic because it can take more than 120 days to generate transplantable photoreceptor precursor cells30-33 and production under current good manufacturing practices (cGMP) is expensive, requiring highly trained personnel and specialized facilities. As a result, for autologous cell replacement to be feasible, early detection of a cell line’s propensity for retinal differentiation will be critical. This will be especially true for early-stage photoreceptor cell replacement trials that will require millions of cells per patient to perform the potency and release testing required by the FDA.

The variability in iPSC differentiation behavior likely results from a combination of several cell-intrinsic and external factors including a patient’s genetic background and somatic cell epigenetic state. We hypothesized that transcriptional signatures of retinal differentiation propensity exist early in the process of cell fate commitment, weeks before detectable morphological differences. By identifying such a signature, one could get a better understanding of the causes of variability among cell lines and develop a strategy for predicting differentiation capacity much earlier in the clinical manufacturing process. To this end, the goal of this study was to determine the degree to which retinal differentiation capacity varies from one patient to the next and in turn develop a qPCR-based assay that could be used within the first week of differentiation to identify cell lines that had the greatest potential for retinal organoid production. Once validated, such a panel would in turn be useful as a release test that could be added to an established quality control pipeline for iPSC validation.

Methods

Generation and Maintenance of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

This study was approved by The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB) and adhered to the tenets set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. All human subjects in this study provided written informed consent. Dermal fibroblasts were isolated from skin biopsies obtained from a non-sun-exposed area of donor’s upper arm. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were generated under cGMP using passage 3 dermal fibroblasts as previously described.34 Briefly, iPSCs were generated using CytoTune 2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under ISO class 5 in E8 media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on Laminin 521 (Biolamina, Sweden) coated 6-well culture plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY, USA). For each patient, 12 iPSC colonies were picked at 25-30 days post-Sendai virus transduction and clonally expanded prior to being validated via Karyotyping and ScoreCard analysis as described below.

Karyotyping and ScoreCard Analysis

Cells in metaphase were analyzed by the Shivanand R. Patil Cytogenetics and Molecular Laboratory at the University of Iowa using Leica Microsystems metaphase scanning platform and CytoVision version 7.7 software. Cells were grown in vitro and arrested at metaphase with colcemid. Chromosomes were stained by the G-banding method. At least 20 cells were analyzed for each hiPSC line.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Force Curve Analysis

Before each day of measurements, an AFM probe with nominal stiffness of 0.03 N/m and a spherical 5 μm diameter silicon dioxide tip (Novascan, Milwaukee, WI, USA) was installed on the AFM (MFP-3D-BIO, Asylum Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The instrument was then calibrated by taking a single force curve on a clean FluoroDish (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) to determine the deflection inverse optical lever sensitivity (ie, the constant required to convert the voltage measured by the AFM’s photodetector to probe deflection) and virtual deflection (the change in measured voltage due to movement of the AFM head). The Sader calibration method35 was then used to obtain the probe’s spring constant based on its thermal vibration. Next, patient-derived iPSC lines were assigned random identifiers so that their identities were masked to the operator of the AFM. To allow for measurement of individual cells, undifferentiated iPSC cultures were detached from their culture vessels using Versene solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and spun onto glass bottomed fluorodishes (World Precision Instruments) that had been coated with CellTak (Corning, Waltham, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For cell measurements, the spherical tip of the probe was visually aligned with the cell center and moved with a velocity of 1 μm/s to indent the cell with increasing compressive force until a force trigger of 10 nN was reached. The AFM head was then held in position for 10 s to allow viscous relaxation of the cell before retracting the head at the same velocity used to indent the cell. We calculated the cellular reduced Young’s modulus based upon the Hertzian model of non-adhesive elastic contact between an elastic sphere and elastic half-space. The contact point (the point on the force-indentation curve corresponding to initial contact between the cell and probe) was determined by inspection for each curve. The Hertzian contact model was then fit to each force-indentation curve, allowing the extraction of each cell’s reduced Young’s modulus. We additionally fit the dwell region of the force curve to a biexponential decay function to identify fast and slow viscous time constants.36 The annotation of contact points and fits described above was performed using a software package developed by the authors (https://github.com/nstone8/pyrtz).

Retinal Organoid Differentiation

For analysis of retinal differentiation capacity, validated patient iPSC lines were transitioned to Matrigel-coated 6-well culture plates (Corning Costar) where they were maintained in a pluripotent state in mTESR1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Matrigel, which is known to vary significantly from one batch to the next, can have a significant impact on retinal differentiation capacity. As such, all iPSC lines used in this study were grown and differentiated using the same pre-qualified lot of Matrigel. Cells were passaged at approximately 80% confluence with dispase (2 mg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), typically every 4-5 days. To initiate differentiation, iPSCs were lifted and embryoid bodies (EB) were formed by gradually transitioning the medium from mTESR1 to neural induction medium (NIM) over a 3-day period as previously described.21,37 NIM consisted of DMEM/F12 (1:1), N2 supplement, non-essential amino acids, GlutaMAX, heparin (2 ug/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and Primocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). After 7 days 25-35 EBs were adhered overnight in each well of a 6-well plate using NIM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The following day the FBS was removed and the cells were grown in fresh NIM until day 16, with media changes every other day. On day 16, the colonies were mechanically lifted with a cell scraper, transferred into retinal differentiation medium (RDM), and cultured in suspension as 3D aggregates on poly-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (20 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich)-coated petri-dishes. RDM consisted of DMEM/F12 (3:1), B27 supplement, non-essential amino acids, Primocin (InvivoGen). Three-dimensional cultures gave rise to both retinal and non-retinal neurospheres that could be separated based on their morphological appearance.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Samples were collected after 0, 7, 16, and 20 days of differentiation and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNA was removed using DNaseI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. cDNA was synthesized using 1 ug of total RNA using Superscript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Whole Genome RNA-Seq Analysis

Transcription profiling using RNA-Seq was performed by the University of Iowa Genomics Division using manufacturer recommended protocols. Initially, 500 ng of DNase I-treated total RNA was used to enrich polyA containing transcripts using oligo(dT) primers bound to beads. The enriched RNA pool was then fragmented, converted to cDNA, and ligated to sequencing adaptors containing indexes using the Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA sample preparation kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The molar concentrations of the indexed libraries were measured using the Agilent Fragment Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and combined such that each library was represented equally in the pool for sequencing. The concentration of the pool was measured using the Illumina Library Quantification Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). Libraries were sequenced as 150 base-pair, paired-end reads on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform, resulting in 28.7 million paired-end reads per sample on average. Reads were mapped using STAR (ver. 2.5.3a_modified38;) to human genome build hg19 (release 1939;) and quantified using the Rsubread package (ver. 1.20.640;) with the GENCODE transcriptome annotation (release 1939;). Differential expression analysis was performed using edgeR (version 3.34.041;), and correction of technical replicates was performed with the duplicate correlation function from the limma package (version 3.28.142;). Differential expression results are reported in their entirety and are available for public download (GSE192665). We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis43 to investigate biological pathways enriched in the best and worst differentiating lines. On both days 0 and 7, we identified upstream regulators and canonical pathways for the set of genes with an expression difference greater than an absolute logFC of 0.75 between the best (n = 4) and poorest (n = 4) differentiating lines.

Differentiation of hiPSCs Into All 3 Embryonic Germ Layers

To differentiate hiPSCs into cells of all 3 embryonic germ layers, EBs were generated using dispase as described above. Cultures were transitioned into Knockout Serum Replacement (KSR)-fetal bovine serum (FBS) consisting of DMEM/F12 (1:1), 20% knockout serum replacement (KSR, Thermo Fisher Scientific), non-essential amino acids, GlutaMAX, and Primocin over a course of 4 days. EBs were maintained in 20% KSR-medium for 14 days as free-floating cultures before cells were collected for downstream analysis.

Differentiation of hiPSCs Into Extraembryonic Trophoblastic Cysts

EBs were generated using dispase, as described above and transferred to ultra-low adhesion culture dishes. Cultures were transitioned into KSR-FBS medium (KF-medium) from mTESR1 over 4 days. KF-medium consisted of DMEM/F12 (1:1), 5% KSR, 5% FBS, non-essential amino acids, GlutaMAX, and Primocin. To induce trophoblast differentiation, KF-medium was supplemented with 5 uM CHIR99021 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) on days 0-5. The free-floating spheres were then cultured in KF-medium supplemented with FGF-2 (10 ng/mL, Waisman Biomanufacturing, Madison, WI, USA), heparin (2 ug/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), and EGF (50 ng/mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific) until day 21 when they were harvested for analysis.

Differentiation of hiPSCs Into Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells

RPE cells were generated from iPSCs using the protocol developed by Foltz et al.44 Briefly, when iPSCs reached 80% confluence they were passaged from 1 well of a 6 well culture dish into 3 wells of a 12 well Matrigel coated cell culture dish. RPE cell fate was induced via modulating the insulin growth factor (IGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-b), and WNT signaling pathways. Mature pigmented RPE cells exhibited a cuboidal morphology by ~70 days of differentiation.

Immunocytochemistry

Undifferentiated hiPSCs were fixed in cold 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for intracellularly expressed antibodies, and blocked with 5% donkey serum in PBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in PBS and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies used include OCT4 (Cat# 09-0023, Stemgent, Cambridge, MA, USA); SOX2 (Cat# MAB2018, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), NANOG (Cat# AF1997, R&D Systems), and SSEA4 (Cat# MAB4304, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Alexa Fluor 495-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were diluted in PBS and incubated at room temperature. DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as a nuclear counterstain. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times and imaged using a TCS-SPE Leica confocal microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Gene Expression Analysis and Validation

Quantitative PCR was performed using PrimeTime Gene Expression master mix and PrimeTime gene assays listed in Supplementary Table S1 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA). PrimeTime gene assays were validated using MiniGene synthetic plasmid DNA (IDT-DNA) containing template sequences as positive controls. RT-qPCR for validation of our proposed gene panel was performed for 3 independent differentiations of 8 patient-derived iPSC lines. The PCR reactions for each of these 24 samples were performed in triplicate. The data was analyzed by first taking the mean of the CT values for each sample/target combination (technical replicates). The resulting per-sample expression levels were then normalized against the geometric mean of 3 housekeeping genes (HPRT, B2M, PGK1) on a per-sample basis. The mean of these normalized expression values was then taken for each cell line.

Data Availability

The differential RNA expression data that support the findings presented in this study are reported in their entirety and are available for public download (GSE192665). All other data are available in the article and online Supplementary Material.

Results

Propensity of Patient-Derived iPSCs to Generate Retinal Tissue

Fig. 1 illustrates that patient-derived iPSCs can have a dramatically different retinal differentiation capacities. In this experiment, 2 karyotypically normal cell lines that were judged to be equally pluripotent via ScoreCard analysis were simultaneously differentiated using the 3D differentiation protocol depicted in Fig. 1A. After 20 days of differentiation, one of these lines proved to be a poor retinal tissue producer (Fig. 1B–1D), while the other proved to be a good retinal tissue producer (Fig. 1E–1G). This widely adopted differentiation protocol was initially developed by Meyer et al.,21 and uses both adherent and free-floating culture conditions to generate and select 3D retinal organoids. Specifically, iPSCs cultured on Matrigel coated cell culture dishes are lifted using dispase and cultured in suspension on ultra-low adhesion surfaces to form embryoid bodies over a 7-day period. Embryoid bodies are subsequently adhered to tissue-culture plastic in the presence of 20% FBS overnight in NIM, where they are subsequently maintained for 9 days in NIM devoid of FBS. During this time optic-vesicle-like structures (Fig. 1F, 1H—yellow circles, and 1J) are formed. These are distinct from non-optic vesicles (Fig. 1C, 1H—red circles, and 1I) in that they develop a dense core surrounded by a ring of neural epithelium. At differentiation day 16, cells are manually lifted and plated in ultralow adhesion dishes where they are allowed to form free floating spheres. As evident in the good producing line (Fig. 1E–1G), by day 20 optic cups with the characteristic phase bright neural epithelium surrounding a denser core (Fig. 1G) are abundant. Optic cup-like spheres can be maintained in this state by replacing RDM every other day until retinal organoids containing fate restricted retinal neurons. Photoreceptor cell transcription factors, including CRX, NRL, and NR2E3 begin to appear within 50 days of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S1). The latter markers begin to plateau by 90 days of differentiation but photoreceptor cell-specific transcripts such as rhodopsin (rod-specific photopigment) and recoverin (expressed in both rods and cones) continue to rise as cells mature (Supplementary Fig. S1). Non-optic vesicles, which dominate in the poor producing line (Fig. 1C) give rise to an abundance of dense non-retinal organoids (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Generation of patient iPSC derived retinal organoids. A: Schematic depicting the 3D retinal differentiation protocol used in these studies to generate retinal organoids. B-G: Phase micrographs of undifferentiated (B & E), day 16 (C & F) and day 20 (D & G) differentiated iPSCs from a poor retinal producing (B-D) and a good retinal producing (E-G) cell line. H-J: Phase micrographs depicting the presence of optic vesicle and non-optic vesicle like structures. K-L: ScoreCard analysis of iPSCs from a poor retinal producer and a good retinal producer following differentiation into tissues of all 3 embryonic germ layers. While retinal differentiation capacity was drastically different, when subjected to a tri-lineage differentiation protocol and evaluated via ScoreCard analysis, both patient-derived iPSC lines downregulated pluripotency genes and expressed markers of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm at similar levels. Panel L—box and whiskers representative normative data. Graphic indicates algorithm score for expression of genes associated with self-renewal (negative following differentiation) and embryonic germ layer (positive following differentiation). Scale Bar = 1000 μm.

The inability of an iPSC line to differentiate was previously reported by Koyanagi-Aoi et al., who characterized 40 independent iPSC lines generated via retroviral reprogramming and found 7 that they characterized as differentiation defective.45 These 7 cell lines were all found to (1) express long terminal repeats of human endogenous retroviruses, (2) retain OCT4 expression, and (3) form tumors when subjected to a neural differentiation protocol and transplanted into immunocompromised mice.45 To investigate whether the poor retinal producers identified in the current study were also differentiation defective, (ie, unable to downregulate the pluripotency genes and express markers of ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) we used a protocol designed to direct differentiation into each of the 3 embryonic germ layers. Following differentiation, cultures were subjected to ScoreCard analysis. The self-renewal, ectoderm, mesendoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm genes were all expressed at similar levels in the good and poor retinal-producing lines (Fig. 1K–1L). To determine if poor retinal-producing lines were also poor at generating extraembryonic tissue, a differentiation protocol designed for production of trophoblastic cysts (see methods) was used. To our surprise, trophoblastic cysts produced by a poor retinal-producing line were larger and more abundant than those generated by a good retinal-producing line (Supplementary Fig. S2A). As these data demonstrate that poor retinal producers can, in fact, generate cells of both embryonic and extra embryonic lineages, we next asked if retinal differentiation capacity was linked to the differentiation protocol being used. To determine if select populations of retinal cells could be generated from poor producers, the 2D RPE cell derivation protocol developed by Foltz et al. was employed. Using iPSC lines determined to be good retinal producers, we can readily generate confluent cultures of RPE within 72 days of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S2B). While poor retinal producers appeared to progress through the early stages of the protocol (Supplementary Fig. S2C–S2D), by 12 days of differentiation cell monolayers contracted, lifted off the surface of the plate, and failed to give rise to mature RPE cells.

Characterization of the Retinal Differentiation Propensity Landscape

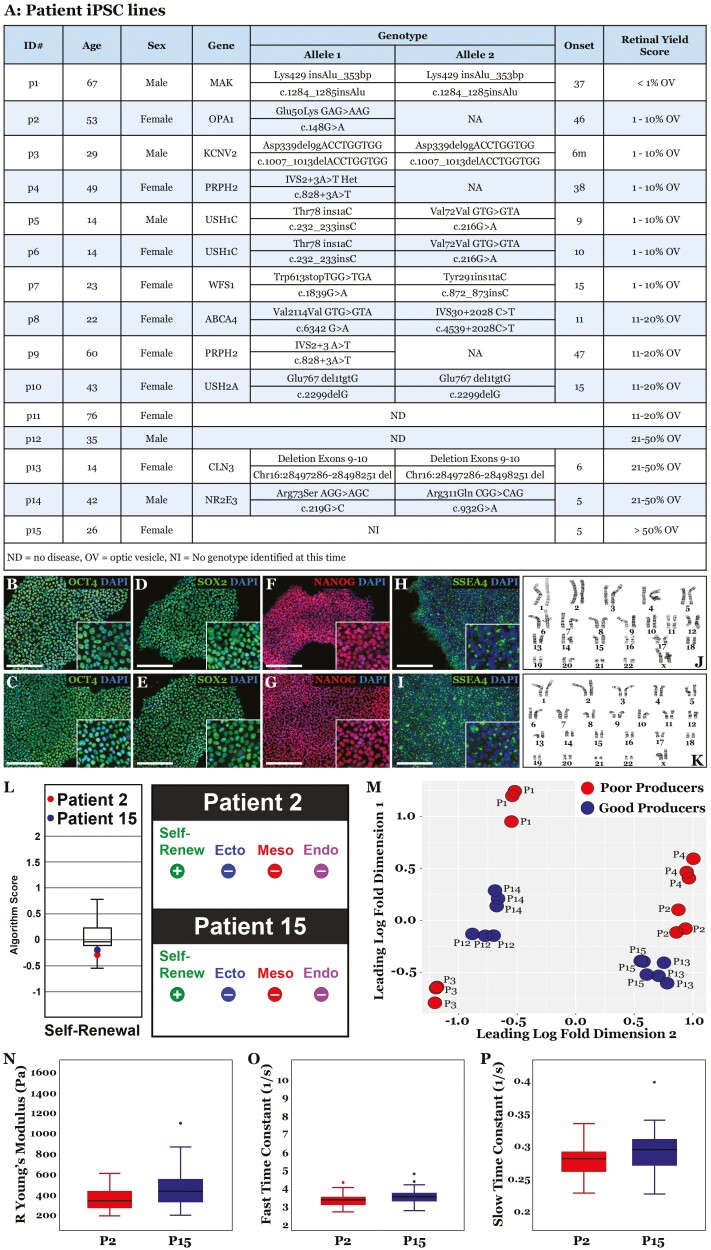

To determine the distribution of retinal differentiation propensity across a variety of cell lines, iPSCs were generated from 15 different patients ranging from 14 to 70 years of age (Fig. 2A). As per the methods section, at 25-30 days post-transduction, 12 iPSC clones were selected for each patient and passaged 10 times prior to being validated. As only minor differences in differentiation capacity between clones from the same patient were detected, a single clone was subsequently selected and evaluated via ScoreCard and cytogenetic analysis to confirm that they were pluripotent, devoid of the Sendai viral reprogramming factors, and had a normal karyotype. Validated patient iPSC lines were subsequently differentiated using the 3D differentiation protocol described above and scored on a 1-5 scale with 1 being the poorest retinal organoid producer and 5 being the best retinal organoid producer. Of the 15 lines studied, one was graded as a 1 (ie, <1% of the spheres produced at D20 were optic cups that went on to become retinal organoids), 6 were graded as a 2, 4 were graded as a 3, 3 were graded as a 4, and 1 was graded as a 5 (ie, >50% of the spheres produced at D20 were optic cups that went on to make become retinal organoids). To determine if there were obvious morphological differences between good and poor retinal-producing iPSC lines, P2 (53 YO female, Fig. 2J) and P15 (26 YO female, Fig. 2K) were evaluated via ICC (while P1 was a poorer retinal organoid producer than P2; P2 was selected for this comparison with P15, which was the best retinal organoid producer in this cohort because they were both obtained from female patients with retinal disease). No obvious differences in expression pattern or levels of OCT4 (Fig. 2B vs. 2C), SOX2 (Fig. 2D vs. 2E), NANOG (Fig. 2F vs. 2G), or SSEA4 (Fig. 2H vs. 2I) were detected. Likewise, no significant difference in self-renewal gene expression could be detected by ScoreCard analysis (Fig. 2L).

Figure 2.

Propensity of patient-derived iPSCs is independent of readily discernable iPSC characteristics. A: Demographic information and analytical data obtained from 15 independent patient-derived iPSC lines generated via cGMP compliant reprogramming of dermal fibroblast cells by a single scientist. B-I: Immunocytochemical analysis of iPSCs generated from patients 2 (B, D, F, and H—poor producer) and 15 (C, E, G, and I—good retinal producer) using antibodies targeted against the pluripotency markers OCT4 (B and C), SOX2 (D and E), NANOG (F and G), and SSEA4 (H and I). There was no discernable difference in cellular morphology or expression of these 4 markers. J-K: Sample karyotypic analysis demonstrating that both lines have a normal karyotype. L: ScoreCard analysis demonstrating that undifferentiated iPSCs generated from both patients 2 and 15 were pluripotent and did not express ectoderm, mesoderm, or endodermal markers. Box and whiskers representative normative data and graphic indicates algorithm score for expression of genes associated with self-renewal (positive) and embryonic germ layer (negative). M: Principal components analysis performed on whole-genome RNA-sequencing data obtained from patient iPSC lines 1-4 and 12-15. While each iPSC line clustered tightly following repeat rounds of retinal differentiation, poor and good producers did not reliably cluster together. N-P: Atomic force microcopy performed on iPSCs generated from both patients 2 and 15 demonstrating that there was no significant difference between cellular stiffness (N) or viscosity (O and P). Scale bar = 200 μm.

As the good and poor retinal-producing iPSC lines were microscopically indistinguishable, we next asked if significant differences in mechanical properties existed between these lines. We did this in part because Hammerick et al. had previously found that lower cell stiffness was correlated with greater differentiation potential.46 To evaluate the mechanical properties of a good and poor retinal-producing iPSC line, P2 and P15 were subjected to atomic force microscopy. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in either cell stiffness (Fig. 2N; Supplementary Fig. S3) or viscosity (Fig. 2O–2P; Supplementary Fig. S3). To determine if repeating the iPSC generation process altered a given patients retinal differentiation propensity, dermal fibroblasts from P2 and P4 (both classified as poor retinal producers in the previous experiment) were again targeted for reprogramming. Following generation, iPSCs were clonally isolated and expanded for 10 passages prior to being differentiated into retinal organoids as described above. Interestingly, both lines remained poor producers, suggesting that production capacity is a non-random event linked to the starting somatic cell line rather than reprogramming factor expression levels or reprogramming kinetics.

To determine if global gene expression differences could be detected between good and poor retinal-producing iPSC lines, lines P1-P4 (the 4 worst retinal organoid producers) and P12-P15 (the 4 best retinal organoid producers) were subjected to genome-wide RNA-sequencing analysis in triplicate (Fig. 2M). Multidimensional scaling was performed to identify groups of cells with similar global gene expression at day 0. Although replicates from each line clustered together, there was no obvious segregation of good and poor producers (Fig. 2M), suggesting that good and poor producers had similar gene expression profiles at day 0. Only 77 genes exhibiting an absolute logFC difference >0.75 were identified (Supplementary Fig. S4 and full differential expression results available at GSE192665). Of these 77 genes only 56 were determined to have a P value of <.05 (Supplementary Fig. S4). To determine if differences in expression between good and poor producers were associated with biological pathways involved with cellular potency or differentiation potential, ingenuity pathway analysis was performed. On the contrary, gene expression differences between good and poor producers were enriched in immunologic pathways, such as those involved in antigen presentation and macrophage activation (Supplementary Fig. S4). Collectively, these data indicate that while there are significant differences between iPSC lines with respect to retinal differentiation potential, good and poor retinal producers are remarkably similar prior to initiation of retinal differentiation.

Difference in Retinal Differentiation Propensity is Detectable During Early Cell Fate Specification

To determine if differences in retinal differentiation propensity could be detected during early cell fate specification, iPSC lines P1-P4 (herein termed poor producers) and P12-P15 (herein termed good producers) were differentiated for 7 days and the resulting embryoid bodies were harvested and subjected to RNA-sequencing. For this experiment each cell line was differentiated on 3 different occasions; that is, 24 independent RNA-sequencing reactions were performed. After mapping the reads to the human genome, multidimensional scaling was performed to identify groups of cell lines with similar global gene expression. In contrast to the experiments performed in iPSCs (day 0) prior to any differentiation, day 7 analysis revealed clear clustering of good producers and obvious segregation away from the poor producers (Fig. 3A). It is interesting that the poor producers did not all cluster together; that is, they had a wider spread within their group compared to good producers. However, the sequencing replicates from each round of differentiation of the same line clustered together very closely for both the good and poor producers. It is noteworthy that at this stage of differentiation, embryoid bodies are morphologically indistinguishable from one line to the next (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Gene expression differences between good and poor retinal producers at day 7. A: Multi-dimensional scaling of global gene expression profiles between good and poor retinal producers. B: Phase micrograph of embryoid bodies generated from a good vs. a poor retinal producing iPSC line. C: Ingenuity pathway analysis was performed to identify canonical biological pathways associated with gene expression differences between good and bad producers (absolute logFC > 0.75). The activation Z-score predicts increased (activated in good producers) or decreased (activated in poor producers) activation of each pathway (y-axis). Genes with an absolute logFC > 0.75 in select pathways are highlighted to the right of the plot and are colored according to their enrichment in good or poor producers. D: Upstream regulator analysis was performed to identify transcriptional regulators that may explain differences between good and poor producer cell lines. E: Visualization of SOX2 downstream effector gene expression across all good producer and poor producer lines. F: Visualization of genes in the OCT4 in embryonic stem cell pluripotency canonical pathway across all good producer and bad producer lines. Scale bar = 1000 μm.

Next, differential expression analysis was performed between the good and poor producing cell lines on day 7. Gene expression differences between the good and poor producers were more pronounced on day 7 than day 0. On day 7 there were 320 genes with an absolute logFC difference of at least 0.75 between good and poor producers (Supplementary Fig. S5, full differential expression results available at GSE192665). As above, to further explore the biological pathways associated with the differences in expression between good and poor producers, ingenuity pathway analysis was performed. On day 7, gene expression differences between good and poor producers were enriched in pathways involved in regulating pluripotency (such as OCT4 and NANOG) as well as those regulating epithelial to mesenchymal transition (Fig. 3C). Expression of all genes annotated in the “OCT4 in Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency” pathway was compared between poor (patients 1-4) and good (patients 12-15) producers, which included the bottom and top producers (Fig. 3F). This analysis revealed clear segregation between the good and poor producers and demonstrated sets of consistently downregulated genes across the good producing lines (eg, ETS2-AQR).

Next, we searched for upstream transcriptional regulators that could explain gene expression differences between the good and poor producing lines. SOX2 and OCT4 are the 2 transcriptional regulators that best explain the observed expression differences between the good and poor producers (Fig. 3D). As with OCT4, analysis of SOX2 downstream effector genes (Supplementary Fig. S6) revealed near complete segregation of good and poor retinal-producing cell lines (Fig. 3E). Importantly, the majority of the SOX2 effector genes (ie, ISL1-EOMES) were downregulated in the good producers and retained in the poor producers (Fig. 3E). In contrast, a small set of SOX2 effector genes including PAX6 and LHX2, which are required for retinal cell fate specification, were upregulated in the good producers as compared to the poor producers. Collectively, these data demonstrate that significant gene expression differences between good and poor retinal-producing iPSC lines can be detected as early as 7 days post-differentiation during early cell fate specification (weeks prior to retinal organoid formation).

Quantitative PCR Mediated Prediction of Retinal Differentiation Propensity

To develop a qPCR panel suitable for predicting retinal differentiation propensity (RDP), qPCR probe sets targeted against a subset of genes identified via differentiation expression and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis were developed. Probe sets were validated using MiniGene synthetic plasmid DNA (IDT-DNA). Of the genes evaluated, a subset (n = 20) was selected for inclusion (Fig. 4A—validated genes). In addition, probe sets targeted against 7 genes expressed in undifferentiated iPSCs (used to confirm pluripotency), and 3 housekeeping genes (used for normalization of gene expression), were also included (Fig. 4A). To validate the RDP-panel, 8 independent iPSC lines (3 from the original hypothesis-generating RNA-sequencing experiment and 5 that had not been previously evaluated) were used. Each line was masked to the experimenter and subjected to the 3D differentiation protocol described above. RNA was isolated from day 0 undifferentiated cells and day 7 embryoid bodies. As in the previous experiment, the undifferentiated iPSC lines (day 0) were indistinguishable (Fig. 4B–4E vs 4H–4K). Specifically, all lines formed tightly packed colonies containing cells with a high nucleus to Fig. 4B–4C vs. 4H–4I). Cells expressed markers of pluripotency, including OCT4 (Fig. 4D vs. 4J; Supplementary Fig. S7) and SOX2 (Fig. 4E vs. 4K; Supplementary Fig. S7), had a normal karyotype and were determined to be pluripotent via ScoreCard analysis. After 16 (Fig. 4F vs. 4L, optic vesical stage) and 20 (Fig. 4G vs. 4M, optic cup stage) days of differentiation, differences in retinal differentiation propensity began to emerge. Following retinal organoid formation (ie, maintenance of optic cups in RDM as described above), phase micrographs were obtained for each of the iPSC lines and provided to a masked evaluator. The proportion of retinal organoids per differentiation ranged from 9.9% to 56.1% of the total (Fig. 4N). Of the differentially expressed genes evaluated, 7 (NODAL, CER1, EN1, GBX2, MIXL1, GSC, and EOMES) were found to be downregulated in cell lines that produced greater than 10% retinal organoids (Fig. 4O). High expression of these genes was characteristic of the very worst producer (L3). Three genes (LEFTY2, ANXA1, and FOXD3) were found to be expressed at high levels in cell lines that produced less than 20% retinal organoids (Fig. 4P), allowing the moderate producing lines to be distinguished from the best producers. Similarly, 4 genes (RAX, LHX2, VSX2, SIX6) known to be markers of retinal differentiation, were expressed at low levels in the poorest producers (Fig. 4Q L3 and L9) with gradual increases in expression as the percent of retinal organoids per culture increased. This subset of genes provided a third level of information about the best retinal producers (ie, >20%). While the remaining 6 genes (RAB17, FOXO15, TDRD7, MEIS1, TMEM, and PAX6) appeared to be less predictive of retinal differentiation potential (Supplementary Fig. S7), the utility of genes such as RAB17, which was also identified as differentially expressed at D0, could increase as the number of iPSC lines evaluated is expanded. Collectively these data demonstrate the successful development of a qPCR panel with the ability to predict retinal differentiation propensity at the earliest stages of differentiation.

Figure 4.

Retinal differentiation panel design and validation. A: Genes included in the retinal differentiation panel, which was designed to predict the capacity of an iPSC line to differentiate into retinal tissue. Quantitative PCR probes for genes selected from the RNA-sequencing analysis data presented were validated using RNA isolated from patient iPSC lines 1-4 and 12-15 (validated genes). Seven pluripotency genes and 3 housekeeping genes were included to further confirm pluripotency and act as a loading control respectively. B-M: Microscopic and immunocytochemical analysis of patient iPSC lines 3 (poor producer) and 1 (good producer) at differentiation days 0, 16, and 20. N: To validate the retinal differentiation panel, 9 independent iPSC lines, 6 of which were new, were differentiated and the percentage of retinal organoids in each culture was calculated. Resulting retinal differentiation propensity for each of the 9 masked iPSC lines is presented as percent retinal organoids (ie, %RO). O-P: Heatmaps depicting gene expression data obtained from masked iPSC lines at 7 days of differentiation. Scale bar = 1000 μm.

Discussion

Following the successful isolation and culture of human embryonic stem (ES) cells more than 3 decades ago,47 there has been an intense investigation into their utility for therapeutic cell replacement. Numerous differentiation protocols, designed to direct tissue-specific cell fate commitment have been developed and adapted for clinical manufacturing.48-53 Likewise, several clinical trials using ES cell progeny have been performed or are under way (Clinical trials #s NCT02941991, NCT01344993, NCT02590692). As ES cells are harvested from developing embryos, there are both ethical and immunologic concerns associated with their use. These concerns were largely mitigated by the discovery that somatic cells could be induced to adopt a pluripotent ES cell-like state via forced expression of the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC.54 As resulting induced pluripotent stem cells can be generated from the patient for whom they are intended, autologous cell replacement for the treatment of neural degenerative disorders such as retinitis pigmentosa and Stargardt disease, is now possible. To that end, we and others have developed standard operating procedures for iPSC generation and retinal differentiation that adhere to clinically relevant current good manufacturing practices.34 In addition, potency and release assays, which are designed for qualification of the clinical product prior to transplantation, have been established.55

A challenge associated with the use of patient-derived iPSCs for autologous cell replacement is that standard clinical manufacturing is not well suited to simultaneous production and differentiation of multiple patient cell lines. On the contrary, cGMP manufacturing is often synonymous with large-scale production of a single product that is intended to be used for the treatment of many affected individuals. While automated iPSC generation, differentiation, and analysis platforms are being developed,56-59 these platforms have not yet been incorporated into a cGMP iPSC manufacturing and differentiation pipeline. As such, early-phase autologous cell replacement trials will likely require iPSCs to be generated and differentiated manually. As this process is time and labor intensive, it will be challenging to enroll more than a handful of individuals in a single clinical trial, meaning that careful patient selection will be critical. Typically, patient selection is based on available clinical data, which includes the patient’s age, genotype, comorbidities, residual function of the injured organ, and the anatomy of the injured tissue. While early-stage safety trials for inherited retinal degeneration should probably be performed in individuals with very advanced disease to allow the greatest chance of detecting efficacy with the smallest risk to the subjects, it will be necessary for the inner retinal neurons and their connections to the brain to be relatively intact. While these selection criteria are important, cell line quality must also be considered. For cell replacement trials focused on large batch production and delivery of unmatched ES cell progeny, the quality of the cell line, which includes its ability to differentiate into the desired cell type, can be determined early in the therapeutic development process. Specifically, scientists can easily determine which of the readily available NIH approved ES cell lines have the greatest capacity for retinal differentiation before patient enrollment criteria are considered. However, for autologous iPSC-based studies, pre-enrolment validation of the patient iPSC line is not possible. That is, the prospective patient will have to be enrolled in the study to be able to provide their sample for iPSC generation and validation.

Despite the existence of well-developed protocols such as the Thermo Fisher Scientific ScoreCard, which has revolutionized the way the stem cell community performs iPSC potency analysis, assays capable of predicting the retinal differentiation capacity of a specific iPSC line do not currently exist. In this study, we have shown that individual patient-derived iPSC lines, while indistinguishable from each other via ScoreCard, microscopic, karyotypic, and mechanical assays (Fig. 1), can vary greatly with respect to their ability to generate retinal organoids containing photoreceptor precursor cells. Interestingly, we found that iPSC lines that are poor retinal producers are not simply differentiation defective as previously reported.60 In fact, when subjected to spontaneous differentiation they are equally capable of differentiating into tissues of all 3 embryonic germ layers (Fig. 2). In addition, when intentionally differentiated down an extra-embryonic pathway, the poor retinal producers have a propensity for production of extra-embryonic trophoblastic cysts (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Current reprogramming models suggest that transcription-factor-mediated somatic cell reprogramming occurs in 2 phases: a long and stochastic chromatin modifying phase in which genome-wide epigenetic marks of somatic genes are inactivated or removed, followed by the gradual upregulation of endogenous pluripotency genes.61 To enhance somatic cell reprogramming, epigenetic modifiers such as BIX-01294, an inhibitor of the G9a histone methyltransferase,62 and valproic acid, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC)1,63 have been used. In addition to enhancing reprogramming efficiency, addition of these compounds reduces the number of transgenes required for successful iPSC generation.64-66 While the addition of these compounds to our reprogramming protocol did not alter the retinal production capacity of the iPSC lines generated (data not shown), we cannot rule out the role of epigenetic memory on retinal differentiation propensity. It may be that modifying the epigenetic state of iPSCs themselves would be more effective.67,68 For instance, Manzar et al. recently reported that treatment of iPSCs with 5-AZA-2ʹ-deoxycytidine, a potent inhibitor of DNA methylation, enhanced differentiation into functional pancreatic beta cells.69 While it is currently unknown whether such an approach would enhance retinal cell production, further investigation into the genome-wide epigenetic status of good and poor retinal producers, and how modification may alter differentiation capacity, is warranted.

Regardless of the root cause, from a clinical manufacturing perspective the identification of a transcriptional signature, and subsequent development of a qPCR assay suitable for predicting retinal differentiation capacity, would be extraordinarily valuable. As described in the results section above, while we could not detect a transcriptional signature that reliably predicted retinal differentiation propensity in undifferentiated iPSCs, we were able to identify a subset of genes that after just 7 days of differentiation were predictive of a cell lines ability to produce retinal organoids. Specifically, significant differences in global gene expression between good and poor retina-producing iPSC lines were detected. Genes such as NODAL, CER1, EOMES, GSC, and LEFTY2, which have been described as key regulators of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT),70,71 were found to be highest in poor retinal producers. In the developing embryo, gastrulation marks the beginning of a series of spatiotemporally controlled events that initiate differentiation of the 3 embryonic germ layers and subsequent organogenesis. One of the first decisions that are made in the embryo is for a subset of cells within the single-layered epithelial epiblast to differentiate and form the primitive streak. Epiblast cells subsequently undergo EMT as they migrate through the primitive streak, giving rise to mesendodermal progenitors that further differentiate into either nascent mesoderm or endoderm.72-74 Interestingly, genes that have been implicated in midbrain and forebrain development, such as EN175,76 and GBX2,77,78 were also expressed at higher levels in poor retinal cell producers.

Of the differentially expressed genes evaluated, 7 (NODAL, CER1, EN1, GBX2, MIXL1, GSC, and EOMES) were most useful for identifying lines whose differentiated spheres consisted of 10% or fewer retinal organoids. Inclusion of 3 additional genes (LEFTY2, ANXA1, and FOXD3) allowed for a 2nd level of discrimination, revealing lines that produced fewer than 20% retinal organoids. The inclusion of 4 additional genes (RAX, LHX2, VSX2, and SIX6), which are known to play an important role in retinal differentiation, provided the greatest level of discrimination between iPSC lines with respect to retinal production capacity. While cell lines with a retinal production capacity of <10% may be useful for in vitro evaluation of a patient’s disease pathology, they would not be ideal for inclusion in a clinical cell replacement trial. For instance, enrolment of a patient with a 5% retinal production capacity would require 10 times more material to provide the same number of transplantable cells as a patient with 50% retinal differentiation capacity. Given that therapeutic cells will be generated manually for the early-phase trials, inadvertent selection of a poor retinal producer would greatly reduce the total number of patients that a single site could reasonably enroll. By incorporating the qPCR retinal differentiation panel developed here into our iPSC validation pipeline we will be able to both predict a cell lines retinal differentiation capacity and obtain quantifiable clinical release testing data to support the choice of cell line selected for clinical use. For this to be possible, identification of a threshold of expression for each gene of interest will be required. To be confident that said threshold is robust, we are currently generating a large validation cohort containing 100 new iPSC lines. In addition to giving us confidence that expression thresholds are robust, by using a significantly larger cohort we may find that genes that failed to validate via qPCR using our restricted cohort, may in fact be useful for determining differentiation potential.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that there is significant variation among patient iPSC lines with respect to their retinal differentiation capacity, which persists from one round of differentiation to the next and is reproducible among clones of the same line and among lines derived from the same patient. Using a panel of 14 genes that are involved in early cell fate commitment we have developed a qPCR assay with the ability to predict retinal differentiation capacity weeks in advance of morphological clues. Incorporation of this quality assay into our iPSC validation pipeline will provide an additional metric for selecting a specific cell line for clinical use. In addition, while early identification of a cell line’s retinal differentiation capacity will allow us to identify patients that are most appropriate for early phase trials, this assay will also be useful for evaluating interventions targeted at improving retinal differentiation capacity. For instance, by using the developed qPCR panel we will be able to rapidly evaluate the utility of compounds such as 5-AZA-2ʹʹ-deoxycytidine to improve differentiation capacity, ultimately allowing for enrollment of patients independent of their initial differentiation capacity. By increasing the number of independent iPSC lines evaluated using this system, we believe that we will be able to expand the gene set and further refine the discriminatory potential of the assay.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RNA-seq data presented herein were generated by the Genomics Division of the Iowa Institute of Human Genetics which is supported, in part, by the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

Contributor Information

Jessica A Cooke, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Andrew P Voigt, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Michael A Collingwood, Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA.

Nicholas E Stone, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

S Scott Whitmore, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Adam P DeLuca, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Erin R Burnight, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Kristin R Anfinson, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Christopher A Vakulskas, Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA.

Austin J Reutzel, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Heather T Daggett, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Jeaneen L Andorf, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Edwin M Stone, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Robert F Mullins, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Budd A Tucker, Institute for Vision Research, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by Ruby Chair of Regenerative Ophthalmology, National Eye Institute R01 EY033331.

Conflict of Interest

M.A.C. declared employment at Integrated DNA Technologies. C.A.V. declared employment at Integrated DNA Technologies and Equity in the Danaher Corporation. All the other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

J.A.C.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing. A.P.V.: data curation, investigation, methodology, writing. M.A.C., N.E.S., S.S.W., A.J.R.: data curation, investigation, methodology. A.P.DeLuca, K.R.A., C.A.V.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology. E.R.B.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation. H.T.D.: data curation, investigation. J.L.A.: investigation, methodology. E.M.S.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, writing. R.F.M.: formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, writing. B.A.T.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing.

Data Availability

The differential RNA expression data that support the findings presented in this study are reported in their entirety and are available for public download (GSE192665). All other data are available in the article and online Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861-872. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917-1920. 10.1126/science.1151526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451(7175):141-146. 10.1038/nature06534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448(7151):318-324. 10.1038/nature05944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breckwoldt K, Letuffe-Breniere D, Mannhardt I, et al. Differentiation of cardiomyocytes and generation of human engineered heart tissue. Nat Protoc. 2017;12(6):1177-1197. 10.1038/nprot.2017.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li QV, Dixon G, Verma N, et al. Genome-scale screens identify JNK-JUN signaling as a barrier for pluripotency exit and endoderm differentiation. Nat Genet. 2019;51(6):999-1010. 10.1038/s41588-019-0408-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dye BR, Hill DR, Ferguson MA, et al. In vitro generation of human pluripotent stem cell derived lung organoids. Elife. 2015;4:e05098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rhodes K, Barr KA, Popp JM, et al. Human embryoid bodies as a novel system for genomic studies of functionally diverse cell types. Elife. 2022;11:e71361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirsch JF. Treatment and prognosis of benign hemispheric gliomas in children. Ann Pediatr (Paris). 1990;37(9):614-616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Powell SK, Gregory J, Akbarian S, Brennand KJ.. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 to the study of brain development and neuropsychiatric disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2017;82:157-166. 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park SH, Lee CM, Dever DP, et al. Highly efficient editing of the beta-globin gene in patient-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells to treat sickle cell disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(15):7955-7972. 10.1093/nar/gkz475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang T, Pine AR, Kotini AG, et al. Sequential CRISPR gene editing in human iPSCs charts the clonal evolution of myeloid leukemia and identifies early disease targets. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(6):1074-1089.e7. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ababneh NA, Scaber J, Flynn R, et al. Correction of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis related phenotypes in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived motor neurons carrying a hexanucleotide expansion mutation in C9orf72 by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing using homology-directed repair. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(13):2200-2217. 10.1093/hmg/ddaa106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lyu C, Shen J, Wang R, et al. Targeted genome engineering in human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with hemophilia B using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):92. 10.1186/s13287-018-0839-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maxwell KG, Augsornworawat P, Velazco-Cruz L, et al. Gene-edited human stem cell-derived beta cells from a patient with monogenic diabetes reverse preexisting diabetes in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(540). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pires C, Schmid B, Petraeus C, et al. Generation of a gene-corrected isogenic control cell line from an Alzheimer’s disease patient iPSC line carrying a A79V mutation in PSEN1. Stem Cell Res. 2016;17(2):285-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zou J, Mali P, Huang X, Dowey SN, Cheng L.. Site-specific gene correction of a point mutation in human iPS cells derived from an adult patient with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2011;118(17):4599-4608. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-335554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mandai M, Watanabe A, Kurimoto Y, et al. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1038-1046. 10.1056/NEJMoa1608368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim H, Lee G, Ganat Y, et al. miR-371-3 expression predicts neural differentiation propensity in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(6):695-706. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Osafune K, Caron L, Borowiak M, et al. Marked differences in differentiation propensity among human embryonic stem cell lines. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(3):313-315. 10.1038/nbt1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meyer JS, Shearer RL, Capowski EE, et al. Modeling early retinal development with human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(39):16698-16703. 10.1073/pnas.0905245106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhong X, Gutierrez C, Xue T, et al. Generation of three-dimensional retinal tissue with functional photoreceptors from human iPSCs. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4047. 10.1038/ncomms5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hau KL, Lane A, Guarascio R, Cheetham ME.. Eye on a dish models to evaluate splicing modulation. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2434:245-255. 10.1007/978-1-0716-2010-6_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Osakada F, Ikeda H, Mandai M, et al. Toward the generation of rod and cone photoreceptors from mouse, monkey and human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(2):215-224. 10.1038/nbt1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buchholz DE, Pennington BO, Croze RH, et al. Rapid and efficient directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into retinal pigmented epithelium. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(5):384-393. 10.5966/sctm.2012-0163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsankov AM, Akopian V, Pop R, et al. A qPCR ScoreCard quantifies the differentiation potential of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(11):1182-1192. 10.1038/nbt.3387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jo HY, Han HW, Jung I, et al. Development of genetic quality tests for good manufacturing practice-compliant induced pluripotent stem cells and their derivatives. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):3939. 10.1038/s41598-020-60466-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen Z, Zhao T, Xu Y.. The genomic stability of induced pluripotent stem cells. Protein Cell. 2012;3(4):271-277. 10.1007/s13238-012-2922-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Songstad AE, Wiley LA, Duong K, et al. Generating iPSC-derived choroidal endothelial cells to study age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(13):8258-8267. 10.1167/iovs.15-17073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiley LA, Burnight ER, DeLuca AP, et al. cGMP production of patient-specific iPSCs and photoreceptor precursor cells to treat retinal degenerative blindness. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30742. 10.1038/srep30742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lamba DA, McUsic A, Hirata RK, et al. Generation, purification and transplantation of photoreceptors derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8763. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zerti D, Hilgen G, Dorgau B, et al. Transplanted pluripotent stem cell-derived photoreceptor precursors elicit conventional and unusual light responses in mice with advanced retinal degeneration. Stem Cells. 2021;39(7):882-896. 10.1002/stem.3365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ribeiro J, Procyk CA, West EL, et al. Restoration of visual function in advanced disease after transplantation of purified human pluripotent stem cell-derived cone photoreceptors. Cell Rep. 2021;35(3):109022. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wiley LA, Anfinson KR, Cranston CM, et al. Generation of Xeno-free, cGMP-compliant patient-specific iPSCs from skin biopsy. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2017;42:4A 12 1-4A 4A 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. John E, Sader IL, Mulvaney P, Lee R.. White; Method for the calibration of atomic force microscope cantilevers. Rev Sci Instrum. 1995;66(7):3789-3798. https://doi.org/101063/11145439 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moreno-Flores S, Benitez R, Vivanco M, Toca-Herrera JL.. Stress relaxation and creep on living cells with the atomic force microscope: a means to calculate elastic moduli and viscosities of cell components. Nanotechnology. 2010;21(44):445101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohlemacher SK, Iglesias CL, Sridhar A, Gamm DM, Meyer JS.. Generation of highly enriched populations of optic vesicle-like retinal cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2015;32:1H 8 1-H 8 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15-21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frankish A, Diekhans M, Ferreira AM, et al. GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D766-D773. 10.1093/nar/gky955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W.. The R package Rsubread is easier, faster, cheaper and better for alignment and quantification of RNA sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(8):e47. 10.1093/nar/gkz114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK.. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139-140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J Jr., Tugendreich S.. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(4):523-530. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Foltz LP, Clegg DO.. Rapid, directed differentiation of retinal pigment epithelial cells from human embryonic or induced pluripotent stem cells. J Vis Exp. 2017;(128):e56274. 10.3791/56274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koyanagi-Aoi M, Ohnuki M, Takahashi K, et al. Differentiation-defective phenotypes revealed by large-scale analyses of human pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(51):20569-20574. 10.1073/pnas.1319061110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hammerick KE, Huang Z, Sun N, et al. Elastic properties of induced pluripotent stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17(3-4):495-502. 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145-1147. 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kashani AH, Lebkowski JS, Rahhal FM, et al. A bioengineered retinal pigment epithelial monolayer for advanced, dry age-related macular degeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(435). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pan CK, Heilweil G, Lanza R, Schwartz SD.. Embryonic stem cells as a treatment for macular degeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13(8):1125-1133. 10.1517/14712598.2013.793304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miyagishima KJ, Wan Q, Corneo B, et al. In pursuit of authenticity: induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium for clinical applications. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5(11):1562-1574. 10.5966/sctm.2016-0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miyagishima KJ, Wan Q, Miller SS, Bharti K.. A basis for comparison: sensitive authentication of stem cell derived RPE using physiological responses of intact RPE monolayers. Stem Cell Transl Investig. 2017;4:e1497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sharma R, Khristov V, Rising A, et al. Clinical-grade stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch rescues retinal degeneration in rodents and pigs. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(475). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. da Cruz L, Fynes K, Georgiadis O, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(4):328-337. 10.1038/nbt.4114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S.. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663-676. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Baghbaderani BA, Syama A, Sivapatham R, et al. Detailed characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cells manufactured for therapeutic applications. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2016;12(4):394-420. 10.1007/s12015-016-9662-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mullin NK, Voigt AP, Cooke JA, et al. Patient derived stem cells for discovery and validation of novel pathogenic variants in inherited retinal disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;83:100918. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elanzew A, Niessing B, Langendoerfer D, et al. The stemcellfactory: a modular system integration for automated generation and expansion of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:580352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vallone VF, Telugu NS, Fischer I, et al. Methods for automated single cell isolation and sub-cloning of human pluripotent stem cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2020;55(1):e123. 10.1002/cpsc.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schaub NJ, Hotaling NA, Manescu P, et al. Deep learning predicts function of live retinal pigment epithelium from quantitative microscopy. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(2):1010-1023. 10.1172/JCI131187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Li Y, Yimamu M, Wang X, et al. Addition of rituximab to a CEOP regimen improved the outcome in the treatment of non-germinal center immunophenotype diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells with high Bcl-2 expression. Int J Hematol. 2014;99(1):79-86. 10.1007/s12185-013-1472-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chung KM, Kolling FW, Gajdosik MD, et al. Single cell analysis reveals the stochastic phase of reprogramming to pluripotency is an ordered probabilistic process. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shi Y, Do JT, Desponts C, et al. A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(6):525-528. 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhou H, Wu S, Joo JY, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(5):381-384. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim JB, Greber B, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, et al. Direct reprogramming of human neural stem cells by OCT4. Nature. 2009;461(7264):649-643. 10.1038/nature08436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhu S, Li W, Zhou H, et al. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):651-655. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang Q, Xu X, Li J, et al. Lithium, an anti-psychotic drug, greatly enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Res. 2011;21(10):1424-1435. 10.1038/cr.2011.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cahan P, Daley GQ.. Origins and implications of pluripotent stem cell variability and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(6):357-368. 10.1038/nrm3584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Carcamo-Orive I, Hoffman GE, Cundiff P, et al. Analysis of transcriptional variability in a large human iPSC library reveals genetic and non-genetic determinants of heterogeneity. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20(4):518-532.e9. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Manzar GS, Kim EM, Zavazava N.. Demethylation of induced pluripotent stem cells from type 1 diabetic patients enhances differentiation into functional pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(34):14066-14079. 10.1074/jbc.M117.784280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chen T, You Y, Jiang H, Wang ZZ.. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): a biological process in the development, stem cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(12):3261-3272. 10.1002/jcp.25797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yamamoto Y, Miyazaki S, Maruyama K, et al. Random migration of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived human gastrulation-stage mesendoderm. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0201960. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M, Nieto MA.. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1438-1449. 10.1172/JCI38019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Moly PK, Cooley JR, Zeltzer SL, Yatskievych TA, Antin PB.. Gastrulation EMT is independent of P-cadherin downregulation. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153591. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Amadei G, Lau KYC, De Jonghe J, et al. Inducible stem-cell-derived embryos capture mouse morphogenetic events in vitro. Dev Cell. 2021;56(3):366-382.e9. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim TW, Piao J, Koo SY, et al. Biphasic activation of WNT signaling facilitates the derivation of midbrain dopamine neurons from hESCs for translational use. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(2):343-355.e5. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kouwenhoven WM, Veenvliet JV, van Hooft JA, van der Heide LP, Smidt MP.. Engrailed 1 shapes the dopaminergic and serotonergic landscape through proper isthmic organizer maintenance and function. Biol Open. 2016;5(3):279-288. 10.1242/bio.015032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang Z, Nakayama Y, Tsuda S, Yamasu K.. The role of gastrulation brain homeobox 2 (gbx2) in the development of the ventral telencephalon in zebrafish embryos. Differentiation. 2018;99:28-40. 10.1016/j.diff.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nakamura H. Regionalization of the optic tectum: combinations of gene expression that define the tectum. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24(1):32-39. 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01676-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The differential RNA expression data that support the findings presented in this study are reported in their entirety and are available for public download (GSE192665). All other data are available in the article and online Supplementary Material.

The differential RNA expression data that support the findings presented in this study are reported in their entirety and are available for public download (GSE192665). All other data are available in the article and online Supplementary Material.