Abstract

Schwannomas are tumors of the macroglia cells, most frequently localized to the brain, in the pontocerebellar angle. We present the case of a 53 year-old female patient who presented multiple times with diffuse abdominal pain and was initially diagnosed as having a complex right adnexal mass. Exploratory laparotomy found a retroperitoneal mass and later on, the presence of a sacral schwannoma was found, suspected initially on contrast magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen and pelvis, and confirmed by means of lesional biopsy and histopathology. This is a rare and unusual presentation accounting for only 5% of this tumor location and poses a challenge for imaging diagnosis, directly impacting the approach to the patient and any future interventions. There are few reports in the literature about giant sacral schwannomas, but these tumors have been found to extend within the spinal space towards the vertebral space, even occupying part of the abdomen. Hence, the importance of recognizing the presence of this tumor as well as its imaging features.

Keywords: schwannoma, sacrum, macroglia, resonance, nuerilemmomas

Introduction

Schwannomas or neurilemmomas are benign tumors arising from glial cells of the peripheral nervous system. They can be found in any part of the body and they can be associated with diseases such as neurofibromatosis, in particular of type 2, with sporadic presentation in 90% of cases.1,2 Only 1–5% develop in the sacrum and they rarely show cystic or hemorrhagic degeneration. There are few reports in the literature about giant sacral schwannomas, but these tumors have been found to extend within the spinal space towards the vertebral space, even occupying part of the abdomen as large retroperitoneal masses. 3 We present the case of patient who presented with diffuse abdominal pain. The initial impression was of a complicated adnexal mass, but following failed laparotomy a large heterogenous tumor with a solid contour and liquid core was found on contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), protruding from the neural foramen from L5 to S1 and compressing the bladder and adjacent structures anteriorly.

Case description

A 53 year-old female patient with no significant pathological history referred to an intermediate complexity hospital because of longstanding abdominal cramp-like pain, predominantly in the hypogastric region, associated with mass sensation, which exacerbated one week before seeking medical advice. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed at the referring institution showed a mass in the pelvic cavity with well-defined contours which displaced and compressed the bladder, uterus and rectum, apparently arising from the right adnexa. It was considered to be a complex adnexal mass. The patient was taken later to exploratory laparotomy which found a hard, firm mass attached to the retroperitoneum. At that point, the decision was made to refer the patient for additional workup at a higher complexity center.

On initial review by systems, the patient reported no additional symptoms, no constitutional symptoms, weight loss, or changes in bowel habitus. The initial physical examination found vital signs within normal ranges, normal cardiopulmonary findings, normal cardiopulmonary parameters, swollen abdomen soft to palpation with marked abdominal guarding in the tender lower hemiabdomen, no evident masses on palpation, and dullness to percussion in the left lower quadrant. The neurological examination was normal.

Contrast MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed a large mass in the pre-sacral space, extending from the spinal canal at L5–S1 and protruding through the first right neural foramen; it measured 16 × 9.8 cm in length on the AP view, with a cross-sectional diameter of 11 cm, and showed well-defined contours with heterogenous signal of the cystic central area and intensely enhancing solid peripheral areas on T2-weighted sequences, as well as significant diffusion restriction. Adjacent structures were found to be displaced, including anterior and inferior displacement of the bladder, and left lateral displacement of the rectum and the uterus, but with no signs of invasion. Lymph node assessment did not show adenopathies in the pre-sacral obturator chain or the hypogastric chain. No secondary lesions were found on extension contrast chest CT. CT-guided biopsy performed to study the histological component of the mass showed a tumor of spindle cell morphology, SOX10-positive staining, 4% cell proliferation index, and absence of mitosis or necrosis, confirming neural origin and suggesting benign behavior.

Discussion

Schwannomas, also referred to as neurilemmomas in the literature, are benign tumors of the peripheral nervous system support cells occurring less frequently than neurofibromas. 4 They appear sporadically in 90% of cases, but they have also been found in association with diseases such as neurofibromatosis type 2, schwannomatosis and Carney complex. 5 Epidemiological data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) between January 2006 and December 31, 2014, show an incidence of spinal schwannoma of 0.24 for every 100,000 inhabitants; 6 no records were found for Colombia. These tumors have no gender predilection and, given their slow growth, the age of presentation is between 50 and 60 years, with a median age of 56 years 5 with symptoms appearing within a range of 9 months to 23 years. 7

These tumors can be found in any part of the body, with the sacral localization accounting for less than 5% while vestibular schwannomas are more frequent, in up to 60% of cases. The term giant sacral schwannoma is defined as a tumor extending to more than 2 vertebral bodies which it erodes to penetrate deep planes, with extraspinal extension of more than 2.5 cm. According to the anatomical findings and clinical manifestations, they have been classified as retroperitoneal, intrasacral or intraosseous, and spinal (Figure 1). The intraosseus localization usually gives rise to local lumbar pain with no associated neurological deficits when compared to the spinal presentation. 3

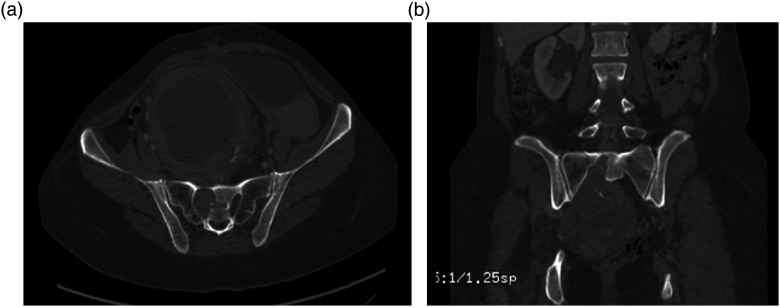

Figure 1.

(a): Tomographic axial section in bone window showing bone remodeling with enlarged first sacral neural foramen. (b): Tomographic coronal section in bone window showing bone remodeling of the sacrum.

The main clinical manifestations arise from the localization to the nerves and the compression of adjacent structures such as rectum or bladder, giving rise to moderate diffuse abdominal pain with pollakiuria and constipation, even paresthesias, gluteal pain radiating to the lower limb, and ipsilateral motor deficit (Figure 2). 7

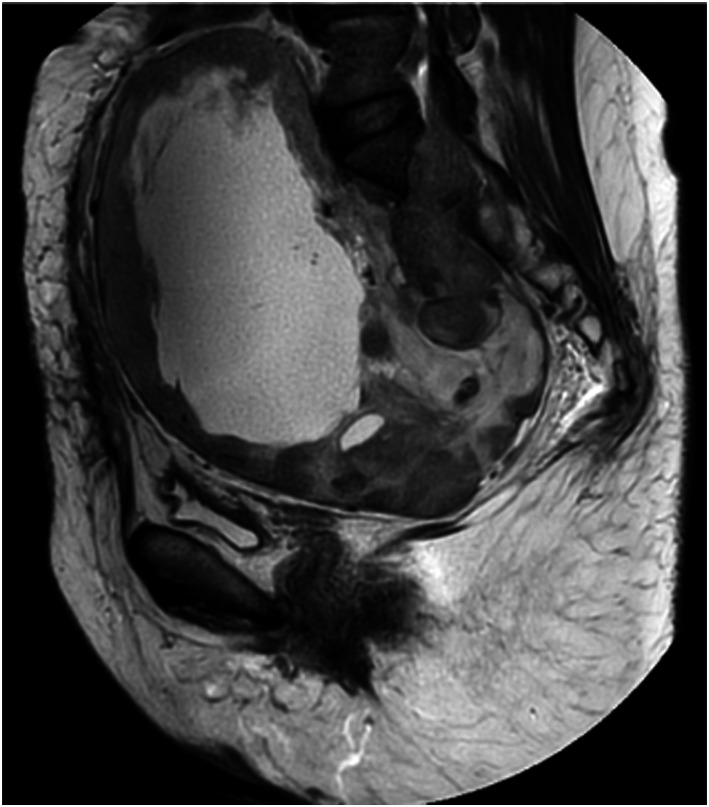

Figure 2.

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the pelvis showing a large heterogeneous tumor mass with solid contours and liquid center, protruding at the level of L5–S1, and compressing the bladder anteriorly.

Tumor biopsy is indicated for histological diagnosis, especially of the solid component, where two patterns can be found, namely, Antoni A and Antoni B. The main difference between the two is the high cellularity with palisade distribution and Verocay bodies formation in A, and a more disorganized patter with cystic degeneration in type B.1,6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Schwannoma presentatios: 5 The most common Antoni A and Antoni B.

| Classic schwannoma (vestibular) | Cellular schwannoma (paravertebral region) | |

|---|---|---|

| Antoni A | Antoni B | Compact hypercellular Antoni A pattern areas with no Verocay bodies |

| Hypercellular spindle cell pattern | Hypocellular myxomatous pattern | High cellularity, mitotic rate suggestive of malignancy, and fascicular growth pattern |

| Palisading around eosinophilic areas (Verocay bodies) | Presence of loose connective tissue | Key to the diagnosis of hystiocytic aggregate and high expression of pericellular type IV collagen |

| Positive S100 protein staining | Presence of cyst, hemorrhage, fatty degeneration, scarce calcifications | Poorly expressed desmin, smooth muscle actin, and CD117 |

Imaging workup for the suspected diagnosis includes ultrasound, conventional radiographs, CT scan, and MRI, with the aim of arriving at the adequate characterization of the type of tumor, localization, and relation to adjacent organs. The tumor develops as a fusiform mass, eccentric to the nerve involved, with defined edges composed of epineurium. 6

On initial ultrasound, the expectation is to find a round anechoic mass with posterior acoustic shadow, and defined contours. However, ultrasound is operator-dependent and its positive predictive value is affected by patient body composition and radiologist expertise.

Diagnostic methods such as lumbosacral radiograph and abdominal contrast CT help with the assessment of lytic bone lesions such as progressive expansion of the neural foramina, with the tumor appearing as contrast-enhanced and hypo or isodense (Figure 3).

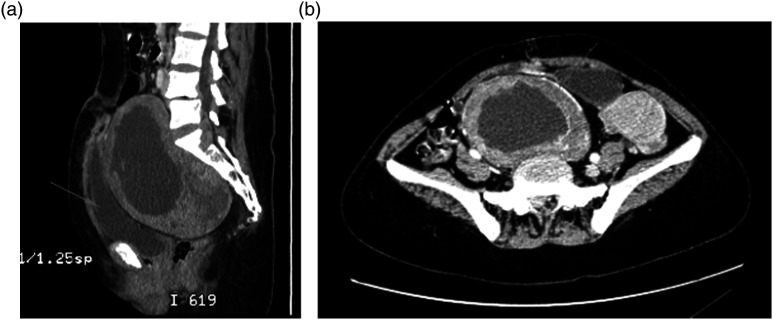

Figure 3.

(a). Sagittal section showing an isodense mass compared to the rectus abdominis muscles, with hypointense fluid-density center, and bladder compression. (b). Axial section showing the mass with peripheral contrast enhancement.

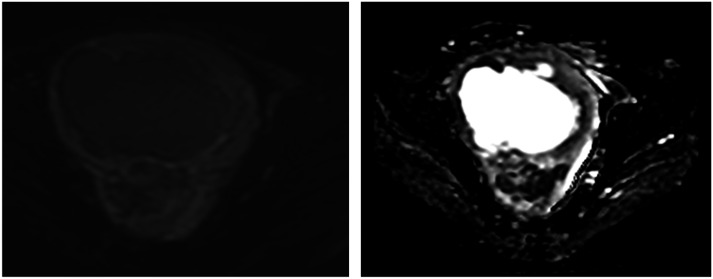

The imaging modality of choice for adequate tumor characterization is contrast magnetic resonance, which allows to measure the size of the mass, the specific nerves from which it arises and the relation to adjacent organs. Other typical features include isointense appearance compared to the spinal cord, with contrast enhancement on T1-weighted images, hyperintense, or heterogeneous appearance on T2; diffusion imaging will show diffusion restriction of the solid component of the tumor, as evidenced in the case of our patient. 3 (Figures 4 and 5)

Figure 4.

Diffusion and ADC map with diffusion restriction in the solid peripheral area.

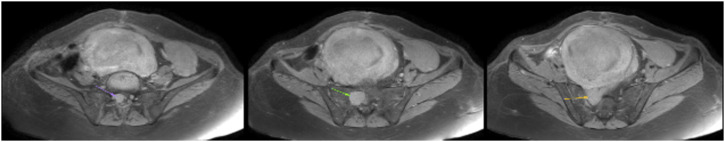

Figure 5.

T1-weighted axial images showing hypointense gadolinium-enhancing peripheral areas. Tumor protruding from the sacral foramen.

Heterogeneous T2 signals with cystic or hemorrhagic are found more frequently in the Antoni B histologic type. Two theories have been proposed to explain these changes: the first relates to the large size of the tumor resulting in central tumoral vascular insufficiency leading to necrotic and hemorrhagic changes, and the second is that Antoni B cells give rise to the production of protein components and cyst formation, as was the case in our patient.1,5

Other differential diagnoses must be borne in mind, including neurofibroma, chordoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, which are associated with radiological findings that can help guide their differentiation (Table 2). 6

Table 2.

| Characteristics | Schwannoma | Neurofibroma | Chordoma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Benign | Benign | Malignant |

| Origin | Schwann cells | Schwann cells | Notochord remnants |

| Extension | No extension to neighboring tissues, mass eccentric to the nerve | Mass central to the nerve with no extension to neighboring tissues | Large expanding and destructive osteolytic lesion |

| Radiological characteristics | Hypo or isointense on T1, hyperintense and heterogenous on T2, target sign^ and fascicular sign a | Hypointense on T1, hyperintense on T2, target sign and fascicular sign | Peripheral amorphous calcifications inside the vertebral body Low-to-intermediate MRI signal on T1 sequences, hyperintensity on T2 |

Despite low incidence, sacral schwannomas do occur, highlighting the importance of this case report, which provides guidance for suspecting the diagnosis, identifying imaging features and knowing the test of choice for better characterization, contrast magnetic resonance being the test with better yield. Moreover, this information can help with the rigorous and correct planning for future intervention in these patients, avoiding unnecessary urgent surgical procedures or diagnoses that are inconsistent with the nature of the tumor.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Nicolás Bastidas https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8561-8878

References

- 1.Crist J, Hodge JR, Frick M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of schwannomas from head to toe: a pictorial review. J Clin Imaging Sci 2017; 7(38): 38. DOI: 10.4103/jcis.jcis_40_17. 10.4103/jcis.jcis_40_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.López Lombana A del P, Hurtado Giraldo H. La célula de Schwann. Biomédica 1993; 13(4): 207. DOI: 10.7705/biomedica.v13i4.2075. 10.7705/biomedica.v13i4.2075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Se Jeong J, See Sung C, Hye-Won K, et al. A purely cystic giant sacral schwannoma mimicking a bone cyst: a case report. J Korean Soc Radiol 2014; 71(1): 1–5. DOI: 10.3348/jksr.2014.71.1.1. 10.3348/jksr.2014.71.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaman FD., Kransdorf MD, Mark J, et al. Schwannoma: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheikh MM. Schwannoma Statpearls 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beatriz Leiva Pomacahua . In, Pastor Sanchez C, Pastor Sanchez C, Rojo Trujullo M, Rojo Trujullo M, Sanchez Neila B, Sanchez Neila B. (eds). Schwannomas: Localizaciones Típicas y Atípicas. Pune, India. SERAM, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pongsthorn C, Ozawa H, Aizawa T, et al. Giant sacral schwannoma: a report of six cases. Ups J Med Sci 2010; 115(2): 146–152. DOI: 10.3109/03009730903359674. 10.3109/03009730903359674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García Ortega AA, Martinez Paredes Y, Abellán Rivero D, et al. Patología Tumoral En El Sacro: Tumores Óseos Benignos y Malignos. 2018; Seram. Available at: https://piper.espacio-seram.com/index.php/seram/article/view/2151. [Google Scholar]