Abstract

In recent years multi-parental mapping populations (MPPs) have been widely adopted in many crops to detect quantitative trait loci (QTLs) as this method can compensate for the limitations of QTL analyses using bi-parental mapping populations. Here we report the first multi-parental nested association mapping (MP-NAM) population study used to detect genomic regions associated with host-pathogenic interactions. MP-NAM QTL analyses were conducted on 399 Pyrenophora teres f. teres individuals using biallelic, cross-specific and parental QTL effect models. A bi-parental QTL mapping study was also conducted to compare the power of QTL detection between bi-parental and MP-NAM populations. Using MP-NAM with 399 individuals detected a maximum of eight QTLs with a single QTL effect model whilst only a maximum of five QTLs were detected with an individual bi-parental mapping population of 100 individuals. When reducing the number of isolates in the MP-NAM to 200 individuals the number of QTLs detected remained the same for the MP-NAM population. This study confirms that MPPs such as MP-NAM populations can be successfully used in detecting QTLs in haploid fungal pathogens and that the power of QTL detection with MPPs is greater than with bi-parental mapping populations.

Subject terms: Quantitative trait, Fungal genetics

Introduction

To understand the evolution of plant fungal pathogenicity, it is crucial to identify the genomic regions underlying the pathogenicity1. Initially, it was suggested that the pathogenicity of plant fungal pathogens was due to a single or a few genomic regions/genes and that these genes were recognised by the host plant and hence, follow a gene-for-gene model2. With the identification of several other host–pathogen interaction model systems, the expression of virulence of plant fungal pathogens on host plants was proposed to be a cumulative effect of multiple interacting genomic loci or quantitative trait loci (QTLs)3,4.

The QTLs responsible for inducing a virulence response in the host plant can be dissected through QTL mapping to extract important information on the genetic architecture of these phenotypic expressions5,6. QTL mapping studies are performed by linkage analysis in segregating bi-parental mapping populations5. The number of recombination events that occur within the mapping population determines the density of the linkage map. Many bi-parental mapping population studies have been conducted in fungal plant pathogens to identify QTLs responsible for the virulence of the pathogen7–10. However, in bi-parental mapping populations, the number of recombination events is restricted due to inadequate genetic diversity present between the two parents resulting in detecting broad chromosomal regions responsible for the phenotypic expression11–13. Hence, QTL mapping in bi-parental mapping populations is limited by low genetic map resolutions, inadequate genetic diversity between parents14 and inability to identify the same QTL in other genetic backgrounds15.

To overcome the constraints of QTL mapping in bi-parental populations, genome‐wide association mapping studies (GWAS) have been used to identify QTLs responsible for the virulence of fungal plant pathogens using genetically diverse populations from unknown kinship backgrounds16. The high mapping resolution in GWAS is achieved by its capacity to explore a broad genetic background coupled with capturing more allelic diversity occurring through historical recombination events and employing diversity panels which may comprise of fungal isolates collected from different geographical areas, years and hosts11,16,17. GWAS does, however, have its own constraints, such as spurious associations from the confounding effects of inherent population stratification and cryptic relatedness. While regulating these issues is possible with certain statistical methods, the methods have less power for QTL detection associated with population structure due to false negatives.

Multi-parental mapping (MPP) methods integrate bi-parental QTL and GWAS to detect robust genomic regions associated with phenotypic traits18. A population for a commonly used MPP method like nested association mapping (NAM) is developed by crossing a common parent/parents with a diverse set of founder lines15,18. In multi-reference (MR) NAM population studies, multiple parental lines are inter-crossed without using a common parent to increase the allelic diversity and increase rare alleles to moderate frequencies18. Multi-parent advanced generation inter-cross (MAGIC) is another widely used MPP in which several founder lines are intercrossed over several generations19. Multi-connected bi-parental mapping populations used in MPP analyses increase the allelic diversity of the populations and capture both recent and historical recombination events whilst reducing the confounding effects occurring due to the population structure of the population20. As per the authors’ knowledge MPP studies on plant fungal pathogens have not been attempted.

Net blotch is an economical important foliar disease of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.)21 caused by the plant fungal pathogen Pyrenophora teres [syn: Drechslera teres]22. Pyrenophora teres is a haploid heterothallic ascomycetous fungus. Sexual reproduction in P. teres is controlled by a single mating type locus (MAT1), which exists as two alternative forms or idiomorphs, i.e. MAT1-1 and MAT1-2. For the successful sexual reproduction of the fungus, two opposite mating types are required23. Pyrenophora teres exists as two forms, P. teres f. teres (Ptt) and P. teres f. maculata (Ptm), which cause net-form net blotch (NFNB) and spot-form net blotch (SFNB) symptoms in barley, respectively.

To date, six bi-parental mapping studies have been conducted to discover genomic regions accounting for avirulence/virulence of Ptt/Ptt populations24–29 while other studies have detected QTLs responsible for the virulence in Ptm/Ptm30 and Ptt/Ptm hybrid mapping populations31. Two GWAS have also been conducted to identify genomic regions responsible for the virulence of P. teres in Ptt29 and Ptm32 populations. These mapping studies have identified QTLs responsible for the virulence of many globally grown barley cultivars like Beecher, Harbin, Kombar, Rika and Skiff across all 12 chromosomes in the P. teres genome, demonstrating the complexity of the P. teres-barley pathosystem. The current study aimed to 1. identify virulence QTL using a MP-NAM population developed by crossing Ptt isolates that are virulent and avirulent on barley cultivars Skiff and Prior, and 2. determine the QTL detection power of a MPP population i.e. compare MP-NAM versus bi-parental mapping.

Materials and methods

Biological materials

Four Ptt populations (HRS11093xHRS09127, HRS11093xHRS10136, NB81xHRS09127 and NB81xHRS10136) consisting of 403 progeny isolates in total were developed by crossing four Ptt isolates (Table 1). Crosses were made as indicated in Dahanayaka et al.51. Four barley cultivars, Beecher, Commander, Prior, and Skiff, obtained from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries in Queensland, were used in the phenotypic assays for the QTL analyses.

Table 1.

Details of the four bi-parental mapping populations.

| Cross | Isolate Parent 1 |

Mating type | Disease reaction score | Isolate Parent 2 |

Mating type | Disease reaction score | Number of ascospores used for genetic maps | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | Skiff | Prior | Skiff | ||||||

| 1 | HRS11093 | MAT1-1 | 10 | 1.5 | HRS09127 | MAT1-2 | 1 | 9.8 | 94 |

| 2 | HRS11093 | MAT1-1 | 10 | 1.5 | HRS10136 | MAT1-2 | 1 | 9 | 94 |

| 3 | NB81 | MAT1-1 | 10 | 1.5 | HRS09127 | MAT1-2 | 1 | 9.8 | 120 |

| 4 | NB81 | MAT1-1 | 10 | 1.5 | HRS10136 | MAT1-2 | 1 | 9 | 95 |

Genotyping by DArTseq

Progeny and parental cultures were grown on half-strength potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (20 g/L PDA; Biolab Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 22 °C for 10 days. The mycelia of the progeny and parental isolates were scraped and freeze dried for 48 h. Freeze dried samples were sent to Diversity Arrays Technology Pty. Ltd. (Canberra, ACT, Australia) for DNA extraction and DArTseq™.

Phenotyping of the progeny isolates

Phenotyping of the progeny isolates was performed following a completely randomised design in a controlled environment room at the University of Southern Queensland, Australia, with three replicates, as described in Dahanayaka et al.31. The four barley cultivars (Beecher, Commander, Prior, and Skiff) were grown in pots with 5 cm diameter and 14 cm height with each pot containing four plants each of the four barley cultivars. Plants were grown at day (12 h) and night (12 h) temperature of 23 ± 1 °C and 17 ± 1 °C respectively, at 75% humidity for 14 days. Barley cultivars Beecher and Commander were used as the resistant and susceptible control, respectively.

The conidial suspensions for inoculations were prepared as described in Dahanayaka et al.31. Three millilitres of the suspension diluted to 10,000 conidia/mL were used per pot for inoculations 14 days after sowing. The parental isolate HRS10136 was used as the control isolate for each inoculation experiment to monitor disease reaction score differences across different experiments. After inoculation pots were incubated in the dark for 24 h at 95% humidity with a temperature of 20 ± 1 °C. Plants were then transferred to the controlled environment room with the same environmental conditions as mentioned above. Nine days after inoculation, disease reaction scores on the second leaf of the barley plants were recorded (scale 1–10, where 1 represents no symptoms 10 represents dead leaves)33.

Genetic map construction

Individual genetic maps for four populations were constructed using SilicoDArT and SNP marker data obtained from DArTseq™. Both markers were filtered using 10% as the cut-off value for the minimum amount of missing data per isolates. Non-polymorphic markers were removed along with markers deviating from the 1:1 segregation ratio. Clonal isolate pairs of each progeny were identified using the clonecorrect function in poppr package version 2.8.334 in R version 3.0.235 and one clonal isolate from each pair was removed. SilicoDArT and SNP markers were grouped into linkage groups using the make linkage groups function in MapManager QTXb20 version 2.036 with a p = 0.05 search linkage criterion. Markers were ordered using RECORD37 and the final genetic map of each population was obtained after manual map curation38. The marker order of the linkage groups was confirmed by aligning marker positions to the Ptt reference genome, W1-1 (BioSample SAMEA4560035, BioProject PRJEB18107) using the bowtie239 function in Galaxy.

QTL detection by bi-parental mapping populations

The composite interval mapping method in Windows QTL Cartographer version 2.540 was used to identify QTLs associated with virulence in the bi-parental mapping populations. Experiment-wise LOD threshold values for each phenotypic trait were estimated at the 0.05 significance level based on 1,000 permutations41,42. Additive effects and the phenotypic variances explained by each QTL (R2) were calculated by Windows QTL Cartographer version 2.5. MapChart version 2.3243 was used to draw the QTL map.

QTL detection by MP-NAM population

The mppR package44 available in RStudio was used to detect QTLs associated with virulence in Ptt using the MP-NAM population. The genotypic and phenotypic data for the four bi-parental populations were combined to represent a single MP-NAM population. The final data set was quality filtered with 5% as the threshold minimum allele frequency for markers and 25% as the maximum missing data per isolate. This resulted in 1135 SilicoDArT and SNP markers from DArTseq™ and 399 progeny isolates being retained for the MP-NAM QTL analysis. QTL detection was carried out using cross-specific, bi-allelic and parental QTL effect models available in the mppR package. Significant thresholds for each trait were calculated using 1000 permutations. Cofactors were selected using the simple interval mapping method and multi-QTL model searches were implemented by composite interval mapping to detect QTLs in different types of effect models; bi-allelic (two alleles at the QTL position with consistent effect through the QTL position), cross-specific (at the QTL the allelic effects can be different in every cross), and parental (every parent carries a different allele with a consistent effect in every cross). The regression coefficients (R2) for each QTL were detected. Cross validations for the detected QTLs were carried out to assess the QTL effect in a pseudo-independent population to confirm the putative QTLs.

Comparison between bi-parental and MP-NAM populations for QTL detection

The power of QTL detection of bi-parental versus MP-NAM populations was compared by determining the number of QTLs identified with each set. Thus, results produced by the three MP-NAM QTL models were compared with results obtained from the four individual bi-parental mapping populations. Fifty isolates from each bi-parental population were randomly selected and pooled to create a smaller bi-parental and MP-NAM populations and the QTL analysis was conducted with Windows QTL Cartographer and the mppR package, respectively, following the same criteria as above. The analyses were repeated three times using three different sub-datasets (Run_1, Run_2 and Run_3). Each sub-dataset contained 50 randomly selected isolates from each bi-parental population.

Genetic diversity of the population

Principal analysis of coordinates (PCoA) and a neighbor-net network were used to detect the overall diversity structure and the genetic distribution of the isolates of each population. PCoA for the progeny isolates used in the MP-NAM population was conducted in DARwin v.6.045 using Euclidean distances with five principal coordinates. Neighbor-net network was built for the MP-NAM population in SplitsTree version 4.1346 with 1000 bootstrap. The Neighbor-net network was built based on the method described by Bryant and Moulton47 using neighbor joining algorithm48.

Plant ethical approval

Experimental research and field studies on plants (either cultivated or wild), including the collection of plant material, must comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Results

DArTseq analysis

A total of 4809 SNPs and 9810 SilicoDArT were obtained from DArTseq™. After quality filtering of markers for 10% missing values, non-polymorphism and segregation distortion (1:1), 1241, 1102, 568 and 1168 SNPs and SlicoDArT markers were retained for the HRS11093xHRS09127, HRS11093xHRS10136, NB81xHRS09127 and NB81xHRS10136 populations, respectively and used for the phenotypic evaluation and genetic map construction (Table 1).

Phenotyping of the progeny isolates

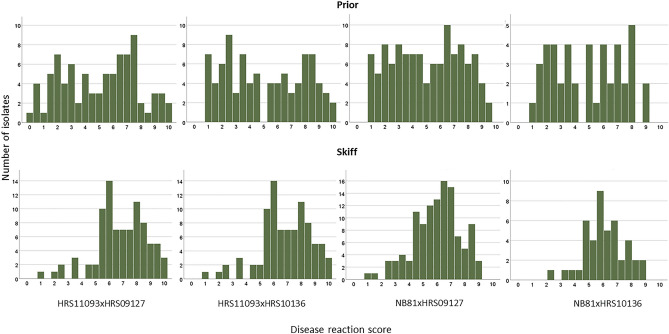

Disease reaction scores of the progeny isolates of the populations on barley cultivars Prior and Skiff ranged from avirulent to virulent (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Some of the isolates used in the genetic map construction did not produce conidia for phenotyping, hence the difference in numbers. Disease reaction scores of these progeny isolates were skewed on the resistant control Beecher and the susceptible control Commander towards avirulent and virulent, respectively, as expected (data not shown); hence, phenotypic data obtained from Beecher and Commander were not used for QTL analyses.

Figure 1.

Disease reaction scores of progeny isolates from bi-parental mapping populations on barley cultivars Prior and Skiff used in QTL analyses.

Table 2.

Disease reaction scores for barley cultivars Prior and Skiff used for QTL analyses.

| Cross | Number of isolatesa | Meanb | SEc | SDd | Skewness | Minimume | Maximumf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | |||||||

| HRS11093xHRS09127 | 85 | 5.0 | 0.29 | 2.65 | − 0.05 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| HRS11093xHRS10136 | 88 | 5.1 | 0.30 | 2.81 | 0.11 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| NB81xHRS09127 | 115 | 5.0 | 0.22 | 2.44 | − 0.02 | 1.0 | 9.3 |

| NB81xHRS10136 | 44 | 4.9 | 0.36 | 2.37 | 0.05 | 1.0 | 9.2 |

| MP-NAMg | 332 | 5.0 | 0.14 | 2.58 | 0.31 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| Skiff | |||||||

| HRS11093HRS09127 | 85 | 6.2 | 0.22 | 2.03 | − 0.97 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| HRS11093xHRS10136 | 88 | 6.8 | 0.19 | 1.84 | − 0.66 | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| NB81xHRS09127 | 115 | 5.9 | 0.16 | 1.69 | − 0.39 | 1.0 | 9.2 |

| NB81xHRS10136 | 44 | 6.1 | 0.22 | 1.43 | − 0.26 | 2.3 | 9.0 |

| MP-NAM | 332 | 6.3 | 0.10 | 1.82 | − 0.59 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

aNumber of isolates with phenotypic data.

bMean disease reaction score.

cStandard error.

dStandard deviation.

eMinimum disease reaction score.

fMaximum disease reaction score.

gMulti-parental Nested association mapping population.

Genetic map and bi-parental QTL analyses

The genetic maps of the four bi-parental populations consisted of 12–16 linkage groups spanning from 2029 to 2683 cM (Table 3). The average distance between flanking markers for the four populations ranged from 4.56 to 6.29 cM. The physical distance to genetic map distance ratio for the four populations with respect to the Ptt reference genome W1-1 ranged from 19.29 to 25.51 kb/cM.

Table 3.

Genetic map information for bi-parental mapping populations.

| Cross | Number of non-redundant markers | Number of linkage groups | Size of the genetic map cM |

Average distance between flanking markers | Physical distance to genetic map distance ratio (kb/cM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRS11093xHRS09127 | 428 | 16 | 2415 | 5.64 | 21.43 |

| HRS11093xHRS10136 | 496 | 13 | 2683 | 5.40 | 19.29 |

| NB81xHRS09127 | 445 | 12 | 2029 | 4.56 | 25.51 |

| NB81xHRS10136 | 390 | 16 | 2456 | 6.29 | 21.07 |

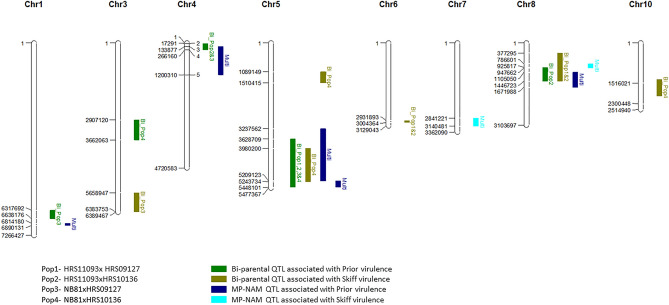

Results of the bi-parental mapping population QTL analysis are presented in Table 4 and Fig. 2. Between one to three QTLs associated with Prior or Skiff virulence were detected with individual bi-parental populations. A highly significant QTL associated with the Prior virulence was identified on chromosome 5 in all four populations. Significant LOD values for the QTLs ranged from 6.9 to 20.0 across the different populations. The phenotypic variance explained by the QTLs ranged from 33 to 63%. The most significant QTL identified for the Skiff virulence was located on chromosome 3 with a LOD score of 11.0 and 27% of the phenotypic variance explained. This QTL was only identified in the NB81xHRS09127 population. A QTL associated with Skiff virulence was detected on chromosome 5 in the NB81xHRS10136 population with a LOD score of 6.4 and 33% of the phenotypic variation explained. This QTL was located in the same region as the Prior virulence QTL.

Table 4.

List of QTLs for virulence to barley cultivars Prior and Skiff identified from bi-parental mapping populations.

| QTLs detected from the original bi-parental mapping populations (N = ~ 100) | QTLs detected from the subsets of bi-parental mapping populations (N = 50) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross ID | Chra | Marker namesb | Ptt reference genome position W1-1 (bp) | LODc | R2d | Parente | Run_1 | Run_2 | Run_3 | |||||

| Start marker | End marker | Start | End | LODc | R2d | LODc | R2d | LODc | R2d | |||||

| Prior | ||||||||||||||

| HRS11093xHRS09127 | 5 | 28949553 | 36348141 | 3628709 | 5448101 | 18.0 | 63 | HRS11093 | 8.0 | 39 | 7.8 | 37 | 8.9 | 32 |

| HRS11093xHRS10136 | 4 | 41806163 | 28945166 | 17291 | 133877 | 4.2 | 10 | HRS11093 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | 36351297 | 28949678 | 5117,957 | 5187816 | 12.0 | 38 | HRS11093 | 12.0 | 69 | 11.8 | 70 | NA | NA | |

| 8 | 28946536 | 74667498 | 925817 | 1446723 | 3.6 | 9 | HRS11093 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NB81xHRS09127 | 1 | 28945819 | 28949638 | 6317692 | 6638176 | 3.6 | 6 | NB81 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | 36353507 | 28,949623 | 17291 | 266160 | 5.4 | 8 | NB81 | 6.0 | 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5 | 28947023 | 28946415 | 3980200 | 5195868 | 20.0 | 39 | NB81 | 14.0 | 50 | NA | NA | 5.6 | 50 | |

| NB81xHRS10136 | 3 | 28948412 | 28948179 | 2907120 | 3662063 | 4.3 | 19 | NB81 | 4.0 | 17 | NA | NA | 11.0 | 28 |

| 5 | 28947023 | 36348141 | 3980200 | 5243734 | 6.9 | 33 | NB81 | 8.0 | 39 | NA | NA | 9.8 | 22 | |

| Skiff | ||||||||||||||

| HRS11093xHRS09127 | 6 | 70125623 | 70125623 | NA | NA | 3.4 | 14 | HRS01927 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8 | 36352197 | 28949798 | 377295 | 1369307 | 3.4 | 12 | HRS01927 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.4 | 19 | |

| HRS11093xHRS10136 | 6 | 28945564 | 36347277 | 2931893 | 3004364 | 5.0 | 25 | HRS10136 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.2 | 16 |

| 8 | 28946536 | 74667498 | 925817 | 1446723 | 4.6 | 18 | HRS10136 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NB81xHRS09127 | 3 | 41806520 | 28949264 | 5658947 | 6383753 | 11.0 | 27 | HRS01927 | 8.0 | 49 | NA | NA | 7.8 | 49 |

| 10 | 36347247 | 28949840 | 1373217 | 2000757 | 3.4 | 8 | HRS01927 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NB81xHRS10136 | 5.1 | 36348141 | 28947023 | 3980200 | 5243734 | 6.4 | 33 | HRS10136 | 6.0 | 29 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5.2 | 28945347 | 28946676 | 1089149 | 1510415 | 5.5 | 20 | HRS10136 | 5.5 | 15 | 4.6 | 37 | NA | NA | |

NA, not available.

aChromosome number according to W1-1 reference genome.

bFlanking marker names of the QTL.

cLogarithm of the odds.

dPhenotypic variation described by the respective QTL.

eParental isolate contributing the QTL.

Figure 2.

QTLs identified from bi-parental (Bi) and multi-parental (Multi) mapping populations for barley cultivars Prior and Skiff aligned to reference genome W1-1. QTLs are displayed to the right of the chromosome and map distances in base pairs on the left.

MP-NAM QTL analysis

QTL analysis of the MP-NAM population was carried out based on the bi-allelic, cross-specific and parental QTL effect models using 399 progeny isolates. Maximum of five and three QTLs were identified for the Prior and Skiff virulence, respectively. All models identified a QTL on chromosome 5 for Prior virulence with LOD scores ranging from 30.9 to 36.7 (Table 5). The phenotypic variance explained by the QTLs ranged from 14 to 39%. With both the cross-specific and parental models the QTL on chromosome 5 was split into two different QTLs. For Skiff virulence, three QTLs were detected across three different chromosomes with LOD scores ranging from 3.8 to 9.9 and phenotypic variance explained by these QTLs ranged from 4 to 13% across the different models. The same QTL was detected on chromosome 3 across all three models.

Table 5.

List of QTLs for virulence to barley cultivars Prior and Skiff identified from multi-parental mapping populations.

| QTLs detected from the original MP-NAM mapping populations (N = 399) | QTLs detected from the subsets of MP-NAM mapping populations (N = 200) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTL model | Chra | Peak marker nameb | QTL position in reference genome W1_1 (bp) | LODc | R2d | Range cMe | Run_1 | Run_2 | Run_3 | |||||||

| Start | End | LODc | R2d | Range cMe | LODc | R2d | Range cMe | LODc | R2d | Range cMe | ||||||

| Prior | ||||||||||||||||

| Biallelic | 1 | 28946148 | 6814180 | 6890131 | 6.1 | 4 | 26.0 | 3.6 | 5 | 26.4 | 4.3 | 3 | 9.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Biallelic | 4 | 28948011 | 17291 | 1200310 | 4.9 | 6 | 17.0 | 3.3 | 5 | 17.3 | 3.9 | 6 | 17.3 | 4.5 | 13 | 17.3 |

| Biallelic | 5 | 28949358 | 5209123 | 5448101 | 36.7 | 39 | 0.3 | 22.6 | 39 | 0.7 | 20.5 | 40 | 0.7 | 26 | 54 | 0.7 |

| Cross-specific | 1 | 28946148 | 6596840 | 6890131 | 3.2 | 2 | 36.5 | 4.0 | 6 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 4 | 1.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cross-specific | 4 | 36345919 | 133877 | 1011565 | 7.7 | 8 | 6.1 | 4.2 | 6 | 17.3 | 6 | 10 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 7 | 17.3 |

| Cross-specific | 5 | 28949553 | 3237562 | 5209123 | 3.6 | 2 | 42.6 | NA | NA | NA | 3.3 | 3 | 42.6 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cross-specific | 5 | 36347644 | 5209123 | 5448101 | 30.9 | 16 | 0.3 | 20.8 | 40 | 0.34 | 17.2 | 19 | 0.3 | 24.4 | 48 | 0.3 |

| Cross-specific | 8 | 28948394 | 1105050 | 1671988 | 3.5 | 3 | 18.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Parental | 1 | 28946148 | 6814180 | 6890131 | 3.4 | 3 | 26.4 | NA | NA | NA | 4.3 | 4 | 1.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Parental | 4 | 36345919 | 133877 | 1011565 | 7.2 | 6 | 6.1 | 3.5 | 5 | 17.3 | 5.8 | 10 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 7 | 17.3 |

| Parental | 5 | 28949553 | 3237562 | 5209123 | 4.2 | 3 | 42.6 | NA | NA | NA | 3.2 | 2 | 42.6 | NA | NA | NA |

| Parental | 5 | 36347644 | 5209123 | 5448101 | 31.0 | 14 | 0.34 | 20.4 | 38 | 0.34 | 17.9 | 19 | 0.3 | 24 | 45 | 0.3 |

| Skiff | ||||||||||||||||

| Biallelic | 3 | 36347042 | N/A | N/A | 8.9 | 12 | 1.8 | 5.0 | 10 | 0.36 | 4.9 | 12 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 10 | 1.8 |

| Cross-specific | 3 | 28949870 | N/A | N/A | 9.9 | 13 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 11 | 2.4 | 3 | 11 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 11 | 3.6 |

| Cross-specific | 7 | 28947398 | 2841221 | 3140481 | 5.2 | 7 | 18.3 | 3.4 | 8 | 18.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cross-specific | 8 | 28946174 | 786601 | 947662 | 3.8 | 4 | 6.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Parental | 3 | 28947129 | N/A | N/A | 9.6 | 12 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 15 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 12 | 13.3 | 3.5 | 10 | 3.9 |

| Parental | 7 | 28947398 | 2971153 | 3140481 | 4.1 | 5 | 8.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Parental | 8 | 28946174 | 786601 | 947662 | 3.8 | 4 | 6.7 | 3 | 7 | 12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA, not available.

aChromosome number according to W1-1 reference genome.

bPeak marker name of the QTL.

cLogarithm of the odds.

dPhenotypic variation described by the respective QTL.

eRange of the QTL.

Comparison of bi-parental mapping to MP-NAM mapping

The maximum number of QTLs detected using the MP-NAM population (N = 399) was eight with the cross-specific QTL model, compared to a maximum of five detected when using an individual bi-parental mapping population (N = ~ 100). The strength of MP-NAM versus bi-parental mapping QTL analyses was further tested using populations containing fewer individuals, i.e. N = 200 for MP-NAM and N = 50 for each of the bi-parental populations. Fifty individuals were randomly chosen for each of the population and for three different runs. Out of the three runs (Run_1, Run_2 and Run_3), Run_1 obtained the highest number of QTLs in the MP-NAM QTL analysis (Table 5). The QTLs detected with all three models for Prior virulence on chromosomes 4 and 5 in the original MP-NAM mapping population were also reported for all runs and models in the smaller MP-NAM population. Similarly, the chromosome 3 QTL associated with Skiff virulence was detected with all models and runs. Minor QTLs were only detected in some runs or not at all with some of the models, e.g. QTL on chromosome 8 associated with Prior virulence (Table 5). Using the bi-parental mapping populations only the QTL on chromosome 5 of the HRS11093xHRS09127 population was detected in all runs (Table 5). None of the QTLs associated with Skiff virulence were detected in all runs.

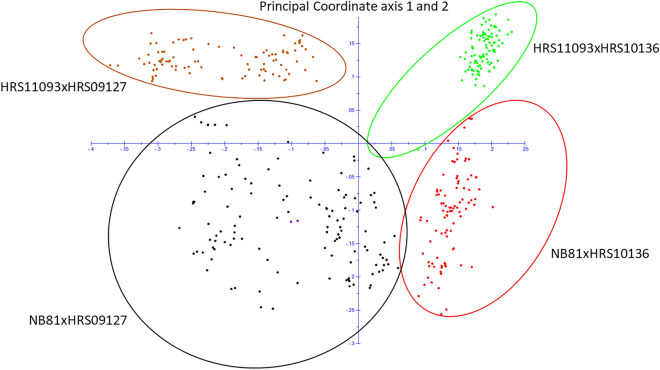

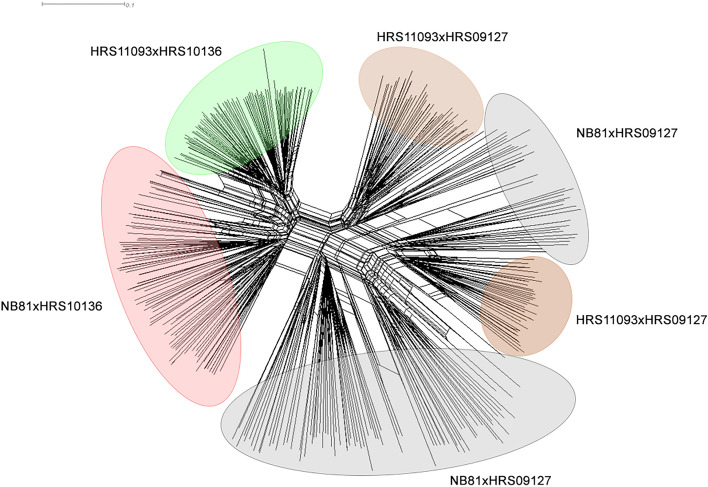

Genetic diversity of the population

The PCoA of 399 progeny isolates showed clear clustering of the four bi-parental populations as expected. The first and second principal coordinate axes (PCoA1 and PCoA2) explained 12 and 6% of the variance, respectively, and separated clusters by population. Out of the four populations, NB81xHRS09127 showed the highest genetic diversity within the population while HRS11093xHRS10136 showed the lowest (Fig. 3). The neighbor-net network consisted of two main groups. One group contained progeny isolates from HRS11093xHRS10136 and NB81xHRS10136 while the other group contained progeny isolates from HRS11093xHRS09127 and NB81xHRS09127. The neighbor-net network constructed for the MP-NAM population was highly reticulated as expected (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Principal analysis of coordinates for the MP-NAM population. Principal coordinate axis 1 and principal coordinate axis 2 explained 12 and 6%, respectively, for the genetic clusters.

Figure 4.

Neighbor-net network based on DArTseq marker for the MP-NAM mapping population.

Discussion

Multi-parental mapping populations have been used for many crops to detect QTLs as they have been useful in providing insight into the genetic architecture of complex phenotypes like grain yield, plant height and biotic and abiotic resistance amongst other phenotypes44. However, as per the authors’ knowledge usage of MPPs to identify QTLs in fungi has not previously been reported. This the first study to use a MP-NAM population to identify QTLs in a fungus.

Bi-parental mapping populations have been extensively used in the detection of QTLs in crops14,19. However, there are limitations with bi-parental mapping populations compared to MPPs in the successful detection of significant QTLs11,16. The principal limitations of bi-parental mapping populations are low genetic diversity resulting from genetic bottlenecking due to the choice of two parents and limited events of effective recombination to develop a precise genetic map. These limitations reduce the number of QTLs captured by bi-parental mapping populations.

The majority of NAM populations have been developed by crossing one reference parent with several other donor parents to obtain a diverse genetic background49. The NAM population used in this study was developed using more than one reference parent. The genetic principle behind the MP-NAM analysis used in this study is based on bi-parental populations and diversity panels. Bi-parental population analysis has the confounding effect of population structure, which is avoided when using MP-NAM analysis. Another advantage of MP-NAM populations is the detection of multiple alleles in the same QTL along with rarer and more diverse alleles.

Two out of the four parental isolates used in our mapping populations demonstrated high and low virulence on barley cultivars Prior and Skiff, respectively, while the other two demonstrated low and high virulence on Prior and Skiff, respectively. An increased number of recombination events occurring in a fungal population increases the genetic diversity of the population50. Using more than one parental isolate for the desired phenotype increases genetic diversity of the population as shown in the neighbour-net network and PCoA analysis in the current study and captures QTLs associated with the desired phenotype from more than one parent. As shown in this study, one to three QTLs were detected that were associated with Prior virulence using bi-parental mapping populations while five QTLs were detected using the MP-NAM population. For Skiff virulence, only two QTLs were reported for each bi-parental mapping population while three QTLs were detected for the MP-NAM population, thus confirming that the MP-NAM QTL detection method can detect a greater number of QTLs than the bi-parental method.

Most QTLs identified in the four bi-parental mapping populations of this study were co-localised, e.g. QTLs on chromosomes 4 and 5 identified for the Prior virulence. In populations HRS11093xHRS09127 and HRS11093xHRS10136 the contributing parent for the QTL on chromosome 5 was HSR11093 and in NB81xHRS09127 and NB81xHRS10136, the contributing parent for the QTL was NB81 suggesting that these isolates possess the same genomic regions on chromosome 5 associated with Prior virulence. QTLs associated with Prior virulence identified on chromosome 1, 3, and 8 of population NB81xHRS09127, NB81xHRS10136 and HRS11093xHRS10136, respectively, were unique QTL, not detected in the other populations. The QTL on chromosome 8 associated with Skiff virulence of bi-parental mapping population was also co-located with the QTL on chromosome 8 for Prior virulence. The QTL associated with Skiff virulence on chromosome 5 also co-located with the QTL associated with Prior virulence on chromosome 5. Co-localization of QTL associated with Prior and Skiff virulence could be due to either the presence of tightly linked genes in the same genomic region or lack of effective events of recombination between the two regions to identify the two genes as separate QTLs.

The QTLs identified on chromosomes 1, 4 and 5 for Prior virulence from the multi-parent population based on biallelic, cross-specific and parental models were located at the same genomic regions. The QTL detected on chromosome 5 for Prior virulence based on the biallelic model was a broad QTL. This QTL was detected as two QTLs in the cross-specific and parental models suggesting that there are two QTLs in this genomic region. This also suggests that the cross-specific and parental models may have better resolution power than the biallelic model. All QTLs associated with Prior virulence and QTL on chromosome 8 for Skiff virulence of the MP-NAM population were co-located with the QTLs identified by the four bi-parental mapping populations. Co-localisation of these QTLs validates the robustness of the QTLs identified in our study.

QTLs identified in our study were also co-localised with QTLs reported in previous bi-parental and GWAS studies. The location of the QTL identified on chromosome 5 for Prior virulence was similar to the QTLs AvrHar24, PttBee2 (Koladia et al.28), PttBee_5, PttSki_5, QTL11, QTL12 (Martin et al.4) and USQV5 (Dahanayaka et al.31) identified previously through bi-parental and GWAS studies. The QTL, PttBee228 and PttBee_54,29 associated with Beecher virulence were co-localised with our QTL on chromosome 5 associated with Prior virulence. The four parental isolates used in the current study were avirulent on barley cultivar Beecher and hence, used as the resistant control. Co-localisation of the Prior virulence QTL and the Beecher virulence QTL suggests that this genomic region codes for a gene/genes which would induce multiple reactions in different Ptt isolates. This may be due to the presence of different alleles of the same gene in different Ptt isolates or to possessing more than one virulence gene in the same genomic region. The QTL associated with Prior virulence on chromosomes 8 in the current study shared the same genomic region as PttTif228. Three QTLs responsible for Skiff virulence detected in the current study on chromosomes 3, 7 and 10 were co-located with QTL QTL7, PttPri_74,29 and VR227, respectively.

Comparison of the bi-parental and MP-NAM analyses revealed that MP-NAM QTL analysis had greater power to detect QTLs than bi-parental QTL mapping, even with a low number of progeny isolates. The number of progeny obtained from crossing fungal isolates can vary51. In some instances, crosses may produce insufficient numbers of ascospores for bi-parental mapping analyses. On such occasions, a MPP like MP-NAM is a useful alternative method for identifying QTLs in populations with low progeny numbers, where inter-connected multiple populations are available.

In conclusion, this study reported the first MPP QTL analysis conducted with a fungal population. The bi-parental mapping QTL analyses detected one to three QTLs associated with Prior virulence and two with Skiff virulence for the four populations developed from crossing P. teres f. teres isolates. The MP-NAM population, developed by combining the bi-parental mapping populations, detected five and three QTLs for Prior and Skiff virulence, respectively. The comparison of bi-parental and MP-NAM analyses revealed that QTL detection power of a MP-NAM population was greater than that of a bi-parental fungal mapping population even with a low number of progeny.

Author contributions

B.A.D. and A.M. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by B.A.D. The first draft of the manuscript was written by B.A.D. and reviewed by A.M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stukenbrock EH. Evolution, selection and isolation: A genomic view of speciation in fungal plant pathogens. New Phytol. 2013;199:895–907. doi: 10.1111/nph.12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flor H. The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. Adv. Genet. 1956;8:29–54. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60498-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pariaud B, Robert C, Goyeau H, et al. Aggressiveness components and adaptation to a host cultivar in wheat leaf rust. Phytopathology. 2009;99:869–878. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-7-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin, A. et al. Advances in understanding the epidemiology, molecular biology and control of net blotch and the net blotch barley interaction. In Achieving Durable Disease Resistance in Cereals (ed. Oliver, R) 477–523 (Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2021).

- 5.Collard B, Jahufer M, Brouwer J, et al. An introduction to markers, quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and marker-assisted selection for crop improvement: The basic concepts. Euphytica. 2005;142:169–196. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-1681-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackay TF, Stone EA, Ayroles JF. The genetics of quantitative traits: Challenges and prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:565–577. doi: 10.1038/nrg2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart EL, Croll D, Lendenmann MH, et al. Quantitative trait locus mapping reveals complex genetic architecture of quantitative virulence in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018;19:201–216. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clare SJ, Wyatt NA, Brueggeman RS, et al. Research advances in the Pyrenophora teres–barley interaction. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 2020;21:272–288. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adobor SK, Gela TS, Banniza S, et al. Mapping of genomic regions linked to stemphylium blight (Stemphylium botryosum Wallr.) resistance in lentil using linkage mapping and marker-trait association analysis. bioRxiv. 2022;202:258. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh P, Huang S-Y, Hernandez AG, et al. Genomic regions associated with virulence in Setosphaeria turcica identified by linkage mapping in a biparental population. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2022;159:103655. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2021.103655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu J, Holland JB, McMullen MD, et al. Genetic design and statistical power of nested association mapping in maize. Genetics. 2008;178:539–551. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.074245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascual L, Albert E, Sauvage C, et al. Dissecting quantitative trait variation in the resequencing era: Complementarity of bi-parental, multi-parental and association panels. Plant Sci. 2016;242:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Boer MP, Zheng C, et al. An IBD-based mixed model approach for QTL mapping in multiparental populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021;134:3643–3660. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-03919-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myles S, Peiffer J, Brown PJ, et al. Association mapping: Critical considerations shift from genotyping to experimental design. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2194–2202. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paccapelo MV, Kelly AM, Christopher JT, et al. WGNAM: Whole-genome nested association mapping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022;135:2213–2232. doi: 10.1007/s00122-022-04107-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korte A, Farlow A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: A review. Plant Methods. 2013;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu C, Gore M, Buckler ES, et al. Status and prospects of association mapping in plants. TPG. 2008;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanc G, Charcosset A, Mangin B, et al. Connected populations for detecting quantitative trait loci and testing for epistasis: An application in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;113:206–224. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott MF, Ladejobi O, Amer S, et al. Multi-parent populations in crops: A toolbox integrating genomics and genetic mapping with breeding. Heredity. 2020;125:396–416. doi: 10.1038/s41437-020-0336-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gage JL, Monier B, Giri A, et al. Ten years of the maize nested association mapping population: Impact, limitations, and future directions. Plant Cell. 2020;32:2083–2093. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathre D. Compendium of Barley Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. APS Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smedegård-Petersen, V. Pyrenophora teres f. maculata f. nov. and P. teres f. teres on barley in Denmark. In Royal Veterinary And Agricultural University (Copenhagen) 124–144 (1971).

- 23.McDonald W. Heterothallism in Pyrenophora teres. Phytopathology. 1963;53:771–773. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiland JJ, Steffenson BJ, Cartwright RD, et al. Identification of molecular genetic markers in Pyrenophora teres f. teres associated with low virulence on ‘Harbin’ barley. Phytopathology. 1999;89:176–181. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beattie AD, Scoles GJ, Rossnagel BG. Identification of molecular markers linked to a Pyrenophora teres avirulence gene. Phytopathology. 2007;97:842–849. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-7-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai Z, Faris JD, Weiland JJ, et al. Genetic mapping of Pyrenophora teres f. teres genes conferring avirulence on barley. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2007;44:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shjerve RA, Faris JD, Brueggeman RS, et al. Evaluation of a Pyrenophora teres f. teres mapping population reveals multiple independent interactions with a region of barley chromosome 6H. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014;70:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koladia VM, Faris JD, Richards JK, et al. Genetic analysis of net form net blotch resistance in barley lines CIho 5791 and Tifang against a global collection of P. teres f. teres isolates. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017;130:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2801-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin A, Moolhuizen P, Tao Y, et al. Genomic regions associated with virulence in Pyrenophora teres f. teres identified by genome-wide association analysis and bi-parental mapping. Phytopathology. 2020;110:881–891. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-19-0372-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlsen SA, Neupane A, Wyatt NA, et al. Characterizing the Pyrenophora teres f. maculata-barley interaction using pathogen genetics. G3. 2017;7:2615–2626. doi: 10.1534/g3.117.043265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahanayaka BA, Snyman L, Vaghefi N, et al. Using a hybrid mapping population to identify genomic regions of Pyrenophora teres associated with virulence. Front. Plant. Sci. 2022;13:2059. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.925107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clare SJ, Duellman KM, Richards JK, et al. Association mapping reveals a reciprocal virulence/avirulence locus within diverse US Pyrenophora teres f. maculata isolates. BMC Genom. 2022;23:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08529-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tekauz A. A numerical scale to classify reactions of barley to Pyrenophora teres. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1985;7:181–183. doi: 10.1080/07060668509501499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamvar ZN, Tabima JF, Grünwald NJ. Poppr: An R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partially clonal, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ. 2014;2:28. doi: 10.7717/peerj.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2021).

- 36.Manly KF, Cudmore RH, Jr, Meer JM. Map Manager QTX, cross-platform software for genetic mapping. Mamm. Genome. 2001;12:930–932. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-1016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Os H, Stam P, Visser RG, et al. RECORD: A novel method for ordering loci on a genetic linkage map. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005;112:30–40. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehmensiek A, Bovill W, Wenzl P, et al. Genetic Mapping in the Triticeae. Genetics and Genomics of the Triticeae. Springer; 2009. pp. 201–235. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langmead B, Salzberg S. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;2012:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, S. Windows QTL cartographer 2.5. http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart (2007).

- 41.Churchill GA, Doerge RW. Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics. 1994;138:963–971. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doerge RW, Churchill GA. Permutation tests for multiple loci affecting a quantitative character. Genetics. 1996;142:285–294. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voorrips R. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garin, V., Wimmer, V., Borchardt, D. et al. mppR: An R Package for QTL Analysis in Multi-parent Populations. R Documentation. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mppR/index.html (2018).

- 45.Perrier, X. & Jacquemoud-Collet, J.P. DARwin software. http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin (2023).

- 46.Huson DH. SplitsTree: Analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryant D, Moulton V. Neighbor-net: An agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:255–265. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitony JK, Sunohara H, Tasaki M, et al. Development of an Aus-derived nested association mapping (Aus-NAM) population in rice. Plants. 2021;10:1255. doi: 10.3390/plants10061255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drenth A, McTaggart AR, Wingfield BD. Fungal clones win the battle, but recombination wins the war. IMA Fungus. 2019;10:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s43008-019-0020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dahanayaka BA, Vaghefi N, Snyman L, et al. Investigating in vitro mating preference between or within the two forms of Pyrenophora teres and its hybrids. Phytopathology. 2021;111:2278–2286. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-21-0058-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.