Abstract

The gut microbiota Parvimonas micra has been found to be enriched in gut mucosal tissues and fecal samples of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients compared with non-CRC controls. In the present study, we investigated the tumorigenic potential of P. micra and its regulatory pathways in CRC using HT-29, a low-grade CRC intestinal epithelial cell. For every P. micra-HT-29 interaction assay, HT-29 was co-cultured anaerobically with P. micra at an MOI of 100:1 (bacteria: cells) for 2 h. We found that P. micra increased HT-29 cell proliferation by 38.45% (P=0.008), with the highest wound healing rate at 24 h post-infection (P=0.02). In addition, inflammatory marker expression (IL-5, IL-8, CCL20, and CSF2) was also significantly induced. Shotgun proteomics profiling analysis revealed that P. micra affects the protein expression of HT-29 (157 up-regulated and 214 down-regulated proteins). Up-regulation of PSMB4 protein and its neighbouring subunits revealed association of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (UPP) in CRC carcinogenesis; whereas down-regulation of CUL1, YWHAH, and MCM3 signified cell cycle dysregulation. Moreover, 22 clinically relevant epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-markers were expressed in HT-29 infected with P. micra. Overall, the present study elucidated exacerbated oncogenic properties of P. micra in HT-29 via aberrant cell proliferation, enhanced wound healing, inflammation, up-regulation of UPPs, and activation of EMT pathways.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, HT-29, infection, iTRAQ-LC-MS/MS, Parvimonas micra, pathogenesis

Background

Unhealthy diet and lifestyle, which have long been associated with the occurrence of CRC, can also lead to microbiota dysbiosis in the colon [1,2]. As a result of dysbiosis, pathogenic microbes displace normal flora in the colon and/or rectum, disrupting its normal regulation and homeostasis [3,4]. Specifically, settlement of these pathobionts may trigger the secretion of toxins, activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and inflammation of colon cells; thereby increasing the risks of CRC in the host [5]. Indeed, scientists have proposed the tumorigenic roles of gut-associated microbes in CRC, including Streptococcus bovis [6], Enterococcus faecalis [7], Bacteroides fragilis [8], Streptococcus gallolyticus [9], Escherichia coli [10], and Fusobacterium nucleatum [11].

Recently, we reported a 3-fold enrichment of Parvimonas micra, an oral bacteria, in the gut mucosa tissues of 18 Malaysian CRC patients compared with 18 non-CRC patients based on 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing [12]. Though the roles of P. micra in CRC oncogenesis remain unclear, our previous findings were consistent with published meta-analyses, which demonstrated enrichment of P. micra in almost 2,000 participants of various CRC cohorts from different geographical locations [13,14]. Besides CRC, P. micra infections have also been associated with cancer of the oral cavity and stomach [15,16], underscoring the intriguing association and possible role of the bacteria in malignant tumour occurrence and development.

Later, Zhao and co-workers’ studies investigating P. micra infection using in vivo models indicated positive correlations of P. micra abundance with tumour burden, cell proliferation, and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [17,18]. In this work, we elected instead to follow up in an in vitro manner our previous findings by infecting HT-29, a CRC intestinal epithelial cell line with P. micra. We aimed to investigate the effects of this infection on cell morphology and functional characteristics. We additionally profiled the molecular changes of the proteome as a result of this bacteria–host cell interaction with shotgun proteomics followed by pathway analysis, to provide a better understanding of the role of P. micra in CRC.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that P. micra infections might play a role in CRC pathogenesis in the HT-29 cell line by affecting its cell proliferation, wound healing, cell cycle activity, and causing inflammation. From this study, additional information of the putative tumorigenic role of P. micra in CRC would be elucidated.

Methodology

Bacteria culture

P. micra (DSM 20468) was purchased from DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH (Germany) in active culture form. E. coli DH5α was a gift from the Department of Bacteriology, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan. Both bacteria were cultured at 37°C in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth anaerobically in an AnaeroPack™ 2.5 L rectangular jar containing an AnaeroGen™ sachet 3.5 L [19] for all experiments.

Intestinal epithelial cell culture

A low-grade colon cancer intestinal epithelial cell, HT-29 was used in all experimental setups. It was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, U.S.A.) and maintained using the Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 media (Pan Biotech, Germany) supplemented with 12% fetal bovine serum (Tico Europe, Netherlands). For co-culture assays, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Japan) was added post-infection to stop bacterial growth. For the maintenance of the cells, HT-29 was cultured inside a 37°C incubator supplemented with 5% CO2, and 95% O2. During co-culture assays, the cells were maintained in a similar anaerobic condition as the tested bacteria [20].

HT-29 and bacteria co-culture

Cell proliferation assay

HT-29 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in antibiotic-free growth media and grown aerobically overnight. After overnight incubation, cells were introduced with P. micra at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1 (bacteria: cells) [21]. E. coli DH5α was used as bacteria-host interaction control, while uninfected HT-29 was a control for the co-culture system. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 2 hr anaerobically. Next, all experiment sets were washed three times with 1× PBS solution followed by supplementation of growth media with antibiotics. The plate was then incubated for another 72 hr anaerobically. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 20% methanol and stained with crystal violet stain solution (Merck, Germany). Cell images were taken with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, U.S.A.). Dried stained cells were then diluted with 10% acetic acid prior optical density (OD) reading at 600 nm using a Varioskan™ Flash Spectral Scanning Multimode Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, U.S.A.). All experiments were conducted three times with technical triplicates.

Wound healing assay

Twelve-well plates were marked on the bottom of each well at specific locations prior experiments. HT-29 cells were then seeded at a total of 5 × 105 cells/well. Cells were supplemented with antibiotic-free growth media and grown overnight. Wells with at least 90% confluent cells were later wounded using 200 μl pipette tips and washed with 1× PBS solution. Wounded cells were then replenished with antibiotic-free growth media. Tested bacteria were introduced to the cells at an MOI of 100:1 (bacteria: cells); uninfected cells were introduced to BHI broth only. Co-cultured plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 hr anaerobically. Later, cells were washed three times with 1× PBS solution and replenished with growth media supplemented with antibiotics. Wound images were observed and captured at three different time points (0, 24, and 48 hr) at a unified location. Wound area size was measured as the distance between cell edges using ImageJ Software Version 1.53f (Maryland, U.S.A.) with the value at 0 hr as a baseline. The difference in wound size percentage between each tested bacteria–host interaction assay and the control was also determined. Each experiment setup was repeated three times with technical triplicates.

Inflammatory marker expression

HT-29 cells were seeded in a P60 cell culture dish at a density of 5 × 105 cells per dish. Cells were then grown overnight anaerobically. Adhered cells were infected with P. micra at an MOI of 100:1 (bacteria: cells). Uninfected cells supplemented with BHI broth were used as a control. Both infected and uninfected HT-29 were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 2 hr. Later, the growth media was moved and cell monolayers were washed three times with 1× PBS. Cells were then replenished with growth media supplemented with antibiotics, and further cultured anaerobically for 2, 24, or 48 hr. At the end of each designated incubation period, total cell RNA from each experiment set was extracted using guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction. Extracted RNA was converted to cDNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, U.S.A.). Relative expression of inflammatory genes (IL-5, IL-8, IL-22, CCL20, TIMP1, CSF2) and housekeeping genes (HPRT, β-tubulin) was analysed using QuantiNova SYBR® Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN, U.S.A.) via an Applied Biosystem® 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, U.S.A.). Primer sequences for each tested gene were designed using the Primer-BLAST software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast) (NCBI, U.S.A.) and listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Top 10 down-regulated proteins from pathways that were enriched by P. micra infection.

| Pathway | Protein (Gene ID) | P-value | Log2 fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative phosphorylation | MT-CO2 | 0.01 | --1.55 |

| Fatty acid degradation | ACOX1 | 0.005 | −1.44 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | ATP5PB | 0.02 | −1.42 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | NDUFS3 | 0.003 | --1.42 |

| Cell cycle | YWHAH | 0.0007 | −1.40 |

| Cell cycle | CUL1 | 0.03 | --1.39 |

| Spliceosome | SNRPD1 | 0.01 | −1.32 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | PPA2 | 0.002 | --1.31 |

| Spliceosome | RBM17 | 0.001 | −1.30 |

| Cell cycle | MCM3 | 0.02 | --1.29 |

Differential proteomics profiling

Proteomics analysis of HT-29 infected with P. micra was determined to elucidate pathways associated with P. micra-associated CRC development. HT-29 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 5×105 cells/mL and incubated aerobically overnight. Cells were then co-cultured with P. micra at an MOI of 100:1 (bacteria: cells), whereas uninfected cells were supplemented with BHI. Both setups were incubated anaerobically for 2 hr. After 2 hr, cells were washed with 1× PBS three times and replenished with growth media supplemented with antibiotics. Cells were incubated again anaerobically for 24 hr and harvested by adding 2× of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA solution followed by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min.

Cell pellets were subsequently collected for protein extraction and proteomics analysis. Total cell protein was extracted using lysis buffer (8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate) with pulsed ultra-sonication and high-speed centrifugation. Protein concentration was estimated using a Bradford assay. Extracted proteins were later subjected to acetone precipitation. Protein reduction, alkylation, trypsin digestion, iTRAQ labelling (AB SCIEX, U.S.A.), C18 reverse-phase desalting, and LC-MS/MS analysis with the Eksigent reversed-phase nanoLC (AB SCIEX, U.S.A.) coupled with 6600 TripleTOF (AB SCIEX, U.S.A.) system were carried out by the Protein and Proteomic Center (PPC), Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, National University of Singapore (NUS) using the standard protocol in their previous study [22].

For analysis, protein sequences were extracted from ProteinPilot 5.0 software Revision 4769 (AB SCIEX, U.S.A.), by using the Paragon database search algorithm (5.0.0.0.4767) and integrated false discovery rate (FDR) analysis function. Later, protein profiles were compared with the Homo sapiens reference proteome (UP000005640, 29 Jan 2021, 20380 entries) using SwissProt and spiked contaminant proteins (cRAP). A global FDR threshold at 1% was implemented for differential protein determination (at least one peptide). Protein log2 fold change with a value of >1.0 was categorized as up-regulated, whereas a log2 fold change of < -1.0 was considered as down-regulated. Lastly, all proteins without iTRAQ quantitation ratios, and/or with accession and with ‘contam’, ‘RRRR’ and ‘REVERSED’ descriptions were removed from the analysis.

P. micra-associated CRC tumorigenesis pathway determination

DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) and PANTHER16.0 database (http://pantherdb.org/) were used to determine Gene Ontology (GO) classification of identified proteins based on biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Pathway analyses were performed using the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. Protein interactions were built using STRING 11.5 databases (https://string-db.org/) for selected proteins. Identification of EMT-related proteins was done using EMTome (http://www.emtome.org/) database and dbEMT 2.0 database (http://dbemt.bioinfo-minzhao.org/).

Statistical analysis

All data obtained were analysed using GraphPad PRISM 9.2.0 (GraphPad Software, U.S.A.). The Mann–Whitney test, two-way multiple comparisons ANOVA and Student’s t-test were used to analyze results from functional assays, inflammatory marker expression determination and differential proteomics profiling, respectively. All statistical analyses with P-values of *≤ 0.05, **≤ 0.01, ***≤0.001, and ****≤ 0.0001 were considered significant.

Results

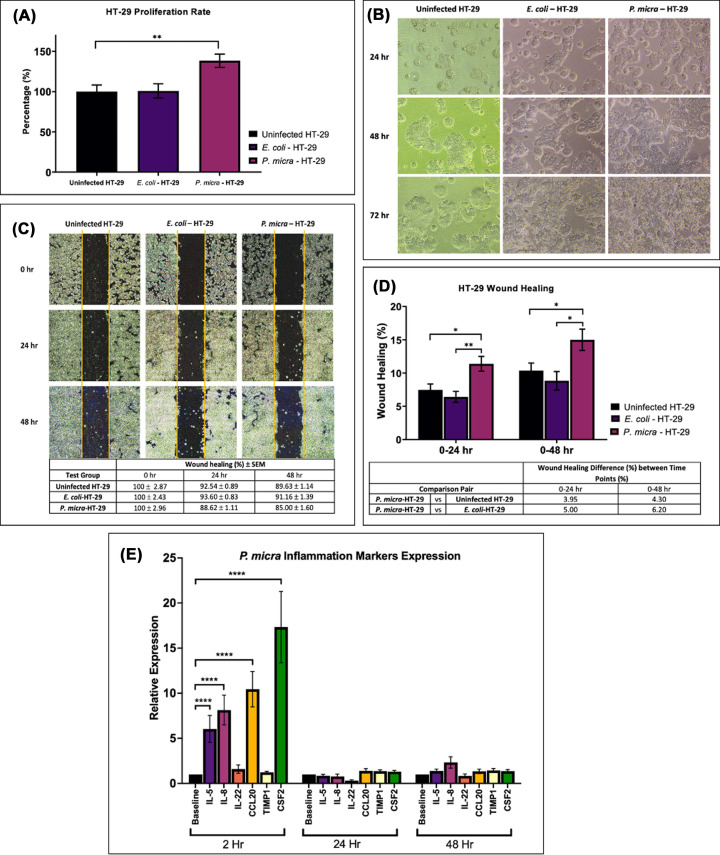

P. micra increased the rate of HT-29 proliferation and wound healing

Co-culture of P. micra with HT-29 increased the rate of HT-29 proliferation by 38.45% (P=0.008) 72 hr post-infection (Figure 1A). Highly densed colonies were also observed on cells infected with P. micra. On the other hand, E. coli DH5α co-culture did not affect HT-29 cell proliferation (P=0.691) nor its colony formation. P. micra infection was found to increase HT-29 proliferation rate and promote morphological changes compared with experimental controls (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Effects of P. micra infection on cell proliferation, wound healing, and inflammation of the HT-29 cell line.

(A) Cell proliferation rate of HT-29 (uninfected HT-29), co-culture of E. coli DH5α and HT-29 (E. coli-HT-29), and co-culture of P. micra and HT-29 (P. micra-HT-29). Difference between groups were analyzed by Mann–Whitney test; **P≤ 0.01; (B) Observation of cell proliferation activity on uninfected HT-29, E. coli-HT-29, and P. micra-HT-29 at 24, 48, and 72 hr post-infection; (C) Wound healing and (D) wound area differences at 0–24 hr and 0–48 hr of uninfected HT-29 and HT-29 infected with P. micra and E. coli. Difference between groups were analyzed by Mann–Whitney test; *P≤ 0.05, **P≤0.01. (E) Relative expression of inflammatory markers (IL-5, IL-8, IL-22, CCL20, TIMP1, CSF2) upon P. micra infection on HT-29 at 2, 24, and 48 hr post-infection. Difference between groups were analyzed by two-way multiple comparison ANOVA test; ****P≤0.0001.

The wound healing activity of infected HT-29 was determined at 0, 24, and 48 hr post-infection at a unified location (Figure 1C). Cells infected with P. micra showed highest wound healing percentage at 24 hr (10.55%) and 48 hr (12.7%) post-infection. At 24 hr, wound healing activity in P. micra-HT-29 was substantially higher compared to uninfected HT-29 (3.95%, P=0.02) and E. coli-HT-29 (5.00%, P=0.003). The same trend was observed at 48 hr comparison between P. micra-HT-29 against uninfected HT-29 (4.30%, P=0.03) and E. coli-HT-29 (6.20%, P=0.01) (Figure 1D).

Induction of inflammatory response upon P. micra infection

Quantification of the expression of six inflammatory markers (IL-5, IL-8, IL-22, CCL20, TIMP1, CSF2) was carried out at 2, 24, and 48 hr post-infection. P. micra infection was found to up-regulate the expression of IL-5 (P=0.0001), IL-8 (P=0.0001), CCL20 (P=0.0001), and CSF2 (P=0.0001) at 2 hr post-infection (Figure 1E). Nevertheless, the increment in expression was not observed at 24 and 48 h post-infection. IL-22 and TIMP1 expression was found to be similar at all time-points point infection.

Proteomics profiling of HT-29 infected with P. micra

Differential proteomics profiling analysis between uninfected HT-29 & P. micra-HT-29 revealed a total of 59,959 protein spectra. Eliminating the low-scoring spectra, 34,794 unique spectra were matched with 1,777 proteins based on the SwissProt human database. A FDR at 1% reduced the amount of unique proteins to 1,389. From these proteins, a total of 157 up-regulated proteins and 214 down-regulated proteins were identified (P<0.05).

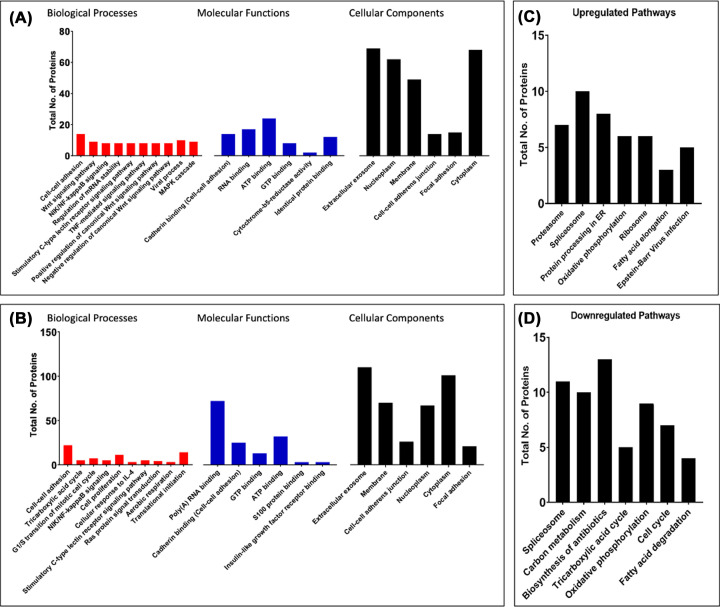

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis in P. micra-associated CRC tumorigenesis

GO enrichment analysis of up- (Figure 2A) and down-regulated (Figure 2B) proteins expressed during P. micra-associated HT-29 cell proliferation revealed differential protein expression of cellular components, correlating cellular processes changes during cell proliferation and wound healing.

Figure 2. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of P. micra infection in HT-29.

(A) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulated proteins in P. micra-HT-29 compared with uninfected HT-29 and (B) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulated proteins in P. micra-HT-29 compared with uninfected HT-29 based on biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Enrichment analysis was made using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 and PANTHER16.0; (C) Enriched up-regulated pathways and (D) enriched down-regulated pathways associated with P. micra infection in CRC tumorigenesis. Pathways enrichment was analyzed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 and PANTHER16.0.

P. micra in CRC tumorigenesis

Up- and down-regulated differentially expressed proteins in P. micra-HT29 compared with uninfected HT-29 were analysed separately to reveal P. micra-associated CRC tumorigenesis pathways. Figure 2C shows seven differentially expressed pathways with the highest log2 fold change in P. micra-HT-29 compared to uninfected HT-29. On the other hand, pathways that were found to be down-regulated by P. micra infection are illustrated in Figure 2D.

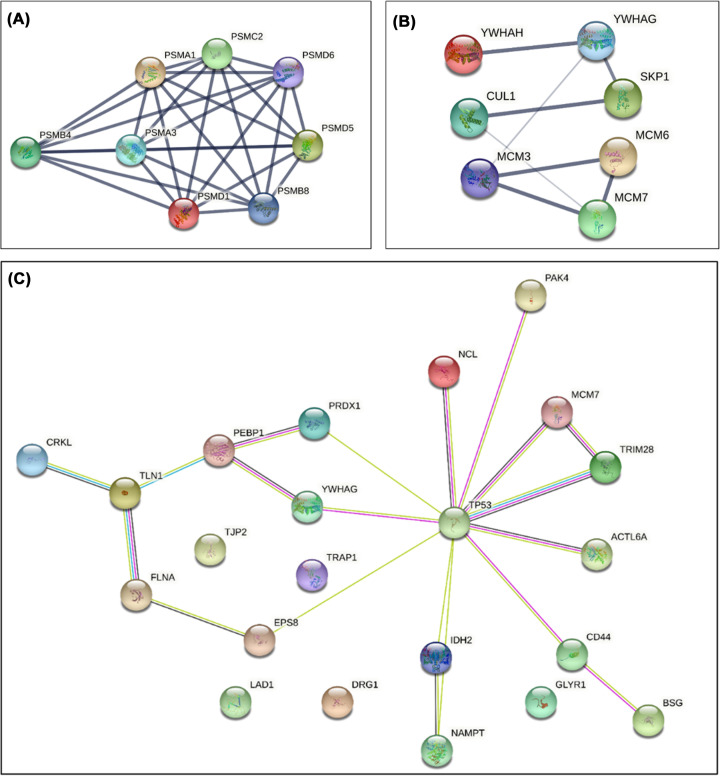

Top 10 proteins with the highest log2 fold change from these seven pathways were further analyzed (Table 1). Proteasome subunit beta type-4, PSMB4, was identified to be putatively crucial in P. micra-associated CRC tumorigenesis and commonly overexpressed in other human cancer [23]. PSMB4 protein–protein interaction figure with neighbouring proteasomal subunits (PSMA1, PSMA3, PSMC2, PSMD1, PSMD6, PSMB8, and PSMD5) was built (Figure 3A, Table 2).

Table 1. Primer sequences for inflammatory marker and housekeeping gene expression determination.

| Marker | Primer | Nucleotide Sequences (5′ to 3′) | Length (base pair) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory | CSF2 Forward | 5′-AATGTTTGACCTCCAGGAGCC-3′ | 21 |

| CSF2 Reverse | 5′-TCTGGGTTGCACAGGAAGTTT-3′ | 21 | |

| Inflammatory | IL-5 Forward | 5′-AACTGTGCAAGGGGGTACTG-3′ | 20 |

| IL-5 Reverse | 5′-AGGCCTGACTCTTTCTTGGC-3′ | 20 | |

| Inflammatory | IL-8 Forward | 5′-TGCTTCCCCTTAGCATTTTGT-3′ | 21 |

| IL-8 Reverse | 5′-CCAGCTATGCTAAAGCGCAC-3′ | 20 | |

| Inflammatory | IL-22 Forward | 5′-CCTTCCCCAGTCACCAGTTG-3′ | 20 |

| IL-22 Reverse | 5′-TGCGGTTGGTGATATAGGGC-3′ | 20 | |

| Inflammatory | CCL20 Forward | 5′-CAAGAGTTTGCTCCTGGCTG-3′ | 20 |

| CCL20 Reverse | 5′-GCTTGCTGCTTCTGATTCGC-3′ | 20 | |

| Inflammatory | TIMP1 Forward | 5′-TTCTGGCATCCTGTTGTTGCT-3′ | 21 |

| TIMP1 Reverse | 5′-CCTGATGACGAGGTCGGAATT-3′ | 21 | |

| Housekeeping | HPRT Forward | 5′-TGTTGGTTCCATTTTCCTTGTTTG-3′ | 24 |

| HPRT Reverse | 5′-GGTAGCCAAGTGGACCTCAG-3′ | 20 | |

| Housekeeping | β-tubulin Forward | 5′- TTCAAGGGAGGTGTCAGCAGTA-3′ | 22 |

| β-tubulin Reverse | 5′- GTGAGGGAGGTAGAGTTGGAA-3′ | 21 |

Figure 3. Protein-protein network interaction of P. micra infection in HT-29.

(A) Protein network interaction of PSMB4 with neighbouring proteasomal subunits that were differentially expressed in P. micra-HT-29 based on STRING. (B) Protein network interaction of CUL1, YWHAH, and MCM7 with proteins associated with cell cycle activity in HT-29 infected with P. micra generated using STRING; (C) Network of EMT-related proteins in CRC tumorigenesis expressed by HT-29 upon P. micra infection generated from STRING.

Table 2. Top 10 up-regulated proteins from pathways that were enriched by P. micra infection in HT-29.

| Pathway | Protein (Gene ID) | P-value | Log2 fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative phosphorylation | ATP5F1A | 0.0008 | 1.67 |

| Protein processing in ER | DNAJA1 | 0.03 | 1.64 |

| Spliceosome | U2AF2 | 0.0008 | 1.57 |

| Ribosome | MRPL10 | 0.02 | 1.50 |

| Fatty acid elongation | TECR | 0.01 | 1.49 |

| Proteasome | PSMB4 | 0.0007 | 1.48 |

| Ribosome | RPS28 | 0.002 | 1.41 |

| Protein processing in ER | SEC24C | 0.02 | 1.38 |

| Spliceosome | LSM5 | 0.02 | 1.31 |

| Protein processing in ER | CAPN1 | 0.009 | 1.31 |

Among the top 10 down-regulated proteins in P. micra-HT-29 were cullin 1 (CUL1), tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein eta (YWHAH), and minichromosome maintenance complex component 3 (MCM3). Protein network interaction between these three proteins and other significantly down-regulated proteins (YWHAG, SKP1, MCM6, and MCM7) are shown in Figure 3B.

Intriguingly, a few apoptosis related proteins were also found to be differentially expressed by the infected cells. These include the up-regulation of heat shock protein family (HSAP9, HSP90B) and down-regulation of apoptosis-inducing factor 1 (AIFM1).

Overexpression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) proteins induced by P. micra in HT-29

Some of the differentially expressed proteins (n=47) in P. micra infected HT-29 were associated with EMT. Nine up-regulated (CD44, DRG1, BSG, NCL, CRKL, TP53, PAK4, NAMPT, ACTL6A) and thirteen down-regulated proteins (PRDX1, PEBP1, FLNA, EPS8, YWHAG, TRIM28, TLN1, IDH2, TRAP1, GLYR1, MCM7, LAD1, TJP2) were associated with CRC tumorigenesis (P<0.05). Protein–protein interaction network of these proteins elucidated TP53 regulation with significant interaction of NCL, PAK4, MCM7, TRIM28, YWHAG, ACTL6A, CD44, IDH2, EPS8, and PRDX1 during P. micra infection (Figure 3C).

Discussion

Gut mucosal and faecal sequencing association studies have identified a variety of gut bacteria as being over-represented in CRC patients [12–14]. Nevertheless, mechanistic studies demonstrating tumorigenesis effects of these bacteria, including P. micra, a gut microbiota associated with CRC tumours of the consensus molecular subtype 1 (CMS1) [24], remains few. P. micra was previously known as Streptococcus micros (1933), Peptostreptococcus micros (1957), and Micromonas micros (1999) [25,26] and is the sole species in the Parvimonas genus. It is a Gram-positive cocci, an obligate anaerobe that resides dominantly in the oral cavity as a commensal pathogen. Even so, the isolation of P. micra is not limited to the oral cavity [27], but also in the laryngeal pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, pus abscess, spondylodiscitis, and blood samples [28–30].

In the present study, P. micra infection was accompanied by a significant increase in the proliferation of HT-29 for three consecutive days, compared with our control experiments comprising E. coli-HT-29 and uninfected HT-29 that showed no significant changes. In addition, co-culture of P. micra with HT-29 demonstrated significantly increased wound healing properties even at 48 hr observation. Similar observations were reported by Zhao et al. suggesting that the bacteria may trigger proliferative signalling in cells and lead to uncontrollable cell division [17].

Upon co-culturing P. micra and HT-29, the expression of IL-5, IL-8, CCL20, and CSF2 became elevated; indicating the possible activation of PI3K-AKT, NF- κB and MAPK pathway in P. micra-associated CRC [31–34]. Indeed, most CRC-associated pathobionts have been shown to modulate inflammation. Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis was found to induce colonic tumours via the T-helper type 17 inflammatory response [8] and infection of F. nucleatum caused upregulation in cellular cytokines levels via NF-κB activation and β-catenin phosphorylation [35]. In the in vivo study by Yu et al. [18], P. micra infection of germ-free mice was found to increase the expression level of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-6, and CXCR1, indicating the importance of inflammation in pathobiont-associated CRC. Even though the increases were only observed at the 2 hr time point in our study, this infection-associated inflammation may sustain in vivo, especially in the colon of CRC patients. This occurs in addition to cell proliferation and migration, contributing towards tumorigenesis.

To further disentangle the roles of P. micra in CRC, differential protein expression between P. micra-HT-29 and uninfected HT-29 was determined. Proteins of cellular components in HT-29 were found to be enriched by P. micra infection and this corresponds to the proliferative changes observed in our functional assays. In addition, expression of proteins involved in NIK/NF-κB, Wnt signalling, and TNF-mediated signalling pathways [36,37] were also elevated in P. micra infected HT-29, indicating the carcinogenic role of the bacteria in tumorigenesis. Of note, up-regulation of PSMB4 was also found in P. micra-HT-29, which hypothetically occurred alongside the increased expression of neighbouring proteasomal subunits of PSMA1, PSMA3, PSMB8, PSMC2, PSMD1, PSMD5 and PSMD6. These protein components are crucial to the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (UPP) activation in cancer [38,39], where they interfere degradation of β-catenin via Wnt signalling, resulting in continuous proliferation and metastasis in CRC [40,41]. PSMB4 was also found to be associated with formation of blood vessels (angiogenesis) and metastasis [42,43]. Upregulation of PSMB4 and mutated tumour suppressor p53 in the infected cells might function to activate inflammatory responses via NIK/NF- κB pathways [23,44]. On the other hand, down-regulation of CUL1, YWHAH, and MCM3 was observed; these proteins play a role in disturbing cell cycle activity [45–47]. Furthermore, significant differentially expressed EMT proteins were found to be induced by P. micra infection, mediating the cells towards increased proliferation, invasion and survival in CRC [48–53]. In addition, regulation of proteins such as HSAP9, HSP90B, and AIFM1 was altered, restricting apoptosis and promoting proliferation of infected cells [54–56].

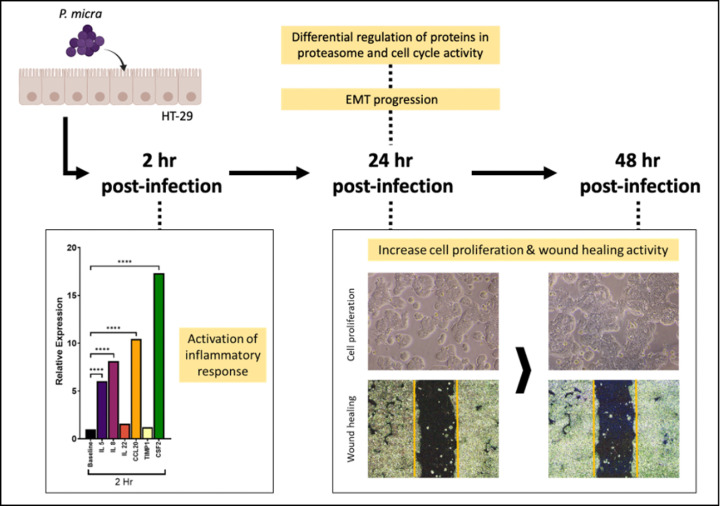

Taking it all together, we found that P. micra infection in HT-29 for 2 hr in an in vitro system lead to increased inflammatory response in the cells. This occurs in concert with cell perturbation due to proteasome and cell cycle activity, mediating the cells towards EMT at 24 hr after infection. Morphologically, increased cell proliferation and wound healing were observed compared to HT-29 cells without infection, signifying the contribution of P. micra towards increased tumorigenesis in HT-29 (Figure 4). Nevertheless, as these observations were found in an in vitro model utilizing a CRC cell line (whereas an in vivo model will allow investigation into the dynamic effects of chronic P. micra infection on the colon cells), future studies investigating similar parameters of the bacterial infection in an animal model will be useful to confirm the definite role of P. micra in CRC.

Figure 4. Summary of events in P. micra-associated tumorigenesis.

P. micra-associated carcinogenesis in HT-29 at different post-infection time points. Cell inflammation was detected at 2 hr, followed by cell proliferation and increased wound healing at 24 and 48 hr post-infection.

Future direction

As this study has been conducted on the HT-29 (a CRC cell line) and with P. micra as the only tested pathobiont, future areas of investigation include to confirm the tumorigenic potential of the bacteria in a non-CRC colon cell line, both in a sole-pathobiont and also dysbiotic bacterial community study to elucidate the complexity and interaction of these bacterial communities in CRC. It will also be interesting to investigate the ability of probiotics in protecting cells infected with P. micra from tumorigenesis. As P. micra demonstrated tumorigenic properties in this study and has been identified to be over-represented in gut mucosal tissues and stool samples of CRC patients, the bacteria could be investigated as potential biomarker for CRC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated increased tumorigenesis properties caused by P. micra infection in a HT-29 model and provided additional evidence of P. micra as a pathobiont in the colon. Future studies of the bacteria's interplay with other colon pathobionts will be important to understand its role in CRC.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge usage of the tissue culture laboratory in UKM Medical Molecular Biology Institute, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. In addition, services and assistance received from the team at the Protein and Proteomics Centre (PPC), Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore are much appreciated.

Abbreviations

- ACOX1

acyl-CoA oxidase 1

- ACTL6A

actin like 6A

- AIFM1

apoptosis-inducing factor 1

- ATP5F1A

ATP sythase F1 subunit alpha

- ATP5PB

ATP synthase peripheral stalk-membrane subunit B

- BSG

basigin

- CAPN1

calpain 1

- CCL20

chemokine (C-C) motif ligand 20

- CMS1

consensus molecular subtype

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CRKL

CRK like proto-oncogene, adaptor protein

- CSF2

colony stimulating factor 2

- CUL1

cullin 1

- CXCR1

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1

- DNAJA1

DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member A1

- DRG1

developmentally regulated GTP binding protein 1

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- EPS8

epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8

- FLNA

filamin A

- GLYR1

glyoxylate reductase 1 homolog

- GO

gene ontology

- HPRT

hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1

- HSAP9

heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 9

- HSP90B

heat shock protein 90 alpha family class B member 1

- IDH2

isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP(+))2)

- IL-5

interleukin 5

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- IL-17A

interleukin 17A

- IL-22

interleukin 22

- iTRAQ

isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation

- LAD1

ladilin 1

- LSM5

LSM5 homolog, U6 small nuclear RNA and mRNA degradation associated

- MCM3

minichromosome maintenance complex component 3

- MCM6

minichromosome maintenance complex component 6

- MCM7

minichromosome maintenance complex component 7

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- MRPL10

mitochondrial ribosomal protein L10

- MT-CO2

mitochondrially encoded cytochrome C oxidase II

- NAMPT

nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

- NCL

nucleolin

- NDUFS3

NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S3

- PAK4

P21 (RAC1) atctivated kinase 4

- PEBP1

phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein 1

- PPA2

inorganic pyrophosphatase 2

- PRDX1

peroxiredoxin 1

- PSMA1

proteasome 20S subunit alpha 1

- PSMA3

proteasome 20S subunit alpha 3

- PSMB4

proteasome subunit beta 4

- PSMB8

proteasome 20S subunit beta 8

- PSMC2

proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase 2

- PSMD1

proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase 1

- PSMD5

proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase 5

- PSMD6

proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase 6

- RBM17

RNA binding motif protein 17

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RPS28

40S ribosomal protein S28

- SEC24C

SEC24 homolog C, COPII coat complex component

- SNRPD1

small nuclear ribonucleoprotein D1 polypeptide

- SKP1

S-phase kinase-associated protein 1

- TECR

trans-2,3-enoyl-CoA reductase

- TIMP1

TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1

- TJP2

tight junction protein 2

- TLN1

talin 1

- TP53

tumor protein P53

- TRAP1

TNF receptor associated protein 1

- TRIM28

tripartite motif containing 28

- UPP

ubiquitin–proteasome pathway

- U2AF2

U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 2

- YWHAG

tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein gamma

- YWHAH

tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein eta

Data Availability

Data are available on request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded at http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24406.32320.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme [grant number FRGS/1/2018/SKK11/UKM/02/2] awarded by the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia.

CRediT Author Contribution

Muhammad Nur Adam Hatta: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Ezanee Azlina Mohamad Hanif: Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. Siok-Fong Chin: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. Teck Yew Low: Resources, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. Hui-min Neoh: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

References

- 1.Sánchez-Alcoholado L., Ramos-Molina B., Otero A., Laborda-Illanes A., Ordóñez R., Medina J.A.et al. (2020) The role of the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer development and therapy response. Cancers 12, 1406 10.3390/cancers12061406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeDecker L., Coppedge B., Avelar-Barragan J., Karnes W. and Whiteson K. (2021) Microbiome distinctions between the CRC carcinogenic pathways. Gut Microbes 13, 1854641 10.1080/19490976.2020.1854641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu L., Bazin T., Truchetet M.E., Schaeverbeke T., Delhaes L. and Pradeu T. (2017) Protective microbiota: From localized to long-reaching co-immunity. Front. Immunol. 6, 1678 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kho Z.Y. and Lal S.K. (2018) The human gut microbiome - a potential controller of wellness and disease. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1835 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahani-Sherafat S., Alebouyeh M., Moghim S., Amoli H.A. and Ghasemian-Safaei H. (2018) Role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer; A review article. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 11, 101–109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein R.S., Recco R.A., Catalano M.T., Edberg S.C., Casey J.I. and Steigbigel N.H. (1977) Association of Streptococcus bovis with carcinoma of the colon. N. Engl. J. Med. 297, 800–802 10.1056/NEJM197710132971503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huycke M.M., Abrams V. and Moore D.R. (2002) Enterococcus faecalis produces extracellular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide that damages colonic epithelial cell DNA. Carcinogenesis 23, 529–536 10.1093/carcin/23.3.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu S., Rhee K.J., Zhang M., Franco A. and Sears C.L. (2007) Bacteroides fragilis toxin stimulates intestinal epithelial cell shedding and γ-secretase-dependent E-cadherin cleavage. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1944–1952 10.1242/jcs.03455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdulamir A.S., Hafidh R.R. and Bakar F.A. (2010) Molecular detection, quantification, and isolation of Streptococcus gallolyticus bacteria colonizing colorectal tumors: Inflammation-driven potential of carcinogenesis via IL-1, COX-2, and IL-8. Mol. Cancer 9, 249 10.1186/1476-4598-9-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuevas-Ramos G., Petit C.R., Marcq I., Boury M., Oswald E. and Nougayrède J.P. (2010) Escherichia coli induces DNA damage in vivo and triggers genomic instability in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11537–11542 10.1073/pnas.1001261107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ray K. (2011) Colorectal cancer: Fusobacterium nucleatum found in colon cancer tissue - could an infection cause colorectal cancer? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 622 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osman M.A., Neoh H., Ab Mutalib N.S., Chin S.F., Mazlan L., Raja Ali R.A.et al. (2021) Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Akkermansia muciniphila as a four-bacteria biomarker panel of colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 11, 2925 10.1038/s41598-021-82465-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas A.M., Manghi P., Asnicar F., Pasolli E., Armanini F., Zolfo M.et al. (2019) Metagenomic analysis of colorectal cancer datasets identifies cross-cohort microbial diagnostic signatures and a link with choline degradation. Nat. Med. 25, 667–678 10.1038/s41591-019-0405-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wirbel J., Pyl P.T., Kartal E., Zych K., Kashani A., Milanese A.et al. (2019) Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 25, 679–689 10.1038/s41591-019-0406-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H., Chu M., Huang Z., Yang X., Ran S., Hu B.et al. (2017) Variations in oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 11773 10.1038/s41598-017-11779-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Leeuw M. and Duval M.X. (2020) The presence of periodontal pathogens in gastric cancer. Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 5, 87–96 10.14218/ERHM.2020.00024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao L., Zhou Y., Zhao R., Coker O.O.O., Zhang X., Chu E.S.et al. (2020) Parvimonas micra promotes intestinal tumorigenesis in conventional Apcmin/+ mice and in germ-free mice. Res. Square 10.21203/rs.3.rs-25974/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu J., Zhao L., Zhao R., Long X., Coker O.O. and Sung J.J.Y. (2019) The role of Parvimonas micra in intestinal tumorigenesis in germ-free and conventional APC Min/+ mice. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 531 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaney M.L. and Onderdonk A.B. (1997) Evaluation of the AnaeroPack system for growth of clinically significant anaerobes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35, 558–562 10.1128/jcm.35.3.558-562.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatta M.N.A., Mohamad Hanif E.A., Chin S.F. and Neoh H. (2021) Prerequisite evaluation of anaerobic settings for gut microbiome functional studies. J. Biomed. Transl. Res. 7, 5–7 10.14710/jbtr.v7i1.10129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long X., Wong C.C., Tong L., Chu E.S.H., Ho Szeto C., Go M.Y.Y.et al. (2019) Peptostreptococcus anaerobius promotes colorectal carcinogenesis and modulates tumour immunity. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 2319–2330 10.1038/s41564-019-0541-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Q., Tan H.T., Lim T.K., Khoo A., Lim K.H. and Chung M.C.M. (2014) iTRAQ analysis of colorectal cancer cell lines suggests drebrin (DBN1) is overexpressed during liver metastasis. Proteomics 14, 1434–1443 10.1002/pmic.201300462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee G.Y., Haverty P.M., Li L., Kljavin N.M., Bourgon R., Lee J.et al. (2014) Comparative oncogenomics identifies PSMB4 and SHMT2 as potential cancer driver genes. Cancer Res. 74, 3114–3126 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell R.V., Visnovska M., Biggs P.J., Schmeier S. and Frizelle F.A. (2017) Distinct gut microbiome patterns associate with consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 11590 10.1038/s41598-017-11237-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murdoch D.A. and Shah H.N. (1999) Reclassification of Peptostreptococcus magnus (Prevot 1933) Holdeman and Moore 1972 as Finegoldia magna comb. nov. and Peptostreptococcus micros (Prevot 1933) Smith 1957 as Micromonas micros comb. nov. Anaerobe 5, 555–559 10.1006/anae.1999.0197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tindall B.J. and Euzéby J.P. (2006) Proposal of Parvimonas gen. nov. and Quatrionicoccus gen. nov. as replacements for the illegitimate, prokaryotic, generic names Micromonas Murdoch and Shah 2000 and Quadricoccus Maszenan et Al. 2002, respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 2711–2713 10.1099/ijs.0.64338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koliarakis I., Messaritakis I., Nikolouzakis T.K., Hamilos G., Souglakos J. and Tsiaoussis J. (2019) Oral bacteria and intestinal dysbiosis in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4146 10.3390/ijms20174146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki M., Asaka T., Takemoto M. and Nakano T. (2020) Severe sepsis caused by Parvimonas micra identified using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing following patient death. IDCases 19, e00687 10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko J.H., Baek J.Y., Kang C.I., Lee W.J., Lee J.Y., Cho S.Y.et al. (2015) Bacteremic meningitis caused by Parvimonas micra in an immunocompetent host. Anaerobe 34, 161–163 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe T., Hara Y., Yoshimi Y., Fujita Y., Yokoe M. and Noguchi Y. (2020) Clinical characteristics of bloodstream infection by Parvimonas micra: Retrospective case series and literature review. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 578 10.1186/s12879-020-05305-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greten F.R. and Grivennikov S.I. (2019) Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 51, 27–41 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varricchi G., Senna G., Loffredo S., Bagnasco D., Ferrando M. and Canonica G.W. (2017) Reslizumab and eosinophilic asthma: One step closer to precision medicine? Front. Immunol. 8, 242 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alfaro C., Sanmamed M.F., Rodríguez-Ruiz M.E., Teijeira Á., Oñate C., González Á.et al. (2017) Interleukin-8 in cancer pathogenesis, treatment and follow-up. Cancer Treat. Rev. 60, 24–31 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng X.S., Li Y.F., Tan J., Sun B., Xiao Y.C., Fang X.B.et al. (2014) CCL20 and CXCL8 synergize to promote progression and poor survival outcome in patients with colorectal cancer by collaborative induction of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Lett. 348, 77–87 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goradel N.H., Heidarzadeh S., Jahangiri S., Farhood B., Mortezaee K., Khanlarkhani N.et al. (2019) Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: A mechanistic overview. J. Cell. Physiol. 3, 2337–2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He H., Shao X., Li Y., Gihu R., Xie H., Zhou J.et al. (2021) Targeting signaling pathway networks in several malignant tumors: Progresses and challenges. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 675675 10.3389/fphar.2021.675675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du Q. and Geller D.A. (2010) Cross-regulation between Wnt and NF-ΚB signaling pathways. For. Immunopathol. Dis. Therap. 1, 155–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X., Lin D., Lin Y., Chen H., Zou M., Zhong S.et al. (2017) Proteasome beta-4 subunit contributes to the development of melanoma and is regulated by MiR-148b. Tumour Biol. 39, 1010428317705767 10.1177/1010428317705767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H., He Z., Xia L., Zhang W., Xu L., Yue X.et al. (2018) PSMB4 overexpression enhances the cell growth and viability of breast cancer cells leading to a poor prognosis. Oncol. Rep. 40, 2343–2352 10.3892/or.2018.6588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voutsadakis I.A. (2008) The ubiquitin-proteasome system in colorectal cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782, 800–808 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y., Chen C., Yu T. and Chen T. (2020) Proteomic analysis of protein ubiquitination events in human primary and metastatic colon adenocarcinoma tissues. Front. Oncol. 40, 1684 10.3389/fonc.2020.01684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y. and Ciechanover A. (2015) The ubiquitin-proteasome system and activation of NF-ΚB: Involvement of the ubiquitin ligase KPC1 in P105 processing and tumor suppression. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2, e1054552 10.1080/23723556.2015.1054552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding F., Xiao H., Wang M., Xie X. and Hu F. (2014) The role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in cancer development and treatment. Front. Biosci. 19, 886–895 10.2741/4254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uehara I. and Tanaka N. (2018) Role of p53 in the regulation of the inflammatory tumor microenvironment and tumor suppresion. Cancers 7, 219 10.3390/cancers10070219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salon C., Brambilla E., Brambilla C., Lantuejoul S., Gazzeri S. and Eymin B. (2007) Altered pattern of Cul-1 protein expression and neddylation in human lung tumours: Relationships with CAND1 and cyclin E protein levels. J. Pathol. 213, 303–310 10.1002/path.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y., Chen H., Zhang J., Cheng A.S.L., Yu J., To K.F.et al. (2020) MCM family in gastrointestinal cancer and other malignancies: From functional characterization to clinical implication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1874, 188415 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dalal S.N., Yaffe M.B. and DeCaprio J.A. (2004) 14-3-3 family members act coordinately to regulate mitotic progression. Cell Cycle 3, 672–676 10.4161/cc.3.5.856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu H., Tian Y., Yuan X., Wu H., Liu Q., Pestell R.G.et al. (2015) The role of CD44 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer development. Onco. Targets Ther. 8, 3783–3792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X.L., Zhou J., Chen Z.R. and Chng W.J. (2015) P53 mutations in colorectal cancer- molecular pathogenesis and pharmacological reactivation. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 84–93 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang M., Gao Q., Chen Y., Li Z., Yue L. and Cao Y. (2019) PAK4, a target of MiR-9-5p, promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in colorectal cancer. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 24, 58 10.1186/s11658-019-0182-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H., Zhi H., Ma D. and Li T. (2017) MiR-217 promoted the proliferation and invasion of glioblastoma by repressing YWHAG. Cytokine 92, 93–102 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long N.P., Lee W.J., Huy N.T., Lee S.J., Park J.H. and Kwon S.W. (2016) Novel biomarker candidates for colorectal cancer metastasis: A meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Cancer Inform. 15, 11–17 10.4137/CIN.S40301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salt M.B., Bandyopadhyay S. and McCormick F. (2014) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition rewires the molecular path to PI3K-dependent proliferation. Cancer Discov. 4, 186–199 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guan Y., Zhu X., Liang J., Wei M., Huang S. and Pan X. (2021) Upregulation of HSPA1A/HSPA1B/HSPA7 and downregulation of HSPA9 were related to poor survival in colon cancer. Front. Oncol. 11, 749673 10.3389/fonc.2021.749673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S., Guo S., Li Z., Li Z., Li D. and Zhan Q. (2019) High expression of HSP90 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Peer J. 7, e7946 10.7717/peerj.7946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiong Z., Guo M., Yu Y., Zhang F., Ge M., Chen G.et al. (2016) Downregulation of AIF by HIF-1 contributes to hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colon cancer. Carcinogenesis 37, 1079–1088 10.1093/carcin/bgw089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded at http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24406.32320.