This subanalysis of the Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY) randomized clinical trial investigates if chronic kidney disease–associated composite cardiovascular risk is modifiable with finerenone in the setting of type 2 diabetes.

Key Points

Question

In type 2 diabetes, is chronic kidney disease (CKD)–associated composite cardiovascular risk modifiable with finerenone?

Findings

In this subanalysis of the Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY) randomized clinical trial including 13 026 participants, finerenone was associated with a reduction in composite cardiovascular risk in patients with CKD, type 2 diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate greater than 25, and moderately to severely increased albuminuria. Simulation analysis based on approximately 6.4 million treatment-eligible individuals estimated that over 1 year, finerenone may prevent 38 359 cardiovascular events, which includes the prevention of approximately 14 000 hospitalizations for heart failure.

Meaning

Findings suggest that CKD-associated composite cardiovascular risk is modifiable with finerenone, with a particular population-level benefit in individuals with eGFR of 60 or higher, whose CKD often goes undiagnosed.

Abstract

Importance

It is currently unclear whether chronic kidney disease (CKD)–associated cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes (T2D) is modifiable.

Objective

To examine whether cardiovascular risk can be modified with finerenone in patients with T2D and CKD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Incidence rates from Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY), a pooled analysis of 2 phase 3 trials (including patients with CKD and T2D randomly assigned to receive finerenone or placebo) were combined with National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data to simulate the number of composite cardiovascular events that may be prevented per year with finerenone at a population level. Data were analyzed over 4 years of consecutive National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data cycles (2015-2016 and 2017-2018).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incidence rates of cardiovascular events (composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or hospitalization for heart failure) were estimated over a median of 3.0 years by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albuminuria categories. The outcome was analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models stratified by study, region, eGFR and albuminuria categories at screening, and cardiovascular disease history.

Results

This subanalysis included a total of 13 026 participants (mean [SD] age, 64.8 [9.5] years; 9088 male [69.8%]). Lower eGFR and higher albuminuria were associated with higher incidences of cardiovascular events. For recipients in the placebo group with an eGFR of 90 or greater, incidence rates per 100 patient-years were 2.38 (95% CI, 1.03-4.29) in those with a urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) less than 300 mg/g and 3.78 (95% CI, 2.91-4.75) in those with UACR of 300 mg/g or greater. In those with eGFR less than 30, incidence rates increased to 6.54 (95% CI, 4.19-9.40) vs 8.74 (95% CI, 6.78-10.93), respectively. In both continuous and categorical models, finerenone was associated with a reduction in composite cardiovascular risk (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.95; P = .002) irrespective of eGFR and UACR (P value for interaction = .66). In 6.4 million treatment-eligible individuals (95% CI, 5.4-7.4 million), 1 year of finerenone treatment was simulated to prevent 38 359 cardiovascular events (95% CI, 31 741-44 852), including approximately 14 000 hospitalizations for heart failure, with 66% (25 357 of 38 360) prevented in patients with eGFR of 60 or greater.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this subanalysis of the FIDELITY analysis suggest that CKD-associated composite cardiovascular risk may be modifiable with finerenone treatment in patients with T2D, those with eGFR of 25 or higher, and those with UACR of 30 mg/g or greater. UACR screening to identify patients with T2D and albuminuria with eGFR of 60 or greater may provide significant opportunities for population benefits.

Introduction

In 2004, a landmark study by Go et al1 demonstrated that chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Lower levels of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were associated with higher risks of mortality from any cause, cardiovascular events, and hospitalizations.1 Further analyses from large cohorts showed that albuminuria and eGFR jointly identify those at highest risk of cardiovascular events.2 Conversely, restoration of kidney function by kidney transplant is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events.3 It is currently well established that the risk of kidney outcomes can be modified in individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D).4,5,6,7 What remains less well understood is whether the cardiovascular disease risk imposed by CKD, as assessed by eGFR and albuminuria, is modifiable with treatment among people with T2D.

The modifiability of cardiovascular risk among patients with CKD has been demonstrated with the use of simvastatin-ezetimibe in the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) trial.8 However, the study considered kidney function (as assessed by eGFR) but not kidney damage (albuminuria) in the recruitment strategy. Thus, the modifiability of CKD-associated cardiovascular risk in patients with T2D in a broader population—even with eGFR of 60 or greater and defined by albuminuria—remains unknown. Data from Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY), a prespecified pooled analysis of 2 phase 3 randomized trials that investigated the efficacy and safety of the selective, nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) finerenone provide an opportunity to further explore the role of CKD as a cardiovascular risk factor. The FIDELITY trial included patients with T2D and a wide spectrum of CKD, and outcomes in the analysis were independently adjudicated. Furthermore, the Finerenone in Reducing Kidney Failure and Disease Progression in Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD) and Finerenone in Reducing Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity in Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD) trials were similarly designed and included a cardiovascular outcome as the primary and key secondary end point, respectively. In patients with T2D, we tested whether the cardiovascular disease risk associated with CKD, as defined jointly by eGFR and albuminuria, was modifiable with finerenone treatment. We then estimated the population-wide benefit in the US if all eligible patients were treated with finerenone.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

For this analysis, we used data from the FIDELITY data set, which consists of 2 large, parallel, complementary, global trials, to test the hypothesis that CKD-associated composite cardiovascular risk is modifiable in patients with T2D treated with finerenone. The individual trial designs and results have been published previously.9,10 FIGARO-DKD11 had a primary cardiovascular-specific outcome, which was the key secondary outcome of FIDELIO-DKD.9,10,12 Each trial was powered to assess cardiovascular protection with finerenone vs placebo.

Adults (aged ≥18 years) with T2D and CKD who were receiving a maximum-tolerated labeled dose of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for at least 4 weeks before screening were eligible. Participants self-identified with the following race and ethnicity categories: Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic, White, or other/not reported. Races and ethnicities in the other category included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or those identifying as multiple races. Race and ethnicity were calculated as 2 separate categories. Hispanic fell under the category ethnicity where one could identify as “not Hispanic” or “Hispanic” or “not reported.” CKD was defined as follows: persistent, moderately increased albuminuria (urine albumin to creatinine ratio [UACR] 30-<300 mg/g) with either eGFR of 25 or greater but less than 60 and presence of diabetic retinopathy in FIDELIO-DKD or eGFR of 25 or greater but less than or equal to 90 in FIGARO-DKD or persistent, severely increased albuminuria (UACR ≥300-≤5000 mg/g) and either eGFR of 25 or greater but less than 75 in FIDELIO-DKD or eGFR of 60 or greater in FIGARO-DKD. At both run-in and screening visits, patients were required to have a serum potassium level less than or equal to 4.8 mmol/L (to convert to milliequivalents per liter, divide by 1).13,14

Interventions and Outcomes

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to oral finerenone (at titrated doses of 10 or 20 mg once daily) or matching placebo, as described previously.9,10 Patients were followed up after randomization at month 1, month 4, and every 4 months thereafter.

The key outcome studied in this analysis was a composite cardiovascular outcome of time to cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF). All potential cardiovascular outcomes were prospectively adjudicated by an independent clinical event committee blinded to treatment assignment.9,10

Statistical Analyses

FIDELITY Analyses

Analyses were performed in the full analysis set, which comprised all randomly assigned patients except those with critical Good Clinical Practice violations, who were prospectively excluded from all analyses. The incidence rates for the cardiovascular outcome, over a range of eGFR stages and albuminuria categories as defined by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), were calculated for each of the 2 treatment arms, finerenone, and placebo, respectively. The outcome was analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models stratified by the factors (as prespecified in the Integrated Analysis Statistical Analysis Plan): study, region (North America, Latin America, Europe, Asia, and other, which included Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa), eGFR category at screening (25-<45, 45-<60, and ≥60), albuminuria category (moderately and severely increased) at screening, and a history of cardiovascular disease (present or absent).

P values for comparison of treatment groups are presented based on a stratified log-rank test. Treatment outcomes are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) from the stratified Cox proportional hazards models.

Further, predicted probabilities after 4 years by treatment group were calculated based on unstratified Cox regression models adjusted with covariates, study (FIDELIO-DKD12 or FIGARO-DKD11), cardiovascular disease history, race and ethnicity, sex, region, continuous measures of eGFR and the log of UACR, age, hemoglobin A1c level, and systolic blood pressure at baseline. Cox regression models were used to provide predicted probabilities by eGFR using a cubic B-spline with preselected knots at 30, 45, 60, and 90. Additionally, Cox regression models were used to provide predicted probabilities by UACR using a cubic B-spline with preselected knots at 30, 300, and 1000 mg/g. In the latter model, UACR was log transformed and back transformed for presentation. Knots were selected based on comparing Akaike information criterion of several models using different models with preselected knots. Events were counted from randomization up to the end-of-study visit, and patients without an event were censored at the date of their last contact with complete information on all components of the respective outcome. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Analysis

To estimate the number of individuals in the US with albuminuric CKD and T2D at cardiovascular risk who would be eligible for finerenone treatment as per the US label,15 we conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES is a complex, multistage probability sample of the US population that collects health and nutritional status information via interviews and physical examinations. NHANES sampling weights account for oversampling of certain populations, noncoverage, and nonresponse; therefore, they may be used to calculate estimates representative of the US population.

Individuals were identified by searching 4 years of consecutive NHANES data cycles (2015-2016 and 2017-2018). Individuals with a completed NHANES mobile examination who had T2D defined from the diabetes questionnaire, eGFR of 25 or greater, UACR of 30 mg/g or greater, and serum potassium level less than 5.1 mmol/L, were included in the analysis. Adults with T2D were identified using the NHANES diabetes survey using a sequential algorithm of self-reported questions (“Doctor told you have diabetes?” [Yes] and “Taking insulin now?” [No]) or (“Doctor told you have diabetes?” [Yes] and “Taking insulin now?” [Yes] and “Age when first told you had diabetes?” [age ≥30 years]). The eGFR was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation, based on age, sex, race and ethnicity, and serum creatinine values.16 The maximum limit of serum potassium of 5.1 mmol/L was selected for consistency with the finerenone label15 and because 6.2% of patients (807 of 13 026) in FIDELITY had serum potassium greater than 4.8 to 5.0 mmol/L or less at baseline.

Missing data on T2D status, eGFR, UACR, or potassium level were not included, and no imputation adjustments were made. All data management and analysis were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) in accordance with NHANES analytic guidance. To accommodate NHANES complex sampling design, the Taylor series (linearization) method to incorporate complex survey variables for weighting, stratification, and clustering was used. SAS software was used to estimate weighted frequencies, percentages, SEs, and confidence limits. All weighted calculations were based on the multistage stratified design of the survey.

Simulation of Potentially Preventable Cardiovascular Events per Year With Finerenone

The excess number of events in the US population per year was calculated based on a 2-step Monte Carlo simulation with 10 000 iterations combining the data from the NHANES subset and the FIDELITY prespecified pooled analysis. Normally distributed population counts by KDIGO eGFR and albuminuria categories were generated based on the NHANES data matched to the FIDELITY analysis data based on inclusion and exclusion criteria as described previously. In the next step, Poisson-distributed incidence rates for each treatment arm and KDIGO category were generated based on the simulated population counts and incidence rates from FIDELITY. Subsequently, estimates of the excess number of events by KDIGO category in patients eligible for treatment with finerenone were calculated. The simulation was conducted with R, version 4.0.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Data were analyzed over 4 years of consecutive NHANES data cycles (2015-2016 and 2017-2018). A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The FIDELITY study sample used as a model in this subanalysis included 13 026 patients (mean [SD] age, 64.8 [9.5] years; 9088 male [69.8%]; 3938 female [30.2%]) with CKD and T2D with a broad range of eGFR and UACR values. Participants self-identified with the following race and ethnicity categories: 2894 Asian (22.2%), 522 Black or African American (4.0%), 2099 Hispanic (16.1%), 8869 White (68.1%), or 741 other/not reported (5.7%). Mean (SD) eGFR was 57.6 (21.7), and median (IQR) UACR was 515 (198-1147) mg/g. Overall, 10.2% of patients (1323 of 13 026), 41.0% of patients (5345 of 13 026), and 48.3% of patients (6288 of 13 026) had moderate, high, and very high KDIGO risk scores, respectively, based on a combination of UACR and eGFR categories according to individual baseline values. Baseline characteristics were largely balanced between eGFR and UACR categories; however, prevalence of a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease increased with lower eGFR and was higher in patients with UACR less than 300 mg/g than in those with UACR of 300 mg/g or greater (52.6% of patients [2279 of 4329] and 42.1% of patients [3655 of 8692], respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY) Study Sample.

| Characteristica | eGFR <30 (n = 890) | eGFR 30-<45 (n = 3504) | eGFR 45-<60 (n = 3434) | eGFR 60-<90 (n = 3876) | eGFR ≥90 (n = 1319) | UACR <300 mg/g (n = 4329) | UACR ≥300 mg/g (n = 8692) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 66.9 (8.6) | 67.3 (9.0) | 66.5 (8.8) | 63.4 (9.1) | 56.0 (8.8) | 67.6 (8.6) | 63.3 (9.7) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 570 (64.0) | 2399 (68.5) | 2468 (71.9) | 2768 (71.4) | 883 (66.9) | 3018 (69.7) | 6068 (69.8) |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 320 (36.0) | 1105 (31.5) | 966 (28.1) | 1108 (28.6) | 436 (33.1) | 1311 (30.3) | 2624 (30.2) |

| Race or ethnic group, No. (%) | |||||||

| Asian | 203 (22.8) | 811 (23.1) | 836 (24.3) | 856 (22.1) | 188 (14.3) | 821 (19.0) | 2073 (23.8) |

| Black/African American | 64 (7.2) | 147 (4.2) | 138 (4.0) | 134 (3.5) | 39 (3.0) | 159 (3.7) | 363 (4.2) |

| Hispanic | 132 (14.8) | 478 (13.6) | 504 (14.7) | 706 (18.2) | 277 (21.0) | 617 (14.3) | 1480 (17.0) |

| White | 561 (63.0) | 2358 (67.3) | 2286 (66.6) | 2645 (68.2) | 1018 (77.2) | 3162 (73.0) | 5704 (65.6) |

| Other/not reporteda | 62 (7.0) | 188 (5.4) | 174 (5.1) | 241 (6.2) | 74 (5.6) | 187 (4.3) | 552 (6.4) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 86.4 (20.9) | 87.2 (19.7) | 87.2 (19.8) | 88.6 (19.8) | 92.4 (21.6) | 87.7 (19.6) | 88.3 (20.3) |

| Duration of diabetes, mean (SD), y | 17.5 (9.1) | 16.9 (9.1) | 15.7 (8.8) | 14.5 (8.2) | 11.8 (7.1) | 15.9 (9.1) | 15.1 (8.5) |

| HbA1c, mean (SD), % | 7.6 (1.3) | 7.6 (1.3) | 7.6 (1.3) | 7.7 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.3) | 7.8 (1.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 136.0 (16.2) | 136.9 (14.7) | 136.6 (14.0) | 137.1 (13.9) | 136.1 (12.8) | 134.2 (14.4) | 138.0 (13.9) |

| Medical history, No. (%) | |||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 448 (50.3) | 1856 (53.0) | 1746 (50.8) | 1505 (38.8) | 378 (28.7) | 2279 (52.6) | 3655 (42.1) |

| Baseline medications, No. (%) | |||||||

| Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors | 888 (99.8) | 3501 (>99.9) | 3424 (99.7) | 3868 (99.8) | 1319 (100.0) | 4321 (99.8) | 8677 (99.8) |

| Statins | 685 (77.0) | 2665 (76.1) | 2580 (75.1) | 2671 (68.9) | 796 (60.3) | 3237 (74.8) | 6159 (70.9) |

| Antiplatelets | 548 (61.6) | 2101 (60.0) | 2042 (59.5) | 2006 (51.8) | 604 (45.8) | 2588 (59.8) | 4711 (54.2) |

| Insulin | 614 (69.0) | 2185 (62.4) | 1963 (57.2) | 2131 (55.0) | 735 (55.7) | 2361 (54.5) | 5266 (60.6) |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | 57 (6.4) | 245 (7.0) | 250 (7.3) | 290 (7.5) | 102 (7.7) | 330 (7.6) | 614 (7.1) |

| SGLT-2 inhibitors | 13 (1.5) | 129 (3.7) | 241 (7.0) | 344 (8.9) | 150 (11.4) | 299 (6.9) | 578 (6.6) |

| eGFR, mean (SD) | 26.9 (2.3) | 37.7 (4.3) | 52.0 (4.3) | 73.2 (8.6) | 99.7 (7.6) | 53.8 (18.3) | 59.5 (22.9) |

| eGFR, No. (%) | |||||||

| <30 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 255 (5.9) | 635 (7.3) |

| 30-<45 | 1298 (30.0) | 2206 (25.4) | |||||

| 45-<60 | 1471 (34.0) | 1962 (22.6) | |||||

| 60-<90 | 1094 (25.3) | 2780 (32.0) | |||||

| ≥90 | 211 (4.9) | 1108 (12.7) | |||||

| UACR, median (IQR), mg/g | 720 (242-1642) | 516 (163-1250) | 389 (127-1009) | 546 (262-1100) | 604 (376-1103) | 114 (61-196) | 871 (513-1564) |

| UACR, No. (%), mg/g | |||||||

| <30 | 16 (1.8) | 68 (1.9) | 82 (2.4) | 51 (1.3) | 13 (1.0) | 230 (5.3) | 0 |

| 30-<300 | 239 (26.9) | 1230 (35.1) | 1389 (40.4) | 1043 (26.9) | 198 (15.0) | 4099 (94.7) | 0 |

| ≥300 | 635 (71.3) | 2206 (63.0) | 1962 (57.1) | 2780 (71.7) | 1108 (84.0) | 0 | 8692 (100.0) |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1, glucagonlike peptide 1; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; NA, not applicable; SGLT-2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2; UACR, urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

Other included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or those identifying as multiple races.

Cardiovascular Event Incidence Rates in the FIDELITY Trial

Over a median (IQR) follow-up period of 3.0 (2.3-3.8) years, the incidence rate of cardiovascular events was higher in patients in lower eGFR and higher UACR categories (Table 2; eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). In placebo recipients with UACR less than 300 mg/g, the incidence rate was 2.38 per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 1.03-4.29) in patients with eGFR of 90 or greater vs 6.54 per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 4.19-9.40) in those with eGFR less than 30. In placebo recipients with UACR of 300 mg/g or greater, the corresponding incidence rates were 3.78 (95% CI, 2.91-4.75) and 8.74 (95% CI, 6.78-10.93) per 100 patient-years, respectively. Overall, finerenone was associated with a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events vs placebo (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.95; P = .002). This associated reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events with finerenone occurred across the ranges of eGFR and UACR, with no significant interaction between the outcome of finerenone vs placebo across eGFR and UACR groups (P for interaction = .66) (Table 2; eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Incidence Rates of Composite Cardiovascular Events in the Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY) Trial.

| eGFR | Composite cardiovascular events (incidence rate per 100 patient-years [95% CI])a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UACR <300 mg/gb | UACR ≥300 mg/g | |||||

| Placebo (n = 2133) | Finerenone (n = 2196) | HR for finerenone vs placebo (95% CI) | Placebo (n = 4370) | Finerenone (n = 4321) | HR for finerenone vs placebo (95% CI) | |

| ≥90 | 2.38 (1.03-4.29)c | 1.94 (0.78-3.62)c | 0.57 (0.19-1.68)c | 3.78 (2.91-4.75)d | 2.56 (1.86-3.37)d | 0.66 (0.45-0.97)d |

| 60-<90 | 3.57 (2.77-4.48)c | 2.98 (2.29-3.76)c | 0.82 (0.57-1.16)c | 4.76 (4.11-5.45)d | 4.49 (3.86-5.17)d | 1.01 (0.82-1.23)d |

| 45-<60 | 4.53 (3.72-5.42)d | 3.26 (2.57-4.03)d | 0.72 (0.54-0.98)d | 5.70 (4.79-6.70)e | 4.69 (3.89-5.56)e | 0.83 (0.65-1.07)e |

| 30-<45 | 4.93 (4.00-5.95)e | 4.89 (3.98-5.89)e | 0.98 (0.73-1.30)e | 6.03 (5.14-6.99)e | 5.84 (4.97-6.79)e | 0.96 (0.77-1.19)e |

| <30 | 6.54 (4.19-9.40)e | 5.85 (3.75-8.41)e | 0.82 (0.44-1.52)e | 8.74 (6.78-10.93)e | 6.89 (5.13-8.90)e | 0.75 (0.51-1.09)e |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; UACR, urine albumin to creatinine ratio; KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes.

P value for interaction = 0.66.

A total of 230 patients with UACR less than 30 mg/g were included in FIDELITY because of variability between screening and baseline results.

Moderate KDIGO risk category.

High KDIGO risk category.

Very high KDIGO risk category.

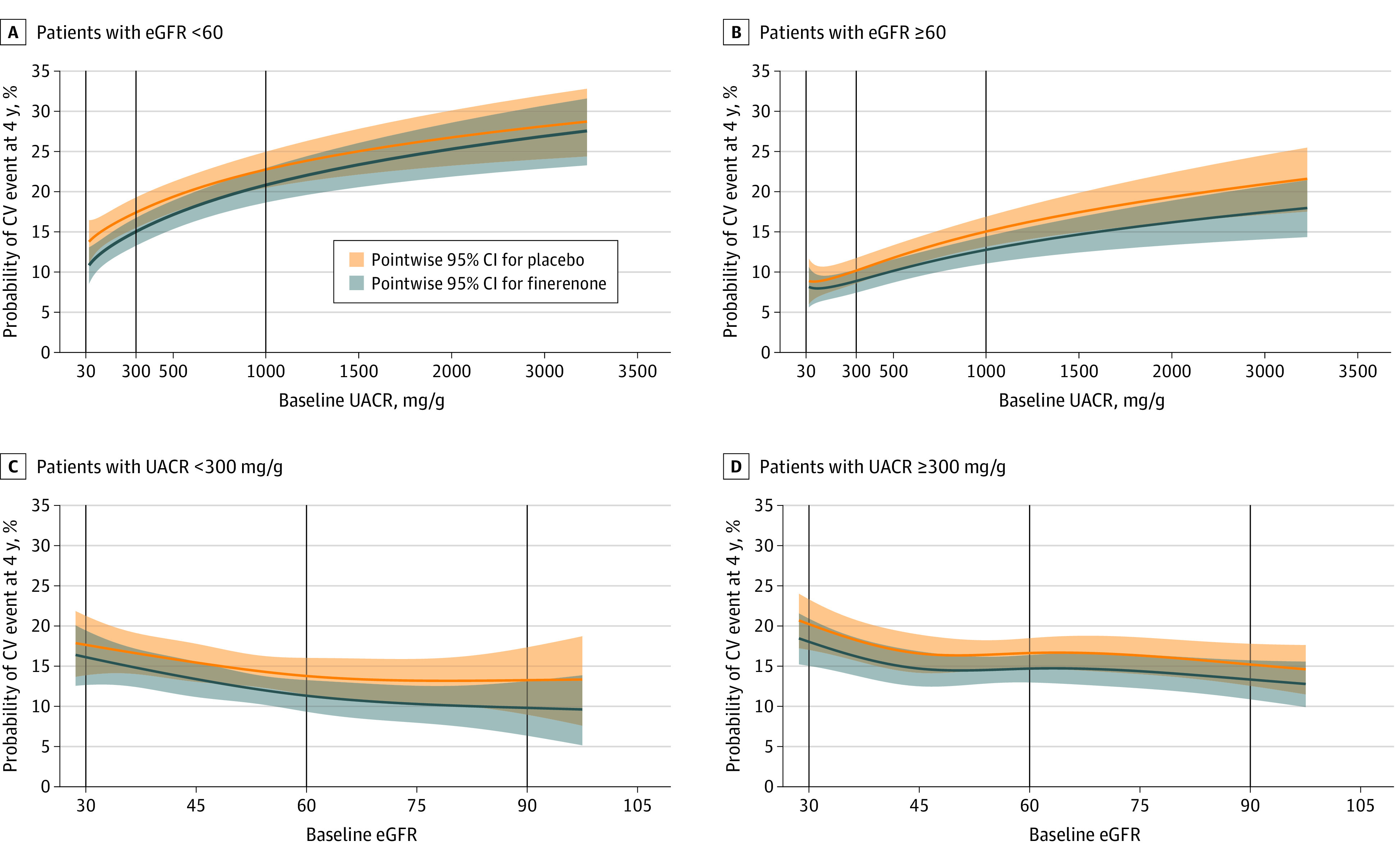

Modeling of the predictive probability of a cardiovascular event at 4 years indicated a higher risk for patients with higher levels of albuminuria in both patients with eGFR less than 60 and those with eGFR of 60 or greater (Figure 1C and D). Finerenone was associated with a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events across all ranges of UACR in both patients with eGFR less than 60 and those with eGFR of 60 or greater. Similarly, a higher risk of a cardiovascular event at 4 years was observed in patients with UACR less than 300 mg/g and those with UACR of 300 mg/g or greater with lower levels of eGFR (Figure 1A and B). In both UACR groups, finerenone was associated with a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events across all ranges of eGFR.

Figure 1. Predicted Probability of a Composite Cardiovascular (CV) Event at 4 Years by Continuous Urine Albumin to Creatinine Ratio (UACR) and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR).

Patients with eGFR less than 60 (A) or greater than or equal to 60 (B). Patients with UACR less than 300 mg/g (C) or greater than or equal to 300 mg/g (D). The Cox proportional hazards model was fitted with the covariates treatment, study, CV disease history, region, sex, and race, and the continuous covariates age, hemoglobin A1c, systolic blood pressure, baseline UACR (log transformed), and eGFR at baseline. Cubic B-splines were used for log-transformed UACR (A and B) and eGFR (C and D). Vertical lines highlight predicted probability of composite CV events at key UACR and eGFR thresholds.

Simulation of Cardiovascular Event Prevention in the US

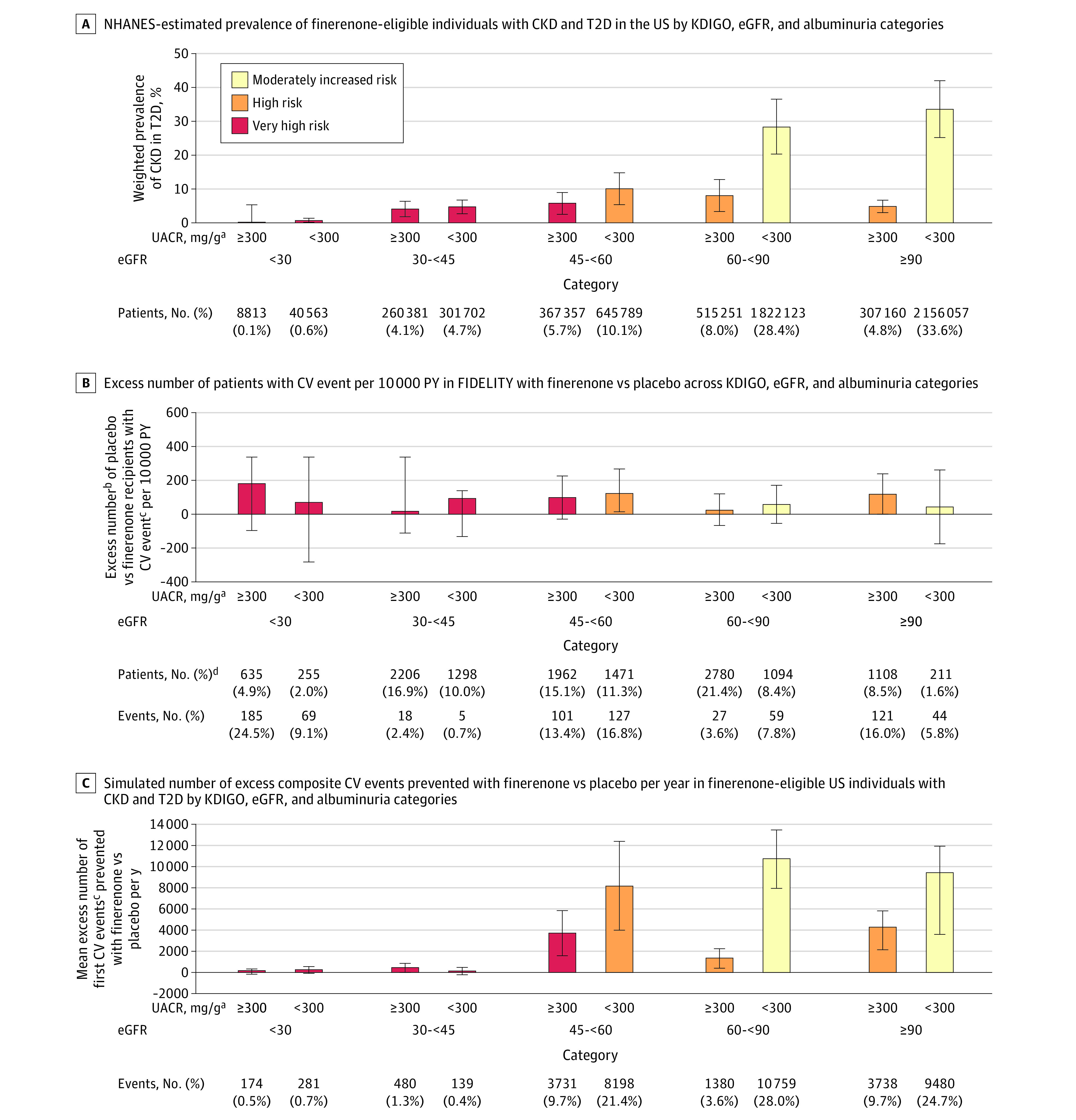

Of the NHANES-estimated 318.7 million noninstitutionalized population in the US, approximately 25.3 million would be identified as individuals with T2D (weighted prevalence 10.4%) based on a NHANES unweighted sample of 1580 individuals with T2D (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Individuals were further selected based on relevant laboratory values, including eGFR, UACR, serum potassium level, fasting plasma glucose concentration, and hemoglobin A1c levels. A total of approximately 6.4 million individuals with T2D and albuminuric CKD (95% CI, 5.4-7.4 million) who would be eligible for finerenone treatment were identified and included in the analysis (weighted prevalence 2.6%) (eFigure 2 and eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Baseline and clinical characteristics of the weighted and unweighted populations of the finerenone-eligible US population can be found in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. Among the approximately 6.4 million individuals who are eligible for finerenone with albuminuric CKD and T2D, the majority (74.7% [4 800 591 of 6 425 196]) had CKD with preserved eGFR (ie, ≥60), of which approximately 4.0 million (61.9% [3 978 180 of 6 425 196] of the overall population) had UACR less than 300 mg/g, and approximately 0.8 million (12.8% [822 411 of 6 425 196]) had UACR of 300 mg/g or greater. The remaining approximately 1.6 million individuals (25.3%) who were finerenone eligible with albuminuric CKD and T2D had eGFR less than 60; approximately 1.0 million individuals (15.4%) and 0.6 million individuals (9.9%) had UACR less than 300 mg/g and 300 mg/g or greater, respectively (Figure 2A and Table 3).

Figure 2. Composite Cardiovascular (CV) Risk Reduction by Finerenone Across Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) and Albuminuria Categories: Finerenone in Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Combined FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD Trial Programme Analysis (FIDELITY) Incidences and Population-Level Estimates.

Error bars represent 95% CIs. Colors represent KDIGO risk categories. A, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)–estimated prevalence of individuals eligible for finerenone with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the US by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), eGFR, and albuminuria categories. B, Excess number of patients with CV event per 10 000 person-years (PY) in FIDELITY with finerenone vs placebo across KDIGO, eGFR, and albuminuria categories. C, Simulated number of excess composite CV events prevented with finerenone vs placebo per year in US individuals eligible for finerenone with CKD and T2D by KDIGO, eGFR, and albuminuria categories.

aIndividuals with a UACR of 30 mg/g to less than 300 mg/g were included in NHANES, although 230 patients with UACR less than 30 mg/g were included in FIDELITY because of variability between screening and baseline results.

bBased on differences of FIDELITY incidence rates between the finerenone and placebo groups.

cComposite of time to CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.

dData on baseline eGFR and UACR categories were missing for 6 patients in FIDELITY.

Table 3. Unweighted and Weighted Prevalence Across Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) and Urine Albumin to Creatinine Ratio (UACR) Categories (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES]).

| eGFR level | UACR level | |

|---|---|---|

| 30-<300 mg/g | ≥300 mg/g | |

| ≥90 | ||

| Unweighted number of individuals in NHANES, No. (%) | 134 (30.8) | 26 (6.0) |

| Weighted number of individuals in the US, No. (95% CI) | 2 156 057 (1 437 094-2 875 019) | 307 160 (181 537-432 783) |

| Weighted prevalence in the US, % (95% CI) | 33.6 (25.1-42.0) | 4.8 (3.0-6.6) |

| 60-<90 | ||

| Unweighted number of individuals in NHANES, No. (%) | 125 (28.7) | 32 (7.4) |

| Weighted number of individuals in the US, No. (95% CI) | 1 822 123 (1 346 270-2 297 977) | 515 251 (201 861-828 642) |

| Weighted prevalence in the US, % (95% CI) | 28.4 (20.3-36.5) | 8.0 (3.3-12.7) |

| 45-<60 | ||

| Unweighted number of individuals in NHANES, No. (%) | 38 (8.7) | 28 (6.4) |

| Weighted number of individuals in the US, No. (95% CI) | 645 789 (309 423-982 155) | 367 357 (150 588-584 126) |

| Weighted prevalence in the US, % (95% CI) | 10.1 (5.3-14.8) | 5.7 (2.5-8.9) |

| 30-<45 | ||

| Unweighted number of individuals in NHANES, No. (%) | 28 (6.4) | 19 (4.4) |

| Weighted number of individuals in the US, No. (95% CI) | 301 702 (167 445-435 960) | 260 381 (107 268-413 495) |

| Weighted prevalence in the US, % (95% CI) | 4.7 (2.7-6.7) | 4.1 (1.8-6.3) |

| <30 | ||

| Unweighted number of individuals in NHANES, No. (%) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) |

| Weighted number of individuals in the US, No. (95% CI) | 40 563 (0-85 897) | 8813 (0-26 813) |

| Weighted prevalence in the US, % (95% CI) | 0.6 (0.0-1.3) | 0.1 (0.0-0.4) |

In the overall FIDELITY patient population, based on differences in incidence rates per 100 patient-years between the finerenone and placebo groups, the total excess number of cardiovascular events that would be prevented per 10 000 patient-years was 67 (95% CI, 24-111). Excess numbers of cardiovascular events were prevented with finerenone across all eGFR and UACR categories (Figure 2B). Based on the 6.4 million estimated finerenone-eligible US individuals with albuminuric CKD and T2D and the differences in incidence rates per 100 patient-years between the finerenone and placebo groups in FIDELITY, the simulated total number of cardiovascular events that could be prevented per year with finerenone treatment was estimated at 38 359 events (95% CI, 31 741-44 852). As first event of the composite end point, we estimated prevention of approximately 14 000 hospitalizations for heart failure. Owing to the high prevalence of CKD in T2D in patients with at least moderately elevated albuminuria (UACR ≥30 mg/g) and higher eGFRs (≥60) (Table 3), 66.1% of simulated cardiovascular events (25 357 of 38 359) that could be prevented were in this patient population that would be diagnosed with CKD based on albuminuria alone (Figure 2C).

Discussion

CKD-Associated Composite Cardiovascular Risk and Finerenone Treatment

Results of this subanalysis of the FIDELITY trial suggest that CKD-associated composite cardiovascular risk was modifiable. Furthermore, it was modifiable across a broad range of eGFR stages and albuminuria categories. For any eGFR stage, higher UACR was associated with a higher rate of cardiovascular events, even in patients with eGFR of 60 or greater. For any given level of albuminuria, lower eGFR was associated with a higher rate of cardiovascular events. Furthermore, findings suggest that within any category of eGFR or albuminuria, cardiovascular event risk was modifiable. Over the entire range of eGFR studied (≥25), composite cardiovascular risk was modifiable across albuminuria categories. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that cardiovascular disease risk is modifiable; of the components of cardiovascular disease risk, hospitalizations for heart failure were statistically significant. When confined to ASCVD events—such as myocardial infarctions and strokes—the relative risk reduction did not achieve statistical significance. Whether ASCVD event risk can be modified by nonsteroidal MRAs has not been established and requires further study.

Clinical Implications of the Modifiability of CKD-Associated Composite Cardiovascular Risk

The observation of an elevated, but modifiable, composite cardiovascular risk in patients with eGFR of 60 or greater but with moderately to severely increased albuminuria has significant implications for clinical practice. Despite recommendations in guidelines to screen both eGFR and albuminuria at least annually in patients with T2D,17,18 real-world evidence indicates that levels of screening for albuminuria in patients with CKD or T2D in clinical practice are very low.19,20,21 Although the importance of albuminuria as a risk factor for cardiovascular events is well known, the findings presented here indicate the ability to modify this risk to reduce morbidity and mortality, highlighting the urgency to improve rates of albuminuria testing irrespective of a patient’s eGFR. Indeed, as we see here, patients with eGFR of 60 or greater constitute nearly three-quarters of the US population eligible for treatment with finerenone; as such, the greatest simulated population benefits of finerenone were seen in this patient subgroup. Of a total 38 359 simulated excess composite cardiovascular events prevented per year with finerenone in the treatment-eligible US population, an estimated 25 357 composite events (66%) would be prevented per year in patients with albuminuria and eGFR of 60 or greater. Without routine screening of UACR in patients with T2D, as recommended by guidelines, the opportunity to modify the cardiovascular risk is lost.17,18 Given that treatment with finerenone also reduces the risk of CKD progression, including end-stage kidney disease, in patients with CKD and T2D, the health impact of screening for albuminuria in people with T2D is substantial.22

Results in Context

Prior studies have shown that the use of ACEis and ARBs can reduce the risk of kidney events.6,7 Although post hoc analyses suggested a trend toward a reduction in composite cardiovascular risk, these studies were not powered to detect a treatment-associated reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with CKD.6,7,23 The evidence base for cardiovascular event prevention in a broader population with a range of albuminuria and eGFR is accumulating.24 For example, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors also have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with albuminuric CKD and T2D; however, data on patients with less advanced CKD remain limited.5,25 By including patients with eGFR from a minimum of 25 and with a substantial population with moderately increased albuminuria (UACR, 30-300 mg/g), the present analysis covers a broader range of patients with CKD and T2D. It is noteworthy that in the FIDELITY trial, HHF was the main driver of the observed cardiovascular benefit.22 Therefore, HHF would likely account for a large proportion of the cardiovascular events prevented with finerenone at a population level as estimated in this analysis. Similar simulation analyses based on NHANES data estimated that in treatment-eligible patients with HF in the US, up to 250 000 and 180 000 worsening HF events could be prevented over 3 years of treatment by sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and sacubitril/valsartan, respectively.26,27 However, these did not specifically consider patients with CKD and T2D. Furthermore, given that the cardiovascular benefits of finerenone occurred on top of optimized use of ACEis or ARBs when prior trials of dual renin-angiotensin blockade alone failed to reduce the number of cardiovascular events in patients with CKD and T2D,28,29,30 the results of this analysis support the notion that MRA activation may be in the causal pathway of cardiovascular disease—especially hospitalization for heart failure— in patients with CKD associated with T2D.

Since 2019, multiple options have emerged to contain the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in CKD and T2D. However, many barriers to implementation exist that include the provision of equitable access, especially by the low-income population. If we are to contain the epidemic of CVD in CKD in T2D, these issues will need to be addressed.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this analysis include the adjudication of cardiovascular outcomes by an independent panel blinded to drug assignment and the robustness of the observed outcomes across subgroups. The analysis also has some limitations. The results should not be extrapolated to patients receiving dialysis or those with stage 5 CKD because these patients were not included in the FIDELITY trial. Additionally, patients with UACR less than 30 mg/g at screening were not included in the FIDELITY trial, despite patients without albuminuria still being considered at high risk at low eGFR levels.18 Another limitation is the lack of inclusion of significant numbers of Black and Hispanic patients, and dedicated trials are required to determine the effect of CKD modification on composite cardiovascular risk in patients without diabetes. There are also limitations in the estimates of population-level outcomes due to the number of uncontrollable factors in real-world settings, such as suboptimal adherence and access to care. In addition, the NHANES unweighted sample of finerenone-eligible individuals was small (n = 435), with particularly low numbers of individuals with eGFR less than 30 (n = 5); therefore, the excess event estimates in this subgroup are imprecise. Additionally, although ACEi or ARB use is a requirement for finerenone treatment, the NHANES sample was not restricted to patients receiving ACEis or ARBs. Further simulations and real-world studies would help provide further insights into the population-level benefits of finerenone. Further study is needed regarding modifiability of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk with finerenone.

Conclusions

In summary, results of the present subanalysis of the FIDELITY trial suggest that CKD-associated composite cardiovascular risk, driven in part by reduction in hospitalization for heart failure, was modifiable with finerenone treatment. Identifying patients with moderately to severely increased albuminuria and eGFR of 60 or greater and treating them to reduce cardiovascular risk will have public health implications.

eFigure 1. Incidence Rates of Cardiovascular Events by Treatment, eGFR Category, and Albuminuria in FIDELITY

eFigure 2. Patient Attrition to Identify the Albuminuric Finerenone-Eligible Sample in NHANES

eTable 1. NHANES-Estimated Prevalence of T2D and CKD in the US

eTable 2. Demographics and Clinical Attributes in the NHANES Population

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296-1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsushita K, Coresh J, Sang Y, et al. ; CKD Prognosis Consortium . Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for prediction of cardiovascular outcomes: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(7):514-525. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00040-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2093-2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03686.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. ; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators . Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436-1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. ; CREDENCE Trial Investigators . Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. ; Collaborative Study Group . Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):851-860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. ; RENAAL Study Investigators . Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861-869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. ; SHARP Investigators . The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181-2192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. ; FIDELIO-DKD Investigators . Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2219-2229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2025845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. ; FIGARO-DKD Investigators . Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):2252-2263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Clinical Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02545049. Updated April 15, 2022. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02545049

- 12.Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02540993. Updated July 19, 2021. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02540993

- 13.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. ; on behalf of the FIDELIO-DKD study investigators; FIDELIO-DKD study investigators . Design and baseline characteristics of the finerenone in reducing kidney failure and disease progression in Diabetic Kidney Disease Trial. Am J Nephrol. 2019;50(5):333-344. doi: 10.1159/000503713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruilope LM, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. ; FIGARO-DKD study investigators . Design and baseline characteristics of the finerenone in reducing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in Diabetic Kidney Disease Trial. Am J Nephrol. 2019;50(5):345-356. doi: 10.1159/000503712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerendia . Kerendia prescribing information. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://labeling.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Kerendia_PI.pdf

- 16.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration . Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association AD; American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee . 11. Chronic kidney disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(suppl 1):S175-S184. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group . KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;98(4S):S1-S115. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stempniewicz N, Vassalotti JA, Cuddeback JK, et al. Chronic kidney disease testing among primary care patients with type 2 diabetes across 24 U.S. health care organizations. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(9):2000-2009. doi: 10.2337/dc20-2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin JI, Chang AR, Grams ME, et al. ; CKD Prognosis Consortium . Albuminuria testing in hypertension and diabetes: an individual-participant data meta-analysis in a global consortium. Hypertension. 2021;78(4):1042-1052. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuttle KR, Alicic RZ, Duru OK, et al. Clinical characteristics of and risk factors for chronic kidney disease among adults and children: an analysis of the CURE-CKD registry. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1918169. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, et al. ; FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD investigators . Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(6):474-484. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, et al. ; HOPE Study Investigators . Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001;286(4):421-426. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):31-39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeler DC, Stefánsson BV, Jongs N, et al. ; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators . Effects of dapagliflozin on major adverse kidney and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetic and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: a prespecified analysis from the DAPA-CKD trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(1):22-31. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30369-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Greene SJ, et al. Potential implications of expanded US Food and Drug Administration labeling for sacubitril/valsartan in the US. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(12):1415-1423. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talha KM, Butler J, Greene SJ, et al. Population-level implications of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the US. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(1):66-73. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.4348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al. ; VA NEPHRON-D Investigators . Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(20):1892-1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, et al. ; ALTITUDE Investigators . Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2204-2213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai E, Chan JC, Ito S, et al. ; ORIENT study investigators . Effects of olmesartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes with overt nephropathy: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2011;54(12):2978-2986. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2325-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Incidence Rates of Cardiovascular Events by Treatment, eGFR Category, and Albuminuria in FIDELITY

eFigure 2. Patient Attrition to Identify the Albuminuric Finerenone-Eligible Sample in NHANES

eTable 1. NHANES-Estimated Prevalence of T2D and CKD in the US

eTable 2. Demographics and Clinical Attributes in the NHANES Population

Data Sharing Statement