Abstract

This report explores the nature and quality of social ties of formerly homeless individuals in recovery from serious mental illness and substance abuse and how these ties relate to experiences of community. Using grounded theory and cross-case analysis techniques, we analyzed 34 qualitative interviews conducted with predominantly racial/ethnic minority individuals receiving mental health services. Participants described a range of involvement and experiences in the mental health service and mainstream communities indicating a combination of weak or strong ties in these communities. Across participants, two broad themes emerged: ties that bind and obstacles that “get in the way” of forming social ties. Salient subthemes included those related to family, cultural spaces, employment, substance abuse, stigma and mental health service providers and peers. The current study integrates our understanding of positive and negative aspects of social ties and provides a theoretical framework highlighting the complexity of social ties within mainstream and mental health service communities.

Keywords: social ties, community integration, severe mental illness, homelessness, substance abuse, family ties, cultural spaces, mental health service community, qualitative methods, grounded theory, cross-case analysis, USA

Introduction

Being able to form and maintain reciprocal social ties is vital to social integration, better health outcomes and recovery for individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) and co-occurring substance abuse disorders (Tew et al., 2012). These social ties may provide opportunities to acquire the tools to facilitate structural and functional aspects of social interactions through which, “individuals learn about, come to understand, and attempt to handle difficulties” (Pescosolido, 1992, p. 1096).

Large, strong social networks and high satisfaction with social ties have a positive influence on the course of mental illness and recovery from substance abuse (Henwood, Padgett, Smith, & Tiderington, 2012) and are important determinants of overall health (Dupuis-Blanchard, Neufeld, & Strang, 2009). However, compared to the general population, individuals with SMI are known to have smaller and less reciprocal networks leading to lower social support and fewer environmental resources (Albert, Becker, McCrone, & Thornicroft, 1998). Comprising fewer friend and family and more service providers, these ties tend to be asymmetrical and constrained by professional relationship linking providers to consumers (Pahwa & Kriegel, 2018). The difficulties related to limited social ties and resulting social isolation are further exacerbated if individuals with SMI also struggle with substance abuse and/or homelessness (Padgett, Henwood, Abrams, & Drake, 2008). Understanding how individuals with SMI form social ties can be an important step in finding ways to increase their sense of connection and reduce social isolation.

Social ties are generally formed within an individual’s community and are important to community integration and recovery. According to social capital theory, social ties facilitate access to resources in the community (Lin, 2005). For those with SMI, in the absence of family and friends, mental health service providers often serve as de facto social ties (Albert et al., 1998; Hawkins & Abrams, 2007; Pahwa et al., 2014). Indeed, since the era of deinstitutionalization, there has been growing recognition that persons with SMI face challenges in forming and maintaining positive social ties and achieving community integration. Homelessness and/or substance abuse histories compound these challenges as having a substance abuse history makes it difficult to form new social networks devoid of people who use (Mohr, Averna, Kenny, & Del Boca, 2001). Similarly, individuals who are or have been homeless often contend with unstable and transient social ties related to their unstable housing status (Shibusawa & Padgett, 2009). A lack of clear theoretical and empirical models linking social ties with principles of community integration impedes the development of interventions to foster such positive outcomes (Webber, Reidy, Ansari, Stevens, & Morris, 2015).

This study aims to develop a more robust theoretical framework of social ties and community integration by recognizing the complexities behind social interactions and allowing for both positive and negative ways in which these relationships may impact individuals. Specifically, we address a significant gap in the literature by exploring the nature and quality of social ties of formerly homeless individuals in recovery from SMI and substance abuse and how these ties are benefiting or detracting from their social connectedness and ability to integrate into the community (or into multiple communities). Our research questions are the following:

Research Question 1: How do individuals with SMI, co-occurring substance abuse and a history of homelessness describe their perceived communities?

Research Question 2: How do individuals with SMI, co-occurring substance abuse and a history of homelessness describe their social ties within their perceived communities?

Research Question 3: What facilitates or hinders the formation and maintenance of social ties for formerly homeless individuals with SMI and co-occurring substance abuse history?

Method

Study Design

This study analyzed qualitative interview data collected as part of a larger study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health that focused on formerly homeless individuals with SMI and co-occurring substance abuse residing in a large Northeastern city in the United States. For the parent study, 40 participants were recruited from two programs using the following inclusion criteria: (a) over age 18, (b) English-language fluency, (c) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of SMI, (d) history of homelessness, and (e) history of substance abuse. Two senior staff from each program were asked to nominate 20 individuals who met the inclusion criteria. To avoid bias in the nomination process, only those who were jointly nominated were asked to participate. Interviews were conducted and transcribed between September 2010 and May 2011 by three trained interviewers with prior research and/or clinical experience. All participants gave informed consent and New York University’s human subjects committees approved all study protocols.

The participants were paid US$30 per interview. The minimally structured in-depth interviews lasted an average of 90 min and took place in participants’ apartments, a study office or a private office at the program site. The interview started with a question on their current life followed by questions about social and family relationships, mental health and psychiatric treatment experiences, housing and homelessness, employment, substance abuse and recovery. Social relationships were considered of potential importance for all of these experiences and were asked about both directly and indirectly through probes. Of the 40 participants in the parent study, 34 were included in this study. Six participants were excluded due to insufficient information about their social ties and communities.

Data Analysis

Our analysis was based on a combination of principles of grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) and case study analyses (Creswell, 2013) as outlined below.

Grounded theory analysis.

We used several principles of grounded theory methods to analyze transcripts of interviews collected in the parent study. As interviews were already completed, we were unable to simultaneously collect and analyze data as is key to a full grounded theory study. However, the first two authors analyzed qualitative data based on the guidelines of (Charmaz, 2006) including memo writing, constant comparison, initial open-ended, line-by-line coding, focused coding, axial coding, and theoretical coding with the purpose of creating building blocks for a theoretical framework of how social ties are conceptualized among formerly homeless adults in recovery from substance abuse and mental illness.

During initial open-ended, line-by-line coding, we coded the same five transcripts and developed a codebook through regular discussion of their memos and justification from the data for the creation and meaning of codes. After reaching consensus, the authors divided up the interviews evenly and coded the transcripts independently. We also randomly co-coded five additional transcripts to assess and maintain consensus in coding decisions.

We then conducted focused coding, collapsing codes to include only those most significant to the experiences of social ties and community followed by axial coding to relate subcategories within social ties and within a community (or communities). As we began theoretical coding to connect categories of social ties to experiences of community, we found that we needed a more in depth understanding of individual participants’ experiences. Thus, we made an analytic decision to conduct a multiple case study analysis to supplement the grounded theory analyses. This was consistent with principles of ground theory that allow for flexibility in the researchers’ decision-making process and “analytic directions [that] arise from how researchers interact with and interpret their comparisons and emerging analyses rather than from external prescriptions.” (Charmaz, 2006, p. 178).

Multiple case study analysis.

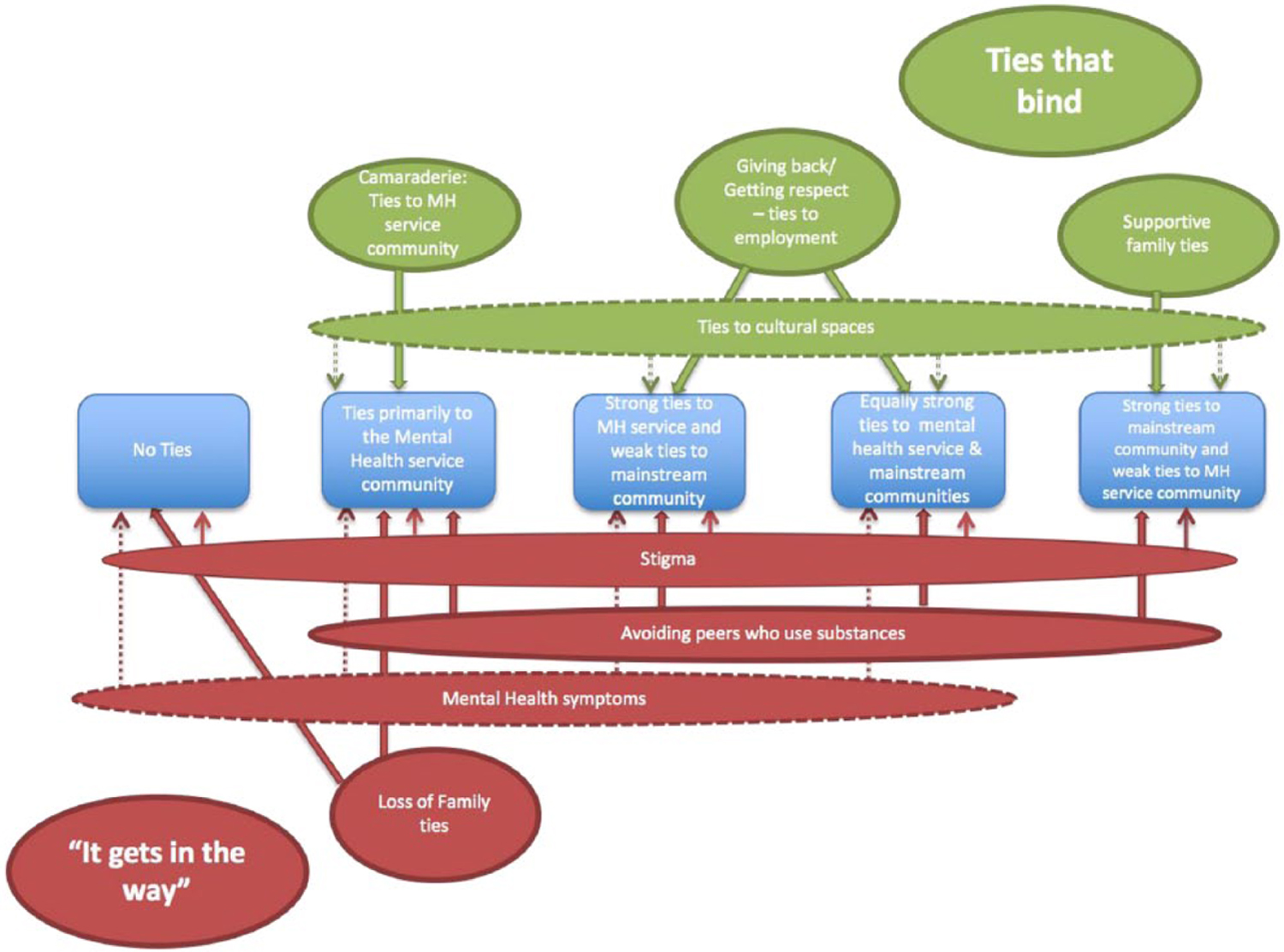

Multiple case study analysis (Creswell, 2013) consisted of producing case summaries including each participant’s perceived community of choice, level of integration, social ties that individuals had in each community and their overall sense of belonging with respect to their communities as a way to get an in-depth understanding of their social ties and degree of community integration. The authors met regularly to discuss themes around community and community integration that emerged within and across cases. We examined each individual case for the totality of their experiences in the mental health service and mainstream communities. From this analysis, a typology related to the relative strength or weakness of social ties within each community began to emerge which the co-authors determined by consensus (See Figure 1). The final step in our analysis was to link axial codes from the grounded theory analysis to the categories of strength/weakness of ties within each community that arose from the case study analysis (See Figure 2.)

Figure 1.

Theoretical typology of strength of ties to mental health service and mainstream communities.

Note. MH = mental health

Figure 2.

Intersection of strength and nature of social ties.

Rigor

Analytic process.

We enhanced the rigor in the analytical process through multiple strategies. Throughout, we engaged in constant comparison of the data by reviewing transcripts to search for confirming or disconfirming information related to codes and categories. This constant comparison of data was facilitated by memos connecting codes and participant experiences, that were kept by both Pahwa and Smith as audit trails as well as regular consultation meetings with co-author, Padgett (a qualitative methods expert and PI of the parent study) regarding the grounded theory-based and multiple case study analyses (Padgett, 2016)

Author reflexivity.

The two lead authors, Pahwa and Smith who conducted the data analyses were uniquely positioned with respect to the topic as well as to the participants of the study. Pahwa has done a substantial amount of research on social ties, communities and community integration for individuals with SMI. Smith is a multiracial social work researcher who identifies culturally with African Americans and has substantial clinical, administrative, and research experience in working with racially/ethnically diverse formerly homeless individuals with SMI and substance abuse disorders. As a result of the authors’ positions in relation to the topics of social ties, community integration, and the participants of this study, the authors were able to focus on specific aspects of the data which spoke to affiliation to specific communities and specific cultural nuances in relation to formation, maintenance, and loss of social ties. For example, Pahwa’s previous work on community and community integration enabled the researchers to delineate community typologies. Composition of the mental health service and mainstream communities was guided by the existing norms in the literature with mental health service providers and recipients included in the mental health service communities; and family members, friends, coworkers and neighbors included in the mainstream communities. Smith’s multiple identities as a multiracial African American researcher, lead her to be uniquely attuned to cultural aspects of black communities and thus was sensitive to experiences specific to black participants in the study.

Findings

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents the description of the 34 participants in the study. As shown in the table, participants included 26 men and 8 women and ranged in age from 29 to 73 years old (mean age = 52 years, SD = 9.28). The majority (64%) of participants identified as Black (20 identified as African American, 1 as Black/British-born and 1 as Jamaican-born); 15% (n = 5) were White, 9% were Hispanic (n = 3), 6% were Native American (n = 2). The remaining participants identified as Asian American (n = 1) and Native American/Cuban (n = 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 34).

| N (%), Range, or M ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 26 (76.5) |

| Female | 8 (23.5) |

| Age | |

| Range | 29–73 |

| M ± SD | 51.8 ± 9.3 |

| Race | |

| Black/African American | 22 (64) |

| White/Caucasian | 5 (15) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (9) |

| Native American/Native | 3 (9) |

| American and Cuban | |

| Asian American | 1 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 20 (58.8) |

| Divorced | 7 (20.6) |

| Widowed | 3 (8.8) |

| Separated | 4 (ll.8) |

| Number of homeless yearsa | |

| Range | 0–39 |

| M ± SD | 6.05 ± 8.1 |

Data are available for n = 33.

Grounded Theory-Based Analytical Findings: The Nature of Social Ties

Across participants, two broad themes emerged that shed light on the nature of their social ties: ties that bind and obstacles that “get in the way” of forming meaningful social ties. Supportive ties to family, cultural spaces, mental health services (“camaraderie”), and employment (“giving back/getting respect”) bound participants to the mainstream community, mental health service community, or both. Negative or “no family ties” and loss of ties due to mental health symptoms, substance abuse, or stigma emerged as obstacles that negatively impacted participants’ experiences in either communities or their ability to form or maintain social ties.

Ties that bind.

Participants discussed the presence of social ties in the mainstream community and the mental health service community, including family, friends, mental health service providers, mental health peers, and cultural community groups who provided support and/or a sense of belonging. This is reflected in the themes that emerged below.

Supportive family ties.

Many participants talked about how family provided a key source of support, most often emotional. For example, “James,” an African American male participant who attends a day treatment and art program regularly talked about the support he had through immediate and extended family and church, especially when he was hospitalized:

I had family members coming from a lot of places, my pastor came to visit me, friends of the family came to visit me, and I just realized that lots of people cared about me… they were there for me and they cared about me, they loved me, and they will always be there no matter what.

Reciprocity in relationships also was expressed as an important aspect of supportive family ties. Participants talked about being a social and/or financial support to their family members and how this expectation and responsibility had a positive effect on their lives. While we often assume that relationships for individuals with SMI and/or substance abuse histories only involve burden on the part of family members, participants also illustrated experiences of mutually beneficial support with their family members.

Ties to cultural spaces.

Many participants forged or maintained social ties through groups that have been historically known to be social and/or supportive gathering places in black communities such as churches (Armour, Bradshaw, & Roseborough, 2009) and barbershops (Alexander, 2003). Participants spoke of church as being part of their daily or weekly routine and as a means of socialization as is illustrated by “Joseph,” an African American male participant: “There are relationships, there are church, mingling with people in church … I’m not a religious fanatic but I like the outings, the gatherings, the men’s meeting, the neighborhood walk, peace walks.” Participants also spoke of church and God as providing emotional and spiritual support. Other participants found links to cultural spaces such as jazz clubs, barbershops and basketball courts. “Marcus,” an African American male participant who was otherwise estranged from other important ties such as family, spent most of his weekdays at his day treatment program and talked about socializing on the weekends with other men on the basketball court or in the barbershop. While the majority of the participants that discussed these cultural spaces were black some participants were from other racial or ethnic groups.

Camaraderie: Ties to the mental health service community.

For many participants, the mental health service community served as a place that fostered relationships, friendships and socialization with peers and providers. “Jack,” a White male participant, talked about what being a part of an art class at the mental health agency meant for him: “Well, it’s camaraderie and it’s helped me with something to do. I, unfortunately didn’t have anything to do and … I enjoy it. Even if I’m not that good.”

For those in peer provider roles, being part of the mental health service community in a reciprocal type of relationship seemed to provide camaraderie in a slightly different way from those who were part of the mental health service community as consumers only. “Michael,” an African American male participant, who is a peer provider at a mental health agency, talked about relationships with his coworkers outside of work and identified his coworkers as a part of a social group that went beyond mental health-related issues.

Participants also talked about strong bonds with their mental health service providers that created positive experiences and social ties for many participants in the mental health service community. “Tanya,” an African American woman, said of her service coordinator: “[She] wanted the change. She wanted to see you get better and her support and her being there … She never forgot my birthday.”

Giving back/getting respect: Ties to employment.

Participants talked about the role of helping people, giving back and/or serving as role models. In talking about her role helping consumers transition from Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) to supported housing, “Diana,” a Native American/Cuban female spoke to the importance of the helping role for peer providers in this study as well as the idea of “giving back”:

I’m even happier now because my natural characteristic is to be a caretaker, … with this position … I’m helping people and that’s why I do well … I share, I listening, which is key for me, and I uh, I give back, I give back, just being who I am.

In a similar vein, “Jack,” who previously talked about the camaraderie with other consumers also talked about being a role model for other consumers and the respect he receives in his peer provider role.

“It gets in the way”: Obstacles to forming or maintaining social ties.

Participants discussed a variety of factors that got in the way of forming or maintaining connections with people or socializing related to symptoms of mental illness; affiliations with substance-using peers; stigma associated with mental illness; and family loss and/or estrangement.

Mental health symptoms.

Several participants discussed ways in which specific symptoms of their mental illness created challenges to the quality of relationships and ties to other people in their lives. “Michael,” who has challenges related to paranoia, described the impact of his symptoms. “My … psychosis has got in the way of my fatherhood. My substance abuse also got in the way of my, my fatherhood.”

Avoiding substance-using peers.

Prevalent for those actively working on recovery from substance abuse, avoiding substance-using peers lead to isolation as illustrated by Jose, a Hispanic male:

I don’t have too many friends now because most of my friends, everybody I meet is always on something. Most of them are on crack cocaine so I don’t use crack cocaine so I stay away from them because I know how that is.

Stigma.

Several participants directly or indirectly talked about how the stigma of having a mental illness negatively impacted ties to family members. Mothers who lost custody of their children talked about how the stigma of mental illness negatively impacted ties with their children, as stated by “Victoria,” a Black/English female.

And if anything, that’s the most hurtful thing that I’ve been through with mental illness is the stigma that because it happens to be an emotional disability, they write you off completely … I did everything: I got off of drugs, I went to a program, I took medication. I was clean I’d say like two months into the court date, I was showing progress and they didn’t talk to me! … I was not included within what was going down in family court. To me I didn’t’ have a voice. I was seen immediately as incompetent because I had a mental illness.

Loss of family ties.

While family emerged as an important social tie and source of social support for some, others talked about the loss of family through death or estrangement that signaled a lack of support. For those with extensive loss, the result was isolation as revealed by, “Oscar,” an African American male with an extensive incarceration history who attended his mental health program regularly. “Since I been incarcerated I don’t have no family. My mom and pops passed since I been incarcerated. On my pops side, I lost contact. And my brother … I lost contact with him since like 95.” Others discussed complicated relationships that were estranged due to reasons such as histories of substance abuse.

Case Study Analysis: Strength of Social Ties in the Mental Health Service and Mainstream Communities

Through the case study analysis, we discovered that participants described a range of involvement and experiences in various communities that were intimately connected with the types, nature, and quality of their social ties. From this analysis, a theoretical typology emerged that described participants’ relative strength or weakness of social ties within the mainstream and mental health service communities. Figure 1 displays the five categories of the typology, which are described further below.

Individuals with no social ties.

Participants described experiences suggesting few, if any social ties to the mainstream community or mental health service community and social isolation. Social isolation was related to a number of factors including loss due to death of or estrangement from loved ones; avoidance of others due to a history of trauma, mental or physical health symptoms; and/or negative experiences with providers or consumers of mental health services.

Primary social ties to the mental health service community.

Participants described experiences that indicated that all or the majority of their social ties were in the mental health service community. These participants either had positive (or negative) relationships with service providers and/or had strong ties to other mental health service consumers.

Primary ties to mental health service community with some weak ties to the mainstream community.

Participants recounted experiences whereby they spent most of their time at treatment programs, substance abuse groups or other activities associated with the mental health service community. However, they also had limited social ties in the mainstream community, either in the form of relationships with family members, or through organizations such as churches. A related experience for these participants was that of transition, where participants were moving away from the mental health service community and increasing ties to the mainstream community.

Equally strong ties to the mental health service and mainstream communities.

Individuals who fell into this category had strong roots in the mental health service community, some via peer provider roles and emphasized the importance of being productive (often via employment) or connecting with others through music, church, and/or spirituality. While the parent study did not intentionally recruit individuals who were in a peer provider role, a number of participants identified as and spontaneously talked about being a peer provider. All participants also had strong roots in the mainstream community. Some participants had long-term relationships with others whom they knew prior to receiving mental health services.

Primary social ties to mainstream community with weak ties to the mental health service community.

Participants’ experiences indicated that their primary social ties were rooted in the mainstream community with weak ties to the mental health service community for continued treatment and services related to mental health and/or housing. Individuals who fell in this category had very strong ties that provided some type of social support such as family, friends, work, church, and/or other activities.

Integrating Case Study Typologies With Grounded Theory-Based Analytical Findings

During the final step of our analysis, we found that some themes were salient across all categories in Figure 1, while others clustered around specific typologies. As shown in Figure 2, four themes cut across participant experiences: For ties to cultural spaces, except those that were completely socially isolated, there were participants from all other typologies that discussed involvement in cultural spaces like churches, barber shops and barber shops. Avoiding substance-using peers was salient for those participants who were working on maintaining their sobriety across typologies. In addition, participants across all categories talked about grappling with stigma prevalent in the community. Individuals who had social ties primarily in the mental health service community talked about stigma in two ways. They discussed being more comfortable in the mental health service community due to the stigma prevalent in the mainstream community. They also talked about experiences of stigma within the mental health service community where they felt stigmatized by service providers or other peers. Individuals deeply rooted in the mainstream community talked about stigma from neighbors, potential employers and even family members. Individuals who talked about their mental health symptoms getting in their way belonged to all typologies except deep ties in the mainstream communities.

Four themes clustered around specific typologies related to the strength or weakness of socials ties in the mainstream and mental health service communities. Individuals who had very strong ties in the mainstream community, through positive relationships with immediate family, extended family and/or close friends and irrespective of whether they had additional mental health ties or not, illustrated a connection to the theme of supportive family ties. Some participants maintained relationships with others whom they knew prior to receiving mental health services. By contrast, individuals who showed deeper roots in the mental health service communities expressed loss of family ties due to death or estrangement and as a result had weak ties to the mainstream community. Unlike those who had stronger ties to the mental health service community, individuals who lost family ties and had no other meaningful ties expressed a sense of social isolation. This social isolation was often related to specific mental health symptoms that impeded participants from actively pursuing social relationships. The individuals with stronger connections to the mental health service community also expressed a sense of camaraderie within the mental health community that extended to other peers and service providers. For the theme related to giving back/getting respect: ties to employment, participants had ties both to the mental health and mainstream communities. Some participants felt a connection to the mental health community through their peer provider roles, and a few participants either volunteered or worked in a nonpeer provider role in the mental health field or an unrelated field. Regardless of the type of employment experience, participants described experiences of being respected, feeling valued, a sense of belonging and a sense of identity that tied them to their workplaces in intimate ways.

Discussion

Despite existing evidence on the positive influence of meaningful social ties and risk factors associated with sparse social ties for individuals with SMI and co-occurring substance abuse disorders, there is limited research on how these ties are formed within the context of their communities. The current study sought to develop a theoretical framework to understand the strength, nature, and quality of social ties for formerly homeless individuals with co-occurring SMI and substance abuse disorder. Our findings illustrate various ways in which individuals with SMI and co-occurring substance abuse disorders experience social ties within their mental health and mainstream communities. While some individuals talked about social isolation and a lack of meaningful social ties, a phenomena that is well documented in the literature (Albert et al., 1998; Hawkins & Abrams, 2007), many others talked about various, significant social ties within their communities. We used a combination of social capital and social network theories to interpret our findings and identify a theoretical typology that situates the social ties of formerly homeless individuals with SMI and substance abuse histories, within their communities. While social network theory emphasizes the structure and composition of an individual’s social relationships and its impact on an individual’s life (Robins & Kashima, 2008), social capital theory focuses on the resources obtained from these relationships, distinguishing between bonding and bridging social capital (Putnam, 2000). Individuals in our study could access bonding social capital, identified as resources obtained from close relationships, through social ties with family members. They also had access to bridging social capital, identified as resources derived from acquaintances or more professional relationships, through ties to service providers, places of employment and people they met in cultural spaces like churches, barbershops, and basketball courts. These ties seemed to be very important to their sense of belonging and reflect Granovetter’s concept of strength of weak ties (Granovetter, 1973). These weak ties, through service providers and acquaintances, have their own unique set of benefits that can be capitalized on in a potential intervention that specifically targets and harnesses an individual’s social connections (Powers, Jha, & Jain, 2016).

We also found that two broad themes emerged that illustrated the facilitators and obstacles to forming or maintaining social ties: (a) ties that bind and (b) “It gets in the way.” In this complicated and multidimensional picture of how participants relate to social ties, we found that certain facilitators and barriers cut across participants in this sample while others were specific to participants’ connections to the mental health service or mainstream communities. Employment emerged as an interesting connector between mental health services and mainstream communities in our study. Participants who described stronger ties to the mainstream community (partly due to volunteering or working) and participants who described stronger ties to the mental health service community via peer provider roles all spoke to the benefits of being employed, being productive members of the society, giving back in various ways and being respected in the work that they do, regardless of the setting. This finding can be traced back to the literature on supported employment, whereby, an individual who is offered support to gain and sustain employment show an array of positive outcomes (Dixon et al., 2010; Pahwa, Smith, McCullagh, Hoe, & Brekke, 2016). Additional benefits to employment as a peer provider such as improvements in mental and physical health; social, emotional, and spiritual well-being; and overall quality of life have been well documented in the literature (Solomon, 2004).

Many African American participants in the study spoke of the importance of church and spirituality in their lives, a vital connection to the mainstream community that went beyond their mental illness. Part of the role of traditional African American religious organizations has been inextricably linked to providing mutual aid and support to its community members including instrumental and emotional support to its community members (Armour et al., 2009) thus acting as a type of bridging social capital and an important part of social networks in the African American community. These types of supportive roles have been illustrated in the literature, in the experiences described by African American mothers with SMI (Carpenter-Song, Holcombe, Torrey, Hipolito, & Peterson, 2014) as well as across research on religion/spirituality in the African American community (Chatters, Taylor, Bullard, & Jackson, 2009; Utsey, Bolden, Lanier, & Williams, 2007). Furthermore, experiences of religion and spirituality in the African American community have been connected to improved depressive symptoms (Chatters et al., 2009) and quality of life outcomes (Utsey et al., 2007). Religious and spiritual coping have also been identified as a protective factor in risk and resilience models that attend to important culturally specific coping norms in the African American community (Utsey et al., 2007).

Another theme that especially resonated with the Black/African American or Hispanic/Latino participants was family as central to social connections, both as facilitators and as something that represented loss and hence, posing a barrier to forming meaningful ties. Most individuals who had deep ties to their family were connected to mental health programs for services; used family as a key source of support; and had ties to the mainstream community partly due to family ties. In addition, those that had the strongest ties to the mainstream community described reciprocity in their family relationships. For African Americans experiencing mental health challenges other than SMI, familial social ties have been shown to positively influence functioning, depressive symptoms, psychological distress and suicidal ideation through frequent contact, emotional support, and closeness (See Chatters, Nguyen, Taylor, & Hope, 2018, for a review of family relationships and mental health among African Americans). As for the impact of family relationships on African Americans with SMI, Armour et al. (2009), in their longitudinal, phenomenological study of African Americans in recovery from SMI, found one of four major themes for participants was “leaning on the supports that watch out for and over me.” Consistent with experiences of some of our participants, this theme included examples of family supports that illustrated how bonding capital, in the form of family relationships served as a source of strength and tangible support, facilitated recovery. Similarly, a study by Guada, Brekke, Floyd, and Barbour (2009) illustrated that Black/African American families provide support in various ways that support functioning in the community. Our findings taken together with existing literature have implications for interventions that should take into account cultural norms that may impact coping, community integration and recovery for African Americans with SMI.

Regardless of cultural background, participants more connected to mental health service community with no or few ties to the mainstream community spoke centrally about not having family members in their lives and depending on the mental health service community for socialization and support. Similar to our results, Bromley et al. (2013), in their qualitative study on individuals with SMI also found that participants in their study were deeply connected to peers from the 12-step programs and support groups, especially if they were in high intensity services.

Experiences of stigma or coping with symptoms of mental illness, as well as a history of substance abuse also impeded relationships with friends and/or family. These experiences speak to the obstacles that formerly homeless individuals with SMI and/or histories of substance abuse may have in creating meaningful social ties. These findings are consistent with previous literature whereby stigma against individuals with mental illness has been shown to impact the formation and maintenance of social ties as well as an individual’s sense of identity and belonging (Goffman, 1963; Padgett et al., 2008; Stefancic, 2014). Bromley et al. (2013) found that participants in their study, made decisions about whom to connect to on the basis of expectations of stigma and discrimination and even described “communities as enclaves they construct to avoid rejection” (p. 677). In addition, individuals with substance abuse and/or SMI may find themselves with volatile and often strained ties with friends and family members whose supports are often eroded by having their own troubles (Padgett et al., 2008) or whose own challenges with mental health and substance use create barriers to positive, reciprocal social relationships (Hawkins & Abrams, 2007). Furthermore, avoiding substance-using peers, as suggested by programs such as the 12-step program, lead to participants with substance abuse histories actively avoiding social ties that would hinder their recovery (Mohr et al., 2001).

Future research should focus on understanding both the impact of substance abuse history and experiences of stigma by individuals with SMI as well as the experiences of estranged family members related to someone with an SMI. Gaining such knowledge may contribute to formulating ways to support and encourage family reunification thus broadening social networks and enhancing social capital for individuals with SMI.

Limitations and Implications

Results of this study need to be interpreted with several limitations in mind. As our findings are based on the experiences of participants living in a large, urban city, we did not capture the experiences of individuals with SMI living in rural areas. Future research is needed to explore the unique perspective of social ties and communities in rural contexts. In addition, our study used data that were generated from one-time interviews and thus could have overlooked the longitudinal dynamics of participants’ social ties in the context of their communities. Finally, this is a secondary data analysis from a parent study focused on factors influencing recovery in addition to social ties. Nevertheless, participants spoke of their social relationships and involvement in what we defined as the mental health service and the mainstream communities. One of the critiques of secondary qualitative data analysis involves the lack of contextualization of the data. Keeping that in mind, the analysts, Pahwa and Smith of the present study maintained close and ongoing collaboration with Padgett, who was the principal investigator of the parent study.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the results of this study have implications for the current theoretical understanding of the importance of social ties in the lives of individuals with cooccurring mental health and substance abuse disorders. The current study integrates our understanding of the positive and negative aspects of social ties, and provides a framework that highlights the complicated nature of such ties, providing several practice implications. Conducting a detailed assessment of social relationships, including the positive and negative aspects of these relationships and their context within an individual’s community, would allow practitioners to provide more nuanced services to consumers. Individuals with SMI have access to less social capital than people without a mental illness (Webber et al., 2015). Identifying mechanisms by which individuals form social ties that facilitate these resources could lead to more nuanced services for individuals accessing these services. Practitioners could encourage consumers with positive social ties to maintain and strengthen these ties as well as provide supports for family members or individuals who may be in a caregiver role. For consumers who have little or no familial ties due to loss or estrangement, practitioners could assist or empower consumers to heal damaged relationships and/or build new ties. In addition, while acknowledging that not all ties are worth salvaging, consumers who have mentioned having lost connections or having no ties, could perhaps be reconnected to their old or dormant ties. As suggested by the literature, dormant ties could be an important protective factor for individuals and provide them with additional social capital resources (Levin, Walter, & Murnighan, 2011).

The current study also highlights the importance of religious organizations, especially African American churches, suggesting the need for culturally appropriate and personalized interventions. Although not all consumers will have connections to churches or other religious organizations, assessing for religious affiliations would provide an additional context to assist them in maintaining or strengthening existing social ties or reigniting lost ties to religious organizations for those that deem these connections as meaningful or supportive.

Finally, practitioners should not overlook the importance of forming and maintaining social ties with mental health peers. For consumers who draw a sense of confidence, belonging and community from these relationships, discussion about their importance and consumer choice about increasing social ties in the mainstream community and/or fostering existing relationships in the mental health service community should be consiered in treatment plans and goals that revolve around community integration. Research shows that a positive working relationship is necessary for individuals to feel engaged in services even while transitioning out of services (Pahwa & Kriegel, 2018). A good relationship with service providers has been linked to reduction in symptom severity, improvement of psychosocial functioning and overall higher life-satisfaction (Chen & Ogden, 2012). Padgett, Henwood, Abrams, and Davis (2008) have discussed how a good relationship between a provider and client go beyond just providing services and how “acts of kindness” from the provider could facilitate engagement and retention in services. Other scholars have echoed the importance of a good provider-–client relationship (Skelly et al., 2013) and as such should be harnessed for good service outcomes.

Conclusion

Taken together, these findings give a more complicated and multidimensional representation of the social ties within the contexts of the communities for formerly homeless individuals with SMI and cooccurring substance abuse problems. Furthermore, our finding has implications for interventions to increase formation of social ties that enhance social capital and as a result positively impact community integration.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:.This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (ROI MH084903)

Biographies

Rohini Pahwa, PhD, MSW, MA, is an assistant professor at New York University’s Silver School of Social Work. Her areas of interests include mental health services research, community integration, social networks, serious mental illness and mixed methods research.

Melissa Edmondson Smith, PhD, MSSW, is an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work. Her areas of interest include mental health services research, African Americans with or at-risk for serious mental illness, and the intersection of race/ethnicity and serious mental illness.

Yeqing Yuan, MSW, is a PhD candidate at the Silver School of Social Work at New York University. Her areas of interest include mental health, substance abuse, and homelessness.

Deborah Padgett, PhD, MPH, is a professor at the Silver School of Social Work at New York University. Her areas of interest include qualitative and mixed methods, mental health services research and homelessness.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Albert M, Becker T, McCrone P, & Thornicroft G (1998). Social networks and mental health service utilisation—A literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44, 248–266. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander BK (2003). Fading, twisting, and weaving: An interpretive ethnography of the Black barbershop as cultural space. Qualitative Inquiry, 9, 105–128. doi: 10.1177/1077800402239343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Armour MP, Bradshaw W, & Roseborough D (2009). African Americans and recovery from severe mental illness. Social Work in Mental Health, 7, 602–622. doi: 10.1080/15332980802297507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley E, Gabrielian S, Brekke B, Pahwa R, Daly KA, Brekke JS, & Braslow JT (2013). Experiencing community: Perspectives of individuals diagnosed as having serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 64, 672–679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter-Song EA, Holcombe BD, Torrey J, Hipolito MMS, & Peterson LD (2014). Recovery in a family context: Experiences of mothers with serious mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 37, 162–169. doi: 10.1037/prj0000041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, & Jackson JS (2009). Race and ethnic differences in religious involvement: African Americans, Caribbean blacks and non-Hispanic whites. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32, 1143–1163. doi: 10.1080/01419870802334531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, & Hope MO (2018). Church and family support networks and depressive symptoms among African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(4), 403–417. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FP, & Ogden L (2012). A working relationship model that reduces homelessness among people with mental illness. Qualitative Health Research, 22, 373–383. doi: 10.1177/1049732311421180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, … Kreyenbuhl J (2010). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Blanchard S, Neufeld A, & Strang VR (2009). The significance of social engagement in relocated older adults. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 1186–1195. doi: 10.1177/1049732309343956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (1963). Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter MS (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-442450-0.50025-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guada J, Brekke JS, Floyd R, & Barbour J (2009). The relationships among perceived criticism, family contact, and consumer clinical and psychosocial functioning for African-American consumers with schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal, 45, 106–116. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9165-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RL, & Abrams C (2007). Disappearing acts: The social networks of formerly homeless individuals with co-occurring disorders. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 2031–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood BF, Padgett D, Smith BT, & Tiderington E (2012). Substance abuse recovery after experiencing homelessness and mental illness: Case studies of change over time. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 8, 238–246. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.697448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DZ, Walter J, & Murnighan JK (2011). Dormant ties: The value of reconnecting. Organization Science, 22, 923–939. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N (2005). A network theory of social capital. In Castiglione D, van Deth J, & Wolleb G (Eds.), The handbook of social capital (Vol. 50). Oxford University Press Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Averna S, Kenny DA, & Del Boca FK (2001). “Getting by (or getting high) with a little help from my friends”: An examination of adult alcoholics’ friendships. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62, 637–645. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D (2016). Qualitative methods in social work research (Vol. 36). Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D, Henwood B, Abrams C, & Davis A (2008). Engagement and retention in services among formerly homeless adults with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse: Voices from the margins. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31, 226–233. doi: 10.2975/31.3.2008.226.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D, Henwood B, Abrams C, & Drake RE (2008). Social relationships among persons who have experienced serious mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness: Implications for recovery. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78, 333–339. doi: 10.1037/a0014155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahwa R, Bromley E, Brekke B, Gabrielian S, Braslow JT, & Brekke JS (2014). Relationship of community integration of persons with severe mental illness and mental health service intensity. Psychiatric Services, 65, 822–825. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahwa R, & Kriegel L (2018). Psychological community integration of individuals with SMI. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206, 410–416. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahwa R, Smith ME, McCullagh CA, Hoe M, & Brekke JS (2016). Social support-centered versus symptom-centered models in predicting functional outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7, 247–268. doi: 10.1086/686770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA (1992). Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of how people seek help. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 1096–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Powers BW, Jha AK, & Jain SH (2016). Remembering the strength of weak ties. The American Journal of Managed Care, 22, 202–203. Retrieved from https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2016/2016-vol22-n3/remembering-the-strength-of-weak-ties [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY, Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, & Kashima Y (2008). Social psychology and social networks: Individuals and social systems. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00240.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibusawa T, & Padgett D (2009). The experiences of “aging” among formerly homeless adults with chronic mental illness: A qualitative study. Journal of Aging Studies, 23, 188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skelly N, Schnittger RI, Butterly L, Frorath C, Morgan C, McLoughlin DM, & Fearon P (2013). Quality of care in psychosis and bipolar disorder from the service user perspective. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 1672–1685. doi: 10.1177/1049732313509896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P (2004). Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27, 392–401. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.392.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefancic A (2014). “If I stay by myself, I feel safer”: Dilemmas of social connectedness among persons with psychiatric disabilities in housing first (Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University). Available from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. (Accession No. 3644245) [Google Scholar]

- Tew J, Ramon S, Slade M, Bird V, Melton J, & Le Boutillier C (2012). Social factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: A review of the evidence. The British Journal of Social Work, 42, 443–460. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcr076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Bolden MA, Lanier Y, & Williams IIIO (2007). Examining the role of culture-specific coping as a predictor of resilient outcomes in African Americans from high-risk urban communities. Journal of Black Psychology, 33, 75–93. doi: 10.1177/0095798406295094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webber M, Reidy H, Ansari D, Stevens M, & Morris D (2015). Enhancing social networks: A qualitative study of health and social care practice in UK mental health services. Health & Social Care in the Community, 23, 180–189. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]