1. Introduction

A strong evidence base (Krieger, 2014; Marmot and Allen, 2014; Conrad and Barker, 2010; Adler and Stewart, 2010; Williams and Collins, 2001; Crocker and Major, 1989) offers important, while arguably, incomplete conceptualizations of the causal factors contributing to differences in specific health outcomes between groups defined by demographic characteristics such as socioeconomic position, race, ethnicity, and gender. Focusing on the magnitude of group differences in the prevalence or incidence of a specific disease outcome has yielded an incomplete assessment of the ways in which structural inequity breeds health inequity (Ward et al., 2019). Such counterfactual methods of measuring disparities necessitate the assumption of a normal or optimal health state, which has traditionally been based on outcomes observed among individuals occupying what many social theories (Turner and Avison, 2003; Krieger, 1990; Crocker and Major, 1989) consider the most privileged social position in the United States: White men. This approach does correctly assert that social disadvantage unjustly de-prives individuals of access to optimal health states. However, the White male referent overlooks two important considerations: one, that many health-impacting processes are not comparable across social groups due to the interdependency of these processes with social group membership (Bey et al., 2016, 2018a, 2018b, 2019; Schwartz, 2017; Slavich and Irwin, 2014; Harnois and Ifatunji, 2011), and two, that unjust advantage can also be disruptive of optimal health (Bey et al., 2016; Fujishiro, 2009), an idea which challenges the notion of the White male as a model of health.

Researchers have debated extensively on the challenge of establishing norms of health (Metzl, 2003, 2009; Amundson, 2000). The aim of this work is not to further engage this discussion but rather to contend that like illness resulting from relative deprivation, there are pathologies which arise from relative excess. Socially-constructed dominance and subordinance each confer vulnerability to specific diseases and resilience against others. A more accurate characterization of the mechanisms by which structural inequity acts to yield unequal health requires reconceptualizing notions of health and illness to be more inclusive of the often normalized symptoms of pathology exhibited by members of dominant-status groups.

An alternative approach considers a different measure of health disparity across socially-defined groups: the types of health and disease symptoms that are most prevalent within each of these groups. This approach allows for a broader view of the social patterns of health, one which, I will argue in this paper, positions hierarchical social conditions as detrimental even to the health of those occupying so-called “advantaged” positions. From this vantage point, we can see that structural inequity acts as a ubiquitously stressful environment that predisposes individuals to pathologies characteristic of their particular social position, and further, that status-based illnesses often manifest in practices that reinforce these social hierarchies.

In this paper, I present a new framework, the Identity Vitality-Pathology (IVP) model (formally Identity Pathology model (Bey et al., 2019), which approaches the assessment of health disparities from the perspective that many prevalent diseased or disordered states are identity-driven symptoms of structural inequity differentially manifest based on the unique ways in which groups located within varying social tiers adapt to the chronic stress of a ubiquitous pathogenic environment. My specific objectives are three-fold: to introduce the concept of IVP, a spectrum of health-determining identity characteristics that spans from health-promoting (vitality) to health-damaging (pathology); to outline a biologically-plausible role for identity as a moderator of the effects of structural inequity on healthy life expectancy, and to propose identity as an underexplored source of resilience that must necessarily be leveraged in order to effectively engage in the long work of deconstructing the inequitable social systems at the root of health inequity. I conclude with implications for alternative strategies to intervene on the health impacts of structural inequity, and for application of the IVP framework to epidemiologic research.

1.1. Existing theory from which the Identity Vitality-Pathology (IVP) framework draws

Structural inequity has been characterized as a “surround” (Krieger, 2014), a ubiquitous (although not ineluctable) environment conducive to the biopsychosocial processes that manifest as health inequities. The novel IVP model integrates existing theories in asserting that all processes which influence health are therefore a product of efforts to eliminate, profit from, adapt to, and/or cope with the constant pressures generated by inequitable social conditions.

At the root of these health-impacting processes is the categorization of individuals into distinct social tiers based on observable physical traits. Historically-rooted practices (Krieger, 2014; Smedley, 2007; Crocker and Major, 1989) have ensured the persistence of social hierarchies in the U.S. since the country’s inception. The most prevalent are determined based on physically distinguishable characteristics such as skin color, biological sex, or physical ability, in addition to less readily identifiable traits such as those associated with socioeconomic position or sexual orientation. The hierarchical categorization of innumerable human characteristics creates a matrix of social value that often renders the salience of hegemony situational. However, White and male supremacy codified into the U.S. legal and social structure have ensured a stable hierarchy in which whiteness and the masculine preside, while blackness and the feminine occupy the lowest tiers (Smedley, 2007; Kawachi et al., 2005; Butler, 1990; Crocker and Major, 1989). The rights, privileges, and restrictions associated with each stratum in this hierarchy may vary geographically and across several other identity traits but are nevertheless imposed on any individual whose physical characteristics meet the criteria for each tier.

Another fundamentally damaging aspect of structural inequity is that it drives the prevalent tendency to attach the value of a human being to that human being’s social identity tier. Despite cultural variation in what fulfills concepts of self-worth (Crocker and Park, 2004), human beings have a fundamental need to feel a sense of value, or a basic belief that one’s existence is contributing something measurably positive to the processes of the living world (Crocker and Park, 2004; Crocker, 2002). Concepts of self-worth are primarily learned through interactions with others and the social institutions in which individuals initially participate involuntarily from birth (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Crocker and Park, 2004). These interactions and institutions reside in an omnipresent context of structured social hierarchy, which dictates how value and worth are attributed to one’s position in that structure. The higher the social ranking of the group, the more valued the individual (Pratto et al., 1994; Blumer, 1958).

These hierarchies are reflected in notions of male and White supremacy (Jardina, 2019; Butler, 1990), in economic marginalization (Marmot and Allen, 2014), in ethnocentrism, in ablism (Amundson, 2000), etc. Whether consciously or unconsciously, individuals come to recognize the social value of the group to which they and others are assigned (Leach et al., 2008; Crocker and Major, 1989; Blumer, 1958). This recognition leads to internalization of a socially-constructed “value”, whereby individuals measure their own self-worth, rights, and entitlements against the way they perceive society’s valuation of the group to which they perceive themselves as belonging (Crocker and Park, 2004; Hughes and Demo, 1989; Romero and Roberts, 2003) Appraisal of others’ worth similarly considers the social status they are assigned as a result of readily identifiable characteristics such as race and gender (Quillian, 2008; Fein and Spencer, 1997; Blumer, 1958).

In addition to shaping the external social processes that separate individuals into specific social positions according to observable characteristics and assign corresponding value, structural inequity influences internal processes that govern the acquisition of social identity paradigms into one’s self-concept. It has been long established that identity paradigms, or the ways in which individuals conceptualize the “self”, are influenced by the social tiers they occupy (Blumer, 1958). Socially- and culturally-embedded messages serve as repositories for ideas which outline criteria for membership in distinct social groups; the attitudes, behaviors, ideals, and entitlements unique to these groups; and the social value of each group as dictated by the group’s position in the social hierarchy (Jardina, 2019; Blumer, 1958). This process describes the social construction of identity categories (for example, race and gender). As individuals are exposed to the social and cultural cues that trigger awareness of the group(s) to which they are assigned based on their own external physical characteristics and ancestry, they acquire a set of beliefs from which they consistently draw in defining their own identities. This secondary process of localizing self within an identity paradigm describes the adoption of a socially-constructed identity, or self-investment (Leach et al., 2008).

Social group identification is typically thought to encompass three independent but related aspects of self-definition and self-investment: identity ideology, identity regard, and identity centrality (Leach et al., 2008). Ideology refers to the paradigms or sets of beliefs one draws from in defining one’s social identity (Leach et al., 2008; Tajfel and Turner, 1986). Regard captures the perception of one’s social identity as positive or negative, an appraisal dependent largely on perceived value (Leach et al., 2008; Crocker and Park, 2004). Centrality describes how integral to one’s self-concept one ranks a specific identity, as well as the frequency with which one intentionally or unintentionally accesses that particular social identity in navigating the environment (Leach et al., 2008). These three aspects of social group identification have been independently shown to be both protective and damaging to health (Yip, 2018; Forsyth and Carter, 2012; Smart Richman and Jonassaint, 2008; Fujishiro, 2009; Leach et al., 2008; Crocker, 2004; Baumeister et al., 2003). Further, identity ideology, regard, and centrality are in concert believed to yield susceptibility to a type of health-damaging stressor (Berjot and Gillet, 2011) termed identity threat (Steele et al., 2002).

Encounters which challenge deeply-held beliefs about self and others can serve as identity threats (Steele et al., 2002; Baumeister and Cairns, 1992; Festinger, 1957; Blumer, 1958). When adopted identity paradigms incorporate socially-constructed notions of race and gender, the process of self-identification necessarily yields a cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) that is a root cause of identity threat. This dissonance, or psychological distress caused by holding multiple contrary beliefs concurrently (Festinger, 1957), is based in irreconcilable inconsistencies between socially-defined identity categories and observable variation in human existence. In other words, rather than fitting identity paradigms to the reality of human capacity and variation, social constructs of identity are created to maintain hierarchical relationships between social groups and to force the adoption of realities which instead fit these constructed identity paradigms. The process of maintaining these skewed identity beliefs in the absence of dissonance can require subscription to, and ardent defense of, the myths that legitimize the superordinance of one group over another (Pratto et al., 1994; Davis and Jones, 1960; Blumer, 1958).

Baumeister (1991) previously proposed the notion of “personal” identity maintenance as a source of substantial stress, particularly as self-image is damaged. More recent work extends this theory in outlining how the physiological reaction to a perceived threat against one’s social identity, like a perceived physical threat, entails activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary axis (HPA) as the body responds to the mind’s perception of danger (Slavich and Irwin, 2014). The stress stemming from a perceived threat to the fundamental ideas one holds about one-self—one’s rights, privileges, abilities, and most importantly, one’s worth, can be both acute and chronic. Experiencing interpersonal discrimination, for example, can act as an acute identity threat (Berjot and Gillet, 2011). Recognition of structural inequity, on the other hand, can be experienced as chronically stressful even in the absence of readily identifiable stressors (Brosschot et al., 2018), as is evidenced in recent work on race-based trauma (Forsyth and Carter, 2014). Chronic stress stemming from perceived devaluation on the basis of one’s membership in a social group has been shown to exert a unique physiological and psychological effect (Slavich and Irwin, 2014; Berjot and Gillet, 2011; Harrell et al., 2003; Steele et al., 2002; Reynolds and Pope, 1991).

In the context of toxic stress resulting from exposure to chronic stressors (Slavich and Irwin, 2014; McEwen, 2000), sustained sympathetic activity can cause lasting physiological changes to the structure and chemical activity of the brain (LeDoux et al., 1991; McEwen, 2000; van der Kolk and Bessel, 2005, 2014), and subsequently lead to the long-term physiological dysregulation and associated epigenetic alterations underlying many chronic mental and physical diseases (McEwen, 2000; Slavich and Irwin, 2014), as proposed by geroscience theory (Sierra, 2016). The effect identity exerts on the experience of stress is therefore predicated upon both the content of the identity (ideology) and the degree to which it is centralized within an individual’s self-concept (Leach et al., 2008; Steele et al., 2002; Berjot and Gillet, 2011). The more central the identity, the greater the potential for health-damaging stress caused by identity threat (Leach et al., 2008; Steele et al., 2002; Berjot and Gillet, 2011).

Traditional stress theory (e.g., Cassel, 1976; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) further complicates these narratives, however, by identifying stressor appraisal as a modulator of the effect of stressor exposure on the stress response system. Further, strong evidence unpacks psychosocial influences on stress appraisal and stress-related health behaviors (Bey et al., 2019; Cassel, 1976). Affect and optimism, for example, have been shown to predict the perception of stress associated with stressful events (Baumgartner et al., 2018; Eschleman et al., 2012). Recent studies have also demonstrated variation in the association of optimism and affect with stress-related health behaviors across ethnoracial groups (Boehm et al., 2018; Ellis et al., 2015). This evidence, along with research identifying associations of identity-related psychosocial traits with cognitive health (Gawronski et al., 2016; Sutin et al., 2018), suggests a potential moderating role for psychosocial factors in the effects of chronic stressors on aging and downstream health outcomes.

2. Novel theoretical contributions of the Identity Vitality-Pathology framework

In this section, I will describe the novel theoretical contributions of the IVP framework, which integrate and extend existing theory on the role of structural inequity in health inequity to outline a role for socially-constructed identity in influencing susceptibility and resilience to specific health and disease states.

2.1. Defining identity vitality and pathology

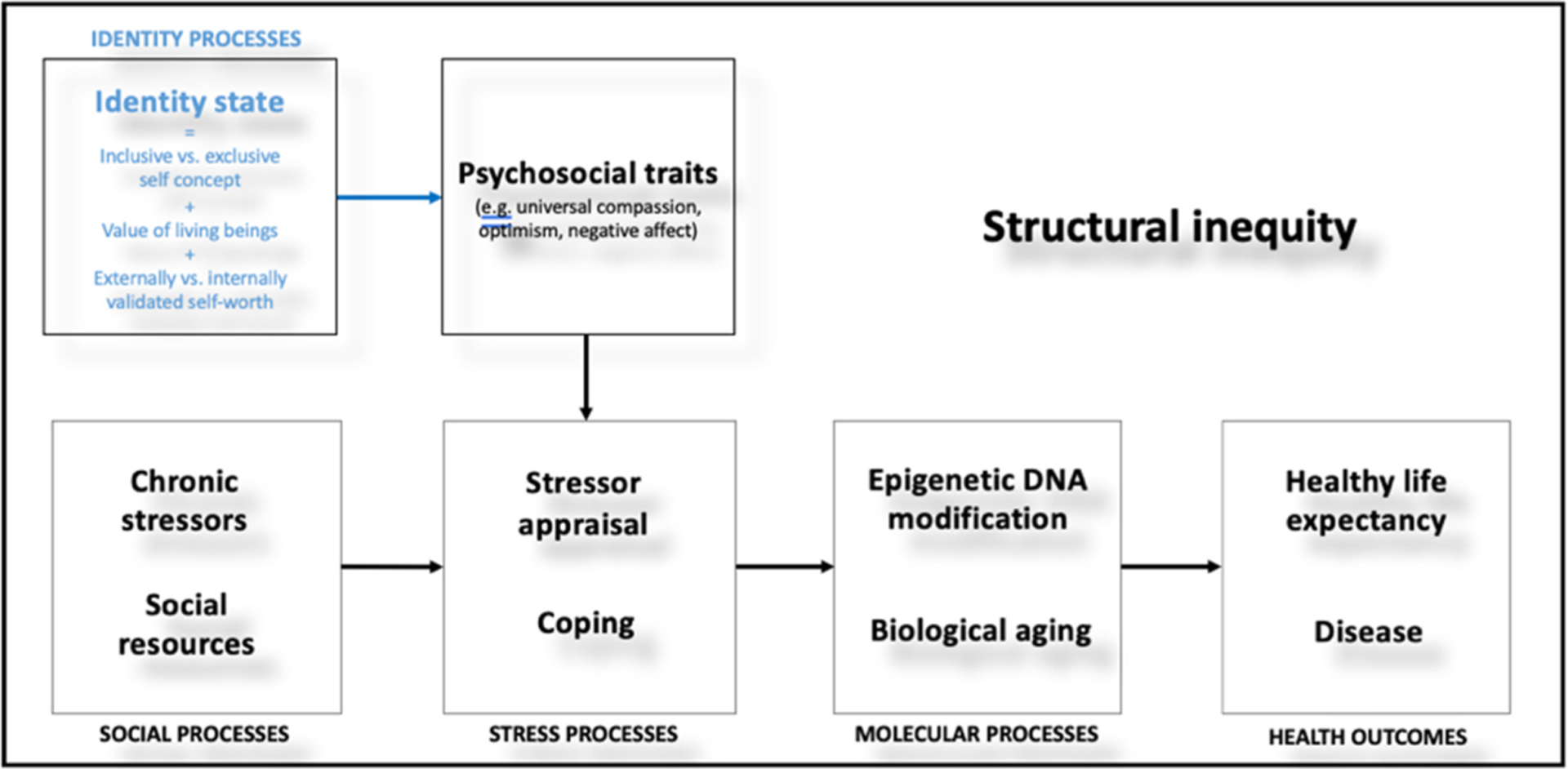

The IVP framework explicitly links self-concept to health through identity-related beliefs about worth and social status (Fig. 1). The model characterizes the set of modifiable identity beliefs that can either be disease-promoting (pathogenic), or health-promoting (salutogenic), as an identity state. This modifiable set of identity beliefs includes the ways individuals primarily conceptualize: 1) an internalized, stable identity, 2) the value of living beings, and 3) whether concepts of self-worth are attached to external evaluations. The determination of these components as critical to physiological risk and resilience is based, in part, on existing theory and evidence outlining the roles of inclusive identities (Cross Jr. and Vandiver, 2001; Helms, 1990; Myers et al., 1991), loving compassion (Kahana et al., 2021; Lopez et al., 2018; Myers et al., 1991), and inherent self-worth (Crocker and Knight, 2005) in well-being. The IVP framework builds on this theory and evidence, positing that these three factors comprising an individual’s identity state influence how they appraise and cope with stress, and that this modulation of stress processes has direct implications for the physiological processes underlying both mental and physical health.

Fig. 1.

The Identity Vitality-Pathology framework positions identity processes (highlighted in blue) as moderators of the pathways from social, stress, and molecular processes to health and disease in the context of structural inequity.

Identity states as defined by IVP theory exist on a spectrum from “vitalized” to “pathological” which can be captured using a scale. On the vitalized end of the spectrum, identity vitality allows for resilience to the harmful psychophysiological effects of chronic social status-based stress, while on the other end, identity pathology increases susceptibility. Identity vitality is defined as a salutogenic state characterized by a superordinate, inclusive self-concept, a belief in the inherent equitable value of all living beings, and a resulting stable, inherent sense of self-worth independent of external evaluations. An example of a vitalized identity includes one characterized by compassion that is rooted in a conceptualization of self as one with other living beings, akin to Myers’ framing of an Afrocentric worldview (Myers et al., 1991). Stemming from this compassion is the belief that every living being, including oneself, has an inherent value that is independent of their behavior, group, or social position even as they may require a unique set of resources or opportunities to flourish. In this vitalized state, individuals are unlikely to perceive identity threat even in those contexts that are considered dehumanizing to others and are therefore less likely to experience status-based stress with its health-damaging repercussions. In contexts where such stress is perceived, identity vitality widens the individuals’ perceived sphere of control and self-efficacy (as has been previously indicated in self-concept (Markus and Wurf, 1987)), enabling a broader range of stress-responsive behavior and adaptive coping.

On the other end of the identity state spectrum is identity pathology (distinct from the psychopathologies previously described as identity pathology by (Kaufman and Crowell, 2018). Identity pathology is a pathogenic state characterized by an identity grounded in physical traits, the belief that a person’s worth depends on their social position, and a sense of self-worth dependent on external evaluation. An example of a pathologized identity is one characterized by supremacist (ethnoracial, gender, or otherwise) beliefs which adhere to the legitimizing myths (Pratto and et al., 1994) that position socially-defined groups as dominant or subordinate. This state creates dependency on the dominance of one’s group for a source of value which cannot subsist without the perpetuation of structured inequity. This in turn creates susceptibility to the harmful effects of external definitions of value, requires an ardent defense of the inherent superiority of specific physical or social characteristics, and promotes engagement in the practices that maintain the superiority of one’s own group. In this pathologized identity state, individuals are more likely to perceive identity threat within the social environment (such as is associated with perceived discriminatory treatment or displacement from rightfully filled positions) that triggers harmful conditioned stress responses and exacts a physiological toll. This state also narrows the range of responses to stress individuals feel are permitted by their self-concept. By doing so, identity pathology increases susceptibility to environmental influences on maladaptive coping and poor health behaviors and can result in a perceived necessity to reinforce social hierarchy in efforts to resolve threats to one’s identity.

Patterns of behavior demonstrated in response to identity threat are consistent with this theory. When positive self-image is threatened, individuals are more likely to engage in prejudiced behaviors against, and socially distance themselves from, members of marginalized groups (Jardina, 2019; Fein and Spencer, 1997), even when they, too, possess stigmatized identities. The lengths to which individuals go to avoid the sense of worthlessness stemming from an inability to be perceived as superior to others extend beyond interpersonal interactions, as do the consequences of such behaviors. Engaging in practices that uphold the perceived supremacy of the groups to which individuals perceive themselves as belonging is one method of ensuring the availability of a sense of worth gained only through comparison with outgroup members. White supremacy, for example, drives voting behaviors intended to concentrate political and economic power in the hands of those whom voters believe will enact policies and legislation that maintain White supremacy (Jardina, 2019; Metzl, 2019). Although such individual practices of White supremacy may yield short-term psychological relief from identity threat (Jardina, 2019), many individuals suffering pathologized White identities not only negatively impact other ethnoracial groups through prejudiced behaviors but also suffer the health, economic, and social consequences of their own voting choices (Jardina, 2019; Metzl, 2019).

2.2. Social group variability in the health manifestations of identity vitality and pathology

For the purposes of demonstrating the application of IVP theory to the epidemiologic study of health disparities, I will use the example of the two socially-constructed identities which have been the focus of this paper thus far, race and gender, among four groups who occupy different tiers within a historically-grounded social hierarchy: U.S.-born Black and White women and men.

In additional to the material resources that shape the experience and expression of identity-based stress, the unique manifestations of health and disease associated with specific identity states across different social groups is partially attributable to the compound effect of multiple intersecting identities. Individuals identifying as and identified as both female and White, or male and Black, occupy both subordinate (female and Black) and dominant (White and male) social positions in the U.S. social hierarchy. This simultaneous disempowerment and privilege creates an incongruence between the socially-constructed racial and gender identities of White females and Black males that may yield a unique form cognitive dissonance. Members of these groups may therefore be more prone to underlying identity states distinct from those of Black women and White men.

Identity pathologies in which self-worth is predicated on an unattainable, but desired social status underlies prevalent disease manifestations among White women and Black men because members of these groups may perceive similar barriers to the expected benefits of their so-called advantaged social positions. Black men can experience barriers to the full practice of socialized concepts of masculinity due to racism. Increased risk social and material deprivation, for example, can confound Black men’s ability to occupy such roles of primary bread-winner associated with traditional concepts of masculinity. For those Black men adhering to pathologized identities, these barriers can facilitate identity threat, as well as associated cognitions and health behaviors that increase risk for a host of chronic disease conditions, for example cardiovascular disease, associated with inflammation (Chae, 2010; James, 1994). Likewise, for White women, structural sexism and gender discrimination impedes access to the full perceived benefits of whiteness. The historical disenfranchisement of women presently persists in a variety of forms (Bey, 2020). Relying on the socialized value of whiteness, white women suffering identity pathology may therefore struggle to identify sources of self-worth within the context of a system that simultaneously devalues their womanhood. This may result in a predisposition for identity threat, and the associated cognitions and health behaviors that predispose members of this group to inflammation-driven depressive disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999). These hypotheses are supported by emerging evidence of a link between cardiovascular disease and depression (Mattina et al., 2019; Dhar and Barton, 2018), making a case for the assertations that a) Black men and White women may share identity pathologies that manifest distinctly based on sociocultural contexts, and b) ostensibly dissimilar symptoms of illness may stem from shared disease origins (Bey et al., 2018b; Wright et al., 2014).

The identity pathologies and associated physiological manifestations of White males and Black females differ from those of Black males and White females. White males occupy both racially and gender superordinate social positions within the U.S. hierarchical social structure and are therefore more likely to be socialized to adopt identity paradigms which rely primarily on socially-constructed self-worth derived from comparison with out-group members. Without exposure to the subordinate status associated with increased risk of internalizing and inflammatory responses to chronic stress (Slavich and Irwin, 2014), White males are more likely to exhibit psychological symptoms of chronic identity-based stress through externalized control-reinforcing behaviors not commonly considered indicative of pathology. Subscribing to socially-constructed White male identity paradigms not only increases susceptibility to antisocial tendencies attributable to pathologized whiteness, including lack of empathy, feelings of entitlement, and behaviors to reinforce feelings of control (Batavia, 2019; Kavanagh et al., 2013; Becker, 1994; Helms, 1990), but also externalizing disorders driven by pathogenic masculinity that manifest through violent or aggressive behavior toward self and others (Baumeister et al., 2000; Metzl, 2019). This perpetuation of both interpersonal and structural violence as a practice of pathologized White male identity ensures access to a disproportionate share of social and material resources for members of this group, thereby decreasing susceptibility to the physical disorders promoted by material deprivation.

On the other hand, dominant narratives of White and male identity which distance whiteness from poverty (Kuntsman et al., 2016) ensure that certain groups of White men are particularly susceptible to the psychological health consequences of identity pathology. With increased dependence on superior status for a sense of self-worth, not being afforded the expected privileges of White male membership can exacerbate the negative health effects of poverty. Poor White men, for example, face increased risk of depression, and substance abuse may serve as a form of coping (Metzl, 2019; Baumeister, 1991) for those White men not succumbing to other self-destructive compulsions of identity pathology such as suicide (Metzl, 2019; Oliffe et al., 2015; Baumeister, 1990, 1991).

In contrast, the necessity for adaptive coping with intersecting forces of structured violence enables the development of psychological durability within Black female identity paradigms that is protective against psychological symptoms of identity-based stress (Neblett et al., 2012). Devalued on the basis of both their race and gender, Black women have been compelled to develop alternative standards by which to assess their value. Deprived of access to sources of socially-constructed worth, Black women subscribing to dominant Black female identity paradigms may appraise potential identity threats in a manner distinct from other groups. Specifically, acute, interpersonal experiences of potential identity threat may be perceived as less threatening. Previous research grounded in IVP theory indicates, for example, that reported lifetime gender and racial discrimination in certain settings is associated with poorer cardiovascular health among Black men, White women, and White men, but not Black women (Bey et al., 2019) In this way, by enabling a greater sense of self-efficacy in which Black women feel capable of determining for themselves standards against which their value will be measured (St. Jean and Feagin, 2015), intersectional forces of disempowerment may confer individuals subscribing to dominant Black female identity paradigms a measure of protection against the psychological manifestations of the very chronic identity threat they cause.

In further support of this hypothesis, research demonstrates that allostatic load, a measure of cumulative physiological dysregulation stemming from chronic stress that precedes and correlates highly with many chronic diseases (McEwen, 2000), is associated with depression among Black men and White women, but not Black women or White men (Bey et al., 2016). Furthermore, there is indication that the underlying neurobiology of depression differs among Black women compared with Black men, White women, and White men, with Black women being the only of these groups among whom no indicators of inflammation were associated with depressive symptoms (Bey et al., 2018b, Morris, 2011). The depressive response to deprivation among Black women may not be a function of a perceived threat to deeply-held self-concepts that promotes sustained inflammation, as IVP theory argues is more likely to be the case among Black men and White women. Instead, the substantial prevalence of depressive symptoms among Black women may instead be a psychoneuroendocrinological manifestation accurately corresponding to the unique multiply-disadvantaged social conditions in which Black women are disproportionately situated. Evidence that accounting for socioeconomic status eliminates the gender disparity in depression among Black persons but not White (Dunlop et al., 2003) further supports the assertion that symptoms of depression among Black women may be indicative of a stress response that is distinct from the pathology manifest in depressive symptoms among other gendered race groups.

Pathological identity states of Black women manifest in physical vulnerabilities that stand in contrast with this proposed psychological resilience. High rates of obesity, hypertension, and poor maternal/neonatal outcomes in this group reflect a unique adaptation to structural inequity—metabolically, rather than psychologically, exhibiting pathology. Dominant sociocultural narratives rank Black women at the bottom in most highly-regarded social dimensions—physical beauty, intellectual capability, etc. (St. Jean and Feagin, 2015), but celebrate their caregiving, selfless, mothering natures (Black and Peacock, 2011; Woods-Giscombe and Cheryl, 2010). In addition to the structural racism and sexism that concentrates economic deprivation and limits the capacity for health-promoting behaviors within Black female populations (DuMonthiers et al., 2017; St. Jean and Feagin, 2015; Crocker and Major, 1989), Black female identity paradigms demand what can be argued as a pathological minimization of self-care in efforts to be valued as caregiver (Woods-Giscombe and Cheryl, 2010; Beuboef-Lafontant and Tamara, 2007). As Superwoman Schema theory suggests, in prioritizing the needs of others, Black women often silently bear an extensive familial and community burden at the cost of their own emotional and physical needs (Woods-Giscombe and Cheryl, 2010). Adherence to these gendered race-specific identity paradigms predisposes Black women to automated coping such as emotional eating (Hayman et al., 2015; Thompson, 1994), other risk-factors for obesity such as postpartum weight retention (Headen et al., 2012), and other health-impacting behaviors such as low health services utilization (Black et al., 2012). Furthermore, another form of identity pathology characterized by a failure to acknowledge the existence, or negative psychological impacts, of structural inequity can promote denial and internalization which may lead to premature disease and mortality in this group (Bey et al., 2019; Dunlay et al., 2017).

2.3. Promoting identity vitality: a newly proposed intervention on health disparities

As I have previously described (Bey, 2020), much of the theory on social determinants of health predicates the health of the socially marginalized on a set of resources of which they are systematically deprived (Krieger, 2014; Phelan et al., 2010; Crocker and Major, 1989). As such, any improvements in the health of members of marginalized groups are necessarily dependent on the decisions of those who retain power over the distribution of these resources, individuals who have little incentive to relinquish their positions of authority (perceived and actual) or enact more inclusive policies. If structural inequities and the illnesses such conditions cause are to be truly deconstructed, intervention must entail more than efforts to change social and economic policies which were intentionally established to ensure that power and resources remain under the control of White men (Jardina, 2019; Kendi, 2016; Smedley, 2007; Crocker and Major, 1989).

The persistence of documented health disparities over the last century despite long-standing calls for social, economic, and political reform as well as substantial advances in our understanding of the role of social determinants indicates that these policies and the decision-makers behind them are resistant to change. Because pathogenic identity beliefs perpetuate the pathogenic social environments of inequity in which they flourish, effective interventions must target the environment, agent, and host simultaneously (Bey, 2020). To further extend the infectious disease metaphor, IVP theory suggests that ideas, people, and cultures can serve as “reservoirs of infection”, or locations with favorable conditions for the persistence and multiplication of pathogenic agents (Viana et al., 2014). The reservoirs of infection that stubbornly harbor pathogenic identity beliefs even as a dynamic public discourse variably decreases or increases the acceptability of social group prejudice ensure that interventions focusing only on shifting policy will do little to yield lasting social equity. Eradicating health disparities therefore requires an additional approach (host interventions) that acts in conjunction with efforts to deconstruct problematic institutions and policies (environment interventions), and efforts to create identity-safe cultures (agent interventions).

In consideration of this need, the IVP framework seeks to capitalize on the underexplored opportunity of promoting identity vitality as a means of building widespread resilience to the detrimental effects of inequitable social environments. IVP theory offers the concept of identity inoculation, a type of host intervention which acts at the individual level as both a “treatment” for identity pathology and as a buffer against “infection”, one which promotes identity vitality. Identity inoculations have one primary objective: to provide immunity against infection with any identity beliefs which predicate the worth of a human being on that human being’s social position. In order to successfully guard against harboring such pathogenic identity beliefs, identity inoculations allow for the development of vitalized identities, or alternative concepts of self which enable a sense of self-worth that is not dependent on social status and therefore requires no relational evaluation or external validation, and which have the protective and normative property of illuminating inherent value in equitable identities. This theory is in line with well-established health benefits of a focus on developing a sense of innate self-worth (internal validation of value) in contrast with the detrimental effects of seeking external validation of value (Crocker and Park, 2004). Importantly, operating under these vitalized identity paradigms should enable individuals to actively reject the status-reinforcing narratives, ideals, and behaviors that uphold hegemonic social structures at the root of health inequity.

Researchers have successfully demonstrated interventions on prejudice with lasting effects (Devine et al., 2012). The identity intervention called upon by the IVP framework incorporates similar principles but extends beyond intervening on unconscious biases among those reporting non-prejudiced goals to intervening on the very concept of “otherness” on which prejudice is based. Mindfulness interventions have also been shown to increase brain plasticity (Tang et al., 2015; Xiong and Doraiswamy, 2009), which provides promising evidence that even adults can become more amenable to accommodating rather than assimilating new identity beliefs and develop values opposed to prejudice that will form the basis for long-term behavioral change.

3. Conclusions

This paper presents the Identity Vitality-Pathology model, a new, comprehensive framework which proposes a unique role for identity in moderating the effects of structural inequity-driven chronic stressors on health disparities. The IVP framework situates the spectrum of vitalized to pathological identity states, characterized by modifiable beliefs regarding an internalized, stable identity, the value of living beings, and concepts of self-worth, as an important pathway over which such effects act. Given the ubiquitous nature of structural inequity within the U.S., IVP theory posits that most people may be socialized to succumb to pathologized identities. With few catalysts and little support for a fundamental reconceptualization of self, individuals are unlikely to independently undertake the challenging and ongoing process of moving toward a vitalized identity state and will therefore be highly susceptible to environmental influences on health over the life-course. Importantly, IVP theory circumvents the trap of “victim-blaming” by meeting the call for greater attention to context, both situational and historical, within positive psychology (Ciarrochi et al., 2016). Rather than conceptualizing identity states as inherent and independent of context, IVP theory names the specific social structures, including structurally-embedded systems of hegemony, that shape the cultural, political, and social norms foundational to the construction and adoption of identity. IVP theory therefore suggests the necessity for identity interventions, in addition to interventions targeting institutional and cultural drivers of inequity, in reducing unequal health outcomes.

Furthermore, IVP theory outlines biologically-plausible mechanisms for a role of identity states in influencing variability in the manifestations of health and disease outcomes across socially-defined groups. The example given herein describes how succumbing to pathological racial and gender identities constructed in the context of inequitable social conditions converge to create unique manifestations of identity pathology among Black and White women and men. While the disproportionate access to economic resources and positions of power may be protective against physical symptoms of poor health, these social injustices increase risk for psychological disorders that ultimately lead to suboptimal quality of life and unnecessary death even among those ranked in higher social positions. Multiply-marginalized persons, on the other hand, in embracing ideals of caregiving and selflessness, may experience resilience to the psychological manifestations of exposure to a pathogenic social environment, but be more vulnerable to physical symptoms. Likewise, the simultaneous disempowerment and privilege built into the identity paradigms of Black men and White women confer a unique susceptibility to identity-based stress on account of an idealized but inaccessible social status. In this way, the IVP framework is distinct from other theoretical frameworks relevant for health disparities in that it hypothesizes an additional source of risk and resilience—pathological or vitalized identity states—as a modifiable target for bringing all people closer to ideal states of health.

The theory outlined in the IVP framework, while in many ways consistent with common understandings of the role of hierarchical social conditions in health outcomes, stands in contrast with predominant discourses on health disparities in other ways. The IVP model challenges the adversarial approach of reducing social groups to those who are “privileged” and “disadvantaged” by structural inequity. The majority of people do not stand to gain from the continued practice of structural violence, yet the vernacular of social science and social justice alike often promotes the notion of a readily identifiable beneficiary. The suffering of those who occupy subordinate positions is far more visible, recognizable, and measurable than the suffering of those who appear to enjoy the material privileges of their dominant status. Yet, many members of socially dominant groups are likewise hostage to a system that does not work to their benefit as are those to whom they have been socialized to direct blame.

There are, of course, important distinctions in the ways in which groups positioned within different social strata contribute to the perpetuation of unnecessary and unjust suffering. While the disease symptoms of marginalized populations have minimal effect on the health and well-being of dominant status groups, the identity pathologies exhibited by members of socially dominant groups have profound impacts on the health of marginalized persons. The practices of discrimination and violence characteristic of dominant group identity pathology force marginalized groups disproportionately into the social conditions that cause poor physical health and create dependence on exploitive healthcare systems, the economic beneficiaries of which are overwhelming White men (Schumpeter, 2015). So, while “privilege” may not fully capture the consequences of structural inequity for members of dominant status groups, the term does acknowledge the disproportionate amount of power and social capital which has been unjustly placed in the hands of individuals who will sacrifice even their own well-being to ensure that the group with which they have been socialized to identify remains dominant. Even still, the IVP framework emphasizes that the costs of structural inequity, while not equally borne, are high for the vast majority of all people, regardless of social group, who have been conditioned to participate in social hegemony.

In this paper, I have focused on race and gender hierarchy among Black and White women and men to illustrate the application of IVP theory to the study of health outcomes differences. The utility of the IVP framework, however, extends beyond these particular groups and instances of structural inequity. The principles of the IVP framework can be adapted to describe the effects of any inequitable social contexts on the physical and psychological well-being of any populations exposed to those contexts. The IVP framework may be particularly useful for examining the understudied health impacts of structural inequity among groups such as those with varying physical abilities or native populations whose suffering has been systematically made invisible.

The framework is densely theoretical and draws from several disciplines in outlining complex mechanisms from structural inequities to health inequities. Despite its ambitious reach, the core concepts of the framework are readily applicable to health research. Through IVP outlining testable causal mechanisms and proposing an evidence-based intervention, the IVP model orients health researchers toward another channel for investigating the mechanisms of and solutions to health disparities. Although a measure of the identity vitality-pathology spectrum has yet to be validated, such a measure has potential to serve as an important tool for capturing a hypothesized modifiable antecedent—identity state—to psychosocial factors predictive of aging, health, and disease.

In addition to its utility for epidemiologic research, another central objective of the IVP framework is to outline ways of empowering individuals to feel a greater sense of efficacy in the outcomes of not only their health, but of their lives. Acknowledging the limitations that structural inequity imposes, IVP theory conceptualizes ways of bringing individuals measurably closer to operating at the capacity of their influence on the factors over which they do have control. By providing accessible tools with which to identify and combat the toxic stress of structural inequity, the IVP framework proposes methods with which individuals can actively participate in the betterment of their own health while simultaneously contributing to a more just society.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Gerardo Heiss, Cheryl Woods-Giscombe, and Barbara Frederickson for their generous guidance in the development of this work.

This work was supported by funding from the Columbia University Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Alzheimer’s Disease Disparities, grant number 5P30AG059303–04.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Adler Nancy E., Stewart Judith, 2010. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1186 (1), 5–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundson Ron, 2000. Against normal function.Stud. History, Philosoph., Biol. Biomed. Sci 31 (1), 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Batavia, et al. , 2019. The elephant in the room: a crucial look at trophy hunting. Conserv. Lett 12 (1). [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, 1990. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol. Rev 97, 90–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, 1991. Escaping the Self: Alcoholism, Spirituality, Masochism, and Other Flights from the Burden of Selfhood. Basic Books, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Cairns KJ, 1992. Repression and self-presentation: when audiences interfere with self- deceptive strategies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 62, 851–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bushman BJ, Campbell WK, 2000. Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: does violence result from low self- esteem or from threatened egotism? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 9, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD, 2003. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol. Sci. Publ. Interest 4, 1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister Roy F., Leary Mark R., 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull 117 (3), 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner JN, Schneider TR, Capiola A, 2018. Investigating the relationship between optimism and stress responses: a biopsychosocial perspective. Pers. Indiv. Differ 129, 114–118. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, 1994. Offenders: characteristics and treatment. Sexual Abuse Chil. 4 (2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berjot, Sophie, Gillet, Nicolas, 2011. Stress and coping with discrimination and stigmatization. Front. Psychol 2 (33). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuboef-Lafontant Tamara, 2007. You have to show strength: an exploration of gender, race, and depression. Gend. Soc 21 (1). [Google Scholar]

- Bey Ganga S., 2020. Health disparities at the intersection of gender and race: beyond intersectionality theory in epidemiologic research. In: Irtelli F, Durbano F, Taukeni SG (Eds.), Quality of Life—Biopsychosocial Perspectives. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Bey Ganga S., Waring Molly E., Jesdale Bill M., Person Sharina D., 2016. Gendered race modification of the association between chronic stress and depression among Black and White U.S. adults. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 88 (2), 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey Ganga S., Ulbricht Christine M., Person Sharina D., 2018a. Theories for race and gender differences in management of social identity-related stressors: a systematic review. J. Racial Ethnic Health Disparities 10.1007/s40615-018-0507-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey Ganga S., Jesdale Bill M., Ulbricht Christine M., Mick Eric O., Person Sharina D., 2018b. Allostatic load biomarker associations with depressive symptoms vary among U.S. black and white women and men. Healthcare 6 (3), 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey Ganga S., Jesdale Bill M., Forrester Sarah, Person Sharina D., Kiefe Catarina, 2019. Intersectional effects of racial and gender discrimination vary among black and white women and men in the CARDIA study. Soc. Sci. Med.-Population Health 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Angela R., Peacock Nadine, 2011. Pleasing the masses: messages for daily life management in African American women’s popular media sources. Am. J. Publ. Health 101 (1), 144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Angela R., Woods-Giscombe Cheryl, 2012. Applying the stress and ‘strength’ hypothesis to black women’s breast cancer screening delays. Stress Health 28 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer Herbert, 1958. Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pac. Socio Rev 1 (1). [Google Scholar]

- Boehm Julia, Chen Ying, Koga Hayami, et al. , 2018. Is Optimism Associated With Healthier Cardiovascular-Related Behavior? Meta-Analyses of 3 Health Behaviors. Circ. Res 122 (8), 1119–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot Jos F., Verkuil Bart, Thayer Julian F., 2018. Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress: unsafe environments and conditions, and the default stress response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 15 (464). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler Judith, 1990. Gender Trouble. Routledge, Chapman & Hall, Inc, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel J, 1976. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Am. J. Epidemiol 104 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, et al. , 2010. Do experiences of racial discrimination predict cardiovascular disease among African American men? The moderating role of internalized negative racial group attitudes. Soc. Sci. Med 71 (6), 1182–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Atkins PWB, Hayes LL, Sahdra BK, Parker P, 2016. Contextual positive psychology: policy recommendations for implementing positive psychology into schools. Front. Psychol 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad Peter, Barker Kristin K., 2010. The social construction of illness: key insights and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav 51 (1), S67–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker Jennifer, 2002. The costs of seeking self-esteem. J. Soc. Issues 58 (3). [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Knight KM, 2005. Contingencies of self-worth. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 14 (4), 200–203. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker Jennifer, Major Brenda, 1989. Social stigma and self-esteem: the protective properties of stigma. Psychol. Rev 96 (4). [Google Scholar]

- Crocker Jennifer, Park Laura E., 2004. The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychol. Bull 130 (3), 392–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE Jr., Vandiver BJ, 2001. Nigrescence theory and measurement: introducing the cross racial identity scale (CRIS). In: Handbook of Multicultural Counseling, second ed. Sage Publications, Inc, pp. 371–393. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Keith E., Jones Edward E., 1960. Changes in interpersonal perception as a means of reducing cognitive dissonance. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol 61 (3), 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine Patricia G., Forscher Patrick S., Austin Anthony J., Cox William T., 2012. Long-term reduction in implicit bias: a prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol 48 (6), 1267–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar Arup K., Barton David A., 2018. Depression and the link with cardiovascular disease. Front. Psychiatr 7 (33). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuMonthiers Asha, Childers Chandra, Milli Jessica, 2017. The Status of Black Women in the united states. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlay SM, et al. , 2017. Perceived discrimination and cardiovascular outcomes in older African Americans: insights from the Jackson Heart Study. Mayo Clin. Proc 92 (5), 699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop Dorothy D., Song Jing, Lyons John S., Manheim Larry M., Chang Rowland W., 2003. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am. J. Publ. Health 93 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Erin, Orom Heather, Giovino Gary, Kiviniemi Marc, 2015. Relations between negative affect and health behaviors by race/ethnicity: Differential effects for symptoms of depression and anxiety. Health Psychol. 34 (9), 966–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschleman KJ, Alarcon GM, Lyons JB, Stokes CK, Schneider T, 2012. The dynamic nature of the stress appraisal process and the infusion of affect. Hist. Philos. Logic 25 (3), 309–327. 10.1080/10615806.2011.601299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein Steven, Spencer Steven J., 1997. Prejudice as self-image maintenance: affirming the self through derogating others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 73 (1), 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger Leon, 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth Jessica, Carter Robert T., 2012. The relationship between racial identity status attitudes, racism-related coping, and mental health among Black Americans. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol 18 (2), 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth Jessica, Carter Robert, 2014. Development and preliminary validation of the Racism-Related Coping Scale. Psychol. Trauma: Theor. Res. Pract. Pol 6 (6), 632–644. [Google Scholar]

- Fujishiro K, 2009. Is perceived racial privilege associated with health?” Findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Soc. Sci. Med 68 (5), 840–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski KAB, Kim ES, Langa KM, Kubzansky LD, 2016. Dispositional optimism and incidence of cognitive impairment in older adults. Psychosom. Med 78 (7), 819–828. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnois CE, Ifatunji Mosi A., 2011. Gendered measures, gendered models: toward an intersectional analysis of interpersonal racial discrimination. Ethn. Racial Stud 34 (6), 1006–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell Jules P., Hall Sadiki, Taliaferro James, 2003. Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: an assessment of the evidence. Am. J. Publ. Health 93 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman LW, McIntyre RB, Abbey A, 2015. The bad taste of social ostracism: the effects of exclusion on the eating behaviors of African-American women. Psychol. Health 30 (5), 518–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headen Irene E., Davis Esa M., Mujahid Mahasin S., Abrams Barabara, 2012. Racial-ethnic differences in pregnancy-related weight. Adv. Nutr 3, 83–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE (Ed.), 1990. Black And White Racial Identity: Theory, Research, and Practice. Greenwood Press, p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Michael, Demo David H., 1989. Self-perceptions of black Americans: self-esteem and personal efficacy. Am. J. Sociol 95 (1), 132–159. [Google Scholar]

- James Sherman, 1994. John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Cult. Med. Psychiatr 18, 163–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardina Ashley, 2019. White Identity Politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Bhatta TR, Kahana B, Lekhak N, 2021. Loving Others: The Impact of Compassionate Love on Later-Life Psychological Well-being. J. Gerontol.: Ser. B 76 (2), 391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman EA, Crowell SE, 2018. Biological and Behavioral Mechanisms of Identity Pathology Development: An Integrative Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol 22 (3), 245–263. 10.1037/gpr0000138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh PS, Signal TD, Taylor N, 2013. The dark triad and animal cruelty: dark personalities, dark attitudes, and dark behaviors. Pers. Indiv. Differ 55 (6), 666–670. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi Ichiro, Daniels N, Robinson D, 2005. Health disparities by race and class: why both matter. Health Aff. 24 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendi Ibrahim, 2016. Stamped from the Beginning: the Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. Nation Books, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger Nancy, 1990. Racial and gender discrimination: risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc. Sci. Med 30, 1273–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger Nancy, 2014. Discrimination and health inequities. Int. J. Health Sci. Res 44 (4), 643–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsman Jonathan W., Plant Ashby E., Deska Jason C., 2016. White ≠ poor: whites distance, derogate, and deny low-status ingroup members. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull 42 (2), 230–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S, 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Leach Colin W., et al. , 2008. Group-level self-definition and self-investment: a hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 95 (1), 144–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J, Romanski L, Xagoraris A, 1991. Indelibility of subcortical emotional memories. J. Cognit. Neurosci 1, 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV, Schroevers MJ, 2018. Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well-being. Mindfulness 9 (1), 325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Wurf E, 1987. The dynamic self-concept: a social psychological perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol 38 (1), 299–337. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot Michael, Allen Jessica, 2014. Social Determinants of Health Equity. Am. J. Public Health 104 (Suppl4), S517–S519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattina Gabriella F., Van Lieshout Ryan J., Steiner Meir, 2019. Inflammation, depression and cardiovascular disease in women: the role of the immune system across critical reproductive events. Therapeutic Adv. Cardiovascular 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen Bruce, 2000. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 22 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzl Jonathan, 2003. ‘Mother’s Little Helper’: The Crisis of Psychoanalysis and the Miltown Resolution. Gend. Hist 15 (2), 228–255. [Google Scholar]

- Metzl Jonathan, 2009. The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease. Beacon Press, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Metzl Jonathan M., 2019. Dying of Whiteness. Basic Books, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, et al. , 2011. Association between depression and inflammation – differences by race and sex: the META-Health study. Psychosom. Med 73 (6), 462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers LJ, Speight SL, Highlen PS, Cox CI, Reynolds AL, Adams EM, Hanley CP, 1991. Identity development and worldview: toward an optimal conceptualization. J. Counsel. Dev 70 (1), 54–63. 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb01561.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Rivas-Drake D, Umana-Taylor AJ, 2012. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Dev. Perspectives 6, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C, 1999. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 77 (5), 1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe John L., et al. , 2015. Men, masculinities, and murder-suicide. Am. J. Men’s Health 9 (6), 473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P, 2010. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav 51, S28–S40. Supp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratto Felicia, Jim Sidanius, Stallworth LM, Malle BF, 1994. Social dominance orientation: a personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 67 (4), 741–763. [Google Scholar]

- Quillian Lincoln, 2008. Does unconscious racism exist? Soc. Psychol. Q 71 (1), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AL, Pope RL, 1991. The complexities of diversity: exploring multiple oppression. J. Cousel. Dev 70 (1), 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Andrea J., Roberts Robert E., 2003. The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol 3 (4). [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, 2015. Which firms profit most from America’s health-care system? Economist. https://www.economist.com/business/2018/03/15/which-firms-profit-most-from-americas-health-care-system. (Accessed 16 October 2019). Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Sharon, 2017. Commentary: on the application of potential outcomes-based methods to questions in social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol 52, 139–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra F, 2016. The emergence of geroscience as an interdisciplinary approach to the enhancement of health span and life span. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives Med 6 (4), a025163. 10.1101/cshperspect.a025163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich George M., Irwin Michael R., 2014. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull 140 (3), 774–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart Richman Laura, Jonassaint Charles, 2008. The effects of race-related stress on cortisol reactivity in the laboratory: implications of the Duke Lacrosse scandal. Ann. Behav. Med 35 (1), 105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley Audrey, 2007. Race in North America: Origins and Evolution of a Worldview, third ed. Westview Press, Boulder, CO. [Google Scholar]

- St. Jean Yanick, Feagin Joe R., 2015. Double Burden: Black Women and Everyday Racism. Routledge, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Steele Claude, Spencer Steven J., Aronson Joshua, 2002. Contending with group image: the psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol 34, 379–440. [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A, 2018. Psychological distress, self-beliefs, and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Alzheim. Dis 65 (3), 1041–1050. 10.3233/JAD-180119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC, 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychol. Intergroup Relation 5, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Yi-Yuan, Holzel Birtta K., Posner Michael I., 2015. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16, 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B, 1994. Food, bodies, and growing up female: childhood lessons about culture, race, and class. Feminist Perspectives on Eating Disorders 355–378. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR, 2003. Status variations in stress exposure: implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. J. Health Soc. Behav 44 (4), 488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk Bessel, 2005. Developmental trauma disorder. Psychiatr. Ann 35 (5), 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk Bessel, 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Viana Mafalda, et al. , 2014. Assembling evidence for identifying reservoirs of infection. Trends Ecol. Evol 29 (5), 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JB, Gartner DR, Keyes KM, Fliss MD, McClure ES, Robinson WR, 2019. How do we assess a racial disparity in health? Distribution, interaction, and interpretation in epidemiological studies. Ann. Epidemiol 29, 1–7. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.09.007. Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R., Collins C, 2001. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Publ. Health Rep 116 (5), 404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombe Cheryl, 2010. Superwoman Schema: african American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual. Health Res 20 (5), 668–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright L, Simpson W, Van Lieshout RJ, Steiner M, 2014. Depression and cardiovascular disease in women: is there a common immunological basis? A theoretical synthesis. Therapeutic Adv. Cardiovascular 8 (2), 56–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Glen L., Doraiswamy P. Murali, 2009. Does meditation enhance cognition and brain plasticity? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1172, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip Tiffany, 2018. Ethnic/racial identity—a double-edged sword? Associations with discrimination and psychological outcomes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 27 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.