Abstract

A man in his early 70s with a 4-year history of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was admitted to our hospital with diplopia and achromatopsia. Neurological examination revealed visual impairment, ocular motility disorder and diplopia on looking to the left. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid investigations showed no significant findings. MRI revealed diffusely thickened dura mater and contrast-enhanced structures in the left apical orbit, consistent with hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP). We performed an open dural biopsy to distinguish the diagnosis from lymphoma. The pathological diagnosis was idiopathic HP, and DLBCL recurrence was ruled out. Following methylprednisolone pulse and oral prednisolone therapy, his neurological abnormalities gradually receded. Open dural biopsy played an important role not only in diagnosing idiopathic HP but also in relieving the pressure on the optic nerve.

Keywords: Cranial nerves, Headache (including migraines)

Background

Hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP) is a rare disorder affecting approximately 1:100 000 population.1 HP is characterised by local or diffuse thickening of the dura mater2 and can be classified as idiopathic HP (IHP) or secondary HP (SHP).1 Since SHP requires treatment of the primary disease, a definitive ruling out of SHP is indispensable to determine the treatment plan for patients with suspected IHP. Here we report a case of IHP in which the patient had a medical history of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and an open dural biopsy not only played an indispensable role in confirming the diagnosis of IHP but also may have relieved the patient’s symptoms.

Case presentation

A man in his early 70s was admitted to our hospital with diplopia on looking to the left and left-sided achromatopsia. He had a history of DLBCL 4 years ago. The tumour was located in the right submandibular, left external iliac and left inguinal lymph nodes. The absence of central nervous system (CNS) involvement was carefully confirmed, and he never presented any neurological deficits. He had undergone chemotherapy and radiotherapy for lymph node lesions and an intrathecal infusion of methotrexate (MTX), cytarabine and prednisolone (PSL) as prophylaxis to prevent recurrence of the DLBCL in the CNS. He had no recurrence until his current visit to our hospital. One month before admission, he had a mild intermittent frontal headache and daily heaviness of the head that worsened slightly in the evening. Eleven days prior to admission, he developed diplopia. Six days before admission, he presented with left-sided red and blue achromatopsia, which gradually worsened, and when he was admitted, he had lost colour vision in the left eye. His medication included only small doses of antihypertensive drugs.

Investigations

Figure 1 summarises the time course of the clinical findings. Neurological examination performed on admission revealed left visual acuity of light perception, vision loss in the left lower visual field (figure 2a), limited extraocular movements of left abduction and left depression (figure 3a), diplopia on looking to the left, loss of colour vision in the left eye and left relative afferent pupillar deficit (RAPD). His vital signs were normal, and physical examination revealed no enlarged superficial lymph nodes. The laboratory work-up revealed elevated inflammatory markers (C reactive protein, 5.86 mg/dL; leucocyte, 9.4×103/µL), absence of autoantibodies and infectious disease markers, and normal levels of liver and kidney function, the soluble interleukin-2 receptor, thyroid-stimulating hormone, IgG4 and free T4 (online supplemental material 1). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) test results revealed normal pressure and no pleocytosis, CSF culture showed no significant growth, and CSF flow cytometry showed no lymphoma cells. T1-weighted image of the contrast-enhanced MRI scan revealed diffusely thickened dura mater (figure 4a) and contrast-enhanced structures in the left apical orbit from the optic canal to the inferior rectus muscle (figure 5a). Systemic CT scan revealed no abnormalities, including enlarged lymph nodes.

Figure 1.

Clinical time course. DEX, dexamethasone; MTX, methotrexate; mPSL, methylprednisolone; PSL, prednisolone. Figure created by author YY.

Figure 2.

Visual field of the left eye. The images show the visual field of the left eye measured by a Goldmann visual field meter. (A) On day 7, there was a visual defect in the lower half of the visual field. (B and C) On days 22 and 64, after craniotomy and steroid pulse therapy, the visual field recovered considerably, although the central visual field defect remained.

Figure 3.

Extraocular movement. Clockwise from upper left: frontal, depression, left depression and left abduction ocular positions. (A) The patient showed limited extraocular movements of left abduction and left depression on day 16. (B) The oculomotor disturbance had decreased on day 29.

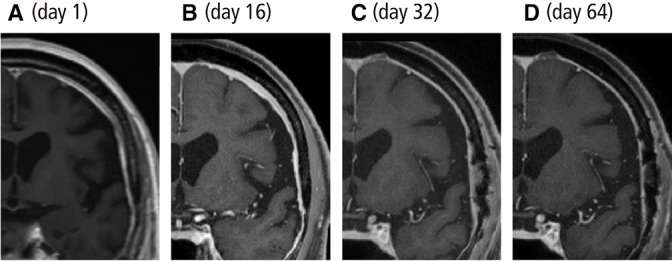

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced MRI T1-weighted images of the brain. (A and B) On days 1 and 16, the dura mater was diffusely thickened. (C and D) The dura mater thickness improved markedly on days 32 and 64 after methylprednisolone pulse therapy and prednisolone administration.

Figure 5.

Open dural biopsy. (A) The contrast-enhanced MRI T1-weighted horizontal image of the brain. The arrow indicates the biopsy site. (B and C) B shows a photo of the open dural biopsy surgical field, and C is a diagram over the photo marking the arteries and gauze in the thickened dura mater. In the open dural biopsy performed on day 18, the Sylvian fissure was divided, the sphenoid bone was shaved, and a portion of the dura mater was removed to expose the left optic nerve. The internal carotid artery runs slightly to the left from the centre of the image, and the optic canal runs to its right (a part of the optic canal is hidden by gauze for haemostasis). The ophthalmic artery can be seen between the internal carotid artery and the optic nerve. The thickened dura mater covering these areas (dotted line in C) was excised for the pathological diagnosis.

bcr-2023-254847supp001.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)

Differential diagnosis

Based on the aforementioned findings, we strongly suspected HP; however, a relapse of DLBCL in the CNS was not conclusively ruled out. We consulted the possibility of DLBCL with haematologists and introduced intrathecal MTX (15 mg) and cytarabine (40 mg) on the 7th day of hospitalisation. After the intrathecal MTX and cytarabine injection, the patient’s headache subsided. However, the patient continued to exhibit the neurological abnormalities, and the dural thickening did not show any improvement on the MRI conducted on the 16th day (figures 1 and 4b). As a result, we became confident that the HP was not related to a DLBCL relapse, which should respond to MTX or cytarabine therapy. We considered the disappearance of headache after intrathecal injection could be explained as a natural course unrelated to injection, as his headache was intermittent on its onset. Subsequently, an open dural biopsy was performed on day 18 to confirm the diagnosis, which revealed that the lesion around the left optic nerve was integrated with the thickened dura mater (figure 5). There were a few small T cell dominant lymphocytic infiltrates in the fibrous tissue of the thickened dura mater. However, there were no large lymphoplasmacytic infiltrations, which are characteristic of DLBCL. Pathological findings were consistent with HP, and CNS recurrence of DLBCL was ruled out. Among the possible causes of HP, infectious diseases were ruled out based on the blood and CSF findings. Systemic autoimmune and vasculitic diseases were also ruled out based on the blood and pathological findings. Meningiomas were excluded based on the imaging findings. Based on the imaging and pathological findings, solid tumours and lymphoma were ruled out. Therefore, we concluded that the diagnosis was IHP.

Treatment

We administered methylprednisolone 1000 mg/day on days 18–20 and initiated oral PSL (70 mg/day) (1 mg/kg/day) on day 30, which was gradually tapered. From day 20, dexamethasone was administered in decreasing doses starting at 8 mg as a prophylactic against nerve injury after biopsy.

Outcome and follow-up

Figures 2–4 show the changes in the patient’s left visual field, extraocular movements and T1-weighted MR images, respectively. In terms of colour vision in the left visual field, the patient could perceive yellow colour in the upper half of the field on day 20 and blue on day 31. The perception of yellow and blue in the lower half gradually returned, and the colours yellow, blue and red became visible by day 35 in almost the entire visual field. An MRI scan on day 32 showed improved dural thickening. On day 36, the left-sided visual acuity was 0.08 (20/250), and the left visual field had recovered, except for the central visual field defect. The left oculomotor disturbance had decreased, while the left-sided RAPD persisted. The patient was discharged on day 70 when the PSL was tapered to 30 mg. He is being followed up as an outpatient, his PSL is being continuously tapered, and his neurological abnormalities have gradually receded.

Discussion

HP is a rare disease affecting approximately 1:100 000 population. The majority of HP is SHP associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-related diseases (34.0%), IgG4-related diseases (8.8%), intracranial hypotension, infections, meningiomas or malignant tumours, and IHP accounts for 44.0% of HP.1

To the best of our knowledge, only 99 cases of cranial IHP have been reported in the literature. A search on PubMed (http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) on 13 March 2021 for “IHP AND english(la) AND case reports(pt)” found 149 articles. Of these, 32 papers that did not report on IHP, 23 papers for which the full text was not available online, and 2 papers reporting on non-human organisms were excluded. A total of 132 cases were reported in these articles, of which 99 (75.0%) were cranial IHP, and the rest were spinal IHP. The 99 cases are summarised in table 1, and this is the first report of cranial IHP in a patient with a history of lymphoma. CNS recurrence of the lymphoma occurs in 2%–10% of patients with DLBCL,3–5 and the median recurrence-free survival from the diagnosis of DLBCL to CNS recurrence is 5–20 months.4 6 7 It is known that CNS lesions of malignant lymphoma sometimes mimic the imaging findings of HP.8 The median survival following a CNS relapse of DLBCL is 2–5 months.7

Table 1.

Published cases of cranial idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis

| Author | Age/sex | Cranial nerve palsy | Lesion in MRI | Biopsy | Medication | Outcome | ||

| Localised | Diffused | Improved | Recurred | |||||

| Yao et al 11 | 40/M | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Surgery | Yes | No |

| Huang et al 12 | 60/F | IX, X and XII | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid | Yes | No |

| Huang et al 13 | 52/F | None | No | Yes | No | Cyclophosphamide (400 mg/m2), daily low-dose steroids 2 years | Yes | No |

| Rudnik et al 14 | 63/F | VI, IX and X | No | Yes | Yes | DEX 12 mg/day 7 days, DEX 6 mg/day PO | Yes | No |

| D'Andrea et al 15 | NA/F | III, IV, IX, X and XII | Yes | Yes | Yes | Steroid | Yes | No |

| 70/F | NA | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | |

| Rizzo et al 16 | 14/M | IV and VI | No | Yes | No | Steroid pulse, PSL 60 mg/day PO | Yes | No |

| Russo et al 17 | 62/M | VI | No | No | No | mPSL 50 mg/day and enoxaparin 200 IU/kg/day, mPSL 25 mg/day and azathioprine (AZA) 125 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Hsieh et al 18 | 16/F | XII | No | Yes | No | Steroid, rituximab | Yes | No |

| Bosman et al 19 | 62/M | IV, V and XII | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse 3 days, MTX 12.5 mg/week | Yes | No |

| Hassan et al 20 | 24/F | III, IV, V and VI | Yes | Yes | Yes | PSL 60 mg/day and propranolol 80 mg/day and nortriptyline 50 mg/day, AZA 100 mg/day | Yes | Yes |

| 56/F | NA | No | Yes | Yes | PSL and AZA | Yes | No | |

| 24/M | VI and VII | Yes | Yes | Yes | PSL and AZA | Yes | No | |

| Riku et al 21 | 75/M | None | No | Yes | Yes | mPSL 250 mg/day | No | |

| 88/F | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | No | ||

| 37/M | VI | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse | Yes | No | |

| 59/M | III and VI | No | Yes | Yes | PSL | Yes | Yes | |

| 58/F | II | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse | Yes | Yes | |

| 63/M | II, III, IV, V and VI | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse | Yes | Yes | |

| 63/M | III, V, VIII, IX, X and XI | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL and AZA, and V-P shunt | Yes | Yes | |

| 71/M | None | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse (500 mg/day) | Yes | Yes | |

| 65/F | II, III, VI and VIII | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse | Yes | Yes | |

| 64/F | II and V | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse | Yes | Yes | |

| 72/M | II | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse | Yes | No | |

| 69/M | VI and XII | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse (500 mg/day) | Yes | No | |

| 64/F | None | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse (500 mg/day) | NA | NA | |

| Suárez et al 22 | 43/M | III | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse and cyclophosphamide 1000 mg/day | No | |

| Uchida et al 23 | 51/F | V | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse 3 days, low-dose MTX | Yes | Yes |

| Reggio et al 24 | 70/F | None | No | Yes | No | Removal of 30 mL of CSF | Yes | No |

| Wu et al 25 | 41/M | NA | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 60 mg/day + AZA 50–150 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Sylaja et al 26 | 52/F | II, III, VI, VII, IX and X | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 40 mg/day | Yes | No |

| 38/F | None | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 40 mg/day | Yes | Yes | |

| 30/M | (II and VI) | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL 40 mg/day | Yes | No | |

| 38/F | VI, IX, X and XII | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No | |

| Deprez et al 27 | 44/F | (VIII) | Yes | No | Yes | AZA 100 mg/day, surgery, mPSL 8 mg/day and cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 | Yes | No |

| Hatano et al 28 | 56 /M | III, IV and VI | No | Yes | No | PSL | Yes | No |

| 69/M | VII, VIII, IX and X | No | Yes | Yes | PSL | Yes | No | |

| 62/M | VII, VIII, IX and X | No | Yes | Yes | PSL | Yes | No | |

| 69/F | III | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL 10 mg/day | Yes | No | |

| 57/F | VI | Yes | Yes | Yes | PSL 30 mg/day | Yes | No | |

| 58/M | II, III, IV, V and VI | Yes | Yes | Yes | Anti-tubercular treatment | Yes | No | |

| Yamada et al 29 | 70/M | IX and X | No | Yes | Yes | PSL pulse 3 day, PSL 45 mg/day PO | Yes | No |

| Kanemoto et al 30 | 52/M | None | Yes | No | No | PSL 30 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Botella et al 31 | 55/F | NA | No | Yes | No | DEX 24 mg/day, laminectomy | Yes | Yes |

| Hamada et al 32 | 64/M | None | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, craniotomy, PSL 80 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Lee et al 33 | 23/F | None | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 20 mg/day | Yes | Yes |

| Kleiter et al 34 | 28/M | (II and VIII) | Yes | No | No | Cytarabine via Ommaya reservoir and triamcinolone-acetonide PO | Yes | No |

| Tsuchida et al 35 | 3/F | None | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, cyclophosphamide and cytarabine via Ommaya reservoir | No | |

| Loy et al 36 | 34/M | III and VI | No | Yes | Yes | PSL, antitubercular treatment | Yes | No |

| Wasilewski et al 37 | 39/F | (II and VI) | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid, MTX | NA | NA |

| Han et al 38 | 59/M | None | Yes | No | Yes | Surgery | Yes | No |

| Mamelak et al 39 | 67/F | XII | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 40 mg/day | No | |

| 50/F | (V and XII) | Yes | No | Yes | DEX 16 mg/day, surgery, surgery, PSL 20 mg/day, AZA | Yes | No | |

| 75/M | III, IV, VI and VII | NA | NA | Yes | Surgery | Yes | No | |

| Bhatia et al 40 | 38/M | (II and VI) | Yes | Yes | No | PSL, warfarin | Yes | Yes |

| 23/M | II | No | Yes | Yes | DEX 1 week, PSL 1 mg/kg/day 6–8 weeks, warfarin, acetazolamide | Yes | No | |

| Auboire et al 41 | 56/M | NA | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid | Yes | Yes |

| Phanthumchinda et al 42 | 23/M | None | NA | NA | Yes | PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No |

| 30/F | None | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No | |

| 42/M | IV, V and VIII | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | Yes | |

| Lok et al 43 | 28/F | NA | Yes | No | Yes | DEX | Yes | No |

| Fan et al 44 | 33/M | NA | No | No | Yes | Steroid | Yes | No |

| van Toorn et al 45 | 10/M | IV, V and VI | No | Yes | No | Steroid pulse, PSL 2 mg/kg/day | Yes | No |

| Hosler et al 46 | 28/F | NA | Yes | No | Yes | MTX 22.5 mg/week, PSL, AZA 125 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Kon et al 47 | 50/F | None | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL 1 mg/kg/day | Yes | No |

| Brand et al 48 | 13/M | VI | Yes | No | Yes | No medication | Yes | No |

| Im et al 49 | 66/M | VIII | No | Yes | Yes | V-P shunt, steroid, MTX 12.5 mg/week | Yes | Yes |

| Nakazaki et al 50 | 51/F | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Surgery, PSL 20 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Oiwa et al 51 | 44/M | None | No | Yes | No | Anticonvulsants, phenytoin 300 mg/day, phenobarbital 90 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Keshavaraj et al 52 | 40/F | (II) | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid | Yes | No |

| Christakis et al 53 | 48/F | (VIII and XII) | No | Yes | Yes | mPSL, PSL | No | |

| Aburahma et al 54 | 3 /M | II | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL 2 mg/kg/day | Yes | Yes |

| Lu et al 55 | 43/M | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse, PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Navalpotro-Gómez et al 56 | 40/M | None | Yes | No | Yes | PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No |

| 82/F | NA | Yes | No | No | Steroid pulse, PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No | |

| Hiraka et al 57 | 57/M | II | No | Yes | No | PSL 1 mg/kg/day | Yes | No |

| Miyake et al 58 | 53/M | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse three times, PSL 20 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Yaylali et al 59 | 24/M | (II and VI) | Yes | No | Yes | Steroid pulse, steroid and AZA | Yes | Yes |

| Nishioka et al 60 | 56/F | V and VI | Yes | No | Yes | Betamethasone 16 mg/day | Yes | Yes |

| Karakasis et al 61 | 47/F | VI | No | Yes | No | DEX | Yes | Yes |

| Tan et al 62 | 39/F | NA | Yes | No | No | Steroid | Yes | Yes |

| Ito et al 63 | 63/F | VI | No | Yes | No | Steroid | Yes | Yes |

| Ruiz-Sandoval et al 64 | 63/F | II, IV, V, VI, VII and VIII | No | Yes | No | MTX 12.5 mg/week | Yes | No |

| Goyal et al 65 | 28/M | I, II, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and XII | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid | No | |

| 62/F | VI, IX, X and XII | No | Yes | Yes | Steroid | Yes | No | |

| 34/F | (II, V and VII) | No | Yes | No | NA | NA | NA | |

| 19/F | NA | No | Yes | No | NA | NA | NA | |

| Park et al 66 | 37/M | III and VI | No | Yes | Yes | DEX 20 mg/day, PSL 20 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Shankar Iyer et al 67 | 28/F | VI (VII) | No | Yes | Yes | PSL 1 mg/kg/day and AZA | Yes | No |

| George et al 68 | 32/F | VI | Yes | No | Yes | PSL 50 mg/day | Yes | Yes |

| Mathew et al 69 | 54/F | (II) V | Yes | No | No | PSL 30 mg/day, MTX | Yes | No |

| Yamamoto et al 70 | 48/M | NA | No | Yes | No | Steroid pulse, PSL 60 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Khalil et al 71 | 82/M | (VI) | No | Yes | No | PSL 75 mg/day | Yes | No |

| Nishioka et al 72 | 50/F | III | No | Yes | No | mPSL | Yes | Yes |

| Driscoll et al 73 | 32/F | NA | No | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA |

| Bovo et al 74 | 68/M | VI | No | Yes | No | PSL 1 mg/kg/day | Yes | No |

| Kazem et al 75 | 42/M | (II) | Yes | No | Yes | Surgery, steroid | Yes | Yes |

| Weir et al 76 | 56/F | (II) | Yes | No | Yes | DEX, PSL | Yes | No |

| Wouda et al 77 | 37/M | None | Yes | Yes | Yes | Surgery | NA | NA |

DEX, dexamethasone; mPSL, methylprednisolone; MTX, methotrexate; PSL, prednisolone.

In the current case, the patient’s CNS-International Prognostic Index score9 was four points (age, serum lactate dehydrogenase, stage and extranodal lesions), indicating a high-pretest probability of CNS relapse. Therefore, an intrathecal injection was administered as prophylaxis; however, the 4-year CNS recurrence rate in the high-risk group is as high as 1.6% despite prophylactic injection.10 In this case, the open dural biopsy played a decisive role in ruling out SHP, especially CNS recurrence of DLBCL, and in confirming the diagnosis of IHP, which was the rationale for choosing corticosteroid therapy.

Furthermore, removing the thickened dura mater and sphenoid bone around the left optic nerve canal for biopsy might have relieved the pressure on the optic nerve, and the biopsy itself might have therapeutically contributed to the recovery of vision. When diagnosing IHP, it is important to consider the invasiveness and significance of dural biopsy and the indications.

Learning points.

We present the first case of idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis (IHP) in which the patient had a history of diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Central nervous system (CNS) relapse of lymphoma is known to have an extremely poor prognosis, and an open dural biopsy played an indispensable role in excluding the possibility of CNS relapse of lymphoma and confirming the diagnosis of IHP in the current case.

When diagnosing IHP, it is important to consider the invasiveness and significance of dural biopsy and the indications.

Early treatment using immunosuppression drugs is paramount in treating hypertrophic pachymeningitis.

Footnotes

Contributors: JKK, TH and IS: writing—review and editing. TH: investigation. IS: supervision. YY: conceptualisation, data curation and writing—original draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1. Yonekawa T, Murai H, Utsuki S, et al. A nationwide survey of hypertrophic pachymeningitis in Japan. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2014;85:732–9. 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kupersmith MJ, Martin V, Heller G, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Neurology 2004;62:686–94. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113748.53023.b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hollender A, Kvaloy S, Nome O, et al. Central nervous system involvement following diagnosis Ofnon-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a risk model. Ann Oncol 2002;13:1099–107. 10.1093/annonc/mdf175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shimazu Y, Notohara K, Ueda Y. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with central nervous system relapse: prognosis and risk factors according to retrospective analysis from a single-center experience. Int J Hematol 2009;89:577–83. 10.1007/s12185-009-0289-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Villa D, Connors JM, Shenkier TN, et al. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the impact of the addition of Rituximab to CHOP chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1046–52. 10.1093/annonc/mdp432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernstein SH, Unger JM, Leblanc M, et al. Natural history of CNS relapse in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a 20-year follow-up analysis of SWOG 8516 -- the Southwest oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:114–9. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boehme V, Zeynalova S, Kloess M, et al. Incidence and risk factors of central nervous system recurrence in aggressive lymphoma--a survey of 1693 patients treated in protocols of the German high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma study group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol 2007;18:149–57.:S0923-7534(19)37562-3. 10.1093/annonc/mdl327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsu H-T, Hsu S-S, Chien C-C, et al. Teaching Neuroimages: idiopathic hypertrophic spinal Pachymeningitis mimicking epidural lymphoma. Neurology 2015;84:e67–8. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M, et al. CNS International Prognostic index: A risk model for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3150–6. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.6520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zaremba LS, Smoleński WH. Optimal portfolio choice under a liability constraint. Ann Oper Res 2000;97:131–41. 10.1023/A:1018996712442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yao A, Jia L, Wang B, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis mimicking meningioma with occlusion of superior sagittal sinus. World Neurosurg 2019;127:534–7.:S1878-8750(19)30997-0. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang Y, Chen J, Gui L. A case of idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis presenting with chronic headache and multiple cranial nerve Palsies: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7549.: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang K, Xu Q, Ma Y, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis secondary to idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis. World Neurosurg 2017;106:1052.S1878-8750(17)31101-4. 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rudnik A, Larysz D, Gamrot J, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis - case report and literature review. Folia Neuropathol 2007;45:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. D’Andrea G, Trillò G, Celli P, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertrophic pachymeningitis: two case reports and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 2004;27:199–204. 10.1007/s10143-004-0321-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rizzo E, Ritchie AE, Shivamurthy V, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis: does earlier treatment improve outcome? Children 2020;8:11. 10.3390/children8010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Russo A, Silvestro M, Cirillo M, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis mimicking hemicrania continua: an unusual clinical case. Cephalalgia 2018;38:804–7. 10.1177/0333102417708773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsieh DT, Faux BM, Lotze TE. Headache and Hypoglossal nerve palsy in a child with idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Headache 2019;59:1390–1. 10.1111/head.13598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bosman T, Simonin C, Launay D, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis treated by oral methotrexate: a case report and review of literature. Rheumatol Int 2008;28:713–8. 10.1007/s00296-007-0504-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hassan KM, Deb P, Bhatoe HS. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis: three biopsy-proven cases including one case with abdominal Pseudotumor and review of the literature. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2011;14:189–93. 10.4103/0972-2327.85891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Riku S, Kato S. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Neuropathology 2003;23:335–44. 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2003.00520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suárez AR, Capote AC, Barrientos YF, et al. Ocular involvement in idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis associated with eosinophilic Angiocentric fibrosis: a case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2018;81:250–3. 10.5935/0004-2749.20180050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uchida H, Ogawa Y, Tominaga T. Marked effectiveness of low-dose oral methotrexate for steroid-resistant idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis: case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2018;168:30–3. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reggio E, Giliberto C, Sortino G, et al. A case of headache and idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis drastically improved after CSF tapping. Headache 2016;56:176–7. 10.1111/head.12735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu C-S, Wang H-P, Sung S-F. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis with anticardiolipin antibody: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sylaja PN, Cherian PJ, Das CK, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis. Neurol India 2002;50:53–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deprez M, Born J, Hauwaert C, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis mimicking multiple Meningiomas: case report and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol 1997;94:385–9. 10.1007/s004010050723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hatano N, Behari S, Nagatani T, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis: Clinicoradiological spectrum and therapeutic options. Neurosurgery 1999;45:1336–42. 10.1097/00006123-199912000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yamada SM, Aoki M, Nakane M, et al. A case of subarachnoid hemorrhage with pituitary Apoplexy caused by idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Neurol Sci 2011;32:455–9. 10.1007/s10072-010-0343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kanemoto M, Ota Y, Karahashi T, et al. A case of idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis manifested only by positive rheumatoid factor and abnormal findings of the anterior Falx. Rheumatol Int 2005;25:230–3. 10.1007/s00296-004-0482-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Botella C, Orozco M, Navarro J, et al. Idiopathic chronic hypertrophic craniocervical pachymeningitis. Neurosurgery 1994;35:1144–9. 10.1227/00006123-199412000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hamada J, Yoshinaga Y, Korogi Y, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis associated with a dural Arteriovenous Fistula involving the straight sinus: case report. Neurosurgery 2000;47:1230–3. 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee YC, Chueng YC, Hsu SW, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis: case report with 7 years of imaging follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:119–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kleiter I. Intraventricular cytarabine in a case of idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2004;75:1346–8. 10.1136/jnnp.2003.024653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsuchida K, Fukumura S, Yamamoto A, et al. Rapidly progressive fatal idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis with brainstem involvement in a child. Childs Nerv Syst 2018;34:1795–8. 10.1007/s00381-018-3819-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loy ST, Tan CWT. Granulomatous meningitis. Singapore Med J 2009;50:e371–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wasilewski A, Samkoff L. Teaching neuro images: idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Neurology 2016;87:e270–1. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Han M-S, Moon K-S, Lee K-H, et al. Intracranial inflammatory Pseudotumor associated with idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis mimicking malignant tumor or high-grade meningioma. World Neurosurg 2020;134:372–6.:S1878-8750(19)32810-4. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.10.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mamelak AN, Kelly WM, Davis RL, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis. Journal of Neurosurgery 1993;79:270–6. 10.3171/jns.1993.79.2.0270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bhatia R, Tripathi M, Srivastava A, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis and dural sinus occlusion: two patients with long-term follow up. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:937–42. 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Auboire L, Boutemy J, Constans JM, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis presenting with occipital neuralgia. Afr Health Sci 2015;15:302. 10.4314/ahs.v15i1.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phanthumchinda K, Sinsawaiwong S, Hemachudha T, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis: an unusual cause of subacute and chronic headache. Headache 1997;37:249–52. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3704249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lok JYC, Yip NKF, Chong KKL, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis mimicking Prolactinoma with recurrent vision loss. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:360–2. 10.12809/hkmj144295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fan Y, Liao S, Yu J, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis manifested by transient ischemic attack. Med Sci Monit 2009;15:CS178–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van Toorn R, Esser M, Smit D, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis causing progressive polyneuropathies in a child. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2008;12:144–7. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hosler MR, Turbin RE, Cho E-S, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis mimicking Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma. J Neuroophthalmol 2007;27:95–8. 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318064c53a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kon T, Nishijima H, Haga R, et al. Hypertrophic pachymeningitis accompanying neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a case report. J Neuroimmunol 2015;287:27–8. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brand B, Somers D, Wittenberg B, et al. Diplopia with dural Fibrotic thickening. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2018;26:83–7.:S1071-9091(17)30040-2. 10.1016/j.spen.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Im S-H, Cho K-T, Seo HS, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis presenting with headache. Headache 2008;48:1232–5. Available http://blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/hed.2008.48.issue-8 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nakazaki H, Tanaka T, Isoshima A, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis with Perifocal brain edema. Case report. Neurol Med Chir 2000;40:239–43. 10.2176/nmc.40.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Oiwa Y, Hyotani G, Kamei I, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis associated with total occlusion of the dural sinuses--case report. Neurol Med Chir 2004;44:650–4. 10.2176/nmc.44.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Keshavaraj A, Gamage R, Jayaweera G, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis presenting with a superficial soft tissue mass. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2012;3:193–5. 10.4103/0976-3147.98240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Christakis PG, Machado DG, Fattahi P. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis mimicking neurosarcoidosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012;114:176–8. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aburahma SK, Anabtawi AGM, Al Rimawi HS, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis in a child with hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurol 2009;40:457–60. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu Y-R, et al. Focal idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningoencephalitis. J. Formos. Med. Assoc 2008;107:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Navalpotro-Gómez I, Vivanco-Hidalgo RM, Cuadrado-Godia E, et al. Focal status epilepticus as a manifestation of idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2016;367:232–6. 10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hiraka T, Koyama S, Kurokawa K, et al. Reversible distension of the subarachnoid space around the optic nerves in a case of idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Magn Reson Med Sci 2012;11:141–4. 10.2463/mrms.11.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Miyake K, Okada M, Hatakeyama T, et al. Usefulness of L-[Methyl-<sup>11</sup>C]Methionine Positron Emission Tomography in the Treatment of Idiopathic Hypertrophic Cranial Pachymeningitis. Neurol Med Chir 2012;52:765–9. 10.2176/nmc.52.765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yaylali SA, Akcakaya AA, Işik N, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis associated with intermediate uveitis. Neuroophthalmology 2011;35:88–91. 10.3109/01658107.2011.559683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nishioka H, Ito H, Haraoka J, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis of the cavernous sinus mimicking lymphocytic Hypophysitis. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:377–82. 10.2176/nmc.38.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Karakasis C, Deretzi G, Rudolf J, et al. Long-term lack of progression after initial treatment of idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:321–3. 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tan K, Lim SA, Thomas A, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis causing seizures. Eur J Neurol 2008;15:e12–3. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ito F, Kondo N, Fukushima S, et al. Catatonia induced by idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:447. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Bernard-Medina G, Ramos-Gómez EJ, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial Pachymeningitis successfully treated with weekly subcutaneous methotrexate. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:1011–4. 10.1007/s00701-006-0775-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Goyal M, Malik A, Mishra NK, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis: spectrum of the disease. Neuroradiology 1997;39:619–23. 10.1007/s002340050479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Park I-S, Kim H, Chung EY, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis misdiagnosed as acute Subtentorial hematoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010;48:181. 10.3340/jkns.2010.48.2.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shankar Iyer R, Padmanaban S, Ramachandran M. Unilateral optic disc swelling associated with idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis: a rare cause for a rare clinical finding. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr2017219559. 10.1136/bcr-2017-219559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. George MM, Goswamy J, Solanki K, et al. Infiltrative mass of the skull base and nasopharynx: a diagnostic conundrum. Ann Med Surg 2015;4:103–6. 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mathew RG, Hogarth KM, Coombes A. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis presenting as acute painless visual loss. Int Ophthalmol 2012;32:195–7. 10.1007/s10792-012-9536-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yamamoto T, Goto K, Suzuki A, et al. Long-Term improvement of idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis by lymphocytapheresis. Ther Apher 2000;4:313–6. 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2000.004004313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Khalil M, Ebner F, Fazekas F, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis: a rare but treatable cause of headache and facial pain. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2013;84:354–5. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nishioka H, Ito H, Haraoka J, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis with accumulation of thallium-201 on single-photon emission CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:450–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Driscoll S, Murchison AP, Bilyk JR. See no evil, hear no evil…. Surv Ophthalmol 2014;59:251–9. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bovo R, Berto A, Palma S, et al. Symmetric sensorineural progressive hearing loss from chronic idiopathic pachymeningitis. Int J Audiol 2007;46:107–10. 10.1080/14992020600969744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kazem IA, Robinette NL, Roosen N. Best cases from the AFIP: idiopathic tumefactive hypertrophic pachymeningitis. RadioGraphics 2005;25:1075–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Weir NU, Collie D, McIlwaine GG, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic chronic Pachymeningitis presenting with acute visual loss. Eye (Lond) 1999;13 (Pt 3a):384–7. 10.1038/eye.1999.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wouda EJ, Vanneste JA. Aspecific headache during 13 years as the only symptom of idiopathic hypertrophic Pachymeningitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:408–9. 10.1136/jnnp.64.3.408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bcr-2023-254847supp001.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)