Abstract

Artificial molecular machines have captured the full attention of the scientific community since Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Fraser Stoddart, and Ben Feringa were awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The past and current developments in molecular machinery (rotaxanes, rotors, and switches) primarily rely on organic-based compounds as molecular building blocks for their assembly and future development. In contrast, the main group chemical space has not been traditionally part of the molecular machine domain. The oxidation states and valency ranges within the p-block provide a tremendous wealth of structures with various chemical properties. Such chemical diversity—when implemented in molecular machines—could become a transformative force in the field. Within this context, we have rationally designed a series of NH-bridged acyclic dimeric cyclodiphosphazane species, [(μ-NH){PE(μ-NtBu)2PE(NHtBu)}2] (E = O and S), bis-PV2N2, displaying bimodal bifurcated R21(8) and trifurcated R31(8,8) hydrogen bonding motifs. The reported species reversibly switch their topological arrangement in the presence and absence of anions. Our results underscore these species as versatile building blocks for molecular machines and switches, as well as supramolecular chemistry and crystal engineering based on cyclophosphazane frameworks.

Introduction

The last three decades have seen the rise of rationally designed synthetic molecular architectures with stimuli-controlled molecular-level motion. These advances have allowed humanity to build artificial structures that can control and exploit molecular-level motion, giving rise to a wide range of molecular machines and switches.1−7

There has been a wide range of reported examples of molecules, including catenanes and rotaxanes, where molecular motion is triggered by various stimuli (light,8−12 electrochemistry,13−18 pH,19−22 heat,23,24 solvent polarity,25,26 cation,27−29 anion binding,30−35 etc.). Despite the extraordinary progress already made, researchers have merely scratched the surface, and further developments are required to reach the level of competence/sophistication displayed by biological systems.36−40

Future molecular machines will require a multidisciplinary approach with inputs and expertise from other fields, which necessitates the development of molecular machinery based on main group backbones (i.e., based on non-carbon–carbon bonds). Over the last few decades, the field of main group chemistry has not only contributed to chemistry at large by providing important chemical concepts,41 but also has uncovered a wealth of catalytic systems42−44 and energy materials.45 However, its implementation in the area of molecular machines is still lagging behind their organic counterparts.

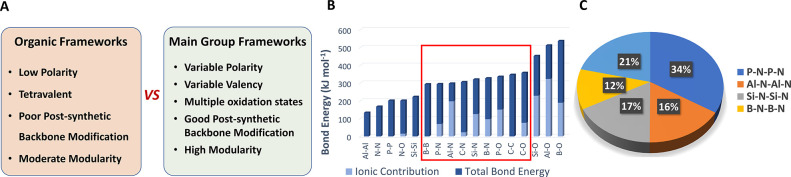

In contrast to carbon-based systems, where the tetravalent state dominates the chemistry, other main group elements display multiple valencies and oxidation states with very specific reactivity and chemical properties (Figure 1A). Therefore, main group elements provide a wealth of unexplored backbones in the molecular machinery space, which we envision will impact how future molecular machines are designed.

Figure 1.

Comparison between organic and main group frameworks. (A) Typical properties of organic and main group backbones. (B) Total bond energy and ionic contribution for selected homoatomic and heteroatomic bonds comprising p-block elements. (C) Percentage of crystallographically characterized main group compounds comprising an A-B-A-B backbone (data obtained from CCDC database accessed on March 17, 2022).

However, before selecting a suitable main group system, the kinetic and thermodynamic stability of the non-carbon bonds must be considered (Figure 1B). The ideal main group frameworks are those with high bond energies (relative to carbon–carbon bonds) and display low bond polarities (Figure 1B).46 Within this context, among the potential main group families (i.e., P–N, Al–N, Si–N, B–N, P–O, etc.), P–N bonds fulfill both requirements, displaying comparable bond energies to carbon-based species (i.e., C–C, C–O, and C–N), as well as a low polarity. In addition, P–N-based backbones are the largest family of main group compounds displaying these requirements, making them the ideal frameworks for proof-of-concept studies (Figure 1C).

Among the molecular motifs comprising P–N bonds, P2N2 cyclodiphosphazane building blocks are capable of forming a broad range of cyclic and acyclic frameworks. These main group systems47 have shown to be excellent ligands for metal coordination48−55 and versatile modular building blocks for the construction of larger molecules for biological applications and supramolecular chemistry.56−65

A powerful motif used in the design of molecular machines,66−70 organocatalyst,71,72 anion sensors,73 anion transporters inter alia(74) is the hydrogen bond (HB). In particular, excellent HB donors such as ureas, thioureas, and squaramides75−78 are commonly used building blocks in molecular machines due to their bifurcated NH geometry and the tunable acidity of their amino protons via substituent modification.1,2,79

More recently, it has been demonstrated that cyclodiphosphazanes,47 P2N2 frameworks, are versatile HB donors that rival ureas, thioureas, and even squaramides, thanks to their increased bite angles.63−65 In addition, these species have been shown to effectively bind to small molecules [e.g., acetone, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and dimethylformamide] and be versatile building blocks for the engineering of high-order ternary and quaternary multicomponent cocrystals, which further broadens the scope of their applications in supramolecular applications and crystal engineering.59,80

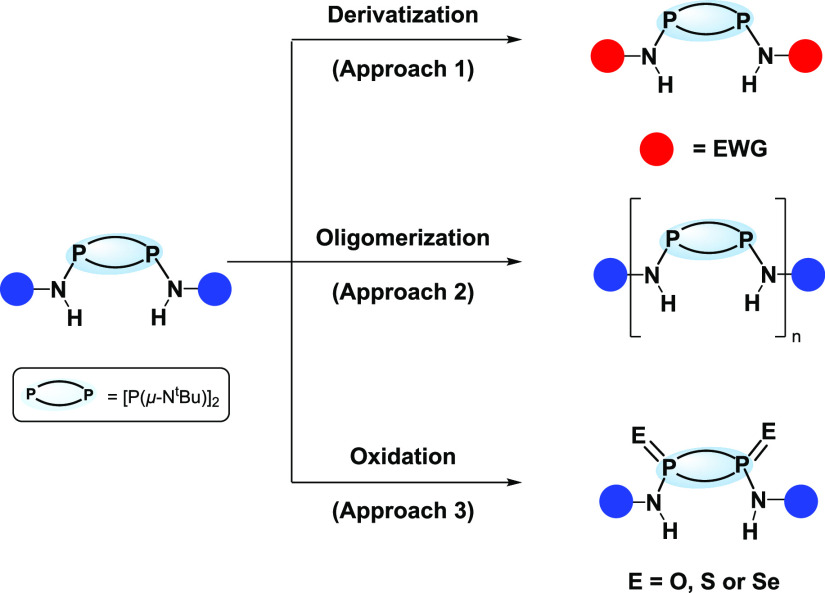

Common strategies for improving the HB donor ability of urea and thioureas for their use as building blocks in both supramolecular chemistry and molecular machines are to increase (i) the complexity (i.e., adding extra HB functionalities, electron-withdrawing groups, etc.) of the substituents (Approach 1)81−83 or (ii) the number of repeating units of urea/thiourea crafted within the molecular backbone (Approach 2).84−90 Both strategies aim to increase HB ability, translating into better binding affinities and performance versus their classical counterparts.

Similar approaches can—in theory—be applied to P2N2 species (see Scheme 1). The influence of varying substituents has been studied for monomeric species (i.e., Approach 1).63−65 However, in contrast to carbon-based frameworks, it was found that effective HB abilities are only observable after the PIII2N2 backbone of choice is oxidized to PV2N2 (i.e., from PIII to PV). Notably, the oxidation process PIII2N2 to PV2N2 enables further fine-tuning of their HB ability (Approach 3), since various chalcogen elements (i.e., O, S, or Se) can be readily installed onto the backbone during a simple post-synthetic oxidation step.91−96 Notably, this “gain of function” feature—that is, the one-step installation of chalcogen elements—is not readily available for widely used carbon-based building blocks, which limits the fine-tuning of their properties and reduces their scope through post-synthetic backbone alteration.

Scheme 1. Strategies for Improving the HB Donor Ability of P2N2 Species.

In terms of increasing the number of repeating units to form oligomeric P2N2 species (i.e., Approach 2), this approach has been traditionally impaired due to the lack of selectivity between cyclic and acyclic oligomeric PIII2N2 species containing NH moieties.97−99 However, novel topologically tunable N-bridged acyclic oligo-PIII2N2 (i.e., dimeric and trimeric) species have been recently reported.100 The latter comprise different substituents (e.g., H, iPr, Ph, and tBu) at the two backbone bridging positions, which determine their final topological conformation. This report represents the first rational selection of different topological conformations using non-covalent interactions in the phosphazane PIII2N2 family. In addition, theoretical studies predict acyclic dimeric- and trimeric-PV2N2 species as topologically tunable frameworks with superior halide receptors with increased binding ability toward chlorides compared to their monomeric counterparts (i.e., squaramide and thiourea R21(8) type building blocks).100 It is worth noting that anion binding has been successfully used as a chemical stimulus in a wide range of molecular switches.30,31,33,101−103

The previously demonstrated rational selection of different topological conformations in dimeric and trimeric acyclic PIII2N2 phosphazane species, combined with the predicted superior halide binding ability of PV2N2, suggests their suitability as potential main group building blocks toward chemically responsive frameworks based on a fully inorganic backbone.

Herein, we report the synthesis of novel acyclic NH-bridged dimeric-PV2N2 species and demonstrate them as effective molecular switches activated by anionic species. This new family of NH-bridged PV2N2 molecular switches feature both topological responsiveness to external anion stimuli and adaptable cavity size. We envision that these unique properties will enable oligomeric cyclodiphosphazane frameworks to play a crucial role in designing molecular machines, host–guest systems, and supramolecular chemistry in the future.

Results

Synthesis and Characterization of Acyclic Dimeric-PV2N2 Molecular Switches

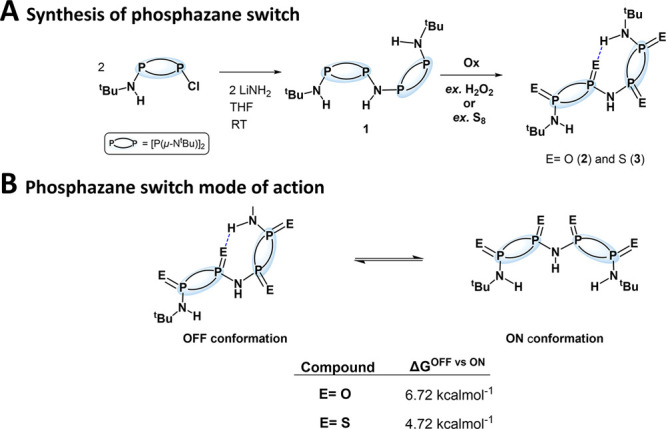

The basic building block in our studies, compound 1, can be obtained via the single-step reaction of Cl[P(μ-NtBu)]2NHtBu with LiNH2 in THF at room temperature (Scheme S1).100,104 This recently reported synthetic methodology allows for a simple and straightforward route to NH-bridged acyclic dimeric-PIII2N2.100

Compound 1 was then oxidized to form the NH-bridged acyclic dimeric-PV2N2 counterpart to enable HB ability (Figure 2A). Treatment of 1 with six equivalents of H2O2, added dropwise at 0 °C, afforded its oxygen oxidized counterpart 2 (Scheme S2). The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 in CDCl3 exhibits three different NH signals at 3.63, 5.36, and 7.39 ppm and two different tert-butyl signals at 1.34 and 1.47 ppm for terminal positions, revealing the asymmetric nature of compound 2 (Figure S4). This suggests that compound 2 adopts a twisted exo,endo/exo,exo “S” conformation (i.e., 2OFF), in which both PV2N2 fragments are non-equivalent. This feature was attributed to the presence of intramolecular hydrogen bonding within the dimeric backbone. Furthermore, the 31P–{1H} NMR of 2 in CDCl3 also shows two heavily broadened signals at −1.11 and −6.66 ppm, which further suggests the existence of intramolecular P=O···H–N HB interactions in 2OFF (Figure S5).

Figure 2.

Synthesis of dimeric-PV2N2 species and their switch mode of action. (A) Synthetic route to phosphazane molecular switches. (B) Phosphazane switch OFF to ON (i.e., S to C) topological conformational change mode of action observed in solution for 2 and 3—the energy differences displayed were calculated by DFT using B3pw91/6-311 g(d,p) basis set.

Similarly, the overnight reaction of 1 with 4.2 equivalents of elemental sulfur in THF at room temperature furnished 3 (Scheme S3). In contrast to compound 2, the 1H NMR in CDCl3 for 3 reveals two NH signals at 4.12 and 5.16 ppm with a ratio of 2:1, while the two terminal tert-butyl groups are also equivalent, giving rise to only one signal at 1.44 ppm (Figure S9), suggesting an exo,exo/exo,exo “C” conformation (i.e., 3ON). However, compound 3 is expected to favor the 3OFF conformation ([3ON]/[3OFF] < 0.01%) according to density functional theory (DFT) calculations (vide infra, Figure 2, Figure 4, and Supporting Information). Therefore, the observed 1H NMR spectrum suggests a fluxional behavior of compound 3, with a rapid interconversion between 3ON and 3OFF. In addition, the 31P–{1H} NMR spectrum shows significantly sharper signals at 34.28 and 41.93 ppm relative to compound 2 (Figure S11), supportive of much weaker HB interactions with the P=S moiety.

Figure 4.

Calculated binding energies and preferred switch model for the 3OFF and 3ON solvates with DMSO and Cl anions at B3pw91/6-311 g(d,p) level of theory.

To confirm this hypothesis, variable temperature (VT) 1H NMR of 3 was performed, and two broad singlets at 3.34 and 5.15 ppm in a 1:2 ratio were observed at 213 K (cf. 4.12 and 5.16 ppm in a 2:1 ratio at RT, see Figure S14), which is indicative of a “S” topological arrangement (i.e., 3OFF). The presence of only two resonances in the NMR spectrum—instead of the three that would have been expected—combined with the observed inversion of the signal ratio, is attributed to small differences in the chemical shift, which results in the coincidental overlapping of two of the three distinct NH environments in 3OFF. Determination of the energy barrier of rotation based on the VT 1H NMR data (TC = 253 K, Δν = 722 Hz) suggests a relatively low rotation barrier between the 3ON and 3OFF conformations (∼11.0 kcal·mol–1). This experimental value is in good agreement with the DFT-calculated rotation barrier of 12.57 kcal·mol–1 (Figure 2B, see Figures S15 and S69 for details), where the 3ON conformer is calculated to be 4.72 kcal·mol–1 above the 3OFF counterpart (Figures 2B and S69).

To confirm if the same ON/OFF conformational changes can be observed for compound 2, high-temperature NMR studies were performed. Upon heating to 333 K, the signal displayed by compound 2 broadened substantially, as the equilibrium between 2ON and 2OFF approaches the NMR timescale (Figure S12). However, the coalescence temperature could not be achieved in the solvent system used (b.p. CDCl3 = 334.5 K), indicating that compound 2 has a higher ON/OFF rotational barrier than 3. To further confirm this, the same experiment was conducted in tetrachloroethane-d2, allowing for higher temperatures to be achieved. Indeed, fluxional behavior was observed upon heating to 413 K, with terminal NH resonances converging into a single signal at 4.08 ppm (cf. 3.62 and 5.42 ppm at RT, see Figure S13). Calculations based on coalescence temperature achieved in 1H high-temperature NMR studies (TC = 353 K, Δν = 720 Hz) saw higher rotational barrier energy between 2ON and 2OFF conformations (∼15.6 kcal·mol–1) as compared to 3, which further confirms our hypothesis. The different ON/OFF behavior between compounds 2 and 3 observed is attributed to the different HB strengths present in these species, where only the stronger P=O···H–N is sufficient at room temperature to prevent fluxionality.

To assess the effect of HB donor/acceptor solvents on 2OFF, where the OFF conformation is “locked” in place by intramolecular HB interactions, the compound was dissolved in methanol-d4, and its 1H NMR spectrum was recorded. The spectrum shows the absence of NH signals, which is attributed to peak broadening due to HB interactions of the amino protons with the methanol-d4. Notably, there is only one resonance at 1.38 ppm corresponding to terminal tert-butyl groups (cf. δ 1.34 and 1.47 ppm in CDCl3), which suggests that competing HB interactions disrupt the intramolecular P=O···HNtBu HB in 2, allowing for fluxional behavior in methanol-d4 (Figures S4–S8).

Despite the successful synthesis of 2 and 3, the reaction of 1 with 4.2 equivalents of elemental selenium in THF did not result in the formation of expected selenium-oxidized acyclic dimeric-PV2N2, [(μ-NH){PSe(μ-NtBu)2PSe(NHtBu)}2] (4) (Scheme S4). Instead, the in situ 31P–{1H} NMR spectrum reveals a mixture of products. Further insights on the reaction were gained from diffraction quality crystals obtained from a concentrated toluene solution, where [H2N[P(Se)(μ-NtBu)]2NHtBu] (4a) was identified as one of the products (Figure S67). Notably, this compound is the first crystallographically characterized asymmetrically substituted monomeric-PV2N2 containing an −NH2 moiety.

An important property for implementing main group frameworks in molecular machinery is their overall stability under ambient conditions. Compounds 2 and 3 both display high air and hydrolytic stability, and can be bench-stored and handled under ambient atmospheric conditions.105−108 Hydrolytic studies of samples containing 2 and 3 each in 1:9 H2O/THF monitored via 31P–{1H} NMR showed no signs of degradation for up to 4 weeks, showcasing their robustness as extended phosphazane scaffolds for a multitude of supramolecular chemistry applications (Figures S16 and S17).105,106

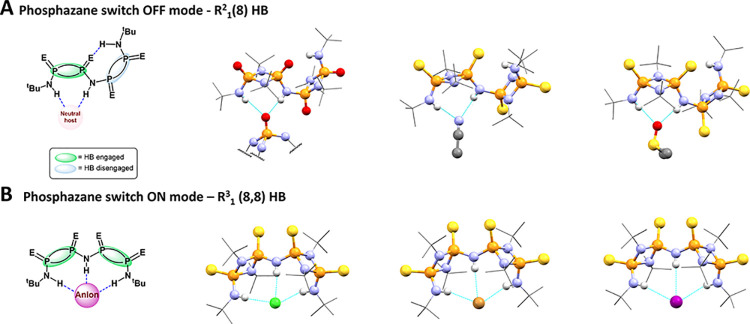

PV2N2 Switch OFF Mode: R21(8) Bifurcated HB to Neutral Guest Molecules

To further confirm the structures of compounds 2 and 3 and their ON/OFF topologies, single crystal X-ray diffraction studies were performed. These studies reveal both compounds adopting an OFF twisted topology in the solid state, comprising a R21(8) bifurcated hydrogen interactions. (Figures 3A, S59–S62).59,65

Figure 3.

Molecular switch binding modes to neutral and anionic guests. (A) Dimeric-PV2N2 switch OFF mode (3OFF) – R21(8). Solid-state structures of “2 ⊂ 2” (displaying a fragment of the supramolecular dimer in the solid state, left), 3 ⊂ Acetonitrile (middle), and 3 ⊂ DMSO (right), illustrating weak interactions with neutral molecules. Hydrogen atoms (except selected NH protons) and disorder were omitted for clarity. (B) Dimeric-PV2N2 switch ON mode (3ON) – R31(8,8). Solid-state structures of 3 ⊂ Cl– (left), 3 ⊂ Br– (middle), and 3 ⊂ I– (right). Hydrogen atoms (except selected NH protons), and disorder were omitted for clarity. For selected bond distances and expanded figures, see Supporting Information.

The crystal of 2 obtained from a THF solution displays strong intermolecular interactions, leading to the formation dimeric aggregate via R21(8) bifurcated HB interactions between the amino protons and the P=O group of two molecules of 2 (Figure S59). In chloroform (i.e., a solvent comprising of the HB donor), the same bimolecular aggregate is observed, as well as exogenous P=O···H–CCl3 HB interactions. In both structures, the observed HB bond distances are 2.87 to 3.19 Å, which is consistent with monomeric counterparts.65 In contrast to the formation of HB dimers, the solid-state structure of 3 reveals the formation of R21(8) bifurcated HB solvates (with MeCN and DMSO) (Figures S61 and S62). These types of HB interactions with neutral organic molecules, and their bond distances, are consistent with those observed in monomeric PV2N2 counterparts.59

The formation of dimers in 2—instead of monomeric solvates as observed for compound 3—is attributed to the preferential formation of strong bifurcated R21(8) HB with a P=O moiety over a molecule of THF. Overall, both compounds display an OFF conformation, where the second PV2N2 unit does not engage in intermolecular HB (Figure 3A), which demonstrates a preference for intramolecular R21(8) HB in the presence of neutral molecules over an ON R31(8,8) HB motif where all the NH groups are engaging in bonding.

To gain further insights into the different ON/OFF behavior, DFT studies at (B3pw91/6-311 g(d,p) level of theory) were performed. The binding energy for the coordination of a molecule of DMSO to 3OFF was calculated to be 12.90 kcal·mol–1. In contrast, the binding energy for the 3ON topological conformation was calculated to be 8.97 kcal·mol–1 relative to the individual molecules (Figure 4). The differences in stabilization between the ON/OFF HB motifs (ca. 4 kcal/mol) are attributed to the different strengths of the non-covalent interactions present (i.e., R21(8) vs P=S···H–N HB interactions; see Figures S69–S71 for non-covalent interactions). In the OFF conformation, one R21(8) HB and one P=S···H–N are present. In contrast, its ON counterpart displays a trifurcated HB interaction with two symmetric adjacent bifurcated R21(8) HB interactions “sharing” a HB donor to a common acceptor (i.e., in the same manner, adjacent angles are mathematically defined), which we define as a R31(8,8) interaction. The stronger intramolecular HB interaction in compound 2 ⊂ DMSO has also been computed, and the energy difference between the ON/OFF conformation is calculated to be ca. 7.6 kcal/mol (Table S6). In addition, we performed non-covalent interaction analyses for compounds 2 and 3 on their OFF conformation (Figure S71). Our analyses show that 2OFF displays stronger attractive intramolecular HB interactions than 3OFF, which further supports our hypothesis and is consistent with the experimental observations.

PV2N2 Switch ON Mode: R31(8,8) Trifurcated HB to Anions Hosts

As observed, interactions of 2 and 3 with small neutral organic molecules favor OFF conformations, displaying bifurcated R21(8) HB modes. However, the second PV2N2 unit does not engage in intermolecular HB, which is attributed to the presence of the intramolecular P=E···NH HB present in compounds 2 and 3.

Past reports on monomeric cyclodiphosphazane receptors have shown that strong HB guests, such as halide anions, favor the exo,exo conformation,80,100 which enables these species to act as R21(8) HB donors.60,64,65 This preference for the exo,exo (over the exo,endo) in the presence of halide HB acceptors has also been recently highlighted during the formation of high-order multicomponent cocrystals based on monomeric PV2N2 building blocks.80

The presence of an additional PV2N2 provides 2 and 3 with an additional degree of freedom (i.e., OFF vs ON conformations) and could potentially provide a superior performance toward anion binding and sensing if selectively switched ON. Moreover, rationally controlling rotatory motion around a single bond has been commonly used in molecular machines and switches using a wide range of organic (i.e., triptycyl, quinoline, napthyl moieties, etc.) and organometallic molecular architectures triggered by various chemical stimuli (e.g., protonation, anions, and cations, inter alia).1,2,79 We postulate that in contrast to what was observed for neutral molecules (i.e., MeCN and DMSO), where only the OFF conformation is observed, the second unit would switch ON in the presence of anionic hosts via the formations of higher-order trifurcated R31(8,8) HB interactions, hence fulfilling the conformational changes required to be classified as a molecular switch.40

This is further supported by theoretical calculations of 3ON and 3OFF with the chloride anion (see Figure 4). In contrast to what was calculated for 3 ⊂ DMSO, the preferred binding mode is reversed for chloride anions (64.09 vs 55.02 kcal·mol–1 for 3ON and 3OFF, respectively) with a difference in stabilization of 14.02 kcal·mol–1 favorable to the ON HB motif. The ON bonding mode is displayed across a halide anion triad (X = Cl–, Br–, and I–). In all cases, the 3ON ⊂ halide compounds exhibit low energies for such host–guest systems (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Calculated structures and binding energies for 3ON ⊂ X– host–guest adducts.

Moreover, excluding macrocycles, this type of adjacent and symmetrical HB interactions is rare64,109,110 and has only been previously described for C3V tripodal type of frameworks—never for linear molecules—making the herein reported molecular switch unique.

Hence, we proceeded to study the ON/OFF host–guest properties of 3 toward anions. Compound 3 was selected over 2 due to its lower rotation barrier and its better expected performance than 2 in anion binding based on previous reports on monomeric PV2N2 species.61,100

Indeed, cocrystals of 3 obtained with anionic halides (i.e., Cl–, Br–, and I–) display an ON topological conformation with a fully engaged bis-PV2N2 backbone effectively utilizing all three NH moieties in HB interaction with the negatively charged halide (Figure 3B). To our knowledge, this is the first example of trifurcated R31(8,8) HB in cyclodiphosphazane species. In addition, the ON/OFF molecular switch ability of the phosphazane host to selectively enable different HB modes to adapt to specific guests has never been reported for inorganic frameworks.

Remarkably, 3ON also exhibits the ability to vary its cavity size by pivoting around the central NH moiety. This enables the compound to readily accommodate group 17 anions of different sizes, with little distortion to its framework (vide infra), which highlights its potential to respond to a broad range of differently sized anions. In contrast, such topological flexibility was not observed in its cyclic counterparts due to its rigid nature, limiting its supramolecular interactions to smaller guests.111−114 Hence, dimeric-PV2N2 species represent a promising framework with properties that are unique and complimentary to existing currently reported organic-based anion receptors and molecular switches.

Broad Response PV2N2 Switch ON Mode: R31(8,8) Trifurcated HB Anion Binding Abilities with Complex Polyatomic Anions

The ability of 3 to switch ON the R31(8,8) trifurcated HB mode in response to anions showcases the potential of these species to act as high anion affinity molecular switches in supramolecular and chemically responsive architectures. To illustrate this, we titrated 3 with increasing amounts of Cl–. The gradual addition of tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBACl) to a solution of 3 in CDCl3 displayed new resonances corresponding to host–guest adduct 3ON ⊂ Cl–, indicating negligible exchange of chloride ions between host molecules, with full conversion into 3ON ⊂ Cl– occurring at approximately two equivalents of TBACl. Due to these slow exchanges, the data obtained of 3ON with Cl– was not suitable to be fitted into a 1:1 binding isotherm model. Instead, the NH resonances were estimated using a concentration-weighted average of free host and host–guest complex, which was subsequently fitted into the 1:1 model.115 Using this method, the binding constant was estimated to be KA = 192.92 ± 81.89 M–1 (Figure S31).

To demonstrate the previously proposed broad applicability of our system, larger monoatomic anions (i.e., larger halides) and polyatomic complex anions were used, namely, I–, HSO4–, and NO3– (i.e., TBAI, TBAHSO4, and TBANO3, respectively). In these studies, the addition of increasing amounts of anionic species displayed a gradual downfield shift of NH resonances. This downfield shift is representative of anion binding to the NH sites present in 3ON and indicative of a rapid anion exchange between molecules of 3. The data obtained throughout the NMR titrations for each of these species were fitted into a 1:1 binding isotherm model.115,116 The binding constants obtained were 5.17 ± 0.13 (TBAI), 9.48 ± 0.25 (TBAHSO4), and 20.39 ± 1.17 M–1 (TBANO3). See Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Experimental Binding Constants of 3 and its Monomeric Counterparts with Different Monoatomic and Polyatomic Anionsa.

For theoretical calculations that assess the relative binding strengths of dimeric and monomeric P2VN2 species as well as urea derivatives, see Tables S8 and S9.

Estimated based on concentration-weighted average of [H0] and [HG];115 for details, see Figure S31.

N.D. = not determined.

Unfortunately, NMR titrations of 3 with Br– displayed extensive broadening of the NH resonances of the 3ON ⊂ Br– adduct at lower concentrations, which was attributed to a guest exchange rate within NMR timescales. To corroborate this assumption, NMR spectroscopy of 3ON with 0.5 equivalents of TBABr was conducted in CDCl3 at 223 K. The low temperature 1H NMR spectrum shows clear NH signals at 5.87 and 8.61 ppm, resulting from a lower exchange rate at 223 K, further supporting our hypothesis (Figure S18). As a result, the data collected are unsuitable to be fitted either in the isotherm binding model or estimated via the concentration-weighted average of free host and host–guest complex; thus, the binding affinity of 3ON to Br– was not determined.

To assess the relative binding strength of 3 to Br– with respect to the other anions studied, a series of competitive binding studies involving 3 in the presence of two different anions were conducted using ESI-MS operated in negative mode (see Figures S20–29). From our results, a clear preference toward smaller halides like Cl– and Br– was observed. The binding of 3 toward the anions tested displays a relative binding strength of Cl– > Br– > I– ≈ NO3– ≈ HSO4–.

The distinct interaction of 3ON with different halides is also observed in the solid state. The solid-state structures of 3ON ⊂ Cl–, 3ON ⊂ Br–, and 3ON ⊂ I– display an increasing N···X– distance with increased halide size, illustrating a cavity capable of adapting to different-sized hosts while still showing good guest binding affinities. Notably, compound 3 exhibits at least twofold higher binding affinities to the anions studied (ca. 5–192 M–1) when compared to monomeric PV2N2 species (ca. 0.5–6 M–1; see Table 1), with binding affinity toward Cl– approximately 40 times that of 4m. This can be attributed to both the increased number of HB donors and larger cavity present in 3, which can accommodate larger anions (i.e., I–, HSO4–, and NO3–). The cavity displays a steady increase of the terminal N···N distance on descending the group: 3ON ⊂ Cl– (6.272 Å) < 3ON ⊂ Br– (6.410 Å) < 3ON ⊂ I– (6.611 Å). Such a feature is also reminiscent of the macrocyclic pentamer [{P(μ-NtBu)}2(NH)]5, distorting its planar structure to host larger halides.114 However, in contrast to 3, this macrocycle is not known to accommodate larger complex anions (i.e., HSO4– or NO3–), likely due to the sterically encumbered and rigid nature of its cavity. In addition, simple ortho-phenylenediamine bridged bis-ureas and bis-thioureas have been demonstrated to exhibit low binding affinity toward Br– anion, whereas 3 displays good binding to Br– as evident through experimental results and solid-state structures.86

Theoretical binding energies calculated at the B3pw91/6-311 g(d,p) theory level for 3ON ⊂ X– were consistent with the experimental binding trend, alongside displaying higher binding strengths when compared to monomeric PV2N2 species, as well as monomeric urea derivatives (Tables S8 and S9). The trend obtained is slightly overestimated due to the absence of counterions to reduce computational load (Figure 5). Similarly, the observed experimental binding trend is consistent with the electrostatic potential trend of the various mono- and polyatomic anions studied (Figure 6A). In addition, electrostatic potential (ESP) analysis of 3ON displays a positive potential within the trifurcated cavity, along with negative potential around the P=S moiety (Figure 6B), indicating a polarized N–H system favoring anion complexation, consistent with our results.

Figure 6.

ESP surfaces of various mono- and polyatomic anions (A) and compound 3 (B) plotted on the electronic density with isovalue = 0.01.

PV2N2 Switch ON/OFF Reversibility: R21(8) Bifurcated ↔ R31(8,8) Trifurcated Transitions

Given the OFF/ON modes observed, we hypothesize that these systems are topologically responsive and can regain their original topology once the chemical stimulus is withdrawn. This would thus provide the first example of a fully reversible molecular switch in the main group arena. Due to the distinct differences between 2OFF and 2ON observed throughout our studies, the reversibility of bifurcated and trifurcated transitions was probed using 2 as a model.

However, full reversibility can only be fully demonstrated when the host is able to return to its initial topological state upon removal of the chemical stimulus. For this purpose, an excess of five equivalents of TBACl was added to a solution of 2 in CDCl3. As expected, the original NH resonances transform into two signals at 5.29 and 8.38 ppm, indicating a halide-induced OFF to ON topological transformation (Figure 7A; see Figure S19 for more details). To prove reversibility, the halide anion guest was removed from the 2ON host. The addition of five equivalents of NaPF6 to this solution resulted in an anion exchange, which is accompanied by the precipitation of insoluble NaCl as byproduct and the return to the 2OFF topological conformation. The OFF topology was confirmed by in situ 1H NMR of the mixture, which was illustrated by the presence of the three characteristic −NH signals at approximately the same chemical shifts (Figure 7B). Further addition of five equivalents of TBACl results in 2ON topology again, thus demonstrating the reversibility of the main group molecular switch.

Figure 7.

Molecular switch reversibility studies. (A) Characteristic signals corresponding to 2ON and 2OFF. (B) Partial 1H NMR spectra displaying two cycles of the reversible ON/OFF switching modes.

Conclusions

A novel molecular chemically responsive switch based on a fully inorganic backbone (i.e., carbon-free backbone) has been demonstrated for the first time. The reported NH-bridged acyclic dimeric cyclodiphosphazane molecular switches, [(μ-NH){PE(μ-NtBu)2PE(NHtBu)}2] (E = O and S), display an anion-responsive bimodal bifurcated R21(8) to trifurcated R31(8,8) hydrogen bonding transitions.

In contrast to conventional organic frameworks where carbon atoms display fixed valency and oxidation states, the reported parent PIIIN backbone readily gives rise to two different PVN species with distinct switching energy barriers (i.e., O vs S derivatives) via a single synthetic backbone modification step, which is enabled by the readily accessible variable oxidation states.

In addition, the reported species display a higher affinity toward anion species than their monomeric counterparts (see Supporting Information)—previously described in the literature as excellent alternatives to squaramides and thioureas—with a topologically responsive and adaptable cavity size.

Finally, our work serves as a proof of concept to highlight main group frameworks as powerful chemically responsive switches. Apart from being excellent anion receptors/sensors, we believe that such frameworks would give rise to potential applications such as anion-activated molecular tweezers or anion-responsive materials and polymers, when implemented as building blocks in combination with existing well-established systems. Therefore, we envision main group elements playing a key role in supramolecular chemistry through the design of carbon-free and hybrid (i.e., organic/inorganic) molecular machinery and host–guest systems in the near future.

Acknowledgments

F.G. would like to thank Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR) AME IRG (A1783c0003 and A2083c0050), MOE AcRF Tier 1 (M4011709) and NTU start-up grant (M4080552). F.G. also thanks the support of Fundación para el Fomento en Asturias de la Investigación Científica Aplicada y la Tecnología (FICYT) through the Margarita Salas Senior Program (AYUD/2021/59709) and the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion via the Proyectos de Generación De Conocimiento 2021 (PID2021-127407NB-I00 and RED2022-134074-T). F.G. would like to thank Monash University for the affiliate position. J.K.C. acknowledges the support of the Australian Research Council through DP1901012036. M.C.S. would like to thank the Ministry of Education Singapore under the AcRF Tier 1 (2019-T1-002-066) (RG106/19) (2018-T1-001-176) (RG18/18), A*STAR (A1883c0006), and NTU (04INS000171102C230) for financial support. J.D. thanks COMPUTAEX for granting access to LUSITANIA supercomputing facilities.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c12713.

Author Contributions

# G.H. and S.J.I.P. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

In memory of Professor Mary McPartlin.

Supplementary Material

References

- Erbas-Cakmak S.; Leigh D. A.; McTernan C. T.; Nussbaumer A. L. Artificial Molecular Machines. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 10081–10206. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E. R.; Leigh D. A. Rise of the Molecular Machines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10080–10088. 10.1002/anie.201503375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun A.; Banaszak M.; Astumian R. D.; Stoddart J. F.; Grzybowski B. A. Great Expectations: Can Artificial Molecular Machines Deliver on Their Promise?. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 19–30. 10.1039/c1cs15262a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart J. F. Mechanically Interlocked Molecules (MIMs)—Molecular Shuttles, Switches, and Machines (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 56, 11094–11125. 10.1002/anie.201703216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feringa B. L. The Art of Building Small: From Molecular Switches to Motors (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11060–11078. 10.1002/anie.201702979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage J. From Chemical Topology to Molecular Machines (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11080–11093. 10.1002/anie.201702992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage J. P.; Gaspard P.. From Non-Covalent Assemblies to Molecular Machines, 2010.

- Koumura N.; Zijlstra R. W. J.; van Delden R. A.; Harada N.; Feringa B. L. Light-Driven Monodirectional Molecular Rotor. Nature 1999, 401, 152–155. 10.1038/43646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelkema R.; Pollard M. M.; Vicario J.; Katsonis N.; Ramon B. S.; Bastiaansen C. W. M.; Broer D. J.; Feringa B. L. Nanomotor Rotates Microscale Objects. Nature 2006, 440, 163–163. 10.1038/440163a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klok M.; Boyle N.; Pryce M. T.; Meetsma A.; Browne W. R.; Feringa B. L. MHz Unidirectional Rotation of Molecular Rotary Motors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10484–10485. 10.1021/ja8037245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure B. A.; Rack J. J. Two-Color Reversible Switching in a Photochromic Ruthenium Sulfoxide Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8556–8558. 10.1002/anie.200903553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockus N. V.; Rabinovich D.; Petersen J. L.; Rack J. J. Femtosecond Isomerization in a Photochromic Molecular Switch. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1458–1461. 10.1002/anie.200703677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNitt K. A.; Parimal K.; Share A. I.; Fahrenbach A. C.; Witlicki E. H.; Pink M.; Bediako D. K.; Plaisier C. L.; Le N.; Heeringa L. P.; Griend D. A. V.; Flood A. H. Reduction of a Redox-Active Ligand Drives Switching in a Cu(I) Pseudorotaxane by a Bimolecular Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1305–1313. 10.1021/ja8085593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durola F.; Lux J.; Sauvage J. A Fast-Moving Copper-Based Molecular Shuttle: Synthesis and Dynamic Properties. Chemistry 2009, 15, 4124–4134. 10.1002/chem.200802510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X.; Zang Y.; Zhu L.; Low J. Z.; Liu Z.-F.; Cui J.; Neaton J. B.; Venkataraman L.; Campos L. M. A Reversible Single-Molecule Switch Based on Activated Antiaromaticity. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, eaao2615 10.1126/sciadv.aao2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzato C.; Nguyen M. T.; Kim D. J.; Anamimoghadam O.; Mosca L.; Stoddart J. F. Controlling Dual Molecular Pumps Electrochemically. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9325–9329. 10.1002/anie.201803848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Frasconi M.; Liu W.-G.; Young R. M.; Goddard W. A.; Wasielewski M. R.; Stoddart J. F. Electrochemical Switching of a Fluorescent Molecular Rotor Embedded within a Bistable Rotaxane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11835–11846. 10.1021/jacs.0c03701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Qiu Y.; Liu W.-G.; Chen H.; Shen D.; Song B.; Cai K.; Wu H.; Jiao Y.; Feng Y.; Seale J. S. W.; Pezzato C.; Tian J.; Tan Y.; Chen X.-Y.; Guo Q.-H.; Stern C. L.; Philp D.; Astumian R. D.; Goddard W. A.; Stoddart J. F. An Electric Molecular Motor. Nature 2023, 613, 280–286. 10.1038/s41586-022-05421-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaveney C. M.; Leigh D. A. Shuttling through Anion Recognition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1222–1224. 10.1002/anie.200353248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dial B. E.; Pellechia P. J.; Smith M. D.; Shimizu K. D. Proton Grease: An Acid Accelerated Molecular Rotor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3675–3678. 10.1021/ja2120184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrizzi L.; Foti F.; Licchelli M.; Maccarini P. M.; Sacchi D.; Zema M. Light-Emitting Molecular Machines: PH-Induced Intramolecular Motions in a Fluorescent Nickel(II) Scorpionate Complex. Chemistry 2002, 8, 4965–4972. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbas-Cakmak S.; Fielden S. D. P.; Karaca U.; Leigh D. A.; McTernan C. T.; Tetlow D. J.; Wilson M. R. Rotary and Linear Molecular Motors Driven by Pulses of a Chemical Fuel. Science 2017, 358, 340–343. 10.1126/science.aao1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen J. O.; Perkins J.; Becher J.; Stoddart J. F. Slow Shuttling in an Amphiphilic Bistable [2]Rotaxane Incorporating a Tetrathiafulvalene Unit. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1216–1221. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasberry R. D.; Wu X.; Bullock B. N.; Smith M. D.; Shimizu K. D. A Small Molecule Diacid with Long-Term Chiral Memory. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2599–2602. 10.1021/ol900955q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso I.; Burguete M. I.; Luis S. V. A Hydrogen-Bonding-Modulated Molecular Rotor: Environmental Effect in the Conformational Stability of Peptidomimetic Macrocyclic Cyclophanes. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 2242–2250. 10.1021/jo051974i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhez C.; Lameiras P.; Berber H. Intramolecular OH/π versus C–H/O H-Bond-Dependent Conformational Control about Aryl–C(Sp3) Bonds in Cannabidiol Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 6855–6859. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht-Gary A. M.; Saad Z.; Dietrich-Buchecker C. O.; Sauvage J. P. Interlocked Macrocyclic Ligands: A Kinetic Catenand Effect in Copper(I) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 3205–3209. 10.1021/ja00297a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sacristán-Martín A.; Barbero H.; Ferrero S.; Miguel D.; García-Rodríguez R.; Álvarez C. M. ON/OFF Metal-Triggered Molecular Tweezers for Fullerene Recognition. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 11013–11016. 10.1039/d1cc03451k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittel M.; De S.; Pramanik S. Reversible ON/OFF Nanoswitch for Organocatalysis: Mimicking the Locking and Unlocking Operation of CaMKII. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3832–3836. 10.1002/anie.201108089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. G.; Peck E. M.; Kramer P. J.; Smith B. D. Squaraine Rotaxane Shuttle as a Ratiometric Deep-Red Optical Chloride Sensor. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2557–2563. 10.1039/c3sc50535a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero A.; Swan L.; Zapata F.; Beer P. D. Iodide-Induced Shuttling of a Halogen- and Hydrogen-Bonding Two-Station Rotaxane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11854–11858. 10.1002/anie.201407580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.-C.; Lai C.-C.; Chiu S.-H. A Guanidinium Ion-Based Anion- and Solvent Polarity-Controllable Molecular Switch. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 613–616. 10.1021/ol802638k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence G. T.; Pitak M. B.; Beer P. D. Anion-Induced Shuttling of a Naphthalimide Triazolium Rotaxane. Chemistry 2012, 18, 7100–7108. 10.1002/chem.201200317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corra S.; de Vet C.; Groppi J.; Rosa M. L.; Silvi S.; Baroncini M.; Credi A. Chemical On/Off Switching of Mechanically Planar Chirality and Chiral Anion Recognition in a [2]Rotaxane Molecular Shuttle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9129–9133. 10.1021/jacs.9b00941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helttunen K. Anion Responsive Molecular Switch Based on a Doubly Strapped Calix[4]Pyrrole. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200647 10.1002/ejoc.202200647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular Motors; Schliwa M., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell D.Bionanotechnology – Lessons from Nature; Wiley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. J.; Juluri B. K. Biological and Biomimetic Molecular Machines. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 107–124. 10.2217/17435889.3.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasbas M. N.; Sahin E.; Erbas-Cakmak S. Bio-Inspired Molecular Machines and Their Biological Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 443, 214039 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan A. The Future of Molecular Machines. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 347. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers T.; Konu J. The Future Of Main Group Chemistry. Comments Inorg. Chem. 2009, 30, 131–176. 10.1080/02603590903385752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melen R. L. Frontiers in Molecular p-Block Chemistry: From Structure to Reactivity. Science 2019, 363, 479–484. 10.1126/science.aau5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weetman C.; Inoue S. The Road Travelled: After Main-Group Elements as Transition Metals. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 4213–4228. 10.1002/cctc.201800963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C.; Koutsantonis G. A. Modern Main Group Chemistry: From Renaissance to Revolution. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 1115–1117. 10.1071/ch13429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirscher M.; Yartys V. A.; Baricco M.; von Colbe J. B.; Blanchard D.; Bowman R. C.; Broom D. P.; Buckley C. E.; Chang F.; Chen P.; Cho Y. W.; Crivello J.-C.; Cuevas F.; David W. I. F.; de Jongh P. E.; Denys R. V.; Dornheim M.; Felderhoff M.; Filinchuk Y.; Froudakis G. E.; Grant D. M.; Gray E. MacA.; Hauback B. C.; He T.; Humphries T. D.; Jensen T. R.; Kim S.; Kojima Y.; Latroche M.; Li H.-W.; Lototskyy M. V.; Makepeace J. W.; Møller K. T.; Naheed L.; Ngene P.; Noréus D.; Nygård M. M.; Orimo S.; Paskevicius M.; Pasquini L.; Ravnsbæk D. B.; Sofianos M. V.; Udovic T. J.; Vegge T.; Walker G. S.; Webb C. J.; Weidenthaler C.; Zlotea C. Materials for Hydrogen-Based Energy Storage – Past, Recent Progress and Future Outlook. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 827, 153548 10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.153548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H.; Plajer A. J.; Garcia-Rodriguez R.; Singh S.; Wright D. S. Designing the Macrocyclic Dimension in Main Group Chemistry. Chemistry 2018, 24, 3073–3082. 10.1002/chem.201705230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishna M. S. Cyclodiphosphazanes: Options Are Endless. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 12252–12282. 10.1039/c6dt01121g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishna M. S.; Sreenivasa R. V.; Krishnamurthy S. S.; Nixon J. F.; Laurent J. C. T. R. B. S. S. Coordination Chemistry of Diphosphinoamine and Cyclodiphosphazane Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1994, 129, 1–90. 10.1016/0010-8545(94)85018-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthnag G. S.; Mague J. T.; Balakrishna M. S. Cyclodiphosphazane Appended with Pyridyl Functionalities: Reactivity, Transition Metal Chemistry and Structural Studies. J. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 779, 45–54. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2014.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthnag G. S.; Mague J. T.; Balakrishna M. S. A Cyclodiphosphazane Based Pincer Ligand, [2,6-{μ-(tBuN)2P(tBuHN)PO}2C6H3I]: NiII, PdII, PtII and CuI Complexes and Catalytic Studies. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3785–3793. 10.1039/c4dt02810d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishna M. S. Cyclodiphosphazanes in Metal Organic Frameworks. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2016, 191, 567–571. 10.1080/10426507.2015.1128906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otang M. E.; Josephson D.; Duppong T.; Stahl L. The Chameleonic Reactivity of Dilithio Bis(Alkylamido)Cyclodiphosph(III)azanes with Chlorophosphines. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 11625–11635. 10.1039/c8dt02087f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otang M. E.; Lief G. R.; Stahl L. Alkoxido-, Amido-, and Chlorido Derivatives of Zirconium- and Hafnium Bis(Amido)Cyclodiphosph(V)Azanes: Ligand Ambidenticity and Catalytic Productivity. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 820, 98–110. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2016.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lief G. R.; Moser D. F.; Stahl L.; Staples R. J. Syntheses and Crystal Structures of Mono- and Bi-Metallic Zinc Compounds of Symmetrically- and Asymmetrically-Substituted Bis(Amino)Cyclodiphosph(V)Azanes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 689, 1110–1121. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2004.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grocholl L.; Stahl L.; Staples R. J. Syntheses and Single-Crystal X-Ray Structures of [(ButNP)2(ButN)2]MCl2 (M = Zr, Hf): The First Transition-Metal Bis (Alkylamido) Cyclodiphosphazane Complexes. Chem. Commun. 1997, 1465–1466. 10.1039/a702606d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh D.; Balakrishna M. S.; Rathinasamy K.; Panda D.; Mobin S. M. Water-Soluble Cyclodiphosphazanes: Synthesis, Gold(I) Metal Complexes and Their in Vitro Antitumor Studies. Dalton Trans. 2008, 21, 2812–2814. 10.1039/b804026p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh D.; Balakrishna M. S.; Mague J. T. Novel Octanuclear Copper(i) Metallomacrocycles and Their Transformation into Hexanuclear 2-Dimensional Grids of Copper(i) Coordination Polymers Containing Cyclodiphosphazanes, [($\mu$-NtBuP)2(NC4H8X)2] (X = NMe, O). Dalton Trans. 2008, 3272–3274. 10.1039/b804311f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid A.; Ananthnag G. S.; Naik S.; Mague J. T.; Panda D.; Balakrishna M. S. Dinuclear Cu(I) Complexes of Pyridyl-Diazadiphosphetidines and Aminobis(Phosphonite) Ligands: Synthesis, Structural Studies and Antiproliferative Activity towards Human Cervical, Colon Carcinoma and Breast Cancer Cells. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 11339–11351. 10.1039/c4dt00832d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D.; Ng Z. X.; Sim Y.; Ganguly R.; García F. Cis-Cyclodiphosph(v/v)Azanes as Highly Stable and Robust Main Group Supramolecular Building Blocks. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 5998–6004. 10.1039/c8ce00395e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plajer A. J.; Zhu J.; Pröhm P.; Rizzuto F. J.; Keyser U. F.; Wright D. S. Conformational Control in Main Group Phosphazane Anion Receptors and Transporters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1029–1037. 10.1021/jacs.9b11347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plajer A. J.; Zhu J.; Proehm P.; Bond A. D.; Keyser U. F.; Wright D. S. Tailoring the Binding Properties of Phosphazane Anion Receptors and Transporters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8807–8815. 10.1021/jacs.9b00504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plajer A. J.; Rizzuto F. J.; Niu H. C.; Lee S.; Goodman J. M.; Wright D. S. Guest Binding via N–H···π Bonding and Kinetic Entrapment by an Inorganic Macrocycle. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10655–10659. 10.1002/anie.201905771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klare H.; Neudörfl J. M.; Goldfuss B. New Hydrogen-Bonding Organocatalysts: Chiral Cyclophosphazanes and Phosphorus Amides as Catalysts for Asymmetric Michael Additions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 224–236. 10.3762/bjoc.10.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klare H.; Hanft S.; Neudörfl J. M.; Schlörer N. E.; Griesbeck A.; Goldfuss B. Anion Recognition with Hydrogen-Bonding Cyclodiphosphazanes. Chemistry 2014, 20, 11847–11855. 10.1002/chem.201403013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf F. F.; Neudörfl J. M.; Goldfuss B. Hydrogen-Bonding Cyclodiphosphazanes: Superior Effects of 3,5-(CF3)2-Substitution in Anion-Recognition and Counter-Ion Catalysis. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 4854–4870. 10.1039/c7nj04660j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E. R.; Leigh D. A. Molecular Machines. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005, 133–177. 10.1007/128_011.22160338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans N. H. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Hydrogen Bond Templated Rotaxanes and Catenanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 3320–3343. 10.1002/ejoc.201900081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bo G. D.; Dolphijn G.; McTernan C. T.; Leigh D. A. [2]Rotaxane Formation by Transition State Stabilization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8455–8457. 10.1021/jacs.7b05640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panman M. R.; Bakker B. H.; den Uyl D.; Kay E. R.; Leigh D. A.; Buma W. J.; Brouwer A. M.; Geenevasen J. A. J.; Woutersen S. Water Lubricates Hydrogen-Bonded Molecular Machines. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 929–934. 10.1038/nchem.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen T.; Panman M. R.; Bakker B. H.; Hilbers M.; Woutersen S.; Brouwer A. M. Accelerating the Shuttling in Hydrogen-Bonded Rotaxanes: Active Role of the Axle and the End Station. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19118–19129. 10.1021/jacs.9b10005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagorny P.; Sun Z. New Approaches to Organocatalysis Based on C–H and C–X Bonding for Electrophilic Substrate Activation. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2834–2848. 10.3762/bjoc.12.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. S.; Jacobsen E. N. Asymmetric Catalysis by Chiral Hydrogen-Bond Donors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1520–1543. 10.1002/anie.200503132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale P. A.; Caltagirone C. Anion Sensing by Small Molecules and Molecular Ensembles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4212–4227. 10.1039/c4cs00179f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Howe E. N. W.; Gale P. A. Supramolecular Transmembrane Anion Transport: New Assays and Insights. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1870–1879. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V.; Bergamaschi G.; Boiocchi M.; Fabbrizzi L.; Milani M. The Squaramide versus Urea Contest for Anion Recognition. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 4368–4380. 10.1002/chem.200903190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti L. A.; Kumawat L. K.; Mao N.; Stephens J. C.; Elmes R. B. P. The Versatility of Squaramides: From Supramolecular Chemistry to Chemical Biology. Chem 2019, 5, 1398–1485. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V.; Fabbrizzi L.; Mosca L. Anion Recognition by Hydrogen Bonding: Urea-Based Receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3889–3915. 10.1039/b822552b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storer R. I.; Aciro C.; Jones L. H. Squaramides: Physical Properties, Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2330–2346. 10.1039/c0cs00200c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo G. D.; Gall M. A. Y.; Kuschel S.; Winter J. D.; Gerbaux P.; Leigh D. A. An Artificial Molecular Machine That Builds an Asymmetric Catalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 381–385. 10.1038/s41565-018-0105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Z. X.; Tan D.; Teo W. L.; León F.; Shi X.; Sim Y.; Li Y.; Ganguly R.; Zhao Y.; Mohamed S.; García F. Mechanosynthesis of Higher-Order Cocrystals: Tuning Order, Functionality and Size in Cocrystal Design. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 17481–17490. 10.1002/anie.202101248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock J. R.; Caltagirone C.; Light M. E.; Hursthouse M. B.; Gale P. A. Fluorescent Carbazolylurea Anion Receptors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 1781–1783. 10.1039/b900178f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy C. R.; Gale P. A.; Loeb S. J. Metal–Organic Anion Receptors Arranging Urea Hydrogen-Bond Donors to Encapsulate Sulfate Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5030–5031. 10.1021/ja039712q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y.; Miyabe H.; Takemoto Y. Catalytic Enantioselective Petasis-Type Reaction of Quinolines Catalyzed by a Newly Designed Thiourea Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 6686–6687. 10.1021/ja071470x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V.; Boiocchi M.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Fabbrizzi L.; Monzani E. Chiral Receptors for Phosphate Ions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 2632–2639. 10.1039/b504931h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. J.; Gale P. A.; Light M. E. Carboxylate Complexation by 1,1′-(1,2-Phenylene)Bis(3-Phenylurea) in Solution and the Solid State. Chem. Commun. 2005, 4696–4698. 10.1039/b508144k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. J.; Edwards P. R.; Gale P. A.; Light M. E. Carboxylate Complexation by a Family of Easy-to-Make Ortho-Phenylenediamine Based Bis-Ureas: Studies in Solution and the Solid State. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 65–70. 10.1039/b511963d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C. N.; Berryman O. B.; Johnson C. A.; Zakharov L. N.; Haley M. M.; Johnson D. W. Protonation Activates Anion Binding and Alters Binding Selectivity in New Inherently Fluorescent 2,6-Bis(2-Anilinoethynyl)Pyridine Bisureas. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2520–2522. 10.1039/b901643k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C.; Wu B.; Li S.; Huang X.; Yang X.-J. Tetraureas versus Triureas in Sulfate Binding. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5612–5615. 10.1021/ol102221x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C.; Wu B.; Li S.; Yang Z.; Zhao Q.; Liang J.; Li Q.-S.; Yang X.-J. A Fully Complementary, High-Affinity Receptor for Phosphate and Sulfate Based on an Acyclic Tris(Urea) Scaffold. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 5376–5378. 10.1039/c0cc00937g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta C.; Talotta C.; Sala P. D.; Margarucci L.; Casapullo A.; Neri P. Anion-Induced Dimerization in p-Squaramidocalix[4]Arene Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 3704–3708. 10.1021/jo500422u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keat R.; Thompson D. G. Some Oxidation Reactions of Aminocyclodiphosph(III)Azanes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1980, 928–936. 10.1039/dt9800000928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lief G. R.; Carrow C. J.; Stahl L.; Staples R. J. Trispirocyclic Bis(Dimethylaluminum)Bis(Amido)Cyclodiphosph(V)azanes. Organometallics 2001, 20, 1629–1635. 10.1021/om000916e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T. G.; Haltiwanger R. C.; Thompson M. L.; Katz S. A.; Norman A. D. Cis/Trans Isomerization and Conformational Properties of 2,4-Bis(Primary Amino)-1,3,2,4-Diazadiphosphetidines. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 1770–1777. 10.1021/ic00087a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran P.; Mague J. T.; Balakrishna M. S. Synthesis and Derivatization of the Bis(Amido)-λ3-cyclodiphosphazanes Cis-[R′(H)NP(Μ-NR)]2, Including a Rare Example, trans-[tBu(H)N(Se)P(Μ-NCy)]2, Showing Intermolecular Se···H–O Hydrogen Bonding. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 2264–2272. 10.1002/ejic.201001348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moser D. F.; Carrow C. J.; Stahl L.; Staples R. J. Titanium Complexes of Bis(1-Amido)Cyclodiphosph(III)azanes and Bis(1-Amido)Cyclodiphosph(V)azanes: Facial versus Lateral Coordination. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001, 1246–1252. 10.1039/b007877h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers T.; Krahn M.; Parvez M.; Schatte G. Preparation and X-Ray Structures of Alkali-Metal Derivatives of the Ambidentate Anions [tBuN(E)P(μ-NtBu)2P(E)NtBu]2– (E = S, Se) and [tBuN(Se)P(μ-NtBu)2PN(H)tBu)]−. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 2547–2553. 10.1021/ic001093o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashall A.; Doyle E. L.; García F.; Lawson G. T.; Linton D. J.; Moncrieff D.; McPartlin M.; Woods A. D.; Wright D. S. Suggestion of a “Twist” Mechanism in the Oligomerisation of a Dimeric Phospha(III)Zane: Insights into the Selection of Adamantoid and Macrocyclic Alternatives. Chemistry 2002, 8, 5723–5731. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García F.; Kowenicki R. A.; Kuzu I.; Riera L.; McPartlin M.; Wright D. S. The Formation of Dimeric Phosph(III)azane Macrocycles [{P(μ-NtBu)}2·LL]2 [LL = Organic Spacer]. Dalton Trans. 2004, 7, 2904–2909. 10.1039/b409071c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García F.; Kowenicki R. A.; Kuzu I.; McPartlin M.; Riera L.; Wright D. S. The First Complex of the Pentameric Phosphazane Macrocycle [P(NtBu)\2(NH)]5 with a Neutral Molecular Guest: Synthesis and Structure of [{P(μ-NtBu)}2(NH)]5(CH2Cl2)2. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2005, 8, 1060–1062. 10.1016/j.inoche.2005.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Leon F.; Sim Y.; Quek S.; Hum G.; Khoo Y. X. J.; Ng Z. X.; Yang P. M.; Ong H. C.; Singh V. K.; Ganguly R.; Clegg J. K.; Diaz J.; Garcia F. N-bridged Acyclic Trimeric Poly-Cyclodiphosphazanes: Highly Tuneable Building Blocks within the Cyclodiphosphazane Family. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 22100–22108. 10.1002/anie.202008214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam V.; Domaradzki M. E.; Jang S.; Muthyala R. S. Carbonyl Groups as Molecular Valves to Regulate Chloride Binding to Squaramides. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3315–3318. 10.1021/ol801204s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri C. G.; Ulmann P. A.; Wiester M. J.; Mirkin C. A. Heteroligated Supramolecular Coordination Complexes Formed via the Halide-Induced Ligand Rearrangement Reaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1618–1629. 10.1021/ar800025w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri C. G.; Nguyen S. T.; Mirkin C. A. A Highly Modular and Convergent Approach for the Synthesis of Stimulant-Responsive Heteroligated Cofacial Porphyrin Tweezer Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 2755–2763. 10.1021/ic702150y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beswick M. A.; Elvidge B. R.; Feeder N.; Kidd S. J.; Wright D. S. [tBuNHP(μ-NtBu)PNH2], a Novel Building Block for Neutral and Anionic Polycyclic Main Group Arrangements. Chem. Commun. 2001, 4, 379–380. 10.1039/b009000j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. X.; Liang R. Z.; Martin K. A.; Weston N.; Calera S. G.; Ganguly R.; Li Y.; Lu Y.; Ribeiro A. J. M.; Ramos M. J.; Fernandes P. A.; García F. Synthesis and Hydrolytic Studies on the Air-Stable [(4-CN-PhO)(E)P(μ-NtBu)]2 (E = O, S, and Se) Cyclodiphosphazanes. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 6423–6432. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim Y.; Tan D.; Ganguly R.; Li Y.; García F. Orthogonality in Main Group Compounds: Direct One-Step Synthesis of Air- and Moisture-Stable Cyclophosphazanes by Mechanochemistry. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6800–6803. 10.1039/c8cc01043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. X.; Martin K. A.; Liang R. Z.; Star D. G.; Li Y.; Ganguly R.; Sim Y.; Tan D.; Díaz J.; García F. Synthesis of Unique Phosphazane Macrocycles via Steric Activation of C-N Bonds. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 10993–11004. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. X.; Liang R. Z.; Martin K. A.; Star D. G.; Díaz J.; Li X. Y.; Ganguly R.; García F. Steric C–N Bond Activation on the Dimeric Macrocycle [{P(μ-NR)}2(μ-NR)]2. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 16468–16471. 10.1039/c5cc06034f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looney A.; Parkin G.; Rheingold A. L. Anion Coordination by Protonated Tris(Pyrazolyl)Hydroborato Derivatives: Crystal Structure of the Host-Guest Complex [{η3-HB(3-Tert-Bu-PzH)3}Cl]·[AlCl4]. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 3099–3101. 10.1021/ic00015a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veith M.; Walgenbach A.; Huch V.; Kohlmann H. Aluminum/Nitrogen Cycles and an Open Cage with Al–H and N–H Functions. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2017, 643, 1233–1239. 10.1002/zaac.201700278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bashall A.; Bond A. D.; Doyle E. L.; García F.; Kidd S.; Lawson G. T.; Parry M. C.; McPartlin M.; Woods A. D.; Wright D. S. Templating and Selection in the Formation of Macrocycles Containing [{P(Μ-NtBu)2}(Μ-NH)]n Frameworks: Observation of Halide Ion Coordination. Chemistry 2002, 8, 3377–3385. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim Y.; Leon F.; Hum G.; Phang S. J. I.; Ong H. C.; Ganguly R.; Díaz J.; Clegg J. K.; García F. Pre-Arranged Building Block Approach for the Orthogonal Synthesis of an Unfolded Tetrameric Organic–Inorganic Phosphazane Macrocycle. Commun. Chem. 2022, 5, 59. 10.1038/s42004-022-00673-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; León F.; Ong H. C.; Ganguly R.; Díaz J.; García F. Size-Control in the Synthesis of Oxo-Bridged Phosphazane Macrocycles via a Modular Addition Approach. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 21. 10.1038/s42004-021-00455-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García F.; Goodman J. M.; Kowenicki R. A.; Kuzu I.; McPartlin M.; Silva M. A.; Riera L.; Woods A. D.; Wright D. S. Selection of a Pentameric Host in the Host–Guest Complexes {[{[P(μ-NtBu)]2(μ-NH)}5]·I}–[Li(Thf)4]+ and [{[P(μ-NtBu)]2(μ-NH)}5]·HBr·THF. Chemistry 2004, 10, 6066–6072. 10.1002/chem.200400320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordarson P. Determining Association Constants from Titration Experiments in Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1305–1323. 10.1039/c0cs00062k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert D. B.; Thordarson P. The Death of the Job Plot, Transparency, Open Science and Online Tools, Uncertainty Estimation Methods and Other Developments in Supramolecular Chemistry Data Analysis. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12792–12805. 10.1039/c6cc03888c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.