Abstract

Background

Despite advances in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research and the vast genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data available, there are still controversies regarding the pathways and molecular signatures underlying the neurodevelopmental disorders leading to ASD.

Purpose

To delineate these underpinning signatures, we examined the two largest gene expression meta-analysis datasets obtained from the brain and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 1355 ASD patients and 1110 controls.

Methods

We performed network, enrichment, and annotation analyses using the differentially expressed genes, transcripts, and proteins identified in ASD patients.

Results

Transcription factor network analyses in up- and down-regulated genes in brain tissue and PBMCs in ASD showed eight main transcription factors, namely: BCL3, CEBPB, IRF1, IRF8, KAT2A, NELFE, RELA, and TRIM28. The upregulated gene networks in PBMCs of ASD patients are strongly associated with activated immune-inflammatory pathways, including interferon-α signaling, and cellular responses to DNA repair. Enrichment analyses of the upregulated CNS gene networks indicate involvement of immune-inflammatory pathways, cytokine production, Toll-Like Receptor signalling, with a major involvement of the PI3K-Akt pathway. Analyses of the downregulated CNS genes suggest electron transport chain dysfunctions at multiple levels. Network topological analyses revealed that the consequent aberrations in axonogenesis, neurogenesis, synaptic transmission, and regulation of transsynaptic signalling affect neurodevelopment with subsequent impairments in social behaviours and neurocognition. The results suggest a defense response against viral infection.

Conclusions

Peripheral activation of immune-inflammatory pathways, most likely induced by viral infections, may result in CNS neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to abnormalities in transsynaptic transmission, and brain neurodevelopment.

Keywords: Neuro-immune, Cytokines, Mitochondria, Inflammation, Neuroinflammation, Autism

Highlights

-

•

Two gene expression meta-analyses data sets were examined in ASD in conjunction with protein biomarkers and gene mutations.

-

•

Transcriptional cofactors and potential master gene networks were identified with RELA and IRF1 being the top two key targets.

-

•

Viruses may induce alterations in immune-inflammatory, carbon metabolism, proteolysis, and DNA repair gene networks in ASD.

-

•

According to annotation analyses, these pathways may arise from viral infections.

-

•

Peripheral immune activation may result in neuroinflammation and mitochondrial and transsynaptic signaling dysregulation.

-

•

These conditions may induce neurodevelopmental disorders that lead to the behavioral and cognitive impairments in ASD.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication and by repetitive stereotyped behaviours that develop in early childhood and lead to clinically substantial impairment (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of). Since its first description about 80 years ago, and despite the hundred thousand research papers published on the topic, ASD still remains a puzzle in terms of molecular mechanisms and gene function. The state of the art current research regards ASD as a systemic disease due to intertwined aberrations in immune-inflammatory pathways, mitochondrial and gastrointestinal functions, and the impact of environmental and epigenetic factors (Gevezova et al., 2020; Rossignol and Frye, 2012a; Ormstad et al., 2018; Havdahl et al., 2021).

A plethora of genetic, neuroinflammatory and metabolic pathways are involved in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of ASD. Approximately 600–1200 genes and genomes are associated with ASD, including single-nucleotide polymorphisms (∼5%), copy number variations (∼10%) and mutations in noncoding sequences such as introns and intergenic regions (De Rubeis and Buxbaum, 2015).<InternetLink> Genome-wide studies and transciptome analyses revealed downregulation of synapse-related genes and upregulation of microglia and immune-related genes in the brains of autistic patients (Gupta et al., 2014; Parikshak et al., 2016). The epigenetic landscape in ASD is also quite diverse. The Autism Epigenome-Wide Association Study meta-analysis performed in blood from children and adolescents identified five differentially methylated brain-based positions associated with autism (Andrews et al., 2018). Conversely, another study on a smaller cohort showed that DNA methylation patterns are unable to distinguish the target group from healthy controls (Siu et al., 2019). Therefore, a combination of genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information is needed for better elucidating the molecular pathophysiology of ASD. Another important issue to be considered when interpreting expression analyses is the discrepancy between data obtained from peripheral blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and CNS, as most genes have a tissue-specific mode of expression and regulation. The blood-derived transcriptome is not necessarily representative of the gene expression profile in the brain, or of the phenotype of autistic individuals.

Whole-genome transcriptome studies on post-mortem brain tissues revealed significantly disrupted pathways related to synaptic connectivity, neurotransmitter, neuron projection and vesicles, and chromatin remodeling pathways (Voineagu et al., 2011; Gordon et al., 2021). Upregulated genes implicated in immune processes associated with hypomethylation were also detected in the autistic brain (Ramaswami et al., 2020). Neuroinflammation and immune dysfunction are other factors attributed to gene-environmental interactions in ASD. Inflammatory molecular signaling pathways in both the CNS and the periphery can influence brain connections and synaptic function by affecting components including microglia, cytokines and their receptors, Toll-like receptors (TLR), MET receptors, and major histocompatibility complex class I molecules (Estes and McAllister, 2015; Jiang et al., 2022). Innate and adaptive immunity, represented by the various cell types involved (including microglia), as well as cellular and humoral immune responses, are involved in ASD. Since 2002, when Croonenberghs et al. (2002) (Croonenberghs et al., 2002) suggested that autism may be accompanied by an activation of the monocytic (increased IL-1RA) and Th-1-like (increased IFN-gamma) arms of the inflammatory response system, it is known that immune mediators are implicated in this neurodevelopmental condition (Croonenberghs et al., 2002). Cytokine-mediated neuroinflammation is operated under the control of proinflammatory cytokines secreted by maternal cells during pregnancy due to infections or allergies and/or by proinflammatory cytokines released by the fetal brain leading to abnormal neurodevelopment (Robinson-Agramonte et al., 2022). Different cytokines are associated with various clinical phenotypes and with comorbidities in autistic children (Reale et al., 2021; Nazeen et al., 2016; Sotgiu et al., 2020).

The normal functioning of the immune system and the CNS, like many other energy-demanding tissues in the human body, are tightly dependent on cellular metabolism, with mitochondria being the main players. Inflammatory mediators produced by activated microglial and infiltrated immune cells elicit intracellular processes that can alter mitochondrial functions, eventually leading to neurodegeneration. Oxidative stress, as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired endogenous antioxidant mechanisms, can disrupt the fine balance between mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy of damaged mitochondria (Gevezova et al., 2020; Maes et al., 2019).

Recent studies in ASD children showed increased respiratory reserve capacity and maximal respiration, and an altered adaptive response to oxidative stress. In addition, а strong dependence on fatty acids and impaired ability to reprogram cell metabolism was shown (Gevezova et al., 2021). Not only mitochondrial respiration and energy homeostasis are altered in autism (Gevezova et al., 2022), but hypernitrosylation and chronic nitro-oxidative stress may inhibit cellular antioxidant systems and affect mitochondrial functions and immune cell metabolism (Morris et al., 2022). Variations in mtDNA copy numbers and alterations in genes coding for electron transport chain (ETC) components are also supporting mitochondrial dysfunction as an integral part of the ASD pathogenetic puzzle (Balachandar et al., 2021). Therefore, it may be hypothesized that activated immune-inflammatory and nitro-oxidative stress pathways, and mitochondrial dysfunctions are interconnected in triggering ASD pathogenesis and symptom severity. Evidence for this hypothesis is the reported deregulated enzyme antioxidant network and the increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, IL-17A) generated by innate immune and B cells in children with autism, as well as the activated inflammatory pathways (NFk, TLR4) and increased oxidative/nitrative stress (Nadeem et al., 2018, 2019a, 2019b, 2020a; Al-Harbi et al., 2020).

Despite the dramatic advances in autism research and especially the vast genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data available, there are still controversies regarding gene expression in the CNS and periphery and its relevance to ASD diagnosis and ultimate treatment.

The present review summarizes current state-of-the-art insights into the molecular pathophysiology of ASD. We present data based on the analysis of downregulated and upregulated transcripts in the brain and the peripheral blood of younger (age range: 5.1 ± 3.8 years old for blood samples, and 2–56, 5–51 and 2–39 years old for the 3 studies of post-mortem brain gene expression) autistic individuals.

2. Methods

In attempt to elucidate the potential causes of ASD, as well as the molecular mechanisms and cellular processes that may be underlying the pathology of this condition, we carried out an integrated analysis combining a number of transcriptomic studies with a curated list of protein biomarkers and analysis of known mutated genes (Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3).

We used the results from the 2 largest meta-analysis datasets (He et al., 2019; Tylee et al., 2017) encompassing a total of 14 different investigations of gene expression. Tylee et al. performed their meta-analysis on 7 previous studies of whole blood or lymphocytes (comprising 626 ASD samples and 447 control samples, 19,3% female, median age of 5,1 ± 3,8 years). The inclusion criteria comprised: studies with data obtained from Affymetrix or Illumina microarray platforms to ensure consistent processing and analysis. The authors excluded studies that examined unaffected relatives as controls of ASD patients, studies using immortalised lymphocytes, and studies without control samples (Tylee et al., 2017).

He et al. had similar inclusion criteria: human samples comprising both ASD patients and healthy controls (composed of 729 ASD samples and 663 control samples). However, no data were found on median age and sex distribution in this study (He et al., 2019). Datasets obtained from skin fibroblast iPSCs or cell lines were excluded in our analysis, as well as data where fold change differences were not readily available, leaving us with 3 brain data sets (GSE28475, GSE38322, and GSE28521) and 5 blood data sets (GSE26415, GSE25507, GSE18123, GSE29691, and GSE42133). Manually extracted data from these studies on age (if available in the original publications) showed considerable heterogeneity, while we found that the samples were predominantly collected from male patients (around 80%), which is in accordance with the epidemiology data for ASD.

By deconstructing these 2 datasets based on the type of samples obtained from children with ASD, we first analysed the changes that occur in the brain (a total of 3 datasets with over 71 samples, accession numbers GSE28475, GSE28521, GSE38322). We identified 1585 upregulated and 135 downregulated genes (cut off of p ≤ 0.05 and FC ≥ 1). Of the data obtained from peripheral blood cells (11 different studies with more than 1000 samples, accession numbers GSE18123.1, GSE18123.2, GSE25507, GSE29691, GSE42133, GSE26415, GSE6575 and others without a GEO number), there were 1003 upregulated and 1688 downregulated transcripts. Differentially expressed proteins from the literature search (total of 120 from 21 studies) were also divided into two groups, namely: up and down-regulated proteins, and were analysed together with the above mentioned 4 subgroups (up- and down-regulated genes in the brain, and up- and down-regulated genes in the blood) to obtain an integrated analysis of causality in ASD. A list of mutated genes in ASD was created from the SFARI database. The methods used to define transcription factor and gene networks and clusters, as well as the annotation and enrichment analyses are summarized in Table 1. (Maes et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2022).

Table 1.

Summary of the methods used to define transcription factor and gene networks and clusters and perform annotation and enrichment analyses.

| Method | Resource | Citation/link |

|---|---|---|

| Extract tight networks from the upregulated and downregulated genes, either in blood or brain tissues, alone or together | STRING | STRING: functional protein association networks (string-db.org) |

| Define clusters in the gene sets or networks | MCL Clustering (STRING) | STRING: functional protein association networks (string-db.org) |

| Computation of the network or cluster characteristics | STRING | STRING: functional protein association networks (string-db.org) |

| Cytoscape plugin Network Analyzer | Cytoscape: An Open Source Platform for Complex Network Analysis and Visualization | |

| Transcription factor network and enrichment analysis in up- and down-regulated factors in brain tissue and blood | ClusterProfiler, enricher function | (Yu et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2021) |

| CHEA Transcription Factor Targets dataset | Lachmann et al. (2010) | |

| ENCODE Transcription Factor Targets dataset | Consortium (2011) | |

| Visualization of the networks, clusters | STRING | STRING: functional protein association networks (string-db.org) |

| Metascape | Metascape | |

| ClusterProfiler | (Yu et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2021) | |

| GO enrichment map network of the top GO terms in all genes | ClusterProfiler, enrichGo function | (Yu et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2021) |

| Enrichment and annotation analysis of the gene networks and visualization | Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathways | KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| REACTOME pathways (the European Bio-Informatics Institute Pathway Database) | Pathway Browser - Reactome Pathway Database | |

| OmicsNet 2.0 | OmicsNet | |

| Metascape | Metascape | |

| Delineate smaller molecular complexes and visualize enriched ontology clusters | Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) | Metascape |

| Comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis using Enrichr | Enrichr | Enrichr (maayanlab.cloud) |

| PANTHER (gene list analysis) | www.pantherdb.org | |

| WikiPathways | Home | WikiPathways | |

| GO cellular components | Gene Ontology overview | |

| GO biological process | Gene Ontology overview | |

| Descartes cell types and tissues | Enrichr (maayanlab.cloud) | |

| Visualization (heatmaps) of the Enrichr enrichment and annotation analysis | Appyters | Appyters (maayanlab.cloud) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification of cofactor genes (possible master-regulators) in ASD

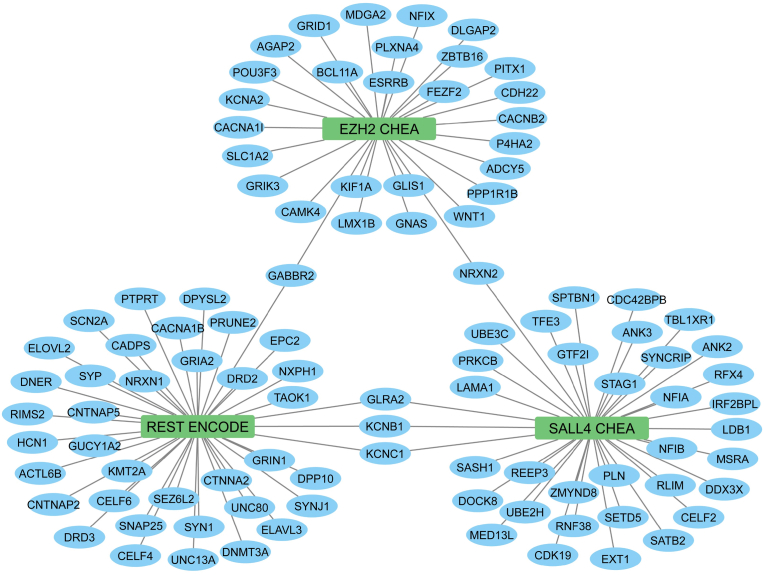

To identify transcription cofactors that may regulate the pathogenic processes and events in ASD, we performed functional enrichment analysis using the ENCODE and ChEA transcription factor gene sets (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Transcription factor networks in differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of ASD patients. The middle nodes are transcription factors, and the blue nodes are coding genes. Edges represent the memberships of the coding genes in the ChEA transcript factor gene sets. The enrichment analysis was conducted in R using the ClusterProfiler package with the enricher function. One-sided Fisher's exact test was utilized, and the p-values were adjusted via Benjamini-Hochberg correction with a significance threshold set at 0.05. Three major nodes in the figure are EZH2 (Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb prepressive complex 2 subunit) from the CHEA Transcription Factor Targets dataset (Lachmann et al., 2010), REST (RE1-silencing transcription factor) from the ENCODE Transcription Factor Targets dataset (Consortium, 2011), and SALL4 (Spalt-like transcription factor 4) from the CHEA Transcription Factor Targets dataset (Lachmann et al., 2010). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The library named ENCODE_and_ChEA_Consensus_TFs_from_ChIP-X was downloaded from https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/#libraries and used for the analysis. This library consists of 104 terms with 15562 gene coverage. The enrichment analysis was performed by ClusterProfiler and used the defined transcription factor dataset of ENCODE with two different sets of ASD genes. The first set contains all 1022 genes, which have been found to be mutated in ASD, and the second set consists of 4079 genes from the two meta-analysis studies described above and from the Reactome analysis based on the STRING network (Evidence = 0.9, no text mining). Both sets of genes were visualized as gene networks, shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, respectively. The results show that genes in the first set significantly overlap with genes regulated by Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2), Spalt-like transcription factor 4 (SALL4), and RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST).

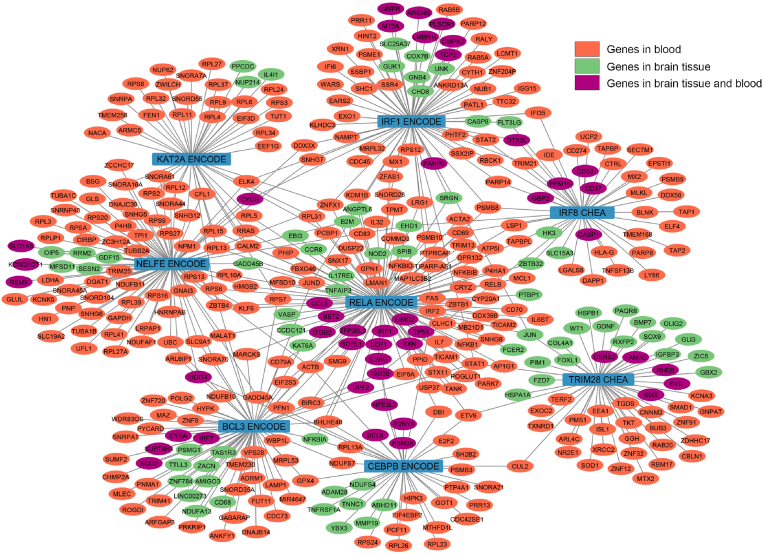

Fig. 2.

Transcription factor network in up- and down-regulated genes in brain tissue and blood in ASD patients. The middle blue nodes are transcription factors. The nodes coloured in orange represent coding genes identified in blood samples, whereas the green nodes correspond to coding genes discovered in brain tissue. Additionally, the violet nodes denote coding genes that are present in both blood and brain tissue. Edges represent the memberships of the target genes of the transcription factors in the CHEA (Lachmann et al., 2010) or ENCODE (Consortium, 2011) transcript factor gene sets. The enrichment analysis was conducted in R using the ClusterProfiler package with the enricher function. One-sided Fisher's exact test was utilized, and the p-values were adjusted via Benjamini-Hochberg correction with a significance threshold set at 0.05. Eight main transcription factors are BCL3 (B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3), CEBPB (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein), IRF1 (Interferon regulatory factor 1), IRF8 (Interferon regulatory factor 8), KAT2A (lysine acetyltransferase 2A or GCN5), NELFE (Negative elongation factor complex member E), RELA (V-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A or transcription factor p65), and TRIM28 (Tripartite motif containing 28). KAT2A and NELFE are the transcription factors mostly involved with significant genes in blood, while the others target significant genes in either blood or in brain tissue. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The EZH2 gene encodes the EZH2 enzyme, that plays a role in histone methylation and, therefore, transcriptional repression. Importantly, the EZH2 enzyme is a component of the Polycomb Repressive Complex (PRC2) and the Polycomb-Group (PcG) family. The latter form multimeric protein complexes that maintain the transcriptional repressive state of genes over successive cell generations, whilst PRC2 mediates the epigenetic maintenance of diverse genes that regulate differentiation and embryonic development (Morey and Helin, 2010). Moreover, EZH2 associates with the X-linked nuclear protein, which plays a key role the CNS and hematopoietic cells as well, and associates with the VAV1 oncoprotein, an embryonic ectoderm development protein [provided by RefSeq, Feb 2011] (NCBI Entrez Gene Database, 2146).

The REST gene restricts neuronal gene expression and, additionally, represses neuronal genes in non-neuronal tissues, and inhibits transcription by binding the neuron-restrictive silencer element. REST is present in undifferentiated neuronal progenitor cells, and may function as a master negative regulator of neurogenesis [provided by RefSeq, Jul 2010] (NCBI Entrez Gene Database,5978).

SALL4 is a transcription factor that is involved in the self-renewal of hematopoietic and embryonic stem cells. SALL 4 plays a role in early development, and SALL4 heterogenous mice have neural and heart defects. Defects in this gene are a cause of Duane-radial ray syndrome (DRRS). [provided by RefSeq, Jul 2008] (NCBI Entrez Gene Database, 57167).

In addition, we found that autism-associated genes from dataset 2 significantly overlap with genes regulated by Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1), K(lysine) acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A), Interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8), Negative elongation factor complex member E (NELFE), V-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A (RELA), Tripartite motif containing 28 (TRIM28), B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3 (BCL3) and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta (CEBPB). Fig. 2 shows that we found 8 subclusters in 412 genes, including IRF1 ENCODE, KAT2A ENCODE, IRF8 CHEA, NELFE ENCODE, RELA ENCODE, TRIM28 CHEA, BCL3 ENCODE, and CEBPB ENCODE.

IRF1 regulates IFN and IFN-inducible genes, the response to bacterial and viral infections, many genes expressed during immune-inflammatory responses and haematopoiesis, cell differentiation and proliferation, and the regulation of cell cycle growth arrest and programmed cell death in response to DNA damage. IRF8 binds to the upstream regulatory region of type I IFN and IFN-inducible MHC class I genes and regulates immune system functions. RELA (transcription factor p65; nuclear factor NF-Kappa-B P65 subunit, or V-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog) is induced by many stimuli, including cell growth, inflammation, immunity, and differentiation, and may cause hyperinflammation. BCL3 (B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3) interacts with NFKB1 and NFBB2, thereby forming a regulatory loop that mediates the nuclear residence of p50 NF-kappa B. CEBPB (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein) is a key factor in macrophage functions and the regulation of immune-inflammatory, cytokine, and acute phase genes. KAT2A (lysine acetyltransferase 2A) functions as a histone acetyltransferase (HAT) to promote transcriptional activation. NELFE (negative elongation factor complex member E) is and essential component of the NELF complex, which negatively regulates the elongation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. The NELF complex acts via an association with the DSIF complex and causes transcriptional pausing. TRIM28 (tripartite motif containing 28 or transcriptional intermediary factor 1-beta) mediates many critical functions, including transcriptional regulation, cellular differentiation and proliferation, DNA damage repair, viral suppression, and apoptosis. Its functionality is dependent upon post-translational modifications (STRING, 2022).

3.2. Differentially expressed genes in the brain

3.2.1. Analysis of genes upregulated in the brain

Electronic supplementary file (ESF) Table 1 shows the network characteristics of the first cluster extracted from the upregulated transcripts in the brains of ASD patients computed using STRING and the Cytoscape plugin Network Analyzer. This network comprises 247 nodes, 1965 edges (exceeding the expected number of edges (n = 689; PPI-enrichment p < 10 e−16), average node degree = 15.9, and an average local clustering coefficient = 0.536). The top 10 hubs (nodes with the highest degree) were in descending order of importance: IL6 (degree = 89), TP53 (78), JUN (66), CD44 (60), CXCL10 (58), CCL3 (49), IFNB1 (46), IL13 (45), ITGB2 (45) and SYK (44). The top 3 bottlenecks (nodes with the highest betweenness centrality) are in descending order of importance: TP53 (0.1850), IL6 (0.0910) and JUN (0.0827) and the top 3 non-hub bottlenecks are in descending order of importance: HBB (0.0402), RELA (0.0402), and HIST2H2BE (0.0340).

As discussed previously (Maes et al., 2021a, 2021b), the backbone of a cluster extracted from the upregulated brain transcripts consists of the hubs and the non-hub bottlenecks. Thus, the top 3 backbone nodes are IL6 (interleukin-6, a key immune-inflammatory cytokine), TP53 (tumour protein 53, that plays a key role in tumor suppression and brain development), and JUN (transcription factor JUN, a FOS-binding protein that plays a key role in neuronal differentiation and cell death) (Schlingensiepen et al., 1994). Consequently, we have performed annotation and enrichment analyses using all network differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). We found a remarkably strong overrepresentation of immune system functions in the upregulated brain transcripts. ESF Figs. 1–4 show the results of enrichment and annotation analyses (using Metascape, and Panther, WikiPathway, 2021 Human, Descartes Cell Types, and Tissue, 2021 in Enrichr, visualized using Appyters) showed that cytokine signaling and activation of the inflammatory response system in the brain were the most significant paths enriched in the network of upregulated brain DEPs.

This is not surprising, as there are several cytokines involved in the etiology and/or pathogenesis of ASD, which are reoccurring in literature. Examples include IL-1, IL-6, TNFα, IFN-γ and others (Xu et al., 2015). Some of these cytokines have been proposed to serve as biomarkers or predictors of prognosis or progression (Ashwood et al., 2011), and some are associated with predisposition to ASD (as with SNPs in the IL-1 gene (Estes and McAllister, 2015). The general finding of an activated immune response in the brain to an unknown entity/agent has been known for over a decade (Voineagu et al., 2011; Ginsberg et al., 2012). Voineagu et al. (2011) (Voineagu et al., 2011) demonstrated through RNA-seq and comparison to GWAS (genome-wide association studies) that there is a strong enrichment for an immune-glial module, which is not supported by any known generic mutations, suggesting a non-inheritable etiology of the disease (Voineagu et al., 2011). Somewhat similarly, Ginsberg et al. (2012) (Ginsberg et al., 2012) did not find differences in CpG methylation in the ASD brain, but also highlighted the significance of dysregulated inflammatory transcriptional signatures (Ginsberg et al., 2012). Of note, even the largest meta-analysis to date confirmed these findings, but did not propose what particular pathways may be switched on or which types of cells they are involved (He et al., 2019).

Importantly, further pathway analysis, using the Reactome annotation analysis, sheds light on what immune processes may be upregulated in the ASD brain (ESF TABLE 2). The top functions here were again related to inflammation and cytokines. More specifically, we found that the upregulated genes were enriched in IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IFNα, β and γ signaling and phosphorylation of TCR co-receptors. Even though the data in all 3 studies is generated from total RNA derived from samples that contain a heterogeneous mixture of cells and it is unknown how many cells would have been in these samples, it is noteworthy that a number of overexpressed genes is typical for T-cell activation. For example, IL-4 and IL-13 are hallmark T helper (Th) 2 cytokines involved in allergic reactions and antibody isotype switching. Interestingly, together with IL-10, these two cytokines can lead to the differentiation of M2 macrophages (Espinosa Gonzalez et al., 2022) which are suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of ASD (Maes et al., 2021b). Furthermore, CD44 is also found to be upregulated, and it is expressed primarily on effector and memory Th1 cells, which activate the cellular immune response against infections (CD8 T-cells for viral infections, and macrophages for bacterial infections) (Baaten et al., 2010). Importantly, these findings are in line with a previous study proposing (even if in a small cohort of 6 subjects) that this pattern of upregulated inflammatory genes in the ASD brain is more related to an autoimmune T-cell mediated signature than activation of the innate arm of the immune system (Garbett et al., 2008).

Garbett et al. (2008) (Garbett et al., 2008) also suggest that there may be underlying viral infections that trigger chronic autoimmune processes, which in turn result in dysregulated neurodevelopment (Garbett et al., 2008). Indeed, evidence for this can be provided by our report too. First, overrepresented terms (using Metascape enrichment analysis) in the upregulated gene list were SARS-COV2 and EBV transcriptional patterns (ESF Fig. 1). Second, taking the analysis one step further to which proteins are encoded by these upregulated genes and what processes they may be involved in, protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis also revealed that the two largest clusters contained genes that were enriched in cytokine and interleukin signaling and inflammatory responses. Of note, there were four genes coding for members of the IFN-α family (i.e. IFNA2, IFNA10, IFNA16 and IFNA21) suggesting an involvement of viral infections in the etiology of the disease. Interestingly, besides the above-mentioned association with viral response genes, IFNA21 is related to Rubella infection (Mo et al., 2007) suggesting that a number of different viral pathogens could be responsible for these transcriptional alterations in the brains of ASD patients.

Table 2 presents the results of the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) analysis using Metascape enrichment analysis performed on the dysregulated genes in patients with ASD. The first part of Table 1 shows that four major densely connected network components could be extracted, and the application pathways and process enrichment analysis on these MCODE components show that the first two components denote immune responses (MCODE_1 and MCODE_2 in Table 1), the third cell cycle and mitosis (MCODE_3 in Table 2), and the fourth (MCODE_4) the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway.

Table 2.

GO analysis of up-and downregulated genes in brain and blood of ADS patients.

| MCODE | GO | Description | Log10(P) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated genes in Brain | All | R-HSA-1280215 | Cytokine Signaling in Immune system | −50.8 |

| All | GO:0006954 | inflammatory response | −36.6 | |

| All | WP5115 | Network map of SARS-CoV-2 signaling pathway | −32.6 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-1280215 | Cytokine Signaling in Immune system | −45.1 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | −42.7 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-449147 | Signaling by Interleukins | −38.9 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0071345 | Cellular response to cytokine stimulus | −11.1 | |

| MCODE_2 | R-HSA-1280215 | Cytokine Signaling in Immune system | −11.0 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0031012 | Extracellular matrix | −10.7 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-1640170 | Cell Cycle | −16.0 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-69278 | Cell Cycle, Mitosis | −15.0 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-606279 | Deposition of new CENPA-containing nucleosomes at the centromere | −11.7 | |

| MCODE_4 | WP4172 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | −8.0 | |

| MCODE_4 | hsa04151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | −7.9 | |

| MCODE_4 | GO:0002697 | Regulation of immune effector processes | −6.2 | |

| Downregulated genes in Brain | MCODE_1 | GO:0005743 | Mitochondrial inner membrane | −36,4 |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0031966 | Mitochondrial membrane | −35,6 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0019866 | Organelle inner membrane | −35,3 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0005762 | Mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit | −8,2 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0000315 | Organellar large ribosomal subunit | −8,2 | |

| MCODE_2 | R-HAS-5368286 | Mitochondrial translation initiation | −7,6 | |

| Blood (all up- and down-regulated genes) | All | R-HAS-72766 | Translation | −59,6 |

| All | R-HAS-156827 | L13a-mediated translational silencing of Ceruloplasmin expression | −57,4 | |

| All | R-HAS-72706 | GTF hydrolysis and joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit | −57 | |

| Upregulated genes in Blood Cluster 2 | All | GO:0006974 | cellular response to DNA damage stimulus | −17.2 |

| All | GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | −10.9 | |

| All | R-HSA-1640170 | Cell Cycle | −10.4 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | −9.7 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0006281 | DNA repair | −9.4 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-73894 | DNA Repair | −8.5 | |

| MCODE_2 | hsa05206 | MicroRNAs in cancer | −4.7 | |

| MCODE_2 | WP5087 | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | −4.2 | |

| MCODE_3 | WP3959 | DNA IR-double strand breaks and cellular response via ATM | −7.2 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-1640170 | Cell Cycle | −5.9 | |

| MCODE_3 | GO:0006974 | cellular response to DNA damage stimulus | −5.8 | |

| Upregulated genes in Blood Cluster 3 | All | GO:0050778 | Positive regulation of immune response | −16.9 |

| All | GO:0002697 | Regulation of immune effector process | −16.2 | |

| All | GO:0002706 | Regulation of lymphocyte mediated immunity | −16.0 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-198933 | Immunoregulatory interactions between a Lymphoid and a non-Lymphoid cell | −19.7 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0002706 | Regulation of lymphocyte mediated immunity | −16.2 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0002708 | Positive regulation of lymphocyte mediated immunity | −15.7 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0001819 | Positive regulation of cytokine production | −9.4 | |

| MCODE_2 | R-HSA-9020956 | Interleukin-27 signaling | −8.7 | |

| MCODE_2 | R-HSA-8984722 | Interleukin-35 Signaling | −8.6 | |

| Downregulated genes in Blood Cluster 1 | All | hsa01230 | Biosynthesis of amino acids | −19,53 |

| All | hsa01200 | Carbon metabolism | −17,3 | |

| All | GO:0006096 | Glycolytic process | −15,9 | |

| MCODE_1 | hsa01200 | Carbon metabolism | −24,2 | |

| MCODE_1 | GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | −22,9 | |

| MCODE_2 | M145PID | P53 DOWNSTREAM PATHWAY | −9,4 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0000307 | Cyclin-dependent protein kinase holoenzyme complex | −7,4 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0010942 | Positive regulation of cell death | −6,9 | |

| MCODE_3 | GO:0106310 | Protein serine kinase activity | −3,9 | |

| MCODE_3 | GO:0004674 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity | −3,6 | |

| MCODE_3 | GO:0004712 | Protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity | −3,6 | |

| MCODE_4 | WP2507 | Nanomaterial induced apoptosis | −8,3 | |

| MCODE_4 | hsa04210 | Apoptosis | −8,2 | |

| MCODE_4 | M220PID | CASPASE PATHWAY | −7 | |

| MCODE_5 | GO:0005543 | Phospholipid binding | −4,1 | |

| MCODE_5 | GO:0015629 | Actin cytoskeleton | −4,1 | |

| MCODE_5 | GO:0030036 | Actin cytoskeleton organization | −4 | |

| Downregulated genes in Blood Cluster 3 | All | GO:0051603 | Proteolysis involved in cellular protein catabolic process | −34,2 |

| All | GO:0030163 | Protein catabolic process | −34,2 | |

| All | GO:0044257 | Cellular protein catabolic process | −33,6 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-5607764 | CLEC7A (Dectin-1) signaling | −34,8 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-2871837 | FCERI mediated NF-kB activation | −33,4 | |

| MCODE_1 | R-HSA-5676590 | NIK-->noncanonical NF-kB signaling | −32,7 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0006511 | Ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | −10,1 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0019941 | Modification-dependent protein catabolic process | −10 | |

| MCODE_2 | GO:0043632 | Modification-dependent macromolecule catabolic process | −10 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-937061 | TRIF(TICAM1)-mediated TLR4 signaling | −10,7 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-166166 | MyD88-independent TLR4 cascade | −10,7 | |

| MCODE_3 | R-HSA-166016 | Toll Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Cascade | −10 | |

| MCODE_4 | R-HSA-8951664 | Neddylation | −6,3 |

Interestingly, having already pointed out the likely involvement of adaptive immunity activated in response to viral infections, potentially leading to autoimmune neurodevelopmental dysregulation, running the gene set of upregulated transcripts against another algorithm (WikiPathways, 2021, Descartes Cell type and tissues 2021, Panther, 2016, using Enrichr) implicated activation of Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) signaling as well (ESF Figs. 2–4). TLRs are typical for the innate immune system and macrophages in particular, including the ones, which are resident in the brain – the microglia. Indeed, activation of this type of cell in the brain of children with ASD has been indicated by a number of publications (Ohja et al., 2018). If there is indirect evidence for this from transcriptomic studies and investigation of cytokine levels in plasma, Morgan et al. (2010) (Morgan et al., 2010) demonstrated histologically that microglial density and volume are higher than normal in the grey and white matter, respectively (Morgan et al., 2010) in a large proportion of ASD patients (9 of 13). Importantly, the abovementioned dysregulation of the cytokine network, including Th1 and Th2 cells (ESF Table 2) extends previous findings that lower blood TGF-β levels may lead to the generation of fewer regulatory T-cells. This in turn can result in the overactivation of effector T-cells and stimulation of the microglia, ultimately causing impaired neurodevelopment (Ohja et al., 2018).

Enrichment analysis performed on the fourth MCODE component (Table 1) indicates involvement of the PI3K-Akt pathway, which extends the results of previously published data. Dysregulation of this signaling axis in ASD has been proposed by both sequencing studies (Sharma and Mehan, 2021), and experimental studies. For example, Akt and its downstream target mTOR have been shown to be more phosphorylated, thereby activating T-cells isolated from children with ASD compared to healthy controls (Onore et al., 2017). Interestingly, inhibition of AKT by LY294002 and of mTOR by rapamycin has been shown to reduce irritability and improve social behaviour in a mouse model of ASD (Xing et al., 2019). All in all, our analyses confirm the importance of this signaling axis in ASD and the previously suggested potential benefit of pharmacological inhibition of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway (Sharma and Mehan, 2021).

3.2.2. Analysis of genes downregulated in the brain

ESF, Table 2 shows the network characteristics of the cluster extracted from the downregulated transcripts in the brain of ASD patients. Cytoscape Network Analyzer showed that the top-3 hubs of this downregulated network were in descending order: NDUFB7 (20), UQCRQ (19) and NDUFS4 (19) and the most important non-hub bottleneck was CYCS. NDUFB7 (NADH: Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Subunit B7), UQCRQ (Ubiquinol-Cytochrome C Reductase Complex III Subunit VII), NDUFS4 (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 18 kDa subunit) and CYCS (cytochrome c) are key components of the ETC protein complex, which mediates mitochondrial ATP synthesis, respiratory transport, and complex 1 biogenesis (STRING, 2023). Since the backbone of a network may be considered a new drug target (Maes et al., 2021a, 2021b), it may be concluded that immune-inflammatory (e.g., IL6), TP53, JUN and mitochondrial ATP production should be the new drug targets in the treatment of ASD.

These results are further corroborated by annotation and enrichment analyses. Thus, the gene expression results were mainly associated with mitochondrial function, suggesting abnormalities in these organelles (ESF Fig. 5). The outcome of the MCODE analysis performed with Metascape (Table 1) and PPI network annotation analyses using GO Biological, Cellular Process and Cellular Component analysis using Enrichr (ESF Figs. 6–8) show that the most important terms enriched in this network are related to the mitochondrial membrane, the ETC, and ATP production.

A number of studies reported that mitochondrial dysfunctions have been observed in 8–48% of children with ASD (Rossignol and Frye, 2012a; Balachandar et al., 2021; Frye et al., 2021; Rose et al., 2012; Rossignol and Frye, 2012b; Siddiqui et al., 2016). Approximately 30–50% have aberrant biomarkers for mitochondrial function (abnormal values of lactate, pyruvate, alanine, creatine kinase, ammonia, and aspartate aminotransferase) (Balachandar et al., 2021; El-Ansary et al., 2018; James et al., 2004; MacFabe et al., 2011; Morava et al., 2006; Weissman et al., 2008) and ∼80% of children with ASD have reduced activity of the electron transport chain (ETC) (Napoli et al., 2014). Several studies have reported significantly lower activity of ETC complexes in the brain tissue of children with ASD (4–10 years of age) in frontal (Chauhan et al., 2011), temporal, (Chauhan et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2013) and cerebellar parts (Chauhan et al., 2011).

Anitha et al. (2013) (Anitha et al., 2013) also observed a reduced expression of mitochondrial ETC genes in postmortem brains of autistic patients, as follows: 11 genes of complex I (NADH dehydrogenase), 5 genes of complex III (cytochrome bc1 complex) and complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), and 7 genes of complex V (ATP synthase). Complex V shows consistently reduced expression in all brain regions of autistic patients (Anitha et al., 2013). Complex I reduction has been found to increase free radical production, and complex III defects may be involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to neuronal cell death (Anitha et al., 2013; Andreazza et al., 2010; Jeong and Seol, 2008; Kim et al., 2000). Our Metascape enrichment analysis shows a high alteration in genes belonging to complex I and IV (COX) (ESF Figs. 6–8). Changes in COX can lead to severe, metabolic disorders affecting the CNS in childhood (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of; Pecina et al., 2004). Decreased activity of ETC 3 and 4 leads to the increased lactate/pyruvate ratio observed in ASD (Weissman et al., 2008; Essa et al., 2013; Tsao and Mendell, 2007) According to Weissman et al. (2008) (Weissman et al., 2008), ETC complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) deficiency affects 64% of ASD patients, followed by complex III (cytochrome bc1 complex) with 20%. While Chauhan et al. (2011) (Chauhan et al., 2011) observed ETC defects in children with autism aged 4–10 years, Anitha et al. (2013) (Anitha et al., 2013) showed that ETC deficiency persists into adulthood.

Other postmortem studies of brain tissue from autistic patients confirmed lower expression of mitochondrial ETC complex I nuclear genes (Tang et al., 2013; Anitha et al., 2013), specifically, in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), superior temporal gyrus, occipital cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and primary motor cortex of individuals with ASD (Tang et al., 2013; Anitha et al., 2013). Schwede's et al. (2018) (Schwede et al., 2018) also reported down-regulated genes related to mitochondrial function. But they showed data revealing a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic dysregulation in the cerebral cortex of ASD patients (Schwede et al., 2018). It is assumed that these changes in mitochondria may contribute to the pathophysiology of idiopathic autism (Schwede et al., 2018). According to their study, the genes for both synaptic and neuronal signaling dysfunction are the most enriched among genes with downregulated expression in autism, according to one of the largest studies of system-level analysis of the ASD brain transcriptome (Voineagu et al., 2011).

Decreased activity of enzymes such as aconitase in the temporal zone (Rose et al., 2012) has also been shown, as has diminished pyruvate dehydrogenase in the frontal (57% of autistic patients) (Gu et al., 2013) part of postmortem brain tissues obtained from children with ASD. Visualizing techniques such as magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) revealed decreased levels of cerebral ATP in autistic patients in cortical brain areas, thus supporting the concept of energy dysfunction in the CNS (Minshew et al., 1993). This is the second most gene-enrichment term that we depict. Abnormal levels of brain markers of mitochondrial function (increased N-acetyl-aspartate, increased lactate, abnormalities in phosphocreatine, αATP, α-adenosine diphosphate, dinucleotides and diphosphosaccharides) were also found to correlate with the severity of language and neuropsychological deficiency in the patient group (Minshew et al., 1993; Corrigan et al., 2013; Golomb et al., 2014; Ipser et al., 2012). Functional positron emission tomography (PET) studies support the observed dysfunction in brain energy metabolism (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of; Clements et al., 2018; Goh et al., 2014) and abnormal expression of proteins associated with mitochondrial function (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of; Suzuki et al., 2013; Anitha et al., 2012; Zurcher et al., 2021). In addition to this evidence, Kato et al. (2022) (Kato et al., 2022) investigated the topographical distribution of mitochondrial dysfunction in vivo in brains of children with ASD by PET with 2-tert-butyl-4-chloro-5- (Gevezova et al., 2020)-2H-pyridazin-3-one ([18F]BCPP-EF). They found a decrease in complex I proteins and lowered functional activities in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in association with the severity of aberrations in social communication abilities (ADOS-2). These authors, therefore, proposed that the mitochondrial ETC complex I may be a potential therapeutic target to treat the core symptoms of ASD (Zurcher et al., 2021). Mitochondrial dysfunction is typical not only of ASD but also of a number of metabolic diseases as well as of a wide range of psychiatric disorders (Dantzer et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2008; Shao et al., 2008), such as mood disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Friedreich's ataxia (Nuzzo et al., 2014; Anderson and Maes, 2020; Morris et al., 2017). Finally, Voineagu et al. (2011) (Voineagu et al., 2011) made a systematic assessment of transcriptional changes in ASD and their genetic basis as evidence of genetic overlap with autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Voineagu et al., 2011), which also show cognitive and behavioural symptoms like ASD. After analysing the gene clusters in the brains of autistic children, we performed enrichment and annotation analyses on the upregulated and downregulated DEPs in the peripheral blood of ASD patients.

3.3. Differentially expressed genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

3.3.1. Analysis of up- and downregulated genes in BPMCs

Analyzing the differentially expressed genes in PBMCs, both upregulated and downregulated genes, showed dysregulation of immune, translational and metabolic processes as well as a viral process (Table 1, ESF Fig. 9; ESF TABLE 3; ESG TABLE 4). Metascape enrichment analysis of the collapsed DEGs in the peripheral blood of ASD patients (ESF Fig. 9) showed that translation, infection, and a defense response with involvement of adaptive immunity appeared to be differentially expressed. Furthermore, this enrichment analysis suggested that different metabolic processes may be dysregulated in the blood cells of ASD patients. Omicsnet enrichment analysis (GO Biological Processes and Cellular Complexes) showed that a general dysregulation of translation and virally altered protein synthesis were amongst the most important paths enriched in the gene network. All this data may hint to the possible involvement of infections in the etiology of ASD. The latter has been widely discussed and supported by several studies showing association and risk of developing autism if infected with influenza and cytomegalovirus, for example, or even zika virus (Santi et al., 2021).

3.3.2. Analysis of genes upregulated in PBMCs

Using the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm analysis with an inflation factor of 1.3, we detected three networks in the 580 upregulated blood DEGs. ESF Table 1 describes the three clusters and their characteristics that were extracted from the upregulated transcripts in blood cells. Reactome enrichment analysis performed on the first cluster showed that eight of the top 10 most significant pathways were shared with those obtained from the collapsed cluster described in the previous section, whilst 12 out of the 15 first pathways are shared. Consequently, this first cluster captures what we described in the previous section.

Cluster 2 showed that the top 3 upregulated hubs and bottlenecks were the same three DEGs, namely: ATRX (ATP-dependent helicase ATRX, degree = 15 and betweenness centrality = 0.3130), HIST2H2BE (Histone H2B type 2-E, 13 and 0.1503, respectively) and EXO1 (exonuclease 1, 11 and 0.2495, respectively). The biological and molecular function GO processes, and KEGG and WikiPathways enriched in these DEPs enlarged with the first 10 interactions in the first shell (highest confidence at 0.900) were chromosome organization, DNA-dependent ATPase activity, mismatch repair, and telomere maintenance (STRING, 2022). This second cluster of the upregulated PPI network in PBMCs revealed another interesting property of ASD blood cells, namely: cellular response to DNA damage stimulus, enhanced DNA metabolic processes, and DNA damage repair (Table 1, ESF Fig. 10, ESF TABLE 5).

The increase in the proliferation and/or turnover of PBMCs can be easily explained by an underlying infection, an autoimmune condition, or inefficient regulation of the immune response. Several studies have investigated the functionality and activation level of PBMCs in children with autism. Interestingly, patients whose cells would be more responsive to stimulation with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (as measured by secretion of proinflammatory cytokines) would also show worse developmental and behavioral symptoms (Careaga et al., 2017). Similar observations of impaired monocytes in ASD have also been described, pointing to potential prior infections and a shift in the overall state of the immune system in children with this condition (Meltzer and Van de Water, 2017).

The finding that there may be upregulated genes involved in DNA repair is more striking, but is supported in the literature. Attia et al. (2020) (Attia et al., 2020) proved that autistic PBMCs are more sensitive to γ-radiation, which results in DNA damage, and have slower repair mechanisms in place (Attia et al., 2020). This is also in accordance with observations that people with autism have a higher incidence of cancer, where genomic instability is a driver (Markkanen et al., 2016). Lastly, DNA damage has been suggested as a potential etiological cause of ASD when occurring during embryogenesis, and indeed dysregulated repair mechanisms have been associated with autism-like features in animal models (Servadio et al., 2018).

Cluster 3 showed that the top 3 upregulated hubs were TBX21 (T-Box Transcription Factor 21, degree = 22), GZMB (Granzyme B, degree = 20) and CD247 (part of the TCR-CD3 complex, degree = 18), whilst the top 3 bottlenecks were MPO (myeloperoxidase, betweenness centrality = 0.2096), TBX21 (betweenness centrality = 0.2067) and CCL3 (Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 3, betweenness centrality = 0.1612). GO functional enrichment and WikiPathways analysis shows that an immune response, T cell receptor (TCR) binding ad TCR signaling, T cell receptor complex, and Th1 and Th2 differentiation are the top enriched pathways in the backbone of cluster 3 (STRING, 2022).

The most important functions overrepresented in the upregulated PBMC cluster 3 network were immune system activation and cytokine signaling (Table 1, ESF Fig. 11, ESF Fig. 12, ESF TABLE 6). Table 1 shows the MCODE analysis extracted two major MCODE components, namely: MCODE_1 (positive regulation of lymphocyte-mediated immunity) and MCODE_2 (IL-27 and IL-35 signaling). Both cytokines are members of the IL-12 cytokine family, the former being pro-inflammatory and the latter being anti-inflammatory by blocking Th1 and Th17 cells. Estes et al. summarized that there is an increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines (like IL-1, IL-6 and IL-12p40) and a decrease of anti-inflammatory mediators (like IL-10 and TGFβ) in the blood of children with ASD (Estes and McAllister, 2015), which is in line with what we observed. Other cytokines with less well-studied potential involvement in this condition have also been highlighted by our analysis, like IL-23, IL-27, IL-33 and IL-35. Ahmad et al. (2017) also reported immune imbalance in children with ASD and increased expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-21 and IL-22) and decreased anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-27 and CTLA-4) (Ahmad et al., 2017). The latter researchers found increased expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) in B cells and monocytes in ASD patients compared to typically-developing children (TDC). They proved the influence of environmental factors (di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP)) which caused a further increase in inflammatory signaling in the patient group (Nadeem et al., 2020b, 2022). The authors assume that immune system dysfunction is involved in the pathogenesis and progression of ASD (Nadeem et al., 2022). Even though the exact effect of these cytokines on disease development and/or progression is unknown, these data suggest a strong dysregulation of the immune system in ASD.

Once again, by analyzing only the upregulated genes in the PBMCs, we found hat different subsets of T-cells and cytokines, including Th17, IL-12 family, and IL-6 signaling, may be central in the pathogenesis of ASD. Our data and other studies suggest that Th1 and Th2 cells are important and that adaptive responses in regulatory T-lymphocytes may be underrepresented. In addition, the gene expression patterns in blood cells point toward a key role of dysregulation of Th17 cells in ASD. Highlighting the significance of this subset of T-lymphocytes in ASD.

Ahmed et al. (2020) reported a positive correlation between the increased antioxidant potential (SOD, GPx, GR-both at the protein and functionality levels) in patient CD4+ T cells and high levels of IL-17A (Nadeem et al., 2020c). Of note, the same cytokines can also act on monocytes and neutrophils, which show elevated IL-17A receptors in ASD patients, leading to an increase in oxidative stress players, including iNOS and ROS pointing to a complex role in inflammation in ASD (Nadeem et al., 2018, 2019b). In addition, Ahmed et al. reported enhanced IL-6/IL-17A signaling in children with ASD compared to TDCs allowing the categorization of patients according to the severity of the condition (Nadeem et al., 2020d).

Of note, the involvement of this subset of T cells in ASD is also proposed by data from mouse studies using maternal immune activation (MIA) as a risk factor for the appearance of neurodevelopmental problems in the offspring. Th17 cells in pups have been shown to develop more excessively than in control mice, while myeloid cells secrete increased amounts of IL-12 and CCL3 (also in accordance with our analysis) (Estes and McAllister, 2015).

Two key genes underpinning MCODE_1 are CD160 and CD83. This is in line with a previous study of 52 ASD patients showing a 1.7-fold increase in the CD160 molecule on NK and CD8 T-cells (Enstrom et al., 2009). Interestingly, Enstrom et al. (2009) (Enstrom et al., 2009) showed that NK cells isolated from patients had higher basal levels of IFNγ, perforin and granzyme B production. However, upon stimulation, these cells had reduced cytotoxic capabilities compared to the same subset of cells in healthy controls. Thus, a considerable dysfunction in that compartment of the immune system in ASD is proven. The CD83 glycoprotein is a marker of dendritic cells (DCs), which, as antigen presenting cells, are capable of activating T-lymphocytes. Importantly, the number of DCs is increased in the blood of children with ASD and their number correlates with increased amygdala volume and repetitive behaviour (Breece et al., 2013). All this makes it tempting to speculate that there may be an altered response to certain viral infections and inappropriate and/or inefficient activation and regulation of effector CD8 T-lymphocytes. Of note, ESF TABLE 6 shows a possible involvement of IL-27 signaling in ASD. Interestingly, this cytokine signaling pathway and its receptor, IL-27 receptor alpha are involved in viral infections (Ruiz-Riol et al., 2017; Coppock et al., 2020) Th17 regulation (Coppock et al., 2020), fetal membrane inflammation and preterm birth (Yin et al., 2017), and neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis (Senecal et al., 2016) suggesting a potential role of this signaling molecule in the etiology and pathogenesis of ASD.

In summary, the upregulated genes in blood cells from children with ASD are highly enriched in processes that suggest dysfunction in both innate and adaptive compartments of the immune system. There may be changes in myeloid, dendritic, and NK cells, neutrophils, and Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells. Furthermore, some transcriptional patterns point to the involvement of viral infection in the etiology and/or pathogenesis of autism.

3.3.3. Analysis of genes downregulated in PBMCs

Using MCL clustering analysis with an inflation factor of 2.2, three clusters were detected in the 1372 DEGs included in the analysis (ESF Table 1). As with the upregulated DEPs, we observed that there was a huge overlap between cluster 2 and the cluster of the collapsed genes. Enrichment analysis performed on this second cluster using Reactome showed that 10 of the top 15 most significant pathways were shared between cluster 2 and the collapsed cluster of up- and downregulated DEPs. Consequently, here we describe clusters 1 and 3 retrieved from the downregulated DEPs.

Network topological analysis of cluster 1 showed that exactly the same DEPs were determined as hubs and bottlenecks and, thus, as the backbone of this network, namely (in descending order of importance, degree, and betweenness centrality): TP53 (62 and 0.4697), GAPDH (50, 0.1587) and ACTB (45, 0.1282). Other DEPs followed at a distance. As such, TP53 belongs to the top 3 bottlenecks in the brain's upregulated genes and the top 3 downregulated genes in PBMCs. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) is an important enzyme in glycolysis, whereas the ACTB gene (beta-actin) encodes the ACTB protein, which is an intracellular cytoskeletal protein mediating cell structure and motility.

ESF Table 1 shows the network characteristics of cluster 3 extracted from the downregulated DEPs. The DEPs with the highest degree (47) and betweenness centrality (0.5259) was UBC (Polyubiquitin-C), which plays a key role in ubiquitin homeostasis (STRING, 2023). UBE2N (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N, degree = 23) and UBE2D1 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 D1, degree = 21) followed at a distance. These three DEPs together mediate ubiquitin protein ligase binding and protein polyubiquination and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (STRING, 2023).

Cluster 1 showed dysregulation of transcripts related to amino acid biosynthesis, P53 and VEGFA signaling pathways, as well as apoptosis (Table 1, ESF Fig. 13; ESF TABLE 7). A body of evidence suggests that changes in neuroactive amino acids may play a role in the pathogenesis and/or pharmacotherapy of psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and mood disorders. They are presented with symptoms, such as cognitive impairment and problems with social interactions, that are common to those of ASD (Zheng et al., 2017). This is explained by the fact that amino acids play an important role in cell metabolism, cell signaling, neurotransmission, and in the regulation of the immune system; all these processes are most significantly affected in ASD (Saleem et al., 2020). Several studies have reported decreased plasma amino acid levels among children with autism, revealing significant deficits in tryptophan, lysine, glycine, β-alanine, proline, and asparagine compared with controls (Zheng et al., 2017). Naushad et al. (2013) (Naushad et al., 2013) testify to the presence of low levels of tryptophan among patients, which largely contributed to the deterioration of behavior, and after the enrichment of the diet with this amino acid, social interaction improved (Naushad et al., 2013). Other evidence of metabolic disturbances is associated with hyperlactacidemia, which may result from a defect in gluconeogenesis, pyruvate oxidation, the Krebs cycle, or the respiratory chain (Vallee et al., 2020).

Other notable changes in the down-regulated transcripts are related to P53 and VEGF signaling pathways. P53 responds to various endo- and exogenous stressors by regulating a number of biological processes, including changes in bioenergetics. It acts through its nuclear transcription factor activity and translocation to the mitochondria. There, it enhances apoptosis, suppresses mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutagenesis, and affects the maintenance of mitochondrial copy number DNA (Napoli et al., 2012, 2014; Wong et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2020). Abnormalities of mtDNA (deletions) and higher p53 gene copy ratios have been reported in children with ASD aged 2–5 years (Wong et al., 2016). The authors hypothesized that this would lead to insufficient DNA repair capacity (Enstrom et al., 2009). Several studies have also reported the association between ASD and VEGF with lower VEGF levels in patients compared to controls (Emanuele et al., 2010; Skogstrand et al., 2019). Another study reported significantly lower serum VEGF concentrations in children with ASD compared to those with Rett syndrome, which has been suggested as a possible diagnostic tool to distinguish between the two disorders (Pecorelli et al., 2016).

MCODE analysis (Table 1) revealed abnormalities in carbon metabolism (CM) and apoptosis in ASD patients. CM encompasses the folate and methionine cycles and allows the formation of metabolites to be used for the biosynthesis of important anabolic precursors and methylation reactions (Schaevitz et al., 2014). In this regard, in ASD patients not only is the methylation status (Tremblay and Jiang, 2019) altered, but there is also evidence of abnormal folate and methionine metabolism (Tremblay and Jiang, 2019; Frye et al., 2017; Hoxha et al., 2021; Main et al., 2010; Mills and Molloy, 2022), which enhances the critical role of CM in the etiology of ASD. In addition, our enrichment analyses show that genes enriched for ASD risk are also associated with apoptosis. A number of studies have demonstrated dysregulation of apoptotic pathways and related caspase enzymes in the peripheral blood of ASD patients (Eftekharian et al., 2019). Significantly lower transcriptional levels of the apoptosis-related genes BCL2 and CASP8 have been reported (Eftekharian et al., 2019). The mRNA levels for caspase-1, -2, -4, -5 were significantly increased in children with ASD compared to healthy individuals, as were the protein levels of caspase-3, -7, -12.

MCODE analysis (Table 2) shows that the functions that are overrepresented in cluster 3 are dysregulation in proteolysis, IKK RIP, and neddylation. The receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) mediates the activation of proinflammatory cytokines by facilitating the induction of the IKK complex in nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathways. The role of inflammation in ASD is a major area of research, which, in combination with stressors, could upregulate NF-κB, a master switch for many immune genes. Several studies have reported a significant increase in NF-κB binding activity in peripheral blood samples from children with autism (Naik et al., 2011; Young et al., 2011). Neddylation is associated with the conjugation of the ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8, and is a regulatory mechanism of protein ubiquitination (Rabut and Peter, 2008). In patients with ASD, there is no information about these processes in peripheral blood.

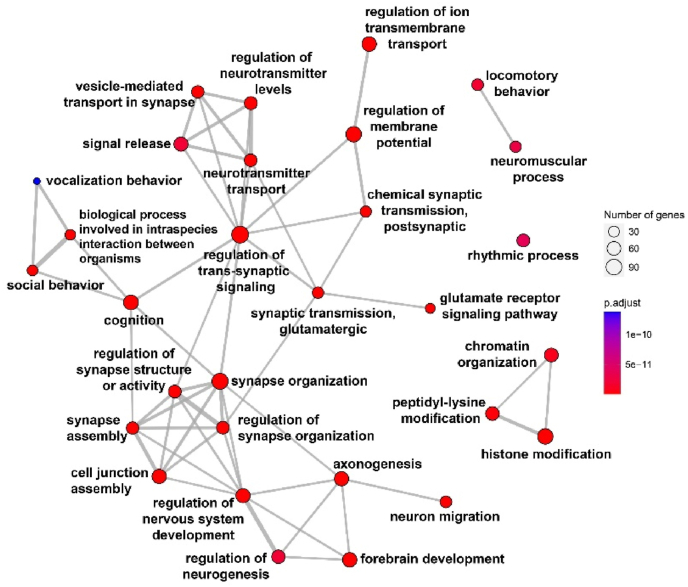

3.3.4. Enrichment map networks of DEGs in ASD

Enrichment analysis of all DEGs included in this study was performed to identify significant GO biological process terms associated with the DEGs of ASD. Fig. 3 shows the top 30 enriched terms, which are connected to reveal the overlap between the terms. The enrichment map networks were created by using the R package clusterProfiler (Nadeem et al., 2019a).

Fig. 3.

GO enrichment map network of top 30 GO terms for all 1022 ASD-associated genes. Each node represents a set gene (or a GO term) and each edge represents the overlap between two gene sets. The GO enrichment analysis was conducted in R using the ClusterProfiler package with the enrichGO function. One-sided Fisher's exact test was utilized, and the p-values were adjusted via Benjamini-Hochberg correction with a significance threshold set at 0.01.

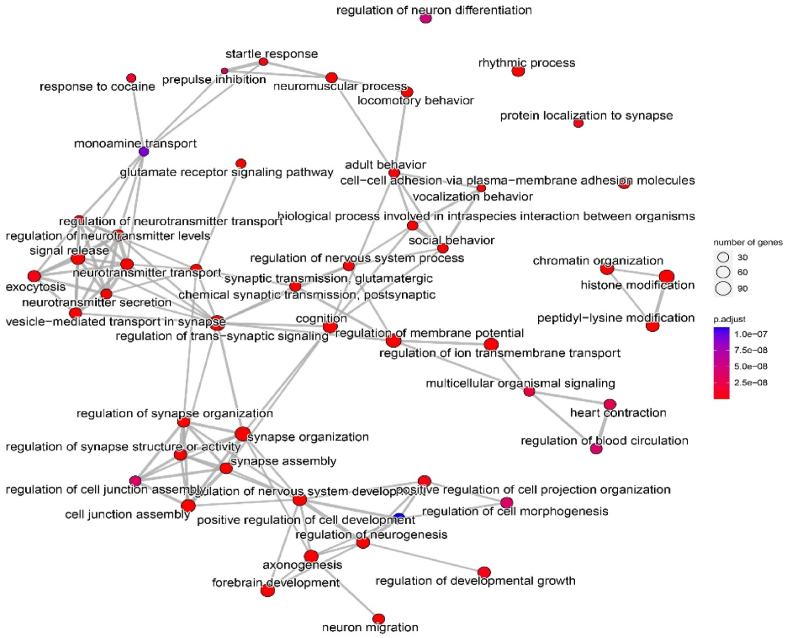

Regulation of trans-synaptic signaling appears to be a key hub in the networks involving various related terms. Regulation of nervous system development and synapse structure or activity is obviously a main process in ASD. Fig. 4 shows the top 50 enriched terms (clusters of the functional modules) that were associated with neurotransmitter systems and synapse functions.

Fig. 4.

GO enrichment map network of top 50 GO terms for all 1022 ASD-associated genes. Each node represents a set gene (or a GO term) and each edge represents the overlap between two gene sets. The GO enrichment analysis was conducted in R using the ClusterProfiler package with the enrichGO function. One-sided Fisher's exact test was utilized, and the p-values were adjusted via Benjamini-Hochberg correction with a significance threshold set at 0.01.

3.3.5. Limitations

Our investigation is limited by the heterogeneity of the patient samples in terms of clinical phenotypes, disease severity, and demographic characteristics of the study groups. We relied on the diagnoses, exclusion criteria, and clinical evaluation provided by the original study authors. The study incorporated information from multiple meta-analyses, allowing us to identify a greater number of genes that contribute to the pathogenesis of ASD. As a result, it was impossible to distinguish between the sexes and to define the potential effects of age, ASD phenotypes, and illness severity. Moreover, our findings are founded on associations obtained from case-control studies, which do not prove causality. Nonetheless, by constructing combined gene, transcriptional, and protein networks and utilizing annotation and enrichment analysis, we were able to identify the underlying pathway and molecular signatures of ASD in peripheral blood and the CNS, as well as the similarities between the two compartments.

4. Conclusions

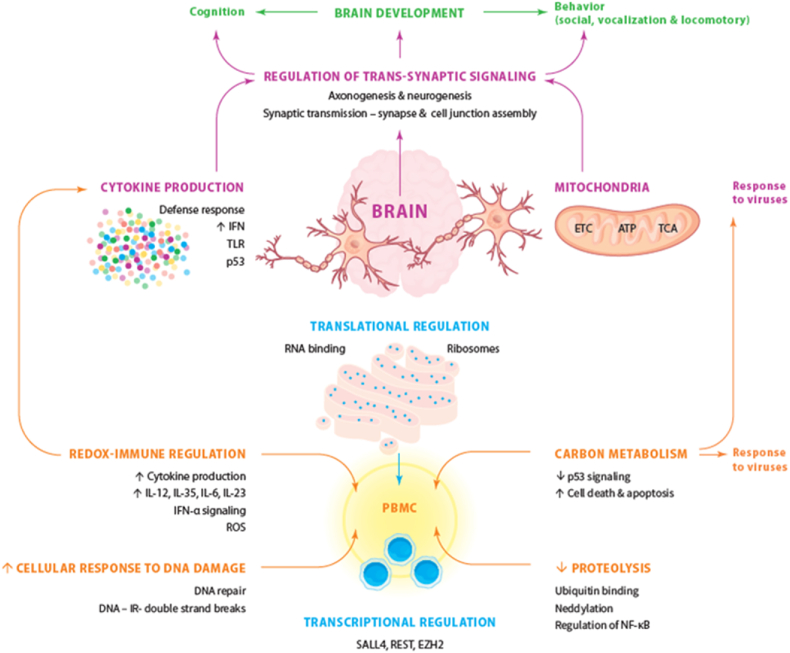

Fig. 5 summarizes the findings of the present study. The upregulated genes in the PBMCs of ASD patients are highly associated with virally activated protein synthesis, replication, and DNA damage repair mechanisms. Proinflammatory cytokines, particularly IFN-α and IL-27, both related to viral infections, are important players in the upregulated gene network. Overexpression of CD160 and CD83 on immune cells indicates the involvement of both innate and adaptive immune response in ASD pathogenesis. The downregulated DEGs in PBMCs are enriched in ubiquination, amino acid and carbon metabolism and glyconeogenesis. Aberrations in carbon metabolism, inhibited proteolysis, and enhanced cellular response to DNA damage may affect the overall response to viral infections. The peripheral P53 and VEGF pathways, together with apoptosis related genes like BCL2 and CASP8 show lowered expression profiles. These data suggest that increased IFN signaling and other indicants of activated immune-inflammatory pathways should be regarded as defense mechanisms against viral infections.

Fig. 5.

Summary of our findings showing the causal relationships between genes and pathways linking neurodevelopment, neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and regulation of transsynaptic signaling in autism spectrum disorders.

Our analyses revealed that the upregulated genes in the CNS of ASD patients are enriched in immune-inflammatory pathways, cytokine production, TLR signaling and viral infections, with a major involvement of the PI3K-Akt pathway. The downregulated genes in the CNS are enriched in mitochondrial dysfunctions at different levels including the ETC and ATP production.

Therefore, it is safe to suggest that peripheral activation of immune-inflammatory pathways may lead to CNS neuroinflammation with increased cytokine and TLR signaling and dysregulation of mitochondrial metabolism. Our study revealed that the consequent aberrations in axonogenesis, neurogenesis, synaptic transmission, and regulation of transsynaptic signalling may affect brain development with subsequent impairments in ASD behaviours and cognition.

Our network topological analyses also revealed new drug targets to treat or prevent ASD, namely a) the backbones of the upregulated (sub)networks in the brain (IL6, TP53, JUN, CD44, CXCL10, CCL3, IFNB1, IL13, ITGB2, SYK, HBB, RELA, and HIST2H2BE) and peripheral blood (ATRX, HIST2H2BE, EXO1; TBX2, GZMB, CD247, MPO, CCL3); b) the backbones of the downregulated (sub)networks in the brain (NDUFB7, UQCRQ, NDUFS4, NDUFB6, and CYCS) and peripheral blood (TP53, GAPDH, ACTB, UBC, UBE2D1 and UBEN2); and c) the different immune, mitochondrial, viral, and defence pathways in peripheral blood and the CNS described in our analyses. By controlling the pathways involved in neuroinflammation and mitochondrial metabolism in the CNS, and the activated inflammatory pathways in the periphery, new therapeutic approaches may be developed to treat ASD. Nevertheless, probably the most important targets are the transcription cofactors or master regulators that we identified in our study, and especially those that show communalities between both the PBMCs and brain cells. As such the top 2 master regulator targets could be the RELA and IRF1 transcriptional factors.

This picture shows the complex interplay in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) among transcriptional factors and regulation, immune-inflammatory pathways, carbon metabolism, proteolysis, and DNA repair, which may be the consequence of viral infections. Peripheral immune activation may translate into central neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunctions leading to dysfunctions in trans-synaptic signaling and thus brain development and the behavioral and cognitive disorders of autism spectrum disorders. Consequently, axonogenesis, neurogenesis, synaptic transmission and the regulation of transsynaptic signaling are affected resulting in alterations in brain development with consequent disorders in cognition and behaviors reminiscent of ASD.

Availability of data and materials

The output of the annotation and enrichment analyses generated during the current study are available from MM upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research was supported by a Rachadabhisek Research Grant, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, to MM. AS was supported by King Mongkut's University of Technology North Bangkok, Contract no. KMUTNB-65-KNOW-16. The sponsor had no role in the data or manuscript preparation.

Author's contributions

VS and MM designed the study. Statistical analyses were performed by MM, KP and AS, Visualization by KP, AS, MM and VS. Writing - first draft: MG and YS. Writing - editing: MM, VS, KP. All authors revised and approved the final draft. MG and YS attributed equally to the study as first authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study is a secondary data analysis on existing data using open, deidentified and non-coded data sets and, therefore, this is non-human subjects research, which is not subject to IRB approval.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100646.

Contributor Information

Victoria Sarafian, Email: victoria.sarafian@mu-plovdiv.bg.

Michael Maes, Email: michael.maes@mu-plovdiv.bg.

Abbreviations

- ACC

Anterior Cingulate Cortex

- ACTB

Actin Beta

- ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- AKT

Serine-Threonine Protein Kinase

- ASD

Autism Spectrum Disorder

- ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate

- BCL3

B-Cell Lymphoma 3

- C/EBP

CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein

- CASP8

Caspase 8

- CCL3

Chemokine (C–C Motif) Ligand 3

- CM

Carbon Metabolism

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CXCL10

C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10

- CYCS

Cytochrome C

- DEG

Differentially Expressed Genes

- DEP

Differentially Expressed Proteins

- DRRS

Duane-Radial Ray Syndrome

- EBV

Epstein-Barr Virus

- ETC

Electron Transport Chain

- EXO1

Exonuclease 1

- EZH2

Enhancer of Zeste 2 Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Subunit

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GWAS

Genome-Wide Association Studies

- GZMB

Granzyme B

- HAT

Histone Acetyltransferase

- HBB

Hemoglobin Subunit Beta

- HIST2H2BE

Histone H2B type 2-E

- IFNB1

Interferon Beta 1

- IFNα

Interferon-Alpha

- IKK

IκB Kinase

- IL-1RA

Interleukin-1 Receptor

- IRF1

Interferon Regulatory Factor 1

- IRF8

Interferon Regulatory Factor 8

- ITGB2

Integrin Subunit Beta 2

- KAT2A

K(Lysine) Acetyltransferase 2A

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MET

Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition Factor

- MHC class I

Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Molecules

- MIA

Maternal Immune Activation

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA

- mTOR

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin

- NDUFB7

NADH Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Subunit B7

- NDUFS4

NADH-Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Subunit 4

- NELFE

Negative Elongation Factor Complex Member E

- NF-κB

Nuclear Factor ΚB

- PBMCs

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

- PcG

Polycomb-Group

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinases

- PPI

Protein-Protein Interactions

- PRC2

Polycomb Repressive Complex

- RELA

RELA Proto-Oncogene

- REST

RE1-Silencing Transcription Factor

- RIP1

Receptor-Interacting Protein 1

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- SALL4

Spalt-Like Transcription Factor 4

- SYK

Spleen Associated Tyrosine Kinase

- TBX21

T-Box Transcription Factor 21

- TCR

T cell Receptor

- TGF-β

Transforming Growth Factor Beta

- TLR

Toll-Like Receptors

- TP53

Tumor Protein P53

- TRIM28

Tripartite Motif Containing 28

- UBC

Polyubiquitin C

- UBE2D1

Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme E2 D1

- UQCRQ

Ubiquinol-Cytochrome C Reductase Complex III Subunit VII

- VEGFA

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Only publicly available data were used for all analyses in this paper.

References

- Ahmad S.F., et al. Imbalance between the anti- and pro-inflammatory milieu in blood leukocytes of autistic children. Mol. Immunol. 2017;82:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Harbi N.O., et al. Elevated expression of toll-like receptor 4 is associated with NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative stress in B cells of children with autism. Int. Immunopharm. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G., Maes M. Mitochondria and immunity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2020;103 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreazza A.C., Shao L., Wang J.F., Young L.T. Mitochondrial complex I activity and oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins in the prefrontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2010;67:360–368. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S.V., et al. Case-control meta-analysis of blood DNA methylation and autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism. 2018;9:40. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0224-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anitha A., et al. Brain region-specific altered expression and association of mitochondria-related genes in autism. Mol. Autism. 2012;3:12. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anitha A., et al. Downregulation of the expression of mitochondrial electron transport complex genes in autism brains. Brain Pathol. 2013;23:294–302. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P., et al. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011;25:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia S.M., et al. Evaluation of DNA repair efficiency in autistic children by molecular cytogenetic analysis and transcriptome profiling. DNA Repair. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baaten B.J., et al. CD44 regulates survival and memory development in Th1 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandar V., Rajagopalan K., Jayaramayya K., Jeevanandam M., Iyer M. Mitochondrial dysfunction: a hidden trigger of autism? Genes Dis. 2021;8:629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]