Abstract

Objective:

In the early phase of severe acute brain injury (SABI), surrogate decision-makers must make treatment decisions in the face of prognostic uncertainty. Evidence-based strategies to communicate uncertainty and support decision-making are lacking. Our objective was to better understand surrogate experiences and needs during the period of active decision-making in SABI, to inform interventions to support SABI patients and families and improve clinician-surrogate communication.

Design:

We interviewed surrogate decision-makers during patients’ acute hospitalization for SABI, as part of a larger (n=222) prospective longitudinal cohort study of patients with SABI and their family members. Constructivist grounded theory informed data collection and analysis.

Setting:

One U.S. academic medical center.

Patients:

We iteratively collected and analyzed semi-structured interviews with 22 surrogates for 19 patients.

Measurements and Main Results:

Through several rounds of coding, interview notes, reflexive memos, and group discussion, we developed a thematic model describing the relationship between surrogate perspectives on decision-making and surrogate experiences of prognostic uncertainty. Patients ranged from 20–79 years of age (mean=55 years) and had primary diagnoses of stroke (n=13; 68%), traumatic brain injury (n=5; 26%) and anoxic brain injury after cardiac arrest (n=1; 5%). Patients were predominantly male (n=12; 63%), while surrogates were predominantly female (n=13; 68%). Two distinct perspectives on decision-making emerged: one group of surrogates felt a clear sense of agency around decision-making, while the other group reported a more passive role in decision-making, such that they did not even perceive there being a decision to make. Surrogates in both groups identified prognostic uncertainty as the central challenge in SABI, but they managed it differently. Only surrogates who felt they were actively deciding described time-limited trials as helpful.

Conclusions:

In this qualitative study, not all surrogate “decision-makers” viewed themselves as making decisions. Nearly all struggled with prognostic uncertainty. Our findings underline the need for longitudinal prognostic communication strategies in SABI targeted at surrogates’ current perspectives on decision-making.

Keywords: Prognosis, communication, clinical decision-making, acute brain injuries, neurology

Introduction

Severe acute brain injury (SABI) encompasses brain illnesses and injuries that occur suddenly, cause decreased consciousness in the acute period, and can result in dramatic, lifelong neurologic disability.1 Patients with SABI and their loved ones have unique palliative care needs due to several interrelated challenges. Prognosis in brain injury is complex and includes not only survival but also functional status and cognition;2 time to recovery after SABI is prolonged, and the extent of recovery typically uncertain, especially in the first few weeks.3,4 Additionally, patients generally cannot communicate their wishes in the acute period when initial decisions about life-sustaining therapy (LST) are made, leaving decision-making in the hands of patients’ loved ones, who assume the role of surrogate decision-makers (“surrogates”) while simultaneously grieving.5 These challenges illustrate the need to integrate palliative care into the management of patients with SABI.5–7 Doing so requires a deep understanding of the unique needs and experiences of patients’ surrogates, which only a few qualitative studies to date have explored.5,8

As part of a larger prospective study at one academic medical center, we interviewed surrogate decision-makers for patients with SABI during the acute hospitalization.9,10 A previous qualitative study of this cohort described the role of family presence at the bedside, comparing interviews occurring before and after COVID-19 visitation restrictions.11 The present study explored themes that emerged during an in-depth-analysis of all of the family interviews. Our primary objective was to describe surrogate experiences of decision-making and provider-surrogate communication in SABI. As a secondary objective, we aimed to construct an explanatory framework by which to understand these experiences.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Participants were identified from a larger single-center prospective longitudinal cohort study of patients with SABI (n=222) and their family members (n=278).9,10 Eligible patients had been admitted to the intensive care unit with a severe acute brain injury (SABI), defined as stroke, traumatic brain injury, or hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy after cardiac arrest, and had both a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 12 or less after hospital day 2 and a family member available. Given that the focus of this study was to better understand the experience in the intensive care unit at the time of active decision-making, we excluded patients for whom a decision had already been made to pursue comfort measures only.

Participants for this qualitative study were selected purposively using maximum variation sampling with the goal of ensuring that participants represented a range of patient characteristics that included age (range 20–79 years), disease category (stroke, traumatic brain injury, hypoxic-ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest) and patient-family relationship (spouse or partner, adult child, parent, or other). More participants were added throughout the study period until we reached thematic saturation.12,13 Because the aim of this study was to not only describe decision-making and communication needs in SABI, but also to construct a theory that might provide an explanatory framework by which to understand these experiences, we used a grounded theory approach, including iterative data collection and analyses.14 Because 4 of the 5 authors were physicians, the authors adopted a constructivist approach, in which the role of subjectivity in data gathering and analysis was acknowledged and researchers’ underlying assumptions were examined as part of data interpretation.15

All family members were interviewed once. Patients’ demographic and clinical information were abstracted from medical records, and surrogates provided demographic information via standardized questionnaires.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Participants provided written consent to participate in the larger longitudinal study (“SuPPOrT study”) and provided additional verbal consent to be interviewed. The SuPPOrTT study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board, STUDY00003393, date of initial approval 12/6/2017. Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Interview questions

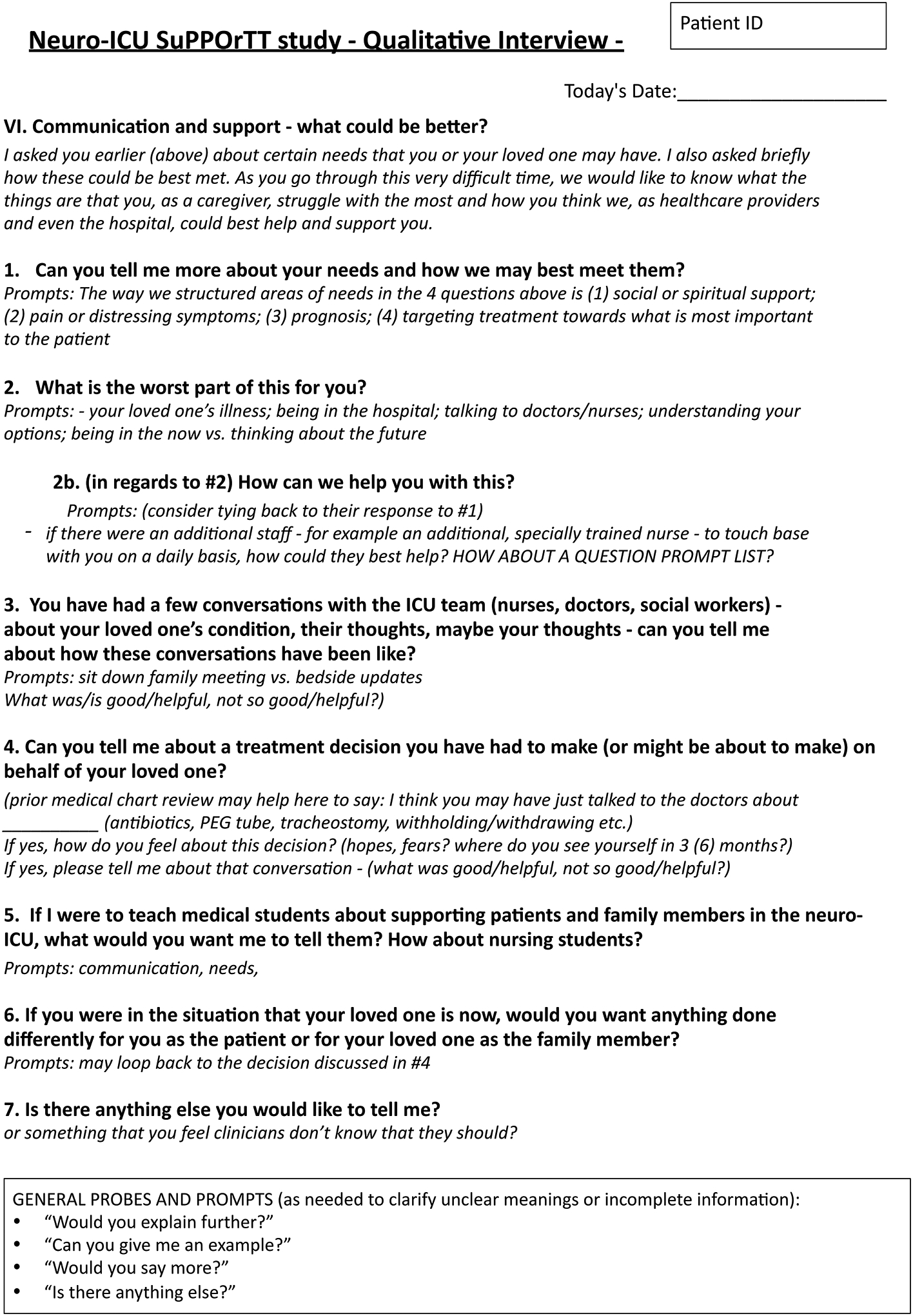

Interviews were semi-structured. The interviewers included a physician (C.J.C.) and PhD-trained behavioral scientist (M.H.). An interview guide was developed through literature search to focus on palliative and supportive care needs of patients and families specific to SABI and was further refined through expert guidance including input from a multidisciplinary group of Neurology and ICU nurses and physicians as well as qualitative researchers. Open-ended questions included one about the “worst part” of the SABI experience, as well as a question prompting families to share their experience with “a treatment decision” they had already made or were going to make. (Fig. 1). Digital recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and then de-identified.

Figure 1: Interview Guide.

Interview guide utilized to elicit experiences and communication needs of surrogate decision-makers in severe acute brain injury.

Qualitative analysis

Coding was completed in two rounds. First, two investigators (A.L.G., C.J.C.) read the transcripts and employed open coding to create tentative, content-driven categories that allowed us to identify themes in the data.14 Through discussion between the two researchers and re-readings of the complete data set, these coding categories were refined. We then used axial coding to draw connections between coding categories, developing final coding categories supported by individual quotations. This final coding scheme was applied by the two coders (A.L.G., C.J.C.) in consensus. Finally, the two investigators presented the coding scheme and themes that were supported by these codes to a larger multidisciplinary team (including R.R.V., R.A.E.). In order to support trustworthiness, this team reached consensus about the themes and used selective coding to develop a core theory around “perspectives on decision-making” in SABI. In order to address subjectivity, investigators completed interview notes and reflexive memos to assess the role of underlying assumptions in interpretation.15 In group discussions, the two neurologist authors (A.L.G., C.J.C.) and the non-neurologist authors (R.R.V, R.A.E, J.R.C.) reviewed reflexive memos and found slightly different interpretations of the role of prognostic uncertainty based on their professional experiences; discussion of these differences and identification of common themes led to clarification of the thematic model.

Results

Patients

We interviewed 22 surrogates for 19 patients (Table 1). The mean patient age was 55 years (range 20–79), and most were male (n=12; 63%). Patient diagnoses included stroke (all types, n=13), traumatic brain injury (n=5), and cardiac arrest (n=1).

Table 1:

Participant characteristics according to surrogate perspective on decision-making

| Participant characteristics | Total (n=19) | Choosing (n=9) | No choice (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Mean (range) | Mean (range) | Mean (range) |

| Patient Age (Years) | 55 (20–79) | 59 (26–74) | 52 (20–79) |

| Length of stay at first interview (Days) | 16 (4–50) | 20 (4–50) | 13 (4–28) |

| GCS on day of interview | 9.0 (4–12) | 8.6 (5–12) | 8.9 (4–12) |

| Total hospital length of stay (Days) | 35 (8–96) | 44 (17–96) | 26 (8–46) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Patient Gender (Female) | 7 (37) | 3 (33) | 4 (40) |

| Patient Race/ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic) | 15 (79) | 8 (89) | 7 (70) |

| Diagnosis subgroup | |||

| Stroke | 13 (68) | 7 (78) | 6 (60) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 5 (26) | 2 (22) | 3 (30) |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| Advance Care Planning documentation at time of admission (Yes) | 4 (21) | 2 (22) | 2 (20) |

| Alive at discharge | 15 (79) | 7 (78) | 8 (80) |

| Surrogates | Total (n=22) | Choosing (n=10) | No choice (n=12) |

| Mean (range) | Mean (range) | Mean (range) | |

| Surrogate Age (Years) | 51 (22–76) | 50 (31–72) | 55 (22–76) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Surrogate Gender (Female) | 13 (59) | 6 (60) | 7 (58) |

| relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse/Partner | 9 (41) | 5 (50) | 4 (33) |

| Adult child | 7 (32) | 3 (30) | 4 (33) |

| Parent | 5 (23) | 1 (10) | 4 (33) |

| Other | 1 (5) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

Surrogates

The mean surrogate age was 51 years (range 22–76). Most were female (n=13; 59%). Initial interviews were conducted an average of 16 days after hospital admission (range 4–50).

Findings

Organizing Perspectives

We identified the following two distinct perspectives on shared decision-making in SABI:

1). Choosing:

Surrogates with this perspective (n=10 surrogates, for 9 patients) described actively deliberating over important choices about continuation or withdrawal of LST. We labeled this perspective “Choosing” to reflect that these surrogates had a sense of agency in these decisions. For example:

“The worst part is worrying about her and trying to make decisions about what she would want and the likelihood of her getting back to a life that would be acceptable to her.”

2). No Choice:

The other perspective on decision-making, held by 12 surrogates for 10 patients, was that there were no choices for them to make. It was clear from the context of the interview that from the standpoint of medical professionals, these surrogates were facing treatment decisions, such as around artificial feeding or tracheostomy; however, these 12 surrogates did not see themselves as making decisions and instead described an automatic acceptance of LST. Surrogates in this group answered questions about medical decisions in one of three ways: 1) they were so committed to their hope for recovery that they did not even notice when they were making decisions to pursue LST; 2) prognostic uncertainty precluded them from making treatment decisions, such that LST felt like the only available choice; or 3) they so favored LST that they did not wish to even discuss goals of care or treatment options with physicians. We labeled their shared perspective “No choice.”

The first group of no choice surrogates held firmly to the possibility that their family member could recover; this strong hope or faith made it difficult to recognize or consider the option to withhold or withdraw LST:

Interviewer: …You have made some treatment choices?

Surrogate: Not yet.

Interviewer: …Did she have a feeding tube?

Surrogate: Yes…. And a trach.

Interviewer: …Those might have been sort of treatment choices? But it maybe didn’t feel like that to you?

Surrogate: Well, I don’t know. [Laughter] I didn’t think of it as treatment choices, but I guess it was.

Interviewer: Do you understand what sort of, what other options there are? I mean…either one would do the tracheostomy…or the alternative would be to focus on comfort and letting her go…

Surrogate: Letting her go has not been an issue, that has not been an item at all… Because I have hope and I have faith…I believe she’s going to get well. I believe she’s going to recover.

The second category of no choice surrogates said that uncertainty about the long-term outcomes of SABI precluded any ability to make treatment decisions in the acute setting. For example, this surrogate:

“We know exactly what [patient] of 12 days ago wanted… [but] we have yet to meet [patient] as he is now, or may be in the near future, or extended future for that matter. So, we don’t know who that person is yet. And how can you make an intelligent decision for somebody that you don’t know?”

A third group of no choice surrogates said that they had not had a formal discussion with providers about aligning treatment decisions with patients’ goals of care, and they were grateful for that. For example, this surrogate interviewed on day 19 of hospitalization:

Interviewer: You didn’t go into a different room to sit down and talk, sort of big picture, sort of, we often call it a family meeting?

Male: No. I think a lot of the social workers wanted to do that kind of thing, but I didn’t really want to have much part of it. All I had interest in is who can save my wife’s life. And I was possibly even rude… and I apologize for that. But that’s not what I need right now. I need somebody with a bag of oxygen.

What these no choice surrogates shared was a perception that they had not engaged in active deliberation over treatment decisions for their loved ones because they did not perceive themselves as actively making treatment decisions.

After separating the choosing and no choice surrogates, textual analysis did not identify any substantial differences between groups in their diagnosis, severity of illness or degree of uncertainty in prognosis. Demographics for the two groups are illustrated in Table 1.

Perspectives, decision making and communication

Within these two perspectives, we identified two themes that illustrated similarities and differences between the choosing and no choice surrogates’ experience of decision making and communication for their family member with SABI. These were: 1) the struggle with prognostic uncertainty and 2) enacting patient wishes.

The struggle with prognostic uncertainty

Whether prompted by our question “What is the worst part of this for you?” or unprompted, surrogates in both groups readily identified prognostic uncertainty as the greatest challenge they faced in SABI, but the impact of this prognostic uncertainty varied between the two groups. Surrogates with a choosing perspective identified uncertainty as the source of their struggle with making treatment choices. Surrogates with a no choice perspective saw prognostic uncertainty as an impediment to their ability to cope with and plan for what lay ahead. Representative quotations illustrating these two perspectives are represented in Table 2.

Table 2: “.

Worst part” of the experience of severe acute brain injury, with representative quotations

| “Choosing” perspective (Prognostic uncertainty makes choosing harder) |

“No Choice” perspective (Prognostic uncertainty makes it hard to cope and plan) |

|---|---|

| “The worst part for everybody… is…the fear of having her be in a state that was not acceptable to her and still being alive for a long time.” “The toughest part is…the unknowns… So it was really me and my daughters trying to think about what Mama said and what are her wishes. And at that point we were pretty scared, because we had no idea what the outcomes might be.” “Nobody can tell me how bad he will be… I cannot deliver that kind of [decision to limit treatment] because nobody’s clear.” |

“We’re not worried about her recovering process. It’s about how does my dad continue his working life, knowing that my mom may never be able to do what she was able to do before. And right now, that…is the biggest stress: Is how do I take my life as I’ve known it, what do I do moving forward?” “Being uncertain about, you know, the future… Like I was filling out FMLA paperwork, I’m like I have no idea what to put on this form for how long I’m going to need it.” “[The doctor] always ends everything, ‘But we just don’t know.’ So it’s like, you know, we’re pretty intelligent. We get the fact that…it’s a long road. But we don’t understand what this long road is…I know it’s not a concrete science… But it’s just, it’s kind of the back and forth, back and forth.” |

Regardless of group, participants talked about managing uncertainty with similar strategies: 1) avoiding thinking too far into the future; 2) trying to accept a less-than-ideal neurologic outcome; and 3) taking comfort in faith. However, only those surrogates with a choosing perspective described a “time-limited trial” as helpful (Table 3). A time-limited trial is an agreement between clinicians and a patient or family to use certain medical therapies for a defined period of time while monitoring the patient’s response; if the patient improves, the therapy usually continues, but if the patient deteriorates, the therapies are generally withdrawn.16 In our study, the surrogates with a choosing perspective felt that a time-limited trial would allow for greater clarity of prognosis, which would inform their decision-making. In contrast, surrogates with a no choice perspective tended to view LST as necessary unless the patient improved to the point of no longer needing them and therefore didn’t view time-limited trials as helpful.

Table 3:

Methods of managing uncertainty in severe acute brain injury and representative quotations

| Method of managing uncertainty | “Choosing” perspective | “No choice” perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Take one day at a time | “Early on, I mean, my brain was going everywhere, analyzing every different possible scenario, and I finally just calmed down and like, I just need to take it hour by hour and not try to look too far into the future, till we know that there is going to be a future or what that future might be.” | “If you start doing uncertainty, then you’re going to start analyzing to death and you’re going to run your nerves…okay? Just cross the bridge when you get there.” |

| Accept an imperfect outcome | “We know that the probability of him ever being 100% is ridiculous. But will he someday be 50%? I mean, even if I get 50% on that left side, I’m going to be a happy camper, you know?” | “All we can do his hope for the best. And then the best could be a whole new definition of what the best was. Our definition of okay is going to have to change a little bit.” |

| Take comfort in faith | “Yes. And I guess the underlying part of that is that we’re both Christians, and we know what our future is going to hold. So, holding onto that faith—and that’s what’s keeping me strong.” | “I don’t stress because I have faith in God and the doctors.” |

| Time-limited trial |

(The concept of TLT helps with choosing) “The game plan was to just see if he could regain the things that I mentioned within the next two to three months. But if we did not see an improvement and there was a decline or no improvement, then we was going to go with, you know, just making him comfortable in the rest of the time he has.” “Let’s just see what we can do for the next two weeks. Hope and pray for the best, but expect that with the damage that was done…that it probably is not going to work.” |

(TLT does not seem to be a concept) Interviewer: “You felt like [the doctors have] got to do [the tracheostomy] anyway for her comfort… And this ‘how long do we want to be in this uncertainty and see where she will go eventually’ was not really part of this decision for you?” Surrogate: “No.” “She has a feeding tube…she still needs speech therapy to determine if her swallowing and cognitive abilities are such that she can eat with her mouth… And then if it seems like she can eat enough to sustain her, then they’ll remove it..” |

Enacting patients’ wishes:

In contrast to the difficulties families described with prognostic uncertainty, respondents did not appear to struggle much with identifying their loved ones’ wishes. Regardless of group, some surrogates reported knowing the patient’s wishes while others did not. Among those who knew, regardless of group, some surrogates reported the patient as wanting to limit treatment if quality of life would be poor, while others described the patient as wanting all available treatments in hope of achieving recovery. Despite these shared perceptions across perspectives, the two groups offered different reflections on the implications of patients’ wishes. Surrogates in the choosing group attempted to apply patients’ wishes to medical decisions via substituted judgment. In the no choice group, surrogates seemed to consider patients’ wishes as irrelevant because prognostic uncertainty was so profound (Table 4).

Table 4:

Patient’s wishes in severe acute brain injury with representative quotations

| Comments about patient wishes | “Choosing” perspective | “No choice” perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of patient wishes | “If there’s hope at all, then we want them to do every single thing that we can do. And that’s what [patient] would want.” “She didn’t want to be… a vegetable… not being able to communicate, not being able to move… She wanted to be able to speak, read, hopefully use her hands. Some… comprehensible way of communicating her needs.” |

“We both said if it came to the point where we had a heart attack or a stroke and had to be put on life support systems, that…we did not want that prolonged.” Q: “How comfortable are you speaking for him about treatment choices? “ M: “I think I’m reasonably comfortable. I think I understand him pretty well.” |

| Role of patient wishes |

(Knowing what the patient would want guides my decisions) “He has always told all of us, ‘If I don’t have a quality of life, I do not want to live.’ So, you know, that’s in the back of your mind… … So is he going to be able to, you know, drive? Probably not, you know. Is he going to be able to … do the things that he loves? Maybe eventually. At least we gave him a chance to do that or to, you know?” “He did not want to be in a vegetative state. Meaning he did not want to be unconscious; he did not want to be in a coma, or, you know, things of that nature. …. So, knowing that—like I said, I’m trying to be his spokesperson and give him the best quality of life of the time that he does have.” |

(The patient’s wishes don’t apply to this situation) Surrogate: “You think you have had these what you view as intelligent, impacting conversations with each other and you know what you want to do, and even though it would be hard, we have made a promise to each other to carry out each other’s wishes. And then suddenly I’m put in a situation where…he’s unconscious, and he’s not responsive to me. And from what the care providers have told me, there is really no way to know about the prognosis with the brain. Sometimes you recover with limitations, sometimes you recover completely, and sometimes it never gets any better.” Interviewer: “You talked about everything, but not, but this situation doesn’t fit into what you have talked about?” Surrogate: “No, it does not fit… that’s the frustration.” “We had that kind of conversation [about wishes] before that accident happens…[But the current] situation is not clear… Nobody can tell me how bad he will be.” |

A model incorporating a “choosing” and “no choice” perspective

From the above data, we developed a thematic model (Supplemental Figure 1) in which surrogate decision-makers in SABI adopted two differing perspectives on decision-making. Some surrogates were actively deliberating around treatment decisions, while others were not. The difference in these perceived roles seemed to associate with a difference in how surrogates viewed and managed prognostic uncertainty, which was identified by both groups as a central challenge in SABI. Only those who felt as though they had actively deliberated their decision also felt that a “time-limited trial” of intensive medical care would have been helpful to clarify prognosis before making decisions.

Discussion

In this qualitative study during the acute phase of SABI, we found two distinct ways that family members experienced their role as surrogate decision-makers. Our findings have important implications for how clinicians communicate with surrogate decision-makers in SABI.

First, our results suggest that there may be a benefit to clinicians in assessing surrogates’ perspectives on decision-making – determining, for each surrogate, whether they view themselves as making decisions. Our findings build upon general critical care literature that has identified differences in the degree to which surrogates want to be involved in decision-making17,18 and the degree to which clinicians involve them,19 as well as population-level research in SABI that has identified surrogate predictors of LST selection.20 Collectively, this literature argues that different groups of surrogates need different approaches to goals-of-care discussions.21 Our findings suggest that these approaches need to account not only for surrogates’ preferred degree of control over decision-making, but also whether surrogates even perceive there being a decision to make. Those surrogates who, for varied reasons, do not perceive themselves as making decisions may not benefit in the same way from strategies like time-limited trials,16 decision-aids,22,23 or from repeated discussions of prognosis and treatment options, at least during the acute phase of care in the ICU. Instead, our data suggests that no choice surrogates might need prognostic communication to focus less on decision-making and more on the acknowledgement of uncertainty and its contribution to the surrogate’s coping, as well as on assurance of a longitudinal relationship.

Second, the exploration of a patient’s goals of care may also be more pertinent when surrogates are trying to make goal-concordant treatment decisions than it is for those surrogates who are focusing on hope and for whom prognostic uncertainty thwarts the integration of the patient’s goals. Many surrogates in our study readily described their knowledge or lack of knowledge of loved ones’ wishes for medical care, regardless of their perspectives on decision-making. A struggle with uncertainty about their loved one’s wishes was uncommon, whereas the struggle with prognostic uncertainty was common. Surrogates’ confidence in their assessment of patient wishes in our study may be surprising given previous reports on high rates of discordance between surrogate and patient assessments of wishes under hypothetical scenarios involving severely cognitively disabled states.24 Our finding that surrogates felt confident in their assessments of wishes, while challenging to interpret in a small qualitative study, suggests that for surrogates, the central struggle may be less about not knowing what the patient would want, and more about not knowing what the patient can eventually achieve.

Neither of these observations suggest abandoning current or future discussions about prognosis and goals of care for patients represented by “no choice” surrogates. Rather, our findings suggest that the framing of a time-limited trial may need to be modified for these surrogates in the acute setting of SABI. In the acute setting, our findings suggest that prognostication and decision-making be decoupled in family meetings for these surrogates, so that a clear prognostic range is delivered with acknowledgment of prognostic uncertainty (such as through the use of a best-case/worst-case/most-likely scenario framework25) without pressuring the surrogates to make decisions. In the post-acute setting or after a pertinent event (for example, a decline, complication or substantial improvement), it may be helpful for clinicians to hold another conversation re-evaluating not only prognosis and goals of care but also the surrogate’s decision-making perspective, since that perspective may have changed. For example, surrogates with a choosing perspective during the critical phase of SABI may later develop a no choice perspective if a patient makes a promising recovery. Similarly, surrogates with a no choice perspective during the critical phase of SABI might later consider choosing withdrawing or withholding LST depending on the patient’s condition. At each stage, our analysis indicates that surrogates need to hear the prognosis not only to facilitate decision-making, but also to help them reach acceptance, grieve, and make plans.26

Finally, regardless of decision-making, the interviews made it clear that prognostic uncertainty was hard to tolerate and that surrogates adopted a range of strategies to manage it. Surrogates in both groups found comfort in faith, affirming the need for medical providers to explore spiritual needs and offer spiritual support to families of patients with SABI.6,27,28 Surrogates in both groups also described a mindset of acceptance helpful, as well as a strategy of taking one day at a time; these coping strategies may point to approaches for future wellness interventions targeted at this population. Clinician communication strategies may also influence how surrogates conceptualize and develop a sense of agency in the face of prognostic uncertainty. One generally recommended method to communicate prognostic uncertainty is to bracket the range of possible outcomes (such as offering best-case and worst-case scenarios), offer the most likely outcome, and discuss the role of uncertainty.25–27,29,30 Surrogates’ sense of agency may also be influenced by whether physicians offer treatment recommendations that account for medical facts, professional experience, prognostic uncertainty and patients’ known beliefs and values. Although many physicians are reluctant to make treatment recommendations to patients,19,31,32 the American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society recommend that physicians offer to do so.33 Optimal strategies for communicating prognosis specific to SABI have not been established and are urgently needed.

Our study has important strengths and limitations. Strengths of this study are that we sampled surrogates for patients with a breadth of SABI conditions, interviewed them in real time and utilized a rigorous qualitative methodology. Limitations of this study include the small sample size and largely white male patient population; a larger number and a more diverse set of participants would be needed to identify sociodemographic, cultural, or clinical factors that may contribute to decision-making perspective. Second, we only spoke to family members of patients with SABI who were receiving LST at the time of the interview. While this decision was made to focus on surrogates who were actively making decisions around LST, surrogates who had already chosen to withdraw LST might have provided additional perspectives. Third, surrogates in this study were interviewed at different times during the hospitalization, which might have influenced their perspectives and introduced recall bias. Finally, while our qualitative analysis suggested that prognostic uncertainty was the main driver of some surrogates’ inability to make treatment decisions, other unidentified factors may have been at play, such as degree of prognostic uncertainty, clinician communication, or surrogate coping strategies. One possibility raised in a recent qualitative study of families who had consented for tracheostomy after SABI is that a perceived lack of choice might be a coping mechanism to avoid negative emotion around a difficult decision.34

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study suggests that eliciting surrogates’ perceived decision-making role may help inform a clinicians’ approach to communicating prognosis, discussing patients’ wishes, and providing targeted support to surrogates for patients with SABI. In our study, surrogates’ decision-making perspective emerged inductively from analysis of interview data. Research is needed to develop tools that may identify and incorporate surrogates’ perspectives on decision-making; evaluate effective, replicable strategies for communicating prognosis and providing support to surrogates with different perspectives on decision-making in SABI, particularly to those who do not perceive themselves as making a “choice”; and better understand how surrogates’ decision-making perspectives might change over time.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Perspectives on decision-making in severe acute brain injury

Surrogate decision-makers in severe acute brain injury adopt different perspectives on decision-making, which informs how they view and manage prognostic uncertainty.

Key Points.

Question: The objective of this qualitative study was to describe surrogates’ experiences of decision-making after severe acute brain injury (SABI), where surrogates face unique challenges related to prognostic uncertainty and patients’ inability to communicate.

Findings: Some surrogates described actively deliberating around major treatment decisions, while others, for varied reasons, did not perceive there being a decision to make. Surrogates in both groups identified prognostic uncertainty as the central challenge in SABI, but the two groups viewed and managed uncertainty differently.

Meaning: Our findings suggest possible strategies for communicating about prognostic uncertainty in SABI depending on surrogates’ current perspective on medical decision-making.

Acknowledgements

In memory of Mara Hobler, PhD, who conducted several of the qualitative interviews for this study.

Funding

This project was partially funded through Dr. Creutzfeldt’s K23 NS099421. Drs. Engelberg and Curtis receive funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Cambia Health Foundation.

Copyright Form Disclosure:

Drs. Goss, Curtis, and Creutzfeldt received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Engelberg received NIH funded grants unrelated to this work. Dr. Curtis’ institution received funding from the NIH and the Cambia Health Foundation. Dr. Creutzfeldt’s institution received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the NIH (K23 NS099421). Dr. Voumard has disclosed that she does not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Creutzfeldt CJ, Longstreth WT, Holloway RG. Predicting decline and survival in severe acute brain injury: the fourth trajectory. BMJ. Epub 2015 Aug 6.:h3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goss AL, Ge C, Crawford S, et al. Prognostic language in critical neurologic illness: a multi-center study. Epub 2022 Manuscript submitted for publication.

- 3.Finley Caulfield A, Gabler L, Lansberg MG, et al. Outcome prediction in mechanically ventilated neurologic patients by junior neurointensivists(CME). Neurology. 2010;74:1096–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geocadin RG, Buitrago MM, Torbey MT, Chandra-Strobos N, Williams MA, Kaplan PW. Neurologic prognosis and withdrawal of life support after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Neurology. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the American Academy of Neurology; 2006;67:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schutz REC, Coats HL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Creutzfeldt CJ. Is There Hope? Is She There? How Families and Clinicians Experience Severe Acute Brain Injury. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2017;20:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creutzfeldt CJ, Kluger BM, Holloway RG, editors. Neuropalliative Care: A Guide to Improving the Lives of Patients and Families Affected by Neurologic Disease [online]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. Accessed at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-93215-6. Accessed April 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG, Curtis JR. Palliative Care: A Core Competency for Stroke Neurologists. Stroke. 2015;46:2714–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn T, Moskowitz J, Khan MW, et al. What Families Need and Physicians Deliver: Contrasting Communication Preferences Between Surrogate Decision-Makers and Physicians During Outcome Prognostication in Critically Ill TBI Patients. Neurocrit Care. 2017;27:154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiker WA, Rutz Voumard R, Andrews LIB, et al. Assessment of Discordance Between Physicians and Family Members Regarding Prognosis in Patients With Severe Acute Brain Injury. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:e2128991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutz Voumard R, Kiker WA, Dugger KM, et al. Adapting to a New Normal After Severe Acute Brain Injury: An Observational Cohort Using a Sequential Explanatory Design. Critical Care Medicine. 2021;49:1322–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creutzfeldt CJ, Schutz REC, Zahuranec DB, Lutz BJ, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Family Presence for Patients with Severe Acute Brain Injury and the Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Palliative Medicine. Epub 2020 Nov 17.:jpm.2020.0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods [online serial]. 2006;18. Accessed at: https://journals-sagepub-com.ucsf.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1177/1525822X05279903. Accessed November 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Reilly M, Parker N. Unsatisfactory Saturation: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2012;13:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creswell JW, Creswell Báez J. 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher. Second edition. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 7th Ed. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quill TE, Holloway R. Time-Limited Trials Near the End of Life. JAMA. American Medical Association; 2011;306:1483–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson SK, Bautista CA, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, White DB. An empirical study of surrogates’ preferred level of control over value-laden life support decisions in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:915–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White DB, Malvar G, Karr J, Lo B, Curtis JR. Expanding the paradigm of the physician’s role in surrogate decision-making: An empirically derived framework*. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd E, Lo B, Evans L, et al. “It’s not just what the doctor tells me:” Factors that influence surrogate decision-makers’ perceptions of prognosis*. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38:1270–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg A, Soto AL, Knies AK, et al. Predictors of Surrogate Decision Makers Selecting Life-Sustaining Therapy for Severe Acute Brain Injury Patients: An Analysis of US Population Survey Data. Neurocrit Care [online serial]. Epub 2021 Feb 1. Accessed at: 10.1007/s12028-021-01200-9. Accessed July 12, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2327–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muehlschlegel S, Goostrey K, Flahive J, Zhang Q, Pach JJ, Hwang DY. A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial of a Goals-of-Care Decision Aid for Surrogates of Severe Acute Brain Injury Patients. Neurology. 2022;99:e1446–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR. Valuing the Outcomes of Treatment: Do Patients and Their Caregivers Agree? Arch Intern Med. American Medical Association; 2003;163:2073–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruser JM, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, et al. “Best Case/Worst Case”: Qualitative Evaluation of a Novel Communication Tool for Difficult in-the-Moment Surgical Decisions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63:1805–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpkin AL, Armstrong KA. Communicating Uncertainty: a Narrative Review and Framework for Future Research. J GEN INTERN MED. 2019;34:2586–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holloway RG, Benesch CG, Burgin WS, Zentner JB. Prognosis and Decision Making in Severe Stroke. JAMA. American Medical Association; 2005;294:725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG, Walker M. Symptomatic and palliative care for stroke survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holloway RG, Gramling R, Kelly AG. Estimating and communicating prognosis in advanced neurologic disease. Neurology. 2013;80:764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Palliative Care in Neurology. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2017;92:1592–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahgal S, Yande A, Thompson BB, et al. Surrogate Satisfaction with Decision Making after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheunemann LP, Ernecoff NC, Buddadhumaruk P, et al. Clinician-Family Communication About Patients’ Values and Preferences in Intensive Care Units. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, Danis M, White DB. Shared Decision-Making in Intensive Care Units. Executive Summary of the American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. American Thoracic Society - AJRCCM; 2016;193:1334–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lou W, Granstein JH, Wabl R, Singh A, Wahlster S, Creutzfeldt CJ. Taking a Chance to Recover: Families Look Back on the Decision to Pursue Tracheostomy After Severe Acute Brain Injury. Neurocritical Care [online serial]. 2022;36. Accessed at: https://link.springer.com/epdf/10.1007/s12028-021-01335-9. Accessed May 9, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Perspectives on decision-making in severe acute brain injury

Surrogate decision-makers in severe acute brain injury adopt different perspectives on decision-making, which informs how they view and manage prognostic uncertainty.