Abstract

A combination of hydrophobic chromatography on phenyl-Sepharose and reversed phase HPLC was used to purify individual tRNAs with high specific activity. The efficiency of chromatographic separation was enhanced by biochemical manipulations of the tRNA molecule, such as aminoacylation, formylation of the aminoacyl moiety and enzymatic deacylation. Optimal combinations are presented for three different cases. (i) tRNAPhe from Escherichia coli. This species was isolated by a combination of low pressure phenyl-Sepharose hydrophobic chromatography with RP-HPLC. (ii) tRNAIle from E.coli. Aminoacylation increases the retention time for this tRNA in RP-HPLC. The recovered acylated intermediate is deacylated by reversion of the aminoacylation reaction and submitted to a second RP-HPLC run, in which deacylated tRNAIle is recovered with high specific activity. (iii) tRNAiMet from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The aminoacylated form of this tRNA is unstable. To increase stability, the aminoacylated form was formylated using E.coli enzymes and, after one RP-HPLC step, the formylated derivative was deacylated using peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase from E.coli. The tRNAiMet recovered after a second RP-HPLC run exhibited electrophoretic homogeneity and high specific activity upon aminoacylation. These combinations of chromatographic separation and biochemical modification can be readily adapted to the large-scale isolation of any particular tRNA.

INTRODUCTION

Transfer RNA is a key component of the translational machinery. Experiments for detailed investigation of structure and function using in vitro translation systems often require highly purified tRNA species. Separation of biologically active pure and specific tRNAs is difficult due to the overall similarity in secondary and tertiary structures of different tRNA molecules. The reported methods for tRNA isolation comprise labor-intensive procedures that, after an extraction step on the starting biological material, combine techniques such as ionic exchange chromatography, solvent extraction, countercurrent extraction (1–6), chromatography on benzoyl-DEAE–cellulose (7) and reversed phase chromatography (8).

The first reports on purification of tRNA using reversed phase chromatography and benzoyl-DEAE–cellulose clearly indicated the superiority of these techniques as tools for tRNA separation (9,10). Reversed phase chromatography was adapted to high pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) during the 1980s and has become the most powerful tool for purification of low molecular weight nucleic acids. For isolation of tRNA, systems with high ionic strength in the mobile phase (11,12) or mixed mode variants (13–15) have been particularly useful. Other approaches combine the affinity of certain lectins for modified nucleotides of specific tRNAs, the interaction of boronyl groups with cis-diols (16) or specific binding of aminoacylated tRNAs to immobilized EF-Tu (17,18) for single step separation. However, the high efficiency of these techniques is not sufficient for quick isolation of many tRNA classes in preparative amounts. In the present work we report combinations of chromatographic separation and reversible biochemical modification of the tRNAs to achieve rapid and highly specific isolation on a large scale.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Escherichia coli wild-type strains MRE 600 and K12 were used (donated by K.H. Nierhaus). Total tRNA from brewer’s yeast was from Boehringer. Tryptone and yeast extract were from Difco. Phenyl-Sepharose (fast flow) and Sephadex G-25 were purchased from Pharmacia. CM 52 and DE 52 cellulose were from Whatman. All chemicals and solvents used were of the highest quality. [14C]Phenylalanine (470 mCi/mmol), [14C]isoleucine (354 mCi/mmol) and [14C]methionine (266 mCi/mmol) were purchased from Amersham. The HPLC system used for the RP-HPLC separations was from Waters Corp., with a 626 pump, a 600S control unit and a 996 photodiode array detector. Nucleosil C4 7 µm 300 Å columns from Macherey-Nagel or Delta Pak C4 15 µm 300 Å columns from Waters Corp. were used for semi-analytical and semi-preparative separations as indicated in the corresponding figures.

Bacterial cultures and extraction of total tRNA

Escherichia coli cells were cultured at 37°C in LB medium. The cells were harvested at mid log phase by low speed centrifugation (3000 r.p.m. for 15 min in a JA 10 Beckman rotor) and washed with 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.9% NaCl at 4°C to remove traces of culture medium. Washed cellular pellets were stored in portions of 5–10 g at –80°C until used. Extraction of cellular RNA was done following a reported procedure (19) with minor modifications. Cells were resuspended in 1.5 vol of 1.0 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.2. Phenol (1.5 vol) saturated with the same solution was added and, after 1 h mixing at 4°C, the phases were separated by centrifugation. The aqueous phase was recovered and the nucleic acids precipitated with ethanol. The fraction of total tRNA contained in the precipitate was separated from high molecular weight nucleic acids (rRNA and DNA fragments) by treatment with a high salt concentration and stepwise precipitation with isopropanol at 22°C (19).

Preparation of crude aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

The procedure followed was based on that described by Rheinberger et al. (20). In a typical preparation procedure 150 ml of S-150 extract from E.coli cells disrupted in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 6 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, were mixed with 15 g of DE 52 cellulose previously equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl. After 2 h at 0°C with occasional swirling, the mixture was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 30 min. The supernatant is the unbound fraction. The pelleted matrix was treated sequentially with 40 ml of the equilibration buffer with increasing concentrations of KCl (150, 200 and 500 mM). An equilibration of 2 h was followed by a centrifugation step in each case. The resulting fractions were dialyzed four times against 2 l of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 5% glycerol. The fractions corresponding to 150 and 200 mM KCl usually contained the maximal synthetase activities.

Aminoacylation assays

The amino acid acceptor activity of tRNA fractions was determined in assays of 25–50 µl containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 3–10 mM ATP, 1–10 µM 14C-labeled amino acid, 2–20 µg of protein from crude synthetase preparation (optimized for each amino acid) and varying amounts of tRNA (0.05–0.2 absorbance units at 260 nm according to the purity of the fraction). The amount of incorporated amino acid was determined after incubation for 15 min at 37°C by precipitation with cold trichloroacetic acid and filtration through glassfiber filters. The radioactivity retained in the filters was measured by liquid scintillation. For preparative aminoacylation the ionic conditions were similar but with larger (1–5 ml) assay volumes and 2- to 3-fold higher concentrations of tRNA and amino acid. The aminoacylated material was recovered after phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation.

Fractionation of tRNA

Hydrophobic chromatography on phenyl-Sepharose. Samples of 10 000–20 000 absorbance units at 260 nm (A260 units) of crude total tRNA (tRNAbulk) were applied to a 200 ml column (2.3 × 50 cm) of phenyl-Sepharose equilibrated with 20 mM NaAcO, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, pH 5.3, at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. The retained material (100%) was eluted with a negative gradient of (NH4)2SO4 in the same buffer, as indicated in Figure 1B. Eluted material showing absorption at 260 nm was pooled in 10 fractions covering the whole separation profile. Salt excess in fractions was eliminated by filtration on a preparative column of Sephadex G-25 (bed volume 1 l, 6 × 35 cm) equilibrated with 15 mM NaAcO, pH 5.3, 3 mM Mg(AcO)2, 75 mM NaCl. Fractions corresponding to high molecular weight excluded material were pooled and tRNA was recovered by precipitation with 1 vol of isopropanol. Acceptor activity for several amino acids was determined for each fraction.

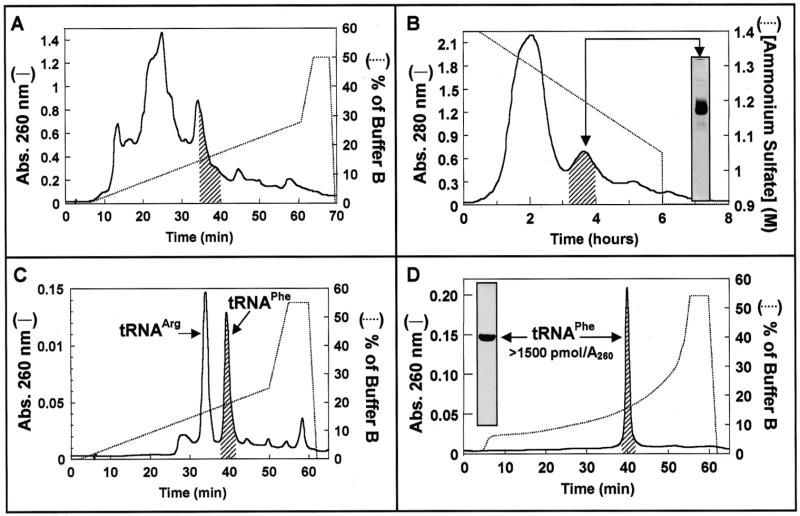

Figure 1.

Isolation of tRNAPhe from tRNAbulk of E.coli. (A) RP-HPLC. Aliquots of 20 A260 units of tRNAbulk dissolved in 50 µl of water were applied to a Delta Pak C4 15 µ 300 Å 3.9 × 300 mm column (Waters) equilibrated in buffer A (20 mM ammonium acetate pH 5.25, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 400 mM NaCl). Retained material was eluted with the indicated gradient (dotted line) of buffers A and B (60% methanol in buffer A). The shaded region under the chromatographic profile at 260 nm (line) indicates the position where Phe acceptor activity elutes. (B) Hydrophobic chromatography. Aliquots of 6000 A260 units of E.coli tRNAbulk were applied to phenyl-Sepharose (2.3 × 60 cm) equilibrated in 50 mM ammonium acetate pH 5.3, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1.5 M ammonium sulfate. Adsorbed material was eluted with a negative ammonium sulfate gradient from 1.4 to 0.9 M (dotted line). The shaded region under the chromatographic profile at 280 nm (line) indicates the location of Phe acceptor activity. (C) RP-HPLC chromatography [as described in (A)] of pooled material (250 A260 units) from the shaded region shown in (B). (D) Rechromatography of material recovered from the shaded peak in (C) (75 A260 units). Phenylalanine acceptor activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The insert in (B) shows the electrophoretic pattern of the pool of fractions from hydrophobic chromatography containing tRNAPhe acceptor activity (shaded region) and in (C) the insert shows the electrophoretic analysis of purified tRNAPhe.

Reversed phase high pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). A modification of a system previously used for separating acylated derivatives of tRNAPhe (11) was employed to optimize tRNA separation in this study. Samples of 1–4 (analytical runs) or 200–800 A260 units (preparative runs) of either crude or phenyl-Sepharose fractionated tRNA were applied to semi-analytical (0.5 × 25 cm) or preparative (1.5 × 25 cm) HPLC columns packed with reversed phase matrix C4 (pore diameter 300 Å, particle diameter 7 or 15 µm as indicated), respectively. HPLC systems were equilibrated with buffer A [20 mM NH4AcO, pH 5.5, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM Mg(AcO)2]. Retained material was eluted with programmed gradients of buffers A and B (60% methanol in buffer A) and recovered by precipitation with ethanol. Acceptor activity for amino acids was determined as described previously. Purified fractions were analyzed by PAGE under denaturing conditions and the nucleic acid bands were visualized after staining with ethidium bromide or toluidine blue.

Preparation of fMet-tRNAiMet

Specific aminoacylation of tRNAiMet from S.cerevisiae and formylation of the resulting Met-tRNAiMet were performed in a single incubation using the formylase and the corresponding methionyl-tRNA synthetase activities present in a tRNA-free S-100 fraction from E.coli (2,3,5). The formyl donor N10-formyltetrahydrofolic acid was prepared from the calcium salt of folinic acid: 12.5 mg of folinic acid (Serva) were dissolved in 1 ml of 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, then 110 µl of 1 M HCl were added and the solution was incubated at room temperature until the absorbance at 355 nm reached a maximum (conversion to N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolic acid, typically taking 3 h). In this form the reagent can be stored at –80°C before use. The final form of the formyl donor was obtained before synthesis of fMet-tRNAiMet, neutralising the intermediate solution by adding 1/10 vol of 1 M Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, and 1/10 vol of 1 M KOH. Quantitative conversion is indicated by decoloration (usually after 15–30 min at room temperature). The synthesis step was performed by incubation of tRNAbulk from S.cerevisiae (60 A260 units/ml; Boehringer) with 25 µM [14C]methionine (diluted to 9 c.p.m./pmol with non-labeled methionine), 2.5 mM formyl donor, tRNA-free S-100 fraction (200–300 µg protein/ml assay) and 3.6 mM ATP in 30 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.5, 5 mM Mg(AcO)2, 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol. After 20 min incubation at 37°C the reaction was stopped by addition of 1/10 vol of 3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.0, and phenol extraction. The material recovered after ethanol precipitation was resuspended in water and desalted by gel filtration on a NAP-25 column (Pharmacia) before RP-HPLC purification.

Isolation of peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (EC 3.1.1.29) from E.coli

A combination of published procedures for purification of formylase (21) and peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (PTH) (22) from E.coli was optimized to design a simple protocol for isolation of PTH from the same source.

Ammonium sulfate fractionation of the S-100 fraction from E.coli. An aliquot of 17.6 g of ammonium sulfate (32% saturation) was added slowly with constant stirring to 100 ml of S-100 fraction from E.coli, equilibrated at 0°C in an ice bath. After continuous stirring for 30 min (to ensure total dissolution of the salt) the solution was kept on ice for an additional 30 min period and the precipitated protein discarded by centrifugation (45 min at 16 500 g). A further 28 g of ammonium sulfate (72.5% saturation) was added slowly to the collected supernatant. The mix was stirred for 45 min and kept overnight (or for 6 h) at 4°C. The precipitated protein was recovered by centrifugation (16 500 g, 45 min, 4°C) and stored at –20°C or resuspended immediately in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.4. After 6 h dialysis against 20 vol (three changes) of 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.4, the protein solution (~150 ml) was fractionated by cation exchange chromatography.

Cation exchange chromatography on CM cellulose

The sample was applied to a 60 ml column (2.5 × 30 cm) of CM cellulose (Whatman) equilibrated in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.4, at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. A first wash with 170 ml of equilibration buffer at the same flow rate was followed by a second wash with 170 ml of 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.4, 50 mM NaCl, increasing the flow rate to 0.8 ml/min. Elution was performed with 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.4, 500 mM NaCl. The fractions containing eluted protein (a single peak) were concentrated and desalted by ultrafiltration (using Centricon™10 microconcentrators from Amicon) and stored in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.4, 5% glycerol at –80°C in small aliquots. This procedure yielded ~1 mg of purified protein.

RESULTS

We have designed a set of separation strategies for total tRNA extracts combining hydrophobic interaction-based chromatographic steps with reversible modifications of the tRNA molecule which confer differential chromatographic behavior allowing quick isolation. The following sections will show the application of such designs to purify three different tRNAs from total tRNA extracts (tRNAbulk) representative of typical purification problems in this field.

Isolation of tRNAPhe from E.coli

The ability of the RP-HPLC approach described in Materials and Methods to fractionate tRNAbulk from E.coli was examined first. As can be seen in Figure 1A, the phenylalanine acceptor activity was separated with relatively high efficiency from the majority of other tRNA species as it was restricted to a small portion of the elution profile. However, the region of tRNAPhe elution still had contaminant acceptor activities (mainly tRNAArg; data not shown). Submitting the tRNAbulk to a prior low pressure chromatographic step on phenyl-Sepharose (Fig. 1B) solved this problem. The resolution of this technique is significantly lower than that shown by RP-HPLC and the operation time much longer (see Fig. 1A and B). The main advantages of this procedure with respect to preparative RP-HPLC of the tRNAbulk are: (i) the possibility of processing 20 times more tRNAbulk at a time (16 000 versus 800 A260 units); (ii) even though the separation is based on the same kind of interaction, it does not proceed exactly alike, making the combination of both techniques useful. The material separated on phenyl-Sepharose was divided into 10 fractions (selected according to the shape of the elution profile), desalted on Sephadex G-25 and recovered after ethanol precipitation. Each fraction was analyzed for phenylalanine acceptor activity and the region containing tRNAPhe (shaded region in Fig. 1B) was submitted to RP-HPLC separation (Fig. 1C). The elution profile showed two major species identified as tRNAArg and tRNAPhe by aminoacylation assays. After rechromatography (Fig. 1D) the material recovered from the tRNAPhe peak had a phenylalanine acceptor activity of 1500 pmol/absorbance unit at 260 nm, close to the theoretical maximum, showed a unique band after denaturing PAGE (see insert in Fig. 1D) and was active in polyphenylalanine synthesis assays performed with 70S ribosomes and soluble factors from E.coli (data not shown). This approach allows the isolation of >1000 A260 units of high quality tRNAPhe in a few days.

Isolation of tRNAIle from E.coli

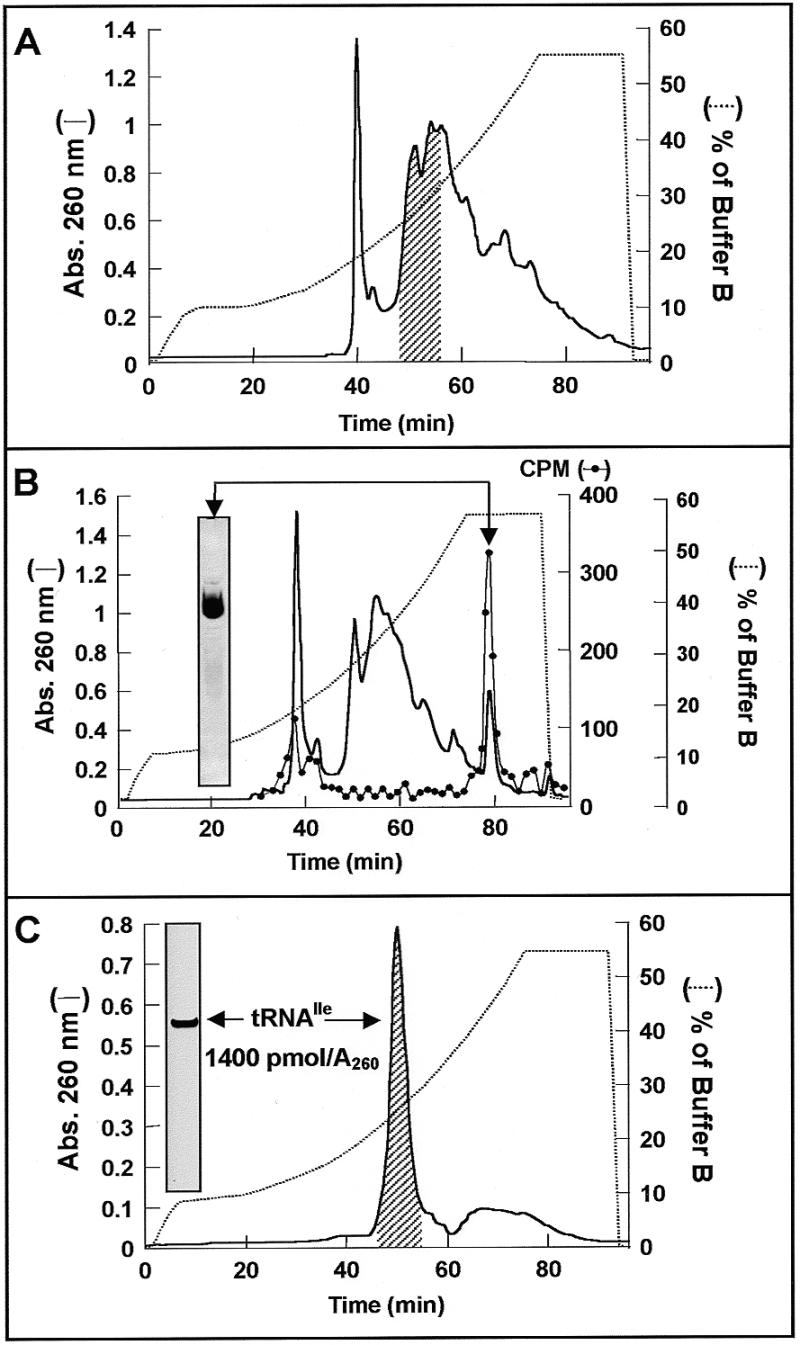

The isolation of tRNA species eluting in regions of maximal absorbance in the chromatographic profiles is more difficult because there are many contaminants with similar chromatographic behavior. As can be seen in Figure 2A, this is the case for tRNAIle (shaded region). Aminoacylation tests performed with material recovered from an optimized RP-HPLC elution gradient revealed isoleucine acceptor activity located in one of the highest absorbance regions of the profile. Performing the separation after preparative aminoacylation of tRNAbulk with labeled isoleucine showed that attachment of the cognate amino acid confers on tRNAIle a much higher retention time on the RP-HPLC chromatographic bed. The radioactivity pattern confirmed that Ile-tRNAIle eluted late in a low absorbance zone (see radioactivity profile in Fig. 2B). In order to recover deacylated tRNAIle it was necessary to remove the aminoacyl moiety from Ile-tRNAIle. This was done by reversing the aminoacylation reaction using the aminoacyl-tRNA, AMP and pyrophosphate as substrates for the synthetase (23). Figure 2C shows the chromatogram obtained after preparative deaminoacylation of the material recovered from the radioactive peak in Figure 2B. The isolated RNA had an acceptor activity of 1400 pmol/A260 unit and was well separated from the small amounts of late eluting contaminants. The homogeneity of the final tRNA fraction and the efficiency of the last HPLC separation were demonstrated by PAGE under denaturing conditions (inserts in Fig. 2B and C). Essentially the same isolation strategy can be applied to the fractions of tRNAbulk eluting from phenyl-Sepharose containing isoleucine acceptor activity (Fig. 1B, material eluted during the first 2 h). The procedure can be performed in 2 days starting from tRNAbulk or phenyl-Sepharose fractions.

Figure 2.

Isolation of tRNAIle from tRNAbulk of E.coli. (A) Aliquots of 20 A260 units of tRNAbulk from E.coli were submitted to RP-HPLC as described in Figure 1A using an optimized gradient of buffer B (dotted line) for separation of Ile acceptor activity. The shaded region under the chromatographic profile at 260 nm (line) indicates the position where isoleucine acceptor activity elutes. (B) RP-HPLC Separation of tRNAbulk after preparative aminoacylation with [14C]isoleucine (diluted to 9 c.p.m./pmol with non-labeled isoleucine) as indicated in Materials and Methods. Samples (5 µl) were analyzed for the presence of [14C]Ile-tRNAIle via liquid scintillation counting (circle). The fractions comprising the radioactivity peak were pooled and analyzed by denaturing PAGE (see insert). (C) Recovery of tRNAIle after deacylation via RP-HPLC. The isoleucine acceptor activity of pooled material (shaded region) was determined by analytical aminoacylation using [14C]isoleucine (730 c.p.m./pmol) and submitted to electrophoretic analysis (insert).

Isolation of tRNAiMet from S.cerevisiae

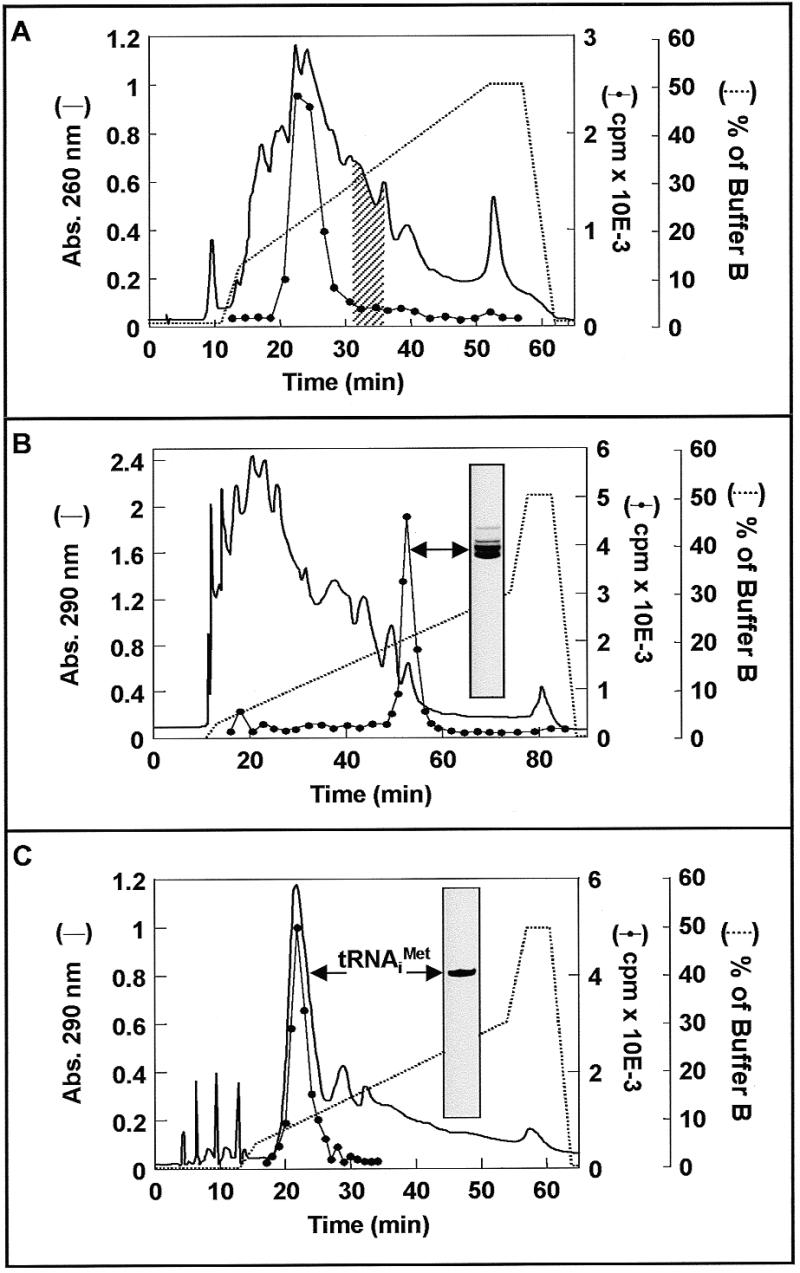

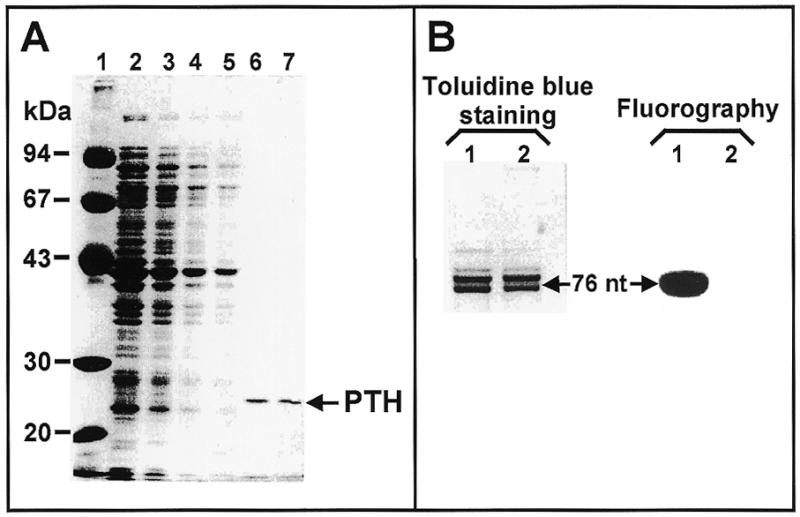

Isolating tRNAiMet from S.cerevisiae presented additional complications to the ones solved for tRNAIle from E.coli. First, the deacylated form of this tRNA co-eluted in RP-HPLC with the bulk of contaminants (see the aminoacylation test traces in Fig. 3A). Second, the fact that the aminoacylated form of this tRNA had a sufficiently shifted elution position (Fig. 3A, shaded region) suggested that the approach used for tRNAIle could be employed in this case. However, the inherent low stability of this aminoacyl-tRNA species (24) makes the direct application of such a strategy impracticable. Met-tRNAiMet is rapidly deacylated during the necessary manipulations of RP-HPLC purification. To solve this problem we decided to make use of the ability of E.coli enzymes to catalyze the methionylation and subsequent formylation of eukaryotic initiator tRNAs (2–5). fMet-tRNAiMet is very stable and has the additional advantage of being retained longer in the RP-HPLC matrix, allowing a better separation of contaminants (see the radioactivity trace in Fig. 3B). Electrophoretic analysis of the fraction containing fMet-tRNAiMet, however, revealed the presence of significant amounts of different RNA species (insert in Fig. 3B). To recover deacylated tRNAiMet after preparative RP-HPLC isolation of fMet-tRNAiMet and to separate the remaining contaminants, we devised an efficient and harmless deacylation procedure: treatment with PTH from E.coli. The enzyme was isolated from the S-100 fraction of cell lysates using a simple and quick procedure comprising ammonium sulfate fractionation and CM cellulose chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. Figure 4A shows SDS–PAGE analysis of the starting material (lane 2), the intermediate fractions (lanes 3–5) and the final product (lanes 6 and 7). The preparation was >60% pure and showed the characteristic PTH activity. Kinetics experiments demonstrated that 0.15 µg of the enzyme preparation were able to catalyze >97% deacylation of 50 pmol fMet-tRNAiMet after 15 min incubation at 30°C (data not shown). Figure 4B shows that the enzyme is not contaminated with RNase activity. Denaturing polyacrylamide gel analysis clearly showed almost identical electrophoretic patterns before and after deacylation (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2, respectively). Detachment of the f[14C]Met group after incubation with PTH is shown in the corresponding autoradiogram (see Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2 in the autoradiogram panel).

Figure 3.

Isolation of tRNAiMet from S.cerevisiae. (A) Analysis of methionine acceptor activity in a RP-HPLC separation of tRNAbulk components. Aliquots of 10 A260 units of tRNAbulk were applied to a Nucleosil C4 7 µ 300 Å 2.4 × 250 mm column (Macherey-Nagel) equilibrated with buffer A and eluted with the indicated gradient of buffer B (dotted line) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The tRNA content of the fractions (500 µl each) was precipitated with ethanol and redissolved in 300 µl of water. The methionine acceptor activity of 20 µl samples from every fraction was determined performing aminoacylation tests under standard conditions for heterologous initiator tRNA (see preparation of fMet-tRNAiMet in Materials and Methods) using 1 nmol [14C]methionine (550 c.p.m./pmol) and 10 µg crude synthetases from E.coli. Line, absorbance at 260 nm; circle, c.p.m. of [14C]methionine incorporated in aminoacylation tests. The shaded region indicates the elution position of [14C]Met-tRNAiMet when aminoacylation was performed before the HPLC separation. (B) Similar to (A), but with aminoacylation and formylation prior to RP-HPLC separation. Excess formyl donor was removed from the sample by gel filtration on Sephadex G-25. The radioactivity profile (circle) indicates the position of f[14C]Met-tRNAiMet and the insert contains the denaturing PAGE pattern of pooled radioactive fractions. (C) RP-HPLC purification of deacylated tRNAiMet. Aliquots of 6000 pmol f[14C]Met-tRNAiMet (550 c.p.m./pmol, 809 pmol/A260 unit) were incubated with 1 mg of purified PTH in 6 ml of deacylation mix for 20 min at 30°C (an analytical cold TCA precipitation made at the end of the incubation indicated 97.9% deacylation). After phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation the material was submitted to RP-HPLC as described in (A). The tRNA content of the fractions was precipitated with ethanol and redissolved in 300 µl of water and the [14C]methionine acceptor activity determined (circle). The material eluting from 19 to 24 min corresponded to tRNAiMet with an average acceptor activity of 1700 pmol/A260 and showed a unique homogeneous band upon denaturing PAGE analysis (insert).

Figure 4.

Isolation and activity test of the PTH from E.coli. (A) SDS–PAGE analysis of the fractions obtained during the isolation procedure described in Materials and Methods and Table 1. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, S-100 fraction; lane 3, 70% saturated pellet after dialysis; lane 4, unbound fraction on CM cellulose; lane 5, 50 mM NaCl wash; lanes 6 and 7, final product from two different isolations. (B) Samples of 0.1 A260 units of f[14C]Met-tRNAiMet before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) 15 min incubation under deacylation conditions were applied to a denaturing 12.5% polyacrylamide gel. The RNA species were visualized via toluidine blue staining (left). Fluorography (right) was of the same gel after destaining and treatment with Amplify (Amersham). A second sample of deacylated tRNA (corresponding to 40 pmol of the original fMet-tRNAiMet) was incubated under methionylation conditions for 15 min at 37°C and re-aminoacylation was estimated to be 97.4% by cold TCA precipitation.

Purified PTH was used for preparative deacylation of fMet-tRNAiMet (see legend to Fig. 3C) and deacylated tRNAiMet was recovered after RP-HPLC (Fig. 3C). Methionine acceptor activity was associated with the rapidly eluting major absorbance peak (compare radioactivity trace and absorbance profile in Fig. 3C), as expected considering the position of deacylated tRNAiMet when tRNAbulk was submitted to analytical chromatography and subsequent analysis (see radioactivity trace in Fig. 3A). Homogeneity of the corresponding fractions was checked by denaturing PAGE (insert in Fig. 3C). Fractions corresponding to electrophoretically pure tRNAiMet accepted an average of 1700 pmol methionine/absorbance unit at 260 nm.

DISCUSSION

In spite of the resolution power of modern separation techniques such as RP-HPLC, isolation of single tRNA species is still a difficult task due to the overall structural similarity of the different tRNA molecules found in nature. This problem was solved in the past by combining time-consuming separation protocols. We have designed a set of separation strategies combining hydrophobic interaction-based chromatographic steps with reversible modifications of the tRNA molecule. Relatively few regions of the native tRNA molecule are able to interact strongly with a hydrophobic bed; fundamentally the exposed single stranded regions. One of them is surely the anticodon region because it has been specifically selected by nature to expose unpaired bases. The obvious differences among different tRNAs in the anticodon regions should account for a large part of the separation obtained when total deacylated tRNA is chromatographed on hydrophobic matrices. Figure 1A and B shows the separation profiles obtained when total tRNA from E.coli was submitted to RP-HPLC or hydrophobic chromatography on phenyl-Sepharose, respectively. Despite the obvious differences in the detailed shapes of the profiles and the operation time, the relative location of different tRNA species, as revealed by analytical aminoacylation tests, showed an overall similarity. It follows that the retention of tRNA molecules on both matrices should be determined by similar interactions. For preparative purposes, phenyl-Sepharose has the advantage of allowing separation of 25 times more sample per run. In some cases, simply executing a second run using an RP-HPLC protocol can yield highly pure and biologically active products. The peak labeled as tRNAPhe in Figure 1C corresponded to material with an amino acid acceptor activity >1500 pmol/A260 unit and gave a single species profile when rechromatographed using an optimized elution gradient (Fig. 1D). The tRNAArg peak in Figure 1C had a slightly lower acceptor activity (~1400 pmol/A260 unit), which was increased upon rechromatography (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when the material containing the phenylalanine acceptor activity in the profile of Figure 1A (shaded region) was submitted to RP-HPLC, as shown in Figure 1C. Therefore, the use of phenyl-Sepharose is justified by the ability to process higher amounts of sample per chromatographic run. In this way the isolation procedure for preparative amounts of tRNA is shortened and the useful life of the more expensive RP-HPLC columns is increased. Another advantage of this approach is that the remaining regions of the separation profile obtained with phenyl-Sepharose contain a suitable starting material for isolation of other tRNA species.

The results obtained with tRNAPhe represent the first useful strategy for quick isolation of specific tRNAs: an opportune combination of hydrophobic interaction-based separation procedures. It is interesting to notice that this approach can be applied with high efficiency for the separation of eukaryotic tRNAPhe. The presence of the modified base wyosine in the anticodon loop results in high retention on RP-HPLC chromatographic beds like the ones used in this study. In some cases, such as total tRNA extracts from rabbit liver (25) or yeast (14), an optimized RP-HPLC protocol is enough to obtain fairly pure tRNAPhe eluting well separated from the bulk of tRNA.

A second separation strategy was based on another region of the tRNA molecule containing unpaired and exposed bases: the 3′-terminus. This end of the molecule has a universally conserved sequence, CCA, and, therefore, contributes to the chromatographic behavior on hydrophobic matrices mostly by triggering stronger binding of all tRNA species. It follows that the change conferred by aminoacylation and a further modification via formylation or acetylation should significantly modify the chromatographic properties. The case of tRNAIle from E.coli illustrates well this affirmation. The deacylated form of this tRNA elutes together with many other tRNA species in both RP-HPLC (Fig. 2A, shaded region) and on phenyl-Sepharose (data not shown). This circumstance makes efficient isolation using a combination like that successful for tRNAPhe infeasible. In this case aminoacylation produced a very significant shift in the retention time, as indicated by the radioactivity trace in Figure 2B. When the [14C]Ile-tRNAIle collected was submitted to enzymatic deacylation and a second RP-HPLC run (Fig. 2C) the deacyl-tRNAIle eluted in about the same position observed for the separation of tRNAbulk (Fig. 2A) and showed a high purity (>1400 pmol/A260).

The case of tRNAiMet from S.cerevisiae represented a serious challenge. As for tRNAIle, aminoacylation conferred a significant shift in the retention time (Fig. 3A, compare the radioactivity trace indicating the position of deacyl-tRNAiMet with the shaded region where Met-tRNAiMet elutes). However, the low stability of this particular aminoacyl-tRNA (24) made it impossible to apply the aminoacylation–deacylation scheme. The need for more stability was fulfilled by synthesis of fMet-tRNAiMet instead. This further modification of the 3′-end triggered an even higher retention time (see radioactivity trace in Fig. 3B). Quantification of the total A260 units and radioactivity present in the pooled fractions containing formyl-[14C]Met-tRNAiMet revealed a specific activity of ~800 pmol/A260 unit, indicating a 30- to 35-fold purification in only one chromatographic step. Since the aim was to obtain deacylated tRNA with even higher specific activity, we developed an efficient deacylation procedure using PTH from E.coli before performing a second RP-HPLC separation. The enzyme was purified using a combination of previously published procedures (21,22) optimized for the isolation of PTH, consisting of an ammonium sulfate fractionation step and cation exchange chromatography on CM cellulose. The procedure yielded ~1 mg purified protein/100 ml S-100 fraction processed (see Table 1), >70% pure when analyzed by SDS–PAGE (see Fig. 4) and active for deacylation of fMet-tRNAiMet (Fig. 4B). It is important to notice that the procedure is compatible with the usual isolation protocol for aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases by using the unbound DEAE–cellulose fraction (see Materials and Methods) as starting material. It can also be used with the S-100 fraction of PTH-overproducing strains of E.coli (data not shown).

Table 1. Purification of PTH from E.coli.

| Fraction | Volume (ml) | Total (mg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium sulfate fractionation | S-150 | 100 | 1788 |

| 70% ASa | 150 | 1059 | |

| CM cellulose chromatography | Unbound | 150 | 482 |

| First wash (equilibrium buffer) | 170 | 548 | |

| Second wash (50 mM NaCl) | 170 | 8 | |

| Final product (500 mM NaCl) | 1.5 | 1.2 |

a70% saturated pellet after dialysis.

When the pool of fMet-tRNAiMet was treated with enzyme and submitted to RP-HPLC, the deacylated tRNA eluted earlier than the acylated form and its contaminants (Fig. 3C). In consequence, the recovered tRNAiMet showed a high level of purity when analyzed by denaturing PAGE (inset in Fig. 3C) and analytical aminoacylation assays, where the methionine acceptor activity was ~1700 pmol/A260 unit (data not shown). This higher amino acid acceptance as compared with the cases of purified tRNAPhe and tRNAIle can be explained by the special type of aminoacylation assay performed. In the case of initiator tRNA the aminoacylation step is followed by a formylation reaction (see preparation of fMet-tRNAiMet in Materials and Methods), which drives the tRNA acylation to near completion. Similar results were observed with other eukaryotic initiator tRNAs (25) and with the initiator tRNA from E.coli using slightly more alkaline conditions (pH ~8.1) in the deacylation incubation performed before the final RP-HPLC purification step (26).

N-blocked aminoacyl-tRNAs can be efficiently separated from the corresponding deacyl- and aminoacyl-tRNAs using optimized HPLC systems (11,13). The fact that a chemical modification corresponding to <0.5% of the tRNA molecular mass significantly changes retention on a reversed phase matrix is a strong indication that tRNAs may interact with hydrophobic materials through relatively small portions of the molecule, like the anticodon region and the unpaired CCA 3′-end. Since PTH is able to deacylate N-blocked aminoacyl-tRNAs (22) and synthesis of such derivatives is highly efficient for any aminoacyl-tRNA via chemical acetylation (27,28), it is possible to use the previously described approach for isolating other tRNA species.

The results obtained demonstrate that a simple combination of chromatographic techniques can yield tRNA of high purity, comparable to the best commercial standards in preparative amounts. A first step of separation by hydrophobic chromatography allows the processing of large amounts of starting material and increases the efficiency in the final separation by reversed phase HPLC. This effect may be the result of a decrease in chromatographic aberrations introduced by interaction between distinct tRNA species during HPLC. The use of simple and reversible modifications like aminoacylation and, in some cases, subsequent specific blockage of the free amino group makes it possible to perform a second highly efficient separation taking advantage of the rapidity of HPLC. Other recently published approaches, like affinity chromatography using inmobilized Tu factor (17,18) or streptavidin binding of N-biotinylated aminoacyl-tRNAs (29), can also yield highly pure aminoacyl-tRNAs in one chromatographic step. However, these strategies are limited in the amount of material that can be processed at one time, are more expensive and require much more prior biochemical work.

Recent reports of detailed ribosomal models tending to atomic resolution (30–32) suggest that significant amounts of highly purified tRNAs will be necessary for the construction of specific functional complexes of structural relevance. The methodology presented here provides a reliable and efficient way to obtain the needed materials.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to Prof. Dr Knud H. Nierhaus for helpful discussions and advice. We wish to acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Doris Finkelmeier, Lic. Ninoska Ramirez and Lic. Edgar Tovar. This work was supported by grants from the CDCH Universidad de Carabobo (94-023), CONICIT-Venezuela (PI 126) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cherayil J.D. and Bock,R.M. (1965) Biochemistry, 4, 1174–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeishi K., Ukita,T. and Nishimura,S. (1968) J. Biol. Chem., 243, 5761–5769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.RajBhandary U.L. and Gosh,H.P. (1969) J. Biol. Chem., 244, 1104–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanley W.M. (1972) Anal. Biochem., 48, 202–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley W.M. (1974) Methods Enzymol., 29, 530–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bose K.K., Chatterjee,N.K. and Gupta,N.K. (1974) Methods Enzymol., 29, 522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillam I., Milward,S., Blew,D., von Tigerstrom,M., Wimmer,E. and Tener,G.M. (1967) Biochemistry, 6, 3043–3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelmers A.D., Weeren,H.O., Weiss,J.F., Pearson,R.L., Stulberg,M.P. and Novelli,D. (1971) Methods Enzymol., 20, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wimmer E., Maxwell,J.H. and Tener,G.M. (1968) Biochemistry, 7, 2623–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walters L.C. and Novelli,G.D. (1971) Methods Enzymol., 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odom O.W., Deng,H.-Y. and Hardesty,B. (1988) Methods Enzymol., 164, 174–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue H., Shen,W. and Wong,J.T.F. (1993) J. Chromatogr., 613, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bischoff R. and McLaughlin,L.W. (1984) J. Chromatogr., 317, 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bischoff R. and McLaughlin,L.W. (1985) Anal. Biochem., 151, 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricker R.D. and Kaji,A. (1988) Anal. Biochem., 175, 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhal R.P. (1983) J. Chromatogr., 266, 359–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro S., Nock,S. and Sprinzl,M. (1995) Anal. Biochem., 228, 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinali G. (1997) J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods, 34, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrenstein G. (1965) Methods Enzymol., 12, 588–595. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rheinberger H.-J., Geigenmüller,U., Wedde,M. and Nierhaus,K.H. (1988) Methods Enzymol., 164, 658–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickerman H.W. (1971) Methods Enzymol., 20, 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yot P., Paulin,D. and Chapeville,F. (1971) Methods Enzymol., 20, 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg P., Bergmann,F.H., Ofengand,E.J. and Dieckmann,M. (1961) J. Biol. Chem., 236, 1726–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hentzen D., Mandel,P. and Garel,J.-P. (1972) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 281, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El’skaya A.V., Ovcharenko,G.V., Palchevskii,S.S., Petrushenko,Z.M., Triana-Alonso,F.J. and Nierhaus,K.H. (1997) Biochemistry, 36, 10492–10497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jünemann R., Wadzack,J., Triana-Alonso,F.J., Bittner,J.U., Caillet,J., Meinnel,T., Vanatalu,K. and Nierhaus,K.H. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 907–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haenni A.-L. and Chapeville,F. (1966) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 114, 135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rappoport S. and Lapidot,Y. (1974) Methods Enzymol., 29, 685–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putz J., Wientges,J., Sissler,M., Giege,R., Florentz,C. and Schwienhorst,A. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 1862–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cate J.H., Yusupov,M.M., Yusupova,G.Z., Earnest,T.N. and Noller,H.F. (1999) Science, 285, 2095–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clemons W.M. Jr, May,J.L., Wimberly,B.T., McCutcheon,J.P., Capel,M.S. and Ramakrishnan,V. (1999) Nature, 400, 833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tocilj A., Schlunzen,F., Janell,D., Gluhmann,M., Hansen,H.A., Harms,J., Bashan,A., Bartels,H., Agmon,I., Franceschi,F. and Yonath,A. (1999) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14252–14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]