Abstract

Purpose:

As the population ages, the number of people with cognitive impairment will rapidly increase. Although previous research has explored the rural-urban gap in physical health, few studies have analyzed cognitive health. The purpose of this study was to examine rural-urban differences in cognitive health, with a focus on the moderating effect of population decline.

Methods:

The study used individual-level nationally representative data from the 2000–2016 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (N = 152,444) merged to county-level contextual characteristics. Hierarchical linear models were used to predict the cognitive functioning of US adults aged 50 and over by rural-urban residence, county depopulation, and their interactions while controlling for individual-level and county-level demographic and contextual factors.

Findings:

Older adults living in rural counties had lower cognitive functioning than urban adults. The interaction between living in a rural and depopulated county was statistically significant (P < .001). The rural penalty in cognitive functioning was 40% larger for those who lived in counties that lost population between 1980 and 2010 compared to those who lived in stable or growing rural counties. These results were independent of race-ethnicity, gender, age, education, income, region, employment status, marital status, physical health, and depression as well as the county’s racial-ethnic composition, age structure, economic and educational disadvantage, and health care shortages.

Conclusions:

The results have important implications for those seeking to reduce health disparities both between rural and urban older adults and among different groups of rural people. Interventions targeting those living in rural depopulating areas are particularly warranted.

Keywords: cognitive health, depopulation, health disparities, population loss, rural health

One in 9 US adults over the age of 45 has experienced subjective cognitive decline.1 Over a third say that it has interfered with their daily activities, and over 40% indicate that they need help with basic household tasks. Subjective cognitive decline is also an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s disease. About 15%−20% of the US population aged 65 and older has mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease.1 Dementia is the single largest contributor to disability,2 and its total cost burden is similar to that of heart disease and cancer.3 In the past 20 years, while the number of deaths from heart disease has decreased, the number of deaths from Alzheimer’s has more than doubled.1,4 As our population ages, the number of people with dementia will rapidly increase. Today, 5.8 million people have Alzheimer’s disease, but by 2050, the number is projected to rise to 13.8 million.1 Further, rural areas in the United States are aging more rapidly than urban areas, suggesting that cognitive decline may be more of a pressing problem in the rural United States. Close to 18% of the rural population is aged 65 and older, compared to just 14% of the urban population in the United States.5

Research points to a rural-urban gap in cognitive functioning.6–9 Compared to their urban counterparts, those who live in more rural parts of the United States tend to be at an increased risk of dementia or mild cognitive impairment.10 The rate of mortality from Alzheimer’s and related dementias (ADRD) is higher in rural areas than in urban areas, and the increase is more pronounced in rural regions.4 Rural people with ADRD are also more likely than urban people with ADRD to seek treatment in emergency rooms for preventable visits.11 There are multiple interconnected correlates of cognitive impairment among older adults, and, likewise, there are various reasons for the rural-urban gap. Those living in rural areas have less formal education than their urban counterparts. Education is strongly associated with cognitive health,12 in part because engaging in complex and intellectually stimulating tasks throughout the earlier life course builds cognitive reserves or resilience, which staves off cognitive decline later in life.13 There are also substantial racial-ethnic differences in cognitive health. Older African Americans tend to have reduced cognitive functioning compared to older Whites.14 This is partially due to educational and social class differences that are linked to biological and health correlates, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart conditions.14 In addition to race and education, neighborhood economic deprivation may also reduce cognitive health by increasing people’s stress and decreasing their access to resources, such as libraries and community centers.15,16 Social activity and social engagement increase cognitive health and resilience,13,17–22 and all of these factors may differ both between rural and urban people as well as among those living in different rural areas. Vogelsang, for example, found that social participation was lower in rural areas than in urban areas.23

Compelling evidence points to a rural-urban gap in diabetes, obesity, heart disease, disability, depression, suicide, and mortality.24–28 These conditions contribute to cognitive decline and may also help to explain the rural penalty in cognitive health. Other studies have also shown differences among rural regions and suggested that morbidities cluster in the most geographically isolated areas of the United States. Most have focused on differences in rural regions’ size and adjacency to urban areas.29–32 Population decline has received far less attention, and yet it varies across the rural United States. About 24% of rural counties have experienced chronic population losses,33 yet, we know very little about its link to cognitive functioning and cognitive decline.

Rural depopulation reflects the out-migration of young, working-age adults as well as natural decreases, where deaths outpace births.33,34 It is more prevalent in regions historically dependent on agriculture and extractive industries.33 It can also hollow out communities and exact a toll on those left behind.35,36 Rural depopulation causes the tax base to shrink, which leaves less money for local infrastructure and essential services, such as schools, libraries, and community centers. These services attract new workers and residents and allow older residents to congregate and engage in stimulating activities that help prevent cognitive decline. A shrinking tax base also means less money for parks, walking trails, and other recreational activities and spaces that support physical health. This, too, could have negative ramifications, as declining physical health has been linked to declining cognitive health. Further, depopulating rural areas are also more likely to experience hospital closures and have difficulties recruiting and retaining health care workers.37

A few studies have shown that county-level economic conditions, such as population loss and unemployment, can shape physical health.31 But to date, no study has explored the connection between cognitive functioning and rural population decline. This is a critical research gap and one that is surprising given the abundance of research on other aspects of health disparities between rural and urban residents.38–40 The current study aimed to fill this void.

METHODS

Data source and sample

This study’s data came from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and conducted by the University of Michigan. It is an ongoing, nationally representative panel survey of communitydwelling, noninstitutionalized US adults aged 50 and older. The survey was first fielded in 1992 to 12,652 respondents who were between the ages of 50 and 61. These individuals were reinterviewed biennially, and new cohorts have been added every 6 years so that the panel remains representative of the older US population. Baseline interviews were conducted face-to-face and lasted about 3 hours. Follow-up interviews, which lasted about 2 hours, took place over the phone or in person for those aged 80 and older. In 2006, the HRS began to interview half of the sample in person every 4 years. I obtained individual-level data from the publicly available RAND HRS Longitudinal File. To measure county-level characteristics for each respondent, I used data from the restricted HRS Geographic Information File and the HRS Contextual Data Resource (HRS-CDR).41

Analyses were based on data from the 2000 to 2016 waves of the survey, which was the most recent wave available. The HRS interviewed just over 34,000 individuals between 2000 and 2016. These respondents were interviewed 4.8 times on average. Pooling across the years resulted in a sample initially comprised of 165,704 interviews with people aged 50 and older. Following previous research, I excluded 12,010 interviews conducted with proxy respondents, as these respondents did not take cognitive tests.42 After accounting for missing data, the final analytic sample included 152,444 interviews with 34,056 separate respondents.

Measures

Cognitive functioning

The primary dependent variable, cognitive functioning, was a reduced version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) that Langa and Weir developed.43 The measure was normally distributed and ranged from 0 to 27. The composite measure included immediate word recall (0–10 points), delayed word recall (0–10 points), serial subtraction of 7s (0–5 points), and backward counting from 20 (0–2 points). For immediate word recall, 10 nouns were read to the respondent in a standardized fashion by a computer. The survey interviewer then asked the respondent to recall as many words as possible. Delayed word recall was assessed by letting 5 minutes of survey questioning continue and then asking respondents to recall the 10 nouns. The interviewer then asked the survey respondent to subtract 7 from 100 and continue subtracting 7 for 5 trials. Finally, for backward counting, the respondent was asked to count backward as quickly as possible, beginning with the number 20. Respondents were allowed 2 attempts, and they received a score of 0 if they were incorrect on both attempts, a score of 1 if they were incorrect on the first try but correct on the second, and a score of 2 if they were correct on their first try.

Although most surveys were administered via telephone, research shows that cognitive scores in the HRS do not significantly differ between telephone and face-to-face surveying methods.44 Studies have also shown that the TICS cognitive functioning measure in the HRS has strong internal consistency and construct validity.43 Depending on the year and sample, the Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.67 to 0.87.45 Although the TICS is a screener tool, previous research has also shown that it is a relatively sensitive and specific indicator of cognitive impairment.46 One study showed that it had 83% sensitivity and 82% specificity for separating those with dementia from those without, and it had 83% sensitivity and 78% specificity for separating those with cognitive impairments from those with normal cognitive functioning.47

Rural-urban contextual characteristics

This study used the 2003 Beale Rural-Urban Continuum Codes to classify respondents as urban if they lived in metropolitan counties (Beale codes 1 through 3) and rural if they lived in nonmetropolitan counties (Beale codes 4 through 9). This coding scheme was created in 1975 by the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Economic Research Service,48 and it has been updated over the years. Just over 3% of HRS respondents who were living in a rural area had also spent at least 1 other wave in an urban location. The results were the same regardless of their inclusion or exclusion, so for simplicity, I left them in the sample.

Contextual data came from the 2000 and 2010 decennial censuses. The 2000 census was linked to the 2000–2008 waves of the HRS, and the 2010 census was linked to the 2010–2016 waves of the HRS. The measure of county-level population loss came from the county typology codes of the USDA’s Economic Research Service.41 A county was classified by the USDA as depopulating if the number of residents declined in the previous 2 decennial censuses. For the 2000 measure, a depopulated county was one that lost population between the 1980 and 1990 decennial censuses and the 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses. For the 2010 measure, a depopulated county was one that lost population between the 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses and the 2000 and 2010 decennial censuses. In this respect, the measure reflects a persistent decline.

I also used 2000 and 2010 US Census data to measure the percent of people in the county age 65 or over, the percent of non-Hispanic Black people in the county, and the percent of Hispanic or Latino people in the county. In addition, I included the county’s unemployment rate, the county’s poverty rate, and a dichotomous measuring indicating that 25% or more people in the county over the age of 25 had less than a high school degree.

I included a dichotomous measure of health care availability that was equal to 1 if at least 1 area in the county was designated as a geographical health care shortage area. This measure was available for 2007 from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research.49

Demographics

The study included a standard set of demographic controls in the multivariate statistical models. Gender was measured with a dichotomous variable. Marital status was a categorical measure reflecting whether a respondent was currently married, divorced, widowed, or never married. Age was included as a continuous variable. Race-ethnicity was self-reported and included the categories of White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and Other non-Hispanic. Educational attainment was included as a categorical variable reflecting less than a high school degree, a high school degree, some college, or at least a college degree. Household income was included as a categorical variable reflecting less than $25,000 (in 2016 dollars), $25,000-$74,999, and $75,000 or more. Employment was measured with a dichotomous variable. I also included 3 measures of health. These were self-reported physical health that compared excellent, very good, and good to fair or poor. The number of chronic medical conditions was ascertained with a series of survey questions asking the respondent if “a doctor ever told you that you have”: high blood pressure or hypertension; diabetes or high blood sugar; cancer or a malignant tumor of any kind except skin cancer; chronic lung disease except asthma, such as chronic bronchitis or emphysema; heart attack, coronary artery disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problem; stroke or transient ischemic attack; emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems; arthritis or rheumatism. A continuous measure of depression was based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD) scale.

Statistical analysis

All analyses used Stata 15.50 The unit of analysis was the respondent. I calculated descriptive statistics and estimated a series of nested multilevel linear regression models that predicted cognitive functioning from rural-urban, depopulation, individual-level characteristics, and county-level characteristics. Hierarchical models were appropriate in this context, as individuals had repeated observations over time. Missing values were as follows: 121 interviews (out of over 152,000 interviews) for rural-urban, 1 for cognitive functioning, 45 for depopulation, 122 for marital status, 320 for race-ethnicity, 25 for education, 438 for employment status, 126 for self-reported physical health, 9 for the number of chronic medical conditions, and 85 for CESD. In total, these reflected 0.008 of the analytic sample, and I used listwise deletion. I tested for quasi-multicolinnearity by inspecting a correlation matrix of coefficients from the multilevel model. Using the rule of 0.60,51 no estimates were highly multicollinear. A random intercept model was preferred over a random slope and intercept model, as a likelihood ratio test indicated that the models were not statistically different. The simpler model provided as good a fit.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents weighted descriptive statistics for the sample of US adults aged 50 and older. Just over 20% of the sample resided in rural counties, whereas nearly 80% of the sample resided in urban counties. All of the rural-urban differences were statistically significant except for gender, the “other” race-ethnicity category, and depression scores. People living in rural counties had a slightly lower cognitive functioning score than those living in urban counties (15.3 compared to 15.8). Compared to urban older adults, rural older adults were more likely to be married (62.3% compared to 60.7%) or widowed (17.2% compared to 14.9%) and less likely to be divorced (16.1% compared to 18.6%) or never married (4.3% compared to 5.8%). They were also slightly older on average. Over 86% of rural people in the sample were White, whereas just 77.5% of urban people in the sample were White. As expected, rural residents had less formal education than urban residents. Almost 18%, for example, had less than a high school degree, whereas just 14.7% of urban residents had less than a high school degree. Older rural adults also had less household income. Almost one-third lived in households with less than $25,000, compared to only 27.8% of their urban counterparts. Likewise, over one-third of urban residents had $75,000 or more, compared to just 23% of their rural counterparts. Rural residents were less likely to be employed (41.5% compared to 45.6%) and to self-report good health (71.8% compared to 75.9%). They also had more chronic medical conditions (1.9, on average, compared to 1.0).

TABLE 1.

Weighted descriptive statistics for US adults aged 50+ in the health and retirement study by rural and urban county of residence

| Rural (N=31,306) | Urban (N=121,138) | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of total sample | 20.5 | 79.4 |

| Cognitive function score | 15.3 (4.4) | 15.8 (4.4) |

| Female | 56.0 | 55.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 62.3 | 60.7 |

| Divorced | 16.1 | 18.6 |

| Widowed | 17.2 | 14.9 |

| Never married | 4.3 | 5.8 |

| Age | 66.1 (10.1) | 65.6 (10.1) |

| Race | ||

| White | 86.3 | 77.5 |

| Black | 6.8 | 10.5 |

| Hispanic | 3.9 | 8.8 |

| Other | 3.0 | 3.3 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 17.5 | 14.7 |

| High school | 40.8 | 31.4 |

| Some college | 22.7 | 25.4 |

| College degree | 18.9 | 28.5 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 32.3 | 27.8 |

| $25,000-$75,000 | 44.8 | 38.8 |

| $75,000+ | 23.0 | 33.4 |

| Employed | 41.5 | 45.6 |

| Self-reported good health | 71.8 | 75.9 |

| Number of chronic medical conditions | 1.9 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.5) |

| Depression score (CESD) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.4 (2.0) |

| US Region | ||

| New England | 2.1 | 5.6 |

| Mid Atlantic | 9.1 | 13.5 |

| East North Central | 18.7 | 16.5 |

| West North Central | 18.3 | 5.8 |

| South Atlantic | 18.4 | 22.1 |

| East South Central | 10.0 | 5.1 |

| West South Central | 15.1 | 7.9 |

| Mountain | 6.9 | 6.6 |

| Pacific | 1.4 | 17.0 |

| County-level characteristics | ||

| Depopulated county | 17.0 | 9.6 |

| Percent non-Hispanic Black | 4.8 (10.8) | 6.8 (11.2) |

| Percent Hispanic | 4.5 (10.7) | 9.3 (15.6) |

| Percent age 65+ | 14.8 (4.1) | 12.4 (3.8) |

| Unemployment rate | 6.3 (2.3) | 5.8 (2.2) |

| Low education county | 33.5 | 17.2 |

| Poverty rate | 14.4 (1.0) | 11.9 (1.1) |

| Health care professional shortage area | 31.3 | 25.7 |

Note: Percentages are reported for categorical variables; means (standard deviations) are reported for continuous variables. Boldface indicates a statistcally significant difference between rural and urban at P < .01. Descriptive statistics reported for the pooled sample across all survey waves. The number of people in rural counties = 7,024; the number of people in urban counties = 27,032.

Rural residents not only had lower educational attainment and income than their urban peers, but they were also more likely to live in economically disadvantaged counties. Seventeen percent lived in counties that experienced population decline, compared to just 9.6% of urban adults. Likewise, 33.5% of older rural adults lived in low education counties, whereas just 17.2% of urban older adults lived in low education counties. Nearly, a third of all rural residents lived in counties with at least 1 geographical health care shortage area, whereas just over a quarter of urban residents did.

The baseline multilevel model presented in Table 2 shows that, controlling for population decline, rural residents had slightly lower cognitive functioning than urban residents. And likewise, controlling for rurality, those who lived in depopulated counties had slightly lower cognitive functioning than those who lived in stable or growing counties. Model 2 adds an interaction and shows that depopulation was particularly problematic for rural residents compared to urban residents. Living in a rural county with a stable or growing population was associated with a 0.21-point reduction in cognitive functioning, whereas living in a rural depopulated county was associated with a 0.33-point decrease in cognitive functioning. In other words, the rural penalty in cognitive functioning was about 36% larger for those who lived in depopulated counties compared to those who lived in stable or growing rural counties. The coefficient for the main effect of living in a depopulated county changed from negative to positive between models 1 and 2. Although not the focus of the current study, when the individual-level control variables were excluded, the coefficient for the main effect reverted back to negative, pointing to a complex relationship between the demographic characteristics of those left behind in depopulating urban counties and their cognitive health.

TABLE 2.

Multilevel regression models predicting cognitive functioning among US adults aged 50+ (N = 152,444)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P value | Estimate | P value | Estimate | P value | |

| Focal variables | ||||||

| Rural county | −0.29** | <.01 | −0.21** | <.01 | −0.22** | <.01 |

| Depopulated county | −0.25** | <.01 | 0.21** | <.01 | 0.21** | <.01 |

| Rural × depopulated | −0.33** | <.01 | −0.36** | <.01 | ||

| Individual-level characteristics | ||||||

| Female (ref = male) | 0.83** | <.01 | 0.82** | <.01 | ||

| Marital status (ref = married) | ||||||

| Divorced | −0.26** | <.01 | −0.20** | <.01 | ||

| Widowed | −0.25** | <.01 | −0.23** | <.01 | ||

| Never married | −0.62** | <.01 | −0.52** | <.01 | ||

| Age | −0.14** | <.01 | −0.14** | <.01 | ||

| Race (ref = White) | ||||||

| Black | −2.46** | <.01 | −2.26** | <.01 | ||

| Hispanic | −1.74** | <.01 | −1.52** | <.01 | ||

| Other | −1.80** | <.01 | −1.64** | <.01 | ||

| Education (ref = less than high school) | ||||||

| High school | 2.04** | <.01 | 2.11** | <.01 | ||

| Some college | 2.87** | <.01 | 2.98** | <.01 | ||

| College degree | 3.96** | <.01 | 4.09** | <.01 | ||

| Income (ref = less than $25,000) | ||||||

| $25,000–$74,999 | 0.36** | <.01 | 0.37** | <.01 | ||

| $75,000+ | 0.43** | <.01 | 0.47** | <.0 | ||

| Employed (ref = not employed) | 0.09** | <.01 | 0.09** | <.01 | ||

| Self-reported good health (ref = fair/poor) | <.01 | <.01 | ||||

| Number of chronic medical conditions | −0.14** | <.01 | −0.12** | <.01 | ||

| Depression score (CESD) | −0.12** | <.01 | −0.13** | <.01 | ||

| Region (ref = New England) | ||||||

| Mid Atlantic | 0.24** | <.01 | 0.28** | <.01 | ||

| East North Central | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.25** | <.01 | ||

| West North Central | 0.35** | <.01 | 0.35** | <.01 | ||

| South Atlantic | 0.20* | 0.02 | 0.24** | <.01 | ||

| East South Central | −0.04 | 0.67 | 0.08 | <.01 | ||

| West South Central | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.30** | <.01 | ||

| Mountain | 0.24* | <.01 | 0.32** | <.01 | ||

| Pacific | 0.21* | 0.02 | 0.29** | <.01 | ||

| County-level characteristics | ||||||

| Percent non-Hispanic Black | −0.00* | 0.03 | ||||

| Percent Hispanic | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||||

| Percent age 65+ | 2.54** | <.01 | ||||

| Unemployment rate | −1.75* | 0.04 | ||||

| Low education | 0.06 | 0.22 | ||||

| Poverty rate | −2.04** | <.01 | ||||

| Health care professional shortage area | −0.00 | 0.97 | ||||

| Intercept | 14.83** | <.01 | 22.10** | <.01 | 21.31** | <.01 |

| Random effect | 13.43** | <.01 | 6.65** | <.01 | 6.62** | <.01 |

P < .05 (2-tailed tests).

P < .01.

The penalty presented in model 2 was statistically significant net of many individual-level characteristics that differed between rural and urban residents. As expected, model 2 shows that divorced, widowed, and never-married older adults had lower cognitive functioning than married older adults. Those who were older also had lower cognitive functioning. The estimates for race and education were substantial. Older Black adults, for example, had a cognitive score that was 2.46 points lower (or close to a standard deviation lower) than the cognitive functioning score for older Whites. Hispanics and those with other race-ethnicities also had lower cognitive functioning than older Whites. These racial-ethnic differences in cognitive functioning were robust to racial-ethnic differences in income, education, and other individual-level factors. Model 2 also shows that those with a college degree had a cognitive score that was almost 4 points higher than those who had less than a high school degree. Those who had some college degree scored close to 3 points more. Those who had a high school degree scored 2 points more than those who did not have a high school degree, net of many other individual-level characteristics. And yet, despite all of these differences, the penalty in cognitive functioning that was particularly pronounced for those living in rural depopulated areas remained robust.

County-level characteristics did not mediate the penalty in cognitive functioning experienced by those living in rural depopulated areas. Model 3 added many county-level aspects, and the interaction and main effects presented at the top of the table did not substantially change. As expected, an increase in the county’s poverty rate was associated with a reduction in an individual’s cognitive functioning, and those who lived in counties with a larger share of people aged 65 and over tended to have higher cognitive functioning. A number of the county-level estimates presented in model 3 were not statistically significant, but when they were added individually to the regression model, they were (these results are not shown but are available upon request). When low education, for example, was entered into the regression model without poverty and unemployment, it was statistically significant. When the health care shortage measure was added without all of the other county-level factors, it too was significant. Despite all of these county and individual controls, however, the steeper penalty paid by those living in depopulated rural counties remained robust. Model 3 shows that the rural penalty in cognitive functioning was 40% larger for those who lived in counties that lost population compared to those who lived in stable or growing rural counties.

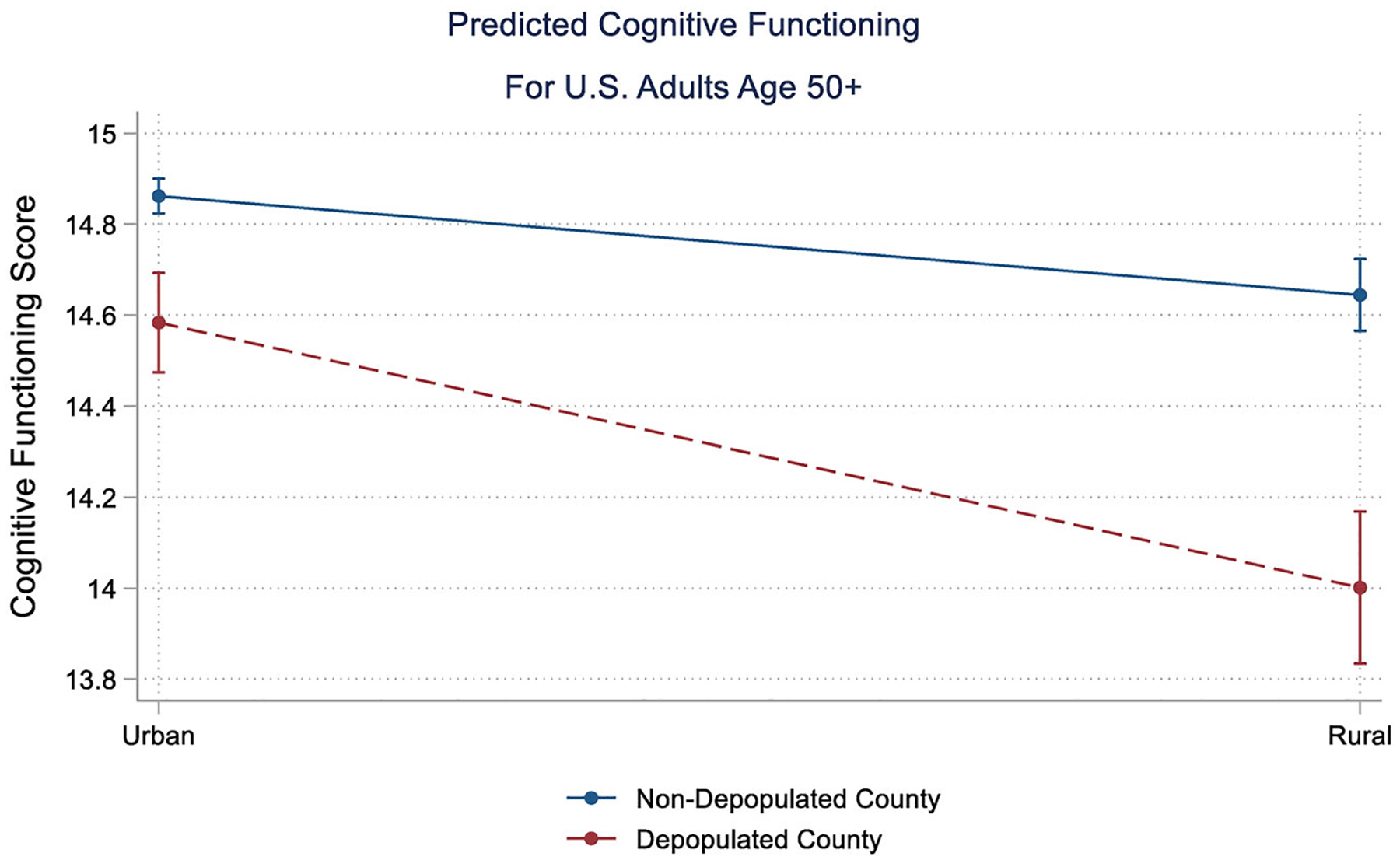

Figure 1 presents the predicted cognitive functioning scores for rural and urban residents living in depopulated counties or stable or growing counties. The predicted scores were derived from model 3 of Table 2, which included all of the control variables. As Figure 1 shows, rural older adults who resided in stable or growing counties had cognitive functioning that was relatively similar to urban older adults who lived in stable or growing counties. Older people living in rural counties that experienced population loss, however, had significantly lower cognitive functioning than older people living in rural counties that were not shrinking. The figure points to a substantial gap among rural older adults. Depopulation was particularly problematic for people living in rural areas. The differences shown in the figure are robust to all of the controls for individual-level characteristics and county-level characteristics.

FIGURE 1.

Predicted cognitive functioning for US adults age 50+. Note: Adjusted for all variables in model 3 of Table 2, with 95% confidence intervals

DISCUSSION

This study explored the links between cognitive health and rural depopulation using a nationally representative sample of US respondents aged 50 and older. The results pointed to a rural-urban gap in cognitive health, net of controls for individual-level demographic characteristics as well as county-level contextual characteristics. Further, the rural penalty was most pronounced for those living in rural depopulated counties. The results also showed that living in a county with a larger share of people aged 65 and older improved cognitive functioning, which was contrary to expectation. When the other county-level measures were excluded from the analyses, however, the age structure was negatively associated with cognitive functioning.

What do the results mean for those interested in improving the health and well-being of rural Americans? The penalty in cognitive functioning paid by rural older adults living in depopulated counties was clearly smaller than the race-based or education-based penalties in cognitive functioning. Still, it was similar to the discrepancy between unmarried and married older adults. Living in a depopulated rural county was as problematic for cognitive health as divorcing or becoming a widow. The cognitive health penalty for living in rural depopulated counties (ie, the interaction) was statistically significant and robust to race-ethnicity, gender, age, education, income, employment status, marital status, physical health, and depression, as well as the county’s geographical region, racial-ethnic composition, age structure, economic and educational disadvantage, and health care shortages. In short, the penalty was relatively small but nevertheless statistically significant, controlling for a host of other factors. The penalty was perhaps indicative of a slight decline in memory, serial subtraction of 7s, or delayed word recall, for example. The real problem, however, is that the rural United States is rapidly aging and losing its population. The continued hollowing out of rural communities suggests that minor health disparities, such as a small cognitive penalty, could swiftly increase in the years to come.

We are also left with the question of why cognitive functioning is particularly problematic in rural depopulating areas compared to urban depopulating regions. One answer is that population decline has hit rural areas much harder. Depopulating urban counties have, by definition, lost residents but at a much slower rate. Johnson and Lichter, for example, found that in 2010, 17% of all nonmetropolitan counties had lost over 50% of their peak population, whereas just 1% of metropolitan counties had lost over half of their population.34,52 These deep, concentrated losses experienced by rural depopulating areas have ripple effects. Tax bases shrink. Community centers close, and places where residents can engage with each other to “use it or lose it”13 start to become a thing of the past.

A few studies indicate that people living in more rural areas of the United States have higher levels of community involvement53 and more social relationships,54 whereas other studies have reported conflicting results.23 Since social engagement and social support improve cognitive functioning,13,16–22 policymakers and those interested in alleviating health disparities may want to consider creating spaces where people—especially those living in rural depopulating areas—can come together to experience meaningful interaction and activity. Intergenerational community centers may have broad appeal.55 At the very least, health care providers working in depopulating rural areas need to be attuned to the cognitive functioning of their older patients and provide advice on preventative behaviors. In general, and given limited resources, health care providers, policymakers, and community leaders should focus laser attention on depopulating rural areas.

Limitations

The study was limited in a few respects. First, the TICS-27 is a screener rather than a clinical measure of cognitive health. Although previous research has shown that the TICS is a relatively sensitive indicator of cognitive impairment,46 future research may want to evaluate rural-urban differences using a more clinical measure. In addition, future research should focus on mediating mechanisms. Numerous studies have shown that social engagement and social support improve cognitive functioning,13,17–22 yet, researchers have yet to fully understand the exact mechanisms that link social integration to brain health. In general, social engagement may improve health by providing resources, a sense of purpose in life, social pressure to engage in healthy behaviors, and stress reduction.56 As of yet, no study has tested whether integration modifies the link between rurality and cognitive decline. Future research should consider these mediating mechanisms and perhaps use novel measures of community resources, social activity, and social engagement.

CONCLUSIONS

Although communities and environments clearly shape people’s health,57 Lee and Waite recently argued that “Despite prior work linking place to various health outcomes, the effects of place on cognitive functioning have been relatively ignored.”34 The current study heeds this call and brings rural-urban inequality in cognitive functioning to the fore. The results broaden our understanding of aging and health among rural and urban older adults, particularly in relation to population decline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thanks Ken Johnson, the Interdisciplinary Network on Rural Depopulation Health and Aging (NRPHA) leadership team and advisory board as well as participants at the 2020 and 2021 INRPHA annual meeting for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft.

FUNDING

Support for this research was provided by the Interdisciplinary Research Network on Rural Population Health and Aging, which is funded by the National Institute on Aging (grant R24-AG065159).

Funding information

National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R24-AG065159

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaugler J, James B, Johnson T, Marin A, Weuve J. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321–387. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snowden MB, Steinman LE, Bryant LL, et al. Dementia and co-occurring chronic conditions: a systematic literature review to identify what is known and where are the gaps in the evidence? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(4):357–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross SH, Warraich HJ. Rural-urban disparities in mortality from Alzheimer’s and related dementias in the United States, 1999–2018. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021;69(4):1095–1096. 10.1111/jgs.16996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AS, Trevelyan E. The Older Population in Rural America: 2012–2016. U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/acs/acs-41.pdf

- 6.Keefover RW, Rankin ED, Keyl PM, Wells JC, Martin J, Shaw J. Dementing illnesses in rural populations: the need for research and challenges confronting investigators. J Rural Health. 1996;12(3): 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wing JJ, Levine DA, Ramamurthy A, Reider C. Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders prevalence differs by Appalachian residence in Ohio. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(4):1309–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassarino M, O’Sullivan V, Kenny RA, Setti A. Environment and cognitive aging: a cross-sectional study of place of residence and cognitive performance in the Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging.Neuropsychology. 2016;30(5):543–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saenz JL, Downer B, Garcia MA, Wong R. Cognition and context: rural-urban differences in cognitive aging among older Mexican adults. J Aging Health. 2018;30(6):965–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weden MM, Shih RA, Kabeto MU, Langa KM. Secular trends in dementia and cognitive impairment of US rural and urban older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2):164–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang N, Albaroudi A, Chen J. Decomposing urban and rural disparities of preventable ED visits among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: evidence of the availability of health care resources. J Rural Health. 2021;37(3):624–635. 10.1111/jrh.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, Miller-Martinez D, et al. Urban neighborhood context, educational attainment, and cognitive function among older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, Dixon RA. Use it or lose it: engaged lifestyle as a buffer of cognitive decline in aging? Psychol Aging. 1999;14(2):245–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zsembik BA, Peek MK. Race differences in cognitive functioning among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(5):S266–S274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aneshensel CS, Ko MJ, Chodosh J, Wight RG. The urban neighborhood and cognitive functioning in late middle age. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):163–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke PJ, Ailshire JA, House JS, et al. Cognitive function in the community setting: the neighbourhood as a source of “cognitive reserve”? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(8):730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(6):343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson RS. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287(6):742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ertel KA, Glymour MM, Berkman LF. Effects of social integration on preserving memory function in a nationally representative US elderly population. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1215–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes LL, de Leon CFM, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA. Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and Whites. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2322–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beland F, Zunzunegui MV, Alvarado B, Otero A, del Ser T. Trajectories of cognitive decline and social relations. J Gerontol Ser B-Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(6):P320–P330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fratiglioni L, Hui-Xin W, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: a community-based longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;355(9212):1315–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogelsang EM. Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: rural-urban differences. Health Place. 2016;42:111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sage R, Ward B, Myers A, Ravesloot C. Transitory and enduring disability among urban and rural people. J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):460–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Probst JC, Laditka SB, Moore CG, Harun N, Powell MP, Baxley EG. Rural-urban differences in depression prevalence: implications for family medicine. Fam Med. 2006;38(9):653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SA, Cook SK, Kelley L, Foutz JD, Sando TA. A closer look at rural-urban health disparities: associations between obesity and rurality vary by geospatial and sociodemographic factors. J Rural Health. 2017;33(2):167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Befort CA, Nazir N, Perri MG. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: findings from NHANES (2005–2008). J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Callaghan T, Ferdinand AO, Akinlotan MA, Towne SD, Bolin J. The changing landscape of diabetes mortality in the United States across region and rurality, 1999–2016. J Rural Health. 2020;36(3): 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kegler MC, Prakash R, Hermstad A, Anderson K, Haardörfer R, Raskind IG. Food acquisition practices, body mass index, and dietary outcomes by level of rurality. Journal of Rural Health. 2022;38(1):228–239. 10.1111/jrh.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abshire DA, Graves JM, Amiri S, Williams-Gilbert W. Differences in loneliness across the rural-urban continuum among adults living in Washington State. J Rural Health. 2022;38(1):187–193. 10.1111/jrh.12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monnat SM, Pickett CB. Rural/urban differences in self-rated health: examining the roles of county size and metropolitan adjacency. Health Place. 2011;17(1):311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lichter DT, Brown DL, Parisi D. The rural-urban interface: rural and small town growth at the metropolitan fringe. Popul Space Place. 2021;27(3):e2415–e2419. 10.1002/psp.2415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson KM. As births diminish and deaths increase, natural decrease becomes more widespread in rural America. Rural Sociol. 2020;85(4):1045–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson KM, Lichter DT. Rural depopulation: growth and decline processes over the past century. Rural Sociol. 2019;84(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thiede BC, Brown DL, Sanders SR, Glasgow N, Kulcsar LJ. A demographic deficit? Local population aging and access to services in rural America, 1990–2010. Rural Sociol. 2017;82(1):44–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wuthnow R The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Rural America. University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wishner J, Solleveld P, Rudowitz R, Paradise J, Antonisse L. A Look at Rural Hospital Closures and Implications for Access to Care. 2016.

- 38.Burton LM, Lichter DT, Baker RS, Eason JM. Inequality, family processes, and health in the “new” rural America. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8):1128–1151. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auchincloss AH, Hadden W. The health effects of rural-urban residence and concentrated poverty. J Rural Health. 2002;18(2):319–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monnat SM, Rigg KK. Examining rural/urban differences in prescription opioid misuse among US adolescents. J Rural Health. 2016;32(2):204–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ailshire J, Mawhorter S, Young MM, Choi YJ. USDA Food Environment and Access. 2020.

- 42.Choi H, Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Langa KM. Trends in the prevalence and disparity in cognitive limitations of Americans 55–69 years old. J Gerontol Ser B. 2018;73(suppl_1):S29–S37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66:i162–i171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herzog AR, Rodgers W. Cognition, Aging, and Self Reports. Psychology Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ofstedal MB, Fisher G.Documentation of Cognitive Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welsh K, Breitner J, Magruderhabib K. Detection of dementia in the elderly using telephone screening of cognitive status. Neuropsychiatr Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1993;6(2):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knopman DS, Roberts RO, Geda YE, et al. Validation of the telephone interview for cognitive status-modified in subjects with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34(1):34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.USDA ERS - Documentation. Accessed September 13, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuumcodes/documentation/

- 49.Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. County Characteristics, 2000–2007 [United States]. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [Distributor], 2008-01-24.

- 50.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allison PD. Multiple Regression. SAGE Publications Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greiner KA, Li CY, Kawachi I, Hunt DC, Ahluwalia JS. The relationships of social participation and community ratings to health and health behaviors in areas with high and low population density. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(11):2303–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henning-Smith C, Moscovice I, Kozhimannil K. Differences in social isolation and its relationship to health by rurality. J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penn State College of Agricultural Studies. Community Centres as Intergenerational Contact Zones. Plone site. Accessed September 13, 2021. https://aese.psu.edu/outreach/intergenerational/articles/intergenerational-contact-zones/recreation-centers

- 55.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jensen L, Monnat SM, Green JJ, Hunter LM, Sliwinski MJ. Rural population health and aging: toward a multilevel and multidimensional research agenda for the 2020s. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1328–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee H, Waite LJ. Cognition in context: the role of objective and subjective measures of neighborhood and household in cognitive functioning in later life. Gerontologist. 2018;58(1):159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]