Background & Aims:

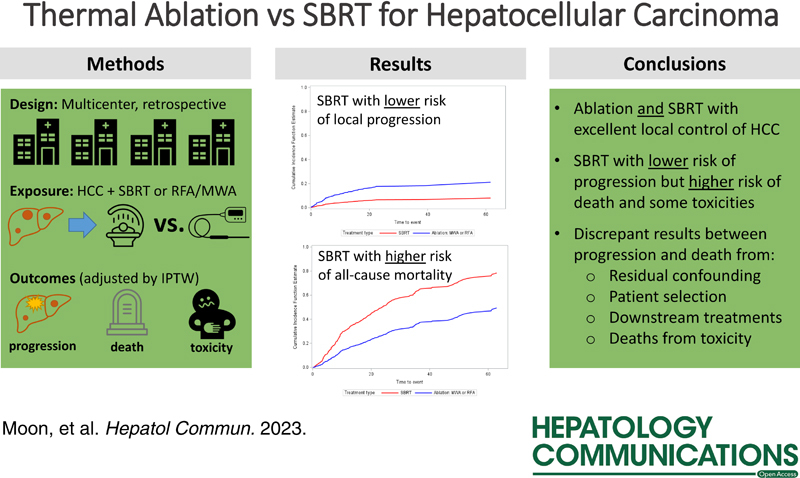

Early-stage HCC can be treated with thermal ablation or stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). We retrospectively compared local progression, mortality, and toxicity among patients with HCC treated with ablation or SBRT in a multicenter, US cohort.

Approach & Results:

We included adult patients with treatment-naïve HCC lesions without vascular invasion treated with thermal ablation or SBRT per individual physician or institutional preference from January 2012 to December 2018. Outcomes included local progression after a 3-month landmark period assessed at the lesion level and overall survival at the patient level. Inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to account for imbalances in treatment groups. The Cox proportional hazard modeling was used to compare progression and overall survival, and logistic regression was used for toxicity. There were 642 patients with 786 lesions (median size: 2.1 cm) treated with ablation or SBRT. In adjusted analyses, SBRT was associated with a reduced risk of local progression compared to ablation (aHR 0.30, 95% CI: 0.15–0.60). However, SBRT-treated patients had an increased risk of liver dysfunction at 3 months (absolute difference 5.5%, aOR 2.31, 95% CI: 1.13–4.73) and death (aHR 2.04, 95% CI: 1.44–2.88, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

In this multicenter study of patients with HCC, SBRT was associated with a lower risk of local progression compared to thermal ablation but higher all-cause mortality. Survival differences may be attributable to residual confounding, patient selection, or downstream treatments. These retrospective real-world data help guide treatment decisions while demonstrating the need for a prospective clinical trial.

INTRODUCTION

HCC is the third most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide and the most common cause of cancer-related death in patients with cirrhosis1. Locoregional therapies, such as thermal ablation [eg, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave ablation (MWA)] and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), can be used to treat HCC in patients who are not eligible for curative resection2,3. In the absence of a comparative effectiveness randomized trial, the optimal modality of liver-directed therapies in patients with HCC not amenable to surgical resection is not well established2,4,5.

Thermal ablation involves the direct delivery of energy to tumors, causing cell death by coagulation necrosis. It is proposed as a first-line option for patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (solitary HCC ≤ 2 cm) or unresectable stage A (single nodule or ≤3 nodules with nodule diameter all <3 cm) HCC2,5. Thermal ablation has been applied percutaneously, laparoscopically, or through laparotomy with excellent local control rates for small tumors. MWA achieves more extensive tumor necrosis and improved effectiveness for larger lesions compared to RFA6–8. SBRT involves the delivery of highly targeted, fractionated radiation doses delivered with image guidance to liver tumors. SBRT is a promising alternative to RFA or MWA, with emerging data supporting its efficacy9. However, SBRT is not yet included as a primary treatment modality in all HCC treatment guidelines or in the updated BCLC system as there is less data using this modality at present4,5,10.

Observational studies have generally demonstrated a reduced risk of tumor progression or recurrence among lesions treated with SBRT compared to ablation11–14. These studies have been primarily conducted in single-center settings, with a high proportion of patients who have noncirrhotic viral hepatitis, and using RFA, rather than MWA, as the primary comparative ablation modality. Furthermore, the understanding of post-SBRT radiologic changes of a treated lesion has evolved over time, which has led to improved accuracy of radiologic treatment response assessment15. Most comparative studies of SBRT and ablation have reported no significant differences in overall survival11–14,16–19. There is 1 study in the US National Cancer Database, which reported improved overall survival with thermal ablation compared to SBRT, but it is limited by the lack of information on liver disease severity, comorbidities, and cancer stage20. Prospective comparative data of external beam radiation (such as SBRT) compared to thermal ablation are emerging, but, to date, this has been limited to assessing proton beam radiotherapy compared to RFA in a cohort of patients with predominantly HBV and small, recurrent HCC21. Perhaps, due to limited data and conflicting guidelines, SBRT remains a less frequently used liver-directed therapy for HCC in the US22–25.

Given the current knowledge gaps regarding the relative effectiveness of these locoregional therapies, the aim of this multicenter retrospective cohort study was to compare local progression, toxicity, and overall survival between HCC lesions and patients treated with thermal ablation or SBRT.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Study design

This was a multicenter retrospective cohort study at 4 major academic transplant centers in the US, with 1 center serving as the data coordinating center. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each respective center. Given that this research was retrospective, a waiver of informed consent was granted. All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul.

Population

This study included all adult (≥18 y) patients with HCC, diagnosed by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases criteria2, who had undergone MWA, RFA, or SBRT between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2018. We excluded patients who received combination therapies within 3 months of index visit (eg, combined MWA + transarterial chemoembolization) to the target lesion or whose target lesion was previously treated; however, we permitted inclusion of patients with prior locoregional therapy to a different (ie, off-target) lesion. Finally, we excluded patients with macrovascular invasion or metastatic spread.

Treatment modalities

Patients included in the analysis were treated with thermal ablation (either MWA or RFA) or SBRT. At each institution, decisions regarding the treatment modality were made by a multidisciplinary tumor board, including transplant surgeons, radiation oncologists, hepatologists, interventional radiologists, and medical oncologists. Technical details of thermal ablation and SBRT performed at each institution are included in Supplemental Information, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327.

Covariates

We extracted baseline patient data from the electronic medical record, including age, sex, etiology of cirrhosis, serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP), the model for end-stage liver disease score, Child-Pugh score (CPS), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, tumor size, tumor location, and the number of tumors. Based on tumor size and number, liver disease severity, and performance status, we calculated the BCLC stage for each treatment provided5. We additionally calculated a modified BCLC stage, as outlined in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines,2 which allows BCLC 0-B patients to have an ECOG performance status of 0–1. Finally, we collected data on the specifics of HCC treatment, including prior locoregional therapies and radiation dose and fractionations (for SBRT).

Follow-up

Patients were followed from the time of their SBRT or thermal ablation treatment until death, last follow-up visit, or December 31, 2019. Clinical outcomes, including retreatment, liver transplantation, death, and posttreatment toxicities, were abstracted from the electronic medical record. For posttreatment toxicity, we recorded the following: (1) early (<30 d since treatment completion) grade ≥ 3 National Institutes of Health-defined Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE)26, (2) grade ≥ 3 GI-related adverse events (AE) ≥ 30 d after treatment, (3) grade ≥ 3 hepatobiliary-related AEs ≥ 30 d after treatment, (4) increase from pre-treatment CPS ≥ 2 points at 3 mo, and (5) increase from pre-treatment CPS ≥ 2 points at 6 months. CTCAE grade ≥ 3 toxicities were inclusive of AEs that resulted in death.

For radiologic outcomes, diagnostic radiologists with at least 6 years of experience, who were blinded to the type of locoregional treatment at each site, assessed posttreatment radiologic response by reviewing and scoring each posttreatment MRI or CT scans until 2 years after treatment. Radiologists determined pre-treatment tumor size (long axis and short axis) and radiologic response based on the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors response (complete response, partial response, stable disease, and progressive disease)27. Progression at the lesion level was defined as progressive disease based on the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors or salvage treatment of the same lesion. Reablation at one month was not considered salvage treatment and, therefore, was not included in this definition of lesion-level progression.

Statistical analysis

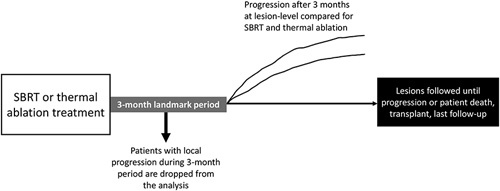

We performed patient and tumor level comparisons for ablation (MWA or RFA) and SBRT treatments. Our primary outcome was the lesion-level time to progression, defined as the time from treatment to the local progression of the target lesion. For this analysis, the development of new lesions elsewhere in the liver was not counted as progression. Given the difficulty of determining radiologic progression after SBRT due to persistent hyperenhancement28 and the possibility for immortal time bias for patients who receive their first posttreatment imaging at 3 months, we performed a landmark analysis assessing time to local progression at ≥3 months after treatment (Figure 1). Secondary outcomes included overall survival from the first treatment, censored at the last follow-up for those who were still alive, and the proportion of patients with liver toxicity (AEs or increase in CPS at 3 and 6 mo).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of landmark analysis used for the analysis of local progression at the lesion level.

We produced cumulative incidence curves of time to progression and overall survival. We performed the Cox proportional hazard modeling to compare progression and overall survival, and logistic regression modeling was used to compare liver toxicity. Given the potential for imbalances between treatment groups, we applied inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). For the lesion-level comparison of local progression, we weighted by age, sex, treatment center, tumor size, tumor location, AFP, CPS, ECOG, and the number of prior off-target treatments. For the treatment-level analysis of toxicity and patient-level analysis of overall survival, we additionally weighted by the number of treated lesions. We calculated weighted standardized differences to ensure that all variables were appropriately weighted (ie, differences within −0.2 to 0.2) in our treatment groups after IPTW.

For lesion-level time-to progression, we used a fine and gray subdistribution model to account for the competing risks of liver transplantation and death. Given that we were interested in assessing death from HCC, we accounted for liver transplant as a competing risk in our overall survival analysis. Given that ablation or SBRT may be used with the intent of bridging to transplant, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which liver transplant was not considered a competing risk for death. After propensity weighting, the Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed for local progression and overall survival, adjusting for the year of treatment, and multivariable logistic regression modeling, adjusting for the year of treatment and subsequent salvage treatment, was used to compare odds of toxicities. Patients or lesions with missing data were removed from analyses. Multiple imputation was not performed since there was less than 10% of missing data for all variables29.

We performed several subgroup analyses that were defined a priori: lesion size>2 cm and≤2 cm, lesion size>3 cm and≤3 cm, baseline Child-Pugh A/B7 and B8/9/C, and viral and nonviral etiologies. We performed an exploratory subgroup analysis comparing SBRT to MWA and SBRT to RFA. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

The cohort included 642 patients who had 786 lesions treated with either thermal ablation (n = 440 patients with 550 lesions) or SBRT (n = 202 patients with 236 lesions). The baseline characteristics of patients stratified by treatment can be found in Table 1. The median age was 62 years [interquartile range (IQR): 58–69], 27% were female, and 69% were non-Hispanic white. The etiology of liver disease was primarily HCV (54%) followed by NAFLD (17%) and alcohol-associated liver disease (12%). The vast majority (95%) of patients had cirrhosis, with a median model for end-stage liver disease of 9 (IQR: 7–12) and 57% having CP-A liver disease. Using traditional BCLC categories, most patients were either BCLC A (38.2%) or BCLC-C (41.8%), given the large proportion of patients with ECOG 1 performance status. When using the modified BCLC staging, most patients were BCLC 0 (12.7%) or BCLC A (67.9%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients treated with SBRT and thermal ablation

| SBRT (n = 202) | Thermal ablation (n = 440) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (mean, SD) | 65.5 (11.3) | 62.0 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 52 (25.9) | 120 (27.3) | 0.7733 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Asian | 13 (6.5) | 15 (3.5) | 0.1361 |

| Black | 23 (11.5) | 64 (14.8) | — |

| Hispanic White | 21 (10.5) | 31 (7.1) | — |

| Non-Hispanic White | 131 (65.5) | 305 (70.3) | — |

| Other | 12 (6.0) | 19 (4.4) | — |

| Etiology of liver disease (%) | |||

| ALD | 22 (10.9) | 56 (12.7) | 0.0002 |

| ALD/HCV | 10 (5.0) | 14 (3.2) | — |

| HBV | 5 (2.5) | 16 (3.6) | — |

| HCV | 93 (46.0) | 252 (57.3) | — |

| NAFLD | 35 (17.3) | 73 (16.6) | — |

| Other | 37 (18.3) | 29 (6.6) | — |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 182 (90.6) | 424 (96.4) | 0.0043 |

| MELD (mean, SD) | 9.9 (3.5) | 10.6 (3.9) | 0.0221 |

| Child-Pugh class (%) | |||

| A | 111 (55.0) | 255 (58.0) | 0.8019 |

| B | 71 (35.2) | 145 (33.0) | — |

| C | 15 (7.4) | 33 (7.5) | — |

| ECOG performance status (%) | |||

| 0 | 83 (41.3) | 228 (55.6) | — |

| 1 | 95 (47.3) | 147 (35.9) | — |

| ≥2 | 23 (11.4) | 35 (8.5) | — |

| BCLC stage (%) | |||

| 0 | 9 (3.8) | 59 (10.7) | 0.0025 |

| A | 81 (34.5) | 219 (39.8) | — |

| B | 4 (1.7) | 14 (2.6) | — |

| C | 117 (49.8) | 211 (38.4) | — |

| D | 24 (10.2) | 47 (8.6) | — |

| Modified BCLC stage (%)a | |||

| 0 | 25 (10.6) | 75 (13.6) | 0.4865 |

| A | 157 (66.8) | 376 (68.4) | — |

| B | 14 (6.0) | 20 (3.6) | — |

| C | 15 (6.4) | 32 (5.8) | — |

| D | 24 (10.2) | 47 (8.6) | — |

| Prior treatments (%) | |||

| 0 | 107 (53.2) | 333 (75.9) | < 0.0001 |

| 1-2 | 61 (30.4) | 90 (20.5) | — |

| 3-4 | 25 (12.4) | 10 (2.3) | — |

| ≥5 | 8 (4.0) | 6 (1.4) | — |

Modified BCLC is based on AASLD guidelines in which BCLC 0, A, and B can include ECOG 0-12.

Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy; SD, standard deviation.

Ablation-treated patients were younger (median 62.0 vs. 65.5 y, p < 0.0001) and were more likely to have ECOG 0 (55.6% vs. 41.3%, p = 0.006) and cirrhosis (96.4% vs. 90.6%, p = 0.004). The pre-treatment CPS and modified BCLC stage were similar among ablation and SBRT-treated patients. More patients treated with ablation compared to SBRT had no prior off-target treatments (76% vs. 53%, p < 0.0001).

There were 216 SBRT treatments (236 lesions, 15.3% treatments for ≥2 lesions) and 492 thermal ablation treatments (550 total lesions, 20.5% treatments for ≥2 lesions). Baseline characteristics of treated lesions are given in Table 2. The median tumor size was 2.1 cm (IQR 1.6–2.8 cm). Most lesions were in the right lobe (67.0%), with fewer in the left lobe (30.4%) or caudate (1.9%). Among lesions treated with ablation, 379 (68.9%) received MWA, and 171 (31.0%) received RFA. For thermal ablation procedures, 347 (63.1%) were performed by a percutaneous approach, and 203 (36.9%) were performed with laparoscopic assistance. A total of 54 lesions (9.8%) required reablation at 1 month due to an incomplete ablation after the first procedure. Among SBRT treatments, the majority received either 3 (57.2%) or 5 fractions (40.7%), with most receiving a dose per fraction of 10 Gy (25.4%), 12 Gy (17.4%), or 15 Gy (17.4%). The mean Biologic Effective Dose of 10 Gy (Biologic Effective Dose of 10 Gy) was 88 (SD 27) (Supplemental Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327).

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of SBRT and ablation-treated lesions

| SBRT (n = 236) | Thermal Ablation (n = 550) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion size, cm (median, IQR) | 2.4 (1.8–3.4) | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Lesion location (%) | |||

| Right lobe | 156 (66.1) | 371 (67.5) | 0.0011 |

| Left lobe | 68 (28.8) | 171 (31.1) | — |

| Segment 1 | 11 (4.7) | 4 (0.7) | — |

| AFP (median, IQR) | 11 (4-69) | 9 (4-31) | 0.032 |

Outcomes, including lesion-level progression, patient-level liver transplant, death, and treatment-level complications, can be found in Tables 3–5.

TABLE 3.

Posttreatment outcomes among SBRT and ablation-treated lesions

| SBRT (n = 236) | Thermal Ablation (n = 550) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (months), median (IQR) | 11.4 (6.0–21.1) | 13.2 (6.8–25.4) | 0.0073 |

| Progression (after 3 months posttreatment) (%) | 15 (6.4) | 87 (15.8) | 0.0002 |

| Time to progression (months), median (IQR)a | 9.5 (3.3–16.1) | 5.8 (2.4–11.8) | 0.6502 |

| Salvage treatment within 1 y (%) | 10 (4.2) | 56 (10.2) | 0.0221 |

Note: Progression defined as a progressive disease based on mRECIST or salvage treatment of the same lesion.

Taking into account the 3-month landmark.

TABLE 5.

Posttreatment complications among SBRT and ablation treatments

| SBRT (n = 216)a | Thermal ablation (n = 492)a | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in CPS ≥ 2 at 3 mo | 28 (13.0) | 37 (7.5) | 0.024 |

| Increase in CPS ≥ 2 at 6 mo | 24 (11.1) | 36 (7.3) | 0.1071 |

| Early grade ≥ 3 CTCAE adverse event | 2 (0.9) | 38 (7.7) | <0.0001 |

| Late grade ≥ 3 CTCAE hepatobiliary adverse event | 14 (6.5) | 36 (7.3) | 0.7522 |

| Late grade ≥ 3 CTCAE GI adverse event | 13 (6.0) | 11 (2.2) | 0.0215 |

Numbers correspond to the total number of treatments, so there will be more than 1 entry for each patient who received more than 1 SBRT or ablation treatment.

Lesion-level local progression

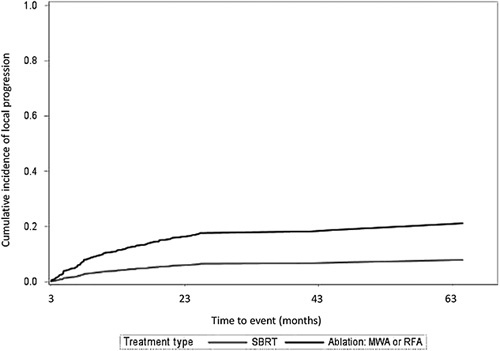

Median follow-up of lesions after treatment was 12.5 months (IQR 6.7–24.1), with shorter follow-up after SBRT (11.4 mo, IQR: 6.0–21.1) compared to ablation (13.2 mo, IQR: 6.8–25.4). After the 3-month landmark, 15 (6.4%) SBRT-treated lesions and 87 (15.8%) ablation-treated lesions had local progression (absolute difference: 9.4%). For those without local progression at the 3-month landmark, the median time to progression after the landmark was 9.5 months for SBRT-treated lesions (12.5 mo after treatment) compared to 5.8 months (8.8 mo after treatment) for ablation-treated lesions. In addition to the 9.8% of patients who required reablation at 1 month, a significantly higher proportion of ablation-treated lesions required salvage or retreatment within 1 year compared to SBRT-treated lesions (9.6% vs. 4.7%, p = 0.02).

In an unadjusted landmark analysis accounting for competing risks of death and liver transplant, lesions treated with SBRT had a significantly lower risk of local progression compared to ablation-treated lesions (HR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.20–0.61) (Figure 2). In the IPTW analysis, this difference remained statistically significant (HR 0.30, 95% CI: 0.15–0.60). Results were consistent across subgroups based on lesion size (≤2 cm vs. >2 cm), CPS (≤B7 vs. ≥B8), and liver disease etiology (viral vs. nonviral) (Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327). While the direction of the association remained consistent, survival differences were not statistically significant for patients with lesion size >3 cm or viral etiology of liver disease. SBRT appeared to have a lower risk of local progression compared to ablation with increasing lesion size, when examined as a continuous variable (Supplemental Figure 2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327). The exploratory analysis comparing SBRT versus MWA and SBRT versus RFA had similar results in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Supplemental Figure 3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative incidence (cases per month) of local progression for lesions treated with thermal ablation and stereotactic body radiation therapy. Accounts for competing risks of death and liver transplant. Time to event incorporates the 3-month landmark period. Abbreviations: MWA, microwave ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

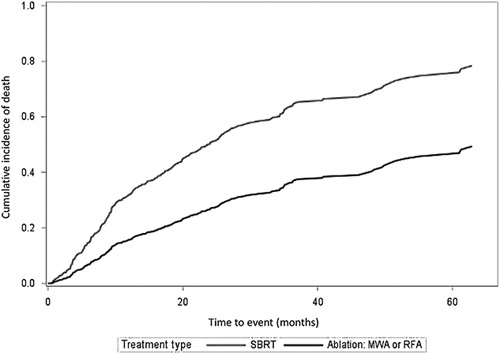

Overall survival

For the survival analysis, the median follow-up was 14.8 months (IQR 7.5–25.9) for SBRT-treated patients and 21.2 months (IQR 9.7–35.7) for ablation-treated patients (Table 4). The liver transplant was less common among SBRT-treated patients compared to patients treated with ablation (9.0% vs. 18.3%, p = 0.002). Ten patients who initially received SBRT underwent salvage treatment to the treated lesions within 1 year, including 4 who received systemic therapy as their first salvage therapy, while 56 patients who received ablation underwent salvage treatment within 1 year, including 7 who received systemic therapy as their first salvage therapy. Mortality from any cause occurred among 103 (52.3%) patients treated with SBRT with a median time to death of 9.1 months (IQR: 5.8–19.9). Patients treated with ablation had fewer deaths (n = 47, 25.4%) with a median time to death of 13.6 months (IQR: 5.9–27.3) (Figure 3).

TABLE 4.

Posttreatment outcomes among SBRT and ablation patients

| SBRT (n = 202) | Thermal Ablation (n = 440) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (months), median (IQR) | 14.8 (7.5–25.9) | 21.2 (9.7–35.7) | <0.0001 |

| Liver transplant (%) | 18 (9.0) | 80 (18.3) | 0.0024 |

| Time to liver transplant (months), median (IQR) | 14.3 (7.7–20.2) | 8.5 (6.1–13.0) | 0.0337 |

| Death (%) | 103 (52.3) | 47 (25.4) | <0.0001 |

| Time to death (months), median (IQR) | 9.1 (5.8–19.9) | 13.6 (5.9–27.3) | 0.0274 |

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative incidence (deaths per month) of mortality for patients treated with thermal ablation and stereotactic body radiation therapy. Accounts for competing risks of a liver transplant. Time to event incorporates the 3-month landmark period. Abbreviations: MWA, microwave ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

In unadjusted analysis accounting for liver transplant as a competing risk of death, patients treated with SBRT had a higher hazard of death (HR 2.25, 95% CI: 1.72–2.94). The hazard for death was similar when removing liver transplants as a competing risk (HR 2.06, 95% CI: 1.59–2.67). In the IPTW analysis weighted by age, sex, treatment center, tumor size, tumor location, the number of treated lesions, AFP, CPS, EGOG, and the number of prior off-target treatments and adjusted by year of treatment, this difference remained statistically significant when considering liver transplant a competing risk (HR 2.04, 95% CI: 1.44–2.88) and was similar when removing liver transplant as a competing risk of death (HR 1.82, 95% CI: 1.29–2.57). Subgroup analyses for overall survival were generally consistent, with an increased risk of mortality among SBRT-treated patients compared to ablation (Supplemental Table 2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327). The exploratory analysis comparing SBRT versus MWA and SBRT versus RFA had similar results in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Supplemental Figure 4, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327).

Liver-related toxicity

Posttreatment AEs, including increases in CPS after SBRT (n = 216) and ablation (n = 492) treatments, are listed in Table 5. The specific acute AEs, late GI AEs, and late hepatobiliary AEs can be found in Supplemental Tables 3-5, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327.

Increased CPS of ≥2 points were observed in 13.0% at 3 months and 11.1% at 6 months after SBRT, compared to 7.5% and 7.3%, respectively, after ablation. Early grade ≥3 CTCAE AEs occurred after 0.9% SBRT treatments compared to 7.7% ablation treatments. SBRT treatments were associated with a grade ≥3 CTCAE GI-related AEs 6.0% of the time and grade ≥3 CTCAE hepatobiliary AE 6.5% of the time. GI-related and hepatobiliary-related AEs were reported after 2.2% and 7.3% of ablation treatments, respectively.

In the IPTW analysis, weighted for age, sex, treatment center, tumor size, tumor location, the number of treated lesions, AFP, CPS, EGOG, and the number of prior off-target treatments and adjusted by interim salvage treatment and year of treatment, there was a statistically significant higher odds of CPS increase ≥2 points at 3 months (absolute difference 5.5%, OR 2.20, 95% CI: 1.14–4.23) for SBRT compared to ablation treatments. This difference was not statistically significant when assessing CPS increase ≥2 points at six months (absolute difference 3.3%, OR 1.59, 95% CI: 0.83–3.06).

In the IPTW multivariable model, there were no statistically significant differences between SBRT and ablation in early grade ≥3 CTCAE (OR 0.36, 95% CI: 0.51–1.25) or late grade ≥3 CTCAE hepatobiliary AEs (OR 2.08, 95% CI: 0.93–4.62). There were increased odds of late grade ≥3 CTCAE GI AEs for SBRT compared to ablation treatments in the IPTW multivariable analysis (OR 4.99, 95% CI: 1.64–15.2).

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter retrospective study evaluating the treatment response of small HCC lesions (median size: 2.1 cm), we found that both SBRT and thermal ablation were excellent treatments with a low risk of local progression. The risk of local progression was significantly lower among SBRT-treated compared to ablation-treated lesions after adjusting for potential confounders and with consistent effects across subgroup analyses. However, we found that patients treated with ablation had a lower likelihood of CPS increase at 3 months, a lower likelihood of late GI toxicity, and improved overall survival compared to those treated with SBRT. Early grade ≥3 CTCAE toxicities were numerically higher after thermal ablation compared to SBRT, but this was not statistically significant in adjusted analyses. Discrepant results between local progression and overall survival were likely, in part, driven by patient selection and downstream treatments, which were more likely to occur after ablation. Furthermore, survival differences were not statistically significant for lesions >3 cm. For these larger lesions, the additional local control provided by SBRT may translate into improved overall survival.

This study adds to the existing literature by providing data from a large, contemporary cohort composed predominantly of patients with cirrhosis and a large proportion with nonviral etiology of liver disease. In contrast to prior single-center studies, our study includes several large centers with expertise in both thermal ablation and SBRT and may be more generalizable to patients with cirrhosis and HCC. In addition, this study involved the rereview of posttreatment MRIs by diagnostic radiologists with extensive expertise in post-SBRT treatment response assessment30. Like prior studies, our results reveal a lower risk of local tumor progression after treatment with SBRT compared to ablation11–14. The risk reduction among lesions treated with SBRT appears to be largest in lesions >3 cm and viral etiology of liver disease. These findings demonstrate the potential promise of SBRT as an alternative to thermal ablation for very early or early-stage HCC. This is in addition to its emerging role for later stages of HCC in combination with systemic therapy, as shown by the recently presented RTOG 1112 trial, showing that SBRT added to sorafenib improves overall survival in BCLC-C HCC31.

In contrast to many of these studies, our analysis demonstrates that treatment with thermal ablation is associated with a significantly improved overall survival compared to SBRT. This is consistent with an analysis from the National Cancer Database20, which was limited by its lack of information on radiation dose, liver disease severity, and AFP levels32. Our analysis demonstrates that ablation is associated with improved survival after adjusting for important confounders, including age, sex, treatment center, tumor size/number, AFP, CPS, ECOG, and the number of prior off-target treatments. Of note, in IPTW analyses, the association between ablation and improved overall survival only remains statistically significant among patients with a nonviral etiology for their underlying liver disease. This may partially explain the discrepancy between our results and studies conducted in Asia, which were primarily composed of patients with HBV and showed no significant differences in overall survival12–14.

There has been debate about the most important endpoint to consider when comparing locoregional therapies for small HCC lesions. Guidelines have generally made recommendations based on differences in overall survival2,5,10. However, others have argued the importance of local tumor control because it may be difficult to tie a single treatment event to overall survival, given the effect of downstream treatments and competing risks of death32. While there have been studies reporting that progression based on imaging criteria (eg, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) correlates reasonably well with overall survival in HCC33–35, there are several reasons that could explain the apparent discrepancy between these outcomes in our analysis. First, while our analysis attempted to adjust for potential confounders with propensity weighting, it is possible that patients treated with SBRT had a higher burden of baseline comorbidities than those treated with ablation17. SBRT has only recently been included in treatment guidelines and may be reserved for patients with more comorbidities, given that it does not require general anesthesia. In addition to initial treatment selection, residual confounding could explain differences in receipt of downstream treatments and competing causes of death. Second, patients treated with SBRT were more likely to experience treatment-related toxicities, including CPS increases of 2 points or greater, potentially due to radiation-induced liver injury36. This may have led to a higher likelihood of cirrhosis-related deaths among those treated with SBRT in this study, as suggested by the overall survival analyses stratified by type of toxicity (Supplemental Table 6, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A327). The risk of radiation-induced liver injury may continue to decrease with evolving techniques to minimize radiation exposure to the background liver and better patient selection. While being statistically significant, the absolute differences were not large, suggesting that this alone does not explain the survival difference. Furthermore, this analysis was conducted between 2012 and 2018 when SBRT techniques were still evolving. While our analysis does account for treatment year and center, given the steep learning curve of SBRT and changing practices on dosimetry for HCC, dedicated studies on the optimal dose to balance local control and toxicity are needed. Third, patients treated with ablation were more likely to receive downstream treatments, which could lead to improved overall survival. The increased receipt of downstream locoregional therapies among patients treated with ablation could be due to a lower risk of posttreatment liver decompensation or because the image-based assessment for the viable disease after ablation is easier compared to image-based assessment after SBRT, secondary to the differences in the posttreatment imaging appearance between the 2 treatment modalities. While ablation-treated patients were also more likely to receive liver transplantation, this was accounted for in our analysis that included transplant as a competing risk of death. Data from multicenter, prospective randomized trials will be needed to adequately compare these treatment modalities. The one randomized trial that compares RFA with proton beam radiotherapy in patients with small, recurrent HCC reported that survival differences were noninferior21.

While this study is strengthened by its large, multicenter study design, granular data on patient characteristics and treatments, and dedicated rereads of posttreatment imaging by radiologists with experience in post-SBRT treatment response, it must be interpreted in the setting of its potential limitations. First, while our adjusted analyses attempted to account for confounders with propensity weighting, the potential for residual confounding remains possible. For instance, given that thermal ablation procedures require general anesthesia, it is possible that patients with a greater burden of comorbidities were more likely to receive SBRT due to its noninvasive treatment approach. In addition, the cohort of patients receiving SBRT in this study had significantly more prior liver-directed treatments, with 75.9% of patients in the ablation cohort having no prior treatment compared to 53.2% in the SBRT cohort although this was included in IPTW models. Second, there is the possibility of misclassification of covariates, such as ECOG performance status. Performance status may be underestimated in patients with HCC, given the effects of cirrhosis on activities of daily living,5 and this may have contributed to the high proportion of patients with ECOG ≥ 1 patients who were considered BCLC-C HCC despite a low burden of intrahepatic disease. Despite this potential misclassification, this would likely result in non-differential bias. Third, regarding radiologic outcomes, there remains a possibility of measurement error in the assessment of time to progression. Given that SBRT but not ablation is often associated with persistent posttreatment hyperenhancement, this could bias the assessment of local disease control. We took several steps to mitigate this bias, including the choice of progressive disease as our primary radiologic outcome, the use of a 3-month landmark, and the requirement for local radiologists to reread all posttreatment MRIs. Fourth, we do not have detailed dosimetry data for SBRT-treated lesions, making it difficult to determine how treatment response or toxicity is mediated by radiation dose. Fifth, given the retrospective nature of this study, we were unable to accurately determine the cause of death. Sixth, while we accounted for a liver segment of the treated lesion, we lack detailed information on the proximity of treated lesions to the bowel and biliary structures. Finally, these findings may not be as generalizable to less experienced centers. This potential limitation is minimized by the multicenter design, as all included participants were academic medical centers with extensive experience in both ablation and SBRT, although experience with SBRT was limited in the early years (eg, 2012–2015) of our cohort.

In conclusion, in this large, multicenter cohort of patients with HCC, both ablation and SBRT were associated with a low risk of local progression. SBRT was associated with a significantly lower risk of progression, while thermal ablation was associated with a lower risk of posttreatment toxicity and all-cause mortality. The discrepancy between progression and mortality data may be attributable to patient selection or downstream treatments. These findings provide some important real-world evidence, particularly for HCC patients with underlying cirrhosis, and demonstrate the need for more comparative effectiveness data from prospective clinical trials. Given that the management of HCC is complex and based on a number of patient and provider factors, it is recommended that treatment options be considered in a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Supplementary Material

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors approved the final version of this manuscript. Andrew M. Moon is the guarantor of this paper. Andrew M. Moon: Study concept and design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript. Hannah P. Kim, Amit G. Singal, Dawn Owen, Mishal Mendiratta-Lala, Parikh, and Steven C. Rose: Study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript. Chris B. Agala: Statistical analysis and critical revision of the manuscript. All others: Data acquisition, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Takeshi Yokoo from the University of Texas-Southwestern for assistance with this project.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported in part by NIH grant T32 DK007634 (Andrew M. Moon, Hannah P. Kim), AASLD Advanced/Transplant Hepatology Grant from the AASLD Foundation (Andrew M. Moon) and AASLD Clinical, Translational and Outcomes Award from the AASLD Foundation (Andrew M. Moon). The authors acknowledge the assistance of the NC Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute, which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Amit G. Singal is a consultant or advisory boards for Genentech, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Bayer, Exelixis, FujiFilm Medical Sciences, Exact Sciences, Glycotest, GRAIL, Freenome, Universal Dx, and TARGET RWE. Andrew M. Moon is a consultant for TARGET RWE. David A. Gerber is a consultant for Medtronic. Dawn Owenreceived research funding (no salary support) from AstraZeneca and Varian. Honorarium from UptoDate. Michael R. Folkert received research funding (no salary support) from Boston Scientific, Inc. Neehar D. Parikh is a consultant or advisory boards for Fujifilm Medical Sciences, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Bayer, Exelixis, Exact Sciences, Freenome, and Gilead. Paul H. Hayashi: Dr. Hayashi is employed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but the opinions and conclusions in this paper do not reflect any opinions of the FDA. The FDA has not evaluated the opinions or conclusions in this paper. The remaining authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CPS, Child-Pugh score; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; IQR, interquartile range; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; mRECIST, modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; MWA, microwave ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Andrew M. Moon, Email: Andrew.Moon@unchealth.unc.edu.

Hannah P. Kim, Email: hannah.p.kim@vumc.org.

Amit G. Singal, Email: amit.singal@utsouthwestern.edu.

Dawn Owen, Email: owen.dawn@mayo.edu.

Mishal Mendiratta-Lala, Email: mmendira@med.umich.edu.

Neehar D. Parikh, Email: ndparikh@med.umich.edu.

Steven C. Rose, Email: scrose@ucsd.edu.

Katrina A. McGinty, Email: katrina_mcginty@med.unc.edu.

Chris B. Agala, Email: chris_agala@med.unc.edu.

Lauren M. Burke, Email: lauren_burke@med.unc.edu.

Anjelica Abate, Email: anabate@med.umich.edu.

Ersan Altun, Email: ersan_altun@med.unc.edu.

Christian Beyer, Email: christianbeyer22@gmail.com.

John Do, Email: jdo@health.ucsd.edu.

Michael R. Folkert, Email: mfolkert@northwell.edu.

Chalon Forbes, Email: chforbes@med.umich.edu.

Jona A. Hattangadi-Gluth, Email: jhattangadi@ucsd.edu.

Paul H. Hayashi, Email: paul.hayashi@fda.hhs.gov.

Keri Jones, Email: jokeri@med.umich.edu.

Gaurav Khatri, Email: gaurav.khatri@utsouthwestern.edu.

Yuko Kono, Email: ykono@ucsd.edu.

Theodore S. Lawrence, Email: tsl@umich.edu.

Christopher Maurino, Email: cmmaurino@gmail.com.

David M. Mauro, Email: david_mauro@med.unc.edu.

Charles S. Mayo, Email: cmayo@med.umich.edu.

Taemee Pak, Email: taemee.pak@utsouthwestern.edu.

Preethi Patil, Email: patilp@med.umich.edu.

Emily C. Sanders, Email: emily.sanders@duke.edu.

Daniel R. Simpson, Email: drsimpson@ucsd.edu.

Joel E. Tepper, Email: joel_tepper@med.unc.edu.

Diwash Thapa, Email: diwash_thapa@med.unc.edu.

Ted K. Yanagihara, Email: tky@email.unc.edu.

Kyle Wang, Email: wang2kl@ucmail.uc.edu.

David A. Gerber, Email: david_gerber@med.unc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moon AM, Singal AG, Tapper EB. Contemporary epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2650–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrick JL, Kelly SP, Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Rosenberg PS. Future of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in the United States Forecast Through 2030. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1787–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fabrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado A, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Yu XL, Han ZY, Cheng ZG, Liu FY, Zhai HY, et al. Percutaneous cooled-probe microwave versus radiofrequency ablation in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2017;66:1172–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vietti Violi N, Duran R, Guiu B, Cercueil JP, Aube C, Digklia A, et al. Efficacy of microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: a randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han J, Fan YC, Wang K. Radiofrequency ablation versus microwave ablation for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e22703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanker MD, Moodaley P, Soon W, Liu HY, Lee YY, Pryor DI. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of local control, survival and toxicity outcomes. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2021;65:956–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahl DR, Stenmark MH, Tao Y, Pollom EL, Caoili EM, Lawrence TS, et al. Outcomes after stereotactic body radiotherapy or radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan YX, Xi M, Fu YZ, Hu DD, Wang JC, Liu SL, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy as a salvage therapy after incomplete radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: A Retrospective Propensity Score Matching Study. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim N, Cheng J, Jung I, Liang J, Shih YL, Huang WY, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy vs. radiofrequency ablation in Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;73:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara K, Takeda A, Tsurugai Y, Saigusa Y, Sanuki N, Eriguchi T, et al. Radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma results in comparable survival to radiofrequency ablation: a propensity score analysis. Hepatology. 2019;69:2533–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navin PJ, Olson MC, Mendiratta-Lala M, Hallemeier CL, Torbenson MS, Venkatesh SK. Imaging features in the liver after stereotactic body radiation therapy. Radiographics. 2022;42:2131–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim N, Kim HJ, Won JY, Kim DY, Han KH, Jung I, et al. Retrospective analysis of stereotactic body radiation therapy efficacy over radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2019;131:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parikh ND, Marshall VD, Green M, Lawrence TS, Razumilava N, Owen D, et al. Effectiveness and cost of radiofrequency ablation and stereotactic body radiotherapy for treatment of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: An analysis of SEER-medicare. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2018;62:673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji R, Ng KK, Chen W, Yang W, Zhu H, Cheung TT, et al. Comparison of clinical outcome between stereotactic body radiotherapy and radiofrequency ablation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e28545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong Y, Lee KJ, Lee SJ, Shin YM, Kim MJ, Lim YS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus stereotactic body radiation therapy for small (</=3 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective comparison analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1962–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajyaguru DJ, Borgert AJ, Smith AL, Thomes RM, Conway PD, Halfdanarson TR, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized hepatocellular carcinoma in nonsurgically managed patients: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TH, Koh YH, Kim BH, Kim MJ, Lee JH, Park B, et al. Proton beam radiotherapy vs. radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomized phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2021;74:603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong AJ, Ghaziani TT, Yao F, Sze D, Mannalithara A, Mehta N. National trends and waitlist outcomes of locoregional therapy among liver transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1142–1150 e1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabrera R, Singal AG, Colombo M, Kelley RK, Lee H, Mospan AR, et al. A real-world observational cohort of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: design and rationale for TARGET-HCC. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:538–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apisarnthanarax S, Barry A, Cao M, Czito B, DeMatteo R, Drinane M, et al. External beam radiation therapy for primary liver cancers: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12:28–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moon AM, Sanoff HK, Chang Y, Lund JL, Barritt AS, Hayashi PH, et al. Medicare/Medicaid Insurance, Rurality, and Black Race associated with provision of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment and survival. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0. In; 2017.

- 27.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendiratta-Lala M, Masch W, Shankar PR, Hartman HE, Davenport MS, Schipper MJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy: Long term imaging follow-up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103:169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng CY, Harwell MR, Liou SM, Ehman LH.Sawilowsky SS. Advances in missing data methods and implications for educational research. Real Data Analysis. New York: Information Age Publishing Inc; 2006:31–78. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendiratta-Lala M, Aslam A, Maturen KE, Westerhoff M, Maurino C, Parikh ND, et al. LI-RADS treatment response algorithm: performance and diagnostic accuracy with radiologic-pathologic explant correlation in patients with SBRT-treated hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112:704–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson LA, Winter K, Knox J, Zhu AX, Krishnan S, Guha C, et al. NRG/RTOG 1112: Randomized Phase III Study of Sorafenib vs. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) Followed by Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) (NCT01730937). San Antonio, TX: American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Annual Meeting; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim N, Seong J. What role does locally ablative stereotactic body radiotherapy play versus radiofrequency ablation in localized hepatocellular carcinoma ? J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2560–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riaz A, Miller FH, Kulik LM, Nikolaidis P, Yaghmai V, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Imaging response in the primary index lesion and clinical outcomes following transarterial locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA. 2010;303:1062–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price TR, Perkins SM, Sandrasegaran K, Henderson MA, Maluccio MA, Zook JE, et al. Evaluation of response after stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3191–3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edeline J, Boucher E, Rolland Y, Vauleon E, Pracht M, Perrin C, et al. Comparison of tumor response by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and modified RECIST in patients treated with sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miften M, Vinogradskiy Y, Moiseenko V, Grimm J, Yorke E, Jackson A, et al. Radiation dose-volume effects for liver SBRT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110:196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]