Abstract

This paper attempts to discuss why the early intervention agenda based on the current convention of ‘ultra-high risk’ (UHR) or ‘clinical high risk’ (CHR) for ‘transition’ to psychosis framework has been destined to fall short of generating a measurable and economically feasible public health impact. To summarise: (1) the primary determinant of the ‘transition’ rate is not the predictive value of the UHR/CHR but the degree of the risk-enrichment; (2) even with a significant pre-test risk enrichment, the prognostic accuracy of the assessment tools in help-seeking population is mediocre, failing to meet the bare minimum thresholds; (3) therapeutic interventions arguably prolong the time-to-onset of psychotic symptoms instead of preventing ‘transition’, given that the UHR/CHR and ‘transition’ lie on the same unidimensional scale of positive psychotic symptoms; (4) meta-analytical evidence confirms that specific effective treatment for preventing ‘transition’ (the goal—primary outcome—of the UHR/CHR framework) is not available; (5) the UHR/CHR-‘transition’ is a precarious target for research given the unpredictability driven by the sampling strategies and the natural ebb and flow of psychotic symptoms within and between individuals, leading to false positives; (6) only a negligible portion of those who develop psychosis benefits from UHR/CHR services (see prevention paradox); (7) limited data on the cost-effectiveness of these services exist. Given the pitfalls of the narrow focus of the UHR/CHR framework, a broader prevention strategy embracing pluripotency of early psychopathology seems to serve as a better alternative. Nevertheless, there is a need for economic evaluation of these extended transdiagnostic early intervention programmes.

Keywords: adult psychiatry

‘What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.’

From the movie Cool Hand Luke, 1967

The motto is appealing: earlier the treatment; better the prognosis. Evidence indicates that early diagnosis and treatment lead to a significant reduction in mortality and morbidity in many medical conditions. It is also plausible to argue that outcome can be further improved if we identify asymptomatic at-risk individuals and prevent diseases even before symptoms become manifest. The idea of detecting diseases in the preclinical phase has led to efforts into screening programmes from diabetes to various cancer types; and early intervention programmes have become an integral component of modern healthcare. Following the trend in medicine, the concept of ‘ultra-high risk’ (UHR) or ‘clinical high risk’ (CHR) for ‘transition’ to psychosis spectrum disorder—‘a step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia’1—emerged about two decades ago.

It is nonsensical to dispute the admirable idea of offering early treatment for those help-seeking individuals with subtle psychotic symptoms, which are often accompanied by various other mental symptoms as well. However, as we previously discussed,2 the ambitious goal of early prediction and prevention of psychosis at risk stage is less tractable than usually acknowledged. Various critical conceptual issues of the UHR/CHR model—that used to be overlooked but now surfaced as data accumulate over time—significantly undermine its validity and clinical utility. In this brief commentary, we will attempt to address some of these issues.

What defines UHR/CHR and determines transition: the screening tools or the sampling methods?

Accumulating data have unveiled the major flaw of the UHR/CHR concept that has been critiqued over a decade:2 3 the primary determinant of the ‘transition’ rate is not the predictive value of the screening tool for the UHR/CHR but the degree of the risk-enrichment in a given sample. The ‘transition’ rates across samples vary as a function of sampling strategy and healthcare settings, such as the degree of service filters, the intensity of outreach campaigns, the rate of self-referrals and study exclusion/inclusion criteria. In contrast to ‘transition’ rates (40%) reported in early studies, recent meta-analyses consistently report less than half of these rates (15%)—a phenomenon that is explained with the ‘dilution’ effect due to the expansion of the UHR/CHR programmes, which has a wider outreach than previously.4 As a matter of fact, broader general population surveys show that the real annual ‘transition’ rate at the community level is even lower (1%–2%).5

What is the clinical utility and prognostic accuracy of UHR/CHR assessment tools?

As discussed, the clinical utility of UHR/CHR assessment tools primarily depend on the degree of progressive risk enrichment ensured by selective sampling and filtering at each help seeking attempt. Meta-analytical evidence shows that even with a significant pretest risk enrichment, the prognostic accuracy of these assessment tools in help-seeking population is mediocre, failing to meet the bare minimum thresholds,6 with positive likelihood ratios (LR) of 1.82 and 1.9 and negative LRs of 0.09 and 0.25 for the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndrome and the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental State.7 8

What is the cost-effectiveness of special services for UHR/CHR?

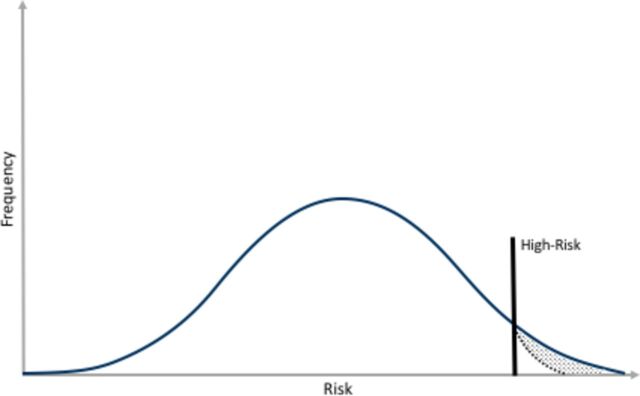

Given the scarcity of UHR/CHR cases and low ‘transition’ rates, it is highly questionable whether the targeted UHR/CHR early invention programmes may achieve any economically feasible public health success—see prevention paradox (figure 1). A recent retrospective investigation of electronic health records data from South East London showed that 16.3% of the patients presented to mental health services with a first-episode psychotic disorder (FEP) had a prior contact with local prodromal services,9 similar to recently disclosed data from Melbourne.10 However, only 4.1% met criteria for UHR/CHR and consequently ‘transitioned’, while the remaining 12.3% had already been diagnosed with FEP at initial contact with prodromal services.9 A similar trend, lending support to the prevention paradox, has also been shown in other cohorts across the world—only a negligible portion of those who develop FEP benefits from UHR/CHR services.2 Strikingly, two decades of UHR/CHR service research, although growing exponentially across the world, generated few data on the cost-effectiveness of these services, which were derived from underpowered studies with methodological limitations.11

Figure 1.

Prevention Paradox: the area between the straight and dashed curves represents the impact of the high-risk approach at the population level.

Is there an available therapeutic intervention that can prevent ‘transition’ to psychosis in UHR/CHR population?

Over half a century, the classical Wilson and Jungner criteria for disease screening have set the standards for appraising the need for population screening programmes in healthcare (box 1 adapted from the WHO Bulletin).12 The UHR/CHR programme, although an indicated prevention strategy, arguably meets some of these principles to a degree; yet it fails to meet the most essential criterion: availability of effective treatment for disease prevention. The most recent network meta-analysis of all randomised controlled trials of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for UHR/CHR showed no evidence for specific effect of any intervention, including needs-based treatment (also placebo), in preventing ‘transition’ to psychosis.13 The authors discussed that these recent findings, contradicting the early meta-analyses that reported a positive effect, are mainly driven by the non-significant findings from more recent trials. In this regard, it is also arguable that these therapeutic interventions are merely prolonging the time-to-onset of psychotic symptoms instead of preventing ‘transition’ to clinical psychosis spectrum disorder given that both binary categories of UHR/CHR and ‘transition’ are measured on the same unidimensional scale of positive symptoms (from mild to severe) rather than a multidimensional assessment of outcome and functioning as a more clinically relevant alternative.14

Box 1. The Wilson and Jungner screening criteria.

The condition is an important health problem.

An acceptable treatment for patients with the condition is available.

Facilities for diagnosis and treatment are available.

There is a recognisable latent or early symptomatic stage.

A suitable test or examination is available.

The test is acceptable to the population.

The natural history of the condition, from latent to manifest disease, is adequately understood.

There is an agreed policy on whom to treat as patients.

The cost of case-finding is economically balanced in relation to possible expenditure on medical care as a whole.

Case-finding is not a ‘once and for all’ but a continuing process.

Is the UHR/CHR binary ‘transition’ outcome a valid phenotype for research?

Research exploiting binary transition outcome appears like clockwork, with each study proposing a novel biological marker of transition, such as thalamic dysconnectivity15 or disorganised gyrification network properties as of lately16 and possibly many more in the future. Much of the appeal of the binary transition paradigm is in its capacity to simplify the interpretation of findings and provide a basis for translation to clinical practice. The rising trend of this research design is unusual considering that the psychiatry research is moving away from categorical diagnosis towards an all-encompassing psychosis-spectrum research framework.17

The most concerning issue is the unpredictability embedded in the UHR/CHR concept. First, transition is not a binary shift but a dimensional shift in positive psychotic symptoms per definition and therefore influenced by the natural ebb and flow of psychotic symptoms within and between individuals, leading to false positives.2 Second, it is highly unlikely the same study design would conclude the same finding across different clinical settings or time periods where transition rates vary dramatically depending on multiple factors as described previously.4 Given this unpredictability of transition rates that are primarily driven by heterogeneity in study sampling methods, it is highly questionable whether a novel biological marker of transition can be independently replicated in another study in another setting.

Conclusion

It is all too easy to stand by the status quo and champion the UHR/CHR concept given the virtue of a commitment to early intervention for young people at-risk and the enticing simplification of the UHR/CHR framework in clinical and research practice, but our decision-making should be guided by evidence—evidence that can come from nowhere but epidemiology and public health.

To give an example from medicine, there is a hot debate over the clinical utility of screening programmes. Even the standard screening programmes that have been part of routine clinical and public health practice over decades, such as diabetes mellitus and breast and prostate cancers, are under fire for failing to generate a significant improvement in key outcome measures, such as disease-specific and all-cause mortality.18 In this regard, we believe that the field, after two decades of clinical research, should at least be open for discussion of concerns over the UHR/CHR programme in the light of data. In fact, it is encouraging to see that even the prime movers of the traditional UHR/CHR paradigm move beyond a narrow framework and adopt a broader prevention strategy acknowledging pluripotency.10 Also, instead of the pragmatic surrogate outcome of ‘transition’, higher-level outcomes such as functioning and quality of life may serve as more clinically relevant and service-user-centred outcomes for measuring effectiveness of the early intervention programmes. Nevertheless, there remains a continuing need for rigorous economic evaluation of these extended transdiagnostic programmes.

Overall, we reiterate the fact that we are required to adhere to evidence-based mental healthcare standards in early intervention practice to make a measurable public health impact.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors wrote the paper. They contributed to the final version and have approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, et al. Prediction of psychosis. A step towards indicated prevention of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998;172:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Os J, Guloksuz S. A critique of the "ultra-high risk" and "transition" paradigm. World Psychiatry 2017;16:200–6. 10.1002/wps.20423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Os J, Delespaul P. Toward a world consensus on prevention of schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2005;7:53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fusar-Poli P, Schultze-Lutter F, Cappucciati M, et al. The dark side of the moon: meta-analytical impact of recruitment strategies on risk enrichment in the clinical high risk state for psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2016;42:732–43. 10.1093/schbul/sbv162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaymaz N, Drukker M, Lieb R, et al. Do subthreshold psychotic experiences predict clinical outcomes in unselected non-help-seeking population-based samples? A systematic review and meta-analysis, enriched with new results. Psychol Med 2012;42:2239–53. 10.1017/S0033291711002911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fusar-Poli P, Schultze-Lutter F. Predicting the onset of psychosis in patients at clinical high risk: practical guide to probabilistic prognostic reasoning. Evid Based Ment Health 2016;19:10–15. 10.1136/eb-2015-102295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oliver D, Kotlicka-Antczak M, Minichino A, et al. Meta-analytical prognostic accuracy of the Comprehensive Assessment of at Risk Mental States (CAARMS): The need for refined prediction. Eur Psychiatry 2018;49:62–8. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Rutigliano G, et al. At risk or not at risk? A meta-analysis of the prognostic accuracy of psychometric interviews for psychosis prediction. World Psychiatry 2015;14:322–32. 10.1002/wps.20250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ajnakina O, Morgan C, Gayer-Anderson C, et al. Only a small proportion of patients with first episode psychosis come via prodromal services: a retrospective survey of a large UK mental health programme. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:308. 10.1186/s12888-017-1468-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGorry PD, Hartmann JA, Spooner R, et al. Beyond the "at risk mental state" concept: transitioning to transdiagnostic psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2018;17:133–42. 10.1002/wps.20514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amos A. Assessing the cost of early intervention in psychosis: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2012;46:719–34. 10.1177/0004867412450470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson JMG, Jungner G. World Health Organization. Principles and practice of screening for disease, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davies C, Cipriani A, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Lack of evidence to favor specific preventive interventions in psychosis: a network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2018;17:196–209. 10.1002/wps.20526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hengartner MP, Heekeren K, Dvorsky D, et al. Course of psychotic symptoms, depression and global functioning in persons at clinical high risk of psychosis: Results of a longitudinal observation study over three years focusing on both converters and non-converters. Schizophr Res 2017;189:19–26. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anticevic A, Haut K, Murray JD, et al. Association of thalamic dysconnectivity and conversion to psychosis in youth and young adults at elevated clinical risk. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:882–91. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Das T, Borgwardt S, Hauke DJ, et al. Disorganized gyrification network properties during the transition to psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75:613. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guloksuz S, van Os J. The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum. Psychol Med 2018;48:229–44. 10.1017/S0033291717001775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saquib N, Saquib J, Ioannidis JP. Does screening for disease save lives in asymptomatic adults? Systematic review of meta-analyses and randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:264–77. 10.1093/ije/dyu140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]