Abstract

Here, we provide a brief overview of the approaches and strategies underlying bacteria-based cancer immunotherapy (BCiT). We also describe and summarize research in the field of synthetic biology, which aims to regulate bacterial growth and gene expression for immunotherapeutic use. Finally, we discuss the current clinical status and limitations of BCiT.

Subject terms: Cancer, Cancer microenvironment, Cancer prevention

The relationship between cancer and human microbiota has existed since ancient times. However, bacteria-based cancer immunotherapy (BCiT) was not attempted until the 19th century, when William Coley used live or heat-killed Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens to treat patients with inoperable cancer. This strategy led to > 10-year disease-free survival in about 30% of the patients1,2. Several genera of facultative and obligate anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium, Bifidobacterium, Listeria, Salmonella, Escherichia, Proteus, and Lactobacillus, have been extensively studied because of their ability to specifically target and inhibit tumor growth3. Some of these bacterial species have been engineered to deliver drug payloads and improve their safety and targeting efficiency4–6. For example, several attenuated Salmonella strains were generated via deletion of major virulence genes (e.g., S. typhimurium defective in guanosine 5’-diphosphate-3’-diphosphate synthesis [the ∆ppGpp strain]), and showed that these bacteria localized to the tumor and reached over 1 × 1010 colony-forming units (CFU)/g in tumor tissue 3 days after intravenous injection; moreover, the tumor-to-normal tissue bacterial ratio exceeded 10,000:14,7,8.

Bacteria have distinct ways of targeting and penetrating tumors, using unique properties such as their inherent motility, chemotaxis, and the ability to induce inflammatory reactions and evade the immune system3. Once colonized the tumor, bacteria expand within the immune-privileged tumor microenvironment (TME) to induce antitumor immunity by increasing immune surveillance and decreasing immunosuppression3,9. However, bacteria alone cannot eliminate tumors completely; thus the prospect of generating bacteria carrying therapeutic payloads (drugs) may hold great promise in cancer treatment6.

As a tumor-targeting drug carrier, bacteria can be genetically engineered to produce potent therapeutic payloads such as cytotoxic agents, immunomodulators, cytokines, prodrug converting enzymes, small interfering RNAs, and nanobodies4. These payloads and the bacteria work together to reprogram the TME by interacting with tumor cells, immune cells, and other TME components. This reprogramming is accomplished through the infiltration and activation of immune cells, as well as the production of cytokines and chemokines. Thus, the overall antitumor effect of the bacteria themselves is increased4.

Synthetic biology tools for genetic engineering enable control of bacterial activity within tumor tissues, thereby increasing the safety and efficacy of bacteria-based cancer therapy4,6. The development of synthetic gene circuits, which can sense and respond to specific signals, enables bacteria to precisely control payload production (Table 1). In this Comment, we outline the progress in the engineering of bacteria for cancer immunotherapy, focusing mainly on studies using S. typhimurium and E. coli, the most widely investigated strains in the context of genetic engineering and cancer immunotherapy.

Table 1.

Example of bacteria-based cancer immunotherapy approaches

| Bacteria strain | Promoter | Inducer | Therapeutic payload | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. typhimurium ∆ppGpp | PBAD | L-arabinose | Pore-forming Cytolysin A (ClyA) | Killing cancer cells, which may enhance the antitumor immune response | 4,13 |

| Flagellin B (FlaB) | Enhanced M2-to-M1 macrophage polarization | ||||

| S. typhimurium ∆ppGpp | PTet | Doxycycline | ClyA and Renilla luciferase 8 (Rluc8) | Theranostic approach | 14 |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 | PDawn | Light | Tumor apoptosis-related inducing ligand (TRAIL) | Induction of tumor cell death, resulting in activation of antitumor immunity | 4 |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 | PBV220 | Temperature (Heat) | Tumor necrosis factor-α | Activation of immune responses against tumor | 17 |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 | PLacI | Focused ultrasound | PD-L1- and CTLA-4-blocking nanobodies | Enhanced antitumor T cell immunity | 19 |

| E. coli Nissle MG1655 | Acid-responsive promoter | Acid | ClyA | Killing cancer cells, which may enhance immune responses against tumors | 20 |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 | Quorum-sensing Plux | Acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) | CD47 nanobody (CD47nb) | Increased stimulation of tumor-infiltrating T cells targeting primary and metastatic tumors in animal tumor models | 26 |

| PD-L1- and CTLA-4-blocking nanobodies | Strong activation of antitumor T cell immunity | 6,21,33 | |||

| E. coli | Two AND-gate promoters | AHL and IPTG | Luminescence | Dynamic changes in gene expression | 23 |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 | Genome editing-Parg | NH4Cl | L-arginine | Enhanced antitumor activity of T cells | 6,21,34 |

Genetic engineering approaches for BCiT

In BCiT, genetic engineering is used to induce precise and effective antitumor responses. Various genetic circuits, comprising genes and promoters which control gene expression and bacterial growth, have been used to regulate biological functions4,6.

External triggering

Several bacterial promoters that respond to specific chemicals have been developed to ensure the expression of payloads in a dose-dependent and timely manner. Chemical inducers control the timing of payload production and its release within the tumor. However, the potential toxicity of some inducers and the risk of target gene leakage limit the use of this approach10–12. The PBAD promoter induced by L-arabinose in the pBAD system has been used to express antitumor payloads such as cytolysin A (ClyA) and an immunomodulatory flagellin subunit (FlaB), or to promote cellular invasion of engineered Salmonella4,12,13. An alternative strategy is to use a bidirectional Ptet promoter (PtetA and PtetR), which is induced by a class of FDA-approved antibiotics (doxycycline [Doxy] or tetracycline), to ensure the proportional expression of multiple payloads14.

Physical signals have been used to control the activity of cellular processes in living organisms. Unlike chemical inducers, physical signals such as visible light and heat are non-invasive, non-toxic, and artificially controllable; they can therefore be used to induce gene expression in a more spatiotemporal manner than conventional regulatory strategies, rendering them more suitable for BCiT15. Optogenetics is a combination of optical and genetic techniques in which light-sensitive proteins control genetic systems specific to a particular cellular activity15. Because visible light cannot pass deep into the tissues, the delivery of photons is an important issue with respect to optogenetics for in vivo applications. To overcome this, an upconversion optogenetic system is being developed to convert near-infrared light to visible blue light15,16. Thermal regulation has been more commonly used in BCiT than optogenetics. For example, the introduction of a gene circuit encoding an orthogonal heat switch into the E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) strain expressing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) or melanin, triggered a strong antitumor immune response17,18. EcN was engineered by the introduction of a temperature-activated genetic switch that induced the expression of therapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors in response to hypothermia triggered by a brief application of focused ultrasound (FUS)19.

Internal triggering and quorum sensing

The genetic circuit can be designed in a way that causes bacteria to specifically produce therapeutic agents in response to tumor-specific internal triggers, such as a certain pH, oxygen concentration, or glucose gradient in the TME4,6,20.

Because bacteria specifically colonize tumors and preferentially proliferate in the TME, the use of the bacterial quorum-sensing (QS) system can facilitate the release of therapeutic payloads into tumors without causing damage to healthy tissues6,21,22. In recent studies by Gurbatri et al. and Chowdhury et al., E. coli were engineered to express QS-responsive molecules such as acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)6, which induced bacterial lysis and the subsequent release of therapeutic payload when the bacterial population density reaches a specific threshold within the TME.

Synthetic logic circuit systems

A combination of gene circuits can be designed to respond to multiple input signals and prevent leaky expression caused by a single gene circuit. Boolean logic gates (i.e., AND, OR, and XOR) are suggested to generate output via multiple input signals in combination, based on digital logic rules. One of the simplest gates is the AND logic gate, in which all input signals are required to switch on the output. Shong et al. engineered E. coli harboring the QS-based AND logic gate, which controls gene expression by sensing both AHL and an additional input signal such as IPTG or anhydrotetracycline (aTc)23.

Engineering live bacteria for cancer immunotherapy

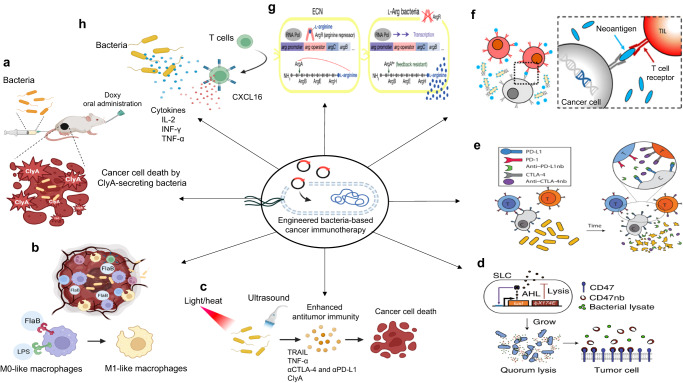

Tumor-colonizing bacteria can effectively activate innate and adaptive immune systems through surface components and intracellular molecules4. Together with their intrinsic immunostimulatory nature, expression/release of payloads can enhance antitumor immune responses; thus, the bacteria can be controlled precisely using synthetic biology approaches, ultimately improving overall therapeutic efficacy through recruitment and activation of the innate and adaptive immune systems (Fig. 1)6.

Fig. 1. Engineered bacteria-based cancer immunotherapy.

a, b In the presence of chemical molecules such as Doxy or l-arabinose, bacteria secrete ClyA to kill cancer cells, or FlaB to reprogram the TME, to increase recruitment of antitumor M1-like macrophages through TLR-4 and TLR-5 signaling4,13,14. c Other potential approaches include physical factors such as light, heat, or focused ultrasound, which can be used to stimulate bacteria to deliver immunotherapeutics into the TME4,6,17,19,35,36. d, e Bacteria have been genetically modified with the QS system, which in this case is based on the AHL autoinducer. In this system, AHL is produced via the luxI promoter and controlled expression of lysE, resulting in quorum-mediated lysis and intratumoral release of drugs such as CD47-blocking nanobodies or PD-L1- and CTLA-4-blocking nanobodies. Reproduced with permission from ref. 26, reprinted with permission from Springer Nature, ref. 33, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). f Tumor-infiltrating T cells stimulated by cleaved neoantigens detect and kill tumor cells. Reprinted with permission from ref. 27 (copyright 2021, American Chemical Society). g, h Engineered bacteria can also stimulate adaptive immune responses against tumors by secreting cytokines, chemokines, or other immunomodulatory cargoes to recruit and activate TILs in the TME6,21,34. Reproduced with permission from ref. 34 and reprinted with permission from Springer Nature. The image was created using BioRender.com.

Live bacteria act as strong immune adjuvants to recruit and stimulate innate immune cells such as monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages in tumors. These activated immune cells produce inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), TNF-α, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)4,6. For instance, ref. 13. engineered the ∆ppGpp strain to secrete heterologous FlaB, which led to an increase in the size of the M1-like proinflammatory macrophage population, while reducing M2-like anti-inflammatory macrophage numbers.

Bacteria can also be used to enhance the immunogenicity of “cold tumors”, which are characterized by a lack of cytotoxic T cell infiltration, by secreting cytokines or chemokines to attract T cells to the tumor site. The in situ production of potent immunostimulatory molecules, such as IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 16 (CXCL16), increases anticancer immune responses4,6,24. In a recent phase I clinical trial, the oral administration of Salmonella expressing human IL-2, a potent immunostimulatory cytokine, significantly increased the numbers of circulating natural killer (NK) and NKT cells in 22 patients with metastatic gastrointestinal cancer25.

Advances in synthetic biology have further improved the efficacy of BCiT. For example, a synchronized lysis gene circuit, which enables the controlled release of nanobodies specific for CD47, PD-L1, or CTLA-4, was developed to program the EcN strain6. CD47 interacts with thrombospondin-1 and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) to facilitate escape from macrophage-mediated immune surveillance by blocking phagocytotic mechanisms26. A non-pathogenic E. coli strain harboring the QS system can be engineered to deliver locally a CD47 nanobody as an immunotherapeutic payload to enhance antitumor immunity26. Moreover, a synthetic biology approach was used to engineer l-arginine-producing EcN, which increased the typically low l-arginine concentration within the TME and promoted an antitumor T cell response6,21.

The presentation of mutated tumor-derived antigens (neoantigens) by professional antigen-presenting cells induces potent tumor-specific T cell activation27. Hyun et al. used this principle to engineer a ∆ppGpp strain expressing multiple neoantigen peptides on the bacterial outer membrane. These peptides were specifically cleaved by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) expressed on tumor cells6. The subsequent release of neoantigens from bacterial cells at the tumor site enhanced the antitumor immune response by activating neoantigen-specific T cells.

Clinical trials and future outlooks

Significant progress has been made in the engineering of bacteria for BCiT. For instance, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), a live attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine, has been effectively used for high-risk, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer28,29. Furthermore, the National Institutes of Health’s website “clinicaltrials.gov” lists over 50 completed clinical trials of live bacteria, including Salmonella (n = 13), Listeria (n = 32), Clostridium (n = 4), Bifidobacterium (n = 2), and Yersinia (n = 1), for the treatment for various malignancies3,30. Indeed, BCiT with live bacteria is no longer limited to preclinical studies.

However, despite on-going clinical translational activities, drug development using live bacteria presents particularly difficult challenges both for investigators and regulatory authorities. First, the use of live bacteria in BCiT cannot be regulated in the same way as conventional drugs, while heating or filtering cannot be used to sterilize live bacteria. If the bacteria are to be used as therapeutic agents, it is crucial to maintain axenic cultures and eliminate potentially harmful substances, such as bacterial pathogens9. Moreover, the viability of therapeutic bacteria should be guaranteed (without batch-to-batch variation), regardless of any upscaling (to facilitate production on an industrial scale), packaging, shipping, or storage methods31. Second, determining the appropriate dose and schedule for BCiT is also challenging because bacteria may not follow conventional pharmacokinetics and may have a different dose-response relationship than other drugs. Effective doses may be related more closely to the quality of the target tumor rather than to the bacterial dose administered9. Third, pathogenic infection is a potential risk factor. Although the live bacteria used in BCiT have low levels of virulence and can be eradicated using antibiotics if required, they still pose a potential risk to immunocompromised patients, as well as to patients with abscesses, artificial joints/heart valves, or a recent history of radiation therapy use9. Thus, these patients may need to be excluded from BCiT clinical trials in the first instance. Finally, it is crucial to exclude bacterial strains carrying antibiotic resistance genes to avoid the risk of horizontal gene transfer9.

The currently available FDA guidance documents related to BCiT are “Microbial Vectors used for Gene Therapy” (September 2016)31 and “Preclinical Assessment of Investigational Cellular and Gene Therapy Products” (November 2013)32. Moreover, it is recommended that potential sponsors of investigational new drugs contact the FDA to obtain additional guidelines before submission.

In conclusion, the results of clinical trials will determine the practical application of BCiT in the clinic. Several engineered live bacterial therapeutics are currently entering early or mid-stage clinical development and may provide the proof of concept needed to determine the future of this new class of therapeutic agents. Upon reaching these milestones, developers of engineered bacterial therapeutics will be able to establish optimal safety, administration, and manufacturing processes, as well as determine how these agents can be effectively combined with existing therapies. Optimizing the application of this new category of drugs will address the significant unmet needs of patients. However, regulatory hurdles must be overcome to make this a reality.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (grant numbers NRF-2020M3A9G3080282, 2020R1A5A2031185, 2021C300, 2021M3C1C3097637, and 2020M3A9G3080330).

Author contributions

J.-J.M. and D.-H.N. conceived the Comment article and drafted the outline for submission. Sections 1–3 of the Comment were written by D.-H.N. and section 4 was written by A.C.; J.-J.M. and Y.H. critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jinyao Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dinh-Huy Nguyen, Ari Chong.

Contributor Information

Yeongjin Hong, Email: yjhong@chonnam.ac.kr.

Jung-Joon Min, Email: jjmin@jnu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.McCarthy EF. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop. J. 2006;26:154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sepich-Poore GD, et al. The microbiome and human cancer. Science. 2021;371:eabc4552. doi: 10.1126/science.abc4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang, S.-R., Nguyen, D.-H., Yoo, S. W. & Min, J.-J. Bacteria and bacterial derivatives as delivery carriers for immunotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.181, 114085 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Duong MT-Q, Qin Y, You S-H, Min J-J. Bacteria-cancer interactions: bacteria-based cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0297-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park S-H, et al. RGD peptide cell-surface display enhances the targeting and therapeutic efficacy of attenuated Salmonella-mediated cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2016;6:1672–1682. doi: 10.7150/thno.16135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurbatri CR, Arpaia N, Danino T. Engineering bacteria as interactive cancer therapies. Science. 2022;378:858–864. doi: 10.1126/science.add9667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo X, et al. Antitumor effect of VNP20009, an attenuated Salmonella, in murine tumor models. Oncol. Res. 2001;12:501–508. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clairmont C, et al. Biodistribution and genetic stability of the novel antitumor agent VNP20009, a genetically modified strain of Salmonella typhimuvium. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181:1996–2002. doi: 10.1086/315497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou S, Gravekamp C, Bermudes D, Liu K. Tumour-targeting bacteria engineered to fight cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18:727–743. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0070-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soheili N, et al. Design and evaluation of biological gate circuits and their therapeutic applications in a model of multidrug resistant cancers. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020;42:1419–1429. doi: 10.1007/s10529-020-02851-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng K, et al. Bioengineered bacteria-derived outer membrane vesicles as a versatile antigen display platform for tumor vaccination via Plug-and-Display technology. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raman V, et al. Intracellular delivery of protein drugs with an autonomously lysing bacterial system reduces tumor growth and metastases. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6116. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26367-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng JH, et al. Two-step enhanced cancer immunotherapy with engineered Salmonella typhimurium secreting heterologous flagellin. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaak9537. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aak9537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen D-H, et al. Optimized doxycycline-inducible gene expression system for genetic programming of tumor-targeting bacteria. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2022;24:82–92. doi: 10.1007/s11307-021-01624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan H, et al. Engineered NIR light-responsive bacteria as anti-tumor agent for targeted and precise cancer therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;426:130842. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.130842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, et al. Upconversion optogenetic engineered bacteria system for time-resolved imaging diagnosis and light-controlled cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022;14:46351–46361. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c14633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, et al. Precise thermal regulation of engineered bacteria secretion for breast cancer treatment in vivo. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022;11:1167–1177. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.1c00452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Cao Z, Zhang M, Lin S, Liu J. Spatiotemporally controllable distribution of combination therapeutics in solid tumors by dually modified bacteria. Adv. Mater. 2022;34:2106669. doi: 10.1002/adma.202106669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abedi MH, et al. Ultrasound-controllable engineered bacteria for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29065-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin W, et al. Bacteria‐elicited specific thrombosis utilizing acid‐induced cytolysin A expression to enable potent tumor therapy. Adv. Sci. 2022;9:2105086. doi: 10.1002/advs.202105086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Din MO, et al. Synchronized cycles of bacterial lysis for in vivo delivery. Nature. 2016;536:81–85. doi: 10.1038/nature18930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swofford CA, Van Dessel N, Forbes NS. Quorum-sensing Salmonella selectively trigger protein expression within tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3457–3462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414558112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shong J, Collins CH. Quorum sensing-modulated AND-gate promoters control gene expression in response to a combination of endogenous and exogenous signals. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014;3:238–246. doi: 10.1021/sb4000965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savage TM, et al. Chemokines expressed by engineered bacteria recruit and orchestrate antitumor immunity. Sci. Adv. 2023;9:eadc9436. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adc9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gniadek TJ, et al. A phase I, dose escalation, single dose trial of oral attenuated Salmonella typhimurium containing human IL-2 in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. J. Immunother. 2020;43:217. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chowdhury S, et al. Programmable bacteria induce durable tumor regression and systemic antitumor immunity. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1057–1063. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0498-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyun J, et al. Engineered attenuated Salmonella typhimurium expressing neoantigen has anticancer effects. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021;10:2478–2487. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.1c00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulchavenya E, Kholtobin D, Filimonov P. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and bovis as causes for shrinking bladder. J. Case Rep. Pr. 2013;3:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K. Bladder cancer: a review. JAMA. 2020;324:1980–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chong, A., Nguyen, D. -H., Kim, H. S., Chung, J. -K. & Min, J. J. Pattern of F-18 FDG uptake in colon cancer after bacterial cancer therapy using engineered Salmonella typhimurium:a preliminary in vivo study. Mol Imaging2022, 9222331 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Food, U. & Administration, D. Early clinical trials with live biotherapeutic products: chemistry, manufacturing, and control information. Guidance for Industry (2016).

- 32.Food, U. & Administration, D. Preclinical assessment of investigational cellular and gene therapy products. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) (2012).

- 33.Gurbatri, C. R. et al. Engineered probiotics for local tumor delivery of checkpoint blockade nanobodies. Sci. Transl. Med.12, eaax0876 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Canale FP, et al. Metabolic modulation of tumours with engineered bacteria for immunotherapy. Nature. 2021;598:662–666. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan J-X, et al. Bacteria-mediated tumor therapy utilizing photothermally-controlled TNF-α expression via oral administration. Nano Lett. 2018;18:2373–2380. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b05323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magaraci MS, et al. Engineering Escherichia coli for light-activated cytolysis of mammalian cells. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014;3:944–948. doi: 10.1021/sb400174s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]