Abstract

Objective

To test the feasibility of a pan-European professional recognition system for public health nutrition.

Design

A multistage consultation process was used to test the feasibility of a model system for public health nutritionist certification. A review of existing national-level systems for professional quality assurance was conducted via literature review and a web-based search, followed by direct inquiries among stakeholders. This information was used to construct a consultation document circulated to key stakeholders summarising the rationale of the proposed system and inviting feedback about the feasibility of the system. Two consultation workshops were also held. The qualitative data gathered through the consultation were collated and thematically analysed.

Setting

Europe.

Subjects

Public health nutrition workforce stakeholders across twenty-nine countries in the European Union.

Results

One hundred and forty-five contacts/experts representing twenty-nine countries were contacted with responses received from a total of twenty-eight countries. The system proposed involved a certification system of professional peer review of an applicant's professional practice portfolio, utilising systems supported by information technology for document management and distribution similar to peer-review journals. Through the consultation process it was clear that there was overall agreement with the model proposed although some points of caution and concern were raised, including the need for a robust quality assurance framework that ensures transparency and is open to scrutiny.

Conclusions

The consultation process suggested that the added value of such a system goes beyond workforce development to enhancing recognition of the important role of public health nutrition as a professional discipline in the European public health workforce.

Keywords: Public health nutrition, Certification, Workforce development, Quality assurance

The need for coordinated and strategic action to prevent and address malnutrition in all its forms is recognised internationally( 1 ). This recognition is expressed in the range of government policies that have been developed across Europe( 2 ) and other regions of the world( 3 ), largely in response to the surge in nutrition-related chronic disease over the past 20 years, that articulate the aspirations and strategic priorities of national governments to address nutrition challenges. While they provide a focus for public health nutrition (PHN) action at a national level, they do not necessarily identify what capacity exists to operationalise these strategies and they rarely commit to specific investments that make strategy implementation a reality. This has been identified as a major limitation of these policy instruments( 4 ).

The health workforce, and the PHN workforce in particular, has previously been identified as a major determinant of the capacity of countries to implement national policy and action plans addressing nutrition( 5 ). The limited available data about the size, structure, composition, competence and ongoing development needs of the PHN workforce in developed countries suggest that there is considerable variability between countries in terms of workforce capacity, extent of professionalisation and workforce quality assurance( 5 – 10 ). In developing countries, where the double burden of under- and overnutrition is becoming increasingly prevalent, requiring a broader range of interventions to address a broader profile of nutrition issues, the need for strategic workforce development is even greater. This suggests that PHN workforce development is likely to be an ongoing strategic need in most, if not all countries, irrespective of the degree of economic development or varying epidemiological profiles.

PHN workforce development at a global level is constrained by a number of systematic barriers summarised in Table 1 ( 5 , 11 – 14 ). While many of these reflect a lack of political commitment or appreciation of the utility of a specialist workforce, others reflect a lack of organisation and harmonisation of the workforce. This is an important role of professional associations and a desirable outcome of the professionalisation of PHN.

Table 1.

Systematic barriers to PHN workforce development internationally

| • A lack of investment in workforce growth, despite clear recognition of the need for strategic action |

| • A lack of recognition of the utility of a specialist PHN workforce tier in many countries |

| • Under-developed professional structures specifically for PHN |

| • Poor role delineation relating to responsibility for PHN functions in the health workforce |

| • Limited and unsophisticated approaches to workforce development such as equating workforce development with training rather than understanding it as a multi-strategy system for preparedness |

| • Lack of data enumerating and profiling the PHN workforce and its continuing education needs |

| • Lack of consensus about the basic and cross-cutting competencies or curricula needed in PHN |

| • Lack of an integrated system for life-long learning |

| • Inadequate incentives for participation in training and continuing education |

| • The variability and diversity of need for PHN interventions between countries, services and workforce capacities |

| • Limited frameworks for national and international certification/credentialing |

| • Limited research to evaluate the relationship among individual competency, organisational performance and health outcomes |

| • Limited data regarding effective strategies for sustaining workforce preparedness and translating research findings into interventions |

Many of the challenges outlined in Table 1 reflect a degree of workforce and professional disorganisation that has been identified as limiting workforce capacity at national level( 5 ). Workforce regulation is a quality assurance and recognition strategy that has been widely used across the professions, including those in health and nutrition, to bring organisation and structure to workforce issues( 15 ). Regulation can take a number of forms but has traditionally taken the form of national statutory regulation (such as mandatory registration systems like the registration systems used by the dietetics profession in Canada and the USA( 7 , 10 )) that is designed primarily to ensure patient safety and the practitioner's fitness to practise. In this form, registration is a pre-condition of legal right to practise. Voluntary regulation and recognition systems (using variable nomenclature such as registration, accreditation or certification) have also been developed, usually under the auspices of professional bodies and often in response to the need to promote professional integrity and credibility (such as the voluntary system for registering public health nutritionists developed by the Nutrition Society in the UK).

It has previously been argued that explicit delineation and promotion of a designated PHN workforce, distinct from the dietetics and/or the general public health workforce, is an important enabler of workforce capacity building to address PHN issues; the assumption being that specialisation, and recognition of specialisation, is a driver for more effective practice and organised workforce and community effort( 5 , 14 ). A professional certification system, based on agreed competency standards, that defines a specialist PHN practitioner irrespective of practice setting, is suggested as a mechanism to serve this purpose.

The present paper reports on work undertaken as part of a multi-component project funded by the European Union (EU) to conduct formative research and consultation related to the development of the PHN workforce in Europe (the JobNut project). The objective of the work was to develop and test the feasibility of a Europe-wide system for professional recognition to ensure workforce quality, ongoing development and mobility.

Methods

A multistage iterative process was used to:

-

1.

describe and explore existing, accessible and relevant professional recognition systems in the European Union;

-

2.

propose a system to suit pan-European application; and

-

3.

test the feasibility of the proposed system via a process of key stakeholder consultation.

The different stages and methods used in this process are summarised as follows.

Stage 1: Review of existing systems and literature

The initial review stage involved a step-wise process of information identification, review and verification. A non-exhaustive literature review was conducted of published reports and reviews of different approaches to certification, registration, regulation and professional quality assurance in discipline areas including PHN, nutrition, public health, dietetics, other allied health professions and medicine. This was complemented by a web-based search to identify organisations, professional bodies and governmental agencies involved in the regulation and registration of different health-care professionals and professional bodies or societies across Europe. Key stakeholders (academics, practitioners) in PHN in each country/member state (sourced from an earlier study's key stakeholder contact list( 16 )) were contacted for more information and contact details regarding agencies, organisations or bodies related to the regulation of the professions of interest in each country, where they existed. Stakeholder follow-up was limited to two email contacts over a 2-month period. Once information had been gathered, a summary was prepared and reported back to individual contacts for further clarification and verification of information gathered. Following collation and clarification of the information from all the countries that had engaged with the process, a situational analysis was undertaken.

Stage 2: Model development and description

Following the first stage of reviewing the literature and existing models it became clear that a statutory regulatory model for the profession of PHN that has a primary function of consumer protection was not warranted in our disciplinary context. It was also considered not feasible in the pan-European context because of the absence of an international legal framework with relevant jurisdiction. This pointed to a professional self-regulatory model with primarily workforce and professional development functions. Informed by the review of existing systems, literature and considerations of the practicalities of a pan-European system, the authors developed an individual practitioner-based certification model for professional recognition (described in detail in Fig. 1 and Table 2).

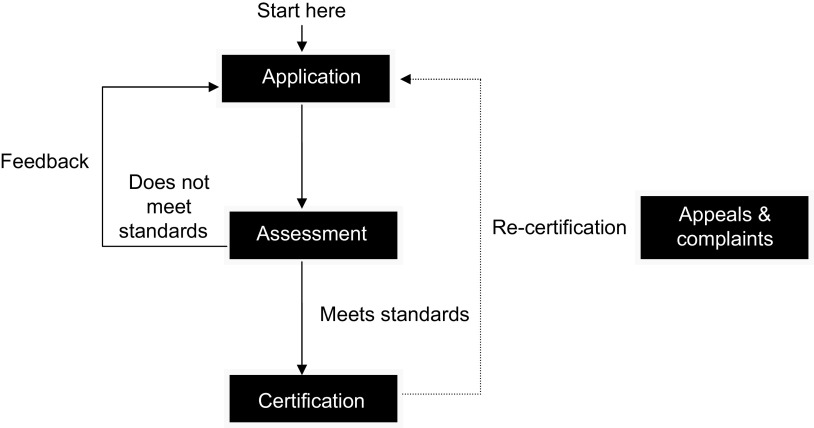

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the proposed certification system for public health nutritionists

Table 2.

Attributes of and feedback on the PHN certification model

| Step | Process and principles proposed for each step | Stakeholder feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Application | The onus is on the applicant to provide evidence to support assessment against prescribed certification standards. Application in the form of a portfolio that is submitted electronically via an IT platform (e.g. a professional association website). This platform also provides instructions and other resources to facilitate applications. It is modelled on job application processes used in many countries. Portfolio structure would be predefined and include guidance on information and evidence required that will be used to assess suitability for recognition. Applications would have a defined portfolio template structure to facilitate consistent assessment against assessment standards. This will include three main requirements: | Five main pieces or sources of ‘evidence’ were highlighted to assist assessment (i.e. evidence of education, experience, current curriculum vitae, references and personal statements/testimonials). Electronic submission was seen as the best option. The potential for plagiarism and abuse of the system was flagged as a possible limitation. There should also be some flexibility to allow applicants to submit either in hard copy or electronically. The majority saw it as important if not essential that it was possible to submit in a candidate's native language. However, many felt that English was also important, if the main aim is to enable workforce mobility. |

|

||

| Applications would be submitted in the applicant's first language. This model presupposes there is only one category of certification (yes or no). | ||

| Assessment | Assessment would involve peer review by at least two peer reviewers, similar to established journal editorial review processes. The assessment process would assess the applicant's submission and evidence portfolio against agreed standards. These standards (developed based on agreed core competencies) will be clearly articulated, precisely defined and measurable. Assessors would receive training/instruction regarding the assessment process to ensure quality of review. | There was a consensus that peer review was the most appropriate approach to use; however some challenges were identified including: |

| Assessment would include consideration of evidence of required knowledge, skills and attitudes required to effectively perform PHN functions in the workplace (=competency). In situations of variable assessment recommendations from reviewers, an independent moderator would review the application and each review, and make recommendations. |

|

|

| Certification | There are two outcomes of the assessment process, either: | Almost all respondents believed that giving feedback and guidance was an important part of any certification process. Providing information pre-application was seen as an aid to this process, although some raised concerns that it was time consuming and it might lead to appeals. |

|

||

| In both cases, the outcome is fed back to the applicant. In the former where the applicant is awarded certification, he/she is told the terms and conditions as well as the period of certification. In the latter, the applicant is given detailed feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the submission/application and advice as to what is required in order to achieve the necessary standard/competence. | ||

| Re-certification | It is recognised that an individual's competencies can lapse without ongoing professional development and practice exposure (‘use it or lose it’ principle). A regular process of external peer review and feedback is an important iterative process for professional development. After a set period of time (e.g. 5 years), certification as a public health nutritionist will expire and an individual wishing to continue to be certificated will need to go through a process of re-certification. The purpose of re-certification is to ensure ongoing competency in the range of functions/skills required of a public health nutritionist and this cannot be assured without some form of periodic verification. Therefore, the re-certification process is designed to ensure ongoing competency. The process and evidence for re-certification would be the same as for the initial certification process, and hence the same standards in terms of the range and quality of evidence that is deemed acceptable, which would be agreed by the certification body, would apply. The form of submission would also be the same as for the initial certification process. | The majority suggested 5 years as an appropriate period of time for certification to be awarded before re-certification or further review. The majority stated that re-certification was necessary to ensure credibility of the profession, continuing development and maintenance of standards of practice. There was agreement that re-certification should be a simpler process and less arduous than the initial certification. It should be based on experience gained since initial or previous certification and evidence that had previously been submitted would be ‘banked’. |

| Appeals | An applicant will have the option of appealing any decision and to rebut feedback from reviewers (e.g. provide further evidence). This rebuttal/appeal will be reviewed by a third reviewer not originally involved in the initial decision in order to ensure transparency in the process (similar to editors who manage authors’ rebuttals to reviewers’ comments in the journal editorial process). On review of an appeal/rebuttal, the registrar would refer the additional information to reviewers for reassessment/consideration. Decisions made by the registrar based on second-round appraisal would then be communicated to applicants with further feedback. | All respondents were in favour of having an appeal process to ensure fairness, transparency and clarify misunderstandings. The main potential weaknesses were time and resources needed to undertake appeals and the lack of consistency within and between countries. |

| Complaints | Complaints mechanisms are common in professional quality assurance and accountability systems used worldwide. Where practice falls below agreed/set standards then this may lead to complaints by peers, colleagues or members of the public. Anyone would be eligible to make a formal complaint which would need to be received in writing, outlining the basis and evidence relating to the complaint. | The majority agreed there was a need for a complaints procedure to assure standards are met. |

PHN, public health nutrition; IT, information technology.

The proposed system

In order to avoid the complexity and cost of establishing international legislative and regulatory structures, the system proposed was based on a voluntary, self-regulatory certification process. Certification in this context was defined( 17 ) as:

a process by which an authorised body/agency, such as a professional body or governmental agency, grants recognition to those individuals as having met certain pre-determined requirements or criteria.

The system proposed is best described as a voluntary individual practitioner certification system based on a process of peer review and feedback, similar to well-established journal review processes. Figure 1 presents a schematic of the certification system, while the process and principles for each step are detailed in Table 2.

The primary functions of this certification system were a combination of workforce development and professionalisation, including:

-

1.

setting a standard for peer review and continuing professional development guidance;

-

2.

setting benchmarks for competency attainment that explicitly inform workforce preparation and continuing education self-assessment;

-

3.

helping define the work of public health nutritionists;

-

4.

helping inform workforce recruitment (certification can be viewed as a credential/proxy measure of specialisation/advanced competence); and

-

5.

facilitating workforce mobility in Europe.

The secondary functions of this certification system addressed consumer protection, including:

-

1.

assuring the public that certified practitioners meet defined quality standards, maintain practice standards and are accountable professionally; and

-

2.

providing a mechanism for individual practitioner accountability via complaints and re-certification processes.

Stage 3: Consultation and feasibility testing

A consultation document that described the certification system was developed to inform the stakeholder consultation and feasibility testing process. This document included sixteen embedded questions (Table 3) that focused stakeholder feedback and discussion about different stages and attributes of the proposed system. The consultation document was circulated electronically to 145 individuals representing twenty-nine countries and organisations operating within Europe. These persons were encouraged to circulate the consultation document as widely as possible to relevant stakeholders (snowball sampling). Stakeholders returned feedback against embedded questions by email return.

Table 3.

Certification system stakeholder consultation questions

| 1. What types of evidence do you think should be included in a portfolio to assist peer-review assessment? |

| 2. Do you think electronic submission (similar to online journal submission) is a feasible system for application and document management? |

| 3. How important is the proposal that submissions be prepared and lodged in applicants’ native language? |

| 4. What are your opinions about the proposed peer-review process as a basis for assessment of certification? |

| 5. What do you think are the potential strengths and weaknesses of this approach to assessment (peer review)? |

| 6. What do you think about the proposal that feedback and guidance is a key component of the assessment and certification process? |

| 7. What period of time do you think certification should be awarded before re-certification or further review? |

| 8. What are the potential strengths of the certification process? |

| 9. What are the potential weaknesses of the certification process? |

| 10. Do you agree that an appeals process needs to form part of the overall certification process/model? |

| 11. Do you agree that periodic reassessment of ongoing competency is essential in a certification system? |

| 12. What are the strengths or weaknesses in this proposed system of re-certification? |

| 13. Do you think it is essential to have a complaints procedure? |

| 14. Do you think there should be a pan-European body to govern the system? |

| 15. Who and how should a representative be selected from each member state on this body? |

| 16. Do you have any other comments regarding what we have proposed? |

Consultation workshops

Two consultation workshops were facilitated in Slovenia by the authors to engage stakeholders from new EU member states where there had been limited previous contact or where engagement had been difficult using an electronic approach. Participants in these workshops involved academics and practitioners from Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Norway, Poland, Serbia/Central and Eastern European Network and Slovenia. The workshop events involved a facilitated discussion of each aspect of the model drawing on the sixteen questions asked in the consultation paper. This was done in order to ensure the methodology and information collected was comparable to that carried out/gathered through the email consultation process. Two authors (R.H. and B.M.) recorded key discussion notes from the workshop discussion against questions posed in Table 3.

Qualitative analysis of feedback

The qualitative data gathered through the workshops and email consultation were thematically analysed by two authors (J.D. and R.H.) independently before scrutinising response themes collectively as a research team. This process was designed to maximise the trustworthiness of analysis and response interpretation.

Results

Existing professional recognition systems

Country-specific information was gathered from twenty-eight countries, including feedback and information from academics, employers, policy makers, professional bodies/associations and practising public health nutritionists. The variability of accessibility and quantity of information available between countries was noteworthy and made detailed descriptions and comparisons of existing systems difficult. Across Europe (up to August 2008), there appeared to be only one formal registration system explicitly for PHN in existence (i.e. the voluntary register of the Nutrition Society, UK). There were, however, other registration-type systems in place for nutritionists, nutrition scientists, dietetics, medicine and other allied health professionals, run on a voluntary or mandatory basis in at least twenty EU countries. Mandatory registration was the most common form in these related professions, with many EU member countries (more than twenty) having no identifiable professional recognition system specifically for PHN.

Consultation feedback

A total of thirty-four completed consultation documents were received from key stakeholders across the EU, with more than one person contributing to the response from some countries. Approximately one-third (n 14) of the responses received were from non-academics and the rest (n 20) were from academics. An additional twenty-one stakeholders participated in the consultation workshops, representing a total of thirteen countries. Those who took part in the consultation had a wealth of experience in PHN practice averaging 18 years (range 1 to >40 years). Table 2 summarises the key attributes of the certification system at each stage and the key response themes from consultations about the system. All respondents, bar one, agreed that there was a need for a pan-European body to govern the certification system. There was less agreement over who and how a representative should be selected from each member state on to a pan-European body. There was agreement that there needed to be individuals from a range of backgrounds.

Discussion

A common feature of models that already exist in EU member states involves an individual gaining a specific qualification from an accredited course, at either bachelor or postgraduate level, as a basis for recognition. Hence, the quality assessment centres on the educational institution rather than the specific competency of the graduate to practise. This is arguably limited as a system for practitioner quality assurance in that it assumes that all those gaining such a qualification have achieved a common minimum level of competency required to effectively practise as a public health nutritionist. Given the important role of experiential learning in PHN competency development( 18 ) and the limited work-integrated learning (placement) requirements of many nutrition training programmes observed in the EU( 9 ), reliance on a qualification alone is probably inadequate. The fundamental principle of the certification system model developed is that it involves a one-step peer assessment using well-established and well-used information technology platforms for peer review, focused on demonstrable evidence of competency and performance in practice contexts. It removes the need to accredit higher education institutions and reduces the burden of resources required for assessment.

We recognise that in some countries in the broader international context (e.g. Canada, USA) public health nutritionists are required by law to be registered with national or state registration bodies, and that in other countries systems of professional self-regulation exist at a national level (e.g. UK, Australia). The proposed system is not intended to either replace or diminish the value of these systems. Instead, the system is intended to internationalise professional recognition and workforce quality improvement so as to complement existing systems or create a system in countries where there is none. The absence of any system for professional recognition in most of the countries reviewed in the EU and the variable levels of development of PHN as a professional workforce group in EU countries( 9 ) support the development of a international system to fill these gaps and assist international exchange and workforce mobility. This reflects a majority view among PHN academics and employers involved in an earlier consensus study from this project, namely that developing a system that ensures quality of practice and maintains professional standards is a high priority( 19 ).

The present key stakeholder consultation in Europe demonstrated that there is a broad level of qualified support for a pan-European (international) system for professional recognition to support the development of the PHN workforce and profession in Europe. The feasibility of the system was dependent on a range of logistical parameters, including:

-

1.

the establishment of international consensus standards for certification (competency standards);

-

2.

the establishment of an international certification agency with the appropriate credibility, capability and capacity to govern the system;

-

3.

the establishment of a pool of peer reviewers with suitable training in certification review, appeals and complaints processes to ensure a robust and objective system;

-

4.

the development or adoption of an appropriate information technology system to enable document management and distribution; and

-

5.

resources to ensure the sustainability and credibility of the system.

Conclusions

There is considerable stakeholder enthusiasm for a voluntary pan-European professional certification model to assist PHN workforce development across Europe. This enthusiasm is however tempered with considerations of the resources and processes required to ensure the system has integrity and credibility, without which a certification system has limited utility to individual practitioners or the progression of the profession as a whole. Nevertheless, it was well recognised that the added value to such a system is not limited only to workforce development and quality assurance, but also in raising the professional profile of PHN on the international stage.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: This work was supported by funding from the European Commission Leonardo DaVinci Community Vocational Training Programme (agreement number 2003320). Conflicts of interest: None to declare. Authorship responsibilities: J.D. had the principal role in data collection, analysis and drafting of the study. R.H. and B.M. contributed to study conceptualisation and methods design, and assisted with data collection and analysis. All authors contributed to the drafting and final editing of the manuscript. Acknowledgments: The study is a component of a broader project (the JobNut project) conducted by a consortium of partners across Europe. The collaborative contributions and support of the JobNut project team, including Agneta Yngve, Inga Thosrdottir, Nick Kennedy, Carmen Perez-Rodrigo, Susannah Kugelberg, Christel Lynch, Svandis Jonsdottir and Christina Black, is appreciated. The authors also acknowledge the sharing of expertise, experience and insights of the many stakeholders across the EU who engaged throughout the consultation process.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2003) Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lachat C, Van Camp J, De Henauw S et al. (2005) A concise overview of national nutrition action plans in the European Union Member States. Public Health Nutr 8, 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. SIGNAL (2001) Eat Well Australia: An Agenda for Action for Action for Public Health Nutrition 2000–2010. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thulin S, Hughes R, Bjarnholt C et al. (2007) Workforce development: the neglected strategy in national nutrition action plans in the European Union. Ann Nutr Metab 51, 320. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hughes R (2006) A socioecological analysis of the determinants of national public health nutrition work force capacity: Australia as a case study. Fam Community Health 29, 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dodds J & Polhamus B (1999) Self-perceived competence in advanced public health nutritionists in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 99, 808–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fox A, Chenhall C, Traynor M et al. (2008) Public health nutrition practice in Canada: a situational assessment. Public Health Nutr 11, 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steyn NP & Mbhenyane XG (2008) Workforce development in South Africa with a focus on public health nutrition. Public Health Nutr 11, 792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Margetts B (2009) Promoting the Public Health Nutrition Workforce in Europe. Final Report of the Jobnut Project. Southampton: University of Southampton. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haughton B & George A (2008) The public health nutrition workforce and its future challenges: the US experience. Public Health Nutr 11, 782–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lichtveld M, Cioffi J, Baker E et al. (2001) Partnership for front-line success: a call for a national action agenda on workforce development. J Public Health Manage Pract 7, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substrances and Disease Registry (2001) CDC/ATSDR Strategic Plan for Public Health Workforce Development. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutchins C (2002) Health Promotion Workforce Development: A Snapshot of Practice in Australia: Draft Report. Melbourne: Australian Health Promotion Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hughes R (2008) Workforce development: challenges for practice, professionalization and progress. Public Health Nutr 11, 765–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hager M & Otto M (2006) An introduction to government regulations and the profession of dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1156–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jonsdottir S, Hughes R, Thorsdottir I et al. (2011) Consensus on the competencies required for public health nutrition workforce development in Europe – the JobNut project. Public Health Nutr 14, 1439–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rooney A & van Ostenberg P (1999) Quality Assurance Methodology Refinement Series. Licensure, Accreditation & Certification: Approaches to Health Services Quality. Bethesda, MD: Center for Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes R (2003) Public health nutrition workforce composition, core functions, competencies and capacity: perspectives of advanced-level practitioners in Australia. Public Health Nutr 6, 607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jonsdottir S (2008) Measurement and Development of European Consensus on Core Competencies and Curricula Required for Effective Public Health Nutrition Practice. Rykjavik: Department of Food Science, University of Iceland. [Google Scholar]