ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

One of the most feared complications of surgeons dealing with hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgery is hepatic artery (HA) injury. Here, we aimed to evaluate our clinical experience (laceration, transection, ligation, and resection) related to HA traumas, which have serious morbidity and mortality risks, in the light of literature data and the rapidly evolving management methods in recent years.

METHODS:

The files of 615 patients who were operated on for HPB pathologies in the last decade, in our hospital, were retrospectively reviewed. Clinical, laboratory, and imaging data obtained from patients’ files were evaluated.

RESULTS:

A total of 13 HA traumas were detected, eight of them had HA injury and five had planned HA resection. During the post-operative follow-up period, liver abscess, anastomotic leakage, and late biliary stricture were detected.

CONCLUSION:

Complications and deaths due to HA injury or ligation are less common today. The risk of complications increases in patients with hemodynamically unstable, jaundice, cholangitis, and sepsis. Revealing the variations in the pre-operative radiological evaluation and determining the appropriate approach plan will reduce the risks. In cases where HA injury is detected, arterial flow continuity should be tried to be maintained with primary anastomosis, arterial transpositions, or grafts.

Keywords: Anomaly, hepatic artery, injury, ligation, resection

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic artery (HA) injury has been one of the deadliest complications in the 1940s. In the studies of Edgecombe and Gardner,[1] it was found that 40 HA ligations were reported until 1950, and mortality developed in 50–75% of them. They also reported that HA was ligated during artery aneurysm, bile duct tumor, stomach tumor, and pancreatic tumor surgeries. Vascular anomalies are also a serious cause of complications for surgeons. In humans, 15–25% of anomalies and variations are observed concerning HA.[1–3] The most common anomaly is the replaced right HA (rRHA) anomaly. In the studies conducted, there is a common belief that more HA injuries occur in patients with anomalies.[3–5]

In autopsy studies, it has been stated that deaths seen as a result of HA injury are mostly due to liver necrosis. Necrosis that occurs in the liver is diffuse or patchy.[1,3] Although significant improvements in complications and mortality rates due to HA injuries have been detected in recent years, it still continues to cause serious morbidity and mortality.[3,6] Better results are obtained today with a better understanding of liver physiology, antibiotics, early diagnosis, interventional procedures, and improved intensive care conditions.

In this study, we aimed to examine the problems related to HA injuries, ligations, and resections encountered during our hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) operations, the approaches we apply, and the prevention methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our hospital is the HPB surgery center, where an average of 1350 laparoscopic cholecystectomies (LC) is performed annually (by 45 general surgeons), as well as the treatment of complicated patients referred from other hospitals. The files of patients who underwent surgery and hilar region dissection due to pancreatoduodenectomies (PDs) performed in the past 10 years and biliary tract pathologies and injuries were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with HA anomalies, HA injuries, and vascular resection detected as a result of examinations made from the operated patients’ files were included in the study. HA anomaly is questioned during routine pre-operative radiological examinations in our clinic. During the operation, the classical anatomy of the HA and its branches is revealed, and it is investigated whether there is a replacement HA originating from the SMA (arteria is first). Routinely, the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) is clamped before ligating and cutting, confirming the presence of pulsation in the right and left HA branches. Resections are started after the HA anatomy is revealed safely. Due to the large number of LC, only patients who developed bile duct injury in our hospital and were referred to our hospital from an external center were evaluated to reveal whether there was HA injury. From the files of patients with HA injury (laceration, accidental resection, or ligation) or planned resection (willingly sacrificed), the way of injury/resection, clinical symptoms encountered in the post-operative (PO) period, laboratory results, radiological findings, and results were evaluated. Injuries in the form of rupture of the lateral wall or HA branch that can be repaired with simple sutures were not included in the study. University Ethics Committee approved study: 2020-GOKAE-0503.

RESULTS

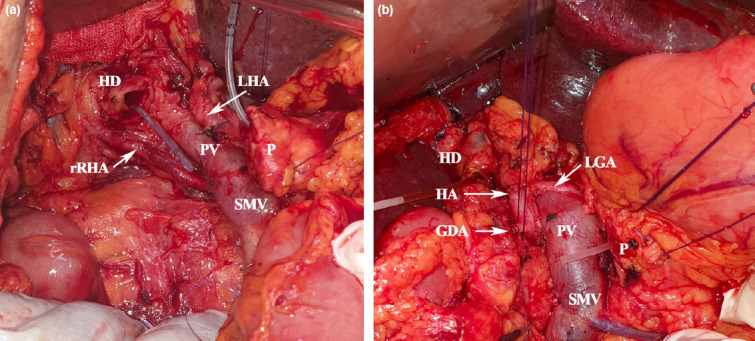

Of the 615 patients included in this retrospective study, 420 had undergone PD due to pancreatic tumors (2010–2020), and the rest (n=195) had extrahepatic biliary tract (EHBT + Gallbladder) (n=111) tumors, biliary tract injuries (n=34), and liver pathologies (n=50) were operated (2015–2020). HA anomaly was found in 43 of the patients (6.9%) who underwent surgery (Fig. 1). HA injury was detected in eight patients. HA anomaly was found in four of eight patients, and the others were anatomically normal. It was detected that planned resection was performed in five patients, two of which were with HA anomalies, due to tumor invasions.

Figure 1.

Surgical pictures of our cases with rRHA anomaly (a) and CHA originating from SMA (b). GDA: Gastroduodenal artery; HD: Hepatic duct; LGA: Left gastric artery; LHA: Left hepatic artery; P: Pancreas; PV: Portal vein; rRHA: Replaced right HA; SMV: Superior mesenteric vein.

It was found that HA trauma developed during LC in three patients. Two of them had major bile duct injury (Pt-4-5) and vascular injury, and the third patient (Pt-1) had isolated HA trauma. Laparotomy was performed in all three patients. In one of these patients (Pt-4, Mirizzi syndrome), the ligated artery was not intervened due to multiple bile duct injury (Strasberg-Bismuth Classification – SBC, Type-E4) and the presence of comorbidity (cerebrovascular occlusion – CVO and hypertension), and the only portoenterostomy was performed. He discharged from the hospital without any problems, although he had a CVO attack and liver abscess in the post-operative period. In the other patient (Pt-5), major biliary tract injury (SBC, Type-E4) was found, along with an injured right HA (cut and ligated) and right portal vein, and massive bleeding (1600 cc). When the HPB team was included in the operation, a demarcation line (Cantlie line) was observed between the lobes and a right hepatectomy underwent. Primary repair (reanastomosis) was performed in our third patient. All three patients are followed up without any problem (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of our patients with hepatic artery injury or planned artery resection

| No | Sex/ Age | Anomalia (Michels) | Procedure (Date)/ Etiology Injury/Ligation/Resection | Repair | Complications + Treatments | Survievall (months) | Reason/Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | F/61 | I | LC + RHA injury | Reconstruction | – | Live | N |

| (4.2010) | 127 m | ||||||

| 2. | M/71 | III | 1st surgery-PD + rRHA injury, | Reconstruction | Biliary fistula, stricture | Excitus | Tumor recurrence |

| 2nd surgery-HJ revision | (Fail ?) | + PTC + stenting + CT | 8 m | ||||

| (5 and 7.2011) | |||||||

| 3. | M/53 | III | PD + rRHA injury (5.2017) | Reconstruction | SSI, perihepatic abscess | Excitus | LM, malignant |

| + drainage | 17 m | pleural effusion | |||||

| 4. | M/68 | I | Mirizzi syndrome - LC + | No-reconstruction | SSI, CVO, LA + CT | Live | |

| Biliary tract (SBC-E3) and | Roux-en-Y | 32 m | N | ||||

| RHA injury (3.2018) | Portoenterostomy | ||||||

| 5. | M/64 | I | LC + Biliary tract (SBC-E4), | Right Hx | – | Live | N |

| PV and RHA injury (12.2018) | 24 m | ||||||

| 6. | F/59 | I | PD + RHA injury? | BT angiography-RHA injury? | POPF, repeated LAs | Excitus | Multiple LA, sepsis |

| (6.2019) | No-reconstruction | + repeated drainage | 5 m | ||||

| 7. | M/53 | III | 1st surg: EHBTT resection + HJ | Reconstruction with | POPF | Excitus | Sepsis, DIC |

| 2nd surg: PD + rRHA injury | Gastroepip-loic artery graft | CT + RT | 14 m | ||||

| (4 and 6.2019) | |||||||

| 8. | M/66 | IV | PD + RHA injury | Reconstruction | Chyle leak, LA | Live | Tumor recurrence |

| (7.2019) | (Fail) | CT + RT | 17 m | ||||

| 9. | F/59 | I | PD + rRHA and PV | PV and RHA reconstruction | Hemodynamic instability | Excitus | LF |

| planned resection | LF? | PO 2nd day | |||||

| (9.2015) | |||||||

| 10. | M/54 | II | PD + CHA planned resection | Reconstruction | POPF, SSI, PPH | Excitus | Tumor recurrence, |

| (11.2016) | + CT | 20 m | peritonitis | ||||

| carcinomatosa | |||||||

| 11. | M/58 | I | EHBTT + RHA planned resection + | No-reconstruction | LA, cholangitis | Excitus | LA, |

| portoenterostomy (4.2019) | + drainage + stenting | 12 m | tumor recurrence, | ||||

| CT + RT | cholangitis | ||||||

| 12. | M/68 | I | EHBTT+ segment- 4B-5 resection, | No-reconstruction | LA | Excitus | LA, renal insuficiency, |

| RHA resection + portoenterostomy | Drainage + CT | 7 m | pneumonia | ||||

| 2.2020 | (Covid-19 ?) | ||||||

| 13. | F/58 | III | EHBTTR, segment- 4B-5 resection, | No-reconstruction | CT + RT | Live | N |

| LHA planned resection + | 10 m | ||||||

| portoenteros-tomy | |||||||

| 2.2020 |

*Michels classification, Age-(/years), CBDI: Common bile duct injury; CHA: Common hepatic artery; CT: Chemotherapy; CVO: Cerebrovascular occlusion; DGE: Delay gastric emptying; EHBTT: Extrahepatic bile duct tumor; F: Female; HA: Hepatic artery; H: Hepaticojejunostomy; Hx: Hepatectomy; IVC: Inferior vena cava; LA: Liver abscess; LC: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; LF: Liver failure; LHA: Left hepatic artery; LM: Liver metastasis; m: Month; M: Male; N: Normal (clinically stabile); PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy; PO: Postoperative; POPF: Postoperative pancreatic fistula; PPH: Post pancreatectomy hemorrhage; PV: Portal vein; RHA: Right hepatic artery; RT: Radiotherapy; SBC: Strasberg-Bismuth Classification for biliary tract injury; SSI: Surgical site infection.

It was found that 4 (%0.9) (Pts-2-3-6-8) of our 420 patients who underwent PD developed HA damage. One of them was noticed in the post-operative period. It was found that three of these patients had HA anomalies, and one had a typical anatomical structure. HA revision was found to be successful in two patients and failed in one patient. In our fourth patient (Pt-6), who developed an abscess on the PO 15th day, it was found that he had HA injury (undesired ligation) by abdominal CT angiography. This patient had excited in the PO 5th month as a result of recurrent liver abscesses.

Planned HA resections were performed in five patients, two during PD surgery (Pts-9-10) and three during EHBT tumor resections (Pts 11-12-13). Primary reconstruction was performed in two patients. However, one patient who develop hemodynamic instability and shock, who also underwent portal vein resection and reconstruction (Pt-9), died on the 2nd post-operative day. The other (Pt-10) died in the PO 17th month due to peritoneal carcinomatosis. Planned HA resection was performed but no reanastomosis was performed in the other three patients in which HA was invaded by the tumor (Table 1).

Eight of our patients were followed up in the first 6 months after discharge without any problem. During the post-operative follow-up period, severe morbidities developed in 8 patients (61.5%), five of the patients with HA injury, and two of the patients who underwent planned HA resection. One of our patients (Pt 9) had excited on the PO 2nd day with hemodynamic instability and shock. Our PO 90th day, mortality was calculated as 7% (1 patient). Liver abscess developed in six of our patients, and three patients had excited. Two of these patients (Pts-6-11) had excited in the PO 5th and 12th month with recurrent liver abscesses and the other patient (Pt-12) in the PO 7th month due to recurrent liver abscesses and pneumonia (radiologically COVID-19). Three patients in our series were drained and recovered due to recurrent abscesses. One of our patients (Pt-8) with an anastomotic leakage (hepaticojejunostomy) improved with drainage and medical follow-up. In one of our patients (Pt-2) who developed stenosis at the hepaticojejunostomy site, biliary drainage was performed with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). However, our patient who also developed liver metastases had excited in the 6th post-operative month.

DISCUSSION

HA can be affected by many pathological conditions, due to its anatomical position and neighborhood, especially tumors. It is one of the most threatened vascular structures during HPB surgeries. The incidence of HA injury in humans is not fully known. There are very little data on this subject in the literature. The risk of injury is higher during LC, PDs, and bile duct surgeries, which are among the most commonly performed operations in the abdomen.[3,5,7,8] Rarely, HA can be injured during stab wounds and interventional procedures.[9]

In the literature, the frequency of any vascular injury during LC has been reported as 0.25% and the frequency of HA injury as 0.06%.[5,7,8] In other words, 10–47% of the patients who develop bile duct injury can also develop HA injury. It is estimated that the right HA injury is more than predicted in the evaluations.[5,7,8,10] This is because LC is widespread and ubiquitous surgery. More surgical interventions are performed for biliary tract and hilar region malignancies than in the past. In their series of 261 cases of bile duct injury developed during LC by Stewart et al.,[5] they found that right HA injury occurred in 84 cases. They also detected that HA injury is more common in Class 3 and 4 type injuries (Stewart-Way classification). In the same series, they reported that additional new HA injuries were more likely to occur in cases in which the primary surgeon tried to repair. Interestingly, they found 11% of RHA injured cases in the series developed liver ischemia. Since artery trauma also develops in some of the patients who develop bile duct trauma, it is appropriate to perform the intervention in experienced centers for patients who need reoperation for revision purposes.[5,7,8]

In patients undergoing reconstruction due to bile duct injury, pre-operative or intraoperative Doppler ultrasonography may help understand whether artery revision is required. While the majority of isolated HA injuries heal without symptoms,[10] morbidity and mortality are higher in HA and biliary tract injuries.[7,11] It is reported in the literature that 11–76% of patients with RHA and bile duct trauma develop ischemic damage in the liver.[3,7] In the post-cholecystectomy biliary stricture series of 55 cases by Alves et al.,[10] they found HA injury in 47% of the cases, mostly RHA and rRHA. Li et al.[7] found that HA injury developed in 10 patients in their series of 60 post-cholecystectomy biliary strictures. In our series, RHA injury developed in two patients with bile duct injury, and isolated RHA injury developed in one patient during LC. HA reconstruction (Pt-1) was performed in one patient, the right hepatectomy was performed in the other (Pt-5), and reconstruction was not performed in the third patient (Pt-4). On the other hand, in our series consisting of patients referred to our hospital due to biliary tract trauma, primary repair was performed in cases with additional arterial trauma during dissection.[12] After the reconstructions, the continuity of the HA blood flow was checked with pulsation control. Doppler USG, which is frequently used in the literature and can show the degree and limitation of liver perfusion, could not be used.

The incidence of HA injury during PD ranges from 0.1% to 4.4%. During resections in patients with chronic pancreatitis or locally advanced tumors, the risk of vascular injury increases due to intense adhesions and inflammation.[6,7,13] In large tumors, the risk of trauma may increase due to the displacement of anatomical structures and tumor invasion. Gaujoux et al.[13] performed angiographies in their PD series of 545 cases to investigate post-operative ischemic conditions. They performed reconstructions on four patients with HA trauma and detected thrombus in angiographies taken in the post-operative period. Although two of the patients with thrombus underwent stenting, one thrombectomy and one surgical revision, three of them were excited due to liver necrosis and abscess. They reported that 3–4% of the cases after PD might develop liver ischemia. Furthermore, ischemic conditions may cause deaths whose cause cannot be determined after surgery.[3] In our PD series of 420 cases, HA injury developed in four patients, and planned HA resection was performed in two patients. One of our patients who underwent planned HA resection had excited due to hemodynamic instability on the 2nd post-operative day. Our other patient, who was noticed on the PO 15th day in which an abscess occurred in the liver and HA injury developed, was excited due to recurrent liver abscesses in the PO 5th month. The left HA (LHA) injury is less common after PD surgeries.[10,14] Although there was no traumatic LHA injury in our series, we had a patient (Pt-13) who underwent LHA resection due to tumor invasion.

HA anomalies are another factor that increases the risk of injury.[6,15] Intertwined anatomical relationships between the pancreas and regional vessels become more complex with an anomaly, increasing vascular injury risk. According to Michel’s classification, normal anatomical structure (Type 1) is present in 52–80% of cases. In cadavers and clinical trials, HA anomaly was found in 15–25% of the cases. Shukla et al.[16] stated that HA variations might show in 55–79% of cases. The incidence of rRHA was reported in the literature as 6.7–19%.[2,4,15,17–19] Rubio et al.’s[17] series stated that 73% of HA injury occurs in anomaly arteries. HA injury was detected in 4 (9.3%) of the 43 anomaly cases in our series. In other words, four of the eight HA injuries in our series occurred in anomaly (50%) cases. HA injury was present in three of our PD cases (Table 1). Eshuis et al.[4] detected rRHA (18.8%) in 143 cases in the PD series of 758 cases and found injuries in 13 of them. Ten patients had severe morbidity, while one patient was excited. In the injuries of rRHA, primary reconstruction is recommended first, but there is no consensus on this issue.[18,20] There are many series that are not reconstructed in rRHA injuries or after resections (Table 2). Okada et al.[20] approach cases with rRHA differently. In cases with rRHA, they reported that trying to protect the artery reduces the chances of R0 resection and that resection should be performed when the tumor is adjacent to or very close to rRHA. Accessory left HA (aLHA) incidence varies between 12 and 22.4%. LHA or aLHA injury is more likely during the celiac region’s dissection for gastric cancer.[14] In our series, planned LHA resection was performed in only one case (Pt-13), but no reconstruction was performed.

Table 2.

Selected and summarized HA injury, ligation, or embolization series in the literature

| Case (n) | Etiology | Anomalia | HA injuries (Laceration/Transsection Ligation/Embolization) | Treatment options Ligation/Embolization Reconstruction | Morbidity n, % | Mortality (90-day) % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edgecombe and | 40 | Review of the literature | N/A | 40 ligation | Ligation ? | LF ?, LA ? | 50–75% |

| Gardner, 1951 | including cholecystectomy | Drainage | |||||

| aneurysm and EHBT tumor | |||||||

| Brittain et al., | 5 | Cholecystectomy | N/A | 5 injury / ligation | No reconstruction | 1 LA | 1 |

| 1964 | Drainage | ||||||

| Alves et al., 2003 | 55 | Postcholecystectomy biliary | 20 ? | 20 rRHA/RHA injury ? | 43 HJ | 1 LA, | N/A |

| tract stricture series | 2 HA pseudoaneurism | 12 right Hx | 12 atrophy | ||||

| (Bismuth type 3-4-5) | 4 portal vein injury | ||||||

| Stewart et al., | 261 | Biliary tract injury | N/A | 84 RHA injury | 4 Hx, HJ, drainage | 12 LA, 9 LN, | 2 |

| 2004 | during LC | 17 bleeding, | |||||

| 7 hemobilia, .. | |||||||

| Gaujoux et al., | 545 | PD series | N/A | 4 injury | 4 (Thrombectomy, | 2 LN, 4 thrombosis, | 3 |

| 2009 | (Postoperative detection) | stenting, reconstruction) | 1 HJ | ||||

| 2 left Hx | |||||||

| Tzeng et al., 2005 | 32 | Liver trauma (15) + | N/A | 32 injury | 32 Embolization | 2 LA | – |

| Interventional | (2 fail) | Drainage | |||||

| HA injury (17) | |||||||

| Li J, et al., 2008 | 60 | Biliary tract injury | N/A | 8 RHA injury | 5 Reconstruction | 3 LN, 3 Hx | 3 |

| during LC | 2 PHA injury | (2 fail) | 2 LA, 3 others | ||||

| Turrini et al., 2010 | 471 | PD series | 47 | 1 injury ? | 2 Reconstruction | – | – |

| 2 planned resection | |||||||

| Eshuis et al., 2011 | 758 | PD series | 143 | 8 planned resection | 3 Reconstruction | 3 PF, 4 DGE, 1 LA, 3 Rlp | 2 |

| 5 injury | |||||||

| Okada et al., 2015 | 180 | PD series | 25 | 6 preop embolization | No-reconstruction | 1 POPF | – |

| and planned resection | |||||||

| El Amrani et al., | 2278 | Systematic analysis for PD | 440 | 49 injury | 18 Reconstruction | POPF 15%, | 0–10% |

| 2016 | (1950-2014) | 6 embolization (preop) | DGE 39%, | ||||

| Landen, et al., | N/A | Systematic review for PD | 3 | 21 injury (8 PHA, 3 RHA, | 5 Reconstruction | 14 LA, 3 LF | 5 (24%) |

| 2017 | (1990-2016) | 3 rRHA, 4 HA thrombosis, | (1 fail) | 6 AL,11 Rlp | |||

| 3 HA injury) | |||||||

| Asano et al., 2018 | 343 | PD series | 51 | 1 rRHA injury | No reconstruction | 1 LA | – |

| 8 rRHA planned resection | 1 drainage | ||||||

| Kleive et al, 2018 | 1535 | Pancreatectomy series | N/A | 14 injury (5 SMA, 5 RHA, | Embolectomy, Hx, | 4 thrombosis, | 2 injured |

| 2 CHA, 2 Celiac trunk) | re-reconstruction, | 2 PPH, 1 POPF | 1 planned | ||||

| 22 planned resection | drainage | 5 LN, 11 Rlp, | |||||

| Elsanousi et al., | 19 | Invasive HCC series | N/A | 19 HALED | 19 HALED* | 8 Ascites-controlled, | 1 pulmonary |

| 2019 | 2 jaundice | embolism | |||||

| Dilek et al., 2020 | 615 | PD series (420) + | 43 | 8 injury (3 rRHA, 5 RHA) | 1 right Hx, | 6 LA, 3 POPF, | 1 planned |

| (Current) | EHBT Tumor (111), | 5 planned resection | 7 Reconstruction (2 fail) | 1 AL, 2 Rlp, | 3** | ||

| Liver (50) | 5 No-reconstruction | 1 stricture | |||||

| EHBT Trauma (34) |

Ligation for therapeutic purpose,

Three patients died of LA at postoperative 5-7-12 months, AL: Anastomotic leakage; CHA: Common HA; DGE: Delayed gastric emptying; EHBT: Extrahepatik bile tract; HJ: Hepp-Couinaud hepaticojejunostomy; Hx: Hepatectomy; HALED: Hepatic artery ligation and extrahepatic collateral division; LA: Liver abscess; LC: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; LF: Liver failure; LHA: Left HA; LN: Liver necrosis; n: Number of cases in series; N/A: Not available; PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy; POPF: Postoperative pancreatic fistula; PHA: Proper hepatic artery; PPH: Post pancreatectomy hemorrhage; Rlp: Relaparotomy; rRHA: Replace right hepatic artery; SMA: Superior mesenteric artery.

The liver damage is expected to occur after HA ligations, resections, or embolization performed unintentionally or for treatment. The same effect is expected after HA injury. However, corrective procedures to be performed and the size of the surgery or accompanying comorbidities affect the results. Many procedures and clinical studies in which HA was attached due to liver pathologies have been described.[21,22] It has been reported that with the ligating of HA, the amount of blood coming to the liver will decrease by 35%, whereas the blood requirement of a metastatic tumor in the liver will decrease by 95%.[21] In their 19 disease HCC series of Elsanousi et al.,[22] 13 of the patients who underwent HA ligation and extrahepatic collateral division (HALED) received a complete response, and they did not see any abscess and necrosis in the liver. However, there is insufficient information on this subject in the literature and prospective studies are needed.

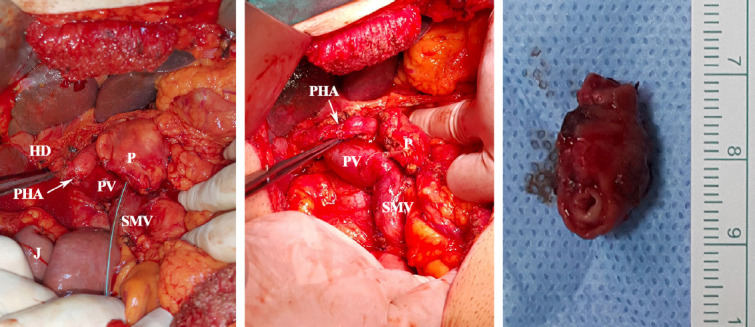

Due to tumor invasion of the HA, especially during PD operations, aggressive tumor resections, and HA resections are gradually increasing.[6,7,13] Kleive et al.[6] performed planned HA resection in 22 (1.43%) cases in their series of 1535 cases. Complications developed in a total of 16 (73%) cases, of which 10 (45%) of 22 cases were severe (thrombosis, bleeding, stenosis, liver necrosis, and bile leakage). In the PD series of 323 cases by Asano et al.,[18] they detected rRHA anomaly in 51 cases. They performed planned resection in eight of them, and they found that accidental injury occurred in one. They found that liver abscess developed in only one case in the series. None of them were reconstructed and that there was no statistical difference with the other patients in terms of demographics. Planned HA resection and reconstruction were performed in 2 (0.047%) of the PD cases in our series (Fig. 2). Of these, the one who had portal vein resection was excited on the post-operative 2nd day. Our other patient recovered and was discharged despite developing a biliary fistula. In three patients (Pts-11-12-13) who underwent planned HA resection due to extrahepatic bile duct tumor invasion, reconstruction was not performed. Reconstruction may not have been performed considering the resection area’s width, the possibility of local recurrence, the occlusion of the arteries due to the tumor invasion process, and the collateral compensation system in the liver. Three of these patients also received chemotherapy, and two received radiotherapy. One of these patients had excited in the 7th post-operative month and the other in the post-operative 11th month. When compared with the complications seen after HA trauma, it was determined that fewer complications developed after planned HA resections.[6,23] The reasons for this may be technological developments, use of antibiotics and improvements in intensive care conditions, less liver damage in hemodynamically stable patients, and the contribution of collateral networks that develop during the invasion of the HA. In our series, results are better in those who underwent planned resection.

Figure 2.

Pictures of our case (Pt-10) undergoing PHA resection and primary reconstruction. HD: Hepatic duct; P: Pancreas; PHA: Proper HA; PV: Portal vein; SMV: Superior mesenteric vein.

As a result of HA trauma, liver abscess, liver failure, anastomotic leakage, late liver atrophy, and bile duct stenosis are the most common complications.[3,4,24–26] In eight series in which Landen et al.[3] detected HA trauma in PubMed screening; complications (liver necrosis/abscess [n=14], liver failure [n=3], and anastomotic dehiscence [n=6]) were reported in 16 (76%) of 21 cases, three of which had artery variations. It was found that 11 of the patients were reoperated, and 5 (24%) of them died. In six patients in our series, liver abscess developed at different times during their follow-up. Three of them had excites with abscesses and accompanying comorbidities at the 5th, 7th, and 12th months. The other three patients recovered after percutaneous drainage.

Due to ischemia of the bile duct wall caused by HA trauma, anastomotic leakage may develop in the early period, and biliary stricture may develop in the long term.[10,26] While mucosal damage due to ischemia in the bile duct mucosa heals with inflammation and fibrosis also causes stricture. Recurrent cholangitis and hepatolithiasis can also be seen in patients with a stricture. In an autopsy study, stenosis in the biliary tract was found in 7% of cadavers with open cholecystectomy.[5,27] In one of our patients (Pt-2), dilatation and biliary stent were applied to the patient who developed anastomosis and biliary fistula, which healed with treatment, but developed stricture during follow-up.

HA reconstruction can be useful in surgery and injuries detected in the early post-operative period. The damaged part should first be repaired primarily. Since liver necrosis occurs within the first 4 days, artery reconstruction should be attempted in patients who underwent relaparotomy within the first 4 days postoperatively. Reconstruction may not always be possible. In cases with proper HA transection, blood flow can be maintained by transposing the GDA or splenic artery.[7,28] In cases with resection, end-to-end anastomosis can be performed, or transpositions from the GDA or lienal artery. Continuity can be achieved with synthetic (PTFE) or autologous graft, allogeneic vascular graft, or prosthetic graft for long distances. The autologous grafts such as a saphenous vein, gonadal vein, inferior mesenteric vein, left renal vein, and gastroepiploic artery are the most preferred vessels. Anastomoses done with a microscope can increase success. We provided continuity with gastroepiploic artery graft in a patient (Pt-7) who developed rRHA injury.

Problem-oriented approaches should be preferred in the management of complications. Antibiotics and percutaneous drainage procedures are recommended in cases with liver abscess. In cases with liver necrosis and subsequent hepatic failure, early prostaglandin E1 administration, hemodiafiltration, and plasma exchange can help recover the liver.[25] However, liver transplantation remains the only option in patients with extensive necrosis and liver failure. About 20–25% of the blood coming to the liver and 40–50% of the oxygen is supplied by HA.[3] In case of interruption of HA flow, the deficiency is tried to be compensated by portal vein flow. In a patient with impaired hemodynamics, the portal vein blood’s oxygenation further deteriorates, and the liver’s oxygenation is disrupted. The presence of hypovolemia, dehydration, anemia, lung problems, pain, excessive sedation, limitation of movement, or heart problems will further increase the risks associated with artery ligation.[26] Struggle with shock and providing oxygenation are the first preventive and therapeutic procedures.

In the pre-operative period, revealing HA and SMAs anatomy by radiological imaging plays a key role in preventing injury, preventing unnecessary procedures, and confirming the indication. During the pre-operative radiological evaluation, it was determined that most of the radiologists saw the HA anomaly but did not reflect it in their reports.[29] A detailed description of vascular formations in MR angiography and CT angiography will be instructive. In surgery, the first prophylactic procedures are to be performed to reveal HA and SMA, turn off the flow before the GDA is cut, and control HA pulses. However, the most important reason for the development of HA trauma is careless dissection, inverted transection, thrombus development, and pseudoaneurysm development. The posterior approach in surgery (arteria is first) can prevent the replace HA injury. The development of portal vein injury with HA is often fatal.[3]

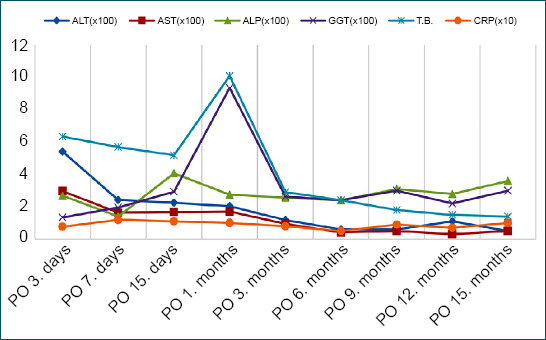

Control and follow-up of transaminases in the early post-operative period can provide important clues. Serum transaminases, which are controlled serially in the early period in the follow-up of patients with or suspected HA injury, might be instructive about the extent of the damage and prognosis. In the 2894 PD series conducted in 25 years by John Hopkins, it was emphasized that there might be a profound relationship between the increase in serum transaminases and clinical progression and prognosis. In this study, it has been shown that if the serum transaminases peak level rises from <500 U/L to 2000 U/L and above, the mortality may increase from 0.9% to 29%.[30] In our series, it was found that transaminases were elevated in the early post-operative period in patients with ligation, remained within normal limits after the 2nd month in all patients except those with abscesses, and showed a fluctuating course in those with abscess (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical view of changes in laboratory findings in the post-operative period. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase (U/L); AST: Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L); ALP: Alkaline phosphatase (U/L); GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/L); T.B.: Total bilirubin (mg/dL); CRP: C-reactive protein (mg/dL).

It has been reported in experienced centers that HA injury will be extremely rare. Kulkarni et al.[28] reported only two HA traumas in their PD series of 434 cases. In the PD series of 1535 cases published in Oslo, Sweden, it was reported that only eight patients (0.52%) had HA trauma.[6] HA injury developed in 8 (1.3%) of 615 patients in our series. We found that the surgeries were performed by different teams at different times. It was found that the same team performed all planned HA resections. We also found that the same team performed about half of the PDs (n=200), hepatectomies (n=50), EHBTT (n=111), and all of the injured even duct reconstructions (n=34), and HA injury occurred in two cases. Other HA injuries were found to occur during surgeries performed by four different teams.

The shortcomings of the study may be that it includes a retrospective and heterogeneous patient group. As seen in the literature, most complications associated with HA are case reports or a limited number of case series. The lack of experimental studies in humans and the insufficient number and variety of our cases are limitations in management. Since laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients were discharged after 1-day follow-up within the scope of outpatient surgery, and their follow-up was not performed, real HA trauma could not be calculated. Retrospective radiological evaluation results show that we have deficiencies in pre-operative radiological evaluation. The fact that different teams performed surgeries at different times is also seen as a factor that negatively affects the result.

Conclusion

Reconstruction should be attempted in the surgery in which HA trauma is detected and in the early post-operative period. Arterial flow can be maintained with primary anastomosis, arterial transpositions, or grafts.

Complications and deaths due to HA trauma or ligation are less common today. In many cases where HA trauma is not noticed, it is thought to be asymptomatic. Liver abscess, bile duct stricture, and anastomosis are the most common complications. The risk of complications increases in patients with hemodynamically unstable, jaundice, cholangitis, and sepsis. The cause of death is often liver necrosis, sepsis, and liver failure. Antibiotic use and drainage reduce risks.

To be protected from artery traumas, performing radiological evaluations (by experienced people) before the operation, revealing the variations, and determining the appropriate approach plan will minimize the risks.

We believe that resections of HA invaded by the tumor are relatively well tolerated by patients. Primary or grafted reconstruction should be done in appropriate cases.

HA trauma is a much less common complication, especially in HPB centers. Considering the possibility of accompanying HA trauma in cases where bile duct trauma develops, the patient should be directed to HPB centers if possible.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: This study was approved by the İzmir Katip Çelebi University Non-interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Date: 22.10.2020, Decision No: 994).

Peer-review: Internally peer-reviewed.

Authorship Contributions: Concept: O.N.D., F.H.D.; Design: A.A., O.N.D.; Supervision: A.A., O.G.; Resource: Ş.K., F.G.; Materials: O.G., Y.S.; Data: F.G., O.G.; Analysis: F.G.; Literature search: Ş.K., Y.S.; Writing: A.A., O.N.D.; Critical revision: O.N.D., F.H.D.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edgecombe PW, Gardner C. Accidental ligation of the hepatic artery and its treatment. Canad Med Assoc J. 1951;64:518–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller P, Randhawa K, Roberts KJ. Preoperative identification of anomalous arterial anatomy at pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:e34–6. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184901768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landen S, Ursaru D, Delugeau V, Landen C. How to deal with hepatic artery injury during pancreaticoduodenectomy. A systematic review. J Visc Surg. 2017;154:261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eshuis WJ, Loohuis KM, Busch OR, van Guik TM, Gouma DJ. Influence of aberrant right hepatic artery on perioperative course and longterm survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:161–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart L, Robinson TN, Lee CM, Liu K, Whang K, Way LW. Right hepatic artery injury associated with laparoscopicbile duct injury: Incidence, mechanism, and consequences. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.02.010. discussion 530–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleive D, Sahakyan MA, Khan A, Fosby B, Line PD, Labori KJ. Incidence and management of arterial injuries during pancreatectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403:341–8. doi: 10.1007/s00423-018-1666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Frilling A, Nadalin S, Paul A, Malago M, Broelsch CE. Management of concomitant hepatic artery injury in patients with iatrogenic major bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:460–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deziel DJ, Millikan KW, Economou SG, Doolas A, Ko ST, Airan MC. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A National survey of 4,292 hospitals and an analysis of 77,604 cases. Am J Surg. 1993;165:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzeng WS, Wu RH, Chang JM, Lin CY, Koay LB, Uen YH, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization for hemorrhage caused by injury of the hepatic artery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1062–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alves A, Farges O, Nicolet J, Warti T, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J. Incidence and consequence of an hepatic artery injury in patients with postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Ann Surg. 2003;238:93–6. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000074983.39297.c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadrijevic S, Sef D, Kocman B, Mrzljak A, Matasic H, Skergo D. Right hepatectomy due to portal vein thrombosis in vasculobiliary injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:412. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acar T, Acar N, Güngör F, Alper E, Gür Ö, Çamyar H, et al. Endoscopic and surgical management of iatrogenic biliary tract injuries. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2020;26:203–1. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2019.62746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaujoux S, Sauvanet A, Vullierme MP, Cortes A, Dokmak S, Sibert A, et al. Ischemic complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: Incidence, prevention, and management. Ann Surg. 2009;249:111–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181930249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oki E, Sakaguchi Y, Hiroshige S, Kusumoto T, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y. Preservation of an aberrant hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery during laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:e25–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Jiang N, Lu MQ, Xu C, Cai CJ, Li H, et al. Anatomical variation of the donor hepatic arteries: Analysis of 843 cases. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27:1164–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shukla PJ, Barreto SG, Kulkarni A, Nagarajan G, Fingerhut A. Vascular anomalies encountered during pancreatoduodenectomy: Do they influence outcomes? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:186–93. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubio-Manzanares-Dorado M, Marín-Gómez LM, Aparicio-Sánchez D, Suárez-Artacho G, Bellido C, Álamo JM, et al. Implication of the presence of a variant hepatic artery during the Whipple procedure. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:417–22. doi: 10.17235/reed.2015.3701/2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asano T, Nakamura T, Noji T, Okamura K, Tsuchikawa T, Nakanishi Y, et al. Outcome of concomitant resection of the replaced right hepatic artery in pancreaticoduodenectomy without reconstruction. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00423-018-1650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Amrani M, Pruvot FR, Truant S. Management of the right hepatic artery in pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:298–305. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada KL, Kawai M, Hirono S, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, Kitahata Y, et al. A replaced right hepatic artery adjacent to pancreatic carcinoma should be divided to obtain R0 resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00423-014-1255-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrelli NJ, Mittelman A. Hepatic Artery Ligation for Liver Cancer. In: Bottino JC, Opfell RW, Muggia FM, editors. Liver Cancer. Boston: Nijhoff Publishing; 1985. pp. 143–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsanousi OM, Mohamed MA, Salim FH, Adam EA. Selective devascularization treatment for large hepatocellular carcinoma: Stage 2A IDEAL prospective case series. Int J Surg. 2019;68:134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brittain RS, Marchioro TL, Hermann G, Waddell WR, Starzl TE. Accidental hepatic artery ligation in humans. Am J Surg. 1964;107:822–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasegawa K, Kubota K, Aoki T, Hirai I, Miyazawa M, Ohtomo K, et al. Ischemic cholangitis caused by transcatheter hepatic arterial chemoembolization 10 months after resection of the extrahepatic bile duct. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000;23:304–6. doi: 10.1007/s002700010074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakamoto I, Aso N, Nagaoki K, Matsuoka Y, Uetani M, Ashizawa K, et al. Complications associated with transcatheter arterial embolization for hepatic tumors. Radiographics. 1998;18:605–19. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.3.9599386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kishi Y, Kajiwara S, Seta S, Hoshi S, Hasegawa S, Hayashi Y, et al. Cholangiojejunal fistula caused by bile duct stricture after intraoperative injury to the common hepatic artery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:125–9. doi: 10.1007/s005340200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halasz NA. Cholecystectomy and hepatic artery injury. Arch Surg. 1991;126:137–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410260021002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni GV, Malinowski M, Hershberger R, Aranha GV. Proper hepatic artery reconstruction with gastroduodenal artery transposition during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2013;25:69–72. doi: 10.1177/1531003513515304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turrini O, Wiebke EA, Delpero JR, Viret F, Lillemoe KD, Schmidt CM. Preservation of replaced or accessory right hepatic artery during pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma: Impact on margin status and survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1813–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winter JM, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Alao B, Lillemoe KD, Campbell KA, et al. Biochemical markers predict morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenecetomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1029–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]