Abstract

Background

Ostium secundum atrial septal defect (osASD) is a common congenital heart disease and transcatheter closure is the preferred treatment. Late device-related complications include thrombosis and infective endocarditis (IE). Cardiac tumours are exceedingly rare. The aetiology of a mass attached to an osASD closure device can be challenging to diagnose.

Case summary

A 74-year-old man with atrial fibrillation was hospitalized for evaluating a left atrial mass discovered incidentally 4 months earlier. The mass was attached to the left disc of an osASD closure device implanted 3 years before. No shrinkage of the mass was observed despite optimal intensity of anticoagulation. We describe the diagnostic workup and management of the mass that at surgery turned out to be a myxoma.

Discussion

A left atrial mass attached to an osASD closure device raises the suspect of device-related complications. Poor endothelialisation may promote device thrombosis or IE. Cardiac tumours (CT) are rare, and myxoma is the most common primary CT in adults. Although no clear relationship exists between the implantation of an osASD closure device and a myxoma, the development of this tumour is a possible occurrence. Echocardiography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance play a key role in the differential diagnosis between a thrombus and a myxoma, usually identifying distinctive mass features. Nevertheless, sometimes non-invasive imaging may be inconclusive, and surgery is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis.

Keywords: ASD, ASD closure device, Myxoma, Thrombus, Non-invasive imaging assessment, Neovascularization, Case report

Learning points.

To acknowledge myxoma as an uncommon but possible diagnosis of a mass related to an atrial septal defect closure device following transcatheter closure.

To recognize the key role played by a multimodality imaging approach in the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses.

To educate about the pivotal role played by follow-up care after transcatheter atrial septal defect closure as an important part of improving patient outcome.

Introduction

Ostium secundum atrial septal defect (osASD) is a common congenital heart disease. Transcatheter closure is the preferred treatment strategy. Late complications after transcatheter closure are rare.1 Cardiac myxoma is the most common primary cardiac tumour (CT) in adults and usually arises in the left atrium (LA) from the limbus fossae ovalis.2 No clear relationship between osASD transcatheter closure and myxoma development is known. We describe the diagnostic workup and management of a LA myxoma arising from a closure device 3 years after osASD transcatheter closure.

Timeline

| December 2017 | New-onset atrial fibrillation |

| February 2018 | Hospital admission for atrial fibrillation catheter ablation |

| Incidental finding (pre-procedural echocardiography) of ostium secundum atrial septal defect and mitral regurgitation | |

| Atrial fibrillation catheter ablation (radiofrequency) | |

| Transcatheter ostium secundum atrial septal defect repair | |

| October 2020 | Hospital admission for atrial fibrillation recurrence |

| Incidental finding (echocardiography) of a left atrial mass related to the atrial septal defect closure device | |

| Anticoagulant optimization: apixaban to acenocoumarol | |

| February 2021 | Persistent left atrial mass |

| Surgical removal of the mass and conclusive diagnosis of left atrial myxoma | |

| March 2021 | Last follow-up: patient clinically stable with permanent atrial fibrillation and good echocardiographic surgical result |

Case presentation

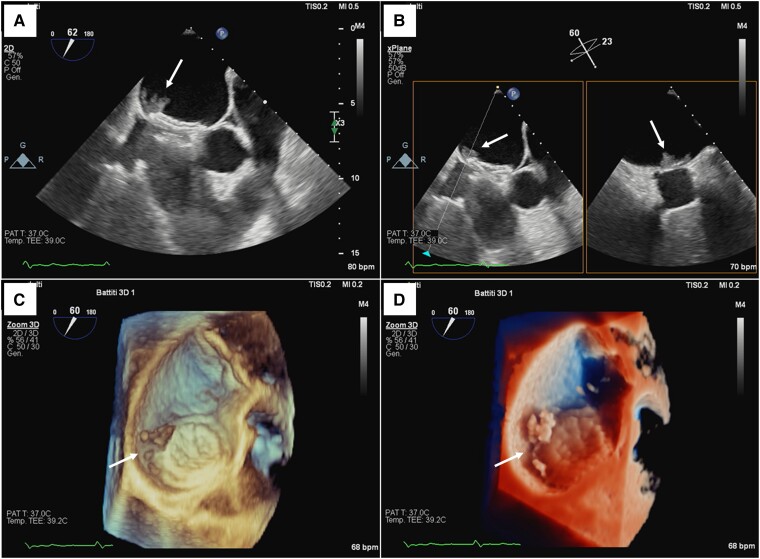

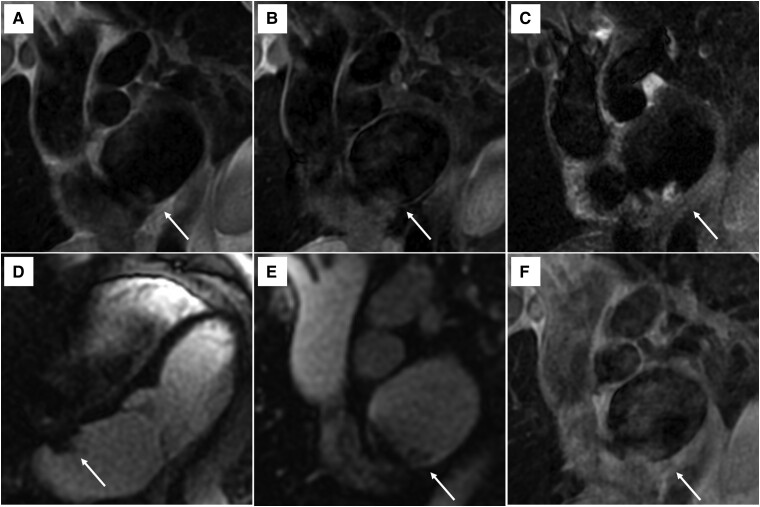

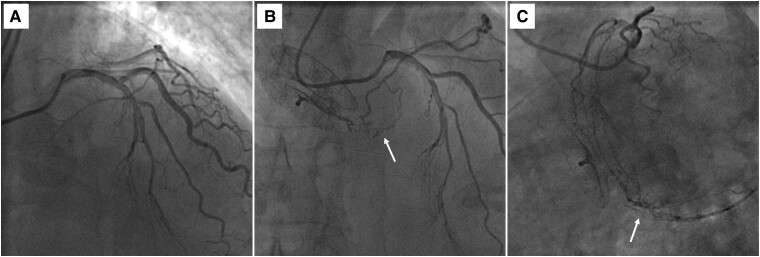

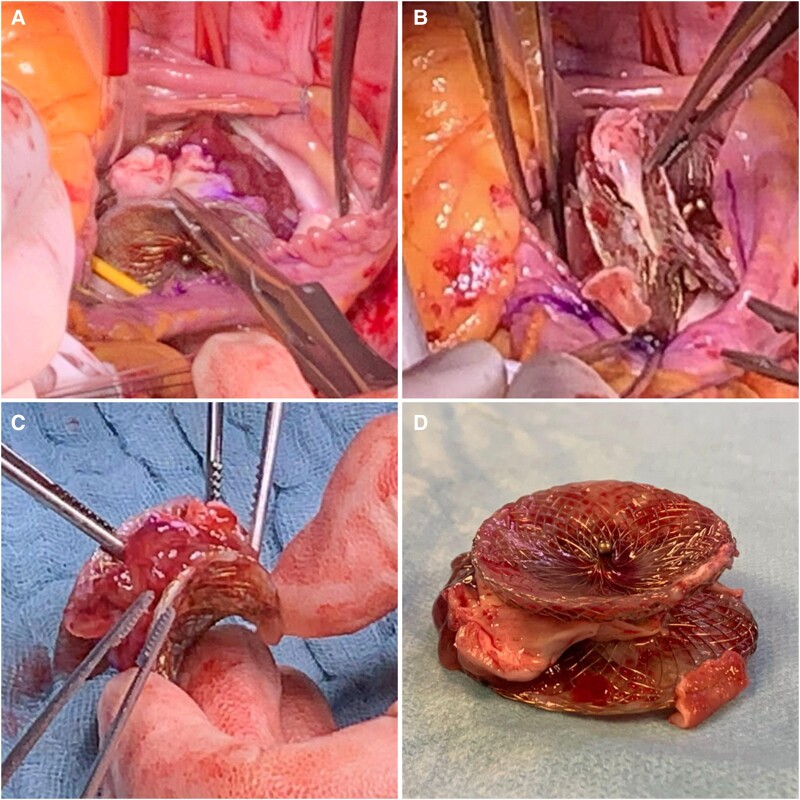

A 71-year-old man with atrial fibrillation (AF) was admitted for pulmonary vein ablation. He did not suffer from any chronic disease and had no past medical history. During pre-procedural workup, transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed a previously unknown osASD. Diagnostic cardiac catheterization revealed a significant left-to-right shunt. Coronary angiography excluded significant disease. After AF ablation, he underwent osASD transcatheter closure with a 27-mm Figulla Flex II device (Occlutech GmbH, Jena, Germany). The patient was discharged on apixaban. Thirty-two months later, he was hospitalized after an AF recurrence to undergo external electrical cardioversion. Physical examination was unremarkable. The patient was completely asymptomatic. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a LA mass attached to the left disc of the closure device and a moderate mitral regurgitation. A device-related thrombus was hypothesized, and apixaban was replaced with acenocoumarol to achieve optimal intensity of anticoagulation. Four months later, TEE showed that the size of the mass was unchanged. The mass was attached to the infero-posterior margin of the left disc of the closure device and had an isoechoic aspect with irregular margins and extreme mobility (Figure 1, Supplementary material online, Video S1). Severe mitral regurgitation was also found. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the mass had T1 and T1 fat-saturated isointensity and heterogeneous T2 hyperintensity. First-pass perfusion enhancement (FPP) was absent. Late contrast enhancement (LGE) sequences were difficult to assess because of the small size and mobility of the mass (Figure 2). Coronary angiography showed that the mass was neovascularized (Figure 3, Supplementary material online, Video S2). The case was discussed in a multidisciplinary heart team, and cardiac surgery was indicated. At surgery, the LA mass had myxoid appearance and was attached between the closure device discs (Figure 4). After en bloc resection of the mass and closure device, the LA septum was reconstructed using a pericardial patch. Also, the mitral valve was replaced with a bioprosthesis because of severe regurgitation due to bileaflet prolapse. On macroscopic examination, the mass had a gelatinous, friable surface, and irregular edges (Figure 4). The histopathological diagnosis was consistent with myxoma (Figure 5). The patient had a protracted time in the intensive care unit due to pneumonia, septic shock, and acute kidney injury. He was discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility 42 days after surgery. At 1-year follow-up, he is asymptomatic with permanent AF, and TTE shows a good surgical result and no tumour recurrence.

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiographic evaluation of the left atrial mass (arrows). (A) Two-dimensional image showing an isoechoic mass with irregular margins attached to the left disc of an atrial septal defect closure device. (B) X-plane imaging of the mass. (C) Three-dimensional image showing the main mass and satellite formations behind the left disc of the closure device. (D) Three-dimensional TrueVue image of the mass.

Figure 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of the left atrial mass (arrows). (A) T1 sequence showing mass isointensity compared to adjacent myocardium. (B) T1-fat-satured sequence showing mass isointensity compared to adjacent myocardium. (C) T2 sequence showing mass hyperintensity compared to adjacent myocardium. (D–E) Short- and long-axis first-pass perfusion sequences showing no mass enhancement. (F) T1 sequence 7 min after contrast injection (poor image quality due to small mass size and mobility).

Figure 3.

Neovascularization of the left atrial mass. (A) Coronary angiography performed before transcatheter atrial septal defect closure (3 years prior to admission). (B–C) Preoperative coronary angiography showing neovascularization (arrows) of the left atrial mass from the left circumflex coronary artery.

Figure 4.

Gross photographs of the left atrial mass. (A–B) intraoperative photographs showing a poorly endothelialized atrial septal defect closure device and a mass attached between the device discs. (C–D) Photographs of the removed device and mass showing the attachment site of the mass between the device discs.

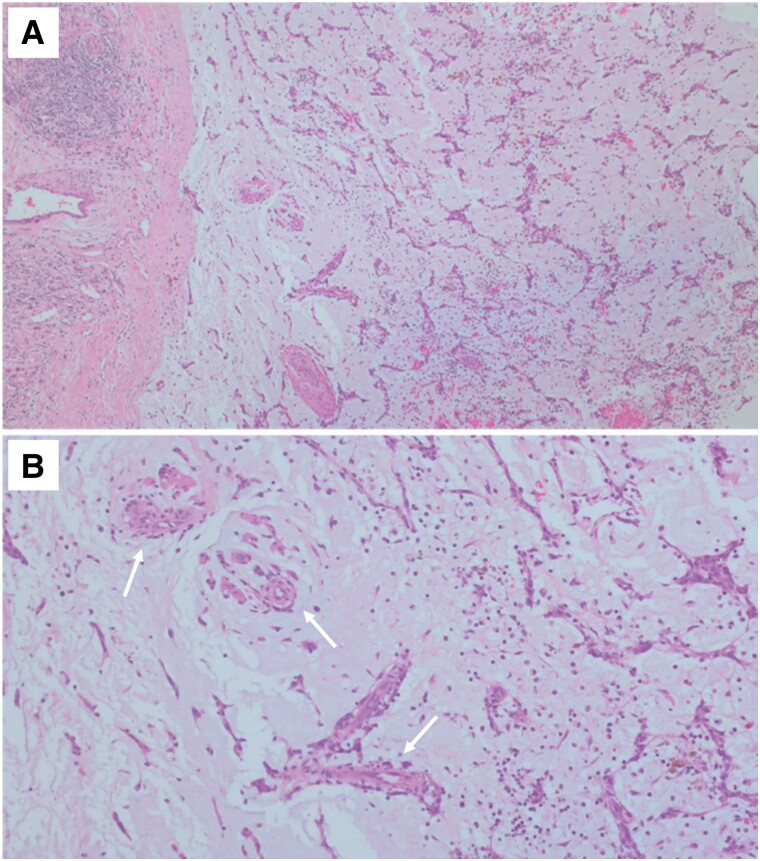

Figure 5.

Histology images. (A) Typical composition of a cardiac myxoma including stellate-shaped (lepidic), fusiform, and polygonal cells immersed in an abundant amorphous myxoid matrix (haematoxylin–eosin, 200×). (B) Areas of neovascularization (arrows) and inflammatory infiltrates (haematoxylin–eosin, 400×).

Discussion

A LA mass discovered incidentally late after transcatheter closure of an osASD poses a diagnostic dilemma. Device-related thrombosis and infective endocarditis (IE) are rare, and their late occurrence is even more infrequent.3,4 Lack of device endothelialisation and discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy and antibiotic prophylaxis after the procedure may promote these complications.5 Cardiac tumours are also rare, and myxomas represent the most common primary CT in adults.2 To our knowledge, a LA myxoma developing after transcatheter implantation of a closure device has been reported in only two cases, after closure of an osASD6 and of a patent foramen ovale (PFO),7 respectively. Nevertheless, no association between a myxoma and osASD or PFO percutaneous closure is known.

Clinical presentation may help in differentiating cardiac mass aetiology.8 Primary CT may produce systemic symptoms, cardiac mass effects, or embolic manifestations. The latter may also complicate device thrombosis and IE. Atrial fibrillation and other procoagulant conditions are risk factors for thrombi, while elevated inflammatory markers may indicate latent infection. Nevertheless, these signs are neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific.

Non-invasive imaging remains the mainstay for the differential diagnosis. Transthoracic echocardiography represents the first approach, while TEE allows higher spatial resolution. Real-time volume-rendered three-dimensional echocardiography and post-processed data from multiplanar reconstructions further improve the diagnostic accuracy. Mass size and morphology, attachment site, extension, and mobility may be evaluated. Typically, myxomas are solitary, polypoid, pedunculated, and oval-shaped with a smooth or gently lobulated surface. They are generally located in the LA, arising from the fossa ovalis.2,9 On the contrary, thrombi are often multiple, of various size, and may occur in different sites. Typically, they appear as sessile, iso-/hyperechoic masses with defined margins and variable mobility.9 Thrombus shrinkage is expected following anticoagulation, while myxomas usually grow over time.10 However, there are reports of thrombi that do not dissolve with anticoagulation3 and myxomas that show no tendency to grow.11

Cardiovascular MRI has high diagnostic accuracy.12 In the setting of a mass related to an implanted cardiac device, metal artefact may limit the diagnostic capability of this modality. In this setting, advanced imaging techniques should be used to improve image quality.13 Usually, fresh thrombi are hyperintense on T1 and T2 sequences, while chronic thrombi are iso-/hypointense. Similarly, myxomas are T1-isointense, but T2-hyperintense. First-pass perfusion, LGE, and post-contrast inversion time (TI) scout sequences increase the discriminative power. Thrombi are avascular masses and therefore do not typically enhance on FPP and LGE sequences. Rare exceptions are justified by neovascularization of chronic thrombi. Myxomas may show some enhancement on FPP and LGE, corresponding with regions rich with myxomatous tissue and focal inflammation. Nevertheless, these features are markedly more frequent in malignant tumours. Therefore, a negative FPP/LGE is inconclusive to exclude a myxoma. Lastly, thrombi usually show a typical TI scout pattern (hyper-/isointensity with short TI and hypointensity with long TI), which is exceptional in tumours.12

Our patient was asymptomatic, and the mass was an unexpected finding. Despite high-quality TEE images, the diagnosis remained unclear. Extreme mass mobility, location, and appearance were consistent with a myxoma. To the contrary, multiple formations attached to the closure device were compatible with blood clots. The mass size remained unchanged despite adequate anticoagulation. This made the hypothesis of thrombus less likely, but the absence of a tumour growth also questioned the diagnosis of myxoma. Cardiovascular MRI failed to clarify the diagnosis. T1, T1-fat-satured, and T2 sequences were consistent with a myxoma, while negative FPP was compatible with both, a thrombus and a myxoma. Unfortunately, LGE could not be assessed. Interestingly, coronary angiography demonstrated neovascularization of the mass. This finding was discordant with the negative FPP but may be justified by poor MRI image quality. Neovascularization and coronary-cameral fistulae formation have been reported in myxomas14 but may also occur in chronic thrombi.15 This highlights the importance of coronary assessment before surgery even in patients with a previous normal coronary angiography.

In our patient, diagnostic certainty was obtained only after surgical removal of the mass by histological examination. We cannot exclude that the association of myxoma and osASD closure was a result of chance. If a cause-and-effect relationship exists, we hypothesize that the device may have played a role as a stimulus to exuberant endothelialisation promoting cell transformation.

Conclusions

This case reports the uncommon finding of a LA myxoma arising between the discs of a closure device 3 years after transcatheter osASD closure. A multimodality imaging approach is essential to characterize LA masses. Nevertheless, sometimes surgery is still needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Patient perspective

Patient should be educated on the pivotal role of continuing echocardiography follow-up after transcatheter closure of an atrial septal defect.

Statement of consent

The authors confirm that written consent has been obtained from the patient for the submission and publication of this report including images, in line with the COPE guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Angelo Mastrangelo, Department of Interventional Cardiology, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Via Carlo Parea 4, 20138 Milan, Italy.

Paolo Olivares, Department of Interventional Cardiology, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Via Carlo Parea 4, 20138 Milan, Italy.

Ilaria Giambuzzi, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Via Carlo Parea 4, 20138 Milan, Italy.

Manuela Muratori, Department of Cardiovascular Imaging, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Via Carlo Parea 4, 20138 Milan, Italy.

Francesco Alamanni, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Istituto Clinico Sant’Ambrogio, Via Privata Val Vigezzo 5, 20149 Milan, Italy; Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Via Festa del Perdono 7, 20122 Milan, Italy.

Antonio L Bartorelli, Department of Interventional Cardiology, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS), Via Carlo Parea 4, 20138 Milan, Italy; Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, Via Festa del Perdono 7, 20122 Milan, Italy.

Lead author biography

Dr Angelo Mastrangelo studied medicine at the Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, from which he graduated in 2017. He is an alumnus of the Collegio Superiore of the University of Bologna. He completed his residency in cardiology at the Centro Cardiologico Monzino, University of Milan, Italy. He is passionate about interventional cardiology and currently works as an interventional cardiologist at the Division of University Cardiology of the IRCCS Ospedale Galeazzi – Sant’Ambrogio, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Dr Angelo Mastrangelo studied medicine at the Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, from which he graduated in 2017. He is an alumnus of the Collegio Superiore of the University of Bologna. He completed his residency in cardiology at the Centro Cardiologico Monzino, University of Milan, Italy. He is passionate about interventional cardiology and currently works as an interventional cardiologist at the Division of University Cardiology of the IRCCS Ospedale Galeazzi – Sant’Ambrogio, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the patient using the standardized institutional consent form.

Funding: The authors states to have received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online Supplementary material.

References

- 1. Jalal Z, Hascoet S, Baruteau AE, Iriart X, Kreitmann B, Boudjemline Y, et al. Long-term complications after transcatheter atrial septal defect closure: a review of the medical literature. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:1315.e11–1315.e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tyebally S, Chen D, Bhattacharyya S, Mughrabi A, Hussain Z, Manisty C, et al. Cardiac tumors: JACC CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol 2020;2:293–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krumsdorf U, Ostermayer S, Billinger K, Trepels T, Zadan E, Horvath K, et al. Incidence and clinical course of thrombus formation on atrial septal defect and patient foramen ovale closure devices in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nguyen AK, Palafox BA, Starr JP, Gates RN, Berdjis F. Endocarditis and incomplete endothelialization 12 years after Amplatzer septal occluder deployment. Tex Heart Inst J 2016;43:227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanabe Y, Suzuki T, Kuwata S, Izumo M, Kawaguchi H, Ogoda S, et al. Angioscopic evaluation of atrial septal defect closure device neo-endothelialization. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e019282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bac NH, Dinh NH, Van Thuan P, Bich Ha TC, Khoi LM. Atrial myxoma on atrial septal defect occlusion device: a rare but true occurrence. CASE (Phila) 2021;5:204–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta N, Abdelsalam M, Maini B, Mumtaz M, Mandak J. Intra-atrial mass-thrombus versus myxoma, post-Amplatzer atrial septal defect closure device deployment. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foà A, Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, Rucci P, Di Marco L, Pacini D, et al. Clues and pitfalls in the diagnostic approach to cardiac masses: are pseudo-tumours truly benign? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022;29:e102–e104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. L'Angiocola PD, Donati R. Cardiac masses in echocardiography: a pragmatic review. J Cardiovasc Echogr 2020;30:5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walpot J, Shivalkar B, Rodrigus I, Pasteuning WH, Hokken R. Atrial myxomas grow faster than we think. Echocardiography 2010;27:E128–E131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elsherif Z, Mahmood N, Ahmed AM. 30-year follow-up of an unoperated left atrial myxoma: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2020;4:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pazos-López P, Pozo E, Siqueira ME, García-Lunar I, Cham M, Jacobi A, et al. Value of CMR for the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee EM, Ibrahim EH, Dudek N, Lu JC, Kalia V, Runge M, et al. Improving MR image quality in patients with metallic implants. Radiographics 2021;41:E126–E137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balci AY, Sargin M, Akansel S, Ünal Dayi S, Kuplay H, Mete ME, et al. The importance of mass diameter in decision-making for preoperative coronary angiography in myxoma patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019;28:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soulen RL, Grollman JH Jr, Paglia D, Kreulen T. Coronary neovascularity and fistula formation: a sign of mural thrombus. Circulation 1977;56:663–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online Supplementary material.