Abstract

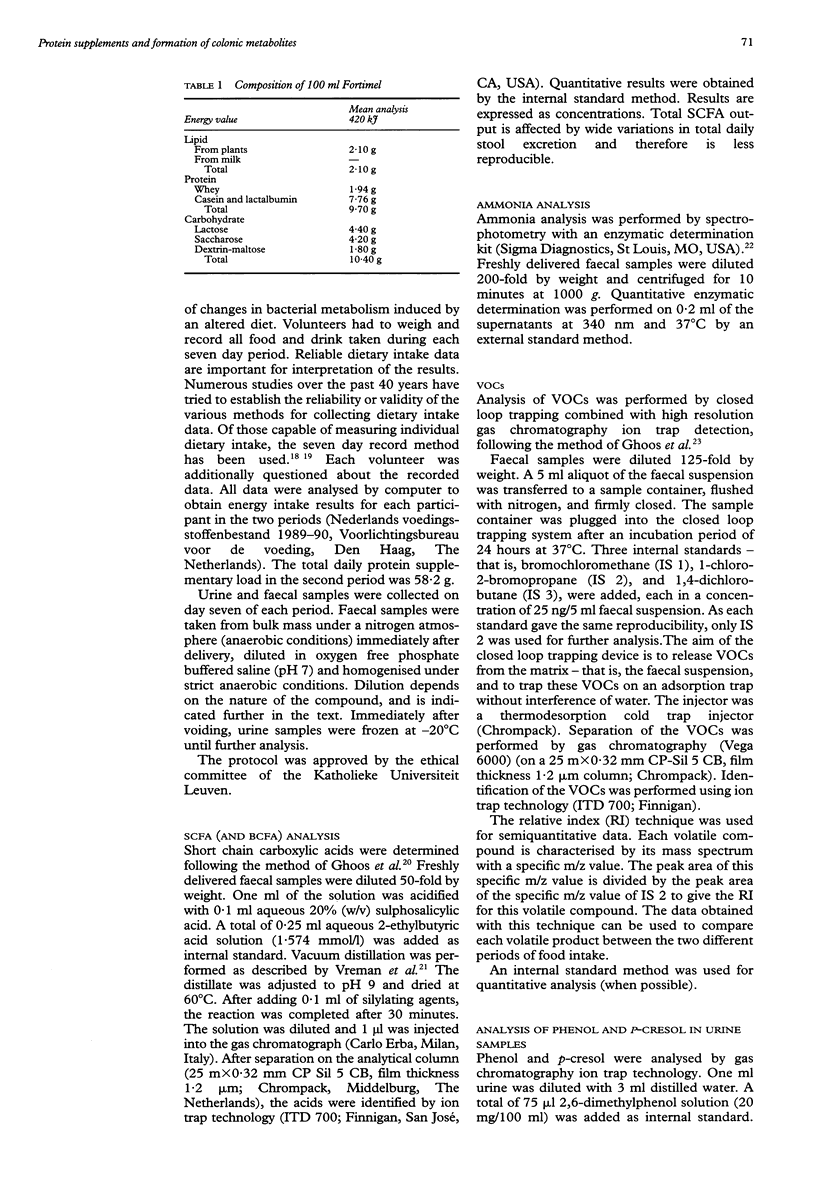

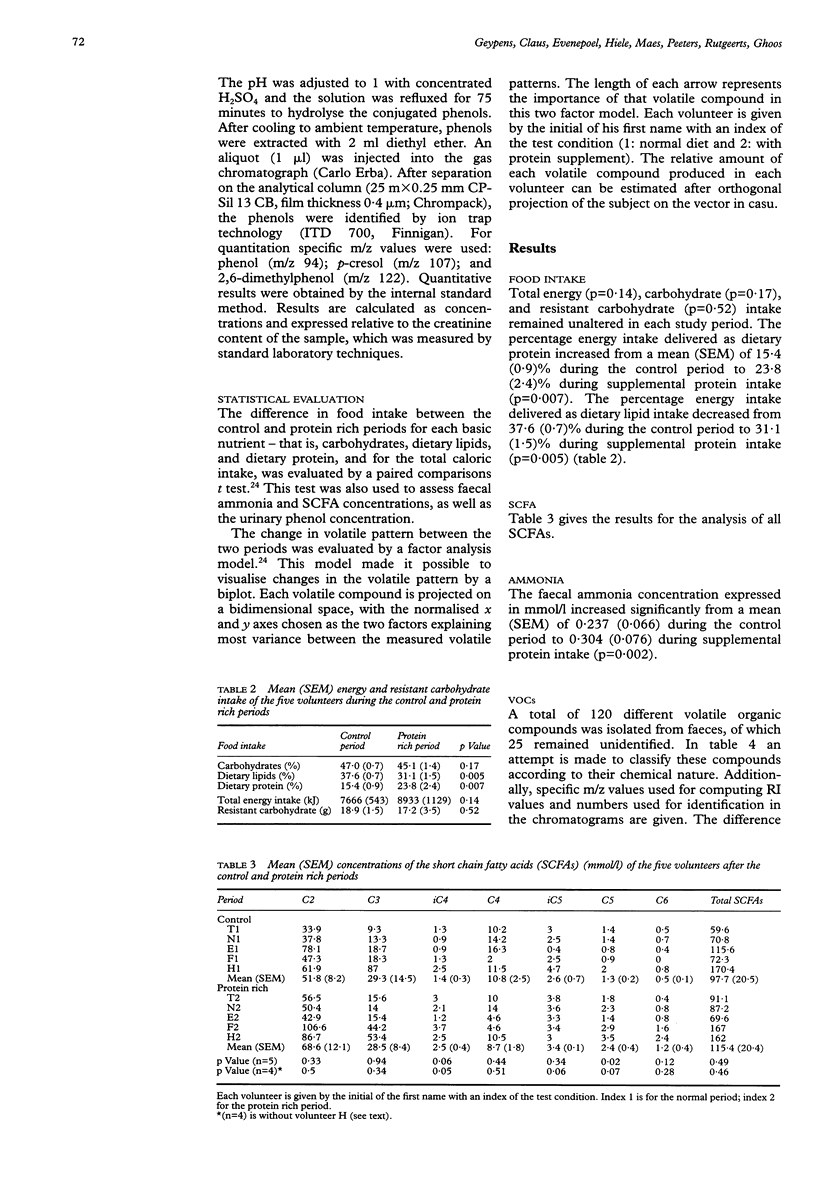

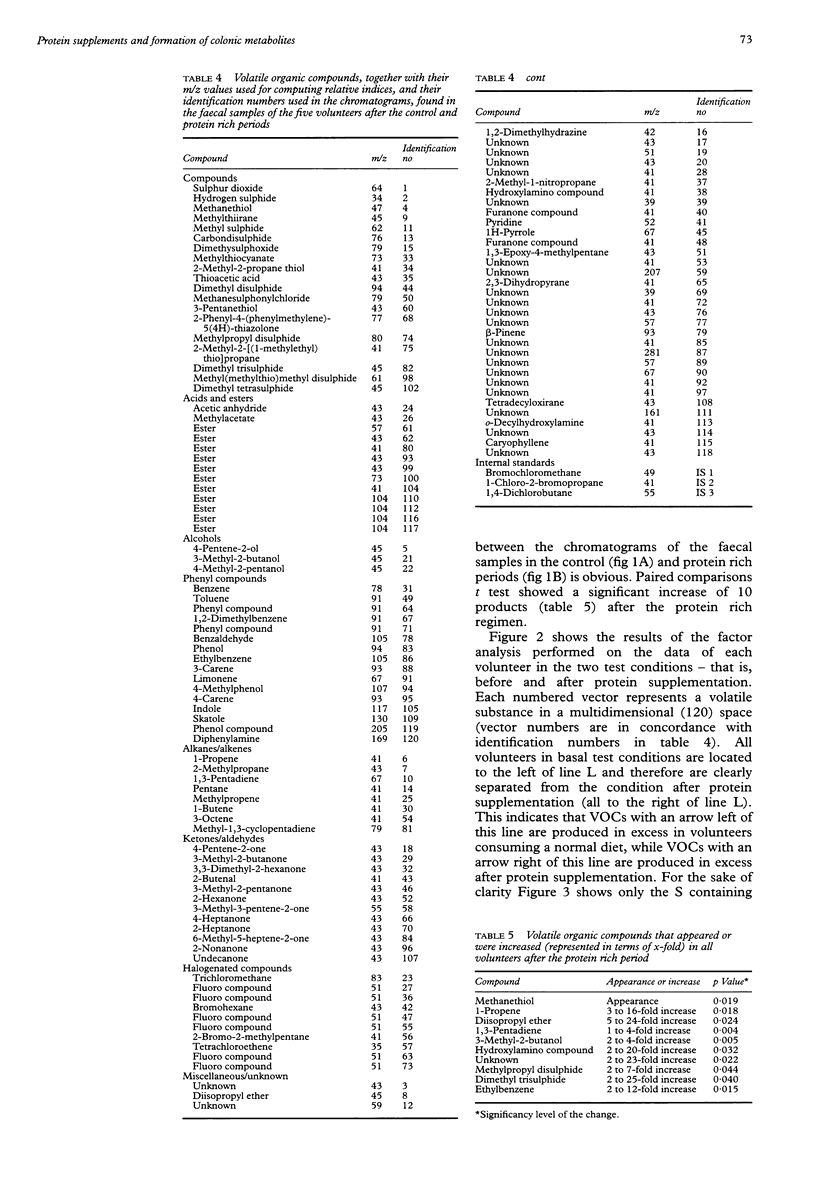

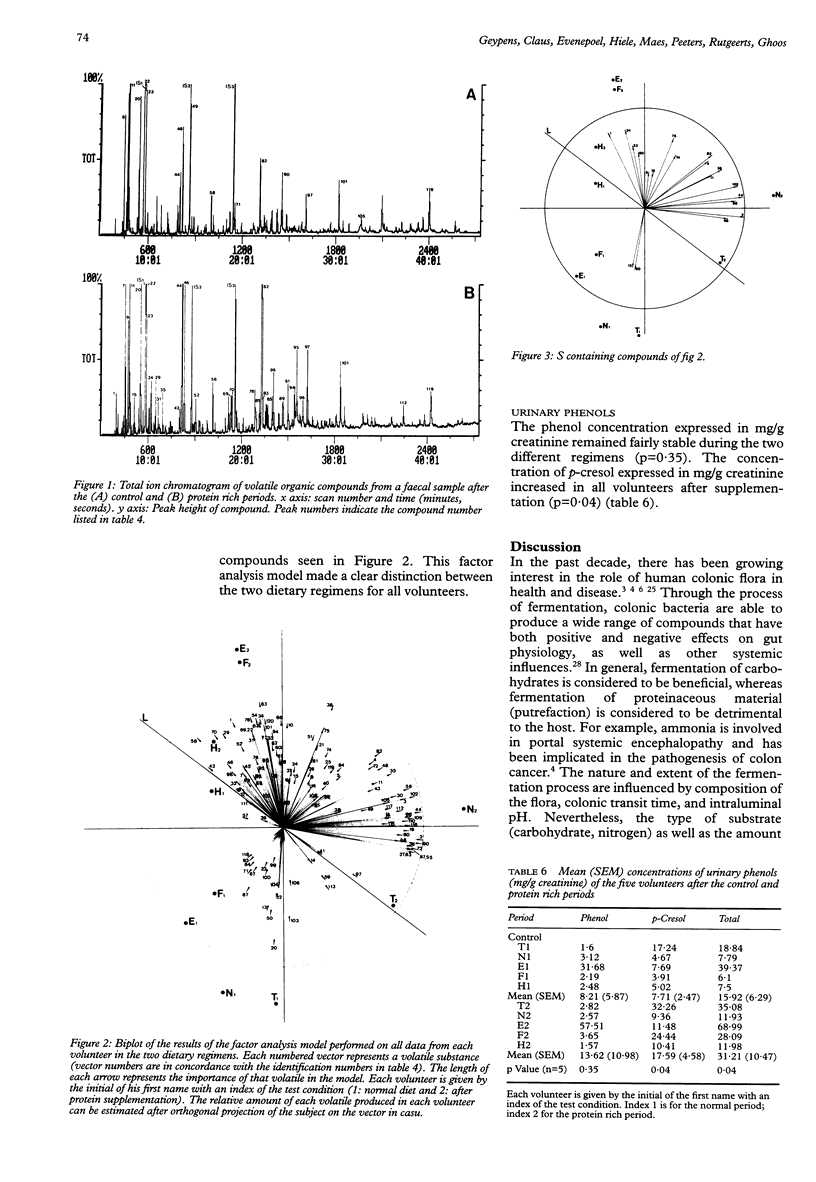

BACKGROUND: To evaluate the influence of increased dietary protein intake on bacterial colonic metabolism in healthy volunteers. METHODS: Short chain fatty acids, ammonia, and volatile organic compounds in faecal samples, and phenols in the urine of five volunteers were measured after one week of basal nutrient intake and and after one week of a diet supplemented with a protein rich food (Fortimel; Nutricia, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands). Paired t tests and factor analysis were used for statistical analysis. RESULTS: Total energy and resistant carbohydrate intake remained unchanged in each study period. The percentage energy intake delivered as dietary protein, increased significantly (from 15.4% to 23.8%; p = 0.007) during supplement intake. A significant increase in faecal ammonia (p = 0.002), faecal valeric acid (p = 0.02), and urinary p-cresol (p = 0.04) was noted during supplementary protein intake. A total of 120 different volatile compounds were isolated from the faecal samples of which 10 increased significantly during dietary protein supplementation. The change in volatile pattern, especially for S containing metabolites, was clearly shown by a factor analysis model which made a distinction between the two dietary regimens for all volunteers. CONCLUSION: An increase in dietary protein leads to altered products formation by colonic metabolism, mainly reflected by an increase in faecal ammonia, faecal volatile S substances, and urinary p-cresol.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armstrong B., Doll R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int J Cancer. 1975 Apr 15;15(4):617–631. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910150411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham S. A. Limitations of the various methods for collecting dietary intake data. Ann Nutr Metab. 1991;35(3):117–127. doi: 10.1159/000177635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G. A review of validations of dietary assessment methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Apr;115(4):492–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christl S. U., Murgatroyd P. R., Gibson G. R., Cummings J. H. Production, metabolism, and excretion of hydrogen in the large intestine. Gastroenterology. 1992 Apr;102(4 Pt 1):1269–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Hill M. J., Bone E. S., Branch W. J., Jenkins D. J. The effect of meat protein and dietary fiber on colonic function and metabolism. II. Bacterial metabolites in feces and urine. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979 Oct;32(10):2094–2101. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.10.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Macfarlane G. T. The control and consequences of bacterial fermentation in the human colon. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991 Jun;70(6):443–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoos Y., Claus D., Geypens B., Hiele M., Maes B., Rutgeerts P. Screening method for the determination of volatiles in biomedical samples by means of an off-line closed-loop trapping system and high-resolution gas chromatography-ion trap detection. J Chromatogr A. 1994 Apr 15;665(2):333–345. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)85062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G. R., Roberfroid M. B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr. 1995 Jun;125(6):1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiele M., Ghoos Y., Rutgeerts P., Vantrappen G., Schoorens D. Influence of nutritional substrates on the formation of volatiles by the fecal flora. Gastroenterology. 1991 Jun;100(6):1597–1602. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90658-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota H., Ishida Y. Production of volatile sulfur compounds by microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1972;26:127–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.26.100172.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane G. T., Hay S., Gibson G. R. Influence of mucin on glycosidase, protease and arylamidase activities of human gut bacteria grown in a 3-stage continuous culture system. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989 May;66(5):407–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb05110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahé S., Huneau J. F., Marteau P., Thuillier F., Tomé D. Gastroileal nitrogen and electrolyte movements after bovine milk ingestion in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Aug;56(2):410–416. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay L. F., Eastwood M. A., Brydon W. G. Methane excretion in man--a study of breath, flatus, and faeces. Gut. 1985 Jan;26(1):69–74. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K. E., Adams R. F., Earl J. W., Shaw K. J. Studies of the free faecal amines of infants with gastroenteritis and of healthy infants. Gut. 1986 Oct;27(10):1173–1180. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.10.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgaard I., Mortensen P. B., Langkilde A. M. Small intestinal malabsorption and colonic fermentation of resistant starch and resistant peptides to short-chain fatty acids. Nutrition. 1995 Mar-Apr;11(2):129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberfroid M. B., Bornet F., Bouley C., Cummings J. H. Colonic microflora: nutrition and health. Summary and conclusions of an International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) [Europe] workshop held in Barcelona, Spain. Nutr Rev. 1995 May;53(5):127–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1995.tb01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W. E., Duncan A., Kapaniris O., Millard S. Reducing sulfur compounds of the colon impair colonocyte nutrition: implications for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1993 Mar;104(3):802–809. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royall D., Wolever T. M., Jeejeebhoy K. N. Clinical significance of colonic fermentation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990 Oct;85(10):1307–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry Z. I., Shadarevian S. B., Cowan J. W., Campbell J. A. Relationship of dietary intake of sulphur amino-acids to urinary excretion of inorganic sulphate in man. Nature. 1965 May 29;206(987):931–933. doi: 10.1038/206931b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppach W. Effects of short chain fatty acids on gut morphology and function. Gut. 1994 Jan;35(1 Suppl):S35–S38. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1_suppl.s35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen A. M., Wiggins H. S., Cummings J. H. Effect of changing transit time on colonic microbial metabolism in man. Gut. 1987 May;28(5):601–609. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strocchi A., Levitt M. D. Maintaining intestinal H2 balance: credit the colonic bacteria. Gastroenterology. 1992 Apr;102(4 Pt 1):1424–1426. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince A. J., McNeil N. I., Wager J. D., Wrong O. M. The effect of lactulose, pectin, arabinogalactan and cellulose on the production of organic acids and metabolism of ammonia by intestinal bacteria in a faecal incubation system. Br J Nutr. 1990 Jan;63(1):17–26. doi: 10.1079/bjn19900088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreman H. J., Dowling J. A., Raubach R. A., Weiner M. W. Determination of acetate in biological material by vacuum microdistillation and gas chromatography. Anal Chem. 1978 Jul;50(8):1138–1141. doi: 10.1021/ac50030a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]