Abstract

Adolescent self-harm is an emerging public health challenge. It is associated with later psychiatric and substance use disorders, unemployment and suicide. Family interventions have been effective in a range of adolescent mental health problems and for that reason were reviewed for their effectiveness in the management of adolescent self-harm. The search identified 10 randomised and 2 non-randomised controlled trial conducted in the high-income countries. For the most part the evidence is of low quality. The interventions were classified as brief single session, intermediate-level and intensive family interventions depending on the intensity and duration of treatment. Brief interventions did not reduce adolescent self-harm. Intermediate interventions such as the Resourceful Adolescent Parent Programme, Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youth Programme and attachment-based family treatment were effective in reducing suicidal behaviour (effect size 0.72), suicide attempts (P=0.01) and suicidal ideations (effect size 0.95), respectively in the short-term with an absence of long-term follow-up data. Intensive adolescent interventions such as dialectical behaviour therapy and mentalisation-based therapy reduced suicidal ideation (effect size 0.89) and self-harm (56% vs 83%, P=0.01), respectively. The persistence of effects beyond the intervention end point is not known in many interventions. Early involvement of the family, an evaluation of the risks at the end of an acute crisis episode and a stepped-care model taking into account level of suicide risk and resources available to an adolescent and her/his family are likely to promote better outcomes in adolescents who self-harm.

Keywords: adolescent, self-harm, family, management

Introduction

Adolescent self-harm is an emerging public health challenge with significant physical, psychological and financial costs for the individual and society. Approximately 10% of adolescents have harmed themselves at some point with varying degrees of suicidal thoughts.1 2 The rates of remission of self-harm by early adulthood are high,3 but later anxiety and depressive disorders, substance misuse, future self-harm and being unemployed or not in any training are common.4 Completed and attempted suicide are more likely in adolescents who self-harm.5–7

Self-harm is an important indicator of future mental health status.4 It should be treated with interventions that target this behaviour and are able to address the accompanying psychiatric problems.4 Most individually focused interventions have proved of limited benefit in preventing repetition of self-harm,8 although provision of psychosocial support has met with some success.9 In this context, families are an integral part of an adolescent’s life,10 and it is common for the adolescents who self-harm to have family relationship difficulties.11 Family cohesion and adaptability also appears to be protective against recurrent suicidal behavior6; in contrast, conflict predicts heightened risk for suicidal behaviour.12

The current review aims to describe the effectiveness of interventions for adolescent self-harm with a family component including treatment-related moderators of effect. This information will assist the clinicians and researchers in choosing the most effective strategies for involving families in managing adolescent self-harm.

Methods

We searched bibliographic electronic databases, such as MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus, until April 2017. The following terms formed the basis of the search strategy: ‘self-harm’ OR ‘deliberate self-harm’ OR ‘DSH’ OR ‘self-injurious behaviour’ OR ‘self-injury’ AND ‘family’ OR ‘parents’ OR ‘caregivers’.

The studies were included if they:

examined an intervention with a family component;

included children and/or adolescents younger than 19 years;

were specifically designed to treat self-harm;

measured a specific outcome related to self-harm.

We classified the interventions as follows:

Brief single session interventions: a single session intervention delivered in the emergency room. The single session is based on cognitive analytic therapy13 or cognitive behavioural therapy techniques.14 15

Intermediate-level family interventions: intervention sessions delivered over 12 weeks or less. The interventions in this category consist of providing information to parents about normal adolescent development and self-harm; practical strategies to deal with self-harm; strategies to promote family harmony; strategies to reduce family conflict; communication strategies and problem-solving techniques.16–18 One of the interventions strengthened parent–adolescent attachment bonds to create a protective and secure base for adolescent development.19

Intensive family interventions: interventions with intensive family input with sessions going beyond 12 weeks. This category includes interventions such as adolescent adaptation of dialectical behaviour therapy and metallisation-based therapy,20 21 and multisystemic family therapy that addressed the contributors to self-harm in an adolescent’s natural social environment.22

Results

We identified 10 randomised controlled trials and 2 non-randomised pilot clinical trials with an integrated family component (table 1). We summarise here the retrieved evidence, according to the type of intervention.

Table 1.

Interventions for adolescent self-harm with family component

| Intervention, sample | Sessions | Evidence available | Advantages | Disadvantages | Limitations |

| Brief single session family interventions | |||||

| Therapeutic assessment (TOTAL)13

12–18 years, n=69 |

Single session Outcome assessment: 1 year, 2 years |

RCT Control: UC |

Improved engagement at 1 year and 2 years follow-up (IRR 1.67 (95% CI 1.22 to 2.28), z=3.22, P=0.001) | No significant effect on number of presentation to ED or self-harm episodes | Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding clinical personnel due to nature of intervention, reporting and attrition bias unclear |

| Family-based CBT14 (family intervention for suicide prevention, FISP) 10–18 years, n=181 |

Single session CBT in ED, phone contact 48 hours post-discharge and at other times during 1st month | RCT Control: EUC |

Engagement with the outpatient services better in the FISP group as c/t control group at 2 months f/u (92% vs 76%; OR=6.2; 95% CI=1.8 to 21.3, P=0.004) | No significant effect on SI or SA. | Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding clinical personnel due to nature of intervention |

| Family-based crisis intervention15 (FBCI) 13–18 years, n=100 |

Single session based on CBT techniques Outcome assessment: 1 day, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months |

Pilot study | Suicidal adolescents and families presenting to ED during FBCI significantly more likely to be discharged home (and not admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit) as compared with the comparison cohort (65% vs 44.7%) | No improvement in depression, hopelessness, family cohesion or adaptability at various time points. No data available on SI or SA. |

Very serious risk of bias: no randomisation, no blinding of participants and clinical personnel resulting in performance and detection bias, reporting bias was unclear. |

| Intermediate-level family interventions | |||||

| Resourceful Adolescent Parent Programme (RAP-P)16

12–17 years, n=48 |

Four sessions 2 hours each delivered weekly/fortnightly. Sessions included: Outcome assessment: baseline, 3 months, 6 months |

RCT Control: UC |

Significant reduction in adolescent suicidality (included suicide attempt, ideas, intent, other deliberate self-harm behaviour) with intervention post-treatment and at 6 months f/u (ES 0,72), mediated by improvement in family functioning. Reduced psychiatric disability (the effect size not specified). | No differentiation between those with suicidal ideation and attempters | Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention. |

| Brief home-based problem-solving treatment17

<16 years, n=162 |

One assessment session in the hospital Four sessions in home by social worker Outcome assessment: baseline, 2 months, 6 months |

RCT Control: UC |

Significant improvement in SI at 2 (df=2.49, F=8.7, P<0.01) and 6 months (df=2.48, F=8.6, P<0.01) in non-depressed group. | Only measured SI. No outcome measures related to SA or NSSI. No significant improvement in SI overall (mean difference between groups at 2 months: − 3.37 (95% CI − 19.3 to − 12.5); 6 months: −5.1 (CI − 17.5 to −7.3)) and in depressed subgroup. No significant improvement on the measures of hopelessness or family functioning. |

Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention, reporting bias was unclear. |

| Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youth Programme (SAFETY)18

11–18 years, n=42 |

Family centred treatment delivered by two therapists, one for youth and another for the family, over 12 weeks. Outcome assessment: baseline, 3 months (or end of treatment), 6 months, 12 months |

RCT Control: E-TAU |

Significant between group difference with less SA in intervention group at 3 months axe (z=2.45; P=0.01, NNT=3.0). | Nil significant difference in NSSI between two groups. Treatment effects weakened on 6 and 12 months follow-up (the values at these time points not reported). |

Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention, reporting bias unclear. |

| Attachment-based family therapy19

12–17 years, n=66 |

Intervention for 12 weeks: relational reframe task, adolescent alliance task, parent alliance task, reattachment task, competency task, enhanced usual care. Facilitated referral process with ongoing clinical monitoring. Outcome assessment: baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks |

RCT Control: EUC |

Significant reduction in self-rated and clinician rated SI at treatment end (12 weeks, effect size 0.95 in favour of ABFT) and follow-up period (24 weeks, effect size=0.97 in favour of ABFT). | Cannot be used if family therapy contraindicated (eg, if the conflict too high). 3/4th sample consisted of African-American, and ½ below poverty level. Findings need replicated in culturally diverse population. | Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention, reporting bias unclear. |

| Intensive family interventions | |||||

| Multisystem family therapy22

10–17 years, n=156 |

Intensive treatment for 3–6 months with almost daily contact Outcome assessment: baseline, 4 months, 16 months (1-year post-treatment completion) |

RCT Control: inpatient admission |

Improvement in SA in those aged 9–12 years post-treatment (4 months) and 1 year f/u as reported by youth and caregivers (intergroup difference- control vs intervention 50% vs 20% reported SA at 4 months, 20% vs 10% at 1 year f/u). In 12–17 years, significant improvement in SA post-treatment & 1 year follow-up only on youth report (TE 3.6, not supported by caregiver reports). Improvement in parental control at 1 year f/u (TE 2.08) |

No significant difference in SA in 12–17 years at 1 year f/u as reported by caregivers. No improvement in depression, hopelessness and SI post-treatment or post-follow-up. |

Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention. |

| DBT-A20

12–18 years, n=77. |

DBT 19 weeks Two sessions/week (individual and multifamily skills training each week), family therapy sessions, telephone coaching Outcome assessment: baseline, 9 weeks, 15 weeks, 19 weeks |

RCT Control: EUC for 19 weeks (one session per week) |

Significant decrease in self-harm frequency during and post-treatment (at 19 weeks) on longitudinal analyses (P=0.021) and depressive symptoms (ES=0.88). Significant improvement in SI (ES=0.89) and hopelessness (ES=0.97). | No significant difference in cross-sectional analyses of number of self-harm episodes per patient by the end of the therapy period or depression scores. No information available on maintenance of treatment effect. Follow-up was restricted to post-treatment period. |

Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention, reporting bias unclear. |

| DBT-A25

13–19 years, n=29 |

26 weeks, weekly individual therapy and group skills training, telephone support Outcome assessment: Baseline, 3 months, 6 months |

RCT Control: TAU |

DBT-A was acceptable to clients, parents, caregivers and clinicians; 93% participants in the intervention group completed the therapy. | No significant reduction in the proportion of participants repeating SH or the numbers of SH episodes per patient by the end of the therapy period in intervention group. | Serious risk of bias: performance and detection bias due to difficulty in blinding participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention; reporting bias unclear. |

| DBT adaptation for adolescents24

n=111 |

12 weeks (twice a week with individual, once-a-week family skills training, family therapy if needed) Outcome assessment: baseline, 12 weeks |

Pilot study for intervention adaptation | Significant reduction in number of hospital admissions and treatment completion rates as c/t control (0% in DBT group as c/t 13% in control group). Significant improvement in SI and psychiatric symptoms in the treatment group when compared with pretreatment period (SI = 9.8 pretreatment, 3.8 post-treatment, P<0.05). |

No significant improvement in SA with treatment. DBT group consisted of adolescents meeting three or more borderline personality criteria with SA in past 16 weeks and might differ in phenomenology to control group that had either of two criteria. |

Very serious risk of bias: selection bias due to non-randomised study design, difficulty in blinding of participants and clinical personnel due to nature of intervention leading to performance and detection bias. |

| MBT adaptation for adolescents21

14.8 years, n=80 |

1 year (weekly MBT-A, monthly MBT-F) Outcome assessment: baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months Interviews: baseline, 1 year |

RCT control: TAU |

Significantly more reduction in self-harm on self-report and interview at 1 year in the intervention group as c/t control (56% vs 83%, P=0.01, NNT=3.66, 95% CI=2.19 to 17.32) Significantly greater reduction in self-reported features of borderline personality at 1 year in intervention group as c/t control (d=0.36). Difference in the depressive symptoms between the two group was significant (greater reduction in intervention group, maximum at 9 months, OR 0.21 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.98) |

Comparable in quantity Control intervention non- manualised Effect size modest |

Serious risk of bias: due to difficulty in blinding of clinical personnel due to nature of intervention leading to performance and detection bias; attrition and reporting bias unclear. |

c/t, compared with; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; DBT, dialectical behaviour therapy; ED, emergency department; ES, effect size; E-TAU, enhanced treatment as usual; EUC, enhanced usual care; f/u, follow-up; IRR, incidence rate ratio; MBT-A, metallisation-based therapy individual sessions; MBT-F, metallisation-based family therapy sessions; NNT, number needed to treat; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SA, suicide attempt; SI, suicidal ideation; TE, treatment effect; TAU, treatment as usual; UC, usual care.

Brief single session family intervention

The emergency setting single session family interventions include the Trial of Therapeutic Assessment in London (TOTAL),13 Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP)14 and a family-based crisis intervention (FBCI)15 (table 1). The TOTAL trial compared the impact of therapeutic assessment (TA) based on cognitive analytic therapy with assessment as usual in adolescents presenting to the emergency department with self-harm.13 There was no significant reduction in the self-harm attempts and presentation to the hospital with the intervention. However, it improved engagement with the services of the families and adolescents at 3 months after the initial assessment and 2 years follow-up (table 1).13

FISP was a single family-based cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) session comprising reframing suicide attempt as a problem requiring action, providing information to the families about existing mental health services, restricting access to means, development of a safety plan and obtaining a commitment from the youth to its use.5 Identifying the individual and family strengths and incorporating it in the plan improved family support. The engagement with the services was significantly better at 2 months follow-up in the intervention group (table 1). There was no difference in the suicidal thoughts and attempt between the two groups.

FBCI was tested in a pilot clinical trial by Wharff et al.15 A single skill building session for parents based on CBT techniques was administered by the social workers in an emergency department.15 The parents/caregivers and adolescents worked on a unified perception of the problem (the joint crisis narrative). CBT techniques such as relaxation, problem-solving and reframing cognitions were used to address the negative attributions. There was no improvement in depression, hopelessness and family cohesion scores with the intervention. The impact of this intervention on suicidal behaviour was not reported.

None of three single session family interventions improved self-harm or suicidal behaviour in adolescents.

Intermediate-level family interventions

The four interventions in this category included the Resourceful Adolescent Parent Programme (RAP-P),16 a brief home-based family problem-solving intervention,17 Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youth Programme (SAFETY)23 and attachment-based family treatment (ABFT).19

The brief four session parent education programme (RAP-P)16 provided practical information about the management of self-harm, identified parental strengths and promoted stress management, balance between attachment and independence, conflict resolution and promotion of family harmony. It brought significant reduction in adolescent suicidality (a combination of suicidal thoughts, attempts and other self-harm behaviour with no demarcation) compared with treatment as usual at 6 months follow-up (effect size 0.72). There was no further follow-up beyond 6 months. The authors reported a decrease in psychiatric morbidity but did not specify the effect size.

A brief home-based family problem-solving intervention17 (five sessions) was compared with routine care of children and adolescents presenting to the hospital with poisoning, in a large RCT. The intervention addressed the family problems hypothesised to contribute to adolescent self-harm by behavioural approaches such as modelling, behavioural rehearsal and other family therapy techniques such as psychoeducation and communication training for parents and adolescents. There was no significant difference between the two groups on measures of suicidal ideation (mean difference between groups at 2 months −3.37 (95% CI −19.3 to –12.5); at 6 months −5.1 (95% CI −17.5 to –7.3)). Furthermore, there was no improvement in the measures of hopelessness or family problems in the intervention group. A subgroup analysis showed a reduction in suicidal thoughts in the group without major depressive disorder (33% of the sample) at 2 months (mean difference −24.2 (95% CI −44.3 to −4.1) and 6 months (−16.7 (95% CI −29 to −4.4)) follow-up. There was no follow-up after 6 months.

The SAFETY trial by Asarnow et al 23 built-up on the findings of the FISP trial, and developed a 12-week cognitive-behavioural family intervention (SAFETY).23 In the RCT to test the effectiveness of the intervention, the suicide attempts were significantly less in the intervention group at 3 months follow-up (z=2.45; P=0.02, number needed to treat=3.0), with no significant decrease in the number of non-suicidal self-harm episodes.18 The positive effect of the intervention was weaker at 6 and 12 months follow-up.

The last intervention in the intermediate-level category is ABFT.19 ABFT approach uses process-oriented, emotion-focused and cognitive-behavioural techniques.19 The aim was to enhance the quality of attachment between parents and adolescents in weekly sessions over 3 months.19 It was compared with the enhanced usual care in a randomised controlled trial. Suicidal ideation reduced rapidly and significantly in the intervention group as measured by the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire, and the scale for suicidal ideation. The improvement was maintained at 12 weeks follow-up after completion of treatment (effect size 0.95 at 12 weeks and 0.97 at 24 weeks in favour of ABFT). A significantly larger number of participants dropped out of enhanced usual care arm during the trial. The study did not assess suicide attempts.

Intensive family interventions

There were three interventions in this category: multisystem family therapy (MST)22; adolescent adaptations of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT-A)20 24 25 and metallisation-based therapy for adolescents (MBT-A).26

Huey et al 22 compared MST,27 an intensive home-based treatment to inpatient treatment for self-harm in children and adolescents. The intervention involved therapists teaching communication skills to parents, discussing ways to engage adolescents in prosocial activities and addressed individual and systemic barriers to effective parenting. There was a daily contact by the therapist for a period of 3–6 months. There was a reduction in SAs in MST group than the hospital comparison group on adolescent report (treatment effect 3.6, not observed on parent report) from pretreatment to 1-year post-treatment completion. The suicide reattempt rate was similar in both the groups on parent report measures at the follow-up assessments. There was no improvement in the depressive symptoms, hopelessness or suicidal thoughts.

Rathus and Miller adapted DBT-A.24 The salient features were: shorter duration of therapy (12 weeks) to make it feasible for adolescents; multifamily skills training group in addition to individual skills training group twice weekly with the parents (12 weeks) to allow them to serve as coaches to generalise and maintain the skills learnt, and to make the home environment more validating; inclusion of parents/family members in individual therapy sessionswhen needed; limiting the number of skills and simplifying the language on the handouts to make it easier for adolescents to complete in 12 weeks.

In a small feasibility trial, Cooney et al compared DBT-A with treatment as usual with no apparent benefit of DBT-A.25 A recent RCT compared DBT-A with treatment as usual in 77 adolescents.20 In this trial, 19 weeks of DBT-A consisting of two sessions per week (one individual and multifamily skills training session each), family therapy sessions and telephone coaching, was significantly more effective in reducing self-harm episodes and depressive symptoms during and post-treatment (at 19 weeks) on longitudinal analyses. The difference in the cross-sectional analyses of number of self-harm episodes per patient by the end of the therapy period or depression scores between the two groups was not significant (table 1).11

Rossouw and Fonagy adapted MBT-A by including both individual and family therapy in a manualised 12-month intervention programme.21 The intervention was based on attachment theory and involves weekly individual MBT-A sessions and monthly mentalisation-based family therapy lasting for 50 min with a focus on impulsivity and affect regulation. The programme aimed to promote a patient’s capacity to understand and express their own and others’ feelings accurately in emotionally challenging situations. At the end of 1 year, there was a significant reduction in self-harm in the intervention group as compared with the control group ((56% vs 83%, P=0.01) and improvement in depressive and borderline personality features (table 1).21 There was no follow-up following the intervention completion.

Discussion

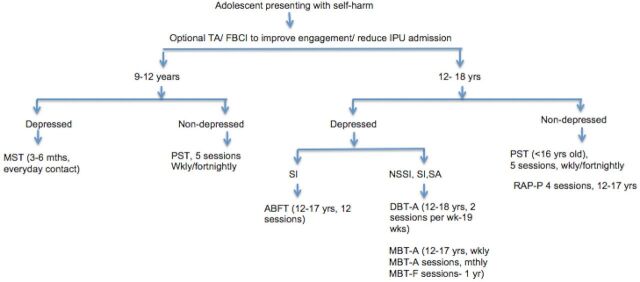

Figure 1 shows the range of family interventions in adolescent self-harm based on the limited available literature on the effectiveness of family interventions for adolescent self-harm. All included studies were conducted in high-income countries, but with significant limitations in terms of risk of bias in their methodology and design. Single session interventions did not have any significant impact on adolescent self-harm. Intermediate-level interventions showed some short-term gains but without follow-up data beyond 6 months, we know little about whether the improvement was maintained. Intensive interventions showed the most promising results but are resource intensive and given the lack of follow-up data, it is difficult to assess their benefits over intermediate-level interventions.

Figure 1.

Family intervention in adolescent self-harm. ABFT, attachment-based family therapy; DBT-A, dialectical behaviour therapy-adolescent adaptation; FBCI, family-based crisis intervention; IPU, inpatient unit; MBT-A, mentalisation-based therapy adolescents adaptation/session; MBT-F, mentalisation-based therapy family session; MST, multisystem therapy; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; PST, problem-solving therapy; SA, suicide attempt; SI, suicidal ideations; TA, therapeutic assessment.

Duration of the intervention was an important influence on effectiveness. Available interventions varied from a single session in the emergency department to others lasting for 12 months. None of the brief single session intervention resulted in a significant difference in self-harm thoughts or attempts but were effective in improving long-term engagement with the services,13 14 and reducing the likelihood of inpatient psychiatric hospitalisation.15

The intermediate-level problem-solving family-based intervention was not effective in reducing suicidal thoughts in depressed adolescents, and did not improve family functioning or hopelessness.17 On the other hand, RAP-P reduced suicidal thoughts and behaviour significantly by improving the family functioning and the effect was maintained at 6 months follow-up (table 1).16 There are no data beyond this period to suggest that the improvement was long lasting.

The results of intensive interventions were more promising. MST, lasting for 3–6 months, found reductions in suicide attempts on youth self-report at 1-year follow-up.22 Both the long-term interventions, MBT-A for a year and DBT-A over 5 months, were successful in reducing suicidal ideation, and depressive symptoms (table 1).20 21 Additionally, DBT-A reduced self-harm episodes longitudinally (although not confirmed by cross-sectional analysis) and MBT-A resulted in a significant improvement of borderline personality symptoms.20 21 These findings are consistent with the findings from studies in the adults. The longer duration of treatment is associated with larger increase in the treatment effect in adults.28 29 For example, DBT in adults is a 12-month programme,28 and CBT for suicidal adults consists of 10 sessions delivered over a variable period depending on the completion of the relapse prevention task.29

Some interventions seem more feasible for integration into psychiatric services. Additionally, the acceptability of the intervention by the clients and the family members is a crucial aspect in deciding the feasibility of any approach.30 The brief single session interventions such as therapeutic assessment delivered in the emergency department were well accepted by the clients and families and could practically be used for any adolescent to improve engagement with the psychiatric services.13 Similarly, intermediate-level interventions such as RAP-P programme may be more acceptable and easy to integrate in the current services than resource-intensive MST.16 22 Intensive interventions, such as DBT-A or MBT-A, require specialist resources such as two therapists working with the family (one with the client and another with the family), regular staff supervision to ensure support and training, and the skills group for adolescents in DBT-A.20 21 25 These interventions last for 5 months to a year, a long commitment for the client and the family members of a difficult-to-treat group with high dropout rates from treatment.20

An assessment to carefully evaluate the family and adolescent resources following the resolution of an acute crisis is likely to be helpful in identifying the treatment options best suited to the needs of the clients, thus reducing the treatment dropout rates. This could result in more pragmatic services and economically sustainable specialist programme. For example, if the problems are arising due to ongoing conflict with the primary attachment figure, and the adolescent has reasonable problem-solving skills, a 12-session ABFT may be a treatment option for an adolescent presenting with suicidal thoughts with no suicidal acts or non-suicidal self-harm. This intervention is less resource intensive when compared with DBT-A or MBT-A. For adolescents with depressive symptoms, suicidal and non-suicidal self-harm, both DBT-A and MBT-A seem promising approaches.

The question of maintenance treatment for adolescent self-harm could not be addressed in this review as most studies provided little or no follow-up data beyond the intervention.18 20 21 24 In a small number of studies, the follow-up varied from a month after the intervention to 2 years postintervention.13 14 Treatment gains were maintained at 6 months follow-up in RAP-P programme, and home-based problem-solving treatment and ABFT (approximately 3–4 months after the treatment completion).16 17 19 In contrast, the SAFETY intervention, another intermediate-level approach, protected against suicide attempts during the treatment period, but the benefits reduced substantially on 12-month follow-up.18 Similarly in intensive MST trial, parental control was significantly more during the intervention but failed to sustain at 1 year postintervention follow-up.22 Continuation or maintenance sessions may promote better long-term outcomes.18 Long-term follow-up of the clients receiving various interventions is needed to estimate the value of an intervention in reducing the self-harm behaviour and in tackling associated difficulties in the personal, professional and social domains.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the poor methodological quality of the available studies, there is growing evidence of the importance of families in the management of adolescent self-harm. They can be considered as partners in providing care and promoting engagement with treatment services. Although brief single session interventions in the emergency department do not reduce the adolescent self-harm, they are likely to be a useful strategy for promoting better engagement with the psychiatric services. Intermediate-level interventions show benefits but maintenance sessions seem likely to be a useful adjunct in ensuring the persistence of those effects. Although intensive interventions are the most promising, there remains a need to consider the long-term persistence of their effects and their relative cost-effectiveness, particularly in resource-poor settings.

Every plan needs to be individualised and there is unlikely to be a single appropriate response to adolescent self-harm. An evaluation of the risks at the end of an acute crisis episode, and a stepped-care model of deciding the appropriateness and the intensity of the intervention after consideration of family’s and adolescent’s resources remain essential to achieving better outcomes.31

Acknowledgments

GP is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship 1117873.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors were involved in conceptualisation, planning and interpretation of data. SA was involved in data collection. Both authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Aggarwal S, Patton G, Reavley N, et al. Youth self-harm in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review of the risk and protective factors. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2017;63:359–75. 10.1177/0020764017700175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 2012;379:2373–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moran P, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, et al. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2012;379:236–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61141-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moran P. Adolescents who self-harm are at increased risk of health and social problems as young adults. Evid Based Ment Health 2015;18:52. 10.1136/eb-2014-102018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:772–81. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, et al. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:495–501. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:297–303. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brent DA, McMakin DL, Kennard BD, et al. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: a critical review of intervention studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:1260–71. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Improving adolescent health through interventions targeted to parents and other caregivers: a recommendation. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:327–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016;387:2423–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saunders KE, Smith KA. Interventions to prevent self-harm: what does the evidence say? Evid Based Ment Health 2016;19:69–72. 10.1136/eb-2016-102420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boergers J, Spirito A, Donaldson D. Reasons for adolescent suicide attempts: associations with psychological functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:1287–93. 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ougrin D, Boege I, Stahl D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus usual assessment in adolescents with self-harm: 2-year follow-up. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:772–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:1303–9. 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wharff EA, Ginnis KM, Ross AM. Family-based crisis intervention with suicidal adolescents in the emergency room: a pilot study. Soc Work 2012;57:133–43. 10.1093/sw/sws017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pineda J, Dadds MR. Family intervention for adolescents with suicidal behavior: a randomized controlled trial and mediation analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:851–62. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harrington R, Kerfoot M, Dyer E, et al. Randomized trial of a home-based family intervention for children who have deliberately poisoned themselves. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:512–8. 10.1016/S0890-8567(14)60001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, et al. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:506–14. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53:1082–91. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51:1304–13. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, et al. Multisystemic therapy effects on attempted suicide by youths presenting psychiatric emergencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;43:183–90. 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Asarnow JR, Berk M, Hughes JL, et al. The SAFETY Program: a treatment-development trial of a cognitive-behavioral family treatment for adolescent suicide attempters. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2015;44:194–203. 10.1080/15374416.2014.940624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rathus JH, Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2002;32:146–57. 10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cooney E, Davis K, Thompson P, et al. Feasibility of evaluating DBT for self-harming adolescents: a small randomised controlled trial. Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui, Auckland, New Zealand 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51:1304–13. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong K, Watling H, Buckley L. The nature and correlates of young women’s peer-directed protective behavioral strategies. Addict Behav 2014;39:1000–5. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:757–66. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294:563–70. 10.1001/jama.294.5.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:452–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hetrick SE, Yuen HP, Bailey E, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for young people with suicide-related behaviour (Reframe-IT): a randomised controlled trial. Evid Based Ment Health 2017;20:76–82. 10.1136/eb-2017-102719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]