Abstract

Introduction

Up to 35% of patients with a first episode of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) develop recurrent CDI (rCDI), and of those, up to 65% experience multiple recurrences. A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to review and summarize the economic impact of rCDI in the United States of America.

Methods

English-language publications reporting real-world healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and/or direct medical costs associated with rCDI in the USA were searched in MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, Embase, and the Cochrane Library databases over the past 10 years (2012–2022), as well as in selected scientific conferences that publish research on rCDI and its economic burden over the past 3 years (2019–2022). HRU and costs identified through the SLR were synthesized to estimate annual rCDI-attributable direct medical costs to inform the economic impact of rCDI from a US third-party payer’s perspective.

Results

A total of 661 publications were retrieved, and 31 of them met all selection criteria. Substantial variability was found across these publications in terms of data source, patient population, sample size, definition of rCDI, follow-up period, outcomes reported, analytic approach, and methods to adjudicate rCDI-attributable costs. Only one study reported rCDI-attributable costs over 12 months. Synthesizing across the relevant publications using a component-based cost approach, the per-patient per-year rCDI-attributable direct medical cost was estimated to range from $67,837 to $82,268.

Conclusions

While real-world studies on economic impact of rCDI in the USA suggested a high-cost burden, inconsistency in methodologies and results reporting warranted a component-based cost synthesis approach to estimate the annual medical cost burden of rCDI. Utilizing available literature, we estimated the average annual rCDI-attributable medical costs to allow for consistent economic assessments of rCDI and identify the budget impact on US payers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at (10.1007/s12325-023-02498-x).

Keywords: Cost estimation, Healthcare resource utilization, Medical costs, Recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, Systematic literature review

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? | |

| Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is a bacterial infection that may cause severe diarrhea and colitis. Recurrence of CDI is common, and older patients (> 65 years old) are especially vulnerable, with infection often leading to hospitalization and, in advanced cases, sepsis, colectomy, or death. | |

| High medical costs associated with rCDI in the USA have been reported in the literature; however, there has often been lack of consistency in the methodologies used or ways in which results are reported. With the emergence of new therapies for rCDI, establishing a benchmark medical cost burden for this condition will set a foundation for effectively evaluating the impact of such therapies in the real world. | |

| We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) on the economic burden associated with rCDI with currently available therapies to estimate the average annual per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs from a US third-party payer’s perspective. | |

| What was learned from this study? | |

| Our SLR found considerable variability in study design, population definition, and reporting approaches for the medical cost burden of rCDI in the USA with current available treatments. The variability prevented use of meta-analyses to comprehensively assess the annual medical cost per rCDI patient. Maximizing the available data in the literature, we used a component-based cost synthesis approach and provided an estimated range of the annual average per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs to a third-party payer in the USA. | |

| The cost estimation underscores the need for more effective therapies to prevent rCDI, improve rCDI-associated patient outcomes, and reduce rCDI-associated costs. |

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is characterized by severe diarrhea and colitis. C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive, spore-forming, toxin-producing bacillus transmissible via the fecal-oral route. CDI frequently occurs among patients recently exposed to antibiotics. Its spores are common in healthcare facilities and are also found in the environment and the food supply [1]. Older adults (aged 65 years or older) are especially vulnerable to CDI. With an estimated median age of diagnosis at 71 years, older adult patients have an estimated 5.7-fold higher incidence rate of CDI infection than patients younger than 65 years [2, 3]. Standard treatment typically involves antibiotic therapy such as oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for an initial episode of CDI [4]. Recurrent CDI (rCDI) remains common with currently available therapies. It is estimated that more than 35% of patients treated for an initial episode of CDI will have a rCDI, and approximately 65% of patients with an initial rCDI will experience subsequent recurrences [5–7].

The economic burden associated with rCDI is substantial due to the frequent need for hospitalizations, including treatment for sepsis, post-acute care, and in some more extreme cases, surgical interventions, including colectomy [8]. Moreover, rCDI-associated mortality is high, especially among older patients [9]. To address this high, unmet medical need, novel therapies are emerging for preventing rCDI [10]. With the expected availability of new treatment options for patients with rCDI, it is critical to establish a benchmark medical cost estimation for this condition, as it will provide an evidence-based foundation for effectively assessing the potential economic impact of these emerging rCDI therapies in the real-world clinical practice setting. We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) on the economic burden associated with rCDI with currently available therapies to provide an estimate of the average annual per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs from a US third-party payer’s perspective.

Methods

Literature Search

Real-world studies published in English reporting the healthcare resource utilization (HRU) or direct medical costs of adult patients with rCDI in the USA were identified following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. The search was conducted in April 2022 in MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, Embase, and the Cochrane Library databases, and in selected scientific conferences that publish research on rCDI and its economic burden. Seven scientific conferences were also included: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP), International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), Digestive Disease Week (DDW), Infectious Disease Week (IDWeek), United European Gastroenterology Week (UEG Week), American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), and Making a Difference in Infectious Diseases Annual Meeting (MAD-ID). The search included studies published over the past 10 years between January 1, 2012–April 13, 2022; conferences were searched for the past 3 years from 2019 through 2022. The search strategy and screening of studies followed the population, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study (PICOS) designs approach, as recommended by the Centre for Reviews and Disseminations (CRD) review guidelines (Table 1) [12].

Table 1.

PICOS inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies in the SLR

| Criteria | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult patients with rCDI in the USA | Study not including the patient population specified |

| Intervention and comparators | Any [e.g., standard of care antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin taper-pulse, fidaxomicin)] | N/A |

| Outcomes | Studies reporting at least one of the following HRU OR cost outcomes | Any study not including the outcomes specified |

| HRU of patients with rCDI (e.g., rates per year): | ||

| Hospitalization | ||

| Readmissions | ||

| ICU | ||

| ED visit | ||

| Post-acute care—including a skilled nursing facility, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or long-term acute care hospital or services provided by a home health agency | ||

| Outpatient visit | ||

| Stool test | ||

| Colectomy | ||

| Ileostomy reversal | ||

| Terminal care | ||

| Direct healthcare costs to US third-party payers (e.g., Medicare, commercial insurers) incurred by patients with rCDI: | ||

| Direct healthcare costs associated with the above items | ||

| Studies will be selected for inclusion based on availability of the outcomes listed above | ||

| Study design | Observational studies (e.g., prospective study, case–control study, case series), retrospective studies (e.g., claims analyses, EMR studies, registry studies) | Non-real-world evidence (e.g., clinical trials, editorials, letters, comments, economic models [cost–utility analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost–consequence analysis; cost–benefit analysis; cost minimization analysis; other economic models]); case reports of individual patients; SLRs, meta-analyses, article reviews |

| Other | Studies published in English USA setting | Studies not published in English; studies not set in the USA |

| Time period | Studies published within the last 10 years (2012–2022) | Studies published prior to the time period of interest |

ED emergency department, EMR electronic medical record, HRU healthcare resource utilization, ICU intensive care unit, rCDI recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, SLR systematic literature review

Included studies were required to report at least one type of HRU (e.g., hospitalization, readmissions, intensive care unit (ICU) visits, emergency department (ED) visits, post-acute care, outpatient visits, stool tests, colectomy, ileostomy reversal, or terminal care), or a direct cost component for any of these HRU items, in the intended patient population. The search focused on real-world cohort studies (retrospective) to reflect costs that are relevant to payers. Studies that did not report primary data on HRU or direct medical costs, and those not conducted in real-world settings (e.g., economic models, clinical trials, case reports, case series) were excluded. The full search strategy is detailed in Appendix Table 1. This study is based upon published literature and does not contain any new studies involving human participants or animals.

Publication Screening

All articles identified from the search were screened using a two-stage process. In stage one, all articles were screened based on their title and abstract. In stage two, those meeting the inclusion criteria were screened based on their full text using the same eligibility criteria as in stage one. To ensure accuracy, the screening of both publications and conference proceedings was conducted by two reviewers independently. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers or by a third reviewer. Publications that satisfied all selection criteria were included for data extraction.

Medical Cost Data Extraction

Extracted data included publication year, study type (e.g., claims database analysis, chart review), data source (e.g., survey, claims, electronic health record [13], methods, patient population, availability of data on specific rCDI populations (e.g., patients with first rCDI, with second or third rCDI), sample size by subgroup, cost year, duration of follow-up, and year(s) for reported outcomes. Availability of HRU outcomes and costs was summarized, and it was noted whether they were all-cause or attributable to rCDI.

Patient characteristics, prior treatments, and risk factors for rCDI, key comorbidities (e.g., heart failure, renal insufficiency, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease) were extracted. HRU prior to rCDI, and all-cause and rCDI-attributable per-patient per-year costs and HRU were extracted from all publications meeting the SLR criteria. Costs were adjusted for inflation to 2022 USD using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). To describe the available data, minimum and maximum all-cause and rCDI-attributable HRU and cost values were summarized for each given HRU category (i.e., hospitalizations, ICU visits, post-acute care, ED visits, or outpatient visits) with an annual time horizon.

Component-based Cost Synthesis for Annual rCDI-attributable Medical Cost

A meta-analysis of the SLR findings was considered to estimate per-patient per-year rCDI-attributable medical costs. However, substantial heterogeneity in the methods and characteristics of the populations across the publications made a meta-analysis infeasible. We therefore estimated per-patient per-year rCDI-attributable medical costs using a component-based cost synthesis approach. With this approach, available data are maximized for establishing the estimation in a transparent manner. Furthermore, this approach confers the ability to identify cost drivers and conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of a specific HRU or cost component included in the estimation. This methodology is also adaptable to incorporate new evidence, when available, to provide the most up-to-date estimate.

The key components considered in the cost synthesis analysis were rCDI-attributable hospitalizations, ICU visits, post-acute care (receipt of care post-hospital discharge in a non-acute healthcare facility [i.e., rehabilitation center, long-term care facility, skill nursing facility]), ED visits, outpatient visits, stool tests, colectomy, and ileostomy reversal. Given that death events are observed in these patients, rates of negative rCDI-attributable outcomes (i.e., need for terminal care, and mortality rate) and associated costs were also identified. Since the objective of the study was to estimate the average annual per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs from a US third-party payer’s perspective, the components of the cost-based cost synthesis analysis (i.e., annual utilization rates for each HRU category and associated unit costs) were extracted from the publications identified in the SLR with a ≥ 6-month duration of follow-up. In instances where data on HRU or costs from a single publication reported results separately for subgroups of patients by number of rCDI recurrences (e.g., patients with one rCDI, patients with two rCDIs) along with the sample sizes of each subgroup, weighted averages based on sample size distribution of the subgroups were calculated. When a range of utilization rates and/or unit costs were available for a given component, all values were considered to best inform the input(s) for the cost synthesis analysis. The minimum and maximum cost estimates for each HRU component were summed, respectively, to provide a range of rCDI-attributable annual per-patient total medical costs. A supplemental targeted search was conducted to provide data when cost elements were not available from the publications identified in the SLR, for example, ICU-day unit cost, cost of terminal care, etc. For such instances, PubMed, Google Scholar, and HCUPnet were searched to inform the value components.

As the objective was to estimate the average annual per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs from a US third-party payer’s perspective, the base case cost calculation utilized data from publications reporting estimates with a 12-month follow-up period. This threshold was selected to ensure proper extrapolation of the annual outcomes, HRU, and costs associated with rCDI. To test the robustness of the synthesized annual cost estimation for rCDI, sensitivity analyses were performed using additional values for the key cost drivers that were not considered in the base case evaluation. Specifically, the sensitivity analyses used data from publications that met all other requirements except for having a shorter follow-up period than 6 months. As such, publications used in the sensitivity analyses reported relevant HRU or cost results and had a duration of follow-up from 90 days to less than 6 months. Relevant HRU and costs inputs were annualized as appropriate. The sensitivity analysis values were individually tested in the cost component calculation while keeping all other base case inputs constant.

Results

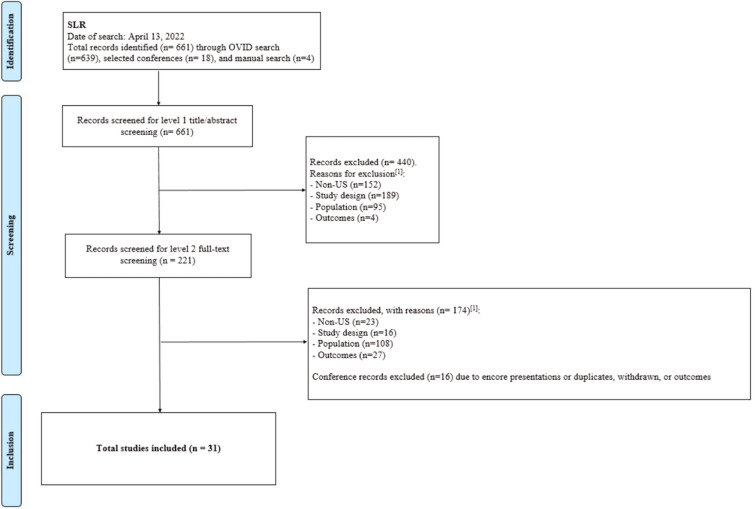

A total of 661 publications were identified for stage one screening (see PRISMA diagram, Fig. 1). Screening of titles and abstracts resulted in a total of 221 relevant articles. From the stage two (full-text) screening, a total of 31 publications were included for data extraction (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram. [1]The following hierarchy was applied to the exclusion criteria: (1) non-USA based, (2) study design, (3) population, (4) outcomes (e.g., if a study is both USA based and not the eligible study design, the reason for exclusion is “USA based”). PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses, SLR systematic literature review

Table 2.

Study characteristics of all included publications

| Study information | rCDI populations available | Cost results available | HRU results available | Cost time period | HRU time period | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Sample and relevant subgroups | Sample size by arm | Data source | Any rCDI | First rCDI | Second rCDI | Third or greater rCDI | All-cause | rCDI-attributable | All-cause | rCDI-attributable | Annual | 6-month | Annual | 6-month |

| Total | 31 | 17 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 21 | 17 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Zilberberg 2017 | rCDI—first recurrence | 4768 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rodrigues 2017 | rCDI—first recurrence | 98 | Other—single-center EHR + literature review | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Kuntz 2017 | rCDI—first recurrence | 4174 | Multi-center EHR | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Razik 2016 | rCDI—first recurrence | 35 | Multi-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Jasiak 2016 | rCDI—first recurrence | 34 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Dubberke 2014 | rCDI—any recurrence | 421 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Aitken 2014 | rCDI—first recurrence | 64 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 18 | ||||||||||||||

| Brandt 2012 | rCDI—first recurrence | 77 | Survey | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Hamilton 2012 | Non-IBD with rCDI—two or more recurrences | 29 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| IBD with rCDI—two or more recurrences | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| Venugopal 2012 | rCDI—first recurrence | 24 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Amin 2022 | rCDI—first recurrence—survivors | 40,277 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| rCDI—first recurrence—those that died | 27,806 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—second recurrence—survivors | 24,033 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—second recurrence—those that died | 12,713 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third recurrence—survivors | 33,428 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third recurrence—those that died | 13,339 | ||||||||||||||

| Unni 2020 | rCDI—first recurrence | 38,163 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 22,898 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third or greater recurrence | 32,147 | ||||||||||||||

| Sharma 2021 | rCDI | NR | National hospital database | X | X | X | |||||||||

| rCDI | NR | ||||||||||||||

| Essrani 2020 | rCDI—first recurrence | 84 | Chart review | X | X | X | |||||||||

| rCDI—first recurrence with prior appendectomy | 15 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—first recurrence without prior appendectomy | 69 | ||||||||||||||

| Tariq 2021 | rCDI—third or greater recurrence | 522 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Sadeghi 2022a | rCDI—third recurrence with prior CDI admission | 29 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Sadeghi 2022b | rCDI—fourth recurrence with prior CDI admission | 13 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Haran 2018 | rCDI—first recurrence | 161 | Multi-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Meighani 2017 | rCDI with no IBD | 181 | Multi-center EHR | X | X | ||||||||||

| rCDI with IBD | 20 | ||||||||||||||

| Zhang 2018 | rCDI—first recurrence | 8502 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Cheng 2019 | Three to five previous CDI episodes | 94 | Multi-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Zilberberg 2018 | rCDI—secondary diagnosis | 22,499 | National hospital database | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Ashraf 2020 | rCDI—any recurrence | 64 | Chart review | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Feuerstadt 2020 | rCDI—first recurrence | 3129 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 472 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third or greater recurrence | 134 | ||||||||||||||

| Feuerstadt 2021 | rCDI—first recurrence | 3129 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 472 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third recurrence | 134 | ||||||||||||||

| Reveles 2019 | rCDI—first recurrence | 2712 | National hospital database | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 858 | ||||||||||||||

| Overall CDI | 10,970 | ||||||||||||||

| Nelson 2021 | rCDI—first recurrence | 38,163 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 22,898 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third recurrence | 32,147 | ||||||||||||||

| Kruger 2019 | Any recurrence—with cirrhosis | 12,917 | National hospital database | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Any recurrence—without cirrhosis | 354,009 | ||||||||||||||

| Amin 2022 | rCDI—any recurrence—survivors | 97,738 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| rCDI—any recurrence—decedents | 53,858 | ||||||||||||||

| Feuerstadt 2022 | Primary CDI | 175,554 | Claims | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| rCDI—first recurrence | 38,163 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—second recurrence | 22,898 | ||||||||||||||

| rCDI—third or greater recurrence | 32,147 | ||||||||||||||

| Shah 2016 | rCDI—first or greater recurrence | 95 | Single-center EHR | X | X | X | |||||||||

CDI Clostridioides difficile infection, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, EHR electronic health record, HRU healthcare resource utilization, rCDI recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection

Study Characteristics of All Included Publications

The 31 publications identified for data extraction have substantial variability in terms of data source, studied populations, sample size, definition of rCDI, follow-up period, outcomes reported, analytic approach, and methods to adjudicate rCDI-attributable (Table 2). Studies include analyses of claims databases (9/31) [14–22], national hospital databases (4/31) [23–26], multi-center EHRs (5/31) [13, 27–30], single-center EHRs (10/31) [31–40], and survey/chart review studies (3/31) [41–43] (Table 2).The reported subgroups by number of recurrences were 18 studies on first rCDI, 9 on second rCDI, and 10 on third or greater rCDI. Sample size for subgroups by number of recurrences ranged from 13 (Sadeghi et al. 2022b, rCDI—fourth recurrence with prior CDI admission) to 354,009 patients (Kruger et al. 2019, rCDI—any recurrence without cirrhosis).

Definitions for rCDI also varied. For example, Rodrigues et al. 2017, a single-center EHR study with a literature review for cost inputs, performed a manual chart review for patients who had at least three International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) codes for CDI and at least two prescriptions for oral vancomycin to confirm an rCDI diagnosis through physician adjudication; this yielded a cohort of patients with at least two episodes of CDI with the second infection occurring within 56 days after the end of treatment for the index infection [31]. Feuerstadt et al. 2020 was a claims database analysis of the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus database that defined two episodes of CDI as at least one inpatient claim with an ICD-9 code for CDI or one outpatient medical claim with an ICD-9 code for CDI plus a CDI treatment, with the second episode occurring within an 8-week (56 days) window following a 14-day claim-free period after end of treatment for the index CDI episode [20]. Zhang et al. (2018) was a claims database analysis of MarketScan data that defined an episode of CDI as any claim with at least one ICD-9 code for CDI and defined recurrences as any CDI episodes that occurred within 84 days (12 weeks) of the previous episode [19]. Other studies met the inclusion criteria for the study and are included in Table 2 but did not meet the criteria for the cost calculations [28, 36, 41].

In terms of duration of follow-up, eight reported annual cost and/or HRU [14, 18, 20–22, 27, 31, 37]. Among these, six reported for populations with first rCDI, five with second rCDI, and six with third or greater rCDI. Four of them reported both annual cost and HRU. However, only Rodrigues et al. 2017 reported rCDI-attributable costs, while the others reported all-cause costs only. Two studies reported 6-month estimates; one was by Dubberke et al. 2014, which was a single-center EHR study and included patients with any recurrence, and the other was by Zhang et al. 2018, which was a MarketScan analysis and included patients with first rCDI only [19, 33]. The remaining studies reported costs and/or HRU over shorter time periods, including over the course of one hospitalization, 1 month, or 3 months (Table 2).

Study Characteristics of Publications Reporting Annual or Semi-annual Estimates

Across the eight publications reporting annual estimates, there were substantial variations in population characteristics (Table 3). The mean age ranged from 47.9 years (Feuerstadt et al. 2020) to 78.3 years (Nelson et al. 2021 and Feuerstadt et al. 2022). Percentage of female patients ranged from 54.3% (Tariq et al. 2021) to 69.1% (Feuerstadt et al. 2022) [14, 20, 22, 37]. Insurance or medical networks included in these patient populations were Kaiser Permanente (Kuntz 2017), Medicare (Nelson 2021), Partners Healthcare Network (Rodrigues 2017), and commercial insurance (Feuerstadt 2020) [20, 22, 27, 31].

Table 3.

Patient characteristics of publications reporting annual or semi-annual costs and/or HRU[1]

| Source | (Sub)group | Sample size | Patient characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—mean (SD) | Female—% | Prior treatments—antibiotics, n (%) | Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SD) | Heart failure—% | Comorbidities—Renal insufficiency, n (%) | Comorbidities—IBD, n (%) | Comorbidities—diabetes, n (%) | Comorbidities—other, n (%) | HRU prior to rCDI | |||

| Dubberke 2014 | Any recurrence | 421 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Rodrigues 2017 | Any recurrence | 98 | 66.7 (16.5) | 62.0% |

Treatment of initial episode, n (%) Metronidazole, n (%): 31 (32) Vancomycin, n (%): 31 (32) Metronidazole + Vancomycin, n (%): 25 (26) |

8.6 (4.2) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kuntz 2017 | First recurrence | 4,174 | 62.3 (16.1) | 61.8% | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Zhang 2018 | First recurrence | 8,502 | 63.7 (19.9) | 63.9% | 5,655 (66.5%) | 3.2 (3.4) | NR | 2,155 (25.4) | 532 (6.3) | 2,244 (26.4) |

Cancer: 281 (3.3) Cardiovascular disease: 1,894 (22.3) Pulmonary disease: 5,840 (68.7) Immunocompromised: 1,996 (23.5) |

Inpatient hospital visits-Mean (SD): 0.6 (0.8) ED visits-Mean (SD): 0.2 (0.5) Doctor office visits-Mean (SD): 4.7 (4.8) |

| Unni 2020 | First recurrence | 38,163 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Second recurrence | 22,898 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Third or more recurrence | 32,147 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Source | (Sub)group | Sample size | Patient characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—mean (SD) | Female—% | Prior treatments—antibiotics, n (%) | Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SD) | Heart failure—% | Comorbidities—Renal insufficiency, n (%) | Comorbidities—IBD, n (%) | Comorbidities—diabetes, n (%) | Comorbidities—other, n (%) | HRU prior to rCDI | |||

| Tariq 2021 | Third or greater CDI episode, FMT failures | 70 | Median (range): 53.8 (18–89) | 54.3% |

1 + prior metronidazole: 43 (61.4) 1 + prior vancomycin: 69 (98.5) 1 + prior fidaxomicin: 16 (22.8) |

NR | NR | NR | IBD, n (%): 24 (34.3) | NR |

Immunocompromised state: 28 (40.0) Diverticulosis: 12 (17.1) |

Presence of CDI-related hospitalization before FMT (yes/no): 38 (54.3%) > 1 CDI-related hospitalization before FMT (yes/no): 27 (38.7%) |

| Feuerstadt 2020 | First recurrence | 3,129 | 48.3 (12.8) | 65.1% | 2,509 (80.2) | 1.5 (2.2) | NR | 571 (18.3) |

Ulcerative colitis, n (%): 238 (7.6) Crohn’s disease, n (%): 175 (5.6) |

Type 1 diabetes: 134 (4.3) | Autoimmune disease: 723 (23.1) |

Pre-index (0–6 months prior) HUR, n (%) Inpatient admission: 1,307 (41.8) Outpatient hospital visit: 2,576 (82.3) ED visit: 1,581 (50.5) Outpatient office visit: 2,951 (94.3) |

| Second recurrence | 472 | 47.9 (13.0) | 67.6% | 381 (80.7) | 1.8 (2.3) | NR | 105 (22.3) |

Ulcerative colitis, n (%): 39 (8.3) Crohn’s disease, n (%): 22 (4.7) |

Type 1 diabetes: 18 (3.8) | Autoimmune disease: 116 (24.6) |

Pre-index (0–6 months prior) HUR, n (%) Inpatient admission: 236 (50.0) Outpatient hospital visit: 404 (85.6) ED visit: 268 (56.8) Outpatient office visit: 455 (96.4) |

|

| Third or more recurrence | 134 | 48.7 (11.5) | 61.2% | 103 (76.9) | 2.3 (2.5) | NR | 36 (26.9) |

Ulcerative colitis, n (%): 21 (15.7) Crohn’s disease, n (%): 11 (8.2) |

Type 1 diabetes: 11 (8.2) | Autoimmune disease: 53 (39.6) |

Pre-index (0–6 months prior) HRU, n (%) Inpatient admission: 81 (60.5) Outpatient hospital visit: 116 (86.6) ED visit: 77 (57.5) Outpatient office visit: 129 (96.3) |

|

| Feuerstadt 2021 | First recurrence | 3,129 | 48.3 (12.8) | 65.1% | 2,509 (80.2) | 1.54 (2.2) | NR | 571 (18.3) |

Ulcerative colitis, n (%): 238 (7.6) Crohn’s disease, n (%): 175 (5.6) |

NR | Autoimmune diseases: 723 (23.1) |

HRU 0–6 months pre-index, n (%) Inpatient admission: 1307 (41.8) Inpatient admission with ICU stay: 132 (4.2) Outpatient hospital visit: 2576 (82.3) ED visit: 1581 (50.5) |

| Second recurrence | 472 | 47.9 (13.0) | 67.6% | 381 (80.7) | 1.83 (2.3) | NR | 105 (22.3) |

Ulcerative colitis, n (%): 39 (8.3) Crohn’s disease, n (%): 22 (4.7) |

NR |

Autoimmune diseases: 116 (24.6) Current or history of smoking: 89 (18.9) |

HRU 0–6 months pre-index, n (%) Inpatient admission: 236 (50.0) Inpatient admission with ICU stay: 21 (4.5) Outpatient hospital visit: 404 (85.6) ED visit: 268 (56.8) |

|

| Source | (Sub)group | Sample size | Patient characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—mean (SD) | Female—% | Prior treatments—antibiotics, n (%) | Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SD) | Heart failure—% | Comorbidities—Renal insufficiency, n (%) | Comorbidities—IBD, n (%) | Comorbidities—diabetes, n (%) | Comorbidities—other, n (%) | HRU prior to rCDI | |||

| Third or more recurrence | 134 | 48.7 (11.5) | 62.2% | 103 (76.9) | 2.29 (2.5) | NR | 36 (26.9) |

Ulcerative colitis, n (%): 21 (15.7) Crohn’s disease, n (%): 11 (8.2) |

NR |

Autoimmune diseases: 53 (39.6) Current or history of smoking: 30 (22.4) |

HRU 0–6 months pre-index, n (%) Inpatient admission: 81 (60.5) Inpatient admission with ICU stay: 13 (9.7) Outpatient hospital visit: 116 (86.6) ED visit: 77 (57.5) |

|

| Nelson 2021 | First recurrence | 38,163 | 78.1 (7.9) | 69.1% |

Outpatient medication exposure Antimicrobials, %: 85.3 |

5.2 (3.4) | 45.3% | Renal disease, %: 39.7 | NR | Diabetes, %: 45.8 |

Chronic pulmonary disease, %: 50.6 CVD, %: 39.9 PVD, %: 44.6 |

0–6 months pre-index Patients with inpatient admission, %: 58.0 Patients with ED visit, %: 41.6 Number of outpatient visits per patient, mean (SD): 11.2 (8.4) 7–12 months pre-index Patients with inpatient admission, %: 27.7 Patients with ED visit, %: 27.5 Number of outpatient visits per patient, mean (SD): 9.2 (7.6) Procedures, % GI surgery: 4.5 Transplant: 2.3 |

| Second recurrence | 22,898 | 78.3 (7.9) | 69.0% |

Outpatient medication exposure Antimicrobials, %: 86.8 |

5.2 (3.4) | 44.5% | Renal disease, %: 40.4 | NR | Diabetes, %: 45.2 |

Chronic pulmonary disease, %: 50.5 CVD, %: 39.1 PVD, %: 44.1 |

0–6 months pre-index Patients with inpatient admission, %: 59.4 Patients with ED visit, %: 43.7 Number of outpatient visits per patient, mean (SD): 11.5 (8.5) 7–12 months pre-index Patients with inpatient admission, %: 27.5 Patients with ED visit, %: 28.3 Number of outpatient visits per patient, mean (SD): 9.2 (7.5) Procedures, % GI surgery: 4.2 Transplant: 3.4 |

|

| Source | (Sub)group | Sample size | Patient characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—mean (SD) | Female—% | Prior treatments—antibiotics, n (%) | Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SD) | Heart failure—% | Comorbidities—Renal insufficiency, n (%) | Comorbidities—IBD, n (%) | Comorbidities—diabetes, n (%) | Comorbidities—other, n (%) | HRU prior to rCDI | |||

| Third or more recurrence | 32,147 | 77.9 (8.0) | 67.5% |

Outpatient medication exposure Antimicrobials, %: 89.8 |

5.2 (3.5) | 43.5% | Renal disease, %: 43.2 | NR | Diabetes, %: 44.3 |

Chronic pulmonary disease, %: 49.4 CVD, %: 37.3 PVD, %: 43.0 |

0–6 months pre-index Patients with inpatient admission, %: 60.7 Patients with ED visit, %: 44.8 Number of outpatient visits per patient, mean (SD): 12.4 (9.1) 7–12 months pre-index Patients with inpatient admission, %: 27.7 Patients with ED visit, %: 27.8 Number of outpatient visits per patient, mean (SD): 9.6 (7.9) Procedures, % GI surgery: 4.3 Transplant: 12.4 |

|

| Feuerstadt 2022 | First recurrence | 38,163 | Mean (SD): 78.1 (7.9) | 69.1% | Antimicrobials, %: 85.3 | 5.2 (3.4) | 45.30% | Renal disease, %: 39.7 |

Crohn's disease, %: 2.4 Ulcerative colitis, %: 6.3 |

Diabetes, %: 45.8 |

Chronic pulmonary disease, %: 50.6 CVD, %: 39.6 PVD, %: 44.6 |

0–6 months pre-index: Patients with inpatient admission, 58.0% Patients with ED visit, 41.6% Outpatient visits per patient, mean 11.2 (8.4) 7–12 months pre-index: Patients with inpatient admission, 27.7% Patients with ED visit, 27.5% Outpatient visits per patient, mean 9.2 (7.6) |

| Second recurrence | 22,898 | Mean (SD): 78.3 (7.9) | 69.0% | Antimicrobials, %: 86.8% | 5.2 (3.4) | 44.50% | Renal disease, %: 40.4 |

Crohn's disease, %: 2.5 Ulcerative colitis, %: 6.5 |

Diabetes, %: 45.2 |

Chronic pulmonary disease, %: 50.5 CVD, %: 39.1 PVD, %: 44.1 |

0–6 months pre-index: Patients with inpatient admission, 59.4% Patients with ED visit, 43.7% Outpatient visits per patient, mean 11.5 (8.5) 7–12 months pre-index: Patients with inpatient admission, 27.5% Patients with ED visit, 28.3% Outpatient visits per patient, mean 9.2 (7.5) |

|

| Third or more recurrence | 32,147 | Mean (SD): 77.9 (8.0) | 67.5% | Antimicrobials, %: 89.8 | 5.2 (3.5) | 43.50% | Renal disease, %: 43.2 |

Crohn's disease, %: 2.2 Ulcerative colitis, %: 6.2 |

Diabetes, %: 44.3 |

Chronic pulmonary disease, %: 49.4 CVD, %: 37.3 PVD, %: 43.0 |

0–6 months pre-index: Patients with inpatient admission, 60.7% Patients with ED visit, 44.8% Outpatient visits per patient, mean 12.4 (9.1) 7–12 months pre-index: Patients with inpatient admission, 27.7% Patients with ED visit, 27.8% Outpatient visits per patient, mean 9.6 (7.9) |

|

CDI Clostridioides difficile infection, CVD cardiovascular disease, ED emergency department, EHR electronic health record, FMT fecal microbial transplantation, GI gastrointestinal, HRU healthcare resource utilization, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, NR not reported, PVD peripheral vascular disease, rCDI recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection

1Data in this table are as reported in each respective study

Variations in underlying health conditions were demonstrated as measured by Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI; mean CCI scores:1.5 [Feuerstadt et al. 2021] to 8.6 [Rodrigues et al. 2017] [21, 31]), but not all studies reported comorbidities. History of heart failure was high and was reported in two studies using the same source, Medicare fee-for-service claims data at 43.5% to 45.3% (Nelson et al. 2021 and Feuerstadt et al. 2022); history of renal disease/insufficiency ranged from 18.3% (Feuerstadt et al. 2020 and Feuerstadt et al. 2021) to 43.2% (Nelson et al. 2021 and Feuerstadt et al. 2022) [14, 20–22]. Other common comorbidities included cancer, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and immunocompromised status [19].

The majority of studies reported that patients had antibiotic treatment prior to rCDI (76.9% [Feuerstadt et al. 2020 and Feuerstadt et al. 2021, third or greater rCDI] to 89.8% [Nelson et al. 2021 and Feuerstadt et al. 2022, third or greater rCDI]) [14, 20–22]. HRU prior to rCDI was commonly reported as inpatient admission, outpatient visit, and ED visit, and varied greatly depending on patient population (Table 3). In Zhang et al. 2018, prior antibiotic use was reported in 66.5% [19].

HRU and Cost Publications Reporting Annual or Semi-annual Estimates

All-cause per-patient per-year HRU varied widely among four studies reporting annual estimates (Table 4). Studies reported hospitalization ranging from 1.1 visits with associated cumulative length of stay (LOS) of 8.4 days (Kuntz et al. 2017, first rCDI) to 5.8 visits with associated mean LOS of 8.5 days per hospitalization (Feuerstadt et al. 2020, third or greater rCDI). Only Kuntz et al. 2017 reported all-cause ICU admissions and estimated a mean of 0.9 days per-patient among patients with first rCDI [27]. The proportion of patients receiving care in a post-acute setting ranged from 69.8% (Nelson et al. 2021, third or greater rCDI) to 74.6% (Nelson et al. 2021, first rCDI) [22]. Moreover, the mean number of ED visits per-patient per-year ranged from 1.4 (Nelson et al. 2021, first rCDI) to 4.6 visits (Feuerstadt et al. 2020, third or greater rCDI) [20, 22]. The number of outpatient visits ranged from 15.4 (Rodrigues et al. 2017, any rCDI) to 26.3 visits (Nelson et al. 2021, third or greater rCDI) per-patient per-year [22, 31]. Only one study, Rodrigues et al. 2017, reported rCDI-attributable HRU of hospitalization visits, LOS, ICU days, ED visits, and outpatient visits (Table 4) [31]. Of the two studies reporting semi-annual estimates, only Zhang et al. 2018 reported HRU [19]. This study reported an average of 9.3 cumulative hospitalized days for a rCDI cohort and 7.3 days for a matched primary CDI cohort, leading to 2.0 rCDI-attributable hospitalizations days incremental over primary CDI.

Table 4.

Per-patient per-year HRU in publications reporting annual or semi-annual estimates

| HRU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization | Intensive care unit | Post-acute care | Emergency department visit | Outpatient visit | |

| Any rCDI (all-cause) | |||||

|

Minimum values Source and population[1] |

1.1 visits; 8.4 days LOS Kuntz 2017-Kaiser Permanente rCDI (1st) |

0.9 days Kuntz 2017-Kaiser Permanente rCDI (1st) |

69.8% patients Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (3rd +) |

1.4 visits Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

15.4 visits Rodrigues 2017-Partners Healthcare Network Boston rCDI |

|

Maximum values Source and population |

5.8 visits; 8.5 days LOS Feuerstadt 2020-Commercial rCDI (3rd +) |

74.6% patients Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

4.6 visits Feuerstadt 2020-Commercial rCDI (3rd +) |

26.3 visits Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (3rd +) |

|

| Any rCDI (rCDI-attributable) | |||||

| Source and population |

1.6 visits; 15.8 days LOS Rodrigues 2017-Partners Healthcare Network Boston rCDI |

0.2 days Rodrigues 2017-Partners Healthcare Network Boston rCDI |

– |

0.1 visits Rodrigues 2017-Partners Healthcare Network Boston rCDI |

2.2 visits Rodrigues 2017-Partners Healthcare Network Boston rCDI |

HRU healthcare resource utilization, LOS length of stay, rCDI recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, SLR systematic literature review

[1] Numbers in parentheses indicate the recurrence number of rCDI

Total all-cause per-patient per-year costs varied widely in two studies of patients with any rCDI (Table 5). When inflation-adjusted to 2022 USD, estimates ranged from $93,979 (Nelson et al. 2021, second rCDI) to $231,149 (Feuerstadt et al. 2020, third or greater rCDI). Only one study, Rodrigues et al. 2017, reported rCDI-attributable total costs for the any-rCDI population: $39,668 per-patient per-year [31].

Table 5.

Per-patient per-year costs in publications reporting annual or semi-annual estimates, inflation-adjusted to 2022 USD

| Costs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization | Intensive care unit | Post-acute care | Emergency department visit | Outpatient visit | Other costs[2] | Total costs | |

| Any rCDI (all-cause) | |||||||

|

Minimum value Source and population[1] |

$16,714 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

$13,949 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (3rd +) |

$17,241 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (3rd +) |

$1107 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

$10,377 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

$1206 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (2nd) |

$93,979 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (2nd) |

|

Maximum value Source and population |

$157,385 Feuerstadt 2020-Commercial rCDI (3rd +) |

$17,703 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

$26,357 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (1st) |

$1269 Nelson 2021-Medicare rCDI (3rd +) |

$50,040 Feuerstadt 2020-Commercial rCDI (3rd +) |

$23,724 Feuerstadt 2020-Commercial rCDI (3rd +) |

$231,149 Feuerstadt 2020-Commercial rCDI (3rd +) |

| Any rCDI (rCDI-attributable) | |||||||

|

Available value Source and population |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

$39,668 Rodrigues 2017-Partners Healthcare Network Boston rCDI |

rCDI recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, SLR systematic literature review, USD US dollar.

[1] Numbers in parentheses indicate the recurrence number of rCDI

[2] Other costs include costs of surgery, pharmacy, diagnostic tests, medical equipment use, and physician services

Among the studies reporting semi-annual estimates, rCDI-attributable hospitalization costs incremental over primary CDI ranged from $12,061 (Zhang et al. 2018, first rCDI) to $16,150 (Dubberke et al. 2014, any rCDI) when inflation-adjusted to 2022 USD [19, 33]. Among these studies only Zhang et al. 2018 reported a total rCDI-attributable cost incremental over primary CDI of $13,109.

Estimated Annual rCDI-attributable Medical Cost—Base-Case Estimate

To estimate the average annual total rCDI-attributable medical cost, we calculated each component cost of rCDI-attributable HRU based on literature in the SLR, as well as those from the supplemental search for hospitalization stay unit cost per day, ICU unit cost per day, post-acute care cost, outpatient visit unit cost, ileostomy reversal unit cost and rate, terminal care unit cost for end of life care, and mortality rate [44–50]. Rodrigues et al. 2017 was the only study reporting annual rCDI-attributable HRU and provided estimates of HRU components that are relevant for a payer [31]. It was used to inform the following HRU components in the base case cost calculation: rCDI-related hospitalizations and associated LOS (1.6 mean rCDI-related hospitalizations per patient × 15.8 mean LOS = 25.3 total days/year), rCDI-related ICU LOS (0.2 days/year), rCDI-related ED visits (0.1 visits/year), rCDI-related outpatient visits (2.2 visits/year), and rCDI-related stool tests (4.4 tests/year) per patient. [44–50]. The HRU estimates post-acute care was 21.1 days/year (Nelson et al. 2021 and Rodrigues et al. 2017); mortality rates included 11.0%, 9.0%, and 34.3% (Olsen et al. 2019 and Amin et al. 2022b); the colectomy rate ranged from 7.3% and 6.0% (Feuerstadt et al. 2021 and Feuerstadt et al. 2022); and the ileostomy reversal rate was 7.1% (Feuerstadt et al. 2021 and Neal et al. 2011) [14, 17, 21, 22, 31, 48, 50]. Table 6 includes the detailed HRU estimates used in the cost estimation. Unit costs for post-acute care ($562/day) and ED visits ($1,004/visit) as well as the lower bound colectomy rate (6.0%) were calculated as weighted averages based on results reported for the subgroups of patients 1, 2, and 3 + rCDI from Nelson et al. 2021 and Feuerstadt et al. 2022, respectively [14, 22].

Table 6.

Per-patient per-year rCDI-attributable medical cost calculation details

| Cost categories | Total costs | Cost input option(s) | HRU input option(s) | Sources[1] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min-Average annual cost with min input values | Max-Average annual cost with max input values | ||||

| Hospitalization | $45,298 | $51,547 |

$2039 (A) $1792 (B) |

25.3 days/year |

Cost (A): general-HCUPnet Cost (B): rCDI-Zilberberg 2018 HRU: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 |

| Intensive care unit | $942 | $942 | $5232 | 0.2 days/year |

Cost: general-Halpern 2016 HRU: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 |

| Post-acute care | $11,849 | $11,849 | $562 | 21.1 days/year |

Cost: rCDI-Nelson 2021 HRU: rCDI-Nelson 2021; Rodrigues 2017 |

| Emergency department visit | $120 | $120 | $1004 | 0.1 visits/year |

Cost: rCDI-Nelson 2021 HRU: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 |

| Outpatient visit | $459 | $459 | $209 | 2.2 visits/year |

Cost: general-Optum360 National Fee Analyzer HRU: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 |

| Stool test | $257 | $257 | $58 | 4.4 tests/year |

Cost: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 HRU: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 |

| Colectomy | $6243 | $6950 | $54,421 |

7.3% annual rate (A) 6% annual rate (B) |

Cost: rCDI-Rodrigues 2017 HRU (A): rCDI-Feuerstadt 2021 HRU (B): rCDI-Feuerstadt 2022 |

| Ileostomy reversal | $42,237 | 7.1% annual rate |

Cost: rCDI-Wilson 2013 HRU: rCDI-Feuerstadt 2021; Neal 2011 |

||

| Terminal care/mortality | $2668 | $10,142 |

$53,333 (A) $29,565 (B) |

10.9% annual rate (A) 9.0% annual rate (B) 34.3% annual rate (C) |

Cost (A): general-Byhoff 2016 Cost (B): rCDI-Amin 2022b HRU (A): rCDI-Olsen 2019 HRU (B): rCDI-Amin 2022b HRU (C): all-cause-Amin 2022b |

| Total costs | $67,837 | $82,268 | |||

[1] rCDI and general indicate whether the study was conducted in an rCDI or a general population. All-cause indicates all-cause HRU

The per-patient per-year rCDI attributable direct medical cost, estimated from the component-based cost synthesis approach, ranged from $67,837–$82,268 (Table 6). The cost drivers in order from largest to smallest were hospitalizations (62.7–66.8%), post-acute care (14.4–17.5%), colectomy and ileostomy reversals (8.4–9.2%), terminal care/morality (3.9–12.3%), ICU (1.1–1.4%), outpatient visits (0.6–0.7%), stool tests (0.3–0.4%), and ED visits (0.1–0.2%).

HRU and Cost Publications Informing Sensitivity Analyses

As rCDI-attributable hospitalization cost per year was the largest driver of the base case total cost calculation (approximately two-thirds), alternative values for hospitalization parameters were tested as sensitivity analyses. Four publications were identified that had 90-day or longer follow-up, included relevant HRU or cost data, and were conducted in a study population that could potentially be generalized to a wider rCDI population. Two of these publications (Aitken et al. 2014 and Zhang et al. 2018) were excluded due to potential bias in estimating rCDI-attributable hospitalization LOS or cost for the given study design or data source (Appendix 1) [19, 34].

Shah et al. 2016 and Dubberke et al. 2014 were included in the sensitivity analyses [33, 40]. Shah et al. 2016 was a prospective, single-center cohort study including of 540 adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) who were hospitalized for CDI at a tertiary care hospital in Houston, Texas between 2007 and 2013 [40]. Patients were followed for 3 months to assess rCDI episodes, with HRU data prospectively obtained from patients’ online medical chart and/or by direct patient interview. rCDI-attributable hospitalization was defined as CDI diagnosis within 72 h of admission. Costs were estimated based on publicly available Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data; however, the methods are not clearly reported, so only HRU results were considered for the sensitivity analysis. Over 3 months, 95 (17.6%) patients (mean age: 66 years) experienced 101 rCDI episodes, for which 38 patients (40.0%) had an rCDI-attributable hospitalization. The median LOS attributable to rCDI was 15 days.

Dubberke et al. 2014 was a retrospective, single-center cohort study of data from an academic tertiary care facility in St. Louis, Missouri, among 3958 adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) hospitalized with a CDI episode from 2003 through 2009 [33]. Patients were followed for 180 days from the end of the hospitalization or end of antibiotic treatment (whichever occurred later). Data were collected from hospital administrative databases with supplemental data from chart review. Zero-inflated lognormal models were used to assess rCDI-attributable hospitalization costs of patients with rCDI versus those without a recurrence. Over 180 days, 421 (10.6%) patients experienced an rCDI episode (mean age for rCDI patients was not reported; overall population age quartiles were reported as 24.1% under 49 years, 26.0% 49– < 62 years, 24.5% 62–< 74 years, and 25.3% ≥ 74 years). The study estimated an rCDI-attributable hospitalization cost of $11,631 in 2010 USD (95% confidence interval, $8937–$14,588).

Estimated Average Annual rCDI-attributable Medical Cost—Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analysis 1 (Shah et al. 2016) incorporates an alternative LOS input reported for admissions attributable to rCDI over 3 months [40]. To calculate the sensitivity analysis input, the median reported LOS value of 15 days was annualized to 60 days. A weighted average was then calculated to determine the LOS for the overall population, conducted among those who had an rCDI-attributable hospitalization and those who did not (LOS of 0 days). The weights used the number of patients who had an rCDI-attributable hospitalization and those who did not (38 patients with and 57 without). The resulting sensitivity analysis LOS input was 24 days. Sensitivity analysis 1 yielded a total result of a $65,543–$79,658 per-patient per-year rCDI-attributable direct medical cost.

Sensitivity analysis 2 (Dubberke et al. 2014) uses an alternative rCDI-attributable hospitalization cost input. The 180-day rCDI-attributable hospitalization cost relative to primary CDI reported in Dubberke et al. 2014 was $32,770 when inflation-adjusted to 2022 USD and annualized [33]. Using this alternative cost input in the sensitivity analysis yielded a range of $55,309 to $63,491 for the per-patient per-year rCDI-attributable direct medical cost.

Discussion

We conducted an SLR of the direct economic burden of managing patients with rCDI with current approaches from the perspective of the third-party payers in the USA. In the SLR, eight publications were identified that reported annual HRU and/or direct medical costs to US third-party payers. Key differences were observed in study designs, patient populations, identification of rCDI, and analytic approaches for estimating CDI-attributable costs and HRU. This heterogeneity in the published data is consistent with the findings of a recent SLR by Malone et al. 2022 on real-world evidence of HRU and burden of illness associated with CDI (including rCDI). Similar to our study, Malone et al. (2022) found a large variation in data sources, comparison groups, methodologies, and reporting across studies [51].

The large variation found from this search made it infeasible to perform a meta-analysis to synthesize the results. To estimate the average annual per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs based on the SLR findings, we performed a component-based cost synthesis analysis given the lack of comprehensive rCDI-attributable annual medical costs data. By employing a component-based cost synthesis approach that relied primarily on studies identified in the SLR with an annual time horizon, we were able to estimate the annual per-patient rCDI-attributable direct medical costs from the US third-party payer’s perspective using aggregated relevant HRU and cost inputs from multiple sources in a systematic fashion. This method allows for each relevant component that contributes to the average medical cost on payers to be considered directly from the available literature. Overall, the results of component-based cost synthesis analysis suggest that the annual rCDI-attributable costs range from $67,837 to $82,268 for an average rCDI patient in the base-case analysis.

Not surprisingly, the main cost driver of annual cost in the base-case component-based cost synthesis analysis was hospitalization (62.7–66.8% of total costs), driven by a mean 25.2 day LOS calculated based on data reported by Rodrigues et al. 2017 [31]. Of note, the inpatient days per year reported by Rodrigues and colleagues may be higher than some other clinical settings due to potentially more severely ill and older patients included in this study. As a result, sensitivity analyses were conducted to test alternative rCDI-attributable hospitalization LOS or cost input based on studies with at least 60-days follow-up and with a study population that could be generalized to a wider rCDI population. Four studies were identified, and two were excluded due to potential for bias in estimating rCDI-attributable hospitalization LOS or cost based on the study design or data source (Aitken et al. 2014 and Zhang et al. 2018) [19, 34]. The sensitivity analyses included alternative rCDI-attributable hospitalization LOS and cost inputs reported in two studies: Shah et al. 2016 and Dubberke et al. 2014 [33, 40]. The sensitivity analysis results varied from $55,309 to $63,491 (sensitivity analysis 2: Dubberke et al. 2014) and $65,543–$79,658 (sensitivity analysis 1: Shah et al. 2016), supporting the high burden of rCDI and demonstrating that our results were sensitive to the hospitalization assumptions [33, 40]. Collectively, our cost estimation findings from the base-case and sensitivity analyses highlight the importance and urgency of understanding the broad economic burden of recurrent CDI and provide a benchmark for assessing the economic benefit of novel treatments to prevent and reduce recurrence in CDI.

Several limitations should be noted when interpreting the findings of the component-based synthesis cost analysis. Firstly, the results reflect the patient populations, study design, and limitations of the underlying source publications reporting on the economic burden of rCDI. For example, the recommendations on antibiotic treatment for primary CDI and the first and subsequent rCDI have evolved. In the 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), vancomycin or fidaxomicin were recommended for initial CDI episodes, whereas in their 2021 update, fidaxomicin is the preferred first-line antibiotic over vancomycin, given the clinical benefits in reducing CDI recurrences found with fidaxomicin [4, 52, 53]. Evolution of treatment options and recommendations over time would impact treatment patterns and subsequently the associated HRU cost in the care settings reported in our analysis. Due to the complexity of the disease, all-cause costs and HRU were not surprisingly more frequently reported than rCDI-attributable costs or HRU. However, all-cause values may not correctly reflect the specific burden associated with rCDI. From our search, only one study (Rodrigues et al. 2017) reported annual rCDI-attributable costs [31]. This single-center study included a small sample size of 98 rCDI patients (any recurrence) treated at Partners HealthCare in 2013 who had a high number of comorbid conditions (mean CCI score of 8.6) and a mean age of 66.7 years [31]. These characteristics were consistent with rCDI patient profiles (older with multiple comorbidities) as observed in other large-scale studies (e.g., Nelson et al. 2021, Feuerstadt et al. 2022) [14, 22, 31]. However, this study likely underestimates the true rCDI disease burden, as it did not include post-acute care or terminal care costs, nor capture costs for patients who sought additional care outside of the Partners HealthCare network or dropped out of the network.

Secondly, all key HRU/cost elements of interest were not available from the SLR. Therefore, a supplemental search of publications in similar or general populations was conducted to complete the calculation. As an example, rCDI-attributable costs for outpatient visits were obtained from the Optum360 National Fee Analyzer [43]. Thirdly, most of the HRU data were from Rodrigues et al. (2017), which is the sole publication identified in the SLR reporting annual rCDI-attributable HRU estimates [31]. As noted above, the inpatient days per year is a key driver of the cost calculation. Uncertainty around this parameter was addressed in sensitivity analyses to inform potential alternative ranges of the estimated economic burden of rCDI. However, because the sensitivity analyses required extrapolation of findings from a < 1-year timeframe these studies may not be comprehensive in the evaluation; for example, there may be missing hospitalizations that occurred after their defined follow-up period. Using such data required assumptions of a constant rate of hospitalization to extrapolate to an annual value. Furthermore, one of the studies used in the sensitivity analyses defined rCDI-attributable hospital costs or HRU in relativity to experience of other patients (Dubberke 2014), so it could have underestimated the true medical costs to the payer due to the insufficiency in absolute cost values [33]. Finally, while Rodrigues et al. 2017 is based on data from 2013, it is among the most recent data of the studies (Shah et al. 2016: 2007–2013; Dubberke et al. 2014: 2003–2009) [31, 33, 40]. Studies of recent clinical practice with longer follow-up (1 year or longer) are warranted, as well as research on rCDI-attributable cost burden directly on patients (e.g., out of pocket expenses, burden on caregivers).

Conclusion

Our SLR study found a high economic burden of rCDI in the USA with currently available treatments, with much variability in study design, populations, and reporting approaches. We provided an estimate of the annual average per-patient rCDI-attributable medical costs to a third-party payer in the USA using a component-based cost synthesis approach and provided a benchmark for assessing the economic benefit of novel treatments to prevent and reduce recurrence in CDI. Given the high-cost burden for managing rCDI with current approaches, having an established annual per-patient disease-attributable medical costs under the current standard of care will help set an initial benchmark to inform the economic benefit of novel therapies for rCDI. Future research will be warranted to report on the real-world economic burden of rCDI and evaluate the impact when more novel and effective therapies become available for these patients.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This analysis was funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc. also funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Jonathan Salcedo, PhD, and Priscilla Lopez, PhD, who are employees of Analysis Group, Inc. Support for this assistance was funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Min Yang, Amy Guo, Viviana Garcia-Horton, and Marie Louise Edwards contributed to all aspects of this study, including study design, data extraction, analysis, visualization, and critical review, editing, and approval of the draft manuscript. All authors (Kelly R. Reveles, Min Yang, Viviana Garcia-Horton, Marie Louise Edwards, Amy Guo, Thomas Lodise, Markian Bochan, Glenn Tillotson, and Erik R. Dubberke) participated in the critical review, editing, and approval of the draft manuscript. All authors (Kelly R. Reveles, Min Yang, Viviana Garcia-Horton, Marie Louise Edwards, Amy Guo, Thomas Lodise, Markian Bochan, Glenn Tillotson, and Erik R. Dubberke) have reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript for submission.

Disclosures

Min Yang, Viviana Garcia-Horton, and Marie Louise Edwards are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for conducting this research. Kelly R. Reveles, Amy Guo, Thomas Lodise, Markian Bochan, Glenn Tillotson, and Erik R. Dubberke have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based upon previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

This article is based upon previously conducted studies, and all data are publicly available in the referenced publications.

Appendix

Two studies were not included for sensitivity analyses due to study design or a data source that may not fully reflect rCDI-attributable hospitalization HRU or cost; these were Aitken et al. 2014 (3-month follow-up), and Zhang et al. 2018 (6-month follow-up) [19, 34].

Aitken et al. 2014 was a prospective, single-center study of adult patients within 3 months following discharge from a CDI hospitalization at a tertiary care hospital between 2007 and 2012 [34]. The study identified patients with rCDI via follow-up phone call after a CDI hospitalization. The study was not included in the sensitivity analyses due to the potential for response bias of healthier patients who responded to this recruitment method. Further, it used a narrow definition of rCDI attributable as CDI in primary diagnosis position and positive stool test within 3 days of admission, which would miss instances of a secondary diagnosis.

Zhang et al. 2018 was a retrospective MarketScan claims database analysis of propensity-score-matched patients with CDI and CDI with at least one rCDI followed for 6 months from the earliest CDI diagnosis from 2010–2014 [19]. The MarketScan data included: (1) the Commercial Claims and Encounters database and (2) the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database. The study was not included in the sensitivity analyses as the database would not include claims where Medicare is the primary payer and covered all of the service. Given that 46.6% of the study population was aged over 65 years, a substantial number of claims for rCDI may have been missed.

References

- 1.Guh AY, Kutty PK. Clostridioides difficile infection. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):itc49–itc64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Park SO, Yeo I. Trends in Clostridioides difficile prevalence, mortality, severity, and age composition during 2003–2014, the national inpatient sample database in the US. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1851–1858. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2092893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emerging infections program, healthcare associated infections—community interface surveillance report, Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), 2019 [PDF – 10 Pages]. Access date August 11, 2022. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/pdf/cdiff/2019-CDI-Report-H.pdf].

- 4.Johnson S, Lavergne V, Skinner AM, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 focused update guidelines on management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(5):e1029–e1044. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825–834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leong C, Zelenitsky S. Treatment strategies for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(6):361–368. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v66i6.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornely OA, Miller MA, Louie TJ, Crook DW, Gorbach SL. Treatment of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: fidaxomicin versus vancomycin. Clinical infectious. 2012;55(Suppl 2(Suppl 2)):S154-S61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhang S, Palazuelos-Munoz S, Balsells EM, Nair H, Chit A, Kyaw MH. Cost of hospital management of Clostridium difficile infection in United States-a meta-analysis and modelling study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):447-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Feuerstadt P, Nelson WW, Drozd EM, et al. Mortality, health care use, and costs of Clostridioides difficile infections in older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(10):1721–8.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins RJ, Wilson RB. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: a narrative review. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2018;6(1):21–28. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 2009.

- 13.Cheng YW, Phelps E, Ganapini V, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and severe Clostridium difficile infection in solid organ transplant recipients: a multicenter experience. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(2):501–511. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feuerstadt P, Nelson WW, Teigland C, Dahdal DN. Clinical burden of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in the medicare population: a real-world claims analysis. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2022;2(1):e60. doi: 10.1017/ash.2022.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Jesdale WM, Tjia J, Lapane K. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection among Medicare patients in nursing homes: a population-based cohort study. Med (Baltim) 2017;96(10):e6231. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin A, Teigland C, Mohammadi I, Murunga A, Schablik J, Guo A. Contemporary unmet needs and mortality in recurring Clostridium difficile patients [Poster] Chicago: Academy of Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin A, Guo A, Teigland C, Mohammadi I, Schablik J, Reveles K. Contemporary total cost of care among medicare patients with primary and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection [Poster] Washington, D. C.: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unni S, Scott T, Boules M, Teigland C, Parente A, Nelson W. Healthcare Burden and costs of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in the medicare population [Poster]. Academy of Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy, Houston. 2020

- 19.Zhang D, Prabhu VS, Marcella SW. Attributable healthcare resource utilization and costs for patients with primary and recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(9):1326–1332. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feuerstadt P, Stong L, Dahdal DN, Sacks N, Lang K, Nelson WW. Healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs associated with index and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: a real-world data analysis. J Med Econ. 2020;23(6):603–609. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1724117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feuerstadt P, Boules M, Stong L, et al. Clinical complications in patients with primary and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: a real-world data analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:2050312120986733. doi: 10.1177/2050312120986733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson WW, Scott TA, Boules M, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in the elderly: a real-world claims analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(7):828–838. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2021.20395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma S, Weissman S, Walradt T, et al. Readmission, healthcare consumption, and mortality in Clostridioides difficile infection hospitalizations: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(12):2629–2635. doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-04001-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Marcella S, Hawkshead JJ, 3rd, Shorr AF. Hospital readmission with Clostridium difficile infection as a secondary diagnosis is associated with worsened outcomes and greater revenue loss relative to principal diagnosis: a retrospective cohort study. Med (Baltim) 2018;97(36):e12212. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reveles KR, Dotson KM, Gonzales-Luna A, et al. Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile infection during hospitalization increases the likelihood of nonhome patient discharge. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(11):1887–1893. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruger AJ, Durkin C, Mumtaz K, Hinton A, Krishna SG. Early readmission predicts increased mortality in cirrhosis patients after Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53(8):e322–e327. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuntz JL, Baker JM, Kipnis P, et al. Utilization of health services among adults with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a 12-year population-based study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(1):45–52. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razik R, Rumman A, Bahreini Z, McGeer A, Nguyen GC. Recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the recidivism study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1141–1146. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haran JP, Bradley E, Howe E, Wu X, Tjia J. Medication exposure and risk of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in community-dwelling older people and nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):333–338. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meighani A, Hart BR, Bourgi K, Miller N, John A, Ramesh M. Outcomes of fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(10):2870–2875. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4580-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigues R, Barber GE, Ananthakrishnan AN. A comprehensive study of costs associated with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(2):196–202. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jasiak NM, Alaniz C, Rao K, Veltman K, Nagel JL. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in intensive care unit patients. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubberke ER, Schaefer E, Reske KA, Zilberberg M, Hollenbeak CS, Olsen MA. Attributable inpatient costs of recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(11):1400–1407. doi: 10.1086/678428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aitken SL, Joseph TB, Shah DN, et al. Healthcare resource utilization for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in a large university hospital in Houston, Texas. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(5):761–767. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venugopal AA, Riederer K, Patel SM, et al. Lack of association of outcomes with treatment duration and microbiologic susceptibility data in Clostridium difficile infections in a non-NAP1/BI/027 setting. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44(4):243–249. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.631029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tariq R, Saha S, Solanky D, Pardi DS, Khanna S. Predictors and management of failed fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(6):542–547. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadeghi K, Downham G, Nhan E, Reilly J, Kardos A. Multiple recurrent Clostridiodes difficile infections: an evaluation of patient cases and economic impact at a community teaching hospital [Poster]. AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center, Atlantic City. 2022.

- 39.Sadeghi K, Downham G, Nhan E, Reilly J, Kardos A. Multiple recurrent Clostridiodes difficile infections: an evaluation of patient cases and economic impact at a community teaching hospital [Poster]. AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center, Atlantic City 2022

- 40.Shah DN, Aitken SL, Barragan LF, et al. Economic burden of primary compared with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized patients: a prospective cohort study. J Hosp Infect. 2016;93(3):286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, et al. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Essrani R, Saturno D, Mehershahi S, et al. The impact of appendectomy in Clostridium difficile infection and length of hospital stay. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10342. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashraf MF, Tageldin O, Nassar Y, Batool A. Fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a four-year single-center retrospective review. Gastroenterol Res. 2021;14(4):237–243. doi: 10.14740/gr1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.HCUPnet. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, 2006–2009. Access date December 20, 2022.; [Available from: https://datatools.ahrq.gov/hcupnet]. [PubMed]

- 45.Halpern NA, Goldman DA, Tan KS, Pastores SM. Trends in critical care beds and use among population groups and medicare and medicaid beneficiaries in the United States: 2000–2010. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1490–1499. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Optum360. National Fee Analyzer. Access date December 20, 2022. [Available from: https://www.optumcoding.com/].

- 47.Wilson MZ, Hollenbeak CS, Stewart DB. Impact of Clostridium difficile colitis following closure of a diverting loop ileostomy: results of a matched cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(8):974–981. doi: 10.1111/codi.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neal MD, Alverdy JC, Hall DE, Simmons RL, Zuckerbraun BS. Diverting loop ileostomy and colonic lavage: an alternative to total abdominal colectomy for the treatment of severe, complicated Clostridium difficile associated disease. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):423–7; discussion 7–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Byhoff E, Harris JA, Ayanian JZ. Characteristics of decedents in medicare advantage and traditional medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):1020–1023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olsen MA, Stwalley D, Demont C, Dubberke ER. Clostridium difficile infection increases acute and chronic morbidity and mortality. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(1):65–71. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malone D, Armstrong E, Pham S, Gratie D, Amin A. EE429 a systematic review of healthcare resource use and costs of the treatment of Clostridioides difficile infections. Value Health. 2022;25(7):S419. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.04.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the infectious diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):e1–e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang Y, Sarpong EM, Sears P, Obi EN. Budget impact analysis of fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for the treatment of Clostridioides difficile infection in the United States. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11(1):111–126. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article is based upon previously conducted studies, and all data are publicly available in the referenced publications.