Highlights

-

•

Ultrasound was successfully used as an aid to prepare antioxidative chitosan-glucose MRPs.

-

•

Reaction temperature and sonication time dramatically affected the property of MRPs.

-

•

Chitosan-based MRPs could be used as an effective substance for cross-linking with TPP.

-

•

pH of both MRPs and TPP solutions influenced the characteristics of nanoparticles.

-

•

Solution pH of 4.0 was suggested to create nanoparticles with antioxidant enhancement.

Keywords: Ultrasound-assisted process, Maillard reaction product, Chitosan nanoparticle, Tripolyphosphate cross-linking, FTIR-analysis, Antioxidant activity

Abstract

The influence of ultrasonic processing parameters including reaction temperature (60, 70 and 80 °C), time (0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min) and amplitude (70, 85 and 100%) on the formation and antioxidant activity of Maillard reaction products (MRPs) in a solution of chitosan and glucose (1.5 wt% at mass ratio of 1:1) was investigated. Selected chitosan-glucose MRPs were further studied to determine the effects of solution pH on the fabrication of antioxidative nanoparticles by ionic crosslinking with sodium tripolyphosphate. Results from FT-IR analysis, zeta-potential determination and color measurement indicated that chitosan-glucose MRPs with improved antioxidant activity were successfully produced using an ultrasound-assisted process. The highest antioxidant activity of MRPs was observed at the reaction temperature, time and amplitude of 80 °C, 60 min and 70%, respectively, with ∼ 34.5 and ∼20.2 μg Trolox mL−1 for DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power, respectively. The pH of both MRPs and tripolyphosphate solutions significantly influenced the fabrication and characteristics of the nanoparticles. Using chitosan-glucose MRPs and tripolyphosphate solution at pH 4.0 generated nanoparticles with enhanced antioxidant activity (∼1.6 and ∼ 1.2 μg Trolox mg−1 for reducing power and DPPH scavenging activity, respectively) with the highest percentage yield (∼59%), intermediate particle size (∼447 nm) and zeta-potential ∼ 19.6 mV. These results present innovative findings for the fabrication of chitosan-based nanoparticles with enhanced antioxidant activity by pre-conjugation with glucose via the Maillard reaction aided by ultrasonic processing.

1. Introduction

Chitosan is a linear heterogenic polysaccharide obtained by the deacetylation of chitin under alkaline conditions, which is now increasingly used in the food industry because of its nontoxic, non-allergenic, biodegradable and biocompatible properties. Chitosan is composed of D-glucosamine and N-acetylated residues linked through β-(1→4) glycosidic bonds [1], [2]. Chitosan has free amine (NH2) functional groups that can be modulated into several forms for various applications [3].

Amine groups in the chitosan molecule can conjugate with carbonyl groups (–CHO) of sugars via the Maillard reaction as an effective method to improve the physicochemical and biological properties of chitosan, especially its antioxidant activity [4]. Chitosan-based Maillard reaction products (MRPs), mostly prepared using the wet heating method, are significantly influenced by reactant type and concentration, solution pH, temperature, and time [5].

Ultrasound is an assistance technique that can accelerate heat/mass transfer, chemical reactions and structure alterations of compounds in various processes by generating intensive pressure, localized high temperature, strong shear stress and radicals [6], [7]. The rate enhancement of the Maillard reaction using ultrasound has been reported previously between amino acids/proteins and various sugars [8], [9], [10]. However, few studies have investigated the use of ultrasound assistance for the Maillard reaction between chitosan and sugars. Moreover, results from the previous studies suggested that the formation rate and characteristics of chitosan-based MRPs were influenced by variables including the type of chitosan [11], chitosan and sugar ratio [12], sugar type and concentration [13], reaction temperature and time [14] and solution pH [12], [15]. This study therefore examined the effect of ultrasound treatment at different temperatures (60, 70 and 80 °C) and times (0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min) on the formation, characteristics and antioxidant activity of chitosan-based MRPs. Furthermore, ultrasound-assisted generated chitosan-based MRPs with improved antioxidant activity can be used to fabricate multifunctional chitosan-based encapsulation and delivery systems, such as chitosan nanoparticles.

Chitosan nanoparticles are classified as a polymeric nanoparticle type that usually has a size range between 10 and 1,000 nm [16], [17]. Different methods have been used to prepare chitosan nanoparticles. The ionic gelation technique based on the electrostatic interaction between protonated amine groups of chitosan (NH3+) and negatively charged groups of sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) has recently attracted increased attention. This method requires simple and mild conditions without the need for high temperatures and organic solvents. Moreover, TPP is an inexpensive polyanion with low toxicity that rapidly induces the formation of nanoparticles through inter and intra-molecular linkages after mixing with chitosan in an aqueous acidic solution [18], [19].

Several promising applications of chitosan nanoparticles have been reported, e.g., encapsulating and delivering various active ingredients for multifunctional uses [20], [21]. Antioxidant activity improvement of bioactive compounds both in vitro and in model food systems by loading them into chitosan nanoparticles has been studied [22], [23], [24]. Naked chitosan nanoparticles have no or low antioxidant activity [25], [26]; however, the antioxidant activity of chitosan can be enhanced through the Maillard reaction [1], [4]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the antioxidant activity of naked chitosan nanoparticles could be improved using chitosan-based MRPs as a reactant. No previous studies have investigated the fabrication of nanoparticles using MRPs from ultrasound-assisted conjugation between chitosan and sugars. Here, the effect of pH of chitosan-based MRP solutions (4.0 and 6.0) obtained from ultrasound treatment and TPP solutions (2.0, 4.0 and 6.0) on the formation, characteristics and antioxidant activity of nanoparticles were investigated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Powdered chitosan (medium molecular weight, 190–310 kDa; degree of deacetylation, 75–85%), dextrose monohydrate or D-glucose, sodium tripolyphosphate (Na5P3O10), glacial acetic acid (CH3COOH), sodium acetate (CH3COONa), disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4-2H2O), monosodium phosphate (NaH2PO4-2H2), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), potassium ferricyanide (K3Fe(CN)6) and ferric chloride (FeCl3) of analytical grade were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Pte Ltd., Singapore. Deionized water was used to prepare all the solutions.

2.2. Ultrasound-assisted formation of chitosan-glucose Maillard reaction products (MRPs)

A UIP 1000 ultrasound system with a sonotrode BS2d34 and total power of 1000 W (Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH, Teltow, Germany) was used to study the influence of temperature (60, 70, and 80 °C) and ultrasonic time (15, 30, 45 and 60 min) on Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose operated at frequency and amplitude of 20 kHz and 70%, respectively [10]. Stock chitosan and glucose solutions were separately prepared at 1.5 wt% in 0.1 M acetate buffer at pH 4.0. After mixing at a mass ratio of 1:1 in a covered glass beaker (600 mL) [11], the solution was heated for about 5 min in an oil bath under stirring at 350 rpm to the desired temperature before passing through the ultrasound process. The ultrasound generator was inserted in the sample solution and the container was placed in a refrigerated cooling water bath to maintain the desired temperature. After reaching the set time, the beaker containing the Maillard reaction products (MRPs) was immediately cooled in an ice water bath. The cooled reaction product solution was then transferred into 50 mL Greiner centrifuge tubes (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd., Singapore), wrapped with aluminum foil and stored at − 20 °C.

To evaluate the impact of amplitude level, ultrasound treatments at amplitudes of 100 and 85% were compared with 70%. The chitosan-glucose mixture solution heated at 80 °C for 60 min without ultrasound being applied was denoted as 0% amplitude or thermal-treated sample was also prepared.

2.3. Fabrication of chitosan-glucose MRPs-based nanoparticles

2.3.1. Effect of initial pH of MRPs and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solutions

Ultrasound-assisted chitosan-glucose MRPs in acetate buffer at pH 4.0 and 6.0 were prepared at 80 °C for 60 min by applying ultrasound at 20 kHz and 70% amplitude, following the method described in Section 2.2. Crosslinking agent solutions of 2.0 wt% TPP in acetate buffer at various pH (2.0, 4.0 and 6.0) were prepared. An appropriate amount of each TPP solution was then separately added dropwise into each MRPs solution to obtain a mixture with MRPs-TPP mass ratio of 3:1 [27]. After stirring at 400 rpm for 60 min at room temperature, the dispersed sample containing nanoparticles was subjected to centrifugation (∼4°C) at 12,879×g for 60 min (Centrisart D-16C Refrigerated, Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen, Germany). The precipitated nanoparticles were collected and washed twice with deionized water (∼3 mL). The washed nanoparticles were then subjected to freeze-drying (Lyovapor™ L-300, BUCHI Pte Ltd., Singapore) using condenser temperature and vacuum pressure of −105 °C and 0.04 mbar, respectively. The dried nanoparticles were kept in a sealed container in a dry place until measuring their FTIR spectra, particle yield, zeta-potential, particle size, particle morphology and antioxidant activity.

2.3.2. Comparison between ultrasound-assisted and thermal-treated MRPs

Chitosan-glucose MRPs in acetate buffer at pH 4.0 were prepared at 80 °C for 60 min with and without applying ultrasound (20 kHz and 70% amplitude), following the method described in Section 2.2. Sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution (2.0 wt%) in acetate buffer at pH 4.0 as the crosslinking agent was also prepared. An appropriate amount of TPP solution was then added dropwise into the solution of Maillard conjugates to obtain a mixture with MRPs-TPP mass ratio of 3:1 [27]. Preparation steps were then performed, as described in Section 2.3.1, until freeze-dried nanoparticles were obtained. The dried nanoparticles were kept in a sealed container in a dry place before measuring the zeta-potential, particle size, and antioxidant activity.

2.4. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy analysis

Approximately 2 mg of freeze-dried samples were ground with KBr to a fine powder and then compressed into pellets. Transmittance spectra of the samples were then recorded in the wavenumber range between 500 and 4000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 with 32 scans using a PerkinElmer Spectrum One FT-IR Spectrometer (PerkinElmer LAS Ltd., Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.5. Zeta-potential measurement

The MRPs solutions were diluted 100 times with acetate buffer solution before measurement. The freeze-dried nanoparticle samples were dispersed in an acetate buffer solution at a concentration of 0.05 mg mL−1 [28]. A 1 mL aliquot of each diluted MRPs solution and nanoparticles dispersion was then placed into a glass cell cuvette, and the zeta-potential was measured at 25 °C using a NanoBrook Omni zeta potential analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, NY, USA).

2.6. Color measurement

The color of the chitosan-glucose MRPs solutions was measured according to the method of Dong et al. [8] with some modifications. Each sample solution (∼20 mL) was placed in a plastic cell of 10 mm path length (CM-A131, 38 mm width × 50 mm height), and color was measured using a colorimeter with transmittance specimen holder mode (CM-5 Spectrophotometer, Konica Minolta Sensing Pte Ltd., Singapore). Color indices including L*, a* and b* were recorded. The browning index (BI) and total color difference (ΔE) were calculated using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.7. Absorbance measurement

Absorbance values at 294 and 420 nm, respectively, were measured to monitor development of the intermediate and final products, respectively, in the chitosan-glucose MRPs solutions obtained from ultrasound-assisted preparation. The method modified from Yu et al. [10] was carried out using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Research Laboratory (Europe) Ltd., Manchester, UK). Briefly, 3 mL of each sample solution were placed into plastic cuvettes with a path length of 10 mm (12.7 mm × 12.7 mm × 45 mm). The measurements were then performed using acetate buffer solution as a blank.

2.8. Antioxidant activity determination

2.8.1. Determination of DPPH radical scavenging activity

DPPH radical scavenging activity of Maillard conjugates was determined according to the method of Dong et al. [8] and Zhao et al. [29] with some modifications. Briefly, a 1 mL aliquot of all solutions was mixed with 4 mL of 0.1 M DPPH solution in 15 mL Greiner centrifuge tubes (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd., Singapore). The sample solutions were mixed well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark before measuring the absorbance at 517 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Research Laboratory (Europe) Ltd., Manchester, UK). The percentage of scavenging activity was calculated following Eq. (3), and the DPPH scavenging activity was expressed as µg Trolox equivalent per mL of Maillard conjugate solution using a Trolox standard curve (µg mL−1).

| (3) |

where Abs control = absorbance value of 0.1 M DPPH

Abs sample = absorbance value of 0.1 M DPPH containing the sample.

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the nanoparticles was determined following the method modified from Mi et al. [30]. Freeze-dried nanoparticles were dispersed in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mg mL−1. Then, 1 mL of the nanoparticle dispersion was mixed with 4 mL of 0.1 M DPPH. All nanoparticle dispersions were then measured, and the DPPH scavenging activity was calculated as described above and expressed as µg Trolox equivalent per mg of nanoparticles (µg mg−1).

2.8.2. Determination of reducing power

The reducing power of samples was determined using the method modified from Zhao et al. [29]. Before analysis, the freeze-dried nanoparticles were dispersed in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mg mL−1. Then, 1 mL of Maillard conjugate solutions or nanoparticle dispersions were transferred into a 15 mL Greiner centrifuge tube (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd., Singapore), with 2 mL of phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 2 mL of 1% (w/v) potassium ferricyanide subsequently added. The sample was incubated at 50 °C in a water bath for 20 min, followed by addition of 2 mL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid. The mixture was then centrifuged at 805×g for 10 min. Approximately 2 mL of the supernatant was collected and mixed with 2 mL of distilled water and 0.4 mL of 0.1% (w/v) ferric chloride. After 10 min incubation in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance of the samples was measured at 700 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Research Laboratory (Europe) Ltd., Manchester, UK). The reducing power was reported as μg Trolox equivalent per mL or mg for Maillard reaction products (μg mL−1) and nanoparticles (μg mg−1), respectively.

2.9. Nanoparticle yield calculation

After freeze-drying, the nanoparticles were collected and weighed accurately [18]. Percentage yield (%) was then calculated as follows:

| (4) |

2.10. Particle size measurement

The nanoparticles were dispersed in an acetate buffer solution at a concentration of 0.05 mg mL−1. The dispersion samples (∼1 mL) were placed into the sample cell and particle size and particle distribution were measured at 25 °C using a NanoBrook Omni particle sizer analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, NY, USA).

2.11. Scanning electron microscope

The morphological characteristics of selected nanoparticles both as powder and suspension were observed following the method modified from Ruiz-Pulido et al. [31] using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Quanta 450, FEI Co., OR, USA). Before analysis, sample suspensions were prepared by dispersing the freeze-dried nanoparticles in absolute ethanol at a concentration of 0.05 mg mL−1. The dispersions were then sonicated (Elma Transsonic T 460/H, Elma GmbH & Co KG, Singen, Germany) at room temperature for 30 min. Approximately 100 μL of the suspension was deposited onto a small glass slide (1 × 1 cm) and the solvent was evaporated at room temperature before coating with gold. For the powder samples, freeze-dried nanoparticles (∼1.0 mg) were sprinkled onto a small glass slide and then coated with gold. The external structure and shape of the nanoparticles were then observed using an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Nanoparticle images were acquired at magnifications of 60,000 × and 30,000 × for powder and suspension, respectively.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate, with data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the SPSS statistical software package (Thaisoftup Co., Ltd., Thailand). Duncan’s Multiple Range Test was used to determine mean differences at the P < 0.05 level to denote statistical significance.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose at different temperatures and times

3.1.1. FT-IR spectra

FT-IR analysis was performed to investigate structural changes of chitosan by Maillard conjugation with glucose, with FT-IR spectra of chitosan, glucose and MRPs shown in Fig. 1A. Characteristic transmittance peaks of chitosan observed at 1646, 1558 and 1260 cm−1 were assigned to amide I (C O stretching), amide II (N—H bending) and amide III (C—N stretching), respectively, while CH2 bending was seen at 1407 cm−1 and C—O stretching was observed at 1070 and 1026 cm−1 [32], [33]. Characteristic FT-IR spectra of glucose transmittance peaks at 1461 and 1382 cm−1 were assigned to CH2 bending and O—H bending, respectively. The spectra also showed a peak at 1151 cm−1, assigned to asymmetric stretching of the C—O—C bridge. The transmittance peak at 1079 was attributed to C—O stretching [34]. Transmittance peaks of physical mixtures between chitosan and glucose showed the main characteristic peaks of both substances. Peaks for amides I and II were observed at 1638 and 1560 cm−1, respectively, with the CH2 bending peak at 1416 cm−1 shifted from the original chitosan (1407 cm−1) and glucose (1461 cm−1). The C—O stretching peaks of the saccharide chain were observed at shifted positions from the original chitosan but close to the original glucose at 1078 and 1032 cm−1.

Fig. 1.

FT-IR spectra of chitosan, glucose, their mixture and MRPs (A). Zeta- potential (B) of ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose at various temperatures (60, 70 and 80 °C) and ultrasonic times (0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min). The letters a-g indicated the significant difference between samples with different temperatures and times.

The spectra of ultrasound-assisted MRPs showed an increase in the intensity of amide I (1642 cm−1) due to generation of Amadori compounds containing the carbonyl structure (C O) [15]. Likewise, increased intensity of amide II (1559 cm−1) and C—O stretching (1078 and 1032 cm−1) were observed compared with their physical mixtures. This indicated that changes in the structure of the original chitosan resulted from glycation by reacting with glucose. Increased intensities of amide II and C—O stretching were also reported for chitosan-sugar derivatives conjugated by the Maillard reaction [14], [35], [36]. An increase in − CH2 chain association at 1415 cm−1 of ultrasound-assisted chitosan-glucose conjugates compared to the unconjugated mixture confirmed incorporation of glucose in the chitosan molecules during the Maillard reaction [37].

3.1.2. Zeta-potential

Chitosan is a polycationic biopolymer that can be protonated in weak organic acid solutions with pH lower than its pKa (∼6.3–6.5). The surface charge density of a chitosan solution can be detected by measuring its zeta-potential [2], [3]. Our previous study identified zeta-potential measurement as an effective technique to monitor the extent of the Maillard reaction [15]. Zeta-potentials of the solutions of MRPs obtained from ultrasound-assisted conjugation between chitosan and glucose at different temperatures and times are shown in Fig. 1B.

As expected, the zeta-potential values of all solutions showed a positive charge that significantly decreased with increasing reaction temperature and time (P ≤ 0.05). The initial chitosan-glucose solution (0 min ultrasonic time) had zeta-potential of 42.45 ± 1.28 mV. This value decreased to 34.95 ± 0.92, 31.10 ± 1.64 and 22.09 ± 0.21 mV after Maillard conjugation for 60 min at 60, 70 and 80 °C, respectively. MRPs development is associated with the loss of free amino/amine groups (/) of reactant molecules. Phisut and Jiraporn [13] reported reduction in free amino group content during extended heating of chitosan-sugar solutions at 100 °C for 7 h, while loss of free amino acid was observed in a whey protein isolate-inulin system with prolonged heating from 0 to 6 h at 70 °C [38]. The free amino group was lost during the ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction of pea protein isolate-saccharide solutions at 50–90 °C for 35 min as reported by Zhao et al. [29]. For chitosan, reduction in the available positively charged units occurred, with a decrease in the zeta-potential of the MRPs solutions [15]. This result was consistent with Li et al. [39] who reported a reduction in the zeta-potential of chitosan-soy protein isolate-gum Arabic solution after conjugating at 80 °C for 12 h.

3.1.3. Color indices

The formation of chitosan-glucose Maillard reaction products (MRPs) in ultrasound-assisted conjugation can be also traced by measuring the color of the samples. The CIE color indices denoted as L* (dark/light), a* (red/green), and b* (yellow/blue) were recorded. These color indices were then used to calculate the browning index (BI, Eq. (1)) and total color difference (ΔE, Eq. (2)). Changes in all color indices in chitosan-glucose solutions are considered significant indicators of the occurrence and extent of the Maillard reaction [8].

Fig. 2A shows the b* values of chitosan-glucose MRPs obtained from ultrasonic treatment at 60, 70 and 80 °C for 0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. The b* values showed positive intensity that represented yellow color, which is dramatically relevant to color formation in the Maillard reaction. Results showed that b* values of ultrasound-treated chitosan-glucose solutions were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) dependent on temperature and time and clearly observed at 80 °C. At 60 and 70 °C, b* values of samples at all reaction times were not significantly different (P > 0.05), ranging from 2.49 to 2.96. However, these b* values were significantly different from the initial chitosan-glucose mixture (0 min). At 80 °C, a significant increase in the b* value of MRPs with increasing reaction time was observed (P ≤ 0.05), with maximum b* value of 4.12 ± 0.07 recorded at 60 min. Increase in temperature enhanced higher Maillard-type conjugation rate that consistent with the previous works [10], [29].

Fig. 2.

Color b* value (A), browning index (B) and ΔE (C) of ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose at various temperatures (60, 70 and 80 °C) and ultrasonic times (0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min). The letters a-h indicated the significant difference between samples with different temperatures and times.

For the BI (Fig. 2B), influence of ultrasonic time and reaction temperature on the extent of Maillard conjugation was significant (P ≤ 0.05). Consistent with the b* value, lower BI values were obtained in chitosan-glucose solutions treated at low temperature and short ultrasonic time. At 60 °C, a significant increase in BI was observed at 30 min sonication compared with the initial solution. This indicated a lower rate of brown color development compared with 70 and 80 °C for color change in BI at 15 min reaction time. The highest BI of 4.49 ± 0.56 was obtained for ultrasound-assisted Maillard conjugation of chitosan-glucose at 80 °C for 60 min, with color changes being faster at high temperature (80 °C) than at low temperature (60 °C) because of the increased reaction rate between chitosan and glucose molecules. Open-chain molecules of reactive glucose have also been reported to increase in volume with increasing temperature, facilitating the extent of Maillard conjugation [40].

The ultrasound-treated chitosan-glucose solutions were compared with the untreated solution. The ΔE value was calculated by taking the CIE L*, a* and b* values (99.60, −0.10 and 1.05, respectively) of the untreated solution as a reference. The ΔE value of sonicated solutions significantly increased (P ≤ 0.05) when ultrasonic temperature and time increased (Fig. 2C). The ΔE values of all ultrasound-treated chitosan-glucose solutions were higher than 1.0, indicating that the discrimination of sample color was perceptible by the naked eye [41]. This result supported the occurrence of a reaction between free amino groups of chitosan and the reducing end carbonyl group of glucose that increased color intensity. The greatest change of color was observed in the chitosan-glucose ultrasound-assisted Maillard conjugate solution at 80 °C of reaction temperature and 60 min of ultrasonic time (ΔE ∼ 3.24).

3.1.4. UV–Vis absorbance

The Maillard reaction involves different stages, mainly the development of UV-absorbing intermediate compounds and the formation of final brown-colored reaction products, which can be monitored by measuring the absorbances at 294 (A294) and 420 nm (A420), respectively [11]. The absorbance values at both wavelengths increased with reaction temperature and ultrasonic time (Fig. 3A and B). These results were consistence with the measurement of zeta-potential and color indices previously described (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2) and concurred with the results in previous works. Yu et al. [10] reported the higher increase of absorbance values in ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between xylose and lysine than those in thermal reaction. In addition, increase in UV absorbance intensity with temperature and time was also found in the ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between pea protein isolate and xylo-oligosaccharide [29]. Highest values of UV absorbance were observed in the MRPs solution ultrasound-treated chitosan-glucose Maillard reaction at 80 °C for 60 min which of 0.833 ± 0.009 and 0.173 ± 0.003 for A294 and A420 nm, respectively (Fig. 3A and 3B). The continuous increase of UV absorbance at longer ultrasonic times and higher values of A294 than A420 indicated an incomplete Maillard reaction [11], [15]. Applications of MRPs in foods may not require excess brown color products, to avoid adversely affecting the final product appearance. Therefore, proper ultrasonic time and temperature should be selected for each food application.

Fig. 3.

Absorbance values at 294 (A) and 420 nm (B), DPPH scavenging activity (C) and reducing power (D) of ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose at various temperatures (60, 70 and 80 °C), ultrasonic times (15, 30, 45 and 60 min). The letters a-k indicated the significant difference between samples with different temperatures and times.

3.1.5. Antioxidant activity

The Maillard reaction is an effective modification method for enhancing the antioxidant activity of chitosan. DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power assays were selected to evaluate the influence of reaction temperature and ultrasonic time on the antioxidant activity of chitosan-glucose MRPs. The DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power of untreated and ultrasonic-treated chitosan-glucose solutions at various temperatures (60, 70 and 80 °C) and ultrasonic times (15, 30, 45 and 60 min) are shown in Fig. 3C and 3D. Untreated chitosan-glucose solution (0 min ultrasonic time) exhibited some antioxidant ability either by DPPH scavenging activity (16.45 ± 2.12 μg Trolox mL−1) or reducing power (8.51 ± 0.42 μg Trolox mL−1), concurring with the studies of Nooshkam et al. [12] and Hafsa et al. [37]. The scavenging and reductive activities of untreated solutions resulted from the hydrogen and electron-donating properties of chitosan molecules. Hydroxyl groups () in the polysaccharide unit, free amine groups (), and protonated amino residues () were responsible for the antioxidant activities of chitosan [42], [43].

Significant increases in DPPH scavenging activity (Fig. 3C) and reducing power (Fig. 3D) with extended ultrasonic time were observed at all reaction temperatures, while antioxidant activities of chitosan-glucose MRPs dramatically increased as the reaction temperature increased (P ≤ 0.05). The greatest values of DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power were 34.49 ± 1.43 and 20.18 ± 0.37 μg Trolox mL−1, respectively, at 80 °C of reaction temperature and 60 min of ultrasonic time. These results concurred with previous reports of increased DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power of chitosan-based MRPs when either prolonging conjugation time or increasing reaction temperature [44], [45]. Improvement in the antioxidant activity of chitosan from conjugation with glucose was attributed to the reducing effect of hydroxyl or amine groups in pyranose rings of the MRPs, the hydrogen donating activity of both intermediate compounds and final stage MRPs named as reductones and melanoidins, respectively [12], [37], [41].

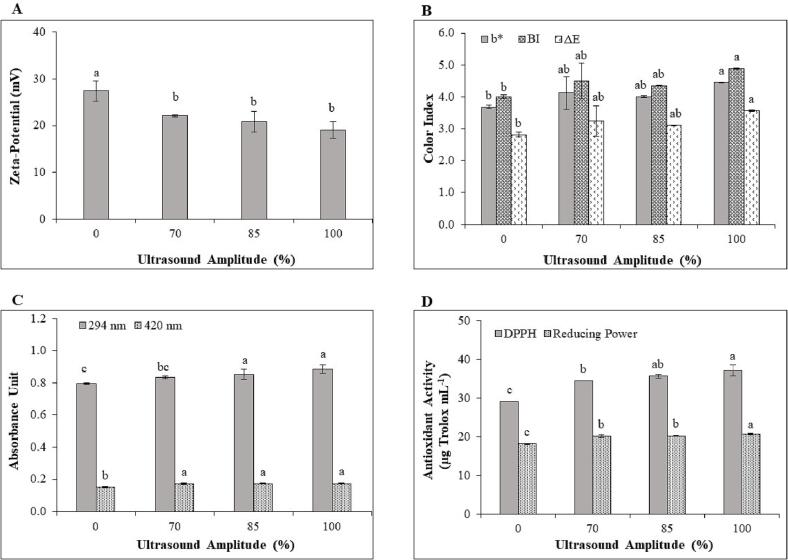

3.2. Influence of amplitude on ultrasound-assisted Maillard reactions between chitosan and glucose

The influence of ultrasound amplitude on the extent of the Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose was also investigated. Applying ultrasound at 70–100% amplitude did not impact zeta-potential (Fig. 4A). However, a higher reduction in the zeta-potential of all ultrasound-assisted Maillard conjugation samples was observed than thermal-induced Maillard reaction products (0% amplitude) at the same temperature and time (80 °C and 60 min). Using ultrasound amplitude in the range of 70 to 100% did not influence color indices of the MRPs solutions (Fig. 4B). However, using 100% ultrasound amplitude significantly increased the color intensity of MRPs solutions compared with thermal-induced MRPs.

Fig. 4.

Zeta-potential (A), color index (B), UV absorbances (C) and antioxidant activity (D) of ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction between chitosan and glucose at various ultrasound amplitudes (0, 70, 85, and 100%). The letters a-c indicated the significant difference between samples with different ultrasound amplitudes.

The A294 of the ultrasound-assisted chitosan-glucose MRPs solution significantly increased when ultrasound amplitude was increased from 70 to 85%; however, further increasing the ultrasound amplitude to 100% did not affect the A294 of chitosan-glucose MRPs solution. Ultrasound amplitude in the range 70–100% did not impact the A420 of ultrasound-assisted chitosan-glucose MRPs solution (Fig. 4C). Different results were reported by Corzo-Martínez et al. [46], who found a significant increase in A294 and A420 of lysine-glucose solution treated by ultrasound at 50 and 70% amplitude. Using different reactant types and volumes, ultrasound power and probe surface area all contributed toward variability in the results. Comparison of ultrasound-assisted and thermal-induced MRPs found no significant difference between A294 at 70% amplitude (P > 0.05) but significant differences at both 85 and 100% amplitudes. Significant differences in A420 between thermal-induced MRPs and ultrasound-assisted MRPs at all amplitude levels were observed (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4C). Applying ultrasound significantly increased the contact area of chitosan and glucose, with enhanced intermolecular motion between the amine groups and carbonyl residues, resulting in acceleration of the Maillard conjugation rate compared to thermal-induced MRPs [41], [46].

Antioxidant activities of ultrasound-assisted chitosan-glucose MRPs at all amplitudes were significantly higher (P ≤ 0.05) than thermal-induced MRPs (0% amplitude) due to development of more MRPs, as previously described (Fig. 4D). No significant differences (P > 0.05) were observed when increasing ultrasound amplitude from 70 to 85% for both DPPH scavenging activity (∼34.50 and ∼ 35.64 μg Trolox mL−1) and reducing power (∼20.18 and ∼20.25 μg Trolox mL−1). However, the highest antioxidant activity (P ≤ 0.05) was recorded when the ultrasound amplitude increased to 100%, at ∼ 37.14 and ∼ 20.75 μg Trolox mL−1 for DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power, respectively (Fig. 4D). Increasing ultrasound amplitude increases the cavitation intensity within a liquid [47]. This results in a higher conjugation degree for chitosan-glucose treated with high amplitude percentage, consequently providing higher antioxidant activity. To maintain and/or prolong the early step of the Maillard reaction, a low ultrasonic amplitude of 70% was chosen for further experiments.

3.3. Ultrasound-assisted chitosan-glucose MRPs-based nanoparticles

3.3.1. FT-IR analysis and percentage yield

Fig. 5 shows the FT-IR spectra of powder tripolyphosphate (TPP), freeze-dried MRPs and MRPs/TPP nanoparticles formed at pH 2.0, 4.0 and 6.0. Characteristic transmittance peaks of TPP (Fig. 5A) observed at 1212–1202, 1102–1095 and 908–899 cm−1 were assigned to the stretching vibrations of P O, −PO3 group and the P—O—P bridge, respectively [48], [49]. When comparing the FT-IR spectra of nanoparticles with MRPs spectra at pH 4.0 and 6.0 (Fig. 5B and C, respectively), electrostatic interactions between protonated amine (NH3+) on chitosan molecules in MRPs and negatively charged residue in TPP molecules were noted. Transmittance peaks at 908–899 cm−1 characteristic of TPP molecules (Fig. 5A) were shifted to 896–892 cm−1 and 892–889 cm−1 in nanoparticles prepared from MRPs at pH 4.0 and 6.0, respectively, confirming the incorporation of TPP into the nanoparticles by reacting with MRPs via ionic gelation [49]. Similarly, intensity of the amide I peak (1561–1559 cm−1) in MPRs at both pH values decreased due to its involvement in the reaction. A new peak between 1231 and 1205 cm−1, related to stretching vibrations of P O in the TPP chain, was observed in nanoparticle samples and identified as the formation of electrostatic interactions between MRPs and TPP [48], [49]. This peak was not very pronounced in the spectrum of the nanoparticle sample formed with TPP at pH 2.0 because the low density of negatively charged groups in TPP resulted in low crosslinking degree. Likewise, low intensity was also observed for MRPs pH 6.0 compared to pH 4.0 due to the low population of protonated amine available for interaction [48], [50]. These results concurred with the percentage yield of nanoparticles (Fig. 5D), with solution pH influencing production yield. Increasing the pH of the TPP solution from 2.0 to 4.0 increased the percentage yield but the yield decreased at further pH increase to 6.0. The lowest percentage yield was observed in nanoparticles prepared using MRPs and TPP solutions at pH 6.0, while the highest percentage yield was recorded for nanoparticles prepared using MRPs and TPP solutions at pH 4.0. These results concurred with Mattu et al. [51] and Karimi et al. [52] who reported that chitosan and TPP solutions at mild acidic pH were optimal for nanoparticle preparation.

Fig. 5.

FT-IR spectra of tripolyphosphate (A) at pH 2.0, 4.0 and 6.0 (TPP2, TPP4 and TPP6, respectively), nanoparticles prepared from MRPs pH 4.0 (B) and pH 6.0 (C) with TPP solution at various pH (PT2 = pH 2.0, PT4 = pH 4.0 and PT6 = pH 6.0). Particle yield (D) of nanoparticles prepared from Maillard reaction products pH 4.0 and pH 6.0 with TPP solution at various pH. The letters a-f indicated the significant difference between samples.

3.3.2. Zeta-potential

The pH of solution is very important for ionic gelation between chitosan and TPP. Nanoparticles were formed by mixing chitosan-based MRPs prepared at pH 4.0 and 6.0 with TPP solution at various pH values (2.0, 4.0 and 6.0). Surface charge of the nanoparticles is an important factor in determining the stability of nanoparticulate suspensions. More positively charged nanoparticles show increased self-repulsion, consequently making the system more stable. The surface charge density is reflected by zeta-potential value. Fig. 6A shows that the zeta-potentials of all nanoparticles had positive charge (∼4.2 to 26.4 mV), with nanoparticles prepared from MRPs at pH 4.0 having significantly higher values than pH 6.0 (P ≤ 0.05). At higher pH values, the NH3+ groups on the chitosan molecules were neutralized, resulting in decreased zeta-potential [28], [53], [54]. Decreased zeta-potential of nanoparticles was observed in both MRPs solution as the pH value of TPP solution increased from 2.0 to 6.0 (26.4 to 15.5 mV and 14.0 to 4.2 mV for MPRs pH 4.0 and 6.0, respectively). Similar results were reported by Du et al. [55]. These changes were due to two causes. The first was a decrease in the degree of protonation of the primary amine groups (NH2) of chitosan in MRPs when the solution pH was less than its pKa (∼6.3–6.5), and the second was an increase in the charge density of TPP with increasing pH higher than its pKa, reported at around 2.3 [50], [56].

Fig. 6.

Zeta-potential (A) and particle size (B) of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles prepared from chitosan-MRPs and tripolyphosphate solutions at different pHs. The letters a-f indicated the significant difference between samples.

3.3.3. Particle size

As summarized in Fig. 6B, the mean particle size of nanoparticles prepared using MRPs at pH 4.0 significantly increased from 393.5 ± 6.6 to 830.5 ± 8.5 nm with increasing pH of TPP solution from 2.0 to 6.0 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively. Similarly, the mean particle size of nanoparticles prepared from MRPs at pH 6.0 also significantly increased (540.9 ± 14.3 to 1077.6 ± 34.6 nm) when increasing the pH of TPP solution from pH 2.0 to 6.0 (P ≤ 0.05). The smallest particle size was observed for nanoparticles produced using the TPP solution at pH 2.0, whereas the TPP solution at pH 6.0 produced the largest nanoparticles for both MRPs at pH 4.0 and pH 6.0. It is probably due to the impact of solution pH on the electronegative potential of TPP molecules. At pH 2.0, TPP had less negatively charged density to interact with the positively charged residue in chitosan molecules. Thus, few protonated amine groups in chitosan reacted with TPP, resulting in the fabrication of small nanoparticles (Fig. 6B). By contrast, TPP had higher negative charge density at pH 6.0 that reacted with free protonated amine groups of chitosan and also with the protonated amine sites of already formed nanoparticles, leading larger-sized nanoparticles [57], [58].

When comparing the two different initial pH values of MRPs solutions, larger-sized nanoparticles were obtained at higher pH (pH 6.0) for all TPP solutions (Fig. 6B). Increase in the size of nanoparticles with increasing pH of the MRPs solution was due to aggregation or folding of the chitosan molecules [51]. The repulsive forces between chitosan molecules reduced in a less acidic solution as a result of decreased protonation of the amine groups. Therefore, fewer protonated amine groups to react with TPP resulted in larger-sized nanoparticles [53], [54], [57]. The pH values of both chitosan-based MRPs and TPP solutions impacted the particle size of chitosan-based MRPs-TPP nanoparticles.

3.3.4. Nanoparticle morphology

The morphological characteristics of nanoparticles prepared from chitosan-based MRPs (pH 4.0) with TPP solution at different pH (pH 2.0, 4.0 and 6.0) were evaluated in both powder and dispersion forms using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), as shown in Fig. 7. The characteristic morphology was used to determine the successful fabrication of MRPs-based chitosan nanoparticles. The morphology of chitosan-MRPs-based nanoparticles was influenced by the pH of TPP solution. Small particles with reduced aggregation were observed in the powder form at lower pH values of TPP solution (Fig. 7A), while nanoparticles prepared at higher pH values (Fig. 7B and 7C) were larger and more aggregated. Nearly spherical, small and low polydispersity was observed for the nanoparticles prepared at lower pH values of TPP solution (Fig. 7D), while irregular shapes, larger size and heterogeneous particles were obtained at higher pH values of TPP solution (Fig. 7E and F). These results were consistent with particle size measurements (Fig. 6B) and concurred with previous studies [51], [53].

Fig. 7.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticle powder (A, B and C) and dispersion (D, E and F) prepared from chitosan-MRPs pH 4.0 with tripolyphosphate solution pH 2.0 (A and D), pH 4.0 (B and E) and pH 6.0 (C and F).

3.3.5. Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activities of nanoparticles prepared using chitosan-based MRPs solutions at pH 4.0 and 6.0 with TPP solutions at various pH values were evaluated for DPPH radical scavenging activity (Fig. 8A) and reducing power (Fig. 8B). Results showed that all MRPs-based chitosan nanoparticles had the highest antioxidant activity when prepared with TPP at pH 2.0, deduced from both DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power (P ≤ 0.05). Antioxidant activity decreased when further raising the pH of TPP to 4.0 and 6.0. Antioxidant activity of the prepared nanoparticles occurred due to the scavenging and reducing activities of the hydroxyl groups in the polysaccharide unit and residual free protonated amine groups (NH3+) of chitosan-based MRPs [46], [59]. Results concurred with the zeta-potential measurement (Fig. 6A) showing that value decreased with increasing pH of the TPP solution. However, lower activity was observed for the nanoparticles prepared using MRPs at pH 4.0 than pH 6.0 at all TPP solutions for both DPPH radical scavenging activity (Fig. 8A) and reducing power (Fig. 8B) because the increase in MRPs resulted in higher antioxidant activity [15], [60].

Fig. 8.

Reducing power (A) and DPPH scavenging activity (B) of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles prepared from chitosan- MRPs with tripolyphosphate solutions at different pH. The letters a-e indicated the significant difference between samples for each antioxidant activity indicator.

3.4. Characteristics of MRPs-based nanoparticles prepared from ultrasound-assisted and thermal-treated MRPs

The formation and antioxidant activity of chitosan nanoparticles obtained from ultrasound-assisted MRPs was also compared with nanoparticles prepared from thermal-treated MRPs and chitosan-glucose physical mixtures. Nanoparticles were prepared at pH 4.0 for both chitosan and TPP solutions. Nanoparticles prepared using physical mixtures had higher zeta-potential (22.6 ± 1.2 mV) and smaller size (400.4 ± 13.1 nm) than those prepared from chitosan-based MRPs. Ultrasound-assisted and thermal-treated MRPs provided nanoparticles with insignificantly different zeta-potential and particle size (19.7 ± 1.3 mV and 454.5 ± 4.5 nm; and 21.0 ± 0.2 mV and 445.3 ± 20.8 nm, respectively) (Fig. 9A). As previously described (Section 3.1.2.), conjugation of chitosan by glucose via the Maillard reaction resulted in a decrease in zeta-potential. Consequently, the repulsive force between chitosan molecules was reduced due to a decrease in the protonation of amine groups. Therefore, there were fewer protonated amine groups to react with TPP, resulting in larger-sized nanoparticles [53], [54], [57].

Fig. 9.

Zeta-potential and particle size (A), and antioxidant activity (B) of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles prepared from ultrasound-assisted MRPs (US-MRPs), thermal-treated MRPs (TH-MRPs), and chitosan-glucose physical mixture (PH-MIX). The letters a-c indicated the significant difference between nanoparticle samples.

The DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power assays were used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of nanoparticles prepared from ultrasound-assisted MRPs, thermal-treated MRPs and chitosan-glucose physical mixture (Fig. 9B). Nanoparticles prepared from physical mixtures had significantly lower antioxidant activity, as indicated by both scavenging activity and reducing power (0.33 and 0.47 μg Trolox mg−1, respectively) compared to MRPs-based nanoparticles. Significantly higher DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power of nanoparticles prepared from ultrasound-assisted MRPs (0.98 and 1.64 μg Trolox mg−1, respectively) than from thermal-treated MRPs was observed (0.66 and 0.96 μg Trolox mg−1, respectively). Results suggested that the antioxidant activity of nanoparticles depended on the antioxidant activity of chitosan-based substances. In a similar vein, Zhang et al. [18] reported that crosslinking with TPP did not affect the antioxidant activity of chitosan. The dramatically improved antioxidant activity of chitosan nanoparticles by pre-conjugation with glucose via the Maillard reaction was a significant finding. Ultrasound-assisted conjugation produced MRPs with higher antioxidant activity compared with the thermal-treated reaction, consequently producing nanoparticles with higher antioxidant activity.

4. Conclusions

Chitosan-glucose MRPs with improved antioxidant activity were successfully prepared using the ultrasound-assisted process as indicated by FT-IR analysis, zeta-potential determination and color measurement results. Reaction temperature and ultrasonic time dramatically affected the formation rate and property of the reaction products. Temperature, time and amplitude of 80 °C, 60 min and 70%, respectively were selected as the optimal condition to produce MRPs with the highest antioxidant activity. The pH of both MRPs and tripolyphosphate solutions significantly influenced the fabrication and characteristics of nanoparticles. Using chitosan-glucose MRPs at pH 4.0 and TPP solution at the same pH generated the nanoparticles with antioxidant enhancement (1.6 and 1.2 μg Trolox mg−1 for reducing power and DPPH scavenging activity, respectively), highest percentage yield (∼59%), intermediate particle size (∼447 nm) and zeta-potential ∼19.6 mV. However, the stability of these nanoparticles in different media, solvent types, pH values or saline solutions requires further study. In addition, future works related to the application of these nanoparticles as delivery matrices, novel emulsion stabilizer, and functional food ingredient are recommended.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Supapit Viturat: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Masubon Thongngam: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Namfone Lumdubwong: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Weibiao Zhou: Methodology, Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Utai Klinkesorn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the financial support from the Kasetsart University Institute for Advanced Studies (KUIAS) under the Reinventing University Program and the Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI) under the project of Development of Advance Researcher Competence System for Competitiveness in Agriculture and Food (No. FF(KU) 25.64).

Contributor Information

Weibiao Zhou, Email: weibiao@nus.edu.sg.

Utai Klinkesorn, Email: utai.k@ku.ac.th.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Hafsa J., Smach M.A., Mrid R.B., Sobeh M., Majdoub H., Yasri A. Functional properties of chitosan derivatives obtained through Maillard reaction: a novel promising food preservative. Food Chem. 2021;349 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klinkesorn U. The role of chitosan in emulsion formation and stabilization. Food Rev. Int. 2013;29:371–393. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2013.818013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q.Z., Chen X.G., Liu N., Wang S.X., Liu C.S., Meng X.H., Liu C.G. Protonation constants of chitosan with different molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006;65:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang H., Zhang Y., Zhou F., Guo J., Tang J., Han Y., Li Z., Fu C. Preparation, bioactivities and applications in food Industry of chitosan-based Maillard products: a review. Molecules. 2021;26:166. doi: 10.3390/molecules26010166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nooshkam M., Varidi M., Bashash M. The Maillard reaction products as food-born antioxidant and antibrowning agents in model and real food systems. Food Chem. 2019;275:644–660. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao X., Feng T., Liu E., Shan P., Zhang Z., Liao L., Ma H. Ougan juice debittering using ultrasound-aided enzymatic hydrolysis: Impacts on aroma and taste. Food Chem. 2021;345 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu H., Zhong Q., Liu Y., Guo Y., Xie Y., Zhou W., Yao W. Recent advances of ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Z.Y., Liu W., Zhou Y.J., Ren H., Li M.Y., Liu Y. Effects of ultrasonic treatment on Maillard reaction and product characteristics of enzymatic hydrolysate derived from mussel meat. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019;42:e13206. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z., Han F., Sui X., Qi B., Yang Y., Zhang H., Wang R., Li Y., Jiang L. Effect of ultrasound treatment on the wet heating Maillard reaction between mung bean [Vigna radiate (L.)] protein isolates and glucose and on structural and physico-chemical properties of conjugates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016;96:1532–1540. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu H., Seow Y.-X., Ong P.K.C., Zhou W. Effects of high-intensity ultrasound on Maillard reaction in a model system of d-xylose and l-lysine. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosaraju S.L., Weerakkody R., Augustin M.A. Chitosan-glucose conjugates: influence of extent of Maillard reaction on antioxidant properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:12449–12455. doi: 10.1021/jf103484z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nooshkam M., Falah F., Zareie Z., Yazdi F.T., Shahidi F., Mortazavi S.A. Antioxidant potential and antimicrobial activity of chitosan–inulin conjugates obtained through the Maillard reaction. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019;28:1861–1869. doi: 10.1007/s10068-019-00635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phisut N., Jiraporn B. Characteristics and antioxidant activity of Maillard reaction products derived from chitosan-sugar solution. IFRJ. 2013;20:1077–1085. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gullon B., Montenegro M.I., Ruiz-Matute A.I., Cardelle-Cobas A., Corzob N., Pintado M.E. Synthesis, optimization and structural characterization of a chitosan–glucose derivative obtained by the Maillard reaction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;137:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaewtathip T., Wattana-Amorn P., Boonsupthip W., Lorjaroenphon Y., Klinkesorn U. Maillard reaction products-based encapsulant system formed between chitosan and corn syrup solids: Influence of solution pH on formation kinetic and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022;393 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangun H., Tandiono S., Arianto A. Preparation and evaluation of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles suspension as an antibacterial agent. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2018;8:147–156. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2018.81217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harish V., Ansari M.M., Tewari D., Gaur M., Yadav A.B., García-Betancourt M.-L., Abdel-Haleem F.M., Bechelany M., Barhoum A. Nanoparticle and nanostructure synthesis and controlled growth methods. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:3226. doi: 10.3390/nano12183226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H., Zhang Y., Bao E., Zhao Y. Preparation, characterization and toxicology properties of α- and β-chitosan Maillard reaction products nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;89:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agnihotri S.A., Mallikarjuna N.N., Aminabhavi T.M. Recent advances on chitosan-based micro- and nanoparticles in drug delivery. J Control Release. 2004;100:5–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.P.R. Deshmukh, A. Joshi, C. Vikhar, S.S. Khdabadi, M. Tawar, Current applications of chitosan nanoparticles, Sys. Rev. Pharm. 13 (2022) 685-693, https://doi.org/10.31858/ 0975-8453.13.10.685-693.

- 21.G. Maleki E.J. Woltering M.R. Mozafari Applications of chitosan-based carrier as an encapsulating agent in food industry Trends Food Sci Technol. 120 2022 88 99 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.01.001.

- 22.Amiri A., Mousakhani-Ganjeh A., Amiri Z., Guo Y., Singh A.P., Kenari R.E. Fabrication of cumin loaded-chitosan particles: Characterized by molecular, morphological, thermal, antioxidant and anticancer properties as well as its utilization in food system. Food Chem. 2020;310 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He B., Ge J., Yue P., Yue X.Y., Fu R., Liang J., Gao X. Loading of anthocyanins on chitosan nanoparticles influences anthocyanin degradation in gastrointestinal fluids and stability in a beverage. Food Chem. 2017;221:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.L. Yan R. Wang H. Wang K. Sheng C. Liu H. Qu A. Ma L. Zheng Formulation and characterization of chitosan hydrochloride and carboxymethyl chitosan encapsulated quercetin nanoparticles for controlled applications in foods system and simulated gastrointestinal condition Food Hydrocolloids. 84 2018 450 457 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/ j.foodhyd.2018.06.025.

- 25.Bagheri R., Ariaii P., Motamedzadegan A. Characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with nettle essential oil. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021;15:1395–1402. doi: 10.1007/s11694-020-00738-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hadidi M., Pouramin S., Adinepour F., Haghani S., Jafari S.M. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with clove essential oil: characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;236 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sang Z., Qian J., Han J., Deng X., Shen J., Li G., Xie Y. Comparison of three water-soluble polyphosphate tripolyphosphate, phytic acid, and sodium hexametaphosphate as crosslinking agents in chitosan nanoparticle formulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;230 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hejjaji E.M.A., Smith A.M., Morris G.A. Designing chitosan-tripolyphosphate microparticles with desired sizefor specific pharmaceutical or forensic applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;95:564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao S., Huang Y., McClements D.J., Liu X., Wang P., Liu F. Improving pea protein functionality by combining high-pressure homogenization with an ultrasound-assisted Maillard reaction. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;126 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Y. Mi, Y. Chen, G. Gu, Q. Miao, W. Tan, Q. Li, Z. Guo, New synthetic adriamycin-incorporated chitosan nanoparticles with enhanced antioxidant, antitumor activities and pH-sensitive drug release, Carbohydr. Polym. 273 (2021) 118623, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118623. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Ruiz-Pulido G., Quintanar-Guerrero D., Serrano-Mora L.E., Medina D.I. Triborheological analysis of reconstituted gastrointestinal mucus/chitosan:TPP nanoparticles system to study mucoadhesion phenomenon under different pH conditions. Polymers. 2022;14:4978. doi: 10.3390/polym14224978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhardwaj S., Bhardwaj N.K., Negi Y.S. Effect of degree of deacetylation of chitosan on its performance as surface application chemical for paper-based packaging. Cellulose. 2020;27:5337–5352. doi: 10.1007/s10570-020-03134-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bujňáková Z., Dutková E., Zorkovská A., Baláž M., Kováč J., Kello M., Mojžiš J., Briančin J., Baláž P. Mechanochemical synthesis and in vitro studies of chitosan-coated InAs/ZnS mixed nanocrystals. J. Mater. Sci. 2017;52(2):721–735. [Google Scholar]

- 34.M. Ibrahim, M. Alaam, H. El-Haes, A.F. Jalbout, A. Leon, Analysis of the structure and vibrational spectra of glucose and fructose, Eclet. Quím. 31 (2006) 15-21, https://doi.org/ 10.1590/S0100-46702006000300002.

- 35.Badano J.A., Braber N.V., Rossia Y., Vergara L.D., Bohl L., Porporatto C., Falcone R.D., Montenegro M. Physicochemical, in vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of water soluble chitosan-lactose derivatives. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;224 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.A. Kraskouski, K. Hileuskaya, V. Nikalaichuk, A. Ladutska, V. Kabanava, W. Yao, L. You, Chitosan-based Maillard self-reaction products: formation, characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial potential, Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 4 (2022) 100257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpta.2022.100257.

- 37.Hafsa J., Smach M., Sobeh M., Majdoub H., Yasri A. Antioxidant activity improvement of apples juice supplemented with chitosan-galactose Maillard reaction products. Molecules. 2019;24:4557. doi: 10.3390/molecules24244557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W.-D., Li C., Bin Z., Huang Q., You L.-J., Chen C., Fu X., Liu R.H. Physicochemical properties and bioactivity of whey protein isolate-inulin conjugates obtained by Maillard reaction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;150:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X., Teng J., Huang G., Xu Z., Xiao J. Preparation and characterization of Maillard reaction products from a trinary system composed of the soy protein isolate, chitosan oligosaccharide, and gum Arabic. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021;1:2107–2116. doi: 10.1021/acsfoodscitech.1c00288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uddin Z., Boonsupthip W. Development and characterization of a new nonenzymatic colored time-temperature indicator. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019;42:e13027. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H., Yang J., Zhao Y. High intensity ultrasound assisted heating to improve solubility, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of chitosan-fructose Maillard reaction products. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2015;60:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- 42.F. Avelelas, A. Horta, L.F.V. Pinto, S.C. Marques, P.M. Nunes, R. Pedrosa, S.M. Leandro, Antifungal and antioxidant properties of chitosan polymers obtained from nontraditional Polybius henslowii sources, Mar. Drugs. 17 (2019) 239, https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ md17040239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Pati S., Chatterji A., Dash B.P., Nelson B.R., Sarkar T., Shahimi S., Edinur H.A., Manan T.S.B.A., Jena P., Mohanta Y.K., Acharya D. Structural characterization and antioxidant potential of chitosan by-irradiation from the carapace of Horseshoe crab. Polymers. 2020;12:2361. doi: 10.3390/polym12102361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Affes S., Maalej H., Li S., Abdelhedi R., Nasri R., Nasri M. Effect of glucose substitution by low-molecular weight chitosan-derivatives on functional, structural and antioxidant properties of Maillard reaction-crosslinked chitosan-based films. Food Chem. 2022;366 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu S., Hu J., Wei L., Du Y., Shi X., Zhang L. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Maillard reaction products from xylan with chitosan/chitooligomer/glucosamine hydrochloride/taurine model systems. Food Chem. 2014;148:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corzo-Martinez M., Montilla A., Megias-Perez R., Olano A., Moreno F.J., Villamiel M. Impact of high-intensity ultrasound on the formation of lactulose and Maillard reaction glycoconjugates. Food Chem. 2014;157:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shojaeiarani J., Bajwa D., Holt G. Sonication amplitude and processing time influence the cellulose nanocrystals morphology and dispersion. Nanocomposites. 2020;6:41–46. doi: 10.1080/20550324.2019.1710974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazancova P., Nemethova V., Trelova D., Klescíkova L., Lacík I., Razga F. Dissociation of chitosan/tripolyphosphate complexes into separate components upon pH elevation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;192:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silvestro I., Francolini I., Lisio V.D., Martinelli A., Pietrelli L., Abusco A.S., Scoppio A., Piozzi A. Preparation and characterization of TPP-chitosan crosslinked scaolds for tissue engineering. Materials. 2020;13:3577. doi: 10.3390/ma13163577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laila U., Rochmadi R., Pudjiraharti S. Microencapsulation of purple-fleshed sweet potato anthocyanins with chitosan-sodium tripolyphosphate by using emulsification-crosslinking technique. J. Math. Fund. Sci. 2019;51:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mattu C., Li R., Ciardelli G. Chitosan nanoparticles as therapeutic protein nanocarriers: the effect of pH on particle formation and encapsulation efficiency. Polym. Compos. 2013;34:1538–1545. doi: 10.1002/pc.22415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karimi M., Avci P., Ahi M., Gazori T., Hamblin M.R., Naderi-Manesh H. Evaluation of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles as a p-shRNA delivery vector: formulation, optimization and cellular uptake study. J. Nanopharm. Drug Deliv. 2013;1:266–278. doi: 10.1166/jnd.2013.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katas H., Hussain Z., Ling T.C. Chitosan nanoparticles as a percutaneous drug delivery system for hydrocortisone. J. Nanomater. 2012;372725 doi: 10.1155/2012/372725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang M., Zhang Y., Sun B., Sun Y., Gong X., Wu Y., Zhang X., Kong W., Chen Y. Permeability of exendin-4-loaded chitosan nanoparticles across MDCK cell monolayers and rat small intestine. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2014;37(5):740–747. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du Z., Liu J., Zhang T., Yu Y., Zhang Y., Zhai J., Huang H., Wei S., Ding L., Liu B. Data on the preparation of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles and its entrapment mechanism for egg white derived peptides. Data Brief. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.104841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nasti A., Zaki N.M., Leonardis P., Ungphaiboon S., Sansongsak P., Rimoli M.G., Tirelli N. Chitosan/TPP and chitosan/TPP-hyaluronic acid nanoparticles: systematic optimisation of the preparative process and preliminary biological evaluation. Pharm. Res. 2009;26:1918–1930. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malhotra M., Kulamarva A., Sebak S., Paul A., Bhathena J., Mirzaei M., Prakash S. Ultrafine chitosan nanoparticles as an efficient nucleic acid delivery system targeting neuronal cells. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2009;35:719–726. doi: 10.1080/03639040802526789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.M.J. Masarudin S.M. Cutts B.J. Evison D.R. Phillips P.J. Pigram Factors determining the stability, size distribution, and cellular accumulation of small, monodisperse chitosan nanoparticles as candidate vectors for anticancer drug delivery: application to the passive encapsulation of [14C]-doxorubicin Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2015:8 67–80, https://doi.org/ 10.2147/NSA.S91785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Yen M.-T., Yang J.-H., Mau J.-L. Antioxidant properties of chitosan from crab shells. Polym. Compos. 2008;74:840–844. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wen-qiong W., Yi-hong B., Ying C. Characteristics and antioxidant activity of water-soluble Maillard reaction products from interactions in a whey protein isolate and sugars system. Food Chem. 2013;139:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.