Abstract

Context

Mutations in WNT1 can cause rare inherited disorders such as osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) and early-onset osteoporosis (EOOP). Owing to its rarity, the clinical characteristics and pathogenic mechanism of WNT1 mutations remain unclear.

Objective

We aimed to explore the phenotypic and genotypic spectrum and treatment responses of a large cohort of patients with WNT1-related OI/OP and the molecular mechanisms of WNT1 variants.

Methods

The phenotypes and genotypes of patients and their responses to bisphosphonates or denosumab were evaluated. Western blot analysis, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and immunofluorescence staining were used to evaluate the expression levels of WNT1, total β-catenin, and type I collagen in the tibial bone or skin from one patient.

Results

We included 16 patients with 16 mutations identified in WNT1, including a novel mutation. The types of WNT1 mutations were related to skeletal phenotypes, and biallelic nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations could lead to an earlier occurrence of fragility fractures and more severe skeletal phenotypes. Some rare comorbidities were identified in this cohort, including cerebral abnormalities, hematologic diseases, and pituitary adenoma. Bisphosphonates and denosumab significantly increased the spine and proximal hip BMD of patients with WNT1 mutations and reshaped the compressed vertebrae. We report for the first time a decreased β-catenin level in the bone of patient 10 with c.677C > T and c.502G > A compared to the healthy control, which revealed the potential mechanisms of WNT1-induced skeletal phenotypes.

Conclusion

Biallelic nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations of WNT1 could lead to an earlier occurrence of fragility fractures and a more severe skeletal phenotype in OI and EOOP induced by WNT1 mutations. The reduced osteogenic activity caused by WNT pathway downregulation could be a potential pathogenic mechanism of WNT1-related OI and EOOP.

Keywords: WNT1 variants, pathogenic mechanism, osteogenesis imperfecta, early-onset osteoporosis

The skeleton undergoes constant remodeling, which is essential to maintain the structural and biomechanical integrity of bone (1). Multiple signaling pathways precisely regulate bone remodeling, and the canonical WNT signaling pathway plays a critical role. Biallelic loss-of-function mutations in LRP5, which encodes the WNT coreceptor low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 5 (LRP5), can cause osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome, while heterozygous gain-of-function mutations in LRP5 are associated with high bone mass (2). Mutations in SOST, which encodes sclerostin, an inhibitor of canonical WNT signaling, can induce high bone mass (2). These studies demonstrate the key role of canonical WNT signaling in regulating human bone remodeling.

WNT proteins belong to a family of 19 glycolipoproteins that play a vital role in developmental and regenerative processes in numerous tissues. WNT signaling is critical for bone formation, as it regulates the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of osteoblasts (3). WNT ligands interact with frizzled (FZD) receptors and LRP5/6 on osteoblast membranes and activate the canonical WNT pathway, leading to stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus, where it binds to the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor-1 (TCF/LEF-1) transcription factors and initiates the transcription of target genes. WNT1 is a key ligand in bone, and mutations in WNT1 (OMIM: 164820) give rise to either autosomal-recessive osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) type XV or autosomal-dominant early-onset osteoporosis (EOOP) (4), which is characterized by recurrent fragility fractures, variable bone deformities, and short stature (4-13). To date, the genotype-phenotype correlation among patients with WNT1 mutations has not been established because of the rarity and phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of the disease (5, 14). The limited availability of patient-derived bone tissue also impedes our understanding of the expression of mutant WNT1 and the changes in WNT pathway in these patients, which is essential for elucidating the pathogenesis of WNT1 mutations in OI and EOOP.

Here, we investigated the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum and treatment responses in a relatively large cohort of patients with WNT1-induced OI or EOOP. We performed in silico prediction of mutant WNT1 proteins and explored the underlying pathogenic mechanism of WNT1 mutations through a series of functional studies using patient-derived bone and skin samples.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We recruited patients with OI or EOOP from the endocrinology department of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) from 2010 to 2022. The study protocol was approved by the scientific ethics committee of PUMCH (ethics committee approval code: JS-2081). Written informed consent forms were signed by the patients or their legal guardians before participation.

Assessments of Phenotypes

Clinical data of patients were obtained by retrospective chart review and reports. Height and weight were measured with a Harpenden stadiometer (Seritex Inc), and the data were converted to age- and sex-specific Z scores according to growth reference data for Chinese children (15).

Fasting blood samples were collected from 8 to 9 Am serum levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP, a bone formation marker) were detected with a fully automated chemical analyzer (ADVIA 1800, Siemens Inc). Serum levels of cross-linked C-telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX, a bone resorption marker) were measured with an automated Roche electrochemiluminescence system (E170; Roche Diagnostics). All biochemical parameters were detected in the central laboratory of PUMCH.

Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (GE Lunar Prodigy Advance, GE Healthcare), and the BMD of children was measured with special pediatric software. The region of interest for BMD measurement included the lumbar spine (LS; L2-L4) and proximal hip, and the results were converted to age- and sex-matched Z scores according to the reference data for normal Chinese and Asian children (16, 17). The precision of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements (coefficients of variation) was 0.94%, 1.75%, and 0.74% at the LS, femoral neck (FN), and total hip (TH), respectively (18). Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) were independently defined by 2 blinded radiologists according to the Genant semiquantitative method on the basis of lateral thoracic and LS radiographs (19). Therefore, VCFs were graded as grade 0 (normal or < 20% reduction in height), grade 1 (a 20%-25% reduction in height), grade 2 (a 25%-40% reduction in height), and grade 3 (a ≥ 40% reduction in height). Peripheral fractures were suspected based on medical history and confirmed by x-ray films.

Treatment and Follow-up of Patients

Adults and children with body weight greater than 25 kg received 5 mg intravenous zoledronate acid (Aclasta, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) annually or 70 mg oral alendronate (Fosamax, Merck) once weekly or 60 mg subcutaneous denosumab (Prolia, Amgen) every 6 months, depending on the severity of OI or EOOP, and the wishes of the patients or their parents. Five children with body weight less than or equal to 25 kg (patients 1-4 and 12) received a half dose of zoledronic acid or denosumab. In addition, all patients received daily supplementation with 300 to 600 mg of calcium and 0.25 μg of calcitriol. Follow-up data were available for 15 patients.

Detection of Gene Mutations

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral white blood cells of patients using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Gene mutations were identified by next-generation sequencing (Illumina HiSeq2000 platform, Illumina Inc), and the protocol has been previously described in detail (20). Alignment was performed with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner software. Variants were filtered out according to their genomic position, predicted effect, and frequency in the general population from dbSNP, HapMap, 1000G ASN AF, ESP6500 AF, ExAC, and 1000 Genomes. The mutations identified by next-generation sequencing were subsequently confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Primers specific from the genomic sequence (NG_033141.1) were designed using Primer 3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/; Supplementary Table S1) (21). The first intervening sequence (IVS-1) and exons 2 to 4 of WNT1 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles at 95 °C for 30 seconds, 58.5 to 61.5 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 40 to 100 seconds. PCR products were purified and sequenced with an ABI 377 DNA automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing traces were aligned with the NCBI reference sequence of WNT1 (NM_005430.4).

Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org) and PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) were used to predict the functional effects of the mutations. The pathogenicity of the variants was assessed according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) Standards and Guidelines (22).

Prediction of the Effects of WNT1 Mutations on Protein Structures

The predicted 3-dimensional (3D) structure of the WNT1 protein (AF-P04628-F1) was retrieved from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AlphaFold DB, https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk) (23, 24). To obtain and visualize the 3D mutant protein, mutagenesis was performed with PyMol (Schrodinger LLC). The “Zoom” function was used to visualize the variable region of the structural 3D alignments.

Histological Analysis of the Tibia

Tibial bone specimens were obtained from patient 10 with OI who was aged 27 years and underwent lower-limb orthopedic surgery after 3 infusions of zoledronic acid. A control bone sample was obtained from an age- and sex-matched individual with a normal bone phenotype and without WNT1 mutations. The bone samples were immediately fixed, immersed in 70% ethanol, and embedded undecalcified in modified methyl methacrylate. Sections (10-μm thick) were cut using a microtome (Leica RM2016, Leica Microsystems) and deplasticized, and resin was removed before staining. The bone sections were stained with Goldner trichrome (Servicebio, catalog No. G1064) to identify osteoid and mature bone, and with toluidine blue staining (Servicebio, catalog No. GP1052) to visualize osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

Evaluation of the Protein Expression Levels of WNT1 in Bone

Semiquantitative analysis of β-catenin and WNT1 in the bone of patient 10 and the control was performed by Western blotting. Bone samples were milled into a powder in liquid nitrogen. To extract the protein from the bone samples, the bone powder was lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 1 mM PMSF and Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The protein concentration was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein was loaded onto 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and then transferred to poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes. After being blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin, the membranes were incubated with anti-WNT1 (catalog No. 27935-1-AP, RRID: AB_2881013, Proteintech, 1:1000 dilution), anti-β-catenin (catalog No. 17565-1-AP, RRID: AB_2088102, Proteintech, 1:5000 dilution), or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; catalog No. ab8245, RRID: AB_2107448, Abcam, 1:1000 dilution) and then washed with TBST 3 times, followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (catalog No. ab205718, RRID: AB_2819160, Abcam, 1:5000 dilution). Finally, the immunoblots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Transcriptional Expression Analysis of COL1A1 in Fibroblasts

Dermal fibroblasts were isolated from the skin tissue of patient 10 and the normal control. The skin samples were treated with dispase II (2.4 U/mL, Solarbio) to separate the epidermis and dermis. The dermis was digested with 0.2% (w/v) type I collagenase (Gibco), and filtered through a 100-µm filter to remove the residual debris. Fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (1% pen-strep).

Total RNA was extracted from dermal fibroblasts in triplicate with TRIzol reagent, followed by complementary DNA synthesis using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara). The expression level of COL1A1 was quantified by quantitative (q)PCR using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus, Takara) on a Viia 7 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2 (21). Relative messenger RNA expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to the internal control GAPDH.

Evaluation of the Subcellular Distribution of COL1A1

To analyze the organization of type I collagen, fibroblasts were grown to confluence on glass coverslips and then treated with 200 μM ascorbic acid for 5 days, and finally fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The matrix was blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline plus 0.02% Tween 20 and incubated with anti-collagen I (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog No. C2456, RRID: AB_476836), followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (H&L Alexa Fluor 647, CST, catalog No. 4410, RRID: AB_1904023). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Immunofluorescent images were visualized by laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM, Eclipse Ti inverted microscope, NIKON Inc). The positive signals for COL1A1 are shown in red. DAPI staining is shown in blue.

Statistical Analysis

Data on continuous variables (including age, percentage change in β-CTX, ALP, BMD, etc) were expressed as the median and interquartile range. All basic experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times, and the results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The Wilcoxon paired test was performed for the comparison of BMD values, BMD Z scores, and bone turnover markers before and after treatment. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to analyze the correlation between changes in BMD Z score and age at the initial treatment. The t test was used to compare the expression levels of WNT1, β-catenin, and COL1A1 between the WNT1-mutant patient and control. Two-tailed P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. The software SPSS 26.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0 software were used for statistical analyses.

Results

Phenotypic Features

The clinical features of the included patients are presented in Table 1. A total of 16 patients with WNT1 mutations from unrelated families were included with 12 children and 4 adults aged 1.5 to 47.0 years. Eleven children and 1 adult were clinically diagnosed with OI, and 3 adults and 1 child were diagnosed with EOOP.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of patients with WNT1 mutations at baseline

| Patient No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sillence classification | III | III | III | III | IV | III | IV | IV | IV | III | IV | III | EOOP | EOOP | EOOP | EOOP |

| Sex | F | M | F | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | F | M | M |

| Family history | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Consanguineous family | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Age at first diagnosis, y | 1.8 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 15.0 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 24.0 | 16.0 | 1.5 | 7.3 | 32.0 | 38.0 | 47.0 |

| Age at first fracture, y | 0 | 3 d | 9 d | 2 mo | 10 mo | 16 mo | 2 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 0.5 | 3 | 6 | 27 | 47 |

| Peripheral fracture, times | 8 | 7 | 25 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0a | 0a |

| Multiple vertebral fractures | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Scoliosis | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Limb deformities | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ptosis | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Joint hypermobility | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Blue sclera | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dentinogenesis imperfecta | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Intellectual disability | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Height, Z score | −3.5 | −2.2 | −9.3 | −1.6 | 0.1 | −2.3 | −1.7 | −0.2 | −0.8 | −3.0 | −0.3 | −1.4 | −0.5 | 1.2 | −1.5 | −1.1 |

| Weight, Z score | −0.7 | −1.8 | −7.1 | −0.4 | −1.0 | −6.4 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.4 | −0.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | −0.8 | −1.4 | 1.3 |

| LS BMD Z score | −4.2 | −7.9 | −6.4 | −0.5 | −4.2 | −6.4 | −3.6 | −4.2 | −3.8 | −4.4 | −2.5 | −8.5 | −2.7 | −3.0 | −4.0 | −2.6 |

| FN BMD Z score | −5.6 | −1.9 | −7.4 | NA | −5.2 | −4.9 | −4.1 | −5.5 | −5.3 | −5.1 | −3.1 | −8.2 | −4.9 | −2.3 | −3.7 | −2.6 |

| ALP, U/L | 198 | 289 | 238 | 264 | 218 | 207 | 257 | 321 | 276 | 90 | 145 | 377 | 173 | 41 | 76 | 69 |

| β-CTX, ng/mL | 0.87 | 1.06 | NA | 1.11 | 1.05 | 0.70 | 1.06 | 1.30 | 0.50 | 0.20 | NA | 0.83 | 1.32 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.10 |

Patient 4, 5, and 16 had received antiresorptive treatment at baseline. FN BMD of the proximal femur in patient 4 was not unavailable because of the intramedullary nail.

Abbreviations: β-CTX, cross-linked C-telopeptide of type I collagen; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BMD, bone mineral density; EEOP, early-onset osteoporosis; F, female; FN, femoral neck; LS, lumbar spine 2−4, M, male; NA, not available; TH, total hip.

Patients 15 and 16 had no peripheral fragility fractures and they went to the hospital because of back pain or low BMD identified at age 27 or 47 years.

The age of initial fracture ranged from birth to 47 years. Fourteen patients had a history of low-energy fractures at peripheral sites, and 15 patients had VCFs (Supplementary Fig. S1) (21). Other phenotypes included limb deformities (n = 6), scoliosis (n = 5), limited mobility (n = 8), and short stature (n = 5). Blue sclerae, ptosis, joint hypermobility, and dentinogenesis imperfecta were observed in 6, 3, 2, and 1 OI patient, respectively. All patients had low BMD, and normal serum β-CTX and ALP concentrations at baseline.

Notably, 4 patients had rare comorbidities, including hydrocephalus (patient 5), Cushing disease caused by a pituitary adenoma (patient 7), primary thrombocytosis (patient 10), and congenital cerebral dysgenesis (patient 16). Patient 7 underwent transsphenoidal pituitary adenectomy when he was aged 11 years.

Efficacy and Safety of Bisphosphonates or Denosumab

Fifteen patients received treatment and were followed up. The median age at the treatment initiation was 10.9 years (range, 4.6-22.0 years). The median follow-up duration was 2.6 years (range, 1.0-4.6 years). After treatment with bisphosphonates or denosumab, BMD values were significantly increased by 52.4%, 46.2%, and 31.8% at LS 2 to 4, FN, and TH after treatment, respectively (all P < .01 vs baseline; Fig. 1A), with significant improvement in age-specific Z scores for LS BMD and FN BMD (all P < .01 vs baseline; Supplementary Fig. S2A) (21). For patients treated with bisphosphonates (n = 13), earlier treatment initiation was associated with a greater increase in LS-BMD Z scores in 1 year (P = .01; Supplementary Fig. S2B) (21). Two patients received denosumab at ages 1.8 and 7.3 years, and LS BMD and FN BMD increased by 189.8% and 126.6% in patient 1 after 2 doses of denosumab, and increased by 38.8% and 39.8% in patient 13 after 1 dose of denosumab.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of antiresorptive therapy in WNT1-mutant patients. A, Changes in bone mineral density (BMD) after zoledronic acid, alendronate, or denosumab treatment. FN, femoral neck; LS, lumbar spine; TH, total hip. Data are expressed as the median and interquartile range. The Wilcoxon paired test was performed to compare BMD at baseline and at final follow-up. **P less than .01 vs baseline. B, Changes in bone turnover markers after zoledronic acid and alendronate treatment. ALP, alkaline phosphatase; β-CTX, cross-linked C-telopeptide of type I collagen. Data are expressed as the median and interquartile range. The Wilcoxon paired test was performed to compare ALP and β-CTX at baseline and at final follow-up. **P less than .01 vs baseline.

Serum ALP and β-CTX levels significantly decreased by 28.0% (range, 15.9%-38.8%) and 34.5% (range, 19.4%-49.3%) after zoledronic acid or alendronate treatment (all P < .01; Fig. 1B). Serum ALP and β-CTX declined by 8.1% to 18.7% and 6.1% to 8.0%, respectively, after denosumab treatment.

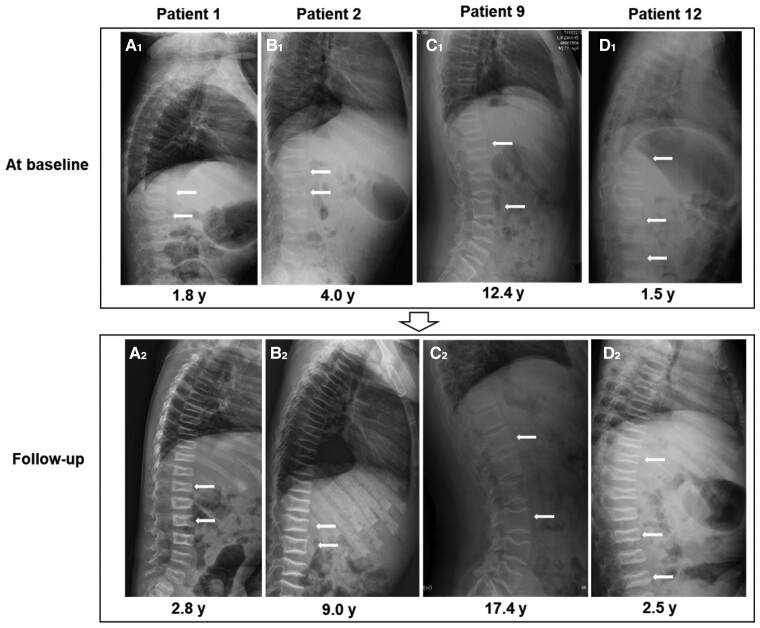

Reshaping of the vertebral bodies was observed in 4 pediatric OI patients, of whom 1 patient received 2 doses of denosumab and 3 patients received 1 to 5 infusions of zoledronic acid (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S3) (21). Four of 13 patients receiving zoledronic acid and 1 patient receiving denosumab had new fractures during follow-up.

Figure 2.

Lateral x-ray films of the thoracolumbar spine of WNT1-mutant patients with vertebral body reshaping after treatment. A1 to D1, Lateral x-ray films of the thoracolumbar spine of WNT1-mutant patients at baseline. A2 to D2, Lateral x-ray films of the thoracolumbar spine of WNT1-mutant patients after treatment. The white arrows indicate the compressed vertebra before and after treatment. Four patients had reshaping of compressed vertebral bodies after treatment. Patient 1 received denosumab treatment while the remaining 3 patients received zoledronic acid.

Overall, zoledronic acid was relatively safe and well tolerated for WNT1-mutant patients. Four patients suffered from mild acute-phase reactions after the first infusion of zoledronic acid. For denosumab treatment, 1 patient had severe hypercalcemia (serum calcium: 4.56 mmol/L) with nausea and vomiting approximately 6 months after the second injection of denosumab, which was significantly relieved within 2 days after switching to zoledronic acid infusion.

Genetic Findings

A total of 16 WNT1 variants were identified, including 9 missense mutations, 4 frameshift mutations, 2 nonsense mutations, and 1 splicing variant (Table 2). Seven variants were classified as pathogenic, 8 as likely pathogenic, and 1 (c.502G > A) as a variant of uncertain significance; this variant was predicted to be disease-causing by MutationTaster and probably damaging by PolyPhen-2. Three hot-spot mutations were identified in our patients, including c.506G > A, c.506dupG, and c.677C > T (see Table 2). We identified a novel mutation, c.255_256insG, which were classified as pathogenic according to ACMG guidelines.

Table 2.

Spectrum of WNT1 mutations in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta or early-onset osteoporosis

| Patient No. | Mutation site | Amino acid change | Effects | ACMGa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.681C > A | p.Cys227* | Nonsense | Likely pathogenic |

| c.216dupA | p.Arg73Thrfs | Frameshift | Pathogenic | |

| 2 | c.385G > A | p.Ala129Thr | Missense | Likely pathogenic |

| c.610G > T | p.Glu204* | Nonsense | Likely pathogenic | |

| 3 | c.506dupG | p.Cys170Leufs | Frameshift | Pathogenic |

| c.506dupG | p.Cys170Leufs | Frameshift | Pathogenic | |

| 4 | c.500dupG | p.Trp167fs | Frameshift | Pathogenic |

| c.500dupG | p.Trp167fs | Frameshift | Pathogenic | |

| 5 | c.501G > A | p.Trp167Cys | Missense | Likely pathogenic |

| c.104 + 1G > A | / | Splicing | Pathogenic | |

| 6 | c.385G > A | p.Ala129Thr | Missense | Likely pathogenic |

| c.506G > A | p.Gly169Asp | Missense | Pathogenic | |

| 7 | c.937C > T | p.Arg313Cys | Missense | Likely pathogenic |

| c.506G > A | p.Gly169Asp | Missense | Pathogenic | |

| 8 | c.104 + 1G > A | / | Splicing | Pathogenic |

| c.506G > A | p.Gly169Asp | Missense | Pathogenic | |

| 9 | c.110T > C | p.Ile37Thr | Missense | Likely pathogenic |

| c.505G > T | p.Gly169Cys | Missense | Likely pathogenic | |

| 10 | c.502G > A | p.Gly168Arg | Missense | VUS |

| c.677C > T | p.Ser226Leu | Missense | Pathogenic | |

| 11 | c.506dupG | p.Cys170Leufs | Frameshift | Pathogenic |

| c.506G > A | p.Gly169Asp | Missense | Pathogenic | |

| 12 | c.255_256insGb | p.Leu86Alafs | Frameshift | Pathogenic |

| c.255_256insGb | p.Leu86Alafs | Frameshift | Pathogenic | |

| 13 | c.677C > T | p.Ser226Leu | Missense | Pathogenic |

| 14 | c.382T > G | p.Phe128Val | Missense | Likely pathogenic |

| 15 | c.677C > T | p.Ser226Leu | Missense | Pathogenic |

| 16 | c.506dupG | p.Cys170Leufs | Frameshift | Pathogenic |

Abbreviations: ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Pathogenicity of the variants was assessed according to the 2015 ACMG and Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) Standards and Guidelines.

A novel mutation identified in our patient.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

Among OI patients, 7 were classified as OI type III, and 5 as OI type IV (25) (see Table 1). We found that patients who carried biallelic nonsense or frameshift mutations with premature protein truncation had an earlier onset of fractures (Tables 1 and 3). Our study also revealed that patients with biallelic WNT1 mutations displayed more severe phenotypes than patients carrying heterozygous WNT1 mutations. There were no correlations between phenotypes and mutation locations across the WNT1 gene (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of osteogenesis imperfecta patients with biallelic nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations in WNT1 from our study and previous studies

| No. | Nationality | Sex | OI type | Age at first fracture | Amino acid change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hmong | 2 F | III | In utero to 1 mo | p.Ser295* + p.Ser295* | (4) |

| 2 | Chinese | M | III | 7 mo | p.Phe180Argfs + p.Phe180Argfs | (6) |

| 3 | Chinese | F | III | 3 mo | p.Arg156Glyfs + p.Arg156Glyfs | (6) |

| 4 | Hmong | 2 M | III | At birth to 3 h | p.Ser295* + p.Ser295* | (7) |

| 5 | American | M | III | < 1.75 y | p.Cys170Leufs + p.Gln87* | (7) |

| 6 | Newfoundland | F | III | 2-3 wk | p.Gln96Profs + p.Gln96Profs | (7) |

| 7 | Indian | 4 F and 1 M | III | In utero to 6 mo | p.Cys170Leufs + p.Cys170Leufs | (8) |

| 8 | Indian | M | III | 6 mo | p.Leu86Cysfs + p.Leu86Cysfs | (8) |

| 9 | Indian | M | III | 9 d | p.Val229Hisfs + p.Val229Hisfs | (8) |

| 10 | Turkish | 2 M | III | 1 wk-10 d | p.His287Profs + p.His287Profs | (8) |

| 11 | Thai | M | III | UA (< 2 y) | p.His287Profs + p.His287Profs | (9) |

| 12 | Turkish | 1 F and 2 M | III-IV | In utero to 3 mo | p.His287Profs + p.His287Profs | (10) |

| 13 | Turkish | M | III | In utero | p.Glu189* + p.Glu189* | (10) |

| 14 | Thai | 2F | III | 4 mo-14 mo | p.Leu3Serfs + p.Leu3Serfs | (11) |

| 15 | Indian | 3 F and 3 M | III | 11 d-8 mo | p.Cys170Leufs + p.Cys170Leufs | (12) |

| 16 | Saudi | M | III | At birth | p.Cys330* + p.Cys330* | (13) |

| 17 | Chinese | F | III | At birth | p.Cys227*+p.Arg73Thrfs | This study |

| 18 | Chinese | F | III | 9 d | p.Cys170Leufs + p.Cys170Leufs | This study |

| 19 | Chinese | M | III | 2 mo | p.Trp167fs + p.Trp167fs | This study |

| 20 | Chinese | M | III | 6 mo | p.Leu86Alafs + p.Leu86Alafs | This study |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; OI, osteogenesis imperfecta; UA, unavailable.

Nearly all OI patients included in this table experienced their first fracture within age 1 year.

Effects of Mutations on the Structure of the WNT1 Protein

To investigate the structural implications of the 9 missense mutations identified in our patients, we modeled the mutant WNT1 protein based on the crystal structure of wild-type WNT1 from AlphaFold (23, 24) (Supplementary Fig. #3) (21). Three amino acid substitutions (p.Ile37Thr, p.Phe128Val, and p.Ala129Thr) were located in the α-helix, and the remaining 6 were in the highly conserved loop between the α-helix and β-strand. Four amino acid substitutions (p.Ile37Thr, p.Ala129Thr, p.Gly168Arg, and p.Gly169Asp) resulted in a missense change of a nonpolar amino acid (alanine, isoleucine, or glycine) to a polar amino acid (threonine, arginine, or asparagine), which may have impaired the stability of the protein because of the formation of additional hydrophobic interactions and a decrease in heat capacity changes on protein unfolding (26). p.Ser226Leu and p.Arg313Cys led to reduced hydrogen bonds and might have impaired the protein function that relies on hydrophobic interactions. Substitutions of highly conserved aromatic residues (p.Phe128Val and p.Trp167Cys) could reduce substrate-binding ability. p.Gly169Cys was predicted to form an intermolecular disulfide bond, which would have a detrimental effect on the correct pore folding and function of the WNT1 protein (27).

Pathogenic Mechanism of WNT1 Mutations

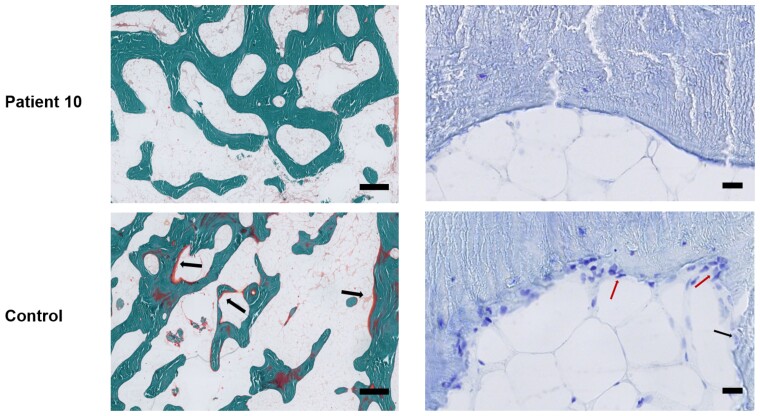

We obtained tibial debris during orthopedic surgery from patient 10, who carried c.677C > T and c.502G > A mutations in WNT1. Compared with that in the age- and sex-matched control, osteoid was decreased in undecalcified slices of the tibia from patient 10 (Fig. 3). Moreover, the number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts and their surfaces were reduced, indicating the low bone turnover status of this patient (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Representative images of the undecalcified tibia of a patient with compound c.677C > T and c.502G > A WNT1 mutations. Left (3×): Goldner trichrome staining to evaluate osteoid and mature bone, scale bar = 500 μm. Arrows refer to osteoid, indicating active progression of bone formation that was not visible in tibial bone slices from patient 10. Right (40×): Toluidine blue staining to visualize osteoblasts and osteoclasts, scale bar = 20 μm. The underlying cement line was smooth in patient 10 and scalloped in the control. Several multinucleated osteoclasts and multiple osteoblasts (indicated by arrows) were found on the bone surfaces of the control bone.

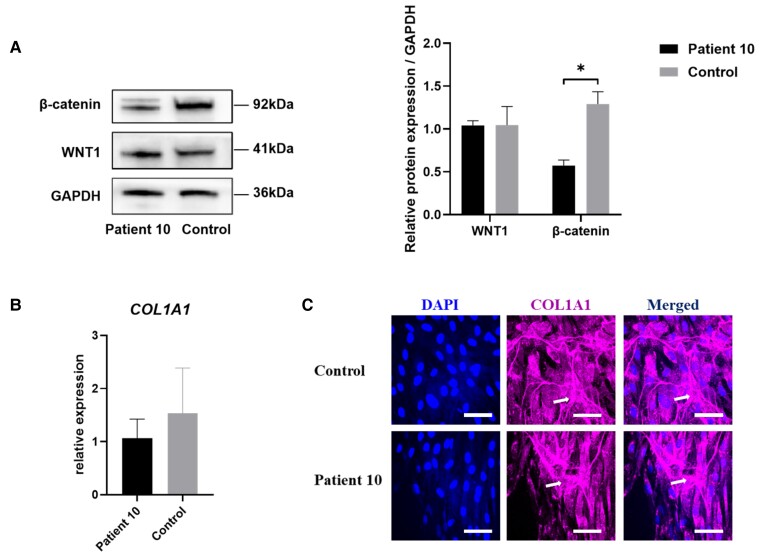

We evaluated the expression level of WNT1 in the bone sample of patient 10, which was similar to that of the control without WNT1 mutations. However, the expression level of β-catenin, a downstream protein, was significantly decreased, indicating that the WNT pathway was downregulated (Fig. 4A). COL1A1 expression was normal in fibroblasts, and its subcellular distribution was similar to that in the healthy control (Fig. 4B and 4C).

Figure 4.

Expression of β-catenin, WNT1, and collagen type I. A, Western blotting and semiquantitative analysis of β-catenin and WNT1 in bone samples from patient 10 and the control. Data were collected from 3 independent experiments. *P less than .05 vs the control. Statistical significance was assessed by a 2-tailed unpaired t test. B, Relative expression of COL1A1 in the fibroblasts from patient 10 and the control. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed to examine changes in the expression of COL1A1. The transcript level of GAPDH was used as the loading control. No difference was found in the expression of COL1A1 between the patient and the control. C, Type I collagen secretion and deposition in fibroblasts from patient 10 and the control. Expression of COL1A1 was detected by an anti-COL1A1 antibody followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647, which appears in red. DAPI was used to stain nuclei. Scale bar =50 μm. The arrow indicates the exogenous type I collagen molecules in deposited matrix.

Discussion

In this relatively large cohort of WNT1-related OI and EOOP patients, we investigated the genotype, phenotype, and pathogenic mechanism of pathogenic gene mutations for the first time. We identified 16 mutations in WNT1 and found a novel mutation in these patients. We found that the skeletal phenotypes were more severe and fragility fractures occurred earlier in patients with biallelic nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations in WNT1. Rare extraskeletal comorbidities, including brain abnormalities, hematologic diseases, and pituitary adenoma, were found in these patients. Bisphosphonate or denosumab treatment significantly increased spine and proximal hip BMD and reshaped the compressed vertebral body of patients. Interestingly, our functional study found that WNT1 and type I collagen were expressed at normal levels in the bone and skin of patient 10 with c.677C > T and c.502G > A mutations in WNT; however, reduced expression of β-catenin was found for the first time in the bone of patient 10, indicating that downregulated canonical WNT signaling might explain the abnormal bone phenotypes in WNT1-related OI and EOOP patients.

In this cohort of rare monogenic WNT1-related OI and EOOP patients, the main phenotypes included recurrent fractures, bone deformities, limited mobility, short stature, and less frequent extraskeletal manifestations, which was consistent with previous studies (4, 5, 7, 28, 29). Very rarely, hydrocephalus, Cushing disease, primary thrombocytosis, and congenital cerebral dysgenesis were identified in our patients. Previous studies suggested that WNT1 mutations could play a role in brain malformation, as deletion of WNT1 in mice led to agenesis of the midbrain and cerebellum (29), and WNT1-mutant patients had intellectual disability, seizures, or autism (4, 9, 11, 28). Additionally, WNT1 could play a role in hematopoiesis (30), and one patient with a heterozygous c.652T > G WNT1 mutation had primary myelofibrosis with mild thrombocytosis (31). Moreover, pituitary corticotroph adenomas were associated with aberrant WNT signaling (32). However, the role of WNT1 in these rare concomitant disorders is unclear and needs to be clarified. We found that zoledronic acid, alendronate, or denosumab could significantly increase the BMD of these patients, with the potential for vertebral reshaping in patients of young age, which was consistent with our previous study (33). However, denosumab treatment led to rebound hypercalcemia in one patient, which should be considered. Long-term clinical studies with large samples are needed to explore the treatment of WNT1-related OI or EOOP.

In these patients, we identified 3 hot-spot mutations in WNT1: c.506G > A, c.506dupG, and c.677C > T in WNT1. c.506dupG was a recurrent mutation reported in Chinese, Indian, and Turkish patients (8, 12, 34), and c.677C > T was reported in Chinese and German patients (6, 35, 36). We also identified a novel c.255_256insG mutation in WNT1. Interestingly, we recognized for the first time that biallelic nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations in WNT1 were associated with an earlier onset of fractures and a more severe skeletal phenotype. The dose-effect relationship between WNT1 mutations and skeletal phenotypic severity in this study was consistent with previous studies (4, 28, 37). These results enriched the genetic mutation profile and information about genotype-phenotype associations for WNT1-related OI and EOOP.

WNT/β-catenin signaling is critical for bone formation and can enhance progenitor proliferation, differentiation, and survival of osteoblasts (3). WNT1 mutations result in low bone mass and fragility fractures, which indicates that WNT1 is important for regulating bone mass. WNT1 can activate the WNT/β-catenin pathway by binding to the LRP5/6-FZD receptor complex. As a result, β-catenin, the key effector that functions as a transcriptional coactivator, accumulates in the cytosol, translocates to the nucleus, and forms a complex with the transcription factor TCF/LEF, which activates the expression of osteogenic genes in osteoblasts. In the absence of WNT1, β-catenin is immediately captured and phosphorylated by the β-catenin destruction complex, and it is subsequently rapidly degraded by the proteasome (3). Loss of β-catenin in mesenchymal precursors of osteoblasts results in reduced osteogenesis and an absence of endochondral and intramembranous bone in the embryo (38). Previous studies transfected plasmids with a single-site mutation in WNT1 into HEK293T cells and reported lower expression of TCF/LEF-responsive elements and lower levels of active β-catenin (6, 10). In this study, we verified for the first time that patient 10 with compound heterozygous WNT1 mutations had significantly decreased levels of β-catenin, which might lead to reduced expression of targeted osteogenic genes and thus decreased bone formation in OI and EOOP patients. Moreover, the tibia of patient 10 also showed low bone remodeling, with a decrease in the number and surface area of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, which was consistent with previous findings (5, 14) and may explain the delayed union after deformity-correction surgery in patient 10. The expression and secretion of COL1A1 were normal in fibroblasts, which demonstrated that WNT1 mutations might not affect the synthesis and transport of type I collagen directly. Therefore, we speculated that the main pathogenic mechanism of WNT1-related OI and EOOP could be related to impaired osteoblastic osteogenesis due to downregulation of the WNT signal pathway.

The study had several limitations. First, the treatment of WNT1-related OI or EOOP needs to be explored because the regimen and course of bisphosphonates and denosumab were inconsistent in this study. Second, genotypes and phenotypes of family members were unavailable. Third, studies of the pathogenesis of WTN1 mutation were carried out in bone and skin samples from only one patient, and the results may not represent the pathogenesis of other WNT1 mutations. Fourth, except for c.502G > A and c.677C > T, we used only in silico analysis to predict the protein stability caused by other missense mutations identified in this cohort. We did not use heterologous expression systems to evaluate the actual stability of the mutant proteins.

In conclusion, the biallelic nonsense mutations or frameshift mutations in WNT1 can lead to an earlier occurrence of fragility fractures and a more severe skeletal phenotype; this finding expanded the phenotypic and genotypic spectrum of extremely rare WNT1-related OI and EOOP. Zoledronic acid and denosumab could significantly improve BMD and reshape the compressed vertebral body in WNT1-mutant patients. The decreased osteogenic activity caused by the downregulated WNT pathway could be a potential pathogenic mechanism of WNT1-related OI and EOOP.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate our patients’ participation in this study.

Abbreviations

- 3D

3-dimensional

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- β-CTX

cross-linked C-telopeptide of type I collagen

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- BMD

bone mineral density

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EEOP

early-onset osteoporosis

- F

female

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- FN

femoral neck

- LS

lumbar spine 2−4 M male

- NA

not available

- OI

osteogenesis imperfecta

- PUMCH

Peking Union Medical College Hospital

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- TH

total hip

- VCF

vertebral compression fracture

Contributor Information

Jing Hu, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Xiaoyun Lin, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Peng Gao, Department of Orthopedics, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Science, Beijing 100730, China.

Qian Zhang, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Bingna Zhou, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Ou Wang, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Yan Jiang, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Weibo Xia, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Xiaoping Xing, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Mei Li, Department of Endocrinology, Key Laboratory of Endocrinology, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2018YFA0800801 and 2021YFC2501704), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Initiative for Innovative Medicine (CIFMS, 2021-I2M-C&T-B-007, 2021-I2M-1-051), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81873668 and 82070908), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 7202153).

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

References

- 1. Kenkre JS, Bassett J. The bone remodelling cycle. Ann Clin Biochem. 2018;55(3):308‐327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Koide M, et al. The regulation of bone metabolism and disorders by Wnt signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huybrechts Y, Mortier G, Boudin E, Van Hul W. WNT signaling and bone: lessons from skeletal dysplasias and disorders. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laine CM, Joeng KS, Campeau PM, et al. WNT1 mutations in early-onset osteoporosis and osteogenesis imperfecta. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1809‐1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mäkitie RE, Haanpää M, Valta H, et al. Skeletal characteristics of WNT1 osteoporosis in children and young adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(9):1734‐1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu Y, Ren X, Wang Y, et al. Novel WNT1 mutations in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical and functional characterization. Bone. 2018;114:144‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pyott SM, Tran TT, Leistritz DF, et al. WNT1 mutations in families affected by moderately severe and progressive recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(4):590‐597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nampoothiri S, Guillemyn B, Elcioglu N, et al. Ptosis as a unique hallmark for autosomal recessive WNT1-associated osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179(6):908‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kantaputra PN, Sirirungruangsarn Y, Visrutaratna P, et al. WNT1-associated osteogenesis imperfecta with atrophic frontal lobes and arachnoid cysts. J Hum Genet. 2019;64(4):291‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keupp K, Beleggia F, Kayserili H, et al. Mutations in WNT1 cause different forms of bone fragility. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(4):565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuptanon C, Srichomthong C, Sangsin A, et al. The most 5′ truncating homozygous mutation of WNT1 in siblings with osteogenesis imperfecta with a variable degree of brain anomalies: a case report. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mrosk J, Bhavani GS, Shah H, et al. Diagnostic strategies and genotype-phenotype correlation in a large Indian cohort of osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2018;110:368‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Faqeih E, Shaheen R, Alkuraya FS. WNT1 mutation with recessive osteogenesis imperfecta and profound neurological phenotype. J Med Genet. 2013;50(7):491‐492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Välimäki VV, Mäkitie O, Pereira R, et al. Teriparatide treatment in patients with WNT1 or PLS3 mutation-related early-onset osteoporosis: a pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(2):535‐544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li H, Ji CY, Zong XN, Zhang YQ. Height and weight standardized growth charts for Chinese children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years [article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2009;47(7):487‐492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khadilkar AV, Sanwalka NJ, Chiplonkar SA, et al. Normative data and percentile curves for dual energy X-ray absorptiometry in healthy Indian girls and boys aged 5-17 years. Bone. 2011;48(4):810‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu H, Zhao Z, Wang H, et al. Bone mineral density of the spine in 11,898 Chinese infants and young children: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guan WM, Pan W, Yu W, et al. Changes in trabecular bone score and bone mineral density in Chinese HIV-infected individuals after one year of antiretroviral therapy. J Orthop Translat. 2021;29:72‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, et al. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1137‐1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun L, Hu J, Liu J, et al. Relationship of pathogenic mutations and responses to zoledronic acid in a cohort of osteogenesis imperfecta children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(9):2571‐2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu J, Lin X, Gao P, et al. Supplementary material for “Genotypic and phenotypic spectrum and pathogenesis of WNT1 variants in a large cohort of patients with OI/osteoporosis. figshare. Dataset. Posted December 13, 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.21714653.v1 [DOI]

- 22. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. ; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596(7873):583‐589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, et al. Alphafold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D439‐D444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marini JC, Forlino A, Bächinger HP, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fu H, Grimsley G, Scholtz JM, et al. Increasing protein stability: importance of DeltaC(p) and the denatured state. Protein Sci. 2010;19(5):1044‐1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. MacDonald BT, Hien A, Zhang X, et al. Disulfide bond requirements for active Wnt ligands. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(26):18122‐18136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fahiminiya S, Majewski J, Mort J, et al. Mutations in WNT1 are a cause of osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 2013;50(5):345‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Targeted disruption of the murine int-1 proto-oncogene resulting in severe abnormalities in midbrain and cerebellar development. Nature. 1990;346(6287):847‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sturgeon CM, Ditadi A, Awong G, et al. Wnt signaling controls the specification of definitive and primitive hematopoiesis from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(6):554‐561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mäkitie RE, Niinimäki R, Kakko S, Honkanen T, Kovanen PE, Mäkitie O. Defective WNT signaling associates with bone marrow fibrosis—a cross-sectional cohort study in a family with WNT1 osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(2):479‐487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ren J, Jian F, Jiang H, et al. Decreased expression of SFRP2 promotes development of the pituitary corticotroph adenoma by upregulating Wnt signaling. Int J Oncol. 2018;52(6):1934‐1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li LJ, Zheng WB, Zhao DC, et al. Effects of zoledronic acid on vertebral shape of children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2019;127:164‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lu Y, Dai Y, Wang Y, et al. Complex heterozygous WNT1 mutation in severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta of a Chinese patient. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2018;7(1):19‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vollersen N, Zhao W, Rolvien T, et al. The WNT1G177C mutation specifically affects skeletal integrity in a mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta type XV. Bone Res. 2021;9(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li S, Cao Y, Wang H, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis in Chinese cohort with autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Front Genet. 2020;11:984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palomo T, Al-Jallad H, Moffatt P, et al. Skeletal characteristics associated with homozygous and heterozygous WNT1 mutations. Bone. 2014;67:63‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen J, Long F. β-Catenin promotes bone formation and suppresses bone resorption in postnatal growing mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(5):1160‐1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.