Abstract

Objective

Poor adherence to recommended intake protocols is common and a top challenge for micronutrient powder (MNP) programmes globally. Identifying modifiable predictors of intake adherence could inform the design and implementation of MNP projects.

Design

We assessed high MNP intake adherence among children who had received MNP ≥2 months ago and consumed ≥1 sachet (n 771). High MNP intake adherence was defined as maternal report of child intake ≥45 sachets. We used logistic regression to assess demographic, intervention components and perception-of-use factors associated with high MNP intake.

Setting

Four districts of Nepal piloting an integrated infant and young child feeding and MNP project.

Subjects

Children aged 6–23 months were eligible to receive sixty MNP sachets every 6 months with suggested intake of one sachet daily for 60 d. Cross-sectional surveys representative of children aged 6–23 months were conducted.

Results

Receiving a reminder card was associated with increased odds for high intake (OR=2·18, 95 % CI 1·14, 4·18); exposure to other programme components was not associated with high intake. Mothers perceiving ≥1 positive effects in their child after MNP use was also associated with high intake (OR=6·55, 95 % CI 4·29, 10·01). Perceiving negative affects was not associated; however, the child not liking the food with MNP was associated with lower odds of high intake (OR=0·12, 95 % CI 0·08, 0·20).

Conclusions

Behaviour change intervention strategies tailored to address these modifiable predictors could potentially increase MNP intake adherence.

Keywords: Micronutrient powders, Nepal, Infant and young child feeding, Adherence, Compliance

Adherence refers to the extent to which intervention participants follow suggested guidance or carry out an intervention in accordance with recommendations. Poor adherence is common and limits the impact of efficacious nutrition interventions, but it is a modifiable behaviour with potential for improvement( 1 ). Adherence is influenced by individual factors and the enabling environment. For preventive nutrition interventions, these factors often include attributes of the intervention participant(s), their families and social networks; the local context; behaviours of health-care workers (professional and voluntary); and characteristics of the health system and the intervention package. Further, the risk of poor adherence escalates for interventions with longer duration and increasing complexity( 1 , 2 ).

Micronutrient powders (MNP) are sachets of vitamins and minerals that can be mixed into any ready-to-eat semi-solid food in order to reduce micronutrient deficiencies among children aged 6 months and older. The WHO recommends home fortification of foods with MNP for children aged 6–23 months; the suggested intake regimen is to consume at least sixty MNP sachets every 6 months( 3 ). MNP intake adherence involves following the suggested intake regimens and assumes adherence to appropriate use and preparation, which can also influence intake, impact and safety.

Implementation research to support sustained high MNP intake adherence is a priority and has been identified as a top challenge in MNP public health programmes globally( 4 ). In theory, MNP are expected to have few intake adherence barriers because they are used to fortify local foods already consumed and it is easy to mix the MNP into food right before consumption. Further, with appropriate use and preparation, there should be no change to the colour, taste, smell or texture of the food so that participants do not realize the MNP is in the food. MNP often have very high acceptability among intervention participants, but key challenges include motivating sustained use of a new preventive product for periodic intake over a long period of time (e.g. usually 18 months or longer) that does not address a visible or tangible health problem for many participants( 5 ).

The Nepal Ministry of Health and Population and UNICEF carried out an integrated infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and MNP pilot programme for children aged 6–23 months starting in 2010. We analysed data collected in different districts 3 months and 15 months after pilot programme implementation to assess predictors of high MNP intake adherence. Additionally, we explored frequently cited positive and negative effects observed during MNP use and report potential programmatic elements that may lead to higher MNP intake adherence among populations.

Materials and methods

Integrated infant and young child feeding/micronutrient powder pilot project

The pilot project added MNP to an existing comprehensive IYCF programme that provided education and counselling to support recommended breast-feeding and complementary feeding practices. The programme provided sixty MNP sachets for free every 6 months to all children 6–23 months of age in the pilot districts. In rural areas, where the majority of participants lived, two delivery models were used: MNP were distributed either by female community health volunteers (FCHV) in villages or by health workers at the local health facility. In urban areas, MNP were initially distributed by FCHV at a campaign-like event and then distributed through health facilities or other convenient government agencies depending on the local context.

All eligible children should have received sixty MNP sachets at the start of the pilot in each district and then obtained another sixty MNP sachets every 6 months thereafter. For children younger than 6 months at the start of the pilot, as they reached 6 months of age they should have obtained sixty MNP sachets routinely through FCHV or health facilities. Families were instructed to give their child one sachet daily until all had been consumed and then collect another sixty sachets 6 months after obtaining the first batch. If they missed a day or stopped for any reason, they were instructed to restart and finish all sachets within the 6-month period. For preparation and serving, they were told to mix the MNP into semi-solid food that was at a temperature ready to eat and to have the child consume the food within 30 min of mixing in the MNP. Further, that MNP should be mixed into a small portion of food that the child could consume all of at one sitting and then additional food could be given. Families were also specifically told not to mix the MNP into liquids, or into food that was cooking or too hot to eat. They were warned that after MNP intake the child’s stool might be loose for the first few days or darken, but this was to be expected. Mothers were given a brochure containing these messages about MNP preparation and use, and a reminder card indicating when they should obtain the next batch of MNP. Information about anaemia was provided as part of the IYCF education.

Prior to the pilot, a feasibility study and formative research were carried out to design the intervention and develop the behaviour change component. The MNP formulation containing fifteen vitamins and minerals was locally branded as Baal Vita. FCHV were the primary channels to deliver MNP behaviour change information and support in all delivery models. FCHV already supported the IYCF programme and were expected to hold mothers’ group meetings every month on various topics. For the pilot, the behaviour change intervention component consisted of counselling and support on recommended IYCF practices and MNP use, as well as MNP promotion through mass media (e.g. radio spots, billboards) and distribution of written and visual materials (e.g. brochures, reminder cards) along with the batches of MNP sachets. Health facility staff were trained and supported the behaviour change component, but were expected to have fewer opportunities for contact with families compared with the FCHV who lived in the villages. The behaviour change component was designed to be the same across all delivery models. Additional details about the pilot programme and monitoring surveys are published elsewhere( 6 ).

Survey design and sampling

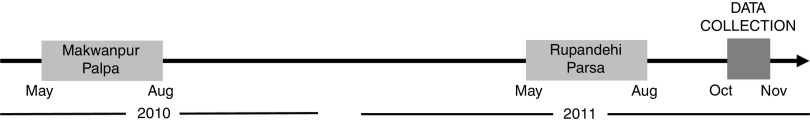

As part of programme monitoring, representative cross-sectional household surveys were collected in four of the pilot districts by an external survey organization: Rupandehi, Parsa, Makwanpur and Palpa districts. Due to the staggered roll-out of the programme, surveys were conducted either 3 months (Rupandehi, Parsa) or 15 months (Makwanpur, Palpa) after the programme began in each district and all survey data were collected in October and November 2011 (Fig. 1). Data were representative of all areas (urban and rural) of Rupandehi and Parsa districts but only representative of rural areas of Makwanpur and Palpa districts (more than 80 % of the population in these districts live in rural areas). Population-proportional-to-size sampling was used to randomly select thirty clusters from rural areas of each of the four districts and thirty clusters across the urban municipalities of Rupandehi and Parsa districts. A census was carried out in each cluster and twelve children aged 6–23 months were randomly selected and their mother or primary caregiver invited to participate (thus 360 children were selected from rural areas of each of the four districts and 360 children from across urban areas of Rupandehi and Parsa). As most respondents were mothers (98·8 %), they are referred to as ‘mothers’ in the present paper. There were no replacements in any cluster if there were fewer than twelve eligible children or for refusals to participate. Participation in the interview was voluntary and women gave verbal informed consent that was witnessed and recorded. We used de-identified data from the household surveys in the present analysis.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of programme implementation and data collection. Implementation of the IYCF/MNP pilot programme in Nepal was started in Makwanpur and Palpa districts in May–August 2010 and in Rupandehi and Parsa districts in May–August 2011. Data were collected in October–November 2011 (IYCF, infant and young child feeding; MNP, micronutrient powder)

Micronutrient powder intake adherence

The primary outcome was high MNP intake adherence among children who consumed MNP. Each mother was asked the time since she had last obtained MNP for her child and how many of the sachets her child had consumed from the last batch. Only those who had obtained the MNP ≥2 months prior to the interview were included. A child was defined as having high intake adherence if the mother reported obtaining MNP ≥2 months before the date of interview and that the child consumed forty-five or more sachets. A cut-off of 75 % adherence was selected to allow for some missed sachets in children who had the MNP for 2 months, while still having consumed the MNP on most days. Children whose mothers reported obtaining MNP within the previous 2 months were excluded as they had not had the opportunity to consume at least forty-five sachets. Mothers were instructed to give the MNP daily and if they stopped for any reason, to start again until all sachets were consumed; however, the present analysis did not examine whether the sachets were consumed daily or over a longer time period (purposely or not) using a different intake regimen.

Programme exposure and experience with micronutrient powder variables

Mothers were asked questions about their child, education and household assets (used to generate a wealth quintile) and about their exposures to and experiences with the intervention. Specific programme experiences (yes v. no) were used as proxies of exposure to the intervention, including if they had ever received information about MNP at an FCHV-led mothers’ group meeting, had ever heard the MNP radio spot advertisement, or received an intervention brochure or reminder card. Mothers were asked about experiences with MNP including any perceived positive or negative effects (dichotomized as: perceived ≥1 positive/negative effects v. none) and whether their child likes consuming food mixed with MNP (yes v. no). Mothers were asked knowledge questions related to IYCF practices and MNP use, including if they knew any consequences of anemia (dichotomized as: knows ≥1 consequences v. no) and knew proper preparation of MNP (dichotomized as: answers all preparation questions correctly v. answers ≥1 question incorrectly).

Perceived effects of MNP in the child and barriers and motivators for MNP use were assessed. All mothers were asked: (i) if they perceived any positive effects in their child after consuming MNP; and (ii) if they perceived any negative effects in their child after consuming MNP. Mothers who reported that less than sixty MNP sachets were given were asked: (i) reasons for not giving sixty MNP sachets; and (ii) what would support or motivate them to continue giving MNP. These were open-ended questions and spontaneous responses were recorded.

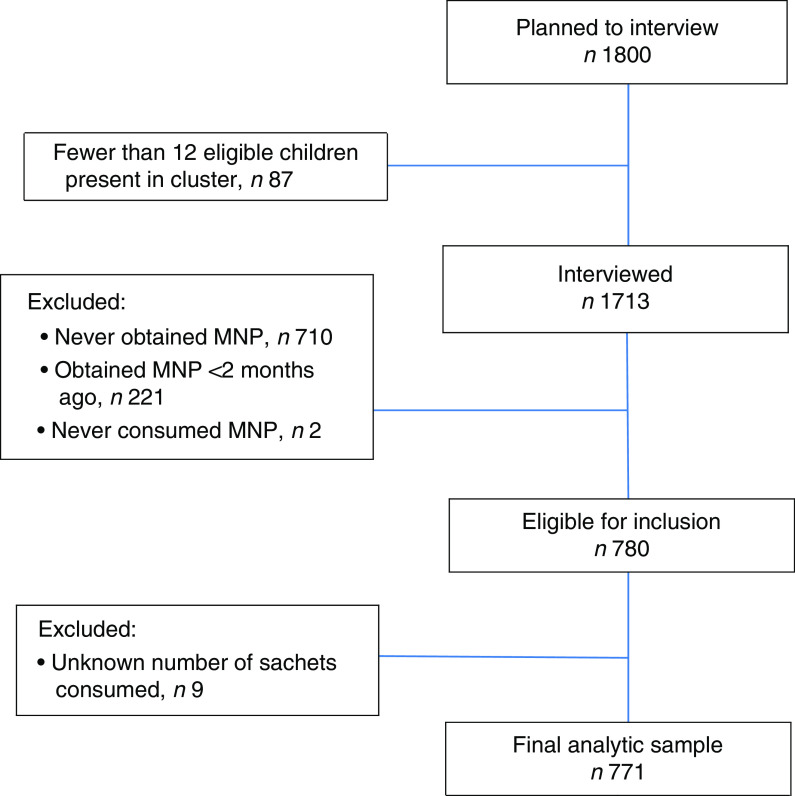

Analytic sample

Our analytic sample was limited to mothers of children aged 7–23 months who reported the child consumed at least one MNP sachet from the most recent batch and that the last batch of sixty MNP sachets was obtained ≥2 months ago. A total of 1800 children were intended for inclusion in the study. In clusters with less than twelve children aged 6–23 months, no replacement was made; eighty-seven children fell into this category resulting in 1713 interview attempts. Of the 1713 mothers who were interviewed, 710 were excluded for having never obtained MNP, 221 were excluded for having obtained the MNP <2 months ago and two children were excluded who obtained MNP but never consumed any, resulting in a sample of 780. Of these, nine were excluded for not knowing the number of sachets consumed. The final analytic sample included 771 children aged 7–23 months who had obtained the MNP ≥2 months ago and consumed at least one sachet. Characteristics of children included in the final analytic sample were not different from those of the 780 eligible children. A schematic overview of those included in our final analytic sample is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram for inclusion in the analytic study population (MNP, micronutrient powder)

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the statistical software package SAS version 9·3 accounting for complex survey design and weighted. Statistical significance was set at α=0·05. A logistic regression model was constructed to assess predictors of high intake adherence. The following predictor variables were included in the model: child age, child sex, attending a mothers’ group meeting, received counselling from health facility staff, heard MNP radio spot, received MNP brochure, received MNP reminder card, knows consequences of anaemia, knows correct MNP preparation, perceived any negative effects, perceived any positive effects and reports child does not like food mixed with MNP. The model was adjusted for maternal education, wealth quintile, district and survey time since programme implementation (3 months v. 15 months). We calculated the frequencies of the most common positive and negative effects of MNP use reported by mothers. Multiple responses were possible, so frequencies do not sum to 100%; responses reported by <5% of mothers are not presented (e.g. started to walk (positive) and constipation (negative)). Among mothers of children who did not meet the criteria of high intake adherence, we additionally describe the frequencies of the most common reasons reported for not giving sixty MNP sachets. Again, multiple responses were possible, so frequencies do not sum to 100 %, and responses reported by <5% of mothers are not presented.

Results

Characteristics of the sample population

Demographic characteristics, experiences with the programme and with MNP are summarized in Table 1. Among mothers of children, 30·1% had no education and 35·2 % of families were in the lowest two wealth quintiles. Overall, 71·3 % of mothers reported the proper methods to prepare and serve MNP to the child and 55·7 % of participants met criteria for high intake adherence.

Table 1.

Population characteristics and programme experiences of the sample population of children aged 7–23 months who consumed MNP (n 771), selected districts of Nepal, 2011

| %* | |

|---|---|

| Child’s age | |

| 7–11 months | 14·7 |

| 12–17 months | 50·0 |

| 18–23 months | 35·3 |

| Male | 52·5 |

| Education of mother | |

| No education | 30·1 |

| Primary level (1–5 class)/adult/informal | 29·8 |

| Secondary level (6–10 class) and above | 40·1 |

| Wealth quintile | |

| Lowest/second lowest | 35·2 |

| Middle | 23·7 |

| Highest/second highest | 41·1 |

| Met criteria for high intake adherence | 55·7 |

| Attended a mothers’ group meeting† | 20·8 |

| Received counselling from health facility staff | 49·3 |

| Heard MNP radio spot | 23·1 |

| Knows ≥1 consequences of anemia | 42·5 |

| Received brochure | 54·8 |

| Received reminder card | 84·6 |

| Knows proper MNP preparation | 71·3 |

| Perceived ≥1 negative effects | 44·6 |

| Perceived ≥1 positive effects | 60·6 |

| Child does not like MNP | 36·9 |

MNP, micronutrient powder; IYCF, infant and young child feeding.

Row percentages represent weighted frequencies.

Attended a mothers’ group meeting led by a female community health volunteer where the IYCF/MNP intervention was discussed.

Predictors of high intake adherence

Of the intervention exposures examined, children of mothers who received a reminder card had 2·18 times the odds of meeting criteria for high intake adherence (95% CI 1·14, 4·18) compared with children whose mothers who did not receive a reminder card. In addition, children of mothers who attended a mothers’ group meeting where MNP was discussed had 1·55 times the odds of meeting criteria for high intake adherence with a 95 % CI that bordered significance of 0·98, 2·43. Children of mothers who perceived one or more positive effects in their children after MNP use had 6·55 times the odds of meeting criteria for high intake adherence (95 % CI 4·29, 10·01) compared with those of mothers who perceived none. In addition, children reported to not like the MNP had lower odds of high intake adherence (adjusted OR=0·12, 95% CI 0·08, 0·20) compared with children of mothers who did not report their child disliked MNP (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of high intake adherence among MNP consumers, children aged 7–23 months, selected districts of Nepal, 2011

| n | % with high intake adherence* | Adjusted OR* | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child demographics | ||||

| Child’s age | ||||

| 7–11 months | 120 | 60·2 | 1·00 | – |

| 12–17 months | 380 | 55·5 | 1·18 | 0·66, 2·10 |

| 18–23 months | 271 | 54·2 | 1·37 | 0·73, 2·55 |

| Child’s sex | ||||

| Male | 402 | 56·4 | 1·00 | – |

| Female | 369 | 55·0 | 1·03 | 0·70, 1·57 |

| Intervention exposure | ||||

| Attended a mothers’ group meeting | ||||

| No | 608 | 51·6 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 163 | 71·3 | 1·55 | 0·98, 2·43 |

| Received counselling from health staff | ||||

| No | 373 | 55·6 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 398 | 55·8 | 0·96 | 0·57, 1·63 |

| Heard MNP radio spot | ||||

| No | 574 | 54·3 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 197 | 60·4 | 1·50 | 0·83, 2·70 |

| Knows ≥1 consequences of anemia | ||||

| No | 427 | 53·0 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 344 | 59·4 | 0·90 | 0·53, 1·51 |

| Received brochure | ||||

| No | 361 | 51·0 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 410 | 59·6 | 1·50 | 0·93, 2·42 |

| Received reminder card | ||||

| No | 123 | 37·7 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 648 | 59·0 | 2·18 | 1·14, 4·18 |

| Knows proper preparation | ||||

| No | 226 | 46·8 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 545 | 59·3 | 1·38 | 0·90, 2·12 |

| Demand/motivation | ||||

| Perceived ≥1 negative effects | ||||

| No | 428 | 64·2 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 343 | 45·1 | 0·64 | 0·39, 1·04 |

| Perceived ≥1 positive effects | ||||

| No | 310 | 19·8 | 1·00 | – |

| Yes | 461 | 79·1 | 6·55 | 4·29, 10·01 |

| Child doesn’t like MNP | ||||

| Not reported | 475 | 78·3 | 1·00 | – |

| Reported | 296 | 17·1 | 0·12 | 0·08, 0·20 |

MNP, micronutrient powder.

Models include all predictor variables and are adjusted for maternal education, wealth quintile, district and survey time since programme implementation; significant results are presented in bold font.

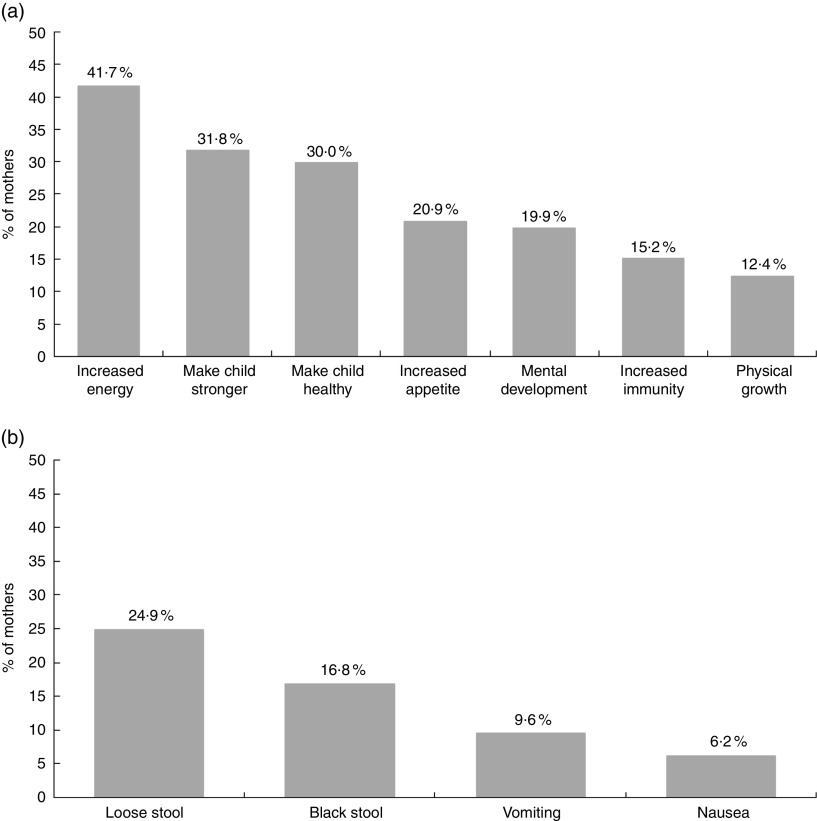

Perceived positive and negative effects in children after use of micronutrient powder

Overall 41·7 % of mothers reported that MNP use resulted in increased energy in the child (Fig. 3(a)). Other frequently reported positive effects were: making the child stronger (31·8%), making the child healthier (30·0%), increased appetite (20·9 %), mental development (19·9%), increased immunity (15·2 %) and physical growth (12·4%).

Fig. 3.

Positive and negative effects associated with MNP use among children aged 7–23 months, selected districts of Nepal, 2011. Percentage of mothers who provided the responses listed on the x-axis when asked about (a) positive effects and (b) negative effects observed in her child after MNP use. Response options were not read to participants and multiple answers were possible, so the total may sum to more than 100 %. Options with <5 % of responses were excluded. Frequencies are weighted and adjusted for complex survey design; n 771 (MNP, micronutrient powder)

Loose stool was the most frequently reported negative effect of MNP intake reported by 24·9% of mothers (Fig. 3(b)). The other most frequently reported negative effects were: black stool (16·8 %), vomiting (9·6%) and nausea (6·2%).

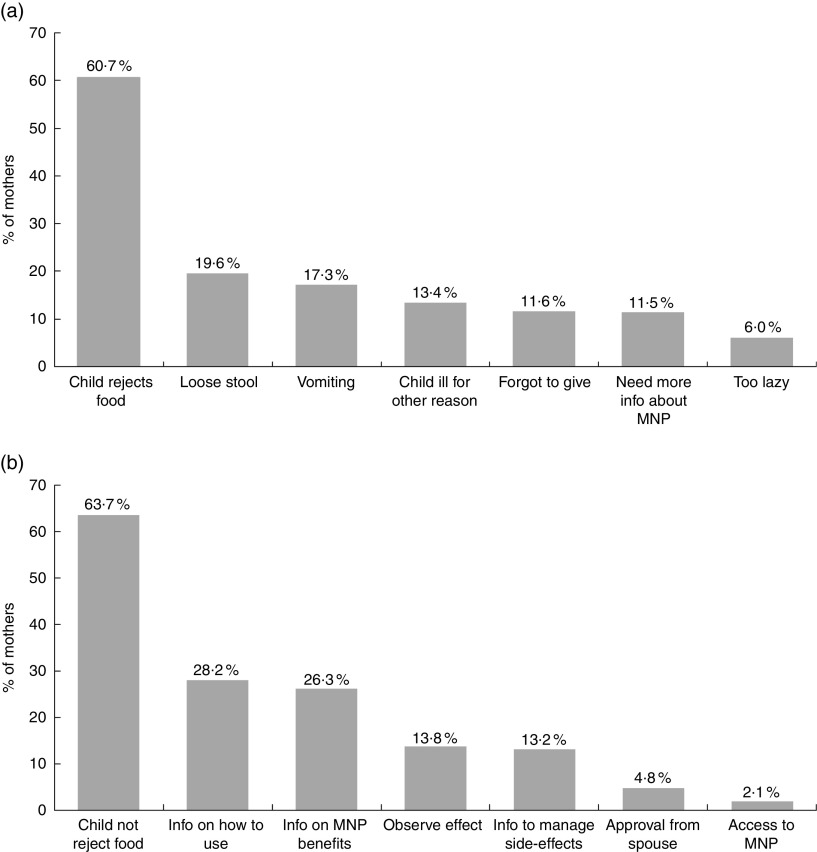

Reasons for low intake adherence

Among mothers of children who did not meet the criteria for high intake adherence (n 348), the most frequent reason for not giving sixty MNP sachets was the child rejecting food mixed with MNP (60·7%; Fig. 4(a)). Other common responses included: causes loose stool (19·6 %), causes vomiting (17·3 %), child had an illness (unrelated to MNP use) that caused mother to stop MNP (13·4%), mother forgot to give MNP (11·6%), mother needed more information about MNP (11·5 %) and the mother reporting she was too lazy (6·0%). Among mothers of children who did not meet the high intake adherence criteria, few reported pressure to share the MNP with someone other than the target child (4·2%).

Fig. 4.

Reasons for low intake adherence and potential ways to support or motivate adherence among children aged 7–23 months, selected districts of Nepal, 2011. Percentage of mothers of children who did not meet criteria for high intake adherence who provided the responses listed on the x-axis when asked about (a) reasons for not giving sixty MNP sachets and (b) what would help support or motivate to continue using MNP. Response options were not read to participants and multiple answers were possible, so the total may sum to more than 100%. Frequencies are weighted and adjusted for complex survey design; n 348 (MNP, micronutrient powder)

Among mothers of children who did not meet the criteria for high intake adherence, 63·7% reported that having the child not reject food with MNP would support and motivate her to continue giving MNP (Fig. 4(b)). Other frequently reported responses were: information about how to use MNP (28·2 %), information about the benefits of MNP (26·3 %), observing positive effects in other children (13·8 %) and information on how to resolve side-effects of MNP use (13·2 %). Few mothers reported that approval from her husband or in-laws (4·8 %) or increased access to MNP (2·1 %) would support or motivate her to continue giving MNP to the child.

Discussion

Using programmatic data from an integrated IYCF/MNP pilot project in Nepal, we identified several predictors of high MNP intake adherence for children 7–23 months of age, including mothers perceiving positive effects in the child after MNP use, child not disliking food mixed with MNP and receipt of the MNP reminder card. Taking into consideration modifiable predictors during the design and implementation of interventions could potentially increase the proportion of participants achieving and sustaining high MNP intake adherence.

Mothers who perceived at least one positive effect in their children after MNP use had more than six times the odds of meeting the criteria for high intake adherence, compared with mothers who perceived no positive effects. Consistent with reports from other settings( 7 – 10 ) mothers reported various positive effects of MNP including increased energy, strength, health, appetite, immunity and growth. While multiple factors may influence mothers and families perceiving a positive effect, appropriately positioning the potential positive effects of MNP intake adherence in the behaviour change component and supporting mothers and families to achieve and sustain the child’s MNP intake long enough to perceive positive effects may be critical components in the design and implementation of these interventions for motivating high use. We noted that a substantial proportion (44·6 %) of mothers reported one or more negative effects after MNP intake, also consistent with reports from other settings( 7 – 10 ), but perceiving negative effects did not result in lower odds for high MNP intake adherence, suggesting these potential barriers were manageable. In the pilot, mothers were warned that children might experience loose or dark stools, the two most commonly mentioned negative effects, and this information might have mitigated the potential detrimental influence on intake adherence and acceptability, as has been reported in other settings( 9 , 10 ).

Mothers who reported their children did not like food mixed with MNP had significantly lower odds of adherence to high intake compared with mothers who did not report it. Further, among those who did not have high intake adherence, maternal reports of the child disliking food mixed with MNP was by far (over 30 percentage points) the most common reason for not giving all of the MNP sachets to the child. In theory, when prepared correctly the food mixed with MNP should have no change in texture, smell, colour or taste. A potential sign of incorrect preparation of food with MNP is the consumer (child) noticing the MNP in food. The MNP intervention materials and behaviour change instructions and strategies emphasized the appropriate use and correct preparation of food mixed with MNP. Further, over 71 % of mothers reported knowledge of all of the components of the correct preparation and serving of food mixed with MNP, and in the surveys mothers did not report sensory changes to food mixed with MNP as a barrier to use. Internal monitoring data identified that some mothers were mixing the MNP sachet into a single spoonful of food and feeding it to the child, especially for the youngest children, when operationalizing the instruction to mix the MNP into a quantity of food that a child could eat all of at one sitting. It is possible the MNP was noticed in these cases, but it is unclear how widespread this practice occurred. Additional investigation of causes and possible solutions for child refusals during process monitoring of the programme suggested that reinforcing skills in active feeding, correct food preparation with MNP, varying the foods fed to children mixed with MNP, and reminding mothers to not assume the child will not like food mixed with MNP, might be strategies to help reduce the perception of child refusals( 11 ). It is possible that some mothers retained the information of how to correctly prepare the food but still lacked the skills or motivation to overcome the barrier of child refusals and were unable to successfully operationalize this information into practice. This barrier highlights the intersection of knowledge (information), skills and motivation needed to support MNP intake adherence and shows that only one of these components is not sufficient, all three are required( 12 ).

In addition to the child refusing food mixed with MNP, approximately 10–20 % of mothers whose children did not meet the criteria for high intake adherence reported additional reasons for the lower MNP intake. Most of these reasons could be addressed through the behaviour change strategies by supporting mothers and families to manage side-effects and providing information to raise awareness, understanding and motivation to participate; using personal prompts and reminders to re-start MNP intake if it is stopped for any reason; and maintaining the salience of the intervention among participants. The programme package included distribution of an MNP reminder card, which was a two-sided card that included the local branding and images, described the benefits of the MNP, showed where to get MNP, had sixty boxes to mark off daily MNP use and information of when to return for the next batch of sixty MNP. Those who reported receiving the reminder card had more than two times increased odds of high MNP intake adherence. These cards serve as reminders, visual cues and motivators to use MNP, and may help to establish regular intake routines, even if the boxes are not marked after use. Motivation and demand among participants are not static, especially for long-term interventions of several months or years that are at high risk of intervention fatigue; thus, ‘refreshing’ the promotion materials and messages and giving ongoing reminders of the benefits and to continue practising the intervention are needed( 13 , 14 ).

The literature demonstrates that factors at multiple levels influence adherence( 1 ), but the cross-sectional design and content of the surveys limited our ability to explore many of these potentially critical issues. For example, factors that may influence the enabling environment, such as the quality and nature of health-care workers’ or volunteers’ behaviours and skills, and their relationship with mothers, are powerful influences( 15 ). Identifying scalable behaviour change strategies that can be done with low burden and high quality by health-care workers and volunteers is a critical gap and an implementation research priority( 16 ). The design and complexity of the intake regimen and delivery system also play an important role in supporting adherence. Suggesting to mothers and families to establish a routine for the child’s MNP intake is a key strategy to support adherence regardless of the recommended intake schedule (e.g. daily, every other day, or flexibly defined by the participant as long as all sachets are consumed over a given period of time)( 1 ). The Nepal pilot distributed sixty sachets every 6 months and recommended daily intake of sixty sachets with a 4-month break between distributions. The scheduled 4-month break might have limited high intake adherence because it structured a hiatus in any established intake routine, which then needed to be re-established every 6 months. Identifying the number of expected contact points (either formal or opportunistic) when mothers will pick up batches of MNP or otherwise have the opportunity to interact with health-care workers or volunteers is useful so that a realistic estimate can be considered during the design phase; these contacts provide the opportunities for interpersonal communication so that mothers can ask questions, receive troubleshooting advice, or be prompted to continue giving children MNP or to re-start if they have stopped. In the Nepal pilot, while it was expected that ongoing contacts with FCHV and health-care workers would occur over the 6-month period, some participants likely only interacted with them when they were picking up the next batch of sixty sachets every 6 months and it is possible that a different MNP intake regimen and distribution schedule could have led to different levels of MNP intake adherence. Balancing frequent contact to enhance MNP intake adherence with the burden on the health system and on the participant can be a challenge, especially when there is limited capacity at individual, organizational and systems levels in the country( 17 ). Globally, MNP programmes show wide heterogeneity in the suggested MNP intake regimens and periodicity of MNP sachet distributions( 4 ). Understanding which intake regimens and distribution schedules most support high MNP intake adherence is an implementation research priority.

There are several strengths of the current analysis. These population-based surveys representative of children aged 6–23 months were collected during a programmatic pilot intervention in urban and rural settings of four districts. The analysis included demographics, indicators of components of the intervention and perceptions of MNP use, in order to consider multiple types of factor that might influence high intake adherence.

Limitations to the analysis include that the content did not include indicators reflective of all aspects of the enabling environment. The data are cross-sectional and MNP sachet intake data were reported by mothers and might suffer from socially desirable reporting, recall or other biases.

Identifying strategies to support MNP intake adherence is an implementation research priority( 4 , 5 ). The present analysis identified modifiable predictors of high MNP intake adherence and presented other programmatic data to understand the context of MNP intake in Nepal in young children 7–23 months of age. This information may be useful to inform the design and implementation of MNP interventions in other settings with the aim of ultimately improving MNP intake adherence and programme impact.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: The Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population and UNICEF Nepal Country Office supported the implementation of the pilot intervention. UNICEF Nepal funded an external agency to conduct the monitoring surveys described in this analysis. Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF or the Government of Nepal. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Authorship: M.E.D.J., concept and design, analysis, interpretation, writing and approval of manuscript. K.R.M., design, statistical analysis, interpretation, writing and approval of manuscript. C.G.P., concept and design, analysis, interpretation, writing and approval of manuscript. G.R.S., interpretation, revision and approval of manuscript. P.D., interpretation, revision and approval of manuscript. S.M., interpretation, revision and approval of manuscript. C.S., analysis, interpretation, revision and approval of manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Nepal Ministry of Health and Population. Verbal consent was obtained from all subjects/patients. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2003) Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N et al. (2008) Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev issue 2, CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (2011) Guideline: Use of Multiple Micronutrient Powders for Home Fortification of Foods Consumed by Infants and Children 6–23 Months of Age. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jefferds ME, Irizarry L, Timmer A et al. (2013) UNICEF–CDC global assessment of home fortification interventions 2011: current status, new directions, and implications for policy and programmatic guidance. Food Nutr Bull 34, 434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Pee S, Irizarry L, Kraemer K et al. (2013) Micronutrient powder interventions: the basis for current programming guidance and needs for additional knowledge and experience. Sight and Life September 2013, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jefferds ME, Mirkovic KR, Subedi S et al. (2015) Predictors of micronutrient powder sachet coverage in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr (Epublication ahead of print version). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Bilukha O, Howard C, Wilkinson C et al. (2011) Effects of multimicronutrient home fortification on anemia and growth in Bhutanese refugee children. Food Nutr Bull 32, 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kodish S, Rah JH, Kraemer K et al. (2011) Understanding low usage of micronutrient powder in the Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya: findings from a qualitative study. Food Nutr Bull 32, 292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Osei A, Septiari A, Suryantan J et al. (2014) Using formative research to inform the design of a home fortification with micronutrient powders (MNP) Program in Aileu District, Timor-Leste. Food Nutr Bull 35, 68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jefferds ME, Ogange L, Owuor M et al. (2010) Formative research exploring acceptability, utilization, and promotion in order to develop a micronutrient powder (Sprinkles) intervention among Luo families in western Kenya. Food Nutr Bull 31, 2 Suppl., S179–S185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Subedi GR, Upreti SR, Mebrahtu S et al. (2014) Monitoring and action to address child refusals of micronutrient powders in Nepal. Presented at Micronutrient Forum Global Conference, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2–6 June 2014.

- 12. De-Regil LM, Pena-Rosas JP, Flores-Ayala R et al. (2014) Development and use of the generic WHO/CDC logic model for vitamin and mineral interventions in public health programmes. Public Health Nutr 17, 634–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suchdev PS, Shah A, Jefferds ME et al. (2013) Sustainability of market-based community distribution of Sprinkles in western Kenya. Matern Child Nutr 9, Suppl., 1, 78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parvanta C (2014) Health communication: best practices for micronutrient interventions. Presented at Micronutrient Forum Global Conference, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2–6 June 2014.

- 15. Nanjappa S, Chambers S, Marcenes W et al. (2014) A theory led narrative review of one-to-one health interventions: the influence of attachment style and client-provider relationship on client adherence. Health Educ Res 29, 740–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Monterrosa EC, Frongillo EA, Gonzalez de Cossio T et al. (2013) Scripted messages delivered by nurses and radio changed beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors regarding infant and young child feeding in Mexico. J Nutr 143, 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Potter C & Brough R (2004) Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 19, 336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]