Abstract

Objective

The present study examined whether maternal diet and early infant feeding experiences relating to being breast-fed and complementary feeding influence the range of healthy foods consumed in later childhood.

Design

Data from four European birth cohorts were studied. Healthy Plate Variety Score (HPVS) was calculated using FFQ. HPVS assesses the variety of healthy foods consumed within and across the five main food groups. The weighted numbers of servings consumed of each food group were summed; the maximum score was 5. Associations between infant feeding experiences, maternal diet and the HPVS were tested using generalized linear models and adjusted for appropriate confounders.

Setting

The British Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), the French Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de L’Enfant study (EDEN), the Portuguese Generation XXI Birth Cohort and the Greek EuroPrevall cohort.

Subjects

Pre-school children and their mothers.

Results

The mean HPVS for each of the cohorts ranged from 2·3 to 3·8, indicating that the majority of children were not eating a full variety of healthy foods. Never being breast-fed or being breast-fed for a short duration was associated with lower HPVS at 2, 3 and 4 years of age in all cohorts. There was no consistent association between the timing of complementary feeding and HPVS. Mother’s HPVS was strongly positively associated with child’s HPVS but did not greatly attenuate the relationship with breast-feeding duration.

Conclusions

Results suggest that being breast-fed for a short duration is associated with pre-school children eating a lower variety of healthy foods.

Keywords: Diet variety, Variety score, Breast-feeding, Complementary feeding, Cohort studies, Pre-school child, ALSPAC, EDEN, Generation XXI, EuroPrevall

Diets with a greater variety of foods are more likely to meet nutrient recommendations than those with a limited range( 1 ). Children need a varied diet, within and across the main food groups, for optimum growth and development, yet the quality of children’s diets in developed countries is a health concern as studies report that children are eating too few portions of vegetables and too many energy-dense micronutrient-poor foods( 2 – 6 ). Cox et al. investigated food variety and found that only 7 % of children aged 24–36 months achieved the recommended range of foods( 7 ). Munoz et al. compared food intakes in children with recommendations for each of the main food groups; the mean number of servings was below recommendations for all groups except dairy and just 1 % of children met the full recommendations( 8 ). Food preferences take shape in early life and may track through to adulthood( 9 – 11 ). Furthermore, educational programmes have reported that it is hard to change eating habits in older children and adults( 12 – 14 ), so it is important to understand which factors influence the formation of eating habits in early life.

Previous research has indicated that some early feeding practices may be associated with increased food variety in later childhood( 15 ). Sullivan and Birch examined the effects of milk feeding regimen on acceptance of vegetables by infants aged 4–6 months. Infants were exposed to a vegetable for 10 d; after this period all infants had increased their intake of the vegetable, however breast-fed infants consumed more than formula-fed infants( 16 ). It is proposed that the different flavours in breast milk enhance the child’s readiness to try new foods during complementary feeding and this may shape their food choices in later life( 17 , 18 ). Other studies have identified a sensitive window in flavour learning( 17 ) suggesting that age of exposure to a variety of tastes could be important to later food variety. There is some evidence that infants weaned at 4–6 months have greater intakes of fruit and vegetables in later childhood than those weaned later( 19 ) and that eating a greater variety in the first 2 years of life is positively associated with fruit variety at 6, 7 and 8 years of age( 9 ). Additionally children’s food preferences and intakes have been shown to be strongly associated with maternal intake( 20 ). Mothers’ own food preferences and beliefs about food guide what is available in the home; consequently a child’s food choice is mostly limited to food provided by parents( 21 , 22 ). Using the extensive data collected in four European birth cohorts, the present paper examines the strength of association between a range of early-life factors and dietary variety at ages 2–4 years. Previous work in these cohorts found a positive association between duration of being breast-fed in infancy and fruit and vegetable intake in childhood( 23 ). The present study extends those analyses to cover childhood intake of other healthy foods.

Methods

Participants

The participants for the present study are from four existing European birth cohorts working collaboratively in the HabEat project (www.HabEat.eu.).

-

1.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a longitudinal birth cohort study, in which 14 541 pregnant women resident in a geographically defined area in the South West of England with an expected delivery date between April 1991 and December 1992 were recruited( 24 ). Questionnaires completed during pregnancy provided data on sociodemographic factors, maternal diet (evaluated by an FFQ) and tobacco use. Birth data were collected from medical records, including method of delivery and infant’s birth weight. Follow-up questionnaires were completed when the children were 6 and 15 months old. Information on breast-feeding and complementary feeding practices was collected. The final data set with all confounders covered 8308, 7878 and 7937 children at 2, 3 and 4 years of age, respectively. The study website contains details of all the data that are available through a fully searchable data dictionary (http://www.bris.ac.uk/ALSPAC/researchers/data-access/data-dictionary/).

-

2.

The Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de L’Enfant study (EDEN) mother–child cohort is a longitudinal study in which 2002 pregnant women were recruited between February 2003 and January 2006 in two French university hospitals (Nancy and Poitiers). A questionnaire completed during pregnancy provided data on sociodemographic factors, maternal diet (FFQ) and tobacco use. Birth data were collected from medical records including method of delivery and infant’s birth weight. Follow-up questionnaires were completed when the children were 4, 8 and 12 months old. Information on breast-feeding and complementary feeding practices was collected. The final data set with all confounders covered 1341 and 1231 children at 2 and 3 years of age, respectively.

-

3.

The Generation XXI Birth Cohort is a prospective population-based birth cohort in which 8647 children and 8495 mothers were recruited in a defined geographic area in the north of Portugal between April 2005 and August 2006( 25 ). Data on demographic and social conditions, lifestyles, medical history and prenatal care were collected by trained interviewers during the first 24 to 72 h after delivery. Baseline and follow-up evaluations were performed using face-to-face interviews and completed when the children were aged 6 months and 4 years. Intermediate follow-ups at 15 and 24 months were conducted in sub-samples (n 1040). Information was collected on breast-feeding and complementary feeding. The final data set with information for all confounders comprised 4293 children (for breast-feeding associations) and 596 children (for complementary feeding associations).

-

4.

The Greek EuroPrevall cohort study is a longitudinal study in which 1084 newborns were recruited between October 2005 and October 2007 in two different clinics in Athens. Standardized questionnaires were used to collect baseline data from each mother regarding her pregnancy, child’s birth and quality of life. Sociodemographic data, such as parental education level, parental age, occupational status and family income, were collected at birth. Follow-ups, using similar questionnaires, were conducted by telephone when the children were 12, 24 and 30 months old. During these interviews data on breast-feeding and complementary feeding practices were collected. The final data set with all confounders covered 245 children.

FFQ in children

Dietary information was collected via parental-completion FFQ for each of the cohorts at various time points ranging from 2 to 4 years of age. Each cohort used its own FFQ, which varied in the number of items and frequency categories investigated. The ALSPAC children’s FFQ was a modified version of the mother’s FFQ that was based on an FFQ developed by Yarnell et al. The FFQ administered when the children were 38 months old has been compared with 3 d diet diaries collected in a sub-sample of children at 41 months; the results were very similar. The Generation XXI FFQ has thirty-five items. In a sub-sample of approximately 2500 children, 3 d food records were also completed and compared with the FFQ data. Pearson’s coefficients showed weak to moderate positive correlations for most food groups. The EDEN FFQ for children was a modified shortened version of the mothers’ validated FFQ. The EuroPrevall FFQ was based on the FFQ that was designed to record food intake among pre-school children in Greece and other European countries as part of the ToyBox project of the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Programme.

Table 1 provides further descriptive data for each of the FFQ. The FFQ data were harmonized by grouping questions about similar foods together in the same way in each cohort (see below).

Table 1.

Description of the FFQ used in pre-school children in each of the four European cohorts

| Cohort | Age | No. food items/groups | Starchy foods | Fruits | Vegetables | Dairy | Meat, fish & alternatives | No. of response options | Min. daily servings | Max. daily servings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALSPAC | 2 years | 31 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 11 | Parents reported daily servings of foods | ||

| 3 years | 33 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 14 | 5 | Never | >1 | |

| 4 years | 42 | 10 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 18 | 5 | Never | >1 | |

| EDEN | 2 years | 19 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 7 | Never | >1 |

| 3 years | 20 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 7 | Never | >1 | |

| EuroPrevall | 3 years | 61 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 17 | 7 | Never | >1 |

| Generation XXI | 4 years | 35 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | Never | >1 |

ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de l’Enfant.

Healthy Plate Variety Score

The Healthy Plate Variety Score (HPVS) is a modified version of the Food Variety Index for Toddlers (VIT), which was developed by Cox et al.( 7 ). The HPVS developed in the present study used FFQ data and was based on the five food groups and number of servings recommended in the food plate model (formerly the pyramid model) healthy eating guidelines promoted by the US Department of Agriculture( 26 ).

To calculate the HPVS we first assigned a value to each of the frequency response options in the FFQ to obtain the daily number of servings of each food item. Food items were then allocated to one of five food groups: starchy foods (including potatoes); fruits; vegetables; meat, fish and alternatives (MFA); and dairy foods.

As intended by Cox et al.( 7 ), the purpose of a variety score is to measure variety both within and between food groups. Therefore in the next steps truncations were applied to ensure variety. Within each food group (except fruit and vegetables) the contribution of a particular food item was truncated at 33 %. Foods within a food group that were similar (e.g. pasta and noodles) were grouped together and counted as a single food so that they did not contribute more than 33 % of the total. Due to a limited number of questions in some of the FFQ about types of fruits and vegetables, it was not possible to assess variety within these two groups. The score instead reflects whether children ate the recommended number of servings. After the groupings and truncations were applied, the number of servings for each food group was totalled. Food group scores were calculated by dividing the total number of servings by the recommended number of servings per day for each food group. The recommended daily numbers of servings used were: starchy foods=7, fruit=2, vegetables=3, MFA=2 and dairy foods=3. To ensure variety between the food groups, each food group score was truncated at 1·00 (e.g. if a child ate eight different types of starchy foods daily, when this was divided by 7 it gave a potential score of 1·14 which was then truncated to 1·00). This meant that a high intake of one food group could not compensate mathematically for a low intake in another food group. The final HPVS was the sum of the five food group scores, with a potential total of 5·00.

Excluded foods

The HPVS assesses the variety of intake of nutritious foods, not total food consumption. So in line with healthy eating principles, condiments, sweets/candy, herbs/spices, soft drinks, oil, butter/margarine and salty snack foods were excluded in a similar way to the VIT( 7 ). In addition, cakes, biscuits/cookies, puddings and fried potatoes were excluded from the HPVS.

Maternal FFQ

Maternal diet was assessed by FFQ in two of the cohorts. In the EDEN cohort maternal diet was assessed in late pregnancy; in the ALSPAC cohort it was assessed in late pregnancy and when the child was 4 years old. These FFQ data were used to calculate the maternal HPVS in the same way as described above. Maternal diet data were available in the Generation XXI cohort, but there were insufficient food items to calculate the HPVS.

Statistical analyses

Parallel analyses were carried out in each cohort separately. Descriptive data were calculated for individual food group scores and total HPVS at the various ages for each cohort. Adjusted associations between early feeding experiences (duration of being breast-fed, age at introduction of complementary feeding, age at introduction of fruit and vegetables) and the HPVS (treated as a continuous variable) were tested using generalized linear models analysis (β coefficients, 95 % confidence intervals). Breast-feeding was both exclusive and mixed (designated as any breast-feeding) and its duration was assessed as a categorical variable: never, <1 month, 1–3 months, 3–6 months and ≥6 months. Common categories for age of introduction to fruit and vegetables were used when possible across the four cohorts. Note that in the EuroPrevall and Generation XXI cohorts the age of first introduction to fruit and vegetables was later than in the other cohorts, and in the ALSPAC cohort the children who were not introduced to fruit and vegetables until after 15 months were in a separate category. The confounders (all categorical variables) adjusted for in each cohort were sex of the child, maternal age, maternal education status (country-specific categorization in three levels) and maternal smoking. These confounding variables were only included if associated with HPVS in at least two of the cohorts. Maternal HPVS (in two cohorts only) was ranked into tertiles; the two lower tertiles were combined and compared with the highest tertile. Participants with missing values were excluded from the analyses; in cohorts with twins, one was selected at random to be included in the analyses. Analyses in the ALSPAC and EuroPrevall cohorts were performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 21. Analyses in the EDEN cohort were performed using the SAS statistical software package version 9·2. Analyses in the Generation XXI cohort were performed using the STATA/SE statistical software package version 10·0.

Results

Child HPVS and food group scores

The characteristics of the study samples are described in Table 2. Mothers of the ALSPAC and EDEN children had very similar demographic characteristics, with comparable proportions in each of the age, education and smoking categories. The EuroPrevall and Generation XXI cohorts both had a high proportion of mothers in the lowest education group. The EuroPrevall cohort had the highest proportion of older mothers. Breast-feeding rates and duration were higher in Generation XXI mothers than in the other cohorts, thus the relationship between breast-feeding rates and maternal education differed between the cohorts.

Table 2.

Characteristics of mothers and children in four European cohorts: ALSPAC, EDEN, EuroPrevall, and Generation XXI

| ALSPAC at age 2 years (n 8884) | EDEN at age 2 years (n 1341) | EuroPrevall at age 3 years (n 245) | Generation XXI at age 4 years (n 4293) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Maternal age | ||||||||

| <25 years | 1447 | 16·3 | 204 | 15·2 | 0 | 0·0 | 664 | 15·5 |

| 25–35 years | 6714 | 75·6 | 992 | 74·0 | 99 | 40·2 | 3065 | 71·4 |

| >35 years | 723 | 8·1 | 145 | 10·8 | 147 | 59·8 | 564 | 13·1 |

| Maternal education | ||||||||

| Low | 2123 | 23·9 | 321 | 23·9 | 117 | 47·8 | 1784 | 41·6 |

| Medium | 3186 | 35·9 | 237 | 17·7 | 48 | 19·6 | 1218 | 28·4 |

| High | 3575 | 40·2 | 783 | 58·4 | 80 | 32·7 | 1291 | 30·1 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | 6721 | 75·7 | 1018 | 75·9 | 163 | 66·5 | 3282 | 76·4 |

| Ever smoker | 1692 | 19·0 | 323 | 24·1 | 82 | 33·5 | 1011 | 23·6 |

| Missing | 201 | 5·3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Duration of being breast-fed | ||||||||

| Never | 2114 | 23·8 | 353 | 26·3 | 18 | 7·5 | 359 | 8·4 |

| <1 month | 911 | 10·3 | 85 | 6·3 | 27 | 10·8 | 302 | 7·0 |

| 1–3 months | 1103 | 12·4 | 281 | 21·0 | 23 | 9·6 | 522 | 12·2 |

| 3–6 months | 1504 | 16·9 | 340 | 25·4 | 66 | 27·1 | 775 | 18·1 |

| ≥6 months | 3252 | 36·6 | 282 | 21·0 | 110 | 45·0 | 2335 | 54·4 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Boys | 4591 | 51·7 | 695 | 51·8 | 141 | 57·1 | 2213 | 51·6 |

| Girls | 4293 | 48·3 | 646 | 48·2 | 106 | 42·9 | 2080 | 48·4 |

ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de l’Enfant.

The mean HPVS and food group scores for each of the cohorts at the various ages are reported in Table 3, along with the mean daily number of servings for each food group. The scores for each of the cohorts ranged from 2·3 to 3·8 (from a possible maximum of 5) and revealed that the children’s diets lacked the full healthy food variety as advised by the plate model. The lowest HPVS score was reported by the ALSPAC cohort at 2 years; however, it increased with age in this cohort. In the EDEN cohort the score was very similar at each age. The Generation XXI children at 4 years reported the highest variety score. In the ALSPAC cohort at 2 and 3 years of age, 83 % of the children did not achieve a score of 1 in any of the food groups; by 4 years of age this had improved to 58 %. In the EDEN cohort at age 2 and 3 years 38·5 % and 44·7 % did not achieve this, and in the Generation XXI and EuroPrevall cohorts the proportion was 17·0 % and 49·0 % respectively. In general the individual food group mean scores were highest for MFA and dairy foods and lowest for starchy foods and vegetables.

Table 3.

Healthy Plate Variety Score (HPVS), food group (FG) scores and daily food group servings for each of the cohorts at each age studied

| Starchy foods | Fruit | Vegetables | Meat, fish & alternatives | Dairy | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPVS | FG score | Daily servings | FG score | Daily servings | FG score | Daily servings | FG score | Daily servings | FG score | Daily servings | ||||||||

| Cohort | Age | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | (max. 7) | Mean | sd | (max. 2) | Mean | sd | (max. 3) | Mean | sd | (max. 2) | Mean | sd | (max. 3) |

| ALSPAC | 2 years | 2·3 | 0·81 | 0·29 | 0·12 | 2·0 | 0·55 | 0·30 | 1·2 | 0·41 | 0·21 | 1·2 | 0·53 | 0·24 | 1·1 | 0·56 | 0·20 | 1·7 |

| EDEN | 2 years | 2·9 | 0·65 | 0·37 | 0·15 | 2·6 | 0·63 | 0·29 | 1·3 | 0·36 | 0·24 | 1·1 | 0·64 | 0·21 | 1·3 | 0·86 | 0·17 | 2·6 |

| ALSPAC | 3 years | 2·8 | 0·60 | 0·48 | 0·14 | 3·4 | 0·41 | 0·22 | 0·8 | 0·48 | 0·26 | 1·5 | 0·70 | 0·21 | 1·4 | 0·65 | 0·17 | 1·9 |

| EDEN | 3 years | 2·8 | 0·70 | 0·36 | 0·15 | 2·6 | 0·58 | 0·30 | 1·2 | 0·34 | 0·25 | 1·0 | 0·65 | 0·21 | 1·3 | 0·84 | 0·18 | 2·5 |

| EuroPrevall | 3 years | 3·4 | 0·70 | 0·31 | 0·13 | 1·8 | 0·89 | 0·24 | 2·2 | 0·68 | 0·32 | 2·6 | 0·81 | 0·24 | 1·8 | 0·63 | 0·18 | 1·8 |

| ALSPAC | 4 years | 3·1 | 0·65 | 0·55 | 0·13 | 3·9 | 0·55 | 0·29 | 1·2 | 0·54 | 0·28 | 1·7 | 0·82 | 0·19 | 1·7 | 0·62 | 0·18 | 1·9 |

| Generation XXI | 4 years | 3·8 | 0·50 | 0·54 | 0·12 | 3·8 | 0·77 | 0·30 | 1·9 | 0·83 | 0·21 | 2·8 | 0·89 | 0·13 | 1·9 | 0·77 | 0·16 | 2·3 |

ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de l’Enfant.

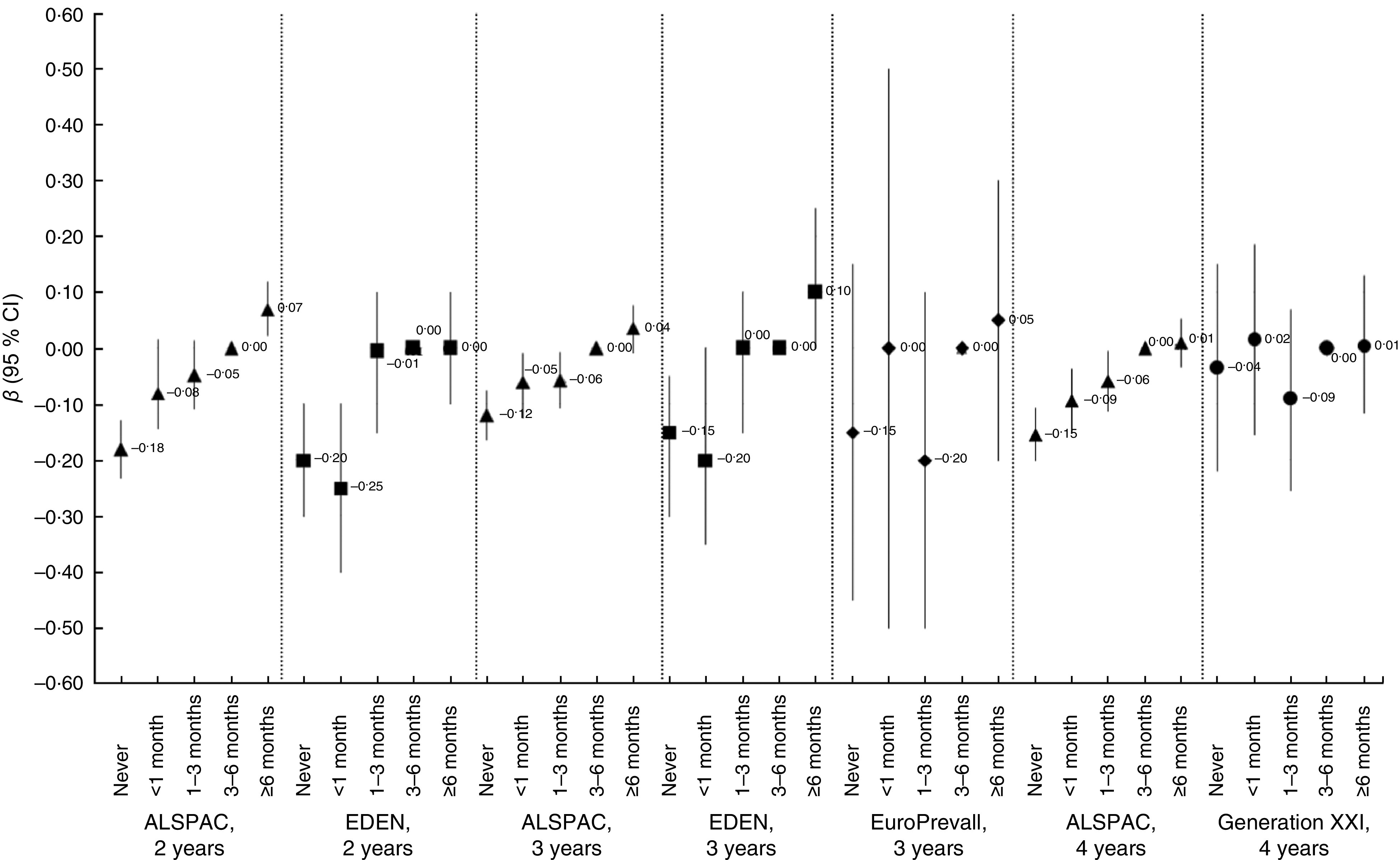

Associations between duration of being breast-fed and child HPVS

Being breast-fed for a shorter duration was associated with lower HPVS scores in the EDEN and ALSPAC cohorts in adjusted models at all ages (see Fig. 1). In the Generation XXI cohort a similar association with never being breast-fed (β=−0·09, 95 % CI −0·15, −0·02) and being breast-fed for <1 month (β=−0·10, 95 % CI −0·17, −0·04) did not persist after complementary feeding was added to the model (β=−0·35, 95 % CI −0·22, 0·15 and β=−0·02, 95 % CI −0·16, 0·19, respectively). In the EuroPrevall cohort there was a similar trend towards a lower variety score (β=−0·15, 95 % CI −0·4, 0·15) in the non-breast-fed children compared with children breast-fed for 3–6 months. In the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts, infants who never breast-fed had a lower HPVS than those who breast-fed for 3–6 months that was independent of maternal HPVS in pregnancy (β=−0·16, 95 % CI −0·21, −0·11, β=−0·098, 95 % CI −0·14, −0·06 and β=−0·14, 95 % CI −0·18, −0·09, in the ALSPAC cohort at 2 years, 3 years and 4 years, respectively; β=−0·20, 95 % CI −0·3, −0·10 and β=−0·10, 95 % CI −0·25, 0·00 in the EDEN cohort at 2 years and 3 years, respectively). There were fairly similar effect sizes in the ALSPAC cohort when maternal HPVS score at 47 months was used in place of diet in pregnancy (β=−0·14, 95 % CI −0·2, −0·09, β=−0·08, 95 % CI −0·12, −0·03 and β=−0·11, 95 % CI −0·16, −0·06 at 2 years, 3 years and 4 years, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Duration of being breast-fed and associated differences from the mean (β coefficients with 95 % confidence interval represented by vertical bars) for the Health Plate Variety Score (HPVS) in children in four European countries. Generalized linear models were adjusted for child gender, maternal age, education status and smoking status, age of introduction to solids, age of introduction to fruit and age of introduction to vegetables. Being breast-fed for 3–6 months was used as the reference category (ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de l’Enfant)

Associations between timing of complementary feeding and child HPVS

Across all cohorts there were no independent associations between the age the infant started complementary feeding and the HPVS in fully adjusted models (data not shown). In the ALSPAC cohort only, later introduction to vegetables (≥6 months) was associated with a lower variety score compared with introduction to vegetables between 4 and 5 months. Those introduced later had a lower HPVS (see Table 4). On additional adjustment for maternal HPVS the associations remained although slightly attenuated. There was some evidence that later introduction to fruit was related to lower variety score in the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts at 2 years (see Table 4), but these associations were not observed at any other age nor in the other two cohorts.

Table 4.

Age of introduction to fruit and vegetables and associated differences from the mean (β and 95 % CI) for the Health Plate Variety Score (HPVS) in children in four European countries. Generalized linear models were adjusted for child gender, maternal age, education status and smoking status, duration of being breast-fed and age of introduction to solids)

| Age of introduction to fruit | Age of introduction to vegetables | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >4 months | ≥4–<5 months (Ref.) <5 months | ≥5–<6 months | ≥6 months ≥6–7 months (EuroPrevall only) | >15 months (ALSPAC only) >7 months (EuroPrevall only) | >4 months | ≥4–<5 months (Ref.)<5 months | ≥5–<6 months | ≥6 months ≥6–<7 months (EuroPrevall only) | ≥7–<8 months (EuroPrevall only) | >15 months (ALSPAC only) ≥8 months (EuroPrevall only) | ||||||||||

| Cohort | β | 95 % CI | (Gen XXI only) | β | 95 % CI | β | 95 % CI | β | 95 % CI | β | 95 % CI | (Gen XXI only) | β | 95 % CI | β | 95 % CI | β | 95 % CI | β | 95 % CI |

| ALSPAC, 2 years | −0·06 | −0·12, 0·01 | Ref. | 0·02 | −0·05, 0·09 | −0·01 | −0·07, 0·04 | −0·32 | −0·46, −0·17 | 0·02 | −0·05, 0·10 | Ref. | 0·006 | −0·06, 0·07 | −0·12 | −0·18, −0·06 | −0·46 | −0·61, −0·31 | ||

| EDEN, 2 years | −0·15 | −0·30, 0·00 | Ref. | −0·05 | −0·20, 0·10 | −0·15 | −0·30, 0·00 | 0·05 | −0·10, 0·25 | Ref. | 0·10 | −0·05, 0·25 | 0·10 | −0·05, 0·25 | ||||||

| ALSPAC, 3 years | −0·07 | −0·12, −0·01 | Ref. | 0·03 | −0·03, 0·09 | 0·01 | −0·04, 0·06 | −0·062 | −0·18, 0·06 | 0·05 | −0·01, 0·10 | Ref. | −0·04 | −0·01, 0·09 | −0·09 | −0·13, −0·04 | −0·12 | −0·25, 0·008 | ||

| EDEN, 3 years | −0·15 | −0·30, 0·05 | Ref. | 0·15 | −0·05, 0·30 | 0·00 | −0·15, 0·15 | 0·05 | −0·10, 0·25 | Ref. | 0·10 | −0·05, 0·25 | 0·10 | −0·05, 0·25 | ||||||

| EuroPrevall, 3 years | N/A | Ref. | −0·30 | −0·65, 0·00 | −0·15 | −0·48, 0·25 | −0·30 | −0·95, 0·35 | N/A | Ref. | −0·15 | −0·75, 0·40 | −0·15 | −0·80, 0·50 | −0·35 | −1·05, 0·30 | ||||

| ALSPAC, 4 years | −0·17 | −0·08, 0·04 | Ref. | 0·02 | −0·04, 0·08 | 0·02 | −0·03, 0·07 | −0·08 | −0·21, 0·05 | 0·001 | −0·06, 0·06 | Ref. | −0·05 | −0·11, 0·01 | −0·09 | −0·14, −0·04 | −0·11 | −0·24, 0·03 | ||

| Generation XXI, 4 years | N/A | Ref. | 0·005 | −0·135, 0·145 | −0·08 | −0·20, 0·04 | Ref. | −0·03 | −0·16, 0·10 | 0·05 | −0·07, 0·17 | |||||||||

Ref., referent category; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de l’Enfant; N/A, not applicable.

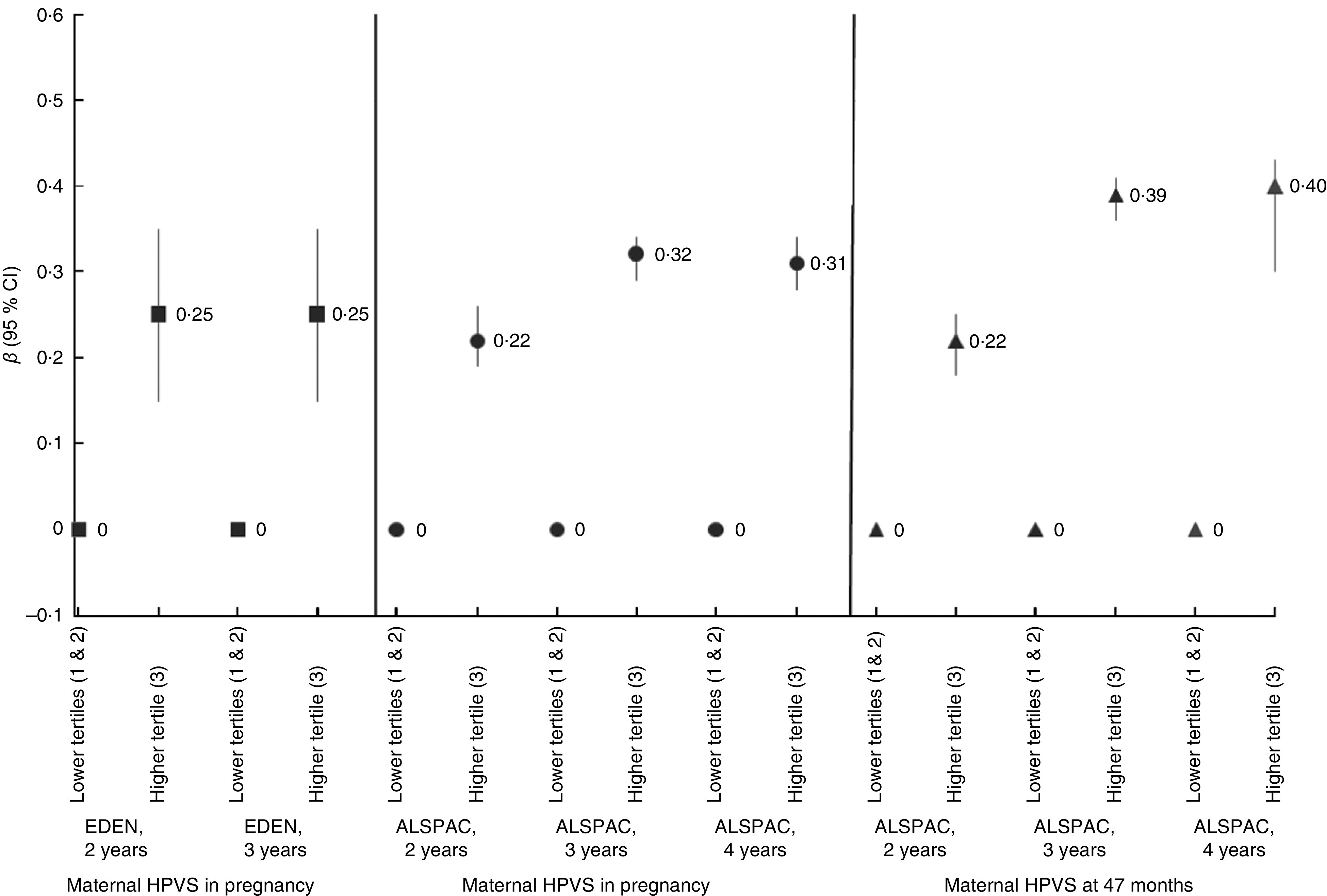

Direct associations between maternal HPVS and child HPVS

The maternal HPVS scores measured during pregnancy in the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts were positively associated with higher child HPVS at all ages. In the ALSPAC cohort, there was no difference in the strength of the association between the child’s HPVS and that of the mother in pregnancy when the child was 2 years old or 4 years old; however, at ages 3 and 4 years the association with the latter maternal HPVS was stronger (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Maternal Health Plate Variety Score (HPVS) in pregnancy and at 47 months, and associated differences from the mean (β coefficients with 95 % confidence interval represented by vertical bars) for the HPVS in children in two European countries. Generalized linear models were adjusted for child gender, maternal age, education status and smoking status, duration of being breast-fed, age of introduction to solids, age of introduction to fruit and age of introduction to vegetables. Being in the lower tertiles (1 and 2) of maternal HPVS was used as the reference category (ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pre et postnatals de la santé et du développement de l’Enfant)

Discussion

We studied diet variety in pre-school children in four European cohorts. Almost none of the children in these cohorts reached the recommended score of 5 for variety of healthy foods eaten, as measured by the HPVS. The Generation XXI children had a slightly higher average variety score than those in the other countries. We found that never being breast-fed or being breast-fed for a shorter time was directly associated with a lower variety of healthy foods consumed at 2 and 4 years of age in the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts, independent of confounding variables including the age when foods were introduced and maternal education. A trend in the same direction was observed in the Generation XXI and EuroPrevall cohorts. In the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts these independent associations of dietary variety with the duration of being breast-fed remained after accounting for maternal HPVS and were consistent over the three ages assessed in the ALSPAC cohort. Maternal diet variety itself was strongly related to child diet variety.

Traditionally, dietary assessment studies have concentrated on energy intakes and the nutrient composition of the diet rather than on the variety of foods in the diet. This is surprising as healthful diets are considered to be those that are most varied( 1 ). Food variety can be measured in different ways; the present study looked at the intake of healthy foods from the five groups represented in the plate model guide to healthy eating and at the variety of foods consumed within these food groups. This assessment of variety was a modified version of a previous variety score (VIT)( 7 ); however, here FFQ data rather than diet diary data were used. More of the unhealthy energy-dense foods were excluded than in the original VIT( 7 ) to ensure that variety only within healthy foods was assessed. Thus the children’s HPVS observed in the present study (2·3 to 3·8) was lower than VIT scores observed in other studies. In the Cox et al. study the mean scores measured at four time points between 24 and 36 months ranged from 0·79 to 0·81 (equivalent to 3·95–4·05 in the present study)( 7 ). A study of 21-month-old toddlers reported a VIT of 0·70 (equivalent to 3·5)( 27 ). Another study( 8 ) looked at the variety scores for children aged 27–60 months and their scores ranged from 0·70 to 0·80 (equivalent to 3·5–4·0); these scores were very similar to those of the 3- and 4-year-old children in the present study. There may be methodological differences when comparing FFQ data with diary data; however despite this similar scores were observed. The Raine cohort, a study of the variety of ‘core healthy foods’ eaten by 2-year-olds, reported a mean intake of 7·52 servings/d( 28 ); this is similar to the total daily servings eaten by the ALSPAC cohort (7·2) and by the EDEN cohort (8·9) at age 2 years (Table 3).

Overall the results suggest that children who were never breast-fed or breast-fed for a short period had lower variety scores than those breast-fed for longer. Although the EuroPrevall cohort had a smaller sample size and was less able to detect associations, it showed a trend in the same direction as the larger cohorts. The Raine study also showed that duration of being breast-fed was a predictor of food variety and similar to the present study the variety score only included core/healthy foods( 28 ). The present study has an advantage over the Raine study in having a more diverse range of breast-feeding practices; in the Raine study only 10 % of infants were never breast-fed compared with over 20 % in the ALSPAC, EDEN and EuroPrevall cohorts. In previous work the authors found that the duration of being breast-fed was a predictor of fruit and vegetable intake( 23 ); this new finding shows similar associations with other healthy foods. Breast-feeding is related to better maternal education and better maternal diet quality in some countries( 29 , 30 ). However, in the present analyses the associations reported were independent of maternal education, age and smoking during pregnancy in all of the cohorts and of maternal dietary variety in the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts. Furthermore, the consistency of the associations across cohorts with different breast-feeding rates and different mean variety scores in children is an argument against major confounding of the results. In the Generation XXI cohort there were a higher proportion of mothers who breast-fed and a higher proportion in the low education category compared with the other cohorts, yet their children had the highest diet variety score. Thus maternal education is unlikely to be driving the association between being breast-fed and increased diet variety in this cohort. A biological reason for this finding could be that breast-fed infants are exposed to different flavours in breast milk which may lead to an increase in acceptance of a variety of foods when they are offered to them( 16 ).

Considering the possible importance of the age ‘window’ for the acceptance of new tastes at 4–6 months, we hypothesized that earlier complementary feeding and earlier introduction to fruit and vegetables would be related to greater food variety in later childhood. No associations were observed in three of the cohorts; however, for the age of introduction of vegetables, an association was observed in the ALSPAC cohort. This relationship was not exactly as expected in that there was no association with early introduction of vegetables but later introduction (>6 months) was negatively related to the variety score. This was robust to adjustment for maternal education and maternal HPVS. It could be that the children who are introduced to vegetables after 6 months are pickier about foods and it may be this trait that affects their overall intake of foods later on. In a detailed analysis of vegetable eating in the ALSPAC children, using diet records at age 7 years, a strong determinant of the amount of vegetables eaten was whether or not a child was picky about foods( 20 ).

Maternal HPVS was available in two cohorts; it was a strong predictor of child HPVS. This finding is consistent with the literature which shows that children’s food preferences and intakes are related to those of their parents( 31 ). In the ALSPAC and EDEN cohorts, maternal HPVS in pregnancy was associated with childhood HPVS up to 4 years of age and maternal HPVS at a time point closer to the child’s age (ALSPAC only) was more strongly associated. It is likely therefore that the family mode of eating is an important factor in this association. There are various reasons why maternal consumption may influence the child’s consumption. Mothers can control what their children eat in the home environment by the type of foods that they make accessible and available to their children. Additionally children’s preference may be due to watching their mothers eat these foods. One study observed that toddlers tried the same foods as their mothers rather than those eaten by strangers( 32 ).

The present study has limitations. The scores are derived from four different FFQ that have disparities between them. Some of the FFQ have relatively short lists of foods, while others are more extensive. It may be that the range of foods is not enough to assess variety accurately for all children; however, the core foods that should make up a healthy diet are covered. Other studies have used diet records or 24 h recalls to measure diet variety. These assess diet over a short time frame with information about portion size, thus allowing better quantification of food intake, but covering a much smaller number of foods. The FFQ in the present study have the advantage of assessing habitual diet over a longer period and cover a wider range of foods, but have no information on portion sizes. Our study uses the HPVS as a marker of diet quality and does not attempt to assess quantity of foods consumed, so the lack of portion size information is not a problem. Although it is not possible to validate the use of the HPVS, in the present study the foods recommended in the healthy plate model are based on guidelines for healthy eating and should reflect a diet of high quality.

The study used data collected in four different European countries in parallel analyses, using whenever possible the same confounders. To ensure comparability between the countries the HPVS was calculated in the same way in each. It was not possible to combine the data directly because each country used its own unique FFQ. Parallel analyses were also preferable because of the disparities in sample size, the slightly different ages at which outcomes were measured and the differing availability of some of the confounding variables. The advantage of parallel analysis is that confounding structure is likely to be different between the countries, so if similar observations are made in each cohort this provides stronger evidence of a real effect. In the present study two of the cohorts (EDEN and ALSPAC) had data recorded at two or more ages in the same children and thus some assessment of whether effects are likely to persist was possible.

Conclusion

The present findings indicate that never being breast-fed or being breast-fed for a short duration is associated with pre-school children eating a lower variety of healthy food than those breast-fed for longer. Parents should be encouraged to initiate breast-feeding and continue even after starting complementary feeding. It should be promoted that breast-feeding benefits the health of the mother and the infant, and that the different flavours in breast milk may help children accept a variety of foods during complementary feeding and lead them to have a healthy diet in later childhood. A healthy diet in childhood may help prevent obesity in adolescence and adulthood. The results also indicate that parents should consider the timing of the introduction of vegetables as a complementary food. The results in the ALSPAC cohort favour an early introduction of vegetables before 6 months. Parents should be encouraged to introduce vegetables as the first food, as there is evidence that it is easier to introduce these foods into an infant’s diet at the beginning of complementary feeding than when they are older. Mothers should be informed that they are an important role model for their child and that if they have a healthy diet it is likely their child will too. Further work could be undertaken to investigate if the early feeding practices influence diet in later childhood and adolescence also.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: ALSPAC – The authors are extremely grateful to all families who took part in the ALSPAC study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. EuroPrevall – The authors would like to thank all mothers and infants who participated in the Greek EuroPrevall study. Special thanks also go to Nikolaos G. Papadopoulos, Louisa Damianidi, Eirini Roumpedaki and Vicky Xepapadaki for their valuable contribution in the completion of the study. Generation XXI – The authors gratefully acknowledge the families enrolled in Generation XXI for their kindness, all members of the research team for their enthusiasm and perseverance, and the participating hospitals and their staff for their help and support. EDEN – The authors thank the heads of the maternity units, the investigators and all of the women who participated in the surveys. Financial support: The research leading to the results presented herein received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement number FP7-245012-HabEat. ALSPAC was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the University of Bristol, which provides core support for ALSPAC. EuroPrevall was funded by the European Union through the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6-FOOD-CT-2005-514000). The EDEN study received funding from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM), the French Ministry of Research: Federative Research Institutes and Cohort Programme, the INSERM Human Nutrition National Research Programme and the Diabetes National Research Programme (through a collaboration with the French Association of Diabetic Patients (AFD)), the French Ministry of Health, the French Agency for Environment Security (AFSSET), the French National Institute for Population Health Surveillance (InVS), Paris–Sud University, the French National Institute for Health Education (INPES), Nestlé, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (MGEN), the French-speaking Association for the Study of Diabetes and Metabolism (ALFEDIAM), the National Agency for Research (ANR non-thematic programme) and the National Institute for Research in Public Health (IRESP: TGIR cohorte santé 2008 programme). Generation XXI was funded by the Programa Operacional de Saúde – Saúde XXI, Quadro Comunitário de Apoio III and by the Administração Regional de Saúde do Norte. For follow-up assessments Generation XXI received funding from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, co-funded by FEDER through COMPETE, and from the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. The funders had no role in the design, writing and analysis of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: All authors contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript was done by L.J. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. Ethics of human subject participation: All cohorts have received ethical approval to undertake research.

References

- 1. Krebs-Smith SM, Smiciklas-Wright H, Guthrie HA et al. (1987) The effects of variety in food choices on dietary quality. J Am Diet Assoc 87, 897–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexy U, Sichert-Hellert W & Kersting M (2002) Fifteen-year time trends in energy and macronutrient intake in German children and adolescents: results of the DONALD study. Br J Nutr 87, 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Webb KL, Lahti-Koski M, Rutishauser I et al. (2006) Consumption of ‘extra’ foods (energy-dense, nutrient-poor) among children aged 16–24 months from western Sydney, Australia. Public Health Nutr 9, 1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fox MK (2004) Feeding infants and toddlers study: what foods are infants and toddlers eating? J Am Diet Assoc 104, 1 Suppl. 1, S22–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kudlova E & Rames J (2007) Food consumption and feeding patterns of Czech infants and toddlers living in Prague. Eur J Clin Nutr 61, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gibson EL, Wardle J & Watts CJ (1998) Fruit and vegetable consumption, nutritional knowledge and beliefs in mothers and children. Appetite 31, 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cox DR, Skinner JD, Carruth BR et al. (1997) A Food Variety Index for Toddlers (VIT): development and application. J Am Diet Assoc 97, 1382–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Munoz KA, Krebs-Smith SM, Ballard-Barbash R et al. (1997) Food intakes of US children and adolescents compared with recommendations. Pediatrics 100, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W et al. (2002) Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predict dietary variety in school-aged children? J Nutr Educ Behav 34, 310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y, Bentley ME, Zhai F et al. (2002) Tracking of dietary intake patterns of Chinese from childhood to adolescence over a six-year follow-up period. J Nutr 132, 430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stang J (2006) Improving the eating patterns of infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1 Suppl. 1, S7–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson AS (1998) Take Five, a nutrition education intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intakes: impact on attitudes towards dietary change. Br J Nutr 80, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sahyoun NR, Pratt CA & Anderson A (2004) Evaluation of nutrition education interventions for older adults: a proposed framework. J Am Diet Assoc 104, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L et al. (2008) Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 34, 535–543. e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Savage JS, Fisher JO & Birch LL (2007) Parental influence on eating behavior: conception to adolescence. J Law Med Ethics 35, 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sullivan SA & Birch LL (1994) Infant dietary experience and acceptance of solid foods. Pediatrics 93, 271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mennella JA, Lukasewycz LD, Castor SM et al. (2011) The timing and duration of a sensitive period in human flavor learning: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 93, 1019–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mennella JA, Jagnow CP & Beauchamp GK (2001) Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics 107, E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cooke LJ, Wardle J, Gibson EL et al. (2004) Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public Health Nutr 7, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones LR, Steer CD, Rogers IS et al. (2010) Influences on child fruit and vegetable intake: sociodemographic, parental and child factors in a longitudinal cohort study. Public Health Nutr 13, 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wardle J, Carnell S & Cooke L (2005) Parental control over feeding and children’s fruit and vegetable intake: how are they related? J Am Diet Assoc 105, 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCaffree J (2003) Childhood eating patterns: the roles parents play. J Am Diet Assoc 103, 1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Lauzon-Guillain B, Jones L, Oliveira A et al. (2013) The influence of early feeding practices on fruit and vegetable intake among preschool children in 4 European birth cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr 98, 804–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J et al. (2013) Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’ – the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol 42, 111–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larsen PS, Kamper-Jorgensen M, Adamson A et al. (2013) Pregnancy and birth cohort resources in Europe: a large opportunity for aetiological child health research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 27, 393–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. US Department of Agriculture & US Department of Health and Human Services (2010) Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, 7th ed. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Powers SW, Patton SR & Rajan S (2004) A comparison of food group variety between toddlers with and without cystic fibrosis. J Hum Nutr Diet 17, 523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scott JA, Chih TY & Oddy WH (2012) Food variety at 2 years of age is related to duration of breastfeeding. Nutrients 4, 1464–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McAndrew F, Thompson J, Fellows L et al. (2012) Infant Feeding Survey 2010. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Theofilogiannakou M, Skouroliakou M, Gounaris A et al. (2006) Breast-feeding in Athens, Greece: factors associated with its initiation and duration. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 43, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Wendy B et al. (2002) Children’s food preferences: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Diet Assoc 102, 1638–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harper LV & Sanders KM (1975) The effect of adults eating on young children’s acceptance of unfamiliar foods. J Exp Child Psychol 20, 206–214. [Google Scholar]