ABSTRACT

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of influenza A virus (IAV) is crucial for identifying diverse subtypes and newly evolved variants and for selecting vaccine strains. In developing countries, where facilities are often inadequate, WGS is challenging to perform using conventional next-generation sequencers. In this study, we established a culture-independent, high-throughput native barcode amplicon sequencing workflow that can sequence all influenza subtypes directly from a clinical specimen. All segments of IAV in 19 clinical specimens, irrespective of their subtypes, were amplified simultaneously using a two-step reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) system. First, the library was prepared using the ligation sequencing kit, barcoded individually using the native barcodes, and sequenced on the MinION MK 1C platform with real-time base-calling. Then, subsequent data analyses were performed with the appropriate tools. WGS of 19 IAV-positive clinical samples was carried out successfully with 100% coverage and 3,975-fold mean coverage for all segments. This easy-to-install and low-cost capacity-building protocol took only 24 h complete from extracting RNA to obtaining finished sequences. Overall, we developed a high-throughput portable sequencing workflow ideal for resource-limited clinical settings, aiding in real-time surveillance, outbreak investigation, and the detection of emerging viruses and genetic reassortment events. However, further evaluation is required to compare its accuracy with other high-throughput sequencing technologies to validate the widespread application of these findings, including WGS from environmental samples.

IMPORTANCE The Nanopore MinION-based influenza sequencing approach we are proposing makes it possible to sequence the influenza A virus, irrespective of its diverse serotypes, directly from clinical and environmental swab samples, so that we are not limited to virus culture. This third-generation, portable, multiplexing, and real-time sequencing strategy is highly convenient for local sequencing, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Bangladesh. Furthermore, the cost-efficient sequencing method could provide new opportunities to respond to the early phase of an influenza pandemic and enable the timely detection of the emerging subtypes in clinical samples. Here, we meticulously described the entire process that might help the researcher who will follow this methodology in the future. Our findings suggest that this proposed method is ideal for clinical and academic settings and will aid in real-time surveillance and in the detection of potential outbreak agents and newly evolved viruses.

KEYWORDS: influenza, clinical specimen, whole genome, MinION, high throughput

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A is an orthomyxovirus with an approximately 13.6-kb eight-segmented RNA genome. Globally, an estimated 291,243 to 645,832 seasonal influenza-associated respiratory deaths occur annually (1). The burden of disease disproportionately affects people in low- and middle-income settings. In the case of avian influenza, a total of 1,063 H5N1 outbreaks in poultry and wild birds have been reported to the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) by South Asian countries up to June 2019. In Bangladesh, the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) (H5N1) virus became enzootic in domestic poultry, with 561 animal outbreaks reported from February 2007 to December 2018 (2).

Currently, influenza A viruses (IAVs) are investigated based on detecting viral antigens or reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) amplification of viral nucleic acids derived from respiratory samples (3). However, both techniques can identify only the presence of the virus, and it is challenging to unveil all its subtypes (16 hemagglutinins [HAs] and 9 neuraminidases [NAs]). Moreover, these traditional methods are time-consuming and costly when applied to detect all HA and NA subtypes. Furthermore, genome sequencing of the virus is indispensable, especially in surveillance and outbreak investigation, for identifying the emergence of novel strains (4), improving the prediction of potential epidemics and pandemics (5), and selecting vaccine strains (6).

Whole-genome sequencing of IAV is challenging due to (i) segmented RNA genomes (8 segments, namely, PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M, and NS), (ii) various subtypes of IAV circulating among wild birds and poultry throughout the world, (iii) frequent reassortment events among different influenza subtypes, and (iv) substantial genetic variation from clade to clade and lineage to lineage (7–9).

Several Sanger-based sequencing strategies for influenza whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have been developed. Such methods use amplicon sequencing; some strategies use one pair of primers to amplify all viral RNAs (vRNAs) in a single multiplex PCR (10, 11), and some use segment-specific primer pairs (12, 13). This conventional sequencing system has served molecular biology well for almost 4 decades (14) and provides a tool for surveilling the highly dynamic genomes of influenza viruses (15). However, the tool is labor intensive, slow, unable to be multiplexed, and expensive when the entire genome of a virus or large numbers of samples need to be sequenced.

Frequent reassortment events and the substantial genomic diversity of influenza viruses demonstrate the inevitability of needing fast and accurate WGS. Lately, second-generation sequencing technologies, such as the widely used Illumina (16, 17), Roche 454 pyrosequencing (18), Life Technologies Ion Torrent (19, 20), and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) (21) instruments, have contributed significantly to providing WGS data for IAV. However, there are difficulties in using all of these NGS platforms for influenza whole-genome sequencing, especially in countries like Bangladesh, where facilities are inadequate. Besides, these platforms require specialized instrumentation and reagents, funds, time, and extensive protocols (22, 23).

To generate influenza virus whole-genome sequences irrespective of their subtypes, the proposed workflow with the application of the new Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION instrument can address these challenges. ONT has developed a platform that offers “third-generation,” portable, real-time sequencing, and multiplex barcoding possibilities to generate long-read single-molecule sequence data for various viruses (24–27). To date, several Nanopore sequencing methods have been developed for influenza virus WGS, as follows: direct RNA sequencing from the cultured virus (26), PCR amplicon sequencing (20, 28, 29), and the metagenomics influenza sequencing platform (30).

Here, we aimed to develop a high-throughput Nanopore MinION sequencing workflow with native barcoding for screening diverse influenza A viruses directly from clinical samples. This low-cost multiplexed method could provide new opportunities to respond to the early phase of an influenza pandemic and detect emerging subtypes in clinical samples.

RESULTS

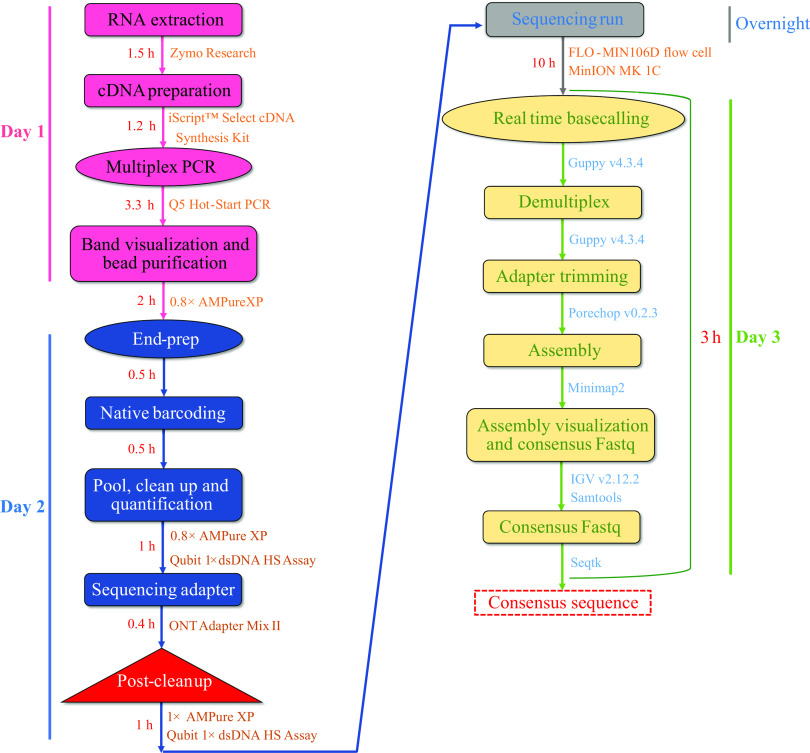

Initially, we tried one-step RT-PCR to amplify all influenza vRNAs, but no desired bands were found on agarose gel electrophoresis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Later, we followed a two-step PCR system. Our two-step PCR system successfully amplified all eight segments of the influenza A viral genome from each clinical swab sample, irrespective of its subtypes and lineages. Overall, starting from RNA to the final consensus FASTA, it took around 24 h to achieve 19 complete genomes with 100% coverage (Fig. 1). The sequencing run was performed in a new flow cell with 1,400 pores available. In total, 1,415,255 quality-control (QC)-passed reads (5.3% of passed reads without barcode) were generated in the 10-h run with an average quality score of 11.15 (range, 8.2 to 16), leaving 1,340,244 reads to be analyzed. From the QC report, the average read length was 850 bp.

FIG 1.

MinION workflow of full-length influenza A genome sequencing. The total time is split into practical and passive time needed for each protocol step.

A total of 754,474 reads was mapped against the influenza A reference sequences; the mean read number was 39,708 (56.3% of all passed and demultiplexed reads), and the mean coverage for all segments was 3,975× (Table 1). The highest mean coverage was found for the NS segment (13,012×) and the lowest for the PA segment (595×) (Fig. 2). According to sequence analyses, both HA and NA genotypes (H5N1, H5N3, and H9N2) were detected among all the attempted influenza A viruses. In addition, internal segments were also successfully sequenced. Specimen metadata and segment-wise read coverage of the 19 IAVs are described in Table 2. Our protocol showed 100% specificity with the reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) regarding HA typing reports. In addition, we detected H5 predominant clade 2.3.2.1a; the globally concerning, newly detected H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b; and H9N2 lineage G1.

TABLE 1.

Results of whole-genome sequencing of influenza A virusa using the MinION sequencer

| Segment of influenza A virus | Gene length (bp) | Mean no. of mapped reads | Mean no. of mapped bases (bp) | Mean coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 2,341 | 2,057 | 1,767,182 | 734 |

| PB1 | 2,341 | 2,878 | 2,387,182 | 994 |

| PA | 2,233 | 1,171 | 1,370,047 | 595 |

| HA | 1,757 | 4,745 | 4,356,092 | 2,332 |

| NP | 1,565 | 3,732 | 5,316,706 | 3,219 |

| NA | 1,402 | 3,450 | 4,331,534 | 2,834 |

| MP | 1,027 | 8,545 | 8,337,859 | 8,080 |

| NS | 865 | 13,130 | 11,278,779 | 13,012 |

| Total | 13,531 | 39,708 | 39,145,381 | 3,975 |

n = 19.

FIG 2.

Coverage map for gene segments obtained in the Nanopore sequencing. The x axis shows the nucleotide position, and the y axis shows the depth of reads.

TABLE 2.

Specimen metadata and segment-wise read coverage generated from influenza WGS in Nanopore MinION platform

| Specimen identity | Species | Specimen typea | MP gene CT value | Subtype CTvalues | RT-qPCR subtype | Sequence subtype | Clade/lineage | Segment-wise read coverage of all specimens |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | PB1 | PA | HA | NP | NA | MP | NS | ||||||||

| 1 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 17.17 | 18.33 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 846 | 948 | 638 | 1,538 | 1,863 | 979 | 9,195 | 16,684 |

| 2 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 18.69 | 22.7 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 853 | 659 | 739 | 1,901 | 4,714 | 3,977 | 8,304 | 10,041 |

| 3 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 22.03 | 22.55 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 790 | 556 | 539 | 1,757 | 2,120 | 1,250 | 7,755 | 12,700 |

| 4 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 17.19 | 21.28 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 623 | 652 | 745 | 1,914 | 2,552 | 1,542 | 5,962 | 11,871 |

| 5 | Chicken | Feces | 14 | 17.83 | H9 | H9N2 | G1 | 787 | 1,021 | 558 | 7,372 | 5,806 | 5,769 | 9,150 | 20,888 |

| 6 | Waterfowl | CL swab | 15.7 | 22.81 | H5 | H5N3 | EA-nonGsGD | 1,218 | 2,068 | 946 | 6,594 | 3,457 | 5433 | 8,762 | 20,782 |

| 7 | Wild bird | OP swab | 19.77 | 23.26 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 246 | 580 | 210 | 472 | 1,360 | 1,964 | 6,278 | 10,122 |

| 8 | Wild bird | Tracheal swab | 20.47 | 25.62 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 425 | 376 | 548 | 168 | 1,133 | 881 | 4,006 | 7,015 |

| 9 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 19.45 | 22.37 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 430 | 473 | 568 | 685 | 1,214 | 1,340 | 4,892 | 9,581 |

| 10 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 21.69 | 21.76 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 288 | 636 | 162 | 263 | 390 | 775 | 2,099 | 3,893 |

| 11 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 18.33 | 20.35 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 151 | 151 | 170 | 170 | 644 | 585 | 1,281 | 1,937 |

| 12 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 18.62 | 20.97 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 486 | 888 | 247 | 2,078 | 3,158 | 1,767 | 13,162 | 18,086 |

| 13 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 22.1 | 24.32 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 399 | 463 | 450 | 417 | 947 | 1,367 | 3,299 | 4,861 |

| 14 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 30.91 | 32.89 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 13 | 37 | 32 | 178 | 305 | 186 | 1,414 | 1,293 |

| 15 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 20.58 | 21.11 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 77 | 133 | 98 | 270 | 456 | 398 | 2,030 | 3,614 |

| 16 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 18.46 | 20.74 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 4,946 | 7,569 | 3,708 | 12,508 | 19,253 | 16,327 | 40,674 | 56,563 |

| 17 | Wild bird | OP+CL swab | 16.36 | 19.09 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 902 | 1238 | 423 | 5043 | 9,662 | 8,098 | 19,648 | 28,416 |

| 18 | Mammal | OP+CL swab | 23.26 | 31.9 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.2.1a | 251 | 326 | 315 | 789 | 1,321 | 867 | 3,538 | 5,795 |

| 19 | Waterfowl | CL swab | 20.52 | 24.71 | H5 | H5N1 | 2.3.4.4b | 213 | 115 | 203 | 196 | 800 | 348 | 2,078 | 3,086 |

| 734b | 994b | 595b | 2,332b | 3,219b | 2,834b | 8,080b | 13,012b | ||||||||

OP, oropharyngeal; CL, cloacal.

Mean coverage.

DISCUSSION

Currently, avian influenza surveillance has continued for samples from Galliformes, Anseriformes, Columbea, live-bird markets, wild birds, migratory birds, and the environment. We screen avian respiratory specimens and environmental swabs for common avian influenza A subtypes, such as H5, H7, and H9. We also investigate influenza outbreaks. Unfortunately, many influenza A virus-positive specimens remained constantly unsubtyped by the real-time RT-PCR protocols recommended by the CDC (31). Besides, the whole-genome sequencing facility in Bangladesh is inadequate. Sanger sequencing is performed for viral screening but is unable to detect diverse influenza A subtypes. Although this method has been used as a standard reference for almost 4 decades, applying the method for unveiling known or unknown HA1-HA16 and NA1-NA9 subtypes is not always economical in many cases, particularly when the subtype information is unknown. It requires multiple PCR attempts to amplify unknown influenza subtypes in such cases. In addition, it gets very challenging when there is a case of coinfection with other subtypes in the same sample. Besides, as we described above, this method cannot multiplex and is expensive when the entire genome of a virus or large numbers of samples need to be sequenced. Furthermore, there is a gradual shift from this technique to using newer technologies, specifically high-throughput sequencing methods. Therefore, developing a high-throughput sequencing platform was essential for generating full-length influenza sequences, determining circulating subtypes, and performing molecular characterization of the virus.

Initially, we tried a Sanger-based HA and NA subtyping strategy, but the result needed to be better (32). In addition, NA typing is also essential to detect emerging subtypes, like H5N6 and H5N8, which are detected in humans (33, 34). As a result, we were eager to identify both the HA and NA subtypes, which remained untyped in targeted RT-qPCR. Furthermore, we aimed to perform WGS of known avian influenza viruses to identify the evolution of new emergent clades.

The low abundance of viruses is often observed in the clinical samples (28) because (i) virus abundance depends on the disease severity and stage of infection and (ii) host DNA is abundant in the sample. Virus culture could be applied to grow influenza viruses before further genetic analysis; however, some highly pathogenic subtypes require biosafety level 3 laboratory facilities to culture them, which are often unavailable or subject to increased cost. Instead, we deployed an extraction strategy that included DNase I enzyme treatment, which usually degrades host and bacterial DNA in the sample during the RNA extraction procedure. In addition, amplicon sequencing (used here) can solve the low abundance problems by amplifying target influenza segments via the efficient two-step multiplex PCR system. Another concerning issue is PCR-generated errors; amplicons may contain errors introduced by the polymerase enzyme (35). However, we used Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (~280 times higher fidelity than Taq polymerase), which results in ultralow error rates.

Furthermore, the DNA fragmentation step (required for the Illumina MiSeq platform to generate short reads up to 600 bp) and high-cost devices are unnecessary when using the MinION sequencer. The Nanopore platform can sequence over 100 kb of long-read data (where influenza segment size ranges between 890 bp and 2,341 bp), which is another advantageous characteristic (36).

PCR amplicon Nanopore sequencing approaches have been described previously for IAV sequencing (20, 28, 29). However, methods were portrayed in different strategies (rapid barcoding or PCR barcoding) than our approach or the methodology and data analysis sections needed to be sufficiently stated. For example, one protocol plotted the sequencing of only one genome from a cultured specimen, which is difficult to follow in the case of multiplexing (28). Another approach described was the PCR barcoding strategy, which required multiple sequencing runs to get sufficient data for sequencing only human IAV and did not test nonhuman samples (29). Therefore, the abovementioned amplicon-based methods might be challenging to adopt in the new laboratory, where facilities are limited. However, in our meticulously described methodology, we used a native barcoding protocol, which is advantageous due to the following reasons: (i) the native barcoding protocol is a relatively quick way to multiplex without using additional barcode PCR, (ii) we introduced a two-step PCR strategy to amplify all IAV segments sufficiently, and (iii) so far it is a high-throughput, culture-independent, and cost-effective strategy.

Considering all these advantages, we can obtain whole-genome sequences and identify diverse virus subtypes by implementing our proposed high-throughput MinION sequencing protocol. This sequencing strategy can be performed in the field and clinical setting. Although for the methodology set we sequence 19 samples within 24 h, following this protocol, up to 96 samples can be sequenced, and subsequent data analysis can be done in a low-cost setting within the time frame. Previous Nanopore-based strategies showed sequencing procedures for a single or few genomes (6, 17). We calculated the cost of our native barcode-based sequencing protocol; it is estimated to be around $30 per sample without person-hour cost, which makes it a great cost-effective strategy. In addition, the native barcoding protocol is a relatively quick multiplexing method, avoiding the need for further PCR. Therefore, this method would potentially allow the investigation of the causative agent responsible for influenza outbreaks, the detection of diverse subtypes, and real-time monitoring of genetic reassortment and the emergence of new influenza virus strains.

This protocol successfully sequenced the complete genomes of more than 240 viruses (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), comprising diverse subtypes from human (H1N1pdm09, H3N2), avian, and environmental pools (H1N3, H2N1, H2N5, H2N9, H3N2, H3N3, H3N8, H4N6, H5N1, H5N3, H5Nx, H6N1, H6N9, H7N1, H7N2, H7N5, H8N3, H9N2, H9N5, H10N4, and H11N2), reported in our previous study (37). Surprisingly, we detected known H5N1 viruses in some samples that remained untyped by real-time PCR. Sequence analysis suggests that those strains had acquired mutations in the primer and/or probe binding sites, which could be the probable reason behind PCR negativity (38). Recently, we implemented this strategy for investigating influenza outbreaks among wild birds and poultry farms. We detected diverse clades and lineages across the species, which suggests its effectiveness in prompt response in outbreak investigation in a low-cost setting. Another advantage of this method is that it can sequence clinical samples directly, eliminating the need for virus culture. In addition, it can sequence IAV even at low concentrations (cycle threshold [CT] values of ≤32). For accurate surveillance and vaccine subpopulation selection, timely sequencing, deep sequencing, and a precise variant calling method with greater coverage depth are always required. The proposed protocol could be employed to attain these requirements.

To sum up, in influenza outbreak-prone countries like Bangladesh that have insufficient sequencing facilities, the proposed method could be the best option for influenza surveillance in humans, avians, and the environment in a low-cost setting. Particularly, viruses can be sequenced from diverse species found in different interfaces across the country, such as wild birds, the live bird market, migratory birds, chickens, ducks, poultry, and bat populations, to identify their various subtypes, to identify outbreak agents with pandemic potential, and finally select vaccine strains.

Here, we developed a high-throughput portable sequencing workflow using the MinION instrument in combination with a two-step PCR and the native barcode expansion kit (ONT). This cost-efficient and quick approach is ideal for both clinical and academic settings, aiding in real-time surveillance, the detection of potential outbreak agents and newly evolved viruses, and the investigation of genetic reassortment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens and RNA extraction.

Specimens used in this study were received from an influenza surveillance program, Avian Influenza Surveillance Bangladesh. We randomly selected 19 laboratory-confirmed influenza A virus-positive samples (subtypes influenza A/H5 and influenza A/H9) that were tested previously in the real-time RT-PCR assay described previously (39). We used the influenza virus cycle threshold (CT) to estimate the viral load in clinical samples. Diverse CT value ranges (14–30, 39) were used.

RNA was extracted from 200-μL swab specimens collected in viral transport medium (VTM) using the Direct-zol RNA miniprep plus kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted RNA did not require a separate DNase treatment as the extraction kit included an enzyme treatment during the extraction process. RNA was eluted in 60 μL of nuclease-free water.

cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification.

We followed a two-step RT-PCR system to amplify all of the influenza vRNAs using a single set of primers (MBTuni-12 [5′-ACGCGTGATCAGCAAAAGCAGG] and MBTuni-13 [5′-ACGCGTGATCAGTAGAAACAAGG]) (11) including a modified primer (MBTuni-12-mod [5′-ACGCGTGATCAGCGAAAGCAGG]). Bold in nucleotides A and G indicates the change made in which nucleotide in the modified primer (MBTuni-12-mod) compared to MBTuni-12 primer. cDNA synthesis was carried out using an iScript select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). Briefly, 10 μL of RNA preparation was mixed with 0.5 μM each of MBTuni-12, modified MBTuni-12, and MBTuni-13 primers; 4 μL of 5× iScript select reaction mix; 2 μL of GSP enhancer solution; 1 μL of RNase H+ Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase; and molecular-grade H2O to a volume of 20 μL. The reaction was carried out at 42°C for 60 min, followed by termination heating at 85°C for 5 min for enzyme inactivation.

Subsequently, all influenza segments were amplified simultaneously using Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, MA). Briefly, 2.5 μL of cDNA was mixed with 0.5 μM each of the MBTuni-12, modified MBTuni-12, and MBTuni-13 primers; 12.5 μL of Q5 hot-start high-fidelity 2× master mix; and 8 μL of molecular-grade H2O in a 25-μL reaction. The thermocycling parameters were as follows: 1 min at 98°C; then 5 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 45°C, and 3 min at 72°C; followed by 30 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 57°C, and 3 min at 72°C; with a final extension at 72°C for 3 min. After the amplification, PCR amplicons were visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by purification in a 0.8× AMPure XP bead (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, USA).

Nanopore library preparation and sequencing.

Nanopore sequencing libraries were prepared using the ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109) and barcoded individually using the native barcodes (native barcode expansion packs EXP-NBD104 and EXP-NBD114). The library preparation workflow is described in Fig. 1. In detail, purified multiplex amplicons were subjected to an end-prep reaction using the NEBNext ultra II end repair/dA-tailing Module (New England BioLabs, MA) with some modifications. About 2.5 μL of the individual multiplex amplicon was mixed with 1.75 μL of Ultra II end prep reaction buffer, 0.75 μL of Ultra II end prep enzyme mix, and 5 μL of H2O and then incubated at 20°C for 15 min and 65°C for 15 min in a thermocycler. End-prepped amplicons were taken forward to the native barcode ligation step; a total of 2.5 μL of amplicons was mixed with 1.25 μL of native barcode, 5.75 μL of blunt/TA ligase master mix, and 0.5 μL H2O and then incubated at room temperature for 20 min and at 65°C for 10 min. A batch of 19 barcoded amplicons was pooled, and a 0.8× AMPure XP bead (Beckman Coulter, CA) purification was carried out with two subsequent 250-μL short fragment buffer (SFB) washes and an 80% alcohol wash. The barcoded library was eluted in 30 μL elution buffer (EB) and quantified in the Qubit 1× double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) high-sensitivity assay kit (Invitrogen, OR) with a Qubit 4 fluorometer (Invitrogen). The barcoded library was subjected to ligation of the sequencing adapter; 10 μL of 5× NEBNext quick ligation reaction buffer, 5 μL of ONT Adapter Mix II (AMII), and 5 μL of Quick T4 DNA ligase were mixed with 30 μL of the barcoded library and then incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The library was purified by 1× AMPure XP bead with two subsequent 250-μL short fragment buffer (SFB) washes and eluted in 15 μL of EB buffer (ONT). The final library was quantified with the Qubit 1× dsDNA high-sensitivity assay kit (Invitrogen) and a Qubit 4 fluorometer (Invitrogen). Approximately 60 ng of the final library was loaded onto the FLO-MIN106D (R9.4.1) flow cell on an Oxford Nanopore MinION MK 1C platform for 10 h.

Nanopore MinION data analysis.

Raw fast5 signal data were base called by real-time base-calling with Guppy v.4.3.4 as released with MinKNOW software in the fast base-calling mode. Simultaneously, output fastq reads were demultiplexed, and reads were separated into individual barcodes by Guppy v.4.3.4. Demultiplexed reads were first quality checked in the EPI2ME WIMP workflow to ensure data integrity and sequencing quality. Then, barcode adapter trimming was performed using Porechop v.0.2.3. Subsequently, reads were mapped against the influenza A virus reference sequence database, including all 18 HAs, 11 NAs, and 6 other internal segments using pairwise aligner minimap2 with the “-ax map-ont” setting (40). Then, the SAMtools view command line was used to convert the sam data into bam formats, which were subsequently converted into sorted bam files with the “SAMtools sort” command. Sorted bam files were visualized in Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) v.2.12.2, and the quality and map coverage of the alignments were checked by the qualimap tool v.2.2.2. Variant calling under 10× read depth was filtered, and consensus fastq was generated by SAMtools and BCFtools (v.1.5.0) via the mpileup command (41). Finally, consensus fastq files were converted to consensus FASTA via the seqtk tool (42). The SAMtools depth command was used to obtain the coverage data to generate a coverage map for all segments. Subsequently, we plotted the coverage using the data visualization package ggplot2 in R programming. The consensus sequences generated by the reference-based assembly were BLAST searched to confirm genotypes and detect nucleotide identity. To identify variant information (clade or lineage), we used the H5 clade classification tool integrated with the Influenza Research Database (43). We also constructed a reference-based phylogenetic tree in the MEGA 7 tool for H5 and H9 viruses to confirm the detected clade or lineage (data not shown).

Influenza WGS cost calculation.

To provide a general overview of influenza whole-genome sequencing cost, we estimated the cost of our native barcode-based sequencing protocol, which may add value in setting up similar protocols in low-resource settings. We calculated the cost per sample without factoring in person-hour costs, which means we estimated only reagent and consumable costs. Some additional costs might be added to other consumables (e.g., tubes and PCR plates). A detail of the cost calculation is described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The calculation was performed for a batch of 24 samples, and the cost of the flow cell accounted for two batches per flow cell.

Ethical approval.

The Research Review Committee (RRC) and Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of ICDDR,B reviewed and approved this study under protocol no. PR-20101. Ethical approval was also obtained from the ethics committee of Chattogram Veterinary and Animal Science University (CVASU) bearing the number CVASU/Dir(R&E) EC/2019/126(1).

Data availability.

The data from this study can be found at NCBI under the BioProject accession number PRJNA946347. The raw fastq reads have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the accession numbers SRR23908962 to SRR23908980. The code for the influenza genome assembly can be found online at https://github.com/joynobPuspo/Influenza_pipeline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded this research protocol.

ICDDR,B acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of the CDC to its research efforts. ICDDR,B is also grateful to the government Republic of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom for providing core/unrestricted support.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

[This article was published on 22 May 2023 with Ariful Islam’s name missing from the byline and with information missing from the ethical approval statement. The byline and the statement were updated in the current version, posted on 30 May 2023.]

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Enayet Hossain, Email: enayet.hossain@icddrb.org.

Day-Yu Chao, National Chung Hsing University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, Wu P, Kyncl J, Ang LW, Park M, Redlberger-Fritz M, Yu H, Espenhain L, Krishnan A, Emukule G, van Asten L, Pereira da Silva S, Aungkulanon S, Buchholz U, Widdowson M-A, Bresee JS, Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network . 2018. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 391:1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowdhury S, Hossain ME, Ghosh PK, Ghosh S, Hossain MB, Beard C, Rahman M, Rahman MZ. 2019. The pattern of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 outbreaks in South Asia. Trop Med Infect Dis 4:138. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4040138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito Y. 2018. Clinical diagnosis of influenza, p 23–31. In Influenza virus. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houlihan CF, Frampton D, Ferns RB, Raffle J, Grant P, Reidy M, Hail L, Thomson K, Mattes F, Kozlakidis Z, Pillay D, Hayward A, Nastouli E. 2018. Use of whole-genome sequencing in the investigation of a nosocomial influenza virus outbreak. J Infect Dis 218:1485–1489. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy S, Hartley J, Dunn H, Williams R, Williams CA, Breuer J. 2019. Whole-genome sequencing provides data for stratifying infection prevention and control management of nosocomial influenza A. Clin Infect Dis 69:1649–1656. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai K, Tamura K, Tanigaki T, Takizawa M, Nakayama E, Taniguchi T, Okamoto M, Nishiyama Y, Tarumoto N, Mitsutake K, Murakami T, Maesaki S, Maeda T. 2018. Whole genome sequencing of influenza A and B viruses with the MinION sequencer in the clinical setting: a pilot study. Front Microbiol 9:2748. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen B, Munster VJ, Wallensten A, Waldenström J, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. 2006. Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds. Science 312:384–388. doi: 10.1126/science.1122438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou NN, Senne DA, Landgraf JS, Swenson SL, Erickson G, Rossow K, Liu L, Yoon K-j, Krauss S, Webster RG. 1999. Genetic reassortment of avian, swine, and human influenza A viruses in American pigs. J Virol 73:8851–8856. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.10.8851-8856.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batty EM, Wong THN, Trebes A, Argoud K, Attar M, Buck D, Ip CLC, Golubchik T, Cule M, Bowden R, Manganis C, Klenerman P, Barnes E, Walker AS, Wyllie DH, Wilson DJ, Dingle KE, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Piazza P. 2013. A modified RNA-Seq approach for whole genome sequencing of RNA viruses from faecal and blood samples. PLoS One 8:e66129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng Y-M, Spirason N, Iannello P, Jelley L, Lau H, Barr IG. 2015. A simplified Sanger sequencing method for full genome sequencing of multiple subtypes of human influenza A viruses. J Clin Virol 68:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou B, Donnelly ME, Scholes DT, St George K, Hatta M, Kawaoka Y, Wentworth DE. 2009. Single-reaction genomic amplification accelerates sequencing and vaccine production for classical and Swine origin human influenza a viruses. J Virol 83:10309–10313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan C-H, Lin K-L, Chan Y, Wang Y-L, Chi Y-T, Tu H-L, Shieh H-K, Liu W-T. 2006. Amplification of the entire genome of influenza A virus H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods 136:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, Webster R, Perez D. 2001. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch Virol 146:2275–2289. doi: 10.1007/s007050170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGinn S, Gut IG. 2013. DNA sequencing–spanning the generations. N Biotechnol 30:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghedin E, Sengamalay NA, Shumway M, Zaborsky J, Feldblyum T, Subbu V, Spiro DJ, Sitz J, Koo H, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Tatusova T, Bao Y, St George K, Taylor J, Lipman DJ, Fraser CM, Taubenberger JK, Salzberg SL. 2005. Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution. Nature 437:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutvisuttinunt W, Chinnawirotpisan P, Simasathien S, Shrestha SK, Yoon I-K, Klungthong C, Fernandez S. 2013. Simultaneous and complete genome sequencing of influenza A and B with high coverage by Illumina MiSeq Platform. J Virol Methods 193:394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee D-H. 2020. Complete genome sequencing of influenza A viruses using next-generation sequencing, p 69–79. In Animal influenza virus. Springer, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng Y-M, Caldwell N, Barr IG. 2011. Rapid detection and subtyping of human influenza A viruses and reassortants by pyrosequencing. PLoS One 6:e23400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van den Hoecke S, Verhelst J, Vuylsteke M, Saelens X. 2015. Analysis of the genetic diversity of influenza A viruses using next-generation DNA sequencing. BMC Genomics 16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1284-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King J, Harder T, Beer M, Pohlmann A. 2020. Rapid multiplex MinION nanopore sequencing workflow for Influenza A viruses. BMC Infect Dis 20:648. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05367-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell AB, Elshina E, Kowalsky JR, Te Velthuis AJ, Bloom JD. 2019. Single-cell virus sequencing of influenza infections that trigger innate immunity. J Virol 93:e00500-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00500-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glenn TC. 2011. Field guide to next-generation DNA sequencers. Mol Ecol Resour 11:759–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quail MA, Smith M, Coupland P, Otto TD, Harris SR, Connor TR, Bertoni A, Swerdlow HP, Gu Y. 2012. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genomics 13:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kafetzopoulou LE, Efthymiadis K, Lewandowski K, Crook A, Carter D, Osborne J, Aarons E, Hewson R, Hiscox JA, Carroll MW, Vipond R, Pullan ST. 2018. Assessment of metagenomic Nanopore and Illumina sequencing for recovering whole genome sequences of chikungunya and dengue viruses directly from clinical samples. Euro Surveill 23:1800228. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.50.1800228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNaughton AL, Roberts HE, Bonsall D, de Cesare M, Mokaya J, Lumley SF, Golubchik T, Piazza P, Martin JB, de Lara C, Brown A, Ansari MA, Bowden R, Barnes E, Matthews PC. 2019. Illumina and Nanopore methods for whole genome sequencing of hepatitis B virus (HBV). Sci Rep 9:7081. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller MW, Rambo-Martin BL, Wilson MM, Ridenour CA, Shepard SS, Stark TJ, Neuhaus EB, Dugan VG, Wentworth DE, Barnes JR. 2018. Direct RNA sequencing of the coding complete influenza A virus genome. Sci Rep 8:14408. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32615-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannan A, Mehedi HMH, Rob MA, Biswas SK, Sultana N, Biswas R, Hoque MM, Hossain MA, Das A, Chakma K, Salauddin A, Raza MT, Reza FH, Mahtab A, Miah M, Hasan R, Rahman M, Rahman MZ, Hossain ME. 2021. Genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 sublineage B.1.617.2 strains from 12 children in Chattogram, Bangladesh. Microbiol Resour Announc 10:e00912-21. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00912-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Moore NE, Deng Y-M, Eccles DA, Hall RJ. 2015. MinION Nanopore sequencing of an influenza genome. Front Microbiol 6:766. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yip CC-Y, Chan W-M, Ip JD, Seng CW-M, Leung K-H, Poon RW-S, Ng AC-K, Wu W-L, Zhao H, Chan K-H, Siu GK-H, Ng TT-L, Cheng VC-C, Kok K-H, Yuen K-Y, To KK-W. 2020. Nanopore sequencing reveals novel targets for detection and surveillance of human and avian influenza A viruses. J Clin Microbiol 58:e02127-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02127-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewandowski K, Xu Y, Pullan ST, Lumley SF, Foster D, Sanderson N, Vaughan A, Morgan M, Bright N, Kavanagh J, Vipond R, Carroll M, Marriott AC, Gooch KE, Andersson M, Jeffery K, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Walker AS, Matthews PC. 2019. Metagenomic Nanopore sequencing of influenza virus direct from clinical respiratory samples. J Clin Microbiol 58:e00963-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00963-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shu B, Wu K-H, Emery S, Villanueva J, Johnson R, Guthrie E, Berman L, Warnes C, Barnes N, Klimov A, Lindstrom S. 2011. Design and performance of the CDC real-time reverse transcriptase PCR swine flu panel for detection of 2009 A (H1N1) pandemic influenza virus. J Clin Microbiol 49:2614–2619. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02636-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang H-K, Park J-H, Song M-S, Oh T-K, Kim S-Y, Kim C-J, Kim H-G, Sung M-H, Han H-S, Hahn Y-S. 2008. Development of multiplex RT-PCR assays for rapid detection and subtyping of influenza type A viruses from clinical specimens. J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:1164–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Fang Y, Qiu X, Yu X, Cheng S, Li N, Sun Z, Ni Z, Wang H. 2022. Human infection with avian-origin H5N6 influenza A virus after exposure to slaughtered poultry. Emerg Microbes Infect 11:807–810. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2048971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. 2021. Human infection with avian influenza A (H5N8)—the Russian Federation. https://web.archive.org/web/20210226125105/https://www.who.int/csr/don/26-feb-2021-influenza-a-russian-federation/en/. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- 35.Xiao X, Wu Z-C, Chou K-C. 2011. A multi-label classifier for predicting the subcellular localization of gram-negative bacterial proteins with both single and multiple sites. PLoS One 6:e20592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain M, Koren S, Miga KH, Quick J, Rand AC, Sasani TA, Tyson JR, Beggs AD, Dilthey AT, Fiddes IT, Malla S, Marriott H, Nieto T, O'Grady J, Olsen HE, Pedersen BS, Rhie A, Richardson H, Quinlan AR, Snutch TP, Tee L, Paten B, Phillippy AM, Simpson JT, Loman NJ, Loose M. 2018. Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads. Nat Biotechnol 36:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hossain ME, Miah M, Hasan R, Hasan MM, Ami JQ, Davis W, Chowdhury S, Rahman MZ. 2022. Detection of a novel highly pathogenic avian influenza (A/H5N1) virus subclade 2.3.4.4B in a duck in Bangladesh. Abstract ID: AOXI0330. Options XI for the control of influenza, Belfast, United Kingdom, 26–29 September.

- 38.Hasan R, Hossain ME, Miah M, Hasan MM, Rahman M, Rahman MZ. 2021. Identification of novel mutations in the N gene of SARS-CoV-2 that adversely affect the detection of the virus by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Microbiol Spectr 9:e00545-21. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00545-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. 2009. CDC protocol of real-time RT-PCR for swine influenza A(H1N1). https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/CDCRealtimeRTPCR_SwineH1Assay-2009_20090430.pdf. Accessed 24 October 2022.

- 40.Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34:3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM, Li H. 2021. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H. 2012. Seqtk. Toolkit for processing sequences in FASTA/Q formats. https://github.com/lh3/seqtk.

- 43.Zhang Y, Aevermann BD, Anderson TK, Burke DF, Dauphin G, Gu Z, He S, Kumar S, Larsen CN, Lee AJ, Li X, Macken C, Mahaffey C, Pickett BE, Reardon B, Smith T, Stewart L, Suloway C, Sun G, Tong L, Vincent AL, Walters B, Zaremba S, Zhao H, Zhou L, Zmasek C, Klem EB, Scheuermann RH. 2017. Influenza Research Database: an integrated bioinformatics resource for influenza virus research. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D466–D474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download spectrum.04946-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.3 MB (284.4KB, pdf)

Supplemental material. Download spectrum.04946-22-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.02 MB (19.2KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study can be found at NCBI under the BioProject accession number PRJNA946347. The raw fastq reads have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the accession numbers SRR23908962 to SRR23908980. The code for the influenza genome assembly can be found online at https://github.com/joynobPuspo/Influenza_pipeline.