Abstract

Introduction

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of biologics in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma have shown differential results by baseline blood eosinophil count (BEC). In the absence of head-to-head trials, we describe the effects of biologics on annualized asthma exacerbation rate (AAER) by baseline BEC in placebo-controlled RCTs. Exacerbations associated with hospitalization or an emergency room visit, pre-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s, Asthma Control Questionnaire score, and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score were also summarized.

Methods

MEDLINE (via PubMed) was searched for RCTs of biologics in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma and with AAER reduction as a primary or secondary endpoint. AAER ratios and change from baseline in other outcomes versus placebo were compared across baseline BEC subgroups. Analysis was limited to US Food and Drug Administration-approved biologics.

Results

In patients with baseline BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL, AAER reduction was demonstrated with all biologics, and other outcomes were generally improved. In patients with BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL, consistent AAER reduction was demonstrated only with tezepelumab; improvements in other outcomes were inconsistent across biologics. In patients with BEC 150 to < 300 cells/μL, consistent AAER reduction was demonstrated with tezepelumab and dupilumab (300 mg dose only), and in those with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL, AAER reduction was demonstrated only with tezepelumab.

Conclusion

The efficacy of all biologics in reducing AAER in patients with severe asthma increases with higher baseline BEC, with varying profiles across individual biologics likely due to differing mechanisms of action.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02514-0.

Keywords: Biologic, Blood eosinophil, Efficacy, Exacerbations, Randomized placebo-controlled trial, Severe asthma, Systematic review

Key Summary Points

| Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of biologics in patients with severe asthma have demonstrated that efficacy varies according to blood eosinophil count (BEC), with increased efficacy demonstrated in patients with high baseline BECs and reduced or no efficacy demonstrated in those with low baseline BECs. |

| In the absence of head-to-head trials, a systematic literature review was conducted to describe the effects of biologics on the annualized asthma exacerbation rate (AAER) by baseline BEC in placebo-controlled RCTs. |

| The efficacy of biologics in reducing AAER in patients with severe asthma increases with higher baseline BEC; efficacy profiles varied between individual biologics, likely due to differing mechanisms of action. |

| These results may help clinicians to compare efficacy data across biologics for severe asthma. |

Introduction

Severe asthma that remains uncontrolled despite maximal use of controller medications and treatment of modifiable risk factors poses a significant health and economic burden to patients and society [1]. Controller medications for severe asthma recommended by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy document are high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), for which the daily dosage varies according to patient age, plus a long-acting β2 agonist [2]. A long-acting muscarinic antagonist may also be prescribed in patients over 12 years of age as an additional inhaled controller [2]. Some patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma may be prescribed maintenance oral corticosteroids (OCS); however, these are associated with side effects such as hypertension, bone fractures, and diabetes [3, 4]. As a result, GINA guidance recommends that maintenance OCS are prescribed at a low dose and as short term as possible to reduce the risk of serious side effects [2]. Biologic therapies are recommended at GINA step 5 as an adjunctive treatment in eligible patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who require additional therapies to high-dose maintenance ICS and other controller medications to prevent exacerbations and control symptoms [2].

Biologic therapies for severe asthma are monoclonal antibodies that specifically inhibit molecular targets involved in asthma inflammation to improve disease control [5]. Examples of biologics that have been well studied in patients with severe asthma include omalizumab (anti-immunoglobulin E), mepolizumab and reslizumab [both anti-interleukin (IL)-5], benralizumab (anti-IL-5 receptor), dupilumab (anti-IL-4 receptor), and tezepelumab [anti-thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)] [2]. The majority of these biologics target type 2 (T2) inflammatory pathways, whereas tezepelumab targets TSLP, which has been shown to play a role in T2 inflammation and other disease pathways [6].

For all biologics, differential efficacy has been shown based on patients’ baseline blood eosinophil count (BEC), with increased efficacy in patients with high baseline BEC and reduced or no efficacy in patients with low baseline BEC [7–11]. However, these data have not been comprehensively summarized across the relevant clinical trials. Additionally, to date, there have been no randomized, head-to-head trials comparing different biologics to allow direct comparisons. In the absence of such trials, and to contextualize the observed results across biologics by baseline BEC, we sought to systematically and quantitatively summarize biologic efficacy in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma as a function of baseline BEC. Our primary focus was the endpoint of asthma exacerbation rate reduction.

Methods

Literature Search

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. We performed a comprehensive search of MEDLINE (via PubMed) on 27 May 2021, using a search string containing terms related to severe, uncontrolled asthma, as well as biologic therapies, eosinophils, and clinical outcomes (Table S1). There were no publication date or language restrictions. Two reviewers independently screened the results based on the titles and abstracts, and then assessed the eligibility of the records according to specific inclusion criteria. A search of www.clinicaltrials.gov was also performed to find any additional unpublished trial data from studies identified in the literature search.

Inclusion Criteria

We included peer-reviewed publications reporting placebo-controlled RCTs of biologic therapies in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma with a primary or secondary endpoint of annualized asthma exacerbation rate reduction. The definition of severe asthma had to be consistent with the GINA 2020 guidelines (i.e., receipt of medium- to high-dose ICS with additional controllers) [13]. Eligible publications reported data for asthma exacerbation rate or other secondary outcomes of interest as a function of baseline BEC for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved biologics and their approved doses or bioequivalents; tezepelumab was also included because phase 3 trials were completed and FDA approval was anticipated at the time of the literature search (FDA approval was granted on 17 December 2021). When available to the authors, unpublished data from studies identified in the systematic search were included if they enabled comparison with published data from other studies. This included results posted on www.clinicaltrials.gov and unpublished trial data for tezepelumab. To enhance comparability with the BEC subgroup data obtained from other studies, we report subgroup data from PATHWAY for the common BEC thresholds of 150, 300, and 450 cells/μL rather than the original published subgroups based on BEC thresholds of 250 and 400 cells/μL [14].

The purpose of this review was to aggregate and summarize published RCT efficacy data across the biologics studied. Indirect treatment comparisons, meta-analyses, congress materials, real-world safety studies, open-label extension studies, OCS reduction trials, and data for non-FDA approved doses or biologics for which development has been discontinued were excluded. Studies of mild or moderate asthma populations (i.e., those not receiving medium- to high-dose ICS with additional controllers) were also excluded from this review, as were studies conducted solely in OCS-dependent patients, given that this patient population has a unique biology and that maintenance OCS use affects BEC [15] (i.e., the analysis by BEC category would be skewed). Racial/ethnic subgroup analyses were also out of scope for this review.

Data Extraction and Summary

Data were extracted from eligible sources into a standardized data extraction table by one reviewer, and the second reviewer verified the entry of data into the table. The data extracted were study design details, baseline characteristics of the overall study population, and any BEC subgroup data for the primary outcome of interest [annualized asthma exacerbation rate (AAER) ratio versus placebo] and for all secondary outcomes reported (as rate ratio versus placebo, change from baseline versus placebo, or responder rates, as appropriate). When summarizing the data, demonstration of efficacy in AAER reduction or improvement in other outcomes with a given biologic was determined based on the reported 95% confidence interval (CI) for the estimated rate ratio, or change from baseline with treatment versus placebo; p values were not used because they were not reported consistently. For example, for the AAER ratio, the 95% CI for the BEC subgroup estimate for active versus placebo must have been below 1 to demonstrate efficacy in reducing exacerbations. For a given BEC subgroup, wherever available, reported data from single trials and single doses are presented in preference to pooled data (trials or doses). Additionally, to avoid redundancy or conflict within results, data from a single trial were not reported more than once within any specific BEC subgroup.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration's revised tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials [16, 17] was applied to the included publications (specifically, to the BEC subgroup AAER data extracted from that publication or, if the AAER was not reported, to the trial’s primary outcome data that were extracted for BEC subgroups). The tool assessed the risk of bias arising from the following sources: the randomization process; deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention); missing outcome data; measurement of the outcome; and selection of the reported result.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Literature Search, Screening, and Selection

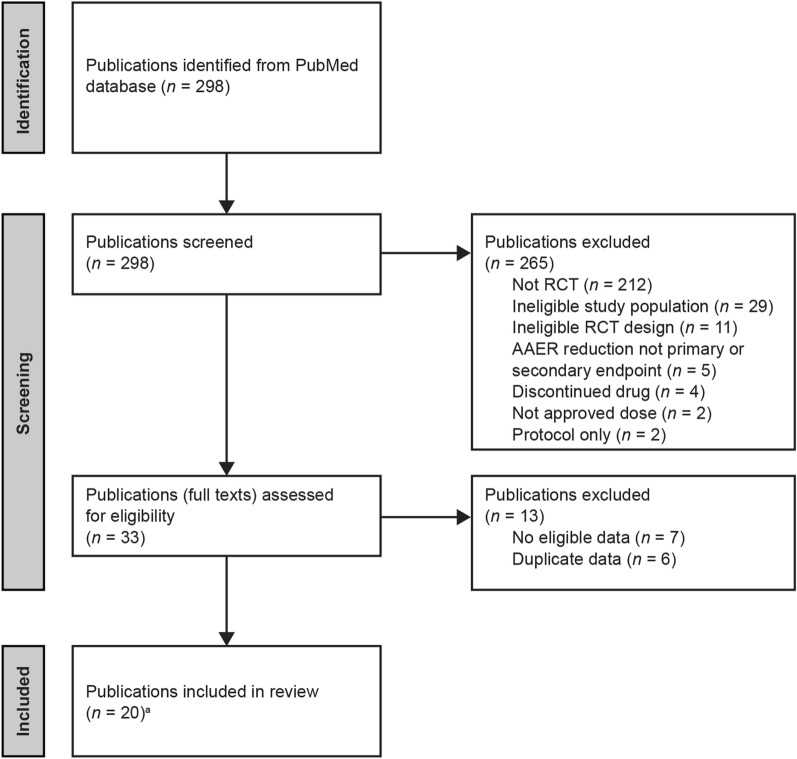

The MEDLINE literature search identified 298 results (Fig. 1; Table S2). Of these, 265 were excluded, the majority because they did not report RCTs (212 records). A further 29 and 11 were excluded for ineligible study population and ineligible RCT design, respectively. In addition, five publications did not have AAER reduction as a primary or secondary endpoint, four publications reported a discontinued drug, two reported only non-approved doses, and two reported study protocols only. Of the 33 remaining publications assessed in full, seven were excluded because no eligible data were presented and a further six were excluded because they reported data that were duplicated in publications already included. A final total of 20 publications met the inclusion criteria for the review, and all relevant data were extracted.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating publication selection process. aIncluding previously unpublished tezepelumab data, and dupilumab data posted on www.clinicaltrials.gov (see Table 1 for details). AAER annualized asthma exacerbation rate, PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, RCT randomized controlled trial

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Characteristics of the included studies and analyses are summarized in Table 1. Tezepelumab studies were the NAVIGATOR phase 3 and PATHWAY phase 2b trials, with data coming from two publications plus unpublished data [9, 14]. Dupilumab studies were the LIBERTY ASTHMA QUEST phase 3 trial and a phase 2b trial, with data coming from three publications and www.clinicaltrials.gov [10, 18–20]. Benralizumab studies were the ANDHI, SIROCCO, and CALIMA phase 3 trials, with data coming from seven publications [7, 21–26]. Reslizumab studies were two phase 3 trials and a phase 2b trial, with data coming from two publications [27, 28]. Mepolizumab studies were the MENSA and MUSCA phase 3 trials and the DREAM phase 2b trial, with data coming from five publications [11, 29–32]. The only eligible omalizumab study was the EXTRA phase 3 trial, with data coming from one publication [8].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included trials and publications

| Drug | Trial name (NCT number) | Total study population, n | Age range, years | Interventiona | Treatment period | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tezepelumab | NAVIGATOR (NCT03347279) | 1059 | 12–80 | Tezepelumab 210 mg SC Q4W | 52 weeks | Menzies-Gow et al. [9] supplemented with unpublished data |

| PATHWAY phase 2b (NCT02054130) | 550 | 18–75 | Tezepelumab 210 mg SC Q4W | 52 weeks | Corren et al. [14] supplemented with unpublished data | |

| PATHWAY phase 2b and NAVIGATOR pooled (NCT03347279 and NCT02054130) | 1334 | 12–80 | Tezepelumab 210 mg SC Q4W | 52 weeks | Unpublished data | |

| Dupilumab | LIBERTY ASTHMA QUEST (NCT02414854) | 1902 | ≥ 12 |

Dupilumab 200 mg SC Q2W Dupilumab 300 mg SC Q2W |

52 weeks | Castro et al. [19] |

| Castro et al. [10] supplemented with data posted on www.clinicaltrials.gov [20] | ||||||

| Phase 2b trial (NCT01854047) | 776 | ≥ 18 |

Dupilumab 200 mg SC Q2W Dupilumab 300 mg SC Q2W |

24 weeks | Wenzel et al. [18] | |

| Benralizumab | ANDHI (NCT03170271) | 656 | 18–75 | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | 24 weeks | Harrison et al. [22] |

| SIROCCO and CALIMA pooled (NCT01928771 and NCT01914757) | 1537 (BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL), 1941 (BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL) | 12–75 | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | 48 weeks and 56 weeks | O'Quinn et al. [23] | |

| 2295 | 12–75 | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | 48 weeks and 56 weeks | FitzGerald et al. [24] | ||

| Bleecker et al. [25] | ||||||

| SIROCCO and CALIMA assessed separately (NCT01928771 and NCT01914757) | 1204 (SIROCCO), 1306 (CALIMA) | 12–75 | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | 48 weeks and 56 weeks | Goldman et al. [26] | |

| SIROCCO (NCT01928771) | 1204 | 12–75 | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | 48 weeks | Bleecker et al. [21] | |

| CALIMA (NCT01914757) | 1306 | 12–75 | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | 56 weeks | FitzGerald et al. [7] | |

| Reslizumab | Study 1 and Study 2 assessed separately (NCT01287039 and NCT01285323) | 489 (Study 1), 464 (Study 2) | 12–75 | Reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg IV Q4W | 52 weeks | Castro et al. [27] |

| Phase 2b trial (NCT00587288) | 106 | 18–75 | Reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg IV Q4W | 15 weeks | Castro et al. [28] | |

| Mepolizumab | MENSA and MUSCA assessed separately; pooled doses for MENSA (NCT01691521 and NCT02281318) | 576 (MENSA), 556 (MUSCA) | 12–82 |

Mepolizumab 75 mg IV Q4W Mepolizumab 100 mg SC Q4W |

24–52 weeks | Yancey et al. [32] |

| MUSCA (NCT02281318) | 551 | ≥ 12 | Mepolizumab 100 mg SC Q4W | 24 weeks | Chupp et al. [29] | |

| DREAM phase 2b and MENSA assessed separately; pooled doses for MENSA (NCT01000506 and NCT01691521) | 621 (DREAM), 576 (MENSA) | 12–82 |

Mepolizumab 75 mg IV Q4W Mepolizumab 100 mg SC Q4W |

32–52 weeks | Ortega et al. [11] | |

| MENSA (NCT01691521) | 576 | 12–82 |

Mepolizumab 75 mg IV Q4W Mepolizumab 100 mg SC Q4W |

32 weeks | Ortega et al. [30] | |

| DREAM phase 2b (NCT01000506) | 621 | 12–74 | Mepolizumab 75 mg IV Q4W | 52 weeks | Pavord et al. [31] | |

| Omalizumab | EXTRA (NCT00314574) | 850 | 12–75 | Minimum dose of 0.008 mg/kg/IgE [IU/mL] SC Q2W or 0.016 mg/kg/IgE [IU/mL] SC Q4W | 48 weeks | Hanania et al. [8] |

All data are from phase 3 trials unless otherwise specified

BEC blood eosinophil count, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, IgE immunoglobulin E, IV intravenous, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous

aExtracted data only (i.e., FDA-approved dose for each drug)

All efficacy outcome data for BEC subgroups contained in the records were extracted, although not all outcomes were consistently reported across studies. In addition to AAER, the outcomes most commonly reported for BEC subgroups were AAER for exacerbations that required hospitalization or an emergency room (ER) visit, and change from baseline in pre-bronchodilator (BD) forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) score, and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) score. Outcomes that were inconsistently reported included change from baseline in post-BD FEV1, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score, asthma symptom diary score, total asthma symptom score or asthma symptom utility index, short-acting β2 agonist use for symptom relief, fractional exhaled nitric oxide levels, and BEC.

To examine differences between the study populations and provide context for the AAER by BEC subgroup data, the mean number of exacerbations that patients experienced in the 12 months before study commencement, both in the overall population and by BEC subgroup where available, were also extracted from the included publications (Table 2). This number ranged from 1.9 to 3.0 exacerbations across the active and placebo groups of the overall study populations (1.7–3.8 exacerbations when considering BEC subgroups). Patients participating in trials of tezepelumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab generally had a higher mean number of exacerbations in the 12 months before study commencement than those participating in trials of dupilumab, reslizumab, and omalizumab. For the majority of studies, in the 12 months before study commencement and post-randomization in the placebo group, the rate of exacerbations was slightly higher among patients with baseline BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL than those with baseline BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL.

Table 2.

Exacerbations in the 12 months before study commencement and in placebo-treated patients during the studies

| Study | Intervention | Population | Exacerbations in 12 months before study, mean ± SD (n) | AAER during study, mean (95% CI) | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Placebo | Placebo | ||||

| NAVIGATOR | Tezepelumab 210 mg SC Q4W | Overall | 2.8 ± 1.4 (528) | 2.7 ± 1.4 (531) | 2.10 (1.84–2.39) | Menzies-Gow et al. [9] supplemented with unpublished data |

| BEC ≥ 450 cells/µL | 3.1 ± 1.8 (120) | 3.0 ± 1.6 (127) | 3.00 (2.34–3.84) | |||

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | 3.0 ± 1.7 (219) | 2.9 ± 1.5 (222) | 2.66 (2.19–3.23) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | 2.6 ± 1.2 (309) | 2.6 ± 1.2 (309) | 1.73 (1.46–2.05) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL | 2.9 ± 1.5 (390) | 2.8 ± 1.4 (393) | 2.24 (1.93–2.60) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 150 cells/µL | 2.6 ± 1.0 (138) | 2.6 ± 1.2 (138) | 1.70 (1.32–2.19) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 to < 300 cells/μL | 2.7 ± 1.3 (171) | 2.6 ± 1.3 (171) | 1.75 (1.40–2.19) | |||

| PATHWAY phase 2b | Tezepelumab 210 mg SC Q4W | Overall | 2.4 ± 1.2 (137) | 2.5 ± 1.2 (138) | 0.72 (0.61–0.86) | Corren et al. [14] supplemented with unpublished data |

| BEC ≥ 450 cells/µL | 2.6 ± 1.5 (53) | 2.6 ± 1.5 (55) | 0.82 (0.57–1.13) | |||

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | 2.5 ± 1.3 (84) | 2.5 ± 1.3 (82) | 0.65 (0.48–0.87) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | 2.4 ± 1.1 (86) | 2.4 ± 1.1 (85) | 0.80 (0.59–1.04) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL | 2.4 ± 1.2 (114) | 2.5 ± 1.3 (117) | 0.66 (0.52–0.84) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 150 cells/µL | 2.4 ± 1.4 (39) | 2.4 ± 1.2 (44) | 0.92 (0.61–1.32) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 to < 300 cells/μL | 2.3 ± 0.9 (56) | 2.4 ± 1.0 (58) | 0.68 (0.43–1.03) | |||

| LIBERTY ASTHMA QUEST | Dupilumab 200 mg SC Q2W | Overall | 2.07 ± 2.66 (631) | 2.07 ± 1.58 (317) | 0.87 (0.72–1.05) | Castro et al. [10] |

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | NR | NR | 1.08 (0.85–1.38) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | NR | NR | 0.68 (0.52–0.88) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL | NR | NR | 1.01 (0.81–1.25) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 150 cells/µL | NR | NR | 0.51 (0.35–0.76) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 to < 300 cells/μL | NR | NR | 0.87 (0.59–1.27) | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg SC Q2W | Overall | 2.02 ± 1.86 (633) | 2.31 ± 2.07 (321) | 0.97 (0.81–1.16) | ||

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | NR | NR | 1.24 (0.97–1.57) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | NR | NR | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL | NR | NR | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 150 cells/µL | NR | NR | 0.64 (0.45–0.93) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 to < 300 cells/μL | NR | NR | 0.84 (0.58–1.23) | |||

| Phase 2b trial | Dupilumab 200 mg SC Q2W | Overall | 1.85 ± 1.43 (150) | 2.27 ± 2.25 (158) | 0.90 (0.62–1.30) | Wenzel et al. [18] |

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | 2.08 ± 1.67 (65) | 2.41 ± 2.77 (68) | 1.04 (0.57–1.90) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | 1.67 ± 1.19 (85) | 2.17 ± 1.77 (90) | 0.78 (0.49–1.23) | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg SC Q2W | Overall | 2.37 ± 2.29 (157) | 2.27 ± 2.25 (158) | 0.90 (0.62–1.30) | ||

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | 2.83 ± 2.79 (64) | 2.41 ± 2.77 (68) | 1.04 (0.57–1.90) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | 2.05 ± 1.82 (93) | 2.17 ± 1.77 (90) | 0.78 (0.49–1.23) | |||

| SIROCCO | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | Overall | 2.8 ± 1.5 (398) | 3.0 ± 1.8 (407) | NR |

Goldman et al. [26] Bleecker et al. [21] |

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | 2.8 ± 1.5 (267) | 3.1 ± 2.0 (267) | 1.33 (1.12–1.58) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | 2.6 ± 1.3 (131) | 2.7 ± 1.5 (140) | 1.21 (0.96–1.52) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL | 2.9 ± 1.6 (325) | 3.1 ± 1.9 (306) | 1.50 (1.27–1.76) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 150 cells/µL | 2.4 ± 0.8 (48) | 2.7 ± 1.6 (74) | 1.34 (1.00–1.79) | |||

| CALIMA | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | Overall | 2.7 ± 1.4 (441) | 2.7 ± 1.6 (440) | NR |

Goldman et al. [26] FitzGerald et al. [7] |

| BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL | 2.7 ± 1.3 (239) | 2.8 ± 1.7 (248) | 0.93 (0.77–1.12) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 300 cells/µL | 2.7 ± 1.7 (125) | 2.7 ± 1.9 (122) | 1.21 (0.96–1.52) | |||

| BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL | 2.7 ± 1.2 (300) | 2.7 ± 1.5 (315) | 1.10 (0.94–1.28) | |||

| BEC 0 to < 150 cells/µL | 3.1 ± 2.4 (48) | 2.5 ± 1.3 (40) | 1.55 (1.06–2.28) | |||

| ANDHI | Benralizumab 30 mg SC Q8W | Overall (BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL) |

≤ 2: 206 (48%)a ≥ 3: 221 (52%)a |

≤ 2: 113 (49%)a ≥ 3: 116 (51%)a |

NR | Harrison et al. [22] |

| Study 1 | Reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg IV Q4W | Overall (BEC ≥ 400 cells/µL) | 1.9 ± 1.6 (245) | 2.1 ± 2.3 (244) | 1.80 (1.37–2.37) | Castro et al. [27] |

| Study 2 | Reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg IV Q4W | Overall (BEC ≥ 400 cells/µL) | 1.9 ± 1.6 (232) | 2.0 ± 1.8 (232) | 2.11 (1.33–3.37) | |

| Phase 2b trial | Reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg IV Q4W | Overall | NR | NR | NR | Castro et al. [28] |

| DREAM phase 2b | Mepolizumab 75 mg IV Q4W | Overall (BEC ≥ 300 cells/µL) | 3.7 ± 3.1 (153) | 3.7 ± 3.8 (155) | 2.40 (0.11b) | Pavord et al. [31] |

| MUSCA | Mepolizumab 100 mg SC Q4W | Overall (BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL) | 2.9 ± 1.9 (274) | 2.7 ± 1.5 (277) | 1.21 (NR) | Chupp et al. [29] |

| MENSA | Mepolizumab 75 mg IV Q4W | Overall (BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL) | 3.5 ± 2.2 (191) | 3.6 ± 2.8 (191) | 1.74 (NR) | Ortega et al. [30] |

| Mepolizumab 100 mg SC Q4W | Overall (BEC ≥ 150 cells/µL) | 3.8 ± 2.7 (194) | ||||

| EXTRA | Omalizumab 0.008 mg/kg/IgE (IU/mL) SC Q2W or 0.016 mg/kg/IgE (IU/mL) SC Q4W | Overall | 2.0 ± 2.2 (427) | 1.9 ± 1.5 (421) | 0.88 (NR) |

Hanania et al. [8] Hanania et al. [43] |

| BEC ≥ 260 cells/µL | 2 ± 2 (414) | 1.03 (NR) | ||||

| BEC < 260 cells/µL | 2 ± 1 (383) | 0.72 (NR) | ||||

All data are from phase 3 trials unless otherwise specified

AAER annualized asthma exacerbation rate, BEC blood eosinophil count, CI confidence interval, IgE immunoglobulin E, IV intravenous, NR not reported, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous, SD standard deviation, SE standard error

aMean (SD) not reported; n (%) of patients with ≤ 2 and ≥ 3 exacerbations, respectively, in the 12 months before the study are provided here

bSE log

Risk of Bias Assessment

Of the 20 included studies, 12 were assessed to have a low risk of bias (Fig. S1). In the remaining eight studies, there was some potential bias in the reported results because the BEC subgroup analyses were not pre-specified. In addition, one study examining the efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with baseline BEC of ≥ 150 to 300 cells/μL [32] was reported with insufficient detail to allow assessment of the appropriateness of the analysis used to estimate the effect of assignment to intervention (e.g., intention-to-treat or per protocol). There was little risk of bias arising from other aspects of the analyses in these eight studies.

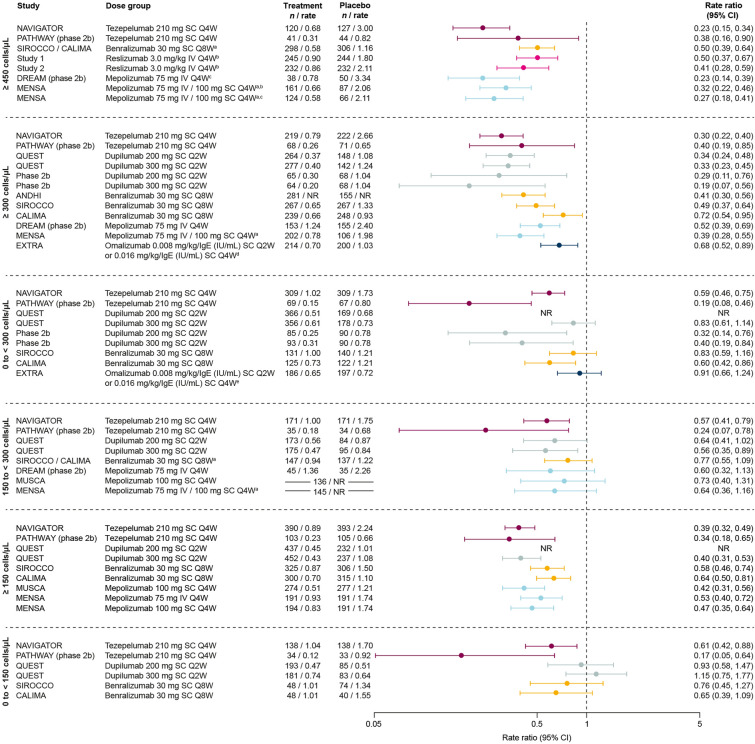

Exacerbations

In patients with baseline BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL, efficacy in AAER reduction versus placebo was demonstrated with all biologics in all trials for which this subgroup was reported (studies of tezepelumab, dupilumab, benralizumab, mepolizumab, and omalizumab) (Figs. 2, S2) [7–10, 14, 18, 21, 22, 31]. The greatest AAER reductions versus placebo (≥ 60%) were observed with dupilumab and tezepelumab [9, 10, 14, 18]. Similarly, reductions were demonstrated with all biologics in patients with baseline BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL where reported (studies of tezepelumab, dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab) [9, 10, 14, 26, 29, 30] and ≥ 450 cells/μL where reported (studies of tezepelumab, benralizumab, reslizumab, and mepolizumab) [9, 11, 14, 24, 27].

Fig. 2.

AAER by biologic therapy across baseline BEC subgroups. Data are phase 3 unless otherwise specified. In the 0 to < 300 cells/μL panel, QUEST data are from www.clinicaltrials.gov [20]; reported for the 300 mg dose only. Patient numbers for MUSCA and MENSA in the 150 to < 300 cells/μL panel are for the overall population (breakdown by treatment group not given). In the ≥ 150 cells/μL panel, MUSCA and MENSA data are for patients with BEC > 150 cells/μL at screening (rather than baseline). aPooled trials or doses; bBEC ≥ 400 cells/μL; cBEC ≥ 500 cells/μL; dBEC ≥ 260 cells/μL; eBEC < 260 cells/μL. AAER annualized asthma exacerbation rate, BEC blood eosinophil count, CI confidence interval, IgE immunoglobulin E, IV intravenous, NR not reported, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous

In patients with BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL, AAER reduction versus placebo was consistently demonstrated only with tezepelumab (in both NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY) [9, 14]. With benralizumab and dupilumab, AAER reduction was observed in one each of the two trials in which they were studied (CALIMA for benralizumab and the phase 2b study for dupilumab) [7, 18]. In patients with BEC 150 to < 300 cells/μL, AAER reduction was only demonstrated consistently with tezepelumab (NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY) [9, 14], although this outcome was also observed with dupilumab (QUEST 300 mg dose only) [10]. In patients with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL, AAER reduction was only demonstrated with tezepelumab (NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY) [9, 14].

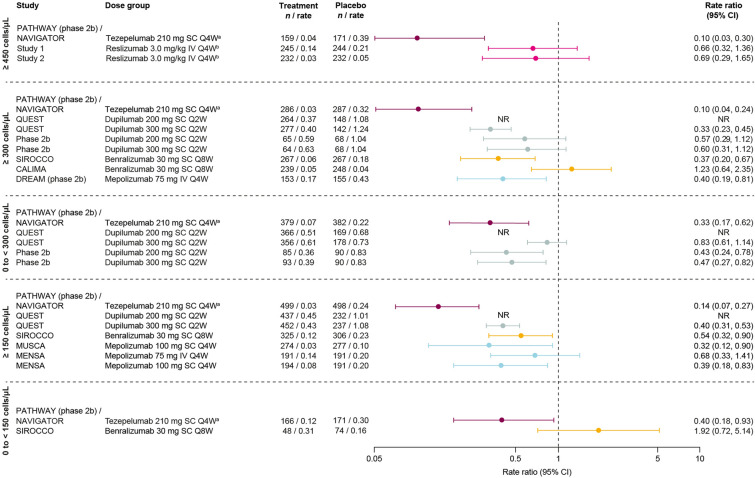

Exacerbations Requiring Hospitalization or an ER Visit

In patients with BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL, reductions in the annualized rate of exacerbations requiring hospitalization or an ER visit versus placebo were demonstrated with tezepelumab (pooled NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY), dupilumab (QUEST 300 mg dose only), benralizumab (SIROCCO), and mepolizumab (DREAM) (Fig. 3) [20, 21, 31]. In patients with BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL, a reduction was demonstrated across all trials for which this subgroup was reported, comprising studies of tezepelumab (pooled NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY), dupilumab (QUEST 300 mg dose), benralizumab (SIROCCO), and mepolizumab (MUSCA and MENSA, 100 mg subcutaneous arm only) [20, 26, 29, 30]. The greatest reductions in exacerbations requiring hospitalization or an ER visit in both the BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL and BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL subgroups were observed with tezepelumab, at 90% and 86%, respectively. Of the two biologics with data reported for patients with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL, a reduction was demonstrated only with tezepelumab (pooled NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY).

Fig. 3.

Exacerbations that required hospitalization or an ER visit by biologic therapy across baseline BEC subgroups. Data are phase 3 unless otherwise specified. QUEST data are from www.clinicaltrials.gov [20]. In the ≥ 150 cells/μL panel, MUSCA and MENSA data are for patients with BEC > 150 cells/μL at screening (rather than baseline). aPooled trials or doses; bBEC ≥ 400 cells/μL. BEC blood eosinophil count, CI confidence interval, ER emergency room, IV intravenous, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous

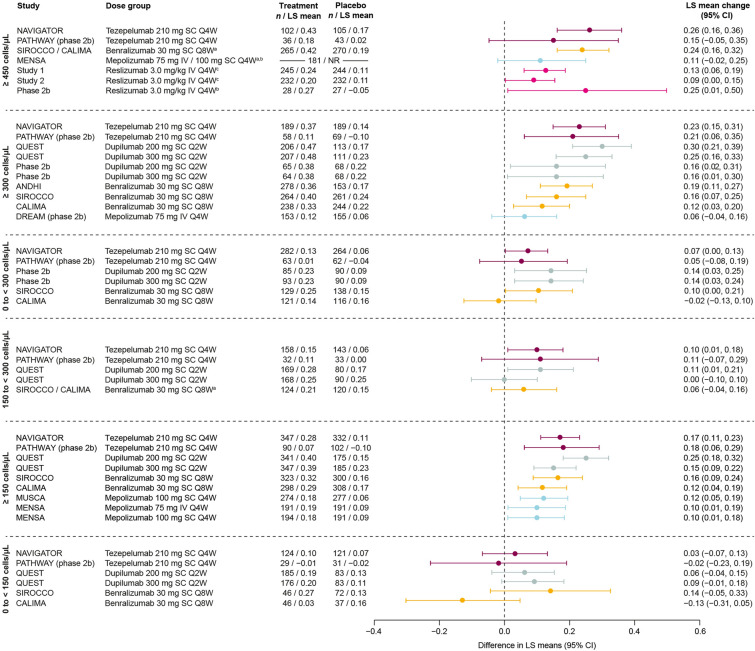

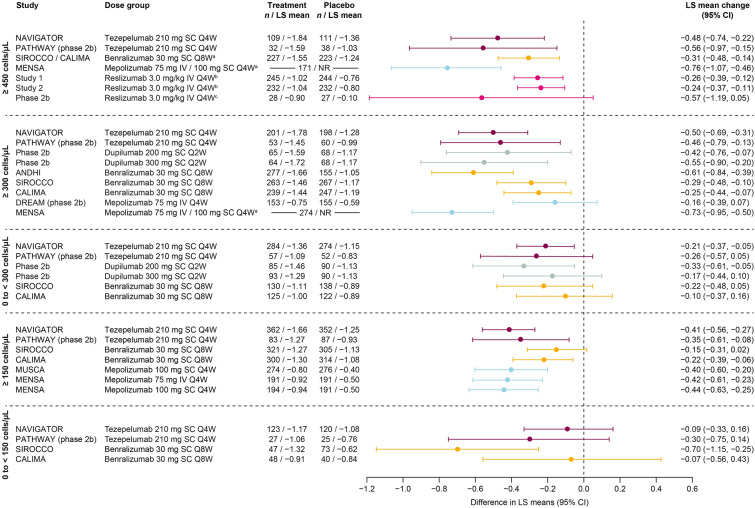

Pre-bronchodilator FEV1

Efficacy in improving pre-BD FEV1 versus placebo in patients with BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL or ≥ 150 cells/μL was demonstrated by all biologics across all trials that reported these subgroups (studies of tezepelumab, dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab), except for the BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL subgroup in DREAM (mepolizumab) (Fig. 4) [7, 9, 14, 18, 19, 21, 22, 26, 29–31]. Where data were available for patients with BEC ≥ 450 cells/μL, improvements were demonstrated in the majority of trials (studies of tezepelumab, benralizumab, and reslizumab) [9, 14, 27, 28].

Fig. 4.

Change from baseline versus placebo in pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (L) by biologic therapy across baseline BEC subgroups. Data are phase 3 unless otherwise specified. MENSA patient numbers are for the overall population (≥ 450 cells/μL panel). QUEST 200 mg and 300 mg data in the 150 to < 300 cells/μL and 0 to < 150 cells/μL panels are from study week 12. MUSCA and MENSA data in the BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL panel are from screening (rather than baseline). aPooled trials or doses; bBEC ≥ 500 cells/μL; cBEC ≥ 400 cells/μL. BEC blood eosinophil count, CI confidence interval, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, IV intravenous, LS least-squares, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous

Of studies that reported data from patients with BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL, tezepelumab, dupilumab, and benralizumab demonstrated efficacy in improving pre-BD FEV1 in one trial each (NAVIGATOR, dupilumab phase 2b, and SIROCCO, respectively) [9, 18, 21]. Improvements in patients with BEC 150 to < 300 cells/μL were observed in one trial each of tezepelumab (NAVIGATOR) and dupilumab (QUEST 200 mg dose only) [9, 10]. No biologic demonstrated a significant improvement compared with placebo in pre-BD FEV1 in patients with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL.

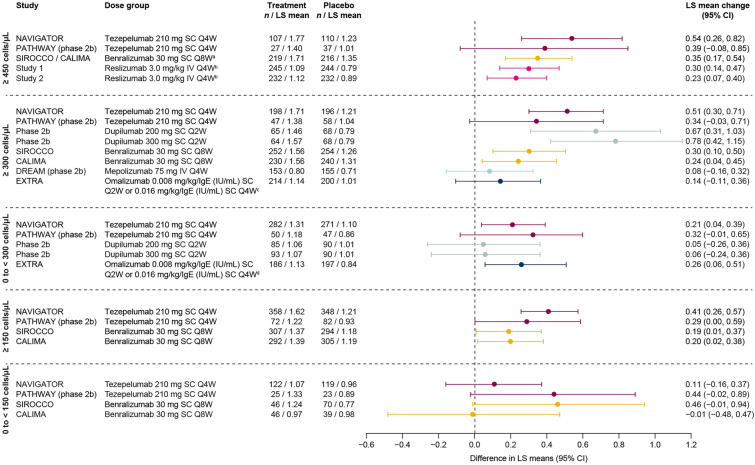

ACQ Score

Efficacy in improving ACQ score versus placebo in patients with BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL was demonstrated in all trials that reported this subgroup (studies of tezepelumab, dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab), with the exception of mepolizumab in DREAM (Fig. 5) [7, 9, 11, 14, 18, 21, 22, 31]. The greatest improvements (> 0.4-point improvement in mean score versus placebo) were observed with tezepelumab, dupilumab, benralizumab (ANDHI), and mepolizumab (MENSA) [9, 11, 14, 18, 22]. Where data were available, improvements were also demonstrated in the majority of trials reporting BEC ≥ 450 cells/μL subgroup data (studies of tezepelumab, benralizumab, mepolizumab and reslizumab) [9, 11, 14, 24, 27, 28]. Improvements in ACQ score in patients with BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL were demonstrated in all but one trial [benralizumab (SIROCCO)] that reported this subgroup (studies of tezepelumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab) [9, 14, 26, 29, 30].

Fig. 5.

Change from baseline versus placebo in ACQ score by biologic therapy across baseline BEC subgroups. Data are phase 3 unless otherwise specified. Data are ACQ-6, except for: dupilumab phase 2b (ACQ-5); all reslizumab studies (ACQ-7); and mepolizumab MUSCA and MENSA (ACQ-5). PATHWAY data are from study week 50. In the ≥ 300 cells/μL panel, patient numbers for MENSA are the overall population. In the ≥ 150 cells/μL panel, MUSCA and MENSA data are for patients with BEC > 150 cells/μL at screening (rather than baseline). aPooled trials or doses; bBEC ≥ 400 cells/μL; cBEC ≥ 500 cells/μL. ACQ Asthma Control Questionnaire, BEC blood eosinophil count, CI confidence interval, IV intravenous, LS least-squares, NR not reported, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous

In trials reporting BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL subgroup data, tezepelumab and dupilumab (200 mg dose only) were the only biologics to demonstrate efficacy in improving ACQ scores, in one trial each (NAVIGATOR and dupilumab phase 2b, respectively) [9, 18]. In patients with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL, only benralizumab in the SIROCCO trial demonstrated efficacy in improving ACQ score [26].

AQLQ Score

In patients with BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL, efficacy in improving AQLQ score versus placebo was demonstrated with tezepelumab (NAVIGATOR), dupilumab (phase 2b), and benralizumab (SIROCCO and CALIMA) (Fig. 6) [7, 9, 18, 21]. In patients with BEC ≥ 450 cells/μL, improvements were observed with tezepelumab (NAVIGATOR), benralizumab (SIROCCO/CALIMA pooled), and reslizumab (phase 3 studies 1 and 2) [9, 24, 27]. AQLQ data for patients with BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL were reported only for trials of tezepelumab (NAVIGATOR and PATHWAY) and benralizumab (SIROCCO and CALIMA), with efficacy demonstrated in all of these studies [9, 14, 26].

Fig. 6.

Change from baseline versus placebo in AQLQ score by biologic therapy across baseline BEC subgroups. Data are phase 3 unless otherwise specified. PATHWAY data are from study week 48. aPooled trials or doses; bBEC ≥ 400 cells/μL; cBEC ≥ 260 cells/μL; dBEC < 260 cells/μL. AQLQ Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, BEC blood eosinophil count, CI confidence interval, IgE immunoglobulin E, IV intravenous, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q8W every 8 weeks, SC subcutaneous

AQLQ improvements in patients with BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL were demonstrated with tezepelumab in NAVIGATOR and with omalizumab in EXTRA [8, 27]. In patients with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL, no biologic demonstrated efficacy in improving AQLQ score.

Other Outcomes

Additional endpoints stratified by BEC subgroups were extracted for reference (summarized in Table S3). These include post-BD FEV1, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score, asthma symptom diary score, total asthma symptom score or asthma symptom utility index, short-acting β2 agonist use for symptom relief, fractional exhaled nitric oxide levels, and mean change in BEC.

Discussion

This systematic review of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial data evaluated the efficacy of biologics in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma grouped by baseline BEC. A clear association between efficacy in reducing exacerbations and baseline BEC was demonstrated for all biologics assessed. Although they all demonstrated efficacy versus placebo in patients with baseline BEC ≥ 150, ≥ 300, or ≥ 450 cells/μL, with a clinically meaningful reduction in AAER (i.e., ≥ 20%) [33], biologics other than tezepelumab either demonstrated inconsistent efficacy across studies or did not demonstrate efficacy in reducing exacerbations in patients with lower BEC (either 0 to < 300 cells/μL or 0 to < 150 cells/μL). The association between baseline BEC and efficacy in reducing exacerbations associated with hospitalization or an ER visit was not as clear, largely owing to limited data availability; however, efficacy was generally demonstrated in patients with baseline BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL or ≥ 300 cells/μL for those biologics with data available (studies of tezepelumab, dupilumab, benralizumab, and mepolizumab). Tezepelumab uniquely demonstrated efficacy in exacerbation reduction, overall and for those associated with hospitalization or an ER visit, in patients with BEC 0 to < 150 cells/μL.

The biologics studied all have different mechanisms of action. This fact underscores the importance of comparing results across their randomized, placebo-controlled studies, as providers must choose between biologics with different mechanisms to identify the biologic best suited for their patients. In fact, the differential efficacy of biologics in reducing exacerbations according to patients’ BEC is likely a result of mechanistic differences between the treatments and the resulting impact of these on airway inflammation and physiology. The majority of FDA-approved biologics for severe asthma target specific elements of T2 inflammatory pathways (immunoglobulin E, IL-5, IL-5 receptor, or IL-4 receptor) and thus predominantly benefit patient phenotypes characterized by high levels of T2 inflammation, including high BEC. Tezepelumab, however, targets TSLP, an epithelial cytokine that has been shown to play a role in processes broader than strictly T2 inflammation in asthma pathophysiology [34]. The efficacy of tezepelumab in patients with low T2 inflammation may relate to the observed reduction in airway hyperresponsiveness (a largely T2-independent mechanism) with tezepelumab treatment and effects on other potential mediators, such as mast cell activity [35–37].

With regard to efficacy in improving lung function, asthma symptom control, and asthma-related quality of life, improvements were generally demonstrated across biologics in patients with baseline BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL and ≥ 300 cells/μL. In those with BEC 0 to < 300 cells/μL or 0 to < 150 cells/μL, inconsistent, reduced, or no efficacy in improving these outcomes was observed across biologics. In contrast to the mechanisms relevant to reducing asthma exacerbations, biologic mechanisms related to improvement of these secondary clinical trial endpoints of lung function and asthma symptoms may be more directly associated with T2 airway inflammation, given the similar results seen across biologics regardless of their mechanism. T2 inflammatory processes relevant to these clinical features include airway edema (secondary to inflammation), overproduction of airway mucus (driven by IL-13 activity), and airway mucus plugging (from IL-13 driven mucus production and IL-5 driven eosinophil recruitment and activation) [38–40]. Additionally, IL-13 can have a direct effect on airway smooth muscle tone [41, 42].

A primary limitation of this review is that the data are from different studies with different patient populations. For example, inclusion of adolescent patients, the specific dosage of ICS required for enrollment, inclusion of patients receiving daily OCS, study duration, and enrollment stratification methodologies varied across studies. We restricted the included studies to RCTs in severe, uncontrolled asthma with exacerbation rate reduction as the primary or a secondary endpoint, in an attempt to obtain the most analogous data for the different biologics. We could not address the effects of study design differences in the current analysis, which was limited to published data. Given the differences across studies, comparisons are most robust between subgroups within a single study. Comparisons across studies are most valuable in describing what evidence exists and in which groups efficacy has been observed. Several of the subgroups reported are overlapping (e.g., BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL and BEC 150 to < 300 cells/μL), as we chose to report all available information for transparency and to avoid bias from prioritizing some subgroups over others. In the case of overlapping subgroups, the more specific subgroups are the most informative, because results from larger subgroups can obscure differences within the subgroup; for example, lower efficacy among patients with BEC 150 to < 300 cells/μL will not be perceptible in an analysis of patients with BEC ≥ 150 cells/μL where efficacy among patients with BEC ≥ 300 cells/μL is averaged with efficacy among patients with BEC 150 to < 300 cells/μL. Another limitation of our review is that many of the included studies were not prospectively powered for eosinophil subgroup analyses. Regarding minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs), this review acknowledges the available literature regarding the MCID for AAER reduction, which was the primary endpoint of interest. However, for the secondary outcomes of pre-BD FEV1, ACQ, and AQLQ, the MCIDs are validated to be applied at the patient level for the change over time, and are best summarized in a population as the proportion achieving the MCID threshold response. The MCIDs for these outcomes are not validated to be applied to population mean responses with treatment versus placebo, which is how results are reported for randomized clinical trials and thus in this review. For this reason, our review does not discuss MCIDs for secondary outcomes. Lastly, data availability was a further issue, particularly for outcomes other than AAER, for which limited data were published for some BEC subgroups.

Conclusion

This systematic review of RCTs demonstrates that the efficacy of biologics in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma in reducing exacerbations and improving lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life varies with baseline BEC. This differential efficacy was most pronounced for biologics targeting T2 inflammatory pathways (eosinophilic and/or allergic inflammation). All biologics generally demonstrated efficacy in reducing exacerbations and improving other outcomes in patients with baseline BEC ≥ 150, ≥ 300, or ≥ 450 cells/μL. However, efficacy was not generally observed in patients with baseline BEC 0 to < 300, 150 to < 300, or 0 to < 150 cells/μL. Tezepelumab was the only biologic to consistently demonstrate efficacy in lower BEC subgroups.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of J. Mark FitzGerald, MD, MB, FCCP, FRCPI, FRCPC, to the conception and development of this manuscript. Dr FitzGerald passed away before the manuscript was finalized.

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by AstraZeneca, Wilmington, DE, USA, and Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Richard Claes, PhD, of PharmaGenesis London, London, UK, with funding from AstraZeneca and Amgen Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Stephanie Korn, Bill Cook, Lisa J. Simpson, Jean-Pierre Llanos, and Christopher S. Ambrose significantly contributed to development of the search string and manuscript content, and critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript. Lisa J. Simpson completed the literature search, article screen, and data extraction. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Prior Presentation

Findings from this systematic review were previously presented in a poster at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting, 4–8 November 2021; New Orleans, LA, USA.

Disclosures

Stephanie Korn has received fees for lectures and/or advisory board meetings from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. Bill Cook and Christopher S. Ambrose are employees of AstraZeneca and may own stock or stock options in AstraZeneca. Lisa J. Simpson is an employee of PharmaGenesis London, a HealthScience communications consultancy. Jean-Pierre Llanos is an employee of Amgen and owns stock in Amgen.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included as supplementary information files.

References

- 1.Asthma UK. Severe asthma: the unmet need and the global challenge. 2017. https://www.asthma.org.uk/globalassets/get-involved/external-affairs-campaigns/publications/severe-asthma-report/auk_severeasthma_2017.pdf. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

- 2.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention 2022. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

- 3.Volmer T, Effenberger T, Trautner C, Buhl R. Consequences of long-term oral corticosteroid therapy and its side-effects in severe asthma in adults: a focused review of the impact data in the literature. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800703. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00703-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdin A, Molinari N, Vachier I, Pahus L, Suehs C, Chanez P. Mortality: a neglected outcome in OCS-treated severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1701486. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01486-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agache I, Beltran J, Akdis C, Akdis M, Canelo-Aybar C, Canonica GW, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with biologicals (benralizumab, dupilumab, mepolizumab, omalizumab and reslizumab) for severe eosinophilic asthma. A systematic review for the EAACI Guidelines - recommendations on the use of biologicals in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020;75:1023–1042. doi: 10.1111/all.14221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauvreau GM, Sehmi R, Ambrose CS, Griffiths JM. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: its role and potential as a therapeutic target in asthma. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020;24:777–792. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1783242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, Korn S, Ohta K, Lommatzsch M, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2128–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanania NA, Wenzel S, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ, Mosesova S, Choy DF, et al. Exploring the effects of omalizumab in allergic asthma: an analysis of biomarkers in the EXTRA study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:804–811. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1414OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menzies-Gow A, Corren J, Bourdin A, Chupp G, Israel E, Wechsler ME, et al. Tezepelumab in adults and adolescents with severe, uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1800–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, Maspero J, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2486–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortega HG, Yancey SW, Mayer B, Gunsoy NB, Keene ON, Bleecker ER, et al. Severe eosinophilic asthma treated with mepolizumab stratified by baseline eosinophil thresholds: a secondary analysis of the DREAM and MENSA studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:549–556. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PRISMA guidelines. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 2020. http://www.prisma-statement.org/. Accessed 29 July 2021.

- 13.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention 2020. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GINA-2020-full-report_-final-_wms.pdf. Accessed 26 July 2021.

- 14.Corren J, Parnes JR, Wang L, Mo M, Roseti SL, Griffiths JM, et al. Tezepelumab in adults with uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:936–946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prazma CM, Bel EH, Price RG, Bradford ES, Albers FC, Yancey SW. Oral corticosteroid dose changes and impact on peripheral blood eosinophil counts in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma: a post hoc analysis. Respir Res. 2019;20:83. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1056-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, Maspero J, Wang L, Zhang B, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting beta2 agonist: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2b dose-ranging trial. Lancet. 2016;388:31–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro M, Rabe KF, Corren J, Pavord ID, Katelaris CH, Tohda Y, et al. Dupilumab improves lung function in patients with uncontrolled, moderate-to-severe asthma. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00204-2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00204-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ClinicalTrials.gov. Evaluation of dupilumab in patients with persistent asthma: LIBERTY ASTHMA QUEST (study results data). https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Accessed 29 July 2021.

- 21.Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, Papi A, Weinstein SF, Barker P, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison TW, Chanez P, Menzella F, Canonica GW, Louis R, Cosio BG, et al. Onset of effect and impact on health-related quality of life, exacerbation rate, lung function, and nasal polyposis symptoms for patients with severe eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (ANDHI): a randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:260–274. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Quinn S, Xu X, Hirsch I. Daily patient-reported health status assessment improvements with benralizumab for patients with severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2019;12:21–33. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S190221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Menzies-Gow A, Zangrilli JG, Hirsch I, Metcalfe P, et al. Predictors of enhanced response with benralizumab for patients with severe asthma: pooled analysis of the SIROCCO and CALIMA studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:51–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleecker ER, Wechsler ME, FitzGerald JM, Menzies-Gow A, Wu Y, Hirsch I, et al. Baseline patient factors impact on the clinical efficacy of benralizumab for severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800936. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00936-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldman M, Hirsch I, Zangrilli JG, Newbold P, Xu X. The association between blood eosinophil count and benralizumab efficacy for patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma: subanalyses of the Phase III SIROCCO and CALIMA studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1605–1613. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1347091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, Bateman ED, Brusselle GG, Bardin P, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, Boulet LP, Xie F, Young J, et al. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1125–1132. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0396OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chupp GL, Bradford ES, Albers FC, Bratton DJ, Wang-Jairaj J, Nelsen LM, et al. Efficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:390–400. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1198–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, Bleecker ER, Buhl R, Keene ON, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yancey SW, Bradford ES, Keene ON. Disease burden and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with severe asthma and blood eosinophil counts of ≥150–300 cells/µL. Respir Med. 2019;151:139–141. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonini M, Di Paolo M, Bagnasco D, Baiardini I, Braido F, Caminati M, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for asthma endpoints: an expert consensus report. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29:190137. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0137-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gauvreau GM, Sehmi R, Ambrose CS, Griffiths JM. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: its role and potential as a therapeutic target in asthma. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020;24:1–16. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1783242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diver S, Khalfaoui L, Emson C, Wenzel SE, Menzies-Gow A, Wechsler ME, et al. Effect of tezepelumab on airway inflammatory cells, remodelling, and hyperresponsiveness in patients with moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma (CASCADE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:1299–1312. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sverrild A, Hansen S, Hvidtfeldt M, Clausson CM, Cozzolino O, Cerps S, et al. The effect of tezepelumab on airway hyperresponsiveness to mannitol in asthma (UPSTREAM) Eur Respir J. 2022;59:2101296. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01296-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauvreau GM, O'Byrne PM, Boulet L-P, Wang Y, Cockcroft D, Bigler J, et al. Effects of an anti-TSLP antibody on allergen-induced asthmatic responses. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2102–2110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:57–65. doi: 10.1038/nri3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunican EM, Elicker BM, Gierada DS, Nagle SK, Schiebler ML, Newell JD, et al. Mucus plugs in patients with asthma linked to eosinophilia and airflow obstruction. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:997–1009. doi: 10.1172/JCI95693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H, Fahy JV. The cytokines of asthma. Immunity. 2019;50:975–991. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marone G, Granata F, Pucino V, Pecoraro A, Heffler E, Loffredo S, et al. The intriguing role of interleukin 13 in the pathophysiology of asthma. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1387. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao YD, Zou JJ, Zheng JW, Shang M, Chen X, Geng S, et al. Promoting effects of IL-13 on Ca2+ release and store-operated Ca2+ entry in airway smooth muscle cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanania NA, Alpan O, Hamilos DL, Condemi JJ, Reyes-Rivera I, Zhu J, et al. Omalizumab in severe allergic asthma inadequately controlled with standard therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:573–582. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included as supplementary information files.