Abstract

We developed a new fluorescent analog of cytosine, the 4-amino-1H-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one, which constitute a probe sensitive to pH. The 2′-O-Me ribonucleoside derivative of this heterocycle was synthesized and exhibited a fluorescence emission centered at 456 nm, characterized by four major excitation maxima (250, 300, 320 and 370 nm) and a fluorescence quantum yield of Φ = 0.62 at pH 7.1. The fluorescence emission maximum shifted from 456 to 492 nm when pH was decreased from 7.1 to 2.1. The pKa (4) was close to that of cytosine (4.17). When introduced in triplex forming oligonucleotides this new nucleoside can be used to reveal the protonation state of triplets in triple-stranded structures. Complex formation was detected by a significant quenching of fluorescence emission (∼88%) and the N-3 protonation of the quinazoline ring by a shift of the emission maximum from 485 to 465 nm. Using this probe we unambiguously showed that triplex formation of the pyrimidine motif does not require the protonation of all 4-amino-2-one pyrimidine rings.

INTRODUCTION

Triple helix formation can be used to target double-stranded DNA through the binding of a short oligonucleotide to homopurine–homopyrimidine sequences via Hoogsteen (or reverse Hoogsteen) hydrogen bonding (1,2). A triple helical approach can also be used to target a single-stranded DNA or RNA sequence using an oligonucleotide able to form both Watson–Crick and Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds (3,4). Thus in triple helices of the pyrimidine motif a third pyrimidine strand interacts with the Watson–Crick double strand forming CG*C+ and TA*T base triplets (in this notation the third strand is written in the last position and * indicates Hoogsteen type interaction). However, the requirement for the protonation of cytosine residues in the third strand results in a pH-dependent stability of PyPu*Py triplexes with an optimum stability at non-physiological pH 5.0–6.0 (5).

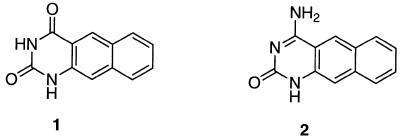

In recent studies on triplexes, we developed a new fluorescent analog of thymine which enabled us to probe triple helix formation, the benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(1H,3H)-dione 1 (Fig. 1) (6,7). Taking into account the luminescent properties of this heterocycle, we surmised that 2 (4-amino-1H-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one), an analog of cytosine could exhibit similar properties and that N-3 protonation would induce variations of these fluorescence capacities.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of heterocycles 1 and 2.

In this communication we show that 2 constitutes a fluorescent probe sensitive to pH, able to detect complex formation. It can be used to reveal easily the protonation state of triplets in triple-stranded structures. The benzo[g]quinazoline heterocycles 1 and 2 were introduced on a 2′-O-methylribose backbone. We report the complete synthetic routes for the 2′-O-Me-ribonucleosides of 1 and 2 (1N and 2N), as well as the corresponding phosphoramidites allowing the synthesis of modified oligonucleotides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Merck silica gel 60F254 aluminium-backed plates; visualization was done by UV illumination and staining with 10% perchloric acid solution. Flash chromatography refers to column chromatography performed with Merck silica gel 60 (0.04–0.063 mm).

The NMR spectra were recorded on a Brüker AC 200 spectrometer working at 200 MHz for 1H, 50.32 MHz for 13C and 81.02 MHz for 31P. The ROESY, HMQC and HMBC experiments were performed on a Brüker AMX 500 spectrometer. The chemical shifts are expressed in p.p.m. using TMS as an internal standard (1H and 13C data) and 85% H3PO4 as an external standard (31P data). The IR data and UV spectra were recorded on a Brüker UFS-25 spectrofluorimeter and on a Kontron Uvikon 940 spectrophotometer, respectively. All chemical reagents were obtained from Aldrich (St Quentin Fallavier, France) except ammonium sulfate (Fluka, St Quentin Fallavier, France) and sodium metal (Prolabo, Fontenay Sous Bois, France).

Chemical synthesis

1-(2,3,5-tri-O-benzoyl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (4). A mixture of benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-dione 1 (7) (20.6 g, 97 mmol), a few crystals each of ammonium sulfate and acetamide and a few drops of trimethylsilylchloride were refluxed in 500 ml hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) for 3 days with exclusion of moisture. Excess HMDS was removed in vacuo by co-evaporation with toluene. The residue was dissolved in a dry mixture of acetonitrile/toluene (200/50 ml) then 1-O-acetyl-2,3,5-tri-O-benzoyl-β-d-ribofuranosyl (49 g, 97 mmol) was added. The mixture was cooled to 0°C and then 1.3 equivalents of trimethylsilyl triflate (24.4 ml) were added (30 min). The reaction mixture was then stirred at room temperature (RT) for 4 h. The solution was poured on a saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution and the product extracted into toluene (3 × 100 ml). The organic phase was washed with saturated aqueous NaCl and then dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solid residue was purified by flash chromatography with dichloromethane/methanol (97.5/2.5) as eluent affording 41.35 g of pure benzoylated nucleoside 4 (65% yield). Rf = 0.52 (5/95 methanol/chloroform). 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 4.65–4.85 (3H, m, H4′, 5′ and 5″); 6.25 (1H, t, J = 6.5 Hz, H3′); 6.35 (1H, dd, J = 2 and 6.5 Hz, H2′); 6.70 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz, H1′); 7.35–8.15 (19H, m, H6, 7, 8, 9 and Bz); 8.20 (1H, s, H10); 8.75 (1H, s, H5); 11.85 (1H, bs, H3). 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 63.40 (C5′); 70.30 (C2′*); 73.35 (C3′*); 78.05 (C4′); 89.30 (C1′); 111.15 (C10); 116.05 (C4a); 125.85 (C5a); 127.45 (C9); 128.6–129.25 (C5, 7, 8 and Bz); 133.40 (C9a**); 133.70 (C10a**); 136.10 (Cq Bz); 149.85 (C2); 161.75 (C4); 164.65, 164.85 and 165.50 (Ccarbonyl). (** assignments may be reversed.)

1-(β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (5). A solution of 3.3 equivalent of sodium methylate (50 ml) was poured into a suspension of compound 4 (9.9 g, 15.2 mmol) in dry methanol (250 ml) and the mixture stirred for 1 h at RT. The solution was neutralized by 1 N HCl. The precipitate was washed with water then dissolved in dry pyridine and co-evaporated twice with pyridine. The concentrated pyridine solution was poured into CHCl3 and the white precipitate filtered and carefully dried under vacuum to give 9.6 g of a white powder (97% yield). Rf = 0.25 (10/90 methanol/chloroform) 1H NMR: (200 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 3.80 (2H, m, H5′ and 5″); 3.90 (1H, m, H4′); 4.25 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, H3′); 4.65 (1H, t, J = 6 Hz, H2′); 4.95 (1H, bs, OH3′); 5.15 (2H, bs, OH2′ and 5′); 6.30 (1H, d, J = 6 Hz, H1′); 7.50 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H7); 7.65 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H8); 7.95 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H9); 8.10 (1H, d, J= 8 Hz, H6); 8.35 (1H, s, H10); 8.70 (1H, s, H5); 11.6 (1H, s, H3). 13C NMR: (50 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 61.05 (C5′); 68.40 (C2′); 68.80 (C3′); 84.70 (C4′); 89.75 (C1′); 113.40 (C10); 116.50 (C4a); 125.65 (C5a); 127.40 (C9); 127.95 (C7); 129.00 (C5, 6 and 8); 135.10 (C9a); 135.95 (C10a); 150.35 (C2); 161.60 (C4).

1-(β-d-ribofuranosyl)-2,2′-anhydro-benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (6). Compound 5 (12 g, 34.9 mmol) was dissolved in 40 ml of anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) with 1.2 equivalent of diphenyl carbonate (9 g) and NaHCO3 (85 mg). The solution was stirred for 2 h at 70°C. It was then concentrated and poured onto dichloromethane (200 ml). After cooling to 4°C the white precipitate was filtered and dried (6.8 g, 79% yield). Rf = 0.14 (10/90 methanol/chloroform). 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 3.30 (2H, m, H5′ and 5″); 4.20 (1H, bs, H4′); 4.50 (1H, bs, H3′); 5.40 (1H, d, J = 6 Hz, H2′); 6.80 (1H, d, J = 6Hz, H1′); 7.55 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H7); 7.65 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H8); 8.00 (1H, s, H10); 8.05 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H9); 8.15 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H6); 8.70 (1H, s, H5). 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 60.80 (C5′); 74.80 (C3′); 88.55 (C4′*); 88.75 (C2′*); 89.15 (C1′*); 111.10 (C10); 116.90 (C4a); 126.60 (C9); 127.00 (C7).

1-(2-O-methyl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (1N). In a 75 ml stainless steel unstirred pressure reactor were combined 6 (307 mg, 0.94 mmol), trimethyl borate (211 µl, 1.88 mmol), trimethyl orthoformate (103 µl, 0.94 mmol), a catalytic amount of NaHCO3 and anhydrous methanol (5 ml). The vessel was sealed and placed in an oil bath for 38 h. The reaction mixture was cooled and concentrated to a white solid (327 mg, 97% yield). Rf = 0.30 (10/90 methanol/chloroform). The poor solubility of 1N in all standard NMR solvent precluded all NMR measurements.

1-(2-O-methyl-5-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinaoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (7). 1N (1.55 g, 4.35 mmol) was dried by three co-evaporations with anhydrous pyridine and then dissolved in anhydrous pyridine (15 ml). 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl chloride (1.1 equivalent, 1.62 g) in anhydrous pyridine (10 ml) was then added. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at RT under argon. The reaction was stopped with methanol (2 ml) and the solution concentrated. The corresponding oil was purified by flash chromatography along a slight gradient of methanol/dichloromethane (0–1.5% with 1% triethylamine) and yielded 1.55 g of 7 (58% yield). Rf = 0.52 (MeOH/CHCl3: 5/95). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 2.95 (1H, bs, OH3′); 3.48 (3H, s, H3CO2′); 3.52 (1H, dd, J = 5.3 and 10.5 Hz, H5′); 3.56 (1H, dd, J = 3.2 and 10.5 Hz, H5″); 3.69 (3H, s, CH3O-DMT); 3.70 (3H, s, CH3-DMT); 4.10 (1H, m, H4′); 4.64 (1H, dd, J = 3.6 and 6.7 Hz, H2′); 4.75 (1H, bs, H3′); 6.29 (1H, d, J = 3.6 Hz, H1′); 6.74–6.76 (4H, Harom. DMT); 7.16–7.48 (11H, m, H7, 8 and arom. DMT); 7.61 (1H, d, J = 7 Hz, H9); 7.92 (1H, s, H10); 7.95 (1H, d, J = 7 Hz, H6); 8.86 (1H, s, H5); 9.66 (1H, s, H3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 55.04 (CH3O-DMT); 58.84 (H3CO2′); 69.98 (C3′); 80.25 (C2′); 83.43 (C4′); 86.32 (Cq DMT); 89.80 (C1′); 112.14 (CHarom.); 113.02 (C10); 115.94 (C4a); 126.14–126.68–127.66–127.74–129.04–129.08–130.21 (C4a, 5a, 7, 8, 10 and DMT); 128.38 (C9); 129.62 (C6); 130.81 (C5); 135.80–135.91–135.96 136.62 (C9a, 10a and Cq DMT); 144.73 (Cq DMT); 149.61 (C2); 158.43 (Cq DMT); 162.12 (C4).

1-(2-O-methyl-3-O-(2-cyanoethoxy(diisopropylamio)-phosphino)-5-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (8). 7 (300 mg, 0.45 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane (stabilized with 0.002% amylene) (2 ml). 2.5 equivalents of diisopropylethylamine (198 µl) and 1.5 of 2-cyanoethyl diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite (203 µl) were added and stirred for 2 h at RT. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1-butanol (33 µl). The solution was diluted with dichloromethane (20 ml) and washed twice with water and concentrated. The phosphoramidite was purified by flash chromatography with hexane/ethyl acetate/triethylamine (3/6/1) as eluent yielding 284 mg of pure phosphoramidite (73% yield). Rf = 0.6 (5/95 methanol/chloroform); HR-FAB: calcd for C48H52N3O9P (M-1) 859.347193 found 859.346835 (M-H)–.1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 1.10–1.20 [12H, m, (CH3)2CHN]; 2.65 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, CH2CN); 3.40–3.65 [4H, m, H5′ and 5″. NCH(CH3)2]; 3.50 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.60 (6H, s, CH3O-DMT); 3.80–4.00 (2H, m, CH2OP); 4.75 (1H, m, H4′); 4.65–4.95 (2H, m, H2′ and 3′); 6.20 (1H, d, J = 3.5 Hz. H1′); 6.70 (4H, t, J = 9 Hz, CHDMT); 7.10–7.50 (18H, m, H6, 7, 8, 9. CHBz and DMT); 7.95 (1H, s, H10); 8.80 (1H, s, H5). RMN 13C (50 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 20.25 (CH2CN); 24.55 [NCH(CH3)2]; 43.25 [NCH(CH3)2]; 55.05 (CH3O-DMT); 58.00 (CH3O2′); 58.65 (d, 2JCP = 18.1 Hz, CH2OP); 63.20 (C5′); 70.85 (d, 2JCP = 16.7 Hz, C3′); 80.10 (C2′); 82.45 (C4′); 86.25 (Cq DMT); 90.00 (C1′); 112.60 (C10); 112.95 (CHDMT); 115.90 (C4a); 117.80 (CN); 126.15–126.75–127.65–127.80–128.35–128.45–129.05–129.65–130.25–130.70–135.80–136.10–136.25–136.70 (C5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 9a and 10a, CDMT); 144.65 (Cq DMT); 149.10 (C2); 158.40 (Cq DMT); 161.65 (C4). RMN 31P (80.02 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 148.40; 149.10.

1-(2-O-methyl-3,5-O-di-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(3H)-dione (9). Compound 1N (11.65 g, 32.5 mmol) and imidazole (6.64 g, 97.5 mmol) were dissolved in 150 ml of anhydrous DMF and t-butyldimethyl-silyl chloride (14.7 g, 97.5 mmol) added to the stirred solution at RT. After 18 h the solution was concentrated into a small volume and portioned between 200 ml of dichloromethane and 50 ml of saturated aqueous NaCl. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The filtrate was evaporated to give an oil which was purified by flash chromatography. The desired product was eluted with the mixture hexane/ethyl acetate (8/2) as a white solid (14.1 g, 74% yield). Rf = 0.32 (hexane/AcOEt: 8/2). 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 0.00 (3H, s, CH3Si); 0.05 (3H, s, CH3Si); 0.15 (6H, s, CH3Si); 0.85 [9H, s, (CH3)3CSi]; 0.95 [9H, s, (CH3)3CSi]; 3.40 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.80–4.05 (3H, m, H4′, 5′ and 5″); 4.65 (1H, dd, J = 3.4 and 6.1 Hz, H2′); 4.70 (1H, t, J = 6.1 Hz, H3′); 6.05 (1H, d, J = 3.4 Hz, H1′); 7.50 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H7); 7.60 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H8); 7.80 (1H, s, H10); 7.85 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H9); 7.90 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H6); 8.80 (1H, s, H5); 9.60 (1H, s, H3). 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): –5.30/–4.85/–4.60 (CH3Si); 18.15/18.45 [(CH3)3CSi]; 25.80/25.85 [(CH3)3CSi]; 58.40 (CH3O2′); 62.75 (C5′); 70.45 (C3′); 80.70 (C2′); 83.95 (C4′); 90.50 (C1′); 111.95 (C10); 115.80 (C4a); 126.05 (C9); 127.70 (C7); 129.00 (C8*); 129.15 (C5*); 129.50 (C5a); 130.65 (C6); 136.55 (C9a**); 136.70 (C10a**); 149.30 (C2); 162.30 (C4).

1-(2-O-methyl-3,5-O-di-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-4-triazolo-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one (10). 1,2,4-triazole (1.8 g, 26 mmol) was suspended in 20 ml of anhydrous CH3CN at 0°C. 0.56 ml (6.1 mmol) of POCl3 then 4.2 ml of triethylamine were added slowly. After 1 h compound 9 (1.1 g, 1.74 mmol) in 20 ml of THF was added over 20 min. The solution was stirred for 16 h at RT, then concentrated and partitioned between 100 ml of CH2Cl2 and 20 ml saturated aqueous NaCl. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and the solvent evaporated. The residue was dried by repeated evaporation of a toluene solution to give a slightly yellow solid (1.14 g, 95% yield) which was used without further purification. Rf = 0.54 (Et2O/hexane: 3/1). 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): –0.10 (3H, s, CH3Si); –0.05 (3H, s, CH3Si); 0.10 (6H, s, CH3Si); 0.80 [9H, s, (CH3)3CSi]; 0.90 [9H, s, (CH3)3CSi]; 3.35 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.70/4.10 (3H, m, H4′, 5′ and 5″); 4.70 (1H, dd, J = 3.2 and 5.6 Hz, H2′); 4.75 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, H3′); 6.00 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz, H1′); 7.44 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H7); 7.55 (1H, t, J = 8 Hz, H8); 7.80 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H9); 7.85 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H6); 7.90 (1H, s, H10); 8.25 (1H, s, H5); 9.30 (1H, s, Htriazole); 9.65 (1H, s, Htriazole). 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): –5.50/–5.00/–4.75 (CH3Si); 17.95/18.20 [(CH3)3CSi]; 25.70 [(CH3)3CSi]; 58.25 (CH3O2′); 62.80 (C5′); 70.85 (C3′); 80.35 (C2′); 84.35 (C4′); 91.05 (C1′); 109.85 (C10); 111.30 (C4a); 125.95 (C7); 127.25 (C9); 128.45 (C5*); 129.85 (C5a*); 130.55 (C6*); 132.15 (C8*); 136.55 (C9a**); 136.65 (C10a**); 145.70 (CHtriazole); 153.05 (C2); 154.10 (CHtriazole); 157.05 (C4).

1-(2-O-methyl-3,5-O-di-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-4-N-benzoyl-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one-4-amino (11). To a stirred solution of compound 10 (1.11 g, 1.74 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (20 ml) was added a mixture of NaH (95%, 0.183 g, 6.96 mmol) and benzamide (0.877 g, 6.96 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (30 ml) in one portion at RT under an argon atmosphere. After 7 h the reaction mixture was cooled (ice bath) and the solution neutralized with dropwise addition of glacial acetic. The reaction mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2 (50 ml) and washed with saturated aqueous NaCl. The CH2Cl2 layer was dried (MgSO4) and evaporated to provide a foamy residue. Flash chromatography of the residue with diethyl ether/hexane (1/3) provided 11 (0.75 g, 62% yield). Rf = 0.48 (Et2O/hexane: 1/3). 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 0.00 (3H, s, CH3Si); 0.05 (3H, s, CH3Si); 0.20 (6H, s, CH3Si); 0.90 [9H, s, (CH3)3CSi]; 1.00 [9H, s, (CH3)3CSi]; 3.45 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.80–4.10 (3H, m, H4′, 5′ and 5″); 4.70 (1H, dd, J = 3.2 and 5.8 Hz, H2′); 4.80 (1H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, H3′); 6.05 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz, H1′); 7.45–7.60 (5H, m, H7, 8 and Bz); 7.75 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H9); 7.80 (1H, s, H10); 8.00 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H6); 8.40 (2H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, HBz); 9.10 (1H, s, H5); 12.85 (1H, bs, C4NHBz). 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): –5.35/–4.85/–4.60 (CH3Si); 18.15/18.35 [(CH3)3CSi]; 25.85 [(CH3)3CSi]; 58.45 (CH3O2′); 62.65 (C5′); 70.55 (C3′); 80.75 (C2′); 83.95 (C4′); 90.60 (C1′); 111.70 (C10); 115.90 (C4a); 126.00 (C9); 127.55 (C7); 128.15/129.55 (CHBz); /129.00/129.20/130.00/132.75 (C5, 5a, 6, 8, CHBz and Cq Bz); 136.70 (C10a*); 136.75 (C9a*); 146.95 (C2); 157.50 (C4); 179.60 (Ccarbonyl Bz).

1-(2-O-methyl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-4-N-benzoyl-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one 4-amino (12). Compound 11 (0.60 g, 1.3 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF and 2.5 ml of tetrabutylammonium fluoride in THF (0.1 M) was added. The solution was stirred at RT for 3 h. The solution was concentrated and flash chromatographied along a gradient of methanol/dichloromethane (0–4%) and yielded compound 12 (0.34 g, 82% yield). Rf = 0.13 (MeOH/CH2Cl2: 5/95). 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6), (p.p.m.): 3.30 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.70–3.95 (3H, m, H4′, 5′ and 5″); 4.40 (1H, t, 5.3 Hz, J = 5.3 Hz, H2′); 4.50 (1H, t, 5.3 Hz, J = 5.3 Hz, H3′); 5.15 (1H, bs, OH3′); 5.20 (1H, bs, OH5′); 6.40 (1H, d, 5.3 Hz, J = 5.3 Hz, H1′); 7.50–7.70 (5H, m, H7, 8 and Bz); 8.00 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H9); 8.20 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz, H6); 8.35 (2H, d, J = 6.7 Hz, HBz); 8.40 (1H, s, H10); 9.20 (1H, s, H5); 12.45 (1H, bs, C4NHBz). 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6), (p.p.m.): 57.80 (CH3O2′); 60.80 (C5′); 68.25 (C3′); 78.60 (C2′); 84.90 (C4′); 88.55 (C1′); 111.40 (C10); 115.85 (C4a); 126.10 (C9); 127.65 (C7); 128.45 (CHBz); 128.65 (C5*); 128.95 (C5a*); 129.20 (C6*); 129.55 (C8*); 129.75 (CHBz); 133.00 (Cq Bz); 134.90 (Cq Bz); 136.00 (C10a**); 136.35 (C9a**); 147.90 (C2); 154.95 (C4); 178.25 (Ccarbonyl Bz).

1-(2-O-methyl-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one 4-amino (2N). Compound 12 (0.244 g, 0.53 mmol) was stirred in a mixture of DMF/38% aqueous ammonium hydroxide (10 ml) (2/1) for 1 h at RT. Flash chromatography over silica gel along a gradient of methanol/dichloromethane (0–20%) yielded compound 2N (0.19 g, 56% yield). Rf = 0.28 (MeOH/CH2Cl2: 15/85). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 3.24 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.66 (1H, m, H5′); 3.76 (1H, m, H5″); 3.85 (1H, m, H4′); 4.37 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, H2′); 4.44 (1H, q, J = 5.6 Hz, H3′); 4.96 (1H, d, J = 5.6 Hz, OH3′); 5.02 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, OH5′); 6.36 (1H, d, J = 5.6 Hz, H1′); 7.48 (1H, t, J = 8.3 Hz, H7); 7.59 (1H, t, J = 8.3 Hz, H8); 7.89 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, H6); 7.93 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, H9); 8.1 and 8.3 (2H, bs, C4NH2); 8.17 (1H, s, H10); 8.80 (1H, s, H5). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (p.p.m.): 57.51 (CH3O2′); 61.09 (C5′); 68.61 (C3′); 78.65 (C2′); 84.46 (C4′); 88.73 (C1′); 111.28 (C4a); 111.41 (C10); 125.18 (C7); 125.63 (C5); 127.29 (C9); 127.56 (C5a); 128.38 (C8); 128.66 (C6); 135.43 (C9a); 137.25 (C10a); 155.27 (C2); 163.12 (C4).

1-(2-O-methyl-5-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-4-N-benzoyl-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one-4-amino (13). Compound 12 (0.690 g, 1.5 mmol) was treated with dimethoxytrityl chloride (1.1 equivalent) in 25 ml of anhydrous pyridine for 24 h. The solution was then evaporated, then diluted with CH2Cl2 (50 ml) and washed with saturated aqueous NaCl. The CH2Cl2 layer was dried (MgSO4) and co-evaporated with toluene to give a solid residue then purified by flash chromatography along a gradient of methanol/dichloromethane (0–4%) to provide compound 13 (0.34 g, 84% yield). Rf = 0.24 (MeOH/CH2Cl2; 3/97). 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 3.30 (1H, bs, OH3′); 3.50 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.60 (2H, m, H5′ and 5″); 4.15 (1H, m, H4′); 4.70 (1H, dd, J = 3.1 and 6.4 Hz, H4′); 4.80 (1H, m, H3′); 6.25 (1H, d, J = 3.1 Hz, H1′); 6.70 (4H, t, J = 9 Hz, CHDMT); 7.10–8.65 (18H, m, H6, 7, 8, 9, DMT and Bz); 7.95 (1H, s, H10); 9.15 (1H, s, H5); 12.90 (1H, s, C4NHBz). 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 58.70 (CH3O2′); 63.40 (C5′); 69.95 (C3′); 80.40 (C2′); 83.11 (C4′); 89.85 (C1′); 111.75 (C10); 112.85 (CHDMT); 115.70 (C4a); 123.60–126.05–126.60–127.55–128.15–128.90–129.00–129.65–129.90–132.75 (C5, 5a, 6, 7, 8, 9, CDMT and CBz); 130.05 (CHDMT); 135.75 (Cq DMT); 135.85 (C10a*); 136.60 (C9a*); 144.60 (Cq DMT); 146.95 (Cq Bz); 149.45 (C2); 157.15 (Cq DMT); 158.25 (C4); 179.55 (Ccarbonyl Bz).

1-(2-O-methyl-3-O-(2-cyanoethoxy(diisopropylamio)-phosphino)-5-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-4-N-benzoyl-benzo[g]quinazoline-2-one-4-amino (14). To a stirred solution of compound 13 (200 mg, 0.26 mmol) in 3 ml of anhydrous CH2Cl2 at RT was added diisopropylethylamine (0.14 ml, 0.78 mmol) and 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropyl-chlorophosphoramidite (0.137 ml, 0.52 mmol). After 90 min the reaction was stopped by addition of n-butanol (3 equivalents) and further stirred for 1h. The solution was diluted with CH2Cl2 and washed with saturated aqueous NaCl. The CH2Cl2 layer was dried (MgSO4) and co-evaporated with toluene (50 ml) to give a solid residue. This solid was purified by flash chromatography using hexane/ethyl acetate/triethylamine (3/6/1) as a first eluent. The desired product was then eluted with CH2Cl2/triethylamine (9/1). The product was co-evaporated twice with dry pyridine and toluene to afford a white foamy solid (0.174 g, 69% yield); Rf = 0.38 (hexane/ethyl acetate, 7/3); FAB: calcd for C55H58N5O9P 963.397218 found 963.398664. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 1.05–1.35 [12H, m, (CH3)2CHN]; 2.70 (2H, m, CH2CN); 3.30–3.40 (1H, m, H5′); 3.50 (3H, s, CH3O2′); 3.60–3.70 (1H, m, H5″); 3.65 (12H, s, CH3O-DMT); 3.80–4.00 (2H, m, CH2OP); 4.35 (1H, m, H4′); 4.80–5.05 (2H, m, H2′ and 3′); 6.15 (1H, d, J = 2.6 Hz, H1′); 6.70 (4H, t, J = 9 Hz, CHDMT); 7.10–8.45 (18H, m, H6, 7, 8 and 9, CHBz and CHDMT); 8.05 (1H, s, H10); 9.20 (1H, s, H5); 12.90 (1H, bs, N4HBz). 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 21.15 (CH2CN); 24.45 [(CH3)2CHN]; 24.55 [(CH3)2CHN]; 43.15 [(CH3)2CHN]; 43.35 [(CH3)2CHN]; 54.90 (CH3O-DMT); 58.10 (CH3O2′); 58.85 (d, 2JCP = 9.6 Hz, CH2OP); 62.70 (C5′); 70.90 (d, 2JCP = 16.8 Hz, C3′); 80.60 (C2′); 82.20 (C4′); 86.05 (Cq DMT); 90.35 (C1′); 112.25 (C10); 112.80 (CHDMT); 115.95 (C4a); 117.80 (CN); 126.10–126.60–127.55–128.20–129.05–129.15–129.65–130.00–130.05–132.75–135.70–135.80–136.35–136.50–136.75 (C5, 5a, 6, 7, 8, 9, 9a and 10a, CBz and CDMT); 144.60 (Cq DMT); 146.85 (C2); 157.45 (Cq DMT); 158.25 (C4); 179.70 (Ccarbonyl Bz). RMN 31P (80 MHz, CDCl3), δ (p.p.m.): 147.60; 147.95.

Oligonucleotide synthesis

All oligonucleotides were synthesized on a 0.2 µmol scale on a Millipore Expedite 8909 DNA synthesizer using conventional β-cyanoethyl phosphoramidite chemistry. The modified and standard bases were dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile (0.1 M final concentration). 2′-O-methyl monomers were purchased from Eurogentec (Glen Research, Sterling, VI). The coupling time for 2′-O-Me monomers (modified or unmodified) was increased up to 20 min. All oligomers were synthesized ‘trityl on’. After synthesis the solid support was treated overnight at 55°C with fresh concentrated NH4OH (3 ml). The solution was then collected and concentrated to dryness. The crude tritylated oligonucleotide was purified by reverse phase HPLC (Nucleosil 300–5 C16 column) using the following gradient: A (0.1 M triethylamonium acetate at pH 7); B (0.1 M triethylamonium acetate at pH 7 in 80% acetonitrile). A linear gradient of 0–60% buffer B over 60 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min was used. Elution was monitored by UV absorption at 260 nm for analytical runs and 290 nm for preparative ones. Finally, oligonucleotides were precipitated using n-butanol. When required aliquots of purified oligonucleotides were analyzed by gel electrophoresis to confirm expected length and purity. When necessary, oligomers were purified by preparative electrophoresis and were visualized by UV Shadowing.

UV-monitored melting experiments (Tm)

Purified oligonucleotides (0.5 nmol of each strand) were dissolved in 0.5 ml of the appropriate buffer, and the mixture was boiled for 2 min. The buffer for all studies was 10 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM spermine, 10 mM magnesium acetate. At low pH (<5) 10 mM cacodylate was substituted by a 10 mM citric acid-sodium phosphate buffer. Melting experiments (Tms) were performed on a Cary 1E UV-visible spectrophotometer with a temperature controller unit. Samples were kept at 4°C for at least 30 min and then heated from 4 to 90°C at a rate of 0.5°C/min. The absorbance at 260 nm was measured every 2 min. At 260 nm, a molar extinction coefficient of 4.98 × 104 mol–1cm–1 was used for base 1 and 5.2 × 104 mol–1cm–1 for 2.

Fluorescence measurements

The buffer for fluorescence measurements was the same as the one used for Tm experiments (see above). The fluorescence spectra were recorded on a PTI spectrofluorimeter and were corrected for both emission and excitation. Temperature was adjusted at 20°C unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemical synthesis of modified nucleosides

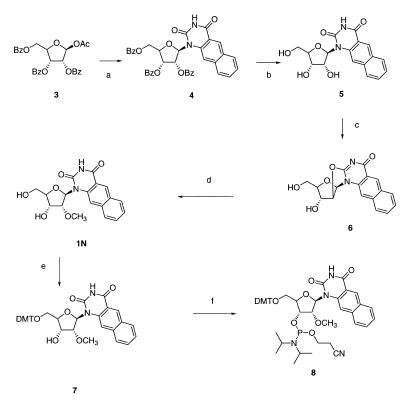

The synthetic routes for nucleosides of 1 and 2 (1N and 2N, respectively) as well as the pathway for their corresponding phosphoramidites are depicted in Schemes 1 and 2, respectively. A key step in the synthesis of ribonucleosides 1N and 2N was the selective alkylation in the 2′ position. In that aim we used the highly efficient procedure developed by Ross for the synthesis of 2′-O-methyluridine (8). This method relies on the opening of the O2,2′-anhydrouridine by trimethyl borate in hot methanol. We successfully extended this procedure to the benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(1H,3H)-dione ribonucleoside. 2N was then obtained from 1N following classical activation through a 4-triazolo derivative (9). The commercially available β-d-ribofuranose-1-acetate-2,3,5-tribenzoate 3 was glycosylated according to Vorbrüggen (10) with the silylated derivative of the benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4-(1H,3H)-dione (7) using trimethylsilyl triflate as a catalyst. Debenzoylation of 4 with sodium methoxide in methanol afforded the free nucleoside 5 in high yield (97%). The O2,2′-anhydro derivative 6 was easily obtained by treatment with diphenyl carbonate and a catalytic amount of sodium hydrogen carbonate in dimethyl formamide (11). The opening of the anhydro linkage using trimethyl borate in hot methanol (150°C) with traces of sodium bicarbonate afforded the 2′-O-methyl nucleoside 1 in high yield (91%) (8). The corresponding phosphoramidite 8 was then obtained in two steps: a 5′ monotritylation using 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl chloride in anhydrous pyridine and a phosphitylation reaction with 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (12). 8 was purified by silica gel flash chromatography using hexane/ethyl acetate/triethylamine (3/6/1, v/v/v) as the elution solvent. The overall yield from 1 was 42%.

Scheme 1. Chemical synthetic pathway for nucleoside 1N and its phosphoramidite derivative 8. Reagents and conditions: (a) Trimethylsilyl triflate, toluene, anhydrous DMF (65%); (b) CH3OH/CH3O–Na+ (97%); (c) (PhO)2CO, NaHCO3, DMF reflux (79%); (d) B(OCH3)3, HC(OCH3)3, NaHCO3, CH3OH, 50°C, (91%); (e) DMT-Cl, anhydrous pyridine (58%); (f) 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphite, diisopropylethylamine, anhydrous CH2Cl2 (73%).

Scheme 2. Chemical synthetic pathway for nucleoside 2N and its phosphoramidite derivative 14. Reagents and conditions: (a) t-BDMSSi-Cl, imidazole, DMF (74%); (b) POCl3, TEA, triazole (99%); (c) benzamide, NaH, 1,4-dioxane (62%); (d) (Bu)4N+F–, THF (84%); (e) NH4OH/DMF (1/2) (58%); (f) DMT-Cl anhydrous pyridine (55%); (g) cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphite, diisopropylethylamine, anhydrous CH2Cl2 (69%).

The structures of the various compounds reported above were checked by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, with the exception of 1N which revealed very poor solubility in standard NMR solvents. Thus the 13C NMR spectra of 6 clearly revealed the O2,2′-anhydro linkage, C-2′ chemical shift moved downfield from 68.40 p.p.m. (5) to 88.50 and the C-2 from 150.35 to 160.90 p.p.m. The 2′-O methylation was confirmed on compound 7 by long range 1H-13C correlation spectroscopy (HMBC) (13) which revealed a cross-peak between H-2′ (4.64 p.p.m.) and the CH3 group (58.84 p.p.m.) (map not shown). Furthermore the β configuration of C-1 was revealed by NOE experiments on 7 where a clear cross-peak between H-1′ and H-4′ was detected (14). Additionally, a correlation between H-1′ and the 2′-O-CH3 group confirmed the configuration at C-2′ (data not shown).

The chemical synthetic pathway for 2N is shown in Scheme 2. The 3′-OH and 5′-OH of 1N were first protected with the t-butyldimethylsilyl group in good yield and converted to the 4-triazolo derivative 10 (9). This was readily substituted by benzamide in the presence of sodium hydride in anhydrous 1,4-dioxane at room temperature (15) (62% yield after flash chromatography). After cleavage of the silyl group a part of 12 was submitted to aminolysis (aqueous ammoniac in dimethyl formamide) to obtain the free nucleoside 2N for complete characterization. Most of 12 was further converted to the phosphoramidite 14 following the same procedure as for compound 8 (overall yield 38% from 12 after flash chromatography). All the spectral characteristics of these compounds are given in Materials and Methods.

Fluorescence and thermal denaturation studies

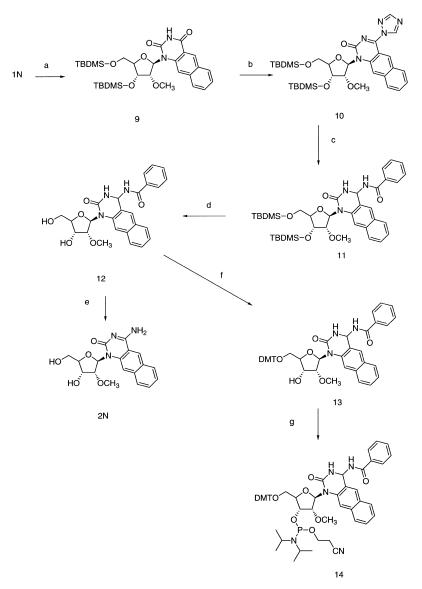

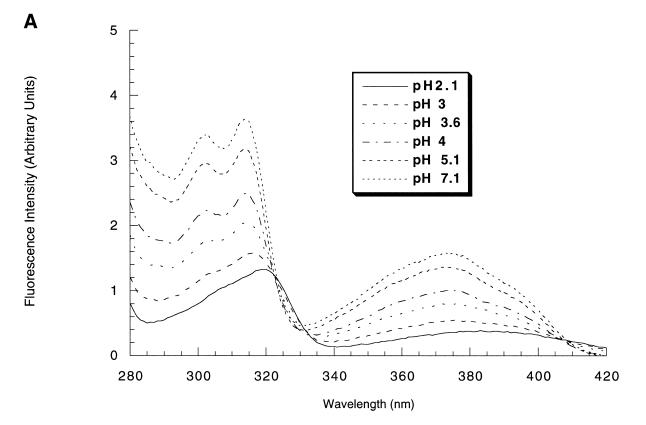

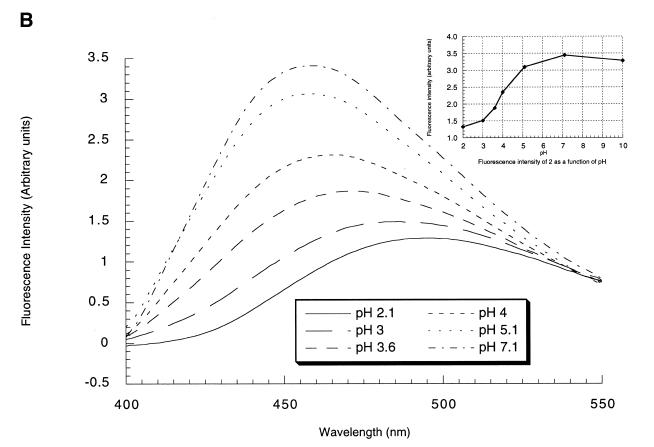

The fluorescence properties of 2N were obtained from an aqueous solution of the nucleoside (0.1 µM). This nucleoside showed at pH 7.1 a fluorescence emission centered at 456 nm characterized by four major excitation maxima: 250, 300, 313 and 370 nm. The fluorescence quantum yield Φ = 0.62 at pH 7.1 was obtained by measuring the area under the broad emission spectra (380 to 618 nm) in comparison with that of a quinine solution in 0.1 M H2SO4, (Φ = 0.51), adjusted at the same absorbance, at the excitation wavelength of 250 nm. As expected the fluorescence properties of 2N were pH-dependent. The excitation spectra (λem = 470 nm) recorded at different pH values were characterized by an isobestic point at 322 nm as expected for an equilibrium between emissive protonated and deprotonated forms (Fig. 2A). Moreover the fluorescence emission maximum shifted from 456 to 492 nm when pH was decreased from 7.1 to 2.1 (Fig. 2B). A plot of the fluorescence intensity as a function of pH allowed to determine a pKa of ∼4 for 2N (inset Fig. 2B). This pKa is in good agreement with the pKa reported for cytidine (4.17) (16) and is more basic than the 5-propyne analog of deoxycytidine (3.30) (17). Therefore 2N is a convenient heterocycle to probe protonation sites in triplex forming oligonucleotides.

Figure 2.

(A) Excitation fluorescence spectra of 2 as a function of pH. The fluorescence was recorded for an emission wavelength set at 470 nm at 0.1 µM of 2 in a 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM spermine and 10 mM magnesium acetate. At low pH (<5) 10 mM cacodylate was substituted by a 10 mM citric acid–sodium phosphate buffer. (B) Fluorescence emission spectra of 2 as a function of pH with an excitation wavelength set at 310 nm obtained under the same conditions as the excitation spectra. Inset, graphical determination of the pKa of 2: fluorescence intensity of 2 as a function of pH.

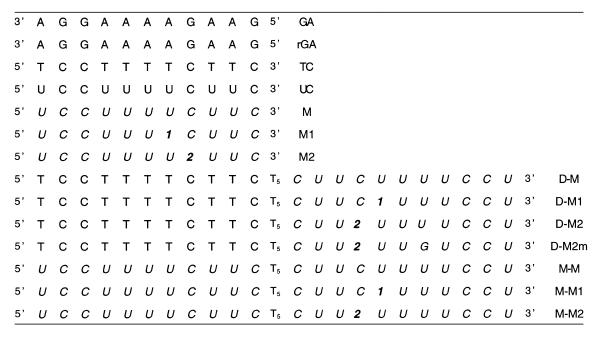

1N and 2N were incorporated into oligonucleotides using standard phosphoramidite chemistry. Oligonucleotide sequences are shown in Table 1. GA and rGA are target purine strands composed of DNA and RNA nucleotides, respectively. These target strands were conceived to form duplexes with complementary sequences of three different backbones (DNA, RNA and 2′-O-Me-RNA) abbreviated respectively D, R and M. Chimeric sequences associating different combinations of two backbone types (D, M) were also constructed to allow the formation of triple-stranded structures upon annealing with the target strands GA and rGA. The 5′ part of these chimeric oligomers (designated D-M and M-M) constitutes the Watson–Crick strand of the triplexes and the 11 3′ nucleotides, composed of 2′-O-Me-RNA backbone, constitutes the Hoogsteen strand. These two strands were linked by a (T)5 loop (DNA backbone) allowing the formation of bimolecular complexes with the targets GA and rGA. Modified nucleosides 1N or 2N were introduced either in the complementary pyrimidine strand (designated M1 and M2) or in the Hoogsteen strand of chimeric sequences (designated by the numerical index following D-M, or M-M).

Table 1. Abbreviations of the oligonucleotide sequences used in the study.

1 and 2 = benzo[g]quinazoline bases.

Italicized letters stand for 2′-O-methyl ribonucleotides and m for mismatch.

As expected the modified oligomers bearing 1N or 2N displayed strong emission properties. Thus M1 was characterized by a broad emission spectrum (λ = 437 nm, pH = 5.1) upon excitation at either 260 or 360 nm (not shown) as previously observed for the deoxyderivative. These fluorescence properties turned out to be insensitive to pH (pH range of 5.0–8.0). The M2 strand including the cytosine analog displayed a maximum emission wavelength at 453 nm (pH = 5.1) following excitation at 260 or 360 nm. The emission properties of strand D-M2 were recorded at pH from 2.1 to 7.1. The maximum emission shifted from 452 (pH 7.1) to 485 nm (pH 2) with a decrease in intensity of 32% (not shown).

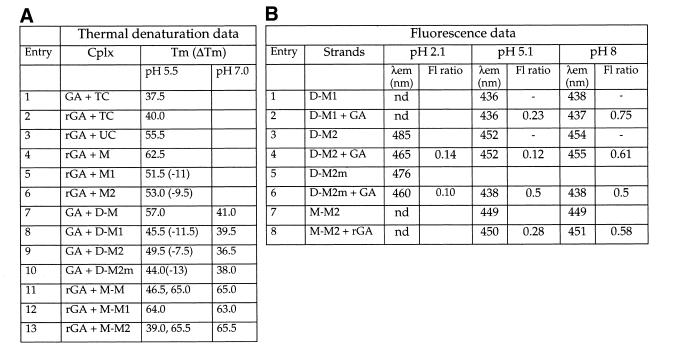

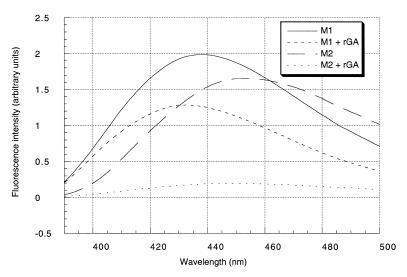

The binding properties of the modified oligomers were first checked using thermal denaturation experiments (Table 2A). The substitution of one-2′-O-Me-U nucleoside by 1N or one C by 2N resulted in a significant destabilization of the corresponding duplex with a RNA target: ΔTm = –9.5 to –11°C (entries 4 to 6), but clearly maintain the hybridization properties since Tms were higher than the corresponding DNA complementary strands (entries 1 and 2). The formation of the duplexes between rGA and M1, M2 were monitored by fluorimetry. As shown in Figure 3, these resulted in a decrease in fluorescence intensity (36 and 88% for 1N and 2N, respectively) associated with a shift of the emission maxima toward the short wavelength (5 and 10 nm). These data revealed interactions of the fluorophore upon duplex formation, supporting the base pairing properties of the modified nucleosides 1N and 2N.

Table 2. (A) Tm data of the various complexes, (B) pH-dependent emission properties of single-stranded and triple-stranded oligonucleotides.

(A) The Tms were obtained under the conditions described in Materials and Methods. Tm is the melting temperature (± 0.5°C). ΔTm = Tm (modified oligomers) – Tm (unmodified oligomers). Tm values are the average of at least three independent measurements.

(B) The fluorescence ratio is the relative fluorescence intensity (λexc 313 nm) of the complex compared to that of the unbound strand (under the same experimental conditions as Fig. 2A at 20°C)

Figure 3.

Emission spectra of M1 and M2 strands (λexc 313 nm). Effect of complex formation with the rGA strand. An aliquot of 100 nM of each oligo in the cacodylate buffer (pH 5.1).

Formation of triplexes was observed upon annealing between the GA and the various chimeric D-M oligomers. In these DD*M triplexes, the Hoogsteen strand is composed of 2′-O-Me RNA residues. The thermal denaturation studies of these complexes showed a single transition from the bound state to the dissociated state, as previously observed for similar triple-stranded structures. Experiments were carried out at pH 5.5 for these triplexes allowing N-3 protonation of Cs. The formation of the parent triplex (Table 2A, entry 7) resulted in a 19.5°C increase in Tm compared to that of the corresponding duplex (entry 1), indicating third strand contribution to the overall complex stability. The substitution of a single U residue for 1 or one C for 2 led to clear destabilization of the corresponding triplexes: ΔTm = –11.5 and –7.5°C for 1 and 2, respectively (entries 8 and 9). When a mismatch was introduced in the Hoogsteen part of the M-M2 strand (TA*G triplet, entry 10) a further destabilization was observed (ΔTm = –13°C), but the Tm was still higher than the duplex reference strand (entry 4). As expected raising the pH from 5.5 to 7 clearly destabilized all triple-stranded complexes (entries 7–10) indicating contribution of protonated Cs to their stability. Annealing between rGA and the various M-M strands (entries 11–13) led to the formation of MR*M triplexes. In that case two transitions were observed during the thermal denaturation of the unmodified complex (entry 11). The low temperature transition was assigned to the melting of the triplex (from the triple-stranded to the double-stranded structures). The higher transition (65°C) occurs slightly above that of the corresponding duplex (62.5°C, entry 4). Moreover experiments at pH 7 led to a single transition at 65°C. The substitution of one U for 1 in the Hoogsteen strand led to a single transition, we were unable to detect any low-temperature transition indicative of a triple-stranded structure. We observed only the higher one, which we assigned to the melting of the Watson–Crick strands. The substitution of one C for 2 (entry 13), led to a destabilized triplex with first transition at 39°C, i.e. 7.5°C lower than the unmodified reference triplex. In all cases thermal denaturation experiments at pH 7 led to a single transition at 65°C. With the exception of 1 in MR*M context, all substitutions of U or C by a corresponding analog (1 or 2) allowed complex formation (duplexes or triplexes). Thus 1 and 2 can be used as fluorescent analytical probes for these structures.

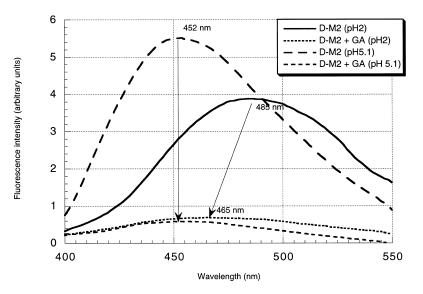

The formation of DD*M triplexes were monitored using the emission properties of probe 1 and 2 (data are gathered in Table 2B). In both cases, the main effect was a significant quenching of fluorescence emission (77 and 88%, respectively). These data reveal changes in both stacking and hydrophobic environment upon triplex formation at pH 5.1. The emission maximum observed for annealing between D-M2 and GA at pH 5.1 (452 nm) is indicative of an unprotonated state of N-3 atom of 2 when engaged in a triple-stranded structure at this pH. D-M2 strand alone at pH 5.1 (one unit above the pKa of 2N) exhibited an emission maximum of 452 nm. At pH 2, we clearly detected the N-3 protonation with a maximum at 485 nm. Upon annealing with GA, at pH 2, this maximum shifted to 465 nm and was associated with a 86% quenching of fluorescence intensity (Fig. 4). These data suggest that at this pH, the N-3 atom of 2 is protonated and that triplex formation results in a clear blue shift of 20 nm (protonation of N-3 in this complex has been confirmed by thermal denaturation experiment at pH 3, we observed in this case a further stabilization of the triple-stranded structure revealed by a 4°C increase in Tm value). At pH 5.1 annealing between M-M2 and rGA strands led to a fluorescence quenching ratio of 0.28 and a slight shift of 1 nm. When all the above-mentioned complexes were formed at pH 8, where no N-3 protonation is expected, thermal denaturation data clearly showed that triplexes are no longer formed (Table 2A). However, we still observed a quenching in fluorescence intensity but of much smaller amplitude (Table 2B). We supposed that this quenching, which indicates variations in the environment of the fluorophore upon interaction, might be due to intercalation of the benzo[g]quinazoline heterocyle into the targeted double strand. Similar observations were done in a previous study with the 2′-deoxynucleoside of 1 (7). However the fluorescence data for the mismatch strand (entry 6) at pH 5.1 and 8 were characterized by a shorter emission wavelength (438 nm), we presumed to be related to a different geometry in the environment of the chromophore.

Figure 4.

Emission spectra of the triplex forming oligomer (D-M2) upon annealing with the target strand GA. An aliquot of 100 nM of each oligo in the cacodylate buffer (pH 5.1).

The benzo[g]quinazoline derivative 2 constitutes therefore a fluorescent probe, sensitive to pH, able to detect complex formation. It can be used to reveal protonation sites in triplexes. We show here that an isolated CG*2 triplet within a pyrimidine third strand can exist in an unprotonated state. Thus triplex formation of the pyrimidine motif does not require the protonation of all 4-amino-2-one pyrimidine rings. Similar observations of partial protonation of Hoogsteen third strand were reported in the literature from studies using NMR spectroscopy or calorimetry (5,18–20). This new probe constitutes an easy way to obtain information on the protonation state of defined sites in triple-stranded structures. Further studies will consider the impact of variations in oligonucleotide sequences and changes in the local environment of the probe. Taking into account its low pKa value, the fluorescent benzo[g]quinazoline heterocycle 2 could be further revealed as a useful probe for acidic intracellular compartments, following conjugation to an appropriate vector (21).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Prof. J. Vercauteren (Laboratoire de Pharmacognosie, Université Victor Segalen, Bordeaux) for helpful discussion on NMR data, and J. Michel for skillful experimental assistance on oligonucleotide synthesis. This work was supported in part by the Biotechnology Program of the European Community and by the Conseil Régional d’Aquitaine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thuong N.T. and Hélène,C. (1993) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 32, 666–690. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radhakrishnan I. and Patel,D.J. (1994) Biochemistry, 33, 11405–11416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannangeli C., Thuong,N.T. and Hélène,C. (1993) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 10013–10017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brossalina E. and Toulmé,J.-J. (1993) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 115, 796–797. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plum G.E. and Breslauer,K.J. (1995) J. Mol. Biol., 248, 679–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godde F., Moreau,S. and Toulmé,J-J. (1998) Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 8, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godde F., Toulmé,J-J. and Moreau,S. (1998) Biochemistry, 37, 13765–13775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross B.S., Springer,R.H., Tortorici,Z. and Dimock,S. (1997) Nucl. Nucl., 16, 1641–1643. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Y-Z. and Swann,P.F. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 4061–4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vorbrüggen H. and Höfle,G. (1981) Chem. Ber., 28, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hampton A. and Nichol,A.W. (1966) Biochemistry, 5, 2076–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaucage S.L. and Iyer,R.P. (1992) Tetrahedron, 48, 2223–2311. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bax A. and Summers,M.F. (1986) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 108, 2093–2094. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michel J., Toulmé,J.J., Vercauteren,J. and Moreau,S. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1127–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perbost M. and Sanghvi,Y.S. (1994) J. Chem. Soc. [Perkin], 1, 2051–2052. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackburn G.M. and Gait,M.J. (eds) (1996) Nucleic Acids in Chemistry and Biology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, Tokyo.

- 17.Froehler B.C., Wadwani,S., Terhorst,T.J. and Gerrard,S.R. (1992) Tetrahedron Lett., 33, 5307–5310. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson W.D., Hopkins,H.P., Mizan,S., Hamilton,D.D. and Zon,G. (1994) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 3607–3608. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xodo L.E., Giorgio,M., Quadrifoglio,F., Van der Marel,G.A. and Van Boom,J. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 5625–5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leitner D., Schroder,W. and Weisz,K. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 7123–7124. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petit J.M., Denis-Gay,M. and Ratinaud,M.H. (1993) Biol. Cell, 78, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]