Abstract

Bed rest is commonly used on medical and paediatric wards as part of nursing management of the physically compromised patient with severe anorexia nervosa. The aim of this study was to review the evidence base of bed rest as an intervention in the management of severe anorexia nervosa. We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL, HMIC, AMED, HBE, BNI and guidelines written in English until April 2018 using the following terms: bed rest and anorexia nervosa. After exclusion of duplicates, three guidelines and eight articles were included. The papers were methodologically heterogeneous, and therefore, quantitative summary was not possible. There have been no randomised controlled trials to compare the benefits and harms of bed rest as the focus of intervention in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Several papers showed that patients have a strong preference for less restrictive approaches. These are also less intensive in nursing time. Negative physical consequences were described in a number of studies: these included lower heart rate, impaired bone turn over and increased risk of infection. We found no evidence to support bed rest in hospital treatment of anorexia nervosa. The risks associated with bed rest are significant and include both physical and psychological harm, and these can be avoided by early mobilisation. Given the established complications of bed rest in other critically ill patient populations, it is difficult to recommend the enforcement of bed rest for patients with anorexia nervosa. Future research should focus on safe early mobilisation, which would reduce complications and improve patient satisfaction.

Keywords: eating disorders, adult psychiatry

Introduction

Bed rest has long been part of hospital treatment of severe anorexia nervosa.1 Historically, hospital treatment programmes were based on operant conditioning techniques,2 3 in which the patient would be placed on complete bed rest and allowed small privileges, such as going to the bathroom alone, as reward for eating and/or weight gain. These practices were discouraged by the first National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on eating disorders,4 and consequently this practice has become less frequently used in specialist eating disorder units in the UK. However, bed rest is still commonly used on medical and paediatric wards, and both the adult and Junior MARSIPAN guidelines5 6 recommend bed rest as part of nursing management of the physically compromised patient.

The current rationale for bed rest is to reduce the metabolic demand on a severely malnourished patient and to prevent risks associated with hyperactivity.5 7 One of the fatal cases reported in the adult MARSIPAN document was a ‘24-year-old female with a BMI 11 treated on a general medical ward, who prior to a planned move to an eating disorders unit exercised by standing and wiggling her toes and fingers for the whole weekend, day and night, in front of two special nurses, before collapsing and dying from hypoglycaemia on the Monday morning’. This death was attributed to excessive exercise, although the cause was hypoglycaemia, which was most likely to have been the result of underfeeding rather than hyperactivity.

More recently, there has been increasing awareness of the harm patients can suffer as a result of bed rest in hospitals.8 In the elderly, even a few days of bed rest can result in significant muscle atrophy and loss of mobility, which can be prevented by early mobilisation.9 ‘The dangers of going to bed’ were eloquently summarised in Asher’s paper in 1947,10 in which he described that bed rest has a significant impact on all systems. Negative consequences include increased risk of hypostatic pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, pressure sores, muscle loss and disuse osteoporosis, urinary infection, constipation and emotional distress. The use of bed rest in the management of eating disorders is likely to share the same risk, but the practice still continues in acute hospitals and some specialist units.11–14

A recent case in our own clinical practice brought this issue to the forefront of our attention. An adult patient with a BMI of 9 was put on bed rest in an acute hospital with the intention of reducing metabolic demands. She rapidly developed a cascade of complications, including chest infection needing intravenous antibiotic treatment and consequently developed Clostridium difficile infection, grade 3 pressure sores and severe muscular atrophy resulting in compromise in her breathing and requiring artificial ventilation. Although this patient has survived, she spent 4 months in intensive care. One could question whether the complications would have been prevented by allowing the patient to move, and this formed the basis of our interest in reviewing the evidence base supporting this practice in hospitals.

The objective of this study was to conduct a review of the literature on using bed rest as an intervention in the management of severe anorexia nervosa.

Methods

Given the limited literature on the topic, we had a broad approach to the literature search including all study designs. We searched NICE Healthcare Databases (https://hdas.nice.org.uk/), which include AMED, BNI CINAHL Embase, HBE, HMIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and PubMed, until 13 April 2018. In addition, we also searched English language guidelines relating to the treatment of anorexia nervosa.

Search terms included ‘anorexia nervosa’ and ‘bed rest’ in all fields in all databases. Secondary searches consisted of manually searching the reference lists of all identified articles. We also searched guidelines published in the English language: NICE,15 American Psychiatric Association (APA),16 Adult and Junior MARSIPAN guidance,5 6 and the Australian guidelines,17 for the term ‘bed rest’ both in the text and in the references.

Studies were included if they involved patients with anorexia nervosa (all diagnostic systems) and if the focus of the paper was bed rest. Papers not in the English language were excluded. We also excluded case reports and descriptive studies of individual programmes that did not include any outcome data. Original studies were assessed by two independent authors using ’Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation' (GRADE) as a reference guide.18 The following criteria were used as a starting point: randomised controlled trials (RCTs) without important limitations provide high-quality evidence and observational studies without special strengths or with important limitations provide very low-quality evidence. For each outcome, quality was assessed depending on five factors: limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias (data not shown but available by the authors).

Results

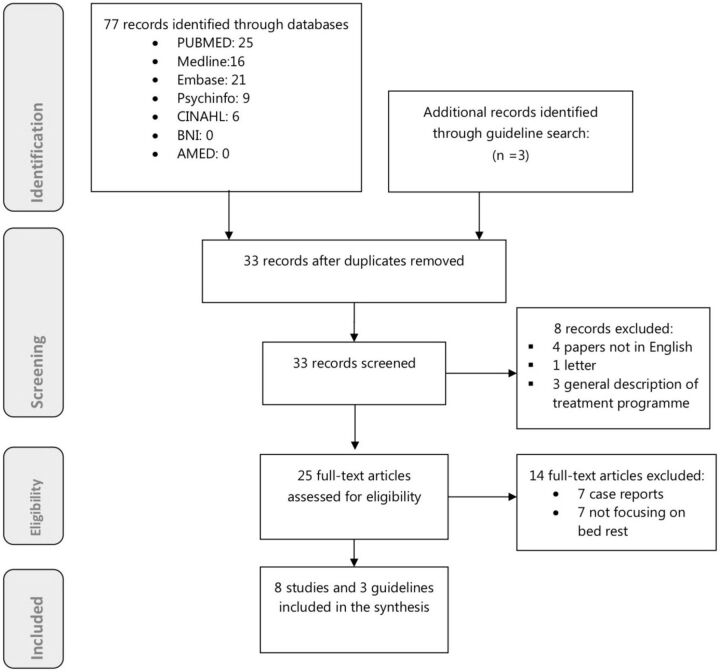

The electronic search produced a total of 77 references, with 33 remaining after excluding duplicates and including papers retrieved by the hand search (figure 1). Eight studies were removed after screening, and a further 14 full text papers were excluded at eligibility, so in the end, 11 articles were included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

International guidelines

The search yielded three guidelines including the term ‘bed rest’: APA and Adult and Junior MARSIPAN guidelines (table 1). Only the APA included literature references relating to the topic. The APA guidelines state ‘Most inpatient-based nutritional rehabilitation programs create a milieu that incorporates emotional nurturance and a combination of reinforcers that link exercise, bed rest, and privileges to target weights, desired behaviours, feedback concerning changes in weight, and other observable parameters (Recommended with moderate clinical confidence)… Some positive reinforcements (eg, privileges) and negative reinforcements (eg, required bed rest, exercise restrictions, restrictions of off-unit privileges) should be built into the program; negative reinforcements can then be reduced or terminated and positive reinforcements accelerated as target weights and other goals are achieved’.16 The rationale behind these programmes is operant conditioning theory, which historically dominated inpatient treatment,19 and there is no consideration of potential physical or psychological harm. There is still considerable variation between individual programmes, both nationally and internationally. Some are more restrictive, while others emphasise patient autonomy, and therefore the length of bed rest varies significantly. The 2012 update of the APA guidance does not include any further discussion of bed rest.20 This is due to lack of further trials on the topic, and hence no change was recommended.

Table 1.

Summary of included guidelines and studies

| Guidelines | |||||||

| Recommendations | |||||||

| APA 201016 | ‘Inpatient-based nutritional rehabilitation programs create a milieu that incorporates emotional nurturance and a combination of reinforcers that link exercise, bed rest, and privileges to target weights, desired behaviours, feedback concerning changes in weight, and other observable parameters (Recommended with moderate clinical confidence)’. | ||||||

| MARSIPAN5 | ‘Bed rest is required in view of the compromised physical state of the patient. Takes into account the management of some physical complications, such as deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and risk assessment for tissue viability’. | ||||||

| Junior MARSIPAN6 | Total bed rest is only if the young person is severely unwell (bradycardia <50, electrolyte abnormalities, increased corrected QT interval and low blood pressure) and states that ‘if the child is expected to bed rest, it is absolutely essential that a programme of therapeutic, distracting, low mentally effortful activity is provided. Enforced bed rest is extremely distressing for young people with anorexia nervosa unless they are robustly supported’. | ||||||

| Original research | |||||||

| Reviews | |||||||

| Achamrah et al 7 | Narrative review focusing on activity and exercise. The authors cautioned against conventional bed rest imposed on patients with anorexia nervosa as this is probably detrimental. | ||||||

| Comparative studies | |||||||

| Study | Design | Interventions | Comparison | Duration of bed rest (days) | Measurement | Results/recommendation | GRADE ratings |

| DiVasta et al 22 | Double blind RCT. | LMMS. | Placebo. | 5 | Bone turnover markers. | Brief, daily LMMS prevents a decline in bone turnover during 5-day bed rest in AN compared with placebo platform. | Moderate. |

| Touyz et al 21 | Comparison of two cohorts. | Lenient refeeding regime. | Strict operant conditioning refeeding programme. | Up to 42 | Weight gain. Patient cooperation. Staffing. |

No difference in weight gain. More acceptable to patients. Reduced staffing. |

Very low. |

| Observational studies | |||||||

| DiVasta et al 25 | Longitudinal observational study. | Bed rest and refeeding. | None. | Unclear. | 15-lead ECG, echocardiogram, Bruce protocol 21 min treadmill stress test and spinal bone mineral density measurement. | Exercise tolerance was normal by all measures. Sinus bradycardia. Left ventricular atrophy. |

Low. |

| DiVasta et al 24 | Observational study. | Bed rest and refeeding. | None. | 5 | Markers of bone formation (bone specific alkaline phosphatase), turnover (osteocalcin) and bone resorption (urinary N-telopeptides). | Limitation of physical activity during hospitalisation for patients with AN is associated with suppressed bone formation and resorption and an imbalance of bone turnover. | Low. |

| Kerem et al 26 | Retrospective cohort. | Bed rest and refeeding. | None. | 10 | Venous blood gases and pH. | Respiratory acidosis improves with bed rest and refeeding.* | Very low. |

| Surveys of patient views | |||||||

| Griffiths et al 27 | Inpatient survey. | Bed rest and refeeding. | None. | 20±27 | Opinion of patients. | All but one patient placed on bed rest found it unpleasant. | Very low. |

| Escobar-Koch et al 28 | Online survey. | NA | No. | NA | Qualitative study of patient’s perspective. | One negative comment about complete bed rest causing anxiety and bed sores. | Very low. |

LMMS, low-magnitude mechanical stimulation; RCT, randomised controlled trial. AN: anorexia nervosa

Both the Adult and Junior MARSIPAN guidelines mention bed rest, but these guidelines were based on consensus rather than a full review of the literature. The adult MARSIPAN guidelines state: ‘bed rest is required in view of the compromised physical state of patient’. They also take into account the management of some physical complications, such as deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and risk assessment for tissue viability. However, they do not refer to other complications, such as muscular atrophy or reduced bone turnover, or psychological consequences. There is no specific guidance as to the length of time bed rest should continue.

The Junior MARSIPAN guidelines recommend total bed rest only if the young person is severely unwell (bradycardia <50, electrolyte abnormalities, increased QTc and low blood pressure) and state that ‘if the child is expected to bed rest, it is absolutely essential that a programme of therapeutic, distracting, low mentally effortful activity is provided. Enforced bed rest is extremely distressing for young people with anorexia nervosa unless they are robustly supported’. The Junior MARSIPAN guidance only recommend for the ‘shortest period of time’ for those who show signs of cardiovascular compromise, with the primary rationale being to reduce psychological distress, rather than referring to potential physical complications.

Original research

The number of original publications has been surprisingly small, and the quality of the research has been generally low, consisting mainly of observational studies using convenience samples. The characteristics of the included papers are summarised in table 1.

Reviews

There have been no systematic reviews on this topic. One narrative review considered bed rest in the context of physical activity in anorexia nervosa.7 This review was limited by the small number studies published on bed rest. The authors cautioned against ‘conventional bed rest imposed on patients with anorexia nervosa’ as this is probably detrimental for a number of reasons, including the well-established risk to bone mineral density due to immobilisation, negative effects on psychological well-being and body composition.

Comparative studies

There have been no RCTs to compare the benefits and harms of bed rest as the focus of intervention in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. There was only one study comparing two groups of patients in the same hospital, but this was not a randomised trial. Touyz et al compared strict ad lenient operant conditioning regimes in 1984 using two cohorts21 (see online supplementary table). The strict bed rest programme included rewards for every 0.5 kg weight gain, while the lenient programme started with 1-week bed rest, followed by a contract with the patients that they were free to move as long as they gained 1.5 kg each week. They found that a lenient programme was more acceptable for patients and was less intensive in terms of nursing time, without any difference in weight gain during a 6-week period. Approximately 80% of the patients reached their target weight in both groups. However, the two groups were not identical, as the authors compared two different cohorts (presumably before and after service change, although this was not clear from the description in their paper). The measurements of ‘acceptability’ by patients and staff time were unclearly defined.

ebmental-2018-300064supp001.docx (22.6KB, docx)

Studies relating to physical health

One double-blind RCT evaluated low-magnitude mechanical stimulation to prevent decline in bone turnover during 5-day bed rest in a sample of 42 adolescents.22 This study showed that patients in the placebo arm had reduced serum markers of bone formation within 5 days of bed rest, while there was no deterioration in the intervention group. However, there was no comparison with free movement.

This trial was based on a previous observational study of patients with anorexia nervosa by the same research group that showed that bone turnover was impaired even after a 5-day bed rest. This was an important observation in an adolescent sample, as the majority of the literature regarding the impact of bed rest on bone health is concerned with older patient populations.23 The authors warned that ‘protocols prescribing strict bed rest may not be appropriate for protecting bone health for these patients’.24

Cardiovascular compromise is the main reason why bed rest is recommended in the Junior MARSIPAN guidelines. We only identified one paper exploring this issue in a sample of 38 adolescents and young adults.25 There was no comparison group. This study found that exercise tolerance test was normal by all measures using the 21 min Bruce protocol treadmill stress test, despite sinus bradycardia and mild reductions in left ventricle mass and left ventricle function, suggesting that cardiovascular exercise is safe in this patient population. However, the mean BMI in this group was 15.9 (range 12.1–19.9), which is less severe than that recommended by the MARSIPAN guidance at the point of bed rest as an intervention.

One study examined respiratory acidosis in a retrospective cohort of 45 adolescents26 and found that respiratory acidosis improves after 10 days with bed rest and refeeding. However, as there was no comparison group, it is unclear whether the improvement was due to refeeding rather than bed rest.

Patient surveys relating to psychological impact and ethical issues

Two surveys have examined patients’ perceptions of bed rest as part of treatment for anorexia nervosa. Griffiths et al 27 surveyed a sample of 48 inpatients to elicit their attitudes towards bed rest and found that most patients perceived bed rest negatively. Isolation and boredom were reported to be the main complaints, rather than the predicted perception of punishment or humiliation. Patients preferred more individualisation and distraction and less restriction. The authors suggested further studies investigating the psychological impact of bed rest, but there has been no further work that we can identify to date in this regard.

A qualitative, online survey, including 144 US and 150 UK adult ED service users, examined patients’ views about helpful and unhelpful interventions used by eating disorder services. Bed rest was identified by one patient as an unhelpful intervention, resulting in muscle wastage, bed sores and increasing anxiety.28 However, this was a mixed patient sample, and it is unknown how many of the responders were hospitalised.

Conclusions and clinical implications

We found no RCTs or previous systematic reviews comparing the physical and psychological benefits and harms of using bed rest or allowing the patient mobilise as part of hospital treatment of severe anorexia nervosa. The main limitation of our study is that the number of studies on this important topic has been surprisingly small, and the quality of the research has been generally low, mainly limited to cohort and observational studies. Potential bias included small sample sizes, multiple interventions and poorly defined outcomes in most studies. However, the search was comprehensive, and by having broad inclusion criteria, it is unlikely that any relevant studies were missed by our literature search. There were no studies demonstrating clear benefits of bed rest, either in terms of weight restoration or safety.

However, there is evidence of harm in this patient population, such as reduced bone turnover, even after a few days of bed rest, even in adolescents. This is consistent with findings in other patient groups.23 29 One RCT showed that low magnitude mechanical stimulation was effective in preventing impaired bone turnover. However, there are no studies comparing the effects of bed rest with mobilisation.

Qualitative work on patients’ perception has consistently shown that patients find bed rest unpleasant and unhelpful.21 27 28 This is also observed in clinical practice: patients who are prescribed bed rest often engage in battles with staff, requiring an increased level of nursing input, which increases healthcare costs and harms engagement with treatment.21 30

All NICE-approved psychological treatments emphasise the importance of patient choice and engagement.15 However, restriction of movement and exercise remains a common reason for using bed rest in hospitals, particularly in acute settings. This is still reflected in the MARSIPAN guidelines, although with specific reference to those who are most severely malnourished. The Adult MARSIPAN guidelines are mainly concerned with reducing hyperactivity and energy demands to achieve weight gain,5while the Junior MARSIPAN guidelines focus on cardiovascular compromise and only recommend bed rest under exceptional circumstances.6

There are no studies in the literature exploring the effectiveness of bed rest to reduce energy demands in severe malnutrition. Still, current practices are cautious both about the rate of refeeding and energy expenditure. For example, the MARSIPAN guidelines recommend initial refeeding at the rate of 5–10 kcal/kg, which may be less than 400 kcal/day for a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa. However, recent studies have shown that most patients tolerate a higher rate of refeeding without significant complications.31 32 It may therefore be more helpful to focus on increasing nutritional intake as opposed to attempting to restrict energy expenditure and movements.

With regard to cardiovascular compromise, research studies have shown that prolonged bed rest causes cardiac atrophy in healthy volunteers, which can be mitigated by exercise training.33 Orthostatic hypotension is often associated with severe malnutrition, and it may increase the risk of falls. Temporary use of wheelchairs may be justified as short-term measure if there is significant orthostatic hypotension as a short-term measure. However, it quickly resolves with refeeding, so restriction of movement can be kept to a minimum. Furthermore, enforcing bed rest against the patient’s will is difficult to implement, particularly if they are treated on a voluntary basis.

Although strict behavioural programmes have become less commonly used in specialised eating disorder units in the UK, the APA guidelines still retain elements of operant conditioning principles as part of inpatient-based nutritional rehabilitation programmes and include bed rest.16 Dalle Grave’s team in Garda, Italy, have shown that even the most severely ill patients can be managed without bed rest and allowed free movements.34 This should not be surprising, as the overwhelming majority of patients admitted to hospital are fully mobile before admission. This inpatient treatment programme is based on cognitive–behavioural therapy for eating disorders using a whole system, integrated approach, focusing on patient autonomy and evidence-based psychological treatment. Hyperactivity is addressed as part of the maintaining mechanisms in psychological treatment, using individual feedback by wearable technologies.34 35 This approach helps to engage the patient in behavioural change as part of their recovery, and the reduction of daily step count has been shown to help with treatment outcomes, including the resumption of menses.36

The research on bed rest in anorexia nervosa is limited; however, it is important to note that there has been an increasing awareness of the harms of bed rest in a number of patient populations, such as the critically ill.23 37 38 These include pressure sores, venous thrombosis, infection, muscle atrophy,23 39 suppressed bone formation and resorption and an imbalance of bone turnover. In a systematic review of bed rest in 15 different conditions, no outcomes improved and 9 worsened significantly, including acute low back pain, labour, proteinuric hypertension during pregnancy, myocardial infarction and acute infectious hepatitis.40 The authors concluded that we should not assume any efficacy for bed rest. Further studies were recommended to establish evidence for the benefit or harm of bed rest as a treatment, but eating disorders were not included. The recognition of potential harms, such as loss of mobility in the elderly has led to the recent #endpjparalysis campaign on hospital wards, encouraging early mobilisation, which has been taken up by the NHS.8 Perhaps we should also consider including patients with severe anorexia nervosa in this campaign. The potential benefits would include less distress for patients, better engagement with treatment and prevention of complications, including reduction of further muscular atrophy and bone mineral density.

In conclusion, there is no evidence to support the use of bed rest in severe anorexia nervosa. Given the risk of harm, both physical and psychological, the practice should only be used as an exception, rather than routine, and for the shortest time possible. Intensive nursing support of the severely ill patient should focus on engagement and ensuring adequate dietary intake, rather than enforcing bed rest. The metabolic demand with gentle activity can be safely managed by appropriate nutrition, and the risk of falls can be prevented by using alternative methods. Future research should focus on improving mobilisation safely, such as resistance exercise and using mobile technologies for monitoring and feedback.7 41

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Andrew Ayton for copyediting the text.

Footnotes

AI and AA contributed equally.

Contributors: AI and AA developed the research question and carried out the literature review. AI ad AA drafted the paper. DC helped revising the paper. All authors have agreed to the final version before submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Presented at: This work was presented as a poster at the 2nd Congress on Evidence Based Mental Health: from research to clinical practice Kavala, Greece, 28 June–1 July 2018.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Hall A. Treatment of anorexia nervosa. N Z Med J 1975;82:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garfinkel PE, Kline SA, Stancer HC. Treatment of anorexia nervosa using operant conditioning techniques. J Nerv Ment Dis 1973;157:428–33. 10.1097/00005053-197312000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Azerrad J, Stafford RL. Restoration of eating behavior in anorexia nervosa through operant conditioning and environmental manipulation. Behav Res Ther 1969;7:165–71. 10.1016/0005-7967(69)90028-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NICE. Eating disorders core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and related eating disorders. CG9. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Royal College of Psychiatrists. MARSIPAN: management of really sick patients with anorexia nervosa. 2 edn, 2014:CR189. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Junior MARSIPAN: management of really sick patients under 18 with anorexia nervosa. CR168. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Achamrah N, Coëffier M, Déchelotte P. Physical activity in patients with anorexia nervosa. Nutr Rev 2016;74:301–11. 10.1093/nutrit/nuw001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oliver D. David Oliver: Fighting pyjama paralysis in hospital wards. BMJ 2017;357:j2096. 10.1136/bmj.j2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kortebein P, Symons TB, Ferrando A, et al. Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:1076–81. 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asher RA. The dangers of going to bed. Br Med J 1947;2:967–8. 10.1136/bmj.2.4536.967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies S, Parekh K, Etelapaa K, et al. The inpatient management of physical activity in young people with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2008;16:334–40. 10.1002/erv.847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwartz BI, Mansbach JM, Marion JG, et al. Variations in admission practices for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a North American sample. J Adolesc Health 2008;43:425–31. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sylvester CJ, Forman SF. Clinical practice guidelines for treating restrictive eating disorder patients during medical hospitalization. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:390–7. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32830504ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akgül S, Pehlivantürk-Kızılkan M, Örs S, et al. Type of setting for the inpatient adolescent with an eating disorder: Are specialized inpatient clinics a must or will the pediatric ward do? Turk J Pediatr 2016;58:641–9. 10.24953/turkjped.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NICE. NICE Guidance 69. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. London: NICE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Third edition: American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Eating Disorders, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014;48:977–1008. 10.1177/0004867414555814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ 2016;353:i2016. 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bhanji S, Thompson J. Operant conditioning in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a review and retrospective study of 11 cases. Br J Psychiatry 1974;124:166–72. 10.1192/bjp.124.2.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yager JD, Halmi KA, Herzog DB, et al. Guideline watch (August 2012): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. 2012. 3rd edn. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/eatingdisorders-watch.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. Touyz SW, Beumont PJ, Glaun D, et al. A comparison of lenient and strict operant conditioning programmes in refeeding patients with anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 1984;144:517–20. 10.1192/bjp.144.5.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DiVasta AD, Feldman HA, Rubin CT, et al. The ability of low-magnitude mechanical signals to normalize bone turnover in adolescents hospitalized for anorexia nervosa. Osteoporos Int 2017;28:1255–63. 10.1007/s00198-016-3851-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parry SM, Puthucheary ZA. The impact of extended bed rest on the musculoskeletal system in the critical care environment. Extrem Physiol Med 2015;4:16. 10.1186/s13728-015-0036-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DiVasta AD, Feldman HA, Quach AE, et al. The effect of bed rest on bone turnover in young women hospitalized for anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1650–5. 10.1210/jc.2008-1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DiVasta AD, Walls CE, Feldman HA, et al. Malnutrition and hemodynamic status in adolescents hospitalized for anorexia nervosa. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:706–13. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kerem NC, Riskin A, Averin E, et al. Respiratory acidosis in adolescents with anorexia nervosa hospitalized for medical stabilization: a retrospective study. Int J Eat Disord 2012;45:125–30. 10.1002/eat.20911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Griffiths R, Gross G, Russell J, et al. Perceptions of bed rest by anorexic patients. Int J Eat Disord 1998;23:443–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Escobar-Koch T, Banker JD, Crow S, et al. Service users' views of eating disorder services: an international comparison. Int J Eat Disord 2010;43:549–59. 10.1002/eat.20741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nierman DM, Mechanick JI. Bone hyperresorption is prevalent in chronically critically ill patients. Chest 1998;114:1122–8. 10.1378/chest.114.4.1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MacDonald C. Treatment resistance in anorexia nervosa and the pervasiveness of ethics in clinical decision making. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47:267–70. 10.1177/070674370204700308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Redgrave GW, Coughlin JW, Schreyer CC, et al. Refeeding and weight restoration outcomes in anorexia nervosa: Challenging current guidelines. Int J Eat Disord 2015;48:866–73. 10.1002/eat.22390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garber AK, Sawyer SM, Golden NH, et al. A systematic review of approaches to refeeding in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2016;49:293–310. 10.1002/eat.22482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ploutz-Snyder LL, Downs M, Goetchius E, et al. Exercise training mitigates multisystem deconditioning during bed rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2018;50:1920–8. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dalle Grave R. Intensive cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: eating disorders in the 21st century. 1 edn: Nova Science Pub Inc, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Conti M, et al. Inpatient cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2013;82:390–8. 10.1159/000350058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. El Ghoch M, Calugi S, Pellegrini M, et al. Physical activity, body weight, and resumption of menses in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res 2016;246:507–11. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Norton L, Sibbald RG. Is bed rest an effective treatment modality for pressure ulcers? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004;50:40–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vollman KM. Understanding critically ill patients hemodynamic response to mobilization: using the evidence to make it safe and feasible. Crit Care Nurs Q 2013;36:17–27. 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3182750767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dirks ML, Wall BT, van de Valk B, et al. One week of bed rest leads to substantial muscle atrophy and induces whole-body insulin resistance in the absence of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation. Diabetes 2016;65:2862–75. 10.2337/db15-1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Allen C, Glasziou P, Del Mar C. Bed rest: a potentially harmful treatment needing more careful evaluation. Lancet 1999;354:1229–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10063-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fernández-del-Valle M, Larumbe-Zabala E, Morande-Lavin G, et al. Muscle function and body composition profile in adolescents with restrictive anorexia nervosa: does resistance training help? Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:346–53. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1041612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ebmental-2018-300064supp001.docx (22.6KB, docx)