Abstract

Phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) have been extensively investigated in vivo and in vitro for antisense control of gene expression. It has been shown that cellular uptake of phosphorothioate ODNs in some in vitro cell systems increases in the presence of divalent cations. In this work, we analyze the conformation of phosphorothioate ODNs and specific changes induced in it by various divalent cations using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. CD data were obtained with several phosphorothioate ODNs in the absence and presence of the divalent cations Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+, Ba2+ and Mn2+. All CD spectra indicated stable conformations of the ODNs in solution. The spectra were strongly dependent on ODN sequence and composition. Some ODNs such as T23 and another with ‘random’ distribution of bases showed CD spectra characteristic of B-form DNA. Other ODNs which had at least three consecutive guanines in their sequences exhibited spectra characteristic of parallel G-tetraplexes. CD spectra of antisense ODNs exhibited specific responses to divalent cations. Changes in the conformation were not simply due to ionic strength effects. Mn2+ diminished secondary structure in some ODNs. Group II divalent ions stabilized the parallel G-tetraplexes, and Mg2+ generally had the weakest stabilizing efficiency. Each sequence/ion combination had a specific response so these effects cannot be generalized. These sequence-dependent, divalent ion-sensitive, and structurally unique solution conformations may be related to ion-mediated ODN uptake.

INTRODUCTION

Oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) have recently gained considerable attention in drug therapy because of their high target affinity and specificity (1). There are several mechanisms by which ODNs can have effects at the cellular level (2). One approach is the antisense strategy, which involves hybridization of complimentary single-stranded ODNs to mRNA transcripts and subsequent enzymatic cleavage of the mRNA (3). Alternatively, this hybridization can lead to arrested translation and formation of an incomplete or non-functioning protein molecule. Other novel approaches such as antigenes, ribozyme targeting or aptamer recognition are also being developed (4). Since intervention is at the level of protein expression, ODNs can provide better control over the etiology of a disease than conventional therapeutics which typically act less selectively on proteins. As a result, promising ODN candidates are emerging for antiviral, anticancer and anti-inflammatory use (5–7).

First generation phosphodiester ODNs were ineffective in therapeutic applications because they were easily degraded by endogenous nucleases (8). Several structural modifications in the parent molecule have yielded nuclease resistant analogs (9). Phosphorothioate ODNs constitute one class of stable derivatives which show good absorption, rapid distribution and prolonged retention in tissues, and are preferred for antisense applications (10). Currently, one drug based on the antisense strategy has been approved by the FDA, and clinical evaluation of many other antisense phosphorothioate ODNs and DNA–RNA oligomer chimeras is underway (7).

Cellular uptake of ODNs has been shown to take place by two distinct mechanisms: receptor-mediated endocytosis (11) and a receptor-independent process (12,13). It has been demonstrated that uptake of some ODNs significantly increases in some cell lines in the presence of divalent cations (14), specifically Ca2+ (15). It has been suggested that receptor-independent uptake may be due to an interaction between the ODNs and the cell membrane mediated by divalent cations. These divalent cations may induce structural or conformational changes either in the cellular lipid bilayer, the ODNs or both, which may facilitate the entry of the ODNs in the cell. To better understand this mechanism, we investigated the effect of divalent ions on the conformation of several ODNs using circular dichroism (CD). CD is a valuable technique because conformational information can be obtained with low amounts of the analyte and the method is particularly appropriate for dilute aqueous solutions of ODNs. CD has been successfully used in conformational studies of DNA structures involving duplexes, triplexes, tetraplexes, hairpins and RNA/DNA hybrids (16,17).

Interactions of metal ions with DNA have been studied extensively. Divalent ions can induce specific changes in duplex DNA (18). Minasov et al. have demonstrated that dsDNA can be crystallized in different crystal forms in the presence of Ca2+ or Mg2+ because these ions have unique interactions with the dsDNA (19). CD spectroscopy has been used to monitor changes in conformation of duplex DNA by metal ions. Ions such as Mg2+ and Co2+ induced a Z→B transition in duplexes of d(CCGGGCCCGG) and Al+3 induced a Z→A transition, but Mn2+ did not induce any transition (20). These changes were specific to the ion and the ODN. Behe and Felsenfeld have demonstrated that heavy metals like Ba2+ can induce a B→Z transition in poly(dG–dC) sequences in the presence of Na+ (21).

In this work we focus on the effect of divalent cations on the conformation of single-stranded phosphorothioate DNA. Several representative structures have been investigated, including a homopolymer, ‘random’ sequences and G4 containing sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All salts and buffer components were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). All water was obtained from a Barnstead Nanopure water system. All phosphorothioate ODNs were donated by Isis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA) and were used without further purification. The sequences for these molecules are shown in Table 1. Spectra were collected using a Jasco model 710 or 715 CD spectrometer at 20°C, using a quartz cuvette (Starna Cells) with a 10 mm pathlength in a thermostatted holder. CD spectra were collected from 350 to 200 nm in 0.1 nm increments. Three scans were accumulated and averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Stock aqueous solutions (0.2 mM) of phosphorothioate ODNs were stored at 4°C. Concentrations of the stock solution were verified by measuring OD260 at 20ºC and estimating molar extinction coefficient by base composition. Although concentrations for a given ODN were quite reproducible, there was some variability from one molecule to another due, apparently, to water content. After running a blank spectrum with buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), an aliquot of ODN stock was added to the cuvette to yield a final concentration of 5 µM. Divalent cation (chloride) stocks were made gravimetrically in polycarbonate labware using ultrapure water. Divalent cations were added by removing small aliquots of ODN solution from the cuvette and replacing it with equal volumes of the divalent cation stock. CD data were collected for the ion-containing solution and the process continued to a final concentration of at least 12 mM divalent cation chloride. All data were collected in duplicate or triplicate. The concentration of the ODN solution decreased by 6–7% over a complete set of measurements and final results were corrected for this dilution effect. Raw data (ellipticity, 2, in millidegrees) were corrected for molar concentration of the ODN (C, molar) and pathlength (l, centimeters), and were converted to molar ellipticity (Δε, dm3 mol–1 cm–1) using Δε = θ/32 980 Cl.

Table 1. Sequences of the seven oligonucleotides used in this work.

|

1 |

5′-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ |

|

2 |

5′-GCCGAGGTCCATGTCGTACGC-3′ |

|

3 |

5′-GTGGGCCATGATGATGGAAGG-3′ |

|

4 |

5′-CACGAAAGGCATGACCGGGGC-3′ |

|

5 |

5′-GGGGTTGGGG-3′ |

|

6 |

5′-GGGGTTGGGGTTGGGG-3′ |

| 7 | 5′-TTGGGGTTGGGGTTGGGGTT-3′ |

RESULTS

Each ODN demonstrated a unique CD spectrum in buffer. Figure 1 shows the spectra of the seven ODNs used in this work. Two of these spectra (1, 2) have characteristics of B-DNA spectra and three (5, 6 and 7) suggest G-tetraplex. Complete sets of spectra showing ion dependence are shown for one B-DNA-like structure (Fig. 2) and one G-DNA structure (Fig. 3). Control experiments were performed using NaCl at concentrations selected to match the range of ionic strength in the divalent cation solutions. NaCl has essentially no effect on the CD spectra of these oligonucleotides at concentrations as high as 95 mM (data not shown). By comparison, molar ellipticities increased as much as 3-fold with divalent cation of the same ionic strength.

Figure 1.

CD spectra for solutions of T23 (1), mixed-composition oligonucleotides (2, 3) and G4-containing oligonucleotides (4–7) in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4).

Figure 2.

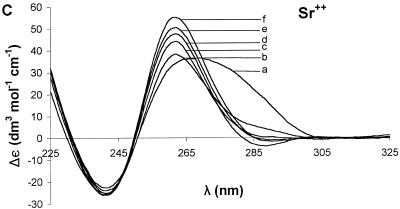

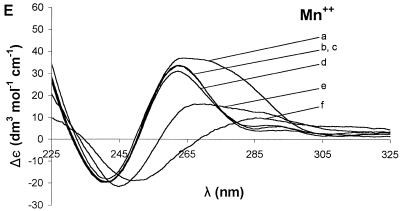

Ion dependence of Δε for 3. Sequential addition of divalent cation resulted in different changes in the CD spectrum for each ion: Mg2+ (A), Ca2+ (B), Sr2+ (C), Ba2+ (D) and Mn2+ (E). The broad curve in each case is the oligonucleotide without added divalent cation. For all of the group II ions, the highest molar ellipticity was obtained at the highest ion concentration. The curves represent concentrations (mM) of 0 (a), 0.25 (b), 1.50 (c), 3.98 (d), 12.15 (e) and 27.80 (f).

Figure 3.

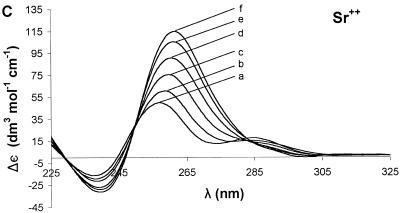

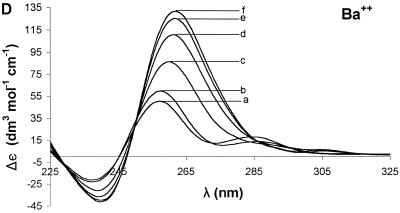

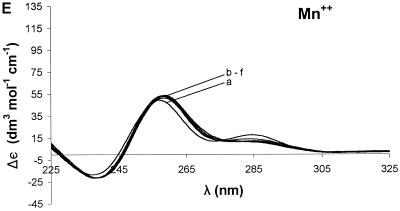

Ion dependence of Δε for 7, G4-containing oligonucleotide. Sequential addition of divalent cations Mg2+ (A), Ca2+ (B), Sr2+ (C), Ba2+ (D) and Mn2+ (E) resulted in different changes in the CD spectrum for each ion. For all of the group II ions, the highest molar ellipticity was obtained at the highest ion concentration. The curves represent concentrations (mM) of 0 (a), 0.25 (b), 1.50 (c), 3.98 (d), 12.15 (e) and 27.80 (f).

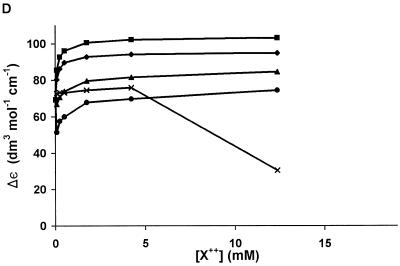

The dependence of the CD spectra on specific ions as a function of concentration is shown in Figure 4A–G. These plots of Δε versus [X2+] are based solely on maximum peak height, and do not reflect any shifts in peak positions. For example, in the absence of divalent cations, the maximum molar ellipticity of 3 was 31.83 at 265 nm. Upon addition of 27.8 mM Ba2+, the molar ellipticity at 265 nm was 42.8 but the maximum molar ellipticity was 45.7 at λ = 260 nm. The latter value was used in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Dependence of Δε on divalent ion concentration. In each figure, the average magnitude of the error bars is indicated in the bar in the lower right corner. The error was similar for all traces in each figure except for some of the Mn2+ data, which exhibited greater deviation at concentrations below 10 mM (Mg2+, diamond; Ca2+, square; Sr2+, triangle; Ba2+, circle; Mn2+, ×). (A–G) Oligodeoxynucleotides 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, respectively. The values of Δε plotted are peak values. So in general, the wavelength at which the data were obtained shifts slightly with concentration.

(1) This is a homopolymer of thymine residues. As shown in Figure 1, the CD spectrum of 1 had a characteristic positive band at ~275 nm, and a negative band at ~250 nm. None of the divalent cations tested caused a significant change to its spectrum (Fig. 4A).

(2) Sequence 2 is a ‘random’ oligomer of A, T, G and C. The CD spectrum (Fig. 1) of this ODN also showed a characteristic positive band at ~275 nm, and a negative band at ~240 nm. As observed for 1, this ODN exhibited negligible change in its conformation upon addition of Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+ or Ba2+ (Fig. 4B). However, the addition of Mn2+ led to a significant loss of intensity for all CD bands, suggesting that interaction with Mn2+ disrupted the ordered secondary structure of 2.

(3) This G-rich sequence has a guanine triplet and a six-purine sequence at the 3′ end, but the guanines are widely distributed. The CD spectrum of 3 (Fig. 1) had a broad positive band at ~265 nm and a negative band at ~240 nm, with zero crossing at 250 nm. For this ODN, there was a small increase in the molar ellipticity upon addition of Mg2+ (Fig. 2A), Ca2+ (Fig. 2B) or Ba2+ (Fig. 2D). Sr2+ (Fig. 2C) led to a greater increase in the molar ellipticity than other ions tested. All increases in the molar ellipticity were accompanied by a narrowing of the positive band at ~265 nm. However, as with 2, Mn2+ caused a significant loss of the CD signal (Fig. 2E). The ion effects are summarized in Figure 4C.

(4) This ODN has a single G4 sequence near the 3′ end of the molecule and the rest of the molecule is of heterogeneous composition. The CD spectrum of 4 (Fig. 1) was similar to that of 3, except that the positive band of 4 at ~265 nm had a broader maximum. Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+ or Ba2+ ions induced small changes in the conformation of the molecule, characterized by conversion of the broad band to a narrower band at ~265 nm (Fig. 4D). There are also minor differences in the maximum molar ellipticity. Addition of Mn2+ to 4 led to disruption of its structure, evident from a greatly diminished CD spectrum.

(5) This is a short, 10-base ODN: G4T2G4. This sequence (Fig. 1) showed two negative bands at ~240 and ~275 nm, a positive band at ~260 nm, and a small positive band at ~295 nm. Mg2+ caused a small increase in the large positive band, but addition of Ca2+, Sr2+ and Ba2+ caused the positive band of the spectrum to increase significantly. Ca2+, Sr2+ or Ba2+ at 27.8 mM concentration caused increases of ~45, ~115 and ~115%, respectively, in the initial molar ellipticity of the positive band at ~260 nm (Fig. 4E). The small band observed at ~295 nm either diminished or remained the same. The final conformation of the ODN was characterized by a single positive band at ~260 nm and a negative band at ~240 nm. Mn2+ led to a small decrease in the molar ellipticity, suggesting destabilization of the structure, but this effect was not as significant as was observed for 2 or 3.

(6, 7) These ODNs are also characterized primarily by G4 sequences. Each molecule has three G4 sequences separated by T2. The only difference is that 7 has T2 sequence at the 3′ and 5′ ends. Molecules 6 and 7 showed (Fig. 1) very similar spectral features, characterized by a negative CD band at ~240 nm, a zero crossing at ~245 nm, a positive band at ~260 nm, and a second positive band at ~295 nm for 6 and ~285 nm for 7. In each case, the two positive bands were separated by a minimum at ~275 nm.

The effect of ions was similar for 6 and 7. Addition of 27.8 mM Mg2+ to 6 increased the molar ellipticity of the positive band at ~255 nm by 50% and shifted the band to ~265 nm. The positive band at ~295 nm remained unchanged (Fig. 4F). Addition of Ca2+, Sr2+ or Ba2+ induced a similar change but the increase in the molar ellipticity was much greater, increasing by 350, 325 and 200% for 27.8 mM Ca2+, Sr2+ and Ba2+, respectively. At these ion concentrations, the spectrum appeared as a single positive band at ~265 nm. Addition of 27.8 mM Mn2+ increased the initial molar ellipticity of the positive band at ~255 nm by 185%.

The addition of ions to 7 showed a similar effect (Figs 3 and 4G), but the sensitivity to each ion was different. Addition of 27.8 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 3A), Ca2+ (Fig. 3B), Sr2+ (Fig. 3C) or Ba2+ (Fig. 3D) shifted the positive band at ~255 nm to ~265 nm. For 7, the ions tested increased the molar ellipticity of the positive band in the following order: Mg2+ (20%) < Ca2+ (45%) < Sr2+ (130%) < Ba2+ (165%). Mn2+ had no effect on the positive band at ~255 nm (Fig. 3E).

The positive band at ~295 nm in the CD spectrum of 6 also showed ion-specific effects. Addition of Ca2+ or Mn2+ converted the positive band into a small negative band, Sr2+ decreased the initial molar ellipticity by 50%, and Ba2+ increased the molar ellipticity by 100%. Sr2+ and Ba2+ each caused a bathochromic shift in the positive band to 305 nm. The positive band at ~295 nm in the CD spectrum of 7 was completely eliminated by addition of any of the ions tested except Mg2+, which had no effect (Figs 3A–4E).

DISCUSSION

The CD spectrum of proteins and oligonucleotides is an indicator of their overall secondary structure. The various forms of duplex DNA (A, B and Z) have unique spectral characteristics due to differences in conformation in the helical backbone (22), and these DNA conformations have been identified and distinguished using CD spectroscopy. B-DNA has been shown to have a characteristic CD spectrum with a positive band centered at ~275 nm, a negative band at ~240 nm, with zero at ~258 nm (22).

It has been demonstrated that DNA sequences with a continuous stretch of guanines, as observed in naturally occurring chromosomal telomeric sequences, can self-associate to form four-stranded helical structures known as G-DNA tetraplexes (23,24). The G-DNA tetraplex typically consists of cyclic complexes of four guanine bases linked by Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding. This creates a pocket in the center of the helix that is lined by electronegative carbonyl oxygens. The orientation of the guanine in the strands determines the specific interactions of the association and dictates the final conformation of the G-tetraplex. G-DNA tetraplexes can have a parallel or antiparallel conformation, which can be differentiated on the basis of their unique CD spectra (25,26). In parallel tetraplex structures, all the guanines are in the anti conformation, resulting in a characteristic CD spectrum with a positive band at ~265 nm and a negative band at ~240 nm. In antiparallel tetraplexes, the guanines are in alternating syn and anti conformations, and the resulting CD spectrum has a positive band at ~295 nm and a negative band at ~265 nm. Although long continuous sequences of guanine form stable tetraplexes, short ODNs, as small as d(TGGGT), have been shown by NMR to form G-DNA tetraplexes (23).

In the absence of divalent cations, 1 and 2 showed spectral features characteristic of B-DNA. Due to the presence of some sequential guanines in their structure, 3 and 4 can form a G-tetraplex structure to some degree, but most of the sequence in these molecules is ‘random’ and will have a secondary structure other than a G-DNA tetraplex. Thus, the overall molar ellipticity will be from two structural components. Since the major positive bands in the CD spectra of B-DNA and parallel G-DNA tetraplex are separated by only 15 nm (260 and 275 nm for B-DNA and parallel G-DNA tetraplex, respectively), the two components are not resolved, resulting in broad spectra. The resultant positive band in the CD spectrum of 3 and 4 was spread over a wider range than would be expected from G-tetraplexes alone. The CD spectrum of 5 was similar to that reported previously (26), with predominant characteristics of parallel G-tetraplex. Spectra from 6 and 7, which have three G4 sequences in their structures, had spectral features of both parallel and antiparallel G-tetraplexes, indicating the presence of both conformers.

It has been reported in previous studies that monovalent and divalent ions can affect the structure of G-DNA tetraplexes (27,28). Cations occupy the central cavity of the G-tetraplexes by interacting with the keto-oxygens bordering them, but some structural variations may arise with different ions. Roles of the hydration energies of the ions and their radii are strongly implicated in models used to describe ion binding in G-tetraplexes (23,29). This cation interaction in the pocket is a unique feature of G-DNA tetraplexes, which distinguishes them from other DNA structures.

Monovalent ions generally stabilize G-DNA tetraplexes in the order of K+ > Na+ > Cs+ > Li+ (27,30). Maximum stability is obtained with K+ because the ionic radius is ideal for complex formation in this structure (23). A solution structure of a parallel-stranded G-tetraplex of d(TG4T) stabilized by Na+ has been elucidated by NMR (23). Monovalent cations cannot only stabilize G-tetraplexes but can also induce conversions between the parallel and antiparallel conformations. Balagurumoorty et al. have shown that in solutions of d(G4TnG4) sequences (where n = 1–4), having both conformers of the G-tetraplex, K+ ions shift the equilibrium toward parallel stranded structures (26).

The role of divalent ions in the stabilization of G-tetraplexes has been investigated to a relatively limited extent. Divalent ions can stabilize G-tetraplexes at lower concentrations than is required by monovalent ions (31,32). Hardin et al. have shown that an ODN with a central G3 can be stabilized by Ca2+ or Mg2+, with the Ca2+ induced conformation being more stable (27). It has also been shown that Mg2+ or Ca2+ at 10 mM concentration favored the formation of parallel G-DNA tetraplexes over the antiparallel conformation (33). Chen has demonstrated that Sr2+, which has an ionic radius similar to that of K+, can also stabilize G-tetraplexes (34).

It must be noted that most previously published work (27,32–34) involved formation of ion–ODN complexes by incubation for 2–3 days. These were identified and confirmed by their mobility on gel electrophoresis. Compared to previously published experiments, the present study involves characterization of rapid changes in the conformation of phosphorothioate ODNs induced by various divalent ions over a wide concentration range. Addition of an aliquot of divalent cation stock and collection of a spectrum took ~10 min, and a complete concentration series could be collected in 1 h. Thus, shifts in the CD spectra in these studies represent conformational changes which occurred in the timeframe of minutes, rather than days.

Divalent ions stabilized the G-tetraplex, presumably by occupying the central core, and could also interact with other ODNs to cause destabilization of the secondary structure. The extent of these effects depended upon the individual ODN sequence and the ion. Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+ and Ba2+ generally had structure-stabilizing effects on the G-tetraplex forming ODNs as evident by the increase in the molar ellipticity at 265 nm. These ions might stabilize the tetraplex, so that the number of molecules in tetraplex was increased or the conformations are more representative of G-DNA. Figure 2B–E shows that as little as 250 µM divalent cation could change a broad band in the CD spectrum of 3 into a sharper band characteristic of a parallel G-tetraplex structure.

Although addition of divalent ions often promoted the formation of parallel G-tetraplexes structures, the specific effects were unique to the ODNs and the ions involved. For example, as seen in Figure 3, the effects of these ions varied even for the same ODN. The intensity of the CD spectrum of 7 is enhanced in the order of Ba2+ > Sr2+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. Each ion led to an increase in the molar ellipticity at ~265 nm and a corresponding decrease in the positive band at ~295 nm, indicating formation of parallel G-tetraplexes and a concurrent decrease in antiparallel G-tetraplexes. This suggests that these divalent cations selectively facilitate formation of a particular conformation in a concentration-dependent manner. Unfortunately this trend cannot, strictly speaking, be generalized to other ODNs, even for those with very similar features. For example, 6 has a similar G4–T2 sequence, but 6 did not show a significant preference for any particular divalent cation in stabilizing the tetraplex. For 6, Ca2+ led to the greatest stabilization of the tetraplex, based on an increase in the molar ellipticity at ~265 nm.

In most cases, Ba2+ led to stabilization of the parallel G-tetraplex over the antiparallel G-tetraplex. For 7, addition of 27.8 mM Ba2+ (Fig. 3D) increased the molar ellipticity of the positive band at ~265 nm by ~165% and diminished the molar ellipticity near the band at ~295 nm. For 6, however, addition of 27.8 mM Ba2+ not only increased the molar ellipticity of the band at ~265 nm by ~200%, but also increased the molar ellipticity of the band at ~295 nm by ~100% (data not shown). This suggests that Ba2+ stabilizes both the parallel and antiparallel G-tetraplex structures in 6 while only stabilizing the parallel structures in 7.

The effect of Mn2+ was strikingly different in the various ODNs. For 1 (Fig. 4A), Mn2+ did not produce any significant change in the conformation. For ODNs with few or ‘randomly’ distributed guanines in their sequence or those which lack a strong drive for tetraplex assembly, Mn2+ apparently destabilized the secondary structure. This was observed for 2 (Fig. 4B), 3 (Fig. 4C) and 4 (Fig. 4D) in which Mn2+ decreased the molar ellipticity significantly. This effect of Mn2+ may be due to condensation effect of the ODN or its conversion into a different secondary form as suggested in a previous study (35). For some G4-containing sequences such as 5 and 7, Mn2+ did not induce any significant change in secondary structure for concentrations up to 27.08 mM. This apparent stability to Mn2+ may originate in the distinct ion binding sites in G4-containing structures. This is supported by the fact that Mn2+ stabilized the parallel G-tetraplex structure for 6.

CONCLUSION

The conformations of single-stranded phosphorothioate ODNs exhibit significant and specific conformational changes in response to a variety of divalent cations. These changes in conformation are due to the stabilizing or destabilizing effects of divalent ions on the hyperstructures formed by these ODNs in solution. Changes in the conformation are not simply due to ionic strength effects. These sequence-dependent, divalent ion-sensitive, and structurally unique solution conformations may be significant to ODN uptake.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to Mr Luan Nguyen whose undergraduate research project helped to define proper conditions for this work. The authors would also like to thank Drs Yeagle, Albert, Kumar and Witczak for the use of their instrumentation. This work was supported by Isis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., which provided all oligonucleotides, and the University of Connecticut Research Foundation, which provided support for preliminary studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal S. (1996) Antisense Therapeutics. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

- 2.Crooke S.T. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1489, 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crooke S.T. (1999) Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 9, 377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stull R.A., and Szoka,F.C.,Jr (1995) Pharmacol. Res., 12, 465–483. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy D.S. (1996) Drugs Today, 32, 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho P.T., and Parkinson,D.R. (1997) Semin. Oncol., 24, 187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemunaitis J., Holmlund,J.T., Kraynak,M., Richards,D., Bruce,J., Ognoskie,N., Kwoh,T.J., Geary,R., Dorr,A., Von Hoff,D. and Eckhardt,S.G. (1999) J. Clin. Oncol., 17, 3586–3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook P.D. (1991) Anticancer Drug Des., 6, 585–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matteucci M. (1996) Perspect. Drug Discovery Des., 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crooke S.T. (1997) In Chadwick,D.J. and Cardew,G. (eds), Oligonucleotides As Therapeutic Agents. Wiley, Chichester, NY, pp. 158–168.

- 11.Biessen E.A.L., Vietsch,H., Kuiper,J., Bijsterbosch,M.K. and van Berkel,T.J.C. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol., 53, 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loke S.L., Stein,C.A., Zhang,X.H., Mori.K., Nakanishi,M., Subasinghe,C., Cohen,J.S. and Neckers,L.M. (1989) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 3474–3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu-Pong S., Weiss,T.L. and Hunt,C.A. (1992) Pharmacol. Res., 9, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu-Pong S. (1996) Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int., 39, 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu-Pong S., Weiss,T.L. and Hunt,A. (1992) Cell. Mol. Biol. Paris, 40, 843–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashem G.M., Pham,L., Vaughan,M.R. and Gray,D.M. (1998) Biochemistry, 37, 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xueguang S., Enhua,C., Chunli,B., Yujian,H. and Jingfen,Q. (1998) Chin. Sci. Bull., 43, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippert B. and Leng,M. (1999) Top. Biol. Inorg. Chem., 1, 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minasov G., Tereshko,V. and Egli,M. (1999) J. Mol. Biol., 291, 83–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champion C.S., Kumar,D., Rajan,M.T., Jagannatha Rao,K.S. and Viswamitra,M.A. (1998) Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 54, 488–496. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behe M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1981) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 78, 1619–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodger A. and Norden,B. (1997) Circular Dichroism and Linear Dichroism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, NY, pp. 23–31.

- 23.Williamson J.R. (1994) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 23, 703–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balagurumoorthy P. and Brahmachari,S.K. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 21858–21869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venczel E.A. and Sen,D. (1993) Biochemistry, 32, 6220–6228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balagurumoorthy P., Brahmachari,S.K., Mohanty,D., Bansal,M. and Sasisekharan,V. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4061–4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardin C.C., Watson,T., Corregan,M. and Bailey,C. (1992) Biochemistry, 31, 833–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scaria P.V., ShireS.J. and Shafer,R.H. (1992) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 10336–10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson J.R., Raghuraman,M.K. and Cech,T.R. (1989) Cell, 59, 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu M., Guo,Q. and Kallenbach,N.R. (1992) Biochemistry, 31, 2455–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schierer T. and Henderson,E. (1994) Biochemistry, 33, 2240–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marotta S.P., Tamburi,P.A. and Sheardy,R.D. (1996) Biochemistry, 35, 10484–10492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sen D. and Gilbert,W. (1992) In Sarma,R.H. and Sarma,M.A. (eds), Structure and Function, Volume 1: Nucleic Acids. Adenine Press, Guilderland, NY, pp. 43–52.

- 34.Chen F. (1992) Biochemistry, 31, 3769–3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrushchenko V.V., van de Sande,J.H. and Wieser,H. (1999) Vib. Spectrosc., 19, 341–345. [Google Scholar]