Abstract

Rationale & Objective

COVID-19 disproportionately affects people with co-morbidities, including chronic kidney disease (CKD). The aim of this study was to describe the impact of COVID-19 on people with CKD and their caregivers.

Study Design

A systematic review of qualitative studies.

Setting & Study Populations

Primary studies that reported the experiences and perspectives of adults with CKD and/or caregivers were eligible.

Search Strategy & Sources

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL were searched from database inception to October 2022.

Data Extraction

Two authors independently screened the search results. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were assessed for eligibility. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with another author.

Analytical Approach

A thematic synthesis was used to analyze the data.

Results

Thirty-four studies involving 1962 participants were included. Four themes were identified: exacerbating vulnerability and distress (looming threat of COVID-19 infection, intensifying isolation, aggravating pressure on families); uncertainty in accessing health care (overwhelmed by disruption of care, confused by lack of reliable information, challenged by adapting to telehealth, skeptical about vaccine efficacy and safety); coping with self-management (waning fitness due to decreasing physical activity, diminishing ability to manage diet, difficulty managing fluid restrictions, minimized burden with telehealth, motivating confidence and autonomy); and strengthening sense of safety and support (protection from lockdown restrictions, increasing trust in care, strengthened family connection).

Limitations

Non-English studies were excluded and the inability to delineate themes based on stage of kidney and treatment modality.

Conclusions

Uncertainty in accessing health care during the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated vulnerability, emotional distress, and burden, and led to reduced capacity to self-manage among patients with CKD and their caregivers. Optimizing telehealth and access to educational and psychosocial support may improve self-management, and the quality and effectiveness of care during a pandemic, mitigating potentially catastrophic consequences in people with CKD.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, dialysis, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, renal transplantation, kidney replacement therapy, COVID-19, patient perspectives, qualitative research

Introduction

As of January 2023, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been estimated to have caused 6 million deaths worldwide (1). Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a five times greater risk of severe COVID-19 infection than the general population due to their immunosuppressed state and chronic systemic inflammation (2, 3). Patients with CKD requiring kidney replacement therapy who have COVID-19 infection have higher rates of admission to intensive care units, mechanical ventilation, and death (2, 4, 5).

Access to care for patients with CKD has been severely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic with rapid hospital repurposing, staff and resource shortages, transition to telehealth, infection outbreaks within dialysis units, and the suspension of medical procedures, including kidney transplantation (4, 6, 7, 8, 9). Ongoing barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccinations and uncertainty about the magnitude of the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in CKD have also been a concern (10). Collectively, these challenges may exacerbate distress and worsened outcomes experienced by patients with CKD.

However, perspectives of patients with CKD and caregivers on the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on their health and care is limited. We aimed to describe the experiences and perspectives of patients with CKD and caregivers on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their health and health care, to inform strategies for better patient-centered care, and to improve our preparedness, readiness, and response for future disruptions to care or to better cope with providing care/support in the post-pandemic era.

Methods

We followed the Enhancing Transparency of Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative research (ENTREQ) framework (11).

Selection criteria

Primary qualitative studies that reported the experiences and perspectives of patients aged over 18 years with any stage of CKD (including patients with CKD not receiving kidney replacement therapy, patients receiving dialysis, and kidney transplant recipients) and/or caregivers on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their health and healthcare were eligible. The scope of topics could include the perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and the impact of COVID-19 on their health and access to care (including but not limited to transplantation, telehealth, COVID-19 vaccination). Excluded studies were those that reported quantitative epidemiologic studies (e.g., randomized trials, cohort studies), nonprimary research articles, basic science studies, economic studies, quantitative surveys, or reported the perspective from health professionals. Also excluded were non-English articles to avoid misinterpretation of linguistic and cultural nuances, which may occur in translation.

Data sources and searches

The searches were conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL from database inception to 17th of October 2022 (Table S1). Google Scholar and PubMed were also searched. We checked reference lists of relevant reviews and included articles. Two authors (P.N., J.Z.) independently screened the search results and removed citations that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were assessed for eligibility. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with author A.J.

Appraisal of transparency of reporting

The transparency of reporting of each included primary study was assessed using an adapted Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) framework (12). Each paper was evaluated independently by three authors (P.N., J.Z., N.S.). Disagreements were addressed by discussion with another author (A.J.).

Data Analysis

Thematic synthesis was used to inductively identify concepts (13). All text and participant quotations from each study's 'results' or 'conclusion/discussion' section were extracted. Two reviewers (P.N., J.Z.) coded the data line by line by using HyperRESEARCH software version 4.5.3, and inductively identified preliminary themes and subthemes that captured the experiences and perspectives of patients with CKD and their caregivers on COVID-19 pandemic. We coded the text from each study into these concepts, creating new concepts as needed, and then categorized similar concepts into broader themes. Investigator triangulation was achieved by discussing the preliminary themes with a third author (A.J.) to ensure the findings captured the full range and depth of the data. We developed an analytical thematic schema to identified conceptual patterns and links among the themes.

Results

Literature search

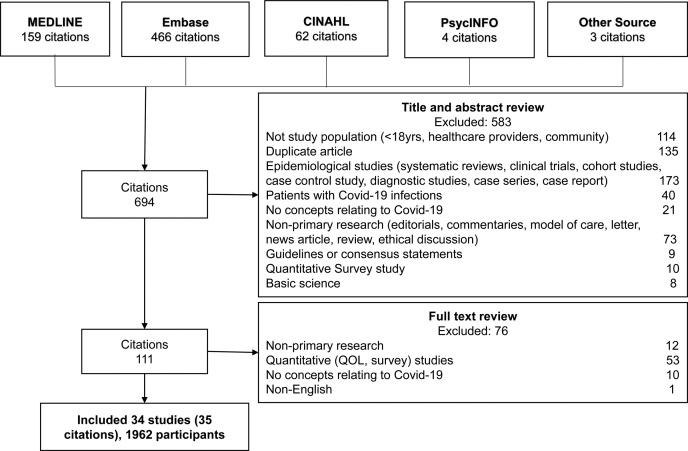

We included 34 studies involving 1962 adult participants (five studies did not specify the number of participants), including 1595 patients with CKD (including non-dialysis (n= 262), patients receiving dialysis (n= 223), kidney transplant recipients (n= 656)), and 327 caregivers, whilst five studies did not clearly report CKD stages or included both patients with CKD and caregivers (Figure 1 ). The studies were conducted across 11 countries: Australia, Canada, India, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, United Kingdom, United States. Twenty-four (70%) studies conducted semi-structured or in-depth interviews, eight (24%) used a survey including open-end questions, and two (6%) used focus groups. Ten (30%) studies were reported as abstract only. The participant and study characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1 .

Figure 1.

Search results of studies reporting the impact of COVID-19 in CKD

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies reporting the impact of COVID-19 in CKD

| Study ID | Country | N patients | N caregivers | Kidney Disease Stage |

Population | Age (years) | Methodological framework | Data collection | Data Analysis | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antoun 2021 (23) | UK | 20 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | >18 | Phenomenology | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences with telehealth |

| Arevalo Iraheta 2021 * (48) | US | 111 | - | Tx | Transplant recipients | Not stated | Mixed method | Open and closed-ended questions | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences |

| Arevalo Iraheta 2022 (17) | US | Not stated only for people with CKD | - | HD and TX | Dialysis and kidney transplant patients | 54.5 | Mixed method | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences; economic issues |

| Beaudet 2022 (16) | Canada | 28 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | 40-99 | Mixed method | Open and closed-ended questions | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences |

| Bonenkamp 2021 (49) | Netherlands | Not stated | - | HD and PD | Dialysis patients | >18 | Mixed method | Open and closed-ended questions | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences |

| Cuevas-Budhart 2022 (20) | Mexico | 29 | - | PD | Dialysis patients | 45±17 | Phenomenology | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences with telehealth; skepticism about the infection |

| Danton 2022 (15) | UK | 14 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | >30 | Qualitative research | Semi-structured telephone or videocall interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences |

| Davis 2022 (32) | Canada | 40 (overall, including both patients and caregivers) | HD and PD | Home dialysis patients and caregivers | 53±12 | Mixed method | Open and closed-ended questions | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences with home dialysis | |

| Figueiredo 2021 * (50) | Portugal | 9 | 9 | HD | Dialysis patients | Patients: 65±13; caregivers: 52±19 | Qualitative research | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences |

| Fortin 2021 * (51) | Canada | 20 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | Not stated | Qualitative research | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences with telehealth |

| Gordon 2022 * (52) | US | 26 | - | Tx | Transplant recipient | Not stated | Qualitative research | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences; racial stigmatization |

| Guha 2021 (22) | Australia | 22 | 4 | Tx | Transplant recipients, caregiver and potential donors |

>18 | Qualitative research | Online focus group | Thematic analysis | Perspectives on the suspension and resumption of kidney transplant programs |

| Haokip 2020 (53) | India | 1 | - | Tx | Transplant recipient | 40 years old | Qualitative case report | Phone interviews | Not stated | Psychosocial impacts |

| Heyck Lee 2022 (26) | Canada | 234 | - | CKD | CKD patients | >35 | Mixed method | Telephone open-ended questions | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences with telehealth |

| Huuskes 2021 (27) | Australia | 34 | - | Tx | Transplant recipients | >18 | Qualitative research | Online focus group | Thematic analysis | Telehealth |

| John 2021 * (54) | India | Not stated only for people included in the qualitative analysis | - | CKD | All stages of CKD patients (including ESKD) | 46±13 | Mixed method | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences with telehealth |

| Kanavaki 2021 * (55) |

UK | 230 | 67 | CKD (non-dialysis) | Non-dialysis patients and caregivers | Patients: 64±14; caregivers: not stated | Mixed method | Survey with open-ended responses | Not stated | Perspectives on support needed during Covid-19 |

| Lunney 2021 (56) | Canada | 8 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | 38-72 | Mixed method | Video interview | Not stated | Virtual clinic |

| Malo 2022 (21) | Canada | 22 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | 61±17 | Qualitative Research | Semi-structured telephone or videoconference interview | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences |

| McKeaveney 2021 (25) | UK | 44 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | >25 | Mixed method | Survey with open-ended responses | Thematic analysis | Psychosocial well-being |

| McKeaveney 2022 (57) | UK | 23 | - | Tx | Transplant recipients | 49 (mean) | Phenomenology | Semi-structured telephone or videoconference interviews | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences |

| Ng 2021 * (58) | US | 28 | 14 | CKD and caregivers | CKD (stages 4-5 including transplant recipients) and caregivers | >18 | Qualitative Research | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences with telehealth |

| Porteny 2021 and Porteny 2022 ˆ (24, 59) | US | 39 | 17 | CKD and caregivers | CKD (stages 4-5, including dialysis) and caregivers | Patients:>70; caregivers: >40 | Qualitative Research | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences |

| Rivera 2021 * (60) | US | 32 | - | CKD (non-dialysis) | CKD stages 1-4 | >45 (mean 67) | Mixed method | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Impact of COVID-19 |

| Schmidt 2021 * (61) | US | 12 | - | ESKD | Dialysis patients | 56±14 | Ethnographic | Semi-structured remote interview | Grounded theory and dimensional narrative analysis | Impact of COVID-19; experiences; economic issues; racial stigmatization |

| Sousa 2021 (18) | Portugal | 20 | - | HD | Dialysis patients | 67±12 | Qualitative Research | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Impact treatment related; health behaviors |

| Sousa 2022 (14) | Portugal | - | 19 | HD | Caregivers | 51±14 | Mixed method | Semi-structured phone interview | Thematic analysis | Experiences of family caregivers |

| Tsapepas 2021 (28) | US | 320 | - | Tx | Transplant recipients | >18 | Qualitative summary | Semi-structured phone interview | Not stated | Perspective on COVID-19 vaccination |

| Tse 2021 (19) | UK | 78 | 197 | Long-term kidney conditions | Young adults with CKD and caregivers | Patients: 18-30 caregivers: 21-60 | Mixed methods | Survey qualitative and video conference focus groups | Thematic analysis | Experience and support needs |

| Valson 2022 (31) | India | 9 | - | HD | HD patients | >18 | Mixed method | Semi-structured in-depth interview | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences |

| Van Zanten 2021 * (62) |

Italy | 153 | - | Tx | Transplant recipients | Not stated | Observational | Interview and follow up online questionnaires | Not stated | COVID-19 impact on daily lives, emotions and behaviors |

| Varsi 2021 (63) | Norway | 15 | - | Tx | Transplant recipients | 37–64 (mean 53) | Qualitative summary | Semi-structured interview | Thematic analysis | Telehealth (limited concepts related to the telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic) |

| Wang 2022 (29) | US | - | Not stated only for parent of children with CKD | Caregivers | Parents of children with kidney disease (kidney transplant, kidney failure treated by dialysis, or with CKD) | >18 | Mixed method | Semi-structured in-depth interview | Thematic analysis | COVID-19 vaccine |

| Yoon 2023 (30) | Singapore | 14 | - | Patients with CKD | CKD patients | >21 | Mixed method | Opened-ended questions (phone or online) | Thematic analysis | Impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions; experiences |

Abbreviations and definitions: UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; HD, hemodialysis; Tx, transplant; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; * abstract only; ˆ two publications have been published

Comprehensiveness of reporting

The completeness of reporting was variable, with studies reporting from one to 23 of the 32 COREQ items (Table S2, Table S3). The study sample was described in 33 (97%) studies and quotations were provided in 22 (65%) studies. Audio-recording and field notes was reported in 19 (56%) and eight (24%) studies, respectively. Data saturation was reported in 11 (32%) studies.

Synthesis

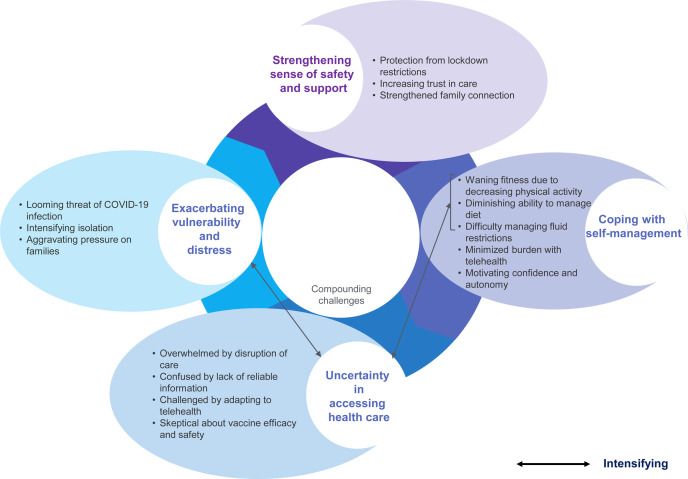

We identified four themes: exacerbating vulnerability and distress; uncertainty in accessing healthcare; coping with self-management; and strengthening sense of safety and support. Themes specific to a population or setting were described accordingly (Table S4). Selected participant quotations that exemplified the themes are provided in Box 1 . The conceptual relationship among the themes is depicted in Figure 2 .

Box 1. Illustrative quotations in included studies reporting the impact of COVID-19 in CKD.

Exacerbating vulnerability and distress

Looming threat of Covid-19 infection* 14-25, 27, 30, 31, 49, 50, 53, 57

“I would be concerned about going into hospital because I’ve heard a few stories of people going in and actually catching [COVID-19] it in hospital”. [patient, United Kingdom] (23)

“My greatest concern is that, if I get infected, I have very little chances of surviving.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

“Everybody touches the same scale, everybody uses the same washroom, everyone uses the same waiting room, so I don’t think that’s very effective.” [patient, Canada] (21)

Intensifying isolation* 15, 17-21, 23-25, 49, 53, 57-59, 61

“I’m alone. When the virus got here, my wife and kids went to my mother-in-law’s. As I am at high-risk of getting contaminated. I’m afraid of getting infected by the virus and contaminated my kids. The most difficult part is not having my family with me.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

“The new disease makes me feel bad because it changed my life completely. I feel as if I was in a jail, always doing the same thing, it gives me a lot of nerves and I feel very anxious because I cannot do anything. I feel desperate, imprisoned.” [patient, Mexico] (20)

“The beds are further apart. So that makes conversation an obstacle, and we are not grouping up in the waiting area before and after shift.” [patient, United Kingdom] (15)

Aggravating pressure on families* 14, 17, 19-22, 31, 49-51, 53, 58

“I strictly follow wearing of mask and social distancing. I was most worried about whether I’ll become sick in the night. What will my father do? I should not be a burden for him.” [patient, India] (31)

“I took leave from my job for kidney transplant and now I’m stuck here … have to get dialysis three times a week ... not sure whether I’ll be able to continue in the job. My wife who's working as teacher in a private school is getting only half pay due to lockdown. My parents are supporting us financially. We’re very much affected!” [patient, India] (31)

“[Quarantine] doesn’t just affect me, it affects my children. So, it affects everybody because I need to quarantine, everybody else who lives with me has to do the same.” [patient, United States] (17)

Uncertainty in accessing healthcare

Overwhelmed by disruption of care* 14-25, 31, 52, 53, 60

“All our nephrology appointments have been cancelled over here. We have a doctor come in once a fortnight. So, I haven’t really seen a nephrologist since this happened.” [patient, Australia] (22)

“The fact we had a transplant planned which was cancelled due to the virus has not been a wonderful experience.” [caregiver, United Kingdom] (19)

“We were cut down to two days a week. That didn’t work at all. And so, a lot of us started to show fairly serious problems, mainly around potassium.” [patient, United Kingdom] (15)

Confused by lack of reliable information* 16-20, 22-25, 50, 52, 53, 59

“Just find it inconsistent and frustrating sometimes ... You’ve talked to the different doctors, and you’ve all got different opinions and that’s great. But to have someone that you trust is important to me.” [patient, Australia] (22)

“I feel at the beginning we got very little information from the hospital. I have taken all my advice so far from the shielding government advice however, I would like to see more specific advice relating to post transplant patients.” [caregiver, United Kingdom] (19)

“The lack of resources that are available for people with organ transplants. It drove me to call [the listening center] because I’ve been feeling like I’ve been left in the dark.” [patient, United States] (17)

Challenged by adapting to telehealth 22-24, 26, 27, 30, 56

“The focus has been on the patient side and getting telehealth up and running, but less on the clinician training side of things and making sure that they understand what makes a good telehealth consult.” [patient, Australia] (27)

“I like the in-person visits because sometimes you have to show a concern to the physician that isn’t easy to explain over the phone.” [patient, Canada] (26)

Skeptical about vaccine efficacy and safety 17, 28, 29

“A belief that there was a lack of data about the vaccines in transplant recipients.” [patient, United States] (28)

“Her age group doesn’t seem to suffer from the COVID disease that much. So, I wouldn’t give it to her, if I had the choice at this moment. I don’t think her kidney disease would be a reason to get the vaccine, from what I’ve read.” [caregiver, United States] (29)

“I would want to know if it’s safe for them. Like, are they going to make a different batch for children. What’re the side-effects? How is it going to affect her with her disease.” [caregiver, United States] (29)

Coping with self-management

Waning fitness due to decreasing physical activity 18, 20, 23, 30

“Oh, well yes they [physical activity levels] have gone down quite a lot obviously.” patient, United Kingdom] (23)

“My physical activity was walking, and, in the house, there isn’t a lot of walking that you can do.” [patient, United Kingdom] (23)

“I used to exercise during dialysis. Now that's gone. Physically, I was more stable, more secure. Losing the exercise during dialysis is one of the things that costs me the most. I used to leave dialysis feeling good and dynamic. Now I feel weak and tired.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

Diminishing ability to manage diet* 14, 18-20, 31, 58

“Sometimes there are certain foods that are missing at home. Sometimes I could have more variety in what I eat and that would be healthier, with more vitamins. My meals became more monotonous.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

“Extremely difficult to access delivery for food/medicines/essentials due to our rural location.” [caregiver, United Kingdom] (19)

“I can't go anywhere. I can't even buy my own groceries. My son doesn't want me to go out. That, for me, since I’m a very independent person, it's bad. Sometimes, he doesn't bring me the same things, the things that I’m used to.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

Difficulty managing fluid restrictions* 18, 31, 58

“Anxiety makes my mouth dry! I sip on the water and throw it away. I just swallow a little bit.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

“The difficulty was in restricting water intake. I used to drink more water when I was getting thrice weekly dialysis. With two dialysis sessions I reduced my water intake to half which was very difficult!” [patient, India] (31)

“It was hard… It's very hot… I want to drink more water, but I have to control because I am coming for dialysis only twice a week. It was very difficult to manage. [patient, India] (31)

Minimized burden with telehealth* 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 51, 56, 58, 59, 63

“The great benefit that I have, is that if I have any problem regarding my dialysis, I no longer have to take the machine, nor go to the hospital is too far away for me or involves an expense. With the simple fact of notifying my nephrologist or the nurse, they come up with a solution for me.” [patient, Mexico] (20)

“I like I didn’t have to come to hospital during the pandemic, saved parking fees and worrying if the weather was going to be bad as I live 25 miles away.” [patient, Canada] (26)

“Now [with telehealth] it’s very convenient for me because I can even take calls while I’m working.” [patient, Australia] (27)

Motivating confidence and autonomy 15, 18, 20, 22-24, 27, 31, 32, 57, 59

“I looked at it [my wound], it was just getting worse and worse, so I had to go and see [the doctor], just to make sure that the medication that were taking was killing the infection that I had.” [patient, Australia] (27)

“I’m aware of my vulnerability, I am extremely careful about going out.” [patient, United States] (24)

Strengthening sense of safety and support

Protection from lockdown restrictions* 14, 15, 18-21, 23-25, 50, 58, 59, 63

“I know that I’m a patient at risk and, therefore, I take my precautions. I always leave my slippers outside. And when I get home from dialysis, I throw the mask away and wash my hands right away. I wash my hands with soap. When I get home, I take my clothes off and put them to wash. And here at home, I’m careful and I disinfect the places where I put my hands.” [patient, Portugal] (18)

“It’s good for newer generations: It’s showing good and hygienic habits to maintain.” [patient, Canada] (21)

“[I’m] very enthusiastic about what’s happening in that unit.” [patient, Canada] (21)

Increasing trust in care* 15, 19-21, 23, 24, 26, 58

“Since the COVID-19 lockdown, I have had more support than before. I mean, before the support was always there available but now it is more proactive where I actually get called.” [patient, United Kingdom] (23)

“I have absolute trust in my daughter’s consultant and have been reassured that she is not at risk because of having kidney disease.” [caregivers, United Kingdom] (19)

“The nurses are excellent. There’s a lot of banter and good humor, which helps.” [patient, United Kingdom] (15)

Strengthened family connection* 14, 17, 20-24, 32, 50, 51, 60

“I have more contact with my daughter through the cell phone now then what I used to before COVID. My son-in-law came here to deliver some facemasks and asked if I needed anything too. We became closer now.” [patient, Portugal] (14)

“That’s the best thing. Having the support of the family.” [patient, Australia] (22)

“That “in terms of helping each other, going to help neighbors, making some- thing to eat then bringing it next door … stopped to think that everything is a given.” [patient, Canada] (21)

*The subtheme was reported in both studies reported as full text and in conference abstract.

Figure 2.

Thematic schema of studies reporting the impact of COVID-19 in CKD

Exacerbating vulnerability and distress

Looming threat of COVID-19 infection (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients and caregivers were concerned about their heightened risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection, particularly in hospital settings – “The fact that my mother has to leave the house three times a week to go to dialysis and travel in an ambulance with other people [or] she needs to be at the dialysis centre with several patients to perform treatment … People that might be infected. This is a big concern” (Portugal) (14). Patients receiving dialysis and kidney transplant recipients felt particularly vulnerable because of their comorbidities and immunocompromised state. Patients questioned whether vehicles used to transport them to dialysis were adequately sanitized and reported that drivers did not wear masks appropriately. In dialysis units, patients felt vulnerable if they observed inadequacies in infection control procedures – “[Doctors] should be enforcement and the nurses are not even trying, not even saying to patients: ‘Please put your mask back on!’” (United Kingdom) (15). Patients felt anxious and preferred to “stay indoors as much as possible” (Canada) (16) because “it’s not safe anywhere you want to go” (United States) (17). Patients strived to protect themselves and were “more careful with hygiene” (Portugal) (18), or were worried about being infected with COVID-19 from family members – “My main worry is about my family who have to go to the shops or still work to bring me and my grandparents' food” (United Kingdom) (19).

Intensifying isolation (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients with CKD felt “caged” (20), lonely, and abandoned because of forced isolation and having to refrain from physical interaction – “The most difficult part is not having my family with me” (Portugal) (18). Some patients engaged in online communication but “it is not the same because when the video call ends, I am alone again” (Mexico) (20). Patients in dialysis units felt “down” (Canada) (21) as they could not interact with their peers or clinicians – “The beds are further apart. So that makes conversation an obstacle. And we are not grouping up in the waiting area” (United Kingdom) (15). Some patients receiving dialysis remarked that the isolation and discontinuation of social activities worsened their depressive symptoms and that they felt “not useful” (Mexico) (20).

Aggravating pressure on families (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Due to lockdown restrictions, families and caregivers took on more responsibilities (e.g., grocery shopping) as patients remained at home to minimize their risk of COVID-19, or had to provide alternate transportation for the patient to the dialysis unit – “I also transport [my father] to and from dialysis because he would take the bus to go to treatment [before COVID-19]” (Portugal) (14). Lockdowns negatively impacted patients’ ability to work outside the home and they were forced to depend on financial support from family members.

Uncertainty in accessing healthcare

Overwhelmed by disruption of care: (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients were “desperately” (Mexico) (20) concerned about missing the opportunity of receiving a kidney transplant – “I was devastated. [Transplant] is where I’m putting all my hopes” (Australia) (22). Patients on dialysis had to “relocate dialysis sessions without early notice” (23), or felt frustrated because “all of our nephrology appointments have been cancelled, they are not doing even telehealth, only one doctor come in once a fortnight to once a month” (Australia) (22). Others were stressed about being unable to obtain dialysis supplies (e.g., fluids for home dialysis). Others were worried as they could not monitor their laboratory results to manage and prevent serious complications (e.g., hyperkalemia). Elderly patients and Indigenous patients felt unable to advocate for themselves without their family or support persons present during clinical appointments due to COVID-19 restrictions because they could not communicate or had limited capacity to understand clinicians due to language barriers. Caregivers felt excluded from decision making because interactions with health providers were limited during the COVID-19 pandemic – “We have [discussed advanced care planning with doctors] in the past, but not now” (United States) (24).

Confused by lack of reliable information (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients and caregivers noted that “there is deathly silence” (Australia) (22) and “a lack of communication about COVID-19 rules for patients with CKD from the healthcare professionals” (United Kingdom) (19). They reported receiving “inconsistent” (United Kingdom) (25) information on COVID safety guidance, which led to confusion and loss of confidence in their clinicians – “Having someone that you trust is really important. I find it hard when I’m hearing so many different advice from different nephrologists” (Australia) (22). Some kidney transplant recipients felt they “have been left in the dark” (United States) (17) and requested “more specific information” (United Kingdom) (19) on shielding and hygiene.

Challenged by adapting to telehealth (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

With rapid transitions to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, some patients missed the in-person interaction and reported that “medical phone conservations tend to be one sided and vague” (Canada) (26). Kidney transplant recipients encountered technical difficulties, and felt ill-prepared for their first telehealth appointment, for example having to “take their own measurements” (Australia) (27). Others believed that their doctors went through a “learning curve” (Australia) (27) and were unfamiliar with technology. Patients who were older, had language difficulties, or had visual or hearing impairments struggled with telehealth.

Skeptical about vaccine efficacy and safety (caregivers, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Kidney transplant recipients and caregivers were worried about their eligibility or potential harms of the COVID-19 vaccine and the uncertainties due to the perceived “lack of data about COVID-19 vaccination” (United States) (28). Some patients did not trust “the scientific process underlying the development of the COVID-19 vaccine” (United States) (28), and were worried about “potential interactions with other medications” (United States) (28). Caregivers where uncertain that the COVID-19 vaccine would be effective in children with CKD – “I’ve heard that children that get COVID-19 with kidney disease and children that get COVID-19 without kidney disease tolerate it the same way. So, I don’t think her kidney disease would be a reason to get the vaccine” (United States) (29).

Coping with self-management

Waning fitness due to decreasing physical activity (non-dialysis, dialysis)

Patients receiving dialysis had to reduce their physical activity due to the lockdown and fear of COVID-19 infection – “There’s not a lot of walking that I can do in the house” (United Kingdom) (23). Some dialysis units suspended exercise programs and patients reported “decreased physical muscular strength, resistance, and energy” (Portugal) (18) and they “felt weak[er] and tired” (Portugal) (18) after dialysis. Patients with CKD noted that mask-wearing interfered with exercise – “We have to wear masks [and] breathing is really difficult” (Singapore) (30).

Diminishing ability to manage diet (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis)

Patients receiving dialysis and caregivers found it more challenging to prepare meals because of increased costs of food during lockdown, and patients increased their consumption of “banned food such as bread and dairy products” (Portugal) (18). Patients receiving dialysis could not adhere to nutritional recommendations, either because they were “no longer responsible for grocery shopping” (Portugal) (18) or because they had no “money for my food and my care” (Mexico) (20). Caregivers living in rural areas noted that it was “extremely difficult to access delivery for food/medicines/essentials due to our rural location and have become reliant on charitable help” (United Kingdom) (19).

Difficulty managing fluid restrictions (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis)

Patients receiving dialysis reported increased thirst because of anxiety triggered by concerns about COVID-19 – “My anxiety makes me thirsty” (Portugal) (18). They felt more overwhelmed by fluid restrictions because of reduced dialysis sessions – “I used to drink more water when I was getting thrice weekly dialysis. With two dialysis sessions I reduced my water intake to half” (India) (31).

Minimized burden with telehealth: (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Telehealth appointments enabled some patients to spend more time with their family and to carry out work responsibilities because it reduced the travel and waiting time to hospitals – “I could even take call while I’m working in the office or at home” (Australia) (27). For patients receiving dialysis from rural areas, telehealth reduced financial burdens by “saving a lot on petrol and hospital parking costs” (Australia) (27). Patients felt safer using telehealth as they minimized infection in the “clinic waiting room with other immunosuppressed patients” (Australia) (27).

Motivating confidence and autonomy (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients felt confident in self-management and felt “good” (Australia) (27) in having to take more responsibility for their own health; they believed that telehealth during COVID-19 made them more independent with “no need to rely on families to take [patients] to appointments” (Australia) (27) or “continue working during a period of potential economic instability” (Canada) (32).

Strengthening sense of safety and support

Protection from lockdown restrictions (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients with CKD and caregivers felt the hospital had become “a safer place” (United States) (24) during the pandemic with increased vigilance in infection control – “Throwing the mask away and washing [their] hands right away after finishing dialysis” (United Kingdom) (23). Other patients preferred having more control in doing home dialysis as they could “maintain my standard of sanitariness” (United States) (24).

Increasing trust in care (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis)

Patients receiving dialysis and caregivers felt reassured in receiving consistent and proactive care from clinicians and felt they received “a bit more support than before” (United Kingdom) (23), and trusted doctors’ instructions in preventing the spread of COVID-19 – “I have been reassured that [my daughter] is not at risk because of having kidney disease” (United Kingdom) (19). Others were “impressed” (United Kingdom) (19) with the new measures in place to control infection (e.g., plastic screens, regular temperature checks) and appreciated clinicians who made the effort to adopt new policies and practices.

Strengthened family connection (caregivers, non-dialysis, dialysis, kidney transplant)

Patients receiving dialysis and caregivers felt they had improved solidarity and social support during the COVID-19 pandemic and became much “closer” (Portugal) (14) with their family – “In this critical time of COVID I think it’s where families step in. And you can’t do kidney disease as an island, it’s got to be a community, and all of your relatives” (Australia) (22). Some used technology to remain connected with their families – “We talk with my daughter and see her through the cell phone, and I can see that they are alright” (Portugal) (14).

Discussion

The risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection was a constant threat for patients with CKD who were wary of attending clinic and interacting with family members, which exacerbated their sense of loneliness and isolation. Uncertainty in accessing healthcare, including dialysis, and reduced interaction with clinicians exacerbated vulnerability, emotional distress, and burdens in patients and caregivers. Some patients and caregivers were confused by inconsistent information, and worried about the potential harms or lack of efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients with CKD. Patients believed that COVID-19 had repercussions on their health as their physical activity was limited, or they were unable to adhere to dietary and fluid restrictions due to financial, logistical, and mental reasons. Patients receiving dialysis were particularly concerned regarding lost or delayed opportunities to receive a kidney transplant. For some patients, telehealth minimized the burden of attending clinic appointments and increased their confidence in self-management. Others believed that the hospital was safer due to the new policies and practices for infection control. Some patients and caregivers noted strengthened family support, which helped patients manage their health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While many of the themes were similar across the studies conducted in different populations and settings, there were apparent differences in perspectives based on whether they were patients or caregivers, CKD treatment stage, age, and geographical setting. Caregivers reported increased responsibilities for patients (e.g., grocery shopping, transport) and felt excluded from clinical consultations and decision making due to limited interaction with clinicians. Patients receiving dialysis felt frustrated and vulnerable when infection control procedures were not complied by clinicians and were concerned about the risk of acquiring infection when being transported to the dialysis unit. Some felt vulnerable and were worried about their health as they could not receive regular laboratory results, had reduced dialysis sessions, were unable to adhere to physical activity, nutritional and fluid recommendations, and felt they missed an opportunity to receive a kidney transplant. Kidney transplant recipients and caregivers expressed concerns about the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines. Older patients, those with language difficulties and hearing and visual impairment, who were unable to attend appointments with a support person, found it more difficult to communicate with clinicians. Patients in rural areas felt that telehealth reduced the travel and financial burden of attending appointments.

The challenges and concerns regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic identified in this study have also been reported among people with other health conditions including cancer and other solid organ transplantation patients. They have consistently expressed constant worry and anxiety about being infected with COVID-19 and exercised extreme vigilance in self isolation (33, 34). Heart and lung transplant recipients believed that COVID-19 could threaten the survival of the graft (35). Patients with cancer also encountered multiple barriers in accessing health care, with examinations and surgeries being postponed (36, 37, 38). Patients requiring surgery felt they were unable to maintain their health, e.g., because of their reduced capacity to exercise, believed they did not receive adequate information, and experienced financial strain (39). Hesitancy and confusion about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines have also been documented in patients with cancer (40). Clinicians have also observed that the disruption to routine care and transition to telehealth consultations impaired mental health in patients with other clinical conditions, including diabetes and hypertension (41).

Our study generated a broad range of insights from patients with chronic kidney disease and their caregivers regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted a comprehensive search, assessed the transparency of study reporting, and used an explicit framework to assess and synthesize the findings. We used investigator triangulation to ensure that we captured the breadth and depth of data across the included studies. However, our study has some potential limitations. We only included studies published in English, and most studies were conducted in high-income countries, which may limit the transferability of our findings. Most of the studies were conducted in patients receiving hemodialysis or in kidney transplant recipients, and the perspectives of patients receiving peritoneal dialysis and caregivers were limited due to the lack of qualitative studies in these populations. It was not always possible to delineate perspectives by stage of CKD, treatment modality, or by patients and caregivers’ perceptions as these were not specified in the studies. Only three studies reported patient perspectives on the COVID-19 vaccination (17, 28, 29), of which two studies were conducted after the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination roll out (28, 29). The studies found that some patients were uncertain about their eligibility for COVID-19 vaccine, some were hesitant about receiving the COVID-19 vaccination due to uncertainty in long-term side effects, rapid development of the vaccine, and some patients were confused by conflicting information (17, 28, 29). We were unable to ascertain if there were differences in patients’ perspectives of their health risk based on the availability or type of the vaccines or among different CKD treatment stage is uncertain.

Our findings have implications for better managing the impact of pandemics on the health and health care of patients with CKD, including more consistency in information and communication, psychosocial support, optimization of telehealth consultations, and novel self-management programs. We suggest the provision of detailed information regarding safety and infection control procedures, policies, and processes for accessing health care (including dialysis and kidney transplant), and COVID-19 vaccines in a consistent manner. Tailored educational interventions may assist patients in resolving emotional distress associated with COVID-19 by addressing their specific concerns about symptom monitoring, social distancing, self-isolation, and vaccination roll out (42). Patients and caregivers may also require specific counselling or psychological services to manage anxiety, fears and burdens, e.g., regarding isolation and deterioration in health, as well as social or financial support (43, 44). The continued use of telehealth could alleviate travel and cost burdens; however, it should be optimized for patients, including those who have lower digital literacy, or have disabilities or language barriers (45). Attention should also be given to developing self-management interventions that can be implemented, for example through mobile applications which address lifestyle changes that could be feasibly accomplished during a pandemic. Virtual dietitian interventions have shown improved clinical and nutritional parameters in patients receiving hemodialysis, such as hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia (46).

With the changes in pandemic-related policies, we suggest ongoing studies are needed on patient and caregiver perspectives to capture the recent transitions in care during the pandemic, including views about COVID-19 vaccination to inform shared decision-making. The development and evaluation of telehealth strategies and interventions, particularly among patients in socially disadvantaged circumstances, could inform models of care during and after the pandemic. Also, the ongoing psychosocial impact of COVID-19 has been identified as a high priority research question by patients, caregivers and health professionals (47), which is also relevant for patients with CKD with the COVID-19 pandemic compounding their distress and burden.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with CKD and their caregivers experienced emotional distress, uncertainty, increased burden, deterioration in their health and wellbeing because of isolation, disruption, and barriers in accessing healthcare, limited interaction with clinicians, and reduced social support. Models of care with optimization of telehealth, educational and psychosocial support interventions may improve self-management, health, and psychological outcomes for patients with CKD during such pandemics.

Footnotes

Registration: Study not registered.

Plain Language Summary

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) faced barriers and challenges in accessing care and were at an increased risk of worse health outcomes. To understand the perspectives about the impact of COVID-19 among patients with CKD and their caregivers, we conducted a systematic review of 34 studies, involving 1962 participants. Our findings demonstrated that uncertainty in accessing care exacerbated vulnerability, distress, and burden, and impaired abilities for self-management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Optimizing the use of telehealth and providing education and psychosocial services may mitigate the potential consequences among people with CKD during a pandemic.

Article Information

Authors’ Contributions: Research idea and study design: all authors; data acquisition: P.N., J.Z., N.S.R.; data analysis/interpretation: all authors; supervision or mentorship: G.W., A.J. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: A.J. is supported by The University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship and the National Health and Medical Council Investigator Award (APP1197324). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Data Sharing: Data are available from the corresponding author.

Peer Review: Received February 13, 2023. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form April 11, 2023.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.D’Marco L., Puchades M.J., Romero-Parra M., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(3):297–306. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon T., Gandhi S.A.Q., Tariq W., et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cureus. 2021 Apr 3;13(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.14279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danziger-Isakov L., Blumberg E.A., Manuel O., Sester M. Impact of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021 Mar;21(3):925–937. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Divyaveer S., Jha V. COVID-19 and care for patients with chronic kidney disease: Challenges and lessons. FASEB Bioadv. 2021 Apr 29;3(8):569–576. doi: 10.1096/fba.2021-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabb H. Kidney diseases in the time of COVID-19: major challenges to patient care. J Clin Invest. 2020 Jun 1;130(6):2749–2751. doi: 10.1172/JCI138871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintaliani G., Reboldi G., Di Napoli A., et al. Exposure to novel coronavirus in patients on renal replacement therapy during the exponential phase of COVID-19 pandemic: survey of the Italian Society of Nephrology. J Nephrol Aug. 2020;33(4):725–736. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00794-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao R, Qing Z, Xu H, Shen Q. A narrative review of care for patients on maintenance kidney replacement therapy during the COVID-19 era. Pediatric Med. 2021 May 28;4:15. http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pm-20-101.

- 9.Mahalingasivam V., Su G., Iwagami M., Davids M.R., Wetmore J.B., Nitsch D. COVID-19 and kidney disease: insights from epidemiology to inform clinical practice. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022 Aug;18(8):485–498. doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00570-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens K.I., Frangou E., Shin J.I.L., et al. Immunonephrology Working Group (IWG) of the European Renal Association (ERA) and the European Vasculitis Society (EUVAS). Perspective on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with immune-mediated kidney diseases: consensus statements from the ERA-IWG and EUVAS. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022 Jul 26;37(8):1400–1410. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong A., Flemming K., McInnes E., Oliver S., Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012 Nov 27;12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qal Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008 Jul 10;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sousa H., Frontini R., Ribeiro O., et al. Caring for patients with end-stage renal disease during COVID-19 lockdown: What (additional) challenges to family caregivers? Scand J Caring Sci. 2022 Mar;36(1):215–224. doi: 10.1111/scs.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danton I.K.R., Elander J., Louth C., Selby N.M., Taal M.W., Stalker C., Mitchell K. 'I didn't have any option': experiences of people receiving in-centre haemodialysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Kidney Care. 2022;7(3):112–119. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaudet M., Ravensbergen L., DeWeese J., et al. Accessing hemodialysis clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. 2022 Mar;13 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2021.100533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arevalo Iraheta Y.A., Murillo A.L., Ho E.W., et al. Stressors and Information-Seeking by Dialysis and Transplant Patients During COVID-19, Reported on a Telephone Hotline: A Mixed-Methods Study. Kidney Med. 2022 Jul;4(7) doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2022.100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sousa H., Ribeiro O., Costa E., et al. Being on haemodialysis during the COVID-19 outbreak: A mixed-methods' study exploring the impacts on dialysis adequacy, analytical data, and patients' experiences. Semin Dial. 2021 Jan;34(1):66–76. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tse Y., Darlington A.E., Tyerman K., et al. COVID-19: experiences of lockdown and support needs in children and young adults with kidney conditions. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021 Sep;36(9):2797–2810. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-5041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuevas-Budhart M.A., Celaya Pineda I.X., Perez Moran D., Trejo Villeda M.A., Gomez Del Pulgar M., Rodriguez Zamora M.C., et al. Patient experience in automated peritoneal dialysis with telemedicine monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico: Qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2023 Feb;10(2):1092–1101. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malo M.F., Affdal A., Blum D., et al. Lived Experiences of Patients Receiving Hemodialysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study from the Quebec Renal Network. Kidney360. 2022 Apr 25;3(6):1057–1064. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000182022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guha C, Tong A, Baumgart A, et al. Suspension and resumption of kidney transplant programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives from patients, caregivers and potential living donors - a qualitative study. Transpl Int. 2020 Nov;33(11):1481-1490. https://doi.org/10.111/tri.13697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Antoun J, Brown D, Jones DJW, et al. Understanding the Impact of Initial COVID-19 Restrictions on Physical Activity, Wellbeing and Quality of Life in Shielding Adults with End-Stage Renal Disease in the United Kingdom Dialysing at Home versus In-Centre and Their Experiences with Telemedicine. Int J Environ Research Public Health. 2021 Mar 18;18(6):3144. https://doi.org/0.3390/ijerph18063144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Porteny T., Gonzales K.M., Aufort K.E., et al. Treatment Decision Making for Older Kidney Patients during COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022 Jul;17(7):957–965. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13241021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKeaveney C., Noble H., Courtney A.E., et al. Dialysis, Distress, and Difficult Conversations: Living with a Kidney Transplant. Healthcare (Basel) 2022 Jun 23;10(7):1177. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10071177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyck Lee S, Ramondino S, Gallo K, Moist LM. A Quantitative and Qualitative Study on Patient and Physician Perceptions of Nephrology Telephone Consultation During COVID-19. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022 Jan 5;9:20543581211066720. doi:10.1177/20543581211066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Huuskes BM, Scholes-Robertson N, Guha C, et al. Kidney transplant recipient perspectives on telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transpl Int. 2021 Aug;34(8):1517-1529. https://doi.org/10.111/tri.13934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Tsapepas D., Husain S., King K.L., Burgos Y., Cohen D.J., Mohan S. Perspectives on COVID-19 vaccination among kidney and pancreas transplant recipients living in New York City. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021 Nov 9;78(22):2040–2045. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxab272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C.S., Doma R., Westbrook A.L., et al. Vaccine Attitudes and COVID-19 Vaccine Intention Among Parents of Children With Kidney Disease or Primary Hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81(1):25–35.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon S, Hoe PS, Chan A, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on perceived wellbeing, self-management and views of novel modalities of care among medically vulnerable patients in Singapore. Chronic Illn. 2023 Jun 19(2):314-326. doi:17423953211067458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Valson A., George R., Lalwani M., et al. Impact of the lockdown on patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis at a tertiary care facility in Southern India - A mixed-methods approach. Indian J Nephrol. 2022 May-Jun;32(3):256–261. doi: 10.4103/ijn.IJN_561_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis M.J., Alqarni K.A., McGrath-Chong M.E., Bargman J.M., Chan C.T. Anxiety and psychosocial impact during coronavirus disease 2019 in home dialysis patients. Nephrology. 2022 Feb;27(2):190–194. doi: 10.1111/nep.13978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monaghesh E., Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020 Aug 1;20(1):1193. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwok C.S., Muntean E.A., Mallen C.D. The impact of COVID-19 on the patient, clinician, healthcare services and society: A patient pathway review. J Med Virol. 2022 Aug;94(8):3634–3641. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett D, De Vita E, Ventura V, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak on heart and lung transplant: A patient-perspective survey. Transpl Infect Dis. Feb;23(1):e13428. doi:10.1111/tid.13428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Edlund K., Dahlström L.A., Ekström A.M., van der Kop M.L. Patients' perspectives on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to cancer care and social contacts in Sweden and the UK: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2022 Nov;30(11):9101–9108. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rapelli G., Lopez G., Donato S., et al. A postcard from Italy: Challenges and psychosocial resources of partners living with and without a chronic disease during COVID-19 epidemic. Front Psychol. 2020 Dec 11;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umar S., Chybisov A., McComb K., et al. COVID-19 and access to cancer care in Kenya: patient perspective. Int J Cancer. 2022 May 1;150(9):1497–1503. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burn H. Gaining the patient perspective on COVID-19 and how best to respond to it. Br J Gen Pract. 2021 Jan 28;71(703):70. doi: 10.3399/bjgp21X714713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartley N., Havard P., Butow P., Shaw J. COVID-19 Cancer Stakeholder Authorship Group. Experiences and perspectives of cancer stakeholders regarding COVID-19 vaccination. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2023 Feb;19(1):234–242. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chudasama Y.V., Gillies C.L., Zaccardi F., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Sep-Oct;14(5):965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf M.S., Serper M., Opsasnick L., et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the US outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Int Med. 2020 Jul 21;173(2):100–109. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hart J.L., Turnbull A.E., Oppenheim I.M., Courtright K.R. Family-Centered Care During the COVID-19 Era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Aug;60(2):e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedrosa A.L., Bitencourt L., Fróes A.C.F., et al. Emotional, Behavioral, and Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020 Oct 2;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor A., Caffery L.J., Gesesew H.A., et al. How Australian health care services adapted to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of telehealth professionals. Front Public Health. 2021 Feb 26;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.648009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valente A., Jesus J., Breda J., et al. Dietary Advice in hemodialysis patients: impact of a Telehealth approach during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ren Nutrit. 2022 May;32(3):319–325. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arevalo Iraheta YA, Murillo AL, Wood EH, Advani SM, Pines R, Waterman AD. Challenges and stressors of covid-19 kidney and transplant patients: A mixed methods study. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(Suppl 4):470. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16847.

- 49.Bonenkamp A.A., Druiventak T.A., van Eck van der Sluijs A., et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of dialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2021 Apr;34(2):337–344. doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Figueiredo D., Sousa H., Amado L., Miranda V., Costa E., Paul C., et al. Pos-793 Undergoing Hemodialysis during Covid-19 Lockdown: Exploring Patients' and Family Caregivers' Experiences. Kidney Int Reports. 2021;6(4 Suppl):S344–S345. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortin M.C., Malo M.F.A., Affdal A.O., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on hemodialysis patients: The Quebec renal network (QRN) COVID-19 study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:771. doi: 10.1681/asn.2021020208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gordon E.J., Uriarte J.J., McLagan A.N., et al. Barriers to Completing the Transplant Evaluation Process: A Mixed- Methods Study. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(Suppl 3):1046. doi: 10.1111/ajt.17073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haokip N, Rathore P, Kumar S, et al. Psychosocial Burdens of a Renal Transplant Recipient with COVID-19. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020 June;26(Suppl 1):S168-s169. doi:10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_169_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.John M.O., Gummidi B., Jha V. Pos-330 Risk Perceptions About Covid-19 among a Cohort of Chronic Kidney Disease Patients in Rural India. Kidney Int Reports. 2021;6(Suppl 4):S143–S144. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanavaki A., Palmer J., Lightfoot C.J., Wilkinson T., Billany R.E., Smith A. Support for chronic kidney disease patients during COVID-19: Perspectives from patients, family and healthcare professionals. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36(Suppl 1):i362–i363. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab091.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lunney M, Thomas C, Rabi D, Bello AK, Tonelli M. Video Visits Using the Zoom for Healthcare Platform for People Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis and Nephrologists: A Feasibility Study in Alberta, Canada. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021 Apr 26;8:20543581211008698. doi: 10.1177/20543581211008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.McKeaveney C., Noble H., Courtney A.E., et al. Dialysis, Distress, and Difficult Conversations: Living with a Kidney Transplant. Healthcare (Basel) 2022 Jun 23;10(7):1177. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10071177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ng J.H., Halinski C., Nair D., Diefenbach M.A. Barriers and facilitators to emotional well-being and healthcare engagement in COVID-19: A qualitative study among patients with kidney disease and their caregivers [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:85. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Porteny T., Koch-Weser S., Rifkin D.E., et al. Decision-making during uncertain times: A qualitative study of kidney patients, care partners, and nephrologists during the COVID-19 pandemic [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:73. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rivera E., Clark-Cutaia M.N., Schrauben S.J., et al. Treatment adherence support and relationships with CKD providers: A qualitative analysis [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:735. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt I.M., Stern L.D., Farr M., Nguyen N.H., Waikar S.S., Shohet M. Stigma syndemics and ESKD in disenfranchised urban communities fighting COVID-19 [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Zanten R., Peelen D., Laging M., et al. Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on daily lives, emotions and behaviours of kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2021;34(Suppl 1):114–115. doi: 10.1111/tri.13944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varsi C.S., Aud-Eldrid, Børøsund Elin, Solberg Nes L. Video as an alternative to in-person consultations in outpatient renal transplant recipient follow-up: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2021 Mar;22(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02284-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.