Abstract

Background:

Andersen-Tawil Syndrome Type 1 (ATS1) is a rare heritable disease caused by mutations in the strong inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir2.1. The extracellular Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bond in the Kir2.1 channel structure is crucial for proper folding, but has not been associated with correct channel function at the membrane. We tested whether a human mutation at the Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bridge leads to Kir2.1 channel dysfunction and arrhythmias by reorganizing the overall Kir2.1 channel structure and destabilizing the open state of the channel.

Methods and Results:

We identified a Kir2.1 loss-of-function mutation in Cys122 (c.366 A>T; p.Cys122Tyr) in a family with ATS1. To study the consequences of this mutation on Kir2.1 function we generated a cardiac specific mouse model expressing the Kir2.1C122Y mutation. Kir2.1C122Y animals recapitulated the abnormal ECG features of ATS1, like QT prolongation, conduction defects, and increased arrhythmia susceptibility. Kir2.1C122Y mouse cardiomyocytes showed significantly reduced inward rectifier K+ (IK1) and inward Na+ (INa) current densities independently of normal trafficking ability and localization at the sarcolemma and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Kir2.1C122Y formed heterotetramers with wildtype (WT) subunits. However, molecular dynamic modeling predicted that the Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide-bond break induced by the C122Y mutation provoked a conformational change over the 2000 ns simulation, characterized by larger loss of the hydrogen bonds between Kir2.1 and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) than WT. Therefore, consistent with the inability of Kir2.1C122Y channels to bind directly to PIP2 in bioluminescence resonance energy transfer experiments, the PIP2 binding pocket was destabilized, resulting in a lower conductance state compared with WT. Accordingly, on inside-out patch-clamping the C122Y mutation significantly blunted Kir2.1 sensitivity to increasing PIP2 concentrations.

Conclusion:

The extracellular Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bond in the tridimensional Kir2.1 channel structure is essential to channel function. We demonstrated that ATS1 mutations that break disulfide bonds in the extracellular domain disrupt PIP2-dependent regulation, leading to channel dysfunction and life-threatening arrhythmias.

Keywords: Ion channel diseases, Kir2.1-PIP2 interaction, Arrhythmias, Sudden Cardiac Death, Molecular Dynamics

Introduction

Andersen-Tawil syndrome type 1 (ATS1) is a rare, inheritable autosomal dominant disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in the KCNJ2 gene, which codes the strong inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.1.1,2 Kir2.1 is ubiquitously expressed throughout the human body and ATS1 mutations predispose patients to a triad of alterations including periodic paralysis, dysmorphias, and arrhythmias that can lead to sudden cardiac death (SCD)3,4 by mechanisms that remain unclear.5 In the heart, Kir2.1 is responsible for the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1),6 which plays a central role in the maintenance of the resting membrane potential (RMP) and the final phase of action potential (AP) repolarization.7 Therefore, loss-of-function mutations in Kir2.1 lead to a substantial decrease in IK1, with consequent membrane depolarization at rest, as well as AP duration (APD) and QT interval prolongation.8 Normal Kir2.1 channel function requires agonist phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphospate (PIP2) interactions, which stabilizes the G-loop in the open state. Defects in PIP2 binding are a major pathophysiologic mechanism underlying the loss-of-function phenotype for several ATS1 associated mutations.5,9–11

The primary structure of the human Kir2.1 channel comprises a total of thirteen cysteine (Cys) residues distributed along each monomer. Cys residues are uniquely reactive providing the ability to form disulfide bonds.12 They contribute to the structural stability of proteins while being key target sites for redox related processes.13 Thus, Cys mutations may affect the tridimensional structure of the channel and alter its function. Seven Cys are expected to be distributed in the Kir2.1 channel N- and C-terminus regions, but mutation in most of them have not been shown to significantly affect the single-channel conductance nor the channel open probability.14 However, mutating Cys76 and Cys311 to polar or charged residues modulated the interaction between Kir2.1 and PIP2, and resulted in either an absence of channel activity or a decrease in open probability.14 Similarly, class Ic antiarrhythmic drugs have been shown to bind to the Cys311 residue of the Kir2.1 channel, and to reduce the polyamine-induced inward rectification increasing the outward IK1.15,16 Four Cys residues are located in the channel transmembrane segment TM1 (Cys89 and Cys101), the pore (Cys149) and TM2 regions (Cys169). Importantly, the remaining two Cys, Cys122 and Cys154, are located at extracellular space positions absolutely conserved across the inward rectifier family,17 and form a disulfide bond crucial for channel assembly.12,18,19 However, the Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bridge has not been considered essential for normal Kir2.1 function once the channel has been formed.12

Here we report on an ATS1 family with a novel Kir2.1 loss-of-function mutation in Cys122 (c.366 A>T; p.Cys122Tyr) (C122Y) with a high prevalence for ventricular arrhythmias, which in the case of the proband required implantation of an intracardiac defibrillator (ICD). To study the molecular mechanisms underlying life-threatening arrhythmias produced by the Kir2.1C122Y mutation, we generated a mouse model of ATS1 using adeno-associated virus (AAVs) Kir2.1C122Y gene transfer that recapitulates the ATS1 phenotype. We used a multidisciplinary approach that included patch-clamping, electrophysiological stimulation, as well as molecular biology, molecular dynamic (MD) modelling, and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) to demonstrate that a disulfide bond break in the Kir2.1 extracellular domain disrupts PIP2-dependent regulation, leading to channel dysfunction and triggering life-threatening arrhythmias.

Materials & Methods

See Supplemental Methods for more detail

Ethics Statement.

All animal experiment procedures conformed to EU Directive 2010/63EU and Recommendation 2007/526/EC. Skin biopsies were obtained from one patient carrying the Kir2.1 C122Y mutation after written informed consent, and consent to publish, in accordance with the Ethical Committee for Research of CNIC and the Carlos III Institute (CEI PI58_2019-v3), Madrid, Spain. Animal protocols were approved by the local ethics committees and the Animal Protection Area of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (PROEX 111.4/20).

Mice.

C57BL/6J mice, 4–5-weeks-old, were obtained from the Charles River Laboratories, and reared and housed in accordance with CNIC animal facility guidelines and regulations.

Adeno-associated virus vector production, purification and mouse model generation.

AAV vectors were generated using the cardiomyocyte-specific cardiac TroponinT proximal promoter (cTnT) and encoding wildtype Kir2.1 (Kir2.1WT) or the ATS1 Kir2.1 mutant (Kir2.1C122Y), followed by tdTomato report. Vectors were packaged into AAV serotype 9 (AVV9) and produced by the triple transfection method, using HEK293T cells as described previously20,21. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg) via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route. Thereafter, 3.5×1010 virus particles were inoculated intravenously (i.v.) through the femoral vein in a final volume of 50μL. Only well-inoculated animals were included in the studies. All experiments were performed 8-to-10 weeks after infection. Ex-vivo fluorescent signal confirming cardiac expression and distribution of protein expression was assessed as described.22

Echocardiography.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed blindly by an expert operator using a high-frequency ultrasound system (Vevo 2100, VisualSonics Inc., Canada) with a 40-MHz linear probe, and analyzed as described (in Supplemental Methods).

Surface ECG recording.

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation (0.8–1.0% volume in oxygen). Four-lead surface ECGs were recorded for 5 minutes using subcutaneous limb electrodes connected to an MP36R amplifier unit (BIOPAC Systems). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using AcqKnowledge software.

In-vivo intracardiac recording and stimulation.

An octopolar catheter (Science) was inserted through the jugular vein and advanced into the right atrium (RA) and ventricle (RV) as previously described.23 Atrial and ventricular arrhythmia inducibility was assessed by applying consecutive trains at 10Hz and 25Hz, respectively.

Cardiomyocyte isolation.

The procedure was performed as described by Macías et al.24 (See Supplemental Methods).

Membrane fractionation, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Total protein was obtained from isolated Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes using RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS and 0.1% Sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and quantified by BCA protein assay (Bio-Rad). A total amount of 50 µg of protein was resolved in each lane on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, electrotransferred onto 0.2 µm PVDF membrane (BioRad) and probed with specific antibodies. For membrane fractionation, cells were extracted and homogenized in ice-cold homogenization medium. After lysis, protein extract was processed according to manufacturer’s specifications (Abcam). See further details in the Supplemental Methods.

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) Lipid binding assay.

HEK293T cells were transfected with 2 µg of plasmid encoding Kir2.1WT or Kir2.1C122Y protein fused with Nluc (nanoluciferase) in the C-terminal region. After 48h, the BRET assay was done in a 96-well plate as previously described.25 See Supplemental Methods for details.

Patch-clamping in isolated cardiomyocytes.

The whole-cell patch-clamp technique and data analysis procedures and internal and external solutions (Supplementary Table 1) were similar to those previously described.9–13 Details are presented in the Supplemental Methods.

Calcium dynamics assays.

Cytosolic Ca2+ was monitored according to previously described protocols.26–28 Briefly, cells were loaded with Fluo-4-AM (Invitrogen). Fluorescence was detected in line scan mode (usually 2 ms/scan), with the line drawn approximately through the center of the cell and parallel to its long axis.

Dynamic modeling to predict Kir2.1-PIP2 interaction.

For each monomer we used the pre-opened state of Kir2.2 bound to PiP2 as a template (PDB code 3SPH) to conduct molecular dynamics (MD) modelling. We generated homology PiP2 models binding to Kir2.1WT, Kir2.1C122Y homotetramer and Kir2.1WT/C122Y heterotetramer to study Kir2.1-PiP2 interactions using 2000 ns MD. The CHARMM-GUI server allowed us to simulate both membrane and environment. - Please see Supplemental Methods for detailed description of the procedures.

Statistical analyses.

We used GraphPad Prism software version 7.0 and 8.0. In general, comparisons were made using Student’s t-test. Unless otherwise stated, we used one- or two-way ANOVA for comparison among more than two groups and Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and differences are considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

Life-threatening arrhythmias in an ATS1 family with the Kir2.1C122Y mutation

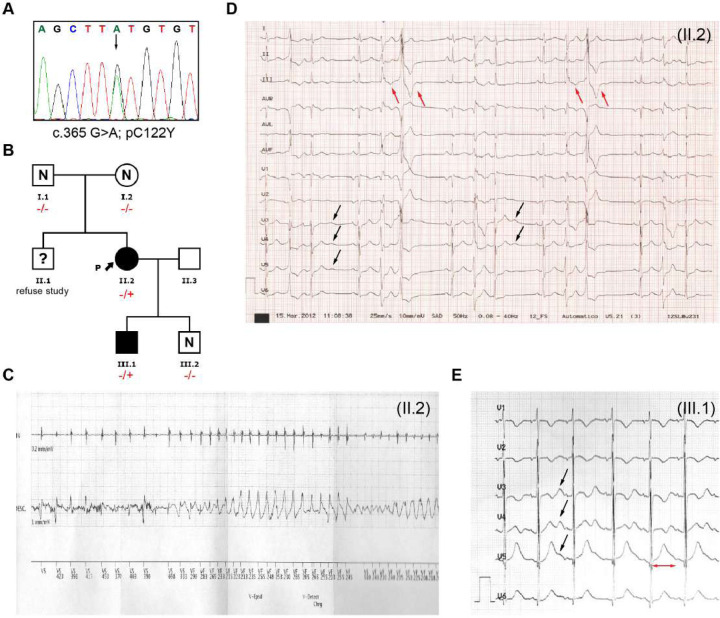

We screened a family with members suffering numerous idiopathic sudden loss-of-consciousness episodes using a targeted sequencing gene panel involved in arrhythmias (RYR2, CASQ2, TRDN, CALM1 and KCNJ2). We identified a novel de novo potential pathogenic heterozygous missense variant c.365 A>T; p.Cys122Trp of the KCNJ2 gene for ATS1 (LQTS type 7) in two family members (Figure 1A–B). The proband (patient II.2) was a 16-year-old female of Caucasian origin who experienced several sudden loss of consciousness events of unknown origin. Initially, patient II.2 was diagnosed with mitral valve prolapse of the anterior leaflet without hemodynamic repercussions. The electrophysiological study was negative following a hospital admission for syncope and subsequent evidence of polymorphic ventricular extrasystoles refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs (propafenone, mexiletine and lidocaine). She continued with propranolol treatment (120 mg/d) combined with oral mexiletine (200mg/8h). At age 23, a single-chamber cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was implanted after several episodes of syncopal polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT) and registering three appropriate discharges throughout ages 25–35 during sodium channel blocker administration (Figure 1C). ECG analysis revealed a corrected QT (QTc) interval in the upper limit of the normal range (470 ms) with pronounced U waves and polymorphic extrasystoles with frequent trigeminy episodes (Figure 1D). She is now 45 and currently under treatment with nadolol 120 mg/d and spironolactone 25 mg/d. The probandś son (patient III.1) remains asymptomatic at the age of 8. However, ECG analysis revealed a prolonged QTc interval of 490 ms with a widened T wave and prominent U waves (Figure 1E), consistent with ATS1 symptoms.

Figure 1. Genetics and ECG phenotype of ATS1 family members with Kir2.1C122Y mutation.

A: DNA sequences derived from probandś genomic DNA. The trace shows a heterozygous substitution of guanine to adenine resulting in the C122Y amino acid change. B: Family pedigree according to the carrier status of the p.Cys122Tyr KCNJ2 gene variant. Males and females are marked with squares and circles, respectively. Mutation carriers are marked with (−/+) and non-carriers with (−/−). Uncertain mutation carriers are marked with (?) and non-affected with (N). Phenotype positive individuals are marked in black. Proband is indicated with black arrow and (P). C. Twelve-lead ECG of proband (II.2) at age 23, showing an episode of syncopal polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during sodium channel blocker (Mexiletine; 600mg/day) treatment combined with β-blocker therapy (Propranolol; 20mg/12h) D: ECG of the proband (II.2) showing typical Andersen-Tawil Syndrome abnormalities. Prominent U waves are marked by black arrows. Bidirectional ventricular extrasystoles are marked by red arrows. E: ECG from individual III.1 demonstrating genotype-phenotype segregation. Prominent U waves are marked with black arrows. Broad T wave and QTc interval prolongation is marked by a red line (510 ms).

Cardiac conduction defects and arrhythmias in Kir2.1C122Y mice

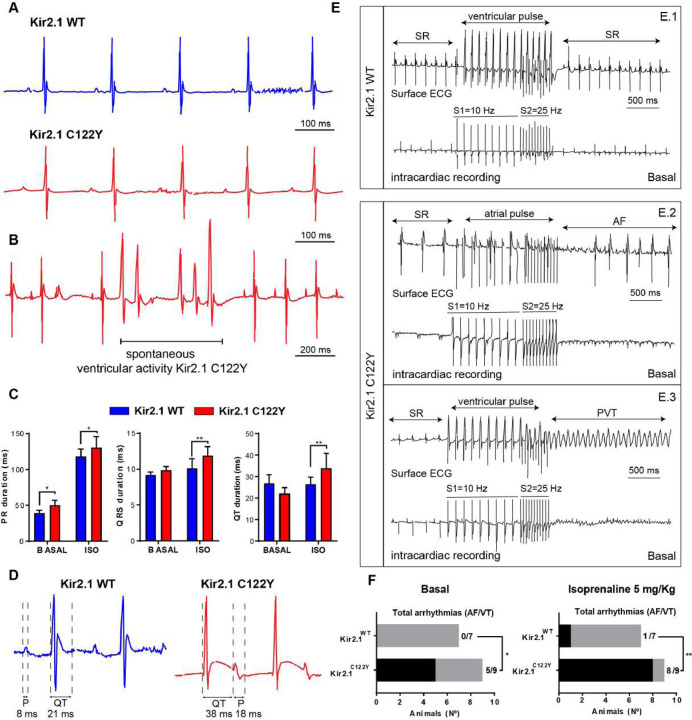

We used intravenous AAV-mediated cardiac specific gene transfer22 to generate mice expressing Kir2.1WT or Kir2.1C122Y. We confirmed AAV infection throughout the heart and that cardiomyocytes stably expressed the specific targeted transgenes (Supplemental Figure 1), with no cardiac morphological changes or contractile dysfunction evaluated by echocardiography (Supplemental Figure 1C and Sup. Figure 2). On surface ECG, Kir2.1C122Y mice showed conduction alterations characteristic of the disease (Figure 2A). More importantly, Kir2.1C122Y mice had frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) and runs of non-sustained PVT (Figure 2B) in agreement with the ATS1 patient’s phenotype. Under stress conditions induced by isoproterenol (ISO, 5mg/Kg), Kir2.1C122Y mice developed PR and QRS prolongation. Compared with control, Kir2.1C122Y animals exhibited repolarization abnormalities with prolongation of the QT interval and occasional overlap of the T wave with the P wave of the following complex (Figure 2C–D). Intracardiac stimulation of the right atrium or ventricle used consecutive trains of stimuli at 10 and 25 Hz. Under basal conditions, Kir2.1C122Y mice had a significantly increased arrhythmia susceptibility with respect to Kir2.1WT (Figure 2E–F); upon stimulation, 5 out of 9 Kir2.1C122Y mice (55,5%) developed atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, including PVT, compared to 0 out of 7 Kir2.1WT mice (0%). ISO administration increased arrhythmia susceptibility in both atria and ventricles of Kir2.1C122Y (8 out of 9 mice, 88,9%), vs. Kir2.1WT (1 out of 7 mice, 14,2%). Altogether, these results indicate that the Kir2.1C122Y mutation recapitulates the ATS1 patientś cardiac electrical phenotype, establishing an arrhythmogenic substrate.

Figure 2. Kir2.1C122Y mice recapitulate the ATS1 patientś phenotype and increased susceptibility to arrhythmias.

A: Representative lead-II ECG recordings from AAV-transduced Kir2.1WT (top) and Kir2.1C122Y (bottom) mice. The record shows normal sinus rhythm with prolonged PR interval in mutant animals (N= 7 animals per group). B: ECG in a Kir2.1C122Y animal showing frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) manifested as duplets. C-D: Effects of isoprenaline (ISO, 5 mg/Kg) administration on electrical conduction and QT interval in Kir2.1C122Y animals compared to basal condition (N= 7 animals per group). E: Representative lead-II ECG traces (top) and corresponding intracardiac recordings (bottom) before (SR; sinus rhythm), during and after intracardiac application of stimulus trains at 10 and 25 Hz under basal conditions. E.1, atrial stimulation in a Kir2.1WT mouse failed to induce an arrhythmia. E.2, atrial stimulation in a Kir2.1C122Y mouse induced a period atrial fibrillation. E.3, ventricular stimulation in a Kir2.1C122Y mouse induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT). F: Contingency plots of number of animals with arrhythmogenic response after intracardiac stimulation at baseline, and after treatment with ISO (5 mg/Kg). Each value is the mean ± SEM (N=7–9 animals per group). Statistical analysis by two-tailed ANOVA and Student-t test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

Kir2.1C122Y subunits are able to form heterotetramers

Kir2.1 channels can exist either as homo- or hetero-tetrameric complexes consisting of either four identical Kir2.1 subunits or in various combinations with the structurally related members of the Kir2.x subfamily of inward rectifier K+ channels29. To clarify the mechanisms by which the C122Y mutation causes channel dysfunction in ATS1, we determined whether Kir2.1C122Y can assemble with WT subunits and traffic to the surface membrane (Supplemental Figure 3). Immunoprecipitation studies using differently tagged Kir2.1 subunits were used to test whether the mutation affected subunit assembly. The HA and Myc epitope tags were incorporated into an external site that does not perturb channel activity30,31 (Supplemental Figure 3A). In these studies, HEK293T cells were either co-transfected with Myc-tagged Kir2.1 (WT) or HA-tagged Kir2.1 (WT or C122Y) at a 1:1 ratio. Recovered immunoprecipitants on anti HA-bound beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the extent of HA-tagged channel subunit interaction was assessed using anti-Myc antibodies in immunoblots. As shown by the representative experiment (Supplemental Figure 3B), the wild-type Myc-Kir2.1 co-immunoprecipitated with both HA-tagged subunits, indicating the mutation does not alter subunit interaction. In addition, immunocytochemical analysis of co-transfected cells revealed that the Myc-tagged Kir2.1WT and HA-tagged Kir2.1C122Y subunits are highly co-localized (Supplemental Figure 3C), offering further evidence that the C122Y subunits are capable of assembling with the WT subunits in cells.

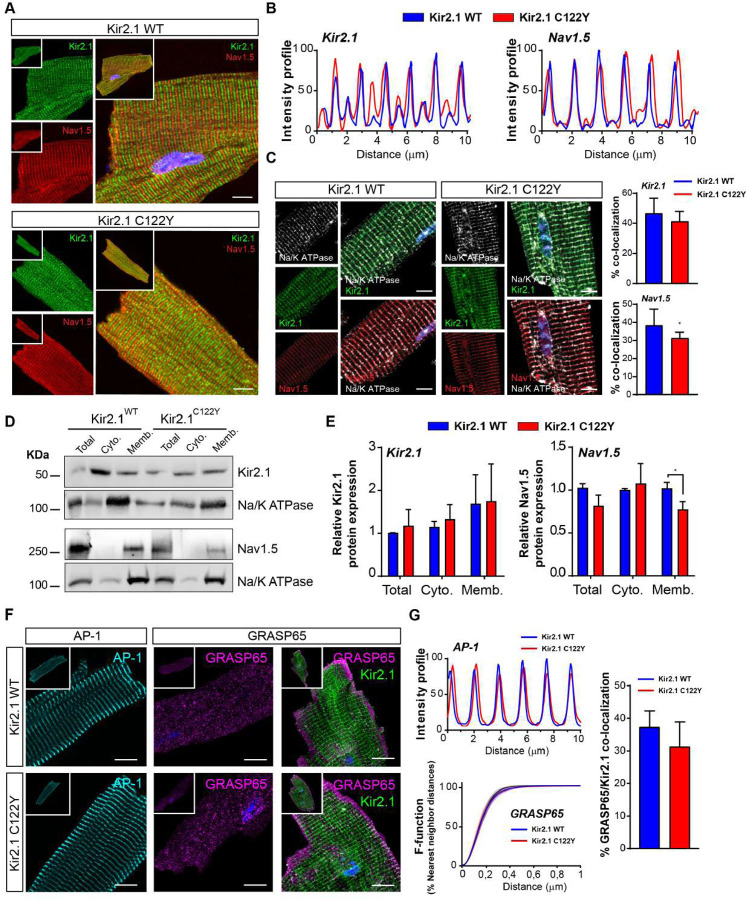

Kir2.1C122Y subunits traffic to the cardiomyocyte surface membrane

Kir2.1 localizes at two separate well-defined striated microdomains running parallel to each other at ~0.9 µm intervals throughout the cardiomyocyte.24 One microdomain corresponds with the t-tubules where Kir2.1 co-localizes with the voltage gated cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 (~1.8 µm spacing). The other is at the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) where Kir2.1 functions to control calcium homeostasis (Figure 3A and B).24 Disruption of one or both microdomains leads to malfunction of Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 channels that might trigger arrhythmias. However, unlike the defective distribution pattern that was demonstrated for the trafficking deficient mutation Kir2.1Δ314−315,24 immunolocalization and confocal image analysis of isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes from Kir2.1C122Y animals revealed an unaltered distribution pattern for both Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 channels (Figure 3A and B). When we determined the percentage of membrane expression using an anti-Na+/K+ ATPase immunostaining, the results again showed a similar distribution of Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 channels in Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y cells, with a small but significant reduction in NaV1.5 accumulation level in mutant cardiomyocytes (Figure 3C). Similarly, on western blot, NaV1.5 protein expression was lower for the mutant cardiomyocytes with a trend toward a decrease in total protein (Figure 3D–E). Trafficking of both Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 to their membrane microdomains depends in part on their classical route that involves incorporation into clathrin-coated vesicles at the trans-Golgi network marked by interaction with the adaptor protein complex-1 ϒ-adaptin subunit (AP-1).32 Trafficking may also occur via an unconventional route directly from SR in a GRASP dependent manner.33 To test whether Kir2.1C122Y disrupts Kir2.1 trafficking we analyzed AP-1 and GRASP65 proteins by immunofluorescence of both WT and mutant cardiomyocytes. As shown in Figure 3F–G, the AP-1 expression profile was identical in both groups. Similarly, GRASP65 staining presented an F-function distribution (distance from particles to nearest neighbor particle) with no differences in either WT or mutant groups. Also, co-localization of Kir2.1 with GRASP65 was similar in both groups. From the foregoing the Kir2.1C122Y variant is able to form heterotetramers with WT subunits and retains trafficking ability. Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that the C122Y mutation leads to cardiac electrical alterations via mechanisms other than those recently demonstrated for the trafficking deficient Δ314–315 mutation.36 This led us to further explore the biophysical and electrophysiological properties of the Kir2.1C122Y channel and determine whether the mutation directly alters potassium conductance and/or disrupts protein stability.

Figure 3. Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes preserve Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 protein trafficking, but both proteins are reduced at the sarcolemma.

A: Confocal images of Kir2.1 and Nav1.5 channels in Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes. Scale bar, 10μm. B: Fluorescence intensity profiles show distribution patterns for both Kir2.1 (left panel) and NaV1.5 (right panel) channels in WT and Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes. Note double banding for Kir2.1 indicating SR expression.24 C: Representative immunofluorescence images show co-localization of Kir2.1 (green) and NaV1.5 (red) with Na+/K+ ATPase (white) at the sarcolemma. Graphs show percentage of co-localization with significantly reduced NaV1.5 (* p<0.05; t test). Scale bar, 10μm D: Western blots comparing cytosolic and sarcolemmal Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 in Kir2.1WT vs Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes. Data were normalized using Na+/K+ ATPase. E: Graphs show western blot quantification of cytosolic and sarcolemmal Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 channels. Note reduced NaV1.5 at the sarcolemma (N=4–5 animals per group) (* p<0.05; two-tailed ANOVA). F: Confocal images of classical (AP-1) and unconventional (GRASP65) trafficking routes for Kir2.1 and NaV1.5. Scale bar, 10μm. G: Quantification of fluorescence intensity profiles for AP-1, F-function (% nearest neighbour distances) and percentage of GRASP co-localization in isolated Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes. (N=3 animals per group; n=7–9 cells). (* p<0.05; two-tailed ANOVA). Scale bar, 10μm. Each value is the mean ± SEM.

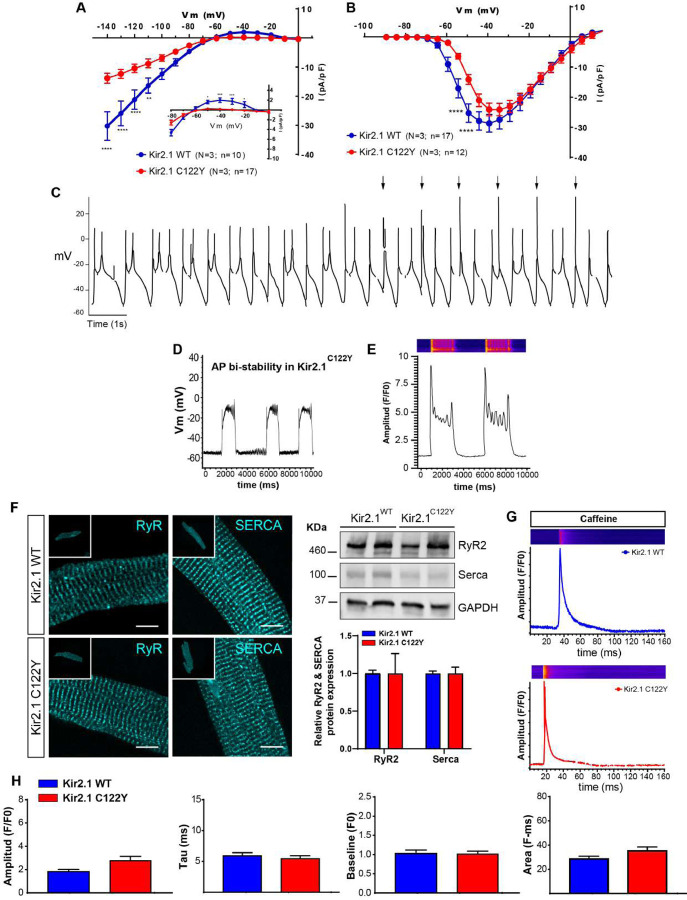

Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes exhibit defects in excitability and action potential duration

We performed patch-clamping experiments in isolated cardiomyocytes from Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y expressing hearts. We focused on both IK1 and the sodium inward current (INa) to test whether the impulse conduction disturbances and arrhythmias observed in this model of ATS1 are due to defects in one or both currents. The results show a 90% reduction in the outward IK1 density of Kir2.1C122Y compared with Kir2.1WTcardiomyocytes (Figure 4A), which explains why we were unable to obtain reliable current clamp measurements of AP characteristics, since the vast majority of Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes (11 out of 12 or 91.7%) tested were substantially depolarized at rest (~−35mV) and unable to generate APs upon stimulation. Furthermore, surprisingly, Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes showed a slight but significant decrease in INa density compared with controls (Figure 4B) with no significant changes in the voltage-dependence of current activation or inactivation (Supplemental Figure 4). These data further demonstrate that, while the mutant Kir2.1 protein traffics and is expressed at the membrane, it is dysfunctional and also reduces NaV1.5 function. Altogether, these results reinforce the hypothesis that conduction disturbances and arrhythmias in ATS1 patients are due to a defect in cardiomyocyte excitability.

Figure 4. Kir2.1C122Y alters electrophysiology in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes.

A: Superimposed IK1 current-voltage (IV) relationships for Kir2.1WT (blue) and Kir2.1C122Y (red) cardiomyocytes. B: Superimposed INa IV relationships for Kir2.1WT (blue) and Kir2.1C122Y (red) cardiomyocytes. C: Representative action potential time series recorded during current-clamping in an isolated Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocyte. Note spontaneous action potentials with excessively long APD generating early afterdepolarizations (EADs) and triggered activity. D: Membrane potential bi-stability in a Kir2.1C122Y mutant with EADs appearing above −20 mV. Graph shows quantification of bi-stability events in a Kir2.1C122Ycardiomyocyte. E: Representative confocal image and profile of calcium transient dynamics in another isolated Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocyte. Note amplitude bi-stability and large numbers of spontaneous calcium release events spreading throughout the cell. F: Left, Immunolocalization of ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) in AAV-transduced ventricular cardiomyocytes from Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y mice. Scale bar, 10μm (N=3 animals per group; n=7–8 cells). Right, western blots showing similar amounts of total protein for both (N=4 animals per group). G: Representative fluorescence profiles of caffeine-induce calcium release in Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes. H: Graphs show amplitude, Tau (Decay kinetics) and Baseline of each Ca2+ transient, as well as the total area) (N=3 animals per group; n=10–17 cells). Each value is represented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted using two-tailed ANOVA. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001.

As illustrated in Figure 4C, AP recordings revealed that, the 7 out of 12 (58,3%) Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes that remained excitable after isolation generated significantly prolonged APs, early afterdepolarizations (EADs), triggered discharges and bi-stability of the RMP (Figure 4D). Accordingly, we analyzed the intracellular calcium dynamics in both WT and ATS1 mice. Confocal images of Ca2+ dynamics showed that Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes had an excitation-contraction (e-c) coupling defect with multiple abnormal spontaneous calcium release events during systole and diastole (Figure 4E). Since Ca2+ movements across the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) are controlled by the ryanodine receptor (RyR2)-mediated Ca2+ release and the Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)-mediated Ca2+ reuptake to-and-from the cytosol and SR lumen, we wondered whether protein alteration could happen in the Kir2.1C122Y mouse model. However, confocal images of protein localization profiles were identical in Kir2.1C122Y and Kir2.1WT cardiomyocytes, and total protein levels were also similar (Figure 4F). Since, K+ flux across Kir2.1 SR channels contributes countercurrent to Ca2+ movement, 24 we analyzed the intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in both controls and ATS1 mice (Figure 4G–H). Cardiomyocytes expressing Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y showed similar Ca2+ transient decay under acute caffeine administration in intact cardiomyocytes (Figure 4G–H). These results indicate that the Ca2+ alterations are due to functional defects at the sarcolemma, including RMP depolarization and reduced excitability, rather than Kir2.1 dysfunction at the SR.

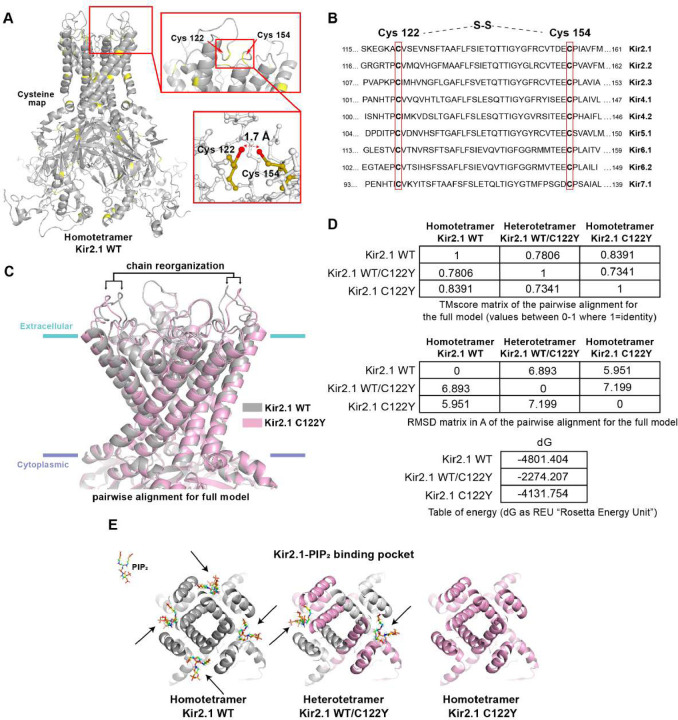

Disulfide bond loss reorganizes tridimensional channel structure interfering with Kir2.1C122Y-PIP2 binding

Cys122 localizes at the extracellular loop of the Kir2.1 channel, immediately after the first transmembrane domain, where it is cross-linked by an intramolecular disulfide bond with Cys154 at the beginning of the second transmembrane α-helix (Figure 5A). Both residues and their disulfide bond are conserved across the Kir family (Figure 5B), which is crucial for proper channel folding, as they may help accommodate the extracellular loop in an optimal tridimensional structure.18 We used in-silico homology modelling to derive predictions of the molecular structure of the Kir2.1C122Y mutant channel, and thus understand the possible mechanisms underlying its dysfunction. Atomic level modelling showed that, compared to the WT channel, Kir2.1C122Y undergoes a clear reorganization (TMscore 0.73; RDMS: ~6Å for homotetramer or TMscore 0.78; RDMS: ~7Å for heterotetramer) (Figure 5C–D). The Gibbs free-energy values for Kir2.1C122Y were more positive compared to WT (WT: 4801.404 vs C122Y: −4131.754 for homo or −2274.207 for heterotetramer) (Figure 5D). This indicates a more unstable state in Kir2.1C122Y homo- and heterotetrameric channels, suggesting that the incorporation of mutant subunit could affect the integrity of the WT monomers or even affect the macromolecular channelosome complex, including Kir2.1 and NaV1.5.

Figure 5. The C122Y mutation alters Kir2.1 channel conformation and PIP2 binding.

A: Topological scheme of Kir2.1 homotetramer channel indicating cysteine positions (yellow). B: Amino acid sequence in Kir family indicating highly conserved extracellular disulfide bond. Cys122 and Cys154 are indicated in Kir2.1 C: Pairwise alignment for full model (Grey, Kir2.1WT; pink, Kir2.1C122Y). D: Upper panel, TMscore matrix of the pairwise alignment for the full model. Values between 0–1, where 1 is the identity. RMSD matrix (middle panel) in angstroms (Å). Lower panel, Table of Gibbs free-energy values (dG) of WT and mutant homo- and heterotetramer. E: Docking modelling of Kir2.1-PiP2 interaction in Kir2.1WT, homo- and heterotetramers of Kir2.1C122Y(see text for detailed explanation of each panel).

To predict Kir2.1-PIP2 interaction ability we incorporated PIP2 molecules in the simulation. Our results showed an altered Kir2.1C122Y-PIP2 interaction following a dominant-negative pattern. The Kir2.1WT/C122Y heterotetramer presented 2 out of 4 PIP2 molecules compared with the complete set of 4 PIP2 in the Kir2.1WT homotetramer, one per monomer (Figure 5E). Notably, the Kir2.1C122Y homotetramer abolished completely PIP2 interaction, in accordance with the IK1 current suppression in homozygous mutant conditions in C154F34 and C122Y-expressing HEK cells (Supplemental Figure 5). Taken together, these in-silico homology experiments predict that the loss of the highly-conserved extracellular Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bond in channels containing the Kir2.1C122Y isoform may result in a clear atomic re-structuration with loss of function by mechanisms that include, at least in part, a pronounced interference with the PIP2 binding pocket.

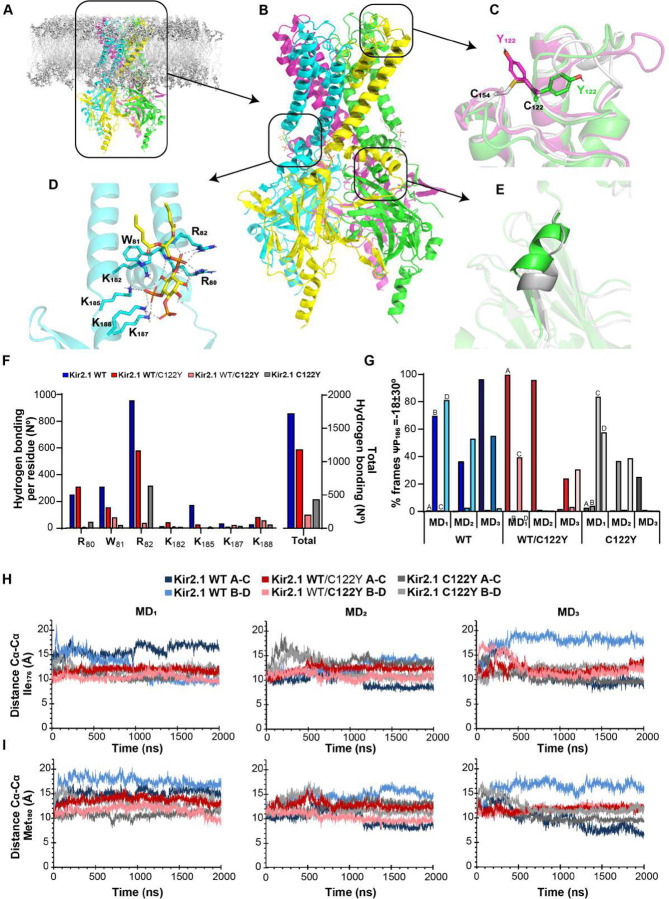

Cys122- Cys154 disulfide bond breakup disrupts Kir2.1-PiP2 interaction dynamics.

We conducted in-silico molecular dynamics (MD) studies to more rigorously establish whether the extracellular Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bond breakup in the Kir2.1C122Y mutant channel disrupts Kir2.1-PIP2 interaction (Figure 6). We generated Kir2.1 homology models bound to a single PIP2 molecule per monomer in Kir2.1WT, Kir2.1C122Y homotetramer and Kir2.1WT/C122Y heterotetramer to study Kir2.1-PIP2 interactions throughout an individual 2000 ns MD replica (see Supplemental Methods for details of the overall approach). For each monomer we used the pre-opened state of Kir2.2 bound to PIP2 as a template (PDB code 3SPH).35 The CHARMM-GUI server allowed us to simulate both membrane and environment (Figure 6A–B); we then performed three independent replicas for each model. First, we evaluated the conformational changes in the extracellular space by monitoring either C122 or Y122 backbone dihedral angles along the 2000 ns MD. Comparative analysis showed only 28% conserved-frames in backbone dihedral angles, while 72% presented a shift in Φ-dihedral angle from around −70° to −140° shortly after the first 100 ns (Figure 6C and Supplemental Figure 6). The Y122 sidechain reorientation resulted in movement of D112, and consequent break of the internal hydrogen-bonding network between D112 and the H110 sidechain and the NH backbone of C122 within the extracellular loop (Supplemental Figure 7). Thus, hydrogen bonds between the H110 sidechain and the Y122 backbone were either absent or generally present in less than 50% of the frames. In addition, in several of the MD simulations a new hydrogen bond was formed between D112 and K117. Therefore, C122Y leads to a reorganization of the hydrogen-bonding network of the extracellular loop that might alter Kir2.1 function. (Supplemental Table 2). Nevertheless, neither of the two Y122 conformations observed in the MD led to a significant change in the relative disposition of the outer and inner helices, as shown by the measurement of the distance between two opposite residues (I106 and I156) located near the extracellular side of each of those helices (Supplemental Figure 8).

Figure 6. Extracellular disulfide bond break reduces PiP2-dependent Kir2.1 regulation.

A: Schematic representation of Kir2.1 tetramer embedded in a bilipid layer. B: Structure of Kir tetramer. Monomers are represented in different colors. C: Illustrative C122 or Y122 sidechain orientation. Superposition of Kir2.1WT (grey) and two representative Kir2.1C122Y monomers (in green the most frequent Y122 orientation, in purple, the minor one). D: Representative illustration of hydrogen bond network between Kir2.2 and PIP2. Same hydrogen bondings as in the generated homology model were tested for Kir2.1. E: Evolution of the C-linker during the MD: from a helix (green) to a less structured linker, as shown by a representative 2000 ns snapshot (grey). F: Histogram representing the average number of PIP2-Kir2.1 hydrogen bonds per residue along the 2000 ns simulation, for Kir2.1WT (blue), Kir2.1WT/C122Y (grey) and Kir2.1WT/C122Y (red). These values are the average of the three replicas and the four chains for each tetramer. G: Histogram representing the percentage of frames in which the ψ dihedral angle of the Pro186 is within those expected for a 310 helix (ψ =−18±30°). For Kir2.1WT/C122Y, A and C represent the non-mutated monomers. H: I176 and M180 Cα-Cα distances between two opposite monomers along the 2000 ns MD. Color code on top. N=3 replicates.

Kir2.1-PIP2 interactions involve hydrophobic contacts with PIP2 acyl chains, and more specific polar interactions between PIP2 phosphates and positively charged Kir2.1 residues at the transmembrane domain (TMD)-to-cytoplasmic domain (CTD) interface.35,36 A detailed study of the atomic Kir2.1-PIP2 hydrogen-bonding distance yielded a global loss of hydrogen bonds in the Kir2.1C122Y channels that directly affected PIP2 interactions. Comprehensive analysis of the R80W81R82 motif and the lysine-cluster K182K185K187K188 of the helicoidal CTD-to-TMD linker (C-linker) (Figure 6D) showed a clear reduction in hydrogen bonding capacity in both hetero- and homotetrameric Kir2.1C122Y channels throughout the 2000 ns MD (Figure 6F and Supplementary Table 3). Our simulations predict that, compared with the Kir2.1WT tetramers, Kir2.1WT/C122Y and Kir2.1C122Y channels progressively lose the characteristic hydrogen bond of the PIP2 1′ phosphate with R80W81R82, particularly R82, and the PIP2 4′ and 5′ phosphates with the C-linker (Supplemental Table 3). As expected, the unmutated chains (chains A and C) in Kir2.1WT/C122Y heterotetramers showed a similar behavior to WT chains (Supplemental Table 3).

Upon PIP2 binding at the interface between TMD and CTD, the C-linker undergoes a disorder-to-order transition bringing both domains closer together. Thus, the G-loop wedges into the TMD causing the inner helix gate to open.35 Follow-up of this transition showed that the C-linker loses the hydrogen bonds characteristic of α-helix structures in the Kir2.1C122Y hetero- and homotetramer. In comparison, Kir2.1WT maintained a more pronounced hydrogen-bond network between K188-E191 and R189-T192, as well as the K185, P186, K187 and N190 residues, indicating that in the mutant channels the N- and C-terminal of the C-linker helix were destructured faster than WT (Figure 6E and Supplemental Table 4). Interestingly, at the beginning of the C-linker motif, the dihedral angles of P186 were within those of 310 helix φ (−71) and ψ (−18) in the PIP2-bound Kir2.1WT structures. However, in the Kir2.1C122Y hetero- and homotetramer the φ dihedral varied in correlation with a progressive loss of the C-linkeŕs helical character (Figure 6G). Compared with Kir2.1WT, the Kir2.1C122Y homotetramer had a lower percentage of frames corresponding to the dihedral 310 helix in P186 (Kir2.1C122Y: 17% at 1000 ns, 8% at 2000 ns; Kir2.1WT: 33% at 1000 ns, 17% at 2000 ns), the percentages of the heterotetramer being intermediate (Figure 6G).

Finally, we measured the distance between Cα carbons of representative pore constriction Ile176 and Met180 residues at the TM and A306 of the G-loop from opposite chains to study the pore opening state during the 2000 ns MD (Figure 6H and Supplemental Figure 8)36,37. For both Ile176 and Met180 the distance between the A-B and between the B-D chains decreased progressively in hetero and more pronouncedly in homo mutant channels, with larger values for WT chains in the first 500 ns, which likely correlated with a more open state in WT channels (Figure 6I). Longer MD times using WT channels showed that the distance among the Cα carbons of the above residues decreased in two opposite monomers and led to an increase in the distance between the other two monomers, as observed in the gating mechanism for KirBac3.1.38 Similarly, the Cα-carbon distance between A306 residues in the G-loop decreased in the mutant hetero- and more pronouncedly in the homotetramer (Supplemental Figure 9). These results strongly suggest that the extracellular disulfide bond break of Kir2.1C122Y closes the channel by altering the Kir2.1-PIP2 hydrogen-bond network, which in the WT stabilizes PIP2 function to maintain the open state of the channel.

Kir2.1C122Y has a reduced sensitivity to, and binding capacity for PIP2

To test for PIP2 binding to Kir2.1, we fused a nanoluciferase (Nluc) to the C-terminus of the channel and used a soluble fluorescent PIP2 (FL-PIP2) analog suitable for binding to Kir2.1.25 Activation of Nluc produced a FL-PIP2-dependent bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) signal specific for Kir2.1 as shown by the cartoon of the assay design in Figure 7A. HEK293T cells were transfected with the WT and C122Y mutant version, respectively, and a bioluminescence assay was performed. We included another Kir2.1 mutant version with a known mutation interfering with PIP2-Kir2.1 channel interaction as a negative control (Kir2.1R218W). Our results showed that PIP2 binds with high affinity to Kir2.1WT but, as expected cannot directly bind to Kir2.1C122Y, such as we observed for Kir2.1R218W (Figure 7B). To test the sensitivity of Kir2.1 to PIP2, we performed inside-out patch-clamping of the Kir2.1WT and the heterozygous condition Kir2.1WT/C122Y currents in co-transfected HEK293T cells at a 1:1 ratio. We recorded IK1 in both basal condition and under increasing concentrations of PIP2 (25 and 50 μg/ml PIP2). The results showed that while in Kir2.1WT, PIP2 increased the inward K+ current in a dose-dependent manner, the Kir2.1WT/C122Y mutation blunted the sensitivity to PIP2 (Figure 7C–D). Both groups showed an unaltered outward current. Taken together, these results confirm the inability of Kir2.1C122Y channels to functionally interact with PIP2 molecules that allow proper channel function, according to the dominant negative effect expected from patient data.

Figure 7. The C122Y mutation reduces Kir2.1-PIP2 binding capacity and interaction.

A: Diagram of Kir2.1 monomer fused to the bioluminescent protein nanoluciferase (Nluc) (adapted from Cabanos et al.25). B: Specific BRET signal of binding Fl-PIP2 to Kir2.1 WT, C122Y and R218W and competition with non-fluorescent PIP2 version. Reduced binding was observed for C122Y and R218W (N=3 replicates per group; n=8–10 wells). C: Representative inside-out recording of IK1 in the absence (black current) and the presence of 25 (blue) and 50 (purple) μg/ml of PiP2. D: Normalized peak currents (I/I0) from −30 to +10 mV show that heterozygous condition abolishes the response to increasing PIP2 concentration. In contrast, in Kir2.1WT-transfected cells inward current increased progressively with PIP2. Both groups maintained an unaltered outward IK1. (n=7). Statistical analyses were conducted using two-tailed ANOVA. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001

Discussion

We report on the first human ATS1 mutation, C122Y, that breaks the Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide bond in the extracellular domain of the tridimensional Kir2.1 structure. The disruption leads to defects in PIP2-dependent regulation, exerting a dominant negative effect with Kir2.1 tetramer channel dysfunction and life-threatening arrhythmias. Our AAV-mediated mouse model recapitulates in-vivo the ECG phenotype of the ATS1 patient carrying the C122Y mutation. ISO administration led to progressive further prolongation in the PR, QRS, and QT intervals. In addition, the mutation increases susceptibility to pacing-induced arrhythmogenic events of high severity (>1 second) in Kir2.1C122Y animals relative to controls, including non-sustained ventricular tachycardias similar to those observed on the probandś ECG. Isolated cardiomyocytes from Kir2.1C122Y mice exhibited defects produced by decreased IK1 and INa compared to controls, including a a significantly depolarized RMP and reduced excitability. They also displayed prolonged APD, and in many cases EADs, bi-stability of the RMP and spontaneous calcium release events. The bistable resting membrane potential shown by some of the Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes may have been in part be due to the modification of the overall IK1 IV relation shape produced by the mutation. As demonstrated many years ago by Gadsby and Cranefield (1977) in Purkinje fibers, the existence of two possible stable resting potentials requires that the net steady-state IV relationship be “N-shaped,” with two zero-current intercepts in regions of positive slope conductance.39 A third unstable intercept occurs in a region of negative slope conductance. In the case of the Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocyte, the reduced Kir2.1 outward current at voltages between −60 and 0 mV, counterbalanced by the inward background conductance carried predominantly by sodium and calcium ions, generated an N-shaped current-voltage relation that crossed the voltage axis three times allowing two levels of resting membrane potential. Altogether, our results provide a potential mechanism for the spontaneous and induced arrhythmias observed in our ATS1 mouse model. While at baseline Ca2+ dynamics were similar to control after caffeine administration, ISO increased arrhythmia inducibility, suggesting abnormal Ca2+ dynamics transients.24.

Our in-silico homology modelling of the tridimensional Kir2.1 structure helps us understand the structural mechanisms underlying Kir2.1C122Y dysfunction. Loss of the extracellular disulfide bond clearly alters the tridimensional structure and disrupts channel activity despite apparently normal Kir2.1C122Y channel trafficking to the sarcolemma. However, despite channel reorganization, Kir2.1C122Y still maintains a 78–84% similarity with Kir2.1WT (TMscore: mutant heterotetramer: 0.7806 vs mutant homotetramer: 0.8391), which suggests a failure of Kir2.1C122Y interaction with one or more key regulatory elements required for proper channel function. PIP2 signaling is a top candidate. PIP2 has emerged as a central subcellular mechanism for controlling ion channels and the excitability of nerves and cardiac muscle.40 PIP2 acts as a cofactor for proper Kir2.1 activity at the cell membrane. Kir2.1 channel-PIP2 interactions are crucial for channel activity and regulation, and defects in PIP2 binding constitute a major mechanism of Kir2.1 dysfunction underlying the loss-of-function in several ATS1.9

Our MD simulations with a single PIP2 molecule bound per monomer during 2000 ns MD replicas revealed that the mutation increased the probability of change in the Y122 Φ-dihedral angle leading to an altered hydrogen bond network in the extracellular loop. However, regardless of whether or not the dihedral angle varied, the distance between inner and outer helices remained unchanged. Nonetheless, the mutation triggered structural changes, particularly at the C-linker, which directly modified the PIP2 binding site comprising amino acids from two main structural regions of the channel. According to the Kir2.2 channel X-ray crystal structure (PDB code 3SPH), the 1′ PIP2 phosphate interacts with amino acids forming the sequence RWR (R80W81R82). This sequence is conserved (as RWR or KWR) among many different Kir channels and is located at the N-terminus of the outer helix.35 The RWR motif forms a binding site in which the 1′ phosphate caps the helix and is cradled by main-chain amide nitrogen atoms and the guanidinium groups of the two arginine residues. The tryptophan (W80) residue appears to anchor to the end of the outer helix at the membrane interface and also interact with one of the acyl chains. Similarly, 4’ and 5’ PiP2 phosphates interact and form hydrogen bonds with the helicoidal internal sliding helix (C-linker) at the end of the TM2 K183, K186, K188 and K189 residues in Kir2.2.35 Throughout the 2000 ns MD, hydrogen bonds between Kir2.1 and PIP2 decreased more rapidly for mutant channels compared to Kir2.1WT. Specifically, the PIP2 1′ phosphate cap lost its interaction with the R80W81R82 triad, particularly R82, which appears strongly bound to WT monomers for longer simulation time (Supplemental Table 2).

PIP2 binding is known to induce a large conformational change in Kir channels leading to the formation of two new helices, an N-terminal extension of the ‘interfacial’ helix and a ‘tether’ helix at the C-linker.35,36 The flexible expansion of the C-linker contracts to a compact helical structure involving translation of the CTD ~6Å towards the TMD, where it remains anchored and allows opening of the inner gate of the helix.35,36,45–47 Importantly, separation between helices comes about as a result of slight splaying, but more significantly rotation of the inner helices, which moves hydrophobic amino acid side chains away from the ion pathway.35 Our MD simulation showed the C-linker disorganizing faster in Kir2.1C122Y homo- and heterotetramer during the 2000 ns MD compared to WT channels, according to the loss of dihedral angles of P186 within those of the 310-helix structure. These results highlight a rapid release of PIP2 molecules leading to channel closure, in accordance with the decreases in the Cα-Cα distance observed in the pore constriction residues Ile176, Met180 and A306, which also appeared barely dynamic over 2000 ns MD. In agreement, other studies have shown that P186 mutations lead to channel assembly, but with significantly reduced PIP2-binding capacity.41 Taken together, these results suggest that C122Y induces a reorganization of the chains starting extracellularly and is transmitting along the channel to finally interrupts PIP2ś function. Nonetheless, the precise mechanism by which the C122Y mutation interferes with Kir2.1 binding to PIP2 molecules is beyond the scope of this study and remains to be fully elucidated.

Taking advantage of the BRET lipid binding assay, our results clearly show a significant decrease in the percentage of BRET signal in Kir2.1C122Y channels, similar to the reduction in BRET signal for Kir2.1R218W channels, with a well-known failure to interact with PIP 10 We next directly measured the functional effects of PIP on Kir2.1WT and heterozygous Kir2.1WT/C122Y channels in inside-out voltage-clamped membrane patches from transfected HEK293T cells. Altogether, the results showed that the C122Y mutation attenuated the maintenance of the Ik1 current over time with increasing PIP2 concentration, which explained the lack of PIP2-dependent IK1 current. Thus, we validated the in-silico MD predictions and the demonstration by BRET that the Kir2.1C122Y mutation breaks the disulfide bonds in the Kir2.1 extracellular domain, altering PIP2-dependent regulation to finally lead to channel dysfunction.

Interestingly, Macías et al. 24 have recently shown an SR microdomain of functional Kir2.1 channels contributing to intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis that could explain the phenotypic overlapping between ATS1 and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) in some patients.42,43 Ca2+ fluxes across the SR membrane are bidirectional, and need a charge-compensating countercurrent ensuring that the SR membrane potential remains near 0 mV during the e-c coupling process.44,45 Importantly, our results demonstrate that intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis was similar in WT and C122Y under acute caffeine administration in intact isolated cardiomyocytes, suggesting that the SR Kir2.1 channel population is not regulated in a PIP2-dependent manner. However, a role for intracellular Ca2+ in arrhythmogenesis provoked by Kir2.1C122Y was evidenced only after overloading the SR by ISO administration. The results suggest that while sarcolemmal Kir2.1C122Y channels fail to conduct potassium through PIP2-dependent mechanisms, SR Kir2.1C122Y channels remain functional independently of PIP2 activity. In support of such an idea, Katan et al. demonstrated that PiP2 is exclusively involved in sarcolemmal activities, including controlling Kir2.1 function.46

Kir2.1 channels are part of large multiprotein complexes comprising components of the cytoskeleton, regulatory kinases and phosphatases, trafficking proteins, extracellular matrix proteins, and even other ion channels.47–49 This probably explains in part the wide variety of clinical phenotypes found in different families with the same mutation and even within the same family.3 Kir2.1 forms channelosomes with NaV1.5, which indicates that the disease should no longer be considered in the simplistic terms of “monogenic” disorder.2 In fact, as our results show, it would not be correct to assume that the arrhythmic phenotype manifested by the patient is directly due to the mutation in question, but we must also consider potential modifications on the channeĺs interacting proteins. Therefore, the paradigm-shifting premise of this work is that we can no longer consider inherited arrhythmogenic diseases in terms of dysregulation of a single protein, because alteration of any member of a particular multiprotein complex has the potential to modify the function of associated proteins, resulting in a more complex disease. In this sense, the phenotypic manifestations in ATS1 are only understood by considering the wide range of proteins with which the altered ion channels interact.49 Our results show that Kir2.1C122Y not only reduces IK1 but also INa in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes carrying the mutation. However, the C122Y mutation does not affect trafficking of ether Kir2.1 or NaV1.5 to the sarcolemma, suggesting new regulatory pathways for channelosome function. To further analyze molecular mechanisms involving NaV1.5 regulation, we studied channelosome homeostasis of both Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 proteins due to the differences in Gibbs free-energy values (WT: 4801.404 vs C122Y: −4131.754 for homo or −2274.207 for heterotetramer). Cardiomyocytes were treated with cycloheximide (CHX)50, a ribosomal RNA transcription inhibitor, for periods of 8, 16 and 24 hours at final concentrations of 100 µg/ml (Supplemental Figure 10). Interruption of protein synthesis resulted in a decrease of total Kir2.1 protein after 24 hours treatment compared to control (Supplemental Figure 10A). Immunostaining showed a significant co-localization with Rab5, protein involved in early endosomal formation (Supplemental Figure 10B), suggesting protein instability. Similarly, CHX decreased total NaV1.5 protein after 8 hours confirming the reduction in cell surface expression (Supplemental Figure 10C). However, regulation of NaV1.5 in these patients remains unclear. Reductions in NaV1.5 function/expression provide a slow-conduction substrate for cardiac arrhythmias. Van Bemmelen et al. demonstrate that NaV1.5 can be ubiquitinated in heart tissues and that the ubiquitin-protein ligase Nedd4-2 acts on NaV1.5 by decreasing the channel density at the cell surface51. Furthermore, in conditions like heart failure, elevated [Ca2+]i increased Nedd4-2, interaction between Nedd4-2 and Nav1.5, and NaV1.5 ubiquitination with consequent degradation52, suggesting a crucial role of Nedd4-2 in NaV1.5 downregulation in heart disease. We looked for the expression in Nedd4-2 and our results showed a similar total expression of Nedd4-2 in both Kir2.1WT and Kir2.1C122Y cardiomyocytes, indicating that other regulatory pathways control the expression of NaV1.5 at the cell surface membrane as a consequence of the Kir2.1C122Y mutation (Supplemental Figure 10D). Further studies are needed to elucidate the regulation of the NaV1.5 channel associated with the Kir2.1C122Y mutation, but our data suggest a complex mechanism involved in channelosome function.

The potential clinical impact of this novel paradigm is groundbreaking: understanding the Kir2.1 modulation by its multiple interacting molecules will significantly improve our knowledge of channel function and of inherited and acquired arrhythmogenic cardiac diseases. It should also lay the groundwork for the generation of innovative, effective and safe approaches to prevent SCD in these and other devastating cardiac disease. Compared Together with previous data,24 all the results shown here support the hypothesis that the molecular mechanisms that increase the susceptibility to arrhythmias and SCD in ATS1 are different depending on the specific mutation, so that pharmacological treatment and clinical management should be different for each patient.

In conclusion, using AAV-mediated gene transfer we have generated a mouse model that recapitulated the electrocardiographic ATS1 phenotype of probands. ISO administration prolonged the PR, QRS and QT duration, and increased susceptibility to arrhythmogenic events of high severity. In-silico MD studies showed that the loss of the extracellular disulfide bond leads to channel closure by altering the Kir2.1- PIP2 hydrogen-bonding network. BRET and inside-out patch-clamping experiments confirmed the low ability of the Kir2.1C122Y to properly bind PIP2 in sarcolemma. Altogether, this is the first demonstration that the break disulfide bond in the extracellular domain of the Kir2.1 channel results in defects in PIP2-dependent regulation, leading to channel dysfunction and life-threatening arrhythmias.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE

What is known?

Andersen-Tawil Syndrome Type 1 (ATS1) is a rare arrhythmogenic disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in KCNJ2, the gene encoding the strong inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.1 responsible for IK1.

Extracellular Cys122 and Cys154 form an intramolecular disulfide bond that is essential for proper Kir2.1 channel folding but not considered vital for channel function.

Replacement of Cys122 or Cys154 residues in the Kir2.1 channel with either alanine or serine abolished ionic current in Xenopus laevis oocytes.

What new information does this article contribute?

We generated a mouse model that recapitulates the main cardiac electrical abnormalities of ATS1 patients carrying the C122Y mutation, including prolonged QT interval and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.

We demonstrate for the first time that a single residue mutation causing a break in the extracellular Cys122-to-Cys154 disulfide-bond leads to Kir2.1 channel dysfunction and arrhythmias in part by reorganizing the overall Kir2.1 channel structure, disrupting PIP2-dependent Kir2.1 channel function and destabilizing the open state of the channel.

Defects in Kir2.1 energetic stability alter the functional expression of the voltage-gated cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5, one of the main Kir2.1 interactors in the macromolecular channelosome complex, contributing to the arrhythmias.

The data support the idea that susceptibility to arrhythmias and SCD in ATS1 are specific to the type and location of the mutation, so that clinical management should be different for each patient.

Altogether, the results may lead to the identification of new molecular targets in the future design of drugs to treat a human disease that currently has no defined therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the CNIC Viral Vectors Unit for producing the AAV9. The confocal experiments were carried out in the CNIC Microscopy and Dynamic Imaging Unit. We thank the CNIC Bioinformatics Unit for generating the in-silico homology modelling simulations, F-function analysis and helping in their discussion. We also thank the Centro de Supercomputación de Galicia (CESGA) for use of the Finis Terrae III supercomputer to perform molecular dynamics studies.

Funding Statement

Supported by National Institutes of Health R01 HL163943; La Caixa Banking Foundation under the project code LCF/PR/HR19/52160013; grant PI20 / 01220 of the public call “Proyectos de Investigación en Salud 2020” (PI-FIS-2020) funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII); MCIU grant BFU2016-75144-R and PID2020-116935RB-I00, and co-funded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); and Fundación La Marató de TV3 (736/C/2020): and CIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain. We also receive support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement GA-965286; to JJ; Grant PID2021-126423OB-C22 (to MMM) funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe”; Grant PID2019-104366RB-C22 (to MGR), funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033; Funding provided by the Dynamic Microscopy and Imaging Unit - ICTS-ReDib Grant ICTS-2018-04-CNIC-16 funded by MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF; project EQC2018-005070-P funded by MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER. CNIC is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN) and the Pro CNIC Foundation, and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (grant CEX2020-001041-S funded by MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). AIM-M holds a FPU contract (FPU20/01569) from Ministerio de Universidades. LKG holds a FPI contract (PRE2018-083530), Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de España co-funded by Fondo Social Europeo ‘El Fondo Social Europeo invierte en tu futuro’, attached to Project SEV-2015-0505-18-2. IMC holds a PFIS contract (FI21/00243) funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III and Fondo Social Europeo Plus (FSE+), ‘co-funded by the European Union’. MLVP held contract PEJD-2019-PRE/BMD-15982 funded by Consejería de Educación e Investigación de la Comunidad de Madrid y Fondo Social Europeo ‘El FSE invierte en tu futuro’.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Extended Materials and Methods

Supplementary Figures 1–10

Supplementary Tables 1–4

References

- 1.Tawil R. et al. Andersen’s syndrome: potassium-sensitive periodic paralysis, ventricular ectopy, and dysmorphic features. Ann Neurol 35, 326–330 (1994). https://doi.org: 10.1002/ana.410350313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tristani-Firouzi M. et al. Functional and clinical characterization of KCNJ2 mutations associated with LQT7 (Andersen syndrome). J Clin Invest 110, 381–388 (2002). https://doi.org: 10.1172/JCI15183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaster N. M. et al. Mutations in Kir2.1 cause the developmental and episodic electrical phenotypes of Andersen’s syndrome. Cell 105, 511–519 (2001). https://doi.org:S0092-8674(01)00342-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon G. et al. Andersen-Tawil syndrome: prospective cohort analysis and expansion of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 140, 312–321 (2006). https://doi.org: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manuel A. I. M. et al. Molecular stratification of arrhythmogenic mechanisms in the Andersen Tawil Syndrome. Cardiovasc Res (2022). https://doi.org: 10.1093/cvr/cvac118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panama B. K., McLerie M. & Lopatin A. N. Heterogeneity of IK1 in the mouse heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293, H3558–3567 (2007). https://doi.org: 10.1152/ajpheart.00419.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhamoon A. S. & Jalife J. The inward rectifier current (IK1) controls cardiac excitability and is involved in arrhythmogenesis. Heart Rhythm 2, 316–324 (2005). https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pegan S., Arrabit C., Slesinger P. A. & Choe S. Andersen’s syndrome mutation effects on the structure and assembly of the cytoplasmic domains of Kir2.1. Biochemistry 45, 8599–8606 (2006). https://doi.org: 10.1021/bi060653d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handklo-Jamal R. et al. Andersen-Tawil Syndrome Is Associated With Impaired PIP2 Regulation of the Potassium Channel Kir2.1. Front Pharmacol 11, 672 (2020). https://doi.org: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes C. M. et al. Alterations in conserved Kir channel-PIP2 interactions underlie channelopathies. Neuron 34, 933–944 (2002). https://doi.org: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00725-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaldson M. R. et al. PIP2 binding residues of Kir2.1 are common targets of mutations causing Andersen syndrome. Neurology 60, 1811–1816 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho H. C., Tsushima R. G., Nguyen T. T., Guy H. R. & Backx P. H. Two critical cysteine residues implicated in disulfide bond formation and proper folding of Kir2.1. Biochemistry 39, 4649–4657 (2000). https://doi.org: 10.1021/bi992469g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marino S. M. & Gladyshev V. N. Analysis and functional prediction of reactive cysteine residues. J Biol Chem 287, 4419–4425 (2012). https://doi.org: 10.1074/jbc.R111.275578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garneau L., Klein H., Parent L. & Sauve R. Contribution of cytosolic cysteine residues to the gating properties of the Kir2.1 inward rectifier. Biophys J 84, 3717–3729 (2003). https://doi.org: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75100-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez R. et al. Structural basis of drugs that increase cardiac inward rectifier Kir2.1 currents. Cardiovasc Res 104, 337–346 (2014). https://doi.org: 10.1093/cvr/cvu203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caballero R. et al. Flecainide increases Kir2.1 currents by interacting with cysteine 311, decreasing the polyamine-induced rectification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 15631–15636 (2010). https://doi.org: 10.1073/pnas.1004021107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bannister J. P., Young B. A., Sivaprasadarao A. & Wray D. Conserved extracellular cysteine residues in the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir2.3 are required for function but not expression in the membrane. FEBS Lett 458, 393–399 (1999). https://doi.org: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01096-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyland M. L., Dart C., Spencer P. J., Sutcliffe M. J. & Stanfield P. R. The possible role of a disulphide bond in forming functional Kir2.1 potassium channels. Pflugers Arch 438, 778–781 (1999). https://doi.org: 10.1007/s004249900153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes C. A. H. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy unveils unique structural features of the human Kir2.1 channel. Sci Adv 8, eabq8489 (2022). https://doi.org: 10.1126/sciadv.abq8489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao X., Li J. & Samulski R. J. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J Virol 72, 2224–2232 (1998). https://doi.org: 10.1128/JVI.72.3.2224-2232.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauswirth W. W., Lewin A. S., Zolotukhin S. & Muzyczka N. Production and purification of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Methods Enzymol 316, 743–761 (2000). https://doi.org: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)16760-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz F. M. et al. Exercise triggers ARVC phenotype in mice expressing a disease-causing mutated version of human plakophilin-2. J Am Coll Cardiol 65, 1438–1450 (2015). https://doi.org:S0735-1097(15)00445-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao Y. et al. Scn2b Deletion in Mice Results in Ventricular and Atrial Arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 9 (2016). https://doi.org: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.003923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macías Á. et al. Kir2.1 dysfunction at the sarcolemma and the sarcoplasmic reticulum causes arrhythmias in a mouse model of Andersen–Tawil syndrome type 1. Nature Cardiovascular Research (2022). https://doi.org: 10.1038/s44161-022-00145-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabanos C., Wang M., Han X. & Hansen S. B. A Soluble Fluorescent Binding Assay Reveals PIP2 Antagonism of TREK-1 Channels. Cell Rep 20, 1287–1294 (2017). https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semenov I. et al. Excitation and injury of adult ventricular cardiomyocytes by nano- to millisecond electric shocks. Sci Rep 8, 8233 (2018). https://doi.org: 10.1038/s41598-018-26521-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brette F., Despa S., Bers D. M. & Orchard C. H. Spatiotemporal characteristics of SR Ca(2+) uptake and release in detubulated rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 39, 804–812 (2005). https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macias A. et al. Paclitaxel mitigates structural alterations and cardiac conduction system defects in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Cardiovasc Res (2021). https://doi.org: 10.1093/cvr/cvab055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schram G., Melnyk P., Pourrier M., Wang Z. & Nattel S. Kir2.4 and Kir2.1 K(+) channel subunits co-assemble: a potential new contributor to inward rectifier current heterogeneity. J Physiol 544, 337–349 (2002). https://doi.org: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballester L. Y. et al. Trafficking-competent and trafficking-defective KCNJ2 mutations in Andersen syndrome. Hum Mutat 27, 388 (2006). https://doi.org: 10.1002/humu.9418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haruna Y. et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations of KCNJ2 mutations in Japanese patients with Andersen-Tawil syndrome. Hum Mutat 28, 208 (2007). https://doi.org: 10.1002/humu.9483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma D. et al. Golgi export of the Kir2.1 channel is driven by a trafficking signal located within its tertiary structure. Cell 145, 1102–1115 (2011). https://doi.org:S0092-8674(11)00649-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez-Hernandez M. et al. Brugada syndrome trafficking-defective Nav1.5 channels can trap cardiac Kir2.1/2.2 channels. JCI Insight 3 (2018). https://doi.org: 10.1172/jci.insight.96291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pini J. et al. Osteogenic and Chondrogenic Master Genes Expression Is Dependent on the Kir2.1 Potassium Channel Through the Bone Morphogenetic Protein Pathway. J Bone Miner Res 33, 1826–1841 (2018). https://doi.org: 10.1002/jbmr.3474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen S. B., Tao X. & MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature 477, 495–498 (2011). https://doi.org: 10.1038/nature10370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S. J. et al. Structural basis of control of inward rectifier Kir2 channel gating by bulk anionic phospholipids. J Gen Physiol 148, 227–237 (2016). https://doi.org: 10.1085/jgp.201611616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zangerl-Plessl E. M. et al. Atomistic basis of opening and conduction in mammalian inward rectifier potassium (Kir2.2) channels. J Gen Physiol 152 (2020). https://doi.org: 10.1085/jgp.201912422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagnen C. et al. New Structural insights into Kir channel gating from molecular simulations, HDX-MS and functional studies. Sci Rep 10, 8392 (2020). https://doi.org: 10.1038/s41598-020-65246-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadsby D. C. & Cranefield P. F. Two levels of resting potential in cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Gen Physiol 70, 725–746 (1977). https://doi.org: 10.1085/jgp.70.6.725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suh B. C. & Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu Rev Biophys 37, 175–195 (2008). https://doi.org: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soom M. et al. Multiple PIP2 binding sites in Kir2.1 inwardly rectifying potassium channels. FEBS Lett 490, 49–53 (2001). https://doi.org: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02136-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tully I. et al. Rarity and phenotypic heterogeneity provide challenges in the diagnosis of Andersen-Tawil syndrome: Two cases presenting with ECGs mimicking catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). Int J Cardiol 201, 473–475 (2015). https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kukla P., Biernacka E. K., Baranchuk A., Jastrzebski M. & Jagodzinska M. Electrocardiogram in Andersen-Tawil syndrome. New electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of type-1 Andersen-Tawil syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rev 10, 222–228 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannister M. L., MacLeod K. T. & George C. H. Moving in the right direction: elucidating the mechanisms of interaction between flecainide and the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Br J Pharmacol 179, 2558–2563 (2022). https://doi.org: 10.1111/bph.15718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zsolnay V., Fill M. & Gillespie D. Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca(2+) Release Uses a Cascading Network of Intra-SR and Channel Countercurrents. Biophys J 114, 462–473 (2018). https://doi.org: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.3775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katan M. & Cockcroft S. Phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate: diverse functions at the plasma membrane. Essays Biochem 64, 513–531 (2020). https://doi.org: 10.1042/EBC20200041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abriel H., Rougier J. S. & Jalife J. Ion channel macromolecular complexes in cardiomyocytes: roles in sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 116, 1971–1988 (2015). https://doi.org: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meadows L. S. & Isom L. L. Sodium channels as macromolecular complexes: Implications for inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Cardiovasc Res 67, 448–458 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willis B. C., Ponce-Balbuena D. & Jalife J. Protein assemblies of sodium and inward rectifier potassium channels control cardiac excitability and arrhythmogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308, H1463–1473 (2015). https://doi.org: 10.1152/ajpheart.00176.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siegel M. R. & Sisler H. D. Inhibition of Protein Synthesis in Vitro by Cycloheximide. Nature 200, 675–676 (1963). https://doi.org: 10.1038/200675a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Bemmelen M. X. et al. Cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5 is regulated by Nedd4-2 mediated ubiquitination. Circ Res 95, 284–291 (2004). https://doi.org: 10.1161/01.RES.0000136816.05109.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo L. et al. Calcium-dependent Nedd4-2 upregulation mediates degradation of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5: implications for heart failure. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 221, 44–58 (2017). https://doi.org: 10.1111/apha.12872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]