Abstract

Introduction

Migrants’ access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services is constrained by several individual, organisational and structural barriers. To address these barriers, many interventions have been developed and implemented worldwide to facilitate the access and utilisation of SRH services for migrant populations. The aim of this scoping review was to identify the characteristics and scope of interventions, their underlying theory of change, reported outcomes and key enablers and challenges to improve access to SRH services for migrants.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted according to the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) guidelines. We searched three electronic databases (MEDLINE, Scopus and Google Scholar) and carried out additional searches using manual searching and citations tracking of empirical studies addressing interventions aimed at improving access and utilisation of SRH services for migrant populations published in Arabic, French or English between 4 September 1997 and 31 December 2022.

Results

We screened a total of 4267 papers, and 47 papers met our inclusion criteria. We identified different forms of interventions: comprehensive (multiple individual, organisational and structural components) and focused interventions addressing specific individual attributes (knowledge, attitude, perceptions and behaviours). Comprehensive interventions also address structural and organisational barriers (ie, the ability to pay). The results suggest that coconstruction of interventions enables the building of contextual sensitive educational contents and improved communication and self-empowerment as well as self-efficacy of migrant populations, and thus improved access to SRH.

Conclusion

More attention needs to be placed on participative approaches in developing interventions for migrants to improve access to SRH services.

Keywords: Health systems evaluation, Maternal health, Systematic review, Health education and promotion, Intervention study

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Diverse types of interventions have been developed to improve access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for migrants.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This review provides a taxonomy of interventions addressing different individual, organisational and structural barriers to access to SRH services care for migrant populations. This study highlights the characteristics of interventions, including outcomes, underlying theories of changes and implementation barriers and facilitators.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This review highlights intertwined institutional, organisational and individual gaps in the implementation of interventions addressing migrant SRH. These gaps need to be addressed in health planning programmes.

Introduction

The past two decades have seen a rapid increase in the number of migrants from 153 million in 1990 to 281 million in 2020 according to the International Organization of Migrants (IOM).1 Migrant women in host countries face several challenges such as poor access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, interrupted continuum of care, negative interactions with health workers and gender-based violence (GBV).2 3 This often leads to adverse SRH outcomes such as pregnancy complications, stillbirths, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unsafe abortions, miscarriages and sexual abuse in the workplace and in refugee camps.2 Over the past two decades, migrant women’s rights to SRH and gender equality have gained momentum and become an area of interest for researchers, policy-makers and practitioners, as well as the global community.4 Interest in SRH and gender equality has grown on a global scale. These interests were institutionalised during the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action in Cairo and the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, which urged governments worldwide to improve universal access to SRH rights.5 6 The World Health Assembly Resolution WHA70.15 in 2007 and the UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health strengthened global policy engagement regarding migrant women’s SRH rights.7 8 Improving the quality of care in SRH for migrants is, therefore, a cross-cutting issue and is considered to be a key driver of women’s empowerment and an essential step toward achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and universal health cover.9 Despite ongoing efforts, migrants’ access to SRH services remains constrained by a multitude of individual, organisational and broader health system and structural barriers. Individual-level barriers include, for instance, knowledge, health literacy, trust in healthcare services, culture and language, which often lead to stigmatisation and poor communication with providers. Organisational and structural barriers include health system factors, the lack of health insurance, restricted access for undocumented migrants10 and the unaffordable cost of medicine particularly in non-universal health systems.11 Recently, an increasing number of cost-effective interventions and public health programmes have been designed and implemented to address access and use of quality SRH services. These programmes provide various SRH services aimed at preventing sexually transmitted diseases and unintended pregnancies, reducing maternal morbidity and mortality and addressing GBV.12 Reported effects at individual levels include active participation in the workplace and in income-generating activities, women empowerment, educational achievement and health systems outcomes such as reduced infant and maternal mortality.13 14 While in-depth explorations of specific programmes and interventions have been performed, there remains a paucity of knowledge regarding the scope and the outcomes measured by SRH migrant access interventions.15 16 Moreover, the available evidence suggests that there are mixed effects of SRH interventions depending on the setting. Few studies to date have addressed the characteristics and range of SRH interventions for migrants, their underlying theory of change, reported outcomes and key enablers and challenges.16 This scoping review aims to address this gap.

Methods

We adopted the scoping review methodology as defined by Arksey and O’Malley and refined by Levac et al.17 18 The process includes the following six stages: specification of the research question; identification of the relevant literature; selection of studies; charting the data; summarising, synthesising and reporting the results; and conducting expert consultation.

Specification of the review question

This scoping review aims to answer the following research questions: What is the range of interventions aimed at improving access and utilisation of SRH services by migrants? What are their characteristics (duration, participants, components and outcomes) and their reported effects, and how and under which conditions do they bring about the expected and/or unexpected outcomes? What are the enablers and challenges that facilitate or hinder their implementation and their sustainability?

Identification of relevant studies

Three electronic databases, MEDLINE via PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar were searched for relevant studies. The eligibility criteria were as follows: empirical studies that report on interventions addressing migrants’ access to SRH services published in Arabic, French or English between 4 September 1994 and 31 December 2022. The search strategy was devised using the PCC framework:19 Population (migrants OR refugees OR asylum-seekers OR internally displaced people), Context (any country), Concept (health services accessibility AND SRH (see online supplemental file 1). We performed additional searches of the grey literature using snowball search and citation tracking and manual searches of institutional websites of health ministries and UN organisations promoting the health of migrants. Studies that reported broadly defined interventions with no description of the details (eg, participants activities) were not included in this review.

bmjgh-2023-011981supp001.pdf (354.6KB, pdf)

Study selection

The search strategy was designed and validated by ZB and performed by OB. The retrieved articles were imported into Mendeley Reference Manager and duplicates were removed. The quality assurance of the selection and extraction process was ensured by ZB.

Charting the data

We adopted the conceptual framework of Levesque et al as an initial framework for data extraction and coding themes.20 The Levesque framework is a comprehensive multidimensional framework that addresses structural and organisational barriers (approachability; availability; acceptability; availability and accommodation; affordability and appropriateness) and individual factors (ability to perceive, seek, reach, pay and engage). These factors underlie access to healthcare (see online supplemental file 1).20

To describe the general characteristics of interventions, we used a standardised extraction form adapted from the literature.21 22 We continuously refined our extraction forms to inductively reflect on themes. The data extraction form included the following variables: author, year of publication, location of study, methods (study design, study population and settings), intervention characteristics (duration, aim, participants, programme components, educational resources, underlying theory of change, outcomes, barriers and facilitators) and the five accessibility and individual abilities dimensions.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Data analysis was carried out during research team meetings, and both a tabular and narrative summary of the study findings were provided. Summation and synthesis of results using thematic analysis were guided, but not restricted, by the initial Levesque framework. We were sensitive to emerging themes during the coding. Finally, we followed the reporting guidelines for scoping reviews set by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.23

Consulting with experts and key stakeholders

To enhance and validate our findings, we shared our scoping review with various stakeholders (Ministry of Health and Social Protection (MHSP), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, NGOs, UNFPA and UM6SS) in a workshop organised on 17 October 2022. During this workshop, we received feedback on the relevance of intervention mapping and the contextual relevance of interventions to the context of Morocco. We also added additional grey literature following suggestions from participants. This scoping review informed the design of suitable interventions to be implemented by the MHSP in Morocco.

Results

Search results

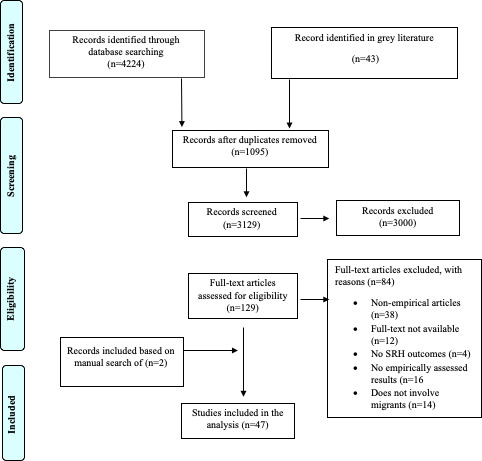

The database search yielded 3129 citations after removal of duplicates (figure 1). In addition, 43 records were identified through grey literature searches. Title and abstract screening resulted in 129 references and two articles identified through manual searching. A total of 47 articles fit our inclusion criteria, of which 40 were peer-reviewed articles and seven were grey literature records. The list of excluded articles and the reasons for exclusion are presented in online supplemental file 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; SRH, sexual and reproductive health.

Most included studies used a quantitative study design to evaluate migrant interventions: quantitative surveys,12 randomised controlled trials,10 cluster-randomised studies,1 postcontrol studies4 and a cohort study.4 Few studies were based on qualitative designs.8 Only one study used a mixed-method design.

Intervention characteristics

We identified several types of SRH migrant access interventions, of which the majority targeted migrants and were educational in nature (66%) (table 1). A detailed overview of the activities within each intervention is shown in table 2, online supplemental file 2. In the following section, we identify key characteristics of the interventions (context of the interventions, reported outcomes and scope of the interventions according to the Levesque framework)(table 2).

Table 1.

Types of intervention to improve migrants’ access to sexual and reproductive health services

| First author (year) | Educational intervention | Peer education and support | Social marketing and behaviour change campaigns | Healthcare workforce technical training | Cultural competency training of health staff | Training of lay health workers | Outreach screening | Health financing and coverage | Supply of products, equipment, and drugs | Infrastructure improvement |

| Zhang et al, 201347 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Worth et al, 200343 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| White et al, 201637 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Vu et al, 201628 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Soltani et al, 202030 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Silvestre et al, 201633 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Shah et al, 202024 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sánchez et al, 201234 | ||||||||||

| Sánchez et al, 201331 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Rosenberg and Bakomeza, 201739 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ramos et al, 201044 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Poudel et al, 200732 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Olshefsky et al, 200746 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| O’Connell et al, 202249 | ✓ | |||||||||

| McGinn et al, 200650 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Martijn et al, 200445 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Li et al, 201456 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lahuerta et al, 201791 | ||||||||||

| Kocken et al, 200125 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hovey et al, 200735 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| He et al, 201229 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Huang et al, 201492 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Chemtob et al, 201955 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Fernández-Balbuena et al, 201554 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Alam et al, 201693 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Bahromov and Weine, 201126 | ✓ | |||||||||

| O’Laughlin et al, 202151 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lin et al, 201061 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Miller et al, 199538 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Stam et al, 199736 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Zhu et al, 201427 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Johnsen et al, 2020, 2021;77 78 94 95 Villardsen et al, 201642; Ramsussen et al, 202196 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gany and Thiel de Bocanegra 199641 | ✓ | |||||||||

| UNHCR, 202197 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Moulin, 201452 | ✓ | |||||||||

| ALCS, 201753 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017,57 2019,59 201870 202071 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| WHO, 202160 | ✓ |

*Different publications reporting on the same intervention.

Table 2.

Scope of interventions according to Levesque’s framework

| First author, year (reference) | Approachability | Acceptability | Availability | Affordability | Appropriateness | Ability to perceive | Ability to seek | Ability to reach | Ability to pay | Ability to engage |

| Zhang et al, 201347 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Worth et al, 200343 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| White et al, 201637 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Vu et al, 201628 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Soltani et al, 202030 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Silvestre et al, 201633 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Shah et al, 202024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Sánchez et al, 201234 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Sánchez et al, 201331 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Rosenberg and Bakomeza, 201739 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Ramos et al, 201044 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Poudel et al, 200732 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Olshefsky et al, 200746 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| O’Connell et al, 202249 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| McGinn and Allen, 200650 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Martijn et al, 200445 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Li et al, 201456 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lahuerta et al, 201791 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kocken et al, 200125 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Hovey et al, 200735 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| He et al, 201229 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Huang et al, 201492 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Chemtob et al, 201955 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Fernández-Balbuena et al, 201554 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Alam et al, 201693 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Bahromov and Weine, 201126 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| O’Laughlin et al, 202151 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lin et al, 201061 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Miller et al, 199538 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Stam et al, 199736 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Zhu et al, 201427 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Johnsen et al, 2020, 202177 78 94 95; Villardsen et al, 201642; Ramsussen et al, 2021* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Gany and Thiel de Bocanegra,199641 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| UNHCR, 202197 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Moulin, 201452 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ALCS, 201753 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017,57 2018,70 2019,59 202071 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WHO, 202160 | ✓ | ✓ |

*Different publications reporting on the same intervention.

bmjgh-2023-011981supp002.pdf (562.3KB, pdf)

Context of the interventions

Countries

The majority of included studies were carried out in the USA (n=6), China (n=6) and Uganda (n=4). Others were conducted in the Netherlands (n=2), Sweden (n=2), Guinea (n=2) and Thailand (n=2). Some studies were carried out in more than one country. Single studies were carried out in the following countries: Nigeria, Mexico, Myanmar, Denmark, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Australia, New Zealand, Lebanon, Israel, Nepal, Pakistan and Russia (see online supplemental file 1).

Community and proximity places

Some interventions were carried out in community settings (n=3). Others were conducted in multiple settings. Most interventions were implemented in areas close to migrants or in areas highly frequented by migrants such as community events,24 mosques or cafes for Muslims,25 intercity transportation26 or the workplace.27–29 One intervention included the use of volunteers to transport beneficiaries to intervention sites. In refugee camps, one active case-finding intervention included home visits by community female refugees with other refugees. For vulnerable subgroups such as sex workers, one intervention described the deployment of a free night clinic to host and address the healthcare and psychosocial needs of migrant sex workers.

The interventions were implemented mostly in social communities (n=20). Few were implemented in other settings (workplace (n=3) or healthcare facilities (n=4)). Some interventions comprised at least two different settings (communities and health facilities (n=4), communities and households (n=1), individuals (n=1) and multiple settings (n=2).

Reported outcomes

The majority of the included studies addressed both individual and institutional accessibility outcomes. Most interventions addressed the approachability and acceptability dimensions, and most outcomes were related to the abilities to perceive, engage and reach (table 2).

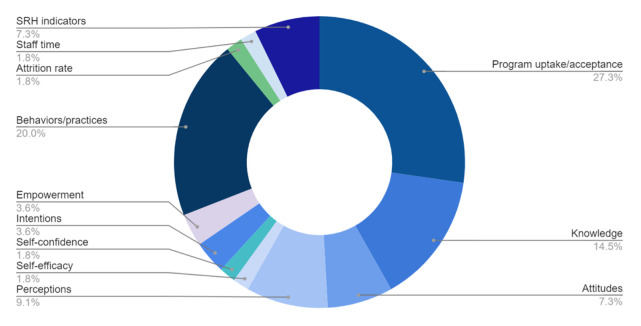

Most reported outcomes can be summarised into individual, organisational and institutional level outcomes (figure 2). The individual outcomes mainly included knowledge, attitudes, behaviours (KAB) and psychological outcomes. Few studies, however, addressed key psychological individual mechanisms such as self-empowerment, self-confidence and self-efficacy.30 31

Figure 2.

Individual, organisational and institutional-related outcomes. SRH, sexual and reproductive health.

Knowledge-related outcomes included knowledge about SRH and HIV/AIDS as well as about healthcare services (eg, HIV testing sites and contraception provision services).26 32 Behaviour-related outcomes included healthcare-seeking behaviour such as visits to healthcare facilities, getting tested for HIV and gynaecological check-ups and changes in risk behaviours (visiting brothels, multiple sexual partners) or protective behaviours (condom use).26 28 32–34

The migrants’ perception outcomes included benefit and risk perception related to HIV and protective behaviours (ie, condom use, respectively).25 35 Some studies also measured intentions to engage in protective behaviour or share the acquired knowledge with peers or family members.36 Only four studies measured SRH indicators such as the number of skilled births, the rate of unintended pregnancies and pregnancy complications.37 38 At the organisational level, the scholars reported mostly programme uptake and acceptance of intervention, often used interchangeably34 39 (figure 2).

Taxonomy of the interventions

We can categorise interventions, according to the underlying mechanisms of change40 into five categories of intervention: (1) educational interventions including social marketing campaigns and peer education, (2) participatory (coproduction and codesign of the intervention with recipients), (3) theory-driven interventions based on an explicit psychological or organisational theory of change), (4) implementation-oriented interventions focused on maximising outreach and screening) and (5) multifaceted or comprehensive interventions including various types mentioned above (see table 1 and online supplemental file 2 table 4).

Dissemination and educational interventions

A variety of educational tools were used across interventions such as pamphlets, leaflets, slides, posters, theatrical role play,35 41 game shows,35 health provider maps,28 smartphone applications,29 42 videos, SMS, hotlines, face-to-face counselling,29 use of letters sent by migrants and friends and family members.32 36 Educational sessions were often delivered in the native language of the migrants, using appropriate language and terminology.30 43 Most scholars considered peer-led education as a key driver to increase SRH-related KAB.25 29 30 32 35 36 39 43–45

Other interventions used social marketing to disseminate information based on codeveloped culturally sensitive material about SRH topics to migrants.24 33 46 Only one intervention used a commercial advertising agency and multiple communication channels (ads on radio stations, social media, dating apps, community outreach events, billboards, personalised toll-free line with trained call operators, etc) to personalise education messages and improve referral to HIV testing clinics.46 One campaign addressed barriers to seeking healthcare at the individual level.24 This was achieved through the development of audiovisual materials that reflect the barriers to HIV testing that individuals experience.24

Participatory interventions

Most of the interventions included various forms of participatory approaches during the design and/or implementation of the SRH interventions. Communities were involved in codevelopment of culturally appropriate materials,43 the delivery of the training to peers,25 26 codevelopment of educational and communication materials,43 47 recruitment of participants,44 resource mobilisation activities and the delivery of the intervention. The majority were oriented towards communities. Few were focused on individual access challenges (see online supplemental file 2, table 2 and figure 2). Codesign of interventions with migrants is considered to be an effective strategy in health promotion and education as well as for improving participation and adherence of migrants.33

We also found that the authors used different perspectives when referring to community participation (see table 2 and figure 1 in online supplemental file 2). We used the Arnstein ladder of participation48 to identify what form of participation the authors refer to. The ladder describes a continuum of participation based on the extent of citizen power in adapting the programme. The ladder includes non-participatory approaches rungs (manipulation, therapy) and tokenism rungs consisting of allowing citizens to express their opinions (informing, consultation or placation). The highest participation rungs correspond to increased degrees of citizen power (partnership, delegation of power and citizen control) (see figure 3; online supplemental file 2).48 Our review showed that most included studies used placation (placing migrant representatives in committees) as the main form of participation.25 30–32 35 37 39 41 44 49–53 Few studies genuinely engaged in actual partnerships with power delegation to migrant populations34 38 46 54 (see table 2, online supplemental file 2).

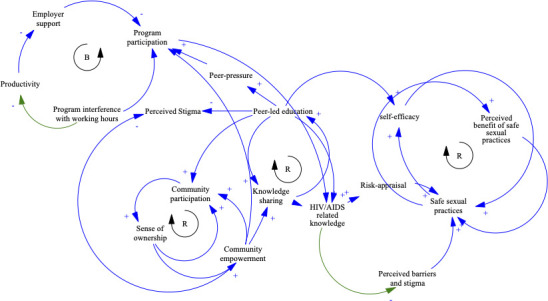

Figure 3.

Causal loop diagram of how migrants’ SRH access intervention may work. B, balancing feedback loop; R, reinforcing feedback loop. SRH, sexual and reproductive health.

Communities were involved during different phases, comprising during the intervention design, codevelopment of culturally sensitive educational material, peer-education sessions and during the delivery of support services during pregnancy and after childbirth.30 38 43 44 47 Few interventions involved communities in the sustainability of migrant SRH interventions.55

Co-design of the intervention with communities is essential in enhancing their acceptability and appropriate use of cocreated knowledge, and it enhances common understanding of interventions and effective communication with migrants.34

The participatory interventions included the training of migrants and refugees in delivering prevention messages, performing physical examinations, HIV testing and counselling, pregnancy delivery and antenatal care. This also includes the training of community health workers as skilled-birth attendants (SBAs), who are qualified health workers who educate refugee mothers.37 44 Ramos et al assert that trained female migrants, known as ‘promotoras’ (outreach coordinators), proved successful in delivering HIV prevention counselling, referral and testing and in expanding the programme reach by using the women’s own social networks.44

While some interventions described training of community health workers in the delivery of the technical aspect of care,27 56 other interventions aimed to increase the acceptability of existing healthcare services through culturally sensitive training of healthcare providers and non-technical staff (receptionists and social workers).41 In Morocco, a toolkit on Migrant Health has been developed and used to train healthcare professionals in delivering culturally sensitive and adequate care to the migrant population.57 Content-wise, the training concerned improving the perception of healthcare access from a human rights-based perspective, cross-linguistic and cross-cultural interviews and interpersonal skills such as working with interpreters, and building contextual knowledge about migrant health concerns and family dynamics.41

Implementation-oriented interventions

Implementation-oriented interventions focus on the delivery of SRH care and maximising the outreach migrant SSR interventions. This type of intervention includes, for instance, the training of lay health workers; outreach screening; health financing and coverage; supply of products, equipment and drugs and infrastructure improvement (see table 1).

Three studies reported implementation interventions addressing outreach screening interventions (active case finding for TB and HIV58 and community-based voluntary testing for HIV).47 54 All studies reported high acceptability and attendance rates among migrants.54 58 To improve adherence to the programmes, some interventions used compensation for participants in the delivery of interventions (ie, sending letters to their peers).36

Other implementation studies addressed the financial accessibility barriers. Most of these integrated migrants within existing schemes of universal health coverage (UHC) (eg, medical assistance regime for the vulnerable and poor (Ramed) in Morocco59 and Universal Public Health Insurance in Iran).60 UHC schemes cover hospitalisation as well as para-clinical and outpatient services (ambulatory medical consultations, radiology, laboratory tests and medication costs). Some interventions also directly targeted individual migrants using self-paying premiums or cash transfer programmes funded by the UNHCR59 or by public–private partnerships (pharmaceutical industries in Israel) to improve access to antiretroviral therapy.55

Theory-informed interventions

Only five studies described an underlying behavioural theory of change that guided the development of the design of interventions25 31 45 46 61 (see box 1 and table 3 online supplemental file 2). Kocken et al described a peer-led AIDS education campaign designed in line with the theoretical guidance of the Health Belief Model as defined by Janz and Becker and Rosenstock et al.62 63 They addressed individual psychological mechanisms described in the Health Belief Model, including perceived threat (susceptibility and severity), perceived benefits and barriers, self-efficacy and cues to action, and the likelihood of preventive action.25

Box 1. Definitions of behavioural change theories in the included studies.

The Health Belief Model refers to a behavioural theory of change that explains health risk-reducing behaviour. It explains why individuals are likely to take preventive action when they perceive that they are personally susceptible, when the risk is perceived as serious and when there are fewer costs than benefits to engage in protective actions.62 63 68

The theory of planned behaviour defines human behaviour as the direct consequence of intentions. They are determined by attitudes towards behaviour, social norms, beliefs and perceived normative behavioural control.68 98

Protection motivation theory provides an explanatory account of how environmental sources, messages and verbal persuasion trigger cognitive processes in response to messages of fear appeals, and health threats. This includes cognitive appraisal of maladaptive practices (threat appraisal, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards), adaptive responses (coping appraisal, self-efficacy and response cost). This leads to protection motivation and action (or inhibition) of action.67 68

The transtheoretical model suggests that behavioural changes occur in five sequential stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance). It also identifies change processes such as consciousness raising, dramatic relief, self and environmental evaluation, etc.68 69

The social cognitive theory posits that the behaviour of people is the result of an interaction between the behaviour, the environment and personal factors. In addition, the theory suggests that human actions are determined by five capabilities: symbolic thought, forethought, observational learning, self-regulation and self-reflection.68 99

Martijn et al described an intervention aimed at increasing condom use among immigrants based on the theory of planned behaviour, which is considered to be a suitable theory to guide interventions for minorities and to predict condom use.45 The authors asserted that they designed the intervention to increase knowledge of HIV transmission and alter people’s attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control towards condom use. The authors referred to seminal work by Ajzen,64 and to similar applications in condom use prevention programmes.65 66

Danhua et al asserted that they used the protection motivation theory, as defined by Rogers (1975),67 involving a combination of appraisal of threat and coping processes, in an HIV-risk reduction intervention.61 The authors combined protection motivation theory (self-efficacy, response cost and efficacy, intention, etc) with motivational interviewing and peer counselling (see online supplemental file 2, Table 3).67 68

Other scholars used the transtheoretical behavioural stages of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, relapse and termination) to design social marketing campaigns for HIV/AIDS risk reduction.46 For instance, Olshefsky et al designed an intervention to raise the awareness of migrants regarding their risk of HIV infection (precontemplation). They used social marketing campaigns to trigger learning and motivation (contemplation). This may have led to triggering of health-seeking behaviour (preparation, actions and process of changes). The authors specifically referred to Prochaska and DiClemente et al.69 Sanchez et al31 used social cognitive theory to design an intervention called ‘Adapted-Stage Enhanced Motivational Interviewing’.31 The intervention was coproduced with Latino migrants living in the USA. It aimed to address personal cognitive factors (awareness of the risk for HIV/AIDS) and promote HIV testing services in four local communities.

Multifaceted interventions

Finally, there were some interventions that integrated different types of interventions (individual, organisational and institutional level interventions). These include interventions that addressed both individual knowledge, skills and behaviours, as well as organisational (eg, training health workers) and institutional barriers (eg, financial accessibility)53 57 59 70 71 (see table 1 and online supplemental file 2, Table 4).

Only a few studies reported utilisation outcomes.38 46 54 Miller et al reported increased antenatal care visits by migrant women following training of SBAs compared with untrained birth attendants.38 In another study by Fernández-Balbuena et al, setting up free-of-charge testing and counselling for HIV in non-conventional settings resulted in higher attendance of vulnerable groups such as migrants and sex workers.54 In another study, Olshefsky et al reported increased HIV testing at partner clinics following a social marketing campaign.46

Discussion

Our scoping review sets out to examine the characteristics and scope of health interventions targeting migrant populations in the published and grey literature and to describe intervention characteristics, mechanisms of change, reported outcomes and key enablers and challenges. This scoping review included 47 studies of interventions aimed at improving access and utilisation of SRH services by migrants (including refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced people).

There are different types of migrant interventions (implementation, participative, theory-informed, educational and dissemination interventions and multifaceted comprehensive interventions). Implementation-based interventions focus on improving the outreach of programmes to increase access to SRH services. Most interventions aimed to educate migrants about SRH-related issues and services. The key outcome measures included KAB.

Peer education was used as an educational method across several interventions. Peer educators are often mobilised to link providers with hard-to-reach beneficiaries. It is often utilised in interventions aiming to improve adolescent SRH. While peer-led interventions resulted in increased knowledge and attitude-related outcomes, the evidence of their effectiveness remains inconclusive.72 These initiatives are often used to address language or cultural barriers. Our review shows that differences in socioeconomic status and level of acculturation between peer educators and intervention participants are often considered to be barriers hindering effective communication (eg, feelings of not being understood and of not being sufficiently involved).

Community participation was considered to be an enabling factor in many outreach interventions. It includes the institutionalisation of disease prevention committees comprising of community leaders and community health workers,47 or supporting the creation of local organisations engaged in education and advocacy efforts.55

Our scoping review showed, in line with other reviews,72 that there is still a degree of conceptual heterogeneity around the concept of community participation in the included studies.73–75 Thus, focusing on intervention mechanisms and components, and using appropriate frameworks will facilitate future reviews of community participation approaches76 in addressing migrants’ access to SRH services. In our review, the Arnstein ladder of citizen participation provided a suitable framework to categorise the various forms of community participation as referred to by the authors.48

Only a few interventions were aimed at training health workers in providing healthcare to migrants.72 Among these, some studies focused on the technical aspect of capacity building, such as the training of SBAs and migrant health workers.37 Lack of cultural competency, non-inclusion of social workers and non-technical staff are often considered to be barriers to effective communication and the delivery of culturally sensitive support SSR.41 59 For instance, some medical administrators were requiring unnecessary documentation regarding migrant status, which reduces migrants’ access to essential SSR care. Thus, cultural competency capacity building of technical and non-technical health staff across the continuum of care is essential to maintaining appropriate access to SSR care for migrants.

Cultural competency training is crucial to alter the perspectives and attitudes of healthcare personnel and to overcome cultural barriers. However, some studies have shown that despite having a culturally competent workforce, the utilisation of services is determined by the lack of appropriate insurance coverage.27 41 53 57 77 Moreover, higher benefits were reported among migrant patients who had previously accessed services.78 This suggests that multifaceted comprehensive interventions are more likely to reach long-term SRH outcomes.79 The scholars added that interventions may not be used appropriately when migrants are experiencing social stigma, discrimination, corruption or language barriers despite being covered by a UHC scheme.60

Causal loop diagramming of the behavioural theory of change

Scholars often assert that well-designed and effective interventions should be guided by behavioural change theoretical frameworks.80 In this review, only five studies reported behavioural theories of change that guided the design and implementation of interventions. Concerns were also raised about the contextual adaptability of behavioural theories of change developed mainly in the North to the context of low-income and middle-income countries.61 Scholars need to contextualise existing theories of change by appropriate adaptation to local contexts and social norms.81 Scholars also need to explicitly report on theories of change underlying the interventions when studying SSR migrant interventions.82

To further develop our understanding of the complex intertwined relationship between intervention components and their outcomes, and to make sense of the underlying behavioural theories of changes reported by the authors, we used the causal loop diagram (CLD) methodology.83 In particular, we focused on individual psychological mechanisms and community empowerment as key mechanisms for increasing programme outreach and behaviour change related to SRH (figure 3).

This CLD describes the feedback processes and interactions between multiple short-term and medium-term outcomes of the intervention in the included studies. Community empowerment emerged as an essential driver of community engagement. Engaged communities develop a sense of ownership, which in turn increases collective empowerment and their willingness to engage collectively in SRH interventions.

Our scoping review also shows that peer support and education enhance migrant self-efficacy, thereby increasing the likelihood of adopting safe SRH practices and changing risk behaviour through positive changes in the self-confidence, self-efficacy, and self-worth of migrants.

Maintaining confidentiality and discretion are essential contextual factors that trigger the effectiveness of peer education and enhance its acceptability by migrants and particularly among stigmatised minority subgroups (eg, HIV-positive individuals and sex workers).

Our review shows also that stigma negatively impacted the perceived value of peer education, thereby decreasing its acceptability. Peer pressure has also been identified as an important mechanism of behaviour change. Peer-led education often increases knowledge sharing and dissemination with peers, family members and the community, which in turn increases peer pressure to adopt safe SRH practices. This is particularly the case for high-risk subgroups such as sex workers and for seasonal male migrant workers who often develop intentions to engage in healthy practices on receiving advice and information from their spouses. In workplace settings, interventions targeting migrant workers can interfere with working hours, which leads to a loss of productivity as perceived by employers. This in turn leads to less employer support, which ultimately leads to decreased programme participation. These complex intertwined relationships are depicted in figure 3. Reinforcing feedback loops are effects that vary in a similar manner. Balancing feedback loops are interactions that counterbalance each other.

Sustainability and follow-up

Only one study had follow-up longer than 2 years. Thus, it is unclear whether any short-term benefits of most other interventions would have been sustained. In addition, cost-effectiveness analyses were rarely reported.

Strengths and limitations

Our review also has specific strengths and limitations. Most interventions measured changes in knowledge, attitudes and intended behaviours rather than measuring actual behaviours84 (intention to action gaps). Few studies reported utilisation outcomes.84 As described by Arksey and O’Malley,17 we attempted to provide a broad overview of interventions addressing migrants’ access to SRH services. However, we do not claim to be comprehensive as we needed to achieve a balance between the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the review. Our included studies were exclusively written in English or French. We may also have missed relevant data published in other languages, particularly in countries with large numbers of migrants (eg, Spain and Portugal). In this review, we did not assess the quality of the included evidence, as the aim was to describe the range and scope of migrant interventions and their mechanisms of change. We did, however, assess the likelihood of conflicts of interest in the included studies, as this is often associated with overestimates of outcomes in the healthcare85–87 and social sciences.88 With the exception of Rosenberg and Bakomeza,39 who reported that SRH interventions were assessed by an external evaluator, most studies involved evaluators that either belong to or have been involved in a research unit funded by the implementing organisation (see table 1, online supplemental file 2). Although there is no consensus in regard to measuring conflict of interest, caution is required when interpreting the reported outcomes.88

Another limitation of our scoping review is that only two studies reported the role of the legal status of migrants in hampering their access to health insurance59 60 and SRH services.59 60 Future studies will need to assess the effectiveness of SRH interventions in different subgroups of migrant populations.

Quantitative designs and RCTs were the most used study designs. Therefore, more qualitative, theory-driven evaluations,89 multiple embedded case studies90 and qualitative evidence synthesis are needed. These designs are better suited for unravelling the contextual barriers and facilitators, the mechanisms of change, as well as the structural and underlying power dynamics that enable or hinder the functioning of interventions.

Conclusion

Our scoping review has revealed a broad range of migrant SRH interventions that addressed both individual outcomes (knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, practices and intentions) and organisational outcomes. Most interventions were educational and information dissemination interventions. There has been strong interest in the past decade in participatory action research interventions that have proven useful in fostering the self-efficacy of migrants, self-empowerment of communities and better adherence to SRH access-related interventions. Few evaluation studies of migrant interventions were based on a behavioural theory of change; thus, we urge scholars and evaluation practitioners, and managers, to make use of the existing behavioural theories of change that have proven to be effective in addressing individual, organisational and community barriers to access to SRH care. More attention needs to be placed on theory-driven evaluation such as realist evaluation and qualitative studies to better understand the causal processes underlying the effectiveness of SRH interventions for migrant populations rather than simply reporting descriptive data on enablers to improve access to SRH services.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Vincent De Brouwere, Professor Emeritus at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium, for their feedback and critical review of the manuscript prior to submission.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @drbelrhiti

OB and ZB contributed equally.

Contributors: Conception or design of the work: ZB and OB. Data collection: OB and ZB. Data analysis and interpretation: OB, ZB and SZ. Drafting the article: OB and ZB. Critical revision of the article: SZ and ZB. ZB accept the full responsibility for the work and /or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This research was funded by IDRC Canada grant no. 109 514-001.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Not required.

References

- 1.International Organisation of Migration . Interactive world migration report. 2022. Available: https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2022-interactive/ [Accessed 9 Oct 2022].

- 2.Adanu RMK, Johnson TRB. Migration and women’s health. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;106:179–81. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castañeda X, Ruelas MR, Felt E, et al. Health of migrants: working towards a better future. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2011;25:421–33. 10.1016/j.idc.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gil-Salmerón A, Katsas K, Riza E, et al. Access to Healthcare for migrant patients in Europe: Healthcare discrimination and translation services. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:7901. 10.3390/ijerph18157901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNFPA . International conference on population and development. 2022. Available: https://www.unfpa.org/icpd [Accessed 13 Aug 2022].

- 6.UN Women . Fourth World Conference on Women [Internet]. Beijing, 1995. Available: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/health.htm [accessed 13 Aug 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. The UCL-Lancet Commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Seventieth world health assembly: promoting the health of refugees and migrants. 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHA70.15

- 9.United Nations . THE 17 GOALS | sustainable development [Internet]. 2022. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- 10.Mandroiu A, Pavlova M, Groot W. Sexual and reproductive health rights and service use among Undocumented migrants in the EU: a systematic literature review. 2023. Available: https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr628649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Gil-González D, Carrasco-Portiño M, Vives-Cases C, et al. Is health a right for all? an umbrella review of the barriers to health care access faced by migrants. Ethn Health 2015;20:523–41. 10.1080/13557858.2014.946473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises . Minimum initial service package [Internet]. 2018. Available: https://iawg.net/resources [Accessed 15 Aug 2022].

- 13.Bloom SS, Wypij D, Das Gupta M. Dimensions of women’s autonomy and the influence on maternal health care utilization in a North Indian city. Demography 2001;38:67–78. 10.1353/dem.2001.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pande RP, Namy S, Malhotra A. n.d. The demographic transition and women’s economic participation in Tamil Nadu, India: A historical case study. Taylor and Francis Group doi:101080/1354570120191609693 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyung Kim S, Park S, Ahn S. Effectiveness of Psychosocial and educational prenatal and postnatal care interventions for married immigrant women in Korea: systematic review and meta-analysis. Asia Pac J Public Health 2017;29:351–66. 10.1177/1010539517717364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghimire S, Hallett J, Gray C, et al. What works? prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections and blood-borne viruses in migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, northeast Asia and Southeast Asia living in high-income countries: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1287. 10.3390/ijerph16071287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. implementation science [Internet]. 2010. Available: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.The Joanne Briggs Institute . The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology 601 for JBI Scoping Reviews [Internet]. 2015. Available: https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/jbi/docs/reviewersmanuals/scoping-.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:18. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belrhiti Z, Booth A, Marchal B, et al. To what extent do site-based training, mentoring, and operational research improve district health system management and leadership in Low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 2016;5:70. 10.1186/s13643-016-0239-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping reviews (PRISMA-SCR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah HS, Dolwick Grieb SM, Flores-Miller A, et al. Sólo se Vive Una Vez: the implementation and reach of an HIV screening campaign for Latinx immigrants. AIDS Educ Prev 2020;32:229–42. 10.1521/aeap.2020.32.3.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocken P, Voorham T, Brandsma J, et al. Effects of peer-led AIDS education aimed at Turkish and Moroccan male immigrants in the Netherlands. A randomised controlled evaluation study. Eur J Public Health 2001;11:153–9. 10.1093/eurpub/11.2.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahromov M, Weine S. HIV prevention for migrants in transit: developing and testing TRAIN. AIDS Educ Prev 2011;23:267–80. 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu C, Geng Q, Chen L, et al. Impact of an educational programme on reproductive health among young migrant female workers in Shenzhen, China: an intervention study. Int J Behav Med 2014;21:710–8. 10.1007/s12529-014-9401-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vu LTH, Nguyen NTK, Tran HTD, et al. mHealth information for migrants: an E-health intervention for internal migrants in Vietnam. Reprod Health 2016;13:55.:55. 10.1186/s12978-016-0172-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He D, Cheng Y-M, Wu S-Z, et al. Promoting contraceptive use more effectively among unmarried male migrants in construction sites in China: a pilot intervention trial. Asia Pac J Public Health 2012;24:806–15. 10.1177/1010539511406106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soltani H, Watson H, Fair F, et al. Improving pregnancy and birth experiences of migrant mothers: A report from ORAMMA and continued local impact. Eur J Midwifery 2020;4:47. 10.18332/ejm/130796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez J, De La Rosa M, Serna CA. Project Salud: efficacy of a community-based HIV prevention intervention for Hispanic migrant workers in South Florida. AIDS Educ Prev [Internet] 2013;25:363–75. 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.5.363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poudel KC, Jimba M, Poudel-Tandukar K, et al. Reaching hard-to-reach migrants by letters: an HIV/AIDS awareness programme in Nepal. Health Place 2007;13:173–8. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silvestre E, Weiner R, Hutchinson P. Behavior change communication and mobile populations: the evaluation of a cross-border HIV/AIDS communication strategy amongst migrants from Swaziland. AIDS Care 2016;28:214–20. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1081668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez J, Silva-Suarez G, Serna CA, et al. The Latino migrant worker HIV prevention program: building a community partnership through a community health worker training program. Fam Community Health 2012;35:139–46. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182465153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hovey JD, Booker V, Seligman LD. Using theatrical presentations as a means of disseminating knowledge of HIV/AIDS risk factors to migrant Farmworkers: an evaluation of the effectiveness of the Infórmate program. J Immigr Minor Health 2007;9:147–56. 10.1007/s10903-006-9023-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stam K, Elkins DB, Dole LR, et al. Letters to loved ones: please don’t bring HIV home. World Health Forum 1997;18:311–8. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/55223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White AL, Min TH, Gross MM, et al. Accelerated training of skilled birth attendants in a marginalized population on the Thai-Myanmar border: A multiple methods program evaluation. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164363. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller LC, Jami-Imam F, Timouri M, et al. Trained traditional birth attendants as educators of refugee mothers. World Health Forum 1995;16:151–6. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/50391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg JS, Bakomeza D. Let’s talk about sex work in humanitarian settings: Piloting a rights-based approach to working with refugee women selling sex in Kampala. Reprod Health Matters 2017;25:95–102. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1405674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Cathain A, Croot L, Sworn K, et al. n.d. Taxonomy of approaches to developing interventions to improve health: A systematic methods overview. Pilot Feasibility Stud;5. 10.1186/s40814-019-0425-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gany F, Thiel de Bocanegra H. Maternal-child immigrant health training: changing knowledge and attitudes to improve health care delivery. Patient Educ Couns 1996;27:23–31. 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00786-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villadsen SF, Mortensen LH, Andersen AMN. Care during pregnancy and childbirth for migrant women: How do we advance? development of intervention studies – the case of the MAMAACT intervention in Denmark. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2016;32:100–12. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Worth H, Denholm N, Bannister J. HIV/AIDS and the African refugee education program in New Zealand. AIDS Educ Prev 2003;15:346–56. 10.1521/aeap.15.5.346.23819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramos RL, Ferreira-Pinto JB, Rusch MLA, et al. Pasa La Voz (spread the word): using women’s social networks for HIV education and testing. Public Health Rep 2010;125:528–33. 10.1177/003335491012500407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martijn C, de Vries NK, Voorham T, et al. The effects of AIDS prevention programs by lay health advisors for migrants in the Netherlands. Patient Educ Couns 2004;53:157–65. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00125-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olshefsky AM, Zive MM, Scolari R, et al. Promoting HIV risk awareness and testing in Latinos living on the U.S.-Mexico border: the Tú no me Conoces social marketing campaign. AIDS Educ Prev 2007;19:422–35. 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.5.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang T, Tian X, Ma F, et al. Community based promotion on VCT acceptance among rural migrants in Shanghai, China. PLoS One 2013;8:e60106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann 2007. doi:101080/01944366908977225 Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01944366908977225 [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connell KA, Hailegebriel TS, Garfinkel D, et al. Meeting the sexual and reproductive health needs of internally displaced persons in Ethiopia’s Somali region: A qualitative process evaluation. Glob Health Sci Pract 2022;10:e2100818. 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGinn T, Allen K. Improving refugees’ reproductive health through literacy in Guinea. Glob Public Health 2006;1:229–48. 10.1080/17441690600680002 Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19153909/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Laughlin KN, Xu A, Greenwald KE, et al. A cohort study to assess a communication intervention to improve linkage to HIV care in Nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda. Glob Public Health 2021;16:1848–55. 10.1080/17441692.2020.1847310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anne-Marie Moulin P. Une Approche Médicosociale pour LES Femmes Migrantes au Maroc-Septembre 2014 rapport de capitalisation sur Le Volet Médicosocial Du Projet « Tamkine-migrants. 2014.

- 53.Association de Lutte Contre le Sida . Rapport D’Activité [Internet]. 2017. Available: https://www.alcs.ma/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/rapport-dactivite%CC%81.compressed.pdf

- 54.Fernández-Balbuena S, Belza MJ, Urdaneta E, et al. Serving the Underserved: an HIV testing program for populations reluctant to attend conventional settings. Int J Public Health 2015;60:121–6. 10.1007/s00038-014-0606-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chemtob D, Rich R, Harel N, et al. Ensuring HIV care to Undocumented migrants in Israel: a public-private partnership case study. Isr J Health Policy Res 2019;8:80.:80. 10.1186/s13584-019-0350-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li N, Li X, Wang X, et al. A cross-site intervention in Chinese rural migrants enhances HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude and behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:4528–43. 10.3390/ijerph110404528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ministry of Foreign Affairs Morocco . Politique Nationale D’Immigration et D’Asile [Internet]. 2017. Available: www.marocainsdumonde.gov.ma

- 58.Abdullahi SA, Smelyanskaya M, John S, et al. Providing TB and HIV outreach services to internally displaced populations in northeast Nigeria: results of a controlled intervention study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003218. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003218 Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32903257/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ministry of Foreign Affairs Morocco . Politique Nationale D’Immigration et D’Asile [Internet]. 2019. Available: www.marocainsdumonde.gov.ma

- 60.World Health Organization . Mapping health systems’ responsiveness to refugee and migrant health needs [Internet]. 2021. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/346682/9789240030640-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- 61.Lin D, Li X, Stanton B, et al. Theory-based HIV-related sexual risk reduction prevention for Chinese female rural-to-urban migrants. AIDS Educ Prev 2010;22:344–55. 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.4.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL. Preventing AIDS. In: The Health Belief Model and HIV Risk Behavior Change. Boston, MA, 1994: 5–24. 10.1007/978-1-4899-1193-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q 1984;11:1–47. 10.1177/109019818401100101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Icek A. Attitudes, personality and behavior. Open University Press, 1988: 175. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richard R, van der Pligt J, de Vries N. Anticipated affective reactions and prevention of AIDS. Br J Soc Psychol 1995;34:9–21. 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaalma H, Kok G, Peters L. Determinants of consistent condom use by adolescents: the impact of experience of sexual intercourse. Health Educ Res 1993;8:255–69. 10.1093/her/8.2.255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude Change1. n.d. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Michie S, West R, Campbell R, et al. ABC of behaviour change theories. Policy Makers and Practitioners 402 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 1992;47:1102–14. 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ministry of Foreign Affairs Morocco . Politique Nationale D’Immigration et D’Asile [Internet]. 2018. Available: www.marocainsdumonde.gov.ma

- 71.Ministry of Foreign Affairs Morocco . Politique Nationale D’Immigration et D’Asile [Internet]. 2020. Available: www.marocainsdumonde.gov.ma

- 72.Siddiqui M, Kataria I, Watson K, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on peer education programmes for promoting the sexual and reproductive health of young people in India. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2020;28:1741494. 10.1080/26410397.2020.1741494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kenny A, Hyett N, Sawtell J, et al. Community participation in rural health: a Scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:64. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, et al. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:129. 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.George AS, Mehra V, Scott K, et al. Community participation in health systems research: A systematic review assessing the state of research, the nature of interventions involved and the features of engagement with communities. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141091. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Booth A, Carroll C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis for studies of improvement in Healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:700–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003642 Available: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/24/11/700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Johnsen H, Christensen U, Juhl M, et al. Organisational barriers to implementing the MAMAACT intervention to improve maternity care for non-Western immigrant women: A qualitative evaluation. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;111:103742. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnsen H, Christensen U, Juhl M, et al. Contextual factors influencing the MAMAACT intervention: A qualitative study of non-Western immigrant women’s response to potential pregnancy complications in everyday life. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1040. 10.3390/ijerph17031040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Redden K, Safarian J, Schoenborn C, et al. Interventions to support International migrant women’s reproductive health in Western-receiving countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Equity 2021;5:356–72. 10.1089/heq.2020.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. J Public Health Dent 2011;71 Suppl 1:S20–33. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaljee LM, Genberg B, Riel R, et al. Effectiveness of a theory-based risk reduction HIV prevention program for rural Vietnamese adolescents. AIDS Educ Prev 2005;17:185–99. 10.1521/aeap.17.4.185.66534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Breuer E, Lee L, De Silva M, et al. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: A systematic review. Implement Sci 2016;11:63. 10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williams B, Hummelbrunner R. Systems concepts in action. In: Systems concepts in action: a practitioner’s toolkit. 2011: 327. 10.1515/9780804776554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kuo F-Y, Young M-L. A study of the intention–action gap in knowledge sharing practices. J Am Soc Inf Sci 2008;59:1224–37. 10.1002/asi.20816 Available: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/asi.v59:8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;289:454–65. 10.1001/jama.289.4.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, et al. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:1167–70. 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sismondo S. How pharmaceutical industry funding affects trial outcomes: causal structures and responses. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1909–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Farrington DP, Ttofi MM. Measuring conflict of interest in prevention and intervention research. Antisocial Behavior and Crime: Contributions of Developmental and Evaluation Research to Prevention and Intervention 2012:165–80. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE, 1997: 235. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Theory and practice Fourth Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2015: 832. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lahuerta M, Zerbe A, Baggaley R, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and adherence with short-term HIV Preexposure prophylaxis in female sexual partners of migrant miners in Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:343–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huang Y, Merkatz R, Zhu H, et al. The free perinatal/postpartum contraceptive services project for migrant women in Shanghai: effects on the incidence of unintended pregnancy. Contraception 2014;89:521–7. 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alam MS, Khan SI, Reza M, et al. Point of care HIV testing with oral fluid among Returnee migrants in a rural area of Bangladesh. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11:S52–8. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Johnsen H, Ghavami Kivi N, Morrison CH, et al. Addressing ethnic disparity in Antenatal care: A qualitative evaluation of Midwives’ experiences with the MAMAACT intervention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:118. 10.1186/s12884-020-2807-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Johnsen H, Christensen U, Juhl M, et al. Implementing the MAMAACT intervention in Danish Antenatal care: a qualitative study of non-Western immigrant women’s and Midwives’ attitudes and experiences. Midwifery 2021;95:S0266-6138(21)00014-0. 10.1016/j.midw.2021.102935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Damsted Rasmussen T, Johnsen H, Smith Jervelund S, et al. Implementation, mechanisms and context of the MAMAACT intervention to reduce ethnic and social disparity in Stillbirth and infant health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:8583. 10.3390/ijerph18168583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.UNHCR . Saving maternal and newborn lives in refugee situations - evaluation summary [Internet]. 2021. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/62960e0b4

- 98.Ajzen I. The theory of Plannedbehavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, eds. Preventing AIDS. AIDS Prevention and Mental Health. Springer, Boston, MA, 10.1007/978-1-4899-1193-3_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2023-011981supp001.pdf (354.6KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-011981supp002.pdf (562.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study.