Short abstract

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs contracts with private-sector providers to help ensure that eligible veterans receive timely health care. This care can alleviate access barriers for veterans, but questions remain about its cost and quality.

Keywords: Military Veterans, Veterans Health Care

Abstract

Despite an overall decline in the U.S. veteran population, the number of veterans using VA health care has increased. To deliver timely care to as many eligible veterans as possible, VA supplements the care delivered by VA providers with private-sector community care, which is paid for by VA and delivered by non-VA providers. Although community care is a potentially important resource for veterans facing access barriers and long wait times for appointments, questions remain about its cost and quality. With recent expansions in veterans’ eligibility for community care, accurate data are critical to policy and budget decisions and ensuring that veterans receive the high-quality health care they need.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the part of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) that provides health care to eligible veterans. VHA is an integrated health care system that includes 171 medical centers and 1,113 outpatient sites (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022e). In 2021, more than 9.2 million veterans (roughly half of all living U.S. veterans) were enrolled in VHA, and around 6.8 million received care through VHA (Congressional Budget Office, 2021; Schaeffer, 2021; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022d). On average, VHA's estimated spending was $14,750 per veteran patient in 2021 (Congressional Budget Office, 2021), which is similar to Medicare ($14,348 per beneficiary in 2020) (Boards of Trustees, 2021).

Veterans who use VA health care (VHA patients) are a clinically complex group with a higher prevalence of serious health conditions than both nonveterans and veterans who do not use VA health care (Eibner et al., 2015). In part, this is a result of the eligibility criteria for VA health care benefits. Not all veterans are eligible; in general, eligibility is based on length of military service, having a health condition related to military service, and income. Eligible veterans are sorted into VHA enrollment priority groups, which determine whether and how much veterans must contribute financially to their care (see sidebar). Among veterans, VHA patients are more likely to have service-related injuries and chronic health problems, including traumatic brain injury, cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Eibner et al., 2015).

Factors Determining Veterans’ Eligibility and Priority for VHA Benefits

Veterans must first meet basic criteria to be eligible for VHA benefits.

When military service began

Duration of military service or active-duty service (for reserve and National Guard members)

Conditions of discharge from the military

Service-related conditions (e.g., disability, military sexual trauma)

Eligible veterans are assigned to 1 of 8 priority groups.

Determines when a veteran is eligible for benefits and to what extent they contribute to the cost of their care

-

Factors considered:

Military service history

Disability rating

Income level

Eligibility for Medicaid

Other benefits received (e.g., VA pension benefits)

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022c.

The VHA patient population is changing, however. Since 1980, eligibility for VA health care has expanded to cover more veterans, and although the overall veteran population has declined since that time, the number of veterans using VHA has increased. Prior RAND research estimated that, between 2014 and 2024, the number of U.S. veterans would decrease by 19 percent and their average age would increase, barring any major policy changes or large-scale conflicts (Eibner et al., 2015). There has also been a geographic shift in the veteran population, with more veterans living in the southern and western parts of the United States, a trend that is projected to continue and that mirrors trends in the U.S. population as a whole (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022a; Kerns and Locklear, 2019).

VHA patients rely on VHA the most for prescription drug benefits and inpatient visits following surgeries. Lower-income veterans, veterans without health care coverage from other sources, veterans with worse self-reported health, and rural veterans receive a higher-than-average proportion of their care from VHA (Eibner et al., 2015).

The Use of Community Care to Supplement VHA Care for Veterans

In 2014, following widespread media coverage of long wait times at VHA facilities, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, also known as the Veterans Choice Act (Pub. L. 113-146, 2014). The Veterans Choice Program was an integral part of the Veterans Choice Act. It broadened the eligibility criteria for veterans who wanted or needed to access community care—care paid for by VHA but delivered by non-VHA providers. VA's Office of Community Care was established in 2015 to oversee the expansion of community care under the Veterans Choice Program. In 2018, the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act was signed into law (Pub. L. 115-182, 2018). This legislation further expanded eligibility for community care and created a more permanent and consolidated community care program, known as the Veterans Community Care Program.

In 2015, RAND researchers conducted a series of assessments mandated by the Veterans Choice Act that involved identifying veteran demographics and health care needs, forecasting changes to the VHA patient population, analyzing VA health care capabilities, and measuring the quality of care provided by VHA compared with the private sector (Farmer, Hosek, and Adamson, 2016). RAND work has also highlighted some of the challenges that veterans may face in accessing VHA care directly, particularly as a result of geographic and transportation barriers. Although RAND researchers found that 93 percent of veterans lived within 40 miles’ driving distance of a VHA facility as of 2015, only 55 percent were that close to a VHA medical center, which provides a more comprehensive array of services than other VHA facilities, and only 26 percent were within 40 miles of a VHA medical center with full specialty care (Hussey et al., 2015). RAND research found that most veterans received timely care (more than 90 percent had completed visits within 30 days of their preferred date for care, with the vast majority of these visits occurring within 14 days). However, the same analysis also found variations in timeliness across VHA facilities, with some veterans experiencing much longer than average wait times for care (Hussey et al., 2015). For veterans with limited access to a VHA facility or who are unable to access timely care, community care providers are a potentially important resource.

Community care has been a component of the health care provided to U.S. veterans since World War I, but its use significantly increased under the Veterans Choice and VA MISSION Acts. The laws expanded eligibility for community care such that every veteran enrolled in VA health care could qualify under certain circumstances (Congressional Budget Office, 2021). Veterans must meet one of the following eligibility criteria to access VHA-funded community care (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019):

VHA facilities do not offer the services that the veteran needs.

The veteran resides in a state or territory without a full-service VHA medical facility.

The veteran was eligible under provisions that applied before the VA MISSION Act was signed (i.e., they qualify under “grandfathered” eligibility for community care).

The care or services that the veteran needs do not meet the access standards for appointment wait times or drive times.

A VHA provider and the veteran agree that receiving care from an outside provider is in the veteran's best interest.

The care or services that the veteran needs do not meet designated quality standards.

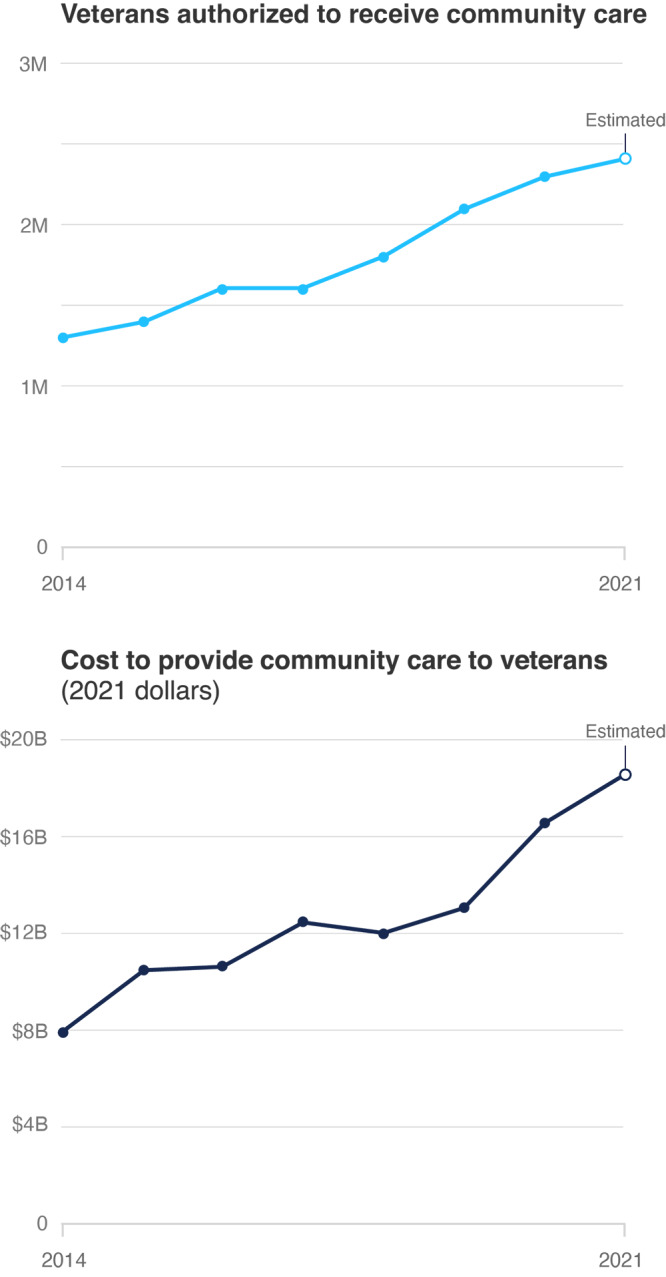

Since 2014, the number of veterans receiving community care has grown considerably, along with VA's budget for community care. In July 2022 testimony to the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, VA reported that community care accounted for 44 percent of its health care services across care settings (LaPuz, 2022).1 Figure 1 shows the number of veterans authorized for community care and the costs of community care over the period from 2014 to 2021. The total amount that VA has spent on community care has steadily increased, from $7.9 billion in 2014 to $18.5 billion in 2021 (Congressional Budget Office, 2021; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022b). As the costs for community care have risen, the share of the VHA budget that goes toward community care has also increased. In 2014, community care accounted for approximately 12 percent of VHA spending. However, this proportion had nearly doubled by 2021, with community care costs making up 20 percent of all VHA spending on medical care (Congressional Budget Office, 2021). VA's fiscal year 2023 budget request anticipated that community care would increase to 23 percent of the VHA medical care budget in 2023 and 25 percent in 2024 (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022b).

Figure 1.

Number of Veterans Eligible for VHA Funded Community Care Over Time and the Cost of Providing That Care

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office, 2021, p. 7, Table 1. Estimated number of veterans authorized to receive community care in 2021 extrapolated from LaPuz, 2022. Estimated costs to provide community care in 2021 are from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022b.

NOTE: The Congressional Budget Office's definition of community care includes inpatient, outpatient, dental, mental health, prosthetics, and rehabilitation services from non-VHA providers, as well as long-term support, such as through nursing homes, noninstitutional care, and state facilities and programs. Those data do not reflect certain other services supported through community care funding, such as those for caregivers and Camp Lejeune Family Member Program participants.

Pressing Issues

The Veterans Choice and VA MISSION Acts placed a priority on giving veterans more flexibility in accessing care outside of VHA facilities. Although research has shown that VHA provides care that is equivalent to or higher in quality than what veterans receive from non-VHA providers (Price et al., 2018), worries about wait times and rural veterans’ access to care have tarnished VHA's reputation in some circles (Chan, Card, and Taylor, 2022; Jones et al., 2021).

Achieving the promises of community care requires coordination between VHA and non-VHA facilities and providers. As more data become available on veterans’ health care use following the passage of the Veterans Choice and VA MISSION Acts, evaluations of community care must address several key questions that will be critical to policy and budget decisions ensuring that veterans have access to the health care they need.

The cost and quality of community care relative to VHA-delivered care are largely unknown.

As part of its annual budget request to Congress, VA projects demand for health care among VHA enrollees, which determines how much funding it requests for the delivery of that care. In general, these estimates are based on the cost of VHA-delivered care. However, little is known about how the costs of care provided directly by VHA compare with the costs of community care. If costs for community care are significantly higher than for VHA-delivered care and the number of veterans receiving community care continues to increase, VA might need to implement cost controls, possibly by decreasing access to community care, increasing cost-sharing for certain veterans, or restricting VHA enrollment (Kime, 2022).

Although comparisons between the cost of VHA-delivered and community care are limited, there are some indications that community care may be more expensive than VHA-delivered care. VHA has the ability to manage and standardize the care that it delivers directly, but it is not able to manage veterans’ care once they have been referred to community providers. VHA officials have reported that local community care practice patterns, such as a greater use of X-rays and other imaging services, were a driver of higher-than-estimated spending on community care in 2017 and 2018 (Congressional Budget Office, 2021). A recent analysis noted that VHA-delivered care costs less than comparable care from Medicare providers and produced better outcomes (Chan, Card, and Taylor, 2022).

Quality comparisons between care that veterans receive through the VA Community Care Network and care that they receive directly from VHA providers are also limited. A recent analysis by VA researchers found that, nationally, veterans who received total knee arthroplasties at a VHA facility had lower odds of readmission than those whose surgery had been performed by a community care provider (Rosen et al., 2022). Another analysis of complications following cataract surgery found no significant differences between VHA-provided care and community care (Rosen et al., 2020). Tracking the quality of care provided through the Community Care Network is necessary to identify whether and how the increased reliance on community care has affected veterans’ outcomes. Community care puts VHA into the role of a payer for health care as opposed to its traditional role as an integrated health system, in which it functions as both provider and payer. As a payer, VHA can hold third-party administrators responsible for implementing and managing the Community Care Network and accountable for the quality and adequacy of community care providers. To do this, VHA needs to set quality standards and performance metrics and either require providers to report on their ability to meet those expectations or conduct its own evaluations.

VHA faces challenges with care coordination as more veterans receive care in the community.

VHA is an integrated health system, and care coordination is an essential element of its ability to serve patients. VHA was an early adopter of electronic health records, which it has used alongside other resources to manage the health of its patient population, such as care coordination teams that support veterans with complex symptoms or multiple health conditions (Cordasco et al., 2019; Garvin et al., 2021; Miller et al., 2021). The complexity of the VHA patient population makes care coordination critical for improving patient outcomes and decreasing costs. With the increased use of community care, VHA faces an additional coordination challenge: sharing and obtaining information from non-VHA providers. Poorly coordinated care between VHA and community care providers could result in confusion for patients, duplicative tests, increased costs, and lower-quality care. Research also suggests that the increased burden of coordinating care with non-VHA providers has resulted in higher rates of burnout among VHA primary care providers (Apaydin et al., 2021). To address these challenges, VA created the Office of Integrated Veteran Care in October 2021, with a focus on improving coordination across care settings (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2021). Because this integrated care model is still being implemented and has not yet been established nationwide, it is not known whether and to what extent it will address care coordination challenges and improve care for veterans.

Data are limited, but access to community care may be no better than access to care at VHA facilities.

One of the driving forces behind the Veterans Choice and the MISSION Acts was a concern about veterans facing long wait times for VHA appointments. Although community care promised to reduce wait times and facilitate access to care, in practice, veterans have not always experienced shorter wait times for appointments. Before making an appointment, veterans must receive approval and a referral to community care from VHA. Once a veteran is deemed eligible for this treatment, VHA officials have no control over the wait time to see a community care provider (Congressional Budget Office, 2021; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2020). As the Congressional Budget Office has noted, community care providers are not required to meet the wait- and drive-time standards that apply to VHA facilities. The COVID-19 pandemic may have further exacerbated delays for veterans seeking community care by slowing down VHA's approval process and by prompting community care providers to limit the availability of appointments (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2021).

One analysis of wait times for outpatient specialty care at VHA and community care facilities found that mean wait times decreased between 2015 and 2018 for both, with the greatest declines at VHA facilities. The study period aligned with the expansion of eligibility for community care among VHA-enrolled veterans under the Veterans Choice and VA MISSION Acts. By 2018, community care wait times were longer than VHA wait times (Gurewich et al., 2021). Other studies have similarly found that the timeliness of community care was no better or worse than VHA, suggesting that community care is unlikely to completely address the challenges that some veterans face in receiving timely care (Kaul et al., 2021; Dueker and Khalid, 2020).

However, there may be certain populations of veterans for whom community care has significantly improved access. Prior research has found that rural veterans, who make up nearly half of VHA patients, are more likely to live in areas with provider shortages and hospital closures, and they generally have to drive greater distances to see providers (Hussey et al., 2015; Ohl et al., 2018). Community care may improve access for veterans who live far from a VHA facility, which could help reduce disparities in access between urban and rural veterans (Davila et al., 2021); however, research on this topic has been limited.

Community care providers might not be equipped to meet the needs of veterans.

Veterans enrolled in VHA are a complex patient population with health care needs that differ from those of the nonveteran population, including higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder, exposure to environmental toxins, and suicide (Farmer et al., 2016). VHA providers are well-versed in veteran culture and the conditions that are prevalent among veterans. Community care providers may not have substantial experience caring for veterans and may not even realize that a given patient is a veteran (Tanielian et al., 2014). Lack of knowledge and understanding about veterans’ unique experiences and health care needs is especially a concern for veterans who may be at risk for certain kinds of cancers as a result of their military service (White House, 2022), veterans who have experienced military sexual trauma, gender and sexual minority veterans, and other veterans who require specialized care.

VHA makes training available to community care providers to help increase their military/veteran cultural competency, familiarity with health care issues that are common among veterans, and aspects of specialized care. However, only a small proportion of community care providers have completed this training (Farmer et al., 2022), and VHA has no authority to require that they do so. Future evaluations of veterans’ care should explore links between community care providers’ familiarity with treating veterans and whether veteran patients’ full set of needs are being met, regardless of where they receive care.

Directions for Future Research

The landscape of veterans’ health care has changed with the passage of the Veterans Choice and VA MISSION Acts. Although the laws have the potential to improve access to care for some veterans, they have also introduced additional challenges to tracking and evaluating the timeliness, quality, and coordination of care that veterans receive. There are several potential directions for future research in this area:

Model community care access and utilization. Existing data on demand for and utilization of community care could be used to assess historical trends (e.g., use of community care by veterans’ demographic and geographic characteristics, types of care veterans receive from community care providers). These data could also be used to model future community care demand patterns, which would help VHA better prepare for the volume of care that patients could require, improve the accuracy of budget estimates, and allow for policy simulations to estimate the effect of potential policy changes, such as reforms to access standards.

Examine differences in health care quality and access between VHA-delivered and community care. Policymakers must ensure that standards for community care are at least equal to those for VHA-delivered care. Veterans who see community care providers should be able to expect the same high quality of care that they receive from VHA providers. Researchers at VA and other organizations should work to establish methods to better compare care quality and wait times between VHA facilities and community care providers. Evaluating whether veterans receive equivalent standards of care also requires the creation and implementation of consistent quality measures that are comparable between VHA and community care providers.

Study differences in veterans’ experiences with community care. It is essential that researchers examine potential disparities in care outcomes and experiences across veteran populations, such as by gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity, geography, and VHA priority group. Such analyses should look for disparities both across VHA facilities and community care providers and between these two sources of care.

Ask about community care providers’ experiences in delivering care to veterans. The perspectives of community care providers can help draw a more complete picture of the benefits and drawbacks of community care. Their perceptions of their readiness to treat veterans and the challenges they experience when working with VHA could also help inform policies and programs to improve care coordination and outreach efforts to increase community care providers’ familiarity with veterans and their needs.

As Secretary of Veterans Affairs Denis McDonough recently stated, the future of VHA depends on its ability to attract veterans to its facilities and—through high-quality, accessible services—keep those veterans returning to VHA for their needed medical care (McDonough and Steinhauer, 2022). Coordinating with community care providers and ensuring that eligible veterans can access the high-quality care they need in a timely fashion, whether at VHA facilities or in the community, will be integral to achieving those goals.

Additional Resources

-

VA provides comprehensive information (https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/programs/veterans/index.asp) about community care for veterans, including

eligibility criteria

how to find community providers and make appointments

costs and billing

the Community Care Network (https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/programs/veterans/CCN-Veterans.asp) of providers, which is divided into five regions.

VA's Community Care Research Evaluation and Knowledge (CREEK) Center (https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/centers/creek/) serves as a health care policy and data expertise hub.

-

The two contractors for the VA Community Care Network, TriWest and Optum Serve, provide information for veterans about receiving care from the network:

TriWest (https://www.triwest.com/en/veteran-services/) serves veterans living in the western part of the United States.

Optum Serve (https://www.vacommunitycare.com/) serves veterans living in the eastern and southern parts of the United States.

In October 2021, the Congressional Budget Office released an analysis of the Veterans Community Care Program that provides background on the program and evidence of its early effects (https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57583).

A June 2021 special supplement of the journal Medical Care included 12 articles on VHA community care (https://journals.lww.com/lww-medicalcare/toc/2021/06001).

Notes

This does not include care that is available only through VHA facilities or only from community care providers (e.g., obstetrics, in the latter case). VA estimates that 73 percent of all health care services are available in both VHA facilities and community care settings (LaPuz, 2022).

Funding for this publication was made possible by a generous gift from Daniel J. Epstein through the Epstein Family Foundation, which established the RAND Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute in 2021. The institute is dedicated to conducting innovative, evidence-based research and analysis to improve the lives of those who have served in the U.S. military. Building on decades of interdisciplinary expertise at the RAND Corporation, the institute prioritizes creative, equitable, and inclusive solutions and interventions that meet the needs of diverse veteran populations while engaging and empowering those who support them. For more information about the RAND Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute, visit veterans.rand.org.

References

- Apaydin Eric A., Rose Danielle E., McClean Michael R., Yano Elizabeth M., Shekelle Paul G., Nelson Karin M., and Stockdale Susan E. Association Between Care Coordination Tasks with Non-VA Community Care and VA PCP Burnout: An Analysis of a National, Cross-Sectional Survey BMC Health Services Research 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06769-7. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , article 809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds 2021 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. August 31, 2021. , , Washington, D.C., .

- Chan David C., Jr., Card David, and Taylor Lowell . Is There a VA Advantage? Evidence from Dually Eligible Veterans. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research; February 2022. , , : , Working Paper Series, No. 29765, . [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office The Veterans Community Care Program: Background and Early Effects. October 2021. , , Washington, D.C., .

- Cordasco Kristina M., Hynes Denise M., Mattocks Kristin M., Bastian Lori A., Bosworth Hayden B., and Atkins David Improving Care Coordination for Veterans Within VA and Across Healthcare Systems Journal of General Internal Medicine May 2019;34(1, Suppl. 1):1. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04999-4. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila Heather, Rosen Amy K., Beilstein-Wedel Erin, Shwartz Michael, Chatelain Leslie, Jr., and Gurewich Deborah Rural Veterans’ Experiences with Outpatient Care in the Veterans Health Administration Versus Community Care Medical Care June 2021;59(6, Suppl. 3):S286. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001552. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueker Jeffrey M., and Khalid Asif Performance of the Veterans Choice Program for Improving Access to Colonoscopy at a Tertiary VA Facility Federal Practitioner May 2020;37(5):224. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibner Christine, Krull Heather, Brown Kristine M., Cefalu Matthew, Mulcahy Andrew W., Pollard Michael S., Shetty Kanaka, Adamson David M., Armaral Ernesto F. L., Armour Philip, et al . Current and Projected Characteristics and Unique Health Care Needs of the Patient Population Served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1165z1.html ., , : , RR-1165/1-VA, . As of August 2022: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Carrie M., Hosek Susan D., and Adamson David M. Balancing Demand and Supply for Veterans’ Health Care: A Summary of Three RAND Assessments Conducted Under the Veterans Choice Act. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2016. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1165z4.html , , : , RR-1165/4-RC, . As of August 2022: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Carrie M., Smucker Sierra, Ernecoff Natalie, and Al-Ibrahim Hamad . Recommended Standards for Delivering High-Quality Care to Veterans with Invisible Wounds. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1728-1.html , , : , RR-A1728-1, . As of August 2022: [Google Scholar]

- Garvin Lynn A., Pugatch Marianne, Gurewich Deborah, Pendergast Jacquelyn N., and Miller Christopher J. Interorganizational Care Coordination of Rural Veterans by Veterans Affairs and Community Care Programs: A Systematic Review Medical Care June 2021;59(Suppl 3):S259. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001542. , “. ,” . , Vol. , , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurewich Deborah, Shwartz Michael, Beilstein-Wedel Erin, Davila Heather, and Rosen Amy K. Did Access to Care Improve Since Passage of the Veterans Choice Act? Differences Between Rural and Urban Veterans Medical Care June 2021;59(Suppl. 3):S270. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001490. , “. ,” . , Vol. , , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey Peter S., Ringel Jeanne S., Ahluwalia Sangeeta C., Price Rebecca Anhang, Buttorff Christine, Concannon Thomas W., Lovejoy Susan L., Martsolf Grant R., Rudin Robert S., Schultz Dana, et al . Resources and Capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to Provide Timely and Accessible Care to Veterans. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1165z2.html ., , : , RR-1165/2-VA, . As of August 2022: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Audrey L., Fine Michael J., Taber Peter A., Hausmann Leslie R. M., Burkitt Kelly H., Stone Roslyn A., and Zickmund Susan L. National Media Coverage of the Veterans Affairs Waitlist Scandal: Effects on Veterans’ Distrust of the VA Health Care System Medical Care June 2021;59(Suppl. 3):S322. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001551. , “. ,” . , Vol. , , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul Bhavika, Hynes Denise M., Hickok Alex, Smith Connor, Niederhausen Meike, Totten Annette M., Whooley Mary A., and Sarmiento Kathleen Does Community Outsourcing Improve Timeliness of Care for Veterans with Obstructive Sleep Apnea? Medical Care February 2021;59(2):111. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001472. , “. ” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns Kristin, and Locklear L. Slagan . America Counts: Stories Behind the Numbers. U.S. Census Bureau; April 29, 2019. Three New Census Bureau Products Show Domestic Migration at Regional, State, and County Levelshttps://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/04/moves-from-south-west-dominate-recent-migration-flows.html , “. ,” . , , . As of August 2022: [Google Scholar]

- Kime Patricia VA Weighs Limiting Access to Outside Doctors to Curb Rising Costs. June 15, 2022. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2022/06/15/va-weighs-limiting-access-outside-doctors-curb-rising-costs.html , “. ,” Military.com, . As of August 2022:

- LaPuz Miguel . Acting Deputy Under Secretary of Veterans Affairs for Health, statement before the U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, Subcommittee on Health; July 14, 2022. , , , . [Google Scholar]

- McDonough Denis R., and Steinhauer Jennifer . A Conversation with VA Secretary McDonough on the Department's Recommendations to the Asset and Infrastructure Review Commission. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CFA1363-1.html , , event video and transcript, : , CF-A1363-1, . As of August 2022: [Google Scholar]

- Miller Christopher, Gurewich Deborah, Garvin Lynn, Pugatch Marianne, Koppelman Elisa, Pendergast Jacquelyn, Harrington Katharine, and Clark Jack A. Veterans Affairs and Rural Community Providers’ Perspectives on Interorganizational Care Coordination: A Qualitative Analysis Journal of Rural Health Spring 2021;37(2):417. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12453. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl Michael E., Carrell Margaret, Thurman Andrew, Weg Marg Vander, Hudson Teresa, Mengeling Michelle, and Vaughan-Sarrazin Mary Availability of Healthcare Providers for Rural Veterans Eligible for Purchased Care Under the Veterans Choice Act BMC Health Services Research 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3108-8. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , article 315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price Rebecca Anhang, Sloss Elizabeth M., Cefalu Matthew, Farmer Carrie M., and Hussey Peter S. Comparing Quality of Care in Veterans Affairs and Non–Veterans Affairs Settings Journal of General Internal Medicine October 2018;33(10):1631. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4433-7. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Law 113-146 Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. August 7, 2014. , , .

- McCain John S., III, Akaka Daniel K., and Samuel R., Johnson VA. Public Law 115-182 Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act 2018. June 6, 2018. , , .

- Rosen Amy K., Beilstein-Wedel Erin E., Harris Alex H. S., Shwartz Michael, Vanneman Megan E., Wagner Todd H., and Giori Nicholas J. Comparing Postoperative Readmission Rates Between Veterans Receiving Total Knee Arthroplasty in the Veterans Health Administration Versus Community Care Medical Care February 2022;60(2):178. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001678. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen Amy K., Vanneman Megan E., O'Brien William J., Pershing Suzann, Wagner Todd H., Beilstein-Wedel Erin, Jeanie Lo, Chen Qi, Cockerham Glenn C., and Shwartz Michael Comparing Cataract Surgery Complication Rates in Veterans Receiving VA and Community Care Health Services Research October 2020;55(5):690. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13320. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer Katherine . The Changing Face of America's Veteran Population. Pew Research Center; April 5, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/05/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population , “. ,” . , . As of August 2022: [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian Terri, Farris Coreen, Batka Caroline, Farmer Carrie M., Robinson Eric, Engel Charles C., Robbins Michael W., and Jaycox Lisa H. Ready to Serve: Community-Based Provider Capacity to Deliver Culturally Competent, Quality Mental Health Care to Veterans and Their Families. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2014. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR806.html , , : , RR-806-UNHF, . As of August 2022: [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veteran Community Care Eligibility. August 30, 2019. https://www.va.gov/communitycare/docs/pubfiles/factsheets/va-fs_cc-eligibility.pdf , “. ,” factsheet, . As of August 2022:

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs VA Recommendations to the Asset and Infrastructure Review Commission, Vol. 1: Introduction, Approach and Methodology, and Outcomes. March 2022a. , , Washington, D.C., .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2023 President's Budget Request. March 28, 2022b. https://www.va.gov/budget/docs/summary/fy2023-va-budget-rollout-briefing.pdf , “. ,” briefing, Washington, D.C., . As of August 2022:

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Eligibility for VA Health Care. April 19, 2022c. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of August 2022:

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs VA Benefits and Health Care Utilization. April 21, 2022d. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/pocketcards/fy2022q3.pdf , “. ,” factsheet, . As of August 2022:

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs About VHA. August 15, 2022e. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutVHA.asp , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of August 2022:

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs VA Embarks on Process to Design New Model to Deliver Seamless Integrated Care. October 5, 2021. , “. ,” press release, .

- U.S. Government Accountability Office Veterans Community Care Program: Improvements Needed to Help Ensure Timely Access to Care. September 2020. , , Washington, D.C., GAO-20-643, .

- U.S. Government Accountability Office Veterans Community Care Program: VA Took Action on Veterans’ Access to Care, but COVID-19 Highlighted Continued Scheduling Challenges. June 2021. , , Washington, D.C., GAO-21-476, .

- White House President Biden Signs the PACT Act and Delivers on His Promise to America's Veterans. August 10, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans , “. ,” factsheet, . As of August 2022: