Abstract

Chiral ketones and their derivatives are useful synthetic intermediates for the synthesis of biologically active natural products and medicinally relevant molecules. Nevertheless, general and broadly applicable methods for enantioenriched acyclic α,α-disubstituted ketones, especially α,α-diarylketones, remain largely underdeveloped, owing to the easy racemization. Here, we report a visible light photoactivation and phosphoric acid–catalyzed alkyne-carbonyl metathesis/transfer hydrogenation one-pot reaction using arylalkyne, benzoquinone, and Hantzsch ester for the expeditious synthesis of α,α-diarylketones with excellent yields and enantioselectivities. In the reaction, three chemical bonds, including C═O, C─C, and C─H, are formed, providing a de novo synthesis reaction for chiral α,α-diarylketones. Moreover, this protocol provides a convenient and practical method to synthesize or modify complex bioactive molecules, including efficient routes to florylpicoxamid and BRL-15572 analogs. Computational mechanistic studies revealed that C-H/π interactions, π-π interaction, and the substituents of Hantzsch ester all play crucial roles in the stereocontrol of the reaction.

A de novo access to chiral α,α-disubstituted ketones by visible-light photoactivation and phosphoric acid catalysis is developed.

INTRODUCTION

Diarylmethine chiral centers are important and ubiquitous organic building blocks (1–3). Carbonyl compounds with α-diarylmethine chiral centers, such as α,α-diarylketones, are a distinct class of molecules with diverse biological properties and are found in natural products, organic functional materials, and pharmaceuticals (Fig. 1A) (4–8). Despite the advances in asymmetric synthetic chemistry, few efficient methods have been developed for the enantioselective construction of such privileged scaffolds (9–13). The difficulty in producing these tertiary centers sited at the α-position of carbonyl compounds stems from the product containing more acidic α-H than the starting material, causing the racemization via enolization under basic or acidic conditions (14–17). The inherent properties of α,α-diaryl carbonyl compounds make the stereoselectivity of their synthesis extremely difficult to control. The asymmetric transition metal–catalyzed α-arylation of ketone (18) or α-haloketone (19, 20) is a powerful and straightforward method for synthesis of α,α-disubstituted ketones. However, the methods proved unsuitable for the synthesis of noncyclic α,α-diarylketones; in other words, one of the substituents at α-site of ketone was only alkyl group. Moreover, geometrically well-defined silyl enol ether substrates generally need to be prepared in advance (Fig. 1B). Currently, one study by Guo and colleagues investigated asymmetric electrochemical oxidative coupling between 2-acyl imidazoles and catechols to form chiral α,α-diarylketones (21). The auxiliary N-thienyl–substituted imidazole group is critical for the yield and enantioselectivity of the reaction (Fig. 1B). Despite these impressive advances, these approaches rely on the multistep production of prefunctionalized substrates, necessitating additional chemical steps and purifications and cannot produce α,α-diarylketones substituted with alkyl or aryl groups (Fig. 1B, R = alkyl, aryl) (9–21). Therefore, a simple and practical strategy for producing diverse α,α-diarylketone derivatives with high enantioselectivities from abundant feedstocks is highly desirable.

Fig. 1. Designing strategies for constructing chiral α,α-diarylketones.

(A) Natural products and drug molecules containing α,α-diarylketones and derivatives. (B) Previous work to chiral α,α-diarylketones. (C) New strategy for chiral synthetic blocks. (D) Our strategy: Alkyne-carbonyl metathesis/transfer hydrogenation one-pot reaction for the synthesis of chiral α,α-diarylketones.

Visible light–promoted asymmetric reactions have exhibited a powerful protocol to create chiral topologically complex molecular architectures via distinctive reactive intermediates, which are generally difficult to achieve through other conventional thermal way (22–36). Despite many progresses, the visible light–induced alkyne-carbonyl metathesis (ACM) reaction only draws few attentions (37–42). We envisioned whether a visible light–promoted ACM reaction could be achieved, followed by an asymmetric catalytic α-selective addition to an in situ generated unsaturated carbonyl intermediate to obtain a chiral molecule (Fig. 1C). Notably, previous work has mainly used high-energy ultraviolet (UV) light for photoirradiation-promoted ACM reaction, resulting in a low yield, low regioselectivity, and a limited range of substrates (43–45). Undoubtedly, the successful asymmetric one-pot protocol would provide a previously unknown strategy for synthesizing chiral building blocks. Very recently, our group and Lu’s group have successfully constructed chiral quaternary carbon centers using this strategy (46, 47). In contrast to the quaternary carbon centers, the chiral tertiary carbon stereocenters at the α-position of the carbonyl group are more challenging. α-Tertiary carbonyls such as α,α-diarylketones are easily racemized via noncontrolled by-pathways, adding more complexity to pursuing asymmetric catalytic synthesis (48). In this work, we describe the synthesis of chiral tertiary carbon at the α-position of ketone. A novel visible light photoactivation/phosphoric acid–catalyzed ACM/transfer hydrogenation (49) one-pot reaction of alkynes, benzoquinones, and Hantzsch esters is developed. This work provides a new general and mild method for the construction of synthetically useful enantioenriched α,α-diarylketones. Moreover, the reaction provides a convenient and practical method to modify complex bioactive molecules, such as florylpicoxamid, 2-(diarylmethyl)oxirane, and BRL-15572 analog (Fig. 1D).

RESULTS

Initially, 1-phenylpropyne 1a and benzoquinone 2 were used as model substrates, and Hantzsch ester 3a was the hydride donor (Table 1). Notably, UV-visible absorption spectra of benzoquinone in dichloromethane showed a broad weak band at 439 nm (436 nm) due to the n-π* transition. The n-π* absorption band overlapped with the wavelength of the blue light-emitting diode (LED) (for details, see fig. S1). Accordingly, it is feasible to activate benzoquinone 2 and promote the reaction under visible light (50). Various chiral phosphoric acids were examined as potential catalysts (entries 1 to 8). When the 1,1'-bi-2-naphthol (BINOL)-derived phosphoric acid (R)-C1 was the catalyst, the reaction proceeded smoothly to produce the desired α,α-diarylketone 4 in quantitative yield, however, with a low enantiomeric excess (ee) of 9% (entry 1). Further evaluation of other catalysts identified that (S)-C4 could provide moderate enantioselectivity (entry 4, −52% ee). Unfortunately, the use of 1,1′-spirobiindane-7,7′-diol (SPINOL) backbones did not offer good reaction outcomes (entries 5 to 8, up to only −25% ee). We then determined the structural influence of Hantzsch ester on the stereoselectivity of this reaction (entries 9 to 13). A trend toward improved enantiocontrol was observed with an increase in the size of the ester moieties (entries 4 and 9 to 11: R1 = Me, −49% ee; R1 = Et, −52% ee; R1 = Bn, −55% ee; R1 = t-Bu, −61% ee). Moreover, increasing the length of the side chain at the 2,6-dialkyl position also considerably afforded the stereoselectivity of the reaction (entries 9, 12, and 13: R2 = Me, −49% ee; R2 = Et, −61% ee; R2 = n-Bu, −69% ee). Further evaluation of the effects of solvents, reaction temperatures, and additives on the reaction was conducted (for details, see tables S1 to S5). However, only an ee of −76% was obtained in these experiments (entry 15). Considering the easy racemization of the product α,α-diarylketone 4, the less acidic H8-BINOL–derived phosphate catalysts were further screened (entries 16 to 18). Among them, phosphoric acid (R)-C7 provided the best results (entry 18, 90% ee).

Table 1. Condition optimization.

Performed with compounds 1a (0.2 mmol) and 2 (0.1 mmol) in the solvent, with stirring for 4 hours under 2 × 35 W blue LEDs at room temperature. Compounds 3a (0.15 mmol) and CPA (0.005 mmol) were added, with stirring at room temperature for 1 hour. Yield of isolated product. ee: determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase.

| Entry | Catalyst | 3 | Yield (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (R)-C1 | 3a | 99 | 9 |

| 2 | (R)-C2 | 3a | 99 | 17 |

| 3 | (S)-C3 | 3a | 98 | −5 |

| 4 | (S)-C4 | 3a | 99 | −52 |

| 5 | (R)-C8 | 3a | 90 | −25 |

| 6 | (R)-C9 | 3a | 99 | −15 |

| 7 | (R)-C10 | 3a | 99 | 0 |

| 8 | (R)-C11 | 3a | 93 | −15 |

| 9 | (S)-C4 | 3b | 99 | −49 |

| 10 | (S)-C4 | 3c | 99 | −55 |

| 11 | (S)-C4 | 3d | 99 | −61 |

| 12 | (S)-C4 | 3e | 99 | −61 |

| 13 | (S)-C4 | 3f | 99 | −69 |

| 14* | (S)-C4 | 3f | 99 | −75 |

| 15*,† | (S)-C4 | 3f | 99 | −76 |

| 16*,† | (R)-C5 | 3f | 99 | 67 |

| 17*,† | (R)-C6 | 3f | 98 | 66 |

| 18*,† | (R)-C7 | 3f | 99 | 90 |

*Run at −60°C for 3 hours.

†4 Å MS (60 mg) was used.

With the determined optimal reaction conditions, the substrate scope of this ACM/transfer hydrogenation one-pot reaction was investigated. A variety of aryl internal alkynes (51) reacted with benzoquinone 2 and Hantzsch ester 3f (52), yielding the corresponding enantioenriched α′-alkyl substituted α,α-diarylketones (4 to 47) with excellent enantioselectivities under mild conditions (Fig. 2). We determined the effect of the alkyl substituents on the reaction outcome. Substrates with alkyl substituents including methyl, ethyl, cyclopropyl, and n-butyl efficiently generated the desired products (4 to 10) with up to 99% yield and 90% ee. The absolute configuration of compound 9 was unambiguously assigned by x-ray crystallographic analysis. Next, we explored methyl and n-butyl aryl internal alkynes as the reaction. Both the electronic properties of the substituents on the phenyl ring (5 to 7 and 11 to 22) and their positions [para, meta, or ortho (16 to 18)] have no apparent effect on the stereoselectivities of the reaction (83 to 94% ee). Moreover, this reaction tolerated a series of reactive functional groups, including sulfonyl ester (23), nitro (24), cyano (25), ester (26), aldehyde (27), and ketone (28 to 33) groups. Notably, alkynes containing additional electrophilic sites (unsaturated ketone) likewise gave a single product (32, 94% ee), and the 1,4-addition product was not monitored. Moreover, the reaction was compatible with the fused and heterocyclic substituents: naphthalene (34 and 35), phenanthrene (36), and quinoline (37).

Fig. 2. Reaction scope of alkylarylalkynes.

Performed with compounds 1 (0.2 mmol) and 2 (0.1 mmol) in CH2Cl2, with stirring for 4 hours under 2 × 35 W blue LEDs at room temperature. Compound 3f (0.15 mmol), 4 Å MS (60 mg), and (R)-C7 (0.005 mmol) were added, with stirring at −60°C for 3 hours. Yield of isolated product. ee determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase.

Enantiopure molecules with trifluoromethyl groups are known to have unique physiological properties (53). Trifluoromethyl-substituted internal alkynes with various functional groups were used to separately synthesize a series of α,α-diarylketones (Fig. 2). This yielded excellent enantioselectivities under mild conditions (39 to 47, up to 95% ee). Meanwhile, the compatibility of the α′-position functional groups has been further proven. For example, halogenated hydrocarbon (39), alkyl (40 to 42), silyl ether (43 and 44), ester (45), and alkynyl (46) groups were all tolerated.

Next, we evaluated the performance of visible light/chiral phosphoric acid in these reactions of diaryl internal alkynes (Fig. 3). Symmetrical diarylacetylenes were tested, with the conditions reoptimized because of their distinct properties (for details, see table S6). When (R)-C2 was used as the catalyst, a variety of enantioenriched 1,2,2-triarylethanones (48 to 60) were synthesized with good-to-excellent stereoselectivities (80 to 93% ee). In general, neither the electronic property of a substituent on the aromatic ring (48 to 54 and 58 to 60, up to 93% ee) nor its position (55 to 57, 80 to 88% ee) had a marked effect on the enantioselectivities. The absolute configuration of compound 54 was unambiguously assigned by x-ray crystallographic analysis. The unsymmetric diarylacetylenes were equally well compatible with the reaction but with lower regioselectivity [61 to 63 and 61′ to 63′, up to 92% ee, 1.7:1 to 2.2:1 regioselectivity ratio (rr)]; for details of regioselectivity analysis, see mechanistic discussion section).

Fig. 3. Reaction scope of diarylalkynes.

Performed with compounds 1′ (0.2 mmol) and 2 (0.1 mmol) in CH2Cl2, with stirring for 4 hours under 2 × 35 W blue LEDs at room temperature. Compound 3f (0.15 mmol), 4 Å MS (60 mg), and (R)-C2 (0.005 mmol) were added, with stirring at −60°C for 3 hours. Yield of isolated product. ee determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase.

The functionalization of complex molecules illustrated the utility of this methodology. As depicted in Fig. 4, transformations using natural compound and drug molecule derivatives as reaction partners were conducted. The alkynes that were easily derived from alanine, ibuprofen, estrone, borneol, menthol, glucose, zidovudine, and cholesterol worked well in the reactions, yielding the desired products 64–66 and 68–72 with high stereoselectivities [>20:1 diastereomeric ratio (dr)]. Additionally, the pesticide intermediate bifenthrin acid was compatible with the reaction, and the product 67 was obtained in 89% yield with >20:1 dr. The scale-up reactions of compounds 10 and 48 demonstrated the scalability of the process without affecting the yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 5A). Notably, the diaryl ketone 59 do not racemize under NaBH4 conditions to generate diastereoisomeric products 73 and 73′ separately (Fig. 5B). The absolute configuration of compound 73 was unambiguously assigned by x-ray crystallographic analysis. The chiral diarylketone 74 was obtained in 93% yield and 92% ee; subsequent reduction and protection of the phenol hydroxyl, and esterification with L-N-Boc-alanine gave 76 (3 steps, 52% yield, >20:1 dr). 76 was subsequently deprotected with HCl in dioxane to give amine hydrochloride salt, followed by (PyBOP)-mediated amide coupling of picolinic acid derivative 77, then acetylation with acetic anhydride furnished a chiral analogue of florylpicoxamid 78 (3 steps, 63% yield, >20:1), a picolinamide fungicide from Corteva Agriscience (Fig. 5C) (54). Interestingly, (R)-38 and (S)-38′ yielded all four stereoisomers of 2-(diarylmethyl)oxirane 79 in good yields with excellent enantioselectivities by two simple steps of conversion, which were important synthetic intermediates of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist (55). Notably, we prepared chiral OH analogue of BRL-15572, an antidepressant from GlaxoSmithKline (56). This is the first report for asymmetric catalytic synthesis of BRL-15572 analogues (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 4. The functionalization of complex molecules derived from natural products and pharmaceuticals.

Fig. 5. Synthetic applications.

(A) Scale-up reactions. (B) Reduction of compound 59. (C) Asymmetric synthesis of florylpicoxamid analog. (D) Stereodivergent synthesis of 2-(diarylmethyl)oxirane and BRL-15572 analogs.

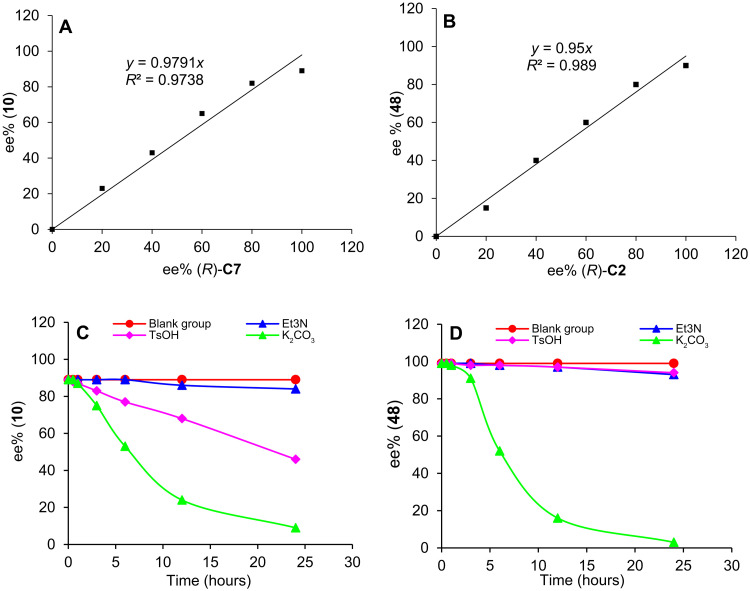

Several control experiments were performed to elucidate the mechanism of the reaction. Studies on the nonlinear effect of the enantioselectivities of compounds 10 and 48 were conducted (Fig. 6, A and B). The ee values of these compounds were linearly correlated to that of the catalyst, suggesting that the enantio- determining transition state is likely to be mediated by one catalyst molecule. The configurational stability of the chiral α,α-diarylketone products was crucial for their application. Under various basic and acidic conditions, racemization studies of shown in Fig. 6 (C and D), the ee values for both compounds 10 and 48 did not considerably decrease in the presence of NEt3 (1 equiv) for 24 hours. Contrary to 48, compound 10 underwent quick racemization under TsOH (1 equiv) conditions, with an ee value of just 46% after 24 hours. Notably, both 10 and 48 were unstable in the presence of the inorganic base K2CO3. These results explain the ineffectiveness of the asymmetric transition metal–catalyzed α-arylation of ketone, which is considered as the most direct means of synthesizing the chiral α,α-diarylketones (57–59).

Fig. 6. Control experiments.

(A) Nonlinear effect study of 10. (B) Nonlinear effect study of 48. (C) Racemization studies of 10. (D) Racemization studies of 48.

The following is a description of the proposed reaction mechanism (Fig. 7). In the presence of blue light, arylalkyne 1 and benzoquinone 2 undergo [2+2] cycloaddition to form a biradical intermediate, forming spiroepoxirane I. The stability of the benzyl radical in unsymmetrical internal alkynes partly explains the observed regioselectivities (Figs. 2 to 4; 4 to 60 and 64 to 72, >20:1 rr; 61 to 63′, 1.7:1 to 2.2:1 rr). The spirocyclic intermediate I is unstable and rapidly converts to the relatively more stable α,β-unsaturated ketone intermediate [para-quinone methide (p-QM)] (60–62) II by inverse electrocyclization. The additional electron-withdrawing β-cyclohexadiene ketone group reverses the electronic property of the α-position of intermediate II. A stereoselective α-addition of hydride donor to Si-face of II affords the final chiral α,α-diarylketones (for the detailed mechanistic investigation, see the Supplementary Materials).

Fig. 7. Proposed reaction pathways.

To decipher how the stereoselectivity of hydride transfer from Hantzsch ester 3f to the p-QM intermediate II is controlled, the corresponding transition states (TSs) for the formations of 4 and 48 in the presence of catalysts (R)-C7 and (R)-C2, respectively, were calculated by density functional theory (DFT) (63–69). The structures with key interactions indicated and the relative free energies between Re-face and Si-face hydride transfers are given in Figs. 8 and 9. For both catalysts, the Si-face hydride transfer, which leads to the formation of R configuration product, is more favorable in free energy [2.2 kcal/mol for (R)-C7 and 1.8 kcal/mol for (R)-C2] than the Re-face hydride transfer, consistent with the experimental observation. In these transition structures, Hantzsch ester 3f and the p-QM intermediate II form hydrogen bonds with the phosphate group and interact with each other through π-π interaction between the p-QM quinonyl ring and the phenyl ring of 3f, and the p-QM quinonyl ring interacts with the side chain of the catalyst through C─H•••π interactions (Fig. 8) or π-π interaction (Fig. 9). These common interactions do not contribute to the stereoselectivity but stabilize the conformation of TS. For catalyst (R)-C7 (Fig. 8), TS-C7-Re has one additional favorable C─H•••π interaction between the inward O-methyl of 3f and the phenyl ring of p-QM, while TS-C7-Si has two additional favorable weak interactions, i.e., π-π interaction between the carbonyl of p-QM and the ester carbonyl of 3f and C─H•••π interaction between the outward O-methyl of 3f and the phenyl ring of p-QM. Similar is the case for catalyst (R)-C2, where TS-C2-Re has one additional favorable weak interaction, while TS-C7-Si has three additional favorable weak interactions (Fig. 9). Obviously, the weak interactions in the Si-face TSs are stronger than those in the Re-face TSs, explaining why the Si-face TSs are lower in energy than the Re-face TSs. In addition, the interaction region indicator (IRI) analyses (Figs. 8 and 9, third column) also suggest that the n-Bu groups of 3f have favorable van der Waals interactions with the back and side chain of the catalysts, which may stabilize the conformation of hydride transfer TSs and thus favors the stereocontrol (Table 1).

Fig. 8. DFT-calculated stereo-determining transition structures for the formation of 4 catalyzed by (R)-C7.

The first row is for the hydride transfer from Hantzsch ester 3f to the Re-face of p-QM intermediate and the second row to the Si-face. The third column visualizes the interactions by the IRI method, where negative values indicate favorable and positive values indicate unfavorable, and the different interactions between the two TSs are shown in the inserted graphs. The relative free energies and enthalpies (in parentheses) at 213.15 K are also given in kilocalories per mole.

Fig. 9. DFT-calculated stereo-determining transition structures for the formation of 48 catalyzed by (R)-C2.

The first row is for the hydride transfer from Hantzsch ester 3f to the Re-face of p-QM intermediate and the second row to the Si-face. The third column visualizes the interactions by the IRI method, where negative values indicate favorable and positive values indicate unfavorable, and the different interactions between the two TSs are shown in the inserted graphs. The relative free energies and enthalpies (in parentheses) at 213.15 K are also given in kilocalories per mole.

DISCUSSION

In conclusion, an efficient and enantioselective visible light photoactivation/phosphoric acid–catalyzed ACM/transfer hydrogenation one-pot reaction of arylalkyne, benzoquinone, and Hantzsch ester was developed. In this protocol, three separate bonds are formed simultaneously, yielding an extensive range of asymmetric ketones containing α-diarylmethine chiral centers even under mild reaction conditions. Moreover, the reaction provides a convenient and practical method to modify complex bioactive molecules, including florylpicoxamid, 2-(diarylmethyl)oxirane, and BRL-15572 analogs. In addition, computational mechanistic studies were used to elucidate the origin of the stereoselectivity. Further investigations applying this protocol are ongoing in our laboratory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents were purchased commercially and used without further purification. All products were purified by flash column chromatography using 200- to 300-mesh silica gel as stationary phase. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum was recorded on Bruker AVANCE III HD 500 (500 MHz), using CDCl3 and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–d6, and MeD3OD chemical shifts were denoted in parts per million (ppm) (δ) and calibrated by using residual undeuterated solvent CHCl3 (7.27 ppm for 1H NMR, 77.00 ppm for 13C{1H} NMR), Me4Si (0.00 ppm), DMSO-d6 (2.50 ppm for 1H NMR, 39.5 ppm for 13C{1H} NMR), and MeOD-d4 (3.31 ppm for 1H NMR, 49.00 ppm for 13C{1H} NMR) as internal reference. High-resolution mass spectral analysis data were obtained using an Orbitrap instrument equipped with electrospray ionization source. The ee values of the products were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis performed on a Waters Breeze 2 HPLC system using a chiral column as noted for each compound. Optical rotations were measured on Anton Paar MCP 200 with [α]D values reported in degrees; concentration is in g/100 ml. The starting material of commercial reagents was purchased from Energy Chemical, Adamas Reagent Ltd., and Bidepharm and used as received.

General procedure

A solution of aryl alkynes (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and benzoquinone (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (2 ml) under nitrogen atmosphere was irradiated under commercially available blue LEDs (70 W, 2 × 35 W) for 4 hours at room temperature, and then the reaction mixture was cooled to −60°C. 4 Å MS (60 mg), (R)-C7 or (R)-C2 (0.005 mmol, 5 mol %), and Hantzsch ester 3f (0.15 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were added to the reaction mixture sequentially. The resulting mixture was stirred vigorously at −60°C for 3 hours. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was subjected to silica gel column chromatography directly (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 3:1 to 10:1) to obtain the pure products.

Acknowledgments

Funding: We acknowledge financial support from the NSFC (22101213, 81925037, and 32070042), Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2021KQNCX101, 2020KCXTD036, and 2021KCXTD001), Hong Kong–Macao Joint Research and Development Fund of Wuyi University (2021WGALH12), National High-level Personnel of Special Support Program (2017RA2259, China), the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (2022B1515020080, China), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0903200/2018YFA0903201, China), and Guangdong International Science and Technology Cooperation Base (2021A0505020015, China).

Author contributions: X.-Z.Z. conceived and directed the project. H.-F.L. performed experiments and prepared the Supplementary Materials. Z.-Q.Z., T.-F.W., Y.-R.Z., and H.-P.P. helped collecting some new compounds and analyzing the data. L.L., Y.-H.W., and H.G. performed the DFT calculations and drafted the DFT parts. X.-Z.Z. and Y.-H.W. wrote the paper. A.-J.M. and J.-B.P. discussed the results. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. For x-ray crystallographic data for 9, 54, and 73, see tables S7 to S9.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Fig. S1

Tables S1 to S9

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.T. Jia, P. Gao, J. Liao, Enantioselective synthesis of gem-diarylalkanes by transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric arylations (TMCAAr). Chem. Sci. 9, 546–559 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.M. Sankalan, R. Deblina, P. Gautam, Overview on the recent strategies for the enantioselective synthesis of 1, 1-diarylalkanes, triarylmethanes and related molecules containing the diarylmethine stereocenter. ChemCatChem 10, 1941–1967 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.M. Belal, Z. Li, X. Lu, G. Yin, Recent advances in the synthesis of 1,1-diarylalkanes by transition-metal catalysis. Sci. Chi. Chem. 64, 513–533 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.S.-Y. Wu, Y.-H. Fu, Q. Zhou, M. Bai, G.-Y. Chen, C.-R. Han, X.-P. Song, Biologically active oligostilbenes from the stems of Vatica mangachapoi and chemotaxonomic significance. Nat. Prod. Res. 33, 2300–2307 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Y.-C. He, C. Peng, X.-F. Xie, M.-H. Chen, X.-N. Li, M.-T. Li, Q.-M. Zhou, L. Guo, L. Xiong, Penchinones A–D, two pairs of cis-trans isomers with rearranged neolignane carbon skeletons from Penthorum chinense. RSC Adv. 5, 76788–76794 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.K. Andries, P. Verhasselt, J. Guillemont, H. W. H. Göhlmann, J.-M. Neefs, H. Winkler, J. V. Gestel, P. Timmerman, M. Zhu, E. Lee, P. Williams, D. D. Chaffoy, E. Huitric, S. Hoffner, E. Cambau, C. Truffot-Pernot, N. Lounis, V. Jarlier, A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 307, 223–227 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.L. Buzzetti, M. Puriņš, P. D. G. Greenwood, J. Waser, Enantioselective carboetherification/hydrogenation for the synthesis of amino alcohols via a catalytically formed chiral auxiliary. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17334–17339 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.J. A. Clark, M. S. G. Clark, D. V. Gardner, L. M. Gaster, M. S. Hadley, D. Miller, A. Shah, Substituted 3-amino-1,1-diaryl-2-propanols as potential antidepressant agents. J. Med. Chem. 22, 1373–1379 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.B. Xu, M.-L. Li, X.-D. Zuo, S.-F. Zhu, Q.-L. Zhou, Catalytic asymmetric arylation of α-aryl-α-diazoacetates with aniline derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8700–8703 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.G. Xu, M. Huang, T. Zhang, Y. Shao, S. Tang, H. Gao, X. Zhang, J. Sun, Asymmetric arylation of diazoesters with anisoles enabled by cooperative gold and phosphoric acid catalysis. Org. Lett. 24, 2809–2814 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.X.-S. Liu, Z. Tang, Z.-Y. Si, Z. Zhang, L. Zhao, L. Liu, Enantioselective para-C(sp2)-H functionalization of alkyl benzene derivatives via cooperative catalysis of gold/chiral brønsted acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208874 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.B. Li, M. A. Aliyu, Z. Gao, T. Li, W. Dong, J. Li, E. Shi, W. Tang, General synthesis of chiral α,α-diaryl carboxamides by enantioselective palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling. Org. Lett. 22, 4974–4978 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D. Tian, C. Li, G. Gu, H. Peng, X. Zhang, W. Tang, Stereospecific nucleophilic substitution with arylboronic acids as nucleophiles in the presence of a CONH group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7176–7180 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Y.-J. Hao, X.-S. Hu, Y. Zhou, J. Zhou, J.-S. Yu, Catalytic enantioselective α-arylation of carbonyl enolates and related compounds. ACS Catal. 10, 955–993 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Z. Huang, Z. Liu, J. S. Zhou, An enantioselective, intermolecular α-arylation of ester enolates to form tertiary stereocenters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 15882–15885 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Z. Huang, L. H. Lim, Z. Chen, Y. Li, F. Zhou, H. Su, J. S. Zhou, Arene CH-O hydrogen bonding: A stereocontrolling tool in palladium-catalyzed arylation and vinylation of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 4906–4911 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A. H. Cherney, N. T. Kadunce, S. E. Reisman, Catalytic asymmetric reductive acyl cross-coupling: Synthesis of enantioenriched acyclic α,α-disubstituted ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7442–7445 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.M. Escudero-Casao, G. Licini, M. Orlandi, Enantioselective α-arylation of ketones via a novel Cu(I)−bis(phosphine) dioxide catalytic system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 3289–3294 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.P. M. Lundin, J. Esquivias, G. C. Fu, Catalytic asymmetric cross-couplings of racemic α-bromoketones with arylzinc reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 154–156 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.S. Lou, G. C. Fu, Nickel/Bis(oxazoline)-catalyzed asymmetric kumada reactions of alkyl electrophiles: Cross-couplings of racemic α-bromoketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1264–1266 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Q. Zhang, K. Liang, C. Guo, Asymmetric electrochemical arylation in the formal synthesis of (+)-amurensinine. CCS Chem. 3, 338–347 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.C. K. Prier, D. A. Rankic, D. W. C. MacMillan, Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: Applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 113, 5322–5363 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.S. Garbarino, D. Ravelli, S. Protti, A. Basso, Photoinduced multicomponent reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15476–15484 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.L. Marzo, S. K. Pagire, O. Reiser, B. König, Visible-light photocatalysis: Does it make a difference in organic synthesis? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10034–10072 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.G. E. M. Crisenza, D. Mazzarella, P. Melchiorre, Synthetic methods driven by the photoactivity of electron donor-acceptor complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5461–5476 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.P. Melchiorre, Introduction: Photochemical catalytic processes. Chem. Rev. 122, 1483–1484 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.C. R. J. Stephenson, T. P. Yoon, D. W. C. MacMillan, Visible Light Photocatalysis in Organic Chemistry (Wiley-VCH, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.J. Du, K. L. Skubi, D. M. Schultz, T. P. Yoon, A dual-catalysis approach to enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloadditions using visible light. Science 344, 392–396 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Z. Zuo, H. Cong, W. Li, J. Choi, G. C. Fu, D. W. C. MacMillan, Enantioselective decarboxylative arylation of α-amino acids via the merger of photoredox and nickel catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 1832–1835 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.C. Chen, J. C. Peters, G. C. Fu, Photoinduced copper-catalysed asymmetric amidation via ligand cooperativity. Nature 596, 250–256 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D. A. Nicewicz, D. W. C. MacMillan, Merging photoredox catalysis with organocatalysis: The direct asymmetric alkylation of aldehydes. Science 322, 77–80 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.L. J. Rono, H. G. Yayla, D. Y. Wang, M. F. Armstrong, R. R. Knowles, Enantioselective photoredox catalysis enabled by proton-coupled electron transfer: Development of an asymmetric aza-pinacol cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17735–17738 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.J. J. Murphy, D. Bastida, S. Paria, M. Fagnoni, P. Melchiorre, Asymmetric catalytic formation of quaternary carbons by iminium ion trapping of radicals. Nature 532, 218–222 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.M. Silvi, P. Melchiorre, Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature 554, 41–49 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.R. S. J. Proctor, H. J. Davis, R. J. Phipps, Catalytic enantioselective minisci-type addition to heteroarenes. Science 360, 419–422 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.J. Jurczyk, M. C. Lux, D. Adpressa, S. F. Kim, Y.-H. Lam, C. S. Yeung, R. Sarpong, Photomediated ring contraction of saturated heterocycles. Science 373, 1004–1012 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.G. Büchi, J. T. Kofron, E. Koller, D. Rosenthal, Light catalyzed organic reactions. v.1 the addition of aromatic carbonyl compounds to a disubstituted acetylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 78, 876–877 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- 38.M. R. Becker, R. B. Watson, C. S. Schindler, Beyond olefins: New metathesis directions for synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 7867–7881 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.A. Saito, K. Tateishi, Syntheses of heterocycles via alkyne-carbonyl metathesis of unactivated alkynes. Heterocycles 92, 607–630 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.A. Das, S. Sarkar, B. Chakraborty, A. Kar, U. Jana, Catalytic alkyne/alkene-carbonyl metathesis: Towards the development of green organic synthesis. Curr. Green Chem. 7, 5–39 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 41.A. Sagadevan, V. P. Charpe, A. Ragupathi, K. C. Hwang, Visible light copper photoredox-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling of phenols and terminal alkynes: Regioselective synthesis of functionalized ketones via C≡C triple bond cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2896–2899 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.A. Sharma, V. Dixit, S. Kumar, N. Jain, Visible light-mediated in situ generation of δ,δ-disubstituted p-quinone methides: Construction of a sterically congested quaternary stereocenter. Org. Lett. 23, 3409–3414 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.E. Bosch, S. M. Hubig, J. K. Kochi, Paterno−Büchi coupling of (diaryl)acetylenes and quinone via photoinduced electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 386–395 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 44.J. Xue, Y. Zhang, X. L. Wang, H. K. Fun, J. H. Xu, Photoinduced reactions of 1-acetylisatin with phenylacetylenes. Org. Lett. 2, 2583–2586 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.L. Wang, Y. Zhang, H.-Y. Hu, H. K. Fun, J.-H. Xu, Photoreactions of 1-acetylisatin with alkynes: Regioselectivity in oxetene formation and easy access to 3-alkylideneoxindoles and dispiro[oxindole[3,2′]furan[3′,3′′]oxindole]s. J. Org. Chem. 70, 3850–3858 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Z.-W. Qiu, L. Long, Z.-Q. Zhu, H.-F. Liu, H.-P. Pan, A.-J. Ma, J.-B. Peng, Y.-H. Wang, H. Gao, X.-Z. Zhang, Asymmetric three-component reaction to assemble the acyclic all-carbon quaternary stereocenter via visible light and phosphoric acid catalysis. ACS Catal. 12, 13282–13291 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.L. Dai, J. Guo, Q. Huang, Y. Lu, Asymmetric multifunctionalization of alkynes via photo-irradiated organocatalysis. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd2574 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.M. Huang, L. Zhang, T. Pan, S. Luo, Deracemization through photochemical E/Z isomerization of enamines. Science 375, 869–874 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.C. Zheng, S.-L. You, Transfer hydrogenation with Hantzsch esters and related organic hydride donors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2498–2518 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.T. D. Giacco, E. Baciocchi, O. Lanzalunga, F. Elisei, Competitive decay pathways of the radical ions formed by photoinduced electron transfer between quinones and 4,4′ -dimethoxydiphenylmethane in acetonitrile. Chem. A Eur. J. 7, 3005–3013 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.X. Dong, W. Jiang, D. Hua, X. Wang, L. Xu, X. Wu, Radical-mediated vicinal addition of alkoxysulfonyl/fluorosulfonyl and trifluoromethyl groups to aryl alkyl alkynes. Chem. Sci. 12, 11762–11768 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.M. Isomura, D. A. Petrone, E. M. Carreira, Coordination-induced stereocontrol over carbocations: Asymmetric reductive deoxygenation of racemic tertiary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4738–4748 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O. A. Tomashenko, V. V. Grushin, Aromatic trifluoromethylation with metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 111, 4475–4521 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.N. R. Babij, N. Choy, M. A. Cismesia, D. J. Couling, N. M. Hough, P. L. Johnson, J. Klosin, X. Li, Y. Lu, E. O. McCusker, K. G. Meyer, J. M. Renga, R. B. Rogers, K. E. Stockman, N. J. Webb, G. T. Whiteker, Y. Zhua, Design and synthesis of florylpicoxamid, a fungicide derived from renewable raw materials. Green Chem. 22, 6047–6054 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.F. D. Bello, A. Bonifazi, G. Giorgioni, A. Piergentili, M. G. Sabbieti, D. Agas, M. Dell’Aera, R. Matucci, M. Górecki, G. Pescitelli, G. Vistoli, W. Quaglia, Novel potent muscarinic receptor antagonists: Investigation on the nature of lipophilic substituents in the 5- and/or 6-positions of the 1,4-dioxane nucleus. J. Med. Chem. 63, 5763–5782 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.G. C. Vidal-Cantú, M. Jiménez-Hernández, H. I. Rocha-González, C. M. Villalón, V. Granados-Soto, E. Muñoz-Islas, Role of 5-HT5A and 5-HT1B/1D receptors in the antinociception produced by ergotamine and valerenic acid in the rat formalin test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 781, 109–116 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.G. Danoun, A. Tlili, F. Monnier, M. Taillefer, Direct copper-catalyzed α-arylation of benzyl phenyl ketones with aryl iodides: Route towards tamoxifen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12815–12819 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.M. P. Drapeau, I. Fabre, L. Grimaud, I. Ciofini, T. Ollevier, M. Taillefer, Transition-metal-free α-arylation of enolizable aryl ketones and mechanistic evidence for a radical process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10587–10591 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.J.-W. Park, B. Kang, V. M. Dong, Catalytic alkyne arylation using traceless directing groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13598–13602 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Z. Wang, F. Ai, Z. Wang, W. Zhao, G. Zhu, Z. Lin, J. Sun, Organocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of 1,1-diarylethanes by transfer hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 383–389 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.M. Chen, J. Sun, How understanding the role of an additive can lead to an improved synthetic protocol without an additive: Organocatalytic synthesis of chiral diarylmethyl alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11966–11970 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Y. Mao, Z. Wang, G. Wang, R. Zhao, L. Kan, X. Pan, L. Liu, Redox deracemization of tertiary stereocenters adjacent to an electron-withdrawing group. ACS Catal. 10, 7785–7791 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 63.A. D. Becke, Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 64.C. Lee, W. Yang, R. G. Parr, Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.W. J. Hehre, R. Ditchfield, J. A. J. Pople, Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of Gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic. MoleculesChem. Phys. 56, 2257–2261 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 66.A. V. Marenich, C. J. Cramer, D. G. Truhlar, Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.R. F. Ribeiro, A. V. Marenich, C. J. Cramer, D. G. Truhlar, Use of solution-phase vibrational frequencies in continuum models for the free energy of solvation. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 14556–14562 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.C. Gonzalez, H. B. Schlegel, An improved algorithm for reaction path following. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 2154–2161 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 69.T. Lu, Q. Chen, Interaction region indicator: A simple real space function clearly revealing both chemical bonds and weak interactions. Chem.-Methods 1, 231–239 (2021). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Fig. S1

Tables S1 to S9