Abstract

Dihydropyrazole (1–22) derivatives were synthesized from already synthesized chalcones. The structures of all of the synthesized compounds were confirmed by elemental analysis and various spectroscopic techniques. Furthermore, the synthesized compounds were screened against α amylase as well as investigated for antioxidant activities. The synthesized compounds demonstrate good to excellent antioxidant activities with IC50 values ranging between 30.03 and 913.58 μM. Among the 22 evaluated compounds, 11 compounds exhibit excellent activity relative to the standard ascorbic acid IC50 = 287.30 μM. Interestingly, all of the evaluated compounds show good to excellent α amylase activity with IC50 values lying in the range between 0.5509 and 810.73 μM as compared to the standard acarbose IC50 = 73.12 μM. Among the investigated compounds, five compounds demonstrate better activity compared to the standard. In order to investigate the binding interactions of the evaluated compounds with amylase protein, molecular docking studies were conducted, which show an excellent docking score as compared to the standard. Furthermore, the physiochemical properties, drug likeness, and ADMET were investigated, and it was found that none of the compounds violate Lipiniski’s rule of five, which shows that this class of compounds has enough potential to be used as a drug candidate in the near future.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), which represents one of the metabolic disorders, is typically known as hyperglycemia or irregular blood glucose level1 and is caused either by defects in insulin secretion or by its abnormal functions because insulin is a peptide-based hormone, secreted via the islets of Langerhans, responsible for the control of glucose in the blood.2 According to a WHO estimation, in 2019, almost 463 million people suffered from diabetes mellitus, and it is expected to exceed 700 million by 2045.3 Furthermore, it has been found that a weak treatment regimen causes a diverse range of complications,4 including neuropathy, atherosclerosis,5 heart-related ailments, and nephropathy.6

In the current situation, enzymes are prime important biological targets for therapeutic interventions due to their regulating role in gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis pathways.7 Among several enzymes, α-amylase represents an important enzyme responsible for carbohydrate digestion and is also efficiently involved in the hydrolysis of α-(1,4)-glycosidic linkages in starch.8 Therefore, α-amylase is considered one of the best biological targets for the development of type II diabetes therapeutic agents.9

In the current situation, acarbose, voglibose, and miglitol are in clinical use as α-amylase inhibitors, but unfortunately, they are associated with severe gastrointestinal side effects such as abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhea as well as hepatotoxicity.10

In addition to many associated complications with DM, oxidative stress11 causes many fatal diseases such as cancer,12 cardiovascular disease,13 hypertension, inflammation, kidney and liver disorders, and even aging.14 Oxidative stress in the human body is the result of excessive production of oxygen and nitrogen reactive species as well as different free radicals.15 These species may be produced by normal metabolic activities either internally or by external factors like smoking, environmental pollutants, radiations, etc. Furthermore, free radicals capture electrons from different biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, and DNA, which consequently assign abnormal behaviors to these molecules by triggering chain reactions in the body.16

Due to hyperglycemia, different types of enzymes such as lipoxygenase, oxidase, xanthine, etc., affect the generation of reactive organic species (ROS).17 Consequently, oxidative stress and ROS in high levels are fatal to cellular life, which leads to tissue collapse in diabetes.18 Hence, diabetes complications can be controlled by a careful control of free radicals as well as by organic reactive species (ROS) generation.19 Given the current situation, medicinal chemists are looking for novel drug candidates to act as better antioxidants as well as to safely treat DM patients.20

Dihydroyrazole is an important heterocyclic scaffold in medicinal chemistry21 and has received remarkable attention due to its diverse range of medicinal and pharmacological potentials22 such as antimalarial,23 antimicrobial,24 anticancer,25 antiviral,26 antioxidant,27 antidepressant,28 antidiabetic,29 antimycobacterial,30 anti-HIV,31 and anticonvulsant.32

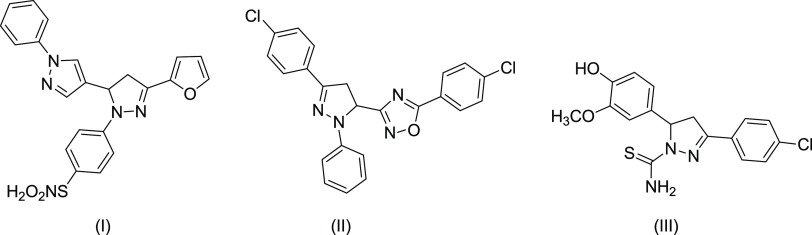

Furthermore, it has been found that dihydropyrazole compounds demonstrate remarkable inhibitory activities against the cancer cell line,33 heptosyltransferase,34 and accumulation of the prion protein.35 In addition, it has been found that compounds such as I,36 II,37 and III,38 as shown in Figure 1, demonstrate excellent antioxidant activities.39

Figure 1.

Representative dihydropyrazole compounds I, II, and III.

It is believed that the N–N bond linkage in dihydropyrazole compounds might be the key factor in their remarkable biological activities.40 It is very hard to construct this type of bond using natural sources, which keep their natural availability very low.41

All of these biological potentials of dihydropyrazole compounds have prompted us to synthesize various analogues of the said nucleus and further explore their antioxidant activity and α-amylase inhibition. Interestingly, the results show that all of the synthesized dihydropyrazole compounds are capable of acting efficiently in scavenging free radicals as well as lowering hyperglycemia and might act as lead compounds in future endeavors of drug development.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

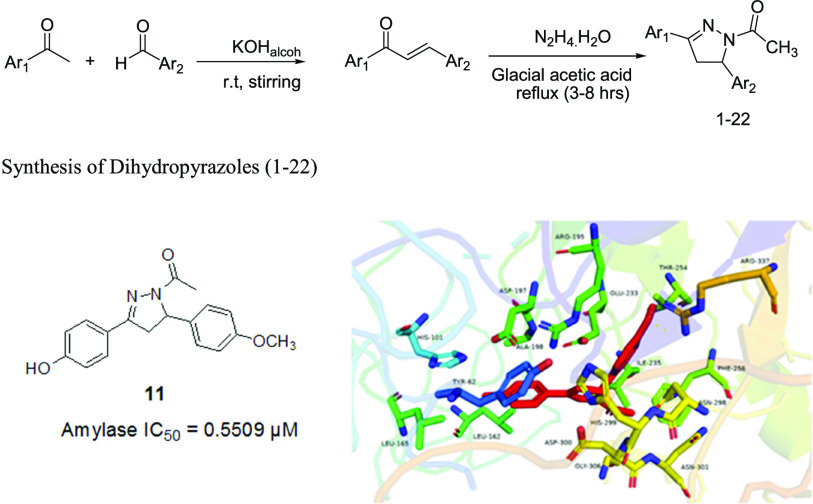

In order to explore the potential of dihydropyrazole compounds as antioxidant and amylase agents, we undertook an efficient protocol to synthesize various analogues of dihydropyrazole compounds (1–22) from already synthesized chalcones42 as shown in Scheme 1. A typical reaction was carried out by treating chalcones in glacial acetic acid with hydrazine hydrate. Then, the reactants were refluxed for 3–8 h, and the progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After completion, it was cooled and left for 24 h. Then, the product was separated, washed with water, and air-dried. The target compounds were purified by recrystallization in absolute ethanol.

Scheme 1. General Scheme for the Preparation of Dihydropyrazole Derivatives from Chalcones.

After purification, the end products were characterized by various spectroscopic techniques and microanalysis. The infrared (IR) spectra of dihydropyrazoles show absorption bands around 3400 cm–1 (N–H), 3250–3300 cm–1 (O–H), 1650–1670 cm–1 (C–O), and 1550–1570 cm–1 (C–N). Similarly, the characteristic peaks and splitting pattern such as double of doublet (dd) due to CH2 at C-4 appear in the ranges of 4.30–3.90 and 3.80–3.02 ppm, as well as CH at C-5 appear in the range of 5.85–4.24 ppm, confirming the formation of dihydropyrazole compounds. Likewise, the N-acetyl methyl group of the said series shows a singlet in the range of 2.54–2.23 ppm. All of these data collectively confirm the dihydropyrazole compounds of the said series. Furthermore, it has been confirmed from 1H NMR data that the methoxy and methyl groups attached to the benzene ring give peaks at 3.80–3.82 and 2.50–2.36 ppm, respectively. Similarly, the hydroxyl group attached to the benzene ring at various positions gives a singlet peak in the range of 10.31–9.70 ppm. In addition, the aromatic ring such as benzene, furan as well as pyridine gives peaks in the aromatic region of 6.00–8.00 ppm. All of these spectroscopic data were found to be in good agreement with reported data.43

In Vitro α-Amylase Activity and Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR)

All of the synthesized dihydropyrazoles were screened for in vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity. Resultantly, the screened compounds demonstrate excellent to good activity in the range of (IC50 = 810.73–0.5509 μM) as compared to the standard acarbose (IC50 = 73.12 μM) as shown in Table 1. Among the evaluated compounds, 5 (35.50 μM), 8 (1.07 μM), and 11 (0.5509 μM) demonstrate excellent activity as compared to the standard acarbose (IC50 = 73.12 μM). The promising activity of the above-mentioned compounds, such as 5, might be due to the p-methylphenyl group at Ar2, while in compound 8, the p-hydroxyphenyl group at Ar1 and the furyl group at Ar2 might cause enhancement in activity. In the same manner, in compound 11, the p-hydroxyphenyl group at Ar1 and the p-methoxyphenyl group at Ar2 might cause high activity. Similarly, it was observed that compounds 3 (603.90 μM) and 9 (631.68 μM) demonstrate low activity as compared to the standard, and it was observed that the low activity might be due to the phenyl group at the Ar1 position and the m-nitrophenyl group at Ar2 in compound 3 and the p-hydroxyphenyl group at Ar1 and the m-nitrophenyl group at the Ar2 position in compound 9, respectively.

Table 1. Synthetic Dihydropyrazole Derivatives from Chalcones.

| s.no | Ar1 | Ar2 | amylase activity (IC50 value in μM) | DPPH (IC50 value in μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C6H5– | o-OH–C6H5– | 188.32 | 84.19 |

| 2 | C6H5– | 2-furyl- | 301.01 | 85.06 |

| 3 | C6H5– | m-NO2–C6H5- | 603.90 | 204.61 |

| 4 | C6H5– | 2-pyridyl- | 663.32 | 913.58 |

| 5 | C6H5– | p-Me–C6H5– | 35.50 | 30.03 |

| 6 | p-MeO–C6H5– | 2-furyl- | 810.73 | 554.32 |

| 7 | p-HO–C6H5– | 2-pyridyl- | 195.65 | 68.99 |

| 8 | p-HO–C6H5– | 2-furyl- | 1.07 | 106.14 |

| 9 | p-HO–C6H5– | m-NO2–C6H5– | 631.68 | 161.13 |

| 10 | p-HO–C6H5– | p-(CH3)2N–C6H5– | 388.07 | 41.09 |

| 11 | p-HO–C6H5– | p- MeO–C6H5– | 0.5509 | 53.49 |

| 12 | p-HO–C6H5– | p- Me–C6H5– | 399.52 | 151.48 |

| 13 | p-Cl–C6H5– | p- MeO–C6H5– | 200.70 | 130.63 |

| 14 | p-Cl–C6H5– | p- Me–C6H5– | 99.58 | 179.22 |

| 15 | p-Cl–C6H5– | C4H3S– | 424.88 | 382.88 |

| 16 | p-Cl–C6H5– | m-OCH3, o-HO–C6H3– | 62.53 | 56.32 |

| 17 | p-Cl–C6H5– | m-HO, C6H4– | 314.88 | 159.51 |

| 18 | p-Cl–C6H5– | 2-pyridyl- | 281.13 | 199.23 |

| 19 | p-Cl–C6H5– | C6H5– | 270.94 | 172.30 |

| 20 | p-Cl–C6H5– | o-OH–C6H5- | 589.63 | 99.59 |

| 21 | p-Cl–C6H5– | 2-furyl- | 262.01 | 580.13 |

| 22 | p-Cl–C6H5– | m-NO2–C6H5– | 61.50 | 220.47 |

| SD*a | acarbose | --- | 73.12 | |

| SD*a | ascorbic acid | --- | 287.30 |

SD* = Standard.

At the end, we can conclude that in the evaluated dihydropyrazoles having electron-withdrawing groups such as nitro and halogen might cause a decrease in activities, while electron-donating groups like methyl, methoxy, and hydroxyl might cause an increase in activity. In order to find the binding mode of the highly active compounds, their molecular docking study was conducted with the α amylase enzyme.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activities and Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies

All of the evaluated compounds demonstrate good to excellent antioxidant activity. Among the 22 evaluated compounds, 11 compounds demonstrate excellent activity as compared to the standard ascorbic acid; among them, the most active compound is 5 (IC50 = 30.03 μM), having the phenyl group at Ar1 and the p-methylphenyl group at Ar2 positions, while the second most active compound is 10 (IC50 = 41.09 μM), which has the p-hydroxyphenyl group at Ar1 and the p-dimethylaminophenyl group at Ar2 positions as shown in Table 1. Similarly, compound 11 (IC50 = 53.49 μM) has the p-hydroxyphenyl group at Ar1 and the p-methoxyphenyl group at Ar2 positions. Interestingly, the remaining highly active compounds such as 1 (IC50 = 84.19 μM), 7 (IC50 = 68.99 μM), 8 (IC50 = 106.14 μM), 10 (IC50 = 41.09 μM), 12 (IC50 = 151.48 μM), 16 (IC50 = 56.32 μM), and 20 (IC50 = 99.59 μM) have the hydroxyphenyl group at either the Ar1 or Ar2 position along with other substituents like p-methylphenyl and p-methoxyphenyl as shown in Table 1. The high activity of the above-mentioned compounds might be due to the positive inductive effect of the hydroxyl, methyl, and methoxy groups.

Molecular Docking Studies

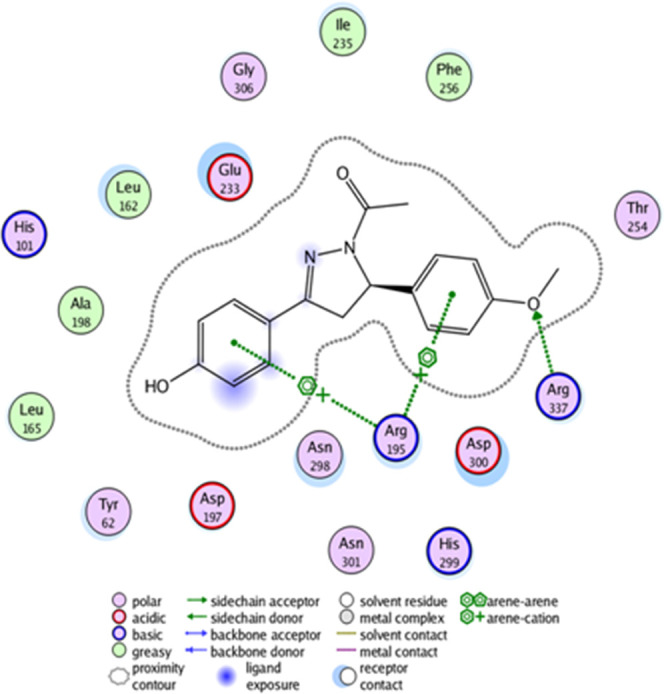

The molecular docking study was carried out with the aim to investigate all of the possible binding interactions of the synthesized compounds into α-amylase active-site residues. The molecular docking investigation revealed that the synthesized compounds are oriented in a way to establish suitable interactions with the active site of the target α amylase enzyme. Interestingly, among the evaluated compounds, the most active compound is 11, which shows the highest IC50 of 0.5509 μM, and it is evident from the molecular docking study that 11 also shows the highest docking score (−13.5028 kcal/mol) and is deeply involved in 18 types of binding interactions with the active site of the α-amylase enzyme such as one hydrogen bond with Arg 337, two arene cation interactions with Arg 195, and 15 other interactions with residues such as Thr 254, Phe 256, Ile 235, Gly 306, Glu 233, Leu 162, His 101, Ala 198, Leu 165, Tyr 62, Asp 197, Asn 298, Asn 301, His 299, and Asp 300 as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

2D images of the docked compound 11 in the active site of the α-amylase enzyme.

In general, the whole series of dihydropyrazole analogues demonstrate good to excellent activity against the α-amylase enzyme. Various types of functional groups such as halides, alkyl, nitro, and alkoxy groups attached at various positions of the Ar1 and Ar2 rings of the dihydropyrazole compounds might be responsible for their excellent inhibitory activity against the α-amylase enzyme.

Drug Likeness and ADMET Studies

We have evaluated the drug-likeness properties of the synthesized compounds with different rules such as the Lipinski rule and Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge filters. According to Lipinski’s rule of 5, the compound should have a molecular weight ≤500, MLOGP ≤4.15, H-bond acceptor ≤10, and H-bond donor ≤5. All of the selected compounds follow Lipinski RO5, whereas the control shows three violations as shown in Table 2. Similarly, the evaluated compounds follow all types of filters and show no violation, whereas the control (acarbose) shows violations to each filter as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Drug-Likeness Properties of the Selected Dihydropyrazole Derivatives.

| drug-likeness violations |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s.no | TPSA (Å)* | Lipinski violations | Ghose violations | Veber violations | Muegge violations | Egan violations | bioavailability score | consensus log P | SA |

| 5 | 32.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 3.19 | 3.28 |

| 8 | 66.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 1.79 | 3.41 |

| 11 | 62.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 2.44 | 3.28 |

| 14 | 32.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 3.73 | 3.30 |

| 16 | 62.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 3.03 | 3.35 |

| control acarbose | 334.24 | 03 | 04 | 01 | 05 | 01 | 0.11 | –7.07 | 7.25 |

The topological polar surface area (TPSA) values for the evaluated compounds were found to be in the range of 32.67–66.06 (below 140 A2) as shown in Table 2, confirming that the compounds have considerable intestinal absorption of the compounds. It has been found that compounds with a TPSA of 140 A2 and above would be poorly absorbed, while compounds with a TPSA of 60 A2 would be very well absorbed (>90%). Furthermore, based on the TPSA score, the percentage of absorption can be determined as follows: (%ABS) = 109-(0.345 *TPSA). Resultantly, based on TPSA values, the %ABS lies in the range of 97.72–86.21, which show that all of the selected compounds show %ABS values more than 85%, evidencing that the evaluated compounds demonstrate excellent cellular plasmatic membrane permeability. Furthermore, a bioavailability score of 0.55 was found for all of the compounds, which confirms that all of the evaluated compounds can reach the circulation system very easily as shown in Table 2.

Similarly, lipophilicity is the measurement of the solubility of a drug in lipids or nonpolar solvents, which has a huge effect on the overall ADMET property of the drug.44,45 It plays a major role in the absorption of drugs across cell membranes.46 According to most filters (rule of 5) for drug-likeness, a lipophilicity range of 0–5 is usually considered optimal for drug design.47 According to our screening, all of the synthesized compounds show lipophilicity in the range of 3.73–1.79, which is considered optimal compared to the standard acarbose (−7.07), as shown in Table 2. Similarly, synthetic accessibility (SA) also plays an important role in the drug selection process; it is primarily based on the hypothesis that the frequency of the molecular fragments available correlates with the facility of synthesis. The SA score ranges from 1 (very easy) to 10 (very difficult). The selected compounds show SA scores in the range of 3.41–3.28, which is very good as compared to the standard acarbose (7.25), as shown in Table 2.

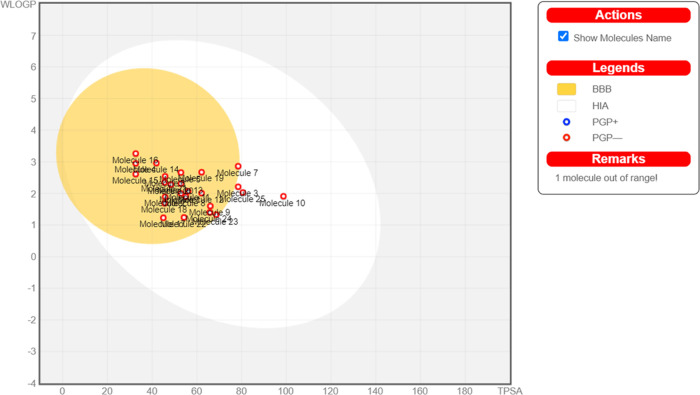

In the same manner, the pharmacokinetics studies show that none of the drug is the substrate of PGP. GI absorption of all drugs was high as compared to the control as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Representation of dihydropyrazole analogues by the Boiled graph.

Furthermore, the investigation of interactions between the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system and compounds is very important to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of candidate drugs as these interactions are very important for the transformation and elimination of drugs from the system.48 Furthermore, drugs that inhibit isoforms of this enzyme system could result in poor elimination, resulting in drug-induced toxicity. It is therefore important that a candidate drug should have limited inhibitory activity against these enzyme isoforms. The current study revealed that among the investigated compounds, compound 8 exhibits no potential to inhibit any of the five P450 isoforms. However, compounds such as 5, 11, and 14 show inhibitory potential against two of the five P450 isoforms as shown in Table 3. This indicates that those compounds that show no potential inhibitory activity as well as minor inhibition would be well-metabolized in the liver and eliminated easily from the organism.

Table 3. Properties of Different Cytochrome Inhibitors of the Selected Dihydropyrazole Derivatives.

| s. no | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | no | yes | yes | no | no |

| 8 | no | no | no | no | no |

| 11 | no | yes | yes | no | no |

| 14 | no | yes | yes | no | no |

| 16 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| control (acarbose) | no | no | no | no | no |

The toxic profiles of the compounds were also predicted using pkCS software, and the results of the selected compounds are shown in Table 4. The website can provide details of toxicology effects in the fields of AMES toxicity, human maximum tolerance dose, hERG-1 inhibitor, Herg-II (human Ether-a-go-go-Related Gene) inhibitor, LD50(Lethal dose), chronic oral rat toxicity, hepatotoxicity, and skin toxicity. Among the evaluated compounds, the selected compounds such as 5, 8, 11, 14, and 16 show no toxicity as shown in Table 4. It shows that these compounds have mutagenic potentials. Similarly, all of the evaluated compounds possess no skin sensitization; however, hepatotoxicity results show that most of the compounds are not toxic except for 5, which possesses toxicity. Furthermore, the selected compounds do not inhibit hERG-I and hERG-II, which is a promising finding that provides a non-cardio-toxic profile to the compounds. In addition, oral rat acute toxicity (LD50) was found in the range of 2.869–2.02, as compared to the standard (3.113). Similarly, oral rat chronic toxicity (LOAEL) was found to be in the range of 2.006–0.658, whereas the standard is 5.196. In the same manner, the max tolerated dose (human) was found in the range of 0.360–0.015, whereas the standard is 0.676 as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Predicted Toxicity of the Selected Dihydropyrazole Derivatives.

| toxicity risks |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s.no | skin sensitization | AMES toxicity | hERG-I inhibitors | hERG-II inhibitors | ORAa toxicity | ORCb toxicity | MTDc | hepatotoxicity |

| 5 | no | no | no | no | 2.02 | 0.759 | 0.184 | yes |

| 8 | no | no | no | no | 2.869 | 1.843 | 0.015 | no |

| 11 | no | no | no | no | 2.383 | 2.006 | 0.360 | no |

| 14 | no | no | no | no | 2.204 | 0.658 | 0.146 | no |

| 16 | no | no | no | no | 2.343 | 1.149 | 0.044 | no |

| control acarbose | no | no | yes | yes | 3.113 | 5.196 | 0.676 | no |

ORA Toxicity = oral acute toxicity.

ORC = oral chronic toxicity.

MTD = Max tolerated dose (human).

The criteria generally assumed for an orally active drug based on the above filters should not violate more than once. On a careful examination of the above data, it can be concluded that all of the synthesized compounds and the standard drug fulfill the above-mentioned criteria.

Conclusions

Dihydropyrazoles (1–22) were synthesized and evaluated for antioxidant activity along with α-amylase inhibition studies. All of the synthesized compounds displayed good antioxidant activity. Among the evaluated compounds, most of the compounds such as 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 20 demonstrate potential antioxidant activity as compared to the standard. Furthermore, among the 22 screened compounds against α amylase, it was found that compounds like 5, 8, 11, 12, 14, and 16 displayed excellent inhibition against α-amylase as compared to the standard acarbose. Based on the structure–activity relationships, it was found that the compounds having electron-donating groups like methyl, methoxy, and amino display potent α-amylase inhibition as well as antioxidant activity, while decreases in activities were found by introducing an electron-withdrawing group like the nitro group. In addition, the possible types of binding interactions were investigated by molecular docking, which was established during interaction of the synthetic compounds within the active site. Furthermore, the drug likenesses of the synthesized compounds were evaluated by the Lipinski rule. All of the synthesized compounds follow Lipinski RO5, whereas the control shows three violations. Similarly, TPSA values for all of the evaluated compounds confirm that the compounds have considerable intestinal absorption. In the same manner, all of the synthesized compounds show good synthetic accessibility scores as compared to the standard. Based on the above interesting results, we are optimistic that this class of compounds has enough potential to act as lead as well as drug candidates in the near future.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

All of the chemicals and reagents used in this research work were of synthetic grade and were purchased from commercial authentic suppliers. The starting materials such as various analogues of chalcones were synthesized by a reported procedure.49 However, hydrazine hydrates and glacial acetic acids were purchased from Alfa Aesar and were used directly without further purification. The progress of the reaction was followed by TLC, which was performed on precoated silica gel aluminum plates (Merck, Germany). The synthesized products were purified by recrystallization from absolute EtOH. The IR was recorded on a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (SHIMADZU, Japan). Furthermore, the 1H NMR spectra of the prepared products were recorded on Bruker 500 and 300 MHz NMR spectrometers (Bruker, Germany) in deuterated DMSO, and elemental analysis was carried out on Carlo Erba 1106.

Pharmacokinetic and Molecular Docking Studies

Physicochemical properties, drug likeness, lipophilicity, medicinal chemistry, and pharmacokinetics of the compounds were determined using the Swiss ADME Web server.48 The percent absorption (%Abs) of the synthesized compounds was calculated using the formula %Abs = 109–(0.345*TPSA).50 Utilizing the pkCSM Web tool, the toxicity profile of the compounds was predicted.51 The molecular docking of compounds with α-amylase was carried out using molecular operating environment (MOE) software (version 2010.12).52 The compounds were drawn in Chem Draw Version 19.0.1.332 (PerkinElmer Informatics, Waltham, MA), and the control acarbose was retrieved from PubChem (PubChem ID: 41774).53 The compounds were imported as mol files in the MOE followed by protonation and energy minimization using MMFF94X forcefield default parameters. Human α-amylase (PDB:1b2y) was retrieved from the RCSB PDB database, and the three-dimensional (3D) structure was refined by removing water molecules, ligands, and cofactor by using PyMOL version 2.5.4.54 The 3D structure of the protein was subject to protonation, and energy minimization was carried out using MMFF94X forcefield default parameters. The compounds were docked into the active site of the protein calculated by the site finder of MOE. Docking was run by setting placement as the triangle matcher and refinement as the forcefield, rescorings 1 and 2 were set as London dG, and retains were set at 30. The images were developed using LigX of MOE.

In Vitro α-Amylase Inhibition Assay protocol

The α-amylase inhibition potential of the tested samples (HP series) was evaluated according to the following protocol already discussed in the previous literature with some modifications.55 First of all, in a 96-well plate, a mixture of 50 μL of phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH = 6.8), 10 μL of α-amylase solution (2 U/mL), 20 μL of samples (dihydropyrazole derivative), and acarbose (standard) of various concentrations (200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5 μM) was preincubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Now, 20 μL of starch solution (1% in phosphate buffer w/v) (100 mM phosphate buffer, pH = 6.8) was added and incubated further at 37 °C for 30 min. Next, 100 μL of DNS (dinitrosalicyclic acid) color reagent was added and boiled for 10 min. After cooling, the absorbance of the resulting mixture was measured at 540 nm using a Biotech Eliza plate reader. The without test substance was set parallel as the control, and all of the experiments were performed in triplicate. Finally, the results were expressed as IC50 by using graph pad prism software.

In Vitro Antioxidant Assay Protocol (DPPH Scavenging Method)

The antioxidant potential of the tested samples was evaluated using the DPPH scavenging free radical activity method according to the following protocol already discussed in the literature with some modifications.56,57 First of all, in a 96-well plate, 100 μL of different concentrations (200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5 μM) of the tested samples dissolved in DMSO was taken. Next, an equal volume of 100 mM DPPH methanolic solution was added to each sample and was incubated protected from light for 30 min at room temperature. Ascorbic acid was used as the standard, and an equal volume of DMSO was added to the control solution. The evaluation was made by calculating their IC50 values from their absorbance at 517 nm using a Biotech Eliza plate reader. The readings were taken in triplicate.

General Protocol for the Synthesis of Dihydropyrazole Derivatives from Chalcones

For preparing various dihydropyrazole derivatives from chalcones, the following reported procedure,43 with little modification, was followed. First, a chalcone (1 mmol) was dissolved in glacial acetic acid (10–20 mL), and hydrazine hydrate (1–2.25 mmol) was added to it. Then, the reactants were heated on stirring for 3–8 h; the reaction progress was confirmed by TLC. After completion of the reaction, it was cooled and left for 24 h. Then, the residue was collected, and the product was separated, washed with water, and then air-dried. The target compound was made pure by recrystallization in absolute EtOH.

Spectra Data of Dihydropyrazole Derivatives (1–22)

1-(5-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)-3-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (1)

Color: Light-brown color solid; yield: 68%; Rf: 0.45 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1:4); chemical formula: C17H16N2O2; molecular weight: 280.32; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3050 (C–H, aromatic), 2920 (C–H, aliphatic), 1650 (C=O, amide), 1620 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.70 (s, 1H, −OH), 7.85–7.45 (m, 4H), 6.94–6.64 (m, 5H), 7.49–7.47 (m, 2H), 5.63 (dd, J = 4.70, 4.71 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (dd, J = 11.80, 11.85 Hz, 1H), 3.02 (dd, J = 5.15, 5.20 Hz, 1H), 2.33(s, 3H); anal. calcd for C17H16N2O2: C, 72.84; H, 5.75; N, 9.99; found: C, 72.98; H, 5.72; N, 9.96.

1-(5-(Furan-2-yl)-3-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (2)

Color: Dark-black color crystalline solid; yield: 72%; Rf: 0.48 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1:4); chemical formula: C15H14N2O2; molecular weight: 254.28; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3040 (C–H, aromatic), 2925 (C–H, aliphatic), 1640 (C=O, amide), 1630 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.82–7.54 (m, 5H), 6.39–6.32 (m, 2H), 6.66–6.63 (m, 1H), 5.65 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.05 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (dd, J = 5.25, 5.25 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C15H14N2O2: C, 70.85; H, 5.55; N, 11.02; found: C, 70.83; H, 5.53; N, 11.01.

1-(5-(3-Nitrophenyl)-3-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 60%; Rf: 0.43 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C17H15N3O3; molecular weight: 309.32; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3055 (C–H, aromatic), 2920 (C–H, aliphatic), 1650 (C=O, amide), 1620 (C=N), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.81 (d, J = 7.79, 1H), 7.65 (t, J = 7.79, 1H), 7.49–7.47 (m, 2H), 5.73 (dd, J = 5.1, 5.05 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (dd, J = 12.05, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (dd, J = 5.15, 5.15 Hz, 1H), 2.33 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C17H15N3O3: C, 66.01; H, 4.89; N, 13.58; found: C, 66.50; H, 4.87; N, 13.55.

1-(3-Phenyl-5-(pyridin-2-yl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (4)

Color: Cream-colored crystalline solid; yield: 62%; Rf: 0.42 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C16H15N3O; molecular weight: 265.31; FTIR: (KBr, cm–1): 3038 (C–H, aromatic), 2948 (C–H, aliphatic), 1622 (C=O, amide), 1637 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.44 (m, 2H), 7.79 (m, 2H), 7.42 (m, 2H), 7.27 (m, 3H), 4.24 (dd, J = 4.60, 4.60 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.54 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C16H15N3O: C, 72.43; H, 5.70; N, 15.84; found: 72.41; H, 5.67; N, 15.81.

1-(3-Phenyl-5-(p-tolyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (5)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid: yield: 80%; Rf: 0.50 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4): chemical formula: C18H18N2O; molecular weight: 278.35; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3052 (C–H, aromatic), 2958 (C–H, aliphatic), 1628 (C=O, amide), 1630 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.17 (s, 1H, −OH), 7.79 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 7.34–7.180 (m, 5H), 5.54 (dd, J = 5.01, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.12 (dd, J = 4.65, 4.60 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (s, 3H, −CH3), 2.31 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C18H18N2O: C, 77.67; H, 6.52; N, 10.06; found: C, 77.64; H, 6.50; N, 10.04.

1-(5-(Furan-2-yl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (6)

Color: Light-brown crystalline solid; yield: 76%, Rf: 0.47 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C16H16N2O3; molecular weight: 284.31; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3050 (C–H, aromatic), 2945 (C–H, aliphatic), 1635 (C=O, amide), 1612 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 8.07 (d, J = 8.9, 2H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.9, 2H), 6.59 (m, 1H), 6.41–6.38 (m, 1H), 5.60 (dd, J = 4.50, 4.55 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.76 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (dd, J = 5.02, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C16H16N2O3: C, 67.59; H, 5.67; N, 9.85; found: C, 67.56; H, 5.64; N, 9.83.

1-(3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-5-(pyridin-2-yl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (7)

Color: Gray-color solid; yield: 65%: Rf: 0.40 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C16H15N3O2: molecular weight: 281.31; FTIR: (KBr, cm–1): 3046 (C–H, aromatic), 2930 (C–H, aliphatic), 1622 (C=O, amide), 1620 (C=N), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), 9.97 (s, −OH), 8.49 (m, 2H), 7.76 (m, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 7.32 (m, 1H), 7.27 (m, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 5.52 (dd, J = 5.01, 5.02 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (dd, J = 12.01, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.25 (dd, J = 4.60, 4.60 Hz, 1H), 2.25 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C16H15N3O2: C, 68.31; H, 5.37; N, 14.94; found: C, 68.28; H, 5.34; N, 14.90.

1-(5-(Furan-2-yl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (8)

Color: Dark-brown crystalline solid; yield: 80%, Rf: 0.48 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C15H14N2O3; molecular weight: 270.28; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3040 (C–H, aromatic), 2945 (C–H, aliphatic), 1655 (C=O, amide), 1632 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 9.99 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 7.54 (m, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 6.38 (m, 1H), 6.28 (m, 1H), 5.57 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (dd, J = 4.80, 4.80 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C15H14N2O3: C, 66.66; H, 5.22; N, 10.36; found: C, 66.62; H, 5.19; N, 10.32.

1-(3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-5-(3-nitrophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (9)

Color: Off-white crystalline solid; yield: 60%, Rf: 0.45 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C17H15N3O4; molecular weight: 325.32, FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3046 (C–H, aromatic), 2935 (C–H, aliphatic),1645 (C=O, amide), 1622 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 10.01 (s, 1H, −OH), 8.13 (m, 1H), 8.04 (s, 1H),7.64 (m, 4H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 3.85 (dd, J = 4.80, 4.80, 3.19 (dd, 5.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H)), 2.30 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C17H15N3O4: C, 62.76; H, 4.65; N, 12.92; found: C, 62.73; H, 4.62; N, 12.89.

1-(5-(4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydropyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (10)

Color: Off-white crystalline solid; yield: 70%; Rf: 0.45 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C19H21N3O2; molecular weight: 323.39; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3046 (C–H, aromatic), 2935 (C–H, aliphatic), 1645 (C=O, amide), 1622 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 10.01 (s, 1H, −OH), 7.62 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.60, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 6.38 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 5.57 (dd, J = 5.02, 5.01 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (dd, 1H, J = 11.90, 11.90 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.00 (s, 6H), 2.23 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C19H21N3O2: C, 70.57; H, 6.55; N, 12.99; found: C, 70.54; H, 6.53; N, 12.95.

1-(3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (11)

Color: Light-brown crystalline solid; yield: 67%; Rf: 0.40 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C18H18N2O3; molecular weight: 310.35; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3036 (C–H, aromatic), 2932 (C–H, aliphatic), 1640 (C=O, amide), 1632 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.98 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.60, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.65, 1H), 5.43 (dd, J = 4.1, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (dd, J = 11.50, 11.50 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (dd, J = 4.25, 4.20 Hz, 1H), 2.25 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C18H18N2O3: C, 69.66; H, 5.85; N, 9.03; found: C, 69.63; H, 5.82; N, 9.00.

1-(3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-5-(p-tolyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (12)

Color: Cream-color crystalline solid; yield: 70%; Rf: 0.40 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C18H18N2O2; molecular weight: 294.35; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3046 (C–H, aromatic), 2942 (C–H, aliphatic), 1634 (C=O, amide), 1642 (C=N), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.98 (s, 1H, −OH), 7.61 (d, J = 8.45, 2H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.05, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.20, 1H), 5.44 (dd, J = 4.15, 4.25 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (dd, J = 11.75, 11.65 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 3.04 (dd, J = 4.25, 4.20 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C18H18N2O2: C, 73.45; H, 6.16; N, 9.52; found: C, 73.43; H, 6.12; N, 9.50.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (13)

Color: Cream-color crystalline solid; yield: 70%; Rf: 0.44 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C18H17ClN2O2; molecular weight: 328.10; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3032 (C–H, aromatic), 2932 (C–H, aliphatic), 1640 (C=O, amide), 1632 (C=N), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.5, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.50, 1H), 5.49 (dd, J = 4.55, 4.55 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (dd, J = 11.90, 11.85 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H, −OCH3), 3.11 (dd, J = 4.65, 4.60 Hz, 1H), 2.52 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C18H17ClN2O2: C, 65.75; H, 5.21; N, 8.52; found: C, 65.72; H, 5.19; N, 8.50.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(p-tolyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (14)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 72%; Rf: 0.40 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C18H17ClN2O; molecular weight: 312.79; FTIR: (KBr, cm–1): 3032 (C–H, aromatic), 2958 (C–H, aliphatic), 1648 (C=O, amide), 1640 (C=N), 1H NMR: (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 8.17 (d, J = 8.55, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.55, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 5.51 (dd, J = 4.90, 4.90 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (dd, J = 11.90, 11.90 Hz, 1H), 3.12 (dd, J = 5.02, 5.01 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H, −CH3), 2.26 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C18H17ClN2O: C, 69.12; H, 5.48; N, 8.96; found: C, 69.10; H, 5.45; N, 8.94.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (15)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 67%; Rf: 0.42 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C15H13ClN2OS; molecular weight: 304.79; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3066 (C–H, aromatic), 2940 (C–H, aliphatic), 1642 (C=O, amide), 1628 (C=N), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.82 (d, J = 8.65, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.65, 2H), 7.40 (d, J = 6.15, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 6.15, 1H), 6.94 (m, 1H), 5.85 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (dd, J = 11.70, 11.70 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (dd, J = 4.80, 4.80 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C15H13ClN2OS: C, 59.11; H, 4.30; N, 9.19; found: C, 59.09; H, 4.28; N, 9.16.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydropyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (16)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 64%; Rf: 0.50 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane 1:4); chemical formula: C18H17ClN2O3; molecular weight: 344.79; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3028 (C–H, aromatic), 2938 (C–H, aliphatic), 1612 (C=O, amide), 1627 (C=N), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), 8.99 (s, 1H, −OH), 7.79 (d, J = 8.55, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.55, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.85, 2H), 6.57 (d, J = 8.85, 1H), 6.57 (s, 2H, aromatic-H), 5.40 (dd, J = 4.70, 4.70 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.01 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H, −OCH3), 3.11 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.01 Hz, 1H), 2.28 (s, 3H, −CH3); anal. calcd for C18H17ClN2O3: C, 62.70; H, 4.97; N, 8.12; found: C, 62.67; H, 4.95; N, 8.10.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydropyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (17)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 63%; Rf: 0.50 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C17H15ClN2O2; molecular weight: 314.77; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3018 (C–H, aromatic), 2928 (C–H, aliphatic), 1622 (C=O, amide), 1617 (C=N); 1H NMR: (500 MHZ, DMSO-d6), 9.68 (s, 1H, −OH), 9.39 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.60, 2H), 7.11 (m, 1H), 6.61 (m, 1H), 6.55 (m, 1H), 5.45 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.01 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (dd, J = 12.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.12 (dd, J = 4.85, 4.85 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H, −CH3); anal. calcd for C17H15ClN2O2: C, 64.87; H, 4.80; N, 8.90; found: C, 64.84; H, 4.77; N, 8.86.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(pyridin-2-yl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (18)

Color: Off-white crystalline solid; yield: 67%; Rf: 0.50 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C16H14ClN3O; molecular weight: 299.75; 1H NMR: (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 8.40 (d, J = 8.45, 2H), 7.81–7.71(m, 2H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.45, 2H), 7.29–7.26 (m, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.20, 1H), 4.25 (dd, J = 5.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (dd, J = 11.0, 11.0 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (dd, J = 4.70, 4.70 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (s, 3H, −COCH3); anal. calcd for C16H14ClN3O: C, 64.11; H, 4.71; N, 14.02; found: C, 64.08; H, 4.68; N, 14.00

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (19)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 70%; Rf: 0.50 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C17H15ClN2O; molecular weight: 298.77; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3040 (C–H, aromatic), 2925 (C–H, aliphatic), 1640 (C=O, amide), 1628 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.80 (d, J = 8.5, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.5, 1H), 7.35–7.18 (m, 5H), 5.54 (dd, J = 4.60, 4.65 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (dd, J = 11.95, 11.90, 1H), 3.16 (dd, J = 4.7, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.31 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C17H15ClN2O:C, 68.34; H, 5.06; N, 9.38; found: C, 68.32; H, 5.03; N, 9.35.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (20)

Color: Yellow crystalline solid; yield: 75%; Rf: 0.42 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C17H15ClN2O2; molecular weight: 314.77; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3030 (C–H, aromatic), 2935 (C–H, aliphatic), 1645 (C=O, amide), 1624 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6,): δ 10.31 (s, 1H, −OH), 7.77 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.6, 1H), 6.83–6.63 (m, 5H), 5.63 (dd, J = 4.45, 4.50 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (dd, J = 11.90, 11.80 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (dd, J = 4.60, 4.60 Hz, 1H), 2.32 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C17H15ClN2O2: C, 64.87; H, 4.80; N, 8.90; found: C, 64.85; H, 4.78; N, 8.88.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(furan-2-yl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (21)

Color: Dark-brown crystalline solid; yield: 70%; Rf: 0.48 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C15H13ClN2O2; molecular weight: 288.73; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3060 (C–H, aromatic), 2945 (C–H, aliphatic), 1645 (C=O, amide), 1622 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.09 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.0, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.0, 2H), 6.71 (m, 1H), 5.65 (dd, J = 5.20, 5.15 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (dd, J = 12.1, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (dd, J = 5.25, 5.40 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C15H13ClN2O2: C, 62.40; H, 4.54; N, 9.70; found: C, 62.38; H, 4.52; N, 9.69.

1-(3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-(3-nitrophenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (22)

Color: Light-yellow crystalline solid; yield: 75%; Rf: 0.45 (ethyl acetate/n-hexane, 1:4); chemical formula: C17H14ClN3O3; molecular weight: 343.76; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3060 (C–H, aromatic), 2945 (C–H, aliphatic), 1645 (C=O, amide), 1622 (C=N); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.07 (s, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.6, 2H), 7.68–6.64 (m, 4H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.6, 1H), 5.72 (dd, J = 5.2, 5.15 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (dd, J = 12.1, 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.27 (dd, J = 5.25, 5.20 Hz, 1H), 2.33 (s, 3H); anal. calcd for C17H14ClN3O3: C, 59.40; H, 4.10; N, 12.22; found: C, 59.39; H, 4.08; N, 12.20.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Higher Education Commission Pakistan under NRPU Project No-17234/-

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c00529.

Drug-likeness properties of the synthesized compounds (Tables S1, S2, and S3); basic physiochemical properties and computational descriptors of the synthesized compounds (Tables S4 and S6); properties of different cytochrome inhibitors of the synthesized compounds (Table S5); docking score and binding interaction details of the synthesized compounds (Table S7); representation of pyrazole analogues by the boiled graph (Figure S1); 2D docking images of compounds 1–14, 16, 18–22, and the control (acarbose) (Figures S2–S22); radar images of compounds 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 22, and the control (acarbose) (Figures S23–S29); and 1H NMR spectra of compounds 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 19 (Figures S30–S40) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Akande A. A.; Salar U.; Khan K. M.; Syed S.; Aboaba S. A.; Chigurupati S.; Wadood A.; Riaz M.; Taha M.; Bhatia S. Substituted Benzimidazole Analogues as Potential α-Amylase Inhibitors and Radical Scavengers. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 22726–22739. 10.1021/acsomega.1c03056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal; Khan K. M.; Chigurupati S.; Ali F.; Younus M.; Aldubayan M.; Wadood A.; Khan H.; Taha M.; Perveen S. Indole-3-acetamides: As Potential Antihyperglycemic and Antioxidant Agents; Synthesis, In Vitro α-Amylase Inhibitory Activity, Structure–Activity Relationship, and In Silico Studies. ACS omega 2021, 6, 2264–2275. 10.1021/acsomega.0c05581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur N.; Kumar V.; Nayak S. K.; Wadhwa P.; Kaur P.; Sahu S. K. Alpha-amylase as molecular target for treatment of diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 539–560. 10.1111/cbdd.13909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz M.; Taha M.; Qureshi F.; Ullah N.; Selvaraj M.; Shahzad S.; Chigurupati S.; Waheed A.; Almutairi F. A. Structural elucidation, molecular docking, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition studies of 5-amino-nicotinic acid derivatives. BMC Chem. 2020, 14, 43 10.1186/s13065-020-00695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran A.; Shehzad M. T.; Shah S. J. A.; Laws M.; Al-Adhami T.; Rahman K. M.; Khan I. A.; Shafiq Z.; Iqbal J. Development, Molecular Docking, and In Silico ADME Evaluation of Selective ALR2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Diabetic Complications via Suppression of the Polyol Pathway. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 26425–26436. 10.1021/acsomega.2c02326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeghate E.; Schattner P.; Dunn E. An update on the etiology and epidemiology of diabetes mellitus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1084, 1–29. 10.1196/annals.1372.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piero M.Hypoglycemic Effects of some Kenyan Plants Traditionally Used in Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Eastern Province. MSc Thesis; Kenyatta University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Samrot A.; Vijay A. A-Amylase activity of wild and mutant strains of Bacillus sp. Internet J. Microbiol. 2008, 6 (2), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Qin X.; Ren L.; Yang X.; Bai F.; Wang L.; Geng P.; Bai G.; Shen Y. Structures of human pancreatic α-amylase in complex with acarviostatins: Implications for drug design against type II diabetes. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 174, 196–202. 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Laar F. A.; Lucassen P. L.; Akkermans R. P.; Van De Lisdonk E. H.; Rutten G. E.; Van Weel C. α-Glucosidase inhibitors for patients with type 2 diabetes: results from a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 154–163. 10.2337/diacare.28.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo V.; Patil A.; Phatak A.; Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M.; Izakovic M.; Mazur M.; Rhodes C. J.; Telser J. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 266, 37–56. 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000049134.69131.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Peng T.; Zhu H.; Zheng X.; Zhang X.; Jiang N.; Cheng X.; Lai X.; Shunnar A.; Singh M.; Riordan N.; Bogin V.; Tong N.; Min W.-P. Prevention of hyperglycemia-induced myocardial apoptosis by gene silencing of Toll-like receptor-4. J. Transl. Med. 2010, 8, 133 10.1186/1479-5876-8-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü J. M.; Lin P. H.; Yao Q.; Chen C. Chemical and molecular mechanisms of antioxidants: experimental approaches and model systems. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 840–860. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuelizz H. A.; Taie H. A.; Bakheit A. H.; Mostafa G. A.; Marzouk M.; Rashid H.; Al-Salahi R. Investigation of 4-Hydrazinobenzoic Acid Derivatives for Their Antioxidant Activity: In Vitro Screening and DFT Study. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 31993–32004. 10.1021/acsomega.1c04772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M. The evolution of free radicals and oxidative stress. Am. J. Med. 2000, 108, 652–659. 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W.; Chen M.; Zheng D.; He J.; Song M.; Mo L.; Feng J.; Lan J. A novel damage mechanism: Contribution of the interaction between necroptosis and ROS to high glucose-induced injury and inflammation in H9c2 cardiac cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 201–208. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmak A.; Niknam K.; Mohebbi G. Synthesis, Structural Studies, and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory, Antidiabetic, and Antioxidant Activities of 2, 3-Dihydroquinazolin-4 (1 H)-ones Derived from Pyrazol-4-carbaldehyde and Anilines. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 18087–18099. 10.1021/acsomega.9b01906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj S.; Khan A. Antioxidants and diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 267 10.4103/2230-8210.104057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumara K.; Prabhudeva M. G.; Vagish C. B.; Vivek H. K.; Rai K. M. L.; Lokanath N. K.; Kumar K. A. Design, synthesis, characterization, and antioxidant activity studies of novel thienyl-pyrazoles. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07592 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethiraj K. R.; Nithya P.; Krishnakumar V.; Mathew A. J.; Khan F. N. Synthesis and cytotoxicity study of pyrazoline derivatives of methoxy substituted naphthyl chalcones. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 1833–1841. 10.1007/s11164-012-0718-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakarthikeyan R.; Iniyaval S.; Saravanan V.; Lim W.-M.; Mai C.-W.; Ramalingan C. Molecular hybrids integrated with benzimidazole and pyrazole structural motifs: design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10089–10098. 10.1021/acsomega.0c00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kumar S.; Bawa S.; Drabu S.; Kumar R.; Gupta H. Biological Activities of Pyrazoline Derivatives -A Recent Development. Recent Pat. Anti-Infect. Drug Discovery 2009, 4, 154–163. 10.2174/157489109789318569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Acharya B. N.; Saraswat D.; Tiwari M.; Shrivastava A. K.; Ghorpade R.; Bapna S.; Kaushik M. P. Synthesis and antimalarial evaluation of 1, 3, 5-trisubstituted pyrazolines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 430–438. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan M. S.; Holla B. S.; Kumari N. S. Synthesis and antimicrobial studies on novel chloro-fluorine containing hydroxy pyrazolines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 30–36. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar E. Synthesis,(in vitro) antitumor and antimicrobial activity of some pyrazoline, pyridine, and pyrimidine derivatives linked to indole moiety. J. Am. Sci 2010, 6, 463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Ramajayam R.; Tan K.-P.; Liu H.-G.; Liang P.-H. Synthesis and evaluation of pyrazolone compounds as SARS-coronavirus 3C-like protease inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 7849–7854. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveen S.; Kumara K.; Kumar A. D.; Kumar K. A.; Zarrouk A.; Warad I.; Lokanath N. K. Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis, antioxidant properties and DFT calculations of a novel pyrazole derivative: ethyl 1-(2, 4-dimethylphenyl)-3-methyl-5-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylate. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1226, 129350 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad Y. R.; Rao A. L.; Prasoona L.; Murali K.; Kumar P. R. Synthesis and antidepressant activity of some 1, 3, 5-triphenyl-2-pyrazolines and 3-(2 ″-hydroxy naphthalen-1 ″-yl)-1, 5-diphenyl-2-pyrazolines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 5030–5034. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. A.; Siddiqui A. A. Pyrazoline derivatives: a worthy insight into the recent advances and potential pharmacological activities. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Drug Res. 2010, 2, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva P. E. A.; Ramos D. F.; Bonacorso H. G.; de la Iglesia A. I.; Oliveira M. R.; Coelho T.; Navarini J.; Morbidoni H. R.; Zanatta N.; Martins M. A. P. Synthesis and in vitro antimycobacterial activity of 3-substituted 5-hydroxy-5-trifluoro [chloro] methyl-4, 5-dihydro-1H-1-(isonicotinoyl) pyrazoles. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 32, 139–144. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi S. U. F.; Siddiqui H. L.; Johns M.; Detorio M.; Schinazi R. F. Anti-HIV-1 and cytotoxicity studies of piperidyl-thienyl chalcones and their 2-pyrazoline derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 3741–3749. 10.1007/s00044-011-9912-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir Z.; Kandilci H. B.; Gümüşel B.; Çalış Ü.; Bilgin A. A. Synthesis and studies on antidepressant and anticonvulsant activities of some 3-(2-furyl)-pyrazoline derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 373–379. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.; Younglove B.; Lee L.; LeBlanc R.; Holt Jr H.; Hills P.; Mackay H.; Brown T.; Mooberry S.; Lee M. Design, synthesis, and biological testing of pyrazoline derivatives of combretastatin-A4. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5897–5901. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burja B.; Čimbora-Zovko T.; Tomić S.; Jelušić T.; Kočevar M.; Polanc S.; Osmak M. Pyrazolone-fused combretastatins and their precursors: synthesis, cytotoxicity, antitubulin activity and molecular modeling studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2375–2387. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata A.; Nakagawa H.; Ohyama R.; Fukuuchi T.; Ohta S.; Suzuki T.; Miyata N. New series of antiprion compounds: pyrazolone derivatives have the potent activity of inhibiting protease-resistant prion protein accumulation. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 5053–5056. 10.1021/jm070688r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faidallah H. M.; Rostom S. A.; Khan K. A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of pyrazole chalcones and derived bipyrazoles as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2015, 38, 203–215. 10.1007/s12272-014-0392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ningaiah S.; Bhadraiah U. K.; Keshavamurthy S.; Javarasetty C. Novel pyrazoline amidoxime and their 1, 2, 4-oxadiazole analogues: Synthesis and pharmacological screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 4532–4539. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada N. M. M.; Abdo N. Y. M. Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial screening and free-radical scavenging activity of some novel substituted pyrazoles. Molecules 2015, 20, 10468–10486. 10.3390/molecules200610468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S. A.; Awad S. M.; Said A. M.; Mahgoub S.; Taha H.; Ahmed N. M. Design, synthesis, molecular modelling and biological evaluation of novel 3-(2-naphthyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives as potent antioxidants and 15-Lipoxygenase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 847–863. 10.1080/14756366.2020.1742116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A.; Husain A.; Khan S. A.; Mujeeb M.; Bhandari A. Synthesis, antimicrobial and antitubercular activities of some novel pyrazoline derivatives. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2016, 20, 577–584. 10.1016/j.jscs.2014.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban M. R.; Mayhoub A. S.; Farag A. M. Recent advances in the therapeutic applications of pyrazolines. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2012, 22, 253–291. 10.1517/13543776.2012.667403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes M. N.; Muratov E. N.; Pereira M.; Peixoto J. C.; Rosseto L. P.; Cravo P. V.; Andrade C. H.; Neves B. J. Chalcone derivatives: promising starting points for drug design. Molecules 2017, 22, 1210 10.3390/molecules22081210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M. H.; El-Hashash M. A.; Marzouk M. I.; El-Naggar A. M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel pyrazole, oxazole, and pyridine derivatives as potential anticancer agents using mixed chalcone. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2019, 56, 114–123. 10.1002/jhet.3380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nehra N.; Tittal R. K.; Ghule V. D. 1, 2, 3-Triazoles of 8-Hydroxyquinoline and HBT: Synthesis and Studies (DNA Binding, Antimicrobial, Molecular Docking, ADME, and DFT). ACS Omega 2021, 6, 27089–27100. 10.1021/acsomega.1c03668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade C. H.; Pasqualoto K. F.; Ferreira E. I.; Hopfinger A. J. 4D-QSAR: perspectives in drug design. Molecules 2010, 15, 3281–3294. 10.3390/molecules15053281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M. J. Defining optimum lipophilicity and molecular weight ranges for drug candidates—molecular weight dependent lower log D limits based on permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2844–2851. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A.; Lombardo F.; Dominy B. W.; Feeney P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 4–17. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A.; Michielin O.; Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkanzi N. A. A.; Hrichi H.; Alolayan R. A.; Derafa W.; Zahou F. M.; Bakr R. B. Synthesis of chalcones derivatives and their biological activities: a review. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 27769–27786. 10.1021/acsomega.2c01779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remko M. Theoretical study of molecular structure, pKa, lipophilicity, solubility, absorption, and polar surface area of some hypoglycemic agents. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 2009, 897, 73–82. 10.1016/j.theochem.2008.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pires D. E. V.; Blundell T. L.; Ascher D. B. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inc., C. C. G. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE); Chemical Computing Group Inc. Montreal: QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Chen J.; Cheng T.; Gindulyte A.; He J.; He S.; Li Q.; Shoemaker B. A.; Thiessen P. A.; Yu B.; Zaslavsky L.; Zhang J.; Bolton E. E. PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1388–D1395. 10.1093/nar/gkaa971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodinger, LLC . The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5.4; 2022.

- Valaparla V. K. Purification and properties of a thermostable [alpha]-amylase by Acremonium sporosulcatum. Int. J. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 6, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sreejayan M.; Rao M. Oxygen free radical scavenging activity of the juice of Momordica charantia fruit. Fitoterapia 1991, 62, 344–346. [Google Scholar]

- Nahar L.; Russell W. R.; Middleton M.; Shoeb M.; Sarker S. D. Antioxidant phenylacetic acid derivatives from the seeds of Ilex aquifolium. Acta Pharm. 2005, 55, 187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.