Abstract

Objective

To examine current knowledge about suicide bereavement and postvention interventions for university staff and students.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources and eligibility

We conducted systematic searches in 12 electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Africa-Wide Information, PsycARTICLES, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, Academic Search Premier, SocINDEX through the EBSCOHOST platform; Cochrane Library, Web of Science, SCOPUS), hand searched lists of references of included articles and consulted with library experts during September 2021 and June 2022. Eligible studies were screened against the inclusion criteria independently by two reviewers. Only studies published in English were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

Screening was conducted by two independent reviewers following a three-step article screening process. Biographical data and study characteristics were extracted using a data extraction form and synthesised.

Results

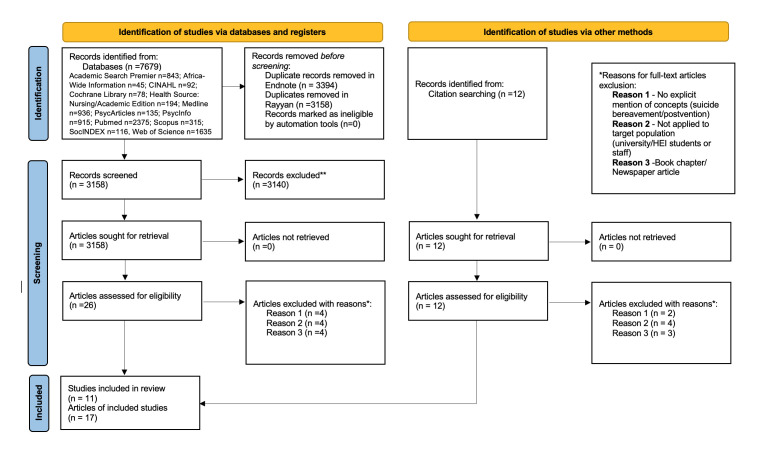

Our search strategy identified 7691 records from which 3170 abstracts were screened. We assessed 29 full texts and included 17 articles for the scoping review. All studies were from high-income countries (USA, Canada, UK). The review identified no postvention intervention studies on university campuses. Study designs were mostly descriptive quantitative or mixed methods. Data collection and sampling were heterogeneous.

Conclusion

Staff and students require support measures due to the impact of suicide bereavement and the unique nature of the university context. There is a need for further research to move from descriptive studies to focus on intervention studies, particularly at universities in low-income and middle-income countries.

Keywords: Suicide & self-harm, EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), Adult psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The review focused on postvention interventions for both staff and students on university campuses globally.

This scoping review was based on a robust methodology for conducting scoping reviews.

The selection process of eligible articles and data extraction was conducted independently by two researchers.

The review provides a synthesis and critical examination of the postvention research and practice on university campuses.

The scoping review was limited to peer-reviewed articles and primary studies published in English and grey literature was excluded.

Introduction

Despite the decrease in suicide rates globally,1 there has been an increase in suicide among university students in recent years.2 3 There is a growing concern over the mental health of university students, with various studies identifying that mental disorders and suicide are higher among university students than the general population.4–9 Suicide has been identified as the fourth leading cause of death among 15–29 year olds globally.1 Pillay2 identified that suicide risk is greatest among students when they face challenges in multiple areas. Some risk factors for student suicide include being black/belonging to a minority group; non-heteronormative sexual orientation; poor socioeconomic background; mental disorders; academic pressure and financial concerns.2 5 10 11

The transition to university life normally coincides with the transition into adulthood, which comes with various challenges and stressors for students, such as leaving home for the first time, financial concerns, including balancing employment with academic demands.3 12 13 Although changes to the higher education sector mean that not all students attend residential universities and live on campus,14 15 some students spend most of their time on campus, especially if they are in residential accommodation.14 15 Given this context, a suicide on campus can be experienced as a community trauma and may be the first time a student encounters a peer’s death compared with a family member’s death.14 Students may experience a range of emotional responses such as shock, depression, fear, anger and loneliness.14 Internal and external factors such as gender, sociocultural background, religious factors and belief in the afterlife contribute to these emotional responses.14 15

Literature often refers to those bereaved by suicide as ‘suicide survivors’ or ‘survivors of suicide’ to describe those who have been bereaved by suicide.16–18 We intentionally chose to use the descriptor ‘students bereaved by suicide’ and its variations to improve clarity. Students bereaved by suicide face a heightened risk for mental disorders, substance use and suicide.19 Suicide bereavement can have a negative impact on physical and psychological well-being over the life-course, such as increased risk of depression and death by suicide.20 The impact of suicide on campus is therefore considered more widespread than a suicide in the general population.21 22

Since students spend most of their time at universities, staff can be considered among the bereaved affected by student suicide. Although there is a dearth of research on the impact of suicide on university staff, research in schools shows that teachers bereaved by suicide reported significant distress and lack of support.23 24 When a student dies, the place of work becomes the place of loss for teaching staff who are now also responsible for teaching grieving students.25 Suicide bereavement significantly impacts bereaved staff and students’ interpersonal relationships (partners, close friends and family). This includes feeling discomfort over the death due to stigma or taboo, and a loss of social confidence leading to social withdrawal.24 26

Suicide prevention strategies recommend providing postvention, defined as the care and support activities offered to those who have been bereaved by suicide to promote recovery and prevent adverse outcomes regarding their grief and mental health.27–29 Five systematic reviews have been conducted on postvention interventions to date.30–34 These systematic reviews identify some elements of postvention that have been found useful such as proactive support immediately following a suicide, counselling, cognitive behavioural approaches, gate-keeper training and bereavement groups.30 33–36 Szumilas and Kutcher30 have asserted that schools should be a site for targeted postvention interventions, an argument which can be extended to university campuses. Although schools and universities share similar characteristics, in that they are both educational institutions, they also have unique needs. Due to the developmental stage12 13 and the prevalence of mental disorders and suicide among university students,6 9 37 it is important to identify postvention interventions specific to university students and with it, the impact of suicide bereavement on university students.

This scoping review aimed to answer the following question: ‘What is known about suicide bereavement and postvention interventions for staff and students at universities?’. The term universities will be used to refer to all higher education institutions (HEIs) throughout. The objectives of the review were to: (a) describe the impact of suicide bereavement on staff and students at universities; (b) identify institutional responses to suicide bereavement at universities; (c) describe postvention interventions at universities. Answering this question and objectives may provide a first step in developing recommendations for further research and guidelines that could assist universities in decision-making and most appropriate action following a student suicide.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guideline for scoping reviews,38 which builds on the seminal work of Arksey and O’Malley39 as well as Levac and colleagues.40 The review is reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist,41 which is congruent with the JBI guidelines. A review protocol was developed but not published (see online supplemental file 1). The research question and objectives were developed through an iterative process involving discussion and collaboration of the three authors (S-LNA, JB, KA).

bmjopen-2022-068730supp001.pdf (71.4KB, pdf)

The scoping review parameters were determined using the ‘PCC’ framework as outlined by the JBI guideline on scoping reviews.38

Participants

The scoping review focused on staff (both academic and non-academic) who were employed at universities or institutions of higher learning in any capacity. Students (undergraduate and postgraduate) at universities or institutions of higher learning were also be included.

Concept

The concept of interest for this scoping review was suicide bereavement and postvention interventions and activities that are related to support for staff and students following suicide on campus.

Context

Studies where research was done on university campuses, or the focus of the research includes staff and students on university campuses or institutions of higher learning globally were included in this scoping review.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design or conduct of this scoping review. The experiences of the authors working with university students informed the need to explore the review question.

Search strategy

As recommended by the JBI guideline,38 a three-step search strategy was used. First, the first author (S-LNA) conducted a preliminary search of Academic Search Premier and PubMed to identify relevant articles in August 2021. S-LNA consulted two expert librarians at Stellenbosch University, to develop a comprehensive search strategy using the words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles and index terms used to describe articles. The two librarians and KA also conducted the searches independently to ensure that the search string was accurate and no errors were identified. The search string comprised a variety of search terms, including MeSH terms, synonyms and variant spellings, connected by Boolean operators. All identified keywords and index terms were included, and this search string (see box 1) was used across the following databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Africa-Wide Information, PsycARTICLES, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, Academic Search Premier, SocINDEX (EBSCOHOST); Cochrane Library, Web of Science, SCOPUS. These databases were selected because they provide a wide range of interdisciplinary literature. In PubMed the following words were filtered using title/abstract: suicide[tiab], (postvention[tiab], “psychosocial intervention”[tiab], “post suicide”[tiab]. The searches were not limited by date of publication or location, but were limited to publications in English. We elected to include only peer-reviewed articles to ensure credible studies were included. The reference lists of included full-text articles and systematic reviews were hand searched for additional references.

Box 1. Search string used across databases.

Search string

(“college student” OR “university student” OR undergraduate OR postgraduate OR lecturer OR faculty OR “administrative staff” OR “administrative personnel” OR “support staff” OR “educational personnel”) AND suicide AND (postvention OR intervention OR bereavement OR grief OR debrief OR debriefing OR “crisis intervention” OR “psychosocial intervention” OR “support after suicide” OR “survivors after suicide” OR “post suicide”) AND (university OR college OR “institution of higher learning” OR campus OR “higher education”).

Study selection

S-LNA conducted the searches (with the assistance of the two librarians and KA) in September 2021 and updated them in June 2022. We followed two independent screening levels for selecting studies for inclusion. Box 2 outlines the inclusion criteria.

Box 2. Inclusion criteria.

Inclusion

The study population consists of university/HEI students and staff. If a study included other populations such as secondary students, and we could not differentiate the results, it was excluded. If the differentiation of the results was clear that they belonged to university students, it would be included.

The study reports data on suicide bereavement or postvention interventions for university/HEI students or staff.

The study used qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods as primary research (no study design limitation imposed).

HEI, higher education institution.

The first level was a title and abstract review, and the second was a full-text review. For the first level of review, Researcher S-LNA uploaded all identified citations from the database searches into EndNote42 and removed duplicates. Thereafter, S-LNA imported all citations into Rayyan QCRI43 and removed further duplicates identified by Rayyan QCRI.43 Two reviewers (S-LNA and EB) screened and selected titles and abstracts independently according to the inclusion criteria. Twenty-nine (n=29) full-text articles were assessed with 17 articles included in the final review. Ten disagreements on study selection were resolved through a consensus discussion. Reasons for disagreement included lack of clarity regarding the study population or whether a study was a peer-reviewed publication. Figure 1 summarises the search and selection process.41

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram. HEI, higher education institution.

Data extraction

The researchers developed and piloted a Microsoft Excel data extraction form based on JBI data extraction template.38 39 After piloting the tool, the researchers knew to include the three aspects which formed the basis of the three objectives (impact of suicide bereavement, postvention interventions at the university and institutional response). Researcher S-LNA extracted information on author, year, journal, affiliation, country of origin, country income group according to the World Bank classification,44 aims, population characteristics, core data on methodology and key findings from each of the 17 included articles. In line with the review aims, information on postvention interventions, definitions of postvention, impact of suicide bereavement, institutional responses, practice implications and recommendations for further development were also extracted. An audit was done by EB on all the articles to ensure the accuracy of extracted data. No errors were identified. Online supplemental table 1 provides an overview of the included studies.

Quality assessment

S-LNA conducted a quality assessment by using an adaptation of the JBI critical appraisal checklists.45 This quality assessment was audited by ZS. Each item on the checklist was given 1 if scored ‘yes’ or 0 if scored ‘no’.45 A total score was calculated for each study which resulted in an overall rating against set criteria of poor quality (less than 50%), moderate quality (50%–80%) and high quality (81%–100%). Most studies received a rating of moderate quality (n=15) and two were low quality. No studies were excluded due to study quality.

Data synthesis

Data were summarised into a descriptive and narrative synthesis due to the variation in study designs to answer the following questions from university settings: describe the impact of suicide bereavement on staff and students at universities; identify institutional responses to suicide bereavement at universities and describe postvention interventions at universities. Results are presented first as a descriptive numerical summary40 (study characteristics) followed by key findings from the included studies.

Results

Study characteristics

The included articles were published between 1989 and 2021 (online supplemental table 1). Most articles (n=8) were from the USA,46–52 seven articles from the UK53–59 and two from Canada.60 61 The article study designs included ten quantitative studies47 48 50–52 54 56 60–62 involving the use of surveys; two qualitative studies using grounded theory and phenomenological approaches49 53 which collected data using semi-structured interviews. Five mixed-methods studies used a combination of questionnaires,46 55 57–59 interviews46 58 and open-ended qualitative questions.55 57–59 Studies that were quantitative or had a quantitative element, used a range of existing outcome measures or developed measures to capture data on grief reactions,46 50 54 56 60 61 impact of suicide bereavement47 48 50–52 54–62 and suicidal behaviours.48 Online supplemental table 1 outlines the outcome measures in greater detail.

Most articles (n=13) identified participants bereaved by suicide through surveys. Two articles46 62 recruited students as participants to evaluate their personal responses to those bereaved by suicide. The other two articles49 53 were qualitative in nature and staff participants were purposively selected as those exposed to student suicide. All study participants were adults at HEIs and ranged between 18 and 70 years old. Most of the articles (n=14), except one,46 had more female participants than male participants. Two articles49 50 did not state the gender profile of the participants. Many of the articles focused on the perspectives of students (n=9)46–48 50–52 60–62 or both staff and student perspectives (n=6)54–59 with only two49 53 focusing exclusively on the perspectives of staff. Most of the articles (n=16) explored the concept of suicide bereavement. We found no published articles which investigated postvention interventions in university settings.

Key findings from included articles

Online supplemental table 1 provides a summary of the key findings of the 17 included articles arranged methodologically. The findings presented below are organised around the review objectives under the headings of: the impact of suicide bereavement on staff and students at universities, institutional responses to suicide bereavement at universities and postvention interventions at universities.

Impact of suicide bereavement on staff and students at universities

Students bereaved by suicide experienced higher levels of general grief reactions compared with those bereaved by other means such as natural causes or accidents.50 60 In one study, the Scale for Prediction of Outcome After Bereavement (SPOB)63 was used to predict the outcome of bereavement on students. The SPOB predicted that those students who were suicide bereaved would have difficulty returning to baseline functioning.51 Staff and students had increased suicidal ideation or attempted suicide following their bereavement, and most of them had not sought help for any episode of self-harm or suicidal ideation.56 As a result of their bereavement experience, for some staff and students (25%) who had never considered suicide as an option, suicide became more normalised. This fostered awareness that suicide could provide a way out of extreme distress for themselves or others.55 They suddenly had a new awareness that in a state of extreme distress, they, or anyone they knew, could be vulnerable to suicide.55 In contrast, half of the staff and students expressed a conviction that they would prevent dying by suicide themselves due to the impact they had witnessed and experienced following a suicide death.55

For students bereaved by suicide, there was a need to understand the death and the reasons that led to the deceased ending their own life.48 50 60 It is as if they needed this explanation to make sense of the suicide. They also felt responsibility that they could have done something to prevent the suicide, and this led to feelings of guilt.48 50 54 60 Some respondents felt like the deceased was punishing them by dying and felt rejected by the deceased.50 60 Students bereaved by suicide experienced shame and embarrassment which set them apart from other students who mourn non-suicidal deaths.50 60 They had more perceived stigma48 54 60 and often felt that other people, especially friends, did not understand their feelings about the suicide death, putting a strain on relationships.48 54 Staff and students reported that they avoided using the word ‘suicide’ as it made other people feel uncomfortable and concealed the cause of death for the same reasons. They also felt the social pressure to no longer be affected by the suicide, so they learned to hide their expressions of grief.58 59

Staff reported physical and psychological responses to student suicide that impacted their personal and professional lives. First, there were the practical tasks to take care of following the death of a student, such as packing up belongings, and initiating administrative processes. Some staff reported that they began to question themselves at perhaps having missed something with the students or not having done more to prevent the suicide.53 Grief following suicide bereavement impacted on staff’s abilities to function in the workplace. Staff reported feeling profound sadness, confusion, anxiety and poor concentration. This led to poor work quality, difficulty working in a team and the loss of self-confidence.57 A small group of staff and students cited an unexpected impact of suicide bereavement in their work. They stated that they used work as a distraction to cope with their emotions and work was also used as a way to make the deceased proud of them.57 Furthermore, the experience of suicide bereavement motivated some of the staff and students to change to careers related to mental health or caring for vulnerable persons.57

Institutional responses to suicide bereavement at universities

There were varying views on support received and accessed, with staff citing that institutional processes were unsupportive to staff in a culture that values student mental well-being over staff well-being.57 Staff further described a lack of institutional support offered or available where managers were insensitive to their needs.57 Within work settings, both staff and students described institutional practices that were unsupportive to their grieving process, such as systems for taking compassionate leave where one had to produce a death certificate, additional work responsibilities because of taking time off and difficulty catching up due to decreased work capacity.57 Furthermore, university administrators identified challenges to responding appropriately to student suicide on campus. These included a lack of postvention training received as part of their role and challenges around notification procedures communicating to the university community about the student death by suicide in a timeous manner before social media platforms shared the news, often before the family had been officially informed. Another challenge for university administrators was balancing their desire to honour the memory of the deceased student while minimising the risk of suicide contagion on campus.49

Staff and students felt that the way that support efforts could be enhanced following suicide bereavement would be to offer support proactively and consistently over time, especially practical support.59 Practical support that was seen as valuable included childcare, help with housework and general administration. Employers and teaching staff could offer practical support by granting time off, extending deadlines and rescheduling examinations.59 Staff and students could also outline their reasons for not seeking support. These included: fear of asking for support, negative experiences of previous attempts to access support, feeling that support would not benefit them and fearing judgement at their need for psychological support.59 One study found that students bereaved by suicide were less likely to receive informal support than those bereaved by natural causes.56 Another study reported that staff and students received informal support from family and friends and said this support was valuable in coping with their grief.59 Staff and students also expressed the need for professional support, but very few accessed formal support.59 Some students felt they did not receive any support and that others were unhelpful.51 52

Postvention interventions at universities

Of the 17 articles included in this scoping review, none spoke directly to any postvention interventions at the respective institutions.

Discussion

The staff and students bereaved by suicide in this review experienced higher levels of grief reactions when compared with bereavement by non-suicide deaths impacting on their personal and occupational functioning. Despite this, the findings demonstrate how staff have been largely marginalised from this research with a focus on university students. Only two studies49 53 focused exclusively on staff experiences. This bias towards studying the experiences of students is understandable, given that universities are set up for students; however, it is important to include staff as they have important support needs also. The staff in this review were responsible for supporting students, attending to practical tasks and informing students following a suicide death.49 53 This raises questions about the responsibilities and expectations placed on staff and whether these are realistic. There is increasing awareness of employer responsibilities for the health and well-being of staff and the safety of students.64

Following their bereavement experience, for some staff and students, suicide became more normalised and increased their awareness that suicide could be a way out of distress.55 This has some implications for suicide contagion among university students and staff. Mueller and Abrutyn65 describe the suicide contagion process where the suicide attempt of a friend can transform the distant idea of suicide into a way an individual can express themselves. Miklin et al66 further identify that suicide bereavement in itself is not inherently risky, but it is how the bereaved person makes sense of the suicide that may contribute to the risk. Among the staff and students in this review, there was a need to make sense of the suicide.48 50 This element for support may need to be considered in any potential interventions for staff and students. Recently, some evidence has pointed to peer-led interventions as a way to support those bereaved by suicide or experiencing suicidality.67 68 This creates an opportunity for these peer-led interventions to be used with university students and staff.

Staff and students experienced support as both helpful and unhelpful. This creates an opportunity for support measures to be enhanced and access to support improved, especially through strategies that reduce the social stigma attached to accessing mental health services.2 One way to improve access is through using online support services such as online forums69 70 or remote services.71

The articles that reported the gender profile of participants had more female than male respondents, a trend that has also been observed in suicide bereavement literature more broadly.72 73 In published suicide research there is a gender imbalance with 60%–90% of participants identifying as women.74 This introduces bias because only women are reporting on the suicide bereavement experience. Future research should explore the perspectives of males and gender non-conforming individuals to gain a diverse perspective on the suicide bereavement experiences.

A systematic mapping of postvention research over the last 50 years75 has identified the need for more intervention studies within postvention research. This review also highlighted this gap as it did not identify studies on postvention interventions at universities. Although we primarily sought out to explore both suicide bereavement and postvention interventions among staff and students at universities, we found literature that only focuses on suicide bereavement among staff and students conducted in high-income countries. This mirrors a trend in postvention literature where 93% of research is concentrated in high-income countries, particularly (USA, UK, Canada, Australia and Sweden)75 when 77% of global suicides occur in low-income and middle-income countries.1

The strength of this review was using a robust methodology to identify some critical gaps in the postvention literature. The findings of this review should be considered within the following limitations. The studies included in this review were limited to peer-reviewed in English, so potentially relevant articles may have been missed if they were available in another language. The inclusion of peer-reviewed articles was to introduce a level of rigour in this scoping review. The review also captured articles from high-income countries with an inadvertent exclusion of low-income and middle-income countries. Grey literature was excluded and potentially relevant articles that could change the review’s outcome could have been missed. Some higher education providers in other countries do not have the word ‘college’ or ‘university’ or ‘campus’ or ‘higher education’ in their descriptors. Therefore, there is the potential that some relevant studies have not been identified in this scoping review.

Conclusion

This review set out to examine suicide bereavement and postvention interventions on university campuses. The review identified studies focusing on suicide bereavement but no studies on postvention interventions on university campuses.

Nonetheless, universities have the potential to be effective sites for interventions but there is not a universal solution that will meet the needs of all institutions. HEIs are not heterogeneous in nature, and this would need to be considered when designing interventions. Some HEIs have distance students, students off campus, some are small and others large. There is a need for postvention research to move beyond descriptive studies to focus on interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the two subject librarians from Stellenbosch University who assisted with the search strategy: Mrs Marleen Hendriksz (Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences) and Mrs Ingrid Van der Westhuizen (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences). Appreciation and thanks is also extended to Dr Elsie Breet as the secondary reviewer throughout the article screening and selection process and data extraction. We are grateful for Ms Zarina Syed, who was able to assist as an auditor for the quality assessment.

Footnotes

Contributors: This scoping review was developed by the intellectual contributions of all the authors. All authors were involved in the developing of the review question and conceptualising the approach. S-LNA developed and tested search terms in consultation with subject librarians. S-LNA in consultation with JB, KA developed the data extraction form. S-LNA reviewed all articles for inclusion and no discrepancies referred to third reviewer. KA and JB contributed to drafting and reviewing the manuscript before submission.

S-LNA is responsible for the overall content as guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the decision to publish.

Funding: The work reported herein was made possible through funding by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) through its Division of Research Capacity Development under the MCSP (awarded to JB) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) (Grant number 142143, awarded to JB). The content hereof is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC or NRF. The work reported herein was made possible through funding by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) through its Division of Research Capacity Development under the MCSP (awarded to JB) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) (Grant number 142143, awarded to JB). The content hereof is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC or NRF.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates; 2021, Report No.: 9789240026643.

- 2.Pillay J. Suicidal behaviour among university students: a systematic review. S Afr J Psychol 2021;51:54–66. 10.1177/0081246321992177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsay BL, Szeto ACH. The influence of media on the stigma of suicide when a Postsecondary student dies by suicide. Archives of Suicide Research;18:1–18. 10.1080/13811118.2022.2121672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giangrasso B, Chung MC, Franzoi IG. Editorial: psychological interventions addressed to higher education students in student psychological services. Front Psychol 2023;14:1129697. 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1129697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bantjes J, Breet E, Saal W, et al. Epidemiology of non-fatal suicidal behavior among first-year university students in South Africa. Death Stud 2022;46:816–23. 10.1080/07481187.2019.1701143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2018;127:623–38. 10.1037/abn0000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortier P, Cuijpers P, Kiekens G, et al. The prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among college students: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2018;48:554–65. 10.1017/S0033291717002215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makhubela M. Suicide and depression in university students: a possible epidemic. South African Journal of Psychology 2021;51:3–5. 10.1177/0081246321992179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bantjes J, Kessler M, Lochner C, et al. The mental health of university students in South Africa: results of the National student survey. J Affect Disord 2023;321:217–26. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortier P, Auerbach RP, Alonso J, et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among first-year college students: results from the WMH-ICS project. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2018;57:263–73. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peltzer K, Yi S, Pengpid S. Suicidal behaviors and associated factors among university students in six countries in the association of Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN). Asian J Psychiatr 2017;26:32–8. 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conley CS, Kirsch AC, Dickson DA, et al. Negotiating the transition to College: developmental trajectories and gender differences in psychological functioning, cognitive-affective strategies, and social well-being. Emerging Adulthood 2014;2:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syed M. Emerging adulthood: developmental stage, theory, or nonsense. In: Arnett JJ, ed. The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016: 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorney P. The empty desk: the sudden death of a nursing classmate. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 2016;74:164–92. 10.1177/0030222815598688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ata AW. Mental health of bereaved Muslims in Australia: religious, gender, after death communication (ADC) and grief issues. j. relig. educ. 2016;64:47–58. 10.1007/s40839-016-0028-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerel J, McIntosh JL, Neimeyer RA, et al. The continuum of "survivorship": Definitional issues in the aftermath of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2014;44:591–600. 10.1111/sltb.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kheibari A, Cerel J, Sanford R. Attitudes about suicide Ideation among suicide loss survivors: A vignette study. Psychol Rep 2019;122:1707–19. 10.1177/0033294118795882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berman AL. Estimating the population of survivors of suicide: seeking an evidence base. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011;41:110–6. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartik W, Maple M, McKay K. Suicide bereavement and stigma for young people in rural Australia: a mixed methods study. Advances in Mental Health 2015;13:84–95. 10.1080/18374905.2015.1026301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur R, Stedmon J. A phenomenological enquiry into the impact of bereavement by suicide over the life course. Mortality 2022;27:53–74. 10.1080/13576275.2020.1823351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leenaars LS, Leenaars AA. Suicide Postvention programs in colleges and universities. In: Lamis DA, Lester D, eds. Understanding and preventing college student suicide. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, 2011: 273–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Streufert BJ. Death on campuses: common postvention strategies in higher education. Death Stud 2004;28:151–72. 10.1080/04781180490264745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kõlves K, Ross V, Hawgood J, et al. The impact of a student's suicide: teachers' perspectives. J Affect Disord 2017;207:276–81. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JE. Korean teachers' bereavement experience following student suicide. Crisis 2019;40:287–93. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arksey AM, Greidanus EJ. “I Could Hardly Breathe”: Teachers’ Lived Experiences of Bereavement After the Violent Death of a Student. CJCP 2022;56:47–69. 10.47634/cjcp.v56i1.68946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azorina V, Morant N, Nesse H, et al. The perceived impact of suicide bereavement on specific interpersonal relationships: a qualitative study of survey data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:10. 10.3390/ijerph16101801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andriessen K. Can Postvention be prevention Crisis 2009;30:43–7. 10.1027/0227-5910.30.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine H. Suicide and its impact on campus. New Directions for Student Services 2008;2008:63–76. 10.1002/ss.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trimble T, Hannigan B, Gaffney M. Suicide postvention; coping, support and transformation. The Irish Journal of Psychology 2012;33:115–21. 10.1080/03033910.2012.709171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szumilas M, Kutcher S. Post-suicide intervention programs: a systematic review. Can J Public Health 2011;102:18–19. 10.1007/BF03404872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tøllefsen IM, Thiblin I, Helweg-Larsen K, et al. Accidents and undetermined deaths: re-evaluation of nationwide samples from the Scandinavian countries. BMC Public Health 2016;16:449. 10.1186/s12889-016-3135-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Sarchiapone M, Postuvan V, et al. Best practice elements of multilevel suicide prevention strategies: a review of systematic reviews. Crisis 2011;32:319–33. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andriessen K, Krysinska K, Hill NTM, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through suicide: a systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. BMC Psychiatry 2019;19:1–15. 10.1186/s12888-019-2020-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andriessen K, Krysinska K, Kõlves K, et al. Suicide Postvention service models and guidelines 2014–2019: a systematic review. Front Psychol 2019;10:2677. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linde K, Treml J, Steinig J, et al. Grief interventions for people bereaved by suicide: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179496. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaid C, Trowman R, Golder S, et al. Interventions for people bereaved through suicide: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2008;193:438–43. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruffaerts R, Mortier P, Auerbach RP, et al. Lifetime and 12-month treatment for mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among first year college students. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2019;28:e1764–15. 10.1002/mpr.1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: JBI manual for evidence synthesis, JBI. 2020. 10.46658/JBIRM-190-01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010;5:1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021;10:1–11. 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Analytics C. Endnote version 20.2. San Francisco: Clarivate Analytics, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:1–10. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Bank . World Bank country and lending groups. 2023. Available: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- 45.Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allen BG, Calhoun LG, Cann A, et al. The effect of cause of death on responses to the bereaved: suicide compared to accident and natural causes. Omega 1994;28:39–48. 10.2190/T44K-L7UK-TB19-T9UV [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balk DE, Walker AC, Baker A. Prevalence and severity of college student bereavement examined in a randomly selected sample. Death Stud 2010;34:459–68. 10.1080/07481180903251810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McIntosh JL, Kelly LD. Survivors' reactions: suicide vs other causes. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 1992;13:82–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rompalo S, Parks R, Taylor A. Suicide Postvention: A growing challenge for higher education administrators. College and University 2021;96:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silverman E, Range L, Overholser JC. Bereavement from suicide as compared to other forms of bereavement. Omega 1995;30:41–51. 10.2190/BPLN-DAG8-7F07-0BKP [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson KE, Range LM. Recent bereavement from suicide and other deaths: can people imagine it as it really is? Omega 1991;22:249–59. 10.2190/10BD-WFE4-YAD3-ARY3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson KE, Range LM. Bereavement following suicide and other deaths - why support attempts fail. Omega 1993;26:61–70. 10.2190/ED92-YN0K-5N2X-PYWB [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Causer H, Bradley E, Muse K, et al. Bearing witness: a grounded theory of the experiences of staff at two United Kingdom higher education institutions following a student death by suicide. PLoS One 2021;16:e0251369. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pitman AL, Osborn DPJ, Rantell K, et al. The stigma perceived by people bereaved by suicide and other sudden deaths: a cross-sectional UK study of 3432 bereaved adults. J Psychosom Res 2016;87:22–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pitman A, Nesse H, Morant N, et al. Attitudes to suicide following the suicide of a friend or relative: a qualitative study of the views of 429 young bereaved adults in the UK. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17. 10.1186/s12888-017-1560-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pitman AL, Rantell K, Moran P, et al. Support received after bereavement by suicide and other sudden deaths: a cross-sectional UK study of 3432 young bereaved adults. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014487. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pitman A, Khrisna Putri A, De Souza T, et al. The impact of suicide bereavement on educational and occupational functioning: A qualitative study of 460 Bereaved adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:643. 10.3390/ijerph15040643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pitman AL, Stevenson F, Osborn DPJ, et al. The stigma associated with bereavement by suicide and other sudden deaths: a qualitative interview study. Soc Sci Med 2018;198:121–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pitman A, De Souza T, Khrisna Putri A, et al. Support needs and experiences of people Bereaved by suicide: qualitative findings from a cross-sectional British study of Bereaved young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:666. 10.3390/ijerph15040666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bailley SE, Kral MJ, Dunham K. Survivors of suicide do grieve differently: empirical support for a common sense proposition. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1999;29:256-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhaskaran J, Afifi TO, Sareen J, et al. A cross-sectional examination of sudden-death bereavement in university students. Journal of American College Health;29:1–9. 10.1080/07448481.2021.1947298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornton G, Whittemore KD, Robertson DU. Evaluation of people bereaved by suicide. Death Studies 1989;13:119–26. 10.1080/07481188908252289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parkes C, Weiss R. Recovery from bereavement basic books. New York, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wieneke KC, Schaepe KS, Egginton JS, et al. The supervisor’s perceived role in employee well-being: Results from Mayo Clinic. American Journal of Health Promotion 2019;33:300–11. 10.1177/0890117118784860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mueller AS, Abrutyn S. Suicidal disclosures among friends: using social network data to understand suicide contagion. J Health Soc Behav 2015;56:131–48. 10.1177/0022146514568793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miklin S, Mueller AS, Abrutyn S, et al. What does it mean to be exposed to suicide?: Suicide exposure, suicide risk, and the importance of meaning-making. Soc Sci Med 2019;233:21–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Higgins A, Hybholt L, Meuser OA, et al. Scoping review of peer-led support for people Bereaved by suicide. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:3485. 10.3390/ijerph19063485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schlichthorst M, Ozols I, Reifels L, et al. Lived experience peer support programs for suicide prevention: a systematic scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst 2020;14:1–12. 10.1186/s13033-020-00396-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cole AB, Leavens EL, Brett EI, et al. Alcohol use and the interpersonal theory of suicide in American Indian young adults. J Ethn Subst Abuse 2020;19:537–52. 10.1080/15332640.2018.1548320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perry A, Pyle D, Lamont-Mills A, et al. Suicidal Behaviours and moderator support in Online health communities: a Scoping review. BMJ Open 2021;11:e047905. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mirick RG, Wladkowski SP. Skype in qualitative interviews: participant and researcher perspectives. TQR 2019;24:3061–72. 10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andriessen K, Castelli Dransart DA, Cerel J, et al. Current Postvention research and priorities for the future. Crisis 2017;38:202–6. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andriessen K, Mowll J, Lobb E, et al. Don’t bother about me. The grief and mental health of Bereaved adolescents. Death Stud 2018;42:607–15. 10.1080/07481187.2017.1415393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maple M, Cerel J, Jordan JR, et al. Uncovering and identifying the missing voices in suicide bereavement. Suicidology 2014;5. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maple M, Pearce T, Sanford R, et al. A systematic mapping of suicide bereavement and Postvention research and a proposed strategic research agenda. Crisis 2018;39:275–82. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-068730supp001.pdf (71.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.