Abstract

A cDNA (2855 nt) encoding a putative cytotoxic ribonuclease (rapLR1) related to the antitumor protein onconase was cloned from a library derived from the liver of gravid female amphibian Rana pipiens. The cDNA was mainly comprised (83%) of 3′ untranslated region (UTR). Secondary structure analysis predicted two unusual folding regions (UFRs) in the RNA 3′ UTR. Two of these regions (711–1442 and 1877–2130 nt) contained remarkable, stalk-like, stem–loop structures greater than 38 and 12 standard deviations more stable than by chance, respectively. Secondary structure modeling demonstrated similar structures in the 3′ UTRs of other species at low frequencies (0.01–0.3%). The size of the rapLR1 cDNA corresponded to the major hybridizing RNA cross-reactive with a genomic clone encoding onconase (3.6 kb). The transcript was found only in liver mRNA from female frogs. In contrast, immunoreactive onconase protein was detected only in oocytes. Deletion of the 3′ UTR facilitated the in vitro translation of the rapLR1 cDNA. Taken together these results suggest that these unusual UFRs may affect mRNA metabolism and/or translation.

INTRODUCTION

Onconase, an amphibian protein with antitumor activity (1–3), is a member of the RNase superfamily that also includes bovine pancreatic RNase A, bovine seminal RNase, angiogenin and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN). New biological functions such as angiogenesis and host defense activities associated with ribonucleolytic enzymes have elicited renewed interest in exploring their activities (reviewed in 4,5). In this regard, induced RNA damage by cytotoxic amphibian RNases triggers apoptotic death (6,7) that is non-mutagenic and not subject to repair mechanisms in contrast with standard DNA damaging chemotherapeutics. Moreover, apoptosis induced by onconase can be p53-independent (7), an important advantage in the treatment of human tumors that are refractory to DNA damaging agents due to non-functional p53 protein (reviewed in 8). These properties of onconase support its use as the catalytic component of targeted antibody-based reagents termed immunotoxins (9). Indeed, anti-CD22 antibody–onconase conjugates are potent and specific against disseminated human lymphoma cells (S.M.Rybak, unpublished data). These reasons enhance the significance of novel cancer therapies based on targeting RNA with recombinant cytotoxic RNases, which will benefit from knowledge of the genes, mRNAs and proteins involved.

Although the initial goal of this work was to clone a cytotoxic amphibian RNase for application to cancer therapy, novel findings emerged that also bear upon a wider area of biological significance. Herein we report: the first cDNA for a closely related homolog of onconase; the distribution of its mRNA and protein; an unusually large mRNA transcript relative to that described for any other pancreatic-type RNase; and a remarkable new RNA structure (stalk) in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The data is discussed with respect to the biological role of cytotoxic amphibian RNases and the possible biological significance of the 3′ UTR RNA stalk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Frogs

Northern grass frogs, Rana pipiens, were purchased from NASCO (Fort Atkinson, WI) and sacrificed on the same day they were received. Oocytes were isolated from gravid female frogs.

Northern blot analysis

Total cellular RNAs were isolated using RNA STAT-60 (TEL-TEST ‘B’. Inc., Friendwood, TX) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA was prepared using the Oligotex mRNA kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Poly(A) RNA was size fractionated on a 1% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde and blotted onto a Nitran nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) in 10× SSC overnight, rinsed in 2× SSC for 5 min and air dried. The RNA was cross linked to the membrane by exposure to UV light (Ultra-Lum, Paramount, CA) for 2 min. The RNA blot was hybridized at 42°C for 16–18 h with a 32P-labeled DNA probe prepared from ~30 ng of the Rana clone 9 genomic DNA insert (10) using an oligolabeling kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). After hybridization, the RNA blot was washed twice in 1× SSC, 1% SDS for 20 min at room temperature, and twice in 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS for 20 min at 42°C. The blot was exposed to X-ray film for 4 days. The molecular size of mRNA was estimated using 0.24–9.5 kb RNA molecular weight marker (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

RT–PCR was performed as described by Chen et al. (11). Briefly, PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 94°C for 5 min and then 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, for 30 cycles with an extension of 72°C for 5 min. The degenerate primers used were: 5′ primer [5′-AG(GA)GATGT(GT)GATTG(TC)GATAA(CT)ATCATG-3′] and 3′ primer [5′-AAA(GA)TG(CA)AC(AT)GG(TG)GC-CTG(GA)TT(CT)TCACA-3′]. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The PCR product obtained from liver was subcloned into the PCR3 vector by TA cloning (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA).

Western blot analysis

Cell extracts of various R.pipiens tissues were isolated as described previously (11). Proteins were electrophoretically separated on a 4–20% Tris–glycine gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) using 1× transfer buffer (Novagen Inc., Madison, WI) at 250 mA for 45 min. The membrane was probed with primary and secondary antibodies as described (11). The primary antibody reacted with onconase and was used at 1:1000 dilution. The secondary antibody was a Donkey anti-rabbit Ig conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham), and was used at 1:2500 dilution. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the ECL detection kit (Amersham).

Construction and screening of a R.pipiens liver cDNA library

Liver poly(A) RNA used for library construction was purified twice using a poly[A] pure kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The cDNA library was constructed using a ZAP-cDNA synthesis kit and Gigapack II gold packaging extracts according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The library contained ~1.5 × 106 p.f.u. from 5 µg of liver poly(A) RNA and was amplified once according to Stratagene’s protocol. The library titer after amplification was 9 × 109 p.f.u./ml. About 3 × 105 plaques were screened by using a 32P-labeled insert of Rana clone 9 following Stratagene’s procedure.

DNA sequencing

Clone 5a1b cDNA was digested with KpnI and HindIII to generate 3′ and 5′ protruding ends, and digested with exonuclease III to generate 5a1b deletion clones. Overlapping deletions were generated as described in Erase-a-Base system (Promega, Madison, WI). The sizes of DNA inserts from the deletion clones were estimated from an agarose gel, and the selected clones were sequenced using the T7 promoter primer. Clone 4a1b, the 5′ end of clone 3a1b and part of clone 5a1b were sequenced using T3, T7 and appropriate primers. All the sequencing reactions were performed using Sequenase version 2.0 kit (United States Biochemical Corp., Cleveland, OH) and [α-35S]dATP (>1000 Ci/mmol, Amersham). Both strands of clone 5a1b were sequenced.

In vitro translation

Clone 5a1b open reading frame (ORF) was synthesized by PCR using primers 5′-CGCGGATCCCAGAATGTTTCCAAAATTCTC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-CGCGGATCCCTTTCTAGCAATGTCCGACAC-3′ (reverse primer) containing a BamHI restriction site, with clone 5a1b as a template. The 5a1b ORF was ligated to a PCR3 vector (Invitrogen) to produce clone LP16. Clone LPFL1 was constructed by subcloning the entire insert of clone 5a1b into BamHI and EcoRI sites of a PCR3 vector. Both LP16 and LPFL1 sense transcripts are under the control of the T7 promoter. Translation products were prepared from LP16 and LPFL1 using the TNT T7 reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) with l-35S-methionine (1000 Ci/mmol, Amersham) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoprecipitation of translation products

Ten microliters of translation product and 1 µl of anti-onconase antiserum (1:1000) were added to 990 µl of L100 solution (100 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40). The mixture was rocked at room temperature for 1 h, and 50 µl of protein A Sepharose in L100 solution (v/v 1:1) was added and rocked at room temperature for 30 min. The mixture was microcentrifuged for 2 min, the supernatant was removed and the pellet was rinsed with 1 ml L100 solution three times. The pellet was suspended in 30 µl of sample buffer (150 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 6 mM EDTA, 6% w/v SDS, 20% glycerol, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% w/v bromophenol blue) and boiled for 5 min. The translation products were separated on a 14 or 16% Tris–glycine gel (Novex, San Diego, CA) and processed for fluorography followed by densitometric scanning using an Image Light Cabinet (Alpha Innotech Corp., San Jose, CA).

RNA structure analysis by computer

The RNA secondary structure of the 3′ UTR of clone 5a1b was computed using the program MFOLD (12,13). Two distinct folding domains were found near the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 2377 nt 3′ UTR. The two folding domains were evaluated by a statistical simulation using the program SEGFOLD (14), which assigned ‘significance’ scores to successive segments along the sequence. These significance scores are based on comparisons of the predicted thermodynamic stability of segments of real sequences with the stabilities of a large number of randomly permuted, corresponding segments. A second ‘stability’ score is similarly computed by comparing real segments at a given place with the average of all others in the sequence. Together, these scores are used to detect unusual folding regions (UFR). The program EFFOLD (15) was used, as was MFOLD to search for alternative folds of nearly similar stability. The program RNAMOT (16) was used with manually designed patterns to search for similar structural motifs in the UTR database (17) of the 3′ UTRs.

RESULTS

Expression pattern of onconase mRNA and protein in R.pipiens tissues

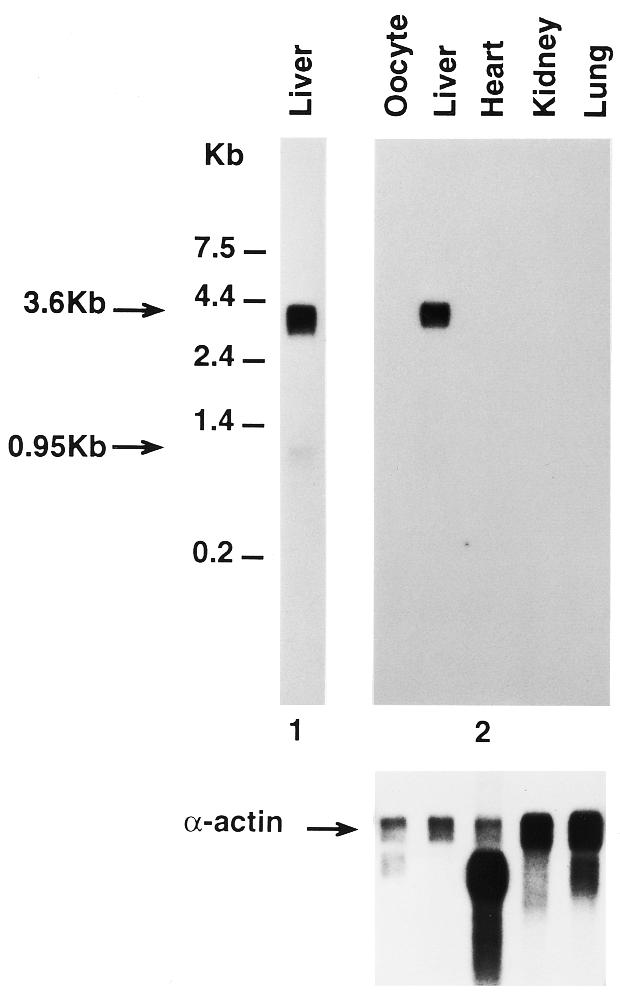

The DNA sequence (252 bp, Rana clone 9) corresponding to amino acid residues 16–98 of onconase was cloned by PCR amplification of R.pipiens genomic DNA (10). This was used to determine the distribution of onconase mRNA in various R.pipiens tissues. A 3.6 kb band was observed only in mRNA isolated from liver (Fig. 1, top right panel). Onconase mRNA was not detected in several other R.pipiens tissues tested including oocyte, heart, lung and kidney although the same blot probed with a 32P-labeled Xenopus laevis actin cDNA reacted with the mRNA in each of those samples (Fig. 1, bottom). Increasing the amount of mRNA and length of exposure revealed an additional minor band of about 950 bases (Fig. 1, top, lane 1). Although it is the expected size of an mRNA encoding a pancreatic type RNase (18) its relationship to onconase is not known since its low abundance precluded obtaining a clone corresponding to that size transcript.

Figure 1.

Northern blot analysis of female R.pipiens tissues. Poly(A) mRNAs (2 or 0.5 µg/lane, 1 and 2, respectively) isolated from different R.pipiens tissues were electrophoretically separated in a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel, blotted onto Nytran nylon membrane, and hybridized with a 32P-labeled 252 bp onconase cDNA fragment termed Rana clone 9. The blots were processed as described in Materials and Methods and exposed for 2 days (gel 2) and 4 days (gel 1), respectively. (Bottom) Probes were stripped from membranes and same RNA blot was hybridized with a X.laevis α-actin probe and exposed for 3 days.

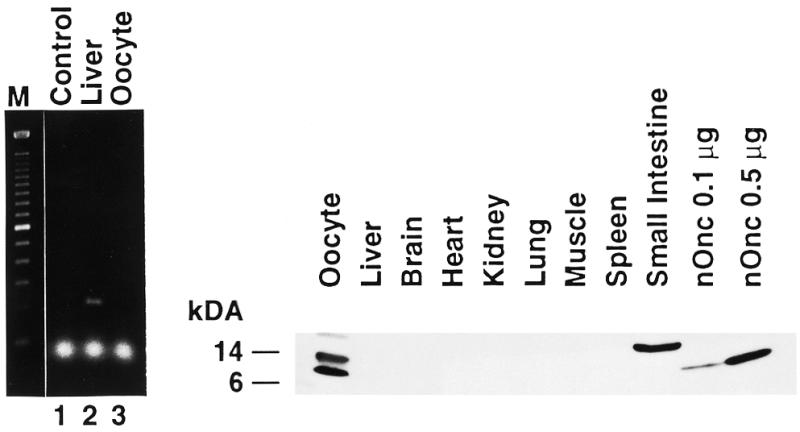

Since native onconase protein was originally identified in R.pipiens oocytes (19) and the size of the mRNA hybridizing to the onconase probe (3.6 kb) was unusually large for an amphibian pancreatic-type RNase (20) the identity of onconase mRNA in R.pipiens liver was confirmed using a second method. RT–PCR was performed with the degenerate primers used for cloning Rana clone 9 and total RNA isolated from R.pipiens liver and oocytes. Consistent with the northern blot analysis (Fig. 2, left), a band of the expected size (~250 bp) was present in RNA isolated from liver but not from oocytes. Furthermore, the PCR product was subcloned, sequenced and compared with the DNA sequence of Rana clone 9 (data not shown). The only difference at base 23 was an A→T transversion resulting in a conservative amino acid change from threonine to serine, that could have been due to a polymorphism or PCR error. In fact, polymorphic forms of onconase have been reported (21). Thus PCR and DNA sequence analysis confirms the presence of onconase mRNA in the liver of R.pipiens.

Figure 2.

(Left) Comparison of RT–PCR products generated from female R.pipiens liver and oocyte. Total RNA (0.4 µg) isolated from female R.pipiens liver and oocytes was used to produce first-strand cDNAs as described in Materials and Methods. PCR products were separated in a 1.5% agarose gel. M, Mr markers; lane 1, H2O; lane 2, PCR products from liver; lane 3, PCR products from oocyte. An expected size band of ~250 bp was observed in liver. (Right) Western blot analysis of female R.pipiens tissues. Protein extracts were isolated from various female R.pipiens tissues and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane as described in Materials and Methods. The tissue of origin is indicated above each lane; 0.1 and 0.5 µg of native onconase (nOnc) is shown for comparison in the last two lanes.

To examine the expression of onconase and/or related proteins, protein extracts were isolated from various R.pipiens tissues and analyzed by western blotting. A protein of the correct size [12 kDa, compare with native onconase (nOnc) in the two lanes furthest to the right as a control] was present in extracts from oocytes (Fig. 2, right). Other tissues, including liver, did not express a 12 kDa protein that reacted with the anti-onconase antibody. The two higher Mr proteins reacting with the onconase antibody could be related to onconase or other amphibian RNases since the antibody does cross react with bovine pancreatic RNase A as well as two human RNases, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and angiogenin (not shown). Taken together, the data show that onconase mRNA is expressed in R.pipiens liver but immunoreactive protein corresponding to the 12 kDa native protein was found only in oocytes.

Since mRNA was detected in female R.pipiens liver but not in oocytes, mRNA expression in male R.pipiens tissues was examined. Poly(A) RNAs were analyzed by northern blot analysis with the Rana clone 9 genomic DNA probe. Interestingly no hybridizing bands were detected in male R.pipiens liver or any other male tissues tested, implying that the expression of onconase is gender specific (data not shown).

Identification of cDNA clones from a R.pipiens liver cDNA library

A cDNA library was constructed using poly(A) RNA purified from R.pipiens liver. A total of three clones were identified by hybridization to Rana clone 9 (see diagram in Fig. 3A) after tertiary screening and were denoted 3a1b, 4a1b and 5a1b. Clones 3a1b and 5a1b contained inserts of ~2.8 kb and clone 4a1b contained an insert of ~360 bp. The DNA sequence of clone 5a1b is shown diagrammatically in Figure 3B. An ORF encoding a putative 127 amino acid protein was found at the 5′ end of clone 5a1b starting from base 97. Amino acids 1–23 are characteristic of a signal peptide with a charged amino acid within the first five amino acids, a stretch of at least nine hydrophobic amino acids to span the membrane, and ending with a cysteine (22). The putative signal peptide sequence is followed from amino acid 24–127 by a highly conserved but not identical amino acid sequence compared with onconase (19). Clones 3a1b and 4a1b were identical to clone 5a1b. The four amino acid differences between the ORF of clone 5a1b and onconase include amino acid residues 11 Leu↔Ile, 20 Asn↔Asp, 85 Thr↔Lys and 103 His↔Ser, respectively. With the exception of the conservative change at amino acid residue 11, all the other amino acid conversions are between polar and charged amino acid residues. Interestingly there were seven changes in nucleotides between the partial genomic DNA clone (corresponding to amino acid residues 16–98 of onconase) and rapLR1. Five nucleotide changes in the codon wobble position were silent resulting in the same amino acids at those positions. Two other nucleotide differences in this region of the DNA resulted in different amino acids at positions 20 and 85. Since the amino acid sequence of the putative ORF of clone 5a1b is different to onconase and it was cloned from R.pipiens liver, we have designated the putative protein of clone 5a1b ORF as R.pipiens liver RNase 1 (rapLR1). The changes in amino acid sequence cause substantial differences in both enzymatic and cytotoxic properties of expressed and purified rapLR1 compared to onconase (D.L.Newton, unpublished observations).

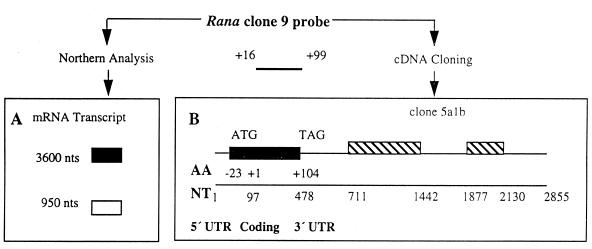

Figure 3.

(A) Rana clone 9 detected mRNA transcripts. Two mRNA transcripts were detected in mRNA isolated from R.pipiens liver with a 32P-labeled genomic DNA probe designated Rana clone 9. Significantly larger amounts of the 3600 nt transcript (dark gray box) hybridized to the Rana clone 9 DNA probe relative to the 950 nt transcript (light gray box, see Fig. 1). (B) Schematic diagram of clone 5a1b. The putative coding region (black bar) was detected in a R.pipiens liver cDNA library with the Rana clone 9 DNA probe. The coding region extends from nt 97 to 478 and includes a putative signal peptide (amino acid residues –23 to –1) and mature protein (amino acid residues +1 to +104). The two stalk-like stems encompass nt 711 to 1442 and 1877 to 2130, respectively (striped bars). AA, amino acid residues; NT, nucleotides.

Analysis and significance of the 3′ UTR of clone 5a1b

Two findings caused us to examine the nature of the 3′ UTR closely. First, the size of the major hybridizing band (~3600 bp, Fig. 1) far exceeds transcript sizes reported for other amphibian (20) and human pancreatic RNases (18,23–25). To our knowledge no other member of the RNase A superfamily is expressed by a mRNA containing at least 2377 nt of 3′ UTR. Second, no protein corresponding to the expected size for onconase was detected in the liver in spite of the abundance of the 3.6 kb transcript.

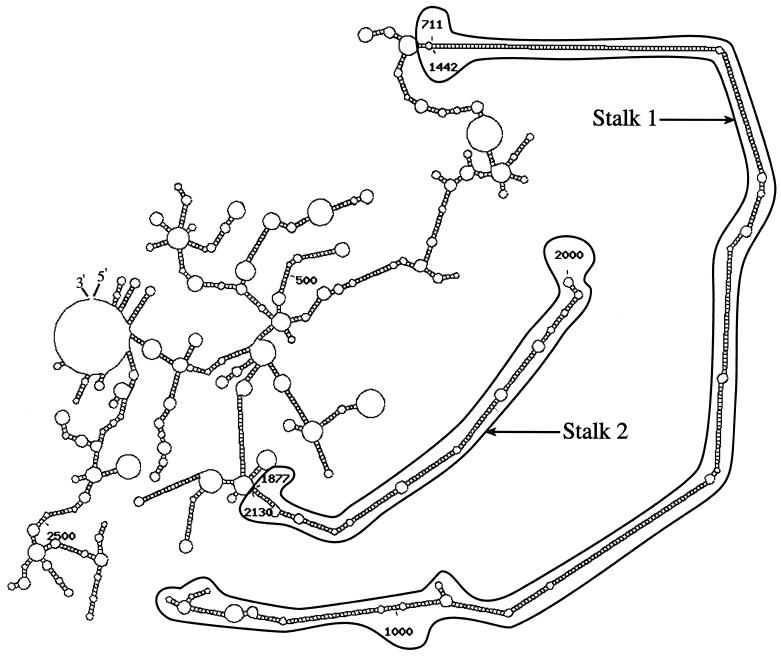

Examination of the sequence for motifs reported to be important in various aspects of RNA metabolism (26) revealed no unusually long direct repeats, no runs of bases other than a putative 3′ terminal poly(A) and no regions of unusual base dinucleotide or trinucleotide frequencies. A canonical poly(A) addition signal was not detected; nevertheless, a putative 20 nt poly(A) terminus is present. Although non-canonical signals implicated in cryptic poly(A) addition (27) are present, CATAAA occurs at position 2685 nt (170 nt from the 3′ end) and TATAAC at position 2288 nt (567 nt from the 3′ end), they could be too far from the 3′ end to be functional. Direct searches against the combined nucleic acids databases using the NCBI BLAST programs (28) found no significant similarities. Translation to amino acid sequences in all six reading frames and a search against the protein sequence databases using TBLASTX showed the expected close similarity of one reading frame to onconase and a number of other ribonucleases but no significant similarity to any other known proteins. In contrast to the lack of sequence motifs in the 3′ UTR sequence, scans using SEGFOLD showed two stable UFRs, indicated by large negative scores near the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 3′ UTR (Fig. 4). One predicted as a very long, stalk-like, stem–loop in the region of nt 711–1442, designated as Stalk 1, has five long, duplex stems of >25 bp connected by small internal and bulge loops (Fig. 5). The longest duplex stem includes 75 consecutive base pairs. A second shorter but still highly unusual region, Stalk 2, is at nt 1877–2130 (Fig. 5). Searches for alternative structures by EFFOLD (15) found no other significantly different structures. The multiple, short stems, loops and multi-branched loops of the non-stalk parts of the entire mRNA sequence of clone 5a1b are typical of many RNAs.

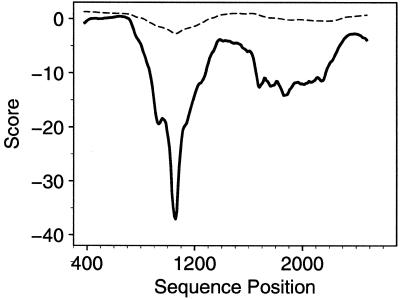

Figure 4.

Distributions of significance and stability scores in clone 5a1b mRNA sequence. The profile was produced by plotting the significance score (continuous lines) and stability scores (broken lines) of 714 nt segments against the position of the middle base in the window as it slides along the sequence. The window size is 714 nt. Scores have been averaged in successive, overlapping groups of nine positions for smoothing. The significance score [(E – Er/SDr] and the stability score [(E – Ew)/SDw) were computed as described in Materials and Methods using the Turner energy rules. E is the lowest free energy of formation for RNA folding of a RNA fragment of the window, where Er and SDr, respectively, are the mean and SD of E from its random permutations, and where Ew and SDw are the mean and SD of E resulting from sliding the window throughout the sequence. Using these parameters, the UFR detected in the 3′ portion is located at the region of 711–1442 nt corresponding to designated Stalk 1 (Fig. 5) and 1877–2130 (designated Stalk 2, Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Predicted structure of mRNA of clone 5a1b from program MFOLD drawn by the program Structure laboratory (50). The long UFRs are designated at Stalk 1 (nt 711–1442) and Stalk 2 (nt 1877–2130).

To determine whether similar structures existed in other 3′ UTRs extensive searches were performed in the UTRdb (17) database using RNAMOT (16) with patterns derived from the predicted structure of Stalk 1. According to the arbitrary groupings of the UTR database, we found 14 sequences in 6975 human, two in 2457 mammalian, four in 7633 rodent, seven in 5067 invertebrate, one in 8116 plant and one in 1154 fungal 3′ UTRs. Additionally, the 3499 sequences of the 3′ UTR in vertebrate mRNA other than the aforementioned groupings had only 11 sequences with similar long stem–loop structures.

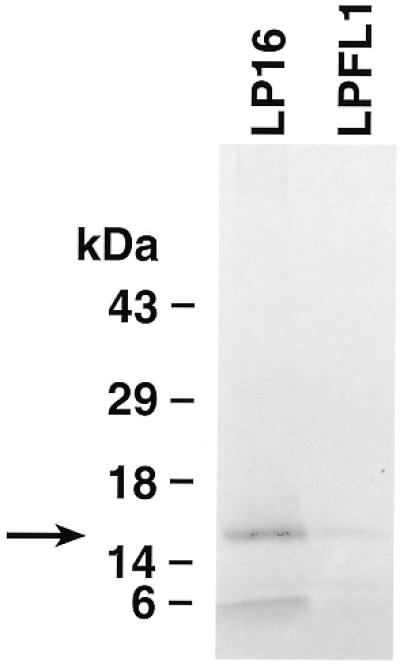

To begin to test a possible function of the 3′ UTR with its unusual stalk-like RNA structures, clone 5a1b DNA was subcloned into PCR3 vectors with (LPFL1) and without (LP16) the 3′ UTR. In vitro translation products were immunoprecipitated with anti-onconase antibodies and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Results shown in Figure 6 demonstrate that clone LP16 encodes a protein that migrates in a position close to the calculated molecular weight (14.5 kDa) of rapLR1. Although clone LPFL1 encodes a similar size band, it is 29-fold less intense by densitometry. In another experiment no detectable translation products were immunoprecipitated from the clone LPFL1 (contains full-length insert) or a control plasmid without any insert compared with a protein of the expected Mr from clone LP16 containing the truncated cDNA (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Comparison of translation products of ORF (LP16, RNA lacking the 3′ sequence) and full-length cDNA (LPFL1, RNA containing the 3′ sequence) of clone 5a1b. Translation products were produced as described in Materials and Methods and immunoprecipitated with anti-onconase antiserum. The labeled proteins were electrophoresed on a 14% Tris–glycine gel and processed for fluorography. The data are representative of two experiments.

DISCUSSION

Native onconase is isolated from R.pipiens oocytes (19) yet the only mRNA detected in the R.pipiens tissues examined by northern blot analysis appeared in the liver. This observation was confirmed by RT–PCR analysis. The sole PCR product generated was from liver RNA and its DNA sequence coded for a version of onconase that differed conservatively in the coding region by one amino acid. Recently, a similar mRNA tissue distribution was reported for a cytotoxic ribonuclease from Rana catesbeiana (20). The R.catesbeiana RNase as well as cytotoxic RNases from Rana japonica (29) and X.laevis (30) oocytes are sialic acid binding lectins that can agglutinate a large variety of tumor cells. These cytotoxic RNases are examples of soluble secreted lectins that are believed to bind to glycoproteins on or around the cells that release them. In that regard they are thought to play a role in shaping extracellular environments in both developing and adult tissues (31).

Interestingly, two transcripts hybridized to the Rana clone 9 genomic DNA probe (10) on a northern analysis of liver RNA. The transcript size of the minor hybridizing band (~950 bp) is consistent with the size of mRNAs reported for the R.catesbeiana RNase (20), mouse (32) and bovine (33) pancreatic RNases as well as for human pancreatic-type RNases (18,23–25). Although transcripts of 2 and 2.4 kb have been reported for human RNase 4 they were not cloned, sequenced and characterized (34).

The major hybridizing transcript reacting with the Rana clone 9 DNA probe was 3.6 kb. Two cDNA clones >2 kb encoding related onconase sequences were obtained and one of these, clone 5a1b, was completely sequenced. An ORF encoding a putative non-conservatively substituted onconase-like protein (rapLR1) begins at 97 nt of clone 5a1b with an ATG. It encompasses a putative signal peptide and the coding region of the mature protein containing 104 amino acid residues. The rest of the cDNA (2377 bp) consists of a 3′ UTR. Since clone 5a1b is smaller than the 3.6 kb hybridizing transcript it must represent a partial cDNA. The full-length 5′ and 3′ regions remain to be determined.

Cytotoxic RNases have been associated with yolk proteins in amphibians (35) and it is well known that other yolk proteins such as vitellogenin are synthesized in the liver of female frogs during the stage of oocyte formation. These proteins are then secreted into the blood and deposited in developing oocytes in a seasonal manner (reviewed in 36). Furthermore, the expression of both vitellogenin and rapLR1 is gender specific. Since vitellogenin mRNA is expressed in the liver and the protein is found in frog eggs it is similar to the rapLR1 mRNA and protein pattern described herein. The mechanism of vitellogenin protein synthesis may provide clues to interpreting the results found with rapLR1.

Natural populations of frogs have a seasonally defined reproductive cycle. During the prereproductive period (February–March) there is intense hormone-dependent vitellogenin synthesis in the liver that decreases during the reproductive period (April–May) (37). In fact, vitellogenin synthesis gradually declines and decreases to zero after hormonal induction (36). Our studies were performed with gravid female frogs bearing mature oocytes and were obtained (November–January) when the frog liver is non-responsive to hormonal induction of yolk proteins such as vitellogenin. By analogy, it is reasonable to assume that synthesis of other yolk proteins e.g. rapLR1 would also decrease to zero or at least to levels below the detection by western analysis. Moreover, no DNA synthesis is required for hormonal induction of vitellogenin and the rate of vitellogenin synthesis is dependent on the concentration of cytoplasmic mRNA (36). If synthesis of rapLR1 is similarly dependent on levels of cytoplasmic mRNA, the large amount of rapLR1 mRNA detected by northern analysis should have permitted detection of newly synthesized protein in the liver if it was actively undergoing translation. However, since oogenesis had ceased in R.pipiens at this point in their reproductive cycle, continued synthesis of yolk proteins would not be necessary. Taking all this into consideration we hypothesized that the major 3.6 kb mRNA could represent a storage form of mRNA not undergoing active translation. Thus a precursor pool of mRNA would be available for processing to the size of the mRNA transcript (<1000 kb) associated with all actively expressed pancreatic-type RNases (18,20,23–25,32,33) during the ensuing pre- and reproductive phases. Since the bulk of the cDNA that constituted the large RNA transcript consisted of 3′ UTR we examined it for features that would be compatible with post-transcriptional gene regulation.

The extremely large significance score of a stalk-like structure, 38 standard deviations (SD) more stable than random, implies a structural role for the region. Similar sized stem–loop RNA stalks were found in the 3′ UTRs of other species at low frequencies ranging from 0.01 to 0.3% in databases of 3′ UTRs of plants and vertebrates, respectively. For comparison, picornavirus internal ribosome entry sequences (IRES) (38), HIV tar (39) and RRE elements (40), cis-acting ribosome frameshift signals in retroviruses and ribosomes (41), bypass elements in bacteriophage T4 (42) and human ferritin mRNA iron-response elements (S.Y.Le and J.V.Maizel, unpublished data) have significance scores in the range of 3 to 6 SD and sizes ranging from 46 to 320 nt.

The high content of well formed duplex in the stalks could provide stability that could be useful for long-term mRNA storage by limiting access to nucleolytic enzymes because A-form duplexes have very narrow major grooves. In fact, temporal delays in translation are not unusual in developmental systems in both germ line and somatic cells where a particular mRNA is synthesized early in development, stored and translated later (43,44 and references therein). Additionally, 3′ inverted repeats in the 3′ UTR have been shown to stabilize RNA by protecting the termini from exonucleolytic degradation (45). Enhanced RNA stability would be compatible with the large amount of the clone 5a1b mRNA transcript in the liver. Nevertheless, there are interior bulge and hairpin loops analogous to the specific protein binding sites in known recognition elements. All these structural features could play a role in the developmental regulation of this mRNA.

It is well known that RNA structures are functionally involved in regulation of translational control and mRNA transport and localization (46–48). In this regard, a very significant distinct fold was also observed using our methods in the long 3′ UTR of Drosophila bicoid mRNA (bcd, GenBank accession no. X14458). Its significance score was 8 SD more stable than random. The UFR detected in bcd mRNA is known to coincide with a cis-acting signal in the 3′ UTR that directs both its transport from the nurse cells to the oocyte and its anterior localization within the oocyte (47,49). With regard to possible functionality of RNA stalks, preliminary results presented herein indicate that the 3′ UTR of clone 5a1b contains an element that may impede translation. A plasmid containing the entire cDNA including the 3′ UTR yields less translation product than a plasmid without the 3′ UTR. Possible mechanisms of translational repression could include masking by translational repressor proteins present in the rabbit reticulocyte lysate, interference with the translational apparatus or stearic hinderance (reviewed in 44). Based on the secondary structure model shown here, rational experiments can now be designed to test whether one or both of the RNA long stem-like stalks mediates the localization, translation and/or stability of mRNA. In conclusion, the coincidence of the remarkable structures in RNA with equally remarkable biological properties strongly implies that these properties may go together.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The technical support of Dale Ruby and assistance in the preparation of figures by John Owens is gratefully acknowledged. We very much appreciate our excellent administrative help and thank Ms Beverly A. Bales and Robin L. Reese. We are most grateful for the interest and support of Dr Edward A. Sausville. This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract no. NO1-CO-56000. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF165133

REFERENCES

- 1.Mikulski S.M., Viera,A., Darzynkiewicz,A. and Shogen,K. (1992) Br. J. Cancer, 66, 304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikulski S.M., Grossman,A.M., Carter,P.W., Shogen,K. and Costanzi,J.J. (1993) Int. J. Oncol., 3, 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rybak S.M., Pearson,J.W., Fogler,W.F., Volker,K., Spence,S.E., Newton,D.L., Mikulski,S.M., Ardelt,W., Riggs,C.W., Kung,H.F. and Longo,D.L. (1996) J. Natl Cancer Inst., 88, 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youle R.J., Newton,D.L., Wu,Y.N., Gadina,M. and Rybak,S.M. (1993) Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst., 10, 1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schein C.H. (1997) Nature Biotechnol., 15, 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deptala A., Halicka,H.D., Ardelt,B., Ardelt,W., Mikulski,S.M., Shogen,K. and Darzynkiewicz,Z. (1998) Int. J. Oncol., 13, 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iordanov M.S., Ryabinina,O.P., Wong,J., Dinh,T.H., Newton,D.L., Rybak,S.M. and Magun,B.E. (2000) Cancer Res., 60, 1983–1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen R. and Oren,M. (1997) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 7, 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rybak S.M. and Newton,D.L. (1999) In Chamow,S.M. and Ashkenazi,A. (eds), Antibody Fusion Proteins. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, pp. 53–110.

- 10.Newton D.L., Xue,Y., Boque,L., Wlodawer,A., Kung,H.F. and Rybak,S.M. (1997) Protein Eng., 10, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S.L., Maroulakou,I.G., Green,J.E., Romano-Spica,V., Modi,W., Lautenberger,J. and Bhat,N.K. (1996) Oncogene, 12, 741–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuker M. (1994) Methods Mol. Biol., 25, 267–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaeger J.A., Turner,D.H. and Zuker,M. (1989) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 7706–7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le S.Y., Chen,J.H. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1990) In Sarma,R.H. and Sarma,M.H. (eds), Structure and Methods: Human Genome Initiative and DNA Recombination. Adenine Press, Schenectady, NY, Vol. 1, pp. 127–136.

- 15.Le S.-Y., Chen,J.-H. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1993) Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 2173–2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laferrier A., Gautheret,D. and Cedergren,R. (1994) CABIOS, 10, 211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pesole G., Liuni,S., Grillo,G. and Saccone,C. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 192–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rybak S.M., Fett,J.W., Yao,Q.Z. and Vallee,B.L. (1987) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 146, 1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardelt W., Mikulski,S.M. and Shogen,K. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 266, 245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H.-C., Wang,S.-C., Leu,Y.-J., Lu,S.-C. and Liao,Y.-D. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 6395–6401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ardelt W., Lee,H.-S., Randolph,G., Viera,A., Mikulski,M. and Shogen,K. (1996) Characterization of a Natural Variant of Onconase [abstract] Fourth International Meeting on Ribonucleases, Groningen, The Netherlands.

- 22.Von Heijne G. (1983) Eur. J. Biochem., 133, 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg H.F., Tenen,D.G. and Ackerman,S.J. (1989) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 4460–4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenberg H.F., Ackerman,S.J. and Tenen,D.G. (1989) J. Exp. Med., 170, 163–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner H.L., Weiner,L.H. and Swain,J.L. (1987) Science, 237, 280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris D.R., Kakegawa,T., Kaspar,R.L. and White,M.W. (1993) Biochemistry, 32, 2931–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schutz T., Kairat,A.D. and Schroder,C.H. (1996) Virology, 223, 401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schaffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Ahank,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakakibara F., Kawauchi,H., Takayanagi,G. and Ise,H. (1979) Cancer Res., 39, 1347–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nitta K., Takayanagi,G. and Kawauchi,H. (1984) Chem. Pharm. Bull., 32, 2325–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barondes S.H. (1981) Annu. Rev. Biochem., 50, 207–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuller C., Nijssen,H.M.J., Kok,R. and Beintema,J.J. (1990) Mol. Biol. Evol., 7, 29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carsana A., Congalone,E., Palmieri,M., Libonati,M. and Furia,A. (1988) Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 5491–5502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg H.F. and Dyer,K.D. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 4290–4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao Y.D. and Wang,J.J. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem., 222, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahli W., Dawid,I.B., Ryffel,G.U. and Weber,R. (1981) Science, 212, 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carnevali O., Sabbieti,M.G., Mosconi,G. and Polzonetti-Magni,A.M. (1995) Mol. Cell Endocrinol., 114, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le S.Y., Chen,J.H. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1993) Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 2445–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le S.Y., Chen,J.H., Brown,M.J., Gonda,M.A. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1988) Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 5153–5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le S.Y., Malim,M.N., Cullen,B.R. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 1613–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le S.Y., Chen,J.H. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1989) Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 6143–6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le S.Y., Chen,J.H. and Maizel,J.V.,Jr (1993) Gene, 124, 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris D.R. (1997) mRNA Metabolism and Post-transcriptional Gene Regulation. Wiley-Liss, Inc., New York, NY, pp. 165–180.

- 44.Wickens M., Kimble,J. and Strickland,S. (1996) Translational Control. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 411–450.

- 45.Adams C.C. and Stern,D.B. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 6003–6010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curtis D., Lehmann,R. and Zamore,P.D. (1995) Cell, 81, 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macdonald P.M. and Kerr,K. (1997) RNA, 3, 1413–1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu L. and Benchimol,S. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 4117–4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macdonald P.M. and Struhl,G. (1988) Nature, 336, 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shapiro B.A. and Kasprzak,W. (1996) J. Mol. Graph., 14, 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]