Abstract

Objective

To study the effects of school lessons about healthy food on adolescents’ self-reported beliefs and behaviour regarding the purchase and consumption of soft drinks, water and extra foods, including sweets and snacks. The lessons were combined with the introduction of lower-calorie foods, food labelling and price reductions in school vending machines.

Design

A cluster-randomized controlled design was used to allocate schools to an experimental group (i.e. lessons and changes to school vending machines) and a control group (i.e. ‘care as usual’). Questionnaires were used pre-test and post-test to assess students’ self-reported purchase of extra products and their knowledge and beliefs regarding the consumption of low-calorie products.

Setting

Secondary schools in the Netherlands.

Subjects

Twelve schools participated in the experimental group (303 students) and fourteen in the control group (311 students). The students’ mean age was 13·6 years, 71·5 % were of native Dutch origin and mean BMI was 18·9 kg/m2.

Results

At post-test, the experimental group knew significantly more about healthy food than the control group. Fewer students in the experimental group (43 %) than in the control group (56 %) reported bringing soft drinks from home. There was no significant effect on attitude, social norm, perceived behavioural control and intention regarding the consumption of low-calorie extra products.

Conclusions

The intervention had limited effects on students’ knowledge and self-reported behaviour, and no effect on their beliefs regarding low-calorie beverages, sweets or snacks. We recommend a combined educational and environmental intervention of longer duration and engaging parents. More research into the effects of such interventions is needed.

Keywords: Obesity, Environment, Health promotion, Theory of planned behaviour

Young people’s energy intake is increased by the consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and energy-dense extra foods, including sweets, cakes and snacks. This is a risk factor for overweight and obesity, which are associated not only with chronic conditions such as CVD and type 2 diabetes in later life, but also with psychosocial problems at a younger age( 1 , 2 ).

The availability of extra beverages and food products in school vending machines contributes to adolescents’ poor nutritional behaviours( 3 , 4 ). To improve the food environment in schools and minimize the sale of extra products there, it has been proposed that the availability of high-calorie extra beverages and food products in school vending machines should be restricted( 5 , 6 ). While school environments that encourage healthy eating are thought to help combat the increase in overweight in young people, the most effective way of preventing overweight and obesity may be through interventions that target both the change in the obesogenic environment and children’s motivation to change their dietary behaviour( 7 – 10 ).

According to the Theory of Planned Behaviour( 11 ) an individual’s healthy eating behaviour is predicted by personal behavioural beliefs. Adolescents’ soft drink and snack consumption has been shown to be associated with attitudes, perceived behavioural control and intentions regarding the use of beverages and extra foods( 11 – 13 ). Use of soft drinks and snacking behaviour are also assumed to be affected by knowledge about healthy food( 14 , 15 ).

Several studies have found that factors in the school food environment – such as food labelling, school food policy and the availability of extra beverage and food products at schools – have an impact on students’ consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, energy-dense foods, fruit and vegetables( 16 – 20 ). There is also some evidence on the influence of the local food environment on adolescents’ nutritional behaviour( 21 – 23 ). While environmental factors influence behaviour indirectly through personal beliefs( 12 , 13 , 24 ), they also have a direct influence that leads to automatic behaviours independent of an individual’s cognitions( 25 , 26 ). However, there is still only limited evidence from experimental studies on the indirect and direct mechanisms of change in the school food environment.

The present paper examines the effectiveness of a school vending machines project in secondary schools in the Netherlands. This comprised a health-education component aiming at information transfer on healthy food and an environmental-change component intended to change the school vending machines through three strategies: (i) the introduction of lower-calorie foods; (ii) food labelling to give information on the types of product and their energy value; and (iii) lower prices for lower-calorie foods (referred to collectively as the ‘changes to school vending machines’).

A study of the effects of the school vending machines project on the volume of sales from vending machines and on students’ product choices has been described elsewhere; it showed that students made healthier choices about their consumption of beverages and extra foods( 27 ). We have not yet studied the project’s impact on students’ beliefs with regard to consuming healthier foods or on their self-reported purchase behaviour. The following research question is addressed in the present paper: do lessons on healthy food and changes to school vending machines affect the students’ beliefs regarding their consumption of beverages and extra foods, and their self-reported purchase behaviour?

Methods

Participants

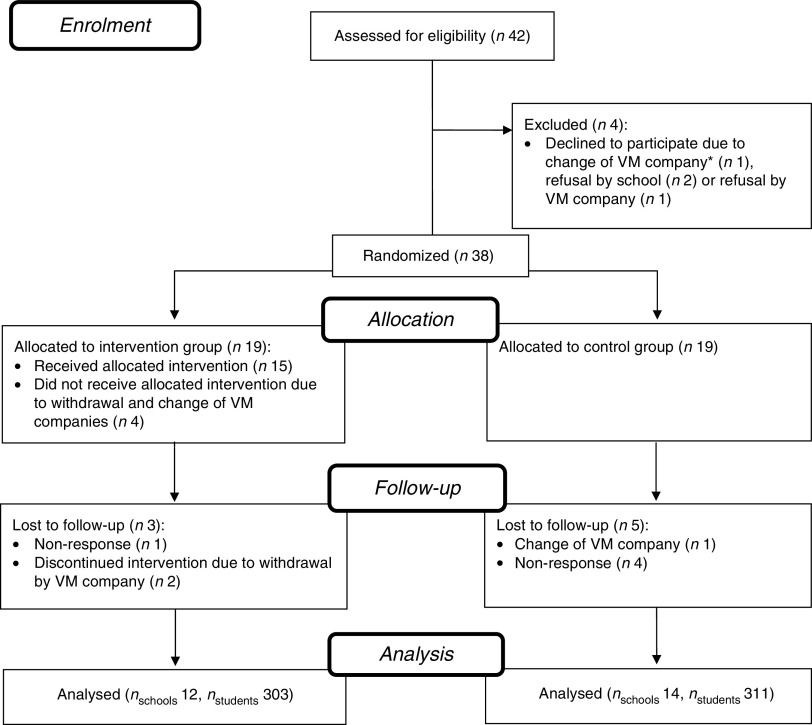

A cluster-randomized controlled design was used. Figure 1 shows the enrolment and follow-up of schools that participated in the study. A total of forty-two schools were recruited in four geographical areas of the Netherlands. As four schools refused to participate, thirty-eight were randomly assigned to the experimental group or control group, stratified by geographical area and level of education. The nineteen experimental schools implemented the school vending machines intervention, while the nineteen control schools made no changes. Seven experimental schools and five control schools dropped out of the study, due to the withdrawal of companies responsible for school vending machines, the withdrawal of schools or non-response to the questionnaire used for data collection. The results presented herein therefore represent data from twelve experimental schools and fourteen control schools. The study protocol was approved by the internal TNO Review Board.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the enrolment and follow-up of schools participating in the present study. *VM company=vending machine company/catering company

Intervention

The intervention consisted of a health-education component and an environmental-change component, and focused on bringing about the following behaviours: (i) the consumption of fewer or no soft drinks, or the consumption of beverages with reduced amounts of sugar or without sugar; and (ii) the consumption of fewer or no extra food products, or the consumption of sweets, cakes or snacks with lower amounts of sugar and fat.

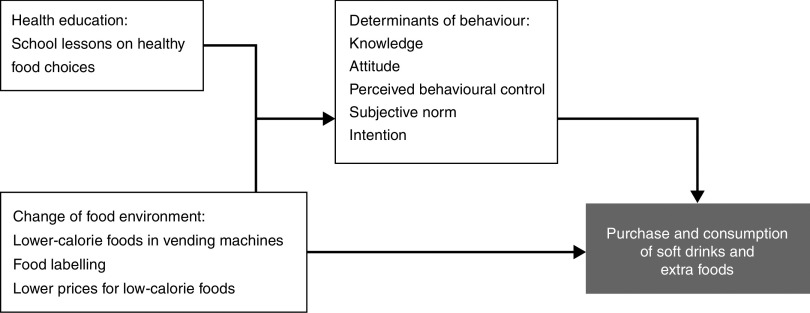

Figure 2 shows a model of the components of the intervention. The health-education component preceded the environmental-change component and comprised school lessons on healthy food choices. The lessons were based on the theoretical model of constructivism( 28 ). Constructivism is based on the didactic principle that students’ understanding and knowledge of what they have been taught in the classroom is constructed on the basis of their own experiences and of their reflection on these experiences. Overall, the lessons used six methods of change within constructivism: (i) stimulating active information transfer; (ii) evaluation of one’s own behaviour; (iii) self-re-evaluation; (iv) environmental re-evaluation; (v) guided learning; and (vi) feedback( 29 ).

Fig. 2.

Model of the intervention’s educational and environmental components and outcomes

The lessons aimed to change students’ knowledge about low-calorie soft drinks and extra foods. They were also intended to change the behavioural determinants described in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (i.e. attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control and intention with regard to consumption of low-calorie soft drinks and extra foods)( 11 ). The following teaching materials were available: (i) a computer-assisted online lesson informing students on the food types available in the school canteen and on the pros and cons of soft drinks and extra foods; (ii) a teacher manual with exercises for students on healthy food topics; (iii) a board game; and (iv) debating exercises intended to explain the pros and cons of consuming soft drinks and extra foods. These materials could be used in a total of five lessons. All lessons were given by the schools’ teachers themselves, who ensured that the students completed the online lessons, game and exercises. The lessons were developed by health education experts from the Netherlands Nutrition Centre and were pre-tested in school students in the target group.

The intervention component intended to produce environmental change consisted of three strategies that were made to the school vending machines in three successive 6-week phases: (i) the introduction of lower-calorie foods; (ii) food labelling; and (iii) lower prices for lower-calorie foods. This component is described in more detail elsewhere( 27 ). In phase 1, the energy-dense extra beverages and food products in the vending machines were replaced by lower-calorie extra products. In phase 2, information labels were attached to all products in the vending machines to indicate their product category (i.e. basic nutrient-rich food that is part of a daily diet, or energy-dense extra products with empty calories); and also to give information on the product’s energy (‘calorie’) value (<100 kcal (<418 kJ), 100–170 kcal (418–711 kJ) or >170 kcal (<711 kJ)). In this stage, flyers and posters containing information on the food types and energy values were distributed among the students. Moreover, the fifth lesson on healthy food choices was given as a reminder and focused on repeating the information provided in the four preceding lessons. Phase 3 followed up the measures of phases 1 and 2 by reducing the prices of lower-calorie products by 0·10 € per product – an average reduction of 10 %( 30 ).

The intervention described in the present paper involves the combination of the educational component (i.e. the school lessons) and environmental component (i.e. the changes to the school vending machines). While the latter was implemented throughout each school and targeted all students, the lessons targeted a smaller group of students aged between 12 and 14 years (secondary school grades 8 and 9). Due to the organizational capacity of the project and the schools, few classes per school were selected to receive the lessons.

Although the Dutch government imposes no regulations on schools with regard to managing the sales of beverages and foods, many schools have a health-promoting school policy. As school meal services are not part of the Dutch tradition, students bring their lunch from home or buy food in the school canteen, from vending machines or in neighbourhood shops. About 60 % of the schools participating in the study allowed students to leave school during breaks and free hours.

Intervention delivery

At the end of the intervention, students completed a questionnaire on the extent to which the various lesson components had been delivered. Less than three-quarters of those in the intervention group reported that the poster displaying basic information on healthy nutrition had been explained to them (69 %). The board game on energy intake and healthy nutrition had been played by 55 % of the students, and only 20 % of students said that they had completed the computer-assisted online lesson. However, many students indicated that they did not remember whether they had received the intervention modules; for example, 29 % did not know whether they had received the online lesson.

Research assistants visited the experimental schools to observe how successful the implementation of the changes to the vending machines had been. On a scale indicating the completeness with which a school had introduced the changes, 69 % of the experimental schools completely or nearly completely implemented the introduction of lower-calorie foods, food labelling and price reductions. The implementation of the three strategies in the schools’ vending machines was less complete for beverages than it was for extra foods( 27 ).

Questionnaire

Per school, a minimum of one class received the lessons on healthy food choices. At T0 (before the start of the lessons) and at T1 (about 6 months later, when the three phases of the environmental change component had been completed), the students attending these lessons answered paper-and-pencil questionnaires in class under their teacher’s supervision. The questionnaire was intended to establish the students’ attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, intentions and behaviours regarding the consumption of soft drinks and sweets, cakes or snacks. It included standard measures derived from questionnaires used in previous studies, such as scales based on determinants of behaviour change taken from the Theory of Planned Behaviour( 31 ).

Behaviour was measured using self-report items on the frequency with which soft drinks and extra foods had been purchased at a shop in the school surroundings, in the school canteen or tuck shop, and from the school vending machines in the previous week. The students were also asked how often they had brought soft drinks and extra foods from home in the previous week. The answer categories varied from ‘never’ (=1) to ‘(almost) every school day’ (=5). Our reason for measuring purchase behaviour was to enable us to establish the selling points from which soft drinks and extra foods had been obtained. Purchasing soft drinks and extra foods or taking them from home to school were considered as proxies for eventually consuming them.

The students’ knowledge of healthy food was measured through seven true or false items such as ‘Boys can eat more sweets, cakes or snacks because they have more muscular tissue than girls’. Attitude was measured using four-item scales on drinking water or light soft drinks (Cronbach’s α=0·53) and on eating low-calorie sweets or extra foods (Cronbach’s α=0·55); for example, ‘I think drinking water or light soft drinks is good for your health’. Answer categories ranged from ‘totally disagree’ (=1) to ‘totally agree’ (=5).

Subjective norm was measured on the basis of two items on students’ opinions of whether their parents thought that they should drink water or light soft drinks, and of whether their friends were in favour of this behaviour. Answer categories ranged from ‘certainly not’ (=1) to ‘certainly’ (=5). The Pearson correlation coefficient r between the two items was 0·46. Similar items were also included on eating low-calorie sweets, cakes or snacks (r for these two items=0·53).

Perceived behavioural control regarding the drinking of light soft drinks or water was measured using two items: ‘If you wanted to lose weight, do you think you would manage to drink light soft drinks or water instead of regular soft drinks?’ and ‘When you are thirsty, do you think you will be able to choose light soft drinks or water rather than regular soft drinks?’ (r=0·28). Similar questions were asked about perceived behavioural control regarding the consumption of low-calorie sweets, cakes or snacks (r=0·45), with answer categories ranging from ‘certainly not’ (=1) to ‘certainly’ (=5). Intention for both behaviours was measured using one item: ‘In the near future, do you plan to increase the frequency with which you drink light soft drinks or water instead of regular soft drinks/with which you eat low-calorie sweets, cakes or snacks rather than high-calorie sweets, cakes or snacks?’ Answer categories ranged from ‘certainly not’ (=1) to ‘certainly’ (=5).

The questionnaire also included items on the following background characteristics: gender, age, country of birth, educational level, height and weight.

Analysis

Dependent variables were inspected for skewness and were dichotomized when this was the case. Scale scores were assessed using factor and reliability analyses. The χ 2 test and independent t test were used to test differences in background characteristics between the experimental and control groups. The effects of the intervention were examined using multilevel regression analysis for continuous outcomes and multilevel logistic regression analysis for dichotomous outcomes. In both analyses, a two-level random intercept model was used, with students at the first level and schools at the second level. The multilevel analyses were performed per outcome, with group (intervention v. control), pre-test score, age, gender, ethnicity, education and BMI as predictor variables. This enabled us to estimate the adjusted effect of group. Also, per outcome, Cohen’s d effect sizes were computed to assess the standardized mean change score between the intervention and control group (i.e. unadjusted effect). The analyses were performed with the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 20·0. A two-tailed significance level of 0·05 was used in all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of students

The pre-test (T0) involved 379 students from nineteen experimental schools and 445 students from nineteen control schools. A total of 303 students from twelve experimental schools and 311 from fourteen control schools also participated in the post-test (T1; Fig. 1). Table 1 shows that the mean age of the students in the intervention group (13·7 (sd 0·7) years) differed significantly from that of students in the control group (13·5 (sd 0·7) years). Most students were in grade 8 (90 %) and of native origin (72 %). Significantly more students in the experimental group were female (59 %) and in lower-level education, i.e. vocational training combined with theoretical education (56 %), than those in the control group. Mean BMI differed significantly between the study groups and was 19·2 (sd 3·5) kg/m2 in the experimental group and 18·5 (sd 2·6) kg/m2 in the control group.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of students at pre-test in the intervention group and control group; cluster-randomized controlled intervention providing lessons on healthy food and changes to school vending machines in secondary schools in the Netherlands

| Intervention group (n 303) | Control group (n 311) | Total group (n 614) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or n | sd or % | Missing | Mean or n | sd or % | Missing | Mean or n | sd or % | |

| Age (years)* | 13·7 | 0·7 | 5 | 13·5 | 0·7 | 5 | 13·6 | 0·7 |

| Sex (male)* | 124 | 40·9 | – | 154 | 49·5 | – | 278 | 45·3 |

| Ethnicity (native)** | 222 | 74·7 | 6 | 207 | 68·3 | 8 | 429 | 71·5 |

| Education* | – | – | ||||||

| Low | 171 | 56·4 | 143 | 46·0 | 314 | 51·1 | ||

| Middle | 88 | 29·0 | 70 | 22·5 | 158 | 25·7 | ||

| High | 44 | 14·5 | 98 | 31·5 | 142 | 23·1 | ||

| Grade 8 | 268 | 88·4 | – | 284 | 91·3 | – | 552 | 89·9 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 19·2 | 3·5 | 40 | 18·5 | 2·6 | 35 | 18·9 | 3·1 |

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation for age and BMI; otherwise as number and percentage.

*P<0·05; **P<0·10.

Effects

Multilevel regression analysis showed that the school lessons and changes to vending machines had a significant effect on knowledge. At post-test, students in the intervention group had more knowledge of nutrition, energy intake and portion size than those in the control group (Table 2). No effect was found on the behavioural determinants of attitude, social norm, perceived behavioural control and intention with respect to drinking light drinks or water and eating low-calorie sweets, cakes or snacks.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics at pre- and post-test on knowledge of healthy foods and behavioural determinants of the consumption of low-calorie beverages and extra foods for the intervention and control group; cluster-randomized controlled intervention providing lessons on healthy food and changes to school vending machines in secondary schools in the Netherlands. Results of multilevel regression analyses are shown per outcome

| Intervention group | Control group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Intervention v. control | |||||||||

| Variable | n † | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | n † | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | B ‡ | 95 % CI | ES§ |

| Knowledge | 249 | 4·3 | 1·0 | 5·0 | 1·1 | 264 | 4·3 | 1·2 | 4·5 | 1·2 | 0·46** | 0·26, 0·66 | 0·33 |

| Light drinks and water | |||||||||||||

| Attitude | 247 | 3·4 | 0·7 | 3·6 | 0·8 | 259 | 3·4 | 0·7 | 3·4 | 0·7 | 0·07 | −0·10, 0·24 | 0·13 |

| Social norm | 254 | 2·6 | 1·0 | 2·6 | 1·0 | 265 | 2·5 | 0·9 | 2·6 | 1·0 | −0·06 | −0·27, 0·14 | −0·08 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 254 | 4·0 | 0·9 | 4·1 | 0·9 | 267 | 4·0 | 0·9 | 4·0 | 1·0 | 0·05 | −0·12, 0·22 | 0·03 |

| Intention | 254 | 3·3 | 1·3 | 3·3 | 1·3 | 267 | 3·1 | 1·4 | 3·3 | 1·3 | −0·15 | −0·43, 0·13 | −0·16 |

| Low-calorie extra foods | |||||||||||||

| Attitude | 248 | 2·9 | 0·5 | 3·1 | 0·8 | 258 | 2·9 | 0·5 | 3·1 | 0·8 | 0·02 | −0·19, 0·22 | 0·08 |

| Social norm | 258 | 2·6 | 1·0 | 2·6 | 1·0 | 266 | 2·6 | 0·9 | 2·6 | 1·0 | −0·07 | −0·25, 0·11 | −0·03 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 256 | 3·7 | 1·0 | 3·7 | 1·1 | 265 | 3·7 | 1·0 | 3·6 | 1·0 | 0·00 | −0·17, 0·17 | 0·00 |

| Intention | 258 | 3·1 | 1·3 | 3·2 | 1·3 | 267 | 2·9 | 1·2 | 3·1 | 1·2 | −0·08 | −0·35, 0·18 | −0·10 |

**P<0·01.

Sample size per group varies due to missing data on post-test and covariates.

B is regression coefficient of the group effect in multilevel analysis, adjusted for pre-test, age, gender, ethnicity, education and BMI.

ES is effect size calculated as the standardized difference in mean observed change scores between intervention and control group (Cohen’s d).

Table 3 shows a decline in the intervention group at T1 in self-reported purchases of soft drinks and extra foods from school vending machines, school canteens or tuck shops, and shops near the school. However, similar decreases were also shown in the control group, except in the category of taking soft drinks from home. At T1, students in the intervention group reported bringing drinks and extra foods from home less often. In contrast, the control group brought soft drinks from home more often. Adjusted for the effect of pre-test score, age, gender, ethnicity, education and BMI, the difference in percentage (43 % v. 56 %) between the intervention and control group was significant (P<0·05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects on self-reported purchase of soft drinks and sweets or cakes over the last week: proportions per group at pre-test and post-test (1= one or more times per week; 0= never); cluster-randomized controlled intervention providing lessons on healthy food and changes to school vending machines in secondary schools in the Netherlands. Results of multilevel logistic regression analyses are shown per outcome

| Intervention group | Control group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Intervention v. control | ||||

| n † | % | % | n † | % | % | OR‡ | 95 % CI | |

| Soft drinks | ||||||||

| School vending machine | 248 | 25 | 19 | 255 | 25 | 20 | 1·01 | 0·51, 1·98 |

| School canteen or tuck shop | 248 | 19 | 18 | 259 | 20 | 17 | 1·10 | 0·57, 2·11 |

| Shop in the school surroundings | 248 | 37 | 34 | 259 | 38 | 36 | 1·00 | 0·58, 1·74 |

| Brought from home | 252 | 47 | 43 | 259 | 52 | 56 | 0·55* | 0·34, 0·88 |

| Extra foods | ||||||||

| School vending machine | 253 | 29 | 20 | 262 | 33 | 20 | 1·02 | 0·54, 1·93 |

| School canteen or tuck shop | 253 | 34 | 25 | 257 | 48 | 30 | 0·86 | 0·45, 1·63 |

| Shop in the school surroundings | 258 | 52 | 45 | 265 | 51 | 49 | 0·89 | 0·53, 1·51 |

| Brought from home | 253 | 57 | 52 | 262 | 58 | 52 | 0·95 | 0·64, 1·41 |

*P<0·05.

Sample size per group of participants without missing data on post-test and covariates.

Odds ratio of the group effect adjusted for the effects of pre-test, age, gender, ethnicity, education and BMI.

Discussion

The present study tested the effectiveness of a vending machines project in secondary schools in the Netherlands, whose intention had been to change the students’ behaviour with regard to the consumption of beverages and extra products, including sweets and snacks. An education component consisted of lessons on healthy food choices. An environmental-change component consisted of: (i) increasing the availability of lower-calorie foods; (ii) labelling products so as to give information on their type and energy value; and (iii) reducing the prices of lower-calorie foods. Our results show that the intervention had a significant effect on the students’ knowledge of energy intake and portion sizes. Our intervention had no effect on the students’ attitude, social norm, behavioural control and intention with regard to consumption of low-calorie soft drinks or water and low-calorie extra foods. Neither did it have a significant impact on the self-reported purchase of soft drinks and extra foods from selling points inside and outside the schools. However, there was a significant effect on taking beverages from home to school: in the experimental group, the proportion of students who did so decreased. As the measurements were made in late spring, when there were days of sunshine and higher temperatures, a seasonal effect may partly explain the increase in the number of students in the control group who brought beverages from home at post-test. As the self-reported purchase of beverages from vending machines and shops in the school neighbourhood dropped in the control group, one source of extra products may have been substituted for another. There seemed no such substitution in the experimental group, because purchase or acquisition from all sources decreased. The decrease in the experimental and control groups of purchases from the sales points in and around the school may also be due to a decrease in the number of school lessons before the summer vacation because of tests and exams. But, the positive impact of the intervention on the decrease in the number of respondents in the experimental group who brought soft drinks from home while the purchase of all sources decreased is a promising result of the school lessons and environmental component.

The limited results of the study can be explained on the basis of the poor implementation of the school lessons on healthy nutrition and change of the food environment in the schools. Another explanation for the absence of effect on the students’ attitudes, social norms, behavioural control and intention may lie in the 3-month time lag between the last lesson on healthy food and the post-test measurement. The short-term effects of the lessons – i.e. those immediately after their completion – are unknown and any effect in the intervention group may have faded before the post-test measurement. Recent meta-analyses and reviews examining school-based obesity prevention programmes that focused on changing lifestyles found greater effects in longer interventions – those that lasted several years – and in those in which parents were involved( 32 – 34 ). The intervention evaluated in the present paper took 6 months at maximum and parents did not participate in it.

Strengths and limitations of the study

One strength of the present study is its random allocation of schools to the experimental and control groups using an evaluation design in the real-life setting of Dutch secondary schools. The intervention effects were statistically corrected in the analyses for the imbalance in characteristics of the study groups. Another strength is that we sought to assess the sustainable benefits of the lessons by measuring their longer-term effects.

A limitation is that the study design did not make it possible to distinguish between an effect of the environmental change in the vending machines or of the lessons focused on changing students’ personal beliefs. Another limitation is that we did not account for school nutrition policies, the influence of the attractiveness of school food facilities or the food environment in the school’s vicinity. The reliability of the scales was limited, as we had to limit the number of items in the self-report questionnaire, which had to be administered during school classes. Further questionnaire development and research into the validity of scales are recommended.

A final limitation is that, for reasons of organizational capacity, only a limited number of school classes took the lessons on healthy nutrition that were developed specially for the vending machines project. Naturally, to assess the effectiveness of the intervention, we administered questionnaires only to students who had had the lessons and were also exposed to the changes to the vending machines.

Implications for practice and research

Although the study found only limited effects on the students’ knowledge and behaviour, a combined educational and environmental intervention to promote healthy nutrition behaviour is regarded as the most promising( 7 – 10 ). It is recommended that any sustainable change in the school food environment is introduced over a longer period( 32 – 34 ). To change students’ beliefs on the consumption of healthy food, it will also be necessary to provide them with information on why the changes in food provision are made. The education on healthy nutrition in the school class should therefore be repeated and tailored to the different needs and perceptions of adolescents in different age categories.

The vending machines intervention did not engage parents in the preventive measures. Given the effect on students’ home-related habit of taking beverages to school, we recommend that parents are involved. If parents were involved in developing and running the vending machine intervention, and if an appeal were made to parenting behaviour related to the home food environment, it might be possible to influence the risk that students would take high-calorie beverages from home, as we saw in the control group( 35 – 37 ). To increase the effectiveness of the intervention, the completeness of its delivery should also be promoted by training teachers and school staff to give the healthy nutrition lessons and to implement the measures intended to change the school food environment.

There have been very few randomized studies on environmental strategies aimed at changing nutrition behaviour. As environmental strategies gain greater political support, more evidence is needed on the effectiveness of these studies( 32 ). The absence of an effect on self-reported purchases of one or more extra products from selling points inside or outside the school contrasts with our earlier report on an effect on sales of lower-calorie beverages and extra food products in schools participating in this project( 27 ). When labelling and reduced prices were combined with a greater availability of lower-calorie foods, sales data showed a larger uptake of lower-calorie foods and beverages; overall, the sales of products from the school vending machines neither rose nor fell. Similar outcomes have been found in other studies of the effect of the school environment on food consumption( 16 – 19 ).

Our own findings suggest that an intervention that comprises an environmental and educational intervention does not raise students’ awareness of their cognitions and behaviour with regard to the consumption of soft drinks and extra foods; although analysis of sales data shows that behaviour change can be achieved through environmental incentives. Other studies found that attitudes, perceived behavioural control and intentions had a mediating effect on the relationship between food environment and soft drink and snacking behaviour( 12 , 13 , 24 ). Further research is needed into the direct and indirect effects of stimuli relevant to the food environment in schools.

Few studies of school interventions have combined data on actual purchasing behaviour with data on students’ motivation regarding the consumption of extra products. This vending machines project measured both types of data, although it measured sales of food at the school level( 27 ) and behavioural determinants at student level. To make it possible to draw conclusions on the relationships between behaviour and cognitions with regard to the intake of extra products, we recommend that food purchases are also measured objectively at student level. We also recommend that an experimental study with several study arms is started that makes it possible to differentiate between schools that merely introduce changes in the school food environment, those that only implement teaching on healthy food and those that combine the educational components with the environmental change ones. Due to the data-collection techniques and number of schools required, such studies are costly, and considerable effort has to be made to ensure that the school food environment intervention and the education component are implemented in full.

Conclusion

School students’ knowledge of healthy food was influenced by the combination of lessons on healthy food with three factors: (i) the greater availability of lower-calorie foods in school vending machines; (ii) food labelling that provided information on the types of food and their energy value; and (iii) lower prices for lower-calorie foods in secondary schools. In the experimental schools, this combination also positively affected students’ self-reported behaviour on taking beverages to school from home. We recommend a combined educational and environmental intervention of longer duration that targets the school environment and engages parents. Further research is needed into the direct and indirect effects of stimuli relevant to the food environment in schools.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, ZonMw (grant number 6320.0007). ZonMw had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: P.L.K. had the primary responsibility for protocol and intervention development, and for data collection and analysis; he also supervised the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. N.M.C.v.K. performed the data collection and analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. E.D. performed the data analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. G.B. and J.S. developed and organized the intervention and participated in the development of the study protocol. Ethics of human subject participation: The study protocol was approved by the internal TNO Review Board.

References

- 1. Gibson S (2008) Sugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence from observational studies and interventions. Nutr Res Rev 21, 134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moreno LA, Rodríguez G, Fleta J et al. (2010) Trends of dietary habits in adolescents. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 50, 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van den Berg SW, Mikolajczak J & Bemelmans WJE (2013) Changes in school environment, awareness and actions regarding overweight prevention among Dutch secondary schools between 2006–2007 and 2010–2011. BMC Public Health 13, 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woodruff SJ, Hanning RM & McGoldrick K (2010) The influence of physical and social contexts of eating on lunch-time food intake among Southern Ontario, Canada, middle school students. J Sch Health 80, 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Larson N & Story M (2010) Are ‘competitive foods’ sold at school making our children fat? Health Aff (Millwood) 29, 430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weicha JL, Finkelstein D, Troped PJ et al. (2006) School vending machine use and fast-food restaurant use are associated with sugar-sweetened beverage intake in youth. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1624–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Cauwenberghe E, Spittaels H et al. (2011) School-based interventions promoting both physical activity and healthy eating in Europe: a systematic review within the HOPE project. Obes Rev 12, 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Safron M, Cislak A, Gaspar T et al. (2011) Effects of school-based interventions targeting obesity-related behaviors and body weight change: a systematic umbrella review. Behav Med 37, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T et al. (2003) Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obes Res 11, Suppl., S23–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Story M, Nanney MS & Schwartz MB (2009) Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q 87, 71–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ezendam NPM, Evans AE, Stigler MH et al. (2010) Cognitive and home environmental predictors of change in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents. Br J Nutr 103, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van der Horst K, Timperio A, Crawford D et al. (2008) The school food environment. associations with adolescent soft drink and snack consumption. Am J Prev Med 35, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. French SA, Story M, Hannan P et al. (1999) Cognitive and demographic correlates of low-fat vending snack choices among adolescents and adults. J Am Diet Assoc 99, 471–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C et al. (1999) Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 99, 929–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. An R (2013) Effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: a review of field experiments. Public Health Nutr 16, 1215–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C et al. (2009) School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc 109, 2 Suppl., S91–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jaime PC & Lock K (2009) Do school based food and nutrition policies improve diet and reduce obesity? Prev Med 48, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wordell D, Daratha K, Mandal B et al. (2012) Changes in a middle school food environment affect food behavior and food choices. J Acad Nutr Diet 112, 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chriqui JF, Pickel M & Story M (2014) Influence of school competitive food and beverage policies on obesity, consumption, and availability: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 168, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He M, Tucker P & Gilliland J (2012) The influence of local food environments on adolescents’ food purchasing behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9, 1458–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Skidmore P, Welch A, Van Sluijs E et al. (2010) Impact of neighbourhood food environment on food consumption in children aged 9–10 years in the UK SPEEDY (Sport, Physical Activity and Eating behaviour: Environmental Determinants in Young people) study. Public Health Nutr 13, 1022–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith D, Cummins S, Clark C et al. (2013) Does the local food environment around schools affect diet? Longitudinal associations in adolescents attending secondary schools in East London. BMC Public Health 13, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tak NI, Te Velde SJ, Oenema A et al. (2011) The association between home environmental variables and soft drink consumption among adolescents. Exploration of mediation by individual cognitions and habit strength. Appetite 56, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kremers SP, de Bruijn GJ, Visscher TL et al. (2006) Environmental influences on energy balance-related behaviors: a dual-process view. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 3, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wansink B (2004) Environmental factors that increase the food intake and consumption volume of unknowing consumers. Annu Rev Nutr 24, 455–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kocken PL, Eeuwijk J, Van Kesteren NM et al. (2012) Promoting the purchase of low-calorie foods from school vending machines: a cluster-randomized controlled study. J Sch Health 82, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Piaget J (1963) The Origin of Intelligence in Children. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bartholomew KL, Parcel GS, Kok G et al. (2011) Planning Health Promotion Programs. An Intervention Mapping Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- 30. French SA, Jeffery RW, Story M et al. (2001) Pricing and promotion effects on low-fat vending snack purchases: the CHIPS Study. Am J Public Health 91, 112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Conner M & Norman P editors (2005) Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models, 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khambalia AZ, Dickinson S, Hardy LL et al. (2012) A synthesis of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based behavioural interventions for controlling and preventing obesity. Obes Rev 13, 214–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sobol-Goldberg S, Rabinowitz J & Gross R (2013) School-based obesity prevention programs: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21, 2422–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guerra PH, Nobre MRC, da Silveira JAC et al. (2014) School-based physical activity and nutritional education interventions on body mass index: a meta-analysis of randomised community trials – Project PANE. Prev Med 61, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kremers SPJ, Brug J, De Vries H et al. (2003) Parenting style and adolescent fruit consumption. Appetite 41, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pearson N, Atkin AJ, Biddle SJH et al. (2010) Parenting styles, family structure and adolescent dietary behaviour. Public Health Nutr 13, 1245–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cislak A, Safron M, Pratt M et al. (2012) Family-related predictors of body weight and weight-related behaviours among children and adolescents: a systematic umbrella review. Child Care Health Dev 38, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]