Abstract

Objective

Malnutrition in Africa has not improved compared with other regions in the world. Investment in the build-up of a strong African research workforce is essential to provide contextual solutions to the nutritional problems of Africa. To orientate this process, we reviewed nutrition research carried out in Africa and published during the last decade.

Design

We assessed nutrition research from Africa published between 2000 and 2010 from MEDLINE and EMBASE and analysed the study design and type of intervention for studies indexed with major MeSH terms for vitamin A deficiency, protein–energy malnutrition, obesity, breast-feeding, nutritional status and food security. Affiliations of first authors were visualised as a network and power of affiliations was assessed using centrality metrics.

Setting

Africa.

Subjects

Africans, all age groups.

Results

Most research on the topics was conducted in Southern (36 %) and Western Africa (34 %). The intervention studies (9 %; n 95) mainly tested technological and curative approaches to the nutritional problems. Only for papers on protein–energy malnutrition and obesity did lead authorship from Africa exceed that from non-African affiliations. The 10 % most powerfully connected affiliations were situated mainly outside Africa for publications on vitamin A deficiency, breast-feeding, nutritional status and food security.

Conclusions

The development of the evidence base for nutrition research in Africa is focused on treatment and the potential for cross-African networks to publish nutrition research from Africa remains grossly underutilised. Efforts to build capacity for effective nutrition action in Africa will require forging a true academic partnership between African and non-African research institutions.

Keywords: Malnutrition, Research, Africa

This is a critical time for Africa to address the nutritional challenges it faces. As the international community prepares to assess success towards meeting the Millennium Development Goals by 2015, progress in improving nutrition in Africa is still a major cause for concern. Undernutrition rates remain high, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and may even have risen during the last decades in some African countries( 1 ). The ‘double burden’ of concurrent undernutrition and overnutrition increases mortality and morbidity, and has serious economic and social repercussions( 2 ). Recent global events, including the food price crisis, global economic recession and climate change, present new challenges to Africa in the field of nutrition, food and nutrition security( 3 ).

To generate the necessary evidence to tackle nutrition issues in Africa, the build-up of a strong African research workforce is essential. Strong national research systems are needed to maximise the incorporation of local context and determinants of malnutrition( 4 ). Adequate nutrition research from Africa is therefore pivotal to both orient and drive local, national and international action to tackle nutrition problems on the continent( 5 ). In addition, it is important that research in Africa generates context-specific evidence from intervention studies( 6 ). Given the public health dimension of nutritional problems in Africa and the scarcity of resources to address them, intervention studies from Africa are critical, as these generate the evidence base and guide policy makers and donors to decide on which policy options are effective to address malnutrition in Africa.

The recent international attention( 7 , 8 ) and substantial political commitments to nutrition( 9 ) offer a window of opportunity to support and strengthen African nutrition research. To orientate this process, benchmarking of current research topics, study designs and academic collaboration in nutrition research in Africa is a timely contribution. The present study assessed the status of nutrition research in Africa over the last decade. It is part of the SUNRAY project (www.sunrayafrica.co.za), a European Union-funded project that aims to develop a sustainable nutrition research agenda for Africa.

Methods

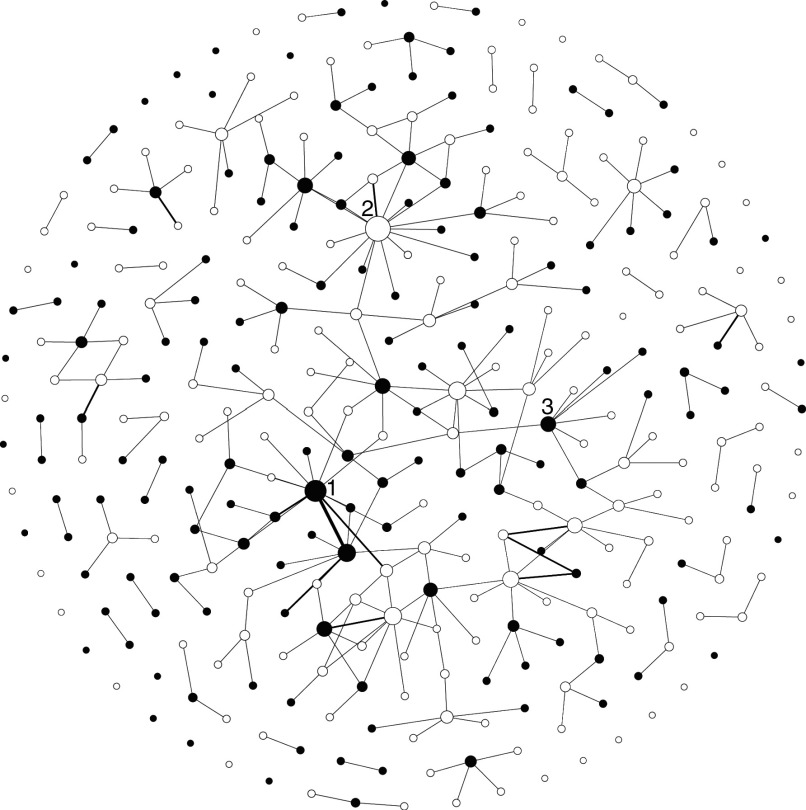

Retrieving and assessing the extent of published nutrition research from Africa

First, we assessed the global volume of studies published between 2000 and 2010. We searched MEDLINE (through PubMed) and EMBASE with the comprehensive search syntax presented in Table 1. We used thesaurus terms (MeSH in PubMed, Emtree in EMBASE) to increase the specificity of the search index( 10 ). Human studies or studies with relevance to human nutrition that were published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2010 in African countries were eligible without language restriction. We included only original studies and excluded letters, comments, editorials, case reports and systematic reviews. All references were imported into EndNote X2 and duplicates were removed automatically. The selection process of papers is presented in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy to retrieve publications on nutrition research in Africa

| Search #1: (Algeria* OR Angola* OR Benin* OR Botswan* OR ‘Burkina Faso’ OR Burkinabe OR Burund* OR Cameroon* OR ‘Cape Verde’ OR ‘Cape Verdean’ OR ‘Central African Republic’ OR Chad* OR Comoros OR Comorian OR ‘Democratic Republic of Congo’ OR ‘Republic of Congo’ OR Congo OR Congolese OR ‘Cote d'Ivoire’ OR ‘Republic of Cote d'Ivoire’ OR ‘Ivory Coast’ OR Ivorian OR Djibouti* OR Egypt* OR ‘Arab Republic of Egypt’ OR ‘Equatorial Guinea’ OR Guinean OR Eritrea* OR Ethiopia* OR Gabon* OR Gambia* OR Ghana* OR Guinea OR ‘Guinea-Bissau’ OR Kenya OR Kenyan OR Lesotho OR Liberia* OR Libya* OR Madagasca* OR Malawi* OR Mali OR Malian OR Mauritania* OR Mauritius OR Mauritian OR Morocc* OR Mozambique OR Mozambican OR Namibia* OR Niger* OR Nigeria* OR Rwanda* OR ‘Sahara Occidental’ OR ‘Sao Tome and Principe’ OR Sao Tomean OR Senegal* OR Seychell* OR ‘Sierra Leone’ OR ‘Sierra Leonian’ OR Somali* OR ‘South Africa’ OR ‘South African’ OR Sudan* OR Swaziland OR Swazi OR Tanzania* OR Togo* OR Tunisia* OR Uganda* OR ‘Western Sahara’ OR Zambia* OR Zimbabwe* OR Africa* (MH)) AND (‘nutrition policy’ (MH) OR ‘nutrition disorders’ (MH) OR ‘nutrition therapy’ (MH) OR ‘feeding methods’ (MH) OR ‘Nutritional Physiological Phenomena’ (MH) OR ‘food industry’ (MH) OR ‘food safety’ (MH) OR ‘nutritional sciences’ (MH) OR ‘nutrition assessment’ (MH) OR ‘food chain’ (MH) OR ‘food-drug interactions’ (MH) OR ‘legislation, food’ (MH) OR ‘food preferences’ (MH) OR ‘food hypersensitivity’ (MH) OR ‘foodborne diseases’ (MH) OR ‘food deprivation’ (MH) OR ‘food and beverages’ (MH) OR ‘diet records’ (MH) OR ‘drinking behaviour’ (MH)) NOT (editorial(ptyp) OR letter(ptyp) OR comment(pt) OR news(ptyp) OR addresses(ptyp) OR systematic(sb) OR ‘Case Reports’ (Publication Type)) |

| Search #2: (animal (MeSH) NOT human (MeSH)) |

| Search #3: #1 NOT #2 |

The search syntax was developed for PubMed and modified for use in EMBASE. Emtree terms equivalent to MeSH terms were used.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of selection of studies for the review of nutrition research conducted in Africa during the last decade

Second, we conducted an in-depth analysis of a set of topics considered of public health importance for Africa( 2 , 6 ): vitamin A deficiency, protein–energy malnutrition, obesity, breast-feeding, nutritional status and food security (MeSH: ‘food supply’). Large categories such as ‘food’ (n 1010) or ‘diet’ (n 633) were too generic for a more detailed assessment. Studies related to the composition of foods without reference to the nutritional status of human populations were considered only marginally appropriate for the purpose of the present study. A specific search filter was applied to obtain papers from the database that had those terms tagged as a ‘major topic’ in the MeSH (for MEDLINE) and Emtree (for EMBASE) thesaurus (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). To evaluate the type of evidence produced, we were interested in the objective and study designs of the interventions and calculated the proportion of the research output that originated from intervention studies for the different topics reviewed. The information on study design was extracted manually. To assess whether the proportion of intervention studies on the total volume of research output was specific to nutrition research in Africa, we constructed a syntax in PubMed that combined our search syntax with (AND operator) the MeSH term for Europe, USA, Germany and China. The proportion of intervention studies was subsequently determined with the filter tool and included clinical trials, controlled clinical trials and randomised controlled trials.

Assessing affiliations of authors

Co-authorship on scientific publications was used as a proxy for collaboration and academic performance of scholars, as suggested previously( 11 ). The institutional affiliation and country of the authors as listed on the papers were extracted manually from the full text version of the articles. Shared authorship of institutes for each of the research topics assessed was visualised as a network structure using the Fruchterman–Reingold algorithm( 12 ) in Gephi software( 13 ). We generated network views with the size of each node and connector proportional to the number of connections. The affiliation of the first author of the paper was considered a proxy for the organisation that took a lead role in the research and its publication. To visualise the institutional networking behind the publication of nutrition research, we extracted the affiliation of the first authors and identified its associations with the affiliations of the co-authors. If more than one affiliation was listed under the first author, all were included. Powerful institutes in the network were identified using centrality measures( 14 ). Bonacich metrics were calculated in UCINET software( 15 ) for this purpose. Parameters were set so that affiliations publishing on a specific topic were considered more powerful in the network when (i) they had more connections and (ii) when their connections were less connected to others. The power of the affiliations in the network was quantified with a β coefficient. We used normalised β values to compare centrality metrics across the different nutritional topics. We subsequently identified the most powerful 10 % of affiliations in the network and categorised them into those based in Africa or not.

Results

Global scientific production

A total of 10 495 original papers on nutrition research conducted in Africa were retrieved (Fig 1). The ten most popular major MeSH term categories were ‘food’ (n 1010), ‘diet’ (n 633), ‘breastfeeding’ (n 366), ‘food contamination’ (n 325), ‘nutritional status’ (n 322), ‘obesity’ (n 298), ‘nutritional physiological phenomena’ (n 293), ‘malnutrition’ (n 269), ‘nutrition disorders’ (n 234) and ‘food microbiology’ (n 209). Supplemental Table 1 contains the number of papers per MeSH category from the papers retrieved.

Major topics

Research papers indexed as the major topics of vitamin A deficiency, protein–energy malnutrition, obesity, nutritional status, breast-feeding and food security accounted for 13 % (n 1337) of the original papers retrieved. Most research on the topics indexed as major MeSH terms was conducted in Southern (36 %) and Western Africa (34 %). The least research originated from Central Africa (an average of 7 % of published papers per topic). South Africa (15 %) followed by Nigeria (10 %) and Kenya (8 %) were the countries that hosted the highest proportion of published papers.

The majority (78 %) of authors’ affiliations were academic institutions or hospitals. For a large proportion (ranging from 26 % to 63 %) of the papers analysed, the first author’s affiliation was located outside Africa with a fair balance between organisations located in the USA and Europe (Table 2). Affiliations based in South Africa and Nigeria published more papers compared with their peers in other countries.

Table 2.

Published articles (number and percentage) per topic of research, with first author’s country of affiliation, for studies in nutrition research in Africa during the last decade

| Vitamin A deficiency | Protein–energy malnutrition | Obesity | Breast-feeding | Nutritional status | Food security | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Europe (including UK) | 16 | 23 | 14 | 20 | 31 | 14 | 46 | 15 | 76 | 26 | 30 | 24 |

| USA and Canada | 16 | 22 | 13 | 18 | 21 | 10 | 78 | 25 | 64 | 22 | 39 | 31 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Africa | 37 | 51 | 42 | 58 | 164 | 73 | 158 | 52 | 145 | 49 | 47 | 37 |

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Tunisia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Kenya | 5 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 4 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 7 |

| Nigeria | 4 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 6 | 34 | 11 | 25 | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Malawi | 2 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 8 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 68 | 30 | 44 | 15 | 34 | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Country not specified | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | <1 | 21 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 |

| All | 72 | 100 | 72 | 100 | 224 | 100 | 306 | 100 | 294 | 100 | 127 | 100 |

Countries with all percentages of published papers <5 % are not tabulated.

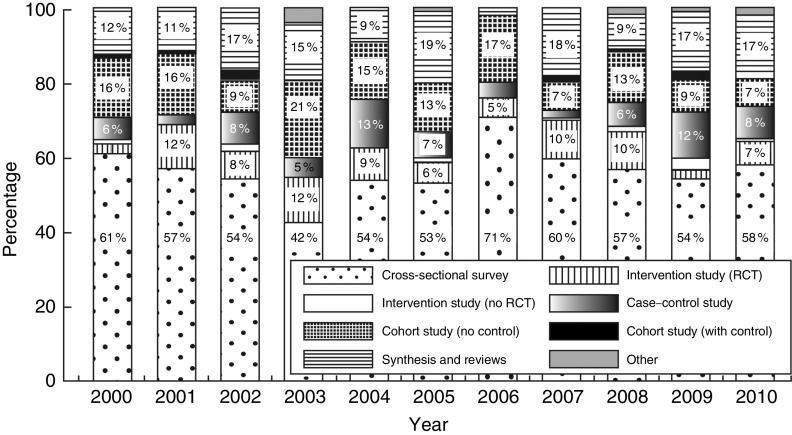

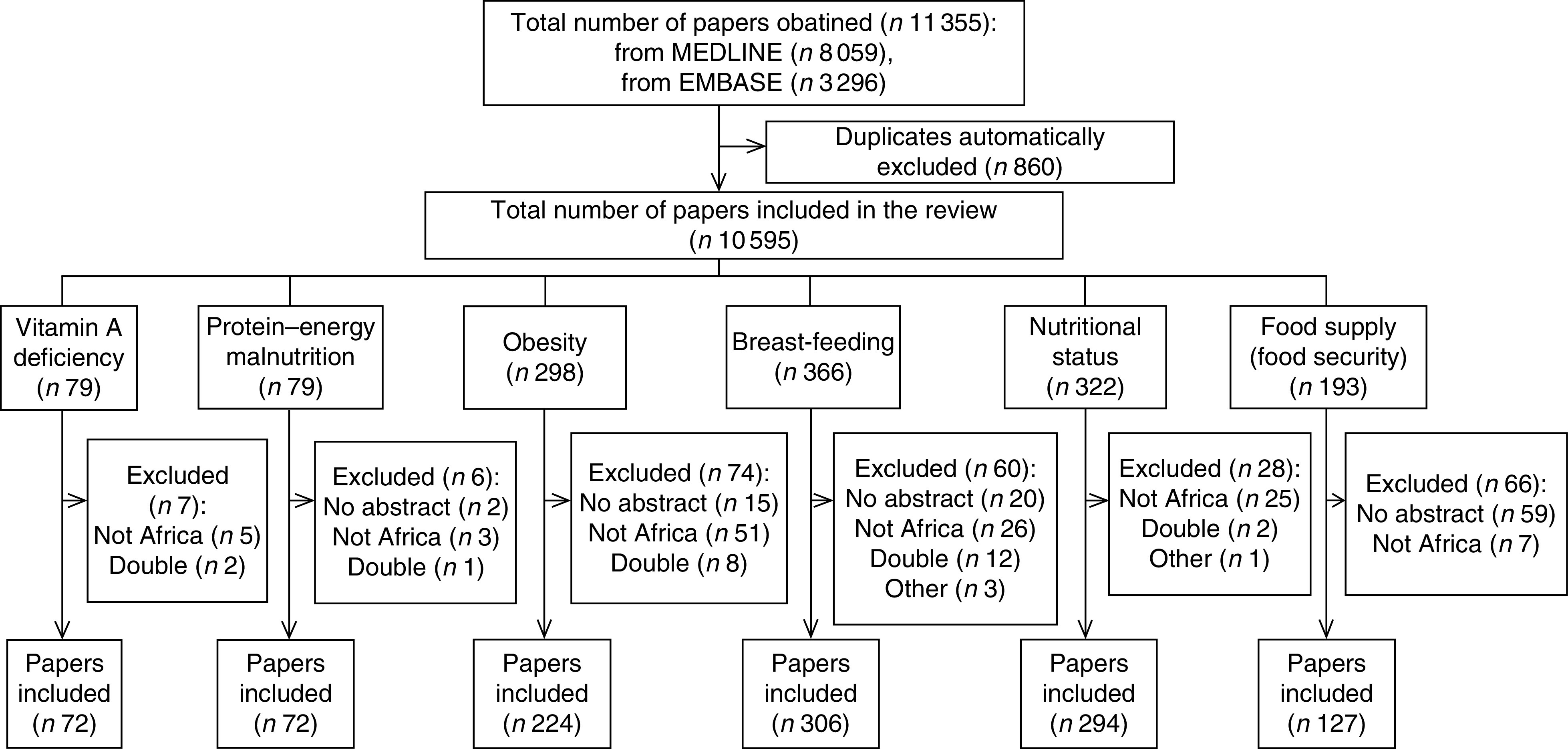

Figure 2 shows that more than half (on average 57 %) of the studies conducted on the topics analysed were observational studies and in particular cross-sectional surveys. Intervention studies accounted for 9 % (n 95) of the papers analysed and this proportion remained fairly constant over the period of analysis. The proportion of intervention studies was comparable with those obtained from our analysis for Europe (8 %), Germany (11 %) and the USA (12 %), but was higher than in China (4 %).

Fig. 2.

Designs of nutrition research conducted in Africa for six major topics during the last decade. Only papers indexed as the major MeSH term ‘vitamin A deficiency’ (n 72), ‘protein–energy malnutrition’ (n 72), ‘obesity’ (n 224), ‘breastfeeding’ (n 306), ‘nutritional status’ (n 294) and ‘food supply’ (n 127) are included. Percentages for categories <5 % are not displayed (RCT, randomised controlled trial)

Of the papers under major MeSH term ‘vitamin A deficiency’, nineteen interventions were retrieved (26 % of the studies under this topic). All but four studies tested the effect of technological solutions in the form of vitamin A supplements (n 16) or fortified foods (n 2). Six of the studies aimed at preventing vitamin A deficiency. Of the six interventions retrieved under protein–energy malnutrition (8 % of the studies under this topic), all tested the use of special supplements and one was conducted with the aim of preventing undernutrition. One study compared supplements with local maize flour and another against better health care. Of the ten intervention studies on obesity (4 % of the studies under this topic), no study was conducted with the aim of preventing overweight or obesity. Six studies tested the use of physical activity or dietary interventions in overweight or obese and three evaluated specific drugs for weight loss or clinical outcomes. Of the forty-one interventions on breast-feeding (13 % of the studies under this topic), thirty-four aimed at promoting good breast-feeding practices. The large majority (n 30) of research on breast-feeding was carried out in the context of HIV transmission to children. A total of thirteen of the intervention studies used approaches delivered through existing local structures and were primarily counselling and education. Of the twelve interventions on nutritional status (4 % of the studies under this topic), eleven aimed at preventing deterioration of nutritional status. All of the interventions used technological approaches, in particular fortified beverages, drugs, bio-fortified foods and vitamin supplements. Seven interventions (6 % of the studies under this topic) were identified for food security. As these interventions were very heterogeneous in nature we were unable to compare them further.

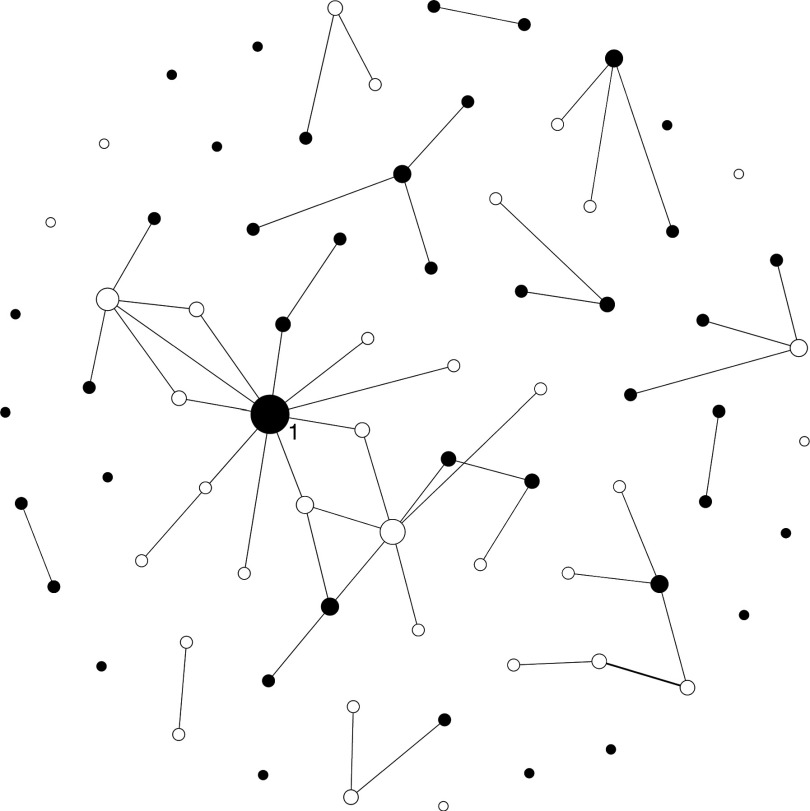

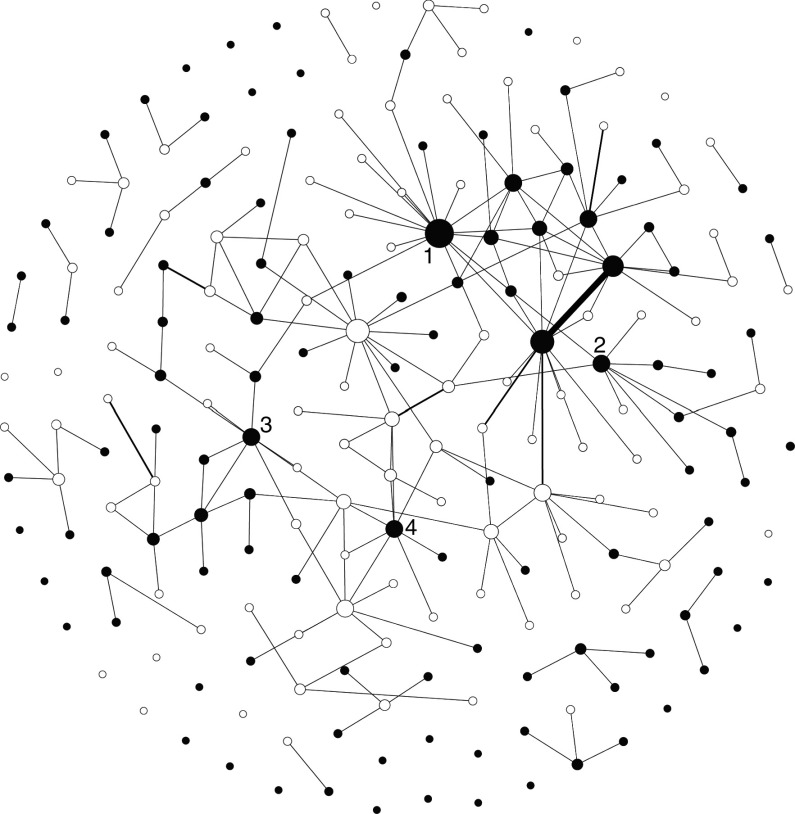

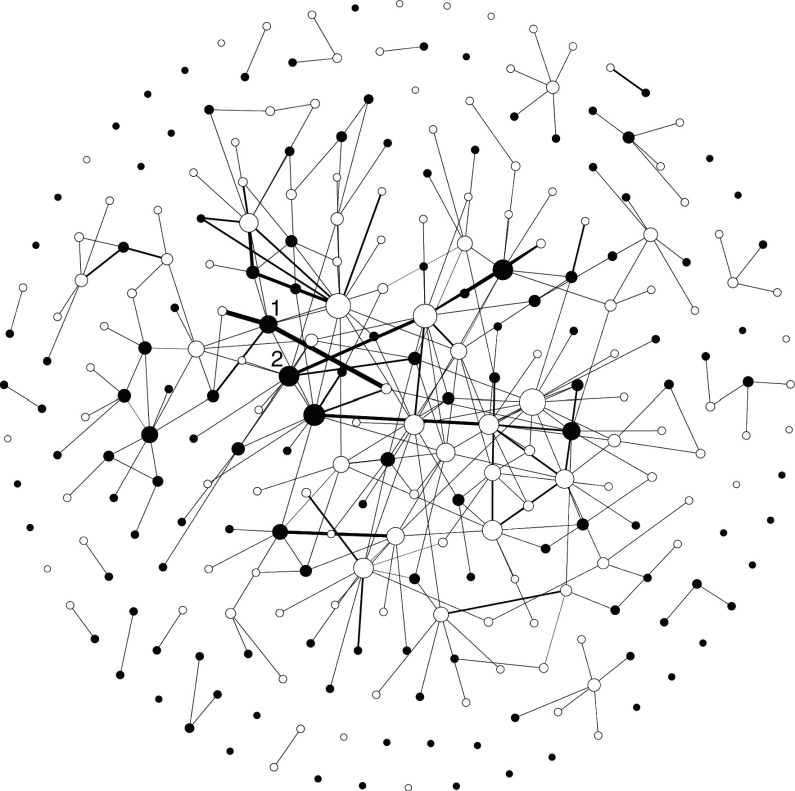

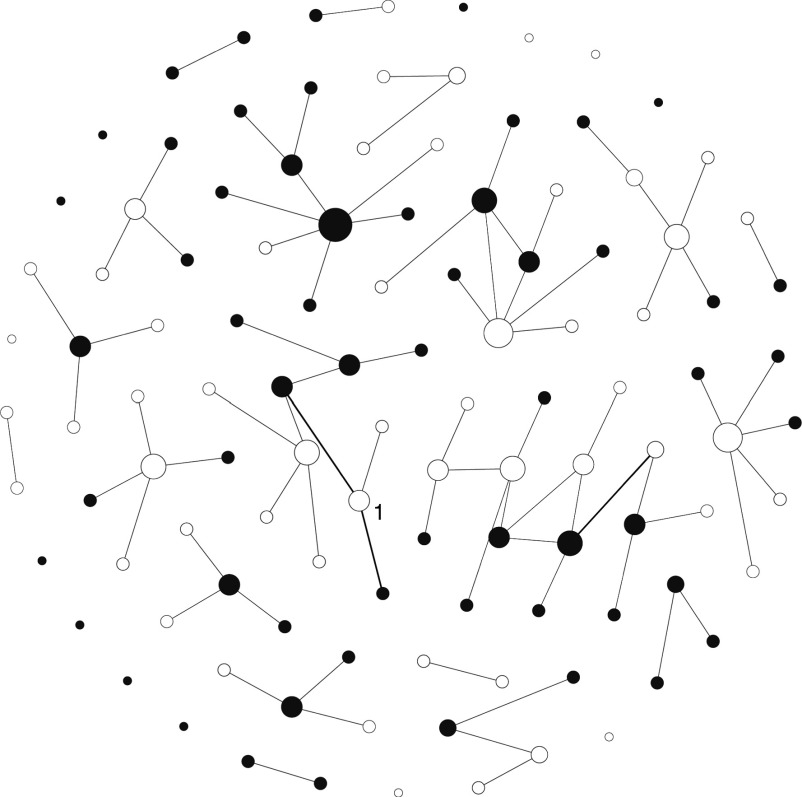

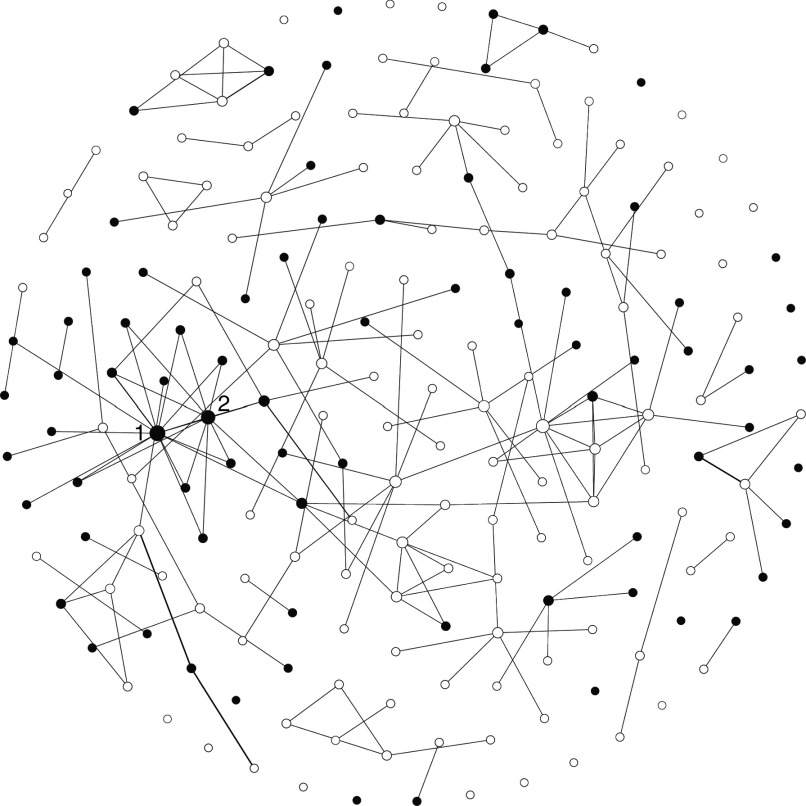

Figures 3–8 show that specific author affiliations took up central positions in the network of affiliations that published on the different nutritional topics. The majority of the most powerfully connected affiliations were situated outside Africa. Regarding the 10 % most powerful institutions, the share of those outside of Africa was 53 %, 70 %, 67 % and 80 % for papers on vitamin A deficiency, breast-feeding, nutritional status and food security, respectively. Only for papers on obesity and protein–energy malnutrition were there more African-based affiliations in the 10 % most powerful institutions compared with non-African ones. Overall, the most powerfully situated institutes in the networks were (in decreasing order) the North-West University in South Africa (β=10·3 for papers on nutritional status), Stellenbosch University in South Africa (β=8·3 for papers on food security), the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement in France (β=7·2 for papers on nutritional status), the University of Washington in the USA (β=6·8 for papers on vitamin A deficiency) and the University of Malawi (β=6·5 for papers on protein–energy malnutrition). Across the different nutritional topics analysed, the five most powerfully connected institutions from Africa were all based in South Africa: North-West University of Potchefstroom (β=10·3), Stellenbosch University (β=8·3), University of the Western Cape (β=6·4), Tygerberg Hospital (β=5·4) and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (β=4·8).

Fig. 4.

Network view of the first author affiliations of studies conducted in Africa on protein–energy malnutrition during the last decade. Affiliations (n 76) of the first author for papers (n 72) indexed as the major MeSH term ‘protein–energy malnutrition’ are included. The size of the node and connecting lines is relative to the number of connections. Affiliations based in Africa are in black, the ones outside Africa in white. 1=University of Malawi, Malawi

Fig. 5.

Network view of the first author affiliations of studies conducted in Africa on obesity during the last decade. Affiliations (n 215) of the first author for papers (n 224) indexed as the major MeSH term ‘obesity’ are included. The size of the node and connecting lines is relative to the number of connections. Affiliations based in Africa are in black, the ones outside Africa in white. 1=University of the Western Cape, South Africa; 2=University of Ibadan, Nigeria; 3=National Institute of Nutrition, Tunisia; 4=University of Yaoundé, Cameroon

Fig. 6.

Network view of the first author affiliations of studies conducted in Africa on breast-feeding during the last decade. Affiliations (n 266) of the first author for papers (n 306) indexed as the major MeSH term ‘breastfeeding’ are included. The size of the node and connecting lines is relative to the number of connections. Affiliations based in Africa are in black, the ones outside Africa in white. 1=University of Kazulu-Natal, South Africa; 2=Zvitambo project, Zimbabwe

Fig. 7.

Network view of the first author affiliations of studies conducted in Africa on nutritional status during the last decade. Affiliations (n 329) of the first author for papers (n 294) indexed as the major MeSH term ‘nutritional status’ are included. The size of the node and connecting lines is relative to the number of connections. Affiliations based in Africa are in black, the ones outside Africa in white. 1=North West University, South Africa; 2=Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, France; 3=Food and Nutrition Centre, Tanzania

Fig. 3.

Network view of the first author affiliations of studies conducted in Africa on vitamin A deficiency during the last decade. Affiliations (n 112) of the first author for papers (n 72) indexed as the major MeSH term ‘vitamin A deficiency’ are included. The size of the node and connecting lines is relative to the number of connections. Affiliations based in Africa are in black, the ones outside Africa in white. 1=University of Washington, USA

Fig. 8.

Network view of the first author affiliations of studies conducted in Africa on food security during the last decade. Affiliations (n 199) of the first author for papers (n 127) indexed as the major MeSH term ‘food supply’ are included. The size of the node and connecting lines is relative to the number of connections. Affiliations based in Africa are in black, the ones outside Africa in white. 1= Stellenbosch University, South Africa; 2= Tygerberg Hospital, South Africa

Given their dominance in the networks, we excluded South African research institutes from the analysis and assessed how this affected the findings. The exclusion did not modify the proportion of non-African based affiliations in the network considerably, except it meant that a higher proportion of research papers were led by non-African institutions. With 75 % of the papers published under an African affiliation, lead authorship in Africa exceeded that from non-African affiliations for research into protein–energy malnutrition only. The five most powerfully connected institutions (in decreasing order) were now the Tunisian National Institute of Nutrition, the University of Ibadan in Nigeria, the University of Yaoundé in Cameroon, The Zvitambo Project in Zimbabwe and the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the development of the evidence base for nutrition research in Africa is focused on treatment or technical solutions to nutritional problems. In parallel, the capacity of African research institutions to publish research conducted in Africa is tied to that of their peers in the North. Over the investigated decade, a considerable proportion of publications were dedicated to nutrition in Africa. Intervention studies were a minority of the studies conducted. Similar estimates for nutrition research published in low- and middle-income countries in the second half of 2005 were obtained( 16 ). Most of the studies assessed therapeutic strategies. In addition, only a few studies tested interventions on how distal determinants of nutritional status can be modified to improve nutritional status. These ‘nutrition-sensitive’ interventions have a significant potential to create a context for the prevention of malnutrition( 17 ).

Clearly, a substantial amount of this research is driven by organisations situated outside Africa. This observation was shared by a review of nutrition research in West Africa( 18 ) and in research output in 2005( 16 ). We acknowledge that this is in part attributable to training programmes outside Africa. Various African authors might have published their research in the context of training abroad. However, the network of authors’ affiliations of the papers indicates that root causes for this are to be found at a more structural level. Non-African academic institutions play a pivotal role in generating nutrition research in Africa. A significant amount of initiative and build-up of knowledge with regard to nutrition in Africa is concentrated in non-African institutions. In addition, cross-African linkages and networking of institutions within Africa seem secondary to networking with institutions based in the North. In line with a previous analysis( 19 ), our review shows how African research capacity in nutrition is tied to that of research institutions in the North. Clearly, international and intercontinental collaboration in research can leverage scientific knowledge and capacity in Africa and help generate answers to nutritional challenges. For such research collaboration to be considered a genuine partnership, it must rely on a balanced and complementary set of capacities( 20 ). International agreements now explicitly state how development efforts need to build equitable partnerships with recipient countries( 21 ). Similar initiatives for research are yet to be established. In our opinion, the establishment of a code of conduct for academic collaboration would be a useful start.

Gillespie et al. previously argued that the current political commitment to nutrition needs to translate into the build-up of capacity at national and regional level( 22 ). Our findings suggest that the collaboration between African research groups might not be used to its full potential and call for a new approach that stimulates networking within the region and nutrition research output from Africa, owned by African institutions. Such an approach, however, will require genuine support from stakeholders in the North( 23 ). African researchers previously indicated that non-African research institutions and donors are instrumental in determining the research agenda of the continent( 24 ).

We acknowledge a number of limitations of the present study. Assessing research evidence through academic publications entails an inherent bias by limiting the assessment to output from peer-reviewed journals only. However, as discussed earlier( 4 ), this approach remains a fairly objective way to assess research and the evidence base to date. Grey literature was not included in the review, as it is not centralised or indexed and mostly not peer-reviewed. Second, we retrieved research from MEDLINE and EMBASE, which index papers from most high-quality journals from Africa such as the South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Some journals that publish nutrition research from Africa (e.g. the African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development) without an impact factor were hence not included in the review. Using both the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, we are confident that we have captured the vast majority of high-impact journals in our review; that is, more than 90 % of the seventy-four journals in the subject category nutrition and dietetics in Web of Knowledge were included. We explored the type of studies and the authorship for a number of specific categories classified with a ‘major topic’ label in the databases. Studies that dealt with the topics but were labelled only with a usual MeSH or Emtree label for this subject were hence not included in this analysis. As a consequence, restricting the assessment to studies indexed under a major subheading implies that we have missed important studies. We are aware of studies that have tested preventive approaches for malnutrition in Africa( 25 ), using local resources( 26 ) or modifications of environmental factors such as agriculture( 27 ). These studies did not appear in our assessment, as they were not indexed under the categories reviewed. In general, however, we have no reason to believe that the application of major topics is done differently from the assignment of MeSH terms for the different topics reviewed. Although we have worked on a sub-sample of manuscripts within the topics, biased results are unlikely in this regard. Our search terms did not capture research on iodine, Fe or Zn, as these are classified under inorganic chemicals in the MeSH tree. Similarly, we have no reason to assume that our findings would be different for other topics of nutrition that are studied in similar ways to the ones reviewed. Lastly, we focused our analysis on co-authorship with the first author. We did not analyse co-authorship of authors who were not affiliated with the first author, as this would populate the graphs with networks that might have played a secondary role in the research conducted. Although this appropriately focuses the analysis on the key institutions driving the publication of the findings, it reduces the importance of the last author of the paper, who is often the coordinating author.

The present review shows that the evidence base in nutrition research is generally limited and focused on treatment and technical solutions to nutritional problems in Africa. Solutions for nutritional problems that use existing resources and delivery platforms, developed from high-quality studies and responsive to African needs and context, are urgently needed to respond effectively to the nutritional challenges of the continent. Our analysis shows how the potential for cross-African collaboration to identify, implement and publish nutrition research from Africa remains grossly underutilised. Adequate investment in African-led nutrition research is needed to provide a sustainable response to the nutritional challenges of Africa. This will require equitable academic collaboration between high-income countries and African research institutions, with the balance of power placed with African researchers.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The following members of the SUNRAY consortium provided guidance of the literature review: Waliou Amoussa, Karlien Smit, Yves Kameli, Paula San Pedro, Teresa Cavero, Joyce Kinabo and Fre Pepping. The authors especially extend their appreciation to the SUNRAY consortium member from Benin, Professor Romain Dossa, who unfortunately passed away during the project. They thank the SUNRAY Advisory Committee members Anna Taylor, Stuart Gillespie, Myriam Ait Aissa, Félicité Tchibindat and Mathurin Coffi Nago for their strategic input in this study. Financial support: The study was funded by the SUNRAY project (www.sunrayafrica.co.za). SUNRAY is a Coordination and Support Action of the European Union FP7 Africa-call under the Grant Agreement no. 266080. The funding source was not involved in the design of the study, management or interpretation of the data. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. C.L. is Deputy Editor of Public Health Nutrition. Authorship: C.L., D.R. and P.K. conceived the study. C.L., L.V.d.B., C.L. and P.K. extracted the data. C.L. analysed the data and drafted the initial manuscript. C.L., D.R., L.V.d.B., N.V.d.B., E.N., A.K., M.H., C.G.O. and P.K. contributed to the interpretation of the data and the write-up of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The protocol for the SUNRAY project, including this study, received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium on 8 June 2011 (no. 11 21 3 771).

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014002146.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ et al. (2012) Trends in mild, moderate, and severe stunting and underweight, and progress towards MDG 1 in 141 developing countries: a systematic analysis of population representative data. Lancet 380, 824–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abegunde DO, Mathers CD, Adam T et al. (2007) Chronic diseases 1 – the burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370, 1929–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Godfray HC, Beddington JR, Crute IR et al. (2010) Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mckee M, Stuckler D & Basu S (2012) Where there is no health research: what can be done to fill the global gaps in health research? PLoS Med 9, e1001209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rudan I, Kapiriri L, Tomlinson M et al. (2010) Evidence-based priority setting for health care and research: tools to support policy in maternal, neonatal, and child health in Africa. PLoS Med 7, e1000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE et al. (2008) What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 371, 417–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scaling Up Nutrition (2012) Homepage. http://scalingupnutrition.org (accessed June 2013).

- 8. Copenhagen Consensus (2012) Nobel Laureates: More should be spent on hunger, health. http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/Default.aspx?ID=1637 (accessed May 2012).

- 9. Nutrition for Growth (2013) Nutrition for Growth Commitments: Executive Summary (first version). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/205880/Nutrition-for-growth-commitments.pdf (accessed June 2013).

- 10. Funk ME & Reid CA (1983) Indexing consistency in medline. Bull Med Libr Assoc 71, 176–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abbasi A, Altmann JÃ & Hossain L (2011) Identifying the effects of co-authorship networks on the performance of scholars: a correlation and regression analysis of performance measures and social network analysis measures. J Informetrics 5, 594–607. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fruchterman TMJ & Reingold EM (1991) Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw Pract Exper 1, 1129–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bastian M (2009) Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. http://gephi.org/publications/gephi-bastian-feb09.pdf (accessed June 2013).

- 14. Bonacich P (1987) Power and centrality: a family of measures. Am J Sociol 1, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borgatti SP, Everett MG & Freeman LC (2002) Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morris SS, Cogill B & Uauy R (2008) Effective international action against undernutrition: why has it proven so difficult and what can be done to accelerate progress? Lancet 371, 608–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruel MT & Alderman H (2013) Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 382, 536–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aaron GJ, Wilson SE & Brown KH (2010) Bibliographic analysis of scientific research on selected topics in public health nutrition in West Africa: review of articles published from 1998 to 2008. Glob Public Health 5, Suppl. 1, S42–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hawkes C, Turner R & Waage J (2012) Current and planned research on agriculture for improved nutrition: a mapping and a gap analysis. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/pdf/outputs/misc_susag/LCIRAH_mapping_and_gap_analysis_21Aug12.pdf (accessed June 2013).

- 20. Rees M (2008) International collaboration is part of science’s DNA. Nature 456, 31. [Google Scholar]

- 21. 4th High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness (2011) Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation. 4th High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, Busan, Republic of Korea, 29 November–1 December 2011. http://effectivecooperation.org/files/OUTCOME_DOCUMENT_-_FINAL_EN2.pdf (accessed June 2013).

- 22. Gillespie S, Haddad L, Mannar V et al. (2013) The politics of reducing malnutrition: building commitment and accelerating progress. Lancet 382, 552–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lachat C, Nago E, Roberfroid D et al. (2014) Developing a sustainable nutrition research agenda in sub-Saharan Africa – findings from the SUNRAY project. PLoS Med 11, e1001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Royen K, Lachat C, Holdsworth M et al. (2013) How can the operating environment for nutrition research be improved in sub-saharan Africa? The views of African researchers. PLoS ONE 8, e66355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adu-Afarwuah S, Lartey A, Brown KH et al. (2007) Randomized comparison of 3 types of micronutrient supplements for home fortification of complementary foods in Ghana: effects on growth and motor development. Am J Clin Nutr 86, 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mamiro PS, Kolsteren PW, Van Camp JH et al. (2004) Processed complementary food does not improve growth of hemoglobin status of rural Tanzanian infants from 6–12 months of age in Kilosa District, Tanzania. J Nutr 134, 1084–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Faber M, Phungula MAS, Venter SL et al. (2002) Home gardens focusing on the production of yellow and dark-green leafy vegetables increase the serum retinol concentrations of 2–5-year-old children in South Africa. Am J Clin Nutr 76, 1048–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014002146.

click here to view supplementary material