Abstract

Objective

To quantify the association between breast-feeding and Helicobacter pylori infection, among children and adolescents.

Design

We searched MEDLINETM and ScopusTM up to January 2013. Summary relative risk estimates (RR) and 95 % confidence intervals were computed through the DerSimonian and Laird method. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I 2 statistic.

Setting

Twenty-seven countries/regions; four low-income, thirteen middle-income and ten high-income countries/regions.

Subjects

Studies involving samples of children and adolescents, aged 0 to 19 years.

Results

We identified thirty-eight eligible studies, which is nearly twice the number included in a previous meta-analysis on this topic. Fifteen studies compared ever v. never breast-fed subjects; the summary RR was 0·87 (95 % CI 0·57, 1·32; I 2=34·4 %) in middle-income and 0·85 (95 % CI 0·54, 1·34; I 2=79·1 %) in high-income settings. The effect of breast-feeding for ≥4–6 months was assessed in ten studies from middle-income (summary RR=0·66; 95 % CI 0·44, 0·98; I 2=65·7 %) and two from high-income countries (summary RR=1·56; 95 % CI 0·57, 4·26; I 2=68·3 %). Two studies assessed the effect of exclusive breast-feeding until 6 months (OR=0·91; 95 % CI 0·61, 1·34 and OR=1·71; 95 % CI 0·66, 4·47, respectively).

Conclusions

Our results suggest a protective effect of breast-feeding in economically less developed settings. However, further research is needed, with a finer assessment of the exposure to breast-feeding and careful control for confounding, before definite conclusions can be reached.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Breast-feeding, Child, Adolescent

Helicobacter pylori infection has been classified a definite human carcinogen for almost two decades and is well accepted as the single most important risk factor for non-cardia gastric cancer( 1 , 2 ). Although the prevalence of infection has been decreasing in many of the more economically developed countries( 3 , 4 ), it was estimated to be responsible for nearly one-third of the 2 million cases of cancer occurring worldwide due to infections in 2008( 5 ).

H. pylori infection is acquired mainly during childhood and adolescence( 6 – 8 ); once obtained, and in the absence of a specific treatment, it can persist for decades( 9 ). Therefore, understanding the role of modifiable exposures that may be targeted to decrease the rate of H. pylori infection during childhood is of key importance to prevent its occurrence. Factors that promote interpersonal contact or are associated with poor hygienic conditions, including being born in a setting with a high prevalence of infection( 10 ), having parents with a low education level( 11 ), sharing a room with other subjects( 12 ) or attending a child-care institution( 13 ), have been consistently associated with H. pylori infection in the early years of life. Breast-feeding has long been recognized as protective against gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases( 14 , 15 ), and a role in the infection with H. pylori may be postulated.

A previous systematic review including sixteen studies suggested a protective effect of breast-feeding in middle- and low-income countries( 16 ). However, the understanding of the relationship between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection may be improved by taking into account more detailed and accurate definitions of the exposure. Furthermore, a set of additional studies were published since the previous meta-analysis, allowing an update of the existing evidence on this topic.

Therefore, we conducted a new systematic review and meta-analysis to quantify the association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection, among children and adolescents.

Methods

Search strategy

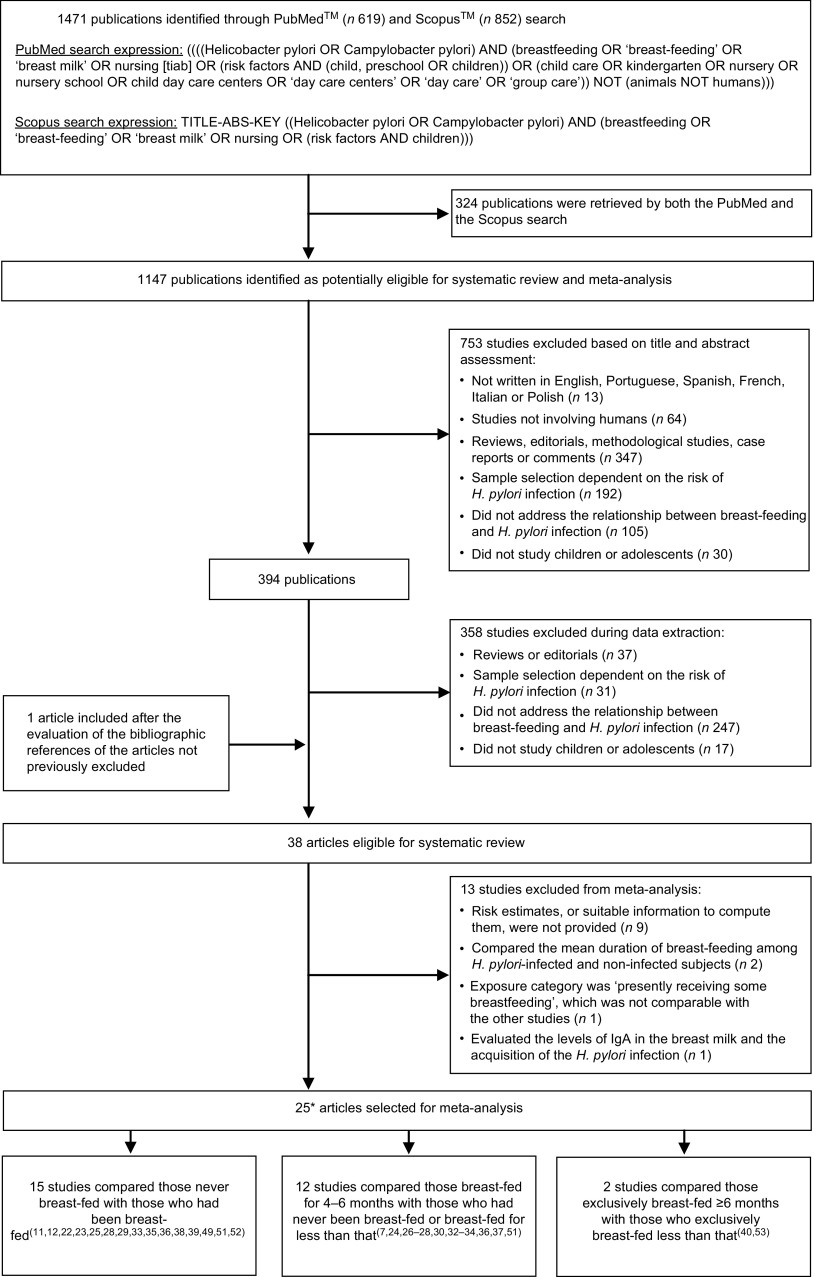

We searched MEDLINETM and ScopusTM up to January 2013 to identify studies addressing the association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection in childhood or adolescence. The PubMedTM and ScopusTM search expressions, and the systematic review flowchart, are presented in Fig. 1 according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement( 17 ). The literature search was further complemented by backward citation tracking among the articles considered eligible for the systematic review.

Fig. 1.

Systematic review flowchart according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement( 17 ). *Four studies( 27 , 32 , 35 , 50 ) provided data to quantify the association between both having been breast-fed and having been breast-fed for 4–6 months and Helicobacter pylori infection

Selection of the studies

The studies were assessed independently by two researchers (H.C. and B.P. or H.C. and A.B.) in three consecutive steps to determine their eligibility; disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus or involving a third researcher (N.L.).

In step 1, the studies were evaluated considering only the information presented in the title and abstract. When the abstract was not available, the study was further assessed, except when the title provided enough information to unequivocally exclude it. The full texts of the articles selected for step 2 were read to evaluate their eligibility and adequacy for data extraction; in step 3 the studies were re-evaluated to determine their eligibility for meta-analysis.

We excluded studies according to the following a priori defined criteria: (i) studies with full text not written in English, French, Italian, Polish, Portuguese or Spanish; (ii) reports not involving humans (e.g. in vitro studies); (iii) review articles, editorials, methodological studies, case reports or comments; (iv) studies in which the sample selection was dependent on the risk of H. pylori infection and therefore not expected to represent the general population (e.g. children undergoing endoscopy for diagnostic procedures); (v) studies not providing data on the association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection; (vi) studies assessing the H. pylori infection status only in adults; and (vii) duplicate reports of the same study (data could be extracted from one or more of the multiple reports to obtain the most complete information).

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the original reports: (i) year of publication; (ii) country and region where the study was conducted; (iii) study design; (iv) sample characteristics (sample size and age distribution); (v) methods used to determine the H. pylori infection status; (vi) exposure to breast-feeding, namely regarding its duration and exclusiveness; and (vii) relative risk (RR) estimates, namely risk ratios, incidence rate ratios or odds ratios, preferably adjusted for the larger number of potential confounders, or the necessary information to compute them, along with the corresponding precision estimates. Specific estimates for exclusive and non-exclusive breast-feeding or different durations of exposure were extracted whenever available.

For the studies providing data for age groups including adults in addition to children and/or adolescents (e.g. 10–29 years), we computed the mid-point year and excluded the data when it was higher than 18 years.

The discrepancies in the data extracted independently by two reviewers (H.C. and B.P. or H.C. and A.B.) were discussed and resolved by consensus, or involving a third researcher (N.L.).

Meta-analysis

The DerSimonian and Laird method was used to compute summary estimates of the association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection, and respective 95 % confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I 2 statistic( 18 ).

Stratified analyses according to the characteristics of the populations and methodological specificities with potential impact on the internal or external validity of the results (economic development of the countries where the investigations were conducted( 19 ), age of the participants, adjustment for the potential confounding effect of socio-economic status, method used to assess the H. pylori infection status, prevalence of H. pylori infection in the non-exposed participants, prevalence of breast-feeding) were conducted to identify factors associated with heterogeneous results.

Funnel plots and the Egger’s regression asymmetry test were used for assessment of ‘small studies effects’( 20 ). The statistical analysis was performed using the STATA® statistical software package version 9·2.

No review protocol was registered.

Results

We identified thirty-eight studies eligible for the systematic review( 7 , 10 – 12 , 21 , 30 , 32 – 55 ) (Fig. 1 and Appendices 1 and 2). The studies involved samples of children and adolescents, aged 0 to 19 years, recruited in twenty-seven countries/regions, including four low-income( 21 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 47 ), thirteen middle-income( 22 , 24 – 28 , 30 , 32 – 34 , 37 – 39 , 42 , 44 , 49 – 53 , 55 ) and ten high-income countries/regions( 7 , 10 – 12 , 23 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 43 , 45 , 48 , 49 , 54 ). Most studies had a cross-sectional design and eight were cohort studies( 37 , 39 , 40 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 49 , 53 ).

Thirteen studies did not provide information to compute an RR estimate for the association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection( 10 , 21 , 41 – 48 , 50 , 54 , 55 ) (Appendix 1). From these, eight referred a lack of association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection, although the point estimates were not provided( 10 , 41 , 43 – 45 , 47 , 50 , 54 ). One study reported that the ‘percentage of breastfeeding in the population in Korat was 61·25 %; the selected group of seropositive children had 51 % of exclusive breastfeeding for more than 6 months and 21·5 % the seropositive children had a history of breastfeeding for less than 6 months’( 55 ). One study involved a sample of children aged from 1 to 99 months and defined exposure as ‘presently receiving some breastmilk’( 46 ), which is not comparable with the definitions of breast-feeding used in the remaining reports. Two studies compared the mean duration of breast-feeding among H. pylori-infected and non-infected subjects( 42 , 48 ), and therefore could not be considered for meta-analysis; only one study showed a shorter duration of breast-feeding among the participants who were infected. Thomas et al. ( 21 ) compared the levels of IgA in the breast milk of the mothers and the infection with H. pylori in the respective children; the five children from the mothers who produced the lowest levels of IgA were infected.

Twenty-five studies( 7 , 11 , 12 , 22 – 30 , 32 – 40 , 49 , 51 – 53 ), from high-, middle- and low-income countries, provided data to quantify the association between breast-feeding and H. pylori. Among those, fifteen compared breast-fed v. non-breast-fed subjects( 11 , 12 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 49 , 51 , 52 ) and twelve compared subjects breast-fed for 4–6 months v. never breast-fed or breast-fed for less than 4–6 months( 7 , 24 , 26 – 28 , 30 , 32 – 34 , 36 , 37 , 51 ). Two studies specifically addressed the exclusive breast-feeding until the age of 6 months( 40 , 53 ) (Appendix 2).

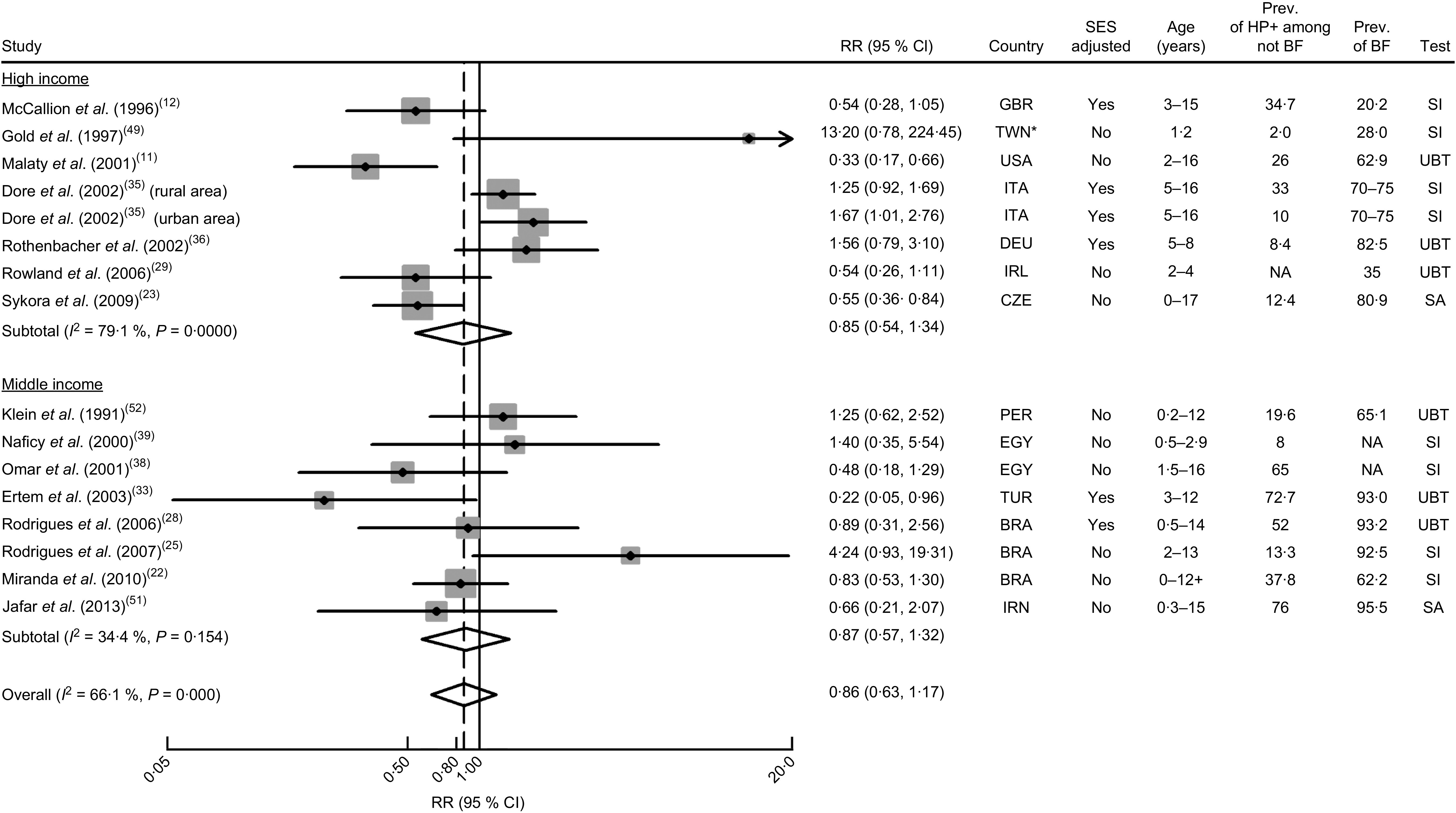

H. pylori infection according to history of breast-feeding (ever v . never)

Having been breast-fed was not significantly associated with H. pylori infection in either high-income (summary RR=0·85; 95 % CI 0·54, 1·34; I 2=79·1 %) or middle-income countries (summary RR=0·87; 95 % CI 0·57, 1·32; I 2=34·4 %). The results were heterogeneous, possibly reflecting a large inter-study variation in the duration of breast-feeding, since the prevalence of breast-feeding and the age range of the participants varied widely across studies (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analyses of studies evaluating the association between ever being breast-fed and Helicobacter pylori infection. Relative risk (RR) estimates and 95 % confidence intervals of H. pylori infection according to economic development of the countries where the investigations were conducted( 19 ). For each study, the black diamond indicates the best estimate, the size of the grey square indicates the study’s weight in the analysis (weights are from random-effects analysis) and the horizontal line represents the 95 % CI. The centre of the open diamond indicates the summary estimate of the RR and its width represents the 95 % CI of the summary RR estimate. General abbreviations: SES, socio-economic status; Prev., prevalence (%); HP+, H. pylori-infected; BF, breast-feeding; NA, not available. Abbreviations for countries: BRA, Brazil; TWN, Taiwan, Republic of China; CZE, Czech Republic; DEU, Germany; EGY, Egypt; GBR, United Kingdom; IRL, Ireland; IRN, Islamic Republic of Iran; ITA, Italy; PER, Peru; TUR, Turkey. Abbreviations for tests: SA, test based on the detection of stool antigens; SI, test based on serum immunology; UBT, urea breath test. *In the World Bank statistics, Taiwan, Republic of China, is not listed as a separate country. However, for most indicators, Taiwan’s data are not added to the data for China, but it is added to the world aggregate and the high-income countries aggregate. Therefore, Taiwan was included along with other high-income settings

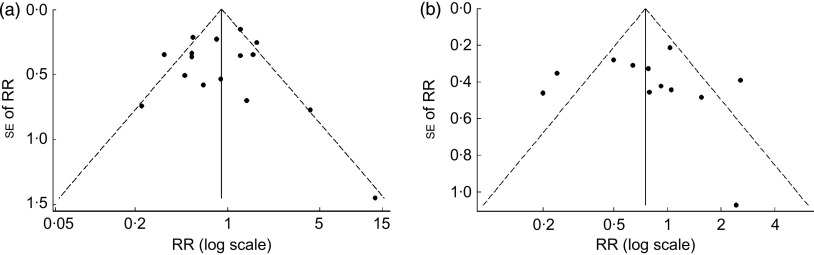

The visual inspection of the funnel plot did not suggest the occurrence of publication bias (Fig. 3). This is corroborated by the Egger’s asymmetry test (P=0·84).

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of studies evaluating the association between breast-feeding and Helicobacter pylori infection: (a) ever breast-feeding v. never; (b) breast-feeding for 4–6 months v. less than that. Studies were plotted with their relative risk (RR) estimate on the x-axis (log scale) and the corresponding standard error of the RR along the y-axis; pseudo 95 % confidence limits are represented by dashed lines

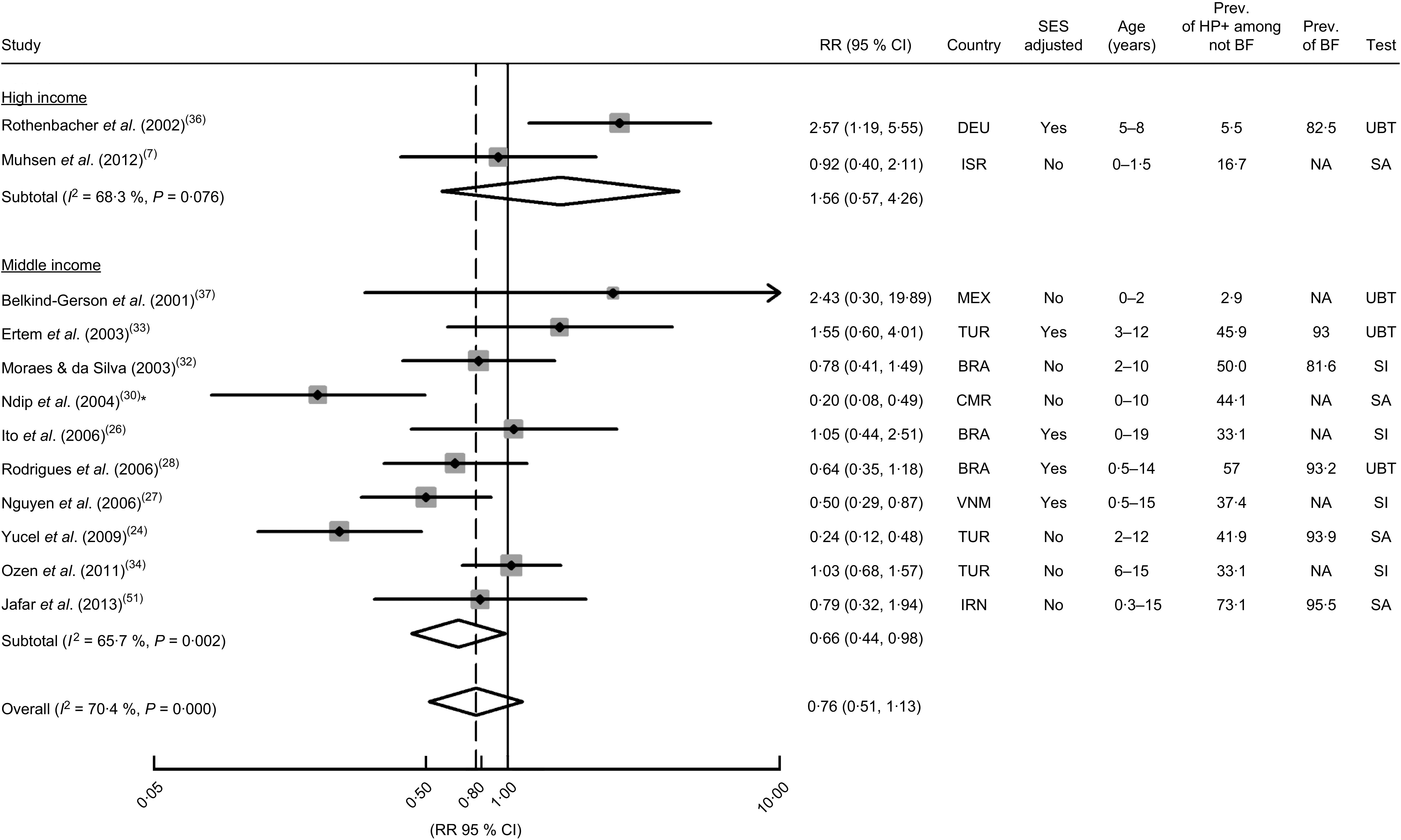

H. pylori infection according to duration of breast-feeding

Only two studies provided data to evaluate the association between being breast-fed for 4 months or more v. never breast-fed or breast-fed for less than 4–6 months in high-income settings( 7 , 36 ). The overall RR estimate was 1·56 (95 % CI 0·57, 4·26; I 2=68·3 %; Fig. 4). The single study that provided an RR estimate adjusted for confounders yielded an OR of 2·57 (95 % CI 1·19, 5·55).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analyses of studies evaluating the association between the duration of breast-feeding (<4–6 months v. >4–6 months) and Helicobacter pylori infection. Relative risk (RR) estimates and 95 % confidence intervals of H. pylori infection according to economic development of the countries where the investigations were conducted( 19 ). For each study, the black diamond indicates the best estimate, the size of the grey square indicates the study’s weight in the analysis (weights are from random-effects analysis) and the horizontal line represents the 95 % CI. The centre of the open diamond indicates the summary estimate of the RR and its width represents the 95 % CI of the summary RR estimate. General abbreviations: SES, socio-economic status; Prev., prevalence (%); HP+, H. pylori-infected; BF, breast-feeding; NA, not available. Abbreviations for countries: BRA, Brazil; CMR, Cameroon; DEU, Germany; IRN, Islamic Republic of Iran; IRS, Israel; MEX, Mexico; TUR, Turkey; VNM, Vietnam. Abbreviations for tests: SA, test based on the detection of stool antigens; SI, test based on serum immunology; UBT, urea breath test. *Study comparing those who were breast-fed for more than 6 months with those breast-fed for less than 2 months. A sensitivity analysis excluding this study yielded an overall RR estimate of 0·80 (95 % CI 0·54, 1·19; I 2=65·8 %)

The combined results of the ten studies conducted in middle-income settings showed a summary RR of 0·66 (95 % CI 0·44, 0·98; I 2=65·7 %). The summary RR was non-significant when considering the adjustment for potential confounding effect of socio-economic factors (adjusted: summary RR=0·77; 95 % CI 0·48, 1·20; I 2=40·5 %; unadjusted: summary RR=0·58; 95 % CI 0·30, 1·10; I 2=76·3 %), or the prevalence of H. pylori infection among the non-exposed subjects (using the median as cut-off; ≤43 %: summary RR=0·67; 95 % CI 0·35, 1·27; I 2=75·0 %; >43 %: summary RR=0·66; 95 % CI 0·38, 1·15; I 2=60·7 %). The three studies that used diagnostic tests based on the detection of stool antigens yielded lower RR estimates (summary RR=0·33; 95 % CI 0·15, 0·73; I 2=64·3 %), as did the seven studies with younger subjects (using the median as cut-off; ≤7 years: summary RR=0·50; 95 % CI 0·32, 0·78; I 2=56·7 %; >7 years: summary RR=1·09; 95 % CI 0·77, 1·55; I 2=0·0 %). The only cohort analysis showed a non-significant positive association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection (RR=2·54; 95 % CI 0·29, 22·40), although only six out of 110 children seroconverted during the 2-year follow-up period since birth( 37 ).

The visual inspection of the funnel plot and the results of the Egger’s asymmetry test (P=0·82) did not suggest publication bias (Fig. 3).

H. pylori infection according to history of exclusive breast-feeding

Two studies( 40 , 53 ), conducted in Ethiopia (low-income country) and in Chile (middle-income country), assessed the effect of exclusive breast-feeding for more than 6 months; the RR was 0·91 (95 % CI 0·61, 1·34) and 1·71 (95 % CI 0·66, 4·47) in the low- and middle-income setting, respectively.

Discussion

The available evidence on the relationship between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection is compatible with a protective effect in the less economically developed settings. However, only a few studies accounted for the potential confounding by socio-economic factors or assessed the effects of breast-feeding duration or exclusivity, precluding definite conclusions on this topic.

The present study updated a previous systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Chak et al.( 16 ) and the interpretation of our findings needs to take into account the evidence that was published since then, as well as the differences in the completeness of the search strategy and options for data synthesis. The present systematic review included eighteen studies( 7 , 22 – 26 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 50 – 55 ) that were not considered in the paper published by Chak et al.( 16 ); most of the studies were published since then and two( 25 , 37 ) were written in languages probably not considered in the previous review. However, due to our methodological options, six studies( 31 , 46 , 56 – 59 ) included in the previous meta-analysis were not included in our meta-analyses. The study by Suoglu et al. ( 58 ) was not eligible because the sample selection was not independent of the H. pylori status. The study by Braga et al. ( 59 ) included a sample that partially overlapped with the sample of the study by Rodrigues et al.( 28 ) and only the latter was considered in our review. The study by Mahalanabis et al. ( 46 ) defined the exposure as ‘presently receiving some breast milk’ although it also included children old enough for not being breast-fed for a long time and was therefore excluded from our analyses. We also opted for not including the studies evaluating the H. pylori infection status in adulthood( 31 , 56 , 57 ), as the larger the lag between the exposure to breast-feeding and the assessment of infection status, the more likely it is that the RR estimates reflect the effect of other factors in addition to breast-feeding, namely taking into account that the incidence rates may remain high throughout adolescence( 60 ).

The inclusion of a larger number of studies allowed a finer assessment of the exposure of breast-feeding. Chak et al. ( 16 ) provided a summary OR estimate combining the results of all eligible studies, regardless of the breast-feeding definition, and conducted stratified analysis according to the duration of breast-feeding (≥4 months v. <4 months or not specified). We opted for conducting two sets of analyses: (i) according to the breast-feeding status (ever breast-fed v. never breast-fed); and (ii) according to the duration of breast-feeding (≥4–6 months v. <4–6 months). Despite our efforts to combine the results from more homogeneous groups of studies, the inter-study variability in the estimates remained high. Among the studies that assessed the H. pylori status among those ever breast-fed and those who were never, the heterogeneity of the results is likely to be explained primarily by the differences implicit in the definition of ever having been breast-fed, which may include children breast-fed for one week or one year; however, the original reports did not provide information to account for these methodological aspects in our analyses. This depicts the need for standardized breast-feeding definitions to be used for the collection and description of data on this topic( 61 ). In 1988, the Interagency Group for Action on Breastfeeding( 62 ) recognized that the term ‘breast-feeding’ is not enough to accurately describe its numerous variations. Specifically, it is required to distinguish between full and partial breast-feeding, and between the different levels of partial breast-feeding( 62 ).

Our results suggest that having been breast-fed for 4–6 months is associated with a lower risk of H. pylori infection only in middle-income countries. We may hypothesize that in the latter settings children who are being breast-fed may present a substantially better nutritional status and therefore present more resistance to infections. Also, children whose mothers had breast milk with higher levels of anti-H. pylori IgA had a lower risk of H. pylori infection, compared with those whose mothers had lower levels( 21 ). Furthermore, breast-feeding may protect against the acquisition of the infection by acting as a natural antibiotic, as bovine lactoferrin was shown to inhibit the growth of H. pylori ( 63 – 65 ); lactoferrin is much more abundant in breast milk than it is in cow’s milk. Another component of breast milk, κ-casein, was shown to play a role in the inhibition of H. pylori adhesion to gastric mucosa( 66 ).

Although similar results were obtained when considering crude RR estimates with those adjusted for the potential confounding by socio-economic factors, this is a methodological aspect of major importance and a sound assessment of this relationship requires the control of these confounders. The relationship between low socio-economic status and H. pylori infection is well known( 67 , 68 ). Breast-feeding is also influenced by these factors, although the relationship may vary with time and across settings with different economic and cultural background( 69 – 71 ).

There was no association between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection when only the studies including older children were considered for analysis, which may reflect a lack of longer-term effects of breast-feeding, or that more important risk factors exert their effects after the cessation of breast-feeding.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest a protective effect of breast-feeding in economically less developed settings. However, further research is needed, with a finer assessment of the exposure to breast-feeding and infection status, as well as a careful control of confounding, before definite conclusions can be reached.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study was funded by a grant of the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (grant number PTDC/SAU-EPI/122460/2010). The Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia had no role in the design, analysis or writing of the article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: H.C. conceived the study and performed the collection and analyses of data under the supervision of N.L. at all stages of its implementation. A.B. and B.P. collaborated in data collection. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and review of drafts of the manuscript, and read and approved the final submission of the manuscript.

Appendix 1.

Main characteristics and results of the studies included in the systematic review but excluded from the meta-analysis

| Assessment of Helicobacter pylori status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, year of publication, reference | Country, region | Study population | Age (years): range; mean (sd) | Sample | Method | Description of the main findings | Reason for exclusion |

| Hestvik et al. (2010)( 41 ) | Uganda, Kampala | ‘In the Mulago II parish children aged 0–12 years were recruited consecutively by door-to-door visits, an equal number of children in each age category […]’ | 0–12; 4·8 (3·6) | Stool | Immunoassay | ‘There were no significant differences in prevalence by breastfeeding duration (shorter or longer than 24 weeks) […]’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Bhuiyan et al. (2009)( 47 ) | Bangladesh, Mirpur | ‘695 pregnant mothers were screened and 321 newborn children were enrolled. From this cohort, 238 children […] who had completed follow-up and from whom complete set of serum and stool specimens were available’ | Baseline: newborns Follow-up: 2 years | Blood Stool | ELISA | ‘There was no difference in the prevalence of H. pylori infection among children who were exclusively breast-fed in comparison with those who received mixed feedings when analyzing samples collected during the first 6 months of life (P=NS) (data not shown). Similarly, we could not find any relationship between H. pylori infection in children breast-fed after age 6 months and those who were not’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Siai et al. (2008)( 42 ) | Tunisia, Cap-Bon | ‘Among the 10,703 first-grade pupils identified in the healthcare centers’ databases, 1055 were randomly selected for inclusion (the first, 10th and 20th children on the health-center lists)’ | 6–7; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | ‘Statistically, there was no difference between infected and non infected children in terms of the following variables: […] duration of breastfeeding […]. Mean duration of breastfeeding: 12·48 months among H. pylori positive subjects; 11·85 months among H. pylori negative subjects’ | It compares the mean duration of breast-feeding among H. pylori-infected and non-infected subjects |

| Przybyszewska et al. (2006)( 43 ) | Poland, Cracow | ‘From 1999 until 2001 the study was carried out on randomly selected healthy children aged 6 months to 4 years, attending Healthy Child Centres in Cracovia for their immunization or physical assessment of their health’ | 0·5–4·3; 2·7 (0·98) | Expired air | UBT | ‘Also Hp infection was not dependent on […] breastfeeding […]’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Kivi et al. (2005)( 10 ) | Sweden, Stockholm | ‘The present cross-sectional study in an extension of a previous serological survey in 11 Stockholm schools, conducted between February and April 1998, investigating risk factors for H. pylori infection in children’ | 10–14; 12* (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | ‘No associations with index child infection were found for […] breastfeeding […]’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Vivatvakin et al. (2004)( 55 ) | Thailand, central, northern, north-eastern and eastern | ‘[…] sera of Thai children who visited the Out Patients Clinics […] were collected. […] The exclusion criteria were the children who had either blood or plasma transfusion and history of recurrent abdominal pain’ | 0–16; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA and Western blot (IgG) | ‘Percentage of breastfeeding in the population in Korat was 61·25 %. The selected group of seropositive children had 51 % of exclusive breastfeeding for more than 6 months and in only 21·5 % the seropositive children had a history of breastfeeding less than 6 months’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Glynn et al. (2002)( 44 ) | Bolivia, ND | ‘[…] we conducted a serosurvey (survey I) to establish baseline H. pylori seroprevalence rates […]. All children aged 6 months through 9 years were eligible to enroll in the health day activities, including testing for H. pylori […] we returned to the same 17 villages and conducted a second serosurvey (survey II). […] we restricted the enrollment in survey II to children aged ≤6 years’ | 0·5–9; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | ‘Behaviors associated with breast-feeding, including breast-feeding from multiple women or breast-feeding from a woman who was simultaneously nursing other children, also were not significantly associated with seroconversion’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Daugule et al. (2001)( 50 ) | Latvia, Riga | ‘Consecutive children […] without symptoms from the gastrointestinal tract, who visited their doctor for a general checkup or because of minor health problems’ | 1–12 | Expired air | UBT | ‘The univariate associations of some of the studied risk factors with H. pylori positivity are shown in the table. […] The other possible risk factors did not demonstrate a significant association with H. pylori infection’ (Breast-feeding was not included in the table) | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Okuda et al. (2001)( 48 ) | Japan, Wakayama | ‘This study included 484 children with no gastric symptoms, […] who were examined at Wakayama Rosai Hospital‘ | 0–12 | Stool | H. pylori stool antigen assay | ‘The mean period of breast-feeding of the HpSA positive group was 5·3±5·8 months, while the mean period for the HpSA negative group was 7·8±7·4 months (P=0·02). In the 198 children aged 1–3-years-old, the mean period of breast-feeding for the 14 HpSA positive children was 3·4±3·5 and for the 184 HpSA negative children was 8·5±6·9 months (P=0·003, Table 2)’ | It compares the mean duration of breast-feeding among H. pylori-infected and non-infected subjects |

| Rothenbacher et al. (2000)( 54 ) | Germany, Ulm, Langenau and Ehingen | ‘In this study we included all infants and children of Turkish nationality in whom 11 participating pediatricians […] conducted a screening examination’ | 0–5 | Stool | Enzyme immunoassay | ‘[…] history of breastfeeding showed no clear pattern with prevalence of current infection’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Tindberg et al. (1999)( 45 ) | Sweden, Stockholm | ‘children were recalled for serology of both pertussis and H. pylori infection and 201 of 305 identifiable children accepted. | 2, 4; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG, IgA) | ‘Length of breastfeeding, i.e. a mean of 3 mo for both seropositive and seronegative children, could not be correlated with later H. pylori infection status’ | An RR or suitable information to compute it was not provided |

| Mahalanabis et al. (1996)( 46 ) | Bangladesh, Nandipara | ‘The study was carried out in a periurban village named Nandipara […] settled by people of low socioeconomic status on government land. […] Infants and children over a wide age range 1–99 months were studied’ | 0·08–8·3; ND (ND) | Expired air | UBT | ‘The association between lack of breastfeeding and H. pylori infection could not be tested because infants and children under 3 years were nearly all breastfed. Although an association (significant at a 5 % level) was shown between breast-feeding and H. pylori infection in children over 5 years old, the significance of this finding is tenous and could be attributed to the effect of multiple comparison’ | The exposure category was ‘presently receiving some breast milk’. This exposure was assessed in groups of subjects with wide age ranges (1–3 months, 4–35 months, 36–59 months, 60–99 months) |

| Thomas et al. (1993)( 21 ) | Gambia, ND | ‘We have measured the potential protective effect of specific human milk IgA by studying 12 mothers and their infants from a Gambian village in which most infants are breast-fed throughout the first 2 years of life’ | 3–12 months | Expired air | UBT | ‘We found a relation between the concentration of specific breast milk IgA and the age of acquisition of H. pylori infection. By ranking mothers according to the level of anti-H-pylori IgA they secreted […] their children could be divided into two groups according to whether or not H pylori infection was diagnosed by 9 months of age (Kruskal–Wallis test, P=0·004). All 5 infected children at this age came from 5 mothers with the lowest specific breast milk IgA. By 12 months of age, only 3 children were infection free, including the children of the two mothers who produced the highest specific breast milk IgA (P=0·04)’ | It related the levels of IgA in the mothers and the acquisition of H. pylori infection in the first year of the child |

ND, not defined; RR, relative risk estimate; UBT, urea breath test.

*Median age.

Appendix 2.

Main characteristics and results of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Assessment of Helicobacter pylori status | RR estimates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, year of publication, reference | Country, region | Study population | Age (years): range; mean (sd) | Sample | Method | Breast-feeding prevalence among the study subjects | Duration of breast-feeding/other measures | Reference category used for RR estimation | Category of exposure used for RR estimation | RR (95 % CI) | Control for confounding |

| Jafar et al. (2013)( 51 ) | Iran, Sanandaj | ‘This cross-sectional study was based on samples of 4-month to 15-year-old children. […] The lower age groups were selected randomly from the healthy children who referred to primary healthcare centers for vaccination and the older ones were from 12 schools with different socioeconomic status across the city’ | 0·3–15; 5·6 (5·4) | Stool | Enzyme immune assay | 95·5 % | ND | No breast-feeding | Breast-feeding for <6 months | OR=0·62 (0·10, 3·66) | No |

| No breast-feeding | Breast-feeding for ≥6 months | OR=0·66 (0·21, 2·06) | No | ||||||||

| Not breast-fed or breast-fed for <6 months | Breast-fed for ≥6 months | OR=0·79 (0·32, 1·92) | No | ||||||||

| O’Ryan et al. (2013)( 53 ) | Chile, Colina | ‘Mother–infant pairs […] were enrolled during 2006 to 2007 in a 2-year cohort study. […] Only healthy 1-month-old infants were enrolled’ | Baseline: birth Median time of follow-up: 60 months | Stool | ELISA | ND | ND | Not exclusively breast-fed at 6 months | Exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months | OR=1·71 (0·66, 4·47) | No |

| Muhsen et al. (2012)( 7 ) | Israel, Northern region | ‘Mothers of healthy infants aged 1 week to 2 months […] were asked to participate […] Mothers of eligible infants […] were recruited through the local family health clinics between January and August 2007’ | 1·5; ND (ND) | Stool | Enzyme immune assay‡ | ND | ND | ≤6 months | >6 months | OR=0·92 (0·40, 2·11) | No |

| Ozen et al. (2011)( 34 ) | Turkey, ND | ‘Subjects for the study were selected from the school register […]’ | 6–15; 9·8 (2·0)† | Blood | ELISA | ND | ND | <4 months | 4–12 months | OR=1·07 (0·66, 1·74)|| | No |

| <4 months | >12 months | OR=1·00 (0·63, 1·59)|| | |||||||||

| <4 months | ≥4 months | OR=1·03 (0·69, 1·55)|| | No | ||||||||

| Miranda et al. (2010)( 22 ) | Brazil, São Paulo | ‘Children and adolescents were eligible for inclusion if they were registered at the outpatient service of Hospital São Paulo with a diagnosis of upper airway infection on week-days. All eligible individuals were invited to participate, without any sampling procedure’ | ND; 6·82 (4·07) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | 62·2 % | ND | No breast-feeding | Exclusive breast-feeding until 4 months of age | OR=0·83 (0·53, 1·31) | No |

| Sýkora et al. (2009)( 23 ) | Czech Republic, West Bohemia | ‘asymptomatic children, […] chosen prospectively from the general population’ | 0–15; ND (ND) | Stool | ELISA | 80·9 % | Among HP– subjects: 13·99 (sd 19·55) weeks Among HP+ subjects: 8·37 (sd 12·73) weeks | Never have been breast-fed | Ever have been breast-fed | OR=0·55 (0·36, 0·84)¶ | No (the OR estimate remained not statistically significant after age adjustment) |

| Yucel et al. (2009)( 24 ) | Turkey, Northern region | ‘children belonging to […] the outpatient clinic of a university medical center, and samples were collected from subjects who included the children of academic staff members. […] The second site was a public health center located in the city center […]. The last site was a public health center […]’ | 2–12; 6·8 (3·0) | Stool | Immunochromatographic assay | Prevalence of breast-feeding by duration: None: 6·0 % 0–6 months: 49·1 % 0–12 months: 15·7 % 0–24 months: 23·7 % 0–48 months: 5·5 % | A statistical correlation was found between the duration of breast-feeding and H. pylori positivity, but it was not significant (P=0·02; 95 % CI 0·517, 7·349; r=−0·18) | Never have been breast-fed or breast-fed for less than 6 months | Breast-fed for more than 6 months | OR=0·24 (0·12, 0·48)|| | No |

| Rodrigues et al. (2007)( 25 ) | Brazil, Porto Velho | ‘children […] selected from a private clinic and outpatient services in surrounding neighbourhoods. […] the inclusion criteria were: […] need of venopunction for laboratory complementary exams […]’* | 2–13; 7·7 (ND) | Blood | Enzyme immune assay | 92·5 % | ND | Never breast-fed | Ever breast-fed | OR=4·24 (0·93, 19·32)|| | No |

| Ito et al. (2006)( 26 ) | Brazil, São Paulo | ‘The subjects of this study were volunteers with apparently good health conditions. The family units in this study were defined as husband, wife, and at least one nonadopted child aged between 0 and 19 years. The study required that both parents were Japanese or Japanese descendants whose family members all lived in the same household’ | 0–19; ND (ND) | Blood | Anti-H. pylori IgG antibody test | ND | ND | Breast-fed less frequent than 6 months | ≥6 months | OR=1·05 (0·44, 2·51) | Adjusted: for age and sex |

| Nguyen et al. (2006)( 27 ) | Vietnam, Northern region | ‘Every consecutive outpatient aged more than 6 months and less than 15 years presenting every Wednesday at the pediatric department of a university hospital was included. However, children with acute diarrhea, ulcer disease, and repeated abdominal pain or immunocompromised status were excluded’ | 0·5–15; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | ND | ND | Breast-feeding for ≤6 months | Breast-feeding for >6 months | OR=0·6 (0·4, 0·8) | No |

| Breast-feeding for ≤6 months | Breast-feeding for >6 months | OR=0·5 (0·3, 0·9) | Adjusted for: age (3–6 years, >6 years) and offspring number >1 | ||||||||

| Rodrigues et al. (2006)( 28 ) | Brazil, Ceará, Fortaleza | ‘[…] involving a community in Parque Universitário […] All houses in the community had been previously numbered and households to be surveyed were chosen by means of a table of random numbers. Children […] as well as their mothers were invited to participate in the study’ | 0·5–14; ND (ND) | Expired air | UBT | 93·2 % | ND | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=1·12 (0·45, 2·82) | No** |

| Breast-fed ≤6 months | Breast-fed >6 months | OR=0·86 (0·56, 1·35) | No** | ||||||||

| Breast-fed | Not breast-fed | OR=0·89 (0·31, 2·56)||,¶ | Adjusted for: H. pylori status of the mother, age, nutritional status, education of the mother, history of antibiotic use, smoking of the mother, number of persons per room and number of children per household | ||||||||

| Breast-fed ≤6 months | Breast-fed >6 months | OR=0·64 (0·35, 1·18) | |||||||||

| Rowland et al. (2006)( 29 ) | Ireland, Dublin, Mallow and Kingscourt | ‘Nineteen family doctors were approached to provide patients for the study […] Parents of eligible children were invited by letter from their family doctor to participate in this study’ | Baseline: 2–4; 2·75 (0·6) | Expired air | UBT | 35 % | There was no difference in the rate or duration of breast-feeding between infected and non-infected index children | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=0·54 (0·26, 1·09) | No |

| Ndip et al. (2004)( 30 ) | Cameroon, Buea and Limbe | ‘The study population consisted of 176 apparently healthy children […]. Eighty eight children were sampled from each of the two study sites’ | 0–10; 4·29 (ND) | Stool | ELISA | ND | ND | Breast-fed for ≤2 months | Breast-fed for ≥6 months | OR=0·20 (0·08, 0·49)|| | No |

| Moraes and da Silva (2003)( 32 ) | Brazil, Pernambuco | ’A cross-sectional study was done […] then, we did a comparative study between the seropositive children and the seronegative children of HP. The sample was non probabilistic, of convenience, meaning all children who presented during the morning shift in the outpatient clinic of Pediatrics since the day of start of the study […]’* | 2–10; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | 81·6 % | ND | Never breast-fed | ≤4 months ≥5 months | OR=0·78 (0·41, 1·49) | No |

| Ertem et al. (2003)( 33 ) | Turkey, ND | ‘[…] in a population of pre-school and school-aged healthy children […]’ | 3–12; 8·2 (2·1) | Expired air | UBT | 93·0 % | ND | Not breast-fed | ≤1 month | OR=1·09 (0·43, 2·76)|| | No |

| 2–3 months | OR=0·59 (0·23, 1·53)|| | ||||||||||

| 4–5 months | OR=0·65 (0·26, 1·64)|| | ||||||||||

| 6–24 months | OR=1·55 (0·60, 4·02)|| | ||||||||||

| Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=0·22 (0·05, 0·96)¶ | Adjusted for: socio-economic class (high, middle, low), number of siblings (none, 1, ≥2), heating system (central heating, coal-stove), age, percentile values for weight and height, household density, education of parents | ||||||||

| Dore et al. (2002)( 35 ) | Italy, urban area: Sardinia, Porto Torres | ‘A cross-sectional study of H. pylori prevalence was conducted among elementary and middle school children who lived in the same region but in different settings (rural v. urban)’ | 5–16; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | 70–75 % | ND | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=1·25 (0·92, 1·69)¶ | Adjusted for: age, sex, occupational category for the head of household, ownership of animals, day care attendance |

| Dore et al. (2002)( 35 ) | Italy, rural area: Sardinia, Alà dei Sardi, Bono, Padria, Buddusò, Sedini, Laerru, and Nughedu | ‘A cross-sectional study of H. pylori prevalence was conducted among elementary and middle school children who lived in the same region but in different settings (rural v. urban)’ | 5–16; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | 70–75 % | ND | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=1·67 (1·01, 2·76)¶ | Adjusted for: age, sex, occupational category for the head of household, ownership of animals, day care attendance |

| Rothenbacher et al. (2002)( 36 ) | Germany, Ulm | ‘[…] 1201 children who were to attend first grade in the school year 1997/98 and who lived within the city limits of Ulm’ | 5–8; 5·9 (0·46) | Expired air | UBT | 82·5 % 33·1 % of the children were exclusively breast-fed until 3 months 17 % were exclusively breast-fed for ≥6 months 36·7 % were breast-fed for ≥6 months | ND | Never breast-fed | Ever breast-fed | OR=1·22 (0·68, 2·22)** | No |

| Never breast-fed | Ever breast-fed | OR=1·67 (0·89, 3·14)** | Adjusted for: H. pylori status of the mother | ||||||||

| Never breast-fed | Ever breast-fed | OR=1·56 (0·79, 3·11) | Adjusted for: H. pylori status of the mother, nationality, age, sex, place of birth, birth weight, education of the father, education of the mother, history of antibiotic use, housing density, number of siblings, household smoking of mother, household smoking of father | ||||||||

| Never breast-fed | <3 months | OR=1·07 (0·47, 2·46) | |||||||||

| 3–6 months | OR=1·19 (0·52, 2·75) | ||||||||||

| ≥6 months | OR=2·57 (1·19, 5·55) | ||||||||||

| Belkind-Gerson et al. (2001)( 37 ) | Mexico, Morelos, Cuernavaca | ‘A birth cohort study followed up during the first years of life. Blood from 100 healthy children who were presented to in the Hospital del Ninõ Morelense to routine immunization […]’* | Baseline: 2 months Followed up to 24 months | Blood | ELISA§ | ND | ND | Breast-fed for less than 6 months | Breast-fed for at least 6 months | RR=2·43 (0·30, 20·1) | No |

| Malaty et al. (2001)( 11 ) | USA, Houston | ‘The study involved 13 licensed day care centers from different locations in Houston. […] Children 15 years old attended day care centers in the late afternoon, after regular school hours, and in the morning before school. […] The sampling of the study was not random but depended on invitation and eligibility as determined by the entry criteria’ | 2–16; ND (ND) | Expired air | UBT | 62·9 % | ND | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=0·33 (0·17, 0·66)¶ | Adjusted for: age |

| Omar et al. (2001)( 38 ) | Egypt, Cairo | ‘Children attending the pediatric outpatient clinic of Damanhour Teaching Hospital for minor illnesses during a six months period’ | 1·5–16; 6·8 (3·7) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | ND | ND | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=0·48 (0·18, 1·29)¶ | No |

| Breast-fed for ≥12 months | Breast-fed for <12 months | OR=4·3 (1·5, 125·6) | Adjusted for: age and bed sharing | ||||||||

| Naficy et al. (2000)( 39 ) | Egypt, Abu Homos | ‘[…] a house-to-house census of the study population was performed […] Following the census, all children under 24 months and new births into the censused housed were eligible for enrolment into the cohort’ | 0·5–2·9; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | ND | ND | Never breast-fed | Ever breast-fed | OR=1·4 (0·37, 5·8) | Adjusted for: age |

| Lindkvist et al. (1999)( 40 ) | Ethiopia, 9 highland and lowland villages and the town Butajira situated in the Rift Valley | ‘The children were selected randomly by computer from the BRHP database, and only one sibling from each family was selected. (…)’ | Baseline: 1·8–4; 2·9 (ND) End of 30-month follow-up: 4·3–6·5; 5·5 (ND) | Blood | Immunoblot assay | ND | ND | Exclusive breast-feeding <6 months | Exclusive breast-feeding ≥6 months | RR=0·91 (0·61, 1·34) | No |

| Gold et al. (1997)( 49 ) | Republic of China, Taiwan, Taipei | ‘Study subjects have been enrolled voluntarily from a group of Taiwanese women and infants entered in a hepatitis B vaccine efficacy study at the National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan’ | Baseline: birth date End of follow-up: 14 months of age | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | 28 % | ‘Forty-eight of the 80 infants were H. pylori-positive at birth (i.e. blood drawn at 3 d of life); all of those had seropositive mothers. Ninety four percent of the infants with evidence of passive transfer of maternal IgG antibodies showed no detectable antibodies by 3 mo of age and 98 % of these infants by 6 mo of age’ | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=13·2 (1·2, 347) | No (this association remained when analysis was limited to those infants whose mothers were the primary care givers) |

| McCallion et al. (1996)( 12 ) | Ireland, Belfast | ‘children […] attending the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children for routine non-gastrointestinal day surgery’ | 3–15; ND (ND) | Blood | ELISA (IgG) | 20·2 % | There was a significant negative association between infection and breast feeding | Never breast-fed or breast fed for less than 2 weeks | Breast fed for 2 weeks or longer | OR=0·52 (0·29, 0·96)||,** | No |

| OR=0·54 (0·28, 1·06) | Adjusted for: age, social class and housing density | ||||||||||

| Klein et al. (1991)( 52 ) | Peru, San Juan de Miraflores | ‘266 children from families of low socioeconomic status (recruited at local health posts) and 141 children from families of high economic status (recruited from private schools, churches, and social organisations) were studied. Children from families of low socioeconomic status were regarded as representative of the community population on the basis of family demographic comparisons with randomly selected age-matched children from the same region’ | 0·16–12; ND (ND) | Expired air | UBT | 65·1 % | ND | Not breast-fed | Breast-fed | OR=1·25 (0·62, 2·52) | No |

RR, relative risk; ND, not defined; HP, Helicobacter pylori; UBT, urea breath test.

*Translated from original language to English by the authors of the present review.

†Weighted mean of the mean age of H. pylori-positive and -negative subjects.

‡H. pylori infection was defined as having at least two positive tests at examinations obtained at age 6 months or later.

§Only considered H. pylori infection when the test was positive after the age of 6 months.

||Estimates computed from the information presented in the paper.

¶Study providing OR estimates for the comparison of the subjects who were never breast-fed with those who were ever breast-fed. To estimate OR for the comparison of those who were ever breast-fed with those who were never, we computed the inverse of the OR and the respective 95 % CI.

**OR estimate not considered for meta-analysis.

References

- 1. Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group (2001) Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut 49, 347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. International Agency for Research on Cancer & World Health Organization (2009) A Review of Human Carcinogens. Part B: Biological Agents/IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon: IARC. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asfeldt AM, Straume B, Steigen SE et al. (2008) Changes in the prevalence of dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori infection after 17 years: the Sorreisa gastrointestinal disorder study. Eur J Epidemiol 23, 625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gause-Nilsson I, Gnarpe H, Gnarpe J et al. (1998) Helicobacter pylori serology in elderly people: a 21-year cohort comparison in 70-year-olds and a 20-year longitudinal population study in 70–90-year-olds. Age Ageing 27, 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S et al. (2012) Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol 13, 607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koch A, Krause TG, Krogfelt K et al. (2005) Seroprevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Greenlanders. Helicobacter 10, 433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muhsen K, Jurban M, Goren S et al. (2012) Incidence, age of acquisition and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection among Israeli Arab infants. J Trop Pediatr 58, 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oleastro M, Pelerito A, Nogueira P et al. (2011) Prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a healthy pediatric population in the Lisbon area. Helicobacter 16, 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sherman PM (2004) Appropriate strategies for testing and treating Helicobacter pylori in children: when and how? Am J Med 117, Suppl. 5A, 30S–35S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kivi M, Johansson AL, Reilly M et al. (2005) Helicobacter pylori status in family members as risk factors for infection in children. Epidemiol Infect 133, 645–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malaty HM, Logan ND, Graham DY et al. (2001) Helicobacter pylori infection in preschool and school-aged minority children: effect of socioeconomic indicators and breast-feeding practices. Clin Infect Dis 32, 1387–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCallion WA, Murray LJ, Bailie AG et al. (1996) Helicobacter pylori infection in children: relation with current household living conditions. Gut 39, 18–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bastos J, Carreira H, La Vecchia C et al. (2013) Childcare attendance and Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev 22, 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quigley MA, Kelly YJ & Sacker A (2007) Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics 119, e837–e842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wright AL, Bauer M, Naylor A et al. (1998) Increasing breastfeeding rates to reduce infant illness at the community level. Pediatrics 101, 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chak E, Rutherford GW & Steinmaus C (2009) The role of breast-feeding in the prevention of Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 48, 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8, 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JP & Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21, 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The World Bank (2012) The World Bank Database – Countries and Economies. http://data.worldbank.org/country (accessed November 2012).

- 20. Sterne JA, Gavaghan D & Egger M (2000) Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol 53, 1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas JE, Austin S, Dale A et al. (1993) Protection by human milk IgA against Helicobacter pylori infection in infancy. Lancet 342, 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miranda AC, Machado RS, Silva EM et al. (2010) Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among children of low socioeconomic level in Sao Paulo. Sao Paulo Med J 128, 187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sýkora J, Siala K, Varvarovska J et al. (2009) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic children: a prospective population-based study from the Czech Republic. Application of a monoclonal-based antigen-in-stool enzyme immunoassay. Helicobacter 14, 286–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yucel O, Sayan A & Yildiz M (2009) The factors associated with asymptomatic carriage of Helicobacter pylori in children and their mothers living in three socio-economic settings. Jpn J Infect Dis 62, 120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodrigues RV, Corvelo TC & Ferrer MT (2007) Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among children of different socioeconomic levels in Porto Velho, State of Rondonia. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 40, 550–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ito LS, Oba-Shinjo SM, Shinjo SK et al. (2006) Community-based familial study of Helicobacter pylori infection among healthy Japanese Brazilians. Gastric Cancer 9, 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nguyen BV, Nguyen KG, Phung CD et al. (2006) Prevalence of and factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in children in the north of Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74, 536–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodrigues MN, Queiroz DM, Braga AB et al. (2006) History of breastfeeding and Helicobacter pylori infection in children: results of a community-based study from northeastern Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 100, 470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rowland M, Daly L, Vaughan M et al. (2006) Age-specific incidence of Helicobacter pylori . Gastroenterology 130, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ndip RN, Malange AE, Akoachere JF et al. (2004) Helicobacter pylori antigens in the faeces of asymptomatic children in the Buea and Limbe health districts of Cameroon: a pilot study. Trop Med Int Health 9, 1036–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ueda M, Kikuchi S, Kasugai T et al. (2003) Helicobacter pylori risk associated with childhood home environment. Cancer Sci 94, 914–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moraes MM & da Silva GA (2003) Risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in children. J Pediatr (Rio J) 79, 21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ertem D, Harmanci H & Pehlivanoglu E (2003) Helicobacter pylori infection in Turkish preschool and school children: role of socioeconomic factors and breast feeding. Turk J Pediatr 45, 114–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ozen A, Furman A, Berber M et al. (2011) The effect of Helicobacter pylori and economic status on growth parameters and leptin, ghrelin, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I concentrations in children. Helicobacter 16, 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dore MP, Malaty HM, Graham DY et al. (2002) Risk factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection among children in a defined geographic area. Clin Infect Dis 35, 240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rothenbacher D, Bode G & Brenner H (2002) History of breastfeeding and Helicobacter pylori infection in pre-school children: results of a population-based study from Germany. Int J Epidemiol 31, 632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Belkind-Gerson J, Basurto G, Newton O et al. (2001) Incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of infants in the State of Morelos. Salud Publica Mex 43, 122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Omar AA, Ibrahim NK, Sarkis NN et al. (2001) Prevalence and possible risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection among children attending Damanhour Teaching Hospital. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 76, 393–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naficy AB, Frenck RW, Abu-Elyazeed R et al. (2000) Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a population of Egyptian children. Int J Epidemiol 29, 928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lindkvist P, Enquselassie F, Asrat D et al. (1999) Helicobacter pylori infection in Ethiopian children: a cohort study. Scand J Infect Dis 31, 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hestvik E, Tylleskar T, Kaddu-Mulindwa DH et al. (2010) Helicobacter pylori in apparently healthy children aged 0–12 years in urban Kampala, Uganda: a community-based cross sectional survey. BMC Gastroenterol 10, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Siai K, Ghozzi M, Ezzine H et al. (2008) Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Tunisian children: 1055 children in Cap-Bon (northeastern Tunisia). Gastroenterol Clin Biol 32, 881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Przybyszewska K, Bielanski W & Fyderek K (2006) Frequency of Helicobacter pylori infection in children under 4 years of age. J Physiol Pharmacol 57, Suppl. 3, 113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Glynn MK, Friedman CR, Gold BD et al. (2002) Seroincidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of rural Bolivian children: acquisition and analysis of possible risk factors. Clin Infect Dis 35, 1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tindberg Y, Blennow M & Granstrom M (1999) Clinical symptoms and social factors in a cohort of children spontaneously clearing Helicobacter pylori infection. Acta Paediatr 88, 631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mahalanabis D, Rahman MM, Sarker SA et al. (1996) Helicobacter pylori infection in the young in Bangladesh: prevalence, socioeconomic and nutritional aspects. Int J Epidemiol 25, 894–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bhuiyan TR, Qadri F, Saha A et al. (2009) Infection by Helicobacter pylori in Bangladeshi children from birth to two years: relation to blood group, nutritional status, and seasonality. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okuda M, Miyashiro E, Koike M et al. (2001) Breast-feeding prevents Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood. Pediatr Int 43, 714–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gold BD, Khanna B, Huang LM et al. (1997) Helicobacter pylori acquisition in infancy after decline of maternal passive immunity. Pediatr Res 41, 641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Daugule I, Rumba I, Lindkvist P et al. (2001) A relatively low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a healthy paediatric population in Riga, Latvia: a cross-sectional study. Acta Paediatr 90, 1199–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jafar S, Jalil A, Soheila N et al. (2013) Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children, a population-based cross-sectional study in west Iran. Iran J Pediatr 23, 13–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klein PD, Graham DY, Gaillour A et al. (1991) Water source as risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection in Peruvian children. Gastrointestinal Physiology Working Group. Lancet 337, 1503–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. O’Ryan ML, Rabello M, Cortes H et al. (2013) Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori detection in stools during the first 5 years of life in Chile, a rapidly developing country. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rothenbacher D, Inceoglu J, Bode G et al. (2000) Acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection in a high-risk population occurs within the first 2 years of life. J Pediatr 136, 744–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vivatvakin B, Theamboonlers A, Semakachorn N et al. (2004) Prevalence of CagA and VacA genotype of Helicobacter pylori in Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai 87, 1327–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pearce MS, Thomas JE, Campbell DI et al. (2005) Does increased duration of exclusive breastfeeding protect against Helicobacter pylori infection? The Newcastle Thousand Families Cohort Study at age 49–51 years. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 41, 617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fall CH, Goggin PM, Hawtin P et al. (1997) Growth in infancy, infant feeding, childhood living conditions, and Helicobacter pylori infection at age 70. Arch Dis Child 77, 310–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Suoglu OD, Gokce S, Saglam AT et al. (2007) Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastroduodenal disease, epidemiologic factors and iron-deficiency anemia in Turkish children undergoing endoscopy, and impact on growth. Pediatr Int 49, 858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Braga AB, Fialho AM, Rodrigues MN et al. (2007) Helicobacter pylori colonization among children up to 6 years: results of a community-based study from Northeastern Brazil. J Trop Pediatr 53, 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bastos J, Peleteiro B, Pinto H et al. (2013) Prevalence, incidence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of Portuguese adolescents (EpiTeen). Dig Liver Dis 45, 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Labbok MH & Starling A (2012) Definitions of breastfeeding: call for the development and use of consistent definitions in research and peer-reviewed literature. Breastfeed Med 7, 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Labbok M & Krasovec K (1990) Toward consistency in breastfeeding definitions. Stud Fam Plann 21, 226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dial EJ, Hall LR, Serna H et al. (1998) Antibiotic properties of bovine lactoferrin on Helicobacter pylori . Dig Dis Sci 43, 2750–2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang X, Hirmo S, Willen R et al. (2001) Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori infection by bovine milk glycoconjugates in a BAlb/cA mouse model. J Med Microbiol 50, 430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dial EJ & Lichtenberger LM (2002) Effect of lactoferrin on Helicobacter felis induced gastritis. Biochem Cell Biol 80, 113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hamosh M (1998) Protective function of proteins and lipids in human milk. Biol Neonate 74, 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ford AC & Axon AT (2010) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter 15, Suppl. 1, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Graham DY, Malaty HM, Evans DG et al. (1991) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in an asymptomatic population in the United States. Effect of age, race, and socioeconomic status. Gastroenterology 100, 1495–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Imdad A, Yakoob MY & Bhutta ZA (2011) Effect of breastfeeding promotion interventions on breastfeeding rates, with special focus on developing countries. BMC Public Health 11, Suppl. 3, S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Inoue M, Binns CW, Otsuka K et al. (2012) Infant feeding practices and breastfeeding duration in Japan: a review. Int Breastfeed J 7, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lunet N & Barros H (2012) Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: facing the enigmas. Int J Cancer 106, 953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]