Abstract

Objective

Community kitchens have been implemented by communities as a public health strategy to prevent food insecurity through reducing social isolation, improving food and cooking skills and empowering participants. The aim of the present paper was to investigate whether community kitchens can improve the social and nutritional health of participants and their families.

Design

A systematic review of the literature was conducted including searches of seven databases with no date limitations.

Setting

Community kitchens internationally.

Subjects

Participants of community kitchens across the world.

Results

Ten studies (eight qualitative studies, one mixed-method study and one cross-sectional study) were selected for inclusion. Evidence synthesis suggested that community kitchens may be an effective strategy to improve participants’ cooking skills, social interactions and nutritional intake. Community kitchens may also play a role in improving participants’ budgeting skills and address some concerns around food insecurity. Long-term solutions are required to address income-related food insecurity.

Conclusions

Community kitchens may improve social interactions and nutritional intake of participants and their families. More rigorous research methods, for both qualitative and quantitative studies, are required to effectively assess the impact of community kitchens on social and nutritional health in order to confidently recommend them as a strategy in evidence-based public health practice.

Keywords: Community kitchen, Social, Nutrition, Health, Food security

The term ‘community kitchens’ is used to describe community-focused and -initiated cooking-type programmes. While there is some discrepancy around the definition, community kitchens (CK) are known as providing an opportunity for a small group of people to meet regularly in order to prepare a meal( 1 ). They are generally initiated by community facilitators and are planned to be self-sustaining after an initial period of support( 2 ). CK focus on developing participant resilience for those experiencing food insecurity and social isolation, rather than creating and supporting a cycle of dependency on emergency food relief( 3 ). Their process aims to develop food skills and empower individuals rather than focus only on nutrition education or cooking skills( 2 ).

While most of the evaluation of CK has been based upon process rather than impact or outcome evaluation, the general consensus on the value of CK is positive and therefore such programmes have been well supported as a public health strategy( 3 – 9 ). It has been reported that CK develop cooking skills, improve nutrition and food security, and reduce participants’ social isolation( 9 , 10 ). However there is a need to critically evaluate the literature to determine the impact of CK and assess their effectiveness as a public health strategy.

The present systematic review of the literature (SRL) is the first to be conducted internationally. It aimed to determine the impact of CK on participants’ social skills, community connections and support, intake of nutritious food and food security. It also aimed to identify any existing research gaps and evaluate CK as a health promotion strategy.

Methods

Search methods

In April, 2011 seven databases (AGRICOLA, CINAHL Plus, Web of Science with conference proceedings, Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus and Sociological Abstracts) were searched without date restrictions, using search terms relating to the question: ‘What are the social health and nutritional benefits and impacts of community kitchens internationally?’. These search terms (Table 1) were grouped into three categories: (i) community kitchen; (ii) nutrition; and (iii) social. Synonyms and alternative words within each category were identified from current literature and a thesaurus. If a known study was not retrieved, search terms were expanded and relevant synonyms added. Only published studies were retrieved.

Table 1.

Categories and search terms used to explore the association between community kitchens and social health and nutrition

| Community kitchen | Nutrition | Social |

|---|---|---|

| Community kitchen* | Nutrition* | Social |

| Collective kitchen* | Diet* | Community |

| Collective cooking | Intake | |

| Cooking club* | Health* | |

| Food security | ||

| Food | ||

| Cooking |

*Truncation.

Study retrieval and analysis

One investigator retrieved published studies and exported the citations directly into EndNote® version X3. Titles and abstracts were assessed against the eligibility criteria (Table 2) and coded in EndNote with the reason for exclusion. For the purpose of the present review, CK were defined as community-based cooking programmes that aim to develop food skills, increase self-efficacy and reduce food insecurity and/or social isolation( 11 ). ‘A key feature of community kitchens that distinguishes them from other food assistance programs is their participatory format and potential to foster mutual support’( 11 ). Only studies pertaining to this definition were included. Of the remaining citations, complete publications were obtained, read thoroughly and re-evaluated against the eligibility criteria. Where there were aspects of doubt a second and third opinion was sought from other investigators.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Interventions | Editorials |

| Narrative and systematic reviews | Opinion papers |

| Randomised controlled trials | Not written in English |

| Cross-sectional studies | Cooking group classes |

| Cohort studies | Cooking demonstration classes |

| Case studies | Intervention not involving a CK |

| Evaluations | Outcome not relating to social skills, community connections and support or nutritional intake |

| Developed and developing countries | |

| Written in English | |

| Any population group | |

| Intervention involving a CK | |

| Outcome relating to social skills, community connections and support or nutritional intake |

CK, community kitchen.

The data of retained studies was extracted by one investigator, using the Cochrane guidelines for evidence-based review of health promotion interventions( 12 ) and the National Health and Medical Research Council body of evidence matrix( 13 ). Data extracted included title and author, affiliation and source of funds, study design, location or setting, intervention, sample size, population characteristics, length of follow-up, outcome measured, internal validity, applicability, sustainability and results. Qualitative studies were further classified as one of four types as described by Daly et al.( 14 ): (i) case studies (studies that focus on a single situation or case – level IV evidence); (ii) descriptive studies (studies that focus on a specific sample – level III evidence); (iii) conceptual studies that have a theoretical framework (level II evidence); or (iv) generalisable studies, which are guided by a comprehensive literature review, conceptual framework and diversified sample (level I evidence). The data were then summarised and then tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary table of studies included in the present systematic literature review and narrative description

| Study and reference | Study design | Sample size | Country | Population characteristics | Intervention | Data collection methods | Results/outcome | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crawford & Kalina (1997)( 20 ) | Mixed method | 24 participants | Canada | Low-income families living on or below the government's poverty line | Orientation included supermarket tour and a meeting where the group set rules for working together. They then progressed into monthly cooking sessions supported by menu planning and budgeting information. Meals prepared were shared among participants equally | Pre-programme and post-programme questionnaires | CK programme enhanced the ability of participants to provide themselves and their families with nutritious food. It created a healthy social environment and provided community support. The programme increased public and community awareness of food insecurity issues. There was a reduction in participants’ self-reported perceived barriers to participation and obtaining healthy food (except for transport) and an increase in the participants’ personal shopping skills pre- and post-programme | O |

| Engler-Stringer & Berenbaum (2006)( 4 ) | Conceptual | 37 CK leaders and participants; 9 key informants | Canada | Low-income single women, men, seniors, new immigrants, people with reduced mobility or mental disabilities and homeless or under-housed | Small groups of people pool resources and labour to produce large quantities of food but may also involve focus on social support, food and nutrition education and budgeting. Self-help in nature | Semi-participant observations and focused in-depth individual interviews | Participants reported excitement about cooking new foods, increased diversity when purchasing fruit and vegetables, increased variety of food in their diet in general and increased self-confidence related to cooking and nutrition. Participants also reported sharing new ideas and education with their family members. Increased social interaction among CK participants was also noted | P |

| Engler-Stringer & Berenbaum (2007) (A)( 6 ) | Conceptual | 37 CK leaders and participants; 9 key informants | Canada | Males and females | Small groups of people pool resources and labour to produce large quantities of food but may also involve focus on social support, food and nutrition education and budgeting. Self-help in nature | Semi-participant observations and focused in-depth individual interviews | Themes that emerged from participation in a CK included: building friendships, breaking social isolation, social and emotional support, increased enjoyment in cooking and eating, participation in community activities and sharing of community resources and information | P |

| Engler-Stringer & Berenbaum (2007) (B)( 5 ) | Conceptual | 63 CK groups. Data reported focused on subset of 16 participants | Canada | Low-income | Small groups of people pool resources and labour to produce large quantities of food but may also involve focus on social support, food and nutrition education and budgeting. Self-help in nature | Individual interviews | Participation in a CK led to the emergence of themes such as: increased food variety, stretching the budget, increased food resources, increased dignity by not having to access charitable resources and decreased psychological distress associated with food insecurity. Overall participants reported increased food security | P |

| Fano et al. (2004)( 19 ) | Cross-sectional | 82 participants | Canada | Prenatal women and food-insecure/low-income adults | CK programme aims to increase nutritional knowledge and encourage healthy eating. It provides the opportunity to apply practical skills such as budgeting and food preparation, promotes socialisation and social support, and encourages food safety | Individual questionnaire | 75 % of participants reported that they liked the social interactions and support offered by the CK. 31 % enjoyed the food prepared. 81 % of participants said they learnt to feed their families healthier foods. Reported consumption of at least five servings of fruit and vegetables daily increased from 29 % to 47 % after joining a CK programme. There was also an increase in reported meal planning from 25 % to 47 % after participation in CK. 36 % said they did not like the kitchen facility, 29 % reported disliking CK due to personality conflicts and language barriers in the group. 29 % reported not liking the food prepared | N |

| Lee et al. (2010)( 9 ) | Descriptive | 13 CK: 93 participants in total (63 CK participants, 20 facilitators, 10 project partners) | Australia | With a disability (46 %), Indigenous (6 %), English a second language (27 %), receiving pension or government benefits as sole income (62 %) | Small group programme led by a trained community facilitator. They cook a nutritious meal together regularly and learn about budgeting, menu planning and cooking skills in a social, community-based setting | Written survey, focus groups and structured telephone interviews | CK participation played a role in enhancing food and cooking skills, social skills and community participation. CK are able to reach and engage population subgroups that face the greatest health inequities | O |

| Marquis et al. (2001)( 10 ) | Descriptive | 14 participants | Canada | Low-income families with children | 20-week programme of cooking and instruction covering topics of feeding children, meal planning, budgeting, communication, self-esteem and team building. A small, participant-led cooking group. Programme is focused on identifying and addressing participants’ goals | Focus groups | All participants who completed the programme stated they had met their food- and nutrition-related goals and that attending a CK programme benefited both themselves and their families. Benefits of participation included increased socialisation and making new friends, having a break from children, learning to budget and save money, learning to shop wisely, learning to make new foods, increased cooking skills, eating less often at fast-food outlets and consuming healthier meals. Eight months since attending the first session, 50 % of participants were still cooking in CK groups | N |

| Mundel & Chapman (2010)( 2 ) | Conceptual | 10 in total; 5 project leaders and 5 project participants | Canada | Indigenous residents residing on traditional territory of the Musqueam Aboriginal Nation, Canada | Kitchen/garden project that grows food in a garden that is then prepared in kitchens by the community with the support of university students. Participants eat at the garden/kitchen and can take leftovers home for other meals | Semi-structured questionnaires and follow-up interviews | Empowerment and increased capacities were reported among participants. Participants reported: enjoying and benefiting from the sharing of skills, enhancing cooking skills, learning how to cook healthy inexpensive meals, enhancing food growing skills, having social interactions and support in a safe environment, and accessing important resources and community services | O |

| Spence & van Teijlingen (2005)( 18 ) | Descriptive | 6 participants | Scotland | Low-income parents | Community-based ‘cook and eat’ programme which includes an 8-week course on basic cooking, budgeting and food hygiene and demonstrates healthy meal preparation. Health promotion assistant leads the group but is directed by the needs of the participants who socialise as part of the programme | Face-to-face semi-structured interviews | Participants improved their cooking skills and gained opportunity to socialise and develop their food hygiene and budgeting skills. Participants reported positive dietary changes among their children, family members and themselves | N |

| Tarasuk & Reynolds (1999)( 1 ) | Descriptive | 10 CK observed, 6 CK selected for interviews. 14 participants (1 male and 13 female) and 6 facilitators | Canada | Low-income families | A range of programmes with the explicit goal of improving income-related food insecurity. Programmes include small groups of people cooking together and/or pooling resources and labour to produce large quantities of food and/or learning how to cook and eat together and socialising | Participant observations and in-depth interviews | CK participation is valued for providing social support, enhancing coping skills, increasing variety of food in one's diet, improving nutrition, and improving management of food spending dollars. CK participation may lead to involvement in other support services and groups. In severe and chronic poverty, CK programmes have limited potential to resolve food security, as they do not substantially alter the economic status of households | O |

CK, community kitchens.

Quality: P = positive, O = neutral, N = negative (refer to Table 4).

The quality of quantitative studies was evaluated as ‘positive’, ‘neutral’ or ‘negative’ using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies( 15 ) as suggested by the Cochrane guidelines( 12 ) (Table 4). The quality of qualitative studies was evaluated based on judgement by two authors as positive, neutral or negative using the Cochrane checklist( 12 ) (Table 4). Mixed-method studies were assessed against both qualitative and quantitative criteria and a judgement made on the overall quality based on both assessments as well as the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool( 16 ) (Table 4). Where there were aspects of doubt during the review process a third opinion was sought from investigators. After data extraction, data were analysed using a thematic analysis approach for synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence whereby the most common and important themes were extracted from the body of evidence summarised in results and outcomes of each study( 17 ) (Table 3).

Table 4.

Checklists used to assess quality of quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies

| Quantitative( 15 ) | Qualitative( 21 ) | Mixed methods( 16 ) |

|---|---|---|

| A. Selection bias: Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? | A. Method appropriate to research question | A. Is there a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques and/or data analysis procedures? For example, researchers describe the sampling and sample, data collection and data analysis for each method |

| B. Study design: If the study was randomised, was the method of randomisation described and was the method appropriate? If no go to C. | B. An explicit link to theory | B. Do the researchers describe and justify the mixed methods design? For example, authors describe rationale for each method and methods of implementation |

| C. Confounders: Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention? If yes, indicate the percentage of relevant confounders. | C. Clearly stated aims and objectives | C. Is there an integration of the qualitative and quantitative data? For example, there is evidence that the data gathered by both research methods were brought together |

| D. Blinding: Was the outcome assessor aware of the intervention or exposure of participants? Were study participants aware of the research question? | D. A clear description of context | |

| E. Data collection methods: Were data collection tools shown to be valid? Reliable? | E. A clear description of sample | |

| F. Withdrawals and drop-outs: Were withdrawals and drop-outs reported in terms of numbers and reasons per group? Indicate the percentage of participants completing the study. | F. A clear description of fieldwork methods | |

| G. Intervention integrity: What percentage of participants received the allocated intervention or exposure of interest? Was the consistency of the intervention measured? Is it likely that subjects received an unintended intervention that may have influenced the result? | G. Some validation of data analysis | |

| H. Analyses: Indicate the unit of allocation, analysis. Are statistical methods appropriate for the study design? Is the analysis performed by intervention allocation status rather than actual intervention received? | H. Inclusion of sufficient data to support interpretation | |

| Each section is rated as 1 (strong), 2 (moderate) or 3 (weak) and then the section scores are reviewed to make an overall judgement, where the study quality is strong (positive) if there are no weak ratings, moderate (neutral) if one weak rating or weak (negative) if two or more weak ratings( 15 ) | Positive, neutral or negative rating applied using judgement, after consideration of the above criteria( 21 ), in discussion between first and last authors | Each section (A to C above) rated as yes, no, not applicable or not included. Positive, neutral or negative rating applied using judgement, after consideration of the above criteria( 16 ), in discussion between first and last authors |

Results

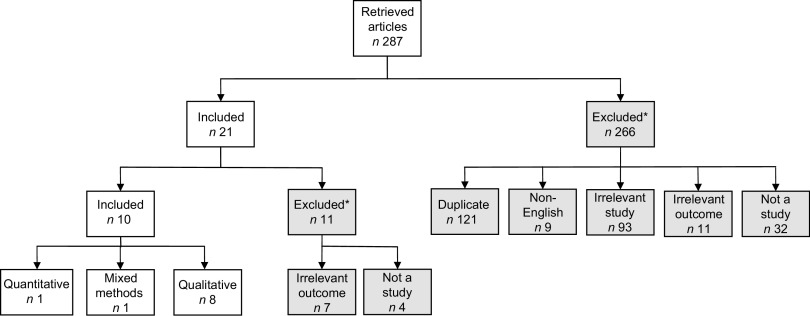

A total of 287 articles were retrieved from seven database searches: AGRICOLA (n 23), CINAHL Plus (n 20), Web of Science with conference proceedings (n 48), Ovid MEDLINE (n 29), PubMed (n 39), Scopus (n 112) and Sociological Abstracts (n 16). Studies that did not qualify for further review (n 266) included duplicates, studies not written in English, studies not relevant to the topic, studies that investigated CK but did not have a relevant outcome or intervention (i.e. a cooking group or demonstration classes, or nutrition education initiative) and publications not reporting a study (e.g. editorials). The full publications were sought for the remaining twenty-one studies. After review of each remaining study, eleven were excluded. Four were found not to be a study (i.e. narrative review or editorial) and seven had irrelevant outcomes (i.e. four reported demographics of CK participants only and three were not CK by definition, with two describing an education intervention and one describing a charitable communal meal programme; Fig. 1). The remaining ten publications included in the final review were predominantly qualitative studies (n 8)( 1 , 2 , 4 – 6 , 9 , 10 , 18 ), one cross-sectional study( 19 ) (level IV) and one mixed-methods study( 20 ). The qualitative studies consisted of four level III evidence descriptive studies and four level II conceptual studies. The one mixed-method study was classified as level IV evidence as the data were cross-sectional in nature, focused on process evaluation and there was no attempt to triangulate the different methodologies used in the study.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram representing studies included in the present systematic literature review and reasons for exclusion (*stems below the excluded box indicate reasons for exclusion)

Summary of included studies

Table 3 provides a summary of each individual publication included in the present review. Eight studies, ranging from six to ninety-three participants, investigated the effectiveness of CK as a health promotion strategy. Although data were extracted from ten manuscripts, the three papers by Engler-Stringer and Berenbaum( 4 – 6 ) used the same study to report three different aspects and findings. Various data collection methods were used to gather and collate information: participant observations, questionnaires (cross-sectional and pre/post CK programme), individual interviews (face-to-face, telephone, semi-structured, in-depth) and focus groups.

Four themes were identified from the analysis: (i) increase in reported intake of nutritious food and food security; (ii) increased self-reliance, dignity and engagement with community services; (iii) improved social skills and enhanced social support; and (iv) increased skills, confidence and enjoyment in cooking. Participants were generally from low-income families and communities with food security issues mostly in Canada, but also Australia and Scotland.

Increase in reported intake of nutritious food and food security

Studies reported participants of CK improved their intake of nutritious food( 20 ), had a greater variety in their intake of food( 1 , 4 , 5 ), increased the diversity of fruit and vegetables purchased( 4 ) and reported eating fast-food less often( 10 ). There were reported flow-on effects to other family members( 4 , 19 ). Fano et al.( 19 ) found that 81 % of participants fed their families healthier foods and the proportion of participants consuming at least five servings of fruit and vegetables daily increased from 29 % to 47 % after joining a CK programme. The study design and negative quality rating of that study( 19 ) should be taken into consideration when reviewing these findings. Two studies reported that further investigations are required to examine the ability of low-income populations to change their diet and enhance their nutritional intake( 9 , 18 ). CK were also reported to improve food security( 5 ). However, three studies suggested that the impact of CK to improve food security required further investigation( 5 , 9 , 18 ). Tarasuk and Reynolds( 1 ) suggested that CK programmes have limited capacity to resolve food insecurity issues, as they do not substantially alter the economic status of households.

Increased self-reliance and dignity and engagement with community

Studies also reported that CK improved access to community services and resources( 1 , 2 , 6 , 9 ) and increased participants’ dignity by not having to access charitable resources( 5 ).

Improved social skills and enhanced social support

Most studies reported improvements in social interactions, skills and/or support following involvement in CK( 1 , 2 , 4 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 18 , 20 ). Being in a safe environment( 2 ), breaking social isolation and having access to social and emotional support were more specific outcomes( 6 ). Making new friends( 10 ) may also be a benefit. Fano et al.'s( 19 ) cross-sectional study highlighted that social interactions and support were the main reasons participants joined a CK programme.

Increased skills, confidence and enjoyment in cooking

Other benefits participants reported gaining from CK programmes were increased enjoyment in cooking and eating( 2 , 4 , 6 ), improved shopping skills( 10 , 20 ), cooking skills and confidence( 2 , 4 , 9 , 10 , 18 ), and improved food budgeting skills( 1 , 5 , 10 , 18 ).

Discussion

Evidence from the present SRL suggests that CK may play an important role in enhancing cooking skills and improving social interactions and nutritional intake of participants( 2 , 9 , 10 ). While income-related food insecurity requires long-term solutions( 1 , 5 ), CK may increase community awareness of such issues and provide nutritious food and food skills to reduce food insecurity in the short term( 1 , 10 ). By decreasing the need to access charitable food sources, CK have shown to improve participants’ dignity( 5 ).

In further addressing the question ‘What are the social health and nutritional benefits and impacts of community kitchens internationally?’, the present review found that participants increased the diversity of their choices when purchasing fruit and vegetables( 4 ) and established a healthy social environment not only for themselves but also for their families( 20 ). Improved cooking skills, positive dietary changes and an opportunity to socialise were also identified as key benefits of CK participation( 18 ), although the cited descriptive study with a negative quality rating limits the ability to interpret these findings. These findings highlight that CK programmes have potential to positively impact social health and to provide nutritional benefits to participants who are socio-economically challenged.

The outcomes observed in the studies of the present review highlight the importance of the context and processes that have led to these positive and desirable outcomes. The self-help or voluntary and community-run nature of the cooking interventions appears to be an important element for success. For CK to result in improved social and nutritional health they need to be built on the definition of being participatory and promote social support( 11 ). Under these conditions they could be encouraged as a valuable health promotion strategy.

Despite the varied study locations (Canada, Scotland, Australia) the present review demonstrates that low-income groups face similar challenges, in relation to food and nutrition, across the developed world. Therefore the review supports that CK initiatives may be successfully implemented across other developed nations.

The sustainability of CK was extracted from all included manuscripts as part of the review process. While manuscripts inferred that community participation and self-help enhanced the sustainability of the programmes, only one study by Crawford and Kalina in 1997 specifically described the presence of a community worker to organise and facilitate the group as important for sustainability( 20 ). Although not specifically asked in the review, there were also other outcomes of CK, including access to employment( 10 ) and reorientation of health service programmes( 20 ) for example, which may be relevant for public health policy. The issue of sustainability is an important consideration to note when planning to implement a CK as a public health intervention or strategy.

Of the studies included in the present SRL, three of the studies were assessed to have a positive rating, four were neutral and three were negative (Table 3). The main reasons for not achieving a positive rating were the lack of data saturation and lack of theoretical underpinnings and methodological rigor in qualitative studies and not describing how subject refusals or errors were dealt with in quantitative studies. The lack of randomised controlled trials reduces the ability to interpret these findings into policy and practice in health promotion. The quality of the papers included in the review should be considered when making conclusions around their findings and as the basis for the development of public health policy.

Studies in the review employed a range of evaluation methods to assess the outcomes of CK. Although there is no claim that any of these methods is validated or necessarily most effective in such studies, the consistency of data collection methods used in qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method designs heightens credibility of the combined results and suggests that these methods may be most suitable in application to the CK environment and its participant groups.

For CK to be shown as an effective intervention in reducing the impact of and preventing food insecurity, more robust data are needed. While data collection and evaluation methods may be appropriate for local programmes, they do not enable comparisons to be made external to the CK programme. The studies that have been undertaken on CK have several weaknesses. These include the low number of studies found to have investigated the impact of CK and the lack of high-level evidence in quantitative and qualitative studies. Furthermore, recruitment for CK studies often occurred with existing participants or only within known low socio-economic communities, consequently selecting groups that may not represent all low-income, vulnerable and disadvantaged families. The present SRL acknowledges that there is a lack of higher-quality studies such as randomised controlled trials or conceptual qualitative studies that are sufficiently robust to show a causal effect. However, the authors recognise that studies such as randomised controlled trials which may produce stronger levels of evidence may be viewed as unethical to perform in vulnerable and disadvantaged groups where an untreated control group denies participants the intervention. Furthermore, blinding of randomised controlled trials with educational interventions is difficult and likely to introduce recruitment bias.

One of the main strengths of the present review is the vigorous and systematic nature of its methodology. Introduction of bias was minimised by using the same data extraction table and quality assessment checklist for each qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method study. Additionally due to the rigorous search of numerous databases and the inclusion of studies with evidence levels of IV and above, this SRL is very comprehensive. As study designs varied a meta-analysis could not be conducted; however the findings have important implications for public health practitioners and policy makers as the evidence suggests that CK may be an appropriate strategy to address food insecurity and its accompanying social exclusion.

Conclusions

The present SRL found that CK may provide benefits to the social and nutritional health of low-income participants and their families. It is evident that there is a lack of high-level evidence that would be required to establish causal links. The review identifies the need for rigorous research methods to attain a greater understanding and a more conclusive outcome on the actual effectiveness of CK. Despite the lack of long-term prospective studies, the present SRL suggests that CK may improve social, nutritional and food security issues of participants and their families who are often vulnerable and disadvantaged. This evidence has the potential to recommend that communities implement such public health strategies, to improve the nutritional health and well-being of vulnerable and disadvantaged populations.

Acknowledgements

The present SRL was supported by funding from Peninsula Health Community Health, health promotion program. Peninsula Health Community Health had no involvement in the study design, data collection, interpretation of results, or writing of the current report. The authors have no competing interests to declare. H.T. and C.P. were responsible for the design of the SRL. D.C.P. performed the original search and supported data extraction. M.I. completed data extraction, quality ratings and drafted the manuscript. C.P. and H.T. provided analytical support and contributed to the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance provided by Robin Ralston in the conduct of the SRL and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Tarasuk V & Reynolds R (1999) A qualitative study of community kitchens as a response to income-related food insecurity. Can J Diet Pract Res 60, 11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mundel E & Chapman G (2010) A decolonizing approach to health promotion in Canada: the case of the Urban Aboriginal Community kitchen garden project. Health Promot Int 25, 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Engler-Stringer R & Berenbaum S (2005) Collective kitchens in Canada: a review of the literature. Can J Diet Pract Res 66, 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engler-Stringer R & Berenbaum S (2006) Food and nutrition-related learning in collective kitchens in three Canadian cities. Can J Diet Pract Res 67, 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Engler-Stringer R & Berenbaum S (2007) Exploring food security with collective kitchens participants in three Canadian cities. Qual Health Res 17, 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Engler-Stringer R & Berenbaum S (2007) Exploring social support through collective kitchen participation in three Canadian cities. Can J Community Ment Health 26, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furber S, Quine S, Jackson J et al. (2010) The role of a community kitchen for clients in a socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhood. Health Promot J Aust 21, 143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirkpatrick S & Tarasuk V (2009) Food insecurity and participation in community food programs among low-income Toronto families. Can J Public Health 100, 135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee J, Palermo C, Bryce A et al. (2010) Process evaluation of community kitchens: results from two Victorian local government areas. Health Promot J Aust 21, 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marquis S, Thomson C & Murray A (2001) Assisting people with a low income: to start and maintain their own community kitchens. Can J Diet Pract Res 62, 130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tarasuk V (2001) A critical examination of community-based responses to household food insecurity in Canada. Health Educ Behav 28, 487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Armstrong R, Waters E, Jackson N et al. (2007) Guidelines for Systematic Reviews of Health Promotion and Public Health Interventions. Version 2. Melbourne: Melbourne University. [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence. Handbook Series on Preparing Clinical Practice Guidelines. Canberra: Biotext. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daly J, Willis K, Smalla R et al. (2007) A hierachy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. J Clin Epidemiol 60, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Effective Public Health Practice Project (2009) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Hamilton, ON: McMaster Evidence Review and Synthesis Centre.

- 16. Pluye P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F et al. (2009) A proposal for concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies include in systematic mixed studies reviews. Presented at 37th Annual Meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, Montreal, Canada, 16 November 2009.

- 17. Pope C, Mays N & Popay J (2007) Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative Health Evidence. A Guide to Methods. London: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spence F & van Teijlingen E (2005) A qualitative evaluation of community-based cooking classes in Northeast Scotland. Int J Health Promot Educ 43, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fano T, Tyminski S & Flynn A (2004) Evaluation of a collective kitchens program using the population health promotion model. Can J Diet Pract Res 65, 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crawford S & Kalina L (1997) Building food security through health promotion: community kitchens. Can J Diet Pract Res 58, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noyes J, Popay J, Pearson A et al. (2008) Qualitative research and Cochrane reviews. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [J Higgins and S Green, editors]. The Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]